Abstract

Neurons exhibit long-term excitability changes necessary for maintaining proper cell and network activity in response to various inputs and perturbations. For instance, the adult crustacean pyloric network can spontaneously recover rhythmic activity after complete shutdown resulting from permanent removal of neuromodulatory inputs. Dissociated lobster stomatogastric ganglion (STG) neurons have been shown to spontaneously develop oscillatory activity via excitability changes. Rhythmic electrical stimulation can eliminate these oscillatory patterns in some cells. The ionic mechanisms underlying these changes are only partially understood. We used dissociated crab STG neurons to study the ionic mechanisms underlying spontaneous recovery of rhythmic activity and stimulation-induced activity changes. Similar to lobster neurons, rhythmic activity spontaneously develops in crab STG neurons. Rhythmic hyperpolarizing stimulation can eliminate, but more commonly accelerate the emergence of stable oscillatory activity depending on Ca++ influx at hyperpolarized voltages. Our main finding is that up-regulation of a Ca++-current and down-regulation of a high-threshold K+-current underlies the spontaneous homeostatic development of oscillatory activity. However, because of a non-linear dependence on stimulus frequency, hyperpolarization-induced oscillations appear to be inconsistent with a homeostatic regulation of activity. We find no difference in the activity patterns or the underlying ionic currents involved between neurons of the fast pyloric and the slow gastric mill networks during the first ten days in isolation. Dynamic-clamp experiments confirm that these conductance modifications can explain the observed activity changes. We conclude that spontaneous and stimulation-induced excitability changes in STG neurons can both result in intrinsic oscillatory activity via regulation of the same two conductances.

Keywords: calcium, potassium currents, stomatogastric, excitability, homeostasis, oscillations

Neuronal excitability regulation is important for the maintenance of stable activity patterns in individual neurons (Davis and Bezprozvanny 2001; Desai et al. 1999; Franklin et al. 1992; Hong and Lnenicka 1995; Li et al. 1996; Linsdell and Moody 1994; Turrigiano et al. 1994) and in neuronal networks (Galante et al. 2001; Luther et al. 2003; Turrigiano and Nelson 2004). This homeostatic plasticity allows neuronal and network activity to remain within functional limits during their normal operation and in response to perturbations or injury. Regulation of neuronal excitability and intrinsic property can be induced by electrical stimulation (Cudmore and Turrigiano 2004; Franklin et al. 1992; Garcia et al. 1994; Golowasch et al. 1999a; Li et al. 1996; Turrigiano et al. 1994), ionic conductance perturbations (Desai et al. 1999; Linsdell and Moody 1994), development and growth (Spitzer et al. 2002) and trauma (Darlington et al. 2002), and may play a role in memory formation (Daoudal and Debanne 2003; Marder et al. 1996; Zhang and Linden 2003).

The rhythmical activity pattern of the pyloric network in the stomatogastric ganglion (STG) of crustaceans is conditional upon neuromodulatory release from neurons located in central ganglia. When these inputs are permanently removed, activity ceases but a stable new activity pattern spontaneously develops within hours to days (Golowasch et al. 1999b; Luther et al. 2003; Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 1998). It has been suggested that this recovery of rhythmic activity occurs via up- and down-regulation of voltage-dependent ionic conductances and the consequent acquisition of oscillatory properties by some of the network components (Golowasch et al. 1999b; Mizrahi et al. 2001; Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 2002). Indeed, this recovery correlates with some ionic conductance changes (Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 2002; Mizrahi et al. 2001). Neuromodulators may also have suppressive trophic effects on the excitability of STG neurons in the intact network, suppression that may be released after removal of neuromodulatory input by decentralization (Le Feuvre et al. 1999; Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 1998, 2000).

Neuronal intrinsic excitability is affected by patterned electrical activity in isolated STG neurons in culture (Turrigiano et al. 1994) and in neurons in situ (Golowasch et al. 1999a). Excitability changes can also occur spontaneously both in isolated STG neurons in culture in response to cell dissociation (Turrigiano et al. 1995) or in the intact ganglion in response to decentralization (Golowasch et al. 1999b; Mizrahi et al. 2001; Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 2002). To understand how network activity evolves in response to persistent perturbations (such as the removal of central inputs essential for the generation of the activity) it is key to understand the dynamics and plasticity of the voltage-dependent ionic currents of its component neurons. In cultured STG neurons spontaneous activity changes have been correlated with changes in a TEA-sensitive K+ current and in various inward currents (Turrigiano et al. 1995). However, the conductance changes induced by prolonged rhythmic stimulation (Turrigiano et al. 1994) have not been identified.

Here we study the ionic mechanisms involved in spontaneous and activity-induced recovery of oscillatory activity in adult dissociated crab STG neurons. We find the same ionic currents to be modified in both cases, although probably via different signaling pathways. Dynamic clamp experiments confirm that the ionic currents modified are sufficient to produce the observed activity changes. Surprisingly, during the first ten days after dissociation neurons from the pyloric and gastric networks cannot be distinguished on the basis of neuronal activity, ionic conductance changes or response to stimulation.

Materials and Methods

Animals and solutions

Adult male crabs Cancer borealis (carapace length >15 cm) were obtained from local fish markets (Newark, NJ) and maintained in saltwater aquaria at 12-14° C. The following solution compositions were used (concentrations all in mM): standard Cancer saline solution (440.0 NaCl, 11.0 KCl, 13.0 CaCl2, 26.0 MgCl2, 5.0 Maleic acid, 11.2 Trizma base, pH 7.4-7.5); salt supplement solution (743.7 NaCl, 16.4 KCl, 24.7 CaCl2, 50.2 MgCl2 and 10.0 Hepes, pH 7.4); zero Ca++/zero Mg++ dissociation solution (440.0 NaCl, 11.0 KCl, and 10.0 Hepes, pH 7.4); barium saline solution (440.0 NaCl, 11.0 KCl, 12.9 BaCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 26.0 MgCl2, 5.0 Maleic acid, 11.2 Trizma base, pH 7.4-7.5). Mn++ saline was identical to barium saline with Mn++ substituting for Ba++. All chemicals were obtained from Fisher Scientific Co. (Fairlawn, NJ) unless otherwise indicated. The sodium channel blocker Tetrodotoxin, TTX (EMD, Biosciences) was used at 0.1 μM.

Cell Dissociation

Adult STG neurons were cultured following a protocol similar to those used by Turrigiano et al (1993) Glowik et al (1997) and Swensen et al (2000). Crabs were anesthetized by cooling during 15-30 minutes on ice. The foregut was removed and the STG, with a portion of the nerves attached, were isolated as previously described (Selverston et al. 1976) in a sterile laminar flow hood. The dissected nerves and ganglia were rinsed 4-5 times in sterile Cancer saline containing 0.1 mg/ml gentamicin (MP Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohio). The ganglia were pinned down in sterile Sylgard-lined Petri dishes, incubated in sterile zero Ca++/zero Mg++ saline plus 2 mg/ml of the proteolytic enzyme Dispase (Gibco, Germany) for 6 hrs at room temperature, and then transferred to an incubator at 12°C overnight in the same solution. Individual somata were then removed from the ganglion by aspiration with glass micropipettes coated inside with goat serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and with fire-polished tips. Dissociated neurons were plated individually onto uncoated 35mm plastic Nunclon culture dishes in sterile salt supplement solution diluted 1:1 with sterile Leibowitz L-15 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and then placed in an incubator at 12-14°C for the duration of the culturing period. Saline was not replaced during this time.

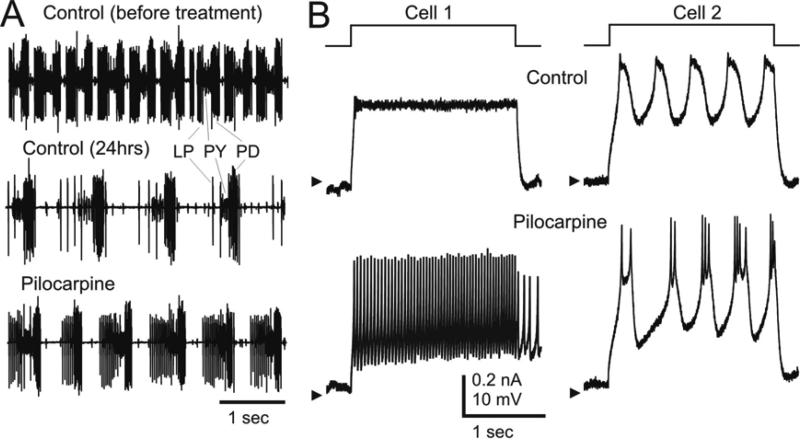

Cells were discarded if they showed blebs protruding from the cell body and if they were not firmly attached to the substrate. Cells with primary neurite and cell bodies firmly attached to the substrate were found to be the healthiest and produced the most stable recordings. To verify that the proteolytic treatment did not unduly affect the cells during dissociation, we performed two separate tests. In one, we followed the enzymatic treatment as described above and then tested the response of the entire pyloric network to neurmodulators. Figure 1A shows one example in which the pyloric activity (characterized by the alternating bursting of the LP, PY and PD neurons) was recorded extracellularly from the pyloric network's main motor nerve (the lateral ventricular nerve, lvn). Control before enzymatic treatment is shown in the top trace. After 24 hrs of proteolytic treatment (Control – 24 hrs, middle trace) a clear effect of the enzymatic treatment can be seen by comparing the top two traces. Immediately before the mechanical dissociation was performed (i.e. 24 hrs after the beginning of Dispase treatment) 100 μM Pilocarpine was applied. A response to the neuromodulator typical of this system (Nusbaum and Beenhakker 2002) can be observed. This is characterized by an increase in the number of spikes per burst and in the frequency of the pyloric rhythm. As a second test, we applied 1-10 μM Pilocarpine to isolated STG neurons 1-5 days after enzymatic treatment and mechanical dissociation. Approximately 50% of the neurons responded by changing their activity pattern (Fig. 1B,C). Note that not all neurons in the intact STG respond to Pilocarpine (Swensen and Marder 2001). Thus, both of these tests confirm that neurons retain many of their biophysical properties through the proteolytic and mechanical dissociation procedure, as has been reported previously (Panchin et al. 1993; Turrigiano and Marder 1993).

