Abstract

LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs) are emerging as key circuit components in regulating microbial stress responses and are implicated in modulating oxidative stress in the human opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The oxidative stress response encapsulates several strategies to overcome the deleterious effects of reactive oxygen species. However, many of the regulatory components and associated molecular mechanisms underpinning this key adaptive response remain to be characterised. Comparative analysis of publically available transcriptomic datasets led to the identification of a novel LTTR, PA2206, whose expression was altered in response to a range of host signals in addition to oxidative stress. PA2206 was found to be required for tolerance to H2O2 in vitro and lethality in vivo in the Zebrafish embryo model of infection. Transcriptomic analysis in the presence of H2O2 showed that PA2206 altered the expression of 58 genes, including a large repertoire of oxidative stress and iron responsive genes, independent of the master regulator of oxidative stress, OxyR. Contrary to the classic mechanism of LysR regulation, PA2206 did not autoregulate its own expression and did not influence expression of adjacent or divergently transcribed genes. The PA2214-15 operon was identified as a direct target of PA2206 with truncated promoter fragments revealing binding to the 5′-ATTGCCTGGGGTTAT-3′ LysR box adjacent to the predicted −35 region. PA2206 also interacted with the pvdS promoter suggesting a global dimension to the PA2206 regulon, and suggests PA2206 is an important regulatory component of P. aeruginosa adaptation during oxidative stress.

Introduction

Bacteria have evolved diverse integrated regulatory networks which are essential for their survival and persistence in a vast array of ecological niches. An efficient response to changing environmental conditions requires the coordination of signal perception and transduction, transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, as well as post-translational events. By far the largest known family of transcriptional regulators in prokaryotes, LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs), are emerging as key coordinators of microbial gene expression. LTTRs are ubiquitous among bacteria with orthologues also found in archaea and eukaryotic organisms [1]. These signal responsive proteins represent the primary mechanism of regulation of catabolic systems in bacteria while they have also been shown to influence key adaptive and virulence phenotypes such as biofilm formation, motility, signalling, secondary metabolite production, and oxidative stress caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [1], [2].

Organisms are exposed to ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the superoxide anion, during the course of normal aerobic metabolism or following exposure to radical-generating compounds, including redox-cycling drugs. ROS cause wide-ranging damage to macromolecules, which can eventually lead to cell death. To protect themselves against this damage, cells have evolved effective defence mechanisms, including anti-oxidant enzymes and free radical scavengers. OxyR, an LTTR that is universally encoded among Gram negative bacteria, is considered the master regulator of the oxidative stress response. In Escherichia coli, OxyR works in concert with the small RNA oxyS to coordinate expression of catalase and peroxidase genes [3]. More recently, several other LTTRs have been shown to play a role in the oxidative stress response, including Hrg in Salmonella enterica [4], HypR in Enterococcus faecalis [5], CztR in Caulobacter crescentus [6] and HcaR in E. coli [7]. However, with the exception of OxyR, the role of LTTRs during oxidative stress remains largely uncharacterised in many bacteria. This is particularly true for the important nosocomial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa in which LTTRs account for more than 2% of the total gene content [8].

In addition to being a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections in immunocompromised individuals, P. aeruginosa is also the primary cause of chronic lung infections in patients suffering from cystic fibrosis [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. OxyR has been shown to modulate the expression of several key oxidative stress response genes including katA, katB, ahpB and ahpCF in P. aeruginosa [14], [15]. Recently, the OxyR regulon in P. aeruginosa was defined through Co-IP analysis and was shown to include genes involved in iron homeostasis, quorum sensing, protein synthesis, and oxidative phosphorylation [15]. Wei and colleagues proposed a multilayered response to oxidative stress which includes increased expression of antioxidants to detoxify ROS, inhibition of primary metabolism and oxidative respiration to reduce the production of ROS, and modulation of iron uptake systems to minimise the Fenton reaction [15]. This requires a complex cellular response, the control of which is likely to encompass multiple regulatory components. However, apart from OxyR, the role of LTTR proteins in the P. aeruginosa oxidative stress response has not been investigated.

In this study, we identified PA2206 as a novel LTTR transcriptionally influenced by both oxidative stress and host signals, independent of the master regulator of oxidative stress, OxyR. PA2206 was found to be required for an effective oxidative stress response as well as lethality in a zebrafish model of infection. This novel non-classical LTTR was found to have a significant influence on the expression of oxidative stress responsive genes, while the PA2214-2215 and pvdS promoters were identified as direct targets. PA2206 was shown to interact specifically with the 5′-ATTGCCTGGGGTTAT-3′ LysR box adjacent to the predicted −35 region of the PA2214-15 promoter. The requirement of PA2206 for tolerance to oxidative stress and zebrafish embryo lethality, independent of OxyR, implies a novel route for the management of oxidative stress in P. aeruginosa, and a role for PA2206 during the host-microbial interaction.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, media and growth conditions

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All cultures of P. aeruginosa strain mPAO1 and associated mutants were routinely grown in Luria Bertani [16] or M9 minimal media [supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) sodium citrate, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.05 mM FeCl3] at 37°C [17]. Bacterial cultures were grown in Casamino Acid (CAA) medium supplemented with 100 µM FeCl3, for the proteomic analysis [18]. Tetracycline-resistant transposon insertion mutants (Table 1) were obtained from the University of Washington Genome Centre mutant library [19]. Transposon insertion, location, and orientation were confirmed for all mutants. E. coli strains were routinely grown in LB media at 37°C. Where appropriate, antibiotics were added to growth media at the following concentrations: tetracycline, 60 µg ml−1, and gentamicin, 20 µg ml−1, for P. aeruginosa; and ampicillin, 50 µg ml−1, and gentamicin, 20 µg ml−1, for E. coli.

Table 1. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains | Description | Source/Reference |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| mPAO1 | Wild-type | [19] |

| mPA2206− | mPA2206::Tn5 TcR | [19] |

| mPA2206C | PA2206− containing pBR-PA2206P | This study |

| mPA2215 | mPA2206::Tn5 TcR | [19] |

| oxyR− | PAO1 oxyR− | [14] |

| E. coli | ||

| TOP 10 | F– mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu) 7697 galU galK rpsL (StrR) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | F– Φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK−, mK+) phoA supE44 λ– thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| BL21-CodonPlus (DE3) | E. coli B F- ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) dcm+ Tetr E. coli gal λ (DE3) endA Hte [argU ileY leuW Camr] | Merck |

| EcpBR | E. coli DH5α containing pBBR1MCS5 plasmid. | This study |

| EcpBR-2 | E. coli DH5α containing pBR-2206. | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO TA | Cloning vector, Apr, KmR | Invitrogen |

| pMP190 | IncQ origin, low-copy-number lacZ fusion vector; Cmr Strr | [27] |

| pMP-p2214 | pMP190-derived PA2214 promoter-lacZ fusion plasmid | This study |

| pMP-p2216 | pMP190-derived PA2216 promoter-lacZ fusion plasmid | This study |

| pMP-p2206 | pMP190-derived PA2206 promoter-lacZ fusion plasmid | This study |

| pET28a | T7 promoter-driven His-tag protein expression vector, Kmr | Novagen |

| pBBR1MCS5 | Broad host range complementation plasmid, lacZ alpha, Gmr | [26] |

| pBR-2206P | pBBR1MCS5 containing PAO1 PA2206 with native promoter downstream of lac promoter | This study |

| pBR-2206 | pBBR1MCS5 containing PAO1 PA2206 CDS downstream of lac promoter | This study |

Assay of survival under conditions of oxidative stress

Growth assays were performed with 20 mM H2O2 or 40 mM menadione added to exponentially growing cells. Briefly, overnight cultures were transferred into fresh media at a starting OD600 nm of 0.1, and were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 3 hrs. Subsequently, at approximately OD600 nm 0.6, H2O2 or menadione was added and growth monitored hourly. Survival assays were performed in the presence of 100 mM H2O2 as this concentration has previously been chosen for P. aeruginosa and other species [20], [21]. Overnight cultures were washed in Ringer's solution (¼-strength) and resuspended to an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm. Bacterial suspensions (5 ml) were exposed to 100 mM H2O2 at 37°C with agitation (150 rpm). Viable counts were determined on LB agar with antibiotic selection where appropriate before and after 1 hour of exposure, and expressed as percentage surviving cells as described by Heeb and colleagues [22]. Zonal inhibition assays were performed on M9 plates supplemented with glucose (2% w/v). An overnight PAO1 culture was spread on the agar plate using a sterile swab and air dried in a laminar flow hood for 30 mins. Subsequently, filter paper disks (approx 7 mm) were placed in the centre of the plate and saturated with 10 µl of a 30% (w/w) solution of H2O2 (Sigma) corresponding to an 8.8 M concentration. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and the zone of inhibition measured at 16 hrs.

