Abstract

The mechanism by which the antitubercular drug isoxyl (ISO) inhibits mycolic acid biosynthesis has not yet been reported. We found that point mutations in either the HadA or HadC component of the type II fatty acid synthase (FAS-II) are associated with increased levels of resistance to ISO in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Overexpression of the HadAB, HadBC, or HadABC heterocomplex also produced high-level resistance. These results show that the FAS-II dehydratases are involved in ISO resistance.

TEXT

The absence of novel effective antituberculosis therapy remains a significant worldwide public health threat due to the rapid development of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant strains (1, 2). The development of potent chemotherapeutic alternatives is crucial to preventing future epidemics of this insidious and often fatal form of the disease. New drugs to treat tuberculosis are urgently needed, yet the pace of new drug development has been slow. One approach to finding new agents is to define the pharmacological target(s) of currently used drugs and develop new therapeutic analogues that possess greater potency than the original molecules against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Isoxyl (ISO; thiocarlide, 4,4′-diisoamythio-carbanilide) began to be used clinically to treat tuberculosis in the 1960s. We and others have shown that this thiourea derivative is a prodrug that must be activated by the mycobacterial monooxygenase EthA, a common activator of most thiocarbamide-containing drugs, including ethionamide and thiacetazone (3–5). In an early study, ISO was shown to inhibit the synthesis of both mycolic acids and free fatty acids in Mycobacterium bovis BCG (6). It was later reported that ISO displays potent activity against other slow- and fast-growing species of Mycobacterium, including multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis, by altering the biosynthesis of all types of mycolic acids and the long-chain fatty acids that are an important component of the mycobacterial cell wall and also alters the synthesis of shorter-chain fatty acids (7). The main effect of ISO on fatty acid metabolism is the inhibition of oleic acid biosynthesis by specifically targeting the membrane-associated stearoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) desaturase DesA3 (Rv3229c) (8). Sterculic acid, a known inhibitor of membrane-associated Δ9 desaturases (8, 9), emulated the effect of ISO on oleic acid synthesis but did not inhibit mycolic acid synthesis (8), suggesting that the two effects of ISO were unrelated. Moreover, the fact that some ISO derivatives were found to affect mainly mycolic acid synthesis while having lost the capacity to inhibit oleic acid production supports the view that ISO has at least an additional target that is directly or indirectly related to the mycolic acid biosynthetic pathway (7).

With the goal of elucidating the molecular mechanism of action of ISO inhibition on mycolic acid synthesis, genetic and biochemical studies of defined strains of M. tuberculosis were undertaken. We report here that components of the dehydratase complex of the type II fatty acid synthase (FAS-II), participating in mycolic acid biosynthesis, are new players in ISO resistance.

The general effect of ISO treatment on mycolic acid inhibition in mycobacteria prompted us to think that ISO could inhibit a specific component of FAS-II. To investigate this hypothesis, genes encoding all four major FAS-II components (kasA, inhA, mabA, and hadABC) were cloned into vector pMV261 and transformed into M. bovis BCG. The constructions pMV261-kasA, pMV261-inhA, and pMV261-hadABC were reported previously (10, 11; G. D. Coxon, D. Craig, R. M. Corralles, E. Vialla, L. Gannoun-Zaki, and L. Kremer, unpublished data). To generate pMV261-mabA, the mabA gene was PCR amplified using M. tuberculosis H37Rv chromosomal DNA with primers MAbA-up (5′-TGACTGCCACAGCCACTGAAGGGGCCAAAC-3′) and MAbA-lo (5′-GGGAATTCTCAGTGGCCCATACCCATGCCGCCGTCGA-3′ [EcoRI site underlined]). The amplicon was restricted with EcoRI and cloned directly into pMV261 cut with MscI/EcoRI. The effect of the overexpression was visually assessed by determining the MIC on Middlebrook 7H11 plates containing OADC (oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase) and increasing drug concentrations (Table 1). Serial 10-fold dilutions of each actively growing culture were plated and incubated at 37°C for 2 to 3 weeks. The MIC99 was defined as the minimum concentration required to inhibit 99% of mycobacterial growth. As expected, overexpression of InhA yielded high-level resistance to both isoniazid (INH) and ethionamide (ETH) compared to the control strain harboring the plasmid vector alone (11). Surprisingly, however, although the overexpression of kasA, inhA, and mabA failed to confer resistance to ISO, the strain harboring a multicopy hadABC gene cluster had an MIC that was 5- to 10-fold higher than the MIC for the control strain.

