Abstract

Glutamate-induced neurotoxicity is the primary molecular mechanism that induces neuronal death in a variety of pathologies in central nervous system (CNS). Toxicity signals are relayed from extracellular space to the cytoplasm by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) and regulate a variety of survival and death signaling. Differential subunit combinations of NMDARs confer neuroprotection or trigger neuronal death pathways depending on the subunit arrangements of NMDARs and its localization on the cell membrane. It is well-known that GluN2B-contaning NMDARs (GluN2BRs) preferentially link to signaling cascades involved in CNS injury promoting neuronal death and neurodegeneration. Conversely, less well-known mechanisms of neuronal survival signaling are associated with GluN2A-comtaining NMDARs (GluN2AR)-dependent signal pathways. This review will discuss the most recent signaling cascades associated with GluN2ARs and GluN2BRs.

Keywords: NMDA receptor, GluN2A, GluN2B, neuronal survival, neuronal death

Introduction

The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) play functionally diverse roles during physiological and pathopysiological conditions in mammalian organisms. NMDARs are a subtype of ionotropic glutamate receptors permeable to Ca2+ that is responsible for the majority of excitatory neural transmission in the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. These ligand-gated receptors have been shown to play crucial roles in regulation of neural development [2,3], synaptic plasticity [4,5], and glutamate-induced neurotoxicity [6-8]. NMDAR dysfunction has been implicated in many CNS pathologies including traumatic brain injury, neurodegenerative diseases and ischemic stroke [9-11]. The theory of glutamate-induced neurotoxicity is the mechanism of neuronal death thought to underlie many types of CNS injuries. Glutamate-induced neurotoxicity occurs due to an overactivation of glutamate receptors, mainly the NMDARs increase their permeability to Ca2+ induced by the overly released extracellular glutamate and trigger neuronal death events [12,13].

NMDARs are known to be heteromeric tetramers in molecular structure, containing an obligate GluN1 subunit, with GluN2 (A-D) and GluN3(A-B) subunits [1,14]. The receptor is activated by agonist glutamate binding to the GluN2 subunit and co-agonist glycine and/or D-Serine binding to the GluN1 subunit to regulate channel gating and influx of the pertinent cation second-messenger Ca2+ via the channel pore [15,16]. GluN2A-comtaining NMDARs (GluN2ARs) and GluN2B-comtaining NMDARs (GluN2BRs) are the most common NMDAR subtypes found in mammalian CNS. The differences in NMDAR function may be attributed to the specific subunit combinations that are present in each receptor subtype as they show functionally different properties regarding electrophysiology and different sensitivities to regulation by intracellular signals [17].

Pharmacological antagonists targeting NMDARs have been unsuccessful in clinical trials in treating various CNS disease states [18-20]. This could be due simply to the possibility that NMDARs potentiate both cell-survival signaling and cell-death signaling. Thus, nonspecific inhibition of NMDARs will not only block the neuronal death pathways but also inhibit pro-survival signaling. Among many extracellular and intracellular processes that can modulate NMDARs, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation by protein kinases and phosphatases are especially important, because they can critically regulate trafficking, surface expression, and the channel properties of NMDARs [21,22]. Targeting intracellular pathways that NMDARs govern may provide a stronger mechanistic basis to promote cell survival during CNS injury. This review will discuss the roles of GluN2ARs and GluN2BRs in neuronal survival and death and the associated intracellular signaling cascades that are initiated by each receptor subtype and how cross-talk among these pathways can regulate neuronal cell fate in CNS pathologies. Furthermore, the dissection of these intracellular pathways will elucidate therapeutic targets that may play roles in regulating neuron cell survival.

