Abstract

Different forms of nitrogen (N) fertilizer affect disease development; however, this study investigated the effects of N forms on the hypersensitivity response (HR)—a pathogen-elicited cell death linked to resistance. HR-eliciting Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola was infiltrated into leaves of tobacco fed with either  or

or  . The speed of cell death was faster in

. The speed of cell death was faster in  -fed compared with

-fed compared with  -fed plants, which correlated, respectively, with increased and decreased resistance. Nitric oxide (NO) can be generated by nitrate reductase (NR) to influence the formation of the HR. NO generation was reduced in

-fed plants, which correlated, respectively, with increased and decreased resistance. Nitric oxide (NO) can be generated by nitrate reductase (NR) to influence the formation of the HR. NO generation was reduced in  -fed plants where N assimilation bypassed the NR step. This was similar to that elicited by the disease-forming P. syringae pv. tabaci strain, further suggesting that resistance was compromised with

-fed plants where N assimilation bypassed the NR step. This was similar to that elicited by the disease-forming P. syringae pv. tabaci strain, further suggesting that resistance was compromised with  feeding. PR1a is a biomarker for the defence signal salicylic acid (SA), and expression was reduced in

feeding. PR1a is a biomarker for the defence signal salicylic acid (SA), and expression was reduced in  -fed compared with

-fed compared with  fed plants at 24h after inoculation. This pattern correlated with actual SA measurements. Conversely, total amino acid, cytosolic and apoplastic glucose/fructose and sucrose were elevated in

fed plants at 24h after inoculation. This pattern correlated with actual SA measurements. Conversely, total amino acid, cytosolic and apoplastic glucose/fructose and sucrose were elevated in  - treated plants. Gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy was used to characterize metabolic events following different N treatments. Following

- treated plants. Gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy was used to characterize metabolic events following different N treatments. Following  nutrition, polyamine biosynthesis was predominant, whilst after

nutrition, polyamine biosynthesis was predominant, whilst after  nutrition, flux appeared to be shifted towards the production of 4-aminobutyric acid. The mechanisms whereby

nutrition, flux appeared to be shifted towards the production of 4-aminobutyric acid. The mechanisms whereby  feeding enhances SA, NO, and polyamine-mediated HR-linked defence whilst these are compromised with

feeding enhances SA, NO, and polyamine-mediated HR-linked defence whilst these are compromised with  , which also increases the availability of nutrients to pathogens, are discussed.

, which also increases the availability of nutrients to pathogens, are discussed.

Key words: ammonium, hypersensitive response, nitrate, nitric oxide, Pseudomonas, tobacco

Introduction

The anthropogenic application of nitrogen (N) fertilizer has been a major factor in modern high crop yields and plant quality (Tilman, 1999; Hajjar and Hodgkin, 2007). This has resulted in a doubling of N loads to soil since the beginning of the 20th century (Green et al., 2004) and is continuing with total global N inputs in the region of 150 teragrams of N year–1 (Schlesinger, 2009). In agricultural soils, N is supplied in the form of nitrate ( ), ammonium (

), ammonium ( ), or a combination of both. Plants will reduce

), or a combination of both. Plants will reduce  using nitrate reductase (NR) to generate

using nitrate reductase (NR) to generate  , which is further reduced to

, which is further reduced to  , which can be directly assimilated by glutamine synthetase (GS) to form glutamine.

, which can be directly assimilated by glutamine synthetase (GS) to form glutamine.  can also enter the soil biosystem via fixation of atmospheric N, as well as by decomposition of organic matter by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi.

can also enter the soil biosystem via fixation of atmospheric N, as well as by decomposition of organic matter by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi.  can be oxidized to first

can be oxidized to first  and subsequently to

and subsequently to  by the nitrification pathway. Given its widespread use, the agricultural impact of N nutrition on disease development has been extensively examined (Huber and Watson, 1974). However, here we have assessed the effects of the form of N nutrition on a form of resistance to pathogens that is typified by the hypersensitivity response (HR).

by the nitrification pathway. Given its widespread use, the agricultural impact of N nutrition on disease development has been extensively examined (Huber and Watson, 1974). However, here we have assessed the effects of the form of N nutrition on a form of resistance to pathogens that is typified by the hypersensitivity response (HR).

When a pathogen first comes into contact with a host, it is assumed to be nutrient starved, meaning that rapid assimilation of host nutrients is essential for successful pathogenesis (Snoeijers et al., 2000). Equally, the host seeks to either prevent this and/or mobilize its nutrients to further defence responses. These opposing aims are well exemplified in the changes in N metabolism seen during plant–pathogen interactions. The accumulation of 4-aminobutyric acid (GABA)—a glutamate-derived metabolite—has been observed in response to a range of biotic stresses (Kinnersley and Turano, 2000). In the case of infection of tomato by Cladosporium fulvum, GABA has been shown to be utilized by the pathogen (Kinnersley and Turano, 2000; Solomon and Oliver, 2001), but from the perspective of the host, GABA participates in the so-called ‘GABA shunt’, allowing a direct link between reduced N in the host (as represented in GABA) and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Fromm and Bouche, 2004). This may occur due to the host’s increased bioenergetic requirements following infection (Fait et al., 2008). Some N manipulation can be more obviously favourable to the pathogen. For example, several genes usually associated with N mobilization during senescence, such as specific forms of GS, as well as some senescence-associated genes, are induced during disease (Bender et al., 1999; Pontier et al., 1999; Quirino et al., 1999; Masclaux et al., 2000). Similarly, infection of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) by the anthracnose pathogen Colletotrichum lindemuthianum induces GS expression (Tavernier et al., 2007). Furthermore, as C:N assimilatory links are well established (Fritz et al., 2006a ; Bauwe et al., 2010; Sweetlove et al., 2010), it is unsurprising that N changes correlate with increase host-cell sugar export to influence plant disease susceptibility (Tadege et al., 1998; Thibaud et al., 2004). Thus, whilst N fertilizers improve the nutrient status of the host, they can also promote disease (Huber and Watson, 1974).

Co-application of biocides with N fertilizers may appear to be a worthwhile agricultural strategy to negate any disease-promoting effects of the latter. However, there is increasing pressure to reduce the use of a range of biocides in agriculture (Gullino and Kuijpers, 1994) and to exploit endogenous plant defence mechanisms in plant breeding and agricultural practice. The introgression of resistance (R) genes into elite crop germplasm has been, and remains, an important approach to securing yields (Rommens and Kishore, 2000). One consequence of R gene-mediated resistance is often the elicitation of a programmed cell death—the hypersensitivity response (HR). N effects appear to be a facet of HR-mediated resistance, as elicitation of the HR induces GS and glutamate dehydrogenase via the defence hormone salicylic acid (SA) and could aid in mobilizing N away from the pathogen (Pageau et al., 2006). Another N component in plant defence is nitric oxide (NO), which is a major contributor to the formation of the HR (Delledonne et al., 1998, Gupta, 2011). Crucially, under aerobic conditions, NO is generated byNR acting on the reduced product of a NADPH-dependent nitrite reductase (Molodo et al., 2005; Gupta et al., 2011). As NR cannot act on  , the type of N nutrition (

, the type of N nutrition ( or

or  ) would influence whether NO were generated. NO initiates the biosynthesis of SA via a signalling route that involves cyclic GMP and cyclic ADP-ribose (Durner and Klessig, 1999). SA is an important stress signal, and is known to play important roles in HR-type plant defence (Mur et al., 2000, 2008), thermotolerance (Clarke et al., 2004), chilling (Scott et al., 2004), and stomatal regulation (Khokon et al., 2011). The physiological link between NO and SA effects have been shown in localized plant defence (Klessig et al., 2000), systemic acquired resistance (Espunya et al., 2012), and stomatal opening (Sun et al., 2010).

) would influence whether NO were generated. NO initiates the biosynthesis of SA via a signalling route that involves cyclic GMP and cyclic ADP-ribose (Durner and Klessig, 1999). SA is an important stress signal, and is known to play important roles in HR-type plant defence (Mur et al., 2000, 2008), thermotolerance (Clarke et al., 2004), chilling (Scott et al., 2004), and stomatal regulation (Khokon et al., 2011). The physiological link between NO and SA effects have been shown in localized plant defence (Klessig et al., 2000), systemic acquired resistance (Espunya et al., 2012), and stomatal opening (Sun et al., 2010).

Here, we characterized the influence of  or

or  nutrition on HR-mediated resistance, focusing on the impact on NO, SA, and primary plant metabolism. We have shown how NO3 feeding augments HR-mediated resistance, whilst NH4 can compromise defence by mechanisms, which include increasing nutrient availability for the pathogen.

nutrition on HR-mediated resistance, focusing on the impact on NO, SA, and primary plant metabolism. We have shown how NO3 feeding augments HR-mediated resistance, whilst NH4 can compromise defence by mechanisms, which include increasing nutrient availability for the pathogen.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Tobacco seeds cv. Gatersleben were germinated on vermiculite in a day/night regime of 14/10h, 24/20 °C, a relative humidity of 80%, and photosynthetic photon flux density (PPDF) of 350–400 µmol m−2 s−1. After 3 weeks, the plants were transferred to hydroponic culture for an additional 4–8 weeks. Plastic pots, each containing 1.8 l of nutrient solution, were kept in a growth chamber with artificial illumination (HQI 400W; Schreder, Winterbach, Germany) at PPFD of 300 µmol m−2 s−1 and with 16h daily light periods. The day/night temperature regime of the chamber was 24/20 °C. Nutrient solution was prepared according to the method of Planchet et al. (2005). The  nutrient solution (pH 6.3) contained 3mM KNO3, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgSO4, 25 µM NaFe-EDTA, 0.5mM K2HPO4, 1mM KH2PO4, and trace elements according to Planchet et al. (2005). For

nutrient solution (pH 6.3) contained 3mM KNO3, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgSO4, 25 µM NaFe-EDTA, 0.5mM K2HPO4, 1mM KH2PO4, and trace elements according to Planchet et al. (2005). For  -fed plants, the nutrient solution was: 3mM NH4Cl, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgSO4, 25 µM NaFe-EDTA, 0.5mM K2HPO4, 1mM KH2PO4, and trace elements. The composition of the nutrient solution for the NR-deficient Nia30 Gatersleben mutant was: 1mM KNO3, 3mM NH4Cl initially for 1 week and 3mM NH4Cl thereafter, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgSO4, 25 µM NaFe-EDTA, 2mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, and trace elements. For all these conditions, nutrient solutions were changed three times a week. Some tobacco plants were also grown in low-nutrient John Innes Seed Compost (William Sinclair Horticulture, UK) and watered with

-fed plants, the nutrient solution was: 3mM NH4Cl, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgSO4, 25 µM NaFe-EDTA, 0.5mM K2HPO4, 1mM KH2PO4, and trace elements. The composition of the nutrient solution for the NR-deficient Nia30 Gatersleben mutant was: 1mM KNO3, 3mM NH4Cl initially for 1 week and 3mM NH4Cl thereafter, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgSO4, 25 µM NaFe-EDTA, 2mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, and trace elements. For all these conditions, nutrient solutions were changed three times a week. Some tobacco plants were also grown in low-nutrient John Innes Seed Compost (William Sinclair Horticulture, UK) and watered with  or

or  nutrient solutions (as detailed above) every 2 d as appropriate to the experiment. In experiments where compost-grown plants were used, this is indicated in the text.

nutrient solutions (as detailed above) every 2 d as appropriate to the experiment. In experiments where compost-grown plants were used, this is indicated in the text.

