Abstract

Caspases comprise a family of dimeric cysteine proteases that control apoptotic programmed cell death and are therefore critical in both organismal development and disease. Specific inhibition of individual caspases has been repeatedly attempted, but has not yet been attained. Caspase-9 is an upstream or initiator caspase that is regulated differently from all other caspases, as interaction with natural inhibitor XIAP-BIR3 occurs at the dimer interface maintaining caspase-9 in an inactive monomeric state. One route to caspase-9-specific inhibition is to mimic this interaction, which has been localized to the α5 helix of XIAP-BIR3. We have developed three types of stabilized peptides derived from the α5 helix, using incorporation of amino-isobutyric acid, the avian pancreatic polypeptide-scaffold or aliphatic staples. The stabilized peptides are helical in solution and achieve up to 32 µM inhibition, indicating that this allosteric site at the caspase-9 dimerization interface is regulatable with low-molecular weight synthetic ligands and is thus a druggable site. The most potent peptides against caspase-9 activity are the avian pancreatic polypeptide-scaffolded peptides. Other caspases, which are not regulated by dimerization, should not be inactivated by these peptides. Given that all of the peptides attain helical structures but cannot recapitulate the high-affinity inhibition of the intact BIR3 domain, it has become clear that interactions of caspase-9 with the BIR3 exosite are essential for high-affinity binding. These results explain why the full XIAP-BIR3 domain is required for maximal inhibition and suggest a path forward for achieving allosteric inhibition at the dimerization interface using peptides or small molecules.

Keywords: apoptosis, protease, inhibitors of apoptosis proteins IAP

Introduction

The apoptotic process of programmed cell death has been well studied for its involvement in development in all multi-cellular organisms as well as for its roles in conditions including cancer, heart attack, stroke, Alzheimer's and Huntington diseases. Irregularities in apoptosis may contribute to up to 50% of all diseases in which there are no suitable therapies1, underscoring the need to both understand and control apoptosis. One promising approach to controlling apoptosis is through caspase regulation. The caspases are cysteine aspartate proteases known to propagate apoptosis through a cascade of cleavage reactions ultimately leading to the demise of the cell. Apoptotic caspases are typically classified into two groups, the initiator caspases, caspase-8 and -9, and the executioners, caspase-3, -6 and -7. Caspase-8 is activated in response to upstream signals, which are transmitted to caspase-8 by the DISC complex2–4 while caspase-9 is activated by association with the apoptosome5–7. Once activated, caspase-8 and -9 further propagate the apoptotic cascade by cleaving and thus activating the executioner caspases, caspase-3, -6, and -78–11. The executioner caspases are responsible for cleaving specific intracellular targets, ultimately resulting in cell death. Due to its central role in initiating and propagating apoptosis and it’s unique regulatory mechanism12, we have focused on controlling the apoptosis initiator, caspase-9.

Caspase-9 is synthesized as a three-domain polypeptide, which is able to form homodimers. Structurally, caspase-9 consists of three domains. A prodomain, categorized as a Caspase Activation and Recruitment Domain (CARD), a large subunit, which contains the catalytic Cys-His dyad, and the small subunit which comprises the main portion of the dimer interface13. The zymogen caspase-9 has very low activity as a monomer. Activity increases upon dimerization13 and increases even more profoundly upon interaction with the apoptosome 5–7. The apoptosome is a heptameric complex formed from association of Apaf-1 and cytochrome c in an ATP dependent process10, 14, 15. The uncleaved zymogen form of caspase-9 is recruited to the apoptosome by binding of its CARD domain to the Apaf-1 CARD domain. The oligomeric state of caspase-9 bound to the apoptosome has been extensively debated. Evidence is emerging from high-resolution cryo electron microscopy that caspase-9 monomers are activated while bound to the apoptosome16. Caspase-9 does not require intersubunit cleavage for activation. However, when bound to the apoptosome, caspase-9 is processed at Asp315, resulting in a CARD-large subunit portion of the enzyme and a small subunit beginning with the N-terminal sequence of ATPF. Proteolytic removal of the CARD domain from the large subunit, which results in decreased activity, has also been observed. Processed caspase-9 can be displaced from the apoptosome by additional molecules of procaspase-917, resulting in release of cleaved caspase-9, which can form active dimers. As a cleaved dimer, the L2 loop from one half of the dimer is able to interact with the L2` loop from the other half in the presence of substrate, similarly to other caspases13. In this state, the protein is catalytically competent to process substrate. Like other caspases, caspase-9 recognizes its substrates and cleaves after specific aspartic acid residues.

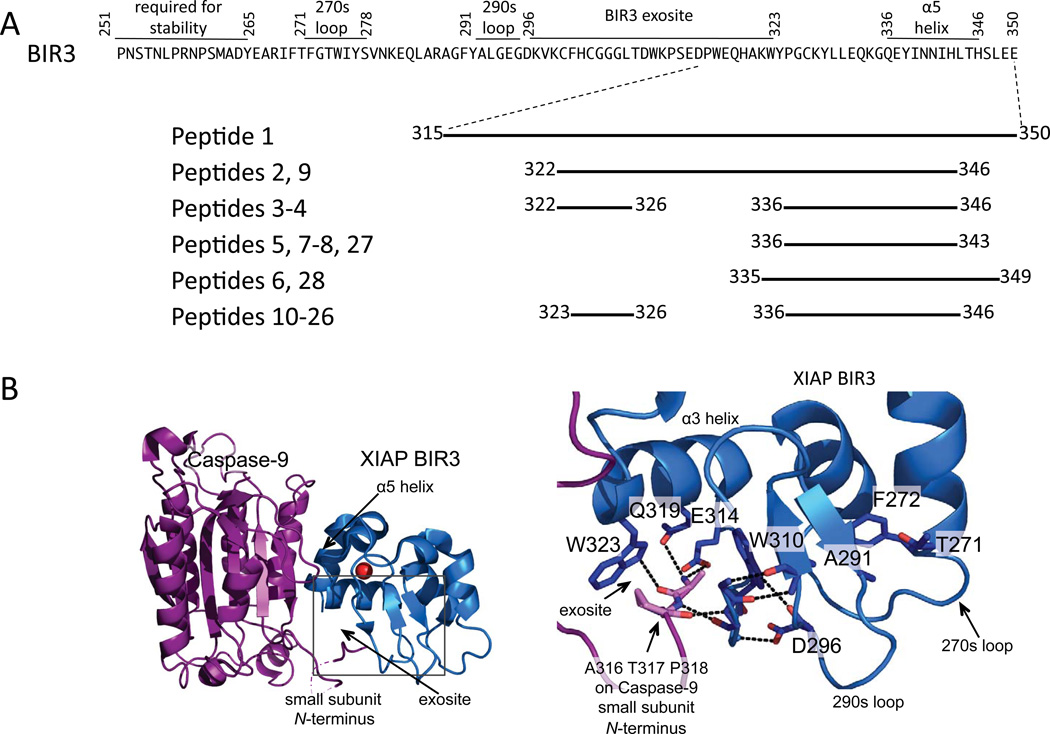

Once the caspase cascade is activated, apoptosis rapidly ensues. Treating diseases in which apoptosis is activated requires specific apoptotic caspase inhibitors. A naturally occurring family of caspase inhibitors, the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) proteins, show promise as models for caspase-specific inhibition. Caspase-9 is inhibited by the x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) in a manner that is distinct from the inhibition of other apoptotic caspases, including caspase-3 and -7. XIAP comprises three baculovirus inhibitory repeats (BIR). The linker between BIR1 and BIR2 binds to the active sites of caspase-3 and -7 dimers, blocking access to substrate and thereby inhibiting these caspases. The third domain of XIAP, BIR3, docks at the dimer interface of caspase-9 holding capase-9 in an inactive monomeric state. The most critical interactions occur between the α5 helix in BIR3 and the β8 strand of caspase-9 (Figure 1A). In addition, the N-terminus of the caspase-9 small subunit binds to an exosite on the BIR3 domain. Critical interactions within these two regions of the BIR3 domain have been highlighted as essential for BIR3’s interactions with caspase-9 (Figure 1B) and its inhibitory properties12, 18, 19. Many of these interactions are hydrogen bonds and salt bridges between the α5 helix of BIR3 and caspase-9, often BIR3 side chains interacting with caspase-9 backbone atoms. In addition, some hydrophobic interactions are critical. For example, mutations of both polar H343 and hydrophobic L344 in the α5 helix of BIR3 result in a complete loss of its inhibitory properties12, 19. Substitution of these two residues, within similar but non-functional IAP’s, such as cIAP1 and ML-IAP, restored caspase-9 inhibition enforcing the idea of the α5 helix as a main component in the BIR3 inhibitory mechanism20, 21. Another region of BIR, comprised of the amino acid sequence WYPG (residues 323 to 326), also improved the inhibitory properties when substituted in other IAP’s, suggesting that this region is also important for the interaction. Although these key regions are localized to the first three helices of BIR3, truncation of BIR3’s N-terminal residues 245–261 resulted in an extremely unstable protein with low potency for caspase-9 inhibition22. Additionally, the C-terminal truncation, BIR3 residues 348–356, had no effect on protein stability. Potency for caspase-9 was increased only in the presence of the N-terminal region suggesting that stabilization of the C-terminal region of BIR3 may be required for its inhibitory properties22. This unique mechanism of BIR3 inhibition of caspase-9 should enable development of caspase-9 specific inhibitors if the α5 helix can be sufficiently stabilized.

