Abstract

Homocysteine (Hcy)-thiolactone is toxic, induces epileptic seizures in rodents, and has been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. Paraoxonase 1 (Pon1), a component of high-density lipoprotein, hydrolyzes Hcy-thiolactone in vitro. Whether this reflects a physiological function and whether Pon1 can protect against Hcy-thiolactone toxicity was unknown. Here we show that Hcy-thiolactone was elevated in brains of Pon1−/− mice (1.5-fold, p = 0.047) and that Pon1−/− mice excrete more Hcy-thiolactone than wild type animals (2.4-fold, p = 0.047). The frequency of seizures induced by intraperitoneal injections of L-Hcy-thiolactone was significantly higher in Pon1−/− mice compared with wild type animals (52.8% versus 29.5%, p = 0.042); the latency of seizures was lower in Pon1−/− mice than in wild type animals (31.8 min versus 41.2 min, p = 0.019). Using the Pon1 null mice, we provide the first direct evidence that a specific Hcy metabolite, Hcy-thiolactone, rather than Hcy itself is neurotoxic in vivo. Our findings indicate that Pon1 protects mice against Hcy-thiolactone neurotoxicity by hydrolyzing it in the brain, and suggest a mechanism by which Pon1 can protect against neurodegeneration associated with hyperhomocysteinemia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, homocysteine thiolactone, neurotoxicity, Pon 1

INTRODUCTION

Homocysteine (Hcy) arises from the metabolism of the essential dietary protein amino acid methionine (Met). Hcy levels are regulated by remethylation to Met, catalyzed by Met synthase (with methyltetrahydrofolate cofactor generated by methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase) and betaine-Hcy methyltransferase, as well as by transsulfuration to cysteine, the first step of which is catalyzed by cystathionine β-synthase. Genetic or nutritional deficiencies in these pathways cause hyperhomocysteinemia, homocystinuria, and lead to heart and brain pathologies [1].

Hcy is also metabolized by methionyl-tRNA synthetase [2] to a chemically reactive thioester, Hcy-thiolactone, which spontaneously N-homocysteinylates protein lysine residues generating N-Hcy-protein [3]. The accumulation of Hcy-thiolactone [4] and N-Hcy-protein [5, 6] greatly increases in genetic or nutritional hyperhomocysteinemia. N-Homocysteinylation causes protein damage [3, 7] by a thyil radical mechanism [8], generates amyloid-like structures [9], and is linked to atherosclerosis [10] and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [11]. Human clinical studies show that elevated plasma Hcy is a risk factor for dementia and AD and that Hcy lowering by B-vitamin treatment slows the rate of brain atrophy [12].

Serum paraoxonase 1 (Pon1) is synthesized exclusively in the liver and attached to high-density lipoproteins (HDL) in the blood, but recent studies demonstrate that Pon1 is also present in the brain [13]. Pon1 protects against high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice [14] and humans [15]. N-homocysteinylated forms of HDL [16] and ApoA1 [17] have been detected in human plasma in vivo. In vitro, N-homocysteinylation of HDL and Pon1 causes a loss of function [18]. In humans, Pon1 is implicated in AD. For example, low serum Pon1 activity is a risk factor for dementia [19] and AD [20, 21], while Hcy is a negative determinant of Pon1 activity [22, 23] and a risk factor for AD [12].

HDL and purified Pon1 protein have the ability to hydrolyze Hcy-thiolactone in vitro [24], but whether this reflects a physiological function was unknown. Intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of Hcy-thiolactone are acutely neurotoxic and have been extensively used to define mechanism of seizures in mice [25, 26] and rats [27, 28]. To gain insight into a role of Pon1 in Hcy-thiolactone metabolism and brain disease, we exploited the Pon1−/− mouse [14] and the i.p., Hcy-thiolactone injection models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and diet

Knockout Pon1−/− mice on the C57BL/6J background [14] and wild type Pon1+/+ littermates were maintained on a rodent chow (LabDiet 5010, Purina Mills Intl, St. Louis, MO). To induce hyperhomocysteinemia, 4-weeks-old mice were provided 1% Met in drinking water for 8 weeks [29]. Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the New Jersey Medical School.