GluN2AR in neuronal survival

GluN2AR receptor activation has been shown to link preferentially to intracellular signaling cascades during CNS injury that promote cell survival [23-25], and GluN2ARs localize preferentially to the synaptic zone [26,27]. One theory explaining the roles of NMDARs during the pathogenesis of CNS injury is built upon the notion that location, either synaptic or extrasynaptic, may determine function. In hippocampal neuron culture, it has been demonstrated that synaptic activation of GluN2ARs preferentially activate CREB, enhance BDNF gene expression and activate anti-apoptotic signaling pathways, all mechanisms that contribute to neuronal cell survival during CNS insult [28]. Similarly, GluN2AR activation in mature rat cortical cultures, located both synaptically and extrasynaptically, confer neuroprotection against neuronal damage [9]. In an in-vivo model of rat focal ischemic stroke, GluN2ARs protect against apoptotic signaling, in part due to the activation of an Akt-dependent signaling pathway [9]. In another study that pharmacologically disabled GluN2ARs, it was shown that neuron cell death increased after transient global ischemia in rats and that GluN2ARs were responsible for ischemia-induced activation of the neuroprotective transcription factor CREB, enhancing expression of gene targets cpg15 and BDNF [24]. In a traumatic brain injury model in rat neuron culture, GluN2ARs inhibition were shown to potentiate caspase-3 activation, a marker of apoptotic signaling [25]. In rat brain slices and in vivo rat studies, addition of GluN2AR receptor antagonists to disable signaling capacity of GluN2ARs resulted in increased cell death, also corresponding to an upregulation of caspase-3 activity after phencyclidine (PCP) treatment, providing further evidence that GluN2ARs link to neuroprotective signaling during CNS insult [23].

GluN2AR-dependent signal pathways in neuronal survival

GluN2AR-PTEN-TDP43 pathway

A GluN2AR-PTEN-TDP-43 dependent pathway is shown to protect against neuronal injury [29]. In an extracellular glutamate accumulation injury model GluN2AR stimulation, but not GluN2BR stimulation, triggered a reduction in PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) expression [29]. PTEN plays a role in many pathological processes surrounding neuronal injury, such as those associated with brain ischemia and neurological disease [30,31]. Interestingly, PTEN localizes to both the nucleus and cytoplasm of neuronal and glial cells [32,33] and plays similar roles in both locations in promoting apoptosis [34]. Recent studies have shown that suppression of PTEN protects against neuronal death [35-37]. Thus, down-regulating PTEN may represent a novel pharmacological approach for treatment of CNS injury [28,38].

The dysfunction of TAR DNA-binding protein-43 (TDP-43) is recently implicated in neurodegenerative diseases[39]. However, the physiological and pathophysiological functional profiles of TDP-43 have not yet been fully elucidated. Knock-down and deletion of nuclear TDP-43 has been shown to be detrimental to neuronal cells, potentiating neurodegenerative signaling while endogenous TDP-43 has been shown to be neuroprotective in the nucleus [29,40,41]. A marked increase in TDP-43 expression in the nucleus has been linked to neuron cell viability during in vitro neurodegenerative injury situations [29]. The functional consequence of TDP-43 remains elusive because this protein shuffles between the nucleus and cytoplasm [42]. Although TDP-43 may functionally serve as a neuroprotectant in the nucleus, TDP-43 plays a different role in the cytoplasm where its involvement in protein aggregate formation characterizes the pathogenesis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [43]. It is possible that increased TDP-43 expression in the nucleus can trigger neuroprotective signaling pathways whereas its export to the cytoplasm may have deleterious effects. In response to glutamate accumulation, the endogenous TDP-43, behaving as a pro-survival signaling protein in the nucleus, is only increased in the nucleus and does not translocate to cytoplasma [29]. Interestingly, PTEN is shown to negatively regulate TDP-43 expression in the nucleus, and the activation of GluN2ARs exerts its neuroprotective effects through suppression of PTEN and subsequent increase in nuclear TDP-43 whereas GluN2BRs have no effect on PTEN expression [29]. This finding demonstrates a GluN2A-activation dependent signaling pathway, namely, the GluN2AR-PTEN-TDP-43, to trigger neuroprotection through donwregulation of PTEN, causing an augmentation in nuclear TDP-43 in a neurodegenerative model. However, evidence linking TDP-43 as being protective in other CNS pathologies such as traumatic brain injury and ischemic stroke has yet to be shown. Thus, delving deeper into the molecular mechanisms that regulate TDP-43 localization and how TDP-43 exerts its differential effects in the cell based on its locale may elucidate therapeutic targets to combat CNS injury.