Growth of plant pathogens, plant inoculation, and estimation of in planta bacterial populations

Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola strain 1448A (Psph) and P. syringae pv. tabaci strain 4152 (Pt) (both rifampicin resistant) were grown at 28 °C in King’s B medium containing rifampicin (10mg ml–1) (Zeier et al., 2004). Overnight exponential-phase cultures were washed three times with autoclaved 10mM MgCl2 and diluted to a final concentration of 105 cells ml–1. The bacterial suspensions were infiltrated from the abaxial side into a sample leaf using a 1ml syringe with a needle. Control inoculations were performed with 10mM MgCl2. In planta bacterial population sizes were assessed to indicate the extent of resistance/susceptibility exhibited by the host. Cores of 1cm discs (0.79cm2) were taken using a cork borer and ground down in a mortar and pestle and resuspended in 1ml of 10mM MgCl2. Serial dilutions of the slurry were plated on rifampicin (10mg ml–1)-supplemented King’s B medium and incubated at 30 °C until colonies formed. Based on the number of colonies and dilution factor, the original in planta population was calculated.

Estimations of electrolyte leakage

Loss of membrane integrity was estimated by electrolyte leakage in 1cm diameter cores as described by Mur et al. (1997). This measure was used to suggest the kinetics of cell death.

NO measurement

Quantum cascade laser (QCL)

The use of a QCL to detect NO has been described recently (Mur et al., 2011). The system allows real-time NO measurements with a detection limit of 0.8 ppbv s–1 (Cristescu et al., 2008). Before each experiment, the QCL was calibrated against gas mixtures prepared from a reference gas mixture (100 ppbv NO in N2) diluted in NO-free air to cover the range 10–100 ppbv. Infiltrated tobacco leaves that had been detached at the petiole were placed in a 200ml glass cuvette in an inlet and outlet carrier flow of air via gas tubing, and NO production was monitored at a controlled continuous flow rate of 1 l h–1. During NO measurements, the leaves in the cuvette were maintained in a Sanyo MLR-350 environmental test chamber at 20 °C under a 16h light (200 µmol m−2 s−1)/ 8h dark regime. The humidity within the cuvette was not controlled or measured.

Multiple cuvettes could be monitored in sequence, each being measured for ~13min. The laser light emitted by the QCL around 1850cm−1 passed through a multi-pass absorption cell where the NO molecules were transported via the gastube. The intensity of the transmitted laser light was attenuated due to the NO absorption of the light in the multi-pass cell (effective path length=76 m), following the Beer–Lambert law. The detected signal depended on the laser intensity before the multi-pass cell, the absorption length, and the absorption coefficient of NO at the particular wavelength. The NO concentration was calculated by measuring attenuation of the light coming into the cell relative to the transmitted light (after the cell).

Chemiluminescence

For experiments with detached leaves, the leaves were cut off from the plant and placed in nutrient solution, where the petiole was cut off a second time below the solution surface. The leaves (petiole in nutrient solution) were placed in a transparent lid chamber with 2 or 4 l of air volume, depending on leaf size and number. A constant flow of measuring gas (purified air or N2) at 1.5 l min−1 was pulled through the chamber and subsequently through the chemiluminescence detector (CLD 770 AL ppt; Eco-Physics, Dürnten, Switzerland; detection limit 20 ppt; 10 s time resolution) by a vacuum pump connected to an ozone destroyer. The ozone generator of the chemiluminescence detector was supplied with dry oxygen (99%). The measuring gas (air or N2) was made NO free by conducting it through a custom-made charcoal column (1 m long, 3cm internal diameter, particle size 2mm). Calibration was carried out routinely with NO-free air (0 ppt NO) and with various concentrations of NO (1–35 ppb) adjusted by mixing the calibration gas (500 ppb NO in N2; Messer Griesheim, Darmstadt, Germany) with NO-free air. Flow controllers (FC-260; Tylan General, Eching, Germany) were used to adjust all gas flows. Light was provided by a 400W HQI lamp (Schreder) above the cuvette. Quantum flux density could be adjusted within limits (150–400 µmol m−2 s−1 PPDF) by changing the distance between thelamp and cuvette. The air temperature in the cuvette was monitored continuously and was usually about 20 °C in the dark and 23–25 °C in the light.

Expression profiling by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Expression analysis was performed using an expression profiling platform of the response of eight defence genes against Pseudomonas in tobacco. Primer sequences were designed using QuantPrime (Arvidsson et al., 2008). Fully expanded leaves were collected and pooled from six plants in each treatment. Total RNA was purified using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, http://www.qiagen.com) and DNase digestion was performed with a Turbo DNA-free Kit (Ambion, http://www.ambion.com/). Four micrograms of total RNA was used as template for first-strand cDNA synthesis with a RevertAid cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, http://www.fermentas.com/). cDNA (20ng) was used for qRT-PCR with Power SYBR Green reagent performed on an ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, http://www.appliedbiosystems.com/). Data were analysed with the 7900 version 2.0.3 evaluation software (Applied Biosystems). The fold change in the target genes was normalized to a reference gene, elongation factor 1a (EF1a). Fold expression relative to control plants was determined using the ΔΔC T method, as described by Libault et al. (2007). Three biological experiments (with two independent replicates for each experiment) were performed for each treatment. Comparisons of gene expression between the different treatments compared with the control were conducted using a t-test.

Extraction of apoplastic fluid

Apoplastic fluid was extracted from tobacco leaves by direct centrifugation as described by Dannel et al. (1995), with some modifications. Leaves were cut at the base of the petiole with a sharp razor blade and the petiole immediately immersed in deionized water. Each leaf was then rolled into several folds and placed into a plastic syringe (25ml) with the petiole side at the base of the syringe. The syringe was placed in a 50ml centrifuge tube. Leaf-filled syringes were centrifuged at 4 °C at 4000g and apoplastic fluid was collected from the bottom of the centrifuge tube.

Targeted sugar and total amino acid measurements

Major sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) were separated by anion-exchange chromatography (0.1 N NaOH as the eluent) on a Carbopac column plus pre-column and detected directly by pulsed amperometry (Dionex 4500i; Dionex, Idstein, Germany). Total amino acids were measured by HPLC, as described by Mahmood et al. (2002).

Metabolite profiling

Gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis was performed as described previously (Lisec et al., 2006). Six replicates each consisting of six pooled plants obtained from two independent experiments were subjected to GC-MS analysis. Metabolite levels were determined in a targeted fashion using the TargetSearch software package (Cuadros-Inostroza et al., 2009). Metabolites were selected by comparing their retention indexes (±2 s) and spectra (similarity >85%) against compounds stored in the Golm Metabolome Database (Kopka et al., 2005). This resulted in 150 metabolites, which were kept in the data matrix. Each metabolite was represented by the observed ion intensity of a selected unique ion, which allowed relative quantification between groups. Metabolite data were log10-transformed to improve normality (Steinfath et al., 2008) and normalized to show identical medium peak sizes per sample group.

Data analyses

Metabolite data were analysed by multivariate approaches using Pychem software (Jarvis et al., 2006). Where the statistical test for significant was between two groups, t-tests were used,, but when comparing between three or more groups Tukey’s multiple pairwise comparison test was employed using Minitab version 14 (Minitab, Coventry, UK). The Tukey test outputs represent adjusted P values based on significant differences between differing datasets. Datasets where there were no significant differences are indicated on the figures using alphabetical indicators.

Results

The form of N nutrition influences HR development induced by Psph

To investigate the role of  and

and  nutrition on HR-associated defence, tobacco cv. Gatersleben plants were grown in hydroponic solutions containing either 3mM KNO3 (referred to as

nutrition on HR-associated defence, tobacco cv. Gatersleben plants were grown in hydroponic solutions containing either 3mM KNO3 (referred to as  -fed plants) or 3mM NH4Cl (referred to as

-fed plants) or 3mM NH4Cl (referred to as  -fed plants) for 1 week and then challenged with Psph. Within 24h post-inoculation (p.i.), leaf discoloration was observed at the inoculation sites of

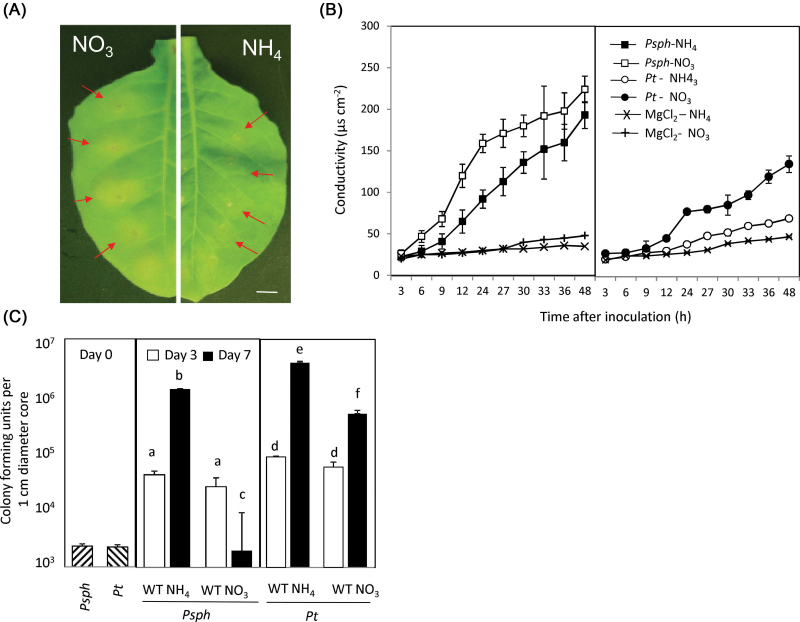

-fed plants) for 1 week and then challenged with Psph. Within 24h post-inoculation (p.i.), leaf discoloration was observed at the inoculation sites of  -treated plants only (Fig. 1A). To quantify the loss of membrane integrity, which is linked to cell death, electrolyte leakage from isolated explants of Psph-challenged tissue was assessed (Fig. 1B). Leakage was more rapid in