Mouse plasma and urine

The blood was collected by cheek vein puncture into EDTA tubes and chilled on ice. Plasma was separated and stored at −80°C. Urine was collected at about 2 h intervals for a period of 24-h, each portion chilled on ice and stored at −80°C.

Hcy-thiolactone and Hcy turnover

L-Hcy-thiolactone dissolved in PBS was injected i.p., into 4-12-week-old mice (40-600 nmol/g body weight). The mice were bled 5, 10, 20, and 30 min (for Hcy-thiolactone assays) or 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90 min (for Hcy assays) after injection. EDTA-Plasma samples were stored at −80°C before assay.

Hcy-thiolactone toxicity

L-Hcy-thiolactone dissolved in PBS was injected i.p., into 4-5 week-old mice (3,700 nmol/g body weight). Mice were placed on the top of a plastic cage and observed for behavioral manifestations for 90 min. This was assessed by the incidence and latency of seizures and death as previously described [25, 26].

Hcy-thiolactone and total Hcy assays

Hcy-thiolactone and total Hcy were quantified by HPLC-based methods using post-column derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde and fluorescence detection as previously described [30, 31].

RESULTS

Inactivation of Pon1 elevates brain Hcy-thiolactone

We found that Hcy-thiolactone levels were significantly elevated in brains of Pon1−/− mice, in comparison with Pon1+/+ animals (Table 1). However, Hcy-thiolactone levels in heart, kidney, liver, lung, spleen, and plasma were not significantly affected by the inactivation of Pon1 gene (Table 1). The elevation of Hcy-thiolactone could be due to effects of Pon1 on Hcy levels. To test this possibility, we assayed brain total Hcy. We found that brain tHcy levels were similar in Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice, 46.4 ± 13.4 and 59.7 ± 18.3 pmol/mg tissue, respectively. Thus, the increase in Hcy-thiolactone levels observed in Pon1−/− mice is caused by inactivation of the Pon1 gene, and not by its effects on Hcy metabolism.

Table 1.

Tissue levels of Hcy-thiolactone in Pon1−/− and wild type mice

| Genotype (n) | Hcy-thiolactone, pmol/mg tissue | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | Heart | Kidney | Liver | Lung | Spleen | Plasma | |

| Pon1−l− (4) | 0.51 ± 0.13* | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.13 | 0.076 ± 0.047 | |

| Wild type (6) | 0.33 ± 0.15 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.50 ± 0.27 | <0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.13 | 0.12 ± 0.14 | 0.112 ± 0.078 |

Significantly increased versus wild type: T-test: p = 0.047.

Pon1−/− mice excrete more Hcy-tiolactone than wild type animals

Most of Hcy-thiolactone produced in the human [31] or mouse [4] body is excreted in urine. To facilitate quantification of urinary Hcy-thiolactone, we induced hyperhomocysteinemia by providing Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice with 1% Met in drinking water for 8 weeks. The consumption of Met-supplemented water (3.1 mL/mouse) was not affected by Pon1 genotype. Plasma tHcy levels in Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice fed with Met-supplemented drinking water were elevated 5.6- and 10.4-fold (to 48 ± 16 μM, and 77 45 μM, respectively, from a basal level of 8.5 ± 1.9 μM and 7.4 2.2 ± μM, respectively), in mice that ± drank non-supplemented water. 24-h urine was collected for Hcy-thiolactone quantification from Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice. We found that Pon1−/− mice excreted 2.4-fold more Hcy-thiolactone in 24-h urine than Pon1+/+ animals (Table 2). In contrast, urinary tHcy levels were similar in Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice. Unexpectedly, we found that Pon1−/− mice generated more urine than wild type animals, suggesting that Pon1 might be involved in the regulation of kidney function, which warrants investigation in future studies.

Table 2.