DJ-1-PTEN-PINK1-GluN2AR pathway

In rat cortical cultures, a DJ-1-PTEN-PINK1-GluN2AR signaling cascade is found to confer neuroprotection [44]. Study on DJ-1 gene deletion reveals that DJ-1 is an atypical peroxiredoxin-like peroxidase [45] and loss-of-function mutations in DJ-1 have been identified in patients with early-onset autosomal recessive Parkinsonism [46], suggesting that dysfunction of DJ-1 may contribute to the dopaminergic neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease (PD). More recent studies have demonstrated that DJ-1 is involved in stroke-induced brain injury [47,48], indicating that DJ-1 dysfunction may play a broad role in the CNS injury situations. DJ-1 suppression led to an increase in PTEN expression in rat cortical culture, and induced a neuroprotective effect by enhancing PINK1-GluN2AR signaling [44].

Although increase in PTEN activity has previously been linked to apoptotic signaling pathways, it also has been shown to induce an increase of PINK1 (PTEN-induced kinase 1; also called PARK6) expression and GluN2AR-mediated currents. The newly identified PINK1 gene encodes a serine⁄threonine kinase [49]. Similar to DJ-1, loss-of-function mutations in the PINK1 gene have been linked to early onset of PD [49,50]. Inactivation of Drosophila PINK1 results in the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons [51], and functional defects in mitochondria, causing mitochondrial calcium overload, increasing sensitivity to oxidative stress, reducing dopamine release and impairing synaptic plasticity [52,53]. PINK1 is neuroprotective in both in vitro and in vivo experimental models [54,55]. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings to measure GluN2AR- and GluN2BR-mediated components of NMDAR currents were performed, with the use of GluN2AR specific antagonist NVP-AAM077 and GluN2BR specific antagonist Ro 25-6981 [9,56]. In the neurons transfected with PINK1 cDNAs and siRNAs, the overexpression and suppression of PINK1, respectively, increased and inhibited GluN2AR-mediated currents without effect on GluN2BR-mediated currents [44]. These data indicate that the PINK1 regulation of NMDAR function is resulted from altered GluN2AR activity. As GluN2AR-dependent signaling is believed to be neuroprotective, these results suggest a possibility that PINK1 dysfunction may promote neuronal death through inhibition of GluN2ARs.

In rat cortical cell culture studies, suppressing DJ-1 protein expression in neurons transfected with DJ-1 siRNAs increased GluN2AR-mediated whole-cell currents [44]. Conversely, DJ-1 over-expression in rat cortical neurons inhibited GluN2BR-mediated currents [44]. These results suggest that DJ-1 might induce self-protective signaling through increasing GluN2AR activity and suppressing GluN2BR activity. Suppression of DJ-1 together with PINK1 knockdown, compared with suppression of DJ-1 or PINK1 alone, significantly increases NMDAR-mediated neuronal death [44]. Taken together, these results indicate that NMDAR function is in part regulated by the DJ-1 -PTEN-PINK1-GluN2AR pathway. As a downstream signal of DJ-1, PINK1 may respond collaboratively to counteract DJ-1 dysfunction-induced neuronal damage, which may delay neuronal death and possibly contributes to the slow neurodegenerative process in PD.

GluN2BR in neuronal death and neurodegeneration

As a major player in NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity, GluN2BR overactivation during CNS injury couples to cellular death pathways via suppression of CREB-, ERK-, and PINK1-dependent survival pathways [57-59]. A body of evidence provides data suggesting that calcium flux through extrasynaptic GluN2BRs play critical roles in modulating cell death pathways in contrast to GluN2ARs [28,38]. Dysfunction of the regulatory events governing the endocytosis and insertion of NMDARs to and from the plasma membrane, in both synaptic and extrasynatpic locations, may have dele-terious effects on cell survival. Inhibition of GluN2BRs in rats revealed that cell death was decreased after ischemic insult and enhanced preconditioning- induced neuroprotection [24], implicating their involvement in regulation of apoptosis. In cultured mouse cortical neurons, the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN acts as a crucial upstream signal to regulate Glu-N2BRs [35]. The protein phosphatase activity of PTEN, through downregulating GluN2BRs, protects against ischemic neuronal death [35]. GluN2BRs are found more readily in extrasynaptic sites and activation of these receptors inhibits nuclear signaling to CREB, reduces BDNF activity and plays a role in mitochondrial dysfunction ultimately potentiating cellular death [26,27]. How GluN2BR-interacting signaling is involved in neurodegeneration and neuronal death remains to be determined.

