Abstract

Use of antibodies is a cornerstone of biological studies and it is important to identify the recognized protein with certainty. Generally an antibody is considered specific if it labels a single band of the expected size in the tissue of interest, or has a strong affinity for the antigen produced in a heterologous system. The identity of the antibody target protein is rarely confirmed by purification and sequencing, however in many cases this may be necessary. In this study we sought to characterize the myoplasm, a mitochondria-rich domain present in eggs and segregated into tadpole muscle cells of ascidians (urochordates). The targeted proteins of two antibodies that label the myoplasm were purified using both classic immunoaffinity methods and a novel protein purification scheme based on sequential ion exchange chromatography followed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Surprisingly, mass spectrometry sequencing revealed that in both cases the proteins recognized are unrelated to the original antigens. NN18, a monoclonal antibody which was raised against porcine spinal cord and recognizes the NF-M neurofilament subunit in vertebrates, in fact labels mitochondrial ATP synthase in the ascidian embryo. PMF-C13, an antibody we raised to and purified against PmMRF, which is the MyoD homolog of the ascidian Phallusia mammillata, in fact recognizes mitochondrial HSP60. High resolution immunolabeling on whole embryos and isolated cortices demonstrates localization to the inner mitochondrial membrane for both ATP synthase and HSP60. We discuss the general implications of our results for antibody specificity and the verification methods which can be used to determine unequivocally an antibody's target.

Introduction

Antibody tools are of fundamental importance for learning about proteins and cellular mechanisms, and a number of recent reviews are calling for rigorous standards of antibody validation [1]–[5]. Concern about antibody specificity is increasing with the use of fluorescent protein fusions to determine protein distribution and the need to resolve discrepancies between live and fixed samples [6]. Frequently in the literature the specificity of an antibody is considered verified if it labels a single band of the expected size, or shows an affinity for the antigen produced in a heterologous system such as bacteria. Here we challenge these assumptions by directly purifying two antibody targets from the ascidian egg using both immunoaffinity methods and a novel strategy to enrich for nonabundant proteins.

We sought to characterize the polarized mitochondria-rich domain of ascidian eggs known as the myoplasm. Ascidians are tunicates, the sister group to vertebrates [7], and their embryos develop rapidly into tadpole larvae exhibiting the typical chordate body plan [8], [9]. Over a century ago observations of the inheritance of myoplasm led biologists to propose the theory of “mosaic” or autonomous development whereby localized domains containing organelles and molecular determinants are partitioned into distinct cell lineages [10], [11]. The myoplasm is positioned as a peripheral basket in the ascidian egg, and after fertilization it moves via a series of cytoskeletal reorganizations to form a posterior crescent shape which will segregate into tail muscle [12]–[14] (Fig. 1). In living cells, the myoplasm is easily visible due to differential pigmentation, autofluorescence or via the application of vital mitochondrial dyes [10], [13], [15]–[20]. The eggs of many animals contain aggregates of tightly packed mitochondria, often associated with germ plasm, which migrate together in a mitochondrial cloud, or Balbiani body [21]–[23]. The ascidian myoplasm offers an accessible system to address questions concerning networks of mitochondria, such as their regulation, function, and how they are properly partitioned during cell division. Ascidians are amenable to an increasing battery of experimental approaches including micromanipulation, modification of gene expression or function, live imaging, genetics, proteomics [20], [24]–[28] and as we show here, biochemistry.

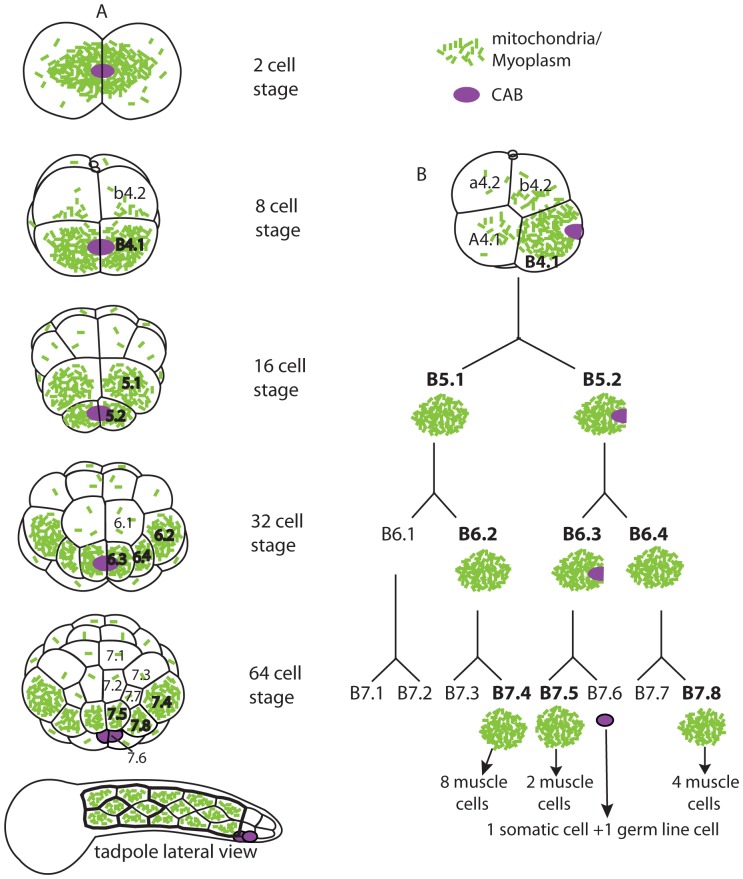

Figure 1. Segregation of the mitochondria-rich myoplasm into the muscle lineage of the ascidian embryo.

Green speckles indicate mitochondria; the violet oval depicts the cortical domain rich in RNA, endoplasmic reticulum and germ plasm known as the CAB (for centrosome attracting body). (A) Drawings of relevant stages of the bilaterally symmetric ascidian embryo. Descendents of the B4.1 vegetal posterior blastomere are labeled. The 2 and 8 cell stages show posterior views; 16, 32, 64 cell stages are vegetal views. (B) a lateral view of the 8 cell stage and lineage of the primary muscle cells. At the 64 cell stage the bulk of the myoplasm partitions into 3 pairs of cells (B7.4, B7.5, B7.8) which give rise to the primary muscle of the tadpole tail, and the CAB domain segregates into B7.6germ line cells. Concerning myoplasm distribution during cell division, there are 3 “equal cleavages” whereby myoplasm is inherited by both daughter cells (1st cleavage, B4.1, and B5.2) and there are 6 “unequal cleavages” whereby myoplasm distributes preferentially to one daughter cell (B5.1, B6.2, B6.3, B6.4 as well as 2nd and 3rd cleavages which are not shown).

The most commonly used antibody tool to study ascidian myoplasm is “NN18”, a monoclonal originally made to a neurofilament preparation from pig spinal cord [29]. NN18, also called NF-160 or NF-M, reacts with the medium molecular weight (160 kDa) neurofilament subunit and labels exclusively neurofilaments in vertebrates as well as crab [30]–[33]. In the ascidian, it was found that NN18 recognizes a 58 kDa protein and strongly labels myoplasm in eggs from numerous species [13], [34]–[37]. The ascidian target of NN18 known as p58 interacts with “myoplasmin” whose sequence has features characteristic of proteins which form filaments [36], [38]. Since the myoplasm can be isolated as a unified mass [37], [39], [40] and early electron microscopy studies suggested that it contains structures resembling intermediate filaments [41]–[43], it was postulated that the ascidian target of NN18 is an intermediate filament-like protein as in vertebrates. However a more recent analysis of the Ciona intestinalis genome showed that ascidians lack the neurofilament (type IV) class of intermediate filaments [44], so the identity of ascidian p58 remains unclear.

Another unresolved question concerns the function of the myoplasm: it is thought to provide abundant energy for contracting myofibrils of the tadpole tail but the original proposition that it harbors molecules involved in myogenesis has not been ruled out. The myogenic determinant Macho RNA [45], [46] is localized to a domain rich in endoplasmic reticulum positioned just adjacent to the myoplasm, known as the CAB (see Fig. 1) [47]–[53]. Macho protein leads to activation of zygotic expression of the muscle-specific transcription factor MyoD in the muscle lineage [54]–[56]. Ascidian oocytes contain a low level of maternal mRNA encoding MyoD [57], [58] however whether a corresponding maternal MyoD protein is present in the egg or myoplasm has not been addressed.

