Abstract

To recognize an object, it is widely supposed that we first detect and then combine its features. Familiar objects are recognized effortlessly, but unfamiliar objects—like new faces or foreign-language letters—are hard to distinguish and must be learned through practice. Here, we describe a method that separates detection and combination and reveals how each improves as the observer learns. We dissociate the steps by two independent manipulations: For each step, we do or do not provide a bionic crutch that performs it optimally. Thus, the two steps may be performed solely by the human, solely by the crutches, or cooperatively, when the human takes one step and a crutch takes the other. The crutches reveal a double dissociation between detecting and combining. Relative to the two-step ideal, the human observer’s overall efficiency for unconstrained identification equals the product of the efficiencies with which the human performs the steps separately. The two-step strategy is inefficient: Constraining the ideal to take two steps roughly halves its identification efficiency. In contrast, we find that humans constrained to take two steps perform just as well as when unconstrained, which suggests that they normally take two steps. Measuring threshold contrast (the faintness of a barely identifiable letter) as it improves with practice, we find that detection is inefficient and learned slowly. Combining is learned at a rate that is 4× higher and, after 1,000 trials, 7× more efficient. This difference explains much of the diversity of rates reported in perceptual learning studies, including effects of complexity and familiarity.

Keywords: object recognition, sensitivity, letter identification

The world is full of objects, and we spend our lives identifying them. Reading an hour a day for a year means identifying millions of letters and words. Each letter is a good basic-level object: simple, common, useful, and with its own name and shape (1–4). Identifying a letter requires two steps of visual processing: the observer first detects the letter’s features and then combines them to recognize the letter (5).

However, what is a feature? Interpretation of learning studies that use traditional letters and other everyday objects is hindered by the infinite number of possible features, which include physical properties, like size and shape, as well as abstract properties, like function and beauty (6–8). To avoid this morass, we narrowly define features as discrete components of an image that are detected independently of each other (5).

When letters share features (perhaps, the vertical bar in a D and an L), detecting one feature is not always enough to tell which letter it is, so multiple features must be detected and combined for reliable identification. Both steps—detection and combination—are liable to errors that impede identification. For example, if a letter is faint or seen in dim light, a reader may incorrectly identify it because she fails to detect a feature that is present or because she spuriously “detects” a feature that is absent. Identifying an unfamiliar letter can be difficult even when all of its features have been correctly detected. For example, a novice reader may mistakenly identify a plainly visible letter, confusing the shape of one for that of another.

Whether struggling to detect or to combine, with more practice, observers fail less. They learn. Feature detection and combination can both be learned through practice (9–11).

To study features, it is helpful to use Gabors. A Gabor is a grating patch that is made by vignetting a sinusoidal grating with a Gaussian window, which restricts its spatial extent to a few bars  . Gabors are fairly well matched to the receptive fields of simple cells in the primary visual cortex measured physiologically, and to the tuning of spatial frequency channels measured psychophysically. Gabors can differ in position, orientation, and spatial frequency. If Gabors are sufficiently different along these dimensions, they are detected independently and can be distinguished by a single feature detection (12, 13). Practice improves detection of a Gabor (14). This learning is specific to the trained stimulus and location (15, 16).

. Gabors are fairly well matched to the receptive fields of simple cells in the primary visual cortex measured physiologically, and to the tuning of spatial frequency channels measured psychophysically. Gabors can differ in position, orientation, and spatial frequency. If Gabors are sufficiently different along these dimensions, they are detected independently and can be distinguished by a single feature detection (12, 13). Practice improves detection of a Gabor (14). This learning is specific to the trained stimulus and location (15, 16).

Tasks requiring feature combination also improve with practice. Merely detecting the presence of an object does not require combining its features, but identifying it usually does; this is because detecting any feature reveals the object’s presence, but, depending on the other possible objects, usually several features are needed to specify which object is present. Fine and Jacobs (17) measured improvement with practice in identifying compound gratings, which are multifeature objects composed of several superimposed Gabors, and found that learning transferred across orientations, unlike learning in detection tasks. Likewise, Kovács et al. (18) measured improvement of search for orientation-defined contours and found that learning transferred between eyes and to other orientation-defined contours, again unlike learning in detection tasks.

There are hints that the two steps, detection and combination, may be learned at different rates. Learning of familiar letters is slow and has been attributed to improved feature detection (19). Unlike the slow learning of familiar letters, the learning of new letters is initially fast, but slows as the letters become familiar (5, 20–22). This learning might involve improvement at either step. Identification involves both detecting and combining of features, so, when identification performance improves, one would like to know how much of this learning is due to improved detection rather than improved combination of features.

