Abstract

Across diverse eukaryotes, the Paf1 complex (Paf1C) plays critical roles in RNA polymerase II transcription elongation and regulation of histone modifications. Beyond these roles, the human and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Paf1 complexes also interact with RNA 3′-end processing components to affect transcript 3′-end formation. Specifically, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Paf1C functions with the RNA binding proteins Nrd1 and Nab3 to regulate the termination of at least two small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs). To determine how Paf1C-dependent functions regulate snoRNA formation, we used high-density tiling arrays to analyze transcripts in paf1Δ cells and uncover new snoRNA targets of Paf1. Detailed examination of Paf1-regulated snoRNA genes revealed locus-specific requirements for Paf1-dependent posttranslational histone modifications. We also discovered roles for the transcriptional regulators Bur1-Bur2, Rad6, and Set2 in snoRNA 3′-end formation. Surprisingly, at some snoRNAs, this function of Rad6 appears to be primarily independent of its role in histone H2B monoubiquitylation. Cumulatively, our work reveals a broad requirement for the Paf1C in snoRNA 3′-end formation in S. cerevisiae, implicates the participation of transcriptional proteins and histone modifications in this process, and suggests that the Paf1C contributes to the fine tuning of nuanced levels of regulation that exist at individual loci.

INTRODUCTION

Many proteins contribute to regulating RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) transcription to ensure accurate RNA synthesis. One such group of regulatory proteins is the conserved eukaryotic Paf1 (polymerase-associated factor 1) complex (Paf1C) (1, 2). The Paf1C is comprised of the Paf1, Cdc73, Ctr9, Rtf1, and Leo1 subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (3–6). Originally discovered by virtue of its interaction with RNA Pol II, the yeast Paf1C associates with RNA Pol II at actively transcribed open reading frames (ORFs) from the start site of transcription to the poly(A) site (4, 7–9). The full recruitment of the yeast Paf1C to active genes requires the protein Spt5, which is phosphorylated by the Bur1-Bur2 cyclin-dependent kinase/cyclin (CDK-cyclin) complex (10–12). The human Paf1C also contains the Ski8 protein, which localizes to transcriptionally active genes in a manner dependent on the rest of the complex (13). The evolutionary conservation of the Paf1C and its important functions allow extrapolation of budding yeast studies to higher eukaryotes.

The best-characterized functions of the Paf1C are in regulating transcription elongation and promoting histone modifications. The yeast and human Paf1 complexes can stimulate efficient transcription elongation in vitro and in vivo (14–17). Transcription through a chromatin template is further regulated by the Paf1C-dependent posttranslational modification of histones. For example, the trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 36 (K36) by the methyltransferase Set2 requires the Paf1C, mediated primarily through the Paf1 and Ctr9 subunits (18). The monoubiquitylation of yeast histone H2B K123, which is dependent on the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Rad6 and the ubiquitin protein ligase Bre1, also requires the Paf1C (19, 20). H2B K123 monoubiquitylation is required in turn for both Set1-mediated di- and trimethylation of histone H3 K4 and Dot1-catalyzed histone H3 K79 methylation (19–24). Analogously, the human Paf1C facilitates human Rad6 (hRad6) and human Bre1 (hBre1) recruitment leading to the monoubiquitylation of H2B K120, a mark that also engages in histone modification cross talk by facilitating hDot1-dependent methylation of H3 K79 and hSet1/MLL1-dependent methylation (MLL stands for mixed lineage, leukemia) of H3 K4 (13, 25). Found at sites of active transcription, these Paf1C-dependent histone modifications can affect recruitment of other proteins that participate in RNA Pol II transcription (23, 26–29). The function of hBre1/Rnf20 as a tumor suppressor highlights the clinical importance of these histone marks (30). The Paf1C in higher eukaryotes also has gene-specific functions, such as regulating the expression of genes dependent on the Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog signaling pathways (31–34). These many roles may explain why perturbations of Paf1C in higher eukaryotes can alter stem cell pluripotency, development, antiviral responses, and cancer progression (31, 32, 34–40).

Much less understood is the function of the Paf1C in RNA transcript termination and 3′-end formation. In both yeast and humans, the Paf1C has been shown to interact with RNA cleavage and polyadenylation factors (41, 42). In yeast, the Paf1C has also been shown to affect poly(A) site utilization and the proper 3′-end formation of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) (43, 44). snoRNAs constitute an important class of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), which function during rRNA processing reactions and have been implicated in tumorigenesis and diseases, such as Prader-Willi syndrome (45–47). In addition to the Paf1C, the 3′-end formation of certain yeast snoRNAs requires the RNA binding proteins Nrd1 and Nab3, the helicase Sen1, and the peptidyl prolyl-cis/trans-isomerase Ess1 (44, 48–52). Extended snoRNA transcripts are processed to their mature length by the exosome, a conserved nucleolytic complex (53, 54). Transcripts produced from two snoRNA genes, SNR13 and SNR47, have been shown to require Paf1 to promote efficient 3′-end formation and prevent the extension of RNAs into downstream genes (44). Previous work has implicated Paf1C-dependent histone modifications in this process, such as H2B K123 ubiquitylation affecting 3′-end formation of SNR47 and SNR13 and H3 K4 trimethylation contributing to SNR13 termination (55, 56). It remains an open question whether these modifications are universally required at all Paf1-dependent snoRNA targets.

To better understand snoRNA 3′-end formation and the involvement of the Paf1C in this process, we explored the roles of the Paf1C and histone modifications at all potential snoRNA targets. Examination of high-density tiling arrays to find RNA transcripts affected by the loss of PAF1 uncovered additional snoRNA transcripts that require the Paf1C for their proper 3′-end formation. Through further analysis of these snoRNAs, we demonstrate locus-specific levels of regulation by showing that the H2B ubiquitylation pathway is critical at only a subset of Paf1-targeted snoRNAs. Our studies on the involvement of Rad6 in snoRNA termination reveal that Rad6 can have roles at snoRNAs that are primarily independent of H2B K123 ubiquitylation. Furthermore, we have discovered functions for the Bur1-Bur2 complex and the Set2 methyltransferase in the formation of these ncRNA transcripts. Taken together, these results improve our understanding of the roles that the Paf1C and its dependent histone modifications play in gene expression and transcription termination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and media.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 and, unless otherwise noted, are isogenic to strain FY2, a GAL2+ derivative of strain S288C (57). Yeast transformations, gene disruptions, and genetic crosses were performed as previously described (58, 59). All integrations and gene disruptions were confirmed by PCR. Strains with an integrated copy of the htb1-K123R (htb1 gene with K changed to R at position 123 of the encoded H2B protein) allele have been described (56). As was done previously (60), a truncated version of Set2 was generated (amino acids 1 to 261) using PCR amplification of pFA6a-13Myc-kanMX6 (61) integrated into the endogenous SET2 locus. Strains were confirmed by PCR and Western blot analysis, which demonstrated the presence of the epitope tag, the absence of histone H3 K36 trimethylation, and the presence of H3 K36 dimethylation. The LEU2-marked control plasmid (pADH1-HIS3-CYC1) and SNR47 termination reporter plasmid [pADH1-SNR47(70)-HIS3-CYC1] used in Fig. 7 have been described previously (62). The termination reporter plasmid contains 70 bp of the SNR47 3′-end formation element sufficient for termination just upstream of HIS3. Cells that cannot properly terminate transcription within these 70 bp will express a read-through transcript containing HIS3 that allows for strong growth on media lacking histidine. The control plasmid lacks these 70 bp, and all cells with this plasmid express HIS3 from the ADH1 promoter. Unless otherwise noted, cells were grown at 30°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium (59).

Table 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | MAT | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|---|

| KY1267 | α | rrp6Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1378 | α | paf1Δ::kanMX4 rad6Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1453 | α | paf1Δ::kanMX4 bur2Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1664 | a | leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 paf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1699 | α | Prototroph |

| KY1700 | α | paf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1702 | a | leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 paf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1703 | a | rtf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1704 | α | rtf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1705 | a | ctr9Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1706 | α | cdc73Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1712 | α | rad6Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1713 | a | bre1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1718 | α | bur2Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY1805 | α | leo1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2041 | a | trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 rtf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2042 | α | leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 |

| KY2043 | a | HTA1-HTB1 hta2Δhtb2Δ::kanMX trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 |

| KY2044 | a | HTA1-htb1K123R hta2Δhtb2Δ::kanMX trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 |

| KY2045 | α | trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 rad6Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2046 | α | trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 bre1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2048 | α | trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 |

| KY2090 | a | leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 |

| KY2276 | a | leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| KY2277 | α | trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 rtf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2278 | α | ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 trp1Δ63 |

| KY2279 | α | ura3Δ0 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 trp1Δ63 paf1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2280 | a | leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 set2Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2281 | α | leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 trp1Δ63 set2(1-261)::13MYC-kanMX4 |

| KY2282 | a | his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 set2Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2283 | α | his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 set2Δ::kanMX4 bre1Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2338 | a | leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 set2(1-261)::13MYC-kanMX4 |

| KY2339 | a | leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 rad6Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2377 | α | paf1Δ::kanMX4 rrp6Δ::kanMX4 |

| KY2409 | a | leu2Δ0 ura3-52 bur2Δ::kanMX4 |

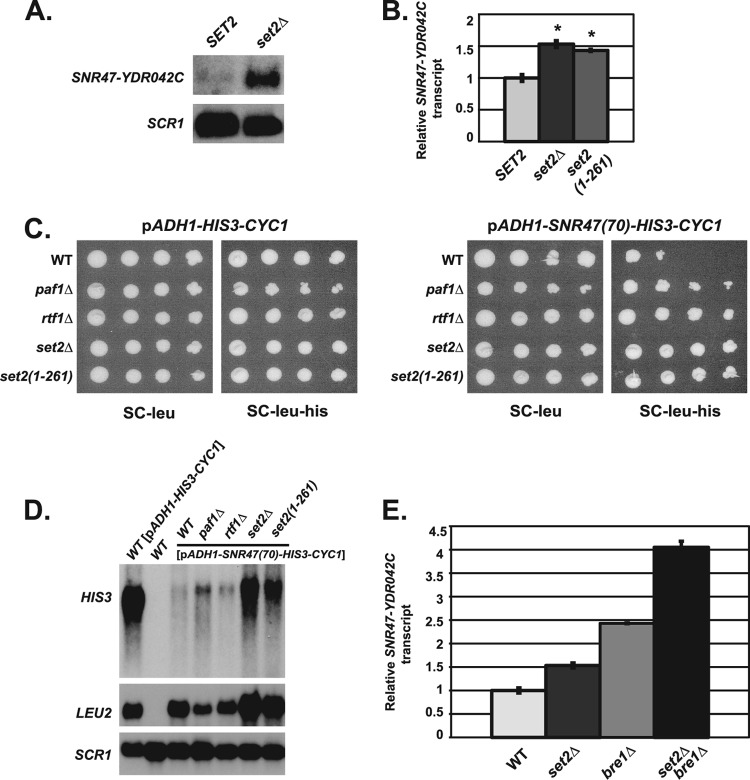

Fig 7.