Here we generate a polyclonal antibody against ascidian MyoD, show it labels the myoplasm, and isolate its target from ascidian eggs. We also identify with certainty the target of the standard myoplasm marker antibody NN18. Our unexpected findings have general implications for antibody “specificity” and highlight the necessity for unequivocal validation of antibody tools.

Materials and Methods

For additional methods and details, see Methods S1.

Animals

Adults of Phallusia mammillata were collected in the Mediterranean near Sete, France. All necessary permits were obtained for the described field studies from the Minister of Ecology and Sustainable Development, Marseille. The European ascidian Phallusia is favorable for biochemical approaches and protein purification because it produces large quantities of eggs (up to 1 ml >106 eggs per hermaphroditic animal). Mature eggs are less abundant in Ciona intestinalis oviducts, however the Ciona gonad is an excellent source of maternal protein for biochemistry. This large bean-shaped organ can be up to 1 cm long and contains a virtually pure population of unfertilized eggs and immature oocytes of all stages [59]. Ciona adults were obtained from Roscoff marine station (Brittany, France) or through the National Bio-Resource Project NBRP of MEXT, Japan. For general ascidian protocols, fertilization and culture of embryos, see [20].

Primary antibodies

The NN18-clone, originally generated as one of a panel of monoclonal antibodies to porcine spinal cord [29], was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or ICN (anti-neurofilament 160 mouse monoclonal). Antibody PMF-C13 was produced by injecting a peptide present in PmMRF which is the Phallusia homolog of MyoD (Genbank accession HQ287931) into rabbits; immune serum was affinity purified against bacterially expressed PmMRF (Fig. S1).

Enrichment for proteins with low affinity for ion exchange resin

In initial 2D gels loaded with total protein extract from Phallusia eggs or Ciona ovary, p63 was not abundant enough to be visible by coomassie staining, therefore a sample highly enriched for p63 was prepared by sequential ion exchange chromatography. The majority of egg proteins were eliminated by binding to a saturated DEAE column, and the flowthrough was applied to a second column on which p63 was retained. Fractions were eluted via a step salt gradient and assayed for p63 by immunoblot with PMF-C13; positive fractions were concentrated and loaded onto preparative 2D gels. See Methods S1 for details.

Results

NN18 and PMF-C13 antibodies recognize stable maternal proteins (p58 and p63) which distribute into the muscle lineage of ascidian embryos

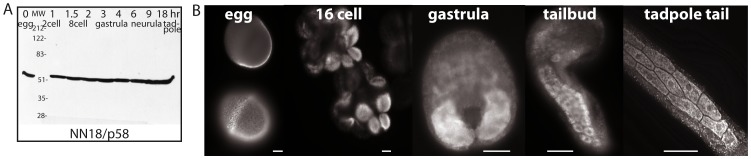

Immunoblots using NN18 monoclonal antibody show that p58 is abundant in unfertilized eggs and remains constantly present throughout embryonic development of Phallusia mammillata (Fig. 2A), a pattern identical to that seen in Ascidia ceratodes [34] and Ciona intestinalis (not shown). In fixed Phallusia embryos, NN18 strongly labels the myoplasm and muscle lineage (Fig. 2B) [13], [49], [52], as has been observed for Ascidia ceratodes, Styela clava, Molgula oculata, Ciona savigny, and Ciona intestinalis [34]–[37].

Figure 2. Distribution of p58 during ascidian embryonic development.

(A) Immunoblot using NN18 antibody on Phallusia mammillata extracts prepared at the indicated stages of development; hr: hours after fertilization. (B) Examples of Phallusia embryos stained with NN18; egg: an equatorial view (top) or surface view (bottom) of the same unfertilized egg; 16 cell: 2 different embryos with 4 posterior cells (B5.1 and B5.2 pairs) labeled. Gastrula: posterior muscle territory is labeled. Tailbud and tadpole tail: individual mononucleate muscle cells are distinguishable. Scale bars are 20 microns in all panels.

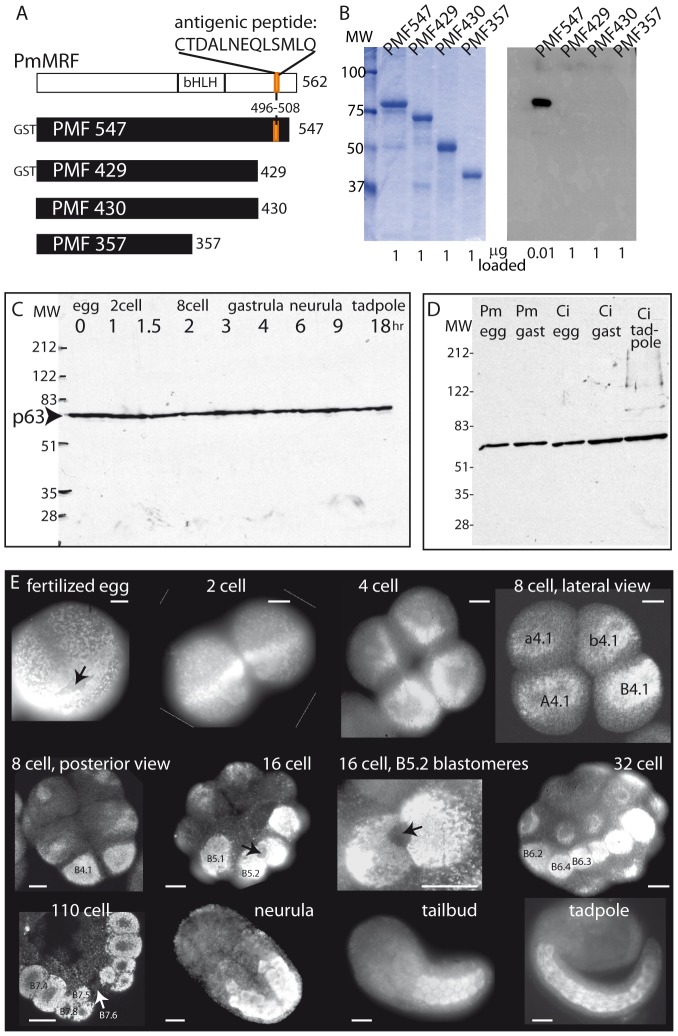

In order to address the question of maternal MyoD protein, we generated a polyclonal antibody using as antigen a 13 amino acid peptide sequence present in the Phallusia MyoD homolog PmMRF (Fig. 3A). This antibody, named PMF-C13, passed tests commonly cited as adequate to verify specificity for its antigen: it specifically recognizes the antigen protein PmMRF produced in bacteria, but not truncated forms of PmMRF which lack the antigenic peptide (Fig. 3B), and in ascidian extracts it strongly labels a single band of the expected size which we denote p63 (Fig. 3C,D). Like p58 (Fig. 2A), p63 is maternally provided and stably present at all embryonic stages in both Phallusia and Ciona (Fig. 3C, D). Immunofluorescence using PMF-C13 purified by affinity chromatography against PmMRF (Fig. S1) showed strong and persistent labeling of the ascidian myoplasm throughout development of Phallusia or Ciona (Fig. 3E), displaying a distribution very similar to that obtained with monoclonal NN18 (Fig. 2B). This localization pattern is surprising, since PmMRF is a myogenic transcription factor expected to be found in the nuclei of muscle cells not in association with a mitochondria-rich domain.

Figure 3. Production of antibody PMF-C13 and distribution of p63 during ascidian embryonic development.