Zebrafish infection assay

Zebrafish embryos were derived from adults of the Zebrafish AB line (Danio rerio) which were kept at 28°C in a 14-h/10-h light/dark cycle in our breeding facility. Zebrafish embryos were staged at 26 hours post fertilization according to previously described developmental criteria [23]. Embryos were manually dechorionated and subsequently anaesthetized in a 0.015% aqueous solution of ethyl-3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate salt. P. aeruginosa cells from an overnight culture in LB broth were washed twice in phosphate buffer saline and diluted in phenol red phosphate buffer saline in order to visually monitor injection under a stereo-microscope. Bacterial cells were then micro-injected (1–2 nl) into the blood island of the Zebrafish embryos. The inoculum size was determined by injecting in triplicate in phosphate buffer saline followed by plating on LB agar plates. Approximately 300 colony forming units were injected into 10 embryos per group. Injected Zebrafish embryos were returned to egg water, incubated at 30°C, and monitored for mortality on a daily basis. Data represents three independent biological replicates. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare survival rates of zebrafish infected with wild-type and PA2206 −. Differences between infected embryos, compared using a log-rank test in MedCalc®, were considered significant ≤0.05. All animal experiment protocols were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee, University College Cork.

Bioinformatics and comparative genomic analysis

Genome sequences were obtained from the www.pseudomonas.com resource [24] and compared using the ARTEMIS Comparison Tool on the www.webact.org site [25]. Promoter predictions were performed using BProm software on the http://linux1.softberry.com site.

To screen the PAO1 genome for the LysR consensus sequences identified proximal to the PA2214 predicted −35 upstream region, nucleotide sequences from positions −300 to −1 relative to the origin of translation of all coding sequences (CDS) were parsed from the Genbank annotated genome sequence file (version AE004091.2) of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and stored locally in FASTA format using a script in Perl. CDSs matching TTN9TA, where N is any nucleotide, in the 300 bp upstream of the origin of translations were identified using Bioperl [16]. Subsequently, sequences were analysed using MEME motif search software to construct a PA2206 LysR consensus motif. This analysis was restricted to sequences which had a statistical significance (p-value) lower than 1e−04.

Complementation in trans of mutant strains

Oligonucleotide primers PA2206CCF and PA2206CCR (Table S1) were designed to amplify the PA2206 gene and promoter region based on the PAO1 genome sequence (GenBank accession number NC002516). The DNA fragment was amplified from PAO1 genomic DNA using Platinum High Fidelity Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, UK) and subsequently cloned as a HindIII and XbaI fragment into HindIII-XbaI sites of pBBR1MCS-5 generating pBR1-PA2206 C [26]. Similarly, primer Hin2206F was designed at the PA2206 translational start site to create construct (pBR1-2) with primer Xb2206R (Table S1). Chemical transformation into competent E. coli DH5α cells and purification was followed by electroporation into the P. aeruginosa mPAO1 PA2206 Tn5 mutant strain as described by Sambrook and colleagues [17]. Construct fidelity was confirmed by sequencing in both directions.

Promoter-fusion analysis

Promoter regions were amplified from PAO1 genomic DNA by PCR using Platinum High Fidelity Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). The PA2214 promoter region was amplified using PA2214TRF and PA2214TRR primers, while the PA2216 promoter was amplified using PA2216TRF and PA2216TRR (Table S1). The PA2206 promoter was amplified using PA2206TRF and PA2206TRR primers (Table S1). Inserts were digested using XbaI-KpnI and subsequently ligated directly into similarly digested pMP190 [27] plasmid at 16°C overnight followed by transformation into chemically competent DH5α E. coli cells. Promoter orientation was confirmed by PCR using a promoter specific primer and a lacZ primer and the fidelity of all transcriptional fusions was verified by sequencing (GATC). Triparental mating utilising an E. coli strain harbouring the pRK2013 helper plasmid was performed to transfer the fusions into recipient P. aeruginosa strains. The PA2214 promoter fusion was also introduced into E. coli containing pBR1-2 and pBBR1MCS5 vector control. Fusion analysis was performed in M9 media supplemented with glucose (10 mM) with cultures grown at 37°C with shaking.

Microarray analysis

Three independent overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa PA2206− mutant and PA2206C grown in M9 minimal media [supplemented with 1 mM MgsO4 and 2% glucose] with shaking at 37°C, were diluted to an optical density of 0.05 at 600 nm in fresh media. Cells were then grown to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm at which stage they were exposed to 1 mM H2O2 for a ten minute time period. Total RNA was subsequently extracted using the QIAGEN™ RNeasy® Mini RNA extraction kit in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. RNA was treated with Ambion® TURBO™ DNase at 37°C for 1 hour and the RNA pellet was then resuspended in sterile diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water (1 ml of 0.1% DEPC) to a final volume of 25 µl. Isolated RNA was sent to DNAVision (Belgium) for further analysis. RNA quality was checked using a Bioanalyzer Agilent 2100 at DNAVision, and cDNA synthesis, fragmentation and terminal labelling preceded hybridisation on Affymetrix GeneChip P. aeruginosa Genome arrays according to the Affymetrix guidelines. The raw data was normalised using the robust multiarray average (RMA) algorithm [28] and pairwise comparison (t-test, P<0.05) was carried out to generate a list of genes with significantly altered expression between the test strains of greater than 1.5 fold. The p-value was then assessed for each gene by controlling the false discovery rate using the Benjamini Hochberg method [29]. All files have been submitted to the GEO database (Ref No: GSE23367) compliant with MIAME.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

cDNA was synthesised using AMV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega), RNasin (100 U/µl) (Promega), random primers (0.5 µg/µl) (Promega) and 10 mM dNTPs (Promega). Specific RT-PCR primers were designed for each gene based on the PAO1 genome sequence (Table S1). Standards were generated by PCR and quantitative real-time PCR analysis of expression was carried out using the Quantifast SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN). Quantitative real time-PCR signals were normalised to the constitutively expressed housekeeping gene proC [30], whose expression was shown to be unaltered under the conditions used to generate the transcriptomic profile.

Microarray data were validated by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from three independent experiments as above. For further analysis of gene expression under different oxidative stress conditions, overnight cultures of the wild-type and mutant strains were inoculated into M9 minimal media supplemented with glucose (2% w/v) at an initial OD600 nm of 0.05. The cells were grown to an OD600 nm of 0.4 and the cultures were subsequently divided and exposed to 1 mM and/or 5 mM concentrations of H2O2 for 5 and 10 minute time periods. Untreated cells were harvested as a control against which to compare gene expression. All assays were carried out in triplicate, and the mean and standard error were calculated.

PA2206-HisTag protein purification and quantification

The PA2206 gene from P. aeruginosa PAO1 was amplified using gene-specific primers 2206HisF and 2206HisNR (Table S1) and cloned into the pET28a inducible expression plasmid (Invitrogen) using the EcoRI-HindIII restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs). Constructs were transformed into E. coli BL21 Codon Plus (DE3) cells giving rise to PA2206 fused to an N-terminal His6 tag. Overnight LB cultures were transferred into fresh media supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and were grown at 30°C to an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm at which time IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. The cultures were grown for a further 4 hrs and cells were harvested at 4°C following centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 mins. Supernatants were removed and cells were stored overnight a −80°C to enhance lysis. Cell pellets were resuspended in Cell Lytic™ B, lysosyme, benzonase, and protease inhibitors (all Sigma-Aldrich), and subsequently incubated at room temperature for 15 mins with shaking (100 rpm). Following centrifugation at 10,000 rpm at 4°C, the clarified supernatant was purified on a Poly-Prep chromatography column (Bio-Rad) containing His Select nickel affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) and eluted using increasing concentrations of imidazole (10–500 mM). Fractions were analysed on a 10% (w/v) SDS PAGE (10%) gels (Fig. S1), and the concentration of purified PA2206-His6 protein was determined by Bradford assay as described before [31].

Electrophoretic mobility shift analysis (EMSA)

Target promoter DNA was amplified using InfraRed end-labelled promoter-specific oligonucleotides (Table S1). Promoter fragments were purified using the QIAGEN gel extraction kit and the InfraRed signal was verified on 6% polyacrylamide gels using the Odyssey Imager (LI-COR Biosciences). Truncated promoter fragments were amplified containing boxes 1 & 2 (PA2214F2 and PA2214 TrR), boxes 3–8 (PA2214TrF and PA2214R), boxes 4–8 (PA2214TrAF and PA2214TrAR), boxes 5–8 (PA2214TrBF and PA2214TrAR), boxes 6–8 (PA2214TrCF and PA2214TrAR), boxes 7–8 (PA2214TrDF and PA2214 TrER) and box 8 (PA2214TrEF and PA2214 TrER), respectively (Table S1). Protein-DNA binding assays containing 15 fmoles of DNA with increasing concentrations of PA2206 protein were performed at room-temperature for 30 mins in Roche 5× binding buffer (Roche, Ireland). After completion of the binding assay, 4 µl of 50% glycerol/orange G buffer was added to the samples (20 µl), which were subsequently analysed on a 6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer.

