Abstract

Gas-phase ion/ion reactions are emerging as useful and flexible means for the manipulation and characterization of peptide and protein biopolymers. Acid/base-like chemical reactions (i.e., proton transfer reactions) and reduction/oxidation (redox) reactions (i.e., electron transfer reactions) represent relatively mature classes of gas-phase chemical reactions. Even so, especially in regards to redox chemistry, the widespread utility of these two types of chemistries is undergoing rapid growth and development. Additionally, a relatively new class of gas-phase ion/ion transformations is emerging which involves the selective formation of functional-group-specific covalent bonds. This feature details our current work and perspective on the developments and current capabilities of these three areas of ion/ion chemistry with an eye towards possible future directions of the field.

I. Introduction

Since the initial investigations of interactions between oppositely charged ions in the gas-phase conducted more than 100 years ago by Thompson and Rutherford,1,2 the vast majority of such “ion/ion” reactions to date have involved singly charged reactant species. While the study of these reactions is complicated due to their generation of neutral products, the reaction kinetics nonetheless have important implications in the fields of atmospheric chemistry, combustion physics, and plasma physics.3,4,5 The advent of electrospray ionization (ESI) has enabled the facile generation of multiply charged gas-phase ions,6,7 providing for reactions between multiply charged ions of opposing polarities, the charged products of which are readily amendable to investigation by mass spectrometry.8,9,10,11 Over the past two decades, a large body of of mass spectrometric research has focused on acid/base (viz. proton transfer) and reduction/oxidation (viz. electron transfer) ion/ion reactions involving a wide array of analytes. Comprehensive reviews detailing the instrumentation, reaction phenomenologies and dynamics, and applications of these two classes of ion/ion reactions have been published previously.9,11,12,13,14 A relatively new class of gas-phase ion/ion chemistry has recently emerged which is concerned with the selective formation of covalent bonds.

Here, we aim to review our perspective on recent advances in the gas-phase ion/ion chemistries of peptides and proteins and detail the current and potential applications of such reactions. Recent advances in instrumentation facilitating the study and use of ion/ion reactions, discussions of reaction thermodynamics and kinetics, as well as the reaction phenomenologies detailed in previous reviews will be briefly discussed herein for the sake of clarity. Gas-phase acid/base reactions, which for the purpose of this discussion will also include other types of ion exchange or transfer reactions (e.g., metal cation exchange reactions), and redox reactions represent relatively mature classes of ion/ion interactions. As such, particular emphasis will be devoted herein to the development and applications of reactions involving covalent chemistries.

II. Instrumentation

Mass spectrometry instrumentation designed to facilitate ion/ion reactions has been well reviewed previously.9,11,13 Rather than provide a detailed history of the instrumentation evolution, we aim to provide a brief discussion of instrumentation development which contextualizes and conveys the widespread current and future use of ion/ion reactions. Briefly, instruments enabling these studies have utilized ESI, or one of its derivatives, and can be classified into one of two general classes based on the reaction conditions: (i) reactions occuring at or near atmospheric pressure prior to entry into the mass spectrometer, and (ii) reactions occuring within the confines of an electrodynamic ion trap mass spectrometer. Instruments enabling the first reaction type typically employ a front-end reaction vessel and are much less common today, though they do provide some advantages, such as the ease of adaptation to different mass analyzers. Earlier instruments of this type utilizing Y-tube reactors8,15 and atmospheric charge neutralization apparati10,16 have been reviewed previously9 and the reader is referred to the original descriptions for further information. Though there have been some recent reports of front-end ion/ion reactions without the use of dedicated reaction chambers,17 experiments utilizing the second reaction type constitute the overwhelming majority of current instrumental setups.

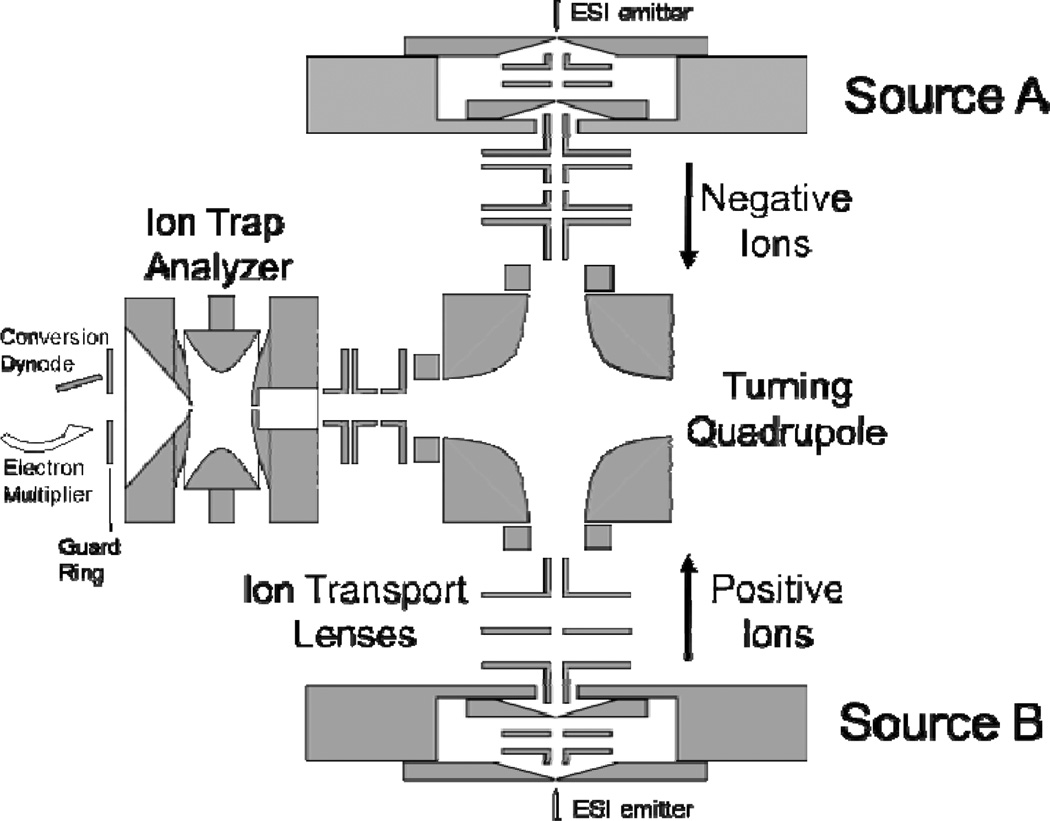

Much of the early work devoted to the study of ion/ion reactions was carried out in 3-D quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometers. The bipolar storage and spatial overlap of the oppositely charged ion clouds within these devices makes 3-D ion traps particularly well suited reaction vessels for gas-phase ion/ion reactions.18 Quadrupole ion trap instruments also conveniently provide for the use of multiple stages of “tandem-in-time” MSn experiments (viz. multiple steps of precursor ion isolation followed by reaction/analysis).19 Typically, this has been achieved using an arrangement such as that depicted in Fig. 1.20 Ions from two different ion sources are formed outside of the ion trap and are sequentially injected; here, cations are injected from one ESI source and anions are injected from a second ESI source. In between ion injections, one ion population may be isolated and/or activated. The reaction period is defined as the mutual bipolar storage period of the two populations of oppositely charged ions.21 Many different iterations of such instrument geometries on several different instrument platforms have been developed and previously described in detail.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of a quadrupole ion trap mass analyzer equipped for ion/ion reactions via sequential axial injection (through the end-cap electrode). Reprinted from ref. 20 [original source “Figure 1: Schematic diagram (not to scale) of the Dueling ESI ion trap mass spectrometer”], Copyright 2002 Elsevier Science, Inc., with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media.

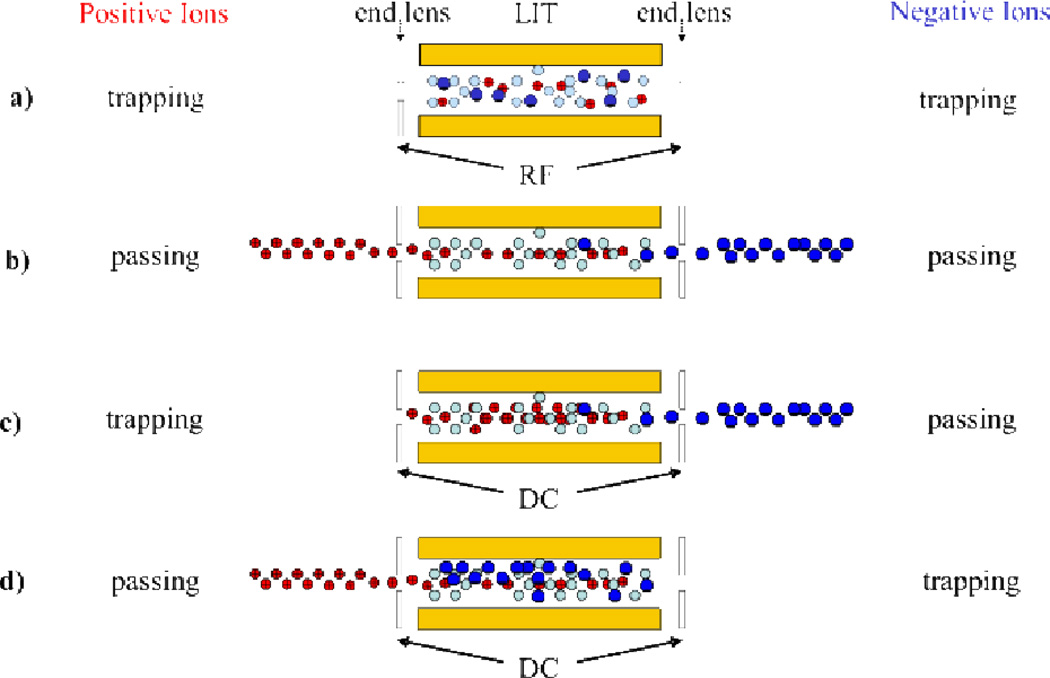

While it is beyond the scope of the present discussion to provide an in depth discussion of the instrumentation developments that have facilitated ion/ion reactions, we highlight here the recent advances associated with linear ion traps (LIT) and hybrid-type instruments (viz. instruments that combine both ion trapping and transmission mode capabilities). Ion/ion reactions performed in linear ion traps have several distinct advantages to those performed in 3-D ion traps, namely improved dynamic range and enhanced efficiency in coupling to external ion sources, detectors, and other mass analyzers.13 However, the conventional storage technique of linear ion traps, which uses static DC potentials applied to containment lenses located on either end of the quadrupole array to confine ions in the axial dimension, is not amendable to the bipolar storage of oppositely charged ions (i.e., depending on the polarity of the static potentials, one ion polarity would not be effectively contained). As such, two different techniques have been developed to provide for ion/ion reactions in linear ion traps (Fig. 2). The first, termed mutual storage mode (Fig. 2a), utilizes radiofrequency potentials on the end-cap lenses (applied either directly or by unbalancing the drive RF of the quadrupole array) to confine both ion polarities in the z-dimension.22,23 The second technique, termed transmission mode, involves passing ions through the linear ion trap.24,25,26,27 Ion/ion reactions can be performed in transmission mode by passing both cations and anions through the linear ion trap (Fig. 2b), by trapping cations within the trap while “washing” the anions over the positive ions (Fig. 2c), and by trapping anions within the trap while “washing” the cations over the negative ions (Fig. 2d). Transmission mode reactions take advantage of the high ion injection/transmission efficiencies and the long axis of the quadrupole array to achieve good spatial overlap of the two ion populations. In addition to a lack of required hardware modification, these types of reactions have shown comparable efficiency to mutual storage reactions.26 Ion/ion reactions of these two types have been implemented on many commercial platforms, including reactions in the traveling wave ion guide of a hybrid quadrupole/ion mobility/time of flight (Q-IMS-TOF),28 triple quadrupole,23,24,26 quadrupole/time of flight (Q-TOF),29 LIT/orbitrap,30 and LIT/Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (LIT-FTICR)31 instruments, thereby making these types of chemistries more accessible to a wider range of instrument types. In fact, current research is increasingly focused on developing instrument platforms specifically tailored to performing ion/ion reactions32 and several commercial instruments now come equipped with ion/ion reaction capabilities. With the increased availability and utility of instrument platforms that support various ion/ion reaction studies, specifically linear ion trap and hybrid-type instruments, the use of ion/ion reactions in analytical mass spectrometry experiments is expected to continue to increase.