Table 1.

Antimycobacterial activities of INH, ETH, and ISO against M. bovis BCG strains overexpressing various FAS-II components

| Strain | MIC99 (μg/ml)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| INH | ETH | ISO | |

| pMV261 | 0.1 | 2.5–5 | 0.5–1 |

| pMV261::kasA | 0.1 | 5 | 0.5–1 |

| pMV261::inhA | 2 | 50 | 1 |

| pMV261::mabA | 0.1 | 5 | 0.5–1 |

| pMV261::hadABC | 0.1 | 2.5–5 | 5 |

MIC99s were determined by dilution on 7H11 solid agar medium supplemented with OADC.

It has been proposed that HadABC acts as the FAS-II dehydratase and that HadAB and HadBC can be viewed as two separated heterocomplexes, with HadAB functioning at early and middle steps during mycolic acid elongation, while HadBC would act upon longer substrates at a later step in mycolic acid biosynthesis (12). HadB possesses the catalytic activity (12, 13), whereas both HadA and HadC are thought to work by stabilizing the long acylated-acyl carrier protein (ACP) substrate (12). Overexpression of HadABC in M. tuberculosis has recently been found to be associated with high levels of resistance to thiacetazone (TAC) (14; Coxon et al., unpublished), another thiocarbamide whose activity is dependent on EthA activation (4). The unexpected role for the dehydratase complex in resistance to ISO led us to question whether overexpression of the HadAB and HadBC subunits would be, as reported for TAC, sufficient to confer a resistance phenotype. The genetic constructs pMK1-hadAB and pVV16-hadBC, which overexpress the N-terminally His-tagged HadAB fusion and the C-terminally His-tagged HadBC fusion, respectively (15), were introduced into M. tuberculosis mc27000, an unmarked version of mc26030 (16). All M. tuberculosis recombinant strains were grown at 37°C in Sauton's medium supplemented with 20 μg/ml pantothenic acid. The MICs of ISO and TAC were determined on Middlebrook 7H10 OADC medium containing 20 μg/ml pantothenic acid and increasing drug concentrations. As shown in Table 2, the overexpression of HadAB and, to a lesser extent, that of HadBC were capable of conferring resistance to both ISO and TAC, although the levels of resistance to ISO were significantly lower than for TAC. One possible explanation for the lower level of resistance to ISO could be the additional effect of ISO on oleic acid biosynthesis, through the specific inhibition of the essential stearoyl-CoA desaturase DesA3 (8). Nevertheless, these data suggest that the two drugs have similar mechanisms of action involving the FAS-II dehydratase components.

Table 2.

Antimycobacterial activities of TAC and ISO against M. tuberculosis strains overexpressing various Had complexes

| Strain | MIC99 (μg/ml)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| TAC | ISO | |

| pMK1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| pMK1::hadAB | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| pVV16 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| pVV16::hadBC | >25 | 1 |

| pMV261::hadABC | >50 | 10 |

MIC99s were determined by dilution on 7H10 solid agar medium supplemented with OADC.