-treated plants only (Fig. 1A). To quantify the loss of membrane integrity, which is linked to cell death, electrolyte leakage from isolated explants of Psph-challenged tissue was assessed (Fig. 1B). Leakage was more rapid in  -fed compared with

-fed compared with  -fed plants, which tallied with the observed differences in macrolesion formation (Fig. 1A). To link these changes with host resistance in planta, Psph population sizes were determined (Fig. 1C). No significant differences in bacterial numbers within

-fed plants, which tallied with the observed differences in macrolesion formation (Fig. 1A). To link these changes with host resistance in planta, Psph population sizes were determined (Fig. 1C). No significant differences in bacterial numbers within  -fed compared with

-fed compared with  -fed plants were observed, and in both, growth from the initial population (0 d p.i.) was evident. However, at 7 days p.i., whereas in

-fed plants were observed, and in both, growth from the initial population (0 d p.i.) was evident. However, at 7 days p.i., whereas in  -fed plants there was a significant (P <0.001) increase in bacterial numbers compared with 3 days p.i., with NO3-fed plants the bacterial numbers were reduced. This delay in the HR observed for

-fed plants there was a significant (P <0.001) increase in bacterial numbers compared with 3 days p.i., with NO3-fed plants the bacterial numbers were reduced. This delay in the HR observed for  -treated plants was linked with increased Psph growth in planta (Fig. 1C), suggesting that resistance was compromised. However, with NO3-fed plants, there was a dramatic reduction in bacterial numbers at 7 days p.i., which seemed to be associated with a more rapid cell death (Fig. 1B). To investigate further whether HR-linked resistance was comprised in Psph in

-treated plants was linked with increased Psph growth in planta (Fig. 1C), suggesting that resistance was compromised. However, with NO3-fed plants, there was a dramatic reduction in bacterial numbers at 7 days p.i., which seemed to be associated with a more rapid cell death (Fig. 1B). To investigate further whether HR-linked resistance was comprised in Psph in  -fed tobacco, comparisons were made with electrolyte leakage and bacterial populations in leaves inoculated with the virulent bacterial pathogen Pt in tobacco plants fed with either

-fed tobacco, comparisons were made with electrolyte leakage and bacterial populations in leaves inoculated with the virulent bacterial pathogen Pt in tobacco plants fed with either  or

or  (Fig. 1B and C). The rate of electrolyte leakage in explants from Pt-inoculated leaves was slower than that seen in explants from Psph-challenged

(Fig. 1B and C). The rate of electrolyte leakage in explants from Pt-inoculated leaves was slower than that seen in explants from Psph-challenged  -fed or

-fed or  -fed plants. Similarly, Pt populations were more abundant than Psph in any tobacco plants. Taken together, these results indicated that HR resistance to Psph was reduced but not abolished in

-fed plants. Similarly, Pt populations were more abundant than Psph in any tobacco plants. Taken together, these results indicated that HR resistance to Psph was reduced but not abolished in  -fed tobacco. Interestingly, Pt populations in

-fed tobacco. Interestingly, Pt populations in  -fed tobacco were significantly (P < 0.001) reduced compared with

-fed tobacco were significantly (P < 0.001) reduced compared with  -fed plants but were significantly (P < 0.001) greater than any measured for Psph (Fig. 1C).

-fed plants but were significantly (P < 0.001) greater than any measured for Psph (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Forms of N fertilizer influence the HR elicited by Psph in tobacco. (A) Lesion development (arrows) at 24h p.i. of  -fed or

-fed or  -fed tobacco leaves with avirulent Psph. Plants were grown hydrophonically as described in Materials and methods, and 1 week prior to inoculation, the plants were transferred to

-fed tobacco leaves with avirulent Psph. Plants were grown hydrophonically as described in Materials and methods, and 1 week prior to inoculation, the plants were transferred to  (5mM) or

(5mM) or  (5mM) growth medium. Half leaves are shown and illustrate how the responses were more advanced in

(5mM) growth medium. Half leaves are shown and illustrate how the responses were more advanced in  -fed compared with

-fed compared with  -fed leaves. The results are representative of three independent experiments. Bar, 1cm. (B) Electrolyte leakage from 1cm diameter leaf discs sampled from areas of

-fed leaves. The results are representative of three independent experiments. Bar, 1cm. (B) Electrolyte leakage from 1cm diameter leaf discs sampled from areas of  -fed or

-fed or  -fed plants and inoculated with Psph, Pt, or 10mM MgCl2 (control). Electrolyte leakage from the 10mM MgCl2 infiltrated discs shows the baseline changes occurring from simple coring of leaf tissue. (C) Psph and Pt populations in

-fed plants and inoculated with Psph, Pt, or 10mM MgCl2 (control). Electrolyte leakage from the 10mM MgCl2 infiltrated discs shows the baseline changes occurring from simple coring of leaf tissue. (C) Psph and Pt populations in  -fed or

-fed or  -fed tobacco plants at 3 and 7 d with Psph [n=6; results shown as means ±standard deviation (SD)]. The initial populations of Psph and Pt as assessed immediately after infiltration (at 0 d) are also shown. Different letters denote groupings within which non-significant differences were observed but which were significantly different (P < 0.05) from all other groups.

-fed tobacco plants at 3 and 7 d with Psph [n=6; results shown as means ±standard deviation (SD)]. The initial populations of Psph and Pt as assessed immediately after infiltration (at 0 d) are also shown. Different letters denote groupings within which non-significant differences were observed but which were significantly different (P < 0.05) from all other groups.

It has been demonstrated that NO is involved in the cell death process during the HR (Delledonne et al., 1998), and  nutrition is known to influence NO levels (Planchet et al., 2005). Thus, we tested whether N nutrition had an impact on NO generation in the course of an HR elicited by Psph in tobacco. Initially, we used low-nutrient compost-grown tobacco plants, which were supplemented with either

nutrition is known to influence NO levels (Planchet et al., 2005). Thus, we tested whether N nutrition had an impact on NO generation in the course of an HR elicited by Psph in tobacco. Initially, we used low-nutrient compost-grown tobacco plants, which were supplemented with either  or

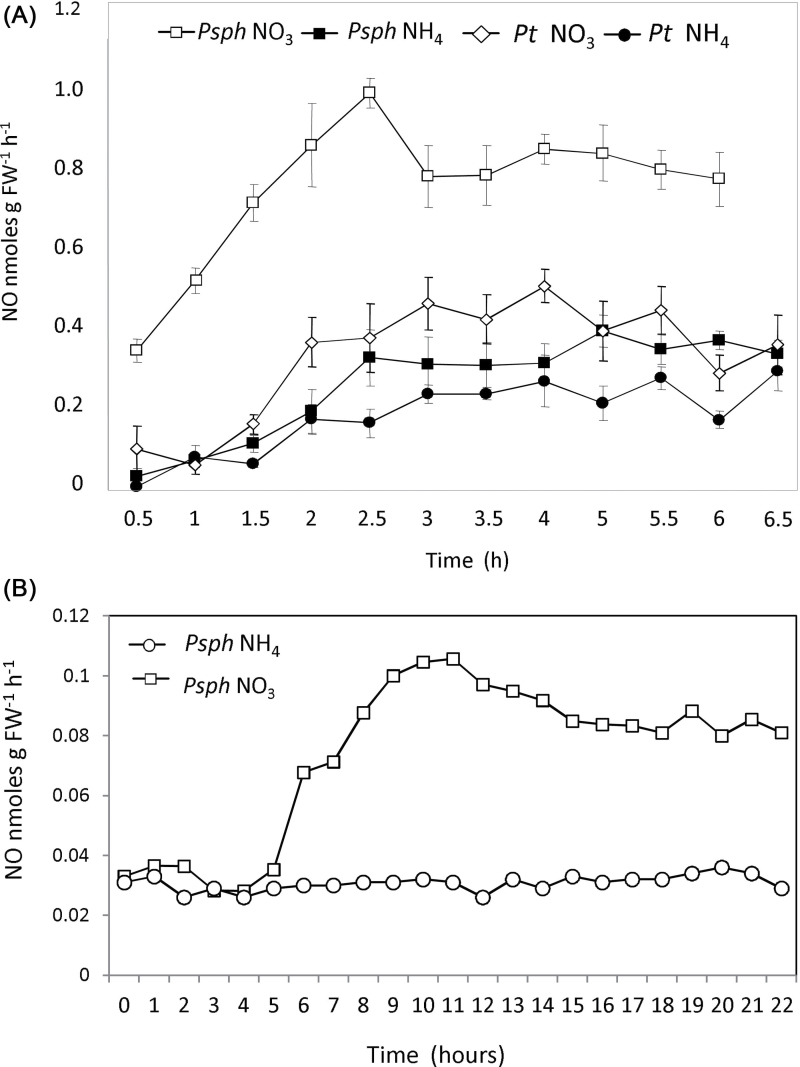

or  feed. NO production was measured from Psph-infected tobacco plants using a QCL (Mur et al., 2011). We observed that NO production was greater in

feed. NO production was measured from Psph-infected tobacco plants using a QCL (Mur et al., 2011). We observed that NO production was greater in  -fed and Psph-challenged plants compared with their

-fed and Psph-challenged plants compared with their  -fed equivalents (Fig. 2A). No NO production could be detected from uninfected plants (data not shown). We partially corroborated these observations by a second independent determination of NO levels in hydroponically grown plants using the gas-phase chemiluminescence method. This indicated greater NO emission from

-fed equivalents (Fig. 2A). No NO production could be detected from uninfected plants (data not shown). We partially corroborated these observations by a second independent determination of NO levels in hydroponically grown plants using the gas-phase chemiluminescence method. This indicated greater NO emission from  -grown and Psph challenged leaves compared with

-grown and Psph challenged leaves compared with  -fed plants (Fig. 2B). The difference in quantitative values for NO emissions measured by chemiluminescence compared with QCL is likely to reflect a difference between Psph-challenged, soil-grown and hydroponically grown tobacco plants, respectively.