GluN2BR-dependent signal pathways in neuronal death and neurodegeneration

DJ-1-PTEN-GluN2BR pathway

Recent study indicates that a DJ-1-PTEN-GluN2BR-mediated pathway promotes cell death [44]. Suppressing DJ-1 protein expression in neurons transfected with DJ-1 siRNAs revealed an increase in not only the GluN2AR-mediated currents but also the GluN2BR-currents [44]. These results suggest that DJ-1 dysfunction, while inducing neuronal death through enhancing GluN2BR-dependent cell death signaling, might also promote self-protective signaling through increasing GluN2AR function. The regulation of NMDAR function by DJ-1 could be attributable to the altered expression of NMDARs on the cell surface [22]. Neurons with reduced DJ-1 expression through transfection with DJ-1 siRNAs resulted in an increased surface expression of GluN2B but not GluN2A subunits [44]. DJ-1 cDNA transfection led to a decreased surface expression of GluN2BRs in cortical neurons [44]. Because the total GluN2B subunit levels were not altered by DJ-1 knockdown or overexpression, the altered surface expression of GluN2B could be the result of an altered delivery and/or internalization of NMDARs. Thus, the post-transcriptional mechanisms may mediate the DJ-1 regulation of GluN2BR surface expression [44]. As the phosphatase PTEN positively regulates the function of GluN2BRs [35,36] and DJ-1 is a negative regulator of PTEN [60], PTEN might contribute to DJ-1 knockdown-induced enhancement of GluN2BR function. Indeed, western blots confirmed that DJ-1 knockdown resulted in an increased protein expression of PTEN in the neurons and that PTEN inhibitor resulted in a reduction of DJ-1 suppression-induced increase in GluN2BR currents [44]. Thus, DJ-1 knockdown-induced potentiation of GluN2BR function is mediated in part by increased PTEN expression, which promotes neuronal death and neurodegeneration [44].

GluN2BR-PINK1-Akt pathway

GluN2BR can suppress PINK1-Akt pathway to enhance neurodegeneration and neuronal death. To test whether PINK1, in addition to being involved in the pathogenesis of PD [49], plays a role in ischemic neuronal death, the protein expression of PINK1 in oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) conditions in vitro was observed [57]. The amount of PINK1 protein was decreased in neurons exposed to OGD compared with that in control neurons without OGD treatment and the levels of neuronal injury was increased with the extension of OGD treatment time [57]. This result suggests that the reduction in protein expression of PINK1 may be involved in ischemic neuron injury. Because inhibition of NMDARs by its antagonist or channel blocker MK801 significantly reduced OGD-induced reduction of PINK1 expression [57], the overactivation of NMDARs may be responsible in part for OGD-induced PINK1 suppression. As overactivation of GluN2BRs plays the major role in NMDAR excitotoxicity-mediated neuronal death [28,35,36], overactivation of GluN2BRs may be involved in OGD-induced PINK1 reduction. By treating neuronal cultures with a GluN2BR antagonist during OGD/reoxygenation, results indicated that OGD-induced reduction of PINK1 expression was inhibited by GluN2BR antagonist [57]. However, inhibition of GluN2ARs exhibited no significant effect on OGD-induced decrease of PINK1 expression [57]. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of Akt, a known neuroprotectant, was inhibited while PINK1 protein level was reduced in neurons treated with OGD. The reduction in the levels of Akt phosphorylation was partially recovered by inhibition of GluN2BRs. These results suggest that GluN2BR overactivation triggers a reduction in PINK1 and mediates cell death signaling in part through the suppression of the neuroprotective AKT pathway.