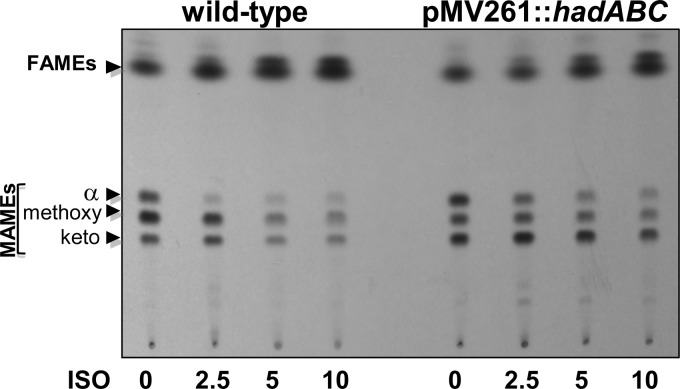

To further evaluate the possible link between HadABC and the effect of ISO on mycolic acid biosynthesis in M. tuberculosis, purified methyl mycolates were prepared from cultures treated for 15 h with increasing concentrations of ISO and then labeled with 1 μCi/ml [14C]acetate for an additional 6 h. Mycolic acid methyl esters were extracted as described previously (10) and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC)-autoradiography. As previously reported (4, 6, 7), all classes of mycolates were affected in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1), but consistent with its higher MICs (Table 2), the synthesis of mycolic acids in the strain overexpressing HadABC was more refractory to ISO inhibition, especially at low concentrations. Overexpression of HadABC by M. tuberculosis was associated with a modified mycolic acid profile, characterized by a reduction in the level of methoxy mycolic acids that form the major subclass in the wild-type strain to the least prominent subspecies in the HadABC-overexpressing strain (Fig. 1). Since HadABC has been shown to physically interact with various FAS-II partners (17), including the methyltransferases that are required for mycolic acid functionalization, it is conceivable that overexpression of HadABC impacts the structure of the FAS-II interactome, leading to an altered mycolic acid pattern. Overall, these results suggest that the amount of the functional HadABC complex determines its susceptibility to ISO.

Fig 1.

Dose-response effects of ISO on mycolic acid biosynthesis in wild-type and HadABC-overexpressing M. tuberculosis strains. The inhibitory effect on the incorporation of [1,2-14C]acetate was assayed by labeling in the presence of increasing drug concentrations. The corresponding fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) and mycolic acid methyl esters (MAMEs) were extracted. Equal counts (20,000 cpm) were loaded onto a TLC plate, and lipids were developed twice in hexane-ethyl acetate (19:1, vol/vol) and exposed overnight to a film.

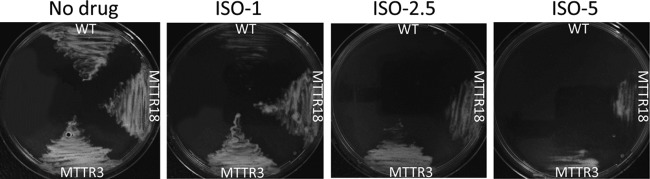

Recently, two independent studies demonstrated that M. tuberculosis strains harboring missense mutations in either HadA or HadC were associated with resistance to TAC (14; Coxon et al., unpublished), so we investigated whether these mutations would also confer resistance to ISO. We first tested two TAC-resistant strains, i.e., MTTR3, which has a HadA C61G substitution, and MTTR18, which has a HadC V85F substitution. The ISO MICs for these strains were at least 10 to 20 times higher than that for the parental M. tuberculosis strain (Table 3). When streaked on agar plates with 2.5 or 5 μg/ml ISO and incubated for 2 to 3 weeks at 37°C, both TAC-resistant strains grew, but not the parental strain (Fig. 2). Similarly, we found that TAC-resistant strains MTTR2 and MTTR6 (Coxon et al., unpublished) carrying a HadC T123A and a HadA C61S mutation, respectively, also exhibited levels of ISO resistance higher than that of the parental strain (Table 3). These results show that strains carrying mutations in the HadA and HadC components of the FAS-II dehydratase are coresistant to both TAC and ISO, suggesting that they have similar mechanisms of action that ultimately lead to alteration of the mycolic acid profile. It has recently been demonstrated that FAS-II is organized into specialized interconnected complexes composed of condensing enzymes, dehydratase heterodimers, and methyltransferases (17–19). This led to the speculation that the interactions among these enzymes are crucial and that their disruption is detrimental to M. tuberculosis survival. That activated ISO (and TAC) is capable of acting by specifically disrupting protein interactions involving the dehydratase complex and other FAS-II partners, leading to a profound alteration of the mycolic acid composition, seems quite conceivable but remains to be established experimentally.

Table 3.

Antimycobacterial activity of ISO against M. tuberculosis strains harboring mutations within hadA or hadC

| Strain | ISO MIC99 (μg/ml)a |

|---|---|

| Wild type | 0.5–1 |

| MTTR3 (HadA_C61G) | >10 |

| MTTR6 (HadA_C61S) | >10 |

| MTTR2 (HadC_T123A) | 10 |

| MTTR18 (HadC_V85F) | >10 |

MIC99s were determined by dilution on 7H10 solid agar medium supplemented with OADC.

Fig 2.