Urinary Hcy-thiolactone and total Hcy output in Pon1−/− and wild type mice. The mice were fed with a 1% Met-supplemented drinking water for 8 weeks. Consumption of Met-supplemented water (3.1 mL/ mouse) was not affected by the genotype

| Genotype (n) | Urinary Hcy-thiolactone, nmol/24 h |

Urinary tHcy, nmol/24 h |

Urine volume, mL/24 h |

Mouse body weight, g |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pon1−l− (4) | 3.2 ± 0.5* | 1004 ± 207 | 1.24 ± 0.19* | 23.4 ± 1.4 |

| Wild type (9) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 817±231 | 0.58 ± 0.14 | 21.4 ± 0.7 |

Significantly increased versus wild type: p < 0.001.

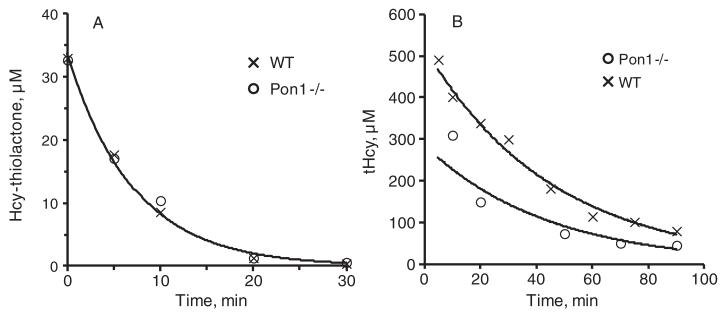

Turnover of plasma Hcy-thiolactone in vivo

To determine how Pon1 affects its turnover in vivo, L-Hcy-thiolactone was injected i.p. into Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice, and Hcy-thiolactone kinetics in plasma were monitored. We used a non-toxic dose of 600 nmol L-Hcy-thiolactone/g body weight in most experiments, but similar results were obtained with doses as low as 40 nmol/g body weight. The highest Hcy-thiolactone levels were observed at 5 min post-injection and were not affected by Pon1 status (Fig. 1A). This shows that in Pon1−/− mice Hcy-thiolactone metabolism is not impaired during its transit from the intraperitoneal cavity to the bloodstream and suggests that Pon1 has a negligible contribution to Hcy-thiolactone turnover in membranes surrounding the intraperitoneal cavity.

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of plasma Hcy-thiolactone and total Hcy in mice. Representative kinetics of Hcy-thiolactone (A) and tHcy (B) turnover obtained for individual Pon1−/− (○) and Pon1+/+(x) mice injected intraperitoneally with 600 nmol L-Hcy-thiolactone/g body weight are shown. Data points were fitted to the exponential equation [At] = [A0]· e−k·t, where k is a first order rate constant, [At] and [A0] are measured concentrations at time t and extrapolated concentrations at time zero, respectively.

Because of its exceptionally low pK = 6.7 [32], Hcy-thiolactone is mostly neutral under physiological conditions and freely diffuses through cell membranes and is found in extracellular media [33, 34]. Assuming that the i.p.,-injected Hcy-thiolactone distributes uniformly throughout the body and that blood constitutes 8% of the mouse body weight, plasma Hcy-thiolactone extrapolated to time zero (HTL0, Table 3) represents 6.6% or 5.9% of the dose injected into Pon1−/− or Pon1+/+ mice, respectively.

Table 3.

Turnover of Hcy-thiolactone and total Hcy in mouse blood in vivo. L-Hcy-thiolactone was injected i.p. (600nmol/g body weight). Half-lives (t0.5 = 0.69/k) and plasma concentrations at time zero (HTL 0, tHcy0) were calculated from the plasma concentrations at time t (HTLt, tHcyt) according to the equation [HTLt] = [HTL0]·e−k·t or [tHcyt ]= [tHcy0 ] ·e−k·t , where k is a first order rate constant

| Genotype | Diet | HTL0, μM | HTL t0.5, min (n) | tHcy0, μM | tHcy t0.5, min (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pon1 −/− | Control | 34.1 ± 9.5 | 5.9 ± 1.2(6) | 256 ± 23 | 27.1 ± 6.3 (4) |

| Wild type | Control | 39.0 ± 13.9 | 5.0 ± 0.9 (15) | 524±136 | 26.2 ± 2.6 (5) |

Hcy-thiolactone gradually decreased with exponential kinetics, approaching basal level at 30 min post-injection (Fig. 1A). Plasma Hcy-thiolactone half-life was similar in Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice, 5.9 ± 1.2 min and 5.0 ± 0.9 min, respectively (Table 3), suggesting that Pon1 does not significantly contribute to Hcy-thiolactone clearance from the blood.