Here, through the use of six variously enhanced observers performing the same letter-identification task, we dissociate detecting and combining, revealing each step’s contribution to learning. Of the six kinds of observer, two are “unconstrained” and four are “composite.” Unconstrained is the traditional situation of presenting a faint target and asking the observer to identify it, with no constraints. We test both the human (H) and the ideal (I) observer in this way. The ideal is an algorithm that chooses the most probable hypothesis, maximizing expected accuracy. Composite observers are new. Of the four composite observers, two are bionic. They are human in only one of the steps. The other step is delegated to a bionic crutch, either the ideal detector or the ideal combiner. In these two cases, the two perform as a team: Either the human combines what the ideal detects (composite IH), or the ideal combines what the human detects (composite HI). Having broken up the task into two parts, we can also assign both parts, in distinct sessions, to the same observer, so that the human (composite HH) or the ideal (composite II) takes both steps. The bionic crutches test for double dissociation: Is the human identification process actually separable into two distinct steps of detection and identification?

Are the bionic crutches overkill? Is it not enough, for our purpose, just to note the different learning rates for tasks that do and do not require combining? No. That comparison is suggestive, but has not led to any published conclusions about distinct learning rates in separate stages. Each task yields a rate, but no one has managed to link the task and the model strongly enough to draw conclusions that distinguish the two kinds of learning in one model. Adding to the confusion, much of the perceptual learning results are for fine discrimination of one feature, like orientation, which may require combining the activity of several feature detectors, but has usually been taken to reflect learning at an early stage. Our bionic crutches provide a double-dissociation paradigm that rises above these vagaries, showing how the observed pattern of results is diagnostic evidence for independent processes. Our paradigm requires manipulations (the bionic crutches) that selectively affect the two presumed processes. The strong conclusion is well worth the bother.

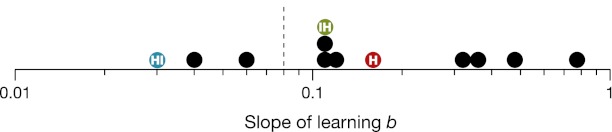

To separate the steps, we need to know the letters’ features; they are uncertain for traditional letters, so we use Gabor letters instead (Fig. 1). Based on the probability summation literature, we suppose that our Gabors are features, detected independently (12, 13). The juxtaposition of n Gabors creates an n-feature “letter” (23, 24). Incidentally, though Gabors are very well-suited to be the elements of our stimuli, they are not essential; simple bars might do as well. By using Gabor (or bar) letters, we can precisely specify the features that constitute each letter, while maintaining the essence of an alphabet: a set of many distinguishable objects sharing a common visual style. Our Gabor letters are similar to Braille letters in that they each consist of a binary array of features. Braille behaves well when presented visually (5, 25). Even so, the conclusions of this paper do not depend on our claim that Gabor “letters” are letters; it is enough that they are objects.

Fig. 1.

Eight Gabor letters. The letters of the IndyEighteen alphabet are composed of Gabors. Each of the 18 possible Gabors is oriented ±45° from vertical and is at one of nine locations in a 3 × 3 grid. When a right-tilted and a left-tilted Gabor coincide, they form a plaid, but vision still responds to them independently. We suppose that the Gabors are detected independently, so that each Gabor is a feature. With two orientations and nine locations, there are 18 possible Gabors, i.e., features. The eight letters displayed here are a randomly selected subset of the 218 letters in the whole alphabet. Note that within this subset, some features are common to many letters (e.g., six of the eight letters contain a right-tilted Gabor at the top right corner), whereas some features are common to just a few (e.g., two of the eight letters contain a right-tilted Gabor at the bottom left position).