Figure 1.

Interactions required for inhibition of caspase-9 clustered in the α5 helix are recapitulated in synthetic peptide inhibitors. (A) Structure of a caspase-9 monomer (purple) bound to XIAP-BIR3 (blue) observed in PDB 1NW9 (upper panel). A structural zinc (red sphere) is observed in XIAP-BIR3. The exosite is marked with a circle. The boxed region is highlighted in the lower panel. Hydrogen bonds (black dotted lines) between caspase-9 monomer and the α5 helix from XIAP-BIR3 provides recognition specificity to the complex. These interactions are recapitulated in the native peptides. (B) Specific interactions observed in the structure of caspase-9 bound to XIAP-BIR3 and those present in the three classes of designs are listed. (C) Modeled interactions of designed peptides based on an aPP scaffold (yellow) were designed to mimic the interactions between caspase-9 (purple) and the α5 helix. The polyproline helix labeled in the upper panel, has been removed from the lower panel for clarity. (D) Modeled interactions of α5-derived peptides stabilized by aliphatic staples (green) with caspase-9 (purple). Figures were drawn with PyMol73.

To date, the vast majority of work towards caspase-specific inhibition has focused on creating small-molecule and peptide-based active-site inhibitors. Achieving specificity at the active site has been difficult because all caspases have a stringent requirement for binding aspartic acids in the S1 pocket. This means that both apoptotic and inflammatory caspases are subject to inhibition by very similar inhibitors. Most caspase inhibitors have consisted of a peptide or peptidomimetic with an acid functionality to bind in the S1 pocket of the active site and some kind of cysteine-reactive warhead. Utilizing the BIR3 mechanism of inhibition is promising in that it is unique to caspase-9 and should avoid inhibition of other caspases. Here we present peptide-based inhibitors that mimic BIR3 inhibition of caspase-9.

Peptide mimics as surrogates for large protein-protein interactions have been extensively pursued. In one early example, an entire interface of the vascular endothelial growth factor was reduced to a 20-amino acid peptide which could then be optimized via phage display to achieve the needed binding affinity23. The atrial natriuretic peptide was similarly minimized to half the original size using rational design and phage display and still retained binding ability24. Some proteins, like the β-adrenergic receptor, can be controlled with small, unstructured peptides in which the principal requirement for binding is an available amine. On the other hand, successful mimics of the vast majority of protein-protein interactions attempted to date have required a structured peptide to mimic the native protein interactions. Thus a number of approaches have been developed to stabilize fragments of proteins in their native structure. For helices the prominent methods are to initiate or stabilize helix formation or use small scaffolding proteins. Some approaches have targeted naturally occurring capping motifs or side-chain cross-linking methods such as disulfide bonds, lactam bridges and metal mediated bridges25–34. Main chain conformational restrictions using unnatural α-methylated amino acids, such as aminoisobutyric acid (Aib), have also been explored. The placement of Aib in peptides restricts the conformation of the adjacent peptide bonds, promoting proper torsion angles for α-helical formation35. More recently, all hydrocarbon cross-linking side chains, sometimes called peptide staples, have been introduced to maintain helical conformations of small peptides36. These hydrocarbon staples have been shown to improve helicity as well as cell permeability of peptides derived from a BID BH3 helix37, the NOTCH transcription factor complex38, and a p53 helix39. In this ‘stapling’ method, unnatural α-methylated amino acids containing olefinic side-chains of the appropriate length, are placed at the i and i+4 or i and i+7 positions of the helix to be stabilized. These positions are selected because one turn of an α-helix is 3.6 residues in length thus the staples would span one or two turns of the helix. Cyclization of these amino acids is performed through an olefin metathesis reaction, facilitated by Grubbs catalyst, thus locking the amino acids into a stapled formation, reinforcing nucleation of the α-helix40. Others have enforced main-chain interactions through hydrogen bond surrogates which places a covalent link between the backbone of the i and i+4 positions utilizing a similar olefin metathesis reaction41. An orthogonal approach utilizing stabilized scaffolds called miniature proteins has also proven useful in helix stabilization42, 43. The critical amino acids for the protein-protein interface are grafted onto a stable helical scaffold in the appropriate register to obtain the proper amino acid orientation for the interaction. For example, the scaffold of avian pancreatic polypeptide (aPP) has been used to design Bcl-2 based inhibitors44, p53-hDM2 interaction inhibitors45, herpes virus protease dimer disrupters46, as well as mimicking protein-DNA interactions47–49. More recently, Peptide YY has also been used as a miniature protein scaffold43.

Upon analysis of the caspase-9/BIR3 complex and understanding the successes of stabilized helices, our approach to caspase-9 inhibition is two-fold: First, we aim to investigate which regions of the α5 helix of BIR3 are essential to achieve BIR3-like inhibition. Second, we aim to utilize the α5 helix region of BIR3 in order to achieve caspase-9 inhibition via small α-helical peptides43.

Results

To achieve inhibition of caspase-9 utilizing the interactions observed between the BIR3 α5 helix and the caspase-9 β8 strand (Figure 1A), we predicted that some type of helix stabilization or helical scaffold would be required. We have designed and synthesized three different classes of α5-stabilized peptides and tested them for their ability to inhibit caspase-9. These three classes: native and Aib-stabilized, aPP-scaffolded, and aliphatic stapled peptides take three entirely different approaches to helix stabilization, but each of them recapitulates the most important interactions from the α5 helix (Figure 1B). The stabilized peptides are markedly more helical and are better inhibitors than the analogous native, non-stabilized peptides.

Native and Aib-Stabilized Peptides

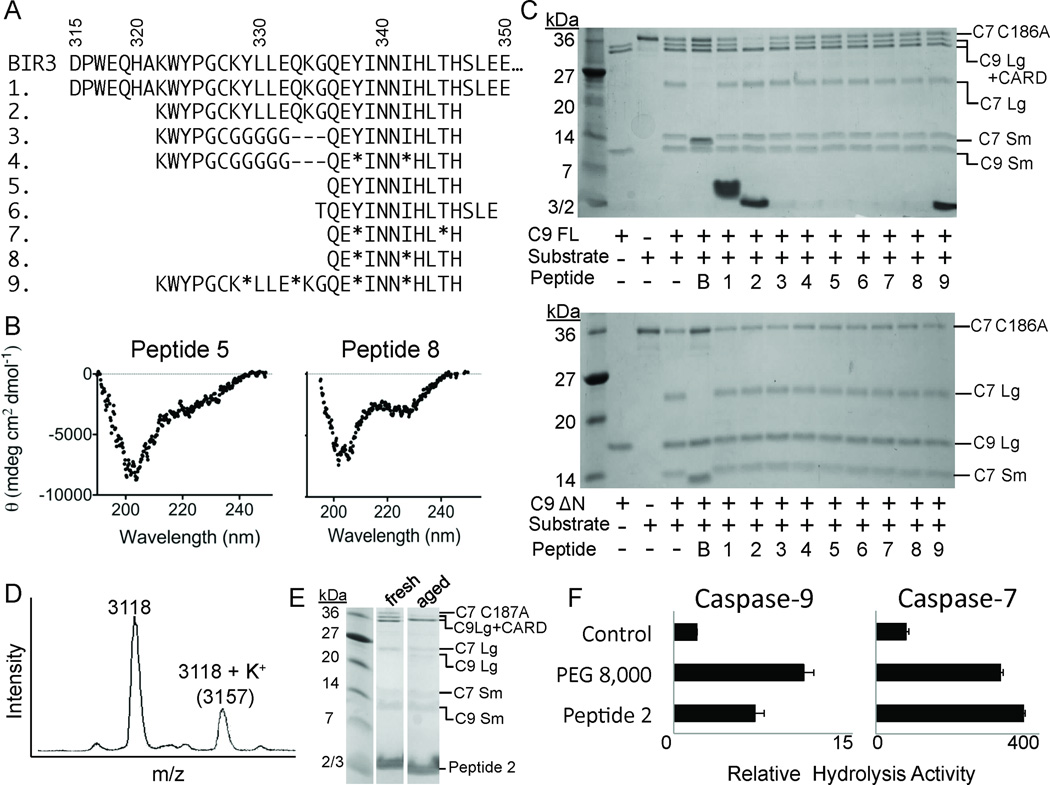

Our first approach was to isolate native sequences from the BIR3 α5 helix (Figure 1A, 2). In some sequences, aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) was inserted at various positions to stabilize the helical conformation of the peptide. Aib is an α-branched amino acid analogous to the naturally-occurring amino acid alanine, but derivatized at the α- carbon with two equivalent methyl groups. The presence of two methyl groups on the α-carbon locks adjacent peptide bonds into an α-helical confirmation by supporting helical dihedral angles, and thus has been widely used to stabilize helical peptides35, 50–52. We designed peptides ranging from 11 to 35 amino acids in length. The longest, Peptide 1, composed of BIR3 residues 315–350, was designed to contain the α3-α5 helices (Figure 2A). The α3 helix forms part of the exosite; the α4 helix orients the WYPG region and the α5 helix contains the major elements for recognition of caspase-9. Peptides 2–4 are 21–25 amino acids long and contain all of the core interactions from α3, α4 and α5 helices. Peptide 9 is similar to Peptide 2 but is stabilized in four non-interacting positions by Aib. Peptide 5 is 11 residues long and derived directly from the α5 helix. In Peptide 6 we added helix capping residues at the N- and C-termini. Peptides 7 and 8 are stabilized at non-interacting position by Aib. The circular dichroism (CD) spectra suggested that the native peptides were less helical than the Aib-stabilized peptides (Figure 2B), predicting that the Aib-containing peptides were closer to their target structures than the peptides constructed solely from native amino acids derived directly from BIR3.

