Abstract

Recombinant formate dehydrogenase from the acetogen Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T, expressed in Escherichia coli, shows particular activity towards NADH-dependent carbon dioxide reduction to formate due to the relative binding affinities of the substrates and products. The enzyme retains activity over 2 days at 4°C under oxic conditions.

TEXT

Formate dehydrogenases (FDHs) catalyze the interconversion of CO2 and formic acid through an oxidoreductive process (Fig. 1) (1). Consequently, when catalyzing CO2 reduction, they are of interest for the sequestration of CO2 and for the production of formic acid as a stabilized form of hydrogen fuel and as a source of commodity chemicals. In many bacteria and eukaryotes, FDHs catalyze the final step of catabolic processes in which formate is oxidized to CO2 (2). The ability of certain members of this class, such as FDH from Candida boidinii in particular, to efficiently regenerate NADH in conjunction with formate oxidation has been a research focus (3).

Fig 1.

The reaction catalyzed by formate dehydrogenase, coupled to the redox of NAD.

Acetogens are known to possess a number of pathways distinct from those found in the other species. FDHs present in acetogens are known to take part in a carbon fixation metabolic pathway producing acetate (the Eastern branch of the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway), in which the first step involves reduction of CO2 to formate (4). Several FDHs are known to catalyze CO2 reduction under appropriate conditions (5–9). Those enzymes from acetogenic and related anaerobes, such as Moorella thermoacetica and Clostridium pasteurianum, are better than other FDHs as reduction catalysts but also show similar catalytic efficiency toward formate oxidation and are considered highly oxygen labile, requiring anaerobic expression and purification as well as anoxic assay conditions (10, 11). Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T (equivalent to ATCC BAA-624T and DSM 15243T) was isolated from the sediment of an agricultural settling lagoon after enrichment with CO as the substrate and is an obligate anaerobe that can grow autotrophically with H2 and CO2 or CO (fixing carbon via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway) (12, 13). Therefore, when the gene of a selenocysteine-containing formate dehydrogenase H (FDHH) from the acetogen Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T was first identified, it was suggested that FDHH would catalyze the conversion of CO2 to formate (14, 15). Here we report the first production of FDHH and its catalytic preference for CO2 reduction, as well as its tolerance for oxic conditions.

Cloning, expression, and purification of FDHs.

The overexpression and purification of recombinant FDHH from the Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T (FDHH_CloCa) was carried out, along with that of NAD+-dependent recombinant FDH from Candida boidinii (FDH_CanBo), in order to compare expression and activity of formate dehydrogenases that take part in distinct metabolic pathways. The DNA sequences for the FDHH_CloCa (UniProt E2IQB0) and FDH_CanBo (UniProt O13437) genes were codon optimized for expression in Escherichia coli (commercially synthesized by GeneArt, Germany), with the exception of residue 139Sec, which was modified to 139Cys for FDHH_CloCa to avoid the need for use of a different expression system with selenoprotein-expressing elements. Plasmid DNAs were then reconstructed with the respective FDH genes inserted into the T7 promoter vector pETMCSIII for subsequent expression with an N-terminal His6 tag (16). The successful reconstruction of the plasmid DNAs was confirmed by PCR coding region amplification and DNA sequencing. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain for expression. The transformed cells for both FDHH_CloCa and FDH_CanBo were grown overnight in 50 ml of LBA medium (Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin) at 37°C in a shaking incubator with full aeration. Overexpression of both FDHH_CloCa and FDH_CanBo was efficient under the conditions tested, with no need for induction. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 15 min), and approximately 0.5 g of cells were obtained. Cell pellets were resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4], 500 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole). Resuspended cells were lysed using a high-pressure homogenizer (Emulsiflex-B15; Avestin, Canada), and the soluble fraction of the cell lysate was collected by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 1 h, 4°C). Proteins were purified by metal ion affinity chromatography (His GraviTrap; GE Healthcare). The supernatant of the cell lysate was loaded onto the column and washed with 10× the column volume of binding buffer, followed by washing with 20× the column volume of washing buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4], 500 mM NaCl, and 40 mM imidazole). Proteins were eluted with 4 ml of elution buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4], 500 mM NaCl, and 500 mM imidazole) and concentrated with a YM-10 centrifugation filter (Millipore). Final concentrated proteins were stored in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 4°C. The yields of FDHH_CloCa and FDH_CanBo were 0.4 mg and 3.3 mg per 50 ml of cell culture, respectively. The higher yield of the latter reflects its greater overexpression level and larger proportion in the soluble protein fraction. All purification procedures were carried out at 4°C under normal oxic conditions with no atmosphere control. The expression levels of the formate dehydrogenases were assessed by 20% SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A).