Fig. 2.

Ion/ion reactions in a linear ion trap can be performed using either (a) mutual storage mode or (b), (c), (d) a form of transmission mode. (b), (c), and (d) reprinted from ref. 13 [original source “Scheme 2: Three methods for effecting transmission mode ion/ion reaction experiments in a LIT: (I) passing ions of both polarities, (II) positive ion storage/negative ion transmission, (III) positive ion transmission/negative ion storage”], Copyright 2008 Elsevier, Inc., with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media.

III. Reaction dynamics and thermodynamics

The thermodynamics and kinetics associated with ion/ion reactions have been described in detail previously.9,11,33,34 A brief discussion of reaction dynamics and thermodynamics is included here to facilitate fundamental understanding of the reaction chemistries discussed below.

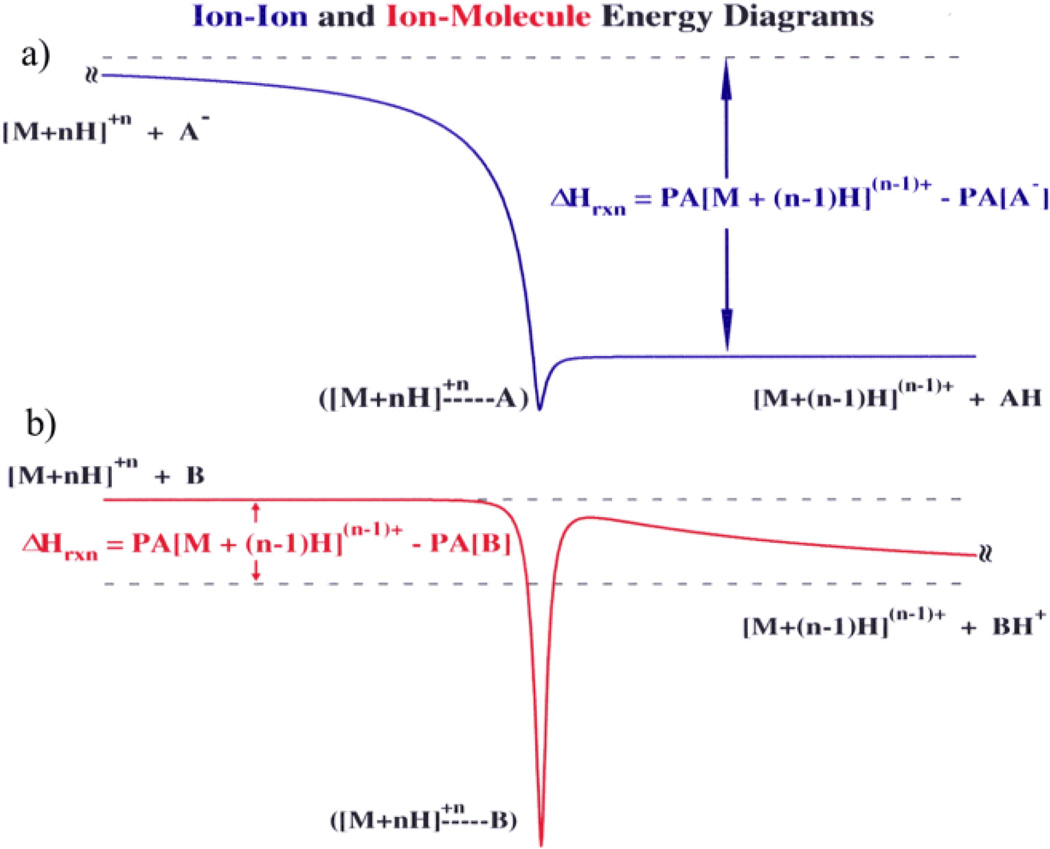

A. Thermodynamics and shapes of energy surfaces

Comparing the lowest energy surfaces associated with acid/base ion/ion and ion/molecule reactions is useful in distinguishing key differences between the two types of bimolecular reactions.33 Generic energy diagrams for the two processes (viz. proton transfer from multiply charged cations to either an anionic or neutral base) are shown in Fig. 3:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The shape of the entrance channel for the ion/ion reaction (Fig. 3a) is largely governed by the long-range, charge-dependent attractive −Z1Z2e2/r potential, while that of the exit channel is dominated by shorter-range ion-dipole and ion-induced dipole forces (assuming that one of the products is completely neutralized). Here, e is the electronic charge, r is the distance between the two ions, and Z1 and Z2 represent the unit charges of the cation and anion, respectively. On the other hand, for ion/molecule reactions the entrance channel is dominated by shorter-range polarization forces in analogy with the exit channel of an ion/ion reaction.. The exit channel, in which the two products are formed with the same charge polarity, is dominated by a repulsive + Z1Z2e2/r potential once the transition state is reached, which creates a ‘Coulomb barrier’ in the exit channel. There is no Coulomb barrier present in the exit channel of the ion/ion reaction (though there may be a chemical barrier, depending on the reaction).

Fig. 3.

Generic energy diagrams for (a) an ion/ion proton transfer reaction and (b) and an ion/molecule proton transfer reaction. Reprinted with permission from ref. 33. Copyright 1996 American Chemical Society.

In addition to differences in the qualitative shapes of the energy surfaces between ion/ion and ion/molecule proton transfer reactions, the reaction enthalpies, as determined by the differences in relevant proton affinities (PA) of the two reaction partners, is generally far different. Reaction enthalpies are typically much more negative (exothermic) for the ion/ion reaction compared to the ion/molecule reaction:

| (3) |

| (4) |

This relative difference in exothermicities is due to the significant energy disparity between the lowest proton affinities of anions and the highest proton affinities of neutral bases. This simply reflects the high exothermicity of neutralization reactions. As the extent of excess protonation increases, ion/ion reaction exothermicities increase due to the decreasing proton affinity of the positive ion(s). As a result, reaction (1) is usually exothermic by at least 100 kcal/mol for any charge n. From a thermodynamic perspective, this implies that, in general, a reaction should proceed between any two ions of opposite polarity.

B. Kinetics

Under reaction conditions in which there is a large excess of singly charged reagent anions in the presence of multiply protonated cations, pseudo-first order kinetics for the reaction of the cations can be achieved. Under such conditions, the rate of depletion of the cationic reactant has been observed to show a charge-squared dependence.33 Such a dependence is consistent with the r−1 attractive potential (see Fig. 3a) for the formation of a bound orbit between the two reaction partners (with varying eccentricities, or deviations from a perfect circular orbit) as the rate limiting step.3,35,36 The rate constant for the formation of a stable orbit is given by relation (5):

| (5) |

where v is the relative velocity of the bipolar ions, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, and μ is the reduced mass of the two reactants. Due to the long-range attractive potential, stable orbits can be achieved at distances too far for chemistry to occur. For orbits of high eccentricity, the reactants may reach a distance sufficiently close for reaction during a portion of the orbit. However, for orbits of low eccentricity, a mechanism to reduce the interparticle distance must be in play to bring the oppositely charged ions sufficiently close for reaction. Interaction with a third body, for example, could either destroy the complex or reduce the relative velocity of the pair, thereby leading to a smaller orbital distance. The use of a light bath gas, such as helium, minimizes scattering of the higher mass ions and, as a result, tends to minimize destruction of the complex. However, a more likely process for reduction in the orbital distance arises from a so-called “tidal” effect.37,38 Large polyatomic ions (e.g. protein ions), have significant internal structure that can be influenced by the changing electric field associated with an elliptical orbit. Changes in the internal structures of the reactant ions can lead to a transfer of relative translational energy into internal energy. In the case of a multiply protonated ion, for example, the electric field of the oppositely charged ion can lead to intramolecular proton transfer with the net transformation of translational to vibrational energy.36

C. Partitioning from an orbiting pair

The formation of an orbiting pair appears to be the rate limiting process for ion/ion reactions of large polyatomics ions. Once trapped by their mutual attraction, the oppositely charged ions can undergo several competing reactive processes that lead to products.39,40 Two major overall processes are the transfer of a small charged particle (i.e., a proton or an electron) at a crossing point in the interaction potential for the two ions and the formation of a long-lived chemical complex. The former can occur without the ions coming into intimate contact (i.e., they can occur as the reactants fly past one another) while the latter is analogous to the formation of a long-lived complex in an ion-molecule interaction (i.e., a sticky collision). Upon orbtial complex formation, long range proton transfer competes with physical “sticky” collisions. The first generation proton transfer products can either escape one another due to the reduction in mutual attraction as a result of the reduction of the charge of each ion, or remain trapped in the mutual attraction of the charge-reduced products. If the first generation proton transfer products remain trapped by their mutual attraction, a second proton transfer might occur as the collapse of the orbit proceeds, leading to escape of the second generation products or the formation of another bound orbit with further charge-reduced partners. The process can repeat until the trapped ions become close enough to undergo a sticky collision to generate a complex, which can be cooled by collisions and observed as an intact complex or which can undergo dissociation (kdiss).

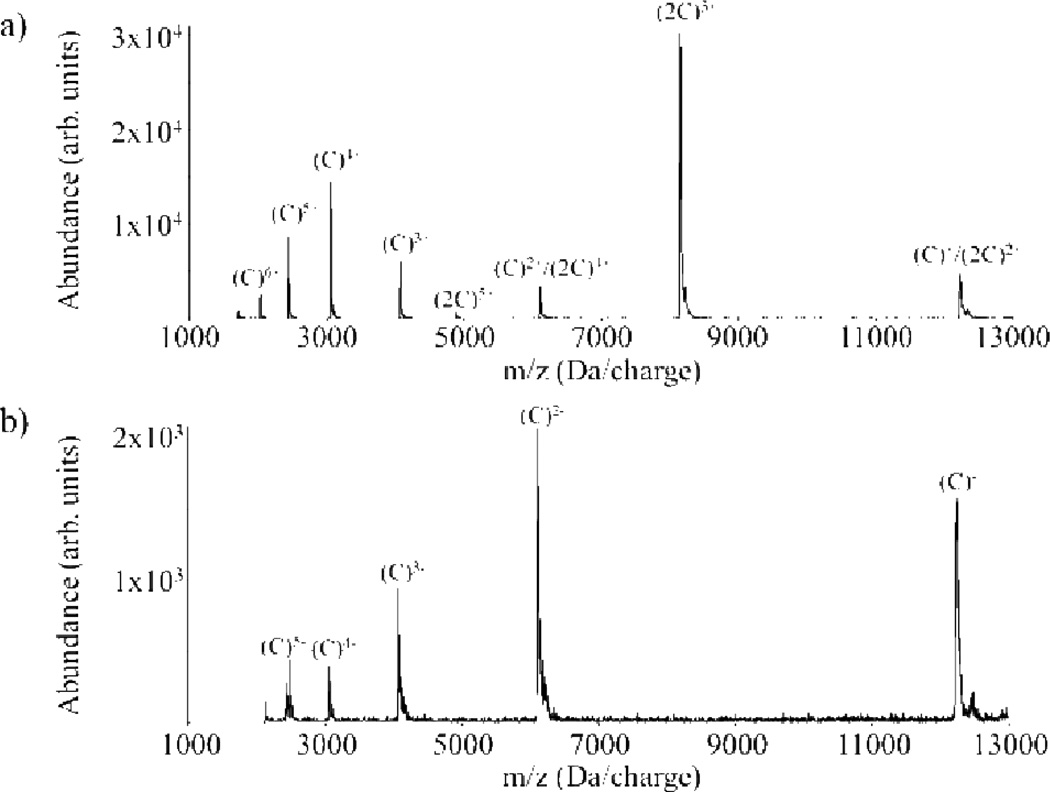

Experimental evidence for proton transfer within the bound orbit followed by escape as well as long-lived complex formation is shown in Fig. 4, which provides the post-ion/ion reaction data (positive ions in Fig. 4a and negative ions in Fig. 4b) for the +8 and −5 charge states of cytochrome c.36 This experiment highlights the importance of kinetic control in gas-phase ion/ion reactions as the thermodynamically favored products are those that lead to complex neutralization of the lower charged reactant [i.e., (C)5−]. The appearance of the incomplete proton transfer products [i.e., (C)6+, (C)5+, and (C)4+ in Fig. 4a and (C)4−, (C)3−, (C)2−, and (C)− in Fig. 4b] reflect proton transfers at relatively long range with subsequent escape of the proton transfer products from a bound orbit.