Set2 is involved in snoRNA termination through a pathway distinct from H2B ubiquitylation. (A) Representative Northern blot analysis of extended SNR47 transcripts (SNR47-YDR042C) in wild-type (KY2090) and set2Δ (KY2280) cells. SCR1 transcript levels serve as a loading control. (B) Quantification of SNR47-YDR042C transcript levels in wild-type (KY2048), set2Δ (KY2282), and set2(1-261) (KY2281) cells measured by RT-qPCR, with the relative signal of the wild type set at 1. The SEMs are indicated by the error bars. Asterisks indicate a P value of <0.0025 relative to wild type. (C) The following his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 strains were transformed with an established LEU2-marked SNR47 reporter plasmid [pADH1-SNR47(70)-HIS3-CYC1] or control plasmid (pADH1-HIS3-CYC1) (see Materials and Methods for more information): wild-type (KY2042), paf1Δ (KY1664), rtf1Δ (KY2041), set2Δ (KY2280), and set2(1-261) (KY2338). Tenfold serial dilutions of cells containing the listed plasmids were spotted on synthetic complete medium lacking leucine (SC-leu) and synthetic complete medium lacking leucine and histidine (SC-leu-his) and incubated for 5 days at 30°C. (D) Representative Northern blot analysis examining HIS3 transcripts from the SNR47 reporter plasmid in his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 strains (as in panel C). Wild-type cells with the control plasmid (pADH1-HIS3-CYC1) show the size of the HIS3 transcript lacking 70 bp of the SNR47 sequence. LEU2 transcript levels serve as a control for plasmid levels, and SCR1 transcript levels control for total RNA. RNA from a his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 strain (KY2090) containing no plasmids (WT) (lane 2) serves as a control for probe specificity. (E) Quantification of SNR47 extended transcripts (SNR47-YDR042C) in wild-type (KY2048), set2Δ (KY2282), bre1Δ (KY2046), and set2Δ bre1Δ (KY2283) cells determined by RT-qPCR, with the relative signal of the wild type set at 1. The SEMs are indicated by the error bars.

Northern blot analyses.

Total RNA was isolated from cells grown to log phase and subjected to Northern blot analysis with random prime-labeled, PCR-amplified DNA probes as described previously (63). The SNR47-YDR042C, SNR48-ERG25, and SNR79-SEN2 probes were designed to detect transcription downstream of snoRNA genes, whereas the SNR47 probe used in Fig. 6C was designed against sequences internal to SNR47 (see Table 2 for a list of primers). These snoRNA probes were made using [α-32P]dATP and [α-32P]dTTP; SCR1 probes were made using [α-32P]dATP. Signals were quantified using ImageJ software and were made relative to the SCR1 loading control signal. The relative signal from the wild-type control strain was set equal to one within each Northern blot analysis. For quantification of all Northern blot analyses, signals were averaged for at least three independent sample preparations. Error bars represent plus and minus 1 standard error from the mean (SEM).

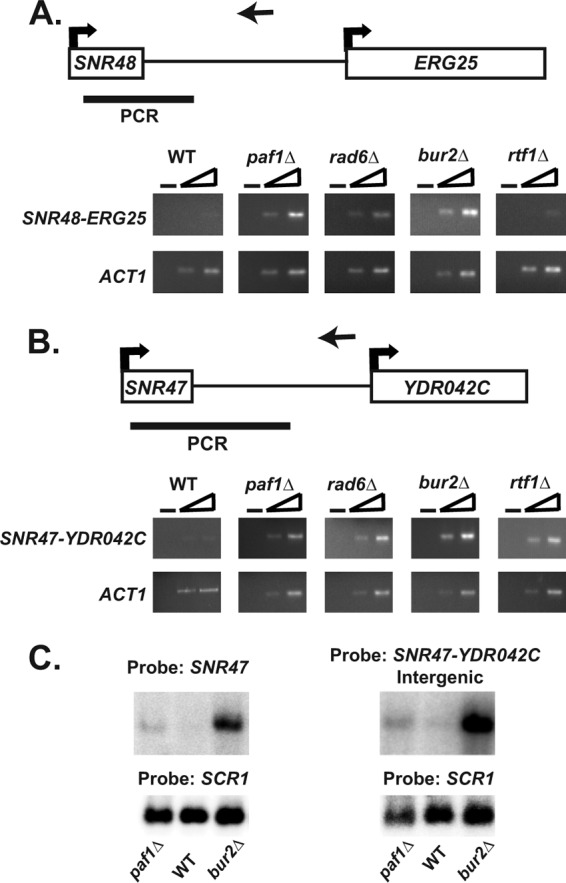

Fig 6.

Analysis of SNR47 and SNR48 read-through transcripts. (A and B) As described in Materials and Methods, strand-specific cDNA was generated using a primer downstream of either SNR47 or SNR48 (primer locations indicated by the arrows pointing left). For a control, a no-reverse transcriptase (no-RT) reaction was performed on each sample as indicated by the minus sign. PCRs were done with two different concentrations of each cDNA using a primer within the snoRNA sequence and a primer downstream of the snoRNA (sequences found in PCR product indicated by a black bar). ACT1 is used as a positive control for RT-PCR experiments. RT-PCR analysis was performed in triplicate from independent biological replicates. See Table 2 for the sequences of the primers used. (A) Representative RT-PCRs at SNR48 from wild-type (KY1699), paf1Δ (KY1700), rad6Δ (KY2045), bur2Δ (KY1718), and rtf1Δ (KY1703) cells. (B) Representative RT-PCRs at SNR47 from wild-type (KY1699), paf1Δ (KY1700), rad6Δ (KY2339), bur2Δ (KY1718), and rtf1Δ (KY1703) cells. (C) Northern blot analysis using RNA from wild-type (KY2276), paf1Δ (KY1702), and bur2Δ (KY2409) cells. Identical RNA was run on the same gel in parallel, and then after the gel was transferred to a membrane, each half of the membrane was hybridized with either a probe against the snoRNA sequence of SNR47 or a probe against the regions downstream of SNR47 (SNR47-YDR042C). Both probes recognized the SNR47 read-through transcript depicted.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Probe or primer (sequence locationa) | Directionb | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| SCR1 Northern probe (−242 to +283 of SCR1) | F | 5′-CAACTTAGCCAGGACATCCA-3′ |

| R | 5′-AGAGAGACGGATTCCTCACG-3′ | |

| SNR47-YDR042C Northern probe (−325 to −33 of YDR042C) | F | 5′-CTGTTTCTGTTTCGCGTCGGGATAAC-3′ |

| R | 5′-GACAAACATGAAGAAGATATAAGTGCGTG-3′ | |

| SNR48-ERG25 Northern probe (−746 to −191 of ERG25) | F | 5′-CCTTGGCGCAGAAGACTTTCTCTTC-3′ |

| R | 5′-CTTGTATGCGTACGCCTGTGTATGC-3′ | |

| SNR79-SEN2 Northern probe (−235 to −35 of SEN2) | F | 5′-GTCAAAAATGTTTTATAGAAGCCACTCTTGC-3′ |

| R | 5′-CAGCGTCGTGTTACAATGAAACG-3′ | |

| ACT1 qRT-PCR, RT-PCR (+534 to +723 of ACT1) | F | 5′-TGTCACCAACTGGGACGATA-3′ |

| R | 5′-GGCTTGGATGGAAACGTAGA-3′ | |

| SNR47-YDR042C qRT-PCR + SNR47 ChIP primer set 3 (+225 to +323 of SNR47) | F | 5′-CGCGTCGGGATAACAAAGCGTAC-3′ |

| R | 5′-CCCTGTTATCCGCCTTTCTTCTTGG-3′ | |

| SNR32-CHS7 qRT-PCR (+211 to +314 of SNR32) | F | 5′-CTGGTTCTTAGTAACGTACTTTAGTAGC-3′ |

| R | 5′-CCTGTTGTAAACGTTCGCGTTGGC-3′ | |

| SNR85-NUP188 qRT-PCR (+219 to +369 of SNR85) | F | 5′-CGGCTCCTGCTTGTAGTTAAGG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GTGTTTCTGTTCGAATATTAAAGATGTCTC-3′ | |

| SNR47 ChIP primer set 1 (−328 to −179 of SNR47) | F | 5′-CTAGGCATCAGAACTGTCTCCGAAC-3′ |

| R | 5′-GACCGTATGGAAGACGTAGAGTGG-3′ | |

| SNR47 ChIP primer set 2 (−35 to +94 of SNR47) | F | 5′-CCTTATTATACATTCTCTTGGCGAGTGATC-3′ |