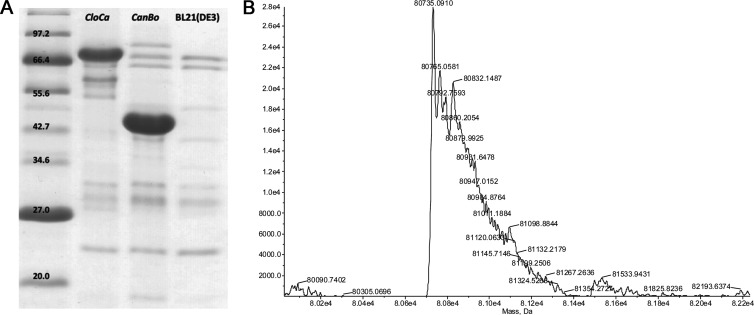

Fig 2.

Twenty percent SDS-PAGE of purified FDHH_CloCa (80.7 kDa) and FDH_CanBo (41.3 kDa), as well as the background from blank BL21(DE3) cells (A), and the mass spectrum of FDHH_CloCa (B).

The production of the formate dehydrogenases was also confirmed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS). Protein mass spectrometry was carried out by direct injection onto an Agilent 1100 series LC/MSD (mass spectrometer detector) time-of-flight (TOF) instrument running a mobile phase of 50:50 (vol/vol) 0.1% formic acid in MeCN–0.1% aqueous formic acid. The calculated molecular masses based on protein sequence for the N-terminally His6-tagged FDH_CanBo and FDHH_CloCa were 41,324 and 80,739 Da, respectively. Mass spectrometry gave molecular masses of 41,324 (data not shown) and 80,735 Da (Fig. 2B) for the expressed FDH_CanBo and FDHH_CloCa, respectively.

Several formate dehydrogenases, as well as many oxidoreductases, are known to contain Mo-pterin cofactors (17, 18); however, there have been cases where W replaces Mo in the cofactor (19). Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Perkin-Elmer) revealed the presence of W in an FDHH_CloCa sample, which indicates that this enzyme, like the acetogenic Moorella thermoacetica formate dehydrogenase, contains a W cofactor.

Catalytic activities of FDHs.

The purified FDHs were assessed for their catalytic activities. The initial velocities for enzyme catalysis in both directions were studied for these FDHs by monitoring NADH absorbance at 340 nm. It is impractical to define a reaction equilibrium position for the assay, since CO2 is a substrate or product and the system is open. However, an excess of either formate or bicarbonate was present in order to ensure that the assays were initiated far from equilibrium. An initial assay was carried out with 1 μM enzyme in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) at 37°C with an excess (0.1 M) of sodium formate or sodium bicarbonate (depending on the direction monitored) and 0.2 mM NAD+ or NADH, respectively. Formate dehydrogenase activity was assessed by measuring the change in absorbance at 340 nm due to the reduction of NAD+ or oxidation of NADH (Shimadzu UV 2450 spectrophotometer equipped with a thermostated cell compartment).