Fig. 4.

Product ion spectra from an ion/ion reaction between the +8 and −5 charge states of cytochrome c observed in (a) the positive ion mode and (b) the negative ion mode (both under the same reaction conditions). Reprinted with permission from ref. 36. Copyright 2003 American Chemical Society.

IV. Acid/base chemistry

The first reports of ion/ion reaction studies involving multiply charged polyatomic ions date to the early nineties, when Y-tube atmospheric reaction chambers were used to perform proton transfer reactions.8,15 Soon after, a wide variety of reactions based on acid/base chemistry in the dilute gas-phase were explored, generally using 3-D ion trap mass spectrometers.9 In discussing the variations of gas-phase acid/base ion/ion reaction phenomenologies reported to date, it is useful to categorize the reactions based on the precursor ion charges, viz. reactions between multiply charged cations and singly charged anions, reactions between multiply charged anions and singly charged cations, and reactions between multiply charged cations and multiply charged anions (Table 1). The list is not exhaustive. Rather, it is meant to illustrate the wide array of acid/base and other ion transfer reactions shown to occur in the gas-phase. The following sections break down ion/ion reactions involving single proton transfer, mutliple proton transfer in a single collision (with emphasis on charge inversion), other ion transfers, and complex formation.

Table 1.

Acid/base and other ion transfer ion/ion reactions. M = intact parent analyte, Y = intact parent reagent, X = metal cation, L = ligandion, Z = metal anion.

| Precursor Charges |

Reaction Number |

Reaction Name | Reaction Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiply charged cations/singly charged anions | 1.1 | Proton transfer (PT) | (M + nH)n+ + Y− → (M + (n − 1)H)(n − 1)+ + YH |

| 1.2 | Multiple proton transfer | (M + nH)n+ + Y− → (M + (n − m)H)(n − m)+ + YHm(m−1)+ | |

| 1.3 | Solvent transfer with PT | (M + nH)n+ + YSm− → (M + (n − 1)H)(n − 1)+ (m − p)S + YH + pS | |

| 1.4 | Cation transfer | (M + nX)n+ + Y− → (M + (n − 1)X)(n − 1)+ YX | |

| 1.5 | Cation exchange | (M + 2X)2+ + YL2− → (M + Y)+ + 2XL | |

| 1.6 | Anion transfer | (M + nX)n+ + YZ− → (M + nX + Z)(n − 1)+ + Y | |

| 1.7 | Anion attachment | (M + nX)n+ + Y− → (M + nX + Y)(n − 1)+ | |

| 1.8 | Charge inversion | (Y + nH)n+ + (M − H)− → (Y + (n − 2)H)(n − 2)+ + (M + H)+ | |

| Multiply charged anions/singly charged anions | 1.9 | proton transfer | (M − nH)n− + YH+ → (M − (n − 1)H)(n − 1)− + Y |

| 1.10 | Cation attachment | (M − nH)n− + Y+ → (M − nH + Y)(n − 1)− | |

| 1.11 | Charge inversion | (Y − nH)n− + (M + H)+ → (Y − (n − 2)H)(n − 2)− + (M − H)− | |

| Multiply charged cations/multiply charged anions | 1.12 | proton transfer | (M + nH)n+ + (Y − mH)m− → (M + (n − p)H)(n − p)+ + (Y − (m − p)H)(m − p)− |

| 1.13 | Complex formation | (M + nH)n+ (Y − mH)m− → (M + Y + (n − m)H)(n − m)+ |

A. Single proton transfer

Single proton transfer (Table 1, Reactions 1.1, 1.9, and 1.12) reactions were initially carried out in front-end Y-tube reactors and have been more recently and routinely performed in electrodynamic ion traps. Proton transfer from a multiply protonated analyte cation (acid) to a singly charged reagent anion (base) results in the formation of a charge-reduced cation and the neutralized base (Table 1, Reaction 1.1). Proton transfer involving multiply charged analyte anions (bases) and singly protonated reagent cations (acids) proceeds in a similar fashion (Table 1, Reaction 1.9). As it is not analyzed or detected, any fragmentation of the neutral product following the proton transfer event is indeterminable. Despite the exothermicity of the reaction, fragmentation of the charge-reduced analyte is rarely observed, but occurs in some cases. Fragmentation associated with the protonation of multiply charged anions is far more common than fragmentation associated with deprotonation of multiply charged cations. Factors expected to play roles in leading to fragmentation include reaction exothermicity, partitioning of this exothermicity between the reaction partners, the stability of the product ion with respect to fragmentation, the number of degrees of freedom of the product ion, and the rate of excess energy removal from the product ion by collisional and radiative cooling. In general, fragmentation of product ions following proton transfer, if it occurs, is most likely to be observed in reactions involving relatively small ions.41 The reason why fragmentation following protonation of anions is more common than deprotonation of cations may be due to differences in energy partitioning, but differences in ion stabilities precludes firm conclusions. Proton transfer also readily occurs between gas-phase reactions of multiply protonated and multiply deprotonated ions. The extent of proton transfer is highly dependent on the charge states, with incomplete proton transfer typically occuring along with complex formation (vide supra).36 The extent of proton transfer tends to increase with the total charge of the reactants and competes with complex formation. Applications utilizing these three types of proton transfer reactions are relatively mature and numerous..

1. Biopolymer mixture analysis

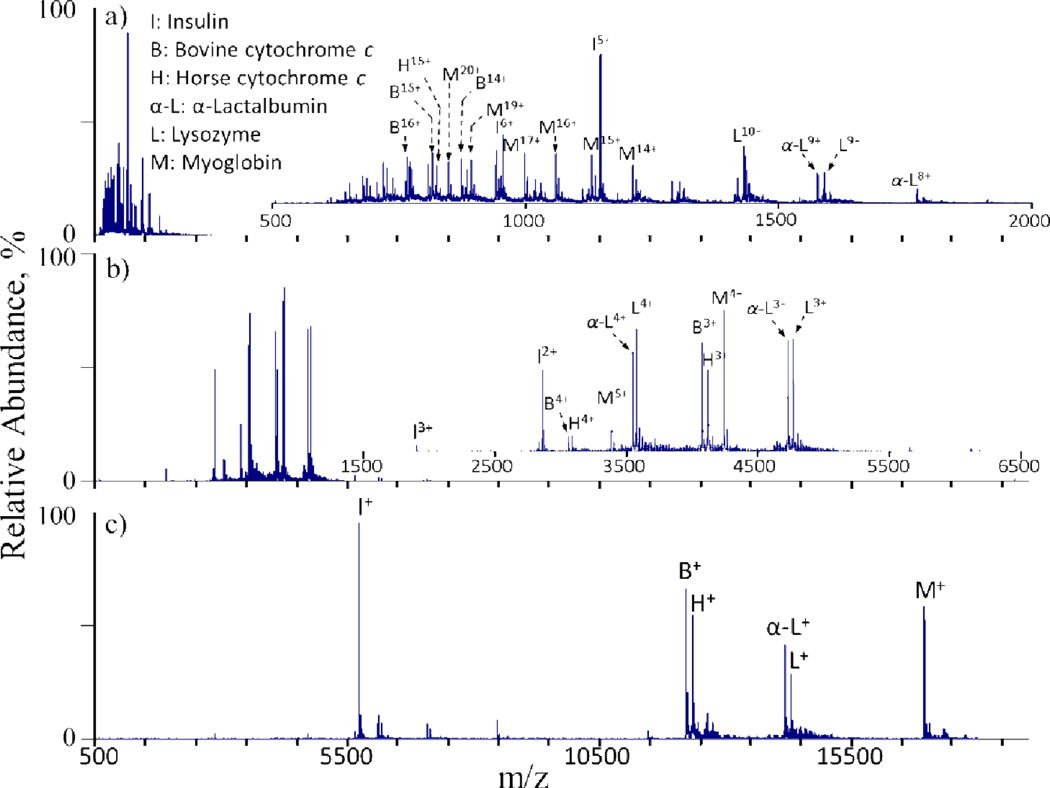

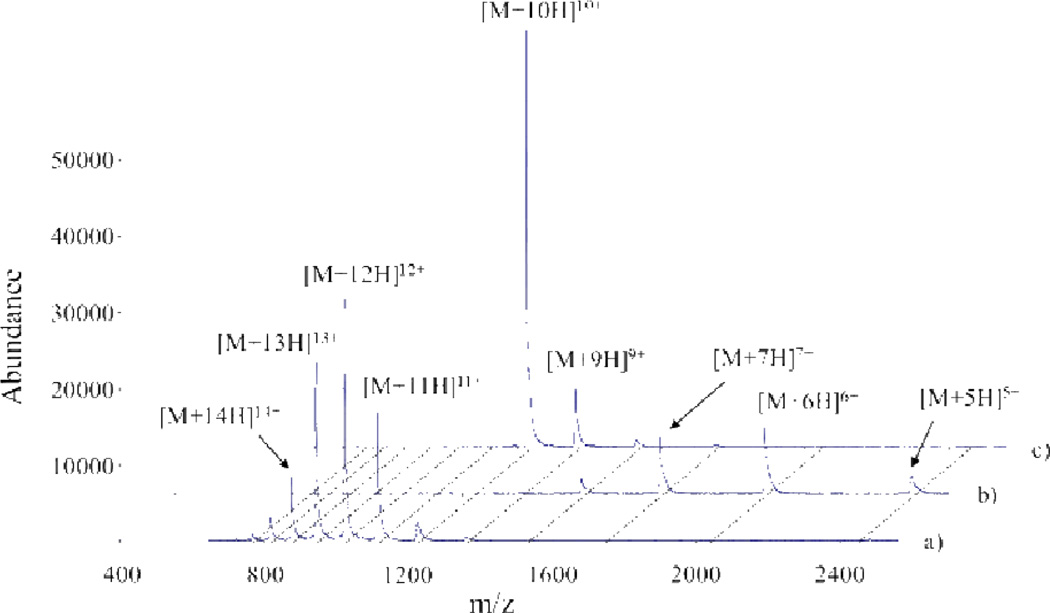

Proton transfer reactions have proven particularly useful for altering the charge states of ions initially produced from an ESI source. This allows for the access of low charge states that may not be directly provided by the ionization source and can prove useful in numerous situations. For example, proton transfer reactions can be used to simplify the electrospray mass spectra of protein mixtures (Fig. 5).10,16,42,43,44 As the reaction kinetics follow a charge-squared dependence, a single ion/ion reaction period can be used to reduce all of the mixture components to predominantly singly charged ions, regardless of their initial individual charge states. In effect, this converts an ESI spectrum into one that more resembles that obtained using matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI). Charge reducing mixtures in this fashion provides several benefits, including the simplification of mass spectra. In a mixture comprised of numerous components, such as the mixture of six proteins shown in Fig. 5, for example, the complexity of the mass spectrum associated with overlapping charge state distributions is eliminated via charge state reduction, thereby facilitating accurate peak assignments.