Figure 1. Dissociation preserves biophysical properties.

A. Extracellular recordings from the lateral ventricular nerve (lvn) showing the action potentials of three main pyloric motor neurons (LP, PY, PD). The top trace (Control before treatment) is from a freshly dissected preparation. The middle trace (Control, 24 hrs) was recorded in normal saline after protease treatment (Methods). The bottom trace (Pilocarpine) was recorded immediately after the middle trace was recorded, showing a strong neuromodulatory response to 100 μM Pilocarpine after enzymatic treatment. B. Recordings from two STG neurons 24 hrs after enzymatic treatment and mechanical dissociation (Methods). Neurons were impaled with one electrode and stimulated with a +0.1 nA current pulse (top traces). Voltage responses before (Control) and after application of the neuromodulator Pilocarpine (5 μM) are shown below. Neuronal input resistance was >10 times the electrode resistance and thus no attempt was made to subtract electrode resistance in these recordings. Arrowheads indicate –55 mV (left) and –63 mV (right).

Cell identification

A subset of the experiments was performed with identified neurons of the STG. Because the gastric network is known to oscillate at a frequency several times slower than the pyloric network (Nusbaum and Beenhakker 2002), we hypothesized that gastric neurons, if they become oscillatory in dissociated culture, would oscillate at a lower frequency than dissociated pyloric neurons. Thus, we aimed to distinguish only between neurons belonging to the pyloric network, the gastric network and other neurons not belonging to either of these networks. For this purpose we followed the established protocol for cell identification (Selverston et al. 1976). A map of the STG neurons was drawn and neurons successively impaled with one electrode and identified. The tips of the theta filament electrodes used for recording (WPI, Sarasota, FL) were filled with either the dye Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by dipping the back of the electrode in the dye solution for 1-2 minutes and backfilling the rest of the micropipette with 1 M KCl. Neurons identified as pyloric were filled by passing -10 nA for 10-30 seconds with one dye and then neurons identified as gastric were filled similarly with the other dye. After this, the dissociation procedure was followed as described above.

Electrophysiological recordings

Single (SEVC) or two electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) performed with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) was used to measure ionic currents. Data were digitized and then analyzed using the pClamp9.0 software (Molecular Devices). Recordings were obtained using Citrate-filled microelectrodes (4 M K-Citrate + 20 mM KCl). Current injection electrodes had resistances 12-18 MΩ and voltage recording electrodes 15-25 MΩ. The preparation was grounded using an Ag/AgCl wire connected directly to the bath or via an agar bridge (4% agar in 0.6 M K2SO4 + 20 mM KCl). No differences were observed with or without the agar bridge. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20-22°C), approximately 1 hour after transferring the cells to the recording setup.

K+ currents were measured in standard Cancer saline + 0.1 μM TTX and separated into 2 components: high-threshold, voltage-gated currents, IK, activated with 500 msec long depolarizing membrane potential steps from a holding voltage of –40 mV, and the voltage-gated transient current, IA, that was activated with depolarizing steps from a holding voltage of –80 mV (Golowasch and Marder 1992; Graubard and Hartline 1991). In crabs the high-threshold component is known to consist of two conductances, a delayed-rectifier, IKd, partially blocked by TEA and a Ca++-dependent conductance, IK(Ca), that is completely blocked by 10-20 mM TEA and also indirectly by Cd++, which blocks the underlying Ca++ current (Golowasch and Marder 1992; Hurley and Graubard 1998). The high-threshold currents activated during the IA activation protocol were removed by subtracting the currents measured from a holding potential of –40 mV from those obtained from a holding voltage of –80 mV. The hyperpolarization-activated current, Ih, was measured using 4 second long hyperpolarizing pulses from a holding potential of –40 mV. The Ca++ current, ICa, was measured with depolarizing membrane potential steps from a holding voltage of –40 mV after blocking outward currents. For this, one electrode, filled with 4 M K-Citrate + 20 mM KCl, was used to record voltage, while the second, filled with 1 M TEA + 1 M CsCl (12-25 MΩ resistance) was used to inject current. Additionally, 20 or 100 mM TEA + 0.1 μM TTX was added to the standard Cancer saline bathing solution. Furthermore, in some experiments we measured Ca tail currents at –80mV induced with pulses to depolarized membrane potentials. The K+ equilibrium potential in these cells was found to be very close to –80mV (not shown). At that voltage ICa tails inactivate slowly, allowing us to determine ICa largely uncontaminated by K+ currents. To construct I-V plots ICa was measured by averaging the current 20-30msec after the onset of the voltage pulse (vertical arrow in Fig. 6C). Currents were leak subtracted using the p/n subtraction method included in the data acquisition software, with the holding voltage during leak pulses at –40mV and applying 5 sub-pulses of opposite polarity. For all voltages tested, these leak subtraction sub-pulses remain in the linear range of the current-voltage relationship. The current carried by Ba++ through Ca++ channels was also sometimes measured. For this the Barium saline described above plus 20 mM TEA and 0.1 μM TTX was used.

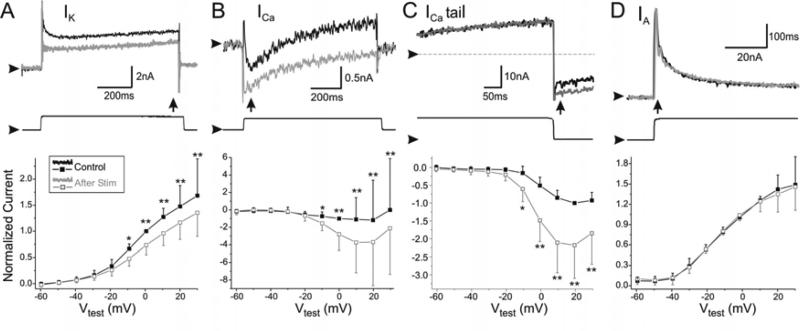

Figure 6. Effect of patterned activity on ionic currents.

A. Top panel shows raw traces of high-threshold K+ currents, IK, recorded at +10 mV in the normal Ca++ saline + 20 mM TEA before (Control) and after 60 minutes of 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation. Middle panel shows a raw voltage trace used to elicit the control current trace above. Arrowhead indicates –40 mV. Bottom panel shows the mean (± SD) I-V relationship of normalized currents recorded at steady state (vertical arrow) and shown as above. P < 0.004, n = 6. IK was normalized by currents measured in Control conditions at 0 mV. B. Top panel shows typical recordings of a Ca++ current at 0mV in Cancer saline containing 20 mM TEA, 0.1 μM TTX. The neurons were also TEA and Cs+ loaded to reduce K+ currents to a minimum. The transient inward current (Control) increased in amplitude after 30 minutes of rhythmic stimulation (After Stim). Middle panel shows a raw voltage trace used to elicit the control current trace above. Arrowhead indicates –40 mV. Bottom panel shows the control I-V plots of mean (± SD) peak normalized ICa recorded at 20-30 msec after pulse onset (vertical arrow), and the I-V plot after ~30 min 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation. P = 0.011, n = 15. ICa was normalized by currents measured in Control conditions at +10 mV. C. Top panel shows raw current traces at the end of an 800 msec long depolarizing test pulse to 0 mV followed by a voltage drop to –80mV before (Control) and after 30 min 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation. Currents were recorded in same conditions as in B. Middle panel shows the test voltage trace. Arrowhead indicates –80mV. Botton panel shows the I-V plots (control and after stimulation) of mean (± SD) normalized tail ICa recorded at 20 msec after the beginning of the hyperpolarizing voltage step (vertical arrow). P = 0.001, n = 10. ICa tail was normalized by currents measured in Control conditions at +10 mV. D. Top panel shows raw traces of a typical transient A, IA, current elicited at 0 mV before (Control) and after 60 minutes stimulation. Middle panel shows a raw voltage trace used to elicit the control current trace above. Arrowhead indicates –80 mV. Bottom panel shows the I-V plot of the mean (± SD) normalized peak IA recorded at the peak as shown in top panel (vertical arrow). P = 0.918, n = 7. IA was normalized by currents measured in Control conditions at 0 mV. Horizontal arrowheads in top panels of A-D indicate 0 nA. All currents are leak subtracted. All statistical comparisons were performed with Two-way RM ANOVAs. Statistical test used was a Two-Way RM ANOVA. Bonferroni post-hoc analysis was used for multiple pair-wise comparisons: ** < 0.001; * < 0.05.

We estimated the conductance of K+ currents, Ih and ICa by dividing the current measured at +10, –120 and 0 mV, respectively, by their corresponding driving forces, using EK = –80 mV, Eh = –25 mV and ECa = +100 mV (Golowasch and Marder 1992). In all cases we also determined conductance and midpoint of voltage-dependent activation by fitting conductance vs voltage curves with a Boltzman equation (see equations below). IKd and Ih were measured at steady state, while IA and ICa were measured at the peak (25-80 msec after pulse onset). Currents within a given experimental group were normalized by dividing all currents by the current value measured in control at 0 mV for all K+ currents (Figs. 6, 7 and 8), at +10 mV for ICa (Figs. 6 and 7) and +20 mV for ICa tail (Fig. 6C). We chose these voltages to maximize the numbers of cells we could use for our analyses because not all cells could be voltage clamped to higher levels. The leak conductance was measured either as 1/Rin, where Rin is the input resistance measured with small hyperpolarizing current steps in current clamp, or as the slope of the I-V curve in the voltage range where no voltage-dependent currents appear to be activated (–40 to –60 mV).