We created the IndyEighteen alphabet. In general, an IndyN alphabet is the set of all possible combinations of N features. Suppose we are asked to identify a randomly selected letter from this alphabet of 2N letters. Because the presence of each feature is statistically independent of the rest, all N features must be detected to identify the letter reliably. In most traditional alphabets, however, a letter can be identified without detecting all of its features.* To better match this property of traditional alphabets, we created several eight-letter subsets drawn randomly from IndyEighteen. One such subset appears in Fig. 1. Reducing the number of possible letters makes identification easier. In general, in a subset of Indy, the features are no longer independent or equally frequent, so fewer feature detections are needed for identification, and some features are less informative than others. At the extremes, a feature may be unique to a letter and thus diagnostic of its identity, or common to all of the letters and thus irrelevant to the task of distinguishing among them (26).†

For each unconstrained or composite observer, we create a new alphabet consisting of eight IndyEighteen letters. On each trial, we ask the observer to identify a letter drawn from that eight-letter alphabet. We measure threshold contrast, the lowest contrast (faintness) sufficient to identify the letters correctly 75% of the time. We then convert threshold contrast to efficiency. Efficiency is a useful way to characterize performance of a computational task (27, 28); this pits the actual observer against the ideal observer, an algorithm that performs the whole task optimally, not constrained to taking two steps. Efficiency is defined as the fraction of the signal energy used by an observer that is required by the ideal to perform just as well. Contrast energy is proportional to the contrast squared, so the efficiency of the actual observer is

|

where c and cI are threshold contrasts of the actual and ideal observers.

Results

Dissociating Detecting from Combining.

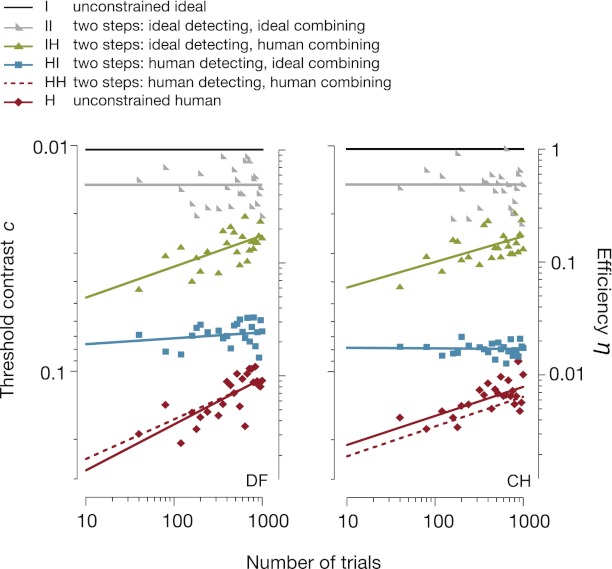

Fig. 2 shows learning for two participants, plotting threshold contrast as a function of the number of completed identification trials. (Results for all six participants appear in Fig. S1.) The right-hand vertical scale shows the efficiency corresponding to each threshold contrast. There are two graphs (Fig. 2, Left and Right), one per participant. Within each graph appear all results for that participant, unconstrained and composite. The top line (Fig. 2, solid black line) is the unconstrained ideal (I), the baseline for calculating efficiency. The bottom solid line is the unconstrained human. The other four lines, sandwiched in between, are for composites. Solid lines are fits to data, and the dashed line is a prediction derived from the other lines (Eq. 3). The vertical positions of the lines show that threshold contrast (and efficiency) are best for the unconstrained ideal, slightly worse for the two bionic crutches working together, and get worse, from line to line, as we ask the human to do part or all of the work (Fig. 2, bottom solid line). At trial 1,000, the composite-observer efficiency with the human doing just the combining (IH, 15%) is 7× that with the human doing just the detecting (HI, 2.1%). The lines in which the human does the combining (H, HH, and IH) are steep, showing fast learning, and the rest (I, II, HI) are shallow. The log-log slope of pure combination learning (IH, −0.11 ± 0.01; Fig. 2, green triangles) is 4× that for pure detection learning (HI, −0.03 ± 0.01, blue squares). The reported slopes and efficiencies are averages across all participants. (As a control, four of the participants used a modified version of the bionic crutch with independent detection trials, as described in Supporting Materials and Methods, Composite HI′.)

Fig. 2.

Learning. The participant (DF, Left; CH, Right) detects and combines features to identify a letter from an alphabet of eight different IndyEighteen letters. Each unconstrained or composite observer trained at threshold contrast, receiving just enough contrast to achieve criterion performance (75% correct). Each line shows an unconstrained or composite observer’s threshold contrast c (using the contrast scale, Left) and efficiency η (using the efficiency scale, Right). The bottom solid line is the unconstrained human (H), and the top line is the unconstrained ideal (I). The dashed line is the composite human (HH). Separability of the two steps predicts that the unconstrained and composite observers will perform equally, which is approximately true for the human H and HH (bottom two lines, solid and dashed) and is not true of the ideal I II (top two lines). The horizontal scale counts identification trials. For composite HI, the human performs 18 detection trials for each identification trial. In both vertical scales, learning goes up: efficiency increases upward and threshold contrast increases downward. Because efficiency is inversely proportional to threshold contrast squared (Eq. 1), the log-log slope of efficiency is −2× that of threshold contrast.