Fig. 5.

Mass spectra of an equimolar six-component protein mixture (a) prior to and (b) after a parallel parking (vide infra) ion/ion reaction period and (c) after an ion/ion reaction period sufficient to reduce charges largely to +1.Perfluoro-1-octanol (PFO) anions were used as proton transfer reagents and ~100–200 ms reaction times were used in b and c. Reprinted with permission from ref. 29. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

In order to perform ion/ion reactions in an electrodynamic ion trap, both ion populations must be efficiently and simultaneously contained within the device based on experimental operating conditions.45 As discrepancies in m/z between the charge-reduced analyte (which is shifted to higher m/z) and the population of reagent ions (which is usually at a fixed m/z) become greater, mutual storage of the two populations becomes increasingly difficult. The pseudopotential trapping well depth of an ion, which is an important factor in determining the storage efficiency of the ion, is dependent upon the ion trap operating conditions and by the ion m/z. For a given set of operating conditions, the trapping well becomes increasingly shallow as the ion m/z increases. Eventually, a point may be reached where the trapping conditions are insufficient to adequately contain the high mass ions and they are lost. One way to mitigate this issue takes advantage of the electric field between ions of opposing polarities. Provided a sufficient number of low mass reagent ions are present in the ion trap to create the necessary electric field, the trap can simultaneously store high mass ions of the opposite polarity that would not normally be contained based on the strength of the pseudopotential trapping well alone. This “trapping by proxy” approach has been used to perform charge reduction of a poladenylate oligonucleotide mixture using O2+•, though in theory this technique could also prove useful for peptide and protein analytes.46

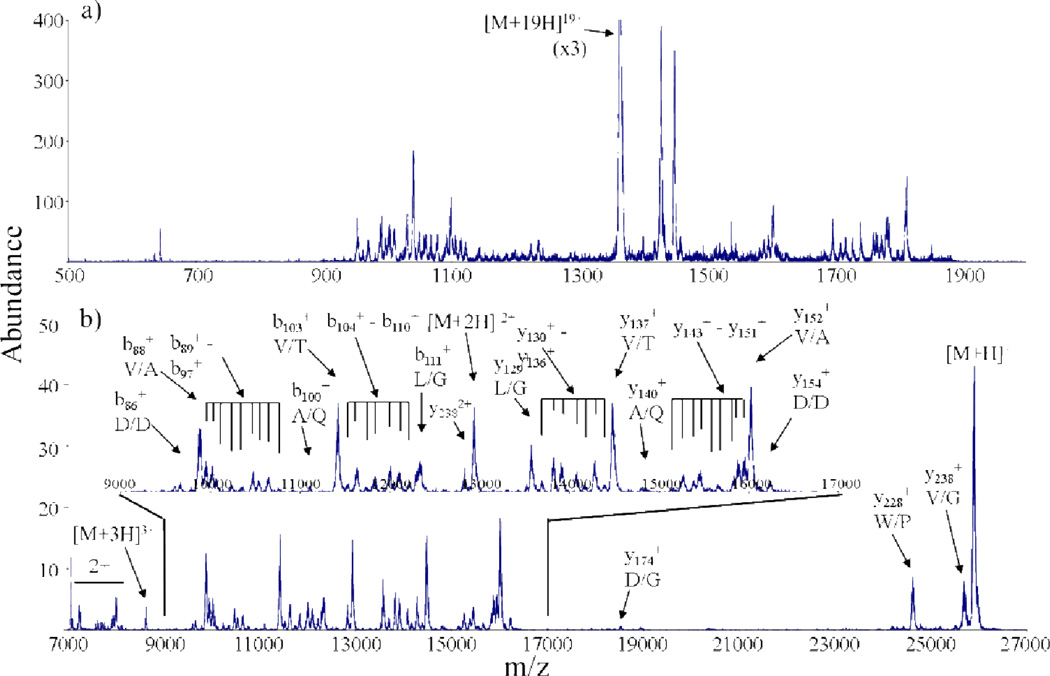

2. MSn: product ion mixture analysis

The fragmentation of multiply charged precursor ions, e.g., by collision induced dissociation (CID), can lead to a complex mixture of products of different masses and charges. This mixture can be more difficult to deal with than mixtures of intact biopolymers because product ions are often not represented as a distribution of charge states, unlike intact precursor ions. In order to derive sequence information, it is necessary to know the product ion charge. Ion/ion proton transfer reactions can be useful for this purpose by converting all product ions largely to the +1 or −1 charge states.47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56 The application of proton transfer reactions to complex mixtures of product ions separates ions that differ in mass and charge but have overlapping m/z values and allows for the confident determination of mass by removing charge ambiguity. This, in effect, renders interpretable a product ion spectrum that might otherwise provide little sequence information. An example is provided in Figure 6, which summarizes a ion trap tandem mass spectrometry experiment for the the CID of the +19 charge state of porcine elastase.48 Prior to proton transfer, the CID of the +19 charge state of porcine elastase is not readily interpretable (Fig. 6a). However, charge reduction of the fragment ions using perfluro-1,3-dimethylcyclohexane (PDCH) anions simplifies and decongests the spectrum (Fig. 6b). Ion/ion proton transfer here reduces the required resolution for peak assignment and facilitates proper fragment ion identification.

Fig. 6.

CID product ion spectra of the +19 charge state of porcine elastase (a) prior to and (b) after proton transfer ion/ion reactoins. Perfluoro-1,3-dimethylcyclohexane (PDCH) anions were used as proton transfer reagents and a 300 ms reaction time was used in b.Reprinted with permission from ref. 48. Copyright 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

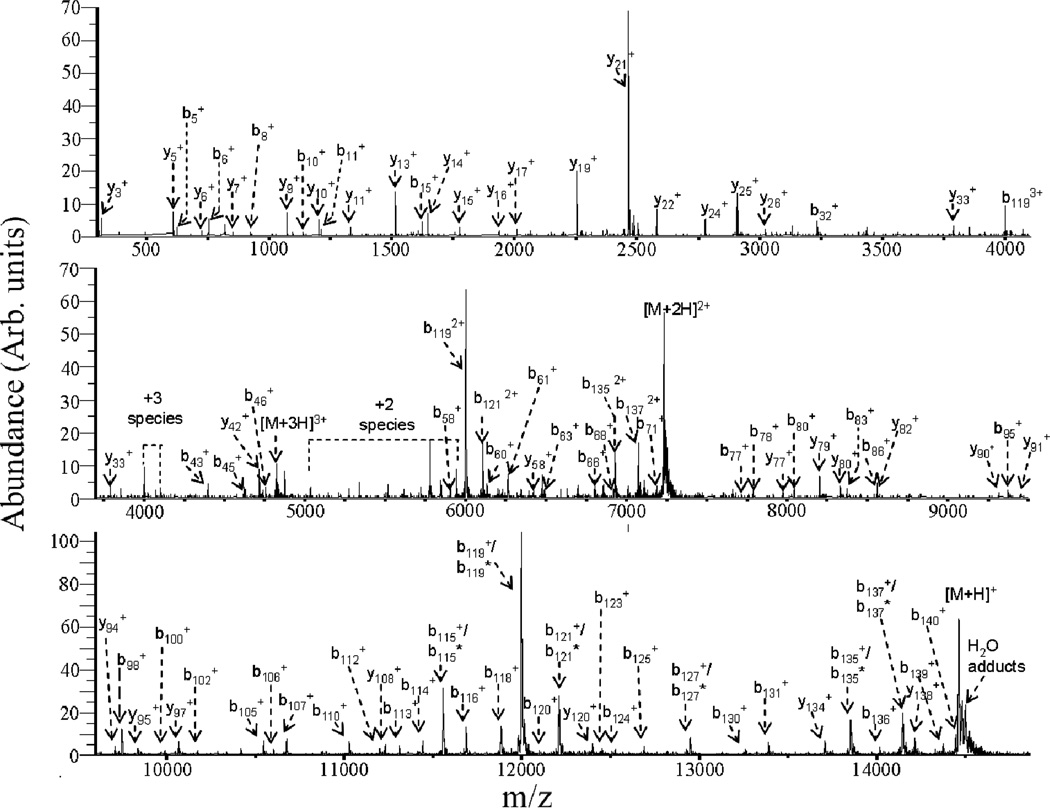

3. MSn: precursor ion manipulation

The mixture analysis applications just described involve reducing analyte ions mainly to singly charged species. It is sometimes desirable to effect less extensive charge reduction. Proton transfer ion/ion reactions can also be used to manipulate precursor ion charge state, which is an important variable in generating primary sequence information of peptide and protein ions via tandem mass spectrometry.12,47,48,57,58,59 The most informative charge states, however, may not be those most readily generated by ESI. While charge state manipulation can be carried out to a limited degree by altering solution conditions60,61,62 or via ion/molecule reaction chemistry,63,64,65,66 ion/ion reactions have proved to be the most flexible means for manipulating precursor ion charge states. An example is provided by α-synuclein, a 14.5 kDa protein that is a major component of the Lewy bodies associated with Parkinson’s disease. Under low energy beam-type collisional activation conditions, the 9+ charge state was found to yield CID products from roughly 85% of the amide linkages in the protein (see Fig. 7).59 Higher charge states of α-synuclein generated significantly less sequence information under CID conditions (see Fig. 8a). However, a short ion/ion reaction period can generate a high abundance of the 9+ charge state (see Fig. 8b) for subsequent activation, which was carried out for the experiment illustrated in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Post-ion/ion reaction product ion spectrum generated from ion trap CID of the [M+9H]9+ ion of α-synuclein. PFO anions were used as proton transfer reagents and a 200 ms reaction time was utilized. Reprinted from ref. 59, “Charge state dependent fragmentation of gaseous α-synuclein cations via ion trap and beam-type collisional activation,” Copyright 2009, with permission from Elsevier.

Fig. 8.

(a) Pre-ion/ion reaction nano-ESI spectrum of α-synuclein. (b) Post-transmission mode ion/ion reaction (using PDCH anions) mass spectrum of α-synuclein using a high amplitude supplementary AC signal applied to an opposing pair of ion trap electrodes to inhibit reactions of the lower charge states. Reprinted from ref. 59, “Charge state dependent fragmentation of gaseous α-synuclein cations via ion trap and beam-type collisional activation,” Copyright 2009, with permission from Elsevier.