| R | 5′-GTGTTAAAAAGCTATTGTCAAAGTTTGTTTCC-3′ | |

| SNR47 ChIP primer set 4 (+175 to +334 of YDR042C) | F | 5′-CTCGAAAGTAGTTGGAGTACTGAGCG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GGGATGTGTGTAACCGATACTTCTGG-3′ | |

| SNR48 ChIP primer set 1 (−237 to −95 of SNR48) | F | 5′-GCGCGACATCATATACCTTTGTCCG-3′ |

| R | 5′-CTTGATATCGCACCCTTCTTTGCATTGCC-3′ | |

| SNR48 ChIP primer set 2 (−19 to +83 of SNR48) | F | 5′-CCTTTCATCCGTCTCGTTTATCATAATGATG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GAATGGAGAGTACTTAAACTTCACATCC-3′ | |

| SNR48 ChIP primer set 3 (+164 to +278 of SNR48) | F | 5′-GGCCTACGTAGAAGATGATGTAAAAGTAG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GTTTCCTATACGACGCGGACGAAGAG-3′ | |

| SNR48 ChIP primer set 4 (+333 to +478 of ERG25) | F | 5′-GGTCGAGGCCATCCCTATCTGGAC-3′ |

| R | 5′-GAGCCCAGTAATGCCATGTATCTTCC-3′ | |

| SNR47-YDR042C cDNA synthesis (+346 to +369 of SNR47) | 5′-GAGACCTAGTCGTTTGTTAGCTG-3′ | |

| SNR48-ERG25 cDNA synthesis (+560 to +586 of SNR48) | 5′-GAGGTTGCTGACTGTTATCGGTCATTG-3′ | |

| ACT1 cDNA synthesis (+534 to +553 of ACT1) | 5′-TGTCACCAACTGGGACGATA-3′ | |

| SNR47-YDR042C RT-PCR (+25 to +314 of SNR47) | F | 5′-CAACAACATGAATTTCTTCGTCCGAATCC-3′ |

| R | 5′-CCGCCTTTCTTCTTGGAAATTGGTAACAGG-3′ | |

| SNR48-ERG25 RT-PCR (+38 to +330 SNR48) | F | 5′-CTGGCATCTCTAATGTTAGGATGTGAAG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GGGTAACGAATGGATTGCGTAATATACCG-3′ | |

| SNR47 Northern probe (−143 to +94 of SNR47) | F | 5′-GGCTTCAGCTCCATATCTTTTG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GGAAACAAACTTTGACAATAGCTTTTTAACAC-3′ | |

| HIS3 Northern probe (+5 to +654 of HIS3) | F | 5′-CAGAGCAGAAAGCCCTAGTAAAGC-3′ |

| R | 5′-GAACACCTTTGGTGGAGGGAACATCG-3′ | |

| LEU2 Northern probe (+18 to +1068 of LEU2) | F | 5′-GATCGTCGTTTTGCCAGGTGACCACG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GGCGACAGCATCACCGACTTCGG-3′ |

Sequence locations are relative to transcript start sites described in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) (www.yeastgenome.org).

F, forward; R, reverse.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR).

Total RNA was isolated as described above and then subjected to DNase treatment using Ambion Turbo DNA-free (catalog no. AM1907) and RNase inhibitor (catalog no. AM2682). cDNA was generated using Ambion RETROscript kit (catalog no. AM1710) with random hexamers and oligo(dT) primers. Real-time PCRs utilized SYBR green (Fermentas) and high-efficiency primers downstream of snoRNAs (see Table 2 for information on primers used). Reactions were run using an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR system. Signals were normalized to that of ACT1 and the relative transcript level of wild-type cells was set at one. For controls, reactions lacking reverse transcriptase or template were performed. Error bars represent plus and minus 1 SEM. P values were determined using Student's t test. At least three independent biological replicates were used to generate cDNA, and qPCRs with each replicate were performed in triplicate.

Strand-specific reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

For each genotype, three independent biological replicates of total RNA were isolated and DNase treated as described above. Strand-specific cDNA synthesis reactions were performed on each sample using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) or with a reaction mixture with no reverse transcriptase as a control, as described before (64). These reaction mixtures contained both a primer designed to reverse transcribe transcripts that extended downstream of the snoRNA gene sequence and a primer to reverse transcribe the ACT1 mRNA. cDNA synthesis or control reaction mixtures with no reverse transcriptase were amplified by PCR. Two volumes of cDNA (1× and 6×) were used as the templates in PCRs to ensure signal linearity. Primers used for cDNA synthesis and PCRs can be found in Table 2.

ChIP assays.

Chromatin was isolated from cells grown to log phase, and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed as previously described (65). Chromatin was isolated in triplicate for each genotype. Immunoprecipitation (IP) of sonicated chromatin was performed with an anti-Rpb3 antibody (catalog no. W0012; NeoClone Biotechnology) and protein G-coupled Sepharose beads (protein G Sepharose 4 fast flow; GE Healthcare). For each experiment, a no-antibody control IP reaction was done with wild-type chromatin using just protein G beads. IP and input DNA were used as the templates in quantitative real-time PCR (performed as described above). The primers used in this study are shown in Table 2. The ChIP assays shown in Fig. 4 and 5 were performed at the same time; therefore, the wild-type and no-antibody controls are the same in both figures.

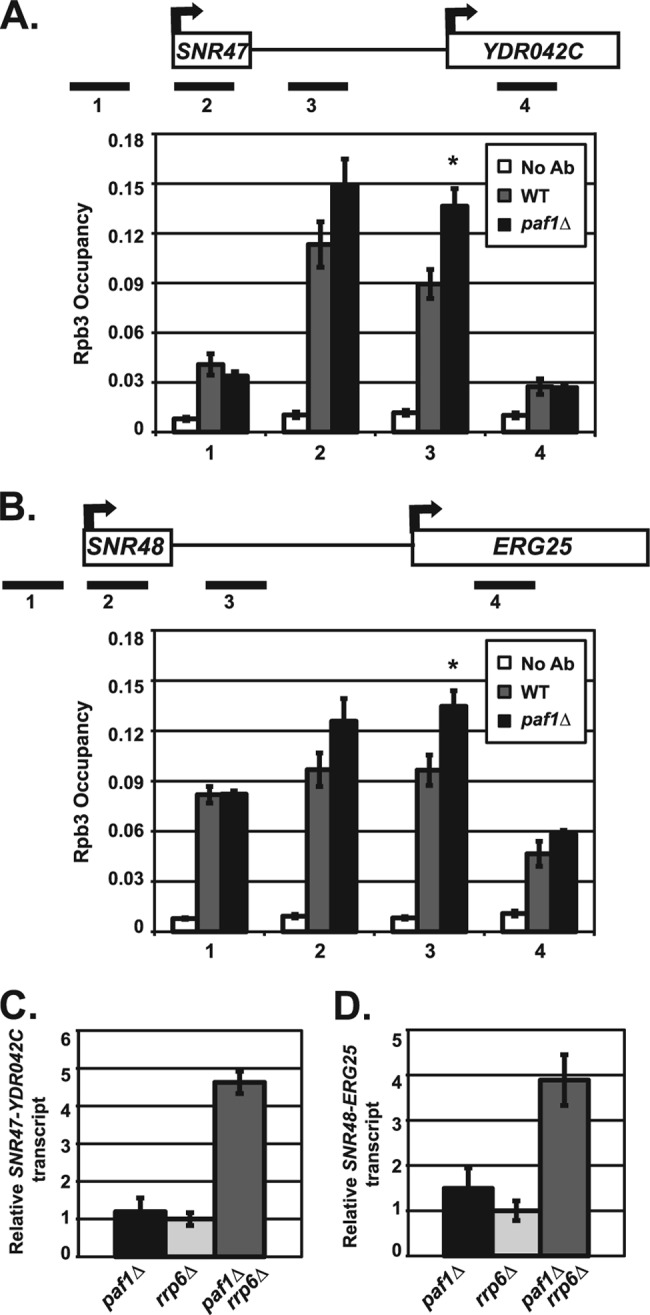

Fig 4.

Paf1 is required for proper transcription termination at snoRNAs. (A and B) ChIP analysis of Rpb3 occupancy in wild-type (KY1699) and paf1Δ (KY1700) cells. A no-antibody control (No Ab) was performed using wild-type (KY1699) cells. Quantification depicts average occupancy in three independent experiments as described in Materials and Methods. The SEMs are indicated by error bars, and asterisks indicate a P value of <0.05 relative to the value for the wild type. Rpb3 occupancy was examined near SNR47 (A) and SNR48 (B) at indicated locations (see Table 2 for primers used). (C and D) Quantification of Northern blot analyses of the extended SNR47 (C) and SNR48 (D) transcripts in paf1Δ (KY1700), rrp6Δ (KY1267), and paf1Δ rrp6Δ (KY2377) cells. The relative signal of rrp6Δ was set at 1, and the SEMs are indicated.