Does the unconstrained human really take two steps, first detecting and then combining? That is an inefficient way to identify. Constraining the ideal to take two steps roughly halves its efficiency, ηII ∼ 0.5ηI, resulting in the gap between the upper two lines in Fig. 2. However, constraining humans to take two steps leaves their efficiency unchanged, ηHH ∼ ηH. This is the coincidence of the dashed and solid lines at the bottom of Fig. 2, which do not differ significantly from each other in slope or intercept across participants (paired t test, P = 0.15 and P = 0.92, respectively). Forcing people to take two steps does not impair their performance, which suggests that taking two steps may be an intrinsic limitation of human object recognition.

Do the bionic crutches really isolate the contributions to human performance of two distinct processes? More precisely, does each crutch boost efficiency by a multiplicative factor (Eq. 2)? In short, are the steps separable? That conjecture is tested and verified by the agreement of the two-step and unconstrained human performance (H and HH, dashed and solid lines at the bottom of Fig. 2). Thus, we have dissociated the contribution of each step (29); in the language of dissociation studies, this is a within-task process decomposition with a multiplicative composite measure: efficiency. The task is letter identification; the provision of each bionic crutch—detector or combiner—is an independent manipulation. Finding this double dissociation of detecting and combining shows that object recognition “is accomplished by a complex process that contains two functionally distinct and separately modifiable parts” (ref. 29, p. 180).

The bionic crutch paradigm can be applied to any observer, biological or not. However, the results are particularly easy to interpret when a double dissociation is revealed, as we found for the humans, but not for the ideal: the human observer’s internal computation really is separable into detection and combination steps, with the overall efficiency equal to the product of the efficiencies of the steps (Eq. 3).

Efficiency for identifying a letter or a word is inversely proportional to complexity or word length (3, 5). Wondering why, it has seemed obvious that the low overall human efficiency for identifying a word (e.g., 1% for a short word) is mostly due to the two-step strategy that detects the parts independently before combining for identification. Supposing that vision is mediated by feature detection seems to imply that each feature must reach threshold by itself, and this applies equally to the letters in a word and the features in a letter. Thus, it once seemed to us that humans are inefficient mostly because of the inefficiency of taking two steps. With this background, perhaps the reader will share our surprise in discovering, through Monte Carlo trials, that the ideal two-step strategy has a respectable efficiency of at least 65% for any number of parts. We are astounded that the cost of reducing each feature’s sensory information to a bit has such a modest effect on overall efficiency. Thus, the mere fact of taking two steps does not doom the combining efficiency to fall inversely with complexity, as the human’s does. Perhaps the human drop in combining efficiency is due to a limit in the number of features that the observer combines, say 7 ± 2, as indicated by the ratio of thresholds for identification and detection (5).‡

Comparing Slopes to Explain Effects of Familiarity and Complexity on Learning.

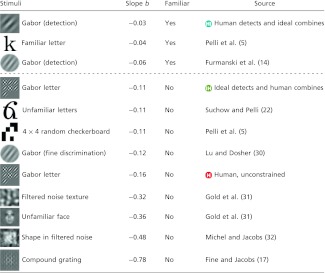

The shallow slope of detection learning, over 1,000 trials, matches that of other detection-learning studies, which show slow learning over many sessions. Twelve slopes of learning curves, from this study and seven other published papers, are displayed in Table 1 and Fig. 3 (5, 13, 16, 21, 30–32). We limit our survey to studies that report threshold contrasts for tasks that demand discrimination of objects and patterns presented in central vision, at fixation.

Table 1.

Slope of detection and identification learning in various experiments reported here and in seven other published papers

|

Plotting threshold contrast as a function of the number of completed trials, we fit parameter b, the log-log slope. The dashed line separates the familiar from the unfamiliar.

Fig. 3.