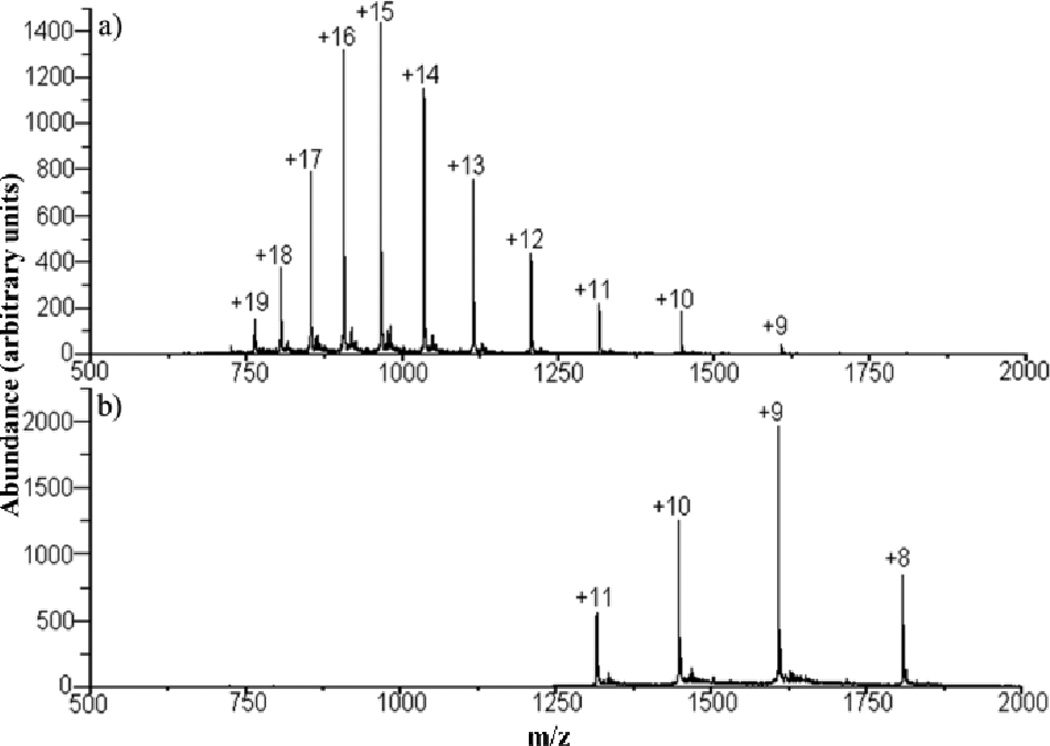

When ion/ion reactions are conducted in an electrodynamic ion trap, it is possible to inhibit the reactions of particular ions via selective ion acceleration techniques, which can be used to provide a high degree of control over the extent of an ion/ion reaction. This is enabled by the fact that stored ions have m/z-dependent frequencies of motion. “Ion parking,” as it has been termed, occurs via the selective inhibition of an ion/ion reaction rate at a desired charge state.67 This is effected by applying a dipolar excitation voltage in resonance with the secular frequency of the ion charge state of interest during the bipolar storage reaction period. As the charge reduction reactions proceed, analyte ions fall into resonance with this excitation voltage and are prevented from further reactions with reagent ions, thereby concentrating all of the ion current into a single charge state (Fig. 9). This can provide for the gas-phase purification of protein charge states and of protein mixtures. “Parallel parking” techniques can also be used to selectively inhibit the proton transfer rates of a small window of analyte m/z,68,69,70 as was used in the experiment illustrated in Figure 8. In addition to concentrating analyte ion signal initially dispersed among many charge states into a single charge state, ion parking can be used to “charge-state-purify” an ion population using a second ion parking step. This has been demonstrated in a top-down MS/MS study of proteins derived from a whole lysate fraction from E. coli.71 An initial parking step was used to concentrate ions into a narrow band of m/z values. All proteins with charge states that can lead to the selected m/z window were accumulated in the first parking step. A second parking step which was tuned for one charge state lower of a selected mass allowed for the removal of contaminating charge states because only a protein with the mass of interest would lead to the charge-reduced m/z selected in the second parking step. The process effectively provided means for the gas-phase concentration and purification of a protein of interest.

Fig. 9.

Mass spectra of cytochrome c acquired in (a) pre ion/ion, (b) post ion/ion, and (c) ion parking modes. PDCH anions were used as proton transfer reagents and a 150 ms reaction time was used in b and c. Reprinted with permission from ref. 67. Copyright 2002 American Chemical Society.

B. Multiple proton transfer in a single ion/ion reaction: charge inversion

Sequential proton transfer reactions of the type just described are readily observed at high reagent concentrations and/or long reaction times. A unique type of multiple ion transfer is highlighted in this section that involves the transfer of two or more protons in a single ion/ion reaction encounter. Special emphasis is placed here on reactions that invert the charge of an analyte ion,72,73 as such a result cannot be achieved readily via sequential ion/ion reactions (i.e., once the analyte is neutralized, the likelihood that it will be reionized by another collision with a reagent ion is extremely small). While single proton transfer reactions can occur via the fly-by or “hopping” mechanism (vide supra), charge inversion reactions are most likely to proceed through a long-lived intermediate complex. The likelihood for such a sticky collision as well as the charge partitioning upon breakup of the complex both determine the efficiency of charge inversion. For example, the relative proton affinities of the relevant analyte and reagent species will largely determine which products from the breakup of the complex will carry the charge. Hence, the identity of the charge inversion reagent plays a role in the degree of selectivity associated with the charge inversion reaction.74,75 Applications of charge inversion reactions are emphasized here.

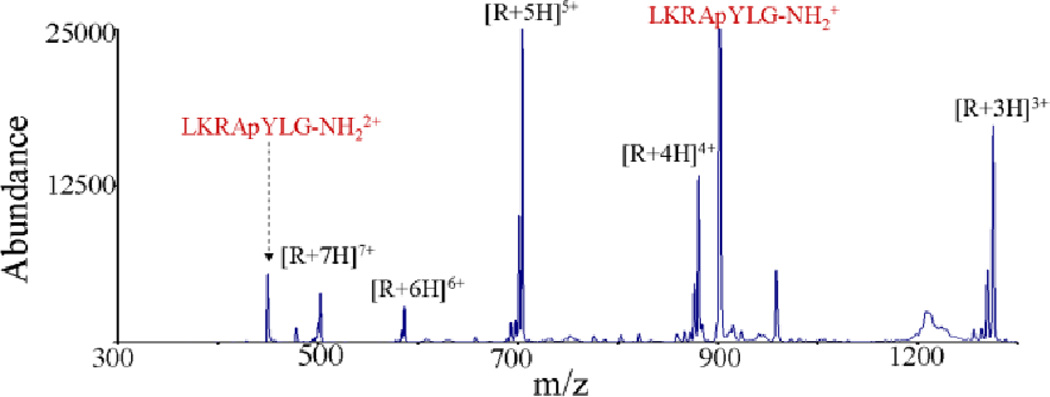

In many cases, the ion type generated in the ionization process is not necessarily well-suited for a given structural characterization approach [e.g., CID, electron transfer dissociation (ETD), etc.]. Ion/ion reactions in general, and specifically charge inversion here, provide means for altering the ion type after the ionization step but prior to a characterization step. For example, acidic phosphopeptides tend not to ionize efficiently in the positive polarity, and CID of these analytes typically results in uninformative neutral losses (e.g., losses of phosphoric acid, water, and ammonia). Negative ETD (NETD), while potentially useful, is much less popular than its counterpart, cation ETD, which has been shown effective in phosphopeptide sequencing experiments. Charge inversion can provide for the transformation of a singly deprotonated phosphopeptide to a doubly protonated phosphopeptide via an ion/ion reaction with multiply protonated DAB-g4 dendrimers (Fig. 10).76 These dicationic products provide sequence informative CID fragments and are amenable to ETD interrogation, which allows for identification of the phosphorylation site.

Fig. 10.

Ion/ion charge inversion reaction of LKRApYLG-NH2 monoanions with DAB-g4 dendrimer cations. Reprinted with permission from ref. 76. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

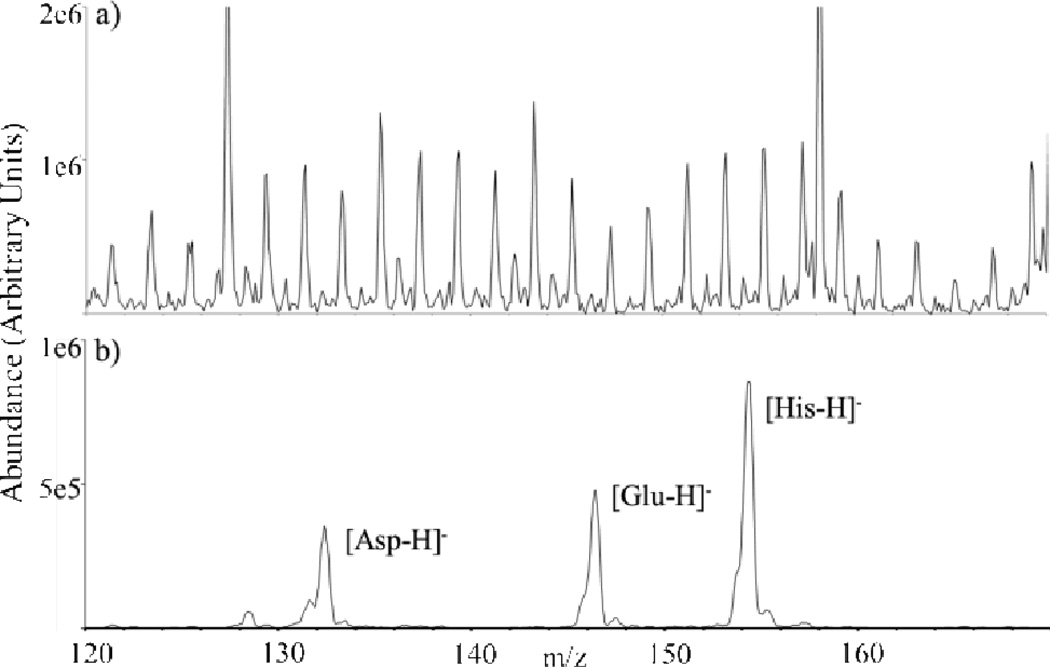

Charge inversion has also been used to concentrate multiple cation types (e.g., [M+Na]+, [M−H+2Na]+, [M−2H+3Na]+) into a single analyte anion type (e.g., [M−H]−)77 and to reduce chemical noise in a complex mixture of amino acids in precipitated blood plasma,78 both of which greatly simplified spectral interpretation. The latter application, in particular, represents a case in which chemical noise in the mass spectrum represents a complicating factor in observing the targeted amino acids. The charge inversion process, however, is relatively efficient for the amphoteric amino acid analytes whereas most of the ions comprising the chemical noise are neutralized by the charge inversion reagent (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

(a) Positive ion nESI mass spectrum of a mixture of amino acids present in a solution of precipitated plasma, and (b) negative ion mass spectrum after charge inversion using anions generated from nESI of PAMAM generation 3.5. Reprinted with permission from ref. 78. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