Results

Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals a non-classical host-responsive LysR-Type Transcriptional Regulator (LTTR)

The oxidative stress response is central to the survival of many microbial pathogens during infection. However, the molecular mechanisms governing this key adaptive phenotype remain largely uncharacterised. Interrogation of the publically available transcriptome datasets revealed a striking correlation between oxidative stress and the induction of genes encoding LTTRs in P. aeruginosa. Expression of 41 out of 121 genes annotated as LTTRs in the PAO1 genome was ≥2-fold altered (39 upregulated) at the transcriptional level in P. aeruginosa in response to oxidative stress induced by H2O2 [32], [33], [34]. However, surprisingly only a limited number of these LTTRs that respond to oxidative stress were also altered in transcriptomic datasets designed to investigate the host interaction [35], [36], [37]. We considered this subset of LTTRs likely to play an important role in P. aeruginosa host-microbial interactions and selected PA2206 on the basis of it being regulated in response to both human (+2.82 fold) and plant (+2.7 fold) signals, in addition to oxidative stress [33], [35], [37]. Annotated as a PcaQ-type LTTR and a unique transcriptional unit, PA2206 was not found to be divergently transcribed with an adjacent gene, in contrast to the classic LysR topology [1]. Furthermore, quantitative RT-PCR and promoter fusion analysis revealed that PA2206 did not influence the expression of adjacently transcribed PA2205 or PA2207-09 (data not shown). Therefore, PA2206 would appear to be one of an emerging class of non-classical LTTRs, and its induction in the presence of a range of host signals suggests an important role during the host-interaction.

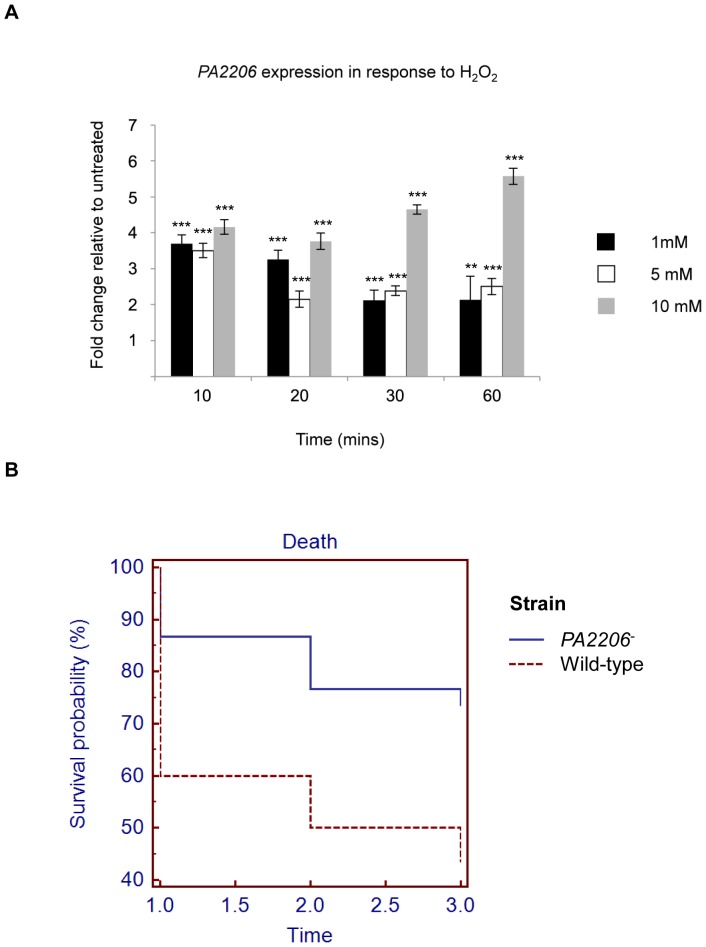

Expression of PA2206 is induced in response to hydrogen peroxide and menadione, independent of OxyR

To confirm the induction of PA2206 in response to oxidative stress, the kinetics of PA2206 expression in the presence of H2O2 was investigated. Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that expression of PA2206 was induced in response to sublethal 1, 5, and 10 mM concentrations of H2O2, following exposure for 10, 20, 30, and 60 minute time periods (Fig. 1A). Expression of PA2206 remained elevated (2–4 fold) in a dose dependent manner for up to an hour after exposure to H2O2 with the greatest induction observed in response to 10 mM H2O2 (Fig. 1A). In order to assess whether this induction was specific for H2O2, expression was investigated in the presence of other oxidative stress inducing compounds. Exposure to the superoxide generator menadione (2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone) resulted in 1.7-fold (±0.15) induction of PA2206 gene expression (Fig. S2), while the organic hydroperoxides cumene hydroperoxide and tert-butyl hydroperoxide did not influence expression of PA2206 (data not shown) suggesting a degree of specificity to the activation of PA2206 in response to oxidative stress.

Figure 1. PA2206 is induced in response to H2O2 and is required for lethality in a zebrafish embryo model of infection.

(A) Bacterial cultures were grown to exponential phase, and aliquots were then either untreated or exposed to 1 mM, 5 mM and 10 mM concentrations of H2O2. PA2206 gene expression was measured as fold change relative to the proC housekeeping gene and subsequently calculated as fold change relative to the untreated sample, following 10, 20, 30, and 60 minute periods of exposure to H2O2. Mean values are represented ± standard error (** p-value≤0.005, *** p-value≤0.001 calculated using one-way ANOVA). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Twenty-six hours Zebrafish embryos were injected with ∼300 colony forming units of either mPAO1 wild-type or PA2206− mutant into their blood island. Embryos were monitored for survival daily. Mean values of three biological experiments (each 10 embryos) are shown. Statistical analysis showed that at 2 and 3 days post infection, mPAO1 wild-type killed significantly more embryos compared to the PA2206− mutant (p-value = 0.0159 using the log-rank test).

To investigate the induction of PA2206 at the transcriptional level, two possibilities were considered; PA2206 may be (1) autoregulatory in the presence of a signal generated during oxidative stress, or (2) under the control of another transcriptional regulator. Although several putative LysR boxes were identified upstream of the PA2206 gene, promoter fusion analysis revealed that mutation or overexpression of PA2206 had no significant influence on its own promoter activity, with comparable Miller Units detected in wild-type, PA2206− and complemented PA2206C strains (Fig. S3). This suggested that PA2206 was not autoregulatory, again in contrast to the classical mechanism of LysR regulation. To investigate whether induction of PA2206 was the result of regulation by OxyR (the master oxidative stress regulator), expression of PA2206 was investigated using qRT-PCR in wild-type and in the oxyR mutant grown in M9 media supplemented with 2% (w/v) glucose. PA2206 was induced to comparable levels in the wild-type and oxyR mutant following exposure to 5 mM or 10 mM H2O2 (Haynes & O'Gara, unpublished data) suggesting that PA2206 expression is induced independently of OxyR during the oxidative stress response.

PA2206 is required for an efficient oxidative stress response and pathogenesis in P. aeruginosa

In order to determine whether the induction of PA2206 in response to H2O2 and menadione correlated with a stress-tolerant phenotype, growth and viability of the wild-type and PA2206 − mutant strains in the presence of exogenous ROS was investigated. Although growth in the untreated samples was comparable for mutant and wild-type strains, growth was significantly reduced in the PA2206− mutant compared to wild-type upon addition of H2O2 (20 mM) or menadione (40 mM) to exponentially growing cells (Fig. S4). In addition, time-kill survival assays provided further evidence that PA2206− mutant was hypersensitive to H2O2 (Table 2). Viable counts for mutant and wild-type strains determined before (time 0) and one hour after (time 1) exposure to H2O2 (a 1 hr sampling time was chosen to assess the steady state response rather than the early and acute response) revealed a significant reduction in survival in the PA2206− mutant compared to the wild-type strain (Table 2). In contrast, wild-type cells were able to survive exposure to this physiologically high concentration (100 mM). Introduction of PA2206 in trans (PA2206C) restored H2O2 tolerance of the mutant to 80% of the wild-type strain. Taken together, these data demonstrated that the PA2206− mutant was significantly more susceptible than the wild-type to exogenous ROS.

Table 2. Susceptibility of wild-type, PA2206− and PA2206 C strains to oxidative stress.

| Strain | Viable counts (cfu/ml) (×106) | % Survival | ||

| Time 0 (hours) | Time 1 (hours) | |||

| Wild-type | 58±2.7 | 70±3.0 | 100 | |

| PA2206− | 58±9.0 | 34±4.2 | 47 | |

| PA2206C | 54±3.5 | 51±4.2 | 79 | |

Mean values are represented ± standard deviation.

To assess the in vivo relevance of the oxidative stress sensitive phenotype of the PA2206− mutant, lethality in the zebrafish embryo model of infection was investigated. Several reports suggest that some transcriptional regulators that influence the oxidative stress response can have a significant impact on pathogenesis or lethality in animal models while others exhibit no influence [38], [39], [40], [41]. Consistent with the stress-susceptible phenotype of PA2206−, the mutant exhibited significantly less killing than the wild-type in the zebrafish embryo model. Killing was reduced to 72% at 2 days post infection (d.p.i.) and 60% (3 d.p.i.) when compared to wild-type (Fig. 1B). Indeed, embryo survival remained constant at 90% in the presence of the mutant strain throughout these experiments. Interestingly, cytotoxicity, invasion and adhesion in epithelial cells was comparable between wild-type and PA2206− (data not shown). Therefore, to better understand the molecular mechanism underpinning the oxidative stress and zebrafish lethality phenotypes of the PA2206− mutant, we undertook global transcriptomic profiling.