Mutations within HadA or HadC confer growth resistance during ISO treatment. Mid-log-phase cultures of wild-type (WT) M. tuberculosis and strains carrying either the C61G mutation in HadA (MTTR3) or the V85F mutation in HadC (MTTR18) were streaked onto Middlebrook 7H10 OADC plates supplemented with increasing concentrations of ISO (1, 2.5, and 5 μg/ml). Plates were incubated for 2 to 3 weeks at 37°C, after which growth was visualized.

EthA has been shown to act as the common activator of both TAC and ISO (4), but the cross-resistance in our HadA and HadC mutants cannot be attributed to an additional mutation in the EthA activator, as the ethA gene had been sequenced in these strains and found to be of the wild type (Coxon et al., unpublished). In a previous study, coding sequence mutations in ethA were found in a panel of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patient isolates from Cape Town that were resistant to ETH, TAC, and ISO (3). Interestingly, the same study also identified a few ETH-susceptible strains possessing a wild-type ethA gene but exhibiting moderate or high-level resistance to both TAC and ISO (3). On the basis of our data, we suspect that these strains could have had mutations in either HadA or HadC, although the possibility that TAC and ISO have an additional mechanism of action in common cannot be ruled out until a large panel of strains resistant to both TAC and ISO but susceptible to ETH is analyzed.

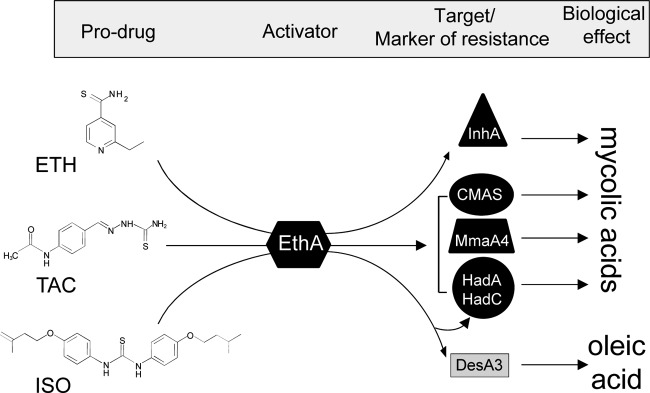

While all EthA-activated thiocarbamides affect the synthesis of mycolic acids, each drug appears to have distinct modes of action (Fig. 3), as only ISO inhibits oleic acid biosynthesis, whereas TAC alone can inhibit mycolic acid cyclopropanation in various mycobacterial species (20; Coxon et al., unpublished). An explanation for these differences may require a more complete understanding of the structures of the proteins involved and how the drugs alter their interactions and enzymatic activity.

Fig 3.

Mechanisms of action and/or markers of resistance to the major antitubercular thiocarbamide-containing prodrugs. ETH, TAC, and ISO are all prodrugs that get into tubercle bacilli by passive diffusion, where they are activated by the monooxygenase EthA. Once activated, ETH inhibits mycolic acid biosynthesis by targeting the FAS-II enoyl ACP reductase InhA. Activated TAC and ISO affect mycolic acid composition through InhA-independent mechanisms involving other important mycolic acid biosynthetic enzymes. TAC has been shown to inhibit mycolic acid cyclopropanation (CMAS), and high resistance levels were found to be associated with mutations within the methyltransferase MmaA4 and within the HadA or HadC component of the FAS-II dehydratase. This study provides evidence that the same mutations in HadA or HadC correlate with increased levels of resistance to ISO, suggesting that TAC and ISO can have mechanisms of activation and action in common. In addition, oleic acid synthesis appears to be specifically inhibited through inhibition of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase DesA3 by activated ISO.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank W. R. Jacobs for the generous gift of M. tuberculosis mc27000 and H. Takiff for critical reading of the manuscript and for helpful discussions.

