Abstract

Light is both the ultimate energy source for most organisms and a rich information source. Vitamin A-based chromophore was initially used in harvesting light energy, but has become the most widely used light sensor throughout evolution from unicellular to multicellular organisms. Vitamin A-based photoreceptor proteins are called opsins and have been used for billions of years for sensing light for vision or the equivalent of vision. All vitamin A-based light sensors for vision in the animal kingdom are G-protein coupled receptors, while those in unicellular organisms are light-gated channels. This first major switch in evolution was followed by two other major changes: the switch from bistable to monostable pigments for vision and the expansion of vitamin A’s biological functions. Vitamin A’s new functions such as regulating cell growth and differentiation from embryogenesis to adult are associated with increased toxicity with its random diffusion. In contrast to bistable pigments which can be regenerated by light, monostable pigments depend on complex enzymatic cycles for regeneration after every photoisomerization event. Here we discuss vitamin A functions and transport in the context of the natural history of vitamin A-based light sensors and propose that the expanding functions of vitamin A and the choice of monostable pigments are the likely evolutionary driving forces for precise, efficient, and sustained vitamin A transport.

Keywords: vitamin A, retinoid, opsins, retina, retinol, retinal, STRA6, retinol binding protein

1. Sunlight and Vitamin A

The prevalent light source throughout evolution has been sunlight shining on the surface of the earth. For billions of years, vitamin A biology has been tightly linked to sunlight. Living organisms use sunlight primarily as a source of energy, the source of information for vision, and an indicator of time. Remarkably, vitamin A-based chromophore has evolved as the light sensors for all three usages (Table 1). Archaebacteria use vitamin A-based light-driven pumps to harvest light energy (e.g., by creating the electrochemical gradient of protons to drive ATP synthase). This is an alternative mechanism to chlorophyll-based phototrophy. For adjusting the biological clock, vitamin A-based photoreceptor proteins are used as the light sensors, although flavin-based photoreceptor proteins have also been used for this purpose. However, for vision or the equivalent of vision, the vast majority of species use vitamin A-based chromophore as the light sensor. Vitamin A-based chromophore is the exclusive choice for vision in multicellular organisms.

Table 1.

Evolution of vitamin A-based light sensors (opsins) from bacteria to humans. The symbol # denotes the sensing of light by visual pigments for the circadian clock and pupillary reflex. Due to the tremendous diversity of opsins and space limitation, this table only depicts opsins that are representative of each kind. Opsin homologs (e.g., RGR in mammals) that function as light-dependent retinoid isomerases are not included.

| Kingdom | Species | Photoreceptor Cell or Structure | Physiological Functions | Photoreceptor Proteins | Retinal Chomophore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animalia |

Homo sapiens Human |

Cones | High luminescence vision and color vision + # | Long-wave cone pigment | 11-cis retinal |

| Medium-wave cone pigment | |||||

| Short-wave cone pigment | |||||

| Rod | Low luminescence vision + # | Rhodopsin | |||

| Light-sensitive ganglion cell | Light-sensing for the circadian clock and papillary reflex (#) | Melanopsin | |||

|

Mus musculus Mouse |

Cones | High luminescence vision and color vision + # | Medium-wave cone pigment UV cone pigment |

11-cis retinal | |

| Rod | Low luminescence vision + # | Rhodopsin | |||

| Light-sensitive ganglion cell | Light-sensing for the circadian clock and papillary reflex (#) | Melanopsin | |||

|

Gallus gallus Chicken |

Cones | High luminescence vision and color vision + # | Long-wave cone pigment Medium-wave cone pigment Short-wave cone pigment UV cone pigment |

11-cis retinal | |

| Rod | Low luminescence vision + # | Rhodopsin | |||

| Light-sensitive ganglion cell | Light-sensing for the circadian clock and papillary reflex (#) | Melanopsin | |||

| pinealocyte | Regulation of pineal circadian cycle | Pinopsin | |||

|

Rana catesbeiana Frog |

Rod and cones of adult frog | Vision on land and in water | Visual pigments | 11-cis retinal | |

| Photosensitive melanophore | Light-dependent melanosome migration | Melanopsin | |||

| Rod and cones of tadpole | Vision in water | Visual pigments | 11-cis-3,4-dehydroretinal | ||

|

Watasenia scintillans Squid |

Retinal photoreceptors | Vision in water | Visual pigments | 11-cis-3,4-dehydroretinal | |

| 11-cis-4-hydroxyretinal | |||||

| 11-cis retinal | |||||

|

Drosophila melanogaster Fly |

R1 to R7 photoreceptors | Vision | Visual pigments | 11-cis-3-hydroxyretinal | |

| Plantae |

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Green algea |

Eye spot | Phototactic response | Chlamyopsin | All-trans retinal |

| Photophobic response | |||||

| Monera |

Halobacterium halobium Bacteria |

Halobacterium halobium | Light-driven chloride pump | Halorhodopsin | All-trans retinal |

| Light-driven proton pump | Bacteriorhodopsin | ||||

| Phototactic response | Sensory rhodopsin I | ||||

| Photophobic response | Sensory rhodopsin II |

Even vitamin A’s name is tightly linked to vision. The scientific name for vitamin A derivatives is retinoid, which is derived from the word “retina”. Retinoids include retinol (the alcohol form), retinal (the aldedyde form, also called retinaldehyde or retinene) and retinoic acid (the acid form). Although vitamin A existed as a chemical before it functioned as a vitamin and retinal existed as a light sensor before there was a retina, we still use these names to refer to these chemicals.

What makes vitamin A so special for vision (the perception of light)? Why was vitamin A repeatedly chosen by evolution as the sensor for sunlight? What determined the region of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye? There are two important factors that provide likely answers for these related questions. First, the conjugation of the aldehyde end of retinal to photoreceptor proteins causes a red shift in its absorbance to the visible range (from the perspective of human vision). Visible light (visible due to vitamin A-based light sensors) generally matches the peak irradiance of sunlight on the earth’s surface [1,2]. In contrast, most other light sensors absorb primarily in the UV range (e.g., flavin-based light sensors). Second, the large light-induced conformational change of vitamin A-based chromophore makes it ideal as a ligand for membrane receptors. The large conformational change likely makes it easier for the photoreceptor protein to distinguish the silent state (in the dark) and the activated state (in the light).

1.1. The First Major Switch in the Evolution of Vitamin A-Based Light Sensors

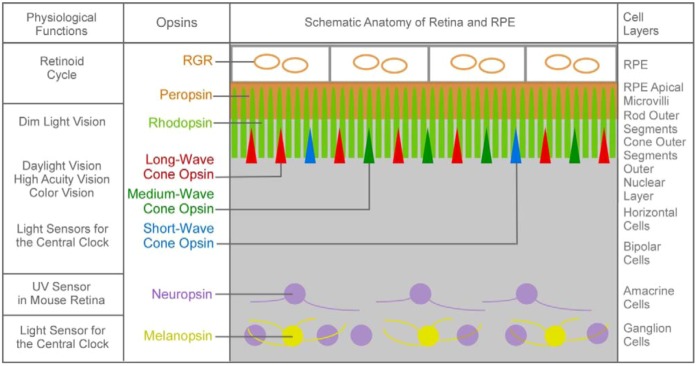

All vitamin A-based photoreceptor proteins are called opsins. All opsins in the animal kingdom that sense light for vision (visual pigments) are G-protein coupled receptors. Visual pigments sense light for daytime and nighttime vision and encode wavelength information of light for color vision [3]. All opsins in the animal kingdom are homologous to visual pigments. In contrast, opsins in unicellular organisms are light-gated channels (for light sensing) or light-driven pumps (for harvesting light energy) [4]. The switch from ion channel and pumps to G-protein coupled receptors is the first major event in the evolution of vitamin A-based light sensors (Table 1). Opsins that are light-gated ion channels or pumps use all-trans retinal as the chromophore, while opsins that are G-protein coupled receptors all use 11-cis retinal as the chromophore (Table 1 and Figure 1). The vitamin A-based light sensors listed in Table 1 are not meant to be all inclusive because some species contain surprisingly large numbers of opsins, and the functions of some opsins are still not well understood. Using humans and mice as an example, the human retina has long-, medium- and short-wave visual pigments in cone photoreceptor cells [5,6], rhodopsin in rod photoreceptor cells [7,8,9,10], melanopsin in ganglion cells [11,12,13,14,15,16,17], peropsin in the apical microvilli of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) [18] and RGR in the intracellular membranes of the RPE [19,20,21,22] (Figure 2). The mouse retina does not express the long-wave cone pigment [23], but has an additional opsin called neuropsin, which is mostly localized to the amacrine and ganglion cell layers [24,25].