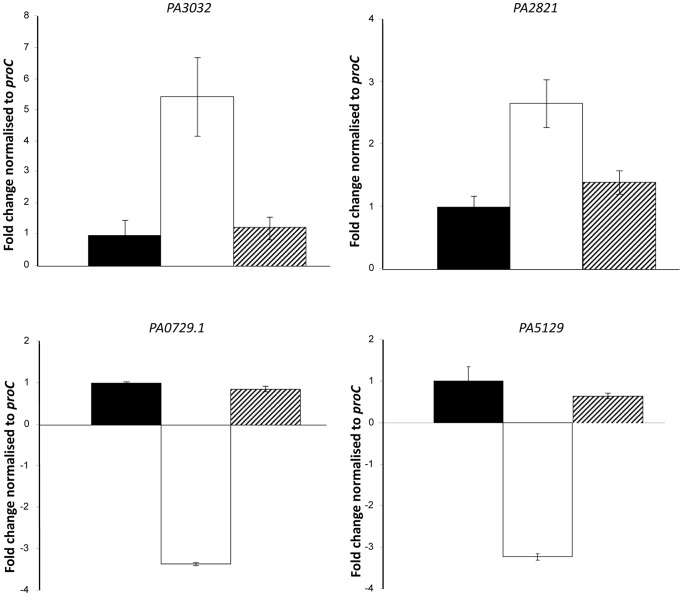

Transcriptomic analysis reveals a global profile for PA2206

In order to uncover the extent of the PA2206 transcriptional regulon during oxidative stress, gene expression profiles were compared between isogenic PA2206 C and PA2206 − in response to a sub-lethal 1 mM concentration of H2O2. This sub lethal concentration was chosen as it most accurately reflects the physiological levels found in the CF lung and other sites where the PMN inflammatory response occurs (33). Approximately 1% of genes (58 of the 5,500 P. aeruginosa PAO1 probe sets on the microarray) demonstrated significantly (>2-fold) altered expression (Table 3). Of these, 34 genes were upregulated and 24 genes were downregulated in PA2206 C relative to PA2206 −, and the changes in gene expression ranged from +7.7 to −3.4 fold (Table 3). The dataset was validated by qRT-PCR, including the wild-type strain for comparison. Expression of the grx glutaredoxin (PA5129) and a glycine tRNA (PA0729.1) was decreased in the PA2206 mutant, while a glutathione S-transferase (PA2821) and the snr cytochrome (PA3032) were found to be increased (Fig. 2). These results were in accordance with the microarray analysis.

Table 3. Microarray analysis of the transcriptional influence of PA2206 in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.

| ORF ID | Gene name | Description | Fold change |

| Genes positively regulated by PA2206 | |||

| PA0321 | probable acetylpolyamine aminohydrolase | 3.8 | |

| PA0323 | spermidine/putrescine-binding periplasmic protein | 2.0 | |

| PA0472 | fiuI | probable sigma-70 factor, ECF subfamily | 2.0 |

| PA0609 | trpE | anthranilate synthetase component I | 3.0 |

| PA0649 | trpG | anthranilate synthase component II | 2.4 |

| PA0729.1 | tRNA Glycine | 2.8 | |

| PA1409 | aphA | acetylpolyamine aminohydrolase | 6.1 |

| PA1410 | periplasmic spermidine/putrescine-binding protein | 4.3 | |

| PA1912 | femI | ECF sigma factor, FemI | 2.4 |

| PA1961 | probable transcriptional regulator | 2.2 | |

| PA2033 | hypothetical protein | 2.2 | |

| PA2206 | probable transcriptional regulator | 6.4 | |

| PA2214 | major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter | 2.2 | |

| PA2215 | hypothetical protein | 3.8 | |

| PA2216 | hypothetical protein | 2.7 | |

| PA2426 | pvdS | sigma factor | 5.3 |

| PA2594 | hypothetical protein | 3.3 | |

| PA2761 | hypothetical protein | 2.2 | |

| PA3229 | hypothetical protein | 3.0 | |

| PA3515 | hypothetical protein | 2.0 | |

| PA3516 | probable lyase | 2.5 | |

| PA3517 | probable lyase | 2.0 | |

| PA3530 | hypothetical protein | 2.6 | |

| PA4515 | uncharacterized iron-regulated protein | 3.0 | |

| PA4516 | hypothetical protein | 2.5 | |

| PA4659 | probable transcriptional regulator | 2.2 | |

| PA4660 | phr | deoxyribodipyrimidine photolyase | 2.2 |

| PA4695 | ilvH | acetolactate synthase isozyme III small subunit | 2.1 |

| PA4708 | phuT | haeme-transport protein | 2.0 |

| PA4709 | probable hemin degrading factor | 2.5 | |

| PA4773 | hypothetical protein | 2.0 | |

| PA4881 | hypothetical protein | 7.7 | |

| PA5129 | grx | glutaredoxin | 2.2 |

| PA5217 | binding protein component of ABC iron transporter | 3.1 | |

| Genes negatively regulated by PA2206 | |||

| PA0105 | coxB | cytochrome c oxidase, subunit II | 0.37 |

| PA0106 | coxA | cytochrome c oxidase, subunit I | 0.37 |

| PA0788 | hypothetical protein | 0.36 | |

| PA1216 | hypothetical protein | 0.35 | |

| PA1217 | probable 2-isopropylmalate synthase | 0.50 | |

| PA1317 | cyoA | cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit II | 0.47 |

| PA2166 | hypothetical protein | 0.29 | |

| PA2747 | hypothetical protein | 0.42 | |

| PA2821 | probable glutathione S-transferase | 0.38 | |

| PA3032 | snr1 | cytochrome c Snr1 | 0.29 |

| PA3361 | lecB | fucose-binding lectin PA-IIL | 0.51 |

| PA3369 | hypothetical protein | 0.36 | |

| PA3370 | hypothetical protein | 0.32 | |

| PA3371 | hypothetical protein | 0.35 | |

| PA3416 | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component, β chain | 0.48 | |

| PA3417 | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component, α subunit | 0.50 | |

| PA3451 | hypothetical protein | 0.50 | |

| PA3788 | hypothetical protein | 0.40 | |

| PA4141 | hypothetical protein | 0.50 | |

| PA4738 | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.44 | |

| PA4739 | conserved hypothetical protein | 0.48 | |

| PA5085 | probable transcriptional regulator | 0.31 | |

| PA5481 | hypothetical protein | 0.39 | |

| PA5482 | hypothetical protein | 0.37 | |

Genes that exhibited a 2-fold or greater alteration in expression in the PA2206C strain compared to the PA2206− mutant strain (p<0.05) are listed. Positive values indicate those genes which were upregulated in the PA2206C strain while values less than 1.0 indicate those genes which were downregulated.

Figure 2. Quantitative Real Time PCR analysis confirms the influence of PA2206 on gene expression linked to the oxidative stress response.

Bacterial cultures were grown to exponential phase, and aliquots were then either untreated or exposed to a 1 mM concentration of H2O2 for 10 mins. Expression of PA3032, PA2821, PA0729.1 and PA5129 was measured as fold change relative to the proC housekeeping gene. Mean values are represented ± standard error. Consistent with the array data, expression of PA3032 and PA2821 was increased in the PA2206− mutant (white bar) compared to PA2206C (striped bar) and the wild-type (black bar) strain. Similarly, expression of PA0729.1 and PA5129 was approximately 3-fold less in the PA2206− mutant strain (p-value of <0.05 by student's ttest).

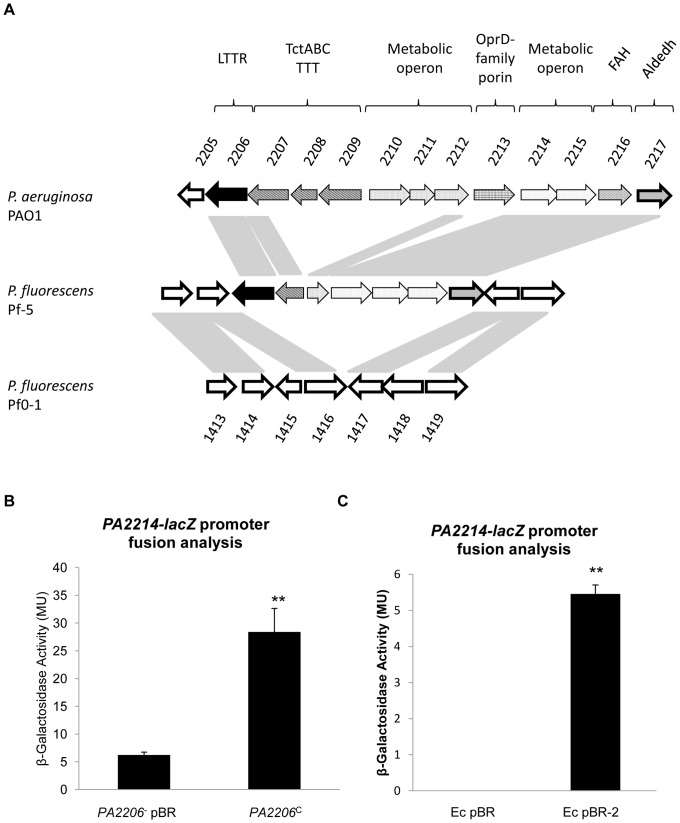

Consistent with promoter fusion and expression analysis (data not shown), the genes adjacent to PA2206 were unaltered in the transcriptome profile. However, expression of the distantly encoded PA2214-15 operon was increased 2–3 fold in the PA2206 C strain as was expression of PA2216 (Table 3). Comparative genomic analysis of publically available genome sequences revealed the PA2206-2217 region to be exclusive to P. aeruginosa, while truncated segments were encoded in the P. fluorescens Pf-5 and P. fulva 12× genomes (Fig. S5). Intriguingly, homologues of the PA2214-17 genes were identified adjacent to the PA2206 homologue in P. fluorescens Pf-5 (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, hydrogen peroxide sensitivity assays revealed comparable zones of inhibition in PA2206 and PA2215 mutants (a PA2214 mutant was not available from the mutant collection), both of which were significantly more sensitive than wild-type (Table S2). Therefore, to investigate whether these loci were indeed direct targets of the PA2206 LTTR, promoter fusion and DNA-binding analyses were undertaken.