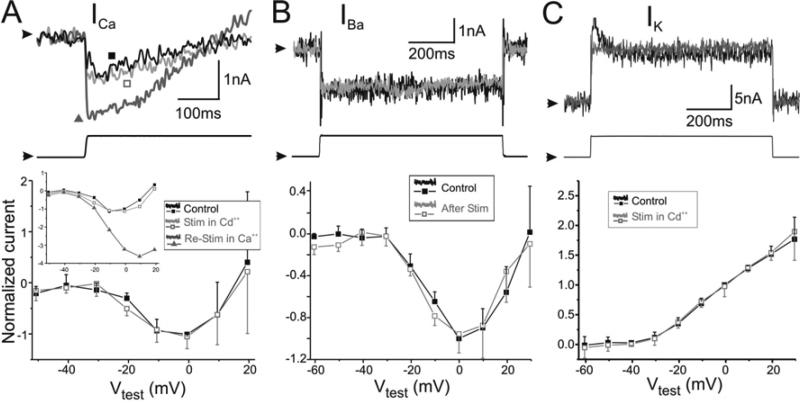

Figure 7. Role of Ca++ influx on activity-dependent conductance regulation.

Unidentified STG neuron current recordings in normal Ca++ saline before and after stimulation with 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing current pulses was carried out under conditions that eliminate Ca++ influx. ICa was recorded in 100 mM TEA saline after loading cells with TEA and Cs+ (Methods). High-threshold K+ current, IK, was recorded in normal saline + 20 mM TEA. Top panels show a sample raw current trace recorded under each of the applied test conditions, arrowheads indicate 0 nA. Middle panels show the raw voltage trace used to elicit the current traces above. Arrowheads indicate –40 mV. Lower panels show the I-V plots of normalized currents averaged (± SD) across cells before (Control) and after stimulation. ICa and IBa were normalized by currents measured in Control conditions at +10 mV. IK was normalized by currents measured in Control conditions at 0 mV. All statistical comparisons were performed with Two-way RM ANOVAs. A. Top two panels show the initial 370 msec of the Ca++ current (above) elicited by a depolarizing step from –40mV to +10mV (below) and recorded in normal Ca++ conditions. Control (■) trace was recorded before stimulation began, Stim in Cd++ (□) trace was recorded after 30 min of stimulation in the presence of 200 μM Cd++ and washout of Cd++, Re-Stim in Ca++ (▲) trace was recorded after washout of Cd++ and additional 40 min stimulation in normal Ca++ conditions. Bottom panel shows the average I-V plots of the normalized peak ICa measured 25 msec after the onset of the depolarizing test pulse, recorded before stimulation (Control) and after stimulation in (and after washout of) Cd++ (Stim in Cd++). P = 0.308, n = 5. Inset shows an example of a single cell recorded under the 3 conditions indicated above. B. Top panels show a non-inactivating IBa (above) elicited by a test pulse from –40 mV to +10 mV (below) before (Control) and after 45 min of rhythmic stimulation (After Stim). Bottom panel shows the I-V plot of the steady state average (± SD) normalized currents. P = 0.300, n = 5. C. Top panels show IK (above) elicited by a test pulse from –40 mV to 0 mV (below), before (Control) and after 40 min of rhythmic stimulation in (and washout of) 200 μM Cd++ (Stim in Cd++). Bottom panel shows the I-V plot of the steady state average (± SD) and normalized currents. P = 0.618, n = 5.

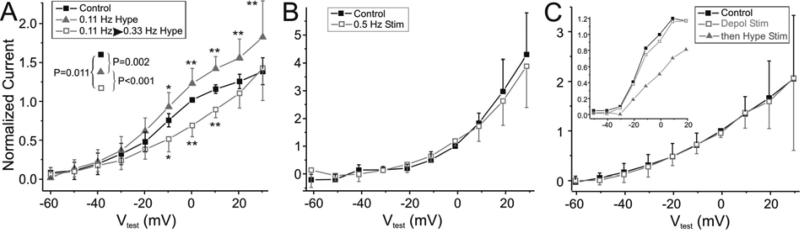

Figure 8. Effect of stimulation pattern.

Unidentified neuron high-threshold K+ current recordings were performed in normal Ca++ saline + 20 mM TEA. I-V plots were made with current measurements obtained at the end of 800 msec long voltage steps (see Fig. 6A) from a holding voltage of –40 mV. All currents were normalized by the current measured in Control conditions at 0 mV. All statistical comparisons were performed with Two-way RM ANOVAs. A. Control measurements were obtained before any stimulation (solid black squares). Neurons were then stimulated with 8 sec hyperpolarizing pulses every 9 sec for approximately 25 minutes (0.11 Hz hype, grey triangles), followed by approximately 40 minutes of the standard 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation (0.11→0.33 Hz Hype, open grey squares). The pairwise statistical comparisons between the three treatments is shown as P values (n = 6). Pairwise statistical comparisons of the origin of the differences among the treatments used the Bonferroni post-hoc test and is indicated as ** < 0.001; * < 0.05. B. Control current measurements were obtained before stimulation (Control, solid black squares) and after stimulation with hyperpolarizing 1 sec long pulses at 0.5 Hz (0.5 Hz Stim, open grey squares). P = 0.779, n = 5. C. Control current measurements were obtained before stimulation (Control, solid black squares) and after stimulation in voltage-clamp with depolarizing 1 sec pulses from –40 mV to –10 mV at the standard 0.33 Hz frequency (Depol Stim, open grey squares). P = 0.526, n = 5. In 2 occasions depolarizing stimulation was followed by 40 min stimulation with the standard 1 sec hyperpolarizing pulses at 0.33 Hz. Measurements of one of these cells is shown in the inset (then → Hype Stim, open grey squares).

Neurons were allowed to rest for 15-20 minutes after impalement before data acquisition was initiated. Prolonged neuronal stimulation was started only after ionic currents showed stable amplitudes for several minutes, which were then used as control.

Capacitance was determined from the areas of the capacitive current transient resulting from 10 ms long hyperpolarizing membrane potential steps from a holding voltage of –40 or –50 mV. In some neurons we estimated the electrotonic length, L, by applying a low amplitude hyperpolarizing current pulse around the resting potential of the cells. This was repeated 20 times and the traces averaged to reduce noise. Double-exponential fits to the voltage change produced the membrane time constant, τ0, and an equalizing time constant, τ1, which were used to determine L according to (Rall 1977).

Stimulation protocols

Neuronal activity was altered by applying 1 second long hyperpolarizing current pulses at 0.33 Hz, driving neurons to a membrane potential of approximately –120 mV (peak response, see Fig. 4E). This protocol has been found to be effective in modifying the spontaneous activity of cultured lobster STG neurons before (Turrigiano et al. 1994). Current level was adjusted often during the stimulation period to maintain this level of hyperpolarization. Control ionic current measurements were recorded in voltage clamp immediately prior to the beginning. Currents were measured again after a 45-60 minute stimulation period.

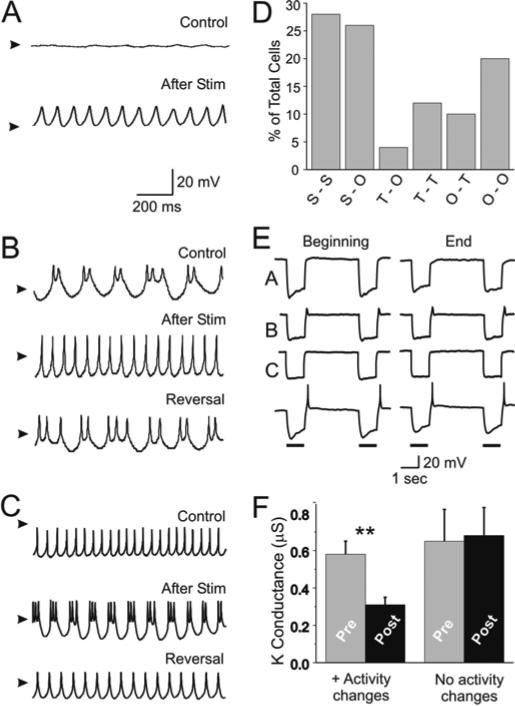

Figure 4. Rhythmic stimulation-induced neuronal activity changes.

Examples of activity transitions resulting from rhythmic stimulation for 45-60 minutes with hyperpolarizing current pulses (Methods). 50 neurons were recorded in normal Cancer saline before (Control) and after stimulation (After Stim). A. Silent to oscillatory transition. Silent activity (Control) changed to rapid oscillatory activity after 60 minutes of rhythmic stimulation. We classify the stimulus-induced state as oscillatory because of the high duty cycle. The activity shown was elicited with +0.1 nA current injection. Arrowheads indicate –55 mV. B. Oscillatory to tonic transition. Oscillatory activity (with bursts of 2 to 3 action potentials per oscillation) was induced by a +0.4 nA current injection (Control). 60 minutes of stimulation let to a change to tonic firing (After Stim). Reversal to oscillatory activity took approximately 2 hours of no stimulation. Arrowheads indicate –60 mV. C. Tonic to oscillatory transition. +0.4 nA depolarizing current was used in all traces. Tonic firing (Control) changed to oscillatory activity after 60 minutes of rhythmic stimulation (After Stim). The pattern reversed to tonic firing after approximately 2 hours of no stimulation (Reversal). Arrowheads indicate –45 mV. D. Percentage of neurons (from a total of 50 cells) that changed activity between silent (S), tonic (T) and oscillatory (O) after 45-60 minutes of rhythmic stimulation. E. Voltage changes during the period of hyperpolarizing stimulation used to induce activity changes. Horizontal bars below traces indicate hyperpolarizing current injection. Traces labeled A-C correspond to those cells whose activity states are shown in panels A-C in this figure. The bottom trace corresponds to an oscillatory cell whose activity did not change as a result of prolonged stimulation. Notice the presence of PIR in this cell and in trace B, but no PIR in traces A and C. F. High threshold K+ conductance measured at +10 mV in normal saline before (grey bars, Pre) and after 45-60 minutes of stimulation (black bars, Post) in neurons that showed a clear activity change with patterned stimulation (left; ** P = 0.005, n = 6, paired t-Student test) and in neurons that showed no difference in activity pattern (right; P = 0.375, n = 6, paired t-Student test).