-fed plants (Fig. 2B). The difference in quantitative values for NO emissions measured by chemiluminescence compared with QCL is likely to reflect a difference between Psph-challenged, soil-grown and hydroponically grown tobacco plants, respectively.

Fig. 2.

NO production in Psph- and Pt-inoculated  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco. (A) NO production in

-fed tobacco. (A) NO production in  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves challenged with avirulent Psph or virulent Pt measured using a QCL. No NO was detected in tobacco leaves infiltrated with 10mM MgCl2 (data not shown). In these experiments, the tobacco plants were grown in low-nutrient compost supplemented with

-fed tobacco leaves challenged with avirulent Psph or virulent Pt measured using a QCL. No NO was detected in tobacco leaves infiltrated with 10mM MgCl2 (data not shown). In these experiments, the tobacco plants were grown in low-nutrient compost supplemented with  or

or  . (B) The results were partially replicated in hydroponically grown plants challenged with Psph where NO production was measured using chemiluminescence detection. Data from the QCL represent the results of three separate experiments. Data from chemiluminescence represent results from two independent experiments.

. (B) The results were partially replicated in hydroponically grown plants challenged with Psph where NO production was measured using chemiluminescence detection. Data from the QCL represent the results of three separate experiments. Data from chemiluminescence represent results from two independent experiments.

Rates of NO production from Pt-inoculated  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco were also measured in compost-grown plants using QCL (Fig. 2A). NO production in

-fed tobacco were also measured in compost-grown plants using QCL (Fig. 2A). NO production in  -fed, Pt-inoculated plants did not differ significantly from those seen with

-fed, Pt-inoculated plants did not differ significantly from those seen with  -fed, Psph-challenged plants. Thus, it was not possible to correlate exactly in planta the bacterial populations in Pt-infected plants and Psph-challenged

-fed, Psph-challenged plants. Thus, it was not possible to correlate exactly in planta the bacterial populations in Pt-infected plants and Psph-challenged  -fed plants (Fig. 1C) with NO production. However, more NO was observed with Pt-infected

-fed plants (Fig. 1C) with NO production. However, more NO was observed with Pt-infected  -fed plants compared with

-fed plants compared with  -fed plants, which could explain the decreased bacterial populations seen in the latter (Fig. 1C).

-fed plants, which could explain the decreased bacterial populations seen in the latter (Fig. 1C).

To substantiate the link between NO production and cell death and a loss in bacterial resistance, we examined the interaction of Psph with the tobacco NR- mutant Nia30 line (supplied with  plus

plus  ) (Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). Using the QCL method, NO production was shown to be suppressed in Nia30 plants, and indeed more than in inoculated

) (Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). Using the QCL method, NO production was shown to be suppressed in Nia30 plants, and indeed more than in inoculated  -treated wild-type plants (Supplementary Fig. S1A). This correlated with a reduction in Psph-associated electrolyte leakage in Nia30 plants (Supplementary Fig. S1B) and increased bacterial numbers in Nia30 plants compared with

-treated wild-type plants (Supplementary Fig. S1A). This correlated with a reduction in Psph-associated electrolyte leakage in Nia30 plants (Supplementary Fig. S1B) and increased bacterial numbers in Nia30 plants compared with  -fed wild-type tobacco (Supplementary Fig. S1C). These data could indicate that NR is a major source of NO during Psph infection but that NH4 feeding could only partially mimic this situation. However, equally, the data could reflect that these plants were grown in low-nutrient compost rather than hydrophonic conditions so some NO3 could have been supplied to the plant.

-fed wild-type tobacco (Supplementary Fig. S1C). These data could indicate that NR is a major source of NO during Psph infection but that NH4 feeding could only partially mimic this situation. However, equally, the data could reflect that these plants were grown in low-nutrient compost rather than hydrophonic conditions so some NO3 could have been supplied to the plant.

Nitrate nutrition enhances PR1 gene expression and SA accumulation

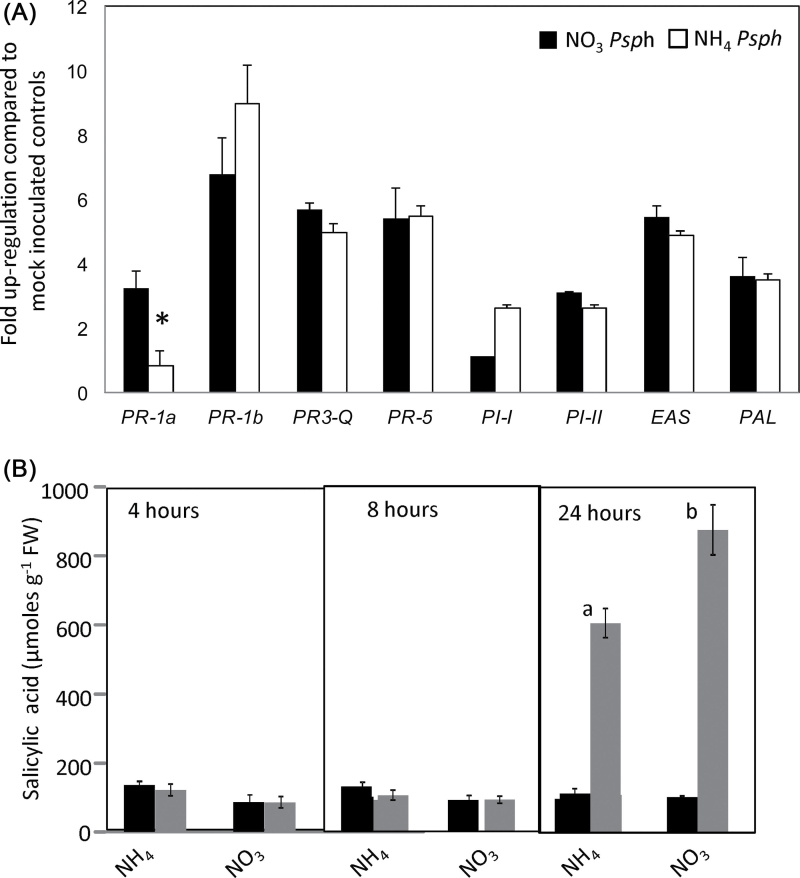

To assess other effects of N nutrition on the HR, we examined the expression of a range of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes that respond to different signals using qRT-PCR. Given our focus on the HR, all subsequent experimentation used the avirulent strain Psph. Transcript levels of individual genes were normalized to the transcripts level of EF-1a to allow relative quantification of gene expression. This indicated that only PR1a expression induction was significantly (P <0.05) reduced at 24h p.i. with  compared with

compared with  feeding (Fig. 3A). No clear differential expression between N treatments was observed at 4 and 8h p.i. (data not shown). The effects of

feeding (Fig. 3A). No clear differential expression between N treatments was observed at 4 and 8h p.i. (data not shown). The effects of  feeding appeared to dominate over those of

feeding appeared to dominate over those of  feeding, as co-application reversed the effects of the latter. PR1a is a biomarker for SA-mediated events, which are central to HR-mediated resistance (Delaney et al., 2004), so we quantified SA accumulation at 4, 8, and 24h p.i. with Psph (Fig. 3B). No elevation in total SA levels was observed compared with uninfected controls until 24h p.i. At this time point,

feeding, as co-application reversed the effects of the latter. PR1a is a biomarker for SA-mediated events, which are central to HR-mediated resistance (Delaney et al., 2004), so we quantified SA accumulation at 4, 8, and 24h p.i. with Psph (Fig. 3B). No elevation in total SA levels was observed compared with uninfected controls until 24h p.i. At this time point,  -fed plants accumulated more SA than

-fed plants accumulated more SA than  -fed tobacco levels.

-fed tobacco levels.

Fig. 3.

Defence gene expression and SA accumulation in Psph-infected  -fed or

-fed or  -fed tobacco leaves. (A) Fully expanded leaves of 4-week-old tobacco leaves were infiltrated with Psph and RNA was extracted from samples harvested at 24h p.i. qRT-PCR was carried out as described in Material and methods with primers designed to detect transcripts of the following defence genes: pathogenesis-related protein 1a (PR1a) acidic form; pathogenesis-related protein 1b (PR1b) basic form; pathogenesis-related protein 3 – Q (PR3-Q, chitinase); pathogenesis-related protein 5 (PR-5, thaumatin-like protein), proteinase inhibitor I (PI-I), proteinase inhibitor II (PI-II), 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (EAS), and phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) involved in phytoalexins biosynthesis. Transcripts were normalized to expression of the EF-1a housekeeping gene and results are expressed as fold increase or decrease compared with mock-inoculated controls. Results where significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed with different forms of N nutrition are indicated with an asterisk. (B) Free SA content of Psph-challenged (grey bars) and 10mM MgCl2-infiltrated (black bars) tobacco leaves at 4, 8, and 24h p.i. in plants fed with

-fed tobacco leaves. (A) Fully expanded leaves of 4-week-old tobacco leaves were infiltrated with Psph and RNA was extracted from samples harvested at 24h p.i. qRT-PCR was carried out as described in Material and methods with primers designed to detect transcripts of the following defence genes: pathogenesis-related protein 1a (PR1a) acidic form; pathogenesis-related protein 1b (PR1b) basic form; pathogenesis-related protein 3 – Q (PR3-Q, chitinase); pathogenesis-related protein 5 (PR-5, thaumatin-like protein), proteinase inhibitor I (PI-I), proteinase inhibitor II (PI-II), 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (EAS), and phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) involved in phytoalexins biosynthesis. Transcripts were normalized to expression of the EF-1a housekeeping gene and results are expressed as fold increase or decrease compared with mock-inoculated controls. Results where significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed with different forms of N nutrition are indicated with an asterisk. (B) Free SA content of Psph-challenged (grey bars) and 10mM MgCl2-infiltrated (black bars) tobacco leaves at 4, 8, and 24h p.i. in plants fed with  or

or  . Data are given as mean µmoles g–1 fresh weight (FW) (n=4 ±SD). The results of t-tests showing significant differences (P < 0.05) compared with mock-inoculated controls are indicated with ‘a’. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in

. Data are given as mean µmoles g–1 fresh weight (FW) (n=4 ±SD). The results of t-tests showing significant differences (P < 0.05) compared with mock-inoculated controls are indicated with ‘a’. Significant differences (P < 0.05) in  -fed compared with

-fed compared with  -fed plants are indicated with ‘b’.

-fed plants are indicated with ‘b’.