Figure 2.

Properties of native and Aib-stabilized peptides. (A) Sequences of the α5 region of XIAP-BIR3 (BIR3) and peptides 1–9. * represents aminoisobutyric acid (Aib). (B) CD spectra of the native Peptide 5 and the Aib-stabilized Peptide 8 demonstrate that the presence of Aib increases the helicity of the peptides. (C) Native and Aib-stabilized peptides (1–9) show some inhibition of full-length caspase-9 (C9 FL) or the N-terminal CARD-domain deleted caspase-9 (C9 ΔN) to cleave a natural caspase-9 substrate, the caspase-7 zymogen (C7 C186A) to the caspase-7 large (C7 Lg) and small (C7 Sm) subunits in an in vitro cleavage assay monitored by gel mobility. B; Purified BIR3. (D) Peptide 2 (MW 3118) is chemically stable even after a 3-week, 4°C incubation. (E) Aged Peptide 2 but not freshly rehydrated Peptide 2 inhibits caspase-9. (F) 3-week aged Peptide 2 non-specifically activates both caspase-9 and caspase-7 in a manner similar to the polymeric crowding agent PEG 8,000.

Both the native and Aib-containing peptides were tested for their ability to inhibit caspase-9. Caspase-9 is most active prior to catalytic removal of the 16 kD caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD). The CARD is responsible for associating caspase-9 with the apoptosome. However, in the absence of the apoptosome, the location of the CARD remains uncharacterized. Due to the size of the CARD and its ability to enhance caspase-9’s basal catalytic activity through an as yet unknown mechanism, we reasoned that the peptide inhibitors may show a preference for interaction with either full-length caspase-9 (C9FL: containing the CARD, large and small subunits) due to positive interactions with the CARD or a preference for ΔN caspase-9 (C9ΔN: containing only the large and small subunits) due to negative interactions with the CARD. Finding no difference in the ability of the inhibitors to influence full-length or ΔN caspase-9 would suggest that the peptides do not interact in any way with CARD. We tested both C9FL and C9ΔN (Figure 2C) in an in vitro gel-based caspase-9 assay, which monitors cleavage of caspase-7 (substrate) (Figure 2, Table 1) and in a fluorescent peptide cleavage assay. In both assays we observed no difference between the two enzymes in the ability to be inhibited by the peptides (Table 1). Peptide concentrations were calculated by absorbance at 280 nm or by using densitometry measurements on the purified peptides analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Using these two orthogonal approaches we found that the error in the determination of peptide concentrations is no more than 2-fold.

Table 1.

Overall Inhibition of Caspase-9 Full Length by Peptides

| Peptide | % Inhibitiona (66.7 µM peptide) |

IC50 appb (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | >100 |

| 2 | 0 | >100 |

| 3 | 0 | >100 |

| 4 | 1.1± 2.4 | >100 |

| 5 | 0.45 ± 1.1 | >100 |

| 6 | 0 | >100 |

| 7 | 6.3 ± 11 | >100 |

| 8 | 13 ± 16 | >100 |

| 9 | 15 ± 14 | >100 |

| 10 | n.d. | 64 ± 13 |

| 11 | 24 ± 13 | 32 ± 11 |

| 12 | 8 ± 11 | >50 |

| 13 | 0 | >100 |

| 14 | 13 ± 7.1 | 50 ± 3.8 |

| 15 | 0 | >100 |

| 16 | 6.2 ± 2.6 | >100 |

| 17 | 22 ± 23 | 50 ± 5.1 |

| 18 | 17 ± 9.6 | >100 |

| 19 | 24 ± 8.4 | 80 ± 4.8 |

| 20 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | >100 |

| 21 | 2.9 ± 3 | >100 |

| 22 | 0 | >100 |

| 23 | 0 | >100 |

| 24 | 1.8 ± 2.6 | >100 |

| 25 | 2.5 ± 3.5 | >100 |

| 26 | 8.9 ± 12 | >100 |

| 27 | 0 | > 100 |

| 28 | 0 | >100 |

Proteolytic cleavage gel-based caspase-9 activity assay which monitors cleavage of natural substrate, caspase-7. Percent inhibition was calculated using Gene Tools (SynGene by producing a standard curve from densiometry values for processed and unprocessed substrate, (caspase-7 C186A).

Fluorescence-based caspase-9 activity assays which monitor cleavage of fluorogenic substrate (LEHD-AFC).

For peptides in this study an apparent IC50 (IC50 app) was fit from an inhibitor titration at a fixed substrate concentration. This was compared to the amount of inhibition observed in a gel-based assay where the peptide concentration was fixed at 66.7 µM, a concentration in excess of the best IC50 app observed (Table 1). The full BIR3 domain, with a reported Ki of 10–20 nM (18, 20, 52) is an effective inhibitor in both the fluorescence assay, which uses a small fluorogenic peptide substrate mimic and in the gel based assay, which uses a natural substrate. In both activity assay formats, we observed moderate inhibition by many of the peptides. Other investigators have traditionally relied on gel-based assays to assess caspase-9 inhibition and activation. This is likely due to the greater reproducibly and lowered requirements for peptide consumption in the gel-based assay, which we have also observed. The inhibition that we observe in the two assays formats, agrees qualitatively for the peptides we have tested. All of the native and Aib-stabilized peptides showed an IC50 app of >100 µM.

Peptide 2 routinely activated caspase-9 in samples of aged peptide (incubated for three weeks at 4°C). Initially we were intrigued by the ability of aged Peptide 2 to activate caspase-9. We found that samples of aged Peptide 2 were of the same molecular weight as the freshly diluted Peptide 2 immediately following synthesis, confirming that there were no chemical modifications upon aging (Figure 2D). Freshly diluted Peptide 2 samples were incapable of activation, whereas the incubated peptides were activating (Figure 2E). Although aged Peptide 2 samples were capable of activating caspase-9 four-fold over basal rates of hydrolysis of the fluorogenic LEHD-AFC peptide, they were similarly capable of activating other caspases, including caspase-7 (Figure 2F). Caspase active sites are highly mobile and are thus responsive to molecular crowding agents, including polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG)53. The type of activation from aged Peptide 2 is similar to that observed by PEG 8000 (Figure 2F), suggesting that aggregation occurring over a three-week aging process at 4°C was responsible for this level of activation.

aPP-Scaffolded Peptides

Our second approach for developing stabilized α5 helices used the avian pancreatic polypeptide (aPP) scaffold (Figure 3). aPP is a 36-amino acid peptide derived from the pancreas of turkey. Its native role is in the feedback inhibition loop halting pancreatic secretion after a meal (reviewed in54). In the crystal structure, aPP is composed of a standard alpha helix flanked by a polyproline helix (Figure 1C, 3B)55, 56. The interaction between these two helices provides stability for the folded conformation.

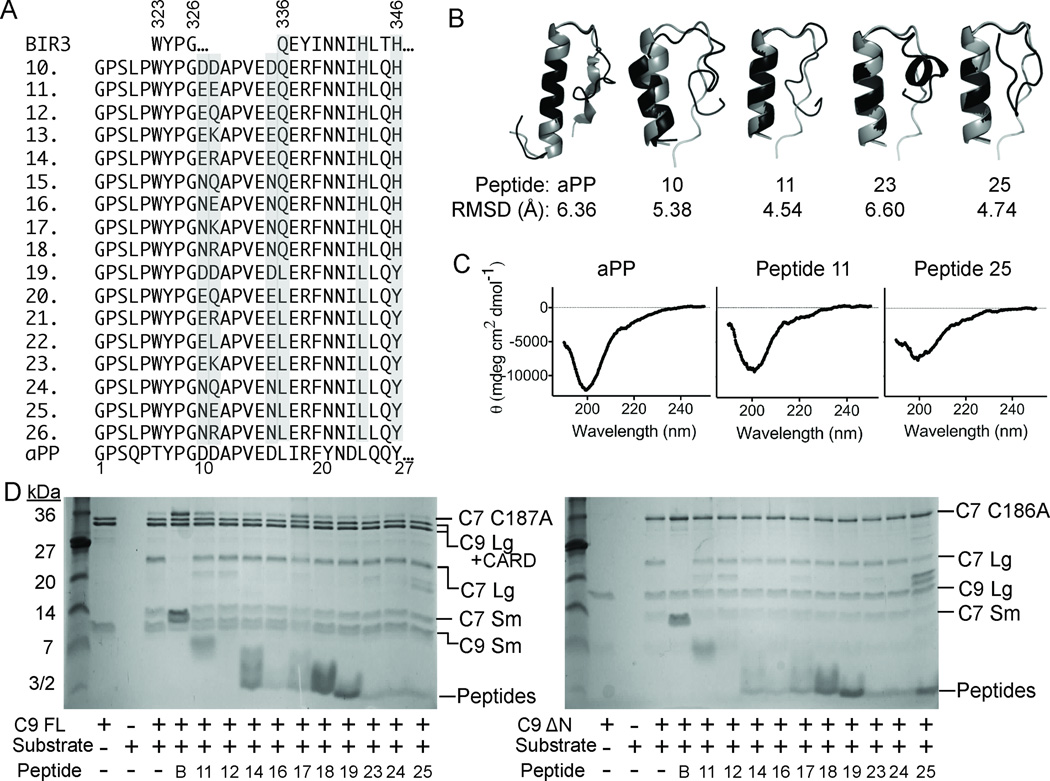

Figure 3.