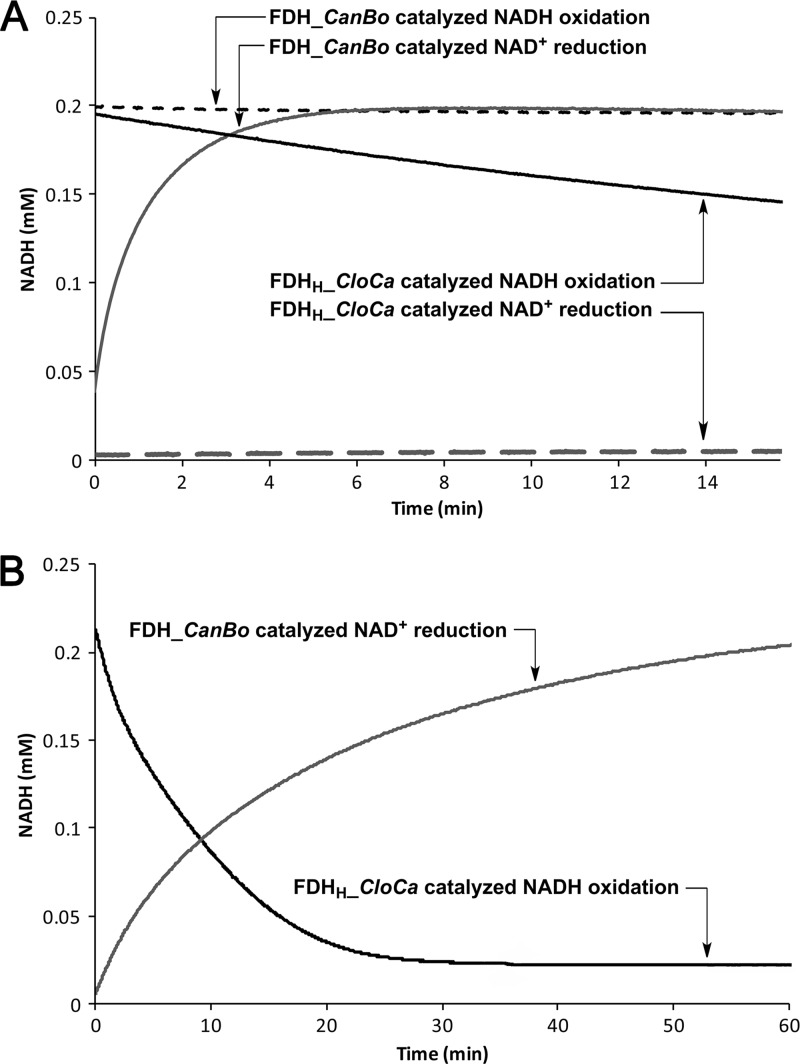

The two FDHs displayed opposite catalytic behaviors under the conditions tested (Fig. 3A). The eluent from the purification of nontransformed E. coli BL21(DE3) cell lysate was used as a control and presented no conversion (data not shown). FDH_CanBo showed high activity in NAD+ reduction in the presence of formate, as expected. On the contrary, when presented with NADH with an excess of bicarbonate, it was inactive. Conversely, FDHH_CloCa showed minimal activity toward NAD+ reduction but was active toward NADH oxidation. Under the conditions tested, the activities of these two enzymes seems to be consistent with what is known about their metabolic roles. The progress of the preferred reaction for each enzyme was more directly compared using the aforementioned assay conditions but with 0.1 μM FDH_CanBo and 5.0 μM FDHH_CloCa, under which circumstances similar initial reaction rates were observed (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

Catalytic activities of FDHs: all with 1 μM enzyme (A) or FDH_CanBo-catalyzed NAD+ reduction with 0.1 μM enzyme and FDHH_CloCa-catalyzed NADH oxidation with 5 μM enzyme (B).

The FDHs were further characterized by monitoring their catalytic activities over a range of substrate concentrations. By maintaining an excess of one substrate and varying the concentration of the other, Michaelis-Menten kinetics were observed. Assays were performed for a range of NAD+ (0.02 to 0.75 mM) or NADH (0.02 to 0.6 mM) concentrations in 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 6.8) at 37°C with 0.1 M sodium formate or sodium bicarbonate and 0.1 μM FDH_CanBo or 1 μM FDHH_CloCa.

From the kinetic data presented in Table 1, it can be seen that both enzymes show similar binding affinities to their dinucleotide substrate; however, FDH_CanBo exhibits a much higher turnover. This translates into an approximately 50-fold-higher efficiency of FDH_CanBo than of FDHH_CloCa in their respective “preferred” directions.