Slope of learning. Histogram of the slopes of learning in Table 1, with one symbol for each row of the table. The labeled symbols  ,

,  , and

, and  represent our identification tasks. The horizontal position of each symbol is the log-log slope b. The dashed vertical line corresponds to the dashed horizontal line in Table 1. This histogram shows the dichotomy of fast learning of unfamiliar objects and slow learning of familiar objects. We speculate that the fast learning of unfamiliar objects is learning to combine (i.e., recognize the shapes), which quickly saturates, such that, once those objects have become familiar, we are reduced to learning slowly as we gradually learn to detect the features better.

represent our identification tasks. The horizontal position of each symbol is the log-log slope b. The dashed vertical line corresponds to the dashed horizontal line in Table 1. This histogram shows the dichotomy of fast learning of unfamiliar objects and slow learning of familiar objects. We speculate that the fast learning of unfamiliar objects is learning to combine (i.e., recognize the shapes), which quickly saturates, such that, once those objects have become familiar, we are reduced to learning slowly as we gradually learn to detect the features better.

Our result—the shallow slope of learning to detect and the steep slope of learning to combine—can explain the effects of stimulus complexity and familiarity on the rate of learning, where complex objects (requiring discrimination along many perceptual dimensions) are learned faster than (simple) Gabors, and where unfamiliar objects are learned faster than familiar objects.

It seems that complex objects are learned more quickly than Gabors because complex objects require combining. Comparing across studies in the literature (Table 1), we find that learning to identify stimuli that require combining, such as unfamiliar faces (slope b = −0.40), bandpass-filtered noise textures (−0.26), 4 × 4 random-checkerboard patterns (−0.16), and compound gratings (−0.21), is much quicker than learning to detect a Gabor (−0.03, −0.06), which does not require combining.

However, combination learning soon saturates, as the letters become familiar. Extrapolating the fitted line for human combination (Fig. 2, IH) predicts that efficiency would reach 100% (ideal combining) after 1 million trials. Typical readers read a million letters every 2 wk, for years. With so much experience, surely they have learned to combine as well as they can. Any additional learning of these familiar letters likely occurs in the detection step. This is presumably why the slope of learning familiar letters (−0.02) matches our measured slope of learning in the detection step (−0.03). When both the task and stimuli are familiar (e.g., identifying a familiar letter), the slope of learning falls on one side of the dashed line, showing slow learning (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Slopes of learning unfamiliar tasks or stimuli fall on the other side. Presumably the steep slope for unfamiliar stimuli is the fast learning of combination, which saturates once the stimuli are familiar, leaving only the slow learning of detection.

Number of Features and Extent of Each Feature.

We find that after 1,000 trials with an eight-letter subset of Indy18, the 15% combination efficiency (IH) is 7× the 2.1% detection efficiency (HI). In two-stage identification, each feature is detected independently, so we expect the detection efficiency to be independent of the number of features. The Gabor that we used as a feature was fairly extended. Detection efficiency could be raised by using a less-extended Gabor, with fewer bars. Because HI and II efficiencies are nearly independent of the number of features, and H and HH efficiencies are inversely proportional to the number of features, Eq. 3 implies that combination efficiency must be inversely proportional to the number of features, which could be explored by testing Indy4 and Indy100, say. Thus, reducing the number of features would increase combining efficiency without affecting the detection efficiency. Reducing the Gabor extent would increase the detection efficiency without affecting the combining efficiency.

Beyond Gabor Letters.

It may be possible to extend our approach beyond Gabor letters to other stimuli, such as words, faces, and scenes, whose features are unknown. If one assumes the separability found here, then it may be easy to factor out the efficiency of detecting (Eq. 5). Alternatively, mild image transformations, like scaling and translation, change the features but preserve abstract properties of the feature combination, like shape, that may determine the object’s identity. We noted at the outset that the existing literature on perceptual learning in early and late visual processes suggests that combination learning transfers across mild transformations and detection learning does not. In human observers, the steps are separable: Overall composite efficiency is the product of the composite efficiencies of the two steps (Eq. 6). Thus, for identification of an object from an arbitrary set, measuring the partial transfer of learning across a mild transformation like scaling or translation would distinguish the contributions of both steps: feature detection and combination.

Materials and Methods

On each trial, we ask the unconstrained or composite observer to identify an IndyEighteen letter in added white noise. The letter and noise are both static, presented together for 200 ms. Testing of each unconstrained or composite observer begins with a new eight-letter alphabet and is performed in a single block of 25 runs, with 40 trials per run. Short (2-min) breaks are taken between runs, as needed, and longer (30-min) breaks are taken between blocks. The entire session was completed within 8 h in 1 d, without sleep or naps. The order of the blocks (one per task) is randomized for each observer to minimize any order effect in the group average.

Unconstrained H: Human Identifies.