Half-lives of Hcy-thiolactone in serum from Pon1+/+ and Pon1−/− mice were 73 min and >1000 min, respectively, >10-fold longer than the in vivo value of about 5 min (Table 3). These values suggest that Pon1 contributes at most 10% to Hcy-thiolactone clearance from the mouse blood in vivo.

Plasma total Hcy kinetics in vivo

In Pon1+/+ mice i.p.,-injected with L-Hcy-thiolactone (600 nmol/g body weight), plasma total Hcy increased to 524 ± 136 μM (extrapolated level at time zero; Fig. 1B, Table 3) from a basal level of 7.4 ± 2.2 μM. This shows that Hcy-thiolactone was metabolized to Hcy. In Pon1−/− mice injected with identical dose of L-Hcy-thiolactone, plasma total Hcy increased to 256 ± 23 μM (Table 3). The lower post-injection total Hcy levels, suggest that excess Hcy is metabolized (to Met and/or Cys) faster in Pon1−/− than in Pon1+/+ mice. Post-injection plasma total Hcy gradually declined with exponential kinetics and similar half-lives in Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice, 27.1 ± 6.3 min and 26.2 2.6 min, respectively (Table 3). Overall, the clearance ± of plasma total Hcy was about 5-times slower than the clearance of plasma Hcy-thiolactone.

Pon1 protects against Hcy-thiolactone neurooxicity

L-Hcy-thiolactone is known to be toxic to rodents [25]. For example, in C3H mice, LD50 and LD10 are 2,540 and 2,390 nmol Hcy-thiolactone/g body weight, respectively [26]. We found that i.p., injections of L-Hcy-thiolactone at a dose of 3,700 nmol/g body weight induced seizures and death in 29.5% and 2.3% of Pon1+/+ C57BL/6J mice (Table 4). Doses from 40 to 2,850 nmol/g mouse body weight were nontoxic.

Table 4.

Pon1 protects against Hcy-thiolactone neurotoxicity in mice. L-Hcy-thiolactone was injected i.p. (3,700 nmol/g body weight) and the mice were monitored for 90 min

| Genotype (n) | Incidence of seizures, % (n) |

Incidence of death, % |

Seizure latency period, min |

Death latency period, min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pon1−/− (36) | 52.8 (19)* | 8.3 (3) | 31.8±11.6‡ | 50±30 |

| Wild type (44) | 29.5 (13) | 2.3 (1) | 41.2±10.8 | 61 |

Significantly different from wild type – Fisher exact test p = 0.042 versus wild type

T-test p = 0.019 versus wild type.

Following L-Hcy-thiolactone injection (3,700 nmol/g body weight), essentially all mice became somnolescent at 5-10 min post-injection. Convulsions, characterized by spontaneous tonic-clonic, grand-mal seizures (Kangaroo position, extension of fore and hind limbs and tail, status epilepticus), and running fits occurred within 50 min. The incidence of seizures significantly increased in Pon1−/− mice, to 52.8% (p = 0.042, Table 4). Seizure latency (i.e., time to first seizure) was significantly shorter for Pon1−/− mice compared with Pon1+/+ animals (31.8 min versus 41.2 min, p = 0.019). Only one Pon1+/+ mouse, out of 44 (2.3%), died (at 61 min) after L-Hcy-thiolactone injection. As also shown in Table 4, the incidence of death increased in Pon1−/− mice (to 8.3%) but it was not significantly different from the incidence of death in Pon1+/+ mice (2.3%), most likely due to small number of animals. Because both Pon1+/+ and Pon1−/− mice are on identical C57BL/6J background, these differences are caused by the Pon1 gene inactivation and indicate that Pon1 protects against the toxicity caused by Hcy-thiolactone.