Increased amino acid and sugar content in  - fed tobacco

- fed tobacco

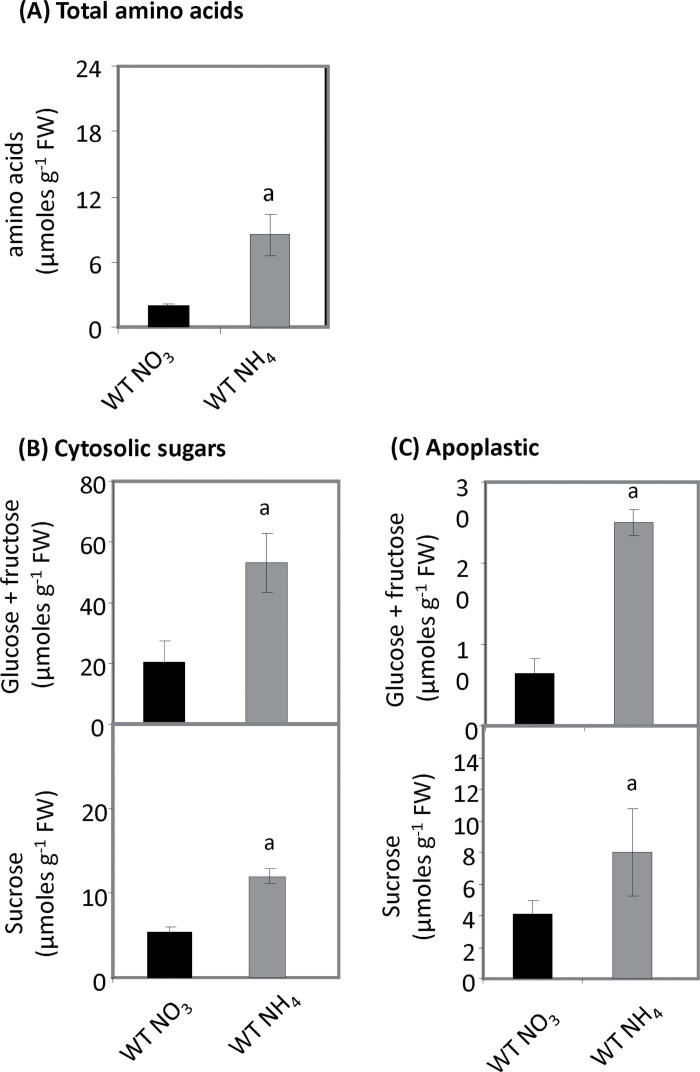

To assess whether or not the pre-inoculation nutrient status of the plant could be a factor in the differential responses, a series of generalized biochemical assays were undertaken. Assessment of total amino acids indicated that these were significantly (P < 0.001) elevated in  -fed compared with

-fed compared with  -fed tobacco plants (Fig. 4A). The response of sugar levels to

-fed tobacco plants (Fig. 4A). The response of sugar levels to  and

and  feeding in uninfected tobacco was also assessed both within the cell and in the apoplast. Both cytosolic and apoplastic sugar (sucrose, fructose, and glucose) contents were much higher in

feeding in uninfected tobacco was also assessed both within the cell and in the apoplast. Both cytosolic and apoplastic sugar (sucrose, fructose, and glucose) contents were much higher in  -grown plants (Fig. 4B, C). This suggested either that both sugar synthesis and sugar export are increased by

-grown plants (Fig. 4B, C). This suggested either that both sugar synthesis and sugar export are increased by  nutrition, or possibly that sugar consumption is suppressed. Due to the very minute sample volume obtained, it was not technically feasible to measure apoplastic amino acid levels.

nutrition, or possibly that sugar consumption is suppressed. Due to the very minute sample volume obtained, it was not technically feasible to measure apoplastic amino acid levels.

Fig. 4.

Amino acid and hexose sugar accumulation in  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves. (A) Amino acid levels (µmoles g–1 FW) in tobacco leaves of wild-type plants fed

-fed tobacco leaves. (A) Amino acid levels (µmoles g–1 FW) in tobacco leaves of wild-type plants fed  (black bars) or

(black bars) or  (grey bars). Data were obtained from eight leaves of eight independent plants. The plants were not inoculated with Psph. (B, C) Total hexose (glucose, fructose, and sucrose levels; µmoles g–1 FW) in the cytoplasm (B) or apoplasm (C) of tobacco leaves of wild-type plants fed

(grey bars). Data were obtained from eight leaves of eight independent plants. The plants were not inoculated with Psph. (B, C) Total hexose (glucose, fructose, and sucrose levels; µmoles g–1 FW) in the cytoplasm (B) or apoplasm (C) of tobacco leaves of wild-type plants fed  (black bars) or

(black bars) or  (grey bars). Data were obtained from eight leaves from eight different plants and are shown as means ±SD. The isolation of apoplastic solutions is described in Materials and methods. The plants were not inoculated with Psph. Results showing a significant (P < 0.05) increase over

(grey bars). Data were obtained from eight leaves from eight different plants and are shown as means ±SD. The isolation of apoplastic solutions is described in Materials and methods. The plants were not inoculated with Psph. Results showing a significant (P < 0.05) increase over  -fed plants are indicated with ‘a’.

-fed plants are indicated with ‘a’.

Metabolomic characterization of  and

and  effects following inoculation with Psph

effects following inoculation with Psph

Metabolic profiling approaches were followed to characterize further the effects of  and

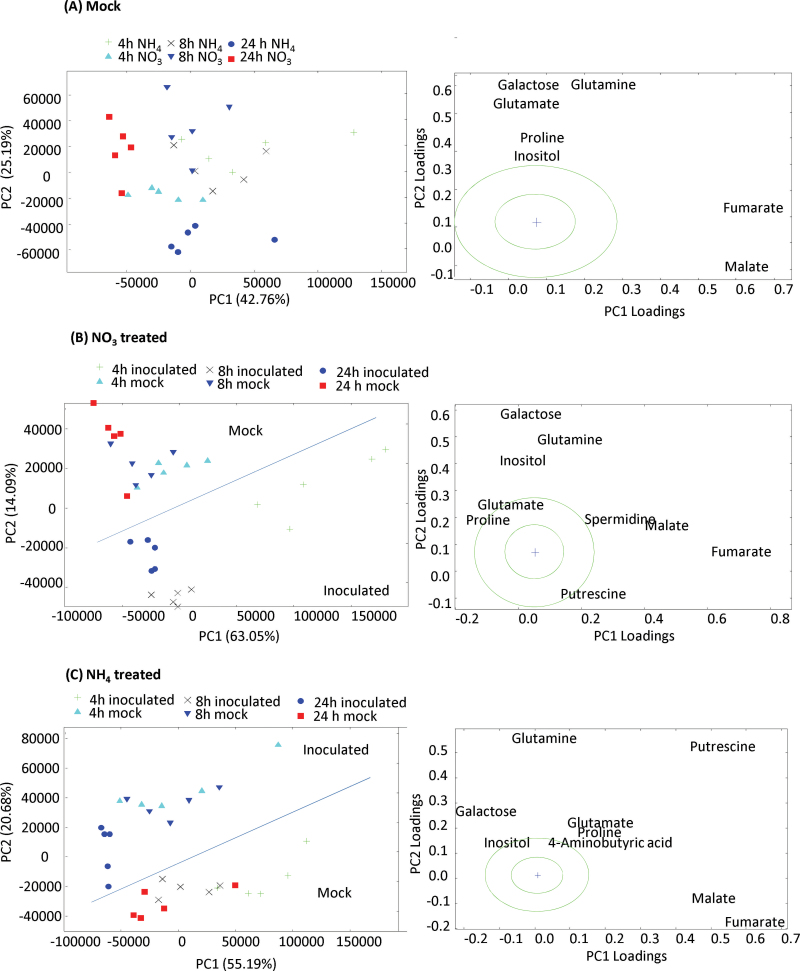

and  nutrition of tobacco following challenge with Psph. Extracts of Psph and mock-inoculated (10mM MgCl2) samples were analysed by GC-MS, as described previously (Lisec et al., 2006). The derived data were examined initially using non-supervised principal component analysis (PCA), and discrimination between

nutrition of tobacco following challenge with Psph. Extracts of Psph and mock-inoculated (10mM MgCl2) samples were analysed by GC-MS, as described previously (Lisec et al., 2006). The derived data were examined initially using non-supervised principal component analysis (PCA), and discrimination between  and

and  , mock and infected material was observed only at 24h p.i. (Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). To ease interpretation of these complicated data sets, they are also presented as a series of subanalyses separately examining GC-MS profiles from mock-inoculated samples (Fig. 5A),

, mock and infected material was observed only at 24h p.i. (Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). To ease interpretation of these complicated data sets, they are also presented as a series of subanalyses separately examining GC-MS profiles from mock-inoculated samples (Fig. 5A),  -treated (Fig. 5B), and

-treated (Fig. 5B), and  -treated (Fig. 5C) plants. In mock-inoculated samples,

-treated (Fig. 5C) plants. In mock-inoculated samples,  and

and  effects were relatively poorly differentiated except the 24h samples which partially separated along principal component 2 (PC2) (Fig. 5A). Based on the loading vectors for PC1 and PC2 (Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online), the most important metabolites contributing to this model appeared to be fumarate and malate, with subsidiary contributions by the amino acids glutamate, glutamine, and proline, as well as inositol and galactose (Fig. 5A). In Fig. 5B and C, PCA discriminated between Psph and mock-inoculated samples, allowing the loading vectors linked to metabolites making major contributions to the observed biological effects to be identified (Supplementary Table S1). Examining the effects of Psph challenge of

effects were relatively poorly differentiated except the 24h samples which partially separated along principal component 2 (PC2) (Fig. 5A). Based on the loading vectors for PC1 and PC2 (Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online), the most important metabolites contributing to this model appeared to be fumarate and malate, with subsidiary contributions by the amino acids glutamate, glutamine, and proline, as well as inositol and galactose (Fig. 5A). In Fig. 5B and C, PCA discriminated between Psph and mock-inoculated samples, allowing the loading vectors linked to metabolites making major contributions to the observed biological effects to be identified (Supplementary Table S1). Examining the effects of Psph challenge of  -fed tobacco suggested that, besides those metabolites indicated in Fig. 5A, changes in spermidine and putrescine were important sources of variation (Fig. 5B). With

-fed tobacco suggested that, besides those metabolites indicated in Fig. 5A, changes in spermidine and putrescine were important sources of variation (Fig. 5B). With  feeding, GABA and putrescine were additional sources of variation over baseline changes, as suggested from an analysis of the mock-inoculated controls (Fig. 3C). Based on the detected metabolites, these observations suggested that two pathways were prominent sources of differentiation between the

feeding, GABA and putrescine were additional sources of variation over baseline changes, as suggested from an analysis of the mock-inoculated controls (Fig. 3C). Based on the detected metabolites, these observations suggested that two pathways were prominent sources of differentiation between the  and

and  effects on the Psph-induced HR: respectively, the polyamine and GABA/TCA cycle metabolites.

effects on the Psph-induced HR: respectively, the polyamine and GABA/TCA cycle metabolites.