Figure 3. PA2214-15 is under the direct transcriptional control of the PA2206 LysR regulator.

(A) Comparative genomic analysis of the metabolic-centric PA2206 region in P. aeruginosa PAO1, P. fluorescens Pf-5, and P. fluorescens Pf-O1 based on the Pseudomonas Genome Database. Single genes and operons are denoted by colour and pattern fill while homology is denoted by connecting shaded regions. P. fluorescens encodes a PA2206 homologue, which is adjacent to truncated genes corresponding to fragments of PA2207 and PA2212, both of which are downstream of a conserved PA2214-2216 homologous operon. TTT denotes a tripartite tricarboxylate transport system, FAH denotes a putative fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase activity, while Aldedh denotes a putative aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. (B) Promoter-fusion analysis of the PA2214 upstream region revealed significantly increased promoter activity in the PA2206C strain relative to PA2206−. The increase in promoter activity was consistently observed in three independent experiments consisting of three biological replicates (** p-value<0.01 by student's ttest). (C) PA2214-lacZ promoter fusion analysis performed in E. coli harbouring a PA2206-pBBR1MCS5 construct compared to vector control revealed direct regulation. Promoter activity was below baseline in the vector control (compared to empty pBBR1MCS5 plasmid), while an average of 6 Miller Units was consistently detected in the overexpressing strain (** p-value of <0.01 by student's ttest).

PA2206 positively controls PA2214-15 expression

The genomic organisation and transcriptomic data suggested PA2214-15 and/or PA2216 promoters may be direct targets of PA2206 regulation. To investigate this hypothesis, transcriptional reporter fusions were introduced into the PA2206− and PA2206C strains. β-Galactosidase assays revealed a significant increase in PA2214-15 promoter activity in the PA2206C (28.6 MU±8.0) strain compared to PA2206 − (6.2 MU±0.8) (Fig. 3B). PA2216 promoter activity was not significantly different in both strains; PA2206C (128 MU±17.0) and PA2206− (123 MU±8.7). This suggested that the PA2214-15 promoter was under the transcriptional control of PA2206.

The PA2214-lacZ transcriptional reporter fusion was subsequently introduced into E. coli harbouring a pBBR1MCS plasmid constitutively expressing PA2206 (EcpBR-2) with the aim of elucidating whether the PA2214-15 promoter was a direct target of PA2206. As E. coli does not encode a PA2206 homologue, activation of the PA2214-15 promoter in this strain would most likely be the result of a direct interaction between the LysR protein and the promoter DNA. PA2214-15 expression was significantly induced upon overexpression of PA2206, while promoter activity was not detected in the vector control suggesting that this promoter is under the direct transcriptional control of PA2206 (Fig. 3C). To confirm this direct interaction, DNA-mobility shift assays were performed.

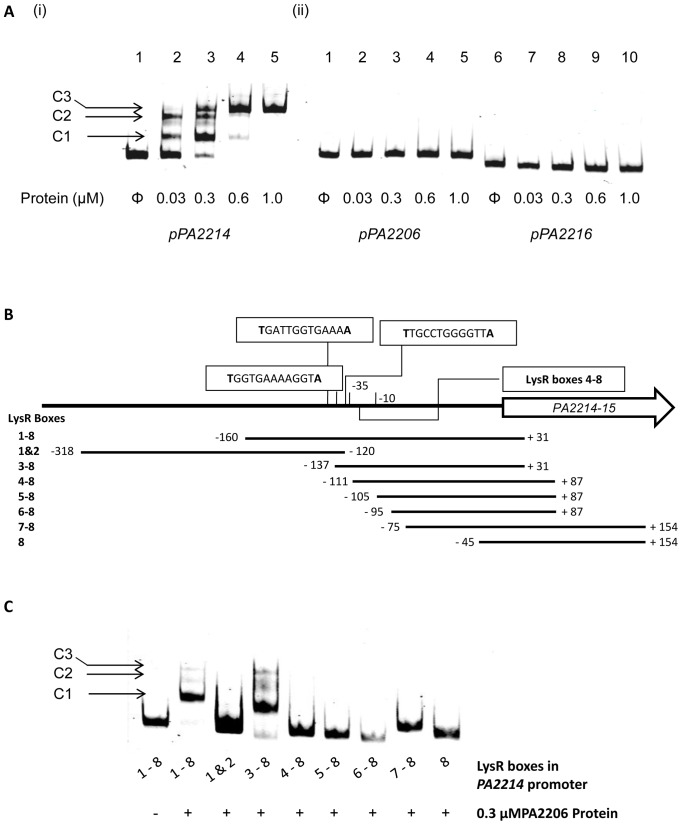

PA2206 binds adjacent to the putative −35 region of the PA2214-15 promoter

In order to provide direct evidence of the PA2206 binding interaction with the PA2214 promoter, a HisTag PA2206 construct was generated and introduced into E. coli BL21 DE cells for protein expression. After IPTG induction and purification through a nickel affinity column, protein purity and concentration were determined by SDS PAGE analysis and Bradford assay, respectively. Subsequent EMSA analysis revealed an interaction at the low nanomolar range of PA2206 protein with the −160 to +31 (relative to start of translation) region of the PA2214-15 promoter, amplified using the PA2214F and PA2214R primers (Fig. 4A and Table S1). Three complexes between the PA2206 protein and the PA2214 promoter were observed, formed in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 4). A similar stoichiometry has previously been reported for other LTTRs, notably CysB from Salmonella enterica [42]. No such interaction was observed at the −246 to −14 region of the PA2206 promoter (consistent with the lack of autoregulation observed at the transcriptional level) or the −278 to −106 region of the PA2216 promoter (Fig. 4A). Taken together with the promoter fusion analysis (Fig. 3), this would appear to confirm PA2214-15 as a direct target of PA2206 regulation.

Figure 4. PA2206 binds a LysR-box overlapping the predicted −35 box in the PA2214 promoter.

(A) EMSA analysis of the PA2214-15, PA2206 and PA2216 promoter fragments revealed PA2214-15 to be a direct PA2206 target. The protein concentration is marked below each lane while DNA promoter fragments were used at 15 fmoles. Three complexes were observed upon protein interaction with the PA2214-15 (1–3) promoter fragment at low nanomolar protein concentrations, with the C2/C3 complexes predominant at higher concentrations of PA2206 protein. The PA2206 (4–6) and PA2216 (7–9) promoter fragments did not form a complex with the PA2206 protein. (B) Schematic diagram of the location and arrangement of the LysR boxes identified upstream of the predicted transcriptional start site of PA2214. The primer positions for each of the truncated promoter fragments are outlined below and aligned with the LysR boxes contained within each amplicon. (C) Mobility shift analysis of the PA2206 protein interaction with the PA2214 promoter region. Protein was added to each reaction at 300 nM and DNA promoter fragments were used at 15 fmoles. The strong shift in lane 4 confirms that PA2206 binds to LysR box 3 overlapping the pPA2214 predicted −35 region and that this region is sufficient for the interaction to occur. PA2206 protein did not cause a shift for any of the other truncated promoter fragments.

Truncated PA2214 promoter fragments were generated with the aim of identifying the specific LysR motif with which the PA2206 protein interacts. The region of the PA2214 promoter to which PA2206 was shown to bind contains five putative LysR boxes upstream of the predicted (Bprom) transcriptional start site (Fig. 4B). Box 3 is situated adjacent to the predicted −35 region, while boxes 1 and 2 overlap each other directly upstream. Boxes 4 and 5 are situated between the predicted −35 and −10 regions, while a further three LysR boxes (boxes 6–8) were situated between the putative transcriptional and translational start sides. EMSA analysis subsequently revealed that PA2206 formed a complex with the promoter fragment containing boxes 3–8 but did not bind to the fragment containing boxes 1 & 2 (Fig. 4C). Neither did PA2206 bind to the promoter fragments located downstream of box 3 suggesting that this motif alone is sufficient for direct contact with PA2206 (Fig. 4C). Although F2-TrR (boxes 1&2) overlaps the 5′ ATTGCC region of LysR box 3, and TrAF-TrR (boxes 4–8) is directly adjacent to the 3′ region, no interaction with PA2206 was observed with these fragments, further evidence that the complete 5′-ATTGCCTGGGGTTAT-3′ LysR box is required for interaction with PA2206. It is worth noting that this sequence is highly similar to the ATAACC-N4-GGTTAT motif reported for the PcaQ LysR transcriptional regulator from Sinorhizobium meliloti [43], [44], consistent with the PA2206 LysR domain annotation. The emerging global dimension to LysR regulation suggested that there may be additional targets of PA2206 regulation in P. aeruginosa. Therefore, BioPerl analysis was undertaken to identify the extent of the PA2206 regulon.