(A) Schematics of PmMRF protein (top line) and four versions produced in bacteria (black bars). bHLH: helix-loop-helix domain diagnostic of MyoD family. The number of amino acids of PmMRF present in each construct is indicated on the right. “GST” indicates that these 2 proteins also contain the 220 amino acids of Glutathione-S-Transferase. The antigenic peptide corresponding to amino acids 496–508 (colored orange) is present in “PMF547” which encodes most of PmMRF, but is absent from the others. (B) Gels containing PmMRF fusion proteins depicted in A were stained with Coomassie blue (left) or immunoblotted with antibody PMF-C13 (right). In each case 1 µg was loaded except for the PMF547 lane of the immunoblot which was loaded with much less protein (10 ng, indicated on the bottom). (C,D) Immunoblots using PMF-C13 antibody on ascidian protein extracts prepared at the indicated stages of development; hr: hours after fertilization. All samples are from Phallusia (Pm) except for three lanes in D which show PMF-C13 also recognizes p63 in Ciona (Ci) extracts. (E) Examples of Phallusia embryos stained with PMF-C13. Scale bars are 20 microns in all panels. The names in white indicate the embryonic stage and the numbers in black indicate the muscle lineage cells at the 4, 8, 16, 32 cell stages (see Fig. 1); the 64 cell stage cell names are indicated on the slightly later 110 cell embryo although B7.4 and B7.8 have already divided. Arrows indicate the cortical CAB which excludes myoplasm and thus is detectable as an unstained region surrounded by myoplasm label.

Thus the identity of p63, like that of p58, remained in question and has important implications for the structure and function of the ascidian myoplasm. In order to determine whether the myoplasm contains a neurofilament-like or MyoD-like protein, we set out to identify with certainty the proteins recognized by NN18 and PMF-C13, p58 and p63.

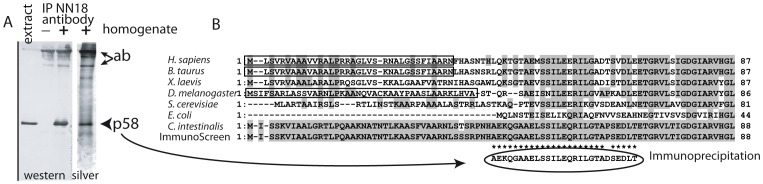

Purification of p58 and identification as ATP synthase

The identification of p58 was accomplished by 2 independent methods: immuno-precipitation and immunoscreening. Sepharose resin coupled to NN18 antibody was incubated with a soluble fraction from Ciona gonad homogenate and bound proteins were separated on a non-reducing SDS-PAGE gel, so that the intact NN18 IgG would migrate at a high molecular weight well separated from the target protein. p58 was successfully immunoprecipitated as determined by immunoblot (Fig. 4A, “western”), and a duplicate lane silver-stained for total protein (Fig. 4B, right) showed that it was highly purified and abundant enough to obtain N-terminal sequence. The resulting sequence of 27 amino acid residues (circled in Fig. 4B) is identical in 26 positions to residues 44–70 of Ciona mitochondrial-type ATP synthase alpha-subunit. As this was an unexpected result, we also screened a CionacDNA expression library with NN18 antibody. All positive clones encoded the same protein: ATP synthase alpha-subunit “CiATPsynA” (“Immunoscreen” line, Fig. 4B). The first 43 amino acids of Ciona ATP synthase missing from the immunoprecipitated p58 correspond to the transit signal peptide (boxed in Fig. 4B and Fig. S2C) which targets proteins to mitochondria and is cleaved during the import process. Thus p58 protein recognized by the neurofilament NN18 antibody in the Ciona egg is the mature form of ATPsynthase alpha subunit. This protein along with ATP synthase beta subunit make up the intramitochondrial F1 portion of the enzyme complex which is attached to the F0 portion embedded in the mitochondrial membrane. This cross reaction is somewhat of a mystery, as there are no significant stretches of homology between ascidian ATP synthase alpha (Fig. S2B) and the initial antigenic protein, porcine NeuroFilament-M [29] (Fig. S2A), but it remains possible that they possess a short stretch of identical amino acids or a resemblance in tertiary structure.

Figure 4. Purification of p58 by immunoprecipitation.

(A) Beads to which the antibody NN18 was bound were incubated with (+) or without (−)Ciona oocyte homogenate and eluted proteins were subjected to immunoblot (left) or silver stain (right). The major proteins in the immunoprecipitate are p58 (arrow head) and the monoclonal antibody (arrows) which migrates as a large IgG because of the nondenaturing conditions of the gel (see text and methods). (B) N-terminal sequence of immunoprecipitated p58 (bottom line, circled) compared to ATP synthase alpha-subunit from diverse species; asterisks * indicate residues which are identical between p58 protein and Ciona ATP synthase alpha subunit. Immunoprecipitated p58 lacks the first 43 amino acids of ATP synthase which correspond to reported mitochondrial signal peptides (boxed). The “ImmunoScreen” line is a translation of the cDNA clones (NP_001027729) obtained by screening an expression library with NN18 antibody, which is identical to the ATP synthase gene model (KH.C10.579) annotated in the Ciona genome database, except in one position due to a polymorphism. See Fig. S2 for the complete alignment and database accession numbers.

Purification of p63 and identification as HSP60

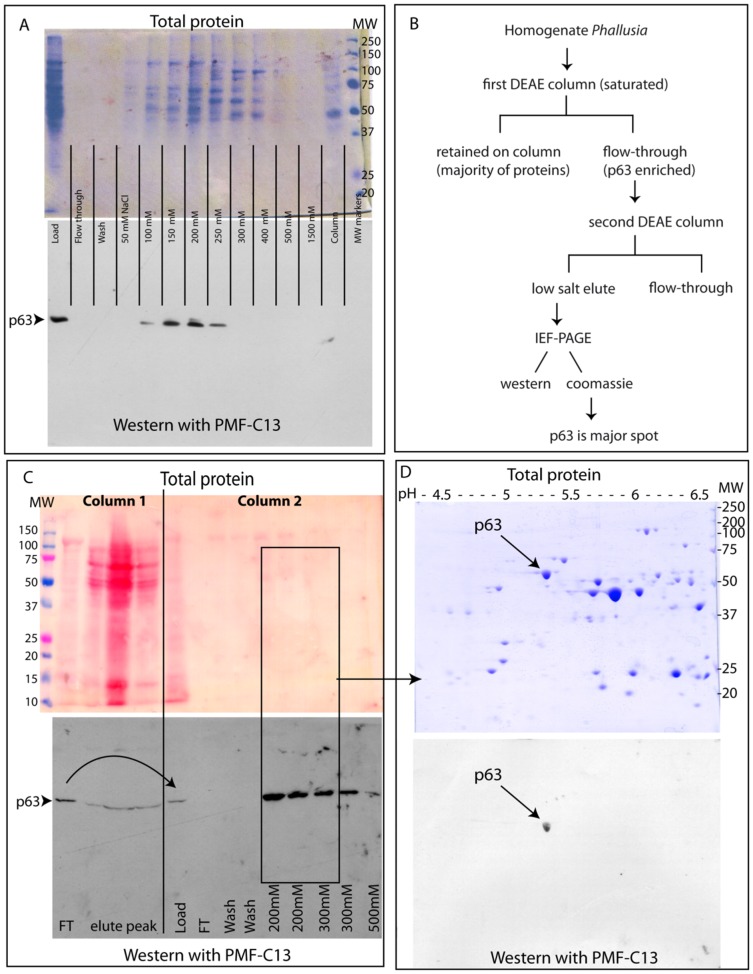

Attempts at immunoprecipitation and immunoscreening with PMF-C13 were unsuccessful, and in such cases the target protein must be purified biochemically. p63 was isolated from Phallusia eggs by a combination of ion exchange chromatography and isoelectric focusing (Fig. 5). Initial immunoblots of 2D gels covering a range of pH revealed that the isoelectric point of p63 was approximately 5.2 but that it was not abundant enough to be distinguished as a major spot within the constellation of total egg proteins. An enrichment of p63 was obtained by a strategy of 2 sequential ion exchange columns (schematized in Fig. 5B). Initial DEAE columns indicated a relatively weak affinity for anionic exchange DEAE resin (Fig. 5A). A first DEAE column was intentionally overloaded with saturating amount of Phallusia egg extract (Fig. 5C), selecting for binding of proteins with stronger affinity for DEAE. Under these conditions the majority of proteins (over 80%) were retained, but p63 flowed through the column with a minority of proteins having weaker affinity for DEAE (Fig. 5C “column 1” FT). The flow-through from this first column which was poor in protein content but enriched for p63 was used to load a second non-saturated ion exchange column, on which p63 was retained (Fig. 5C “column 2”). The fractions eluted with 200 mM NaCl highly enriched for p63 were concentrated and loaded on two identical isoelectric focusing gels followed by PAGE.