Analysis

SigmaStat (Aspire Software International, Leesburg, VA), Origin (OriginLab, Natick, MA), and CorelDraw (Corel Corp., Canada) software packages were used for statistical and graphical analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed using either a standard Two-Way ANOVA, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on Ranks for non-normally distributed populations or a Repeated Measures (RM) ANOVA. Results of statistical analysis were considered significant if the significance level P was below α = 0.05. All error bars shown and the reported variability around the averages correspond to standard deviations (SD).

Dynamic clamp experiments

A NI PCI-6070-E board (National Instruments, Austin, TX) was used for current injection in dynamic clamp experiments. Data acquisition was performed using the Digidata board and pClamp software as described above. The dynamic clamp software was developed by Farzan Nadim and collaborators (available for download at http://stg.rutgers.edu/software.htm) in the LabWindows/CVI software environment (National Instruments, Austin, TX) on a Windows XP operating system. Ionic currents that showed an approximately average effect in response to prolonged rhythmic stimulation were recorded and fitted with Hodgkin & Huxley-type equations. We used the measured parameters that produced the best fit to reproduce ionic conductances that were then added to or subtracted from a neuron using dynamic clamp (Sharp et al. 1993) adjusting only the maximum conductances to match the effects of rhythmic stimulation.

The equations we used to characterize each ionic current IX are:

where gmaxX is the maximum conductance of the current, m is the activation gate, h is the inactivation gate, Vm is the membrane potential and Ex is the equilibrium potential of ion x that each current is specific for. τmX and τhX are the time constants with which the m and h gates respectively evolve in time towards their respective steady states mX∞ and hX∞. These steady states are governed each by two voltage dependent parameters V1/2X and sX that are listed in Table 1. q is an exponent that takes value 1 if the ionic current exhibits voltage-dependent inactivation and value 0 if it does not.

Table 1.

Ionic current parameters used for dynamic clamp experiments.

| τm (ms) | τh (ms) | V1/2m (mV) | V1/2h (mV) | sm (mV) | sh (mV) | q | Eion (mV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICa | 1 | 300 | –13 | –16 | –9 | +10 | 1 | +100 |

| IKSt | 100 | NA | –20 | NA | –9 | NA | 0 | –80 |

| IKTr | 1 | 70 | –23 | –34 | –4 | 4 | 1 | –80 |

Results

Spontaneous activity changes with time in culture

Our dissociation procedure typically yielded around 20-40% of the 25-26 STG neurons found (Kilman and Marder 1996) in each ganglion and, with careful suction, the soma and a relatively long segment of the major neurite could be removed. Figure 2B-D illustrates the morphology of 3 typical neurons with differing neurite lengths immediately after dissociation (Day 0 and 1) and 6 days later. By the sixth day in culture some neurons grew wide lamellipodia (Fig. 2B), others tended to grow one or more long processes with smaller lamellipodia extending from the ends (Fig. 2D), while others showed a combination of relatively wide lamellipodia and long processes (Fig. 2C). Any significant outgrowth originated almost exclusively from the neurite stump (Figs. 2C, D) however short it may have been (see Fig. 2B). Only very small extensions were occasionally observed growing directly out of the soma (Fig. 2C, Day 6). No obvious correlation was observed between the length of the original neurite and subsequent outgrowth morphology or electrical activity.

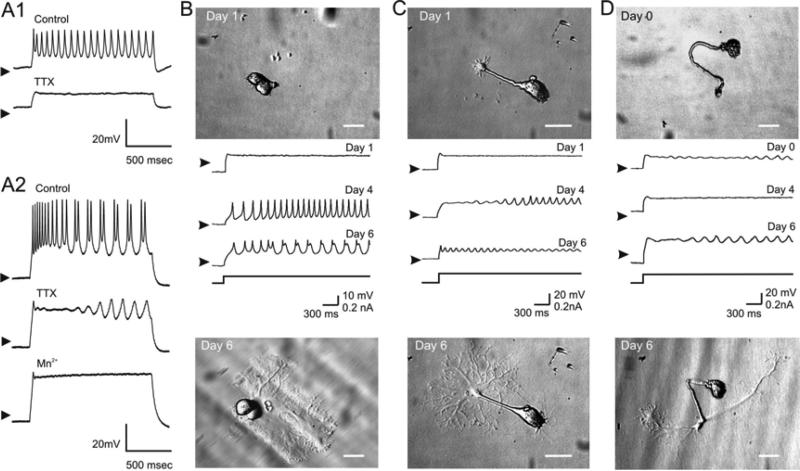

Figure 2. Neuronal activity classification and spontaneous activity.

A1. Intracellular recordings with 2 microelectrodes of the neuronal activity of a tonic firing cell on day 6 in response to a +0.1 nA current pulse. 0.1 μM TTX abolished all spiking in this and 6 other similar neurons. n = 7. A2. Similar recording as in A1 of an oscillatory neuron on day 5 after dissociation in response to a +0.4 nA current pulse. 0.1 μM TTX abolished all spiking but not the slow oscillations in this and 8 other similar neurons neurons, while Mn++ saline (Methods) abolished all oscillations. n = 9. B-D. Dissociated STG neurons were photographed and impaled with one electrode at different days in culture. The neurons showed little growth at day 0-1. B. At day 1 in culture this neuron is silent, becomes tonically active by day 4, and develops oscillatory activity by day 6 with action potentials riding on the slow oscillations of the membrane potential. On day 6 this neuron shows an extensive lamellipodium with many small processes growing at its edges. Arrowheads indicate –53 mV. C. This neurons shows incipient growth at the end of the neuritic stump on day 1 that grows into a broad lamellipodium by day 6 from which several projections with extensive dendritic processes originate. The neuron is silent on day 1 and begins to generate membrane potential oscillations classified as oscillatory activity (high duty cycle) that increases in frequency at day 6. Arrowheads indicate –63 mV. D. On day 6 this neuron extends two long projections from the original stump (Day 0) and a relatively modest dendritic outgrowth emerging from them. Oscillatory activity appears immediately after dissociation, becomes silent by day 4 and then resumes oscillatory by day 6. Arrowheads indicate –66 mV.

Neurons were classified according to the pattern of activity they expressed. Three types of electrical activity were readily distinguishable from the first day in culture when the cultured neurons were depolarized with low amplitude current injection: Silent, Tonic or Oscillatory. Neurons that responded passively to all depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current injection levels were classified as Silent (Day 1 in Fig. 2B, C). Tonic neurons were those that exhibited fast, transient depolarizations having a duty cycle ≤0.2 (Fig. 2A1, top trace, and Fig. 2B, Day 4) and that could be blocked with 0.1-1 μM TTX (Fig. 2A1, second trace). Oscillatory activity was defined as slow, low amplitude depolarizations having a duty cycle >0.2 (Fig. 2A2, first and second traces, also see Day 6 in Fig. 2B-D), resistant to TTX treatment (Fig. 2A2, second trace) and sensitive to Ca++ current blockers such as Mn++ (Fig. 2A2, third trace) or Cd++ (not shown) . The oscillations recorded on days 4 and 6 of Figure 2C are considered to be at a transition between tonic and oscillatory states and were classified as oscillatory. Duty cycle was defined as the duration of a depolarizing event (action potential or slow oscillation) relative to the period of an oscillation measured at 50% of the maximum oscillation amplitude.

None of the neurons recorded during the initial 10 days in culture expressed spontaneous activity without some depolarizing current and all neurons were tested with depolarizing current steps of various amplitudes. On day 0 most neurons (81%) are Silent, 14% of the neurons showed tonic firing of action potentials and a very small percentage (<5%) of the nearly 350 neurons we recorded from expressed oscillatory activity (Fig 3A).

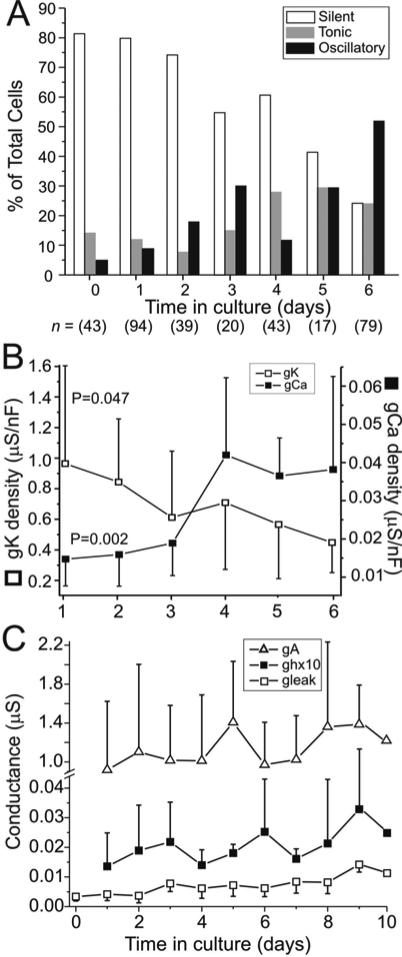

Figure 3. Spontaneous progression of activity and ionic conductances in culture.

A. Neurons classified as silent, tonic or oscillatory were counted on successive days in cell culture and the percentage of each category is plotted as a function of time. A progressive decrease of silent neurons and increase in both tonic and oscillatory neurons is observed. B. Ca++ and high-threshold K+ conductance density changes. The changes observed in these conductances over the first 6 days in culture are statistically significant (gCa: P = 0.002, n = 38; gK: P = 0.047, n = 65). C. A, h and leak current conductance changes. Peak gA was measured at 20-30 msec after the onset of a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV. gh was measured at the end of 4 sec long hyperpolarizing voltage steps to  120 mV. The values of gh were scaled up 10 fold to increase visibility. No statistically significant change in either gA or gh could be detected (gA: P = 0.654, n = 62; gh: P = 0.313, n = 59). gleak showed a statistically significant increase with time in culture (P < 0.001, n = 139) but this disappeared when the density values were considered (not shown). All statistical comparisons were made using the Kruskal-Wallis One Way ANOVA on Ranks. Data show means ± SD.