We assayed brain Hcy-thiolactone, N-Hcy-protein, and total Hcy 90 min post injection. We found that Hcy-thiolactone and N-Hcy-protein levels were higher in Pon1−/− than in Pon1+/+ mice (3.4 1.1 ± 1.5 versus ± ± 0.1 pmol/mg brain, p = 0.029, and 48.2 7.7 versus 32.4 ± 6.4 pmol/mg brain, p = 0.010, respectively). The post-injection brain total Hcy levels in Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice were not significantly different (425 ± 99 μM versus 634 ± 214 pmol/mg brain).

DISCUSSION

The physiological function of Pon1 and its role in brain disease are not fully understood. The present work using the Pon1 knockout mice provides the first direct evidence that 1) Pon1 metabolizes L-Hcy-thiolactone to Hcy in vivo, and 2) that a specific Hcy metabolite, Hcy-thiolactone, rather than Hcy itself is neurotoxic in mice. These findings suggest a mechanism by which Pon1 can protect against neurodegeneration associated with hyperhomocysteinemia and AD.

Our data also indicate that, although Hcy-thiolactone is present in most mouse organs examined, Pon1 significantly contributes to Hcy-thiolactone metabolism mainly in the brain, and that the brain appears to be a major source of urinary Hcy-thiolactone excreted by Pon1−/− mice. This is consistent with recent data showing that Pon1 is present in the brain [13]. However, the relatively modest and brain-specific increases in Hcy-thiolactone levels in Pon1−/− mice suggest that, in addition to Pon1, other enzyme(s) or mechanisms, which remain to be identified, contribute to Hcy-thiolactone turnover in mice. This conclusion is supported by our present findings showing that Hcy-thiolactone is cleared in vivo from the mouse blood 15-times faster (t0.5 = 5 min) than it is hydrolyzed by Pon1 in vitro in serum (t0.5 = 73 min), and that the Pon1 gene inactivation does not significantly affect the in vivo Hcy-thiolactone clearance (t0.5 = 5.9 min; Table 3).

Acute injections of Hcy-thiolactone are known to cause epileptic seizures in mice [26] and rats [25]. An underlying mechanism may involve the inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase, critical for normal brain function, by Hcy-thiolactone, which would contribute to the seizures. Indeed, the Na+/K+-ATPase activity was reported to be greatly diminished by acute injections of Hcy-thiolactone, but not Hcy [28]. Our present data, showing that the inactivation of Pon1 gene increases the incidence and decreases the latency of seizures, provide the first genetic evidence that Pon1 protects against Hcy-thiolactone toxicity in mice.

Genetic hyperhomocysteinemia causes neurological abnormalities in humans, manifested by seizures and mental retardation [1]. In a general population, elevated Hcy is a risk factor for dementia and AD [11]. However, it was not known whether Hcy itself or any of its metabolites is responsible for the Hcy-associated neurotoxicity. Using a mouse model with a genetic deficiency in Hcy-thiolactone disposition, Pon1−/−, allowed us to examine the role of Pon1 in the brain pathology caused by acute hyperhomocysteinemia. Findings of the present work, showing that the Pon1 gene inactivation increases the incidence and decreases the latency of seizures induced by i.p., injections of Hcy-thiolactone in mice, provide the first evidence that Hcy-thiolactone is neurotoxic in vivo. Elevated post-injection levels of N-Hcy-protein in the brain suggest that the mechanism of Hcy-thiolactone-induced neurotoxicity involves N-homocysteinylation of brain proteins. Although in our experimental model Hcy was also generated, post-injection Hcy levels are not significantly different in Pon1−/− and Pon1+/+ mice, and do not explain the observed toxicity. Thus, in this model neurotoxicity can be assigned to Hcy-thiolactone, but not to Hcy.