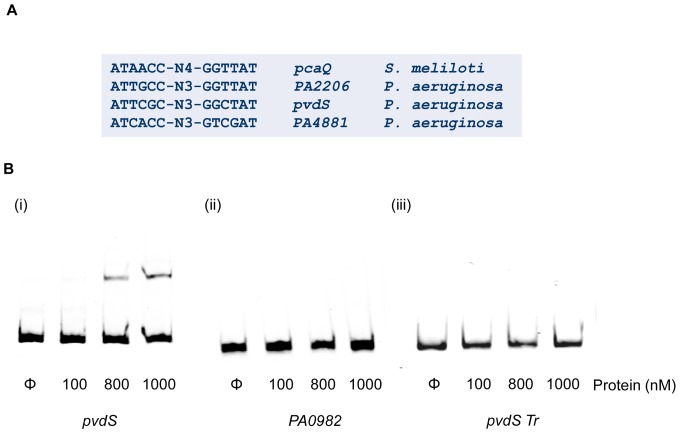

PA2206 has additional promoter targets suggesting a global regulatory role

To investigate whether PA2206 has a global regulatory role, a BioPerl script was generated to screen the PAO1 genome sequence for LysR consensus sequences with similarity to the 5′-TTGCCTGGGGTTA-3′ sequence of the PA2214-15 promoter. The absence of PA2206 homologues from species other than P. aeruginosa, with few exceptions, hindered the generation of a stringent consensus sequence. Furthermore, site-directed mutagenesis will be required to identify the nucleotides that are critical for PA2206 binding. However, LysR boxes with close sequence identity to the PA2206 LysR box were identified in 18 unique promoters (Fig. S6). Cross-referencing of this list with the transcriptomic data revealed several potential targets including the pvdS (PA2426, 5.26-fold upregulated) and PA4881 (7.66-fold upregulated) promoters. The pvdS promoter was chosen for further investigation on the basis of the relationship between iron metabolism and oxidative stress, and EMSA analysis revealed a specific interaction with the PA2206 protein in the nanomolar range (Fig. 5B). In contrast to the interaction of PA2206 with the PA2214 promoter (C1–C3 complexes, Fig. 4), the pvdS interaction occurred as a single complex migrating similar to the C2/C3 complex, with this differential stoichiometry possibly reflecting distinct affinities or oligomeric binding arrangements at each promoter [45]. This same pattern of interaction has previously been reported for the binding interaction of other LTTRs with target promoters, including that of the CatR LTTR to the catBC and clcABD promoters [12]. Binding analysis using a truncated pvdS promoter fragment downstream of the putative PA2206 box revealed no interaction suggesting that PA2206 binds to the identified consensus sequence in the pvdS promoter (Fig. 5B). In addition, PA2206 was also found to bind to the PA4881 promoter, consistent with its upregulation in the transcriptomic profile, forming C1 and C2/C3 complexes in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. S6). The specificity of these interactions was highlighted by the lack of any mobility shift with the PA0982 (Fig. 5B) and PA1874 (Fig. S6) promoters. Regulation of pvdS and PA4881 suggests a global role for PA2206 in P. aeruginosa, although further analysis incorporating Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) analysis will be required to define the full repertoire of PA2206 targets in the cell. Surprisingly, neither pvdS nor PA4881 exhibited increased susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide using simple disk diffusion assays (data not shown). Therefore, the mechanism through which PA2206 contributes to the oxidative stress response in P. aeruginosa may involve a more complex interplay between downstream targets of PA2206.

Figure 5. PA2206 has a global regulatory role in P. aeruginosa.

(A) BioPerl analysis revealed the presence of the putative PA2206 consensus sequence in the promoters of the pvdS and PA4881 genes. The arrangement and sequence similarity of the consensus sequence was similar to that of the pcaQ LTTR from S. meliloti. (B) (i) EMSA analysis of the pvdS promoter region with the PA2206 protein revealed an interaction at nanomolar concentrations. Concentrations as low as 800 nM were able to shift the pvdS promoter. (ii) The absence of binding to the PA0982 promoter probe indicates the requirement for specificity in the predicted consensus sequence. (iii) No interaction was observed between PA2206 and a truncated pvdS promoter fragment located downstream of the putative LysR box suggesting that this sequence alone is sufficient for the protein-DNA interaction to occur.

Discussion

Microbial pathogens are continuously faced with the threat of oxidative stress elicited by the host immune response, and also from the by-products of aerobic metabolism. Their ability to sense and rapidly respond to oxidative stress arising from elevated levels of ROS is central to their pathogenesis and survival. For example, the presence of pathogens such as P. aeruginosa in the human lower respiratory tract leads to the induction of host-derived mediators such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines which activate phagocytic cells including alveolar macrophages and neutrophils [46], [47]. The phagocytes target bacterial populations with the production of oxidative stress inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS), proteolytic enzymes and a range of toxic metabolites [48]. As a result P. aeruginosa has evolved a complex repertoire of strategies to overcome the deleterious effects of these and other toxic intermediates.

The response to oxidative stress is complex and highly coordinated, involving enzymatic and non-enzymatic activities and requiring multiple layers of regulation. In this study, PA2206 has been identified as an important component of transcriptional regulation required for the oxidative stress response and zebrafish lethality in P. aeruginosa. The dual involvement of transcriptional regulators in the oxidative stress response and pathogenesis has previously been reported. For example, OxyR is required for virulence of P. aeruginosa in insect and mouse models of infection [39] and also for secretion of cytotoxic factors [49]. In addition to this, Lan and colleagues demonstrated that another oxidative stress response regulator, OspR, influences levels of dissemination of P. aeruginosa in a murine model of acute pneumonia, with inactivation of OspR resulting in increased bacterial virulence [38]. In contrast, a study carried out in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium demonstrated that neither OxyR nor KatG (catalase) influence survival in the presence of neutrophils [40], while AhpC (peroxidise) is not required for virulence in a mouse model [41]. Therefore, microbes may have evolved distinct roles for these transcriptional regulators, consistent with their ecological and niche-specific requirements. It remains to be determined whether the altered pathogenesis observed upon mutation of PA2206 in the zebrafish embryo model of infection is a consequence of its reduced tolerance to oxidative stress or through independent alteration of its in vivo virulence profile.

The molecular mechanism underpinning the global regulatory role of PA2206 involves at least three direct targets; PA2214-15, pvdS, and PA4881, in addition to the possibly indirect regulation of 56 other genes during oxidative stress. PA4881 remains uncharacterised, although it has recently been shown to encode a tandem repeat protein also under the control of the redox responsive LysR protein MexT [50], [51]. Annotated as hypothetical, the PA2206-17 genomic region encodes a large number of genes encoding proteins with an apparent metabolic function. Furthermore, the positive regulation by PA2206 of several operons involved in polyamine metabolism may be significant in light of recent reports on the protective role of polyamines against oxidative stress in E. coli [52]. Re-routing metabolic flux has recently been proposed as a key mechanism through which OxyR mediates oxidative stress tolerance in P. aeruginosa [15]. Indeed, the flux of cellular metabolic pathways is emerging as a key adaptive mechanism through which both microbes and higher organisms adapt to the threat of ROS, although the molecular mechanisms governing these relationships remain to be defined [53], [54], [55], [56], [57]. It is worth noting the magnitude of the reduction in cell viability observed for the PA2206− mutant following exposure to H2O2 (Table 2) in comparison with the exquisite sensitivity following mutation of OxyR, which controls the battery of enzymes required to mount an acute response to oxidative challenge [14]. Mutation of oxyR in P. aeruginosa and other pathogens has been shown to result in an inability to grow on LB agar plates, possibly due to the autoproduction of concentrations as low as 1.2 µM H2O2 per minute [39], [58]. In addition, micromolar concentrations of H2O2 were sufficient to arrest the growth of oxyR mutants in several microbial species reinforcing its position as the master regulator of the oxidative stress response [59], [60]. Therefore, PA2206 may represent an important OxyR-independent regulatory link between perception of an exogenous stress and adaptation through realignment of lower metabolic pathways to conserve energy and facilitate survival.

The positive regulation of iron related genes by PA2206, including PvdS and both the FiuIRA and FemIRA ECF systems, supports a role for iron metabolism in the oxidative stress response in P. aeruginosa. Indeed, Palma and colleagues have previously reported induction of several iron-starvation responsive genes upon treatment with H2O2 suggesting either that cells experience iron starvation in response to oxidative stress, or that transient loss of Fur repressor function may occur [32], [33]. Furthermore, Wei and colleagues have also recently reported an OxyR-dependent link with iron homeostasis through positive regulation of pvdS during oxidative stress [15]. However, elucidating the full complexity of the role of iron uptake systems during oxidative stress will require further investigation. Notwithstanding this, the binding of PA2206 to the pvdS promoter in the nanomolar range, and the increased pvdS expression in the PA2206C strain, support a direct role for PA2206 in regulating iron homeostasis during oxidative stress. The concentration of PA2206 protein required to cause a mobility shift of the pvdS promoter was comparable to the recently reported regulation of the pvdS promoter by the LysR regulator of sulphur metabolism, CysB [61]. More recently, OxyR has also been shown to bind to the pvdS promoter [15] and regulation of the pvdS promoter by these three distinct LTTRs highlights the coordination of regulatory inputs that underpins microbial adaptation. However, although cross-talk among LTTRs may facilitate fine-tuning of the microbial stress response, it is important to distinguish the regulatory influences of OxyR and PA2206 during oxidative stress. While 28 genes that were either induced or repressed under conditions of oxidative stress [33] were differentially expressed in the PA2206C strain compared to an isogenic PA2206 − mutant, only 6 of these loci were bound by OxyR in the recent study performed by Wei and co-workers [15]. Furthermore, in a separate study, proteomic analysis of the oxyR mutant under iron limitation [62] revealed no overlap with the PA2206 transcriptomic dataset. Therefore, while transcriptomic analysis of the OxyR regulon will be required to fully appreciate the distinct patterns of regulation by OxyR and PA2206, our data would suggest that significant overlap would not be expected.