Fig. 5.

Identifying metabolite changes occurring in  or

or  in tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph. Results are shown for PCA of 150 metabolites detected by GC-MS in

in tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph. Results are shown for PCA of 150 metabolites detected by GC-MS in  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves following infiltration with 10mM MgCl2 (mock inoculated) (A), and

-fed tobacco leaves following infiltration with 10mM MgCl2 (mock inoculated) (A), and  -treated and Psph challenged plants (B) or

-treated and Psph challenged plants (B) or  -treated and Psph challenged plants (C). In each case, samples were analysed at 4, 8, and 24h following inoculation. In (B) and (C), clear separation between mock- and Psph-inoculated plants is delineated and labelled. In (A–C), the loading vectors (listed in Supplementary Table S1) used for the corresponding PC1 and PC2 are plotted. The ‘+’ marks the zero point where loading vectors associated with metabolites make no contribution to the plot shown in (B), whilst the circles correspond to 1 and 2 SD from this zero point. Thus, the metabolites that are major sources of variation are shown.

-treated and Psph challenged plants (C). In each case, samples were analysed at 4, 8, and 24h following inoculation. In (B) and (C), clear separation between mock- and Psph-inoculated plants is delineated and labelled. In (A–C), the loading vectors (listed in Supplementary Table S1) used for the corresponding PC1 and PC2 are plotted. The ‘+’ marks the zero point where loading vectors associated with metabolites make no contribution to the plot shown in (B), whilst the circles correspond to 1 and 2 SD from this zero point. Thus, the metabolites that are major sources of variation are shown.

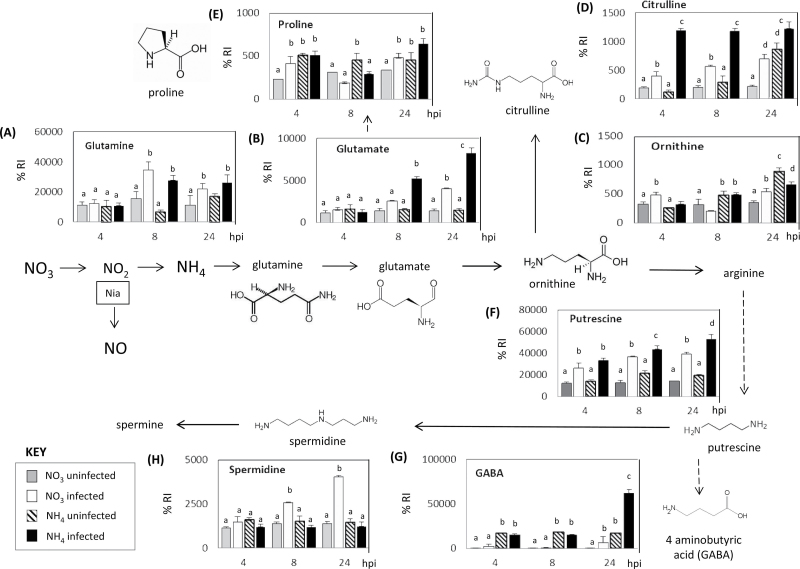

The metabolites that form the glutamine–polyamine pathways were examined in isolation (Fig. 6). Challenge with Psph increased the concentrations of glutamine (Fig. 6A) and glutamate (Fig. 6B) but not ornithine (Fig. 6), whether plants were fed  or

or  . Interestingly, citrulline, which is produced from ornithine, exhibited a feeding-specific effect (Fig. 6D). However, proline, which is produced from glutamate, exhibited no infection or nutrition-specific trend (Fig. 6E). Thus, although proline was prominent in the loading vectors that discriminated between the treatment groups (Fig. 5), it could not be readily related to a biological response. By contrast, an alternative pathway leading to putrescine (Fig. 6F) increased with infection following both

. Interestingly, citrulline, which is produced from ornithine, exhibited a feeding-specific effect (Fig. 6D). However, proline, which is produced from glutamate, exhibited no infection or nutrition-specific trend (Fig. 6E). Thus, although proline was prominent in the loading vectors that discriminated between the treatment groups (Fig. 5), it could not be readily related to a biological response. By contrast, an alternative pathway leading to putrescine (Fig. 6F) increased with infection following both  and

and  feeding. However, different N feeding appeared to encourage a differential processing of putrescine and linked metabolites. At 24h p.i., a pathway leading to GABA formation appeared to be particularly prominent in

feeding. However, different N feeding appeared to encourage a differential processing of putrescine and linked metabolites. At 24h p.i., a pathway leading to GABA formation appeared to be particularly prominent in  -fed plants following infection (Fig. 6G), whilst an alternative pathway leading to spermidine accumulation appear to predominate with infected and

-fed plants following infection (Fig. 6G), whilst an alternative pathway leading to spermidine accumulation appear to predominate with infected and  -fed plants (Fig. 6H).

-fed plants (Fig. 6H).

Fig. 6.

N-assimilatory proline and putrescine pathways in the responses of tobacco to Psph. Results from individual metabolites are displayed around the assimilatory pathway of  and

and  in plants linking through to proline, polyamine, and GABA. Note the position of NR encoded by the nia gene and its role in N assimilation and NO generation. The pathways were adapted from the Plant Metabolic network (http://www.plantcyc.org/). Broken arrows indicate multiple steps. Metabolites were detected by GC-MS in

in plants linking through to proline, polyamine, and GABA. Note the position of NR encoded by the nia gene and its role in N assimilation and NO generation. The pathways were adapted from the Plant Metabolic network (http://www.plantcyc.org/). Broken arrows indicate multiple steps. Metabolites were detected by GC-MS in  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or mock inoculation with 10mM MgCl2. Results are shown for glutamine (A), glutamate (B), ornithine (C), citrulline (D), proline (E), putrescine (F), GABA (G), and spermidine (H). Data are displayed as the percentage of relative intensity (% RI). Different letters denote groupings within which non-significant differences were observed but which were significantly different (P < 0.05) from all other groups.

-fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or mock inoculation with 10mM MgCl2. Results are shown for glutamine (A), glutamate (B), ornithine (C), citrulline (D), proline (E), putrescine (F), GABA (G), and spermidine (H). Data are displayed as the percentage of relative intensity (% RI). Different letters denote groupings within which non-significant differences were observed but which were significantly different (P < 0.05) from all other groups.

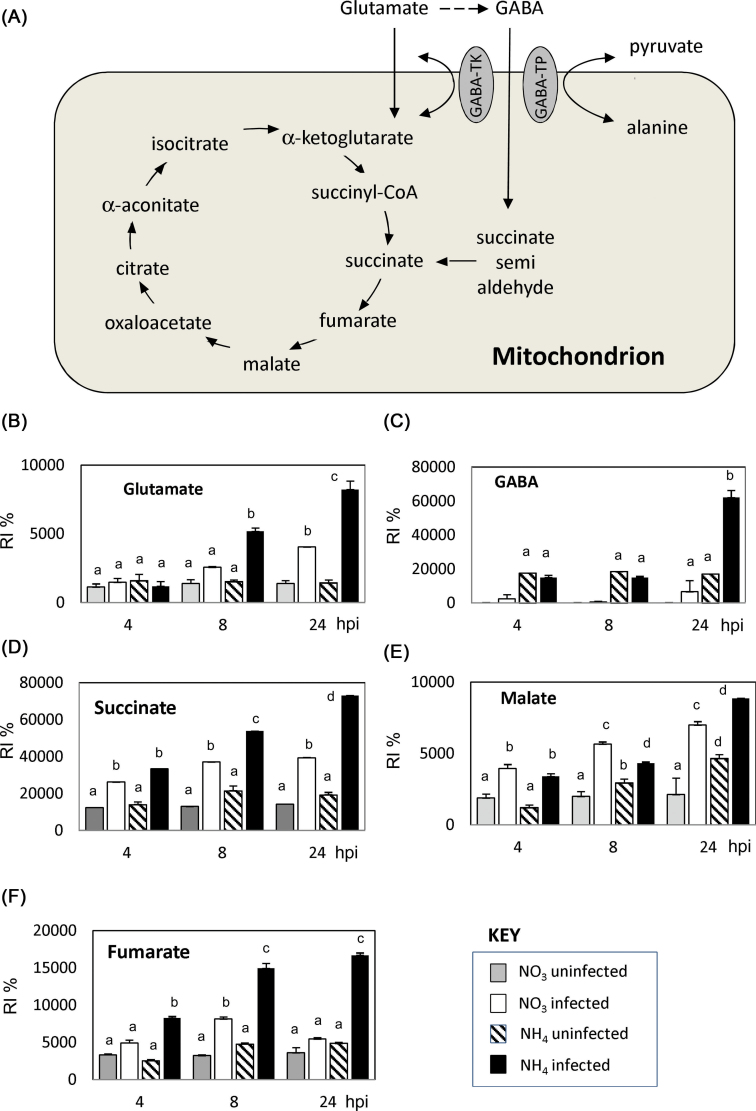

The accumulation of GABA led us to examine the accumulation of metabolites that could be linked to the GABA shunt/TCA cycle (Fig. 7A). Succinate, malate, and fumarate (Fig. 7D–F) showed increased accumulation on infection with either  -fed or

-fed or  -fed plants, but at 24h p.i., all also exhibited significantly greater accumulation in

-fed plants, but at 24h p.i., all also exhibited significantly greater accumulation in  plants. These observations suggested increased TCA cycle activity in line with the energetic demands of plant defence. In addition, given the increased accumulation of glutamate and GABA (Fig. 7B, C), it is likely that the GABA shunt is a more marked feature of

plants. These observations suggested increased TCA cycle activity in line with the energetic demands of plant defence. In addition, given the increased accumulation of glutamate and GABA (Fig. 7B, C), it is likely that the GABA shunt is a more marked feature of  -fed plants.

-fed plants.