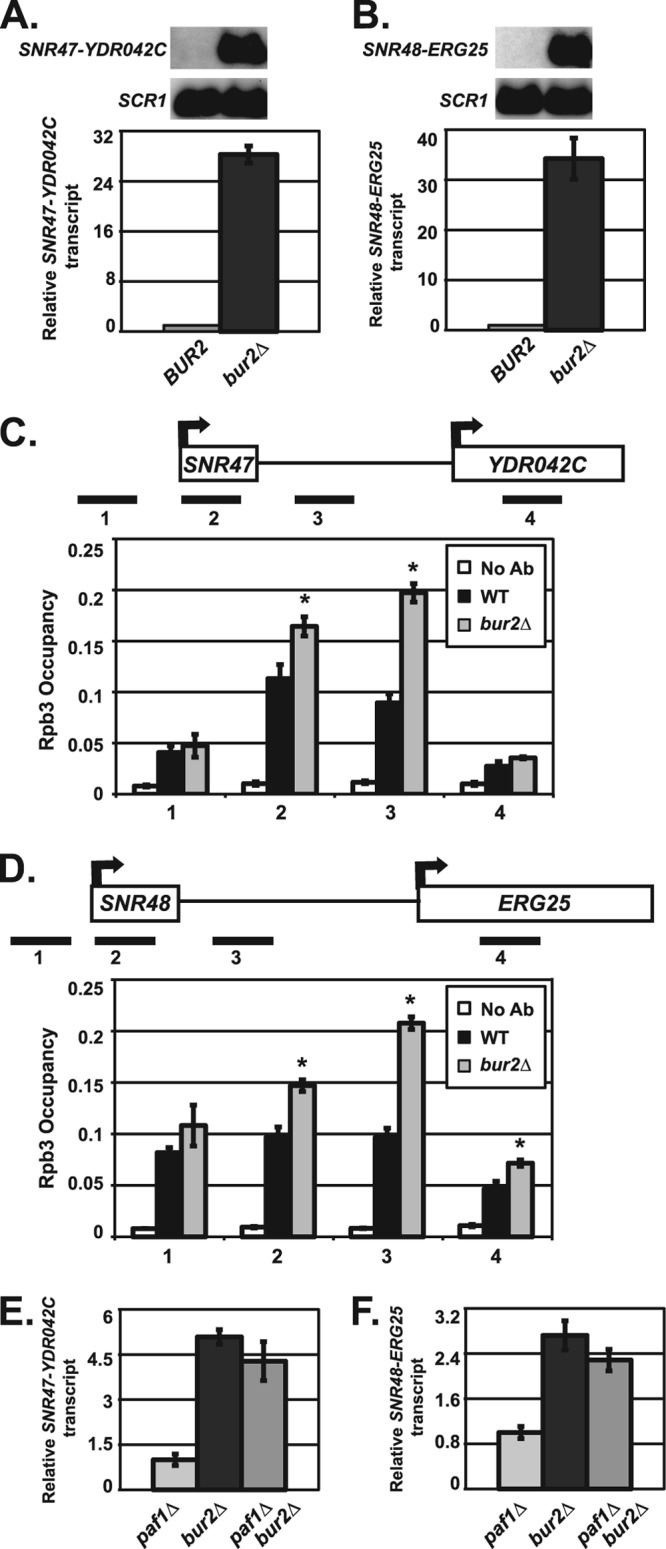

Fig 5.

Bur2 is required for proper snoRNA 3′-end formation. (A and B) Northern blot analyses were performed using RNA from wild-type (KY1699) and bur2Δ (KY1718) cells. SCR1 transcript levels serve as a loading control. For quantification, the relative signal of wild-type was set at 1. The SEMs of bur2Δ samples are indicated by the error bars. Representative Northern blot analysis and quantification of extended SNR47 (A) and SNR48 (B) transcripts are shown. (C and D) ChIP analysis of Rpb3 occupancy in wild-type (KY1699) and bur2Δ (KY1718) cells, which was examined near SNR47 (C) and SNR48 (D) at the indicated locations (see Table 2 for primers used). Quantification depicts average occupancy in three independent experiments. A no-antibody control (No Ab) was performed using wild-type (KY1699) cells. The SEMs are indicated by error bars, and asterisks indicate a P value of <0.05 relative to the value for the wild type. (E and F) Quantification of Northern blot analyses of extended SNR47 (E) and SNR48 (F) transcripts in paf1Δ (KY1700), bur2Δ (KY1718), and paf1Δ bur2Δ (KY1453) cells. The relative signal of paf1Δ was set at 1, and the SEMs are indicated.

High-density tiling array.

RNA was isolated from isogenic wild-type (KY2276) and paf1Δ (KY1702) cells grown in triplicate, treated with DNase (GE Healthcare), and purified with RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) as previously described (66). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers and oligo(dT) with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and purified with MinElute columns (Qiagen) (66). Because the cDNA samples were prepared in the absence of actinomycin D, analysis focused on transcripts encoded in the sense direction (67). cDNA fragmentation, labeling, and array hybridization were done as previously described (67). Arrays were designed in collaboration with Affymetrix (catalog no. PN 520055) and contain 6.5 million oligonucleotide features, 25-nucleotide probes spaced every 8 bp covering one strand of the S. cerevisiae genome sequence, and a second set of probes offset 4 bp to cover the other strand. High-density tiling arrays were analyzed and compared using Affymetrix tiling analysis software (TAS). The results from triplicate samples were averaged, the coding sequence of each ORF was divided into 80 equal-sized bins, and probes hybridizing to those regions were used to assign a hybridization signal intensity for each bin. Bin values were used to determine the mean and median signal intensity of each ORF (excluding dubious ORFs and mitochondrial genes) for the wild-type and paf1Δ samples. The comparison of wild-type and paf1Δ signals within ORFs can be found in Data set S1 in the supplemental material. To examine potential read-through snoRNA transcripts, bins of 10 bp each from sequences downstream of each genomic snoRNA gene were assigned a hybridization signal, with coordinates defined as in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD). We calculated the average distance from a genomic snoRNA gene to the next downstream sense ORF as ∼380 bp and the average distance from a genomic snoRNA gene to a downstream antisense ORF as ∼230 bp. Therefore, we examined 200 bp downstream to try to minimize the influence of transcription of downstream ORFs. Bin values were used to determine the mean and median signal intensity of 200 bp downstream of each snoRNA for wild-type and paf1Δ samples. For snoRNAs found within introns, 150 bp downstream was examined. The snoRNAs were ranked according to increased downstream transcription in the absence of PAF1 (Table 3; see Data set S1 in the supplemental material).

Table 3.

snoRNA genes with increased downstream transcription in the absence of PAF1a

| snoRNA gene | Avg fold change in paf1Δ |

|---|---|

| SNR48 | 8.60 |

| SNR71 | 6.28 |

| SNR161 | 4.77 |

| SNR45 | 4.31 |

| SNR60 | 3.86 |

| SNR81 | 3.75 |

| SNR85 | 3.52 |

| SNR64 | 3.06 |

| SNR32 | 2.89 |

| SNR79 | 2.83 |

| SNR191 | 2.79 |

| SNR51 | 2.37 |

| SNR68 | 2.36 |

| SNR47 | 2.33 |

| SNR53 | 2.31 |

| SNR42 | 2.29 |

| SNR33 | 2.18 |

| SNR56 | 2.13 |

| SNR54 | 2.12 |

| SNR5 | 1.90 |

| SNR69 | 1.86 |

| SNR86 | 1.79 |

| SNR82 | 1.73 |

| SNR34 | 1.72 |

This table lists snoRNA genes with at least a 1.7-fold increase in transcription downstream of the snoRNA gene in the absence of PAF1 compared to the value for the wild type. The average fold change in transcript levels for 150 to 200 bp downstream of each genomic snoRNA was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Expression array data accession number.

The expression array data are available at ArrayExpress under accession no. E-MTAB-1342.

RESULTS

Identification of snoRNAs that require Paf1 for proper 3′-end formation.

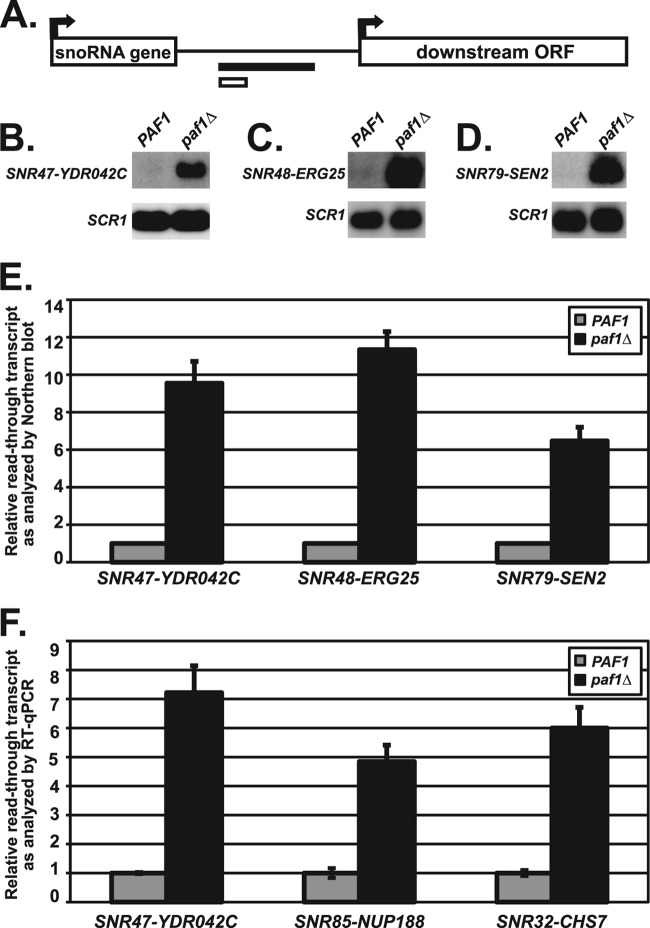

To define the scope of the involvement of the Paf1C in snoRNA 3′-end formation, we looked for snoRNA genes across the genome at which the absence of PAF1 leads to the synthesis of RNA transcripts that are extended at their 3′ ends. Analysis of high-density genome tiling arrays probed with labeled cDNA samples of transcripts prepared from wild-type and paf1Δ cells revealed many new examples of snoRNA genes affected by the deletion of PAF1 (see Materials and Methods). To identify Paf1-regulated snoRNAs, the ratio of transcript levels in paf1Δ cells relative to wild-type cells was calculated for sequences downstream of each snoRNA gene (see Materials and Methods; also see Data set S1 in the supplemental material). One-third of snoRNA loci were calculated to have at least a 1.7-fold increase in downstream transcription in the absence of PAF1 (Table 3; results for all snoRNAs are given in Data set S1). This list included the known Paf1-regulated gene SNR47 and many additional snoRNA genes, such as SNR48. These newly identified snoRNA targets of Paf1 represent both major functional classes of snoRNA genes (H/ACA box and C/D box). Using Northern blot analysis and RT-qPCR to measure the extended snoRNA transcripts in paf1Δ cells, we confirmed that the SNR47, SNR48, SNR79, SNR85, and SNR32 genes require Paf1 for proper RNA 3′-end formation (Fig. 1). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Paf1 is required for proper 3′-end formation of many snoRNAs throughout the yeast genome.