Properties of aPP-scaffolded peptides. (A) Sequences of native BIR3, derivative Peptides 10–26 and native aPP, in which critical residues from the α5 region of XIAP-BIR3 have been inserted into the aPP scaffold. Highly varied positions are shaded. (B) aPP and peptide structures predicted computationally (black) by Rosetta 58, 59 are superimposed on the known structure of aPP (gray). RMSD for backbone atoms suggests the majority of the designed aPP-based peptides should adopt a helical conformation in aqueous solution. (C) The CD spectra of the aPP and Peptides 11 and 25 indicate that the structure of the designed peptides is very similar to that of native aPP in solution. (D) aPP-based peptides show some inhibition of full-length caspase-9 (C9 FL) or the N-terminal CARD-domain deleted caspase-9 (C9 ΔN) to cleave a natural caspase-9 substrate, the caspase-7 zymogen (C7 C186A) to the caspase-7 large (C7 Lg) and small (C7 Sm) subunits in an in vitro cleavage assay monitored by gel mobility.

aPP is amenable to substitution on many faces42, 49 and can withstand a C-terminal truncation56 without negatively effecting the structure or function. α5-mimicing peptides were designed by structurally aligning the α-helical region of aPP with the α5 helix in the BIR3-Caspase-9 complex. aPP was aligned principally by superposition of the Cα positions and tested for maximum overlap in all possible helical registers. We ultimately selected one register (Figure 1C, 3A) because it maximized overlap of productive interactions between naturally-occurring aPP amino acids and caspase-9, such as the WYPG amino acid region which was found to be critical in converting other IAP’s to inhibit caspase-920, 21, 46. In addition this orientation predicts no steric clashes between the aPP N-terminus, the polyproline helix, and caspase-9. Ultimately we chose to truncate aPP to prevent steric clash between the aPP C-terminus and caspase-9. To make Peptide 10, we grafted the critical BIR3 residues 323–6, 336–7 and 340–4 onto aPP at positions 17–18 and 21–25 (Figure 3A). We also grafted residues 323–326, which compose the sequence WYPG between the α3 and α4 helices of BIR3, at positions 6–9 of aPP. aPP positions 6–9 are in the polyproline helix and are designed to support the interactions of the WYPG region of BIR3 with caspase-9. In Peptides 11–14, we varied the identity of position 11 to enable novel interactions with the loop region in caspase-9 and changed all of the aspartates to glutamates. Caspases cleave exclusively following aspartate residues, so substitution of these residues was designed to limit their caspase substrate characteristic. In Peptides 15–18, the aspartates were substituted by asparagines to prevent caspase cleavage and position 11 was varied to introduce novel interactions. In Peptides 19–26, we systematically returned positions that had previously been shown to be important for the fold and stability of aPP to the identity in the native aPP sequence.

To produce this series of caspase-9 inhibitors, Peptides 10–26, we developed a novel expression system that allowed robust production and purification of aPP-based peptides57. The mass spectra of peptides 10–26 indicated that each of these peptides are produced accurately in bacteria and that the peptides could be purified to a very homogenous state using our methodology57. The conformation of these truncated versions of aPP were computationally predicted by Rosetta58, 59 to fold into a helical structure (Figure 3B). In all of our aPP scaffolded designs, additional interactions are created between Y7, D10 and D11 of aPP’s polyproline helix and the caspase-9 interface. Neither truncation of aPP nor the insertion of the α5-derived residues appears to have a substantial effect on the structure of aPP-derived peptides as the CD spectra of the designed peptides are very similar to the spectra of the aPP parent (Figure 3C). The spectra of aPP and the aPP-scaffolded peptides are dominated by the polyproline helix component with a negative peak at 198–206 nm60, 61 and are predicted to have 5% α-helical content62. Because the spectra of the aPP-scaffolded peptides are similar to the parent aPP scaffold structure, the aPP-based peptides were tested for their ability to inhibit full-length and ΔN caspase-9 in the gel based (Figure 3D) and fluorescent peptide cleavage assays (Table 1). Of this class, the best inhibitors were peptides 10, 11, 14, 17 and 19 with IC50 app of 64, 32, 50, 50 and 80 µM respectively. The majority of the aPP-based peptides had IC50 app greater than 100 µM. Our four best peptides 10, 11, 14, and 17 each contain all of the interacting residues that make up the BIR3 interface while Peptide 19 incorporates those residues important for the stability of the aPP scaffold. Exclusion of the critical BIR3 residues appears to be unfavorable for the peptides inhibitory properties as the best peptides retain the maximum number of BIR3 critical residues. Inhibition by peptide 19 is somewhat surprising as this design eliminates some of the critical BIR3 residues and yet retains inhibitory properties, potentially due to some additional active site competition by the three aspartates present in this peptide. Peptides 11, 14 and 17 are devoid of aspartate residues. This feature decreases the propensity of the peptides to interact with the caspase-9 substrate binding groove and thus increases the probability of interaction with the caspase-9 dimer interface. Interestingly, the only difference between peptides 10 and 11 is the substitution of three aspartates present in peptide 10 for three glutamates. Thus the improved potency of Peptide 11 over Peptide 10 could be related to differences in caspase-9-mediated cleavage. In addition, position eleven on the scaffold in Peptide 11, 14, and 17 contains a glutamate, arginine or lysine, respectively, at residue 11. These residues were designed to form an additional salt bridge with the caspase-9 interface (not present in the native BIR3 domain) thus enhancing their ability to inhibit caspase-9 activity. This appears to have been successful as these peptides have the best inhibition properties. Interestingly, the addition of a glutamine at position 11 did not show any favorable effects on the inhibitory properties of the peptides, suggesting that glutamate, arginine, and lysine can form specific interactions that are not possible for glutamine.