The human participant identifies, unconstrained. On each trial, we present a letter at threshold contrast (Fig. 4) to the human participant, who identifies the letter by selecting it from the response screen (Fig. 1). This trial challenges the human to identify, presumably by detecting and combining.

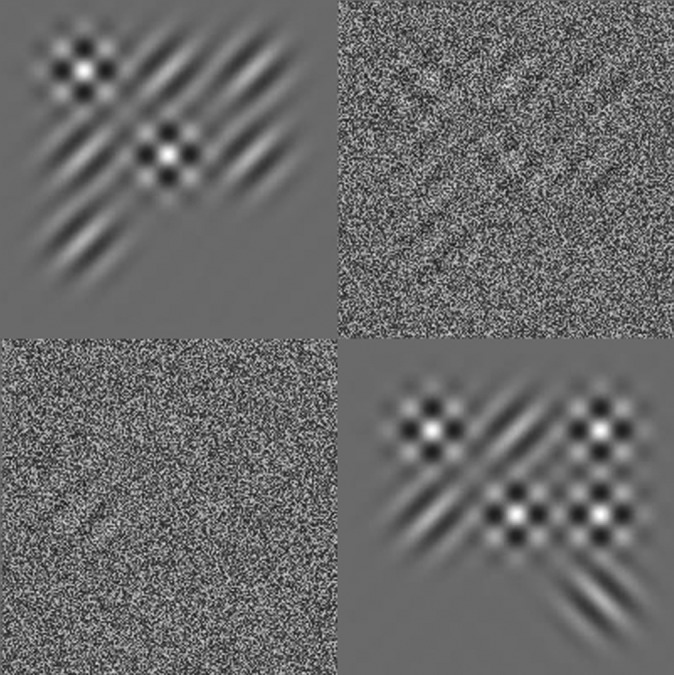

Fig. 4.

Stimuli. (Upper Left) A Gabor letter. When unconstrained, the human participant is presented with a Gabor letter faintly in noise (Upper Right). As the detector, the participant is presented with a single feature faintly in noise (Lower Left) and, as the combiner, with an imperfect set of detected features (Lower Right). In this last case, the high-contrast Gabors are easily seen, but are a less-than-faithful copy of the original letter’s features, which makes it hard to guess what the original letter was.

Unconstrained I: Ideal Identifies.

The ideal observer identifies, unconstrained. The human participant plays no role. On each trial, we present a letter at threshold contrast. The ideal identifies the letter by choosing the most likely possibility; it compares the noisy stimulus to each letter on the response screen at the contrast of the signal, and selects the most similar (minimum rmsd; see appendix A of ref. 5). The ideal achieves the best possible expected performance, and this is the baseline for calculating efficiency.

Composite HI: Two Steps (Human Detects, Ideal Combines).

The human participant detects and the bionic crutch (ideal combiner) combines. On each identification trial, instead of being shown the whole letter in a single presentation, the human performs 18 detection trials, one for each possible feature. (The 18 detection trials count as one identification trial in the horizontal axis of Fig. 2.) On each detection trial, the human participant reports whether the feature is present by responding “present” or “absent.” The 18 present-vs.-absent decisions are recorded as an 18-bit string (1 if present; 0 if otherwise) that is passed to the bionic crutch (ideal combiner). The ideal combiner makes its selection by comparing the string received to the string for each letter on the response screen, selecting the most similar (minimum Hamming distance) (33); this challenges the human participant to detect, without challenging combination.

Composite IH: Two Steps (Ideal Detects, Human Combines).

The bionic crutch (ideal detector) detects and the human participant combines. On each identification trial, the crutch performs 18 detection trials. On each detection trial, the crutch selects the most probable hypothesis (present or absent), given the noisy stimulus and the frequency of that feature in the alphabet. Features judged by the crutch to be present are displayed at high contrast to the human participant, who identifies the letter by selecting it from the response screen; this challenges the human to combine, without challenging detection.

Composite II: Two Steps (Ideal Detects and Combines).

The two bionic crutches together perform the whole task, in cascade. The human participant plays no role.

Composite HH: Two Steps (Human Detects and Combines).