Figure 5. Purification of p63 using successive DEAE ion exchange columns and IEF-PAGE.

In A, C and D, pairs of identical gels show distribution of p63 (western blot with PMF-C13, lower gels) compared to total protein (upper gels). (A) Total Phallusia egg extract prepared at low ionic strength was passed through an ion exchange column, eluted with a step salt gradient and representative fractions were analyzed; p63 (arrowhead) elutes at 100–200 mMNaCl but is not well separated from the majority of proteins. (B) Schematic of biochemical approach used to enrich p63 before 2D-electrophoresis. (C) Scale-up and sequential ion exchange columns. Column 1: The majority of proteins are retained on the overloaded column (“elute peak”) but p63 (arrowhead) passes through. The flow through (FT) from the first column (left) was loaded onto a second column as indicated by the curved arrow. Column 2: p63 elutes at 200 mM salt as in A. A fraction enriched for p63 (black rectangle) was loaded onto the duplicate 2D gels shown in D: the p63 spot (arrow) is abundant and well separated from other proteins.

One preparative 2D gel was stained with Coomassie blue and the twin gel was used for western blot with antibody PMF-C13 (Fig. 5D). A precise overlay of the blot and gel (see Methods S1) revealed that p63 was sufficiently abundant and pure to be excisedand subjected to mass spectrometry analysis. Peptide sequences obtained were compared to databases of the translated Ciona genome and subsequently to that of Phallusia ESTs. In both cases the strongest match was mitochondrial Heat Shock Protein 60 (HSP60) (Fig. S3A), which is a molecular chaperone of the GroEL family required for protein folding and mitochondrial activity. Ascidian HSP60 shares a similar molecular weight and isoelectric point with the antigen protein PmMRF (Fig. S3B, legend), but there is no obvious sequence or structural similarity between the two to explain the affinity of antibody PMF-C13. Nor could this target protein have been predicted: a search of Ciona gene models shows that 5 proteins contain a stretch of 6 consecutive amino acids in common with the antigenic peptide CTDALNEQLSMLQ, and over 200 Ciona proteins contain a 5 amino acid stretch, however the bona fide antibody target HSP60 is not on that list.

ATP synthase and HSP60 are located on the inner mitochondrial membrane

Thus both the NN18 and PMF-C13 antibodies recognize not the original antigens, but instead two well conserved proteins predicted to localize in mitochondria.

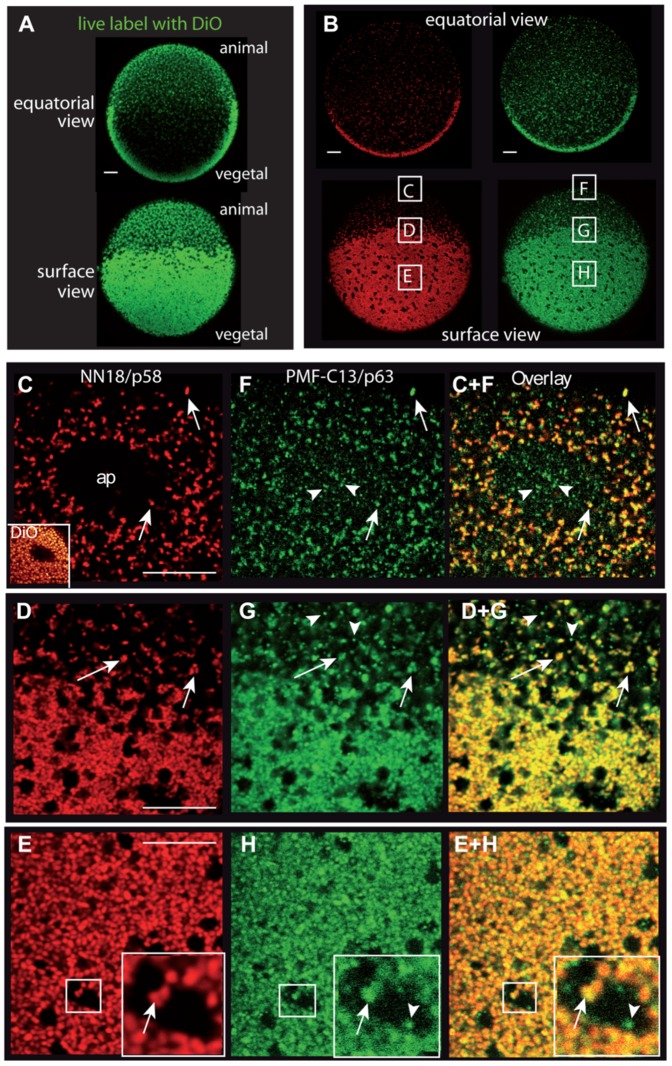

The distribution of ATP synthase and HSP60 in whole eggs and embryos was examined by high resolution confocal microscopy (Fig. 6). In the unfertilized ascidian egg three peripheral regions can be distinguished: the vegetal layer containing the myoplasm basket rich in mitochondria (Fig. 6E and H), the animal hemisphere relatively poor in mitochondria (Fig. 6C and F), and a transition zone at the equator (Fig. 6D and G). Both NN18 (red, Fig. 6C–E) and PMF-C13 (green, Fig. 6F–H) recognize the same individual mitochondria in every region of the egg (yellow overlay, arrows in Fig. 6). Absence of signal corresponded to cell regions lacking mitochondria such as the animal pole (Fig. 6C “ap”), nuclei (Fig. S4 “n”) and the CAB (arrows in Fig. 3E, see Fig. 1). While a previous study indicated that HSP60 is found preferentially in myoplasm mitochondria [60], we observe that mitochondria in all cells of embryos and tadpoles are labelled (Fig. S4) and conclude that the myoplasm staining is due to the massive enrichment of mitochondria in this domain. In addition PMF-C13 reproducibly labeled smaller non-mitochondrial spots (arrowheads Fig. 6 F–H) distributed throughout most of the cytoplasm. NN18 labelled exclusively mitochondria in these preparations, however the use of sub-cellular fractionation followed by immunnoblotting indicates that p58 is also present in non-mitochondrial cytoplasm [61].

Figure 6. p58/ATP Synthase and p63/HSP60 localize to all mitochondria in the ascidian egg.

Confocal views of Phallusia eggs labeled in vivo for mitochondria with DiOC2(3) (A) or fixed and double immunolabelled (B–H) with NN18 (red) or PMF-C13 (green). Eggs are oriented with the animal pole up and the vegetal hemisphere containing the myoplasm basket down. A and B show low magnification views of the center (top) or the surface (bottom) of the same egg. Boxes in B indicate positions zoomed to high magnification to detail the animal pole (C, F), the equatorial region (D,G) or the vegetal myoplasm (E,H). Yellow overlay (right panels) shows colocalization; both antibodies label individual mitochondria (arrows) and PMF-C13 also labels smaller cytoplasmic particles (arrowheads). The animal pole region (ap in C) which contains the meiotic spindle is devoid of mitochondria (as shown by live DiO labeling, inset in C). Scale bars are 10 microns in all panels.

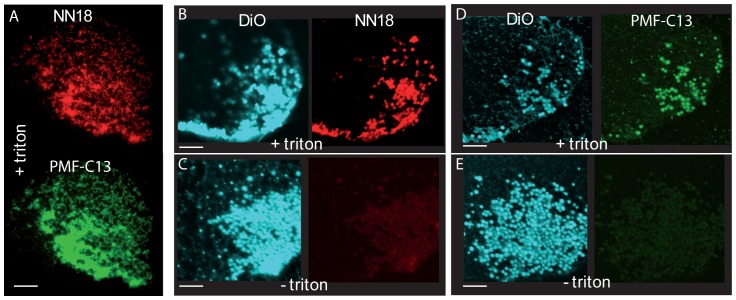

In order to confirm mitochondrial association we used isolated cortices (Fig. 7), which are open-cell preparations of plasma membrane and adherent organelles [62], [63]. We have noted that cortices prepared from cleaving ascidian eggs retain patches of myoplasm, yielding a coverslip of semi-purified mitochondria. Such cortical preparations were first labeled with DiO(C6)3 to identify mitochondria, then fixed and immunolabled with antibodies. On cortices treated with triton in order to expose the inner mitochondrial membrane, NN18 and PMF-C13 antibodies label spots which colocalize with each other (Fig. 7A, B, D). In the absence of permeabilization with detergent however, antibodies only have access to the outer surface of mitochondria and NN18 and PMF-C13 do not label the isolated cortex (Fig. 7C and E, right panels). These results demonstrate that ATP synthase and HSP60 are present within mitochondria in ascidian eggs. Other subcellular localizations, such as the granules observed in Fig. 6 F–H, would not be detectable by this method however since during cortex preparation, cytosol and structures not adherent to the plasma membrane are eliminated.