Table 1.

FDH kinetic parameters

| Parameter | Value for indicated substrate |

|

|---|---|---|

| FDHH_CloCa for NADH | FDH_CanBo for NAD+ | |

| Km (mM) | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Vmax (μM min−1) | 5.0 | 38 |

| kcat (s−1) | 0.08 | 6.3 |

| kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | 1.6 | 90 |

In order to gain a better understanding of the differences in this preference of the two FDHs, the binding constants of the dinucleotide products were also calculated (Table 2). If a product is added to an assay mixture at initiation, it will compete with a substrate in binding to the enzyme. Since catalysis of the reverse reactions in each case is negligible, the Michaelis constant of the product reduces to the binding constant, which has the significance of an inhibition constant (KP).

[S] is the substrate concentration, [P] is the product concentration, vi is the initial velocity, Vmax is the maximum initial velocity for the substrate, Km is the Michaelis constant for the substrate, and KP is the Michaelis constant for the product.

Table 2.

FDH formate and nicotinamide binding affinities

| Substrate/product | Binding affinity, mM |

|

|---|---|---|

| FDH_CanBo | FDHH_CloCa | |

| NAD+ | 0.07 (Km) | 0.75 (KP) |

| NADH | 0.01 (KP) | 0.05 (Km) |

| Formate | 3.7 (Km) | >100 (KP) |

For a fixed concentration of NADH (0.1 mM), the initial velocity of FDH_CanBo-catalyzed NAD+ reduction was measured for a range of NAD+ concentrations (0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer [pH 6.8] and 0.1 M sodium formate). The saturation kinetics observed allowed for calculation of an apparent Km (Km,app) (0.74, Eadie-Hofstee), which was used to calculate the binding constant of NADH: Km,app = Km{1 + ([P]/KP)}.

Based on the above equation, the KP of FDH_CanBo for NADH was calculated at 0.01 mM (Table 2). In the case of FDHH_CloCa, it was found that a larger concentration of product (NAD+) was required to significantly reduce the initial velocity, which suggested that the affinity of the enzyme for the product dinucleotide is very low. This was confirmed with saturation kinetics observed for various NADH concentrations when 1.5 mM NAD+ was present in the assay (0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer [pH 6.8] and 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate). The KP was calculated at 0.75 mM (Km,app = 0.15 mM, Eadie-Hofstee), which is approximately 15-fold higher than the Km for NADH with this enzyme. The Km of FDH_CanBo for formate was measured at 3.7 mM (0.6 to 100 mM sodium formate, 0.1 M sodium phosphate [pH 6.8], 37°C, and 0.5 mM NAD+). In the case of FDHH_CloCa, however, when formate at a concentration of 100 mM was added to the assay mixture (0.1 M sodium phosphate [pH 6.8], 37°C, 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate, and 0.2 mM NADH), the initial reaction velocity remained the same. This suggests that the binding constant of FDHH_CloCa for formate (KP,HCOO−) has to be greater than 100 mM.

Despite the fact that both enzymes show a preference to bind NADH, it is noteworthy that for FDH_CanBo, the preference is less (Km,NAD+ is 7-fold greater than KP,NADH). This is combined with a relatively high binding affinity for formate, making the enzyme an efficient catalyst of formate oxidation. For FDHH_CloCa, the preference for NADH is greater (KP,NAD+ is 15-fold greater than Km,NADH), which, combined with a low binding affinity for formate, makes this enzyme a more efficient catalyst for formate production through CO2 reduction.

Concluding remarks.