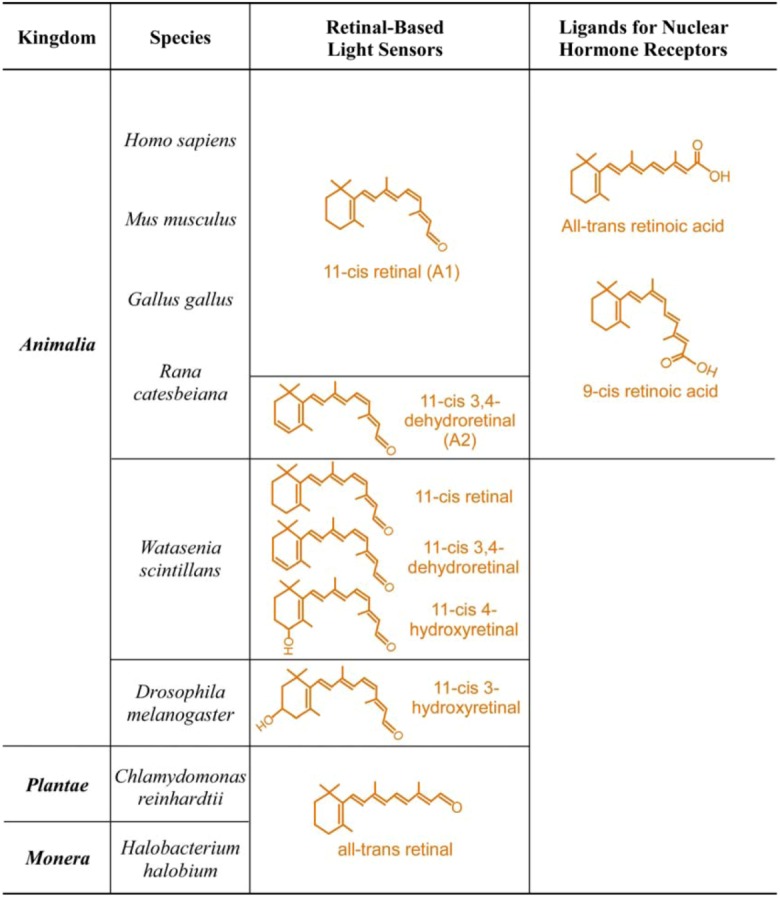

Figure 1.

Examples of structural divergence of biologically active retinoids. For simplicity, only representative biologically active endogenous retinoids are shown.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the localization of various opsins in human and mouse retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Only cells or cellular structures that express opsins are shown and are color-coded. There are species variations. Human, but not mouse, has the long-wave cone pigment. Neuropsin is expressed in the mouse retina, but not in the human retina.

Although there is tremendous diversity in the absorption maxima of cone visual pigments, the peak absorbance of rhodopsin, the dim light receptor, in many species is 500 nm. Why not 450 nm or 550 nm? One likely explanation is that the wavelength of the peak irradiance of sunlight on earth surface is 500 nm. Moonlight, the dominant light in natural world at night, is reflected sunlight and thus has same peak irradiance. The peak absorbance of rhodopsin matches this peak irradiance to achieve maximum sensitivity to available light. In contrast, maximum sensitivity is less important for cone visual pigments, which diversify their absorbance maxima for color vision. An extreme example of how available light determines the absorption spectra of visual pigments is the color vision of coelacanth, which lives at a depth about 200 m. To detect color and light in deep ocean where available light spans a very narrow range around 480 nm, coelacanth has only two visual pigments with absorption maxima of 478 nm and 485 nm, respectively [26]. This is in sharp contrast to another extreme example of a fish that has vision both above and below water (Anableps anableps). This fish has ten different opsins to adapt to vision both above and below water [27]. Visual pigments can achieve the exact absorption maximum that meets the organism’s biological need through several mechanisms of spectral tuning. The common mechanism of spectral tuning is to change the protein environment that surrounds the chromophore [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Generally, opsin environments that encourage π-electron delocalization of retinal cause a red shift in the absorption maximum. Another mechanism is by changing the structure of the chromophore itself. Although retinal is the universal chromophore for all vitamin A-based light sensors, the exact isomer of retinal can be different between species (Figure 1). For example, aquatic animals are known to shift absorption maxima of visual pigments by using the A1 (11-cis retinal) or A2 (11-cis-3,4-dehydroretinal) chromophore [36,37,38,39,40]. There are also examples of terrestrial vertebrates using vitamin A2-based visual pigments, which belong to the most red-shifted visual pigments (e.g., absorption maximum of 625 nm) [41]. A2 pigments absorb longer wavelengths of light compared to the A1 version because of the extension of the conjugated chain of the chromophore.

1.2. The Second Major Switch in the Evolution of Vitamin A-Based Light Sensors

The second major change in the evolution of vitamin A-based light sensors is the emergence of monostable pigments (Table 2). All opsins before vertebrate visual pigments (from opsins of unicellular organisms to invertebrate opsins) are bistable pigments, which can be regenerated by light after photobleaching (Table 2). All vertebrate visual pigments are monostable pigments, which release the chromophore after every photoisomerzation event and depend on an enzymatic cycles called the visual cycle to regenerate [42,43,44,45,46]. To compete with bleached rhodopsin for chromophore in daylight, cone visual pigments have their unique regeneration pathway that is different from the visual cycle that regenerates rhodopsin [47,48,49,50,51]. The isomerase in this cone-specific pathway has now been identified [52]. The mechanisms of chromophore release by bleached vertebrate rhodopsin and cone pigments have been studied recently [53,54]. Compared to the regeneration of the bistable pigments by light, the regeneration of monostable pigments requires much more complex mechanisms involving many enzymes and transport proteins (Table 3). The regaining of the 11-cis retinal by the monostable pigment after light-induced release is an important factor affecting the dark adaptation of photoreceptor cells [44]. Without the chromophore, the opsin apoprotein itself can activate signal transduction [55,56].

Table 2.

Convergent and divergent events in the evolution of vitamin A-based light sensors.

| Kingdom | Monera | Plantae | Animalia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Halobacterium halobium | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Drosophila melanogaster | Watasenia scintillans | Rana catesbeiana | Gallus gallus | Mus musculus | Homo sapiens |

| Light sensing | Vitamin A-based light sensors for vision or the equivalent of vision | |||||||

| Opsins | Light-driven pumps or light-gated ion channels | All visual pigments in the animal kingdom are G-protein coupled receptors | ||||||

| Chromophore | All-trans retinal | 11-cis retinal | ||||||

| Light-induced isomerization | All-trans to 13-cis | 11-cis to all-trans | ||||||

| Photolability | Bistable pigments | Monostable pigments for vision | ||||||

| Regeneration after photobleaching | Light-dependent | Enzymatic | ||||||

| Vitamin A functions | Vitamin A’s only function is light absorption | Vitamin A has diverse biological functions (e.g., regulating cell growth and differentiation in development and in adult) | ||||||

| Toxicity of free retinoid | Relatively low | High | ||||||

| Vitamin A transport | No known mechanism dedicated to long-range vitamin A transport | The emergence of the RBP/STRA6 system for sustained, specific, efficient and controlled delivery | ||||||

Table 3.