120 mV. The values of gh were scaled up 10 fold to increase visibility. No statistically significant change in either gA or gh could be detected (gA: P = 0.654, n = 62; gh: P = 0.313, n = 59). gleak showed a statistically significant increase with time in culture (P < 0.001, n = 139) but this disappeared when the density values were considered (not shown). All statistical comparisons were made using the Kruskal-Wallis One Way ANOVA on Ranks. Data show means ± SD.

Figure 3A shows that during days 0-3 in culture the silent state of activity was dominant, but the proportion of oscillatory neurons steadily increased as time progressed. The proportion of tonic neurons began to increase at day 3, while the proportion of silent neurons steadily decreased. The proportion of silent neurons continued to decrease throughout the initial 7 days, while that of oscillatory neurons steadily increased (with the exception of day 4). Instead, the proportion of tonically firing neurons seemed to reach a plateau on day 4 (Fig 3A). The rate of change of neuronal activity we observed was slower than that previously observed in cultured lobster neurons (Turrigiano et al. 1995). This may be due to the fact that we incubated our dissociated cells at 12°C instead of 20°C and/or to species differences.

To determine whether any of the activity changes correlate with STG neuron identity, we recorded from 37 additional neurons, classified into pyloric and gastric type (see Methods). Of these, 25 produced oscillations as defined above at days 2-8 in culture. The average oscillation frequency of the identified pyloric neurons was 3.65 ± 2.01 Hz (n = 14) while the average oscillation frequency of the identified gastric neurons was 2.95 ± 1.43 Hz (n = 11). Thus, the average oscillation frequency of the gastric neurons was somewhat lower than that of the pyloric neurons but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.342, t-Student test).

Spontaneous conductance changes with time in culture

To understand the contributions of ionic currents to the activity changes described above, we measured individual ionic currents at different times in culture and estimated their conductance. Figures 3B,C show the evolution of 5 different ionic conductances over up to 10 days in cell culture. When data are available we show conductance density changes over time rather than simply conductance changes to remove possible effects of growth. Only two of these showed statistically significant changes over that period (Fig. 3B) after normalizing by the capacitance of the cell: gCa, which increased by 159% (P = 0.002, n = 38), and the high threshold outward current gK that includes both a delayed rectifier and a Ca++-dependent K+ current (Golowasch and Marder 1992), which decreased by 54% (P = 0.047, n = 65, Fig. 3B). gleak increased by 79% (P <0.001, n = 139, Fig. 2C) but when normalized by cell capacitance the increase was reduced to only 15% and was not statistically significant (P = 0.777, n = 32). Thus, the change in leak conductance can probably be explained simply by the growth of the cell, while both gCa and gK changes appear to be related to changes in neuronal activity as these changes correlate with the progression from Silent to Tonic to Oscillatory activity (Fig. 3A). In contrast, gA and gh (Fig. 3C) increased by approximately 30% between day 1 and day 10 in culture, but these changes were not statistically significant (P = 0.654, n = 62; P = 0.313, n = 59, respectively; all the above reported statistical tests were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis One Way ANOVA on Ranks). We did not measure the capacitance in most of the neurons in which gA and gh were measured. However, an increase of conductance density of these two currents with age in culture is not likely because the average capacitance during this period increased by the same amount as these conductances (~25%). Surprisingly, the increase in capacitance during the first week in culture (cm on day 1 = 0.437 ± 0.154 nF, cm on day 7 = 0.548 ± 0.238 nF) was not statistically significant (P = 0.106, n = 87) similar to what was observed by Turrigiano et al. (1995). Furthermore, the electrotonic length of these neurons is relatively short (thus neurons are electrotonically compact) and not significantly different between day 1, when there is virtually no growth (L = 1.67 ± 0.61, n = 16) and day 6, when extensive growth is apparent (see Fig. 2B-D; L = 1.73 ± 0.781, n = 8, P = 0.842, t-Student test). From these results we conclude that neurons at these stages grow by extensively stretching the existing membrane rather than by incorporating significant amounts of new membrane.

To determine whether the conductances changes described above correlate with STG neuron identity, we recorded gCa from (7 pyloric and 7 gastric neurons, ages 1 and 6 days in culture. We found no statistically significant difference between pyloric and gastric neurons (P = 0.841, t-Student test). However, we found a statistically significant difference between ages 1 (0.007 ± 0.002) and 6 days (0.024 ± 0.014; P = 0.012, t-Student test) of the pooled data, confirming the results described above for non-identified cells. We also measured gK, gA and gh from 30 additional identified neurons (16 pyloric neurons and 14 gastric neurons). We grouped all neurons aged 5-7 days in culture and compared pyloric vs gastric neurons. No statistically significant difference in any of the three conductances between the two cell types was observed (P = 0.366, 2-way ANOVA), with gK = 0.30 ± 0.34 μS (Pyloric) vs 0.23 ± 0.15 μS (Gastric), gA = 0.93 ± 0.65 μS (Pyloric) vs 0.77 ± 0.53 μS (Gastric), gh = 0.020 ± 0.009 μS (Pyloric) vs 0.018 ± 0.008 μS (Gastric).

Activity changes induced by patterned stimulation

The changes in activity patterns and the accompanying conductance changes described above, as well as previous observations in cultured lobster STG neurons (Turrigiano et al. 1994), suggest that isolated STG neurons follow a set course of spontaneous conductance changes and consequent modifications of activity that may be genetically predetermined. However, while a neuron may be on a predetermined course to ultimately become an oscillator, it may also be able to modify its pattern of activity as a function of the inputs it may receive (Cudmore and Turrigiano 2004; Franklin et al. 1992; Garcia et al. 1994; Golowasch et al. 1999a; Li et al. 1996; Turrigiano et al. 1994). We tested this possibility in our crab STG neurons by rhythmically stimulating them with current pulses and measuring possible changes in their patterns of activity. We found that in response to stimulation with hyperpolarizing current pulses (to bring the Vm from the resting potential to approximately –120 mV) the majority of cells (60%) did not change their activity pattern (Fig. 4D) remaining either silent (28%), tonic (12%) or oscillatory (20%). We refer to this as no change in excitability. Similar to previous observations in lobster STG neurons (Turrigiano et al. 1994) we observed a small set of oscillatory neurons (10%) that reduced their excitability to tonic firing (Fig. 4B, D). We were surprised to find that 30% of the stimulated neurons switched from either silent to oscillatory (26%, Fig. 4A, D) or tonic to oscillatory activity (4%, Fig. 4C, D) because this was not observed by Turrigiano et al (1994) in their study of lobster STG neurons. We assume these changes in activity to reflect an enhancement of neuronal excitability. We observe no difference in the resting potential, Vrest, of neurons that change activity with stimulation (Vrest = –69.1 ± 8.9mV, n = 11) from those neurons that do not change activity (Vrest = –65.5 ± 3.8mV, n = 11, P = 0.397, unpaired t-Student test). Each set of neurons produced a slight but statistically significant depolarization in response to patterned stimulation (neurons with change: ΔVrest = +6.1 ± 5.8 mV, P < 0.001; neurons without change: ΔVrest = +6.6 ± 6.6 mV, P < 0.001, unpaired t-Student test). This depolarization, however, is indistinguishable between these two groups (P = 0.525, n=22, unpaired t-Student test). Furthermore, we see no difference in the depolarization whether cells increased their excitability (Silent or Tonic to Oscillatory transitions, Fig. 4D) or decreased their excitability (Oscillatory to Tonic transitions, Fig. 4D, P = 0.958, unpaired t-Student test). From this we conclude that the slight depolarization observed in stimulated cells is a non-specific effect of stimulation.

In contrast to what was shown by Turrigiano et al (1994) we found no consistent correlation of any of these activity changes with the presence of a measurable post-inhibitory rebound (PIR) in these neurons. Fig. 4E shows the stimulation-induced membrane potential changes during the ‘beginning’ and ‘end’ of the stimulation period used to induce activity changes. The traces marked A-C correspond to the cells whose results are shown in panels A-C in this figure. The last trace, showing a relatively large PIR capped with an action potential, corresponds to an oscillatory neuron whose activity did not change with stimulation. In fact, most of the stimulated crab STG neurons shown in Fig. 4 (59%) express no measurable PIR at all (see traces A and C in Fig. 4E). We found that neurons that do not show a change in activity induced by patterned stimulation generate a PIR on average almost twice as large (4.5 ± 7.2 mV, n = 30) as those that do (2.7 ± 3.5 mV, n = 16), but this difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.363, unpaired t-Student test). As can be seen in all 4 examples shown in Fig. 4E, there was no major change in PIR properties or amplitude during the course of the stimulation.

Interestingly, none of the recorded neurons showed a transition from a silent to a tonic (or from a tonic to a silent) pattern of activity, suggesting a lack of sensitivity to patterned stimulation of those currents responsible for the generation of action potentials. Alternatively, in these cells some of the intermediate signaling molecules leading from the detection of membrane potential changes to the modification of the ionic currents responsible for the changes in activity may be absent. In all cases where recordings could be held long enough (2-4 hours) reversal of the activity pattern was always significantly slower than the induction phase and almost always partial. We rarely observed a complete reversal of these effects. Figures 4B and C show the only two examples (of 28 cases) we obtained of almost complete reversal of activity, and in both it took approximately 2.5 hours to complete.

It is important to note that the ability for neurons to regulate activity in an activity-dependent manner did not appear to be related to the age of the neurons in culture but rather to their activity state at the time of stimulation. A similar fraction (40%) of “young” neurons (ages 1-4 days in culture) and “old” neurons (31%, ages 5-8 days in culture) could be induced to change their state of activity. However, most stimulated tonic (average age = 5.3 days) and oscillatory (average age = 3.5 days) neurons were older than stimulated silent (average age = 1.1 days) cells simply because of the spontaneous progression in activity observed in culture (see Fig. 3A).