Closing remarks

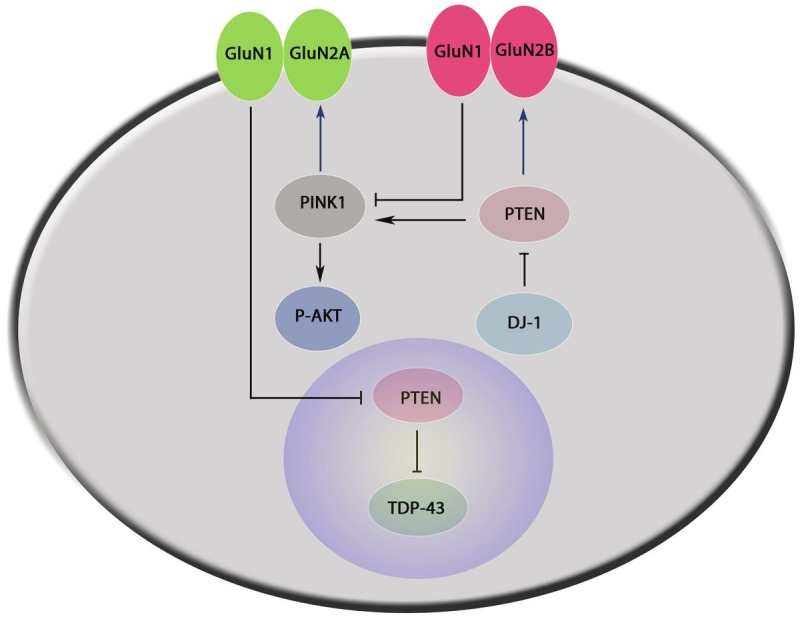

NMDAR plays a major role in excitotoxicity-mediated neuronal death and neurodegeneration in various neurological disorders. However, clinical trials using NMDAR antagonists show disappointing outcome. We now believe that while NMDAR antagonists reduce GluN2BR-induced neuronal death, the GluN2AR-mediated neuroprotective effect is also suppressed. Thus, uncovering the cellular and molecular mechanisms that specifically link to GluN2AR-mediated neuroprotection or GluN2BR-dependent cell death-promoting signal pathways would provide a molecular basis to develop potent therapeutic strategy. This review discusses the recent progress in understanding how GluN2AR and GluN2BR interact with intracellular signaling to exert their opposing effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

GluN2AR- and GluN2BR-interacting signaling in neuronal survival and death. 1) GluN2AR-PTEN-TDP-43: Activation of GluN2AR confers neuroprotection through downregulation of nuclear PTEN and enhancing function of TDP-43. 2) DJ-1-PTEN-PINK1-GluN2AR: DJ-1 negatively regulates PTEN function inducing neuroprotection by increasing PINK1 expression in the cytoplasm. PINK1 can positively regulate both GluN2AR activity and the Akt pathway to promote cell survival. 3) DJ-1-PTEN-GluN2BR: DJ-1 negatively regulates PTEN function to play a role by increasing GluN2BR activity. 4) GluN2BR-PINK1-Akt: GluN2BR activation can suppress function of PINK1 and the neuroprotective Akt pathway.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the National Center for Research Resources (RR024210) of NIH, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM103554) of NIH, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders of NIH (R21NS077205), and the American Heart Association (12GRNT9560012) to Qi Wan.