Comparison of bistable pigments and monostable pigments.

| Advantages | Bistable pigment | Monostable pigment |

|---|---|---|

| Disadvantages | ||

| Chromophore Release | Chromophore is not released after photoisomerization | Chromophore is released after every photoisomerization event |

| Regeneration Mechanism’s Complexity | The pigment can regenerate itself using light | Depends on multiple enzymatic steps and two cell types to regenerate every released chromophore molecule |

| Consumption of Cellular Energy | Does not depend on cellular energy to regenerate after bleaching and is much more energy efficient | Depends on the cellular energy of two cell types to regenerate every released chromophore molecule |

| The need of New Vitamin A-Based Chromophore | Vitamin A-based chromophore is only needed during the initial production of the bistable pigment | Constant recycling of retinoid between two cell types during daytime leads to inevitable loss of the chromophore and demands new supply |

| Sensitivity to Vitamin A Deficiency | Relatively low | High (the eye is the human organ most sensitive to vitamin A deficiency) |

| Long-Term Toxicity | No toxic retinal is released after light bleaching of the pigment | Toxic retinal is released after every photoisomerization event; free retinal can lead to toxic A2E formation |

| Frequency of the (Enzymatic) Visual Cycle | Infrequent (A visual cycle is used to recycle chromophore released from degraded opsins) | Highly frequent (A visual cycle is used after every photoisomerization event to regenerate bleached pigment) |

| “Wasteful” Regeneration | Little or no wasteful regeneration that consumes cellular energy | Constant regeneration of bleached rhodospin in bright daylight when the rod is completely saturated is highly wasteful |

| Regeneration in the Dark | Depends on light to regenerate; can regenerate in the dark only during the initial formation of the pigment | Due to its ability to be regenerated in complete darkness, it is more sensitive for nighttime vision |

| Consequence of Photon Absorption | Activation or regeneration | Activation only |

| Encoding Wavelength Information of Light | Each pigment has two kinds of spectral sensitivity (for bleaching and regeneration) | Each pigment has a distinct spectral sensitivity and is perhaps more precise in encoding wavelength information for color vision |

Vision is known to optimize energy use [57,58]. For chromophore regeneration, vertebrate photoreceptor cells took the seemingly paradoxical evolutionary choice of using the much more energy-inefficient monostable pigments. In contrast, bistable pigments are regenerated by light after photobleaching without any cellular energy. Comparing the energy efficiency of the two mechanisms is analogous to comparing heating a building using fossil fuel versus solar energy. To make it even more “wasteful”, we need to constantly consume cellular energy to regenerate bleached rhodopsin in daylight, even when rod photoreceptor cells are completely saturated and do not contribute to visual perception. In contrast, bistable pigments only need enzymatic regeneration when the photoreceptor protein is degraded, not when it is bleached [59]. This regeneration is important during nutritional deficiency.

To convert the released free all-trans retinal back to 11-cis retinal for monostable pigments, evolution produced many proteins dedicated to the visual cycle. All these proteins are potential causes of blinding diseases. An example is ABCA4 (ABCR) [60,61], whose surprising existence is a testament to the sophistication of the visual cycle. ABCA4 is an ATP-dependent membrane transport protein in photoreceptor disc membranes, and its function is to accelerate the transport of retinal conjugate across photoreceptor disc membranes [62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Loss of ABCA4 function leads to the accumulation of A2E, a toxic bis-retinoid adduct and delayed dark adaptation.

ABCA4 mutations are associated with several blinding diseases in humans, including Stargardt macular dystrophy [69], cone rod dystrophy [70] and retinitis pigmentosa [70,71]. Since ABCA4 functions to accelerate the regeneration of monostable pigments and species that do not have monostable pigments naturally lack ABCA4, human diseases associated with ABCA4 ultimately originated from the choice of monostable pigments during evolution. There may still be other unknown components of the visual cycle. For example, ABCA4 is expressed in the disc membranes of photoreceptor cells where it can play no role in retinal transport between the RPE and photoreceptor cells.

Although vertebrates exclusively use monostable pigments for vision, theydo have endogenous bistable pigments in the inner retina including melanopsin [72,73,74,75] and neuropsin [25,76]. Exogenously expressed bistable pigments from unicellular organisms even function well both in the vertebrate retina [77] and the brain (as employed by the technique optogenetics) [78]. Bistable pigments can be repeatedly stimulated by light in vertebrate neurons that have no access to the visual cycle [78]. Why did evolution come up with monostable pigments, which require much more “maintenance”? Despite the many advantages of bistable pigments, there have to be very good reasons for monostable pigments to exist as the universal pigments for vertebrate vision. The first likely reason is survival in the dark. Vision at night can offer tremendous survival advantages for both predators (e.g., to find more prey) and prey (e.g., to avoid predators). Unlike bistable pigments, monostable pigments can regenerate in complete darkness and therefore are likely more suitable for continuous night vision. Bistable pigments can be formed in the dark only in the initial formation of the bistable pigment [79]. Another possible advantage is color vision. Monostable pigments may be more precise in discriminating different wavelengths of light (the basis of color vision) because the response of a bistable pigment to light is confounded by its two absorption maxima (one for activation and one for regeneration). There may be other reasons to justify the choice of this highly energy-consuming and disease-prone regeneration mechanism for visual pigments.

2. Broadening of the Biological Functions of Vitamin A

2.1. Expanding Biological Functions of Vitamin A

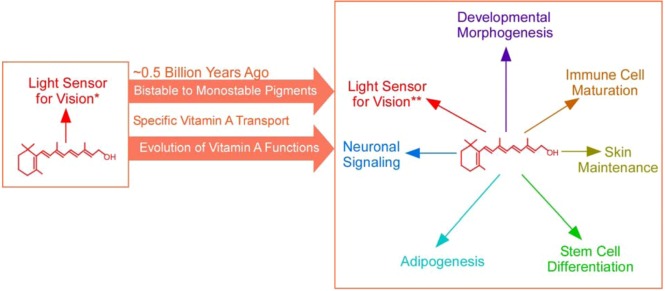

If vitamin A is taken in for vision, why not use it for something else? That’s exactly what happened in evolution (Figure 1 and Table 2). Vertebrates broaden the use of vitamin A to many other essential biological functions, including its essential roles in embryonic development, maturation of the immune system, maintenance of epithelial integrity, and in the adult brain for learning and memory and neurogenesis [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. This is the third major change in the biology of vitamin A. Most of these new functions are mediated by the acid form of vitamin A (retinoic acid) [88,89]. Since this functional diversification in evolution, vitamin A deficiency would no longer be limited to effects on vision, and vitamin A became an essential nutrient for almost all vertebrate organs.

Vitamin A deficiency affects many vertebrate organs [90,91]. The most well known effects of vitamin A deficiency in humans are night blindness [92] and increased childhood mortality and morbidity [93]. In adults, vitamin A deficiency can lead to profound impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation and long-term depression [94] and impairment in learning and memory [95]. Vitamin A deficiency can also lead to pathological changes in the lung [96,97], the skin [98], the thyroid [99] and the male and female reproductive systems [90,100]. It was recently discovered that retinol, but not retinoic acid, prevents the differentiation and promotes the feeder-independent culture of embryonic stem cells [101]; retinal inhibits adipogenesis [102]; and retinoic acid regulates protein translation in neurons independent of its roles in regulating gene transcription [103,104]. Given its numerous biological functions, retinoid plays positive or negative roles in a wide-range of human diseases, such as visual disorders [45], cancer [105,106], infectious diseases [82], diabetes [107,108], teratogenicity [109], and skin diseases [110].

2.2. Retinoid Toxicity Associated with the Evolution of Vitamin A Functions

Broadened biological activity of vitamin A is a double-edged sword that also leads to broader toxicity caused by excessive vitamin A or its derivatives (Table 4). Retinoid toxicity can be caused by physical properties of retinoid (e.g., acting like a detergent at sufficient concentrations), chemical reactivity of retinoid (e.g., modification of random proteins by free retinal), or inappropriate biological activities (e.g., retinoic acid activating or suppressing gene expression at the wrong cell type or at the wrong time) (Table 4). Excessive vitamin A uptake can lead to severe toxicity in humans [109,111,112,113]. Water-miscible, emulsified, and solid forms of retinol are much more toxic than oil-based retinol preparations [114]. Excessive retinoic acid is even more toxic than retinol, consistent with the fact that retinoic acid is more biologically active [115]. Retinoid therapy for human diseases is often associated with side effects such as terotogenicity [109,115,116]. Chronic exposure to clinical doses of 13-cis retinoic acid suppresses hippocampal neurogenesis and disrupts hippocampal-dependent memory [117]. In addition, 13-cis retinoic acid intake causes night blindness [118].

Table 4.