Complex adaptive responses such as oxidative stress and host pathogenesis require the input of several classes of regulatory protein, transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational. The COG prediction of post-transcriptional regulation or post-translational modification for genes altered in the transcriptome, including glutathione S-transferase (PA2821), suggested that the oxidative stress phenotype associated with loss of PA2206 function may be multifactorial. Indeed, preliminary proteomic analysis has revealed reduced production of two probable peroxidases in the PA2206− mutant and time-kill survival assays revealed that both are required for survival in the presence of 100 mM H2O2 (Haynes & O'Gara unpublished data). As expression of the genes encoding these proteins was unaltered at the transcriptional level, the influence of PA2206 on these targets is likely to be indirect. Characterizing the molecular pathways that link the transcriptional and post-transcriptional systems identified in this study will provide the focus of future investigations.

In summary, PA2206 contributes to an effective oxidative stress response and pathogenicity in P. aeruginosa. The role of PA2206 during oxidative stress appears to be independent of the OxyR pathway, although cross-talk with other transcriptional regulators must be considered. Elucidating the molecular pathways underpinning this crucial aspect of microbial pathogenesis will provide a platform for greater understanding of the process of infection in P. aeruginosa and other serious pathogens.

Supporting Information

HisTag protein purification of PA2206. Purified protein was loaded on an 10% SDS PAGE gel and visualised following Coomassie Blue staining. Imidazole concentrations used to elute each fraction are detailed below the gel.

(PPT)

PA2206 expression is induced in response to 1 mM menadione. Bacterial cultures grown to exponential phase were exposed to a 1 mM concentration of menadione and expression of PA2206 was found to be significantly increased. Mean values are represented +/− standard error.

(PPT)

PA2206 does not autoregulate its own promoter activity. PA2206-lacZ promoter fusion analysis revealed no difference in β-galactosidase activity in wild-type, PA2206 − or PA2206C strains. Data presented contains three biological replicates and is representative of three independent experiments (p-value≤0.01 by student's ttest).

(PPT)

Growth profiling of wild-type and PA2206− strains in the presence of ROS. Addition of 20 mM H2O2 to exponentially growing cells led to significant reduction in growth rate in the PA2206− strain while the wild-type was unaffected. Similarly, addition of 40 mM menadione also resulted in reduced growth rate in the mutant strain. Significance of the growth impairment was confirmed by statistical analysis (Students ttest * p-value≤0.05, ** p-value≤0.005, *** p-value≤0.001).

(PPT)

Comparative genomic analysis of the metabolic-centric PA2206 region. Analysis of all available P. aeruginosa genome sequences in which PA2206 homologues were identified, including P. fluorescens Pf-5 and P. fulva 12×, based on the Pseudomonas Genome Database. Single genes and operons are denoted by colour and pattern-fill. Gene content and organisation is highly conserved in P. aeruginosa strains. P. fluorescens encodes a PA2206 homologue, which is adjacent to truncated genes corresponding to fragments of PA2207 and PA2212, both of which are downstream of a conserved PA2214-2216 homologous operon. P. fulva encodes a TRAP system inserted between homologues of the PA2213 and PA2216 genes.

(PPT)

(A) Genome-wide BioPerl analysis of the 5′-TTGCCTGGGGTTA-3′ sequence revealed 18 promoters that contained putative LysR boxes with similarity (p<1e−04) to the PA2206 motif. MEME analysis of these LysR boxes led to the construction of a PA2206 consensus motif. Genes whose expression was altered in the PA2206C strain are highlighted in bold and the fold changes are indicated in parentheses. (B) EMSA analysis reveals a binding interaction between PA2206 and the PA4881 promoter, forming C1 and C2/C3 complexes in a concentration dependent manner. No interaction was observed at the PA1874 promoter, consistent with its lack of induction in the transcriptomic profile.

(PPT)

Primers used in this study.

(DOC)

Disk diffusion analysis of the oxidative stress sensitivity of wild-type P. aeruginosa and PA2206− and PA2215− mutants. Analysis performed using 10 µl of a 30% (w/w) solution of H2O2 (8.8 M).

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Claire Adams for critical reading of the manuscript, Julie O'Callaghan for cytotoxicity, adhesion, and invasion assays, Patrick Browne for providing the BioPerl script analysis, and Mattieu Barret for analysis of transcriptomic data. We also thank Pat Higgins for excellent technical assistance.

Funding Statement

This research was supported in part by grants awarded by the European Commission (MTKD-CT-2006-042062; O36314; FP7-PEOPLE-2009-RG, EU 256596, 2010–2013), Science Foundation Ireland (SFI 04/BR/B0597; 07/IN.1/B948; 08/RFP/GEN1295; 08/RFP/GEN1319; 09/RFP/BMT2350), the Department of Agriculture and Food (DAF RSF 06 321; DAF RSF 06 377; FIRM 08/RDC/629), the Irish Research Council for Science, Engineering and Technology (05/EDIV/FP107; PD/2011/2414), the Health Research Board (RP/2006/271; RP/2007/290; HRA/2009/146), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA2006-PhD-S-21; EPA2008-PhD-S-2), the Marine Institute (Beaufort award C2CRA 2007/082), the Higher Education Authority of Ireland (PRTLI3) and the Health Service Executive (HSE) surveillance fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding was received for this study.

References

- 1. Maddocks SE, Oyston PC (2008) Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154: 3609–3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tropel D, van der Meer JR (2004) Bacterial transcriptional regulators for degradation pathways of aromatic compounds. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68: 474–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gonzalez-Flecha B, Demple B (1999) Role for the oxyS gene in regulation of intracellular hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181: 3833–3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lahiri A, Das P, Chakravortty D (2008) The LysR-type transcriptional regulator Hrg counteracts phagocyte oxidative burst and imparts survival advantage to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology 154: 2837–2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verneuil N, Rince A, Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Fadda G, et al. (2005) Contribution of a PerR-like regulator to the oxidative-stress response and virulence of Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology 151: 3997–4004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braz VS, da Silva Neto JF, Italiani VC, Marques MV (2010) CztR, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator involved in zinc homeostasis and oxidative stress defense in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol 192: 5480–5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turlin E, Sismeiro O, Le Caer JP, Labas V, Danchin A, et al. (2005) 3-phenylpropionate catabolism and the Escherichia coli oxidative stress response. Res Microbiol 156: 312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, et al. (2000) Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406: 959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansen CR, Pressler T, Hoiby N (2008) Early aggressive eradication therapy for intermittent Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway colonization in cystic fibrosis patients: 15 years experience. J Cyst Fibros 7: 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoiby N, Koch C (1990) Cystic fibrosis. 1. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis and its management. Thorax 45: 881–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neu HC (1983) The role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 11 Suppl B: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parsek MR, McFall SM, Shinabarger DL, Chakrabarty AM (1994) Interaction of two LysR-type regulatory proteins CatR and ClcR with heterologous promoters: functional and evolutionary implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 12393–12397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilson R, Dowling RB, Jackson AD (1996) The biology of bacterial colonization and invasion of the respiratory mucosa. Eur Respir J 9: 1523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ochsner UA, Vasil ML, Alsabbagh E, Parvatiyar K, Hassett DJ (2000) Role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxyR-recG operon in oxidative stress defense and DNA repair: OxyR-dependent regulation of katB-ankB, ahpB, and ahpC-ahpF . J Bacteriol 182: 4533–4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wei Q, Le Minh PN, Dotsch A, Hildebrand F, Panmanee W, et al. (2012) Global regulation of gene expression by OxyR in an important human opportunistic pathogen. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 4320–4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stajich JE, Block D, Boulez K, Brenner SE, Chervitz SA, et al. (2002) The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res 12: 1611–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbour, NY: Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press.