It should be noted that the concentrations of Hcy-thiolactone used in our acute injection experiments greatly exceed physiological concentrations. Such high concentrations, required due to a very efficient metabolism of Hcy-thiolactone in the mouse, caused extreme neurological manifestations within 30-60 minutes. Although much lower Hcy-thiolactone concentrations occur in pathological hyperhomocysteinemia [4], it is likely that under chronic exposure even small amounts of damage caused by Hcy-thiolactone can accumulate to significant levels over extended period of time that is usually required for the development of brain damage, such as observed in AD [12]. Consistent with this scenario is a recent finding showing that the reduced Hcy-thiolactonase activity is linked to the pathology of AD [11].

In conclusion, using the Pon1−/− mice, we provide the first direct evidence that Hcy-thiolactone, rather than Hcy itself is neurotoxic in vivo. Our findings indicate that Pon1 protects mice against the neurotoxicity of Hcy-thiolactone by hydrolyzing it in the brain, suggest a mechanism by which Pon1 can protect against neurodegeneration associated with hyperhomocysteinemia and AD, and provide basis for future studies of Pon1’s role in AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the American Heart Association (0855919D,12GRNT9420014) and the National Science Center, Poland (DEC-2011/01/B/NZ1/03417).

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://www.j-alz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=1162).