ADDENDUM

While this report was under review, a report was published (A. E. Grzegorzewicz et al., J. Biol. Chem., 2012) providing comparable results and conclusions supporting a link between isoxyl resistance and the M. tuberculosis FAS-II dehydratase.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 October 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Espinal MA. 2003. The global situation of MDR-TB. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 83:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mondal R, Jain A. 2007. Extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:1429–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeBarber AE, Mdluli K, Bosman M, Bekker LG, Barry CE., III 2000. Ethionamide activation and sensitivity in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:9677–9682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dover LG, Alahari A, Gratraud P, Gomes JM, Bhowruth V, Reynolds RC, Besra GS, Kremer L. 2007. EthA, a common activator of thiocarbamide-containing drugs acting on different mycobacterial targets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1055–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kordulákova J, Janin YL, Liav A, Barilone N, Dos Vultos T, Rauzier J, Brennan PJ, Gicquel B, Jackson M. 2007. Isoxyl activation is required for bacteriostatic activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3824–3829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winder FG, Collins PB, Whelan D. 1971. Effects of ethionamide and isoxyl on mycolic acid synthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis BCG. J. Gen. Microbiol. 66:379–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Phetsuksiri B, Baulard AR, Cooper AM, Minnikin DE, Douglas JD, Besra GS, Brennan PJ. 1999. Antimycobacterial activities of isoxyl and new derivatives through the inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1042–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Phetsuksiri B, Jackson M, Scherman H, McNeil M, Besra GS, Baulard AR, Slayden RA, DeBarber AE, Barry CE, III, Baird MS, Crick DC, Brennan PJ. 2003. Unique mechanism of action of the thiourea drug isoxyl on Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:53123–53130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gratraud P, Huws E, Falkard B, Adjalley S, Fidock DA, Berry L, Jacobs WR, Jr, Baird MS, Vial H, Kremer L. 2009. Oleic acid biosynthesis in Plasmodium falciparum: characterization of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase and investigation as a potential therapeutic target. PLoS One 4:e6889 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kremer L, Douglas JD, Baulard AR, Morehouse C, Guy MR, Alland D, Dover LG, Lakey JH, Jacobs WR, Jr, Brennan PJ, Minnikin DE, Besra GS. 2000. Thiolactomycin and related analogues as novel anti-mycobacterial agents targeting KasA and KasB condensing enzymes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:16857–16864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Larsen MH, Vilcheze C, Kremer L, Besra GS, Parsons L, Salfinger M, Heifets L, Hazbon MH, Alland D, Sacchettini JC, Jacobs WR., Jr 2002. Overexpression of inhA, but not kasA, confers resistance to isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium smegmatis, M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 46:453–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sacco E, Covarrubias AS, O'Hare HM, Carroll P, Eynard N, Jones TA, Parish T, Daffe M, Backbro K, Quemard A. 2007. The missing piece of the type II fatty acid synthase system from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:14628–14633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown AK, Bhatt A, Singh A, Saparia E, Evans AF, Besra GS. 2007. Identification of the dehydratase component of the mycobacterial mycolic acid-synthesizing fatty acid synthase-II complex. Microbiology 153:4166–4173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belardinelli JM, Morbidoni HR. 2012. Mutations in the essential FAS II β-hydroxyacyl ACP dehydratase complex confer resistance to thiacetazone in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium kansasii. Mol. Microbiol. 86:568–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Slama N, Leiba J, Eynard N, Daffe M, Kremer L, Quemard A, Molle V. 2011. Negative regulation by Ser/Thr phosphorylation of HadAB and HadBC dehydratases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis type II fatty acid synthase system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 412:401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sambandamurthy VK, Derrick SC, Hsu T, Chen B, Larsen MH, Jalapathy KV, Chen M, Kim J, Porcelli SA, Chan J, Morris SL, Jacobs WR., Jr 2006. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DeltaRD1 DeltapanCD: a safe and limited replicating mutant strain that protects immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice against experimental tuberculosis. Vaccine 24:6309–6320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cantaloube S, Veyron-Churlet R, Haddache N, Daffe M, Zerbib D. 2011. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis FAS-II dehydratases and methyltransferases define the specificity of the mycolic acid elongation complexes. PLoS One 6:e29564 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Veyron-Churlet R, Bigot S, Guerrini O, Verdoux S, Malaga W, Daffe M, Zerbib D. 2005. The biosynthesis of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis relies on multiple specialized elongation complexes interconnected by specific protein-protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 353:847–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Veyron-Churlet R, Guerrini O, Mourey L, Daffe M, Zerbib D. 2004. Protein-protein interactions within the fatty acid synthase-II system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for mycobacterial viability. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1161–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alahari A, Trivelli X, Guerardel Y, Dover LG, Besra GS, Sacchettini JC, Reynolds RC, Coxon GD, Kremer L. 2007. Thiacetazone, an antitubercular drug that inhibits cyclopropanation of cell wall mycolic acids in mycobacteria. PLoS One 2:e1343 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]