Biological functions and toxicities of vitamin A derivatives in vertebrates.

| Appropriate Amount |

Vitamin A Derivatives |

Excessive Amount | Evolutionary Origin of Toxicity | ||

| Known Biochemical Basis of Functions | Examples of Biological Functions | Example of Toxicity | Biochemical Basis of Toxicity | ||

| One the least toxic retinoids; stored by binding to retinol binding proteins | Vitamin A storage and transport | Retinol (Vitamin A alcohol) |

Pathological symptoms associated with hypervitaminosis A | Excessive vitamin A intake overwhelms and bypasses dedicated and specific delivery pathway to cause toxicity | Expanding biological roles of vitamin A |

| One the least toxic retinoids; stored as a lipid | Vitamin A storage and transport | Retinyl Ester (Vitamin A ester) |

Excessive retinyl ester in the blood is toxic | Excessive retinyl esters can be converted to biologically active retinoids to cause toxicity | Expanding biological roles of vitamin A |

| The chromophore for opsins, the photoreceptor proteins for vision and the biological clock | Light absorption for vision and for regulating the biological clock | Retinal (Vitamin A aldehyde) |

Excessive accumulation of retinal in retina causes photoreceptor degeneration | Random protein modification through Schiff-base formation; mediates photo-oxidative damage | Choice of monostable pigments that constantly release free retinal in daylight |

| Activates nuclear hormone receptors; regulates protein translation | Regulating the growth and differentiation from embryogenesis to adulthood; regulating learning and memory | Retinoic Acid (Vitamin A acid) |

Systemic random diffusion of retinoic acid is toxic to many adult organs; also a potent teratogen | The most toxic retinoid due to its activity in activating or suppressing gene expression | Expanding biological roles of vitamin A |

|

|

A2E (Retinal Derivative) |

The toxic fluorophore that accumulates in the RPE of Stargard disease patients and in aging human eyes | Photo-oxidative damage; Inhibits lysosomal enzymes and retinoid isomerase; activates the complement system | Choice of monostable pigments that constantly release free retinal in daylight |

Retinal is the vitamin A derivative that is most toxic, due to its chemical reactivity. Even when vitamin A is used only for light sensing, retinal can be toxic [119] due to its chemical toxicity in randomly modifying proteins through Schiff base formation. Retinal toxicity becomes more severe for organisms using monostable pigments, which constantly release free retinal in daylight. As a protein that interacts with retinal, ABCA4 in photoreceptor cells is sensitive to retinal-mediated photooxidative damage [120]. A photoreceptor cell culture study revealed that retinal is much more toxic than retinol in mediating photooxidative damage [121]. Photooxidation caused by all-trans retinal released from monostable pigments has been observed in single vertebrate photoreceptor cells [122]. Knocking out both ABCA4 and RDH8, two genes that function to reduce retinal toxicity, causes severe retina degeneration [123]. The constant release of free retinal in daylight by the monostable pigments also paves the way for the generation of a toxic chemical derived from retinal called A2E, a unique vitamin A derivative found in vertebrate eyes that has only toxicity but no beneficial function [124,125,126,127,128,129,130]. In a sense, A2E ultimately results from the choice of monostable pigments in evolution due to their constant release of free all-trans retinal and the demand for 11-cis retinal in daylight.

3. The Emergence of a Specific and Stable Vitamin A Transport Mechanism that Coincided with Major Changes in Vitamin A Functions

The tremendous expansion in the biological functions of retinoids, the dependence on vitamin A for survival, and toxicity associated with their random diffusion demand a specific and stable mechanism of vitamin A transport. The concomitant emergence of monostable pigments for vision also demands a specific and stable mechanism of vitamin A transport because the constant release of free retinal by monostable pigments (after every photoisomerization event) and the constant recycling of retinoid between two cell types in daylight inevitably causes loss of vitamin A (absorption of one photon initiates one cycle). Indeed, the diversification of vitamin A functions and the switching of visual pigments from bistable pigments to monostable pigments in evolution coincided with the emergence of a specific and dedicated vitamin A transport mechanism (Figure 3). This mechanism of vitamin A transport is mediated by the plasma retinol binding protein (RBP), a specific and sole carrier of vitamin A in the blood [131,132,133,134,135,136], and its specific membrane receptor STRA6, which mediates cellular vitamin A uptake [137].

Figure 3.

Summary diagram of the key events in the evolution of vitamin A functions that coincide with the emergence of RBP/STRA6-mediated specific vitamin A transport.

Surprisingly, evolution seems to have produced the RBP receptor STRA6 from scratch because it is not homologous to any membrane receptors or transporters of known function and represents a new type of cell-surface receptor [138]. In contrast, ABCA4, a transporter for vitamin A derivatives, belongs to an ancient family of ATP-dependent transporters. STRA6 employs a membrane transport mechanism distinct from known celluar mechanisms including active transport, channels, and facilitated transport [139,140]. STRA6’s vitamin A uptake is coupled to intracellular proteins involved in retinoid storage such as LRAT [137,141,142] or CRBP-I [139], but no single intracellular protein is absolutely required for its vitamin A uptake activity [139,140]. At the biochemical level, STRA6 has diverse catalytic activities such as catalyzing retinol release from holo-RBP [139,140], retinol loading into apo-RBP [139,142], retinol exchange between RBP molecules [140], and retinol transport from holo-RBP to apo-CRBP-I [139]. Depending on extracellular RBP species (the ratio of holo-RBP to apo-RBP) and intracellular proteins (the presence of CRBP-I or LRAT), STRA6 can promote retinol influx, retinol efflux or retinol exchange [140]. How STRA6 achieves its biological activities is not well understood. STRA6 has 9 transmembrane domains, 5 extracellular domains and 5 intracellular domains [143]. Between transmembrane 6 and 7 is an essential RBP binding domain [144].

Studies in human genetics and in animal models have revealed the critical functions of RBP and STRA6. Partial loss of RBP function leads to RPE dystrophy at a young age in humans [145,146]. Complete loss of RBP is embryonic lethal under vitamin A deficient conditions that mimic the natural environment [147]. RBP is required to mobilize liver-stored vitamin A [148]. Complete loss of STRA6 in human causes wide-spread pathogenic phenotypes in many organs [149,150]. Loss of STRA6 causes highly suppressed tissue vitamin A uptake in both zebrafish [142] and mouse [151]. Loss of STRA6 leads to the loss of most stored vitamin A in the eye and subsequent cone photoreceptor degeneration, consistent with previous findings that loss of visual chromophore causes cone photoreceptor degeneration [152,153,154,155].

STRA6 knockout causes the loss of 95% of the retinyl ester store in the RPE cells, the key cell type responsible for vitamin A uptake and storage for vision [151]. What is responsible for the STRA6-independent 5%? RBP/STRA6-mediated specific vitamin A transport is not the only mechanism of vitamin A delivery. Vitamin A, like many hydrophobic drugs, has a theoretically much simpler mechanism of transport by random diffusion. However, virtually all vitamin A in vertebrate blood is bound to RBP. The other most dominant mechanism is mediated by retinyl esters in the blood, as revealed by studies of RBP knockout mice [147,156]. Consistently, RPE-specific LRAT knockout also revealed that the RPE can take up retinyl esters without LRAT [157]. The LRAT-independent uptake of retinyl esters by the RPE is more than sufficient to account for the residual retinyl ester in STRA6 knockout mice [151]. This suggests that STRA6 is responsible for virtually all retinol accessible to LRAT in the RPE.

Retinyl ester bound to chylomicron is the primary vehicle that transports dietary vitamin A absorbed by the small intestine to the liver, the primary organ for vitamin A storage [158,159]. There is also strong experimental evidence that a fraction of the retinyl esters can be absorbed by peripheral organs as well [133,159]. This vitamin A transport mechanism is independent of RBP/STRA6. If retinyl ester in the blood can deliver vitamin A, why do we need RBP/STRA6? The many differences between the two mechanisms can answer this question (Table 5). The RBP/STRA6-mediated transport is a sustained and specific mechanism. The high affinity and specificity in RBP’s binding to STRA6 can target the vitamin A/RBP complex to specific cells that specialize in vitamin A uptake and storage (e.g., the RPE cell). Although retinyl ester in the blood is capable of partially compensating for the loss of RBP or STRA6 under vitamin A sufficient or excessive conditions, it “borrows” lipid transport pathways, which target a much wider variety of cell types (beyond those specialized in vitamin A uptake and storage) and cannot be relied on during vitamin A deficiency, which is common in natural environments. Studies in both animals [160] and humans [111] revealed that more toxicity is associated with vitamin A delivery independent of RBP. An increase above 10% in retinyl ester in the blood is regarded as a sign of vitamin A overload [111,131].

Table 5.