Aliphatic Stapled Peptides

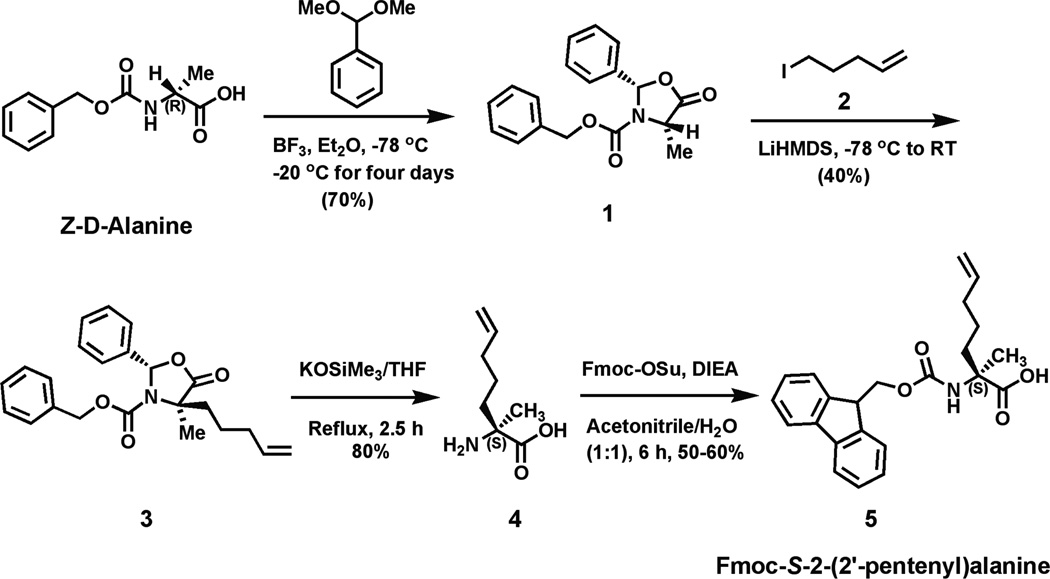

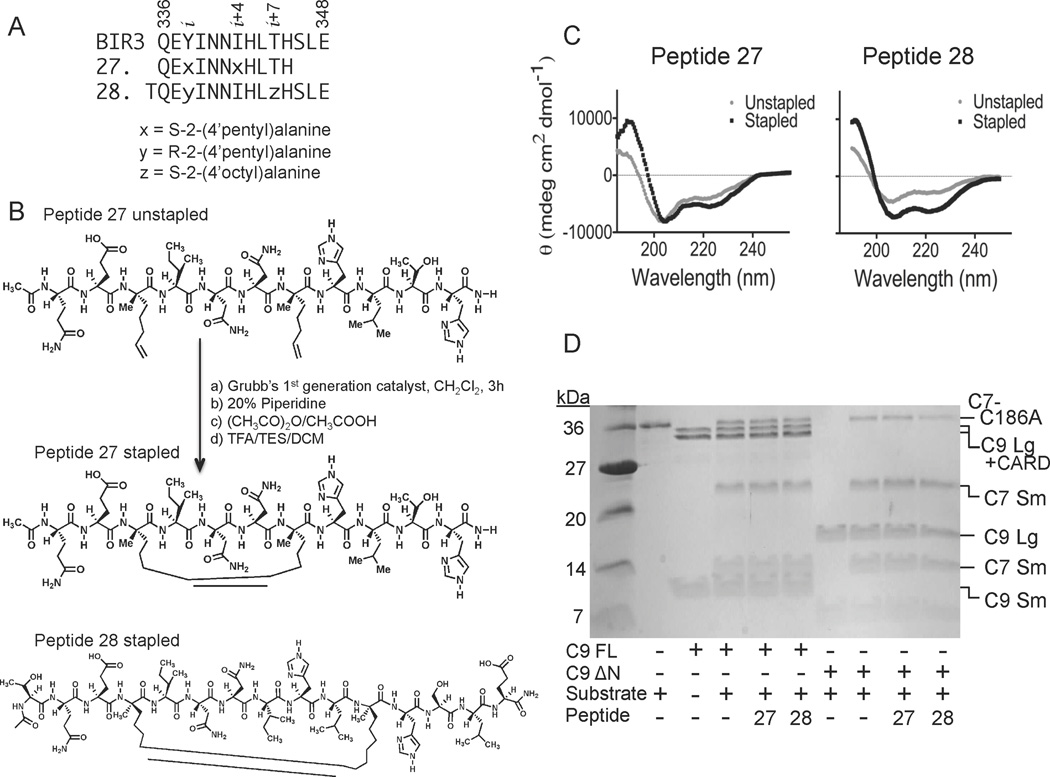

The third approach to achieve caspase-9 allosteric inhibition at the dimer interface was to incorporate aliphatic staples to stabilize short helices derived directly from the α5 helix in BIR3 (Figure 1D). Aliphatic staples have been used successfully to stabilize helices and increase cell permeability of the peptides in which they are incorporated37, 63. To synthesize the stapled peptides, we adapted the synthetic route reported by Seebach et.al.64–66 to synthesize three unnatural Fmoc-protected amino acids used in the stapling reactions (Figure 4). In this synthetic approach we used a mild organic base, potassium trimethyl-silanolate that could perform both the CBz deprotection and five-membered ring opening reactions in a single step to obtain the final α-α-disubstituted amino acids. This method is less hazardous than traditional two-step methods36, 67, which require the use of sodium in liquid ammonia for hydrogenolysis of the five-membered ring, followed by a reaction with TFA to deprotect the Boc group to obtain α-α-disubstituted amino acids. Our adapted method produced the non-native amino acids at yields comparable to the traditional published routes generally used to obtain the unnatural amino acids used in peptide stapling. We focused on two pairs of stapling peptides. Peptide 27 is 11 amino acids long and composed of residues 336 to 345 from the α5 helix of BIR3. In peptide 27 amino acids Y338 and I342 from BIR3, which point away from the caspase-9 dimer interface, were both replaced by S-2-(4’pentyl)alanine (Figure 5A). Catalysis of the ring closing metathesis forms an 8–carbon alkyl macrocyclic cross-link (Figure 5B). Peptide 28 is composed of an N-terminal threonine for helix capping of BIR3 residues 336–348. In Peptide 28 BIR3 residues Y338 and T345 were replaced by R-2-(4’pentyl) alanine and S-2-(4’octyl)alanine respectively. Threonine was added to the N-terminus of Peptide 28 because it has a higher helix capping propensity than the native residue, glycine (reviewed in68). The C-terminus was likewise extended because of the improved helical propensity of the residues SLE (reviewed in68). Ring closing metathesis results in an 11-carbon aliphatic linker (Figure 5B) which has been shown to be the optimal staple for i to i+7 stapling36. As predicted, both peptides appeared to be substantially more helical in aqueous solution following the ring closing metathesis reaction to generate the aliphatic staple than prior to closure of the staple (Figure 5C). Thus in both cases we can conclude that the peptides attain the designed helical structure. The stapled peptides were both tested against caspase-9 full-length or ΔN caspase-9 (Figure 5D), but did not show strong inhibition at concentrations below 100 µM in either assay format on either caspase-9 construct.

Figure 4.

Synthetic route for production of the (A) pentyl alanine amino acid used to generate the aliphatic peptide staples.

Figure 5.

Properties of aliphatically-stapled peptides. (A) Sequences of BIR3 and stapled Peptides 27 and 28. x, y and z represent the synthetic, non-native amino acids as listed. (B) Ring-closing metathesis reaction performed on the unstapled Peptide 27 to form the aliphatic stapled Peptide 27 with an 8-carbon macrocyclic linker. The structure of aliphatically stapled Peptide 28 contains an 11-carbon macrocyclic linker. (C) The CD spectra of Peptides 27 and 28 indicate a significant increase in the helicity following the formation of the aliphatic staple. (D) Stapled Peptides 27 and 28 show some inhibition of full-length caspase-9 (C9 FL) or the N-terminal CARD-domain deleted caspase-9 (C9 ΔN) to cleave a natural caspase-9 substrate, the caspase-7 zymogen (C7 C186A) to the caspase-7 large (C7 Lg) and small (C7 Sm) subunits in an in vitro cleavage assay monitored by gel mobility.

Discussion

All three classes of peptides are capable of attaining helical structures to present the appropriate amino acids to the caspase-9 dimer interface. The length and the type of scaffold did appear to have a tremendous influence on the potency of the peptides. The aPP-scaffolded peptides were more successful than the native, Aib-stabilized or stapled peptides. Our data suggest peptides composed of 15 amino acids or less in length such as Peptides 5–8 of the native and Aib stabilized class or Peptides 27–28 of the stapled peptides may be too short to have the requisite interaction for high-affinity binding to caspase-9. Models of these small peptides bound to caspase-9 bury 900Å2 of surface area in contrast to the 1700Å2 for models of the aPP-scaffolded peptides and the 2200Å2 interface found in the native BIR3-caspase-9 complex. It is possible that other non-critical residues found in the large interface potentially provide a hydrophobic interaction, which may be lacking in the short peptide sequences, thus decreasing their ability to efficiently inhibit caspase-9.

Peptides ranging in length from 11 to 39 amino acids have achieved high affinity binding utilizing the various stabilizing methods we have employed here38, 39, 45–48, 69–71. An efficient peptide inhibitor of the hdm2–p53 interaction was shown to improve potency based on additional helical constraints imposed by Aib where incorporation of four Aib residues into a 12 amino acid peptide was required69. Our peptides utilized two Aib residues for an 11 amino acid stretch, so perhaps a greater number of Aib residues could further improve binding properties. The aPP-scaffolded Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus protease (KSHV Pr) inhibiting peptide, which was 30 amino acids long, was also designed with a five amino acid C-terminal truncation and altered ten amino acids within the α-helical region of aPP. This peptide was successful at disruption of dimerization, however it required 200-fold molar excess of peptide in order to obtain 50% inhibition of protease activity46. Our best peptides were at least as effective. We observe 50% inhibition with an average of ~30-fold molar excess peptide. Additionally, a 13 amino acid stapled peptide co-activator mimic of the estrogen receptor was able to achieve high affinity binding. The authors noted however, that in these short peptides, the hydrocarbon staple can alter the binding geometry via its ability to interact with hydrophobic interfaces thus perturbing the desired interactions required for inhibition71. Thus, although our peptides were not as potent as the parent BIR3 domain, they are of similar efficacy as other stabilized peptides. Most importantly, these peptides demonstrate that the dimerization interface of caspase-9 can be targeted by small-molecular weight inhibitors, indicating that this is indeed a druggable site.

Based on spectroscopic data, it is clear that all three classes of peptides we designed and synthesized have been stabilized in more helical conformations by incorporation of Aib, aliphatic staples or by the aPP scaffold. Despite the measured increases in helicity in all classes of peptides, we have not been able to recapitulate the 10–20 nM interaction of BIR3 with caspase-919, 21, 72. This could be due to the fact that the peptides are not in the optimal helical conformation even with the stabilizing methods we employed or due to the absence of other interactions from the BIR3 domain that are essential for inhibitory function.