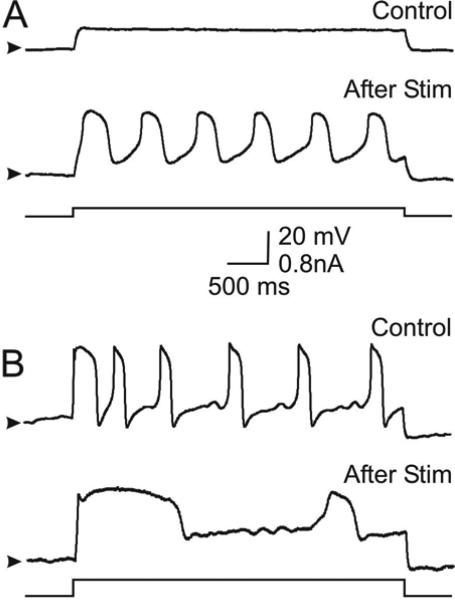

Within the relatively simple activity pattern categories we have classified these neurons into, there is a wide range of variability in terms of action potential frequency, duration and amplitude, slow wave oscillation frequency and amplitude, threshold current required to elicit patterns of activity, etc. We reasoned that this variability may be related to the expression of large, variable amplitude outward currents (Golowasch et al. 1999a) and that reducing their amplitude may make the activity patterns more uniform and reveal a more consistent effect of rhythmic stimulation on neuronal activity. When outward K+ current amplitudes were reduced with 20 mM TEA in the bath we did indeed observe a reduction in the variability of the activity states (Fig. 5). As shown before by Turrigiano and Marder (1993) in lobster isolated STG neurons, in the presence of TEA, most crab STG neurons showed a tendency to generate slow oscillations with relatively long depolarizations (Fig. 5B, Control, n = 9/15) while all others were silent (Fig 5A, Control, n = 6/15) before rhythmic stimulation was begun. When these neurons were rhythmically stimulated 100% of the initially silent neurons developed slow and large amplitude oscillations (Fig. 5A, After Stim), 100% of the initially oscillatory neurons increased the duration of the slow depolarizations by 83% from 319 ± 138 msec to 584 ± 369 msec (P = 0.030, n = 9, Fig. 5B, After Stim), increased their amplitude by 40% from 24.4 ± 14.3 mV to 34.1 ± 14.2 mV (P < 0.001, n = 8, Fig. 9B, left panel), and also increased their oscillation period by 170% from 473 ± 314 msec to 1284 ± 936 msec (P = 0.046, n = 6, see Fig. 5B and 9B, left panel). Period was calculated on longer recordings than shown in Fig. 5. Comparisons were made with unpaired t-Student tests.

Figure 5. Rhythmic stimulation-induced changes in neuronal activity in reduced outward currents.

Neurons were bathed in 20 mM TEA to reduce the dominant outward currents. In the presence of TEA 40% of the cells were initially silent and 60% were initially oscillatory in response to a small depolarizing current pulse. A. Example of one of the 6/15 neurons that shifted their activity from silent (Control) to oscillatory (After Stim) upon 40 min of rhythmic hyperpolarizing stimulation. Arrowheads indicate –67 mV. Current injection: +0.1 nA. B. Example of one of the 9/15 neurons that show oscillatory behavior upon depolarization (+0.4 nA) in control conditions. After 45 min rhythmic hyperpolarizing stimulation the neuron displays larger amplitude and lower frequency bursts (After Stim). Arrowheads indicate –60 mV. Bottom traces in A and B show the depolarizing current steps (baseline = 0 nA).

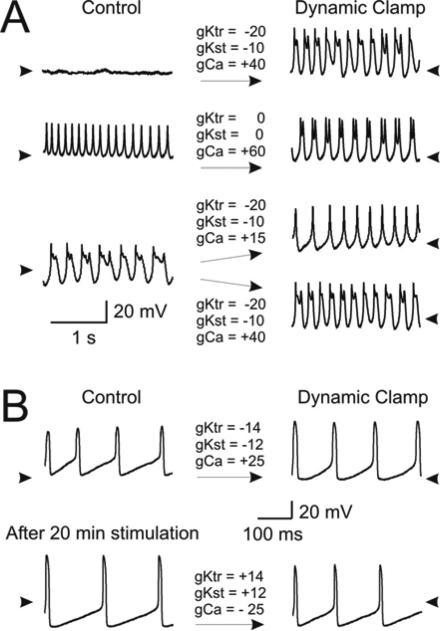

Figure 9. Dynamic clamp experiments.

Activity changes were elicited by dynamic clamp modifications of the high-threshold K+ and the Ca++ conductance (right panels) comparable to the effects on these conductances of prolonged rhythmic stimulation. Activity was elicited by small depolarizing current injections and depended on the amplitude of the injected current and on the intrinsic properties of the specific neuron recorded. Values above arrows are maximum conductance values in nS of dynamic clamp injected currents. A plus sign corresponds to an increase (and a minus sign to a decrease) in conductance. The two high-threshold K+ conductance components (transient, gKtr, and sustained, gKst) were varied together. The remaining parameters that specify each current are given in Table 1. A. Top panel: Activity of a 3 day old neuron during +0.8 nA current injection. A switch from silent (Control) to oscillatory (Dynamic clamp) was induced by increasing gCa and reducing gK. Arrowheads indicate –45 mV. Middle panel: Activity of a 2 day old neuron (left) during +0.1 nA current injection. Activity switched from tonic firing (Control) to oscillatory (Dynamic clamp) by increasing gCa only. Arrowheads indicate –50 mV. Bottom panel: Same neuron as in top panel but with slightly larger current injection (+0.9 nA) elicited oscillatory activity. Switching from oscillatory (Control) to either tonic firing (Dynamic clamp, top) or higher frequency and amplitude oscillatory (Dynamic clamp, bottom) depended on the gCa level provided the K+ conductance was reduced. Arrowheads indicate –45 mV. B. Recordings from a neuron at day 7 in 20 mM extracellular TEA. All traces show activity during +0.4 nA current injection. Control amplitude of oscillations (Top left) was markedly increased by reducing both components of gK and increasing gCa with dynamic clamp (top right). Stimulating the neuron rhythmically with hyperpolarizing pulses for 20 minutes (bottom left, dynamic clamp off) also markedly increased the amplitude. Dynamic clamp injection (bottom right) of currents with reversed polarity from that used before stimulation greatly reversed the effects of stimulation towards control levels. Arrowheads indicate –60 mV.

These changes indicate that, in general cultured STG neurons increase their excitability with patterned stimulation (from either silent, tonic firing or weak oscillatory to robust oscillatory activity) under these conditions, and have the ability to also increase their excitability in normal saline conditions (Fig. 4A, C, D). This can be interpreted as a homeostatic mechanism for the long-term recovery of oscillatory properties that complements the spontaneous tendency for neurons to become oscillators (Fig. 3A). However, once oscillatory activity is achieved, a certain degree of flexibility remains and neurons can revert to tonic (but not to silent) activity depending on the intrinsic properties of the cell (see also Turrigiano et al. 1994) and (see Effect of stimulation protocol section below) the characteristics of the input.

To determine if the different activity changes observed in response to patterned stimulation correlate with neuronal identity, we looked at the responses of identified pyloric vs gastric neurons in the presence of 20 mM TEA. Of a total of 8 pyloric neurons and 3 gastric neurons, all expressed oscillatory activity. We measured oscillation amplitude (32.1 ± 19.2 mV), cycle period (590 ± 450 msec) and duty cycle (0.71 ± 0.28) and measured stimulus-induced changes in these three measures. We found no statistically significant difference in the changes induced by stimulation between pyloric and gastric cells in any of these three measures (P = 0.411, 2-Way RM ANOVA).

Conductance changes induced by patterned stimulation

In neurons stimulated with rhythmic hyperpolarizing pulses we observed a statistically significant decrease in high threshold K+ conductance, gK, recorded at +10mV in normal saline of approximately 45% (0.58 ± 0.07 μS before stimulation, 0.31 ± 0.04 μS after stimulation, P = 0.005, n = 6, paired t-Student test; Fig. 4F, left). In those neurons in which the activity was not modified no change in gK was observed (0.65 ± 0.17 μS before stimulation; 0.68 ± 0.15 μS after stimulation, P = 0.375, n = 6, paired t-Student test; Fig. 4F, right). These results are consistent with an increased excitability of those neurons sensitive to prolonged stimulation as would be expected for neurons that switched activity from a silent or tonic pattern to an oscillatory pattern (Fig. 4A, C). These results appear to be inconsistent with the change in activity from oscillatory to tonic firing that we saw in a small subset of stimulated neurons (12%, Fig, 4D), which under our definition would be considered due to a reduction of excitability (see dynamic clamp results below and Discussion).

STG neurons in situ (cf Golowasch and Marder 1992; Graubard and Hartline 1991) and in culture (Turrigiano et al. 1995) express large outward currents dominated by a TEA sensitive IK(Ca). In contrast with the complete block of IK(Ca) by TEA in situ (Golowasch and Marder 1992; Graubard and Hartline 1991), TEA has been reported to incompletely block IK(Ca) in cultured STG neurons (Hurley and Graubard 1998). In our hands, 20mM TEA eliminates 84 ± 6% (n = 6) of the total high-threshold outward current in cultured STG neurons. IK(Ca) constitutes approximately 20% of the outward current recorded in 20 mM TEA (defined as the current additionally blocked by 200 μM Cd++; the high-threshold current remaining in the presence of Cd++ corresponds to a delayed rectifier current, IKd). In the presence of 20 mM TEA we observed that prolonged patterned stimulation induced a significant reduction of the outward current for all voltages ≥ –10 mV (P = 0.004, n = 6, Two-Way RM ANOVA, Fig. 6A) but with no apparent effect on the voltage-dependence of activation (Fig. 6A; V1/2 before stimulation = –9.4 ± 17.6 mV, V1/2 after stimulation = –10.4 ± 14.7 mV, P = 0.900, n = 6, paired t-Student test). We estimated the maximum conductance from the current averages measured at 0 mV. Before stimulation the estimated maximum conductance was 0.12 ± 0.06 μS, which decreased by a statistically significant 22% to 0.09 ± 0.06 μS (P = 0.022, n = 7, paired t-Student test). In the absence of known specific K+ current inhibitors these data suggest that most of the spontaneous and stimulation-induced changes of IK could be attributed to IK(Ca) since 87% of the total IK corresponds to IK(Ca), as defined by K+ current blockade with Cd++ (Golowasch and Marder 1992), and 13% to a delayed rectifier K+ current. Thus, the 45% stimulation-induced reduction in the total K+ current that we observe cannot be accounted for by effects on the delayed rectifier only. Furthermore, because we observe a stimulation-induced reduction of 22% of the remaining total outward current in the presence of 20mM TEA, and 20% of that current can be further blocked with Cd++ (and thus corresponds to IK(Ca)), we conclude that an effect of rhythmic stimulation exclusively on IK(Ca) is in principle sufficient to account for all our observations of activity-dependent effects on outward currents.