The human participant takes the two steps in separate sessions, one for each step. This trial challenges the human to detect in one session, and to combine in another session. The level of performance achieved by this two-step composite observer, HH, is computed from the measured performance of the other three two-step composites: HI, IH, and II. For this calculation, we suppose that the efficiency η of each two-step composite observer is the product of two factors, a and b, one for each step, and that each factor depends on whether that step is performed by the human (H) or an ideal bionic crutch (I), but it is independent of how the other step is performed:

|

Because multiplication is transitive, we easily solve for the two-step human efficiency in terms of the others:

This equation can be recast as a statement about thresholds, using Eq. 1 to substitute thresholds for efficiencies,

Both equations correspond to the same dashed line in Fig. 2, using the threshold scale on the left (Eq. 4) or the efficiency scale on the right (Eq. 3). In future work, it will be interesting to study the human combination efficiency ηIH, for which we can solve Eq. 3,

All of the terms on the right of Eq. 5 are easily accessible. ηH is easy to measure, and our work here suggests that, in future studies, one might assume that ηHH = ηH. The human efficiency of detecting ηHI seems to be conserved across many conditions, so that it could be estimated once. And the two-step efficiency ηII is easily computed by implementing the one- and two-step ideals. In this way, Eq. 5 could make it easy to routinely estimate the observer’s combining efficiency ηIH.

Eq. 3 may seem odd if you did not expect the ηII term there for two-step efficiency; we can make it more intuitive by defining composite efficiency  relative to the composite ideal, II. Recall that standard efficiency is η = EI/E. We now define composite efficiency

relative to the composite ideal, II. Recall that standard efficiency is η = EI/E. We now define composite efficiency  = EII/E. In this new notation, Eq. 3 becomes

= EII/E. In this new notation, Eq. 3 becomes

In words, for any observer whose efficiency is separable (Eq. 2), the overall composite efficiency is the product of the composite efficiencies of the steps. Eqs. 2–6 are all equivalent. Though the equation for  (Eq. 6) is simpler and more intuitive than the equation for η (Eq. 3), we chose to plot the traditional familiar efficiency η rather than our new-fangled composite efficiency

(Eq. 6) is simpler and more intuitive than the equation for η (Eq. 3), we chose to plot the traditional familiar efficiency η rather than our new-fangled composite efficiency  because they differ solely by the factor ηII, which is nearly 1.

because they differ solely by the factor ηII, which is nearly 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Berendes, Y-Lan Boureau, Charles Bigelow, Rama Chakravarthi, Hannes Famira, Judy Fan, Jeremy Freeman, Ariella Katz, Yann LeCun (isolating detection), Christine Looser, Najib Majaj, Charvy Narain, Robert Rehder, Wendy Schnebelen, Elizabeth Segal, Eva Suchow, Steven Suchow, Katharine Tillman, Bosco Tjan (adding the unconstrained ideal), and Ed Vessel for helpful comments and discussion. We thank several anonymous reviewers for many helpful suggestions. This is draft 146. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01–EY04432 (to D.G.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Pelli et al. (5) found that human observers need 7 ± 2 feature detections for threshold letter identification for all traditional alphabets tested, over a 10-fold range of complexity. Assuming that feature count is proportional to complexity, as proposed in ref. 5, then, even if the least-complex alphabet tested had only seven features per letter, the most complex had 70 features per letter. Thus the seven features detected at the threshold for identification of a complex letter are only a small fraction of the letter’s features.

†Using a Monte Carlo simulation, we determined that 4–14 feature detections are required to achieve criterion performance of 75% correct for identifying a letter from a set of eight randomly selected IndyEighteen letters, depending on the false alarm rate. A false alarm occurs when an absent feature is “detected.” Sometimes, by chance, enough features are falsely detected such that the letter appears more similar to one of the foils than to the target. Additional feature detections, hits, are needed to compensate. We considered false alarm rates between 0% and 51%. At false alarm rates greater than 51%, it is impossible for the observer to achieve criterion performance, even with a hit rate of 100%.