Fig 1.

snoRNAs require Paf1 for proper 3′-end formation. (A) Depiction of regions downstream of the snoRNA genes that were used to design probes for Northern blot analysis (black bar) or amplification for RT-qPCR analysis (white bar). See Table 2 for details of all primers used. (B to D) Representative Northern blot analyses of extended snoRNA in wild-type cells (strains KY1699 [B], KY2278 [C], and KY2048[D]) and paf1Δ cells (strains KY1700 [B], KY2279 [C], and KY2279 [D]). Extended snoRNA transcripts were detected with probes to the intergenic region between the indicated snoRNA gene and the downstream ORF. SCR1 transcript levels serve as a loading control. (E) Quantification of extended SNR47, SNR48, and SNR79 transcript levels performed by Northern blot analysis with the relative signals of wild-type cells set at 1 as described in Materials and Methods. The SEMs of paf1Δ samples are indicated by the error bars. (F) Quantification of transcript levels in the regions between SNR47-YDR042C, SNR85-NUP188, and SNR32-CHS7 in wild-type (KY2278) and paf1Δ (KY2279) cells as measured by RT-qPCR, with the relative signal of wild-type cells set at 1 as described in Materials and Methods. The SEMs are indicated by the error bars.

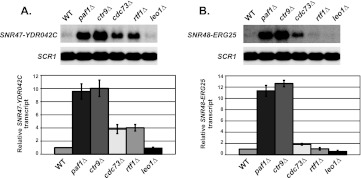

Analysis of Paf1C mutant strains reveals Paf1 and Ctr9 most strongly contribute to snoRNA 3′-end formation.

Given that not all functions of the Paf1C are shared equally by all complex members, we wanted to examine each component of the Paf1C for its contributions to accurate snoRNA 3′-end formation (1, 2). We chose to analyze a known Paf1 target gene, SNR47, and SNR48, the snoRNA gene showing the strongest dependence on Paf1 as measured by the array analysis. The results of our Northern blot analyses showed that Paf1 and Ctr9 seem to be the most critical Paf1C components for proper SNR47 RNA 3′-end formation, and in agreement with our previous observations, Cdc73 and Rtf1 play lesser but still significant roles at SNR47 (Fig. 2A) (44, 56). Similar to the results observed at the SNR47 gene paf1Δ and ctr9Δ cells had the highest levels of extended transcripts at SNR48, while leo1Δ cells behaved similarly to wild-type cells at both loci (Fig. 2). Unexpectedly, we could not detect a significant role for RTF1 at SNR48, whereas deleting CDC73 caused a small but reproducible increase in 3′-end extended SNR48 transcripts (Fig. 2B). The finding that the requirement for Rtf1 at SNR47 and SNR48 is different was surprising because we had previously shown that Rtf1-mediated histone H2B K123 monoubiquitylation is necessary for proper 3′-end formation of the snoRNAs SNR13 and SNR47, which both require Paf1 (56). The result at SNR48 indicates that H2B K123 ubiquitylation may not always have a role in 3′-end formation of snoRNAs targeted by Paf1.

Fig 2.

Subunits of the Paf1 complex demonstrate a range of contributions to snoRNA 3′-end formation. Northern blot analyses were performed using RNA from wild-type (WT) (KY1699), paf1Δ (KY1700), ctr9Δ (KY1705), cdc73Δ (KY1706), rtf1Δ (KY1704), and leo1Δ (KY1805) cells. SCR1 transcript levels serve as a loading control. For quantification, the relative signal of wild-type cells was set at 1 (as described in Materials and Methods) and the SEMs are indicated by the error bars. (A) Representative Northern blot analysis and the quantification of extended SNR47 transcripts (SNR47-YDR042C). (B) Representative Northern blot analysis and the quantification of extended SNR48 transcripts (SNR48-ERG25).

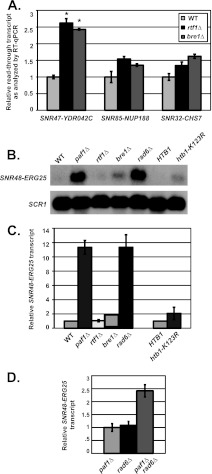

The requirement for Rtf1 and H2B K123 ubiquitylation in 3′-end formation of snoRNAs is locus dependent.

To test the idea that H2B K123 ubiquitylation may not always function in 3′-end formation of snoRNAs targeted by Paf1, we examined RNA 3′-end formation at other Paf1-targeted snoRNA genes for dependence on Rtf1 and H2B K123 ubiquitylation. Using RT-qPCR, we found that cells lacking RTF1 or the gene encoding the H2B K123 ubiquitin ligase, BRE1, have significant levels of read-through transcripts at SNR47, consistent with previous Northern blot analyses (Fig. 3A) (56). To determine whether histone H2B ubiquitylation also plays an important role in 3′-end formation of other Paf1-regulated snoRNAs, we tested for read-through transcripts in rtf1Δ and bre1Δ cells at the SNR85, SNR32, and SNR48 genes, all of which are Paf1 dependent. Unlike the significant levels of read-through transcripts observed at SNR47 in rtf1Δ and bre1Δ cells, we did not detect the same levels of read-through transcripts at these other snoRNA loci in cells lacking RTF1 or BRE1 (Fig. 3A to C). These results indicate a gene-dependent requirement among Paf1-regulated snoRNAs for the involvement of Rtf1-mediated H2B K123 ubiquitylation in RNA 3′-end formation. To better understand the different requirements for proper snoRNA 3′-end formation, we focused our studies on SNR47 and SNR48 as examples of Paf1-regulated snoRNA loci that are either dependent on Rtf1 or primarily Rtf1 independent.

Fig 3.

snoRNAs require Rad6 but exhibit differential requirements for Rtf1-mediated H2B K123 monoubiquitylation. (A) Quantification of extended SNR47 (SNR47-YDR042C), SNR85 (SNR85-NUP188), and SNR32 (SNR32-CHS7) transcript levels in wild-type (KY2048), rtf1Δ (KY2277), and bre1Δ (KY2046) cells as determined by RT-qPCR, with the relative signal of wild-type cells set at 1. The SEMs are indicated by the error bars. Values that are significantly different (P value of <0.05) from the wild-type value are indicated by an asterisk. (B) Representative Northern blot analysis of extended SNR48 transcripts (SNR48-ERG25) in wild-type (KY1699), paf1Δ (KY1700), rtf1Δ (KY2041), bre1Δ (KY1713), rad6Δ (KY1712), hta2Δ htb2Δ (KY2043), and htb1-K123R hta2Δ htb2Δ (KY2044) cells. SCR1 transcript levels serve as a loading control. (C) Quantification of SNR48-ERG25 transcript levels performed as described above for panel B. For the four strains on the left side of the graph, the relative signal of wild-type (KY1699) cells was set at 1. The transcript levels in htb1-K123R hta2Δ htb2Δ cells (graph, right side) were made relative to the levels in hta2Δ htb2Δ (KY2043) cells. The SEMs are indicated by error bars. (D) Quantification of Northern blot analyses of extended SNR48 transcripts (SNR48-ERG25) in paf1Δ (KY1700), rad6Δ (KY1712), and paf1Δ rad6Δ (KY1378) cells. The relative signal of paf1Δ was set at 1, and the SEMs are indicated.

A robust requirement for Rad6 in facilitating snoRNA 3′-end formation is independent of its H2B K123 ubiquitylation function.

Because the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Rad6 is required for Rtf1-mediated H2B K123 ubiquitylation, we examined whether the deletion of RAD6 affects 3′-end formation of SNR47 and SNR48 transcripts (19, 20). As with Rtf1 and Bre1, Rad6 was also shown to be necessary for proper 3′-end formation of SNR47 (56). Surprisingly, unlike RTF1 and BRE1, we found that RAD6 was strongly required for SNR48 3′-end formation, as rad6Δ cells have high levels of extended SNR48 transcripts (Fig. 3B and C). These results suggest that Rad6 has a role in RNA 3′-end formation at SNR48 that is independent of its role in H2B K123 ubiquitylation. Consistent with this idea, the htb1-K123R substitution caused only a slight increase in the levels of 3′-extended SNR48 transcripts (Fig. 3B and C). If the role of Rad6 in promoting RNA 3′-end formation at SNR48 is mainly independent of its H2B ubiquitylation function, we hypothesized that this role of Rad6 may also be independent of Paf1. To test this idea, we measured extended SNR48 transcripts in paf1Δ, rad6Δ, and paf1Δ rad6Δ cells, setting the extended transcript levels in paf1Δ cells to one for ease of comparison. Double mutant cells showed an additive defect in RNA 3′-end formation, suggesting that the function of Rad6 in SNR48 3′-end formation is also likely to be independent of Paf1 (Fig. 3D). Collectively, our results suggest that Rad6 can promote snoRNA formation through different mechanisms, which are either dependent or independent of Paf1C-regulated H2B K123 ubiquitylation.

Paf1 functions in transcription termination at SNR47 and SNR48.

The extended snoRNA transcripts could represent an RNA Pol II transcription termination defect in which the polymerase fails to terminate properly and continues transcription or could also reflect an RNA processing defect. Therefore, we analyzed the occupancy of Rpb3, an RNA Pol II subunit, across SNR47 and SNR48 in wild-type and paf1Δ cells. We found that cells lacking PAF1 had a significant increase in RNA Pol II levels downstream of SNR47 and SNR48 compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 4A and B). These results indicate that in cells lacking PAF1, inefficient transcription termination by RNA Pol II contributes, at least in part, to the formation of 3′-extended snoRNA transcripts. The extended snoRNA transcripts are aberrant RNAs and possible substrates of the nuclear exosome, of which Rrp6 is an exonuclease component (54). We observed higher levels of SNR47 and SNR48 read-through transcripts in paf1Δ rrp6Δ double mutant cells than in paf1Δ or rrp6Δ single mutant cells (Fig. 4C and D), suggesting that Paf1 likely functions independently of the exosome in preventing the accumulation of these extended transcripts. Taken together, our results show a requirement for Paf1 in RNA Pol II transcription termination at snoRNA genes.