Comparison of vitamin A transport via holo-RBP in the blood vs. retinyl esters in the blood.

| RBP-Bound Retinol in Blood | Retinyl Ester in Blood | |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Origin | Primarily the liver | Primarily the small intestine |

| Source of Vitamin A | Vitamin A stored in the liver, the primary organ for vitamin A storage | Dietary vitamin A immediately after absorption by the small intestine |

| Ability to Mobilize Liver-Stored Vitamin A | Yes | No |

| Dependence on Immediate Diatary Intake | No | Yes |

| Regulation of its Concentration in the Blood | Yes | No |

| As a Source of Vitamin A During the Absence of Food | Yes | No |

| As a Source of Vitamin A in the Absence of Vitamin A in Food | Yes | No |

| Nature of the Carrier Protein(s) in the Blood | The only known natural ligand of RBP is retinol | Retinyl esters are carried by lipoproteins such as chylomicron remnants, which contain many kinds of lipids |

| Cellular Uptake Specificity | Cellular retinol uptake by the RBP receptor is not associated with cellular uptake of many other kinds of lipids | Cellular retinyl ester uptake is associated with cellular uptake of many other kinds of lipids |

| Regulatory Mechanism of Vitamin A Uptake | Unknown | Unknown |

| As a Cause of Vitamin A Toxicity in Human | No (Healthy people maintain micromolar concentrations in the blood) |

Yes (An increase above 10% in retinyl esters in the blood is a sign of vitamin A overload in human) |

There exists a STRA6 homolog. The function of this homolog is an intriguing question [161,162]. A recent study found that it is mostly expressed in the liver and the small intestine in mice and can take up vitamin A from holo-RBP similarly to STRA6 [163]. Since transfer of retinol within the liver does not depend on RBP, and liver largely obtains its stored vitamin A from chylomicron remnants [159], this receptor may help certain liver cells to obtain vitamin A from holo-RBP in the circulation. The small intestine absorbs vitamin A or its precursors from food and secretes retinyl esters bound to chylomicrons to be delivered to the liver for storage [158,159]. Because there is no retinol/RBP complex in the intestinal lumen, this receptor likely helps small intestine cells not directly accessible to vitamin A from food to obtain vitamin A from the circulation.

4. The Eye and Vitamin A

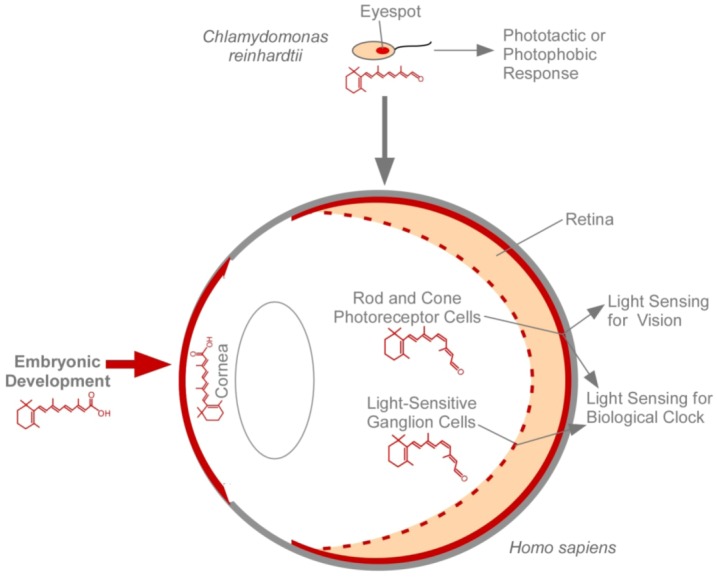

The earliest structure remotely related to an eye is the eyespot, a light sensing structure in the green alga Chlamydomonas. Although the human eye is vastly more complex than the eyespot, and the structures are separated by billions of years of evolutionary time, both serve a similar biological function in perceiving light, and both depend on vitamin A (Figure 4). Despite the growing dependence of other organs on vitamin A in evolution, the eye is still the organ most dependent on vitamin A. For human, the eye is the organ most sensitive to vitamin A deficiency, the loss of RBP, or the loss of STRA6 (Table 6). Given both the essential functions and toxicity of retinoids, how the eye regulates its vitamin A uptake to obtain a sufficient but not excessive amount is still poorly understood.

Figure 4.

Comparison of two retinal-based light sensing structures: the eyespot in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and the human eye. The human eye depends on vitamin A not only for light sensing for vision and the biological clock, but also for embryonic development and for the maintenance of the cornea. Cells or structures that depend on vitamin A are labeled in red.

Table 6.

In both mice and humans, the eye is the organ most sensitive to vitamin A deficiency, loss of RBP, or loss of STRA6.

| The Most Sensitive Organ in Mouse | The Most Sensitive Organ in Human | The Most Severe Systemic Phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A deficiency | The Eye | The Eye | Embryonic Lethality |

| Loss of RBP | The Eye | The Eye | Embryonic Lethality |

| Loss of STRA6 | The Eye | The Eye | Embryonic Lethality |

Nutritional blindness due to vitamin A deficiency is still a leading cause of blindness in the world. Vitamin A deficiency can deprive the photoreceptor cells of the visual chromophore [164]. In addition, vitamin A deficiency causes the disorganization of rod photoreceptor outer segments, degeneration of cone photoreceptor cells, and the loss of LRAT expression in the RPE [165]. If rod and cone photoreceptor cells that sense light for vision depend on vitamin A, what about sensing light for the biological clock, which needs to be frequently readjusted by light? An early study using a mammalian model showed that the spectral sensitivity of the photoreceptors that mediate light’s entrainment of the biological clock is indicative of a vitamin A-based light sensor that peaks at 500 nm [166]. Although there was a debate on whether it might be flavin-based, recent studies confirmed that it is vitamin A based and revealed that visual pigments in rod and cone and melanopsin in light-sensitive ganglion cells all contribute to this light sensing function.

Vitamin A, a chemical originally used only for light sensing, is now also an essential molecule for eye development. Retinoic acid, the acid form of vitamin A, plays critical roles in retina and eye development [167,168,169,170,171,172]. The human eye does not develop without STRA6, the RBP receptor that mediates vitamin A uptake [149,150,173]. STRA6’s influence on eye development may not be limited to its expression within the eye itself. One of the organs that expresses the highest level of STRA6 is the placenta, the maternal-fetal barrier which supplies essential nutrients for fetal development. STRA6 can also influence eye development by supplying retinoid to developing embryos in general.

In addition to sensing light for vision and circadian rhythm and eye development, vitamin A also plays crucial roles in maintaining a healthy cornea [174,175]. Without vitamin A, the cornea develops ulceration. Corneal dryness due to vitamin A deficiency is another common cause of human blindness. This role of vitamin A is likely related to one of vitamin A’s general functions in epithelial maintenance and stem cell differentiation. How the cornea absorbs vitamin A physiologically is still poorly understood.

Although human vision in a sense perfectly serves our daily needs, we are living with the consequences of the choice of monostable pigments in evolution. If this choice helped our ancestors survive at night, it came at surprisingly high costs. It is astonishing to realize that “every” photon we see depends on a complex enzymatic cycle that consumes cellular energy and releases free toxic retinoid. As we see using our cones in natural daylight or artificial light, a staggering amount of energy is consumed, and a constant flux of toxic free retinoid is cycling between cells to regenerate rhodopsin, which plays no role in daylight vision. In a sense, a whole range of human diseases, from our vision’s high sensitivity to vitamin A deficiency to Stargardt macular dystrophy, are the price we pay for this evolutionary choice.

5. Conclusion

For most of evolutionary history starting about 3 billion years ago, vitamin A has functioned as a light sensor. Vitamin A-based light sensors span a wide range of absorption maxima from UV to near infrared. This range matches the peak irradiance of sunlight on earth’s surface, the dominant light source in evolution that determines the “visible” light for fish in deep sea or human beings. The major changes during the evolution of vitamin A-based light sensors are the switch from light-gated ion channels to light-activated G-protein coupled receptors and the switch from bistable pigments to monostable pigments for vision. Vitamin A’s biological functions have also been tremendously expanded to include its crucial roles in regulating cell growth and differentiation from embryogenesis to adulthood. The likely driving forces for the evolution of a sustained, efficient and precise system of vitamin A transport are the high demand for vitamin A by vision (due to monostable pigments that constantly release the chromophore in daylight), the high toxicity associated with excess vitamin A, and the need to survive vitamin A deficiency, which is common in the natural environments. Because an imbalance in vitamin A homeostasis is associated with diverse human diseases including blindness and birth defects, a better understanding of how vitamin A is transported to the right cell type in the appropriate amount will help to devise new strategies to treat many human diseases caused by insufficient or excessive tissue retinoid levels or to use retinoids as therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgment

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01EY018144. H.S. is an Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Brine D.T., Iqbal M. Diffuse and global solar spectral irradiance under cloudless skies. Sol. Energy. 1983;30:447–453. doi: 10.1016/0038-092X(83)90115-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lean J. Evolution of the sun’s spectral irradiance since the maunder minimum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000;27:2425–2428. doi: 10.1029/2000GL000043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathans J. The evolution and physiology of human color vision: Insights from molecular genetic studies of visual pigments. Neuron. 1999;24:299–312. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spudich J.L., Yang C.S., Jung K.H., Spudich E.N. Retinylidene proteins: Structures and functions from archaea to humans. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;16:365–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathans J., Piantanida T.P., Eddy R.L., Shows T.B., Hogness D.S. Molecular genetics of inherited variation in human color vision. Science. 1986;232:203–210. doi: 10.1126/science.3485310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathans J., Thomas D., Hogness D.S. Molecular genetics of human color vision: The genes encoding blue, green, and red pigments. Science. 1986;232:193–202. doi: 10.1126/science.2937147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathans J. Rhodopsin: Structure, function, and genetics. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4923–4931. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khorana H.G. Rhodopsin, photoreceptor of the rod cell. An emerging pattern for structure and function. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hubbell W.L., Altenbach C., Hubbell C.M., Khorana H.G. Rhodopsin structure, dynamics, and activation: A perspective from crystallography, site-directed spin labeling, sulfhydryl reactivity, and disulfide cross-linking. Adv. Protein Chem. 2003;63:243–290. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(03)63010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palczewski K. G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:743–767. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Provencio I., Rodriguez I.R., Jiang G., Hayes W.P., Moreira E.F., Rollag M.D. A novel human opsin in the inner retina. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:600–605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00600.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hattar S., Liao H.W., Takao M., Berson D.M., Yau K.W. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: Architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science. 2002;295:1065–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1069609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panda S., Provencio I., Tu D.C., Pires S.S., Rollag M.D., Castrucci A.M., Pletcher M.T., Sato T.K., Wiltshire T., Andahazy M., et al. Melanopsin is required for non-image-forming photic responses in blind mice. Science. 2003;301:525–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1086179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dacey D.M., Liao H.W., Peterson B.B., Robinson F.R., Smith V.C., Pokorny J., Yau K.W., Gamlin P.D. Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells in primate retina signal colour and irradiance and project to the lgn. Nature. 2005;433:749–754. doi: 10.1038/nature03387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melyan Z., Tarttelin E.E., Bellingham J., Lucas R.J., Hankins M.W. Addition of human melanopsin renders mammalian cells photoresponsive. Nature. 2005;433:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nature03344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Do M.T., Kang S.H., Xue T., Zhong H., Liao H.W., Bergles D.E., Yau K.W. Photon capture and signalling by melanopsin retinal ganglion cells. Nature. 2009;457:281–287. doi: 10.1038/nature07682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guler A.D., Ecker J.L., Lall G.S., Haq S., Altimus C.M., Liao H.W., Barnard A.R., Cahill H., Badea T.C., Zhao H., et al. Melanopsin cells are the principal conduits for rod-cone input to non-image-forming vision. Nature. 2008;453:102–105. doi: 10.1038/nature06829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun H., Gilbert D.J., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Nathans J. Peropsin, a novel visual pigment-like protein located in the apical microvilli of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9893–9898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen D., Jiang M., Hao W., Tao L., Salazar M., Fong H.K. A human opsin-related gene that encodes a retinaldehyde-binding protein. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13117–13125. doi: 10.1021/bi00248a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morimura H., Saindelle-Ribeaudeau F., Berson E.L., Dryja T.P. Mutations in RGR, encoding a light-sensitive opsin homologue, in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:393–394. doi: 10.1038/70496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenzel A., Oberhauser V., Pugh E.N., Jr., Lamb T.D., Grimm C., Samardzija M., Fahl E., Seeliger M.W., Reme C.E., von Lintig J. The retinal G protein-coupled receptor (RGR) enhances isomerohydrolase activity independent of light. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29874–29884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radu R.A., Hu J., Peng J., Bok D., Mata N.L., Travis G.H. Retinal pigment epithelium-retinal G protein receptor-opsin mediates light-dependent translocation of all-trans-retinyl esters for synthesis of visual chromophore in retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:19730–19738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801288200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Applebury M.L., Antoch M.P., Baxter L.C., Chun L.L., Falk J.D., Farhangfar F., Kage K., Krzystolik M.G., Lyass L.A., Robbins J.T. The murine cone photoreceptor: A single cone type expresses both s and m opsins with retinal spatial patterning. Neuron. 2000;27:513–523. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarttelin E.E., Bellingham J., Hankins M.W., Foster R.G., Lucas R.J. Neuropsin (Opn5): A novel opsin identified in mammalian neural tissue. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:410–416. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojima D., Mori S., Torii M., Wada A., Morishita R., Fukada Y. UV-sensitive photoreceptor protein OPN5 in humans and mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoyama S., Zhang H., Radlwimmer F.B., Blow N.S. Adaptive evolution of color vision of the Comoran coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6279–6284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens G.L., Windsor D.J., Mui J., Taylor J.S. A fish eye out of water: Ten visual opsins in the four-eyed fish, anableps anableps. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merbs S.L., Nathans J. Role of hydroxyl-bearing amino acids in differentially tuning the absorption spectra of the human red and green cone pigments. Photochem. Photobiol. 1993;58:706–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1993.tb04956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun H., Macke J.P., Nathans J. Mechanisms of spectral tuning in the mouse green cone pigment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8860–8865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fasick J.I., Lee N., Oprian D.D. Spectral tuning in the human blue cone pigment. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11593–11596. doi: 10.1021/bi991600h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kochendoerfer G.G., Lin S.W., Sakmar T.P., Mathies R.A. How color visual pigments are tuned. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:300–305. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S.W., Sakmar T.P. Colour tuning mechanisms of visual pigments. Novartis Found. Symp. 1999;224:124–135. doi: 10.1002/9780470515693.ch8. discussion 135–141, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fasick J.I., Applebury M.L., Oprian D.D. Spectral tuning in the mammalian short-wavelength sensitive cone pigments. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6860–6865. doi: 10.1021/bi0200413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kusnetzow A.K., Dukkipati A., Babu K.R., Ramos L., Knox B.E., Birge R.R. Vertebrate ultraviolet visual pigments: Protonation of the retinylidene schiff base and a counterion switch during photoactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:941–946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yokoyama S. Evolution of dim-light and color vision pigments. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2008;9:259–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsin A.T., Beatty D.D., Bridges C.D., Alvarez R. Selective utilization of vitamins A1 and A2 by goldfish photoreceptors. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1983;24:1324–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma J.X., Kono M., Xu L., Das J., Ryan J.C., Hazard E.S., III, Oprian D.D., Crouch R.K. Salamander UV cone pigment: Sequence, expression, and spectral properties. Vis. Neurosci. 2001;18:393–399. doi: 10.1017/s0952523801183057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Temple S.E., Plate E.M., Ramsden S., Haimberger T.J., Roth W.M., Hawryshyn C.W. Seasonal cycle in vitamin A1/A2-based visual pigment composition during the life history of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 2006;192:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s00359-005-0068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ala-Laurila P., Donner K., Crouch R.K., Cornwall M.C. Chromophore switch from 11-cis-dehydroretinal (A2) to 11-cis-retinal (aA1) decreases dark noise in salamander red rods. J. Physiol. 2007;585:57–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saarinen P., Pahlberg J., Herczeg G., Viljanen M., Karjalainen M., Shikano T., Merila J., Donner K. Spectral tuning by selective chromophore uptake in rods and cones of eight populations of nine-spined stickleback (Pungitius pungitius) J. Exp. Biol. 2012;215:2760–2773. doi: 10.1242/jeb.068122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Provencio I., Loew E.R., Foster R.G. Vitamin A2-based visual pigments in fully terrestrial vertebrates. Vis. Res. 1992;32:2201–2208. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90084-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dowling J.E. Chemistry of visual adaptation in the rat. Nature. 1960;188:114–118. doi: 10.1038/188114a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crouch R.K., Chader G.J., Wiggert B., Pepperberg D.R. Retinoids and the visual process. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996;64:613–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamb T.D., Pugh E.N., Jr. Dark adaptation and the retinoid cycle of vision. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2004;23:307–380. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Travis G.H., Golczak M., Moise A.R., Palczewski K. Diseases caused by defects in the visual cycle: Retinoids as potential therapeutic agents. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:469–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Von Lintig J., Kiser P.D., Golczak M., Palczewski K. The biochemical and structural basis for trans-to-cis isomerization of retinoids in the chemistry of vision. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mata N.L., Radu R.A., Clemmons R.C., Travis G.H. Isomerization and oxidation of vitamin A in cone-dominant retinas: A novel pathway for visual-pigment regeneration in daylight. Neuron. 2002;36:69–80. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00912-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleisch V.C., Schonthaler H.B., von Lintig J., Neuhauss S.C. Subfunctionalization of a retinoid-binding protein provides evidence for two parallel visual cycles in the cone-dominant zebrafish retina. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8208–8216. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2367-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J.S., Estevez M.E., Cornwall M.C., Kefalov V.J. Intra-retinal visual cycle required for rapid and complete cone dark adaptation. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:295–302. doi: 10.1038/nn.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Travis G.H., Kaylor J., Yuan Q. Analysis of the retinoid isomerase activities in the retinal pigment epithelium and retina. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;652:329–339. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-325-1_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J.S., Kefalov V.J. The cone-specific visual cycle. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011;30:115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaylor J.J., Yuan Q., Cook J., Sarfare S., Makshanoff J., Miu A., Kim A., Kim P., Habib S., Roybal C.N., et al. Identification of DES1 as a vitamin A isomerase in muller glial cells of the retina. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jastrzebska B., Palczewski K., Golczak M. Role of bulk water in the hydrolysis of rhodopsin’s chromophore. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:18930–18937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen M.H., Kuemmel C., Birge R.R., Knox B.E. Rapid release of retinal from a cone visual pigment following photoactivation. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4117–4125. doi: 10.1021/bi201522h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woodruff M.L., Wang Z., Chung H.Y., Redmond T.M., Fain G.L., Lem J. Spontaneous activity of opsin apoprotein is a cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 2003;35:158–164. doi: 10.1038/ng1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kefalov V.J., Estevez M.E., Kono M., Goletz P.W., Crouch R.K., Cornwall M.C., Yau K.W. Breaking the covalent bond—A pigment property that contributes to desensitization in cones. Neuron. 2005;46:879–890. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okawa H., Sampath A.P., Laughlin S.B., Fain G.L. ATP consumption by mammalian rod photoreceptors in darkness and in light. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:1917–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Emran F., Rihel J., Adolph A.R., Dowling J.E. Zebrafish larvae lose vision at night. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6034–6039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914718107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang X., Wang T., Jiao Y., von Lintig J., Montell C. Requirement for an enzymatic visual cycle in drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Molday R.S., Zhong M., Quazi F. The role of the photoreceptor abc transporter ABCA4 in lipid transport and stargardt macular degeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1791:573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsybovsky Y., Molday R.S., Palczewski K. The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA4: Structural and functional properties and role in retinal disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;703:105–125. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5635-4_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weng J., Mata N.L., Azarian S.M., Tzekov R.T., Birch D.G., Travis G.H. Insights into the function of rim protein in photoreceptors and etiology of Stargardt’s disease from the phenotype in ABCR knockout mice. Cell. 1999;98:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun H., Molday R.S., Nathans J. Retinal stimulates ATP hydrolysis by purified and reconstituted ABCR, the photoreceptor-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter responsible for Stargardt disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8269–8281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mata N.L., Weng J., Travis G.H. Biosynthesis of a major lipofuscin fluorophore in mice and humans with ABCR-mediated retinal and macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7154–7159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130110497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun H., Nathans J. Mechanistic studies of ABCR, the ABC transporter in photoreceptor outer segments responsible for autosomal recessive Stargardt disease. J. Bioenergy Biomembr. 2001;33:523–530. doi: 10.1023/A:1012883306823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhong M., Molday R.S. Binding of retinoids to ABCA4, the photoreceptor ABC transporter associated with Stargardt macular degeneration. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;652:163–176. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-325-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boyer N.P., Higbee D., Currin M.B., Blakeley L.R., Chen C., Ablonczy Z., Crouch R.K., Koutalos Y. Lipofuscin and N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine (A2E) accumulate in retinal pigment epithelium in absence of light exposure: Their origin is 11-cis-retinal. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:22276–22286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.329235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quazi F., Lenevich S., Molday R.S. ABCA4 is an N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylethanolamine importer. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:925. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Allikmets R., Singh N., Sun H., Shroyer N.F., Hutchinson A., Chidambaram A., Gerrard B., Baird L., Stauffer D., Peiffer A., et al. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:236–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cremers F.P., van de Pol D.J., van Driel M., den Hollander A.I., van Haren F.J., Knoers N.V., Tijmes N., Bergen A.A., Rohrschneider K., Blankenagel A., et al. Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy caused by splice site mutations in the Stargardt’s disease gene ABCR. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:355–362. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martinez-Mir A., Paloma E., Allikmets R., Ayuso C., del Rio T., Dean M., Vilageliu L., Gonzalez-Duarte R., Balcells S. Retinitis pigmentosa caused by a homozygous mutation in the stargardt disease gene ABCR. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:11–12. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fu Y., Zhong H., Wang M.H., Luo D.G., Liao H.W., Maeda H., Hattar S., Frishman L.J., Yau K.W. Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells detect light with a vitamin A-based photopigment, melanopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10339–10344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501866102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Panda S., Nayak S.K., Campo B., Walker J.R., Hogenesch J.B., Jegla T. Illumination of the melanopsin signaling pathway. Science. 2005;307:600–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1105121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walker M.T., Brown R.L., Cronin T.W., Robinson P.R. Photochemistry of retinal chromophore in mouse melanopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8861–8865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711397105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sexton T.J., Golczak M., Palczewski K., van Gelder R.N. Melanopsin is highly resistant to light and chemical bleaching in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20888–20897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamashita T., Ohuchi H., Tomonari S., Ikeda K., Sakai K., Shichida Y. Opn5 is a UV-sensitive bistable pigment that couples with Gi subtype of G protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:22084–22089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012498107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bi A., Cui J., Ma Y.P., Olshevskaya E., Pu M., Dizhoor A.M., Pan Z.H. Ectopic expression of a microbial-type rhodopsin restores visual responses in mice with photoreceptor degeneration. Neuron. 2006;50:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang F., Wang L.P., Brauner M., Liewald J.F., Kay K., Watzke N., Wood P.G., Bamberg E., Nagel G., Gottschalk A., et al. Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature. 2007;446:633–639. doi: 10.1038/nature05744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oberhauser V., Voolstra O., Bangert A., von Lintig J., Vogt K. NinaB combines carotenoid oxygenase and retinoid isomerase activity in a single polypeptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19000–19005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807805105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ross A.C., Gardner E.M. The function of vitamin A in cellular growth and differentiation, and its roles during pregnancy and lactation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1994;352:187–200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2575-6_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Napoli J.L. Biochemical pathways of retinoid transport, metabolism, and signal transduction. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996;80:S52–S62. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stephensen C.B. Vitamin A, infection, and immune function. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2001;21:167–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Drager U.C. Retinoic acid signaling in the functioning brain. Sci. STKE. 2006;2006:pe10. doi: 10.1126/stke.3242006pe10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maden M. Retinoic acid in the development, regeneration and maintenance of the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:755–765. doi: 10.1038/nrn2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Niederreither K., Dolle P. Retinoic acid in development: Towards an integrated view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:541–553. doi: 10.1038/nrg2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takahashi J., Palmer T.D., Gage F.H. Retinoic acid and neurotrophins collaborate to regulate neurogenesis in adult-derived neural stem cell cultures. J. Neurobiol. 1999;38:65–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199901)38:1<65::AID-NEU5>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Evans R.M. The molecular basis of signaling by vitamin A and its metabolites. Harvey Lect. 1994;90:105–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mark M., Ghyselinck N.B., Chambon P. Function of retinoid nuclear receptors: Lessons from genetic and pharmacological dissections of the retinoic acid signaling pathway during mouse embryogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006;46:451–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wolbach S.R., Howe P.R. Tissue change following deprivation of fat-soluble A vitamin. J. Exp. Med. 1925;42:753–777. doi: 10.1084/jem.42.6.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.West K.P., Jr. Vitamin A deficiency: Its epidemiology and relation to child mortality and morbidity. In: Blomhoff R., editor. Vitamin A in Health and Disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dowling J.E. Night blindness. Sci. Am. 1966;215:78–84. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1066-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sommer A. Vitamin A: Its effect on childhood sight and life. Nutr. Rev. 1994;52:S60–S66. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Misner D.L., Jacobs S., Shimizu Y., de Urquiza A.M., Solomin L., Perlmann T., de Luca L.M., Stevens C.F., Evans R.M. Vitamin A deprivation results in reversible loss of hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:11714–11719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191369798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cocco S., Diaz G., Stancampiano R., Diana A., Carta M., Curreli R., Sarais L., Fadda F. Vitamin A deficiency produces spatial learning and memory impairment in rats. Neuroscience. 2002;115:475–482. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Biesalski H.K. The significance of vitamin A for the development and function of the lung. Forum Nutr. 2003;56:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ross A.C. On the sources of retinoic acid in the lung: Understanding the local conversion of retinol to retinoic acid. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004;286:L247–L248. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00234.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vahlquist A. Role of retinoids in normal and diseased skin. In: Blomhoff R., editor. Vitamin A in Health and Disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1994. pp. 365–424. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Morley J.E., Damassa D.A., Gordon J., Pekary A.E., Hershman J.M. Thyroid function and vitamin A deficiency. Life Sci. 1978;22:1901–1905. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Livera G., Rouiller-Fabre V., Pairault C., Levacher C., Habert R. Regulation and perturbation of testicular functions by vitamin A. Reproduction. 2002;124:173–180. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen L., Khillan J.S. Promotion of feeder-independent self-renewal of embryonic stem cells by retinol (vitamin A) Stem Cells. 2008;26:1858–1864. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ziouzenkova O., Orasanu G., Sharlach M., Akiyama T.E., Berger J.P., Viereck J., Hamilton J.A., Tang G., Dolnikowski G.G., Vogel S., et al. Retinaldehyde represses adipogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Nat. Med. 2007;13:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nm1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chen N., Onisko B., Napoli J.L. The nuclear transcription factor RARα associates with neuronal RNA granules and suppresses translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20841–20847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802314200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aoto J., Nam C.I., Poon M.M., Ting P., Chen L. Synaptic signaling by all-trans retinoic acid in homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;60:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chytil F., Ong D.E. Mediation of retinoic acid-induced growth and anti-tumour activity. Nature. 1976;260:49–51. doi: 10.1038/260049a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Love J.M., Gudas L.J. Vitamin A, differentiation and cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1994;6:825–831. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yang Q., Graham T.E., Mody N., Preitner F., Peroni O.D., Zabolotny J.M., Kotani K., Quadro L., Kahn B.B. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005;436:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Basu T.K., Basualdo C. Vitamin A homeostasis and diabetes mellitus. Nutrition. 1997;13:804–806. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nau H., Chahoud I., Dencker L., Lammer E.J., Scott W.J. Teratogenicity of vitamin A and retinoids. In: Blomhoff R., editor. Vitamin A in Health and Disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1994. pp. 615–664. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Orfanos C.E., Zouboulis C.C., Almond-Roesler B., Geilen C.C. Current use and future potential role of retinoids in dermatology. Drugs. 1997;53:358–388. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smith F.R., Goodman D.S. Vitamin A transport in human vitamin A toxicity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976;294:805–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604082941503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Collins M.D., Mao G.E. Teratology of retinoids. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999;39:399–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Penniston K.L., Tanumihardjo S.A. The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;83:191–201. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Myhre A.M., Carlsen M.H., Bohn S.K., Wold H.L., Laake P., Blomhoff R. Water-miscible, emulsified, and solid forms of retinol supplements are more toxic than oil-based preparations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78:1152–1159. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Adams J. Structure-activity and dose-response relationships in the neural and behavioral teratogenesis of retinoids. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1993;15:193–202. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(93)90015-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nau H. Teratogenicity of isotretinoin revisited: Species variation and the role of all-trans-retinoic acid. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001;45:S183–S187. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.113720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Crandall J., Sakai Y., Zhang J., Koul O., Mineur Y., Crusio W.E., McCaffery P. 13-cis-retinoic acid suppresses hippocampal cell division and hippocampal-dependent learning in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5111–5116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306336101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sieving P.A., Chaudhry P., Kondo M., Provenzano M., Wu D., Carlson T.J., Bush R.A., Thompson D.A. Inhibition of the visual cycle in vivo by 13-cis retinoic acid protects from light damage and provides a mechanism for night blindness in isotretinoin therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:1835–1840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041606498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Voolstra O., Oberhauser V., Sumser E., Meyer N.E., Maguire M.E., Huber A., von Lintig J. NinaB is essential for drosophila vision but induces retinal degeneration in opsin-deficient photoreceptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:2130–2139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sun H., Nathans J. ABCR, the ATP-binding cassette transporter responsible for Stargardt macular dystrophy, is an efficient target of all-trans-retinal-mediated photooxidative damage in vitro. Implications for retinal disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11766–11774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010152200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kanan Y., Moiseyev G., Agarwal N., Ma J.X., Al-Ubaidi M.R. Light induces programmed cell death by activating multiple independent proteases in a cone photoreceptor cell line. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:40–51. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Masutomi K., Chen C., Nakatani K., Koutalos Y. All-trans retinal mediates light-induced oxidation in single living rod photoreceptors (dagger) Photochem. Photobiol. 2012;88:1356–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2012.01129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Maeda A., Maeda T., Golczak M., Palczewski K. Retinopathy in mice induced by disrupted all-trans-retinal clearance. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26684–26693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804505200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sparrow J.R., Cai B., Jang Y.P., Zhou J., Nakanishi K. A2E, a fluorophore of RPE lipofuscin, can destabilize membrane. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;572:63–68. doi: 10.1007/0-387-32442-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sparrow J.R., Boulton M. RPE lipofuscin and its role in retinal pathobiology. Exp. Eye Res. 2005;80:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.De S., Sakmar T.P. Interaction of A2E with model membranes. Implications to the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002;120:147–157. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vives-Bauza C., Anand M., Shirazi A.K., Magrane J., Gao J., Vollmer-Snarr H.R., Manfredi G., Finnemann S.C. The age lipid A2E and mitochondrial dysfunction synergistically impair phagocytosis by retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:24770–24780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800706200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhou J., Kim S.R., Westlund B.S., Sparrow J.R. Complement activation by bisretinoid constituents of RPE lipofuscin. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009;50:1392–1399. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Moiseyev G., Nikolaeva O., Chen Y., Farjo K., Takahashi Y., Ma J.X. Inhibition of the visual cycle by A2E through direct interaction with RPE65 and implications in stargardt disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17551–17556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008769107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Radu R.A., Hu J., Yuan Q., Welch D.L., Makshanoff J., Lloyd M., McMullen S., Travis G.H., Bok D. Complement system dysregulation and inflammation in the retinal pigment epithelium of a mouse model for Stargardt macular degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:18593–18601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Goodman D.S. Plasma retinol-binding protein. In: Sporn M.B., Boberts A.B., Goodman D.S., editors. The Retinoids. Volume 2. Academic Press, Inc.; Orlando, FL, USA: 1984. pp. 41–88. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rask L., Anundi H., Bohme J., Eriksson U., Fredriksson A., Nilsson S.F., Ronne H., Vahlquist A., Peterson P.A. The retinol-binding protein. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. Suppl. 1980;154:45–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Blomhoff R., Green M.H., Berg T., Norum K.R. Transport and storage of vitamin A. Science. 1990;250:399–404. doi: 10.1126/science.2218545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Quadro L., Hamberger L., Colantuoni V., Gottesman M.E., Blaner W.S. Understanding the physiological role of retinol-binding protein in vitamin A metabolism using transgenic and knockout mouse models. Mol. Aspects Med. 2003;24:421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zanotti G., Berni R. Plasma retinol-binding protein: Structure and interactions with retinol, retinoids, and transthyretin. Vitam. Horm. 2004;69:271–295. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(04)69010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Newcomer M.E., Ong D.E. Plasma retinol binding protein: Structure and function of the prototypic lipocalin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1482:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kawaguchi R., Yu J., Honda J., Hu J., Whitelegge J., Ping P., Wiita P., Bok D., Sun H. A membrane receptor for retinol binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science. 2007;315:820–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1136244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sun H., Kawaguchi R. The membrane receptor for plasma retinol-binding protein, a new type of cell-surface receptor. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011;288:1–41. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386041-5.00001-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kawaguchi R., Yu J., Ter-Stepanian M., Zhong M., Cheng G., Yuan Q., Jin M., Travis G.H., Ong D., Sun H. Receptor-mediated cellular uptake mechanism that couples to intracellular storage. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:1041–1051. doi: 10.1021/cb200178w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kawaguchi R., Zhong M., Kassai M., Ter-Stepanian M., Sun H. STRA6-catalyzed vitamin A influx, efflux and exchange. J. Membr. Biol. 2012;245:731–745. doi: 10.1007/s00232-012-9463-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Golczak M., Maeda A., Bereta G., Maeda T., Kiser P.D., Hunzelmann S., von Lintig J., Blaner W.S., Palczewski K. Metabolic basis of visual cycle inhibition by retinoid and nonretinoid compounds in the vertebrate retina. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9543–9554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708982200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]