‡Vul E, Goodman ND, Grifths TL, Tenenbaum JB (2009) One and done? Optimal decisions from very few samples. Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, eds Taatgen NA, van Rijn H (Cogn Sci Soc, Austin, TX), July 29, 2009, pp 66–72.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1218438110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rosch E, Mervis CB, Gray W, Johnson DM, Boyes-Braem P. Basic objects in natural categories. Cognit Psychol. 1976;8:382–439. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong ACN, Gauthier I. An analysis of letter expertise in a levels-of-categorization framework. Vis Cogn. 2007;15:854–879. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelli DG, Farell B, Moore DC. The remarkable inefficiency of word recognition. Nature. 2003;423(6941):752–756. doi: 10.1038/nature01516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelli DG, et al. Grouping in object recognition: The role of a Gestalt law in letter identification. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2009;26(1):36–49. doi: 10.1080/13546800802550134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelli DG, Burns CW, Farell B, Moore-Page DC. Feature detection and letter identification. Vision Res. 2006;46(28):4646–4674. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treisman A. Features and objects: The fourteenth Bartlett memorial lecture. Q J Exp Psychol A. 1988;40(2):201–237. doi: 10.1080/02724988843000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinker S. Visual cognition: An introduction. Cognition. 1984;18(1-3):1–63. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(84)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy GL. The Big Book of Concepts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson E. Principles of Perceptual Learning and Development. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine I, Jacobs RA. Comparing perceptual learning tasks: A review. J Vis. 2002;2(2):190–203. doi: 10.1167/2.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahissar M, Hochstein S. Task difficulty and the specificity of perceptual learning. Nature. 1997;387(6631):401–406. doi: 10.1038/387401a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson AB. Probability summation over time. Vision Res. 1979;19(5):515–522. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(79)90136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robson JG, Graham N. Probability summation and regional variation in contrast sensitivity across the visual field. Vision Res. 1981;21(3):409–418. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furmanski CS, Schluppeck D, Engel SA. Learning strengthens the response of primary visual cortex to simple patterns. Curr Biol. 2004;14(7):573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer MJ. Practice improves adults’ sensitivity to diagonals. Vision Res. 1983;23(5):547–550. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahle M. Perceptual learning: Specificity versus generalization. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15(2):154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fine I, Jacobs RA. Perceptual learning for a pattern discrimination task. Vision Res. 2000;40(23):3209–3230. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovács I, Kozma P, Fehér A, Benedek G. Late maturation of visual spatial integration in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(21):12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dosher BA, Lu ZL. Mechanisms of perceptual learning. Vision Res. 1999;39(19):3197–3221. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polk TA, Farah MJ. Late experience alters vision. Nature. 1995;376(6542):648–649. doi: 10.1038/376648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung ST, Levi DM, Tjan BS. Learning letter identification in peripheral vision. Vision Res. 2005;45(11):1399–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suchow JW, Pelli DG. Learning to identify letters: Generalization in high-level perceptual learning. J Vis. 2005;5(8):712. (abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levi DM, Hariharan S, Klein SA. Suppressive and facilitatory spatial interactions in peripheral vision: Peripheral crowding is neither size invariant nor simple contrast masking. J Vis. 2002;2(2):167–177. doi: 10.1167/2.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levi DM, Sharma V, Klein SA. Feature integration in pattern perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(21):11742–11746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loomis JM. On the tangibility of letters and braille. Percept Psychophys. 1981;29(1):37–46. doi: 10.3758/bf03198838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seitz AR, Watanabe T. The phenomenon of task-irrelevant perceptual learning. Vision Res. 2009;49(21):2604–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geisler WS. Sequential ideal-observer analysis of visual discriminations. Psychol Rev. 1989;96(2):267–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelli DG, Farell B. Why use noise? J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 1999;16(3):647–653. doi: 10.1364/josaa.16.000647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sternberg S. Process decomposition from double dissociation of subprocesses. Cortex. 2003;39(1):180–182. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu ZL, Dosher BA. Perceptual learning retunes the perceptual template in foveal orientation identification. J Vis. 2004;4(1):44–56. doi: 10.1167/4.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold J, Bennett PJ, Sekuler AB. Signal but not noise changes with perceptual learning. Nature. 1999;402(6758):176–178. doi: 10.1038/46027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michel MM, Jacobs RA. Learning optimal integration of arbitrary features in a perceptual discrimination task. J Vis. 2008;8(2):3.1–16. doi: 10.1167/8.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamming RW. Error detecting and error correcting codes. Bell Syst Tech J. 1950;29(2):147–160. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watson AB, Robson JG. Discrimination at threshold: Labelled detectors in human vision. Vision Res. 1981;21(7):1115–1122. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Wilson HR. Dependence of plaid motion coherence on component grating directions. Vision Res. 1993;33(17):2479–2489. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90128-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis. 1997;10(4):433–436. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis. 1997;10(4):437–442. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pelli DG, Zhang L. Accurate control of contrast on microcomputer displays. Vision Res. 1991;31(7-8):1337–1350. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90055-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watson AB, Pelli DG. QUEST: A Bayesian adaptive psychometric method. Percept Psychophys. 1983;33(2):113–120. doi: 10.3758/bf03202828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.