References

- 1.Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Constantine-Paton M, Cline HT, Debski E. Patterned activity, synaptic convergence, and the nmda receptor in developing visual pathways. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:129–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerchner GA, Nicoll RA. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:813–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barria A, Malinow R. Subunit-specific NMDA receptor trafficking to synapses. Neuron. 2002;35:345–53. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00776-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation--A decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–4. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi DW. Glutamate neurotoxicity and diseases of the nervous-system. Neuron. 1988;1:623–34. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aarts M, Liu YT, Liu LD, Besshoh S, Arundine M, Gurd JW, Wang YT, Salter MW, Tymianski M. Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor-PSD-95 protein interactions. Science. 2002;298:846–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu WH, Xu X, Peng LS, Zhong XF, Zhang WF, Soundarapandian MM, Balel C, Wang MQ, Jia NL, Zhang W, Lew F, Chan SL, Chen YF, Lu YM. DAPK1 Interaction with NMDA Receptor NR2B Subunits Mediates Brain Damage in Stroke. Cell. 2010;140:222–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu YT, Wong TP, Aarts M, Rooyakkers A, Liu LD, Lai TW, Wu DC, Lu J, Tymianski M, Craig AM, Wang YT. NMDA receptor subunits have differential roles in mediating excitotoxic neuronal death both in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2846–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0116-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JM, Zipfel GJ, Choi DW. The changing landscape of ischaemic brain injury mecha-nisms. Nature. 1999;399:A7–A14. doi: 10.1038/399a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koutsilleri E, Riederer P. Excitotoxicity and new antiglutamatergic strategies in Parkinson’s diseaseand Alzheimer’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(Suppl 3):S329–31. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipton SA, Rosenberg PA. Excitatory amino-acids as a final common pathway for neurologic disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:613–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benveniste H, Drejer J, Schousboe A, Diemer NH. Elevation of the extracellular concentrations of glutamate and aspartate in rat hippocampus during transient cerebral-ischemia monitored by intracerebral microdialysis. J Neurochem. 1984;43:1369–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb05396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheng M, Cummings J, Roldan LA, Jan YN, Jan LY. Changing subunit composition of heteromeric nmda receptors during development of rat cortex. Nature. 1994;368:144–7. doi: 10.1038/368144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JW, Ascher P. Glycine potentiates the nmda response in cultured mouse-brain neurons. Nature. 1987;325:529–31. doi: 10.1038/325529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliet SHR, Mothet JP. Regulation of n-methyl-d-aspartate receptors by astrocytic d-serine. Neuroscience. 2009;158:275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buller AL, Larson HC, Schneider BE, Beaton JA, Morrisett RA, Monaghan DT. The molecularbasis of nmda receptor subtypes - native receptor diversity is predicted by subunit composition. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5471–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05471.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kemp JA, McKernan RM. NMDA receptor pathways as drug targets. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1039–42. doi: 10.1038/nn936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikonomidou C, Turski L. Why did NMDA receptor antagonists fail clinical trials for stroke and traumatic brain injury? Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:383–6. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traynor BJ, Bruijn L, Conwit R, Beal F, O’Neill G, Fagan C, Cudkowicz ME. Neuroprotective agents for clinical trials in ALS: a systematic assessment. Neurology. 2006;67:20–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223353.34006.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swope SL, Moss SJ, Raymond LA, Huganir RL. Regulation of ligand-gated ion channels by protein phosphorylation. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1999;33:49–78. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(99)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll RC, Zukin RS. NMDA-receptor trafficking and targeting: implications for synaptic trans-mission and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:571–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anastasio NC, Xia Y, O’Connor ZR, Johnson KM. Differential role of n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunits 2a and 2b in mediating phencyclidine-induced perinatal neuronal apoptosis and behavioral deficits. Neuroscience. 