Figure 7. Cortices isolated from fertilized eggs and labeled with DiOC6(3) to show mitochondria (blue) and with antibodies NN18 (red) or PMF-C13 (green).

(A,B,D) “+ triton”: cortices immunolabeled after permeabilization with detergent. (C,E) “− triton”: cortices immunolabeled in the absence of permeabilization: no antibody signal is detected. Scale bars are 5 microns.

Discussion

In this study the application of biochemical methods to ascidian eggs allowed us to identify unambiguously two proteins recognized by myoplasm antibodies. Somewhat alarmingly, in both cases the antibody's target was unrelated to the original antigenic protein. The polyclonal antibody PMF-C13 showed a strong affinity for its intended target PmMRF (Figs. 3, 5, S1) and yet labels HSP60 (Figs. 5, S3). Equally unexpectedly, we find that the monoclonal antibody NN18 recognizes a protein wholly unrelated to the intermediate filament antigen, ascidian ATP synthase subunit alpha (Figs. 2, 4, S2). Thus a significant message of the present work is that use of unvalidated antibodies can lead to erroneous conclusions, such as in our case that the myoplasm is structured by intermediate filaments, or that the MyoD transcription factor localizes to mitochondria.

While the causes of these cross-reactions are unknown, their occurrence may be representative of general situations which lead to mistaken identity, some of which have been documented [4], [6], [64], [65]. For instance a secondary affinity for an abundant protein may be revealed when the presumed antigen is not present in the tissue of interest, as is the case for the NN18 antibody. The Ciona genome encodes 5 intermediate filament genes [44] but no homolog to the neurofilamant (typeIV) class which antibody NN18 recognizes in vertebrates. ATP synthase is one of the most abundant proteins in eggs as determined by analysis of the Ciona proteome (http://cipro.ibio.jp/2.5/expression profile KH.C10.579 [66]. The constant level of ATP synthase throughout embryonic development (Fig. 2A and [34] likely reflects stable maternal protein, since we find that the ATP synthase transcript is abundant in the egg and decreases during cleavage stages (Fig. S5), a pattern like that of the transcript encoding ascidian ATP translocase [67]. It is worth pointing out that since p58/ATP synthase is so stable and well-characterized, the commercially available NN18 monoclonal can be used by the ascidian community as a reliable standard to compare protein amount among samples.

In the case of the polyclonal PMF-C13, we found it recognizes HSP60 (Fig. 5, S3) even though it passed tests commonly cited to assert antigen specificity, namely that it labels a single band of the expected size and isoelectric point in the tissue of interest, and it recognizes the antigen (PmMRF) produced in a heterologous system but not truncated forms lacking the peptide sequence (Figs. 3, 5, S1). HSP60 contains 3 short sequences in common with the antigenic peptide (DAL, LNE, DALN, shaded in Fig. S3C) which could function as epitope. Indeed, since any short series of amino acids will be fortuitously present in numerous polypeptide chains, such a misleading binding of antibodies to unexpected targets may be relatively common. It is possible that antibody PMF-C13 also recognizes PmMRF in ascidian extracts, but given their similar molecular weights (Fig. S3 legend), the band corresponding to this transiently expressed transcription factor would be obscured by the stronger signal of HSP60. HSP60 is primarily a mitochondrial protein, but it is also found the cytosol and on the cell surface where it is implicated in diverse cellular functions including protein trafficking through the plasma membrane, cell signaling, apoptosis and immunological response [68]–[74]. The non-mitochondrial spots labeled by PMF-C13 (arrowheads in Fig. 6 F–H) are reminiscent of the HSP60-containing cytoplasmic granules of unknown function observed in mammalian cells [68]. HSP60 binds the translation factor YB-1 in the cytoplasm of mammalian cells [72] suggesting that the cytoplasmic HSP60 may be part of a polysome RNP complex. Interestingly in Ciona YB-1 binds to and regulates translation of maternal mRNAs including the localized determinants macho and PEM [75]. The ascidian and in particular the transparent Phallusia embryo which is favorable for live imaging [13], [20], [25] is a promising model for investigating the multiple locations and functions of HSP60 and of ATP synthase.

What methods are available for definitive validation of antibody tools and when should they be applied? It is well known that fixation conditions can radically alter the perceived distribution of a protein [6], [76]–[78] thus leading to potential misinterpretation about a protein's bona fide localization or function. To avoid fixation artifacts and to palliate the lack of antibodies it is common to infer protein localization by following fluorescently-tagged protein fusions in living cells, however an exogenous overexpressed modified protein may not faithfully reflect the distribution of the endogenous protein. Thus in general, when the distribution of a protein determined by immunolabelling is novel, unexpected, or unlike that of the GFP-tagged version, it is necessary to verify the antibody target in the species under study. In genetic model systems, homologous gene replacement or mutant collections can be employed to demonstrate that an altered coding sequence leads to the expected change in size or localization of the recognized protein. In many species and cell types one can use RNA interference or morpholino oligonucleotides to inhibit translation of a specific RNA transcript and show that there is a corresponding reduction of the candidate band or immunofluorescence signal. However proteins which are very stable and/or are provided maternally will be little affected by this type of translational inhibition. Moreover these methods are indirect: knockdown of factors involved in transcription or signaling pathways for example may also reduce the levels of their targets. Ultimately the most direct way to determine an antibody's target is to isolate it from the material of interest by the methods described in the present article: immunoprecipitation, immunoscreening of an expression library, or biochemical purification. This latter approach should become less onerous with the development of large scale proteomics, whereby researchers or commercial companies can pre-verify uncharacterized antibodies.

Supporting Information

Purification of anti-peptide antibody PMF-C13 on PmMRF fusion protein. 15 ml crude rabbit serum was clarified by centrifugation and loaded onto an affigel affinity column coupled to the fusion protein encoded by the “PMF547” construct containing 547 of the 562 amino acids comprising full length PmMRF (see Fig. 3). (A) The blue line indicates amount of protein (OD260) which has passed through the BioLogic HPLC sensor during loading, washes, and acid elution. (B) Representative fractions were migrated by SDS-PAGE and stained with coomassie blue. Arrows indicate purified antibody heavy chain which has been bound to and eluted from the PmMRF fusion protein column. When an identical aliquot of antiserum was loaded onto a similar column coupled to the fusion protein encoded by the “PMF429” construct which contains 429 amino acids of PmMRF and lacks the immunogenic peptide sequence (see Fig. 3), no antibody was retained or eluted.

(TIF)

Amino acid sequences of proteins recognized by antibody NN18. (A) NF-M, the antigen the NN18 monoclonal antibody was originally raised against (porcine neurofilament medium, XP_001925857.1), is a protein of 934 amino acids and molecular weight 160 kD. (B) p58 is ATP synthase alpha subunit, the protein recognized by NN18 in ascidian eggs. Ciona intestinalis ATP synthase alpha (Genbank accession number AB071977, gene model KH.C10.579 on Ciona genome browser http://hoya.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp/cgi-bin/gbrowse/kh/) [1] is a protein of 554 amino acids with calculated molecular weight 59.97 kD. Phallusia mammillata ATP synthase alpha (compiled by manual assembly of unpublished EST data on the bioinformatics server at Villefranche) is a protein of 556 amino acids and calculated molecular weight 60.58 kD. (C) Alignment of the complete sequences of ATP synthase alpha-subunit from Homo sapiens (NP_001001937), Bos taurus (NP_777109), Xenopus laevis (NP_001080447), Drosophila melanogaster (NP_726243), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (NP_009453), Escherichia coli (NP_418190), Ciona intestinalis (KH.C10.579.v1.A.SL1-1). “Cloning/NN18” is the complete sequence of the cDNA clone obtained by immunoscreening a Ciona expression library with NN18. “Immunoprecipitation/NN18” and “Mitochondrial Targeting Signal” are as described in Fig. 2. The ATP binding (GDRQTGKT) and ATPase (PAINVGLSVS) sequences are also indicated.