Fig. 7.

Changes in the TCA cycle/GABA shunt in  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph. (A) Depiction of the TCA cycle linked to the GABA shunt. Metabolites were detected by GC-MS in

-fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph. (A) Depiction of the TCA cycle linked to the GABA shunt. Metabolites were detected by GC-MS in  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or mock inoculation with 10mM MgCl2. Results are shown for glutamate (B), GABA (C), succinate (D), malate (E), and fumarate (F). Data are displayed as the percentage of relative intensity (% RI). Different letters denote groupings within which non-significant differences were observed but which were significantly different (P < 0.05) from all other groups.

-fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or mock inoculation with 10mM MgCl2. Results are shown for glutamate (B), GABA (C), succinate (D), malate (E), and fumarate (F). Data are displayed as the percentage of relative intensity (% RI). Different letters denote groupings within which non-significant differences were observed but which were significantly different (P < 0.05) from all other groups.

Galactose was prominent in the loading vectors that discriminated between the experimental treatments (Fig. 5). The data for this metabolite were plotted to indicate significantly greater accumulation in Psph-challenged  -fed tobacco compared with similarly inoculated

-fed tobacco compared with similarly inoculated  -fed tobacco (Supplementary Fig. 3 at JXB online). Galactose accumulation in plants could occur as part the biosynthesis of ascorbate (Laing et al., 2007) or the construction of cell-wall polymers (Seifert et al., 2002). In Supplementary Fig. S3, the data are displayed in terms of the role of galactose in contributing to glycolysis (Plaxton, 1996), as this could be part of the biogenetic changes occurring following Psph challenge. However, the accumulation patterns of other glycolysis-associated metabolites did not correlate with the treatment classes. Inositol also was also highlighted in the list of metabolites that discriminated between the experimental classes (Fig. 5). However, when considering the inositol data in isolation, they did not indicate a clear, biologically relevant trend (Supplementary Fig. S4A at JXB online). This was also the case with all other amino acids measured by GC-MS (Supplementary Fig. S4).

-fed tobacco (Supplementary Fig. 3 at JXB online). Galactose accumulation in plants could occur as part the biosynthesis of ascorbate (Laing et al., 2007) or the construction of cell-wall polymers (Seifert et al., 2002). In Supplementary Fig. S3, the data are displayed in terms of the role of galactose in contributing to glycolysis (Plaxton, 1996), as this could be part of the biogenetic changes occurring following Psph challenge. However, the accumulation patterns of other glycolysis-associated metabolites did not correlate with the treatment classes. Inositol also was also highlighted in the list of metabolites that discriminated between the experimental classes (Fig. 5). However, when considering the inositol data in isolation, they did not indicate a clear, biologically relevant trend (Supplementary Fig. S4A at JXB online). This was also the case with all other amino acids measured by GC-MS (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Discussion

A major driver for increased agricultural production in the 20th century has been the extensive use of N fertilizers (Tilman et al., 2002). The increased availability of N is a direct consequence of the Haber–Bosch process where nitrogen gas (N2) is fixed to form NH3 as the end product. NH3 is used to derive N fertilizers such as anhydrous ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) and urea [CO(NH2)2]. Within the soil ecosystem, the applied NH4 is readily oxidized by microbial nitrification processes to form NO3. NO3 is the main source of inorganic N for plants, but mainly due to the negative charge of clay, is easily leached out of soil to become to major water pollutant and a source of eutrophication (Peng and Zhu, 2006). NO3 removal is an expensive process so alternative strategies, including the use of nitrification inhibitors, have been followed (de Klein et al., 1996). Such measures illustrate how N fertilizer will continue to feature in modern agriculture, so the wide-ranging s of NO3 on plant physiology need to be fully assessed. The effects of different N forms have been investigated at the level of, for example, the response to elevated CO2 (Geiger et al., 1999) and indeed on disease development (Huber and Watson, 1974), but there has been much less work done with respect to the HR. New diseases are constantly emerging and although R gene-mediated, HR-linked defences are often ephemeral (Stuthman, 2002), they continue to be important components of crop breeding programmes. It is therefore vital to identify and characterize agricultural and horticultural practices that could compromise or increase these R gene-linked defence mechanisms. Thus, here we sought to characterize the effects of  and

and  feeding of tobacco plants on a HR elicited by Psph.

feeding of tobacco plants on a HR elicited by Psph.

NO- and SA-mediated defence is augmented by  nutrition

nutrition

To assess the effects of variable N-form nutrition, we made use of hydroponically fed tobacco plants (Kaiser et al., 2004, 2005). In our experimental approach, we did not observe any effects of NH4 feeding on tobacco growth or biomass, as observed by Walch-Liu et al. (2000), which may reflect our use of cv. Gatersleben compared with cv. Samsun. The lack of any NH4 toxicity was also suggested from the lack of significant treatment-specific effects on EF1-a expression in our qRT-PCR analysis (data not shown).

Our initial assessments suggested that  nutrition influenced cell death but that

nutrition influenced cell death but that  feeding had a greater impact on mechanisms that suppressed bacterial growth during the HR (Fig. 1). When considering how

feeding had a greater impact on mechanisms that suppressed bacterial growth during the HR (Fig. 1). When considering how  could be contributing to cell death, one of the most likely routes is via NO production (Romero-Puertas et al., 2004). Many sources of NO generation have been proposed, including the oxidation of L-arginine or polyamines by as yet poorly characterized enzymatic sources. However, one of the most well established is the NAD(P)H-linked reduction of

could be contributing to cell death, one of the most likely routes is via NO production (Romero-Puertas et al., 2004). Many sources of NO generation have been proposed, including the oxidation of L-arginine or polyamines by as yet poorly characterized enzymatic sources. However, one of the most well established is the NAD(P)H-linked reduction of  by cytosolic NR (Rockel et al., 2002). N assimilation by

by cytosolic NR (Rockel et al., 2002). N assimilation by  rather than

rather than  would therefore effectively short-circuit NO production if NR was a major source of NO during the Psph-elicited HR in tobacco. Our assessments of NO production from Nia30 plants demonstrated that this was the major source of NO during the Psph-elicited HR of tobacco (Supplementary Fig. S1). Given this, it was telling that significantly (P < 0.001) more NO was generated in

would therefore effectively short-circuit NO production if NR was a major source of NO during the Psph-elicited HR in tobacco. Our assessments of NO production from Nia30 plants demonstrated that this was the major source of NO during the Psph-elicited HR of tobacco (Supplementary Fig. S1). Given this, it was telling that significantly (P < 0.001) more NO was generated in  -fed as opposed to

-fed as opposed to  -fed tobacco (Fig. 2A). This important observation indicated that some of the effects of reduced NO generation could be reproduced through simple nutritional effects and thus is of greater relevance to agricultural practice. Interestingly, citrulline accumulation was prominent in Psph-infected tobacco plants (Fig. 6D, which might be expected if an NO synthase (NOS)-like mechanism was contributing to NO production (NOS oxidizes arginine to produce NO and citrulline). However, this was considered to be unlikely, as citrulline accumulation was greatest in

-fed tobacco (Fig. 2A). This important observation indicated that some of the effects of reduced NO generation could be reproduced through simple nutritional effects and thus is of greater relevance to agricultural practice. Interestingly, citrulline accumulation was prominent in Psph-infected tobacco plants (Fig. 6D, which might be expected if an NO synthase (NOS)-like mechanism was contributing to NO production (NOS oxidizes arginine to produce NO and citrulline). However, this was considered to be unlikely, as citrulline accumulation was greatest in  -fed plants where NO production was reduced compared with

-fed plants where NO production was reduced compared with  -fed tobacco (Fig. 2).

-fed tobacco (Fig. 2).

NO also contributes to the initiation of SA biosynthesis (Durner and Klessig, 1999), and SA potentiates the oxidative burst to augment cell death during the HR (Mur et al., 2000). Thus, the reduction in SA accumulation at 24h p.i. in  -fed tobacco (Fig. 3B) is most likely linked to lower NO production (Fig. 2). It was also notable that, in our assessments of defence genes, expression in

-fed tobacco (Fig. 3B) is most likely linked to lower NO production (Fig. 2). It was also notable that, in our assessments of defence genes, expression in  effects seemed to be confined to the SA-regulated PR1 gene. However, this need not indicate that reduced PR1a expression itself must be the cause of reduced resistance, as, although it is a well-established marker for plant defence (Hooft van Huijsduijnen et al., 1985), its actual action is poorly defined (Alexander et al., 1993; van Loon et al., 2006). Other defence genes such as proteinase inhibitors were apparently not affected by N feeding. Fritz et al. (2006b) noted that expression of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), which plays a key role in phenylpropanoid production, was influenced by NO3. Given the central role of PAL in plant defence (Pallas et al., 1996) regulating the production of, for example, defence lignin, if

effects seemed to be confined to the SA-regulated PR1 gene. However, this need not indicate that reduced PR1a expression itself must be the cause of reduced resistance, as, although it is a well-established marker for plant defence (Hooft van Huijsduijnen et al., 1985), its actual action is poorly defined (Alexander et al., 1993; van Loon et al., 2006). Other defence genes such as proteinase inhibitors were apparently not affected by N feeding. Fritz et al. (2006b) noted that expression of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), which plays a key role in phenylpropanoid production, was influenced by NO3. Given the central role of PAL in plant defence (Pallas et al., 1996) regulating the production of, for example, defence lignin, if  affects PAL expression, this could be a major source of compromised resistance. However, we did not observe any significant effect on PAL expression (Fig. 3A), suggesting that modulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis was not a source of loss of resistance following

affects PAL expression, this could be a major source of compromised resistance. However, we did not observe any significant effect on PAL expression (Fig. 3A), suggesting that modulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis was not a source of loss of resistance following  treatment.

treatment.

nutrition shifts the host responses to favour pathogenesis

nutrition shifts the host responses to favour pathogenesis

In order to characterize further the N nutritional effects on defence, we chose to concentrate on metabolomic approaches with a focus on C:N primary metabolism. It could be predicted that the most obvious effect of differential N treatment would be wide-ranging changes in the concentrations of several amino acids. In fact, other than for a few examples (discussed below), most changes proved to be difficult to link with any biological effect (Supplementary Fig. S4). Within the context of  - mediated resistance, metabolite profiling suggested the importance of polyamine production. Independent evidence also supports an important role for polyamines in defence (Walters, 2003). For example, elevation of spermine accumulation in transgenic lines increased resistance in tobacco against Pt and also the hemibiotrophic oomycete Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotiana (Moschou et al., 2009), whilst increases in spermine in Arabidopsis boosted defence against Pseudomonas viridiflava (Gonzalez et al., 2011). Mechanistically, polyamines could increase resistance by acting as substrates for a NO-generating complex (Yamasaki and Cohen, 2006), but are known to contribute to reactive oxygen species production and cell death (Cona et al., 2006), as well as cell-wall reinforcement via conjugation to hydroxycinnamic acid (Walters, 2003). Whatever mechanisms are employed by polyamine, it is apparent that

- mediated resistance, metabolite profiling suggested the importance of polyamine production. Independent evidence also supports an important role for polyamines in defence (Walters, 2003). For example, elevation of spermine accumulation in transgenic lines increased resistance in tobacco against Pt and also the hemibiotrophic oomycete Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotiana (Moschou et al., 2009), whilst increases in spermine in Arabidopsis boosted defence against Pseudomonas viridiflava (Gonzalez et al., 2011). Mechanistically, polyamines could increase resistance by acting as substrates for a NO-generating complex (Yamasaki and Cohen, 2006), but are known to contribute to reactive oxygen species production and cell death (Cona et al., 2006), as well as cell-wall reinforcement via conjugation to hydroxycinnamic acid (Walters, 2003). Whatever mechanisms are employed by polyamine, it is apparent that  feeding alone is insufficient to trigger the shift to polyamine synthesis but requires additional elicitation by Psph.

feeding alone is insufficient to trigger the shift to polyamine synthesis but requires additional elicitation by Psph.