During the design process, consideration of critical residues, additional interface interactions, scaffold requirements, and fold led to production of some peptide inhibitors of caspase-9 in the micromolar range. The most potent inhibitors were all members of the aPP scaffolded class of peptides. This class provided the secondary structural requirements needed to mimic the α5 helix interactions, provided the additional interactions of the WYPG region of BIR3 as well as providing a larger surface area coverage, which the other peptide classes lack. Although native and Aib-stabilized Peptides 1–9 and the stapled Peptides 27–28 contain all of the critical contacts for interacting with caspase-9 through the α5 helix and were helical in solution, they were still not highly potent inhibitors. This suggests that the α5 helix alone is not sufficient for full inhibition of the intact BIR3 domain even when it is presented in a stable, helical structure. This observation suggests that the exosite of BIR3 (composed of residues 306–314) which binds the N-termini of the small subunit of caspase-9 provides additional, mainly hydrophobic interactions, required for high affinity inhibition (Figure 6A, B). Prior reports suggested that lack of stability explained the inability of truncations of the BIR3 domain to inhibit caspase-922. Together our data on stabilized α5 helices provide a model for why full length BIR3 is required for the interaction. Although the α5 helix has been shown to contain the most critical residues for recognizing caspase-9, the BIR3 exosite also appears to be essential. The BIR3 exosite is composed of residues 306–314. These residues do not fold into any regular element of secondary structure, but exist in an ordered loop. This loop is held in the appropriate conformation from behind by two other loops from the 270s and 290s region of BIR3 (Figure 6B). Furthermore, this region is stabilized via the N-terminal loop of BIR3 indicating the lack of this region leaves the exosite residues unordered. The exosite must interact with the very flexible N-terminus of the caspase-9 small subunit also called the L2’ loop. Because the exosite region does not adopt any regular secondary structure it is difficult to envision how to recapitulate the high-affinity BIR3:caspase-9 interaction with any smaller, contiguous region of BIR3. Thus, we now understand why full-length BIR3 is required for full-potency inhibition of caspase-9 via the dimer interface. Furthermore, these studies provide a roadmap for design of future BIR3-like small-molecule or peptide inhibitors in which peptide helicity and potency against other caspases can be rigorously quantified. High potency inhibitors that block caspase-9 inhibition by a BIR3-type mechanism must necessarily encompass all the critical interactions in the exosite as well those in the α5 helix.

Figure 6.

Full-length BIR3 is required for high-affinity caspase-9 inhibition. (A) Sequence of BIR3 and regions of BIR3 contained in the caspase-9 inhibitory peptides. (B) Interactions of caspase-9 monomer (purple) small subunit N-terminus (L2’ loop) with BIR3 (blue) exosite residues, which are contained within the box.

Materials and Methods

Caspase-9 Expression and Purification

The caspase-9 full-length gene (human sequence) construct in pET23b (Addgene) was transformed into the BL21 (DE3) T7 Express strain of E. coli (NEB). The cultures were grown in 2xYT media with ampicillin (100 mg/L, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C until they reached an optical density of 1.2. The temperature was reduced to 15°C and cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG (Anatrace) to express soluble 6xHis-tagged protein. Cells were harvested after 3 hrs to obtain single site processing. Cell pellets stored at −20°C were freeze-thawed and lysed in a microfluidizer (Microfluidics, Inc.) in 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM imidazole. Lysed cells were centrifuged at 17K rpm to remove cellular debris. The filtered supernatant was loaded onto a 5 ml HiTrap Ni-affinity column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM imidazole until base lined. The protein was eluted using a 2–100mM imidazole gradient over the course of 270 mL. The eluted fractions containing protein of the expected molecular weight and composition were diluted by 10-fold into 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 10 mM DTT buffer to reduce the salt concentration. This protein sample was loaded onto a 5 ml Macro-Prep High Q column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The column was developed with a linear NaCl gradient and eluted in 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM DTT buffer. The eluted protein was stored in −80°C in the above buffer conditions. The identity of the purified caspase-9 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and ESI-MS to confirm mass and purity.

Caspase-9ΔCARD was expressed from a two plasmid expression system 53, 74, 75. Two separate constructs, one encoding the large subunit, residues 140–305 and the other encoding the small subunit, residues 331–416, both in the pRSET plasmid, were separately transformed into the BL21 (DE3) T7 Express strain of E. coli (NEB). The recombinant large and small subunits were individually expressed as inclusion bodies. Cultures were grown in 2xYT media with ampicillin (100 mg/L, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C until they reached an optical density of 0.6. Protein expression was induced with 0.2 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested after 3 hrs at 37°C. Cell pellets stored at −20°C were freeze-thawed and lysed in a microfluidizer (Microfluidics, Inc.) in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0 and 1 mM EDTA. Inclusion body pellets were washed twice in 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 M NaCl, 2% Triton, and 1 M urea, twice in 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and finally resuspended in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. Caspase-9 large and small subunit proteins in guanidine hydrochloride were combined in a ratio of 1:2, large:small subunits, and rapidly diluted dropwise into refolding buffer composed of 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10% sucrose,0.1% CHAPS, 0.15 M NaCl, and 10 mM DTT, allowed to stir for one hour at room temperature and then dialyzed four times against 10 mM Tris pH 8.5, 10 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM EDTA buffer at 4°C. The dialyzed protein was spun for 15 minutes at 10,000 rpm to remove precipitate and then purified using a HiTrap Q HP ion exchange column (GE Healthcare) with a linear gradient from 0 to 250 mM NaCl in 20 mM Tris buffer pH 8.5, with 10 mM DTT. Protein eluted in 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM DTT buffer was stored in −80°C. The identity of the purified caspase-9ΔCARD was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and ESI-MS to confirm mass and purity.

Caspase-7 WT and Caspase-7 C186A Expression and Purification

The caspase-7 full-length human gene in the pET23b vector or the caspase-7 C186A variant (zymogen), made by Quikchange mutagenesis (Stratagene) of the human caspase-7 gene in pET23b (gift of Guy Salvesen 76) were transformed into BL21 (DE3) T7 Express strain of E. Coli. Induction of caspase-7 was at 18°C for 18 hrs. These proteins were purified as described previously for caspase-7 77. The eluted proteins were stored in −80°C in the buffer in which they were eluted. The identity of purified caspase-7 was assessed by SDS-PAGE and ESI-MS to confirm mass and purity.

Peptide Production

Peptides 1–9 were synthetically produced by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). The aPP scaffolded peptides 10–26 were designed and purified using methods previously described 57. Unnatural amino acids for Peptides 27–28 were synthesized by the following reactions:

Synthesis of N-Fmoc-S-2-(2’-pentyl)alanine (5)

(2S,4S)-2-Phenyl-3-(carbobenzyloxy)-4-methyloxazolidin-5-one(2S,4S), (1)

To a stirred solution of Z-D-Alanine (0.4 g, 1.8 mmol) and benzaldehyde dimethyl acetal (0.4 ml, 2.61 mmol) in Et2O (5 mL) was added 2 ml (15.7 mmol) of BF3• Et2O slowly by maintaining the reaction temperature at −78°C. The mixture was allowed to reach −20°C and then stirring was continued at −20°C for 4 days. At the end of this time period, the reaction mixture was slowly added to ice-cooled, saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (10 ml), and the mixture was stirred for additional 30 min at 0°C. After the aqueous work-up, the separated organic layer was washed thrice with saturated NaHCO3 and H2O and then dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in 11 ml of Et2O/hexane (4/7) for recrystallization and afforded white crystals of (2S,4S)-1 (0.37 g, 70%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ ppm 1.59 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 4.49 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 5.13–5.16 (m, 2H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.42 (m, 10H).

(2S,4R)-Benzyl-4-methyl-5-oxo-4-(pent-4-enyl)-2-phenyloxazolidine-3carboxylate, (2S,4R), (3)

(2S,4S)-1 (0.22 g, 0.71 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF/HMPA (4:1, 2 ml) under an argon atmosphere. The resultant solution was cooled to −78°C. Into that 1M LiHMDS solution (1.1 ml, 1.065 mmol) in THF was added slowly under nitrogen at −78°C. After the addition of LiHMDS, the slightly yellow solution was stirred at this temperature for 1 h. Next 5-iodo-1-pentene (0.21 g, 1.06 mmol, synthesized from 5-Bromo-1-pentene) was added dropwise into the reaction mixture under an argon atmosphere and the resultant mixture was slowly allowed to reach room temperature. The resultant reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. At end, saturated NH4Cl solution was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted in ether. The organic layer was washed subsequently with saturated NaHCO3 and saturated aqueous NaCl solutions, respectively. The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated. The product was purified by flash column chromatography and elution with 30% DCM in hexane gives the gummy product (0.08 gm) with 30 % isolated yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ ppm 1.26–1.33 (m, 2H), 1.69 (s, 1H), 1.79 (s, 3H), 2.06–2.08 (m, 2H), 2.14–2.196 and 2.49–2.56 (m, 1H), 4.91–5.035 (m, 4H), 5.56–5.77 (m, 1H), 6.4 (d, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.416 (m, 10 H).