- 18. Cornelis P, Anjaiah V, Koedam N, Delfosse P, Jacques P, et al. (1992) Stability, frequency and multiplicity of transposon insertions in the pyoverdine region in the chromosomes of different fluorescent pseudomonads. J Gen Microbiol 138: 1337–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, et al. (2003) Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 14339–14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris AG, Hinds FE, Beckhouse AG, Kolesnikow T, Hazell SL (2002) Resistance to hydrogen peroxide in Helicobacter pylori: role of catalase (KatA) and Fur, and functional analysis of a novel gene product designated ‘KatA-associated protein’, KapA (HP0874). Microbiology 148: 3813–3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee JS, Heo YJ, Lee JK, Cho YH (2005) KatA, the major catalase, is critical for osmoprotection and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Infect Immun 73: 4399–4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heeb S, Valverde C, Gigot-Bonnefoy C, Haas D (2005) Role of the stress sigma factor RpoS in GacA/RsmA-controlled secondary metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. FEMS Microbiol Lett 243: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF (1995) Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn 203: 253–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Winsor GL, Van Rossum T, Lo R, Khaira B, Whiteside MD, et al. (2009) Pseudomonas Genome Database: facilitating user-friendly, comprehensive comparisons of microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D483–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abbott JC, Aanensen DM, Rutherford K, Butcher S, Spratt BG (2005) WebACT–an online companion for the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics 21: 3665–3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, et al. (1995) Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166: 175–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spaink HP, Okker RJH, Wijffelman CA, Pees E, Lugtenberg BJJ (1987) Promoters in the Nodulation Region of the Rhizobium-Leguminosarum Sym Plasmid Prl1ji. Plant Molecular Biology 9: 27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, et al. (2003) Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4: 249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the False Discovery Rate. A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Statist Soc B (Methodol) 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Savli H, Karadenizli A, Kolayli F, Gundes S, Ozbek U, et al. (2003) Expression stability of six housekeeping genes: A proposal for resistance gene quantification studies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. J Med Microbiol 52: 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang W, Small DA, Toghrol F, Bentley WE (2005) Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals induction of pyocin genes in response to hydrogen peroxide. BMC Genomics 6: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Palma M, DeLuca D, Worgall S, Quadri LE (2004) Transcriptome analysis of the response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol 186: 248–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salunkhe P, Topfer T, Buer J, Tummler B (2005) Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the steady-state response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol 187: 2565–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chugani S, Greenberg EP (2007) The influence of human respiratory epithelia on Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene expression. Microb Pathog 42: 29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frisk A, Schurr JR, Wang G, Bertucci DC, Marrero L, et al. (2004) Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa after interaction with human airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun 72: 5433–5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mark GL, Dow JM, Kiely PD, Higgins H, Haynes J, et al. (2005) Transcriptome profiling of bacterial responses to root exudates identifies genes involved in microbe-plant interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 17454–17459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lan L, Murray TS, Kazmierczak BI, He C (2010) Pseudomonas aeruginosa OspR is an oxidative stress sensing regulator that affects pigment production, antibiotic resistance and dissemination during infection. Mol Microbiol 75: 76–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lau GW, Britigan BE, Hassett DJ (2005) Pseudomonas aeruginosa OxyR is required for full virulence in rodent and insect models of infection and for resistance to human neutrophils. Infect Immun 73: 2550–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Papp-Szabo E, Firtel M, Josephy PD (1994) Comparison of the sensitivities of Salmonella typhimurium oxyR and katG mutants to killing by human neutrophils. Infect Immun 62: 2662–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor PD, Inchley CJ, Gallagher MP (1998) The Salmonella typhimurium AhpC polypeptide is not essential for virulence in BALB/c mice but is recognized as an antigen during infection. Infect Immun 66: 3208–3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hryniewicz MM, Kredich NM (1994) Stoichiometry of binding of CysB to the cysJIH, cysK, and cysP promoter regions of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 176: 3673–3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. MacLean AM, Anstey MI, Finan TM (2008) Binding site determinants for the LysR-type transcriptional regulator PcaQ in the legume endosymbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 190: 1237–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maclean AM, Haerty W, Golding GB, Finan TM (2011) The LysR-type PcaQ protein regulates expression of a protocatechuate-inducible ABC-type transport system in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Microbiology 157: 2522–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fradrich C, March A, Fiege K, Hartmann A, Jahn D, et al. (2012) The transcription factor AlsR binds and regulates the promoter of the alsSD operon responsible for acetoin formation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 194: 1100–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheung DO, Halsey K, Speert DP (2000) Role of pulmonary alveolar macrophages in defense of the lung against Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Infect Immun 68: 4585–4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Salva PS, Doyle NA, Graham L, Eigen H, Doerschuk CM (1996) TNF-alpha, IL-8, soluble ICAM-1, and neutrophils in sputum of cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Pulmonol 21: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chmiel JF, Davis PB (2003) State of the art: why do the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis become infected and why can't they clear the infection? Respir Res 4: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Melstrom KA Jr, Kozlowski R, Hassett DJ, Suzuki H, Bates DM, et al. (2007) Cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas secreted exotoxins requires OxyR expression. J Surg Res 143: 50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fargier E, Mac Aogain M, Mooij MJ, Woods DF, Morrissey JP, et al. (2012) MexT functions as a redox-responsive regulator modulating disulfide stress resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 194: 3502–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tian ZX, Fargier E, Mac Aogain M, Adams C, Wang YP, et al. (2009) Transcriptome profiling defines a novel regulon modulated by the LysR-type transcriptional regulator MexT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Nucleic Acids Res 37: 7546–7559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tkachenko AG, Akhova AV, Shumkov MS, Nesterova LY (2012) Polyamines reduce oxidative stress in Escherichia coli cells exposed to bactericidal antibiotics. Res Microbiol 163: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gardner PR, Fridovich I (1991) Superoxide sensitivity of the Escherichia coli aconitase. J Biol Chem 266: 19328–19333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liochev SI, Fridovich I (1992) Fumarase C, the stable fumarase of Escherichia coli, is controlled by the soxRS regulon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89: 5892–5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mailloux RJ, Lemire J, Appanna VD (2011) Metabolic networks to combat oxidative stress in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 99: 433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rowley DL, Wolf RE Jr (1991) Molecular characterization of the Escherichia coli K-12 zwf gene encoding glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol 173: 968–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V (2005) Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: a target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360: 2335–2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hennequin C, Forestier C (2009) OxyR, a LysR-type regulator involved in Klebsiella pneumoniae mucosal and abiotic colonization. Infect Immun 77: 5449–5457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Flores-Cruz Z, Allen C (2011) Necessity of OxyR for the hydrogen peroxide stress response and full virulence in Ralstonia solanacearum. Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 6426–6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Johnson JR, Clabots C, Rosen H (2006) Effect of inactivation of the global oxidative stress regulator oxyR on the colonization ability of Escherichia coli O1:K1:H7 in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun 74: 461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Imperi F, Tiburzi F, Fimia GM, Visca P (2010) Transcriptional control of the pvdS iron starvation sigma factor gene by the master regulator of sulfur metabolism CysB in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol 12: 1630–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vinckx T, Wei Q, Matthijs S, Cornelis P (2010) The Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxidative stress regulator OxyR influences production of pyocyanin and rhamnolipids: protective role of pyocyanin. Microbiology 156: 678–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HisTag protein purification of PA2206. Purified protein was loaded on an 10% SDS PAGE gel and visualised following Coomassie Blue staining. Imidazole concentrations used to elute each fraction are detailed below the gel.

(PPT)

PA2206 expression is induced in response to 1 mM menadione. Bacterial cultures grown to exponential phase were exposed to a 1 mM concentration of menadione and expression of PA2206 was found to be significantly increased. Mean values are represented +/− standard error.

(PPT)

PA2206 does not autoregulate its own promoter activity. PA2206-lacZ promoter fusion analysis revealed no difference in β-galactosidase activity in wild-type, PA2206 − or PA2206C strains. Data presented contains three biological replicates and is representative of three independent experiments (p-value≤0.01 by student's ttest).

(PPT)

Growth profiling of wild-type and PA2206− strains in the presence of ROS. Addition of 20 mM H2O2 to exponentially growing cells led to significant reduction in growth rate in the PA2206− strain while the wild-type was unaffected. Similarly, addition of 40 mM menadione also resulted in reduced growth rate in the mutant strain. Significance of the growth impairment was confirmed by statistical analysis (Students ttest * p-value≤0.05, ** p-value≤0.005, *** p-value≤0.001).

(PPT)

Comparative genomic analysis of the metabolic-centric PA2206 region. Analysis of all available P. aeruginosa genome sequences in which PA2206 homologues were identified, including P. fluorescens Pf-5 and P. fulva 12×, based on the Pseudomonas Genome Database. Single genes and operons are denoted by colour and pattern-fill. Gene content and organisation is highly conserved in P. aeruginosa strains. P. fluorescens encodes a PA2206 homologue, which is adjacent to truncated genes corresponding to fragments of PA2207 and PA2212, both of which are downstream of a conserved PA2214-2216 homologous operon. P. fulva encodes a TRAP system inserted between homologues of the PA2213 and PA2216 genes.

(PPT)

(A) Genome-wide BioPerl analysis of the 5′-TTGCCTGGGGTTA-3′ sequence revealed 18 promoters that contained putative LysR boxes with similarity (p<1e−04) to the PA2206 motif. MEME analysis of these LysR boxes led to the construction of a PA2206 consensus motif. Genes whose expression was altered in the PA2206C strain are highlighted in bold and the fold changes are indicated in parentheses. (B) EMSA analysis reveals a binding interaction between PA2206 and the PA4881 promoter, forming C1 and C2/C3 complexes in a concentration dependent manner. No interaction was observed at the PA1874 promoter, consistent with its lack of induction in the transcriptomic profile.

(PPT)

Primers used in this study.

(DOC)

Disk diffusion analysis of the oxidative stress sensitivity of wild-type P. aeruginosa and PA2206− and PA2215− mutants. Analysis performed using 10 µl of a 30% (w/w) solution of H2O2 (8.8 M).

(DOC)