Discovery of roles for the Bur1-Bur2 complex and Set2 methyltransferase in snoRNA termination.

Recruitment of the Paf1C to chromatin involves the Bur1-Bur2 complex (10–12, 18, 68). Consequently, we asked whether Bur1-Bur2 participates in snoRNA 3′-end formation at SNR47 and SNR48. Since BUR1 is essential for viability, we used bur2Δ cells to determine whether Bur1-Bur2 affects the synthesis of snoRNA transcripts. Interestingly, we found very high levels of 3′-extended transcripts at the Paf1-targeted snoRNAs SNR47 and SNR48 in the absence of BUR2 (Fig. 5A and B). In fact, bur2Δ cells had much higher levels of extended snoRNA transcripts than paf1Δ cells, indicating that the loss of BUR2 is more detrimental to snoRNA 3′-end formation than loss of PAF1. In agreement with this, we also observed a strong requirement for Bur2 in promoting RNA Pol II transcription termination at SNR47 and SNR48 (Fig. 5C and D). When we assessed the epistatic relationship between bur2Δ and paf1Δ, we found that cells lacking both BUR2 and PAF1 do not have increased read-through transcripts at SNR47 and SNR48 relative to bur2Δ cells (Fig. 5E and F). The lack of an additive defect in the paf1Δ bur2Δ double mutant indicates that Paf1 and Bur2 likely function in the same pathway. However, Bur1-Bur2 may have additional functions outside this pathway, as suggested by the robust snoRNA termination defects observed in bur2Δ strains. Alternatively, there may be a threshold effect on snoRNA termination defects so that a defect much greater than that caused by loss of BUR2 may cause inviability. Confirming that the extended SNR47 and SNR48 transcripts in paf1Δ and bur2Δ strains are indeed read-through snoRNA transcripts, we demonstrated that these transcripts contain both the snoRNA sequence and sequences downstream of the snoRNA, using strand-specific RT-PCR or Northern blot analysis (Fig. 6). Together, these results suggest a greater requirement for Bur1-Bur2 than Paf1C in proper snoRNA 3′-end formation, likely reflecting the multiple roles of Bur1-Bur2 in the phosphorylation and recruitment of proteins integral to transcription and histone modifications (11, 68–70).

In addition to facilitating snoRNA transcription termination, Bur1-Bur2 and Paf1 are also required for full levels of histone H3 K36 trimethylation. Therefore, we hypothesized that there might be a role for H3 K36 trimethylation in snoRNA 3′-end formation (18). Because H3 K36 methylation is catalyzed by the histone methyltransferase Set2, we used set2Δ cells to examine whether a lack of H3 K36 methylation adversely affects 3′-end formation of SNR47 transcripts. Using both Northern blot analyses and RT-qPCR, we uncovered a role for Set2 in SNR47 RNA 3′-end formation (Fig. 7A and B). Whereas cells lacking SET2 lose all H3 K36 methylation states (mono-, di-, and trimethylation), paf1Δ, ctr9Δ, and bur2Δ cells primarily lose H3 K36 trimethylation (18). Therefore, to mimic the H3 K36 methylation defect in these cells, we utilized a truncation allele of SET2, set2(1-261) (set2 gene that codes for amino acids 1 to 261 of the Set2 protein), which specifically abrogates H3 K36 trimethylation (60). We found that set2(1-261) cells show a defect in SNR47 3′-end formation similar to what we observed in set2Δ cells, suggesting that Set2-mediated trimethylation of H3 K36 is specifically important for snoRNA 3′-end formation (Fig. 7B). As independent confirmation of this result, cells lacking H3 K36 trimethylation were also impaired in termination within SNR47 sequences on an SNR47 termination reporter plasmid (Fig. 7C and D) (62).

Given that Paf1 is needed to promote full levels of H2B monoubiquitylation, which in turn is needed for efficient 3′-end formation of SNR47 RNA, we asked whether H3 K36 trimethylation and H2B K123 ubiquitylation are part of the same pathway that promotes snoRNA 3′-end formation by measuring the levels of SNR47 read-through transcripts in set2Δ bre1Δ cells. RT-qPCR showed that set2Δ bre1Δ cells have increased levels of extended SNR47 transcripts relative to single mutant set2Δ or bre1Δ cells (Fig. 7E). This finding suggests that Paf1 can promote two pathways of snoRNA 3′-end formation, one through histone H2B ubiquitylation and one through histone H3 K36 trimethylation. While these two pathways are likely to be independent on the basis of our results showing an additive increase in read-through transcripts in set2Δ bre1Δ cells, we cannot exclude the possibility of some cross talk in light of previous findings that H2B K123 ubiquitylation can impact H3 K36 methylation at certain genes (71). Cumulatively, our results indicate that Paf1C-dependent histone modifications can make independent contributions to snoRNA 3′-end formation and underlie locus-specific regulation.

DISCUSSION

Beyond Nrd1, Nab3, and Sen1, the proper 3′-end formation of snoRNAs requires the functions of additional factors such as the exosome, the TRAMP complex (Trf4-Air2-Mtr4p polyadenylation complex), and proteins that interact with RNA Pol II, including Pcf11, Ess1, and the Paf1C (44, 48, 51, 72–74). Here we have used high-resolution tiling arrays to investigate the requirement for Paf1C in snoRNA 3′-end formation on a genome-wide scale. Our list of snoRNA genes most strongly affected by the deletion of PAF1 encompasses one-third of the genomic snoRNA genes (Table 3) and likely underestimates the scope of the Paf1C effect, as a known Paf1C-regulated snoRNA gene, SNR13, fell below a 1.7-fold increase in calculated downstream transcription (see Data set S1 in the supplemental material). We verified the Paf1 dependence of a subset of these newly identified snoRNA gene targets of Paf1 and showed that the extended snoRNA transcripts in paf1Δ cells arise, at least in part, through defective transcription termination. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that Paf1 also contributes to the processing of snoRNAs, the results of our double mutant studies indicate that Paf1 and the nuclear exosome have nonoverlapping functions.

Our identification of new snoRNA targets of the Paf1C allowed us to define roles for additional factors in snoRNA 3′-end formation, such as Rad6, Bur1-Bur2, and Set2. Interestingly, we also found evidence indicating that regulation can exist in a locus-specific manner. For example, Rtf1, Bre1, and histone H2B ubiquitylation are important at SNR47 and SNR13 but are not as critical at SNR48, SNR32, and SNR85, yet all these genes require Paf1. Supporting our results, functions of the Paf1C in transcription elongation and nucleosome occupancy that are independent of histone modifications have been reported (15, 75). Furthermore, RNA transcripts do not always show the same extent of defects in NAB3, NRD1, and SEN1 mutants and strains with mutations in other known regulators, suggesting that more complex levels of regulation may exist at individual loci (48).

To identify snoRNA genes with increased levels of read-through transcription in paf1Δ cells and minimize any interfering effects of signals from downstream genes, we compared expression levels within 200 bp downstream of genomic snoRNA genes for the isogenic paf1Δ and wild-type strains (200 bp is lower than the average distance we calculated between genomic snoRNAs and downstream sense and antisense ORFs). However, it remained possible that signals from certain downstream genes were impacting our analysis. To address this concern, we analyzed two groups of snoRNA loci, which had either the highest or lowest levels of snoRNA read-through transcription in paf1Δ cells relative to wild-type cells, but we failed to find a correlation between the calculated level of transcription downstream of the snoRNA gene and the distance to the nearest ORF. In addition, we did not find a correlation between our calculated snoRNA read-through levels and the expression or stability of the closest downstream mRNA (data not shown). Therefore, while the predicted levels of read-through transcription at some individual snoRNA loci may be influenced by a downstream gene, we do not feel these effects impact the majority of the snoRNAs we have classified as Paf1 dependent.

Importantly, many of the newly identified snoRNA targets of Paf1 are regulated by the Nrd1-Nab3 pathway or are bound by those proteins (51, 62, 76, 77). We confirmed directly that the Nrd1 RNA binding protein is needed at SNR47 and SNR48 for RNA 3'-end formation (data not shown). Furthermore, only five snoRNAs on our list of Paf1-regulated snoRNA genes (Table 3) were not among the top 100 cross-linked RNAs for Nrd1 or Nab3 in transcriptome-wide binding analyses (76). Interestingly, over 60% of the snoRNAs that are in the bottom third when ranked by Paf1 dependence are not found among the top cross-linked RNAs for Nrd1 and Nab3. These observations indicate an enrichment of the most strongly Paf1-regulated snoRNAs among the collection of RNAs highly bound by Nrd1 and Nab3 and suggest that Paf1 is important for the termination of snoRNAs that are targeted by Nrd1 and Nab3. Further work will be required to mechanistically define how Paf1 functionally cooperates with these RNA binding proteins.

Although the loss of histone H2B K123 ubiquitylation caused by deletion of BRE1 or RTF1 or the H2B-K123R substitution does not strongly impact transcript synthesis at SNR48, rad6Δ cells show high levels of SNR48 read-through transcripts. Therefore, our data suggest that the Rad6 E2 ubiquitin conjugase may be working at some snoRNA genes in a manner independent of Paf1 and histone modifications, possibly implicating the other E3 ubiquitin ligase partners of Rad6 in snoRNA 3′-end formation. Specifically, Rad6 has been shown to work with Rad18 in DNA repair pathways and Ubr1 in gene regulation (78, 79). However, we found that cells lacking either UBR1 or RAD18 did not exhibit SNR48 read-through transcripts like rad6Δ cells (data not shown). It is currently unknown whether the primary contribution of Rad6 in SNR48 3′-end formation involves combinatorial effects of its various ubiquitin ligase partners and their cellular roles or other as yet undefined functions of Rad6.