S-2-Amino-2-methylhept-6-enoic-acid, (4)

A solution of 3 (1.1 gm, 2.9 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (52 ml) was treated with potassium trimethylsilanolate (90% pure; 1.1 gm, 8.6 mmol) and the mixture was heated at 75°C for 2 h 30 min by which time all starting material was consumed. The mixture was diluted with methanol and the solvents were removed under reduced pressure. The resultant mixture was diluted with dichloromethane and evaporated under vacuum. The crude solid was used directly for the next step without further purification.

Fmoc-S-2-(2’-pentyl)alanine, (5)

To a solution of 4 (0.1 gm, 0.64 mmol) in water (8 ml), DIEA (0.167 ml, 0.96 mmol) was added followed by the addition of Fmoc-OSu (0.237gm, 0.7 mmol) in acetonitrile (8 ml). The resultant mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5–6 h. The solvent was evaporated and the resultant solution was dissolved in water and subsequently acidified with 2N HCl solution. The aqueous layer was extracted with ethylacetate for 3 times and purified by silica column chromatography using hexane/DCM and later MeOH/DCM as eluent. The product elutes with 3% MeOH/DCM mixture. This gives rise to 0.12 gm of the product with 50% isolated yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ ppm 1.24–1.43 (m, 2H), 1.63 (s, 3H), 1.87–1.89 (m, 1H), 2.06–2.16 (m, 3H), 4.22 (t, J = 6.48 Hz, 1H), 4.41(bs, 2H), 4.96–5.03 (m, 2H), 5.52 (bs, 1H), 5.76 (m, 1H), 7.315 (t, J1 = J2 = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.6 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 7.48 Hz, 2H), 10.66 (bs, 1H).

5-iodo-1-pentene, (2)

5-Bromo-1-pentene (0.8 ml, 6.71 mmol) was added to a solution of sodium iodide (2.0 gm, 13.3 mmol) in acetone (22 ml). The reaction mixture was heated at 60°C for 2 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and diluted with water (100 ml) and extracted with pentane 3-times. The pentane layers were combined, washed with brine, dried over sodium sulfate and concentrated to give 5-iodo-1-pentene. The product was obtained as 90% isolated yield (1.2 gm). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ ppm 1.91 (p, J1 = 7.12 Hz, J2 = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.16 (q, J1 = 6.7 Hz, J2 = 6.82 Hz, 2H), 3.19 (t, J1 = 6.88 Hz, J2 = 6.92 Hz, 2H), 5.00–5.10 (dd, J1 = 17.12 Hz, J2 = 10.12 Hz, 2H), 5.69–5.80 (m, 1H).

Similarly Fmoc-S-2-(2’-octyl alanine)alanine, was obtained starting from Z-D-alanine using 8-iodo-1octene. Fmoc-R-2-(2’-pentyl)alanine was obtained starting from Z-L-alanine using similar reaction conditions as described above.

Synthesis of N-Fmoc-S-2-(2’-octyl)alanine

(2S,4R)-Benzyl-4-methyl-5-oxo-4-(oct-4-enyl)-2-phenyloxazolidine-3carboxylate, (2S,4R)

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ ppm 1.05–1.31 (m, 8H), 1.69 (s, 1H), 1.8 (s, 3H), 2.03–2.2 (m, 3H), 4.94–5.35 (m, 4H), 5.78–5.82 (m, 1H), 6.41 (d, 1H), 6.89 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.42 (m, 10H).

N-Fmoc-S-2-(2’-octyl)alanine

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ ppm 1.09–1.37 (m, 8H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.88 (bs, 1H), 2.03–2.18 (m, 3H), 4.25 (s, 1H), 4.43–4.72 (m, 2H), 4.96–5.05 (m, 2H), 5.71 (bs, 1H), 5.78–5.88 (m, 1H), 7.34 (t, J1 = 7.24, J2 = 7.32 Hz, Hz, 2H), 7.42 (t, J1 = 7.24, J2 = 7.0, 2H), 7.63 (bs, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 7.44 Hz, 2H), 11.6 (bs, 1H).

8-iodo-1-octene

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ ppm 1.25–1.43 (m, 6H), 1.82 (p, J1 = 7.12 Hz, J2 = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.04 (q, J1 = 6.76 Hz, J2 = 6.84 Hz, 2H), 3.18 (t, J1 = J2 = 7.04 Hz, 2H), 4.92–5.02 (m, 2H), 5.74–5.81 (m, 1H).

Peptides 27–28 were synthesized on solid phase by sequentially adding appropriate amino acids along with the peptide coupling reagents (HATU, DIEA) onto the Fmoc-Rink Amide resin 78, 79. Each amino acid coupling was done for 1.5 h to 2 h. Both peptides were obtained in ~60–80% isolated yields after purification by RP-HPLC and characterized by ESI-MS. All solvents and reagents used were of highest purity available. Fmoc-Asp(tBu)-OH, 1 was purchased from Novabiochem and N,O-dimethyl hydroxylamine hydrochloride was bought from Acros. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker 400 spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm downfield from the internal standard (TMS).

Peptide concentrations were tested by absorbance at 280 nm or densitometry measurements for the gel-based activity measurements. A consistent error of the peptide concentration was determined to be no more than two-fold more concentrated than the expected amount. The inhibitory constant, Ki, was adjusted accordingly. However, the ranking of our best peptides were not changed, therefore our overall conclusions remain the same.

Activity Assays

For measurements of caspase activity, 700 nM freshly purified protein was assayed over the course of 10 minutes in a caspase-9 activity assay buffer containing 100 mM MES pH 6.5, 10% PEG 8,000 and 10 mM DTT 80. 300 µM fluorogenic substrate, LEHD-AFC, (N-acetyl-Leu-Glu-His-Asp-AFC (7-amino-4-fluorocoumarin), Enzo Lifesciences) Ex395/Em505, was added to initiate the reaction. Assays were performed in duplicate at 37°C in 100 µL volumes in 96-well microplate format using a Molecular Devices Spectramax M5 spectrophotometer. Initial velocities versus inhibitor concentration were fit to a rectangular hyperbola using GraphPad Prism (Graphpad Software) to calculate Ki app.

Proteolytic cleavage gel-based caspase-9 activity assays were performed for testing the ability of each peptide to inhibit caspase-9 against a natural substrate. Cleavage of the full-length procaspase-7 variant C186A, which is catalytically inactive and incapable of self-cleavage, was used to report activity. 1 µM full-length procaspase-7 C186A was incubated with 1 µM active caspase-9 in a minimal assay buffer containing 100 mM MES pH 6.5 and 10 mM DTT in a 37°C water bath for 1 hr. Samples were analyzed by 16% SDS-PAGE to confirm the exact lengths of the cleavage products. Percent inhibition was calculated using Gene Tools (SynGene) by producing a standard curve from densiometry values for process and unprocessed substrate (caspase-7 C186A).

Mass Spectrometry

Peptide 2 in water was diluted in α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix to a final concentration of 5 µM. 1µl was spotted onto a target for analysis by Omniflex MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Inc, Billerica, MA) using linear detection mode. Peptides 27 and 28 in water were diluted in 0.1% formic acid to a final concentration of 5 µM for direct injection onto Esquire-LC electrospray ion trap mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Inc.) set up with an ESI source and positive ion polarity. The MS instrument system was equipped with an HP1100 HPLC system (Hewlett-Packard). Scanning was carried out between 600–1400 m/z and the final spectra obtained were an average of 10 individual spectra. All mass spectral data were obtained at the University of Massachusetts Mass Spectrometry Facility, which is supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation.

Secondary Structure Analysis by Circular Dichroism

The secondary structure of the peptide variants was monitored via CD spectra (250-190 nm) measured on a J-720 circular dichroism spectrometer (Jasco) with a peltier controller. Peptides 2, 3, 5, 8, 27, and 28 in water and Peptides 11, 25 and aPP in 20 mM Tris pH 8.0 were diluted to 15 µM and analyzed at room temperature. Peptides 27 and 28 were monitored for secondary structure formation before and after the metathesis reaction.

Computational Structure Prediction

The structures of aPP variants were predicted computationally using Rosetta 58, 59. Folding simulations were performed on the designed peptide sequences 10–26 using the scaffold aPP as a control. The structure of aPP was reasonably well simulated as assessed by backbone alignment and rotomer confirmation of the top 15 lowest scored predicted conformations. Structural visualization and model interrogation was performed in The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3, Schrödinger, LLC 73.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM80532), a Young Investigator Grant from the Beckman Foundation and the National Science Foundation (CHE-0739227).