REFERENCES

- [1].Mudd SH, Levy HL, Krauss JP. Disorders of transsulfuration. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. Mc Graw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 2007–2056. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jakubowski H, Goldman E. Synthesis of homocysteine thiolactone by methionyl-tRNA synthetase in cultured mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 1993;317:237–240. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jakubowski H. Protein homocysteinylation: Possible mechanism underlying pathological consequences of elevated homocysteine levels. FASEB J. 1999;13:2277–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chwatko G, Boers GH, Strauss KA, Shih DM, Jakubowski H. Mutations in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase or cystathionine beta-synthase gene, or a high-methionine diet, increase homocysteine thiolactone levels in humans and mice. FASEB J. 2007;21:1707–1713. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7435com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jakubowski H, Boers GH, Strauss KA. Mutations in cystathionine beta-synthase or methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene increase N-homocysteinylated protein levels in humans. FASEB J. 2008;22:4071–4076. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jakubowski H, Perla-Kajan J, Finnell RH, Cabrera RM, Wang H, Gupta S, Kruger WD, Kraus JP, Shih DM. Genetic or nutritional disorders in homocysteine or folate metabolism increase protein N-homocysteinylation in mice. FASEB J. 2009;23:1721–1727. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-127548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Glowacki R, Jakubowski H. Cross-talk between Cys34 and lysine residues in human serum albumin revealed by N-homocysteinylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10864–10871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sibrian-Vazquez M, Escobedo JO, Lim S, Samoei GK, Strongin RM. Homocystamides promote free-radical and oxidative damage to proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:551–554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909737107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Paoli P, Sbrana F, Tiribilli B, Caselli A, Pantera B, Cirri P, De Donatis A, Formigli L, Nosi D, Manao G, Camici G, Ramponi G. Protein N-homocysteinylation induces the formation of toxic amyloid-like protofibrils. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:889–907. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Perla-Kajan J, Stanger O, Luczak M, Ziolkowska A, Malendowicz LK, Twardowski T, Lhotak S, Austin RC, Jakubowski H. Immunohistochemical detection of N-homocysteinylated proteins in humans and mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008;62:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Suszynska J, Tisonczyk J, Lee HG, Smith MA, Jakubowski H. Reduced homocysteine-thiolactonase activity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:1177–1183. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smith AD, Smith SM, de Jager CA, Whitbread P, Johnston C, Agacinski G, Oulhaj A, Bradley KM, Jacoby R, Refsum H. Homocysteine-lowering by B vitamins slows the rate of accelerated brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Marsillach J, Mackness B, Mackness M, Riu F, Beltran R, Joven J, Camps J. Immunohistochemical analysis of paraoxonases-1, 2, and 3 expression in normal mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shih DM, Gu L, Xia YR, Navab M, Li WF, Hama S, Castellani LW, Furlong CE, Costa LG, Fogelman AM, Lusis AJ. Mice lacking serum paraoxonase are susceptible to organophosphate toxicity and atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:284–287. doi: 10.1038/28406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bhattacharyya T, Nicholls SJ, Topol EJ, Zhang RL, Yang X, Schmitt D, Fu XM, Shao MY, Brennan DM, Ellis SG, Brennan ML, Allayee H, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Relationship of paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene polymorphisms and functional activity with systemic oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk. JAMA. 2008;299:1265–1276. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jakubowski H. Homocysteine is a protein amino acid in humans. Implications for homocysteine-linked disease. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30425–30428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ishimine N, Usami Y, Nogi S, Sumida T, Kurihara Y, Matsuda K, Nakamura K, Yamauchi K, Okumura N, Tozuka M. Identification of N-homocysteinylated apolipoprotein AI in normal human serum. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47:453–459. doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.010035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Marotti E, Curatola G. Effect of homocysteinylation on human high-density lipoproteins: A correlation with paraoxonase activity. Metabolism. 2003;52:146–151. doi: 10.1053/meta.2003.50033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dantoine TF, Debord J, Merle L, Lacroix-Ramiandrisoa H, Bourzeix L, Charmes JP. Paraoxonase 1 activity: A new vascular marker of dementia? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:96–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Paragh G, Balla P, Katona E, Seres I, Egerhazi A, Degrell I. Serum paraoxonase activity changes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;252:63–67. doi: 10.1007/s004060200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Erlich PM, Lunetta KL, Cupples LA, Abraham CR, Green RC, Baldwin CT, Farrer LA. Serum paraoxonase activity is associated with variants in the PON gene cluster and risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.08.003. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lacinski M, Skorupski W, Cieslinski A, Sokolowska J, Trzeciak WH, Jakubowski H. Determinants of homocysteine-thiolactonase activity of the paraoxonase-1 (PON1) protein in humans. Cell Mol Biol. 2004;50:885–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wehr H, Bednarska-Makaruk M, Graban A, Lipczynska-Lojkowska W, Rodo M, Bochynska A, Ryglewicz D. Paraoxonase activity and dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2009;283:107–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jakubowski H. The role of paraoxonase 1 in the detoxification of homocysteine thiolactone. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;660:113–127. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-350-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sprince H, Parker CM, Josephs JA, Jr, Magazino J. Convulsant activity of homocysteine and other short-chainmercaptoacids: Protection therefrom. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1969;166:323–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb46402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Spence AM, Rasey JS, Dwyer-Hansen L, Grunbaum Z, Livesey J, Chin L, Nelson N, Stein D, Krohn KA, Ali-Osman F. Toxicity, biodistribution and radioprotective capacity of L-homocysteine thiolactone in CNS tissues and tumors in rodents: Comparison with prior results with phosphorothioates. Radiother Oncol. 1995;35:216–226. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(95)01543-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Folbergrova J. Anticonvulsant action of both NMDA and non-NMDA receptor antagonists against seizures induced by homocysteine in immature rats. Exp Neurol. 1997;145:442–450. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rasic-Markovic A, Stanojlovic O, Hrncic D, Krstic D, Colovic M, Susic V, Radosavljevic T, Djuric D. The activity of erythrocyte and brain Na+/K+ and Mg2+-ATPases in rats subjected to acute homocysteine and homocysteine thiolactone administration. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;327:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Velez-Carrasco W, Merkel M, Twiss CO, Smith JD. Dietary methionine effects on plasma homocysteine and HDL metabolism in mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chwatko G, Jakubowski H. The determination of homocysteine-thiolactone in human plasma. Anal Biochem. 2005;337:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chwatko G, Jakubowski H. Urinary excretion of homocysteine-thiolactone in humans. Clin Chem. 2005;51:408–415. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.042531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jakubowski H. Mechanism of the condensation of homocysteine thiolactone with aldehydes. Chemistry. 2006;12:8039–8043. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jakubowski H. Metabolism of homocysteine thiolactone in human cell cultures. Possible mechanism for pathological consequences of elevated homocysteine levels. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1935–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jakubowski H, Zhang L, Bardeguez A, Aviv A. Homocysteine thiolactone and protein homocysteinylation in human endothelial cells: Implications for atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2000;87:45–51. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]