We have demonstrated a previously undescribed role for Set2-mediated histone H3 K36 trimethylation in snoRNA 3′-end formation. This result may explain why Paf1 and Ctr9 are the most critical Paf1C subunits to snoRNA 3′-end formation through their actions promoting both histone H3 K36 and H2B K123 modifications. We expect that the histone modifications at these snoRNA genes are important to impact chromatin structure and recruit downstream effectors that may act directly on transcription termination or elongation (55). At SNR13 for example, the Buratowski lab found that Set1-mediated H3 K4 trimethylation is important for proper SNR13 transcript termination in cells bearing a nrd1 mutation, most likely through the recruitment of histone deacetylase complexes (HDAC) to SNR13 (55). Set2 can work in a similar manner at certain genes by affecting the recruitment of the HDAC Rpd3S (60, 80, 81). Given that Rpd3S recruitment is thought to be dependent on H3 K36 dimethylation, which is present in the paf1Δ, bur2Δ, and set2(1-261) cells that show a termination defect at SNR47, the role of Set2 in snoRNA termination likely involves a different function, which is more dependent on H3 K36 trimethylation. One possibility is that recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes such as Isw1b by H3 K36 trimethylation impacts snoRNA termination (82). We also established an important role for the Bur1-Bur2 CDK-cyclin complex in transcription termination at snoRNA genes by showing that bur2Δ cells have much higher levels of 3′-end extended snoRNAs than paf1Δ cells. We expect that Bur1-Bur2 is contributing to snoRNA termination through multiple functions, such as the phosphorylation of Rad6, Spt5, and the Rpb1 subunit of RNA Pol II, and also by promoting the recruitment of the Paf1C to chromatin for full levels of histone modifications (10–12, 68–70). In metazoans, the Paf1C also regulates histone modifications and transcription elongation and interacts with RNA 3′-end formation components. Therefore, enhancing our understanding of the functions and targets of the Paf1C in yeast may ultimately explain the critical importance of the Paf1C to development and disease progression in higher eukaryotes (2, 35).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Nislow lab for their technical advice and assistance and Jeff Corden and David Brow for sharing reagents and information. We also thank Allen Ho, Sarah Hainer, Kristin Klucevsek, Peggy Shirra, and Joe Martens for comments on the manuscript.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM52593 to K.M.A. and by award number F32GM093383 to B.N.T. from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. L.E.H., M.G., and C.N. are supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-84305).