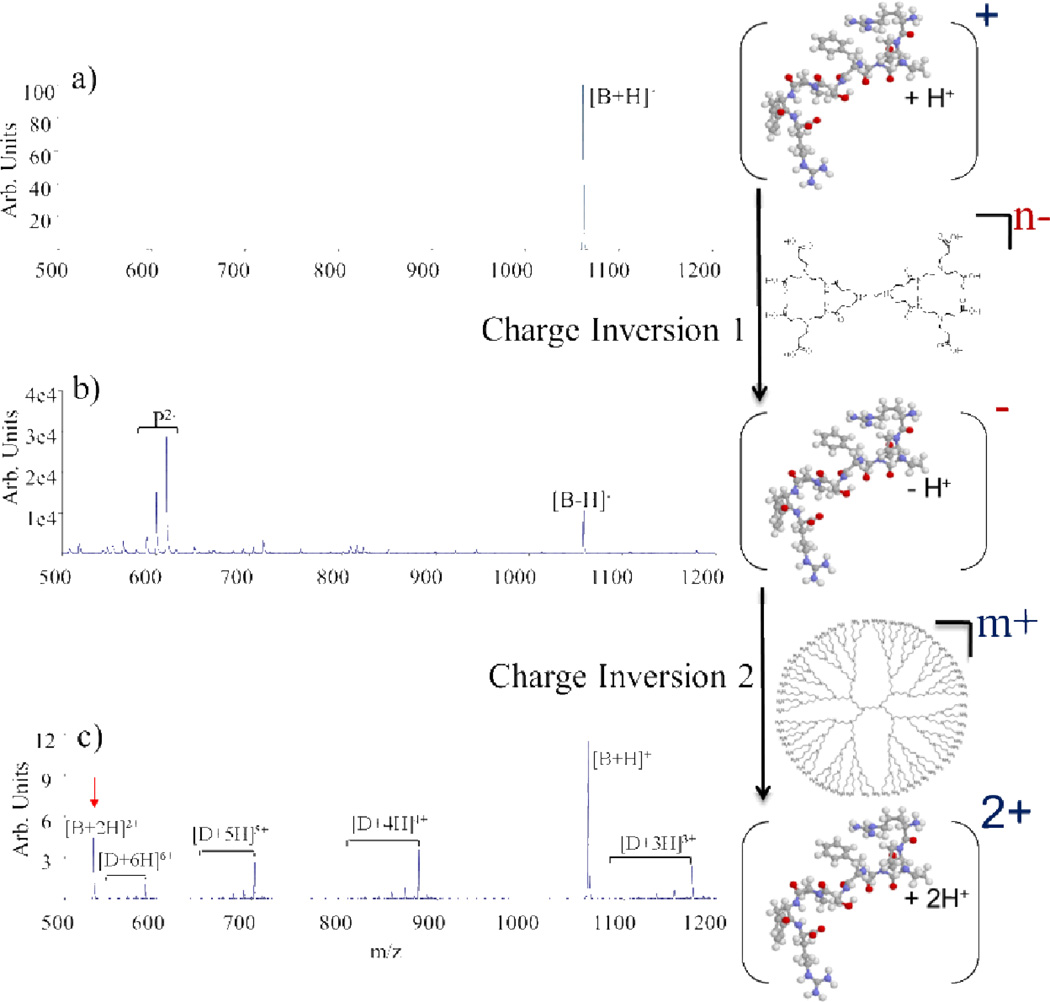

The single proton transfer reactions described above are highly effective in reducing the charge states of ions initially generated via ESI. There are applications for which increasing precursor ion charge is desirable, particularly with ionization methods such as MALDI that tend to generate singly charged ions. Increasing the charge states of ions via a single ion/ion reaction, however, is highly unfavorable for thermodynamic and kinetic reasons. However, two sequential ion/ion charge inversion reactions afford the opportunity to increase the absolute charge state of an ion. In the case of a singly protonated molecule, for example, the following sequence of two charge inversion reactions can be used to increase the ion charge:

| (6) |

| (7) |

This has been deomonstrated using the polypeptide bradykinin (Fig. 12).79 Charge inversion of the monocation per equation 6 with PAMAM dendrimer anions (Fig. 12b) followed by charge inversion per equation 7 with DAB dendrimer cations generates doubly protonated bradykinin (Fig. 12c). The net result is an increase in charge from +1 to +2. Analogous results have been obtained in the negative polarity, increasing the absolute charge from −1 to −2.80

Fig. 12.

(a) 1+ bradykinin (b) charge inverted to 1- using PAMAM dendrimer anions and then (c) charge inverted back to the positive polarity using DAB dendrimer cations. The result is a net increase in charge of the peptide from the +1 to the +2 charge state. Reprinted with permission from ref. 79. Copyright 2003 American Chemical Society.

C. Other ion transfer

While proton transfer is, by far, the most commonly observed ion transfer ion/ion reaction, other ion transfer reactions have been explored as well. These types of reactions include mechanisms of ion attachment (Table 1, Reactions 1.7 and 1.10), ion transfer (Table 1, Reactions 1.4 and 1.6), and ion exchange (Table 1, Reaction 1.5). Early experiments of this kind concerned, for example, the anionic attachment of iodide to cationic peptides,81 the anionic transfer of fluoride to cationic peptides,82 the cationic attachment of iron83 and rhenate84 to peptides, controlled cationic transfer of sodium between peptides and anionic reagents,85,86 and metal cation exchange involving cationic peptides and a metal/ligand anion.87 These types of reactions can be used to change the charge state of the analyte ion as well as to alter the nature of the charge-bearing particle, both of which can affect ionic properties significant to peptide and protein analysis (e.g. dissociation pathways in CID experiments).88 Additionally, the iodide anion attachment experiment led to a similar experiment in which the sites of protonation on protein cations where identified via ion/molecule attachment reactions with HI.81

Metal ion transfer reactions have recently shown promise in the context of some mass spectrometry sequencing experiments. The incorporation of alkali metals into peptides via gas-phase ion/ion reactions has been shown to provide complementary sequence information upon CID compared to that provided by the protonated analogues, results similar to those obtained in solution incorporation experiments.85 The gas-phase experiment allows the ion type to be selected independent of any initial solution conditions (e.g., preparation of metallated peptides in solution via addition of alkali salts can compromise ionization efficiency). Similar experiments have also been described using transition metal complexes.84,89,90 Additionally, it has been shown that metal ion transfer can offer a degree of selectivity in the bond cleavage of polypeptides91 and proteins.92 The incorporation of gold cations into multiply protonated insulin cations, for example, has resulted in selective disulfide bond cleavage upon CID. The gas-phase selectivity exihibited by transition metal cationization, in conjunction with the ability to incorporate metal cations in the gas-phase, promises to provide a complementary approach in the structural characterization of peptide and protein analytes.

D. Complex formation

All ion/ion reactions that involve a ‘sticky’ collision (i.e., in which the two partners come into intimate contact) generate a complex, the lifetime of which is determined by a number of factors. In many cases, as with the charge inversion results described above, the complex itself may not survive long enough to be detected in the product spectrum. In other cases, generation of a complex may be the dominant process. Subsequent activation of the complex often leads to proton transfer, which implies that proton transfer can occur both via the hopping mechanism, under appropriate conditions, and via a long-lived complex. Complex formation has been observed extensively in reactions between multiply charged cations and multiply charged anions (Table 1, Reaction 1.13).36,93,94 Typically, formation of a complex competes with varying extents of proton transfer during ion/ion encounters. Complex formation reactions can be used to generate gas-phase protein complexes, such as those formed by reacting the +15 and −6 charge states of cytochrome c.36 Complex formation is highly dependent on structural and chemical properties of the ions, effects that are particularly important for the observation of more complex reactions that lead to covalent bond formation, as discussed further below.

V. Redox chemistry

Electron transfer ion/ion reactions have been used extensively in recent years for their utility in the structural characterization of bio-ions. Depending on the nature of the reactants, electron transfer can compete with proton transfer39,95 as a means for mutual neutralization in an ion/ion reaction. Results based on Landau-Zener theory suggest that both the electron affinity of the reagent and the Franck-Condon overlap of the anion and its corresponding neutral must be optimized39 to maximize the probability for electron transfer to a multiply protonated analyte. Electron transfer reactions have been noted to occur in both polarity combinations, viz.:

| (8) |

| (9) |

though electron transfer from anions to multiply charged cations is by far the more common application. While not always the case, electron transfer ion/ion reactions in mass spectrometry are typically discussed in the context of dissociation experiments [i.e., electron transfer dissociation (ETD)22 or negative ETD (NETD),96,97 as the case may be]. As discussed below, redox-induced fragmentation has proven particularly useful at providing primary sequence information for peptides and proteins. When dissociation does not occur spontaneously as a result of an electron transfer, fragmentation of the radical product is often induced using energetic collisions (e.g., ETcaD)98,99,100,101 or by photon irradiation (AI-ETD).102 Since the emergence of electron transfer dissociation techniques, numerous reviews describing in detail the factors and mechanisms influencing electron transfer dissociation as well as its current and potential applications have been published.12,103,104,105,106 Only a brief overview of the two main classes of electron transfer (ETD and NETD) are provided here.

A. Electron transfer dissociation

Electron transfer from anions to multiply charged cations (equation 8) has been noted to induce spontaneous dissociation, a process termed ETD. Reagents for this purpose are typically some form of polycyclic aromatic radical monoanion. ETD has been shown to generate c- and z•-type fragment ions from peptide and protein cations, complementary to the b- and y-type fragments typically generated with activation techniques such as CID and infared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD). This type of fragmentation, reported earlier in electron capture dissociation (ECD) experiments,107,108,109,110 corresponds to cleavage at the N-Cα bond of the peptide backbone and, especially when combined with the complementary sequence information provided by CID, can be extremely powerful in peptide and protein sequencing studies. ETD has also shown the ability to preserve labile post translational modifications such as glycosylation, 111 sulfonation,112 methylation,113 and phosphorylation,114,115,116,117 while showing selectivity towards cleavage of disulfide linkages.118 The unique characteristics of ETD (and ECD) are particularly attractive in the field of proteomics, leading to the implementation of ETD workflows in various search algorithms119,120 and on various instrument platforms.121,122

In addition to the importance of the reagent noted previously, the structure and identity of the analyte can also greatly influence the efficiency of the initial electron transfer and the effectiveness of subsequent dissociation. Peptide and protein charge state,123 size,12 and composition124,125 can significantly influence these figures of merit. For example, ETD sequence coverage has been noted to increase with increasing precursor ion charge state and decrease with increasing precursor size at a fixed charge state. Additionally, the presence of radical stabilizing groups on the analyte can prevent the charge-reduced product from undergoing fragmentation.126 In some of these instances, activation of the charge-reduced product, sometimes referred to as the “ET no D” product ion, can provide rich sequence information. In any case, while CID remains the default dissociation method in mass spectrometry, due to its ease of implementation and successful sequencing applications, ETD is quickly developing into a powerful complementary tool.

B. Negative electron transfer dissociation

Electron transfer from cations to multiply charged anions (equation 9) though less common with peptide and protein applications, has also been shown to be a useful method for sequence determination.97,127,128 The lesser use of NETD is not due to a lack of effectiveness; rather, it is most likely due to the positive polarity paradigm that currently dominates in most proteomics workflows. However, the success of NETD in oligonucleotide sequencing41,129,130,131 as well as in limited proteomics applications indicates that it can be another useful sequencing tool. NETD reagent cations have ranged from rare gas cations to transition metals to polycyclic aromatics and have been noted to induce a•- and x-type fragmentation [cleavage of the Cα-C(O) bond] through abstraction of an electron from the analyte anion of interest. Examples of NETD applications include its successful use in phosphopeptide sequencing,132 cleavage of disulfide bonds in insulin anions,83 and the high-throughput analysis of an acidic proteome.127

VI. Covalent chemistry

The reactions discussed above involve charged particle transfers and, in some cases, non-covalent interactions. However, within the past few years, a new category of gas-phase ion/ion reactions has emerged that involves the formation of covalent bonds. Solution phase derivitization techniques are routinely employed in mass spectrometry for the manipulation of peptides and proteins so as to facilitate analyte ionization,133 quantification,134,135 and characterization.136,137 While initial experiments showed evidence for ion/ion covalent metal coordination chemistry in the gas-phase,83,84,85 targeted functional-group-specific ion/ion reactions based on organic chemistry have only recently emerged. Our group is actively pursuing these gas-phase derivitization techniques as part of MSn workflows that can be used in the characterization of analyte ions, including peptides and proteins. The potential advantages for gas-phase derivatization over solution phase analogues include speed (e.g., an ion/ion reaction can be driven to completion in on the order of 100 milliseconds under favorable conditions), ready comparison of modified and unmodified analyte forms, a high degree of control over the reactant identities as each can be mass-selected, the ability to control the number of modifications via reaction time and/or the identities of reagents, the avoidance of generating highly complex reaction mixtures in solution which may compromise ionization, etc. In the early part of this research program, emphasis has been placed on determining the characteristics of the reagent that lead to efficient reactions and on specific linkage chemistries. These findings are key to the development of novel applications of gas-phase derivatization workflows.