Coupled to  effects, we examined how

effects, we examined how  could compromise resistance and/or promote disease. Nia30 mutants lacking NR have much lower levels of amino acids (Fritz et al., 2006b

), so we could have predicted that

could compromise resistance and/or promote disease. Nia30 mutants lacking NR have much lower levels of amino acids (Fritz et al., 2006b

), so we could have predicted that  feeding would reduce amino acid levels. However, instead we observed that there were increases in total amino acid levels with

feeding would reduce amino acid levels. However, instead we observed that there were increases in total amino acid levels with  feeding (Fig. 4). An alternative hypothesis could be related to the effects on carbon metabolism, as this is intimately related to N effects. Thus, for example, a suppression of carbon fixation by, for example, the generation of RbcS antisense plants reduces both carbohydrate concentrations and

feeding (Fig. 4). An alternative hypothesis could be related to the effects on carbon metabolism, as this is intimately related to N effects. Thus, for example, a suppression of carbon fixation by, for example, the generation of RbcS antisense plants reduces both carbohydrate concentrations and  assimilation (Matt et al., 2002). Indeed, sugar depletion can suppress NIA expression and NR activity (Matt et al., 2002), whilst the application of sugar can reverse this effect (Koch, 1996), as well as inducing nitrate transporter genes (Lejay et al., 1999). Correspondingly, glucose and sucrose concentrations are reduced in

assimilation (Matt et al., 2002). Indeed, sugar depletion can suppress NIA expression and NR activity (Matt et al., 2002), whilst the application of sugar can reverse this effect (Koch, 1996), as well as inducing nitrate transporter genes (Lejay et al., 1999). Correspondingly, glucose and sucrose concentrations are reduced in  - depleted tobacco (Fritz et al., 2006a

). Given this, it is significant that, in

- depleted tobacco (Fritz et al., 2006a

). Given this, it is significant that, in  -fed plants, there were increases cellular and apoplastic hexose levels compared with

-fed plants, there were increases cellular and apoplastic hexose levels compared with  (Fig. 4). This would be a direct advantage to apoplastically located bacterial pathogens (Rico and Preston, 2008). Sucrose was also noted to increase in Arabidopsis when challenged with P. syringae pv. tomato (Ward et al., 2010), further suggesting that this is an important feature of disease development.

(Fig. 4). This would be a direct advantage to apoplastically located bacterial pathogens (Rico and Preston, 2008). Sucrose was also noted to increase in Arabidopsis when challenged with P. syringae pv. tomato (Ward et al., 2010), further suggesting that this is an important feature of disease development.

Given these observations, it is worth highlighting the similarity of some events during disease development and N mobilization during senescence (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2006, 2007). Senescence is characterized by the mobilization of nitrogen, carbon, and other nutrients out of the leaf to other parts of the plant or to contribute to such reproductively important processes as grain filling (Buchanan-Wollaston, 1997). Prominent senescence-linked changes include the export of hexose sugars from the cell. Similarly, the mobilization of starch and sucrose export is a feature of many disease situations (Scharte et al., 2005; Swarbrick et al., 2006; Essmann et al., 2008). Indeed, a causal link between sugar export and disease symptom development has been demonstrated (Kocal et al., 2008). Therefore, it is possible that  feeding encourages disease development by promoting a leaf senescence programme. This effect may not be due directly to

feeding encourages disease development by promoting a leaf senescence programme. This effect may not be due directly to  but to a reduction in NO production during a HR. NO has been suggested to act as an anti-senescence signal (Mishina et al., 2007), so a lowering of the NO concentration would actively promote senescence.

but to a reduction in NO production during a HR. NO has been suggested to act as an anti-senescence signal (Mishina et al., 2007), so a lowering of the NO concentration would actively promote senescence.

Our GC-MS analyses revealed a prominent accumulation of GABA following  feeding, representing a diversion of putrescine metabolism away from polyamine biosynthesis. Increases in GABA are a well-established feature of plant senescence (Masclaux et al., 2000; Diaz et al., 2005) and this could act as an enhancer of ethylene effects, represent a transient N storage compound or activation of the GABA shunt (Diaz et al., 2005). Within the context of challenge of tobacco with Psph, GABA could serve directly as a nutrient source for pathogens (Kinnersley and Turano, 2000; Solomon and Oliver, 2001) but when coupled to increases in malate, fumarate, and especially succinate, it suggested that flux through the GABA shunt was enhanced (Fig. 7). The GABA shunt provides a metabolic route through which N input can feed directly into the TCA cycle and thus bioenergetically contribute to the mobilization of nutrients. As with polyamine metabolism, the shift to GABA was not prominent in solely

feeding, representing a diversion of putrescine metabolism away from polyamine biosynthesis. Increases in GABA are a well-established feature of plant senescence (Masclaux et al., 2000; Diaz et al., 2005) and this could act as an enhancer of ethylene effects, represent a transient N storage compound or activation of the GABA shunt (Diaz et al., 2005). Within the context of challenge of tobacco with Psph, GABA could serve directly as a nutrient source for pathogens (Kinnersley and Turano, 2000; Solomon and Oliver, 2001) but when coupled to increases in malate, fumarate, and especially succinate, it suggested that flux through the GABA shunt was enhanced (Fig. 7). The GABA shunt provides a metabolic route through which N input can feed directly into the TCA cycle and thus bioenergetically contribute to the mobilization of nutrients. As with polyamine metabolism, the shift to GABA was not prominent in solely  -fed plants but required challenge with Psph, which would suggest that a pathogen-elicited pathway was being altered. In the most comprehensive metabolomic investigation of plant disease, Ward et al. (2010) noted only marginal increases in GABA in Arabidopsis following inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. The lack of concordance between the two datasets could reflect differences between tobacco and Arabidopsis, or that, in our case, the

-fed plants but required challenge with Psph, which would suggest that a pathogen-elicited pathway was being altered. In the most comprehensive metabolomic investigation of plant disease, Ward et al. (2010) noted only marginal increases in GABA in Arabidopsis following inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. The lack of concordance between the two datasets could reflect differences between tobacco and Arabidopsis, or that, in our case, the  -modified HR only partially reflects a true disease scenario. Clearly, further work is required to characterize how changes in metabolite flux through putrescine with

-modified HR only partially reflects a true disease scenario. Clearly, further work is required to characterize how changes in metabolite flux through putrescine with  or

or  feeding are regulated, and these are currently underway in our laboratories.

feeding are regulated, and these are currently underway in our laboratories.

Taken together, our observations demonstrate that N nutrition can either enhance or compromise R gene-mediated resistance. We have provided some mechanistic insight into these mechanisms by suggesting that  is important for resistance, mostly via NO and SA generation, as well as polyamine biosynthesis. In contrast, feeding

is important for resistance, mostly via NO and SA generation, as well as polyamine biosynthesis. In contrast, feeding  can compromise resistance not only through reduced NO generation but also by encouraging metabolic reprogramming of HR defence towards sugar and GABA production. Crucially, if these data are extrapolated into an agricultural context, it seems likely that the form of N applied, as well as the levels, can influence susceptibility to pathogens in crop species.

can compromise resistance not only through reduced NO generation but also by encouraging metabolic reprogramming of HR defence towards sugar and GABA production. Crucially, if these data are extrapolated into an agricultural context, it seems likely that the form of N applied, as well as the levels, can influence susceptibility to pathogens in crop species.

Supplementary data

Supplementary are available at JXB online.

Supplementary Table S1. Loading vectors for PCA models shown in Fig. 5A–C, which analyse metabolite changes occurring in  -fed or

-fed or  -fed tobacco leaves following mock infection and inoculation with Psph.

-fed tobacco leaves following mock infection and inoculation with Psph.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Nitrate reductase-dependent effects on the HR elicited by Psph in tobacco.

Supplementary Fig. S2. Multivariate analyses of metabolite profiles of  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph.

-fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph.

Supplementary Fig. S3. Galactose and glycolytic metabolite accumulation in  -fed and

-fed and  -fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or 10mM MgCl2.

-fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or 10mM MgCl2.

Supplementary Fig. S4. Amino acid accumulation in  - and

- and  -fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or 10mM MgCl2.

-fed tobacco leaves following inoculation with Psph or 10mM MgCl2.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lothar Willmitzer for critical reading of the manuscript and also for providing the GC-MS facilities, Eva Wirth for amino acid analysis, and Maria Lesch for technical assistance. We also thank the anonymous referees for making some important suggestions. This work was supported by DFG (SFB 567) to W.M.K. and K.J.G. and the Max Planck Society (K.J.G., Y.B., and S.S.).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- GABA

4-aminobutyric acid

- GC-MS

gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy

- GS

glutamine synthetase

- HR

hypersensitivity response

- N

nitrogen

- NO

nitric oxide

- NR

nitrate reductase

- PPDF

photosynthetic photon flux density

- Psph

Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola

- Pt

P. syringae pv. tabaci

- QCL

quantum cascade laser

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time RT-PCR

- SA

salicylic acid

- TCA