We performed similar measurements on 6 identified pyloric neurons and 5 identified gastric neurons in order to confirm if any of these changes are neuron type-specific. We compared the high-threshold K+ current I-V relationship difference (after normalization) before and after 0.33 hyperpolarizing stimulation for pyloric and gastric neurons separately as was done with unidentified neurons before (see Fig. 6A, bottom panel). A Two-Way RM ANOVA reveals no statistical significant difference in the effect of rhythmic stimulation between identified pyloric and gastric neurons (P = 0.546).

We isolated ICa as described in Methods (Fig. 6B). Hyperpolarizing stimulation for as little as 15 minutes induced a marked increase in ICa (Fig. 6B, top panel). Figure 6B also shows the peak current-voltage relationship before (Control, black symbols) and after rhythmic stimulation of STG neurons (After Stim, grey symbols). A statistically significant increase for all voltages ≥ –10 mV is observed (P = 0.011, n = 15, Two-way RM ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis), with the peak conductance measured at +10 mV growing 2.5 fold from 0.014 ± 0.031 μS to 0.036 ± 0.031 μS. (P = 0.046, n = 7, paired t-Student test). We observed no significant effect of stimulation on the voltage dependence of activation of this current (Fig. 6B; the half maximal activation voltage, V1/2 before stimulation = –2.5 ± 10.0 mV, V1/2 after stimulation = –5.5 ± 30.2 mV, P = 0.099, n = 7, paired t-Student test).

As can be seen in the current traces in Fig. 6B (top panel), ICa measurements are slightly contaminated with IK, although the very early measurements of ICa minimized this contamination. In 20 mM TEA ~20% of that K+ current corresponds to IK(Ca), whose conductance we argue is reduced by rhythmic hyperpolarizing stimulation. In order to eliminate this possibility we first tested the effect of 100 mM TEA on IK. We found that the cells were not adversely affected by this extremely high concentration. We also found that adding 200 μM Cd++ does not produce an additional block of IK (not shown). We take this as evidence that 100 mM TEA completely eliminates IK(Ca), leaving intact only part of the delayed rectifier conductance. As a further way to isolate ICa, we measured the Ca++ tail currents (in the presence of 100 mM TEA + 0.1 μM TTX) at –80 mV after activating ICa with 800 msec long depolarizing pulses in the range –60 to +30 mV (Fig. 6C). The K+ equilibrium potential in these neurons is close to –80 mV. Thus these tail currents should be almost entirely free of contaminating K+ currents. Under these conditions we observe a highly significant increase in ICa at all voltages above –20 mV (P = 0.001, n = 5, Two-way RM ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis). At +20 mV we calculate a highly significant Ca++ conductance increase from 0.040 ± 0.047 μS to 0.061 ± 0.056 μS (P < 0.001, n = 10, paired t-Student test).

In contrast with the effect on IK and ICa, the leak conductance showed no change in conductance in these experiments (0.004 ± 0.003 μS before stimulation, and 0.005 ± 0.002 μS after stimulation, P = 0.712, n = 7, paired t-Student test). Leak conductance was determined in these experiments from the current changes elicited in response to the voltages steps from –40 to –50 (or –60) mV. Additionally, the transient IA current (measured in TEA to minimize other K+ currents and with IK and leak current subtracted) is completely unaffected by patterned stimulation in cultured crab STG neurons (Fig. 6D, P = 0.918, Two-way RM ANOVA over the activation range: –40 to +30 mV). Specifically, the average peak conductance gA, V1/2 and s values measured at +10 mV were gA = 0.32 ± 0.11 μS, V1/2 = –24.9 ± 5.6 mV and s = 9.5 ± 3.5 mV before stimulation, and gA = 0.33 ± 0.13 μS, V1/2 = –23.5 ± 5.3 mV and s = 7.9 ± 2.4 mV after stimulation were likewise not statistically significantly affected by stimulation (P =0.938, n = 7, Two-Way RM ANOVA).

The hyperpolarization-activated current's voltage-dependence (i.e. steady state activation curve) is strongly shifted to more negative values than those observed in cultured lobster STG neurons or crab's LP neuron in situ (Turrigiano et al. 1995, Golowasch, 1992 #11) before (V1/2 = –104.1 ± 4.4 mV, slope factor s = 8.3 ± 3.7 mV, n = 7, and neither of these values, nor the maximum conductance were affected by patterned stimulation. The maximum conductance measured at –120 mV was 0.015 ± 0.007 μS before stimulation, and 0.018 ± 0.010 μS after stimulation (P = 0.140, n = 8, paired t-Student test).

Role of calcium influx in activity-dependent regulation of conductances

The conductance changes reported above most likely occurred in response to the experimentally imposed activity pattern and were not due to effects of the electrode-filling solutions (K-citrate, K2SO4 or TEA·Cl + CsCl) or of different bathing solutions (TEA, TTX, Cs+), and occurred in the absence of any known growth factors or neuromodulators. For activity to be responsible for these changes, neurons need to be able to detect changes in their own patterns of activity. A plausible candidate for such a gauge of activity is intracellular Ca++ (Bito et al. 1997; De Koninck and Schulman 1998; Liu et al. 1998; Schulman et al. 1995). Indeed, in our neurons the only conditions that block the effects of rhythmic stimulation are those that interfere with Ca++ influx (neither the K+ current blocker TEA nor the Na+ current blocker TTX do). Figure 7A shows peak ICa recorded in 100 mM TEA and Figure 7C shows IK recorded in 20 mM TEA, before (Control) and after 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation in the presence of 200 μM Cd++ (Stim in Cd++). Cd++ is known to block the high-threshold ICa in STG neurons (Golowasch and Marder 1992; Graubard and Hartline 1991; Turrigiano et al. 1995) and we reasoned that stimulation in the presence of a blocker of Ca++ influx should eliminate the effect of stimulation on IK and ICa. Indeed we observed that 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation in the presence of Cd++ eliminates the enhancing effect on ICa (P = 0.308, n = 5) and the depressing effect on IK (P = 0.618, n = 5, Two way RM ANOVA). The inset in Fig. 7A (Re-Stim in Ca++) also shows a strong enhancement of ICa recorded in one (of two) cells in which we succeeded to wash out Cd++ and further stimulate with hyperpolarizing pulses for approximately 30 additional minutes with Ca++ influx restored. Furthermore, Figure 7B shows an inward current that shows virtually no inactivation when Ca++ is replaced with Ba++ in the extracellular solution. With Ca++ influx thus minimized, no change in the amplitude of the inward current now carried by Ba++ (Control) was observed in response to prolonged patterned stimulation (After Stim, Fig. 7B). No significant changes were recorded over the voltage-dependent activation range (–30 to +30mV) of this current (P = 0.300, n = 5, Two-way RM ANOVA).

Effect of stimulation protocol

The results shown thus far suggest that rhythmic neuronal activity plays an important role in determining both activity and ionic conductance changes. The stimulation protocol used thus far has been hyperpolarizing 1 second long pulses every 3 seconds (Methods). Does the effect of rhythmic stimulation on activity and ionic currents depend on the properties of the stimulus? We tested this by measuring the high-threshold K+ current, IK (Fig. 8). Cells were hyperpolarized rhythmically a slower rate (8 second pulses every 9 seconds, i.e. 0.11 Hz Hype, Fig. 8A) and at a slightly faster rate (1 sec pulses every 2 sec, i.e. 0.5Hz, Fig. 8B) than the standard stimulation frequency of 0.33 Hz. Because our several controls on identified pyloric and gastric neurons have shown no correlation of any of the measurements of activity or conductance with neuronal cell type, we performed this experiment on unidentified neurons. Fig. 8A shows the effects on IK of applied 0.11 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation for approximately 25 minutes, followed by 35-45 minutes of standard 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation. Compared to the results shown in Fig. 6A, where 0.33 Hz stimulation induces a clear and statistically significant decrease in amplitude of IK at all voltages above –40mV, 0.11 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation instead induces a statistically significant increase of the current amplitude at voltages ≥ 0 mV (P = 0.002, n = 6, Two-Way RM ANOVA; Fig. 8A, solid grey triangles). When 0.11 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation was followed by 0.33 Hz stimulation (Fig. 8A, open grey squares), we observed a statistically significant decrease of the current amplitude at voltages ≥ –10 mV (Control vs 0.33 Hz stim: P = 0.011; 0.11Hz Hype vs 0.33 Hz hype: P < 0.001, n = 6, Two-Way RM ANOVA) comparable to our previous observations (Fig. 6A). To establish if this is a specific effect on the high-threshold K+ current, we measured the effects of the same stimulation sequence on IA, which we have already shown to be unresponsive to 0.33 Hz stimulation (Fig. 6D). No statistical significant effect of either stimulus pattern was observed on IA (P = 0.869, n = 5, Two-Way RM ANOVA). On the other hand, only a slightly higher hyperpolarizing stimulation frequency (0.5 Hz) compared to the standard 0.33 Hz frequency, results in no significant change in amplitude of IK at any voltage (Fig. 8B, P = 0.779, n = 5). IA was also not affected by 0.5 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation (P = 0.254, n = 5, Two way RM ANOVA). The fact that hyperpolarizing stimulation within a voltage range in which no Ca++ current has been directly detected in STG neurons in culture or in situ rises the question of what the path may be for cytoplasmic Ca++ increase. Because ICa is strong at –10 mV we stimulated STG neurons with depolarizing pulses from –40 to –10 mV in voltage clamp to ensure Ca++ influx through a path known to be present in these cells. Fig. 8C shows the results of such an experiment. Depolarizing stimulation had no discernible effect on IK (P = 0.526, n = 5, Two way RM ANOVA). To demonstrate that this result is specific to depolarizing stimulation, in two instances we were able to maintain the cells impaled long enough to stimulate them with 0.33 Hz hyperpolarizing pulses for additional 40 minutes. The inset of Fig. 8C shows that the characteristic downregulating effect of hyperpolarizing stimulation could be clearly elicited in this neuron. Finally, depolarizing stimulation also had no significant effect on IA (P = 0.898, n = 5, Two way RM ANOVA).