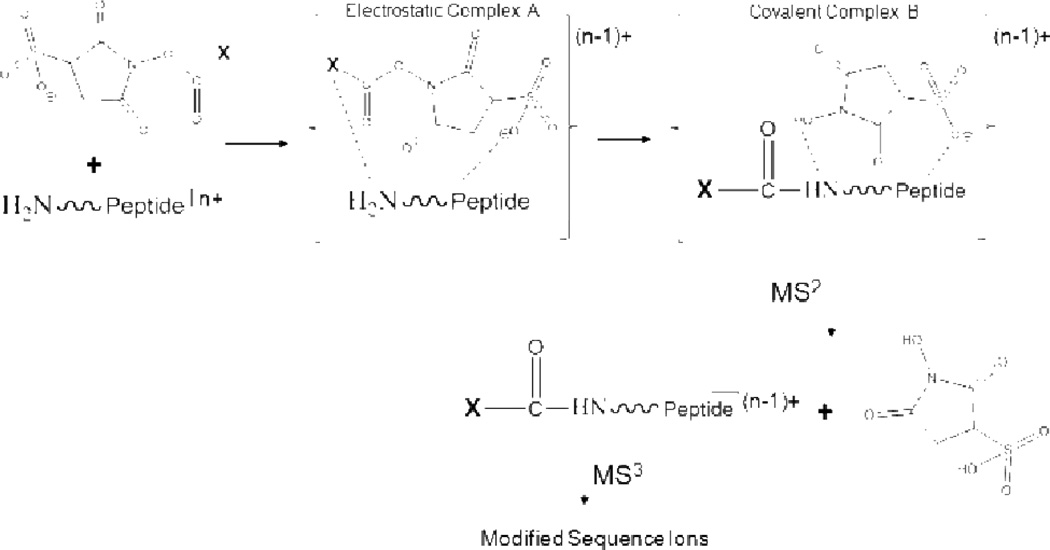

A. The multi-functional reagent

Gas-phase ion/ion reactions have been shown to proceed through a stable, Coulombically-bound orbit.36 Such an orbit is the ion/ion analog to a high-lying Rydberg state associated with an ion/electron interaction. As the orbit collapses due to collisions and/or tidal effects, the reactants can approach sufficiently close for chemistry to occur. Either small charged particle transfer at a crossing point or an intimate collision to form a relatively long-lived chemical complex can occur. A generalized scheme depicting this situation is provided in Scheme 1. Reactions that involve both bond-making and bond-breaking are inherently slower (i.e., less favored entropically) than simple electron or proton transfer and therefore require the formation of a long-lived complex. For a given analyte ion, the properties of the reagent are key in determining if selective covalent reactions are competitive with simple ion transfer. To date, all reagent ions that have been shown to give rise to covalent bond formation have been at least bifunctional138,139,140 and sometimes trifunctional. Bifunctionality in this context includes a site that engages in a strong electrostatic interaction with the analyte ion, which leads to the formation of a long-lived stable collision complex, and a reactive site that undergoes a chemical reaction with a functional group in the analyte ion. The electrostatically “sticky” site anchors the reagent to the analyte to allow for sufficient time for the reaction to occur. The long lifetime of the complex likely contributes to the high reaction efficiencies often observed due to multiple interactions of the reagent reactive site within a conformationally flexible analyte/reagent complex facilitating the likelihood for assuming a favorable reaction configuration. The long-lived complex leads to an effectively high concentration of reagent per analyte at the molecular level. Typically, sulfonate and fixed charge quaternary ammonium functional groups have been used to promote this long-lived complex formation. In the absence of a sticky site, proton transfer rather than covalent bond formation has dominated the product ion spectrum, even when the reagent has the necessary reactive group. The functional groups used to provide a strong non-covalent interaction are more or less ‘universal’ in that sulfonate groups tend to interact strongly with all peptide and protein cations and fixed charge groups, such as quaternary ammonium groups, form strong electrostatic interactions with peptide and protein anions. In addition to the necessary reactive and sticky sites on the reagent, a corresponding reactive site must also be available on the analyte for the covalent chemistry to proceed. The remainder of the discussion emphasizes the reactive groups on the reagent and analyte that engage in specific bioconjugation chemistries.141

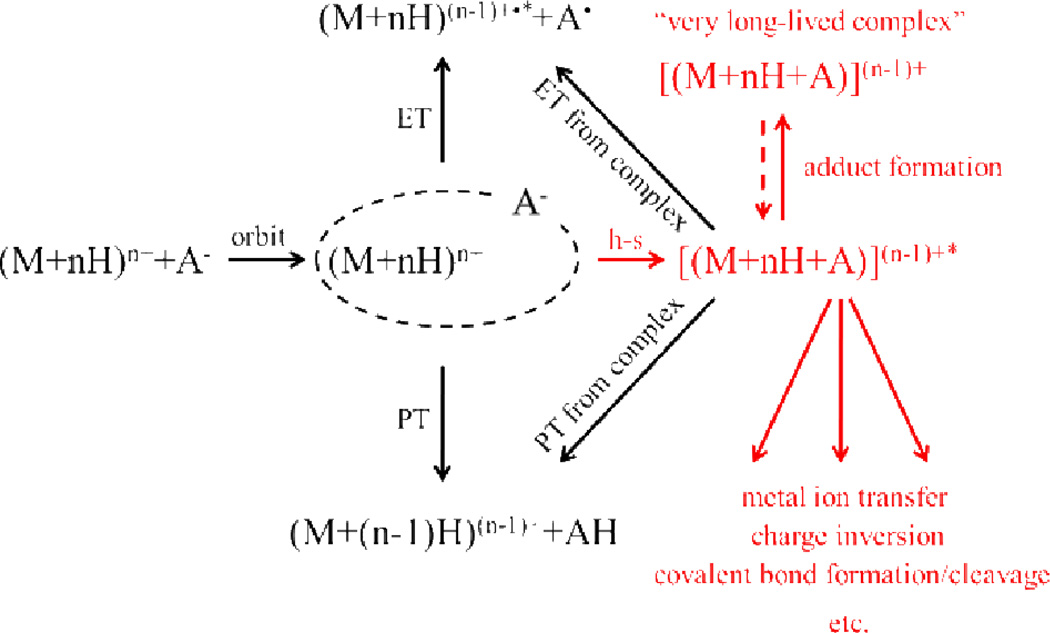

Scheme 1.

Generic ion/ion reaction kinetic scheme. Reprinted with permission from ref. 40. Copyright 2010 IM Publications.

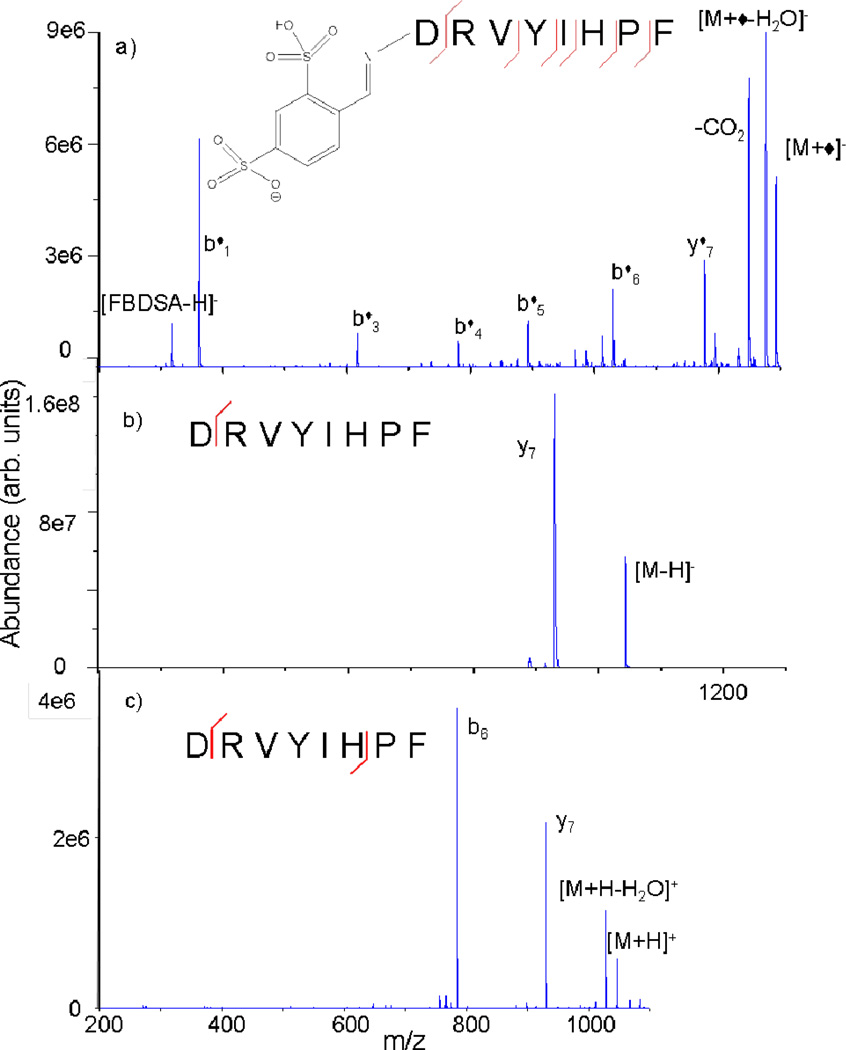

B. Formyl-benzenesulfonic acids

Gas-phase site-specific covalent ion/ion reactions were first demonstrated using a 4-formyl-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid (FBDSA) monoanion reagent and doubly protonated peptide analyte (experiments using the monosulfonic acid derivative, FBMSA, have also been successfully performed).138 Upon ionization, one of the sulfonic acid groups on FBDSA is deprotonated and can strongly interact with a protonated site on the peptide, which serves to anchor FBDSA to the analyte (Scheme 2). In the absence of a sulfonate group (e.g., substituting carboxylic acid groups for the sulfonic acid groups), no complex formation with the peptide occurs and proton transfer dominates the product ion spectrum. Following formation of the charge-reduced complex, the aldehyde group of FBDSA can undergo nucleophilic attach by an unprotonated primary amine on the peptide chain (e.g., the N-terminus or an ε-amino group of a lysine side chain).