For the first time, recombinant formate dehydrogenase from the Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T was expressed and purified using an E. coli host cell. FDHH_CloCa and FDH_CanBo prepared in the same way displayed different catalytic behaviors. While FDH_CanBo was more efficient in NAD+ reduction, FDHH_CloCa displayed a strong preference for NADH oxidation. Relative to FDH_CanBo, FDHH_CloCa shows a 10-fold-lower binding affinity for NAD+ and a binding affinity at least 30-fold lower for formate. These lower affinities for both products of NADH-dependent CO2 reduction make it a much better catalyst for formate production. Expression was carried out aerobically, and the enzyme retained catalytic activity under normal oxic assay conditions, thus presenting relative robustness in comparison to related enzymes that are reported to be oxygen sensitive. Currently, we are investigating the activity of FDHH_CloCa in E. coli host cells, where formate production could serve in a useful role in alleviating fossil fuel dependence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was undertaken within the CSIRO Energy Transformed Flagship Cluster on Biofuels with support from the CSIRO Flagship Collaboration Fund and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Free Radical Chemistry and Biotechnology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 November 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Kato N, Sahm H, Wagner F. 1979. Steady-state kinetics of formaldehyde dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase from a methanol-utilizing yeast, Candida boidinii. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Enzymol. 566:12–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Overkamp KM, Kötter P, van der Hoek R, Schoondermark-Stolk S, Luttik MAH, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT. 2002. Functional analysis of structural genes for NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 19:509–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. San K-Y, Berrios-Rivera SJ, Bennett GN. May 2010. Recycling system for manipulation of intracellular NADH availability. US patent 7,709,261

- 4. Ljungdahl LG, Wood HG. 1969. Total synthesis of acetate from CO2 by heterotrophic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 23:515–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu Y, Jiang ZY, Xu SW, Wu H. 2006. Efficient conversion of CO2 to formic acid by formate dehydrogenase immobilized in a novel alginate-silica hybrid gel. Catal. Today 115:263–268 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miyatani R, Amao Y. 2002. Bio-CO2 fixation with formate dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and water-soluble zinc porphyrin by visible light. Biotechnol. Lett. 24:1931–1934 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parkinson BA, Weaver PF. 1984. Photoelectrochemical pumping of enzymatic CO2 reduction. Nature 309:148–149 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reda T, Plugge CM, Abram NJ, Hirst J. 2008. Reversible interconversion of carbon dioxide and formate by an electroactive enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:10654–10658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ruschig U, Müller U, Willnow P, Höpner T. 1976. CO2 reduction to formate by NADH catalyzed by formate dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas oxalaticus. Eur. J. Biochem. 70:325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scherer PA, Thauer RK. 1978. Purification and properties of reduced ferredoxin-CO2 oxidoreductase from Clostridium pasteurianum, a molybdenum iron-sulfur protein. Eur. J. Biochem. 85:125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thauer RK. 1972. CO2-reduction to formate by NADPH. The initial step in the total synthesis of acetate from CO2 in Clostridium thermoaceticum. FEBS Lett. 27:111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liou JS-C, Balkwill DL, Drake GR, Tanner RS. 2005. Clostridium carboxidivorans sp. nov., a solvent-producing clostridium isolated from an agricultural settling lagoon, and reclassification of the acetogen Clostridium scatologenes strain SL1 as Clostridium drakei sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:2085–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paul D, Austin FW, Arick T, Bridges SM, Burgess SC, Dandass YS, Lawrence ML. 2010. Genome sequence of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T. J. Bacteriol. 192:5554–5555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bruant G, Levesque M-J, Peter C, Guiot SR, Masson L. 2010. Genomic analysis of carbon monoxide utilization and butanol production by Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7T. PLoS One 5:e13033 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ragsdale SW, Pierce E. 2008. Acetogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 fixation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784:1873–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neylon C, Brown SE, Kralicek AV, Miles CS, Love CA, Dixon NE. 2000. Interaction of the Escherichia coli replication terminator protein (Tus) with DNA: a model derived from DNA-binding studies of mutant proteins by surface plasmon resonance. Biochemistry 39:11989–11999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gladyshev VN, Khangulov SV, Axley MJ, Stadtman TC. 1994. Coordination of selenium to molybdenum in formate dehydrogenase H from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:7708–7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwarz G, Mendel RR. 2006. Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis and molybdenum enzymes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57:623–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ljungdahl LG, Andreesen JR. 1978. Formate dehydrogenase, a selenium-tungsten enzyme from Clostridium thermoaceticum. Methods Enzymol. 53:360–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]