(TIF)

Amino acid sequences of the 2 proteins recognized by antibody PMF-C13. (A) The protein purified in Fig. 5 was subjected to tandem MS/MS sequencing, and resultant peptides compared to both Ciona and Phallusia gene model predictions. The 4 aligned peptides showed a match to the same protein HSP60, with a higher percentage of sequence identity (shaded) to Phallusia mammillata, the species from which p63 was isolated, than to Ciona. Ciona HSP60 (gene model KH.C6.85 on Ciona genome browser http://ghost.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp/SearchGenome kh.html [1] is a protein of 573 amino acids with theoretical molecular weight 61.4 kD and isoelectric point 5.36. Phallusia HSP60 is a protein of 577 amino acids with theoretical molecular weight 61.9 kD and isoelectric point 5.40. The PmHSP60 sequence was compiled by manual assembly of unpublished Phallusia EST data on the bioinformatics server “Octopus” at Villefranche. This is a first demonstration that the well-developed Ciona proteomics database [2] can be used to identify proteins from the related species Phallusia mammillata. (B) PmMRF (MRF for Myogenic Regulatory Factor) is the Phallusia mammillata homolog of MyoD; the 13 amino acid C-terminal peptide used as antigen is highlighted. PmMRF (accession number HQ287931) is a protein of 562 amino acids with theoretical molecular weight 62.1 kD and isoelectric point 5.02. (C) The short highlighted sequences are regions of ascidian HSP60 with at least 3 consecutive amino acids identical to the immunogenic peptide.

(TIF)

Posterior region of Phallusia embryos stained with antibodies NN18 (red) and PMF-C13 (green). (A) Muscle precursor cells in 64 cell stage embryo, 4 hours after fertilization. n: nucleus. (B) muscle cells in a portion of the tadpole tail, which is formed 18 hours after fertilization. Non-myoplasm mitochondria which are outside of muscle lineage (arrows) are labeled as well as myoplasm mitochondria. Scale bars are 10 microns.

(TIF)

Spatial and temporal expression pattern of CiATPsynthase mRNA. (A) RT-PCR using primers specific for ATP synthase alpha or for tubulin control. (B) Whole mount in situ hybridization of embryos fixed at the indicated times in development. CiATPsyn transcript accumulates during oogenesis and is evenly distributed in the unfertilized egg. During cleavage stages the amount of CiATPsyn message decreases and is hardly detectable in neurula and later stages. Scale bars are 50 microns.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyoko Hatano (Kyoto University) for protein identification by N terminal amino acid sequencing using Sanger's method and Regis Lavigne (Proteomics Core Facility Biogenouest) and Mia Nakachi (Shimoda Marine Research Center) for valuable assistance with protein identification by mass spectrometry and de novo sequencing. We are grateful to Jian Wang (Boston) and members of our laboratory especially Patrick Chang, Evelyn Houliston, and Alexandre Paix for helpful discussions. We thank Nori Satoh and Yutaka Satou for providing a C. intestinalis gene collection, Philippe Dru for help with bioinformatics, and Lydia Besnardau for technical assistance. C. intestinalis adults were provided through the National Bio-Resource Project (NBRP) of MEXT, Japan.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by grants to CS from the French Foundations for Research on Muscle (AFM), and Cancer (ARC) and the French National Research Agency (ANR), a grant to TN from MEXT, and a grant to HI from the Japan Science Society. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Deutsch EW, Ball CA, Berman JJ, Bova GS, Brazma A, et al. (2008) Minimum information specification for in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry experiments (MISFISHIE). Nat Biotechnol 26: 305–312 doi:10.1038/nbt1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. True LD (2008) Quality control in molecular immunohistochemistry. Histochem Cell Biol 130: 473–480 doi:10.1007/s00418-008-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saper CB (2009) A guide to the perplexed on the specificity of antibodies. J Histochem Cytochem 57: 1–5 doi:10.1369/jhc.2008.952770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bordeaux J, Welsh A, Agarwal S, Killiam E, Baquero M, et al. (2010) Antibody validation. BioTechniques 48: 197–209 doi:10.2144/000113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burry RW (2011) Controls for immunocytochemistry: an update. J Histochem Cytochem 59: 6–12 doi:10.1369/jhc.2010.956920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schnell U, Dijk F, Sjollema KA, Giepmans BNG (2012) Immunolabeling artifacts and the need for live-cell imaging. Nat Methods 9: 152–158 doi:10.1038/nmeth.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delsuc F, Brinkmann H, Chourrout D, Philippe H (2006) Tunicates and not cephalochordates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates. Nature 439: 965–968 doi:10.1038/nature04336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lemaire P, Smith WC, Nishida H (2008) Ascidians and the plasticity of the chordate developmental program. Curr Biol 18: R620–631 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Satoh N (2003) The ascidian tadpole larva: comparative molecular development and genomics. Nat Rev Genet 4: 285–295 doi:10.1038/nrg1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conklin EG (1905) The organization and cell lineage of the ascidian egg. J Acad Natl Sci Philadelphia 13: 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert SF (2010) Early Development in Selected Invertebrates. Developmental Biology. pp. 237–241.