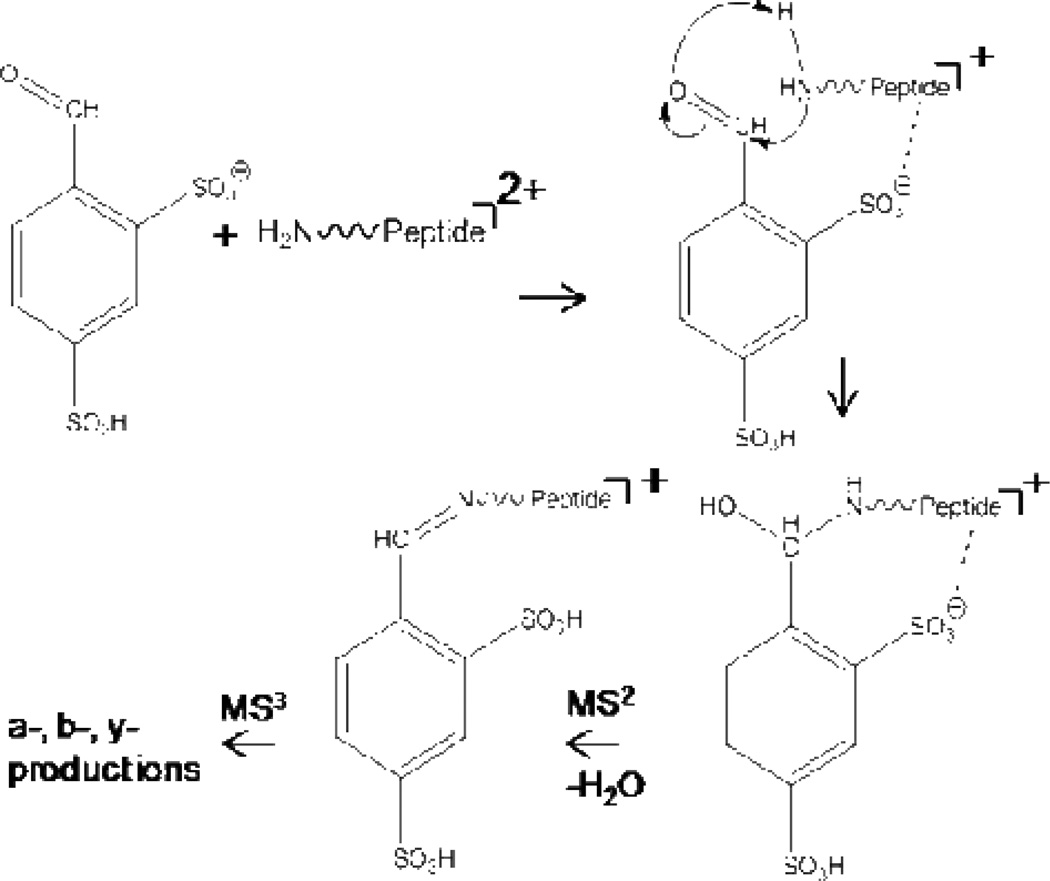

Scheme 2.

Ion/ion reaction scheme for Schiff base formation between a FBDSA monoanion and a peptide dication. Reprinted with permission from ref. 138. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

Collisional activation of the complex results in dehydration, suggesting the formation of an imine bond consistent with Schiff base formation, with the resulting covalent adduct typically denoted as ◆:

| (10) |

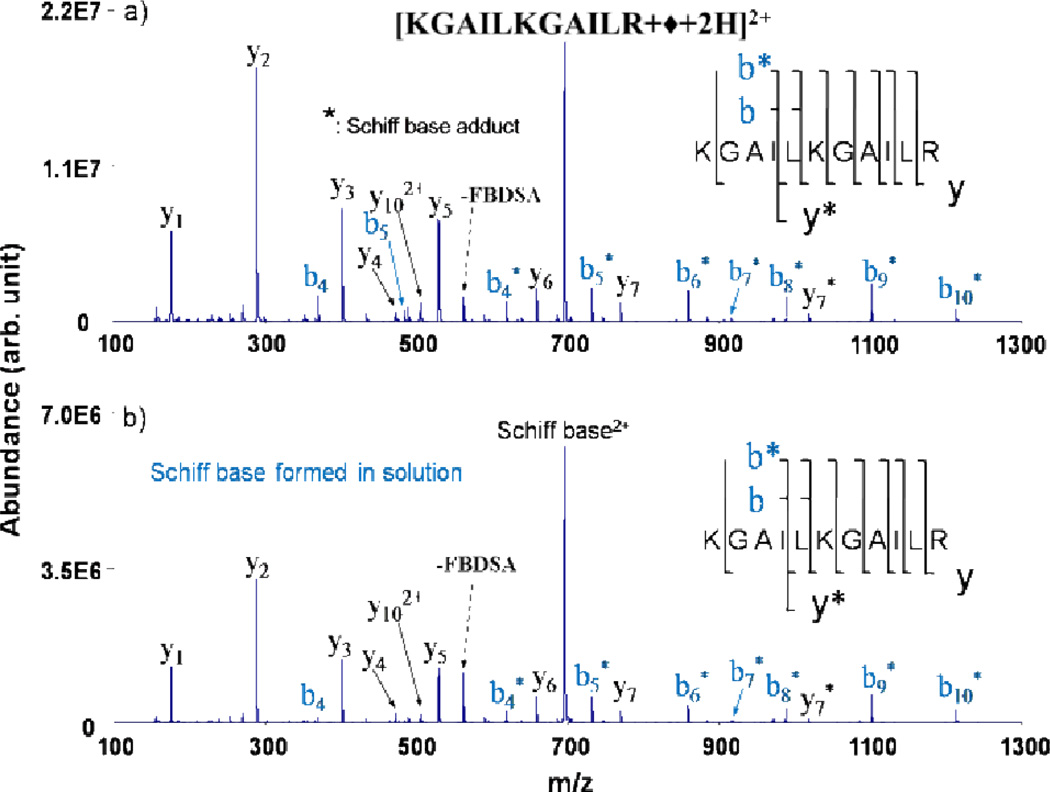

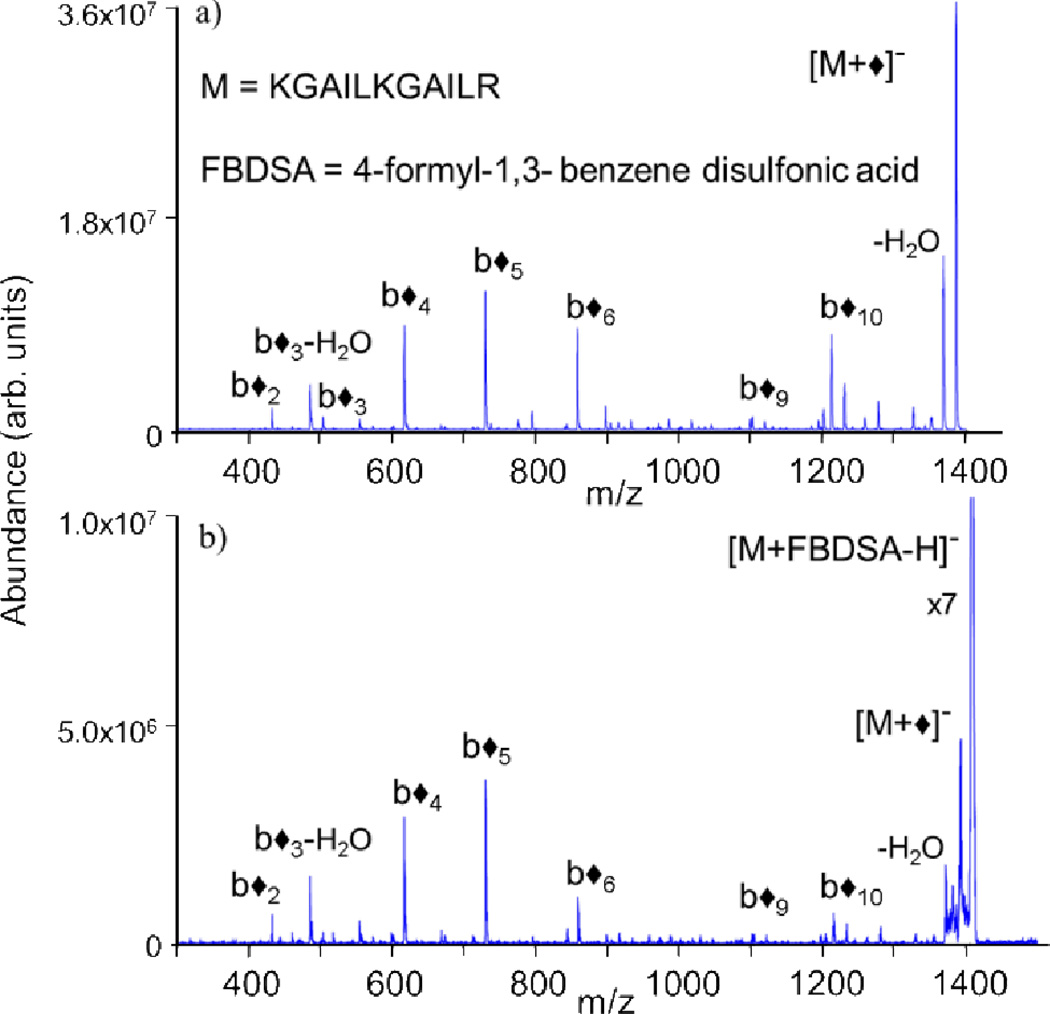

This is analagous to Schiff base reactivity previously observed with ion/molecule derivatization reactions.142,143 The loss of water represents a signature for covalent imine bond formation. However, as water losses from peptide and protein biopolymers are quite common in collisional activation experiments, the loss of 18 Da is not a definitively diagnostic ion for a chemical reaction. MS/MS performed on the dehydrated ion can be used to confirm b- and y-type fragment ions consistent with covalent modification at primary amine sites, results quite similar to MS/MS performed on Schiff base products formed in the solution phase (Fig. 13). Here, singly deprotonated FBDSA has been reacted with multiply protonated peptides to generate modified species with one less positive charge. Additionally, doubly deprotonated FBDSA has been reacted with singly protonated peptides to generate charge-inverted modified peptide ions (Fig. 14)144 via the process:

| (11) |

Fig. 13.

CID of Schiff base-modified +2 charge state of KGAILKGAILR produced (a) via gas phase ion/ion reactions and (b) in solution. Asterisks (*) indicate ions containing the Schiff base modification. Reprinted with permission from ref. 138. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

Fig. 14.

CID of Schiff base-modified −1 charge state of KGAILKGAILR produced (a) via charge inversion ion/ion reactions from a +1 charge state precursor and (b) in solution. Diamonds (◆) indicate ions containing the Schiff base modification. Reprinted with permission from ref. 144. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

Schiff base modifications have been shown to be quite useful in providing primary sequence information of biopolymers. CID of a Schiff base-modified ion can give enhanced and/or complementary sequence information when compared to the corresponding unmodified ion alone, as in the case of angiotensin II (Fig. 15).144 CID of the unmodified peptide is dominated by the well-established C-terminal aspartic acid and N-terminal proline cleavages (Fig. 15b and 15c). However, CID of the covalently modified peptide generates much more extensive sequence information (Fig. 15a). Similarly, Schiff base modification has been used to enhance the sequence coverage of tryptic peptides and disulfide-linked peptides.145 In addition to covalent bond formation, some peptides have also shown the ability to maintain strong electrostatic interactions with FBDSA, resulting in the observation of FBDSA adducts on peptide fragment ions in cases where modification is not necessarily expected.146 For example, this has been observed to occur when C-terminal arginine residues are present, resulting in stable non-covalent modification of the peptide. Those results indicated that the binding strength might be tuned as desired by appropriately selecting the reagent anion (e.g., two sulfonate groups versus one sulfonate and one carboxylate group) as well as the analyte cation (e.g., methyl esterification of the C-terminus resulted in reduced electrostatic attachment to the C-terminal arginine).

Fig. 15.

CID product ion spectra of (a) [M+◆]−, (b) [M−H]−, and (c) [M+H]+ of angiotensin II. Diamonds (◆) indicate ions containing the Schiff base modification. Reprinted with permission from ref. 144. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