Additionally, as would be expected from the effects of 0.11 Hz hyperpolarizing stimulation on IK mentioned above, 0.11 Hz stimulation had a statistically significant effect on the amplitude of the slow oscillations recorded in the 6 neurons that we stimulated (50.2 ± 14.0 mV before stimulation, 31.7 ± 17.8 mV after stimulation; P = 0.016, t-Student test). We could not measure either burst duration or cycle period because 0.11 Hz stimulation had the additional effect of drastically reducing the number of oscillations measured with a current pulse of any levels, in most cases to only one or zero oscillations. These results, although not quantifiable, are consistent with an enhancement of a high-threshold K+ current.

Dynamic clamp experiments

The effects of prolonged stimulation on voltage-dependent currents and neuronal activity only partially reversed during the time we could maintain the recordings (2-4 hours). To verify if the spontaneous and stimulation-induced conductance changes (IK decrease and ICa increase) are indeed sufficient to account for the observed alterations in neuronal patterns of activity, we introduced negative or positive outward and inward conductances with dynamic clamp. We fitted with Hodgkin & Huxley-type equations the high threshold K+ current difference, and separately the Ca++ current difference of neurons sensitive to patterned stimulation in normal saline. For these fits we chose neurons that responded to patterned stimulation with high threshold K+ and Ca++ current changes close to the population average. The best fit to the K+ current could be obtained with two conductance components, one transient (gKtr) and one sustained (gKst), while the Ca++ current could be fitted well with a single component (gCa). The conductance parameters thus obtained and used for our dynamic clamp experiments are given in Table 1. Because the voltage dependence of these currents does not appear to be affected by patterned stimulation we modified only the maximum conductances to mimic the changes observed on these two currents. Fig. 9A shows the results of one such experiment on naïve unstimulated neurons recorded in normal saline. Activity was elicited by small depolarizing current injections. Conductance values indicated above the arrows correspond to the maximum conductance values of each dynamic clamp current. Many different patterns of activity could be produced by relatively small changes of the maximum conductance values, which depended on the particular neuron recorded (Fig. 9A). However, we could repeatedly induce oscillatory activity by reducing the outward currents (negative conductance) and/or increasing the inward current (positive conductance, Fig. 9A, top and middle panels). It was relatively easy to also find combinations of maximum conductance values within the range of the spontaneous or stimulation induced conductance changes described before that could produce tonic firing in a neuron that was originally oscillatory (Fig. 9A, bottom panel). Figure 9B shows in more detail that some properties induced by prolonged rhythmic stimulation can not only be mimicked by adding gCa and subtracting gK but also reversed by subtracting gCa and adding gK after they were induced by stimulation. Before rhythmic stimulation was started the neuron shown in Fig. 9B (top left) was bathed in 20 mM TEA to induce slow, large amplitude oscillations. Adding gCa and subtracting gK with dynamic clamp increased the amplitude and slightly decreased the frequency of oscillations (Fig. 9B, top-right). A similar but more pronounced effect was later observed after rhythmically stimulating the neuron for 20 minutes with dynamic clamp discontinued. Finally, the enhanced oscillation amplitude and reduced oscillation frequency induced by rhythmic stimulation was partially reversed by subtracting gCa and adding gK with identical levels as used immediately before to induce the changes with dynamic clamp (Fig. 9B, bottom right).

Discussion

Long-term regulation of neuronal excitability and intrinsic properties can play a key role in maintaining activity patterns of single neurons and networks within stable and operational ranges in response to a variety of perturbations (Davis and Bezprozvanny 2001; Desai et al. 1999; Franklin et al. 1992; Galante et al. 2001; Hong and Lnenicka 1995; Li et al. 1996; Linsdell and Moody 1994; Luther et al. 2003; Turrigiano et al. 1994; Turrigiano and Nelson 2004). Here we have used adult cultured STG neurons of the crab C. borealis to identify mechanisms that underlie the recovery and stabilization of rhythmic activity after dissociation. We find that down-regulation of the high-threshold K+ current, IK, and up-regulation of a Ca++ current, ICa, is called into play during the spontaneous regulation of activity after dissociation. Prolonged 0.33 Hz rhythmic stimulation with hyperpolarizing pulses induces similar changes in the same two currents. However, low frequency hyperpolarization (0.11 Hz) had the opposite effect on IK and slightly higher frequency (0.5 Hz) had no effect at all (Fig. 8A) indicating that crab STG neurons are sensitive to the temporal properties of the stimulus as previously suggested by Turrigiano and collaborators. As a consequence STG neurons may be tuned to the oscillating frequencies of the network each of these neurons are normally part of (Turrigiano et al. 1994). From this it would be expected that neurons belonging to networks whose natural frequency is not the same would respond differently to the same pattern of stimulation or, alternatively, develop a different frequency of oscillation in culture. Surprisingly, however, we found that identified neurons belonging to both the pyloric and the gastric mill networks, which typically oscillate in situ at 5-10 fold different frequencies, developed oscillations in culture with indistinguishable frequencies. We further found that gastric and pyloric neurons cannot be distinguished during the culture period studied (up to 10 days) on the basis of their activity changes or the ionic mechanism involved in their responses to stimulation. Preliminary ongoing experiments indicate that in culture pyloric neurons appear to retain the properties developed during the first week in culture while gastric neurons appear to slowly differentiate from a pyloric neuron phenotype in a time scale of weeks via an unknown mechanism.

We find that excitability cannot only be reduced by patterned stimulation as has previously been reported (Turrigiano et al. 1994), but can also be heightened with the same type of stimulation, an excitability increase being 3 times more likely in crab neurons than an excitability reduction. The apparent difference in response to rhythmic stimulation of lobster neurons, which in the study of Turrigiano and collaborators were not shown to be able to enhance their excitability, may stem from the fact that in their study only bursting neurons were selected for stimulation and analysis (Turrigiano et al. 1994). We find that oscillating neurons can only respond to stimulation by switching to either tonic firing (similar to lobster neuron responses), or not at all. In their study, Turrigiano et al. (1994) apparently did not analyze bursting neurons that did not respond to stimulation.

Spontaneous activity changes

The progressive decrease in the proportion of silent STG neurons in primary culture and the increase in the proportion of neurons expressing tonic and, later, mostly oscillatory activity suggests a predetermined tendency to oscillate and the existence of homeostatic mechanisms that allow neurons to restore their oscillatory activity after it is lost (see also Turrigiano et al. 1995). Pyloric network neurons can behave as oscillators when acutely isolated from the network but, with the exception of the single pacemaker AB neuron, all oscillate irregularly (Bal et al. 1988). These oscillations occur only when neuromodulatory inputs to the STG are intact (Nusbaum and Beenhakker 2002). In the absence of these neuromodulatory inputs all STG neurons, including the AB neuron, lose the ability to oscillate (Bal et al. 1988). Our results and those of Turrigiano et al (1995) indicate that most (if not all) STG neurons in time evolve robust oscillatory activity when isolated from network and from neuromodulatory influences.

In our culture conditions neuromodulators are completely absent and the recovery of rhythmic activity of isolated STG neurons is reminiscent of the recovery of rhythmic activity in the intact pyloric network after the permanent removal of neuromodulatory inputs (Luther et al. 2003; Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 1998). In lobsters, this latter recovery is accompanied by the development of oscillatory properties by some identified pyloric network neurons within a few days (Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 2002). Thus, the acquisition of oscillatory properties we and Turrigiano et al (1995) have observed in isolated STG neurons in culture provides a plausible mechanism for the recovery of rhythmic activity in the network. It is interesting, however, that the conductances that have been shown to be spontaneously regulated in the intact network after decentralization are not the same as those regulated in dissociated neurons in culture (Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 2002), see Ionic mechanism of activity regulation).

Two hypotheses (as of yet not tested) may explain the suppression of endogenous oscillatory properties in neurons within the intact STG. One, oscillatory properties may be suppressed by neuromodulators exerting trophic effects (Le Feuvre et al. 1999; Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 2000). Two, activity itself may regulate the expression of endogenous oscillatory properties (Golowasch et al. 1999b; Turrigiano et al. 1994). Our results are consistent with both hypotheses. In the intact network neuromodulators may somehow suppress the expression of endogenous oscillatory properties in most neurons. Once this input is eliminated (by cell dissociation or by removal of neuromodulatory inputs in situ) constraints on the expression of these properties are removed and oscillatory activity can be expressed by up- and down-regulation of ionic currents such as those characterized in this work and those characterized previously by Turrigiano et al (1995). Spontaneous emergence of oscillatory properties in culture conditions may be genetically determined as suggested by the spontaneous changes in activity and ionic currents described in this study and by Turrigiano et al (1995). However, this possibility does not exclude the possibility that activity itself may also regulate neuronal electrical properties (Desai et al. 1999; Golowasch et al. 1999a; Liu et al. 1998).

Stimulation-dependent effects on activity

Our results show that isolated STG neurons are sensitive to prolonged rhythmic stimulation. Neurons displaying either silent or tonic firing activity can be induced to oscillate, while neurons that show oscillatory activity remain able to revert to tonic firing (but not to the silent) states (Fig. 4).