2009;163:1181–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen M, Lu TJ, Chen XJ, Zhou Y, Chen Q, Feng XY, Xu L, Duan WH, Xiong ZQ. Differential Roles of NMDA Receptor Subtypes in Ischemic Neuronal Cell Death and Ischemic Tolerance. Stroke. 2008;39:3042–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeRidder MN, Simon MJ, Siman R, Auberson YP, Raghupathi R, Meaney DF. Traumatic mechanical injury to the hippocampus in vitro causes regional caspase-3 and calpain activation that is influenced by NMDA receptor subunit composition. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:165–76. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stocca G, Vicini S. Increased contribution of NR2A subunit to synaptic NMDA receptors in developing rat cortical neurons. J Physiol. 1998;507:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.013bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tovar KR, Westbrook GL. The incorporation of NMDA receptors with a distinct subunit composition at nascent hippocampal synapses in vitro. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4180–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04180.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:405–14. doi: 10.1038/nn835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng M, Liao MX, Cui TY, Tian HL, Fan DS, Wan Q. Regulation of nuclear TDP-43 by NR2Acontaining NMDA receptors and PTEN. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1556–67. doi: 10.1242/jcs.095729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omori N, Jin G, Li F, Zhang WR, Wang SJ, Hamakawa Y, Nagano I, Manabe Y, Shoji M, Abe K. Enhanced phosphorylation of PTEN in rat brain after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Brain Res. 2002;954:317–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gary DS, Mattson MP. PTEN regulates Akt kinase activity in hippocampal neurons and increases their sensitivity to glutamate and apoptosis. Neuromolecular Med. 2002;2:261–9. doi: 10.1385/NMM:2:3:261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lachyankar MB, Sultana N, Schonhoff CM, Mitra P, Poluha W, Lambert S, Quesenberry PJ, Litofsky NS, Recht LD, Nabi R, Miller SJ, Ohta S, Neel BG, Ross AH. A role for nuclear PTEN in neuronal differentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1404–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01404.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sano T, Lin H, Chen XS, Langford LA, Koul D, Bondy ML, Hess KR, Myers JN, Hong YK, Yung WKA, Steck PA. Differential expression of MMAC/PTEN in glioblastoma multiforme: Relationship to localization and prognosis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1820–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Planchon SM, Waite KA, Eng C. The nuclear affairs of PTEN. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:249–53. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ning K, Pei L, Liao MX, Liu BS, Zhang YZ, Jiang W, Mielke JG, Li L, Chen YH, El-Hayek YH, Fehlings MG, Zhang X, Liu F, Eubanks J, Wan Q. Dual neuroprotective signaling mediated by downregulating two distinct phosphatase activities of PTEN. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4052–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5449-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang N, El-Hayek YH, Gomez E, Wan Q. Phosphatase PTEN in neuronal injury and brain disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:581–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantley LC, Neel BG. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase AKT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4240–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanhoutte P, Bading H. Opposing roles of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in neuronal calcium signalling and BDNF gene regulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:366–71. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arai T, Hasegawa M, Akiyama H, Ikeda K, Nonaka T, Mori H, Mann D, Tsuchiya K, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, Oda T. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:602–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiesel FC, Voigt A, Weber SS, Van den Haute C, Waldenmaier A, Gorner K, Walter M, Anderson ML, Kern JV, Rasse TM, Schmidt T, Springer W, Kirchner R, Bonin M, Neumann M, Baekelandt V, Alunni-Fabbroni M, Schulz JB, Kahle PJ. Knockdown of transactive response DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) downregulates histone deacetylase 6. EMBO J. 2010;29:209–21. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iguchi Y, Katsuno M, Niwa J, Yamada S, Sone J, Waza M, Adachi H, Tanaka F, Nagata K, Arimura N, Watanabe T, Kaibuchi K, Sobue G. TDP-43 Depletion Induces Neuronal Cell Damage through Dysregulation of Rho Family GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22059–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayala YM, Zago P, D’Ambrogio A, Xu YF, Petrucelli L, Buratti E, Baralle FE. Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3778–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barmada SJ, Skibinski G, Korb E, Rao EJ, Wu JY, Finkbeiner S. Cytoplasmic Mislocalization of TDP-43 Is Toxic to Neurons and Enhanced by a Mutation Associated with Familial Amyotro-phic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:639–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang N, Li LJ, Hu R, Shan YX, Liu BS, Li L, Wang HB, Feng H, Wang DS, Cheung C, Liao MX, Wan Q. Differential regulation of NMDA receptor function by DJ-1 and PINK1. Aging Cell. 2010;9:837–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andres-Mateos E, Perier C, Zhang L, Blanchard-Fillion B, Greco TM, Thomas B, Ko HS, Sasaki M, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. DJ-1 gene deletion reveals that DJ-1 is an atypical peroxiredoxin-like peroxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonifati V, Rizzu P, Squitieri F, Krieger E, Vanacore N, van Swieten JC, Brice A, van Duijn CM, Oostra B, Meco G, Heutink P. DJ-1 (PARK7), a novel gene for autosomal recessive, early onset parkinsonism. Neurol Sci. 2003;24:159–60. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aleyasin H, Rousseaux MWC, Phillips M, Kim RH, Bland RJ, Callaghan S, Slack RS, During MJ, Mak TW, Park DS. The Parkinson’s disease gene DJ-1 is also a key regulator of stroke-induced damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709379104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanagisawa D, Kitamura Y, Inden M, Takata K, Taniguchi T, Morikawa S, Morita M, Inubushi T, Tooyama I, Taira T, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Akaike A, Ariga H. DJ-1 protects against neurodegeneration caused by focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:563–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, Muqit MMK, Harvey K, Gispert S, Ali Z, Del Turco D, Bentivoglio AR, Healy DG, Albanese A, Nussbaum R, Gonzalez-Maldonaldo R, Deller T, Salvi S, Cortelli P, Gilks WP, Latchman DS, Harvey RJ, Dallapiccola B, Auburger G, Wood NW. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304:1158–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Healy DG, Abou-Sleiman PM, Gibson JM, Ross OA, Jain S, Gandhi S, Gosal D, Muqit MMK, Wood NW, Lynch T. PINK1 (PARK6) associated Parkinson disease in Ireland. Neurology. 2004;63:1486–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142089.38301.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang DL, Qian L, Xiong H, Liu JD, Neckameyer WS, Oldham S, Xia K, Wang JZ, Bodmer R, Zhang ZH. Antioxidants protect PINK1-dependent dopaminergic neurons in Drosoph-ila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13520–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604661103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kitada T, Pisani A, Porter DR, Yamaguchi H, Tscherter A, Martella G, Bonsi P, Zhang C, Pothos EN, Shen J. Impaired dopamine release and synaptic plasticity in the striatum of PINK1-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11441–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702717104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gautier CA, Kitada T, Shen J. Loss of PINK1 causes mitochondrial functional defects and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11364–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802076105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haque ME, Thomas KJ, D’Souza C, Callaghan S, Kitada T, Slack RS, Fraser P, Cookson MR, Tandon A, Park DS. Cytoplasmic Pink1 activity protects neurons from dopaminergic neurotoxin MPTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1716–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705363105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood-Kaczmar A, Gandhi S, Yao Z, Abramov ASY, Miljan EA, Keen G, Stanyer L, Hargreaves I, Klupsch K, Deas E, Downward J, Mansfield L, Jat P, Taylor J, Heales S, Duchen MR, Latchman D, Tabrizi SJ, Wood NW. PINK1 Is Necessary for Long Term Survival and Mitochondrial Function in Human Dopaminergic Neurons. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fantin M, Auberson YP, Morari M. Differential effect of NR2A and NR2B subunit selective NMDA receptor antagonists on striato-pallidal neurons: relationship to motor response in the 6-hydroxydopamine model of parkinsonism. J Neurochem. 2008;106:957–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shan YX, Liu BS, Li LJ, Chang N, Li L, Wang HB, Wang DS, Feng H, Cheung C, Liao MX, Cui TY, Sugita S, Wan Q. Regulation of PINK1 by NR2Bcontaining NMDA receptors in ischemic neuronal injury. J Neurochem. 2009;111:1149–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martel MA, Wyllie DJA, Hardingham GE. In developing hippocampal neurons, nr2b-containing n-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (nmdars) can mediate signaling to neuronal survival and synaptic potentiation, as well as neuronal death. Neuroscience. 2009;158:334–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang JQ, Tang QS, Parelkar NK, Liu ZG, Samdani S, Choe ES, Yang L, Mao LM. Glutamate signaling to Ras-MAPK in striatal neurons - Mechanisms for inducible gene expression and plasticity. Mol Neurobiol. 2004;29:1–14. doi: 10.1385/MN:29:1:01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim MJ, Dunah AW, Wang YT, Sheng M. Differential roles of NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in and AMPA receptor Ras-ERK signaling trafficking. Neuron. 2005;46:745–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]