- 12. Sawada T, Schatten G (1989) Effects of cytoskeletal inhibitors on ooplasmic segregation and microtubule organization during fertilization and early development in the ascidian Molgula occidentalis. Dev Biol 132: 331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roegiers F, Djediat C, Dumollard R, Rouvière C, Sardet C (1999) Phases of cytoplasmic and cortical reorganizations of the ascidian zygote between fertilization and first division. Development 126: 3101–3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sardet C, Paix A, Prodon F, Dru P, Chenevert J (2007) From oocyte to 16-cell stage: cytoplasmic and cortical reorganizations that pattern the ascidian embryo. Dev Dyn 236: 1716–1731 doi:10.1002/dvdy.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reverberi G (1956) The mitochondrial pattern in the development of the ascidian egg. Experentia 12: 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zalokar M, Sardet C (1984) Tracing of cell lineage in embryonic development of Phallusia mammillata (Ascidia) by vital staining of mitochondria. Dev Biol 102: 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishida H (1992) Regionality of egg cytoplasm that promotes muscle differentiation in embryo of the ascidian, Halocynthia roretzi. Development 116: 521–529. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roegiers F, McDougall A, Sardet C (1995) The sperm entry point defines the orientation of the calcium-induced contraction wave that directs the first phase of cytoplasmic reorganization in the ascidian egg. Development 121: 3457–3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oka T, Amikura R, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto H, Nishida H (1999) Localization of mitochondrial large ribosomal RNA in the myoplasm of the early ascidian embryo. Dev Growth Differ 41: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sardet C, McDougall A, Yasuo H, Chenevert J, Pruliere G, et al. (2011) Embryological methods in ascidians: the Villefranche-sur-Mer protocols. Methods Mol Biol 770: 365–400 doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-210-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kloc M, Bilinski S, Etkin LD (2004) The Balbiani body and germ cell determinants: 150 years later. Curr Top Dev Biol 59: 1–36 doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(04)59001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dumollard R, Duchen M, Sardet C (2006) Calcium signals and mitochondria at fertilisation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 17: 314–323 doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou RR, Wang B, Wang J, Schatten H, Zhang YZ (2010) Is the mitochondrial cloud the selection machinery for preferentially transmitting wild-type mtDNA between generations? Rewinding Müller's ratchet efficiently. Curr Genet 56: 101–107 doi:10.1007/s00294-010-0291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sasakura Y, Oogai Y, Matsuoka T, Satoh N, Awazu S (2007) Transposon mediated transgenesis in a marine invertebrate chordate: Ciona intestinalis. Genome Biol 8 Suppl 1: S3 doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-s1-s3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prodon F, Chenevert J, Hébras C, Dumollard R, Faure E, et al. (2010) Dual mechanism controls asymmetric spindle position in ascidian germ cell precursors. Development 137: 2011–2021 doi:10.1242/dev.047845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Endo T, Ueno K, Yonezawa K, Mineta K, Hotta K, et al. (2011) CIPRO 2.5: Ciona intestinalis protein database, a unique integrated repository of large-scale omics data, bioinformatic analyses and curated annotation, with user rating and reviewing functionality. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D807–814 doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stolfi A, Christiaen L (2012) Genetic and Genomic Toolbox of the Chordate Ciona intestinalis. Genetics 192: 55–66 doi:10.1534/genetics.112.140590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vierra DA, Irvine SQ (2012) Optimized conditions for transgenesis of the ascidian Ciona using square wave electroporation. Dev Genes Evol 222: 55–61 doi:10.1007/s00427-011-0386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Debus E, Weber K, Osborn M (1983) Monoclonal antibodies specific for glial fibrillary acidic (GFA) protein and for each of the neurofilament triplet polypeptides. Differentiation 25: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Balaratnasingam C, Morgan WH, Bass L, Kang M, Cringle SJ, et al. (2011) Axotomy-induced cytoskeleton changes in unmyelinated mammalian central nervous system axons. Neuroscience 177: 269–282 doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arboleda D, Forostyak S, Jendelova P, Marekova D, Amemori T, et al. (2011) Transplantation of predifferentiated adipose-derived stromal cells for the treatment of spinal cord injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol 31: 1113–1122 doi:10.1007/s10571-011-9712-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Franke FE, Schachenmayr W, Osborn M, Altmannsberger M (1991) Unexpected immunoreactivities of intermediate filament antibodies in human brain and brain tumors. Am J Pathol 139: 67–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corrêa CL, da Silva SF, Lowe J, Tortelote GG, Einicker-Lamas M, et al. (2004) Identification of a neurofilament-like protein in the protocerebral tract of the crab Ucides cordatus. Cell Tissue Res 318: 609–615 doi:10.1007/s00441-004-0992-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swalla BJ, Badgett MR, Jeffery WR (1991) Identification of a cytoskeletal protein localized in the myoplasm of ascidian eggs: localization is modified during anural development. Development 111: 425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jeffery WR, Swalla BJ (1992) Factors necessary for restoring an evolutionary change in an anural ascidian embryo. Developmental Biology 153: 194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chiba S, Miki Y, Ashida K, Wada MR, Tanaka KJ, et al. (1999) Interactions between cytoskeletal components during myoplasm rearrangement in ascidian eggs. Dev Growth Differ 41: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marikawa (1995) Distribution of myoplasmic cytoskeletal domains among egg fragments of the ascidian Ciona savignyi: the concentration of the deep filament lattice in the fragment enriched in muscle determinants. J Exp Zool 271: 348–355. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nishikata T, Wada M (1996) Molecular characterization of myoplasmin-C1: a cytoskeletal component localized in the myoplasm of the ascidian egg. Dev Genes Evol 206: 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jeffery WR (1985) Identification of proteins and mRNAs in isolated yellow crescents of ascidian eggs. J Embryol Exp Morphol 89: 275–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nishikata T, Mita-Miyazawa I, Deno T, Satoh N (1987) Monoclonal antibodies against components of the myoplasm of eggs of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis partially block the development of muscle-specific acetylcholinesterase. Development 100: 577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jeffery WR, Meier S (1983) A yellow crescent cytoskeletal domain in ascidian eggs and its role in early development. Dev Biol 96: 125–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jeffery WR (1995) Development and evolution of an egg cytoskeletal domain in ascidians. Curr Top Dev Biol 31: 243–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satoh N (1994) Developmental Biology of Ascidians. Cambridge University Press.

- 44. Karabinos A, Zimek A, Weber K (2004) The genome of the early chordate Ciona intestinalis encodes only five cytoplasmic intermediate filament proteins including a single type I and type II keratin and a unique IF-annexin fusion protein. Gene 326: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nishida H, Sawada K (2001) macho-1 encodes a localized mRNA in ascidian eggs that specifies muscle fate during embryogenesis. Nature 409: 724–729 doi:10.1038/35055568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sawada K, Fukushima Y, Nishida H (2005) Macho-1 functions as transcriptional activator for muscle formation in embryos of the ascidian Halocynthia roretzi. Gene Expr Patterns 5: 429–437 doi:10.1016/j.modgep.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nishikata T, Hibino T, Nishida H (1999) The centrosome-attracting body, microtubule system, and posterior egg cytoplasm are involved in positioning of cleavage planes in the ascidian embryo. Dev Biol 209: 72–85 doi:10.1006/dbio.1999.9244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sardet C, Nishida H, Prodon F, Sawada K (2003) Maternal mRNAs of PEM and macho 1, the ascidian muscle determinant, associate and move with a rough endoplasmic reticulum network in the egg cortex. Development 130: 5839–5849 doi:10.1242/dev.00805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Patalano S, Prulière G, Prodon F, Paix A, Dru P, et al. (2006) The aPKC-PAR-6-PAR-3 cell polarity complex localizes to the centrosome attracting body, a macroscopic cortical structure responsible for asymmetric divisions in the early ascidian embryo. J Cell Sci 119: 1592–1603 doi:10.1242/jcs.02873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Negishi T, Takada T, Kawai N, Nishida H (2007) Localized PEM mRNA and protein are involved in cleavage-plane orientation and unequal cell divisions in ascidians. Curr Biol 17: 1014–1025 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Prodon F, Yamada L, Shirae-Kurabayashi M, Nakamura Y, Sasakura Y (2007) Postplasmic/PEM RNAs: a class of localized maternal mRNAs with multiple roles in cell polarity and development in ascidian embryos. Dev Dyn 236: 1698–1715 doi:10.1002/dvdy.21109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Paix A, Yamada L, Dru P, Lecordier H, Pruliere G, et al. (2009) Cortical anchorages and cell type segregations of maternal postplasmic/PEM RNAs in ascidians. Dev Biol 336: 96–111 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paix A, Le Nguyen PN, Sardet C (2011) Bi-polarized translation of ascidian maternal mRNA determinant pem-1 associated with regulators of the translation machinery on cortical Endoplasmic Reticulum (cER). Developmental Biology 357: 211–226 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meedel TH, Chang P, Yasuo H (2007) Muscle development in Ciona intestinalis requires the b-HLH myogenic regulatory factor gene Ci-MRF. Dev Biol 302: 333–344 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kubo A, Suzuki N, Yuan X, Nakai K, Satoh N, et al. (2010) Genomic cis-regulatory networks in the early Ciona intestinalis embryo. Development 137: 1613–1623 doi:10.1242/dev.046789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kugler JE, Gazdoiu S, Oda-Ishii I, Passamaneck YJ, Erives AJ, et al. (2010) Temporal regulation of the muscle gene cascade by Macho1 and Tbx6 transcription factors in Ciona intestinalis. J Cell Sci 123: 2453–2463 doi:10.1242/jcs.066910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Satoh N, Araki I, Satou Y (1996) An intrinsic genetic program for autonomous differentiation of muscle cells in the ascidian embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9315–9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Meedel TH, Lee JJ, Whittaker JR (2002) Muscle development and lineage-specific expression of CiMDF, the MyoD-family gene of Ciona intestinalis. Dev Biol 241: 238–246 doi:10.1006/dbio.2001.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Prodon F, Chenevert J, Sardet C (2006) Establishment of animal-vegetal polarity during maturation in ascidian oocytes. Dev Biol 290: 297–311 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bates WR, Bishop CD (1996) Localization of constitutive heat shock proteins in developing ascidians. Development, Growth & Differentiation 38: 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ishii H, Kunihiro S, Tanaka M, Hatano K, Nishikata T (2012) Cytosolic subunits of ATP synthase are localized to the cortical endoplasmic reticulum-rich domain of the ascidian egg myoplasm. Development, Growth & Differentiation 54: 753–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sardet C, Speksnijder J, Terasaki M, Chang P (1992) Polarity of the ascidian egg cortex before fertilization. Development 115: 221–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sardet C, Prodon F, Dumollard R, Chang P, Chênevert J (2002) Structure and function of the egg cortex from oogenesis through fertilization. Dev Biol 241: 1–23 doi:10.1006/dbio.2001.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Willingham MC (1999) Conditional epitopes. is your antibody always specific? J Histochem Cytochem 47: 1233–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Michel MC, Wieland T, Tsujimoto G (2009) How reliable are G-protein-coupled receptor antibodies? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 379: 385–388 doi:10.1007/s00210-009-0395-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nomura M, Nakajima A, Inaba K (2009) Proteomic profiles of embryonic development in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Dev Biol 325: 468–481 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Miya T, Makabe K, Satoh N (1994) Expression of a gene for major mitochondrial protein, ADP/ATP tranlocase, during embryogenesis in the ascidian Halocynthia roretzi. Development, Growth & Differentiation 36: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Soltys BJ, Gupta RS (1996) Immunoelectron microscopic localization of the 60-kDa heat shock chaperonin protein (Hsp60) in mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res 222: 16–27 doi:10.1006/excr.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pfister G, Stroh CM, Perschinka H, Kind M, Knoflach M, et al. (2005) Detection of HSP60 on the membrane surface of stressed human endothelial cells by atomic force and confocal microscopy. J Cell Sci 118: 1587–1594 doi:10.1242/jcs.02292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chandra D, Choy G, Tang DG (2007) Cytosolic accumulation of HSP60 during apoptosis with or without apparent mitochondrial release: evidence that its pro-apoptotic or pro-survival functions involve differential interactions with caspase-3. J Biol Chem 282: 31289–31301 doi:10.1074/jbc.M702777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cappello F, Conway de Macario E, Marasà L, Zummo G, Macario AJL (2008) Hsp60 expression, new locations, functions and perspectives for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Biol Ther 7: 801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ohashi S, Atsumi M, Kobayashi S (2009) HSP60 interacts with YB-1 and affects its polysome association and subcellular localization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 385: 545–550 doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Stetler RA, Gan Y, Zhang W, Liou AK, Gao Y, et al. (2010) Heat shock proteins: cellular and molecular mechanisms in the central nervous system. Prog Neurobiol 92: 184–211 doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Goh YC, Yap CT, Huang BH, Cronshaw AD, Leung BP, et al. (2011) Heat-shock protein 60 translocates to the surface of apoptotic cells and differentiated megakaryocytes and stimulates phagocytosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 68: 1581–1592 doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0534-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tanaka KJ, Matsumoto K, Tsujimoto M, Nishikata T (2004) CiYB1 is a major component of storage mRNPs in ascidian oocytes: implications in translational regulation of localized mRNAs. Dev Biol 272: 217–230 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mirande M, Le Corre D, Louvard D, Reggio H, Pailliez JP, et al. (1985) Association of an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex and of phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase with the cytoskeletal framework fraction from mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res 156: 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Melan MA, Sluder G (1992) Redistribution and differential extraction of soluble proteins in permeabilized cultured cells. Implications for immunofluorescence microscopy. J Cell Sci 101 (Pt 4) 731–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hughes A, Jones L (2011) Huntingtin localisation studies - a technical review. PLoS Curr 3 doi:10.1371/currents.RRN1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Purification of anti-peptide antibody PMF-C13 on PmMRF fusion protein. 15 ml crude rabbit serum was clarified by centrifugation and loaded onto an affigel affinity column coupled to the fusion protein encoded by the “PMF547” construct containing 547 of the 562 amino acids comprising full length PmMRF (see Fig. 3). (A) The blue line indicates amount of protein (OD260) which has passed through the BioLogic HPLC sensor during loading, washes, and acid elution. (B) Representative fractions were migrated by SDS-PAGE and stained with coomassie blue. Arrows indicate purified antibody heavy chain which has been bound to and eluted from the PmMRF fusion protein column. When an identical aliquot of antiserum was loaded onto a similar column coupled to the fusion protein encoded by the “PMF429” construct which contains 429 amino acids of PmMRF and lacks the immunogenic peptide sequence (see Fig. 3), no antibody was retained or eluted.