Abbreviations

- CD

circular dichroism spectroscopy

- FMK

fluoromethyl ketone

- AFC

amino fluoro coumarin

- Aib

aminoisobutryic acid

- aPP

avian pancreatic polypeptide

- CARD

caspase activation and recruitment domain

- LEHD

canonical caspase-9 recognition site leucine-glutamate-histidine-aspartate

- BIR3

baculovirus inhibitory repeat 3

- XIAP

x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

References Cited

- 1.Reed JC, Tomaselli KJ. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:586–592. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaffidi C, Medema JP, Krammer PH, Peter ME. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26953–26958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medema JP, Scaffidi C, Kischkel FC, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Krammer PH, Peter ME. EMBO J. 1997;16:2794–2804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavrik I, Krueger A, Schmitz I, Baumann S, Weyd H, Krammer PH, Kirchhoff S. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:144–145. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou H, Li Y, Liu X, Wang X. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:11549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pop C, Timmer J, Sperandio S, Salvesen GS. Mol Cell. 2006;22:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez J, Lazebnik Y. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3179–3184. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stennicke HR, Jurgensmeier JM, Shin H, Deveraux Q, Wolf BB, Yang X, Zhou Q, Ellerby HM, Ellerby LM, Bredesen D, Green DR, Reed JC, Froelich CJ, Salvesen GS. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27084–27090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muzio M, Chinnaiyan AM, Kischkel FC, O'Rourke K, Shevchenko A, Ni J, Scaffidi C, Bretz JD, Zhang M, Gentz R. Cell. 1996;85:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X. Cell. 1997;91:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slee EA, Harte MT, Kluck RM, Wolf BB, Casiano CA, Newmeyer DD, Wang HG, Reed JC, Nicholson DW, Alnemri ES. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;144:281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiozaki EN, Chai J, Rigotti DJ, Riedl SJ, Li P, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Fairman R, Shi Y. Molecular cell. 2003;11:519–527. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renatus M, Stennicke HR, Scott FL, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:14250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231465798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cain K, Brown DG, Langlais C, Cohen GM. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:22686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan S, Yu X, Asara JM, Heuser JE, Ludtke SJ, Akey CW. Structure. 2011;19:1084–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malladi S, Challa-Malladi M, Fearnhead HO, Bratton SB. EMBO J. 2009;28:1916–1925. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davoodi J, Mohammad-Gholi A, Es-Haghi A, MacKenzie A. J Biochem. 2007;141:293–299. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun C, Cai M, Meadows RP, Xu N, Gunasekera AH, Herrmann J, Wu JC, Fesik SW. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:33777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckelman BP, Salvesen GS. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3254–3260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vucic D, Franklin MC, Wallweber HJA, Das K, Eckelman BP, Shin H, Elliott LO, Kadkhodayan S, Deshayes K, Salvesen GS. Biochemical Journal. 2005;385:11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin H, Renatus M, Eckelman BP, Nunes VA, Sampaio CAM, Salvesen GS. Biochemical Journal. 2005;385:1. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairbrother WJ, Christinger HW, Cochran AG, Fuh G, Keenan CJ, Quan C, Shriver SK, Tom JYK, Wells JA, Cunningham BC. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17754–17764. doi: 10.1021/bi981931e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li B, Tom JY, Oare D, Yen R, Fairbrother WJ, Wells JA, Cunningham BC. Science. 1995;270:1657–1660. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felix AM, Heimer EP, Wang CT, Lambros TJ, Fournier A, Mowles TF, Maines S, Campbell RM, Wegrzynski BB, Toome V, et al. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1988;32:441–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1988.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osapay G, Taylor JW. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114:6966–6973. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phelan JC, Skelton NJ, Braisted AC, McDowell RS. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997;119:455–460. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor JW. Peptide Science. 2002;66:49–75. doi: 10.1002/bip.10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson DY, King DS, Chmielewski J, Singh S, Schultz PG. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113:9391–9392. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leduc AM, Trent JO, Wittliff JL, Bramlett KS, Briggs SL, Chirgadze NY, Wang Y, Burris TP, Spatola AF. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:11273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934759100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghadiri MR, Choi C. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1990;112:1630–1632. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelso MJ, Beyer RL, Hoang HN, Lakdawala AS, Snyder JP, Oliver WV, Robertson TA, Appleton TG, Fairlie DP. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004:126. doi: 10.1021/ja037980i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruan F, Chen Y, Hopkins PB. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1990;112:9403–9404. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunel FM, Dawson PE. Chem Commun. 2005:2552–2554. doi: 10.1039/b419015g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karle IL, Balaram P. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6747–6756. doi: 10.1021/bi00481a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schafmeister CE, Po J, Verdine GL. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2000;122:5891–5892. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walensky LD, Pitter K, Morash J, Oh KJ, Barbuto S, Fisher J, Smith E, Verdine GL, Korsmeyer SJ. Molecular cell. 2006;24:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Kung AL, Gilliland DG, Verdine GL, Bradner JE. Nature. 2009;462:182–188. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernal F, Wade M, Godes M, Davis TN, Whitehead DG, Kung AL, Wahl GM, Walensky LD. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blackwell HE, Grubbs RH. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 1998;37:3281–3284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981217)37:23<3281::AID-ANIE3281>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patgiri A, Jochim AL, Arora PS. Accounts of chemical research. 2008;41:1289–1300. doi: 10.1021/ar700264k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chin JW, Grotzfeld RM, Fabian MA, Schepartz A. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2001;11:1501–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodges AM, Schepartz A. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:11024–11025. doi: 10.1021/ja074859t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chin JW, Schepartz A. Angewandte Chemie. 2001;113:3922–3925. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kritzer JA, Zutshi R, Cheah M, Ran FA, Webman R, Wongjirad TM, Schepartz A. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:29–31. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimba N, Nomura AM, Marnett AB, Craik CS. Journal of virology. 2004;78:6657. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6657-6665.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chin JW, Schepartz A. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:2929–2930. doi: 10.1021/ja0056668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montclare JK, Schepartz A. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:3416–3417. doi: 10.1021/ja028628s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zondlo NJ, Schepartz A. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1999;121:6938–6939. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marshall GR, Hodgkin EE, Langs DA, Smith GD, Zabrocki J, Leplawy MT. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1990;87:487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prasad B, Balaram P. CRC critical reviews in biochemistry. 1984;16:307. doi: 10.3109/10409238409108718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toniolo C, Bonora GM, Bavoso A, Benedetti E, di Blasio B, Pavone V, Pedone C. Biopolymers. 1983;22:205–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1983.tb02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Vaillancourt JP, Zamboni R, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:362–369. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lonovics J, Devitt P, Watson LC, Rayford PL, Thompson JC. Archives of Surgery. 1981;116:1256. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1981.01380220010002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blundell T, Pitts J, Tickle I, Wood S, Wu CW. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1981;78:4175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tonan K, Kawata Y, Hamaguchi K. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4424–4429. doi: 10.1021/bi00470a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huber KL, Olson KD, Hardy JA. Protein expression and purification. 2009;67:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simons KT, Strauss C, Baker D. Journal of molecular biology. 2001;306:1191–1199. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rohl CA, Strauss CEM, Misura K, Baker D. Methods in enzymology. 2004;383:66–93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naganagowda GA, Gururaja TL, Levine MJ. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1998;16:91–107. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1998.10508230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arnott S, Dover SD. Acta Crystallogr B. 1968;24:599–601. doi: 10.1107/s056774086800289x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andrade MA, Chacon P, Merelo JJ, Moran F. Protein Eng. 1993;6:383–390. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walensky LD, Kung AL, Escher I, Malia TJ, Barbuto S, Wright RD, Wagner G, Verdine GL, Korsmeyer SJ. Science. 2004;305:1466. doi: 10.1126/science.1099191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coe DM, Perciaccante R, Procopiou PA. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:1106–1111. doi: 10.1039/b212454h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Procopiou PA, Ahmed M, Jeulin S, Perciaccante R. Organic & biomolecular chemistry. 2003;1:2853–2858. doi: 10.1039/b303471m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seebach D, Fadel A. Helvetica chimica acta. 1985;68:1243–1250. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams RM, Im MN. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113:9276–9286. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aurora R, Rose G. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 1998;7:21. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Banerjee R, Basu G, Roy S, Chène P. The Journal of peptide research. 2002;60:88–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2002.201005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bird GH, Madani N, Perry AF, Princiotto AM, Supko JG, He X, Gavathiotis E, Sodroski JG, Walensky LD. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:14093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002713107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Phillips C, Bazin R, Bent A, Davies NL, Moore R, Pannifer AD, Pickford AR, Prior SH, Read CM, Roberts LR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011 doi: 10.1021/ja202946k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu Z, Sun C, Olejniczak ET, Meadows RP, Betz SF, Oost T, Herrmann J, Wu JC, Fesik SW. Nature. 2000;408:1004–1008. doi: 10.1038/35050006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schrödinger L. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rotonda J, Nicholson DW, Fazil KM, Gallant M, Gareau Y, Labelle M, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Ruel R, Vaillancourt JP, Thornberry NA, Becker JW. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:619–625. doi: 10.1038/nsb0796-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson EP, Leiting B, Ruel R, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32608–32613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Methods. 1999;17:313–319. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witkowski WA, Hardy JA. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1459–1468. doi: 10.1002/pro.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barany G, Kneib Cordonier N, Mullen DG. International Journal of Peptide and Protein Research. 1987;30:705–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1987.tb03385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fields GB, Noble RL. International Journal of Peptide and Protein Research. 1990;35:161–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:25719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]