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the views of the funding institutions.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01233-12.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crisucci EM, Arndt KM. 2011. The roles of the Paf1 complex and associated histone modifications in regulating gene expression. Genet. Res. Int. 2011:pii:707641 doi:10.4061/2011/707641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomson BN, Arndt KM. 6 September 2012. The many roles of the conserved eukaryotic Paf1 complex in regulating transcription, histone modifications, and disease states. Biochim. Biophys. Acta pii:S1874-9399(12)00154-X doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.011 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller CL, Jaehning JA. 2002. Ctr9, Rtf1, and Leo1 are components of the Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1971–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi X, Chang M, Wolf AJ, Chang CH, Frazer-Abel AA, Wade PA, Burton ZF, Jaehning JA. 1997. Cdc73p and Paf1p are found in a novel RNA polymerase II-containing complex distinct from the Srbp-containing holoenzyme. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1160–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi X, Finkelstein A, Wolf AJ, Wade PA, Burton ZF, Jaehning JA. 1996. Paf1p, an RNA polymerase II-associated factor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, may have both positive and negative roles in transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:669–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Squazzo SL, Costa PJ, Lindstrom DL, Kumer KE, Simic R, Jennings JL, Link AJ, Arndt KM, Hartzog GA. 2002. The Paf1 complex physically and functionally associates with transcription elongation factors in vivo. EMBO J. 21:1764–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim M, Ahn SH, Krogan NJ, Greenblatt JF, Buratowski S. 2004. Transitions in RNA polymerase II elongation complexes at the 3′ ends of genes. EMBO J. 23:354–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer A, Lidschreiber M, Siebert M, Leike K, Soding J, Cramer P. 2010. Uniform transitions of the general RNA polymerase II transcription complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:1272–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pokholok DK, Hannett NM, Young RA. 2002. Exchange of RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation factors during gene expression in vivo. Mol. Cell 9:799–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laribee RN, Krogan NJ, Xiao T, Shibata Y, Hughes TR, Greenblatt JF, Strahl BD. 2005. BUR kinase selectively regulates H3 K4 trimethylation and H2B ubiquitylation through recruitment of the PAF elongation complex. Curr. Biol. 15:1487–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Warfield L, Zhang C, Luo J, Allen J, Lang WH, Ranish J, Shokat KM, Hahn S. 2009. Phosphorylation of the transcription elongation factor Spt5 by yeast Bur1 kinase stimulates recruitment of the PAF complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:4852–4863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou K, Kuo WH, Fillingham J, Greenblatt JF. 2009. Control of transcriptional elongation and cotranscriptional histone modification by the yeast BUR kinase substrate Spt5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:6956–6961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu B, Mandal SS, Pham AD, Zheng Y, Erdjument-Bromage H, Batra SK, Tempst P, Reinberg D. 2005. The human PAF complex coordinates transcription with events downstream of RNA synthesis. Genes Dev. 19:1668–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Yamaguchi Y, Tsugeno Y, Yamamoto J, Yamada T, Nakamura M, Hisatake K, Handa H. 2009. DSIF, the Paf1 complex, and Tat-SF1 have nonredundant, cooperative roles in RNA polymerase II elongation. Genes Dev. 23:2765–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Guermah M, Roeder RG. 2010. The human PAF1 complex acts in chromatin transcription elongation both independently and cooperatively with SII/TFIIS. Cell 140:491–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rondon AG, Gallardo M, Garcia-Rubio M, Aguilera A. 2004. Molecular evidence indicating that the yeast PAF complex is required for transcription elongation. EMBO Rep. 5:47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tous C, Rondon AG, Garcia-Rubio M, Gonzalez-Aguilera C, Luna R, Aguilera A. 2011. A novel assay identifies transcript elongation roles for the Nup84 complex and RNA processing factors. EMBO J. 30:1953–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu Y, Simic R, Warner MH, Arndt KM, Prelich G. 2007. Regulation of histone modification and cryptic transcription by the Bur1 and Paf1 complexes. EMBO J. 26:4646–4656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng HH, Dole S, Struhl K. 2003. The Rtf1 component of the Paf1 transcriptional elongation complex is required for ubiquitination of histone H2B. J. Biol. Chem. 278:33625–33628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood A, Schneider J, Dover J, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. 2003. The Paf1 complex is essential for histone monoubiquitination by the Rad6-Bre1 complex, which signals for histone methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p. J. Biol. Chem. 278:34739–34742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dover J, Schneider J, Tawiah-Boateng MA, Wood A, Dean K, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. 2002. Methylation of histone H3 by COMPASS requires ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6. J. Biol. Chem. 277:28368–28371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krogan NJ, Dover J, Wood A, Schneider J, Heidt J, Boateng MA, Dean K, Ryan OW, Golshani A, Johnston M, Greenblatt JF, Shilatifard A. 2003. The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation. Mol. Cell 11:721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng HH, Robert F, Young RA, Struhl K. 2003. Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell 11:709–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun ZW, Allis CD. 2002. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature 418:104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Guermah M, McGinty RK, Lee JS, Tang Z, Milne TA, Shilatifard A, Muir TW, Roeder RG. 2009. RAD6-mediated transcription-coupled H2B ubiquitylation directly stimulates H3K4 methylation in human cells. Cell 137:459–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim T, Buratowski S. 2009. Dimethylation of H3K4 by Set1 recruits the Set3 histone deacetylase complex to 5′ transcribed regions. Cell 137:259–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin DG, Baetz K, Shi X, Walter KL, MacDonald VE, Wlodarski MJ, Gozani O, Hieter P, Howe L. 2006. The Yng1p plant homeodomain finger is a methyl-histone binding module that recognizes lysine 4-methylated histone H3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:7871–7879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minsky N, Shema E, Field Y, Schuster M, Segal E, Oren M. 2008. Monoubiquitinated H2B is associated with the transcribed region of highly expressed genes in human cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:483–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, Emre NC, Schreiber SL, Mellor J, Kouzarides T. 2002. Active genes are trimethylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419:407–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shema E, Tirosh I, Aylon Y, Huang J, Ye C, Moskovits N, Raver-Shapira N, Minsky N, Pirngruber J, Tarcic G, Hublarova P, Moyal L, Gana-Weisz M, Shiloh Y, Yarden Y, Johnsen SA, Vojtesek B, Berger SL, Oren M. 2008. The histone H2B-specific ubiquitin ligase RNF20/hBRE1 acts as a putative tumor suppressor through selective regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 22:2664–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akanuma T, Koshida S, Kawamura A, Kishimoto Y, Takada S. 2007. Paf1 complex homologues are required for Notch-regulated transcription during somite segmentation. EMBO Rep. 8:858–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K. 2006. Parafibromin/Hyrax activates Wnt/Wg target gene transcription by direct association with beta-catenin/Armadillo. Cell 125:327–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K. 2009. The role of Parafibromin/Hyrax as a nuclear Gli/Ci-interacting protein in Hedgehog target gene control. Mech. Dev. 126:394–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenney K, Gerber M, Ilvarsonn A, Schneider J, Gause M, Dorsett D, Eissenberg JC, Shilatifard A. 2006. Drosophila Rtf1 functions in histone methylation, gene expression, and Notch signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11970–11974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaudhary K, Deb S, Moniaux N, Ponnusamy MP, Batra SK. 2007. Human RNA polymerase II-associated factor complex: dysregulation in cancer. Oncogene 26:7499–7507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding L, Paszkowski-Rogacz M, Nitzsche A, Slabicki MM, Heninger AK, de Vries I, Kittler R, Junqueira M, Shevchenko A, Schulz H, Hubner N, Doss MX, Sachinidis A, Hescheler J, Iacone R, Anastassiadis K, Stewart AF, Pisabarro MT, Caldarelli A, Poser I, Theis M, Buchholz F. 2009. A genome-scale RNAi screen for Oct4 modulators defines a role of the Paf1 complex for embryonic stem cell identity. Cell Stem Cell 4:403–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L, Oliveira NM, Cheney KM, Pade C, Dreja H, Bergin AM, Borgdorff V, Beach DH, Bishop CL, Dittmar MT, McKnight A. 2011. A whole genome screen for HIV restriction factors. Retrovirology 8:94 doi:10.1186/1742-4690-8-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marazzi I, Ho JS, Kim J, Manicassamy B, Dewell S, Albrecht RA, Seibert CW, Schaefer U, Jeffrey KL, Prinjha RK, Lee K, Garcia-Sastre A, Roeder RG, Tarakhovsky A. 2012. Suppression of the antiviral response by an influenza histone mimic. Nature 483:428–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moniaux N, Nemos C, Schmied BM, Chauhan SC, Deb S, Morikane K, Choudhury A, Vanlith M, Sutherlin M, Sikela JM, Hollingsworth MA, Batra SK. 2006. The human homologue of the RNA polymerase II-associated factor 1 (hPaf1), localized on the 19q13 amplicon, is associated with tumorigenesis. Oncogene 25:3247–3257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Hughes CM, Nannepaga SJ, Shanmugam KS, Copeland TD, Guszczynski T, Resau JH, Meyerson M. 2005. The parafibromin tumor suppressor protein is part of a human Paf1 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:612–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nordick K, Hoffman MG, Betz JL, Jaehning JA. 2008. Direct interactions between the Paf1 complex and a cleavage and polyadenylation factor are revealed by dissociation of Paf1 from RNA polymerase II. Eukaryot. Cell 7:1158–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Nagaike T, Francis JM, Kaneko S, Glatt KA, Hughes CM, LaFramboise T, Manley JL, Meyerson M. 2009. The tumor suppressor Cdc73 functionally associates with CPSF and CstF 3′ mRNA processing factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:755–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penheiter KL, Washburn TM, Porter SE, Hoffman MG, Jaehning JA. 2005. A posttranscriptional role for the yeast Paf1-RNA polymerase II complex is revealed by identification of primary targets. Mol. Cell 20:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheldon KE, Mauger DM, Arndt KM. 2005. A requirement for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Paf1 complex in snoRNA 3′ end formation. Mol. Cell 20:225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esteller M. 2011. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12:861–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fromont-Racine M, Senger B, Saveanu C, Fasiolo F. 2003. Ribosome assembly in eukaryotes. Gene 313:17–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kishore S, Stamm S. 2006. The snoRNA HBII-52 regulates alternative splicing of the serotonin receptor 2C. Science 311:230–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colin J, Libri D, Porrua O. 2011. Cryptic transcription and early termination in the control of gene expression. Genet. Res. Int. 2011:653494 doi:10.4061/2011/653494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Houseley J, Tollervey D. 2009. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell 136:763–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuehner JN, Brow DA. 2008. Regulation of a eukaryotic gene by GTP-dependent start site selection and transcription attenuation. Mol. Cell 31:201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh N, Ma Z, Gemmill T, Wu X, Defiglio H, Rossettini A, Rabeler C, Beane O, Morse RH, Palumbo MJ, Hanes SD. 2009. The Ess1 prolyl isomerase is required for transcription termination of small noncoding RNAs via the Nrd1 pathway. Mol. Cell 36:255–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steinmetz EJ, Conrad NK, Brow DA, Corden JL. 2001. RNA-binding protein Nrd1 directs poly(A)-independent 3′-end formation of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Nature 413:327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Hoof A, Lennertz P, Parker R. 2000. Yeast exosome mutants accumulate 3′-extended polyadenylated forms of U4 small nuclear RNA and small nucleolar RNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:441–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vasiljeva L, Buratowski S. 2006. Nrd1 interacts with the nuclear exosome for 3′ processing of RNA polymerase II transcripts. Mol. Cell 21:239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terzi N, Churchman LS, Vasiljeva L, Weissman J, Buratowski S. 2011. H3K4 trimethylation by Set1 promotes efficient termination by the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31:3569–3583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomson BN, Davis CP, Warner MH, Arndt KM. 2011. Identification of a role for histone H2B ubiquitylation in noncoding RNA 3′-end formation through mutational analysis of Rtf1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 188:273–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winston F, Dollard C, Ricupero-Hovasse SL. 1995. Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast 11:53–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. 1988. Current protocols in molecular biology. Green Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rose MD, Winston F, Heiter P. 1991. Methods in yeast genetics: a laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 60.Youdell ML, Kizer KO, Kisseleva-Romanova E, Fuchs SM, Duro E, Strahl BD, Mellor J. 2008. Roles for Ctk1 and Spt6 in regulating the different methylation states of histone H3 lysine 36. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:4915–4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, III, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carroll KL, Pradhan DA, Granek JA, Clarke ND, Corden JL. 2004. Identification of cis elements directing termination of yeast nonpolyadenylated snoRNA transcripts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6241–6252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swanson MS, Malone EA, Winston F. 1991. SPT5, an essential gene important for normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encodes an acidic nuclear protein with a carboxy-terminal repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3009–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crisucci EM, Arndt KM. 2012. Paf1 restricts Gcn4 occupancy and antisense transcription at the ARG1 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:1150–1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shirra MK, Rogers SE, Alexander DE, Arndt KM. 2005. The Snf1 protein kinase and Sit4 protein phosphatase have opposing functions in regulating TATA-binding protein association with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae INO1 promoter. Genetics 169:1957–1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Juneau K, Palm C, Miranda M, Davis RW. 2007. High-density yeast-tiling array reveals previously undiscovered introns and extensive regulation of meiotic splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:1522–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perocchi F, Xu Z, Clauder-Munster S, Steinmetz LM. 2007. Antisense artifacts in transcriptome microarray experiments are resolved by actinomycin D. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:e128 doi:10.1093/nar/gkm683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wood A, Schneider J, Dover J, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. 2005. The Bur1/Bur2 complex is required for histone H2B monoubiquitination by Rad6/Bre1 and histone methylation by COMPASS. Mol. Cell 20:589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murray S, Udupa R, Yao S, Hartzog G, Prelich G. 2001. Phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain by the Bur1 cyclin-dependent kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4089–4096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qiu H, Hu C, Hinnebusch AG. 2009. Phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD by KIN28 enhances BUR1/BUR2 recruitment and Ser2 CTD phosphorylation near promoters. Mol. Cell 33:752–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wyce A, Xiao T, Whelan KA, Kosman C, Walter W, Eick D, Hughes TR, Krogan NJ, Strahl BD, Berger SL. 2007. H2B ubiquitylation acts as a barrier to Ctk1 nucleosomal recruitment prior to removal by Ubp8 within a SAGA-related complex. Mol. Cell 27:275–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arigo JT, Eyler DE, Carroll KL, Corden JL. 2006. Termination of cryptic unstable transcripts is directed by yeast RNA-binding proteins Nrd1 and Nab3. Mol. Cell 23:841–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim M, Vasiljeva L, Rando OJ, Zhelkovsky A, Moore C, Buratowski S. 2006. Distinct pathways for snoRNA and mRNA termination. Mol. Cell 24:723–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thiebaut M, Kisseleva-Romanova E, Rougemaille M, Boulay J, Libri D. 2006. Transcription termination and nuclear degradation of cryptic unstable transcripts: a role for the nrd1-nab3 pathway in genome surveillance. Mol. Cell 23:853–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pruneski JA, Hainer SJ, Petrov KO, Martens JA. 2011. The Paf1 complex represses SER3 transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by facilitating intergenic transcription-dependent nucleosome occupancy of the SER3 promoter. Eukaryot. Cell 10:1283–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Creamer TJ, Darby MM, Jamonnak N, Schaughency P, Hao H, Wheelan SJ, Corden JL. 2011. Transcriptome-wide binding sites for components of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae non-poly(A) termination pathway: Nrd1, Nab3, and Sen1. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002329 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jamonnak N, Creamer TJ, Darby MM, Schaughency P, Wheelan SJ, Corden JL. 2011. Yeast Nrd1, Nab3, and Sen1 transcriptome-wide binding maps suggest multiple roles in post-transcriptional RNA processing. RNA 17:2011–2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moertl S, Karras GI, Wismuller T, Ahne F, Eckardt-Schupp F. 2008. Regulation of double-stranded DNA gap repair by the RAD6 pathway. DNA Repair (Amst.) 7:1893–1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turner SD, Ricci AR, Petropoulos H, Genereaux J, Skerjanc IS, Brandl CJ. 2002. The E2 ubiquitin conjugase Rad6 is required for the ArgR/Mcm1 repression of ARG1 transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4011–4019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carrozza MJ, Li B, Florens L, Suganuma T, Swanson SK, Lee KK, Shia WJ, Anderson S, Yates J, Washburn MP, Workman JL. 2005. Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123:581–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li B, Jackson J, Simon MD, Fleharty B, Gogol M, Seidel C, Workman JL, Shilatifard A. 2009. Histone H3 lysine 36 dimethylation (H3K36me2) is sufficient to recruit the Rpd3s histone deacetylase complex and to repress spurious transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 284:7970–7976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smolle M, Venkatesh S, Gogol MM, Li H, Zhang Y, Florens L, Washburn MP, Workman JL. 2012. Chromatin remodelers Isw1 and Chd1 maintain chromatin structure during transcription by preventing histone exchange. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:884–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.