(TIF)

Amino acid sequences of proteins recognized by antibody NN18. (A) NF-M, the antigen the NN18 monoclonal antibody was originally raised against (porcine neurofilament medium, XP_001925857.1), is a protein of 934 amino acids and molecular weight 160 kD. (B) p58 is ATP synthase alpha subunit, the protein recognized by NN18 in ascidian eggs. Ciona intestinalis ATP synthase alpha (Genbank accession number AB071977, gene model KH.C10.579 on Ciona genome browser http://hoya.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp/cgi-bin/gbrowse/kh/) [1] is a protein of 554 amino acids with calculated molecular weight 59.97 kD. Phallusia mammillata ATP synthase alpha (compiled by manual assembly of unpublished EST data on the bioinformatics server at Villefranche) is a protein of 556 amino acids and calculated molecular weight 60.58 kD. (C) Alignment of the complete sequences of ATP synthase alpha-subunit from Homo sapiens (NP_001001937), Bos taurus (NP_777109), Xenopus laevis (NP_001080447), Drosophila melanogaster (NP_726243), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (NP_009453), Escherichia coli (NP_418190), Ciona intestinalis (KH.C10.579.v1.A.SL1-1). “Cloning/NN18” is the complete sequence of the cDNA clone obtained by immunoscreening a Ciona expression library with NN18. “Immunoprecipitation/NN18” and “Mitochondrial Targeting Signal” are as described in Fig. 2. The ATP binding (GDRQTGKT) and ATPase (PAINVGLSVS) sequences are also indicated.

(TIF)

Amino acid sequences of the 2 proteins recognized by antibody PMF-C13. (A) The protein purified in Fig. 5 was subjected to tandem MS/MS sequencing, and resultant peptides compared to both Ciona and Phallusia gene model predictions. The 4 aligned peptides showed a match to the same protein HSP60, with a higher percentage of sequence identity (shaded) to Phallusia mammillata, the species from which p63 was isolated, than to Ciona. Ciona HSP60 (gene model KH.C6.85 on Ciona genome browser http://ghost.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp/SearchGenome kh.html [1] is a protein of 573 amino acids with theoretical molecular weight 61.4 kD and isoelectric point 5.36. Phallusia HSP60 is a protein of 577 amino acids with theoretical molecular weight 61.9 kD and isoelectric point 5.40. The PmHSP60 sequence was compiled by manual assembly of unpublished Phallusia EST data on the bioinformatics server “Octopus” at Villefranche. This is a first demonstration that the well-developed Ciona proteomics database [2] can be used to identify proteins from the related species Phallusia mammillata. (B) PmMRF (MRF for Myogenic Regulatory Factor) is the Phallusia mammillata homolog of MyoD; the 13 amino acid C-terminal peptide used as antigen is highlighted. PmMRF (accession number HQ287931) is a protein of 562 amino acids with theoretical molecular weight 62.1 kD and isoelectric point 5.02. (C) The short highlighted sequences are regions of ascidian HSP60 with at least 3 consecutive amino acids identical to the immunogenic peptide.

(TIF)

Posterior region of Phallusia embryos stained with antibodies NN18 (red) and PMF-C13 (green). (A) Muscle precursor cells in 64 cell stage embryo, 4 hours after fertilization. n: nucleus. (B) muscle cells in a portion of the tadpole tail, which is formed 18 hours after fertilization. Non-myoplasm mitochondria which are outside of muscle lineage (arrows) are labeled as well as myoplasm mitochondria. Scale bars are 10 microns.

(TIF)

Spatial and temporal expression pattern of CiATPsynthase mRNA. (A) RT-PCR using primers specific for ATP synthase alpha or for tubulin control. (B) Whole mount in situ hybridization of embryos fixed at the indicated times in development. CiATPsyn transcript accumulates during oogenesis and is evenly distributed in the unfertilized egg. During cleavage stages the amount of CiATPsyn message decreases and is hardly detectable in neurula and later stages. Scale bars are 50 microns.

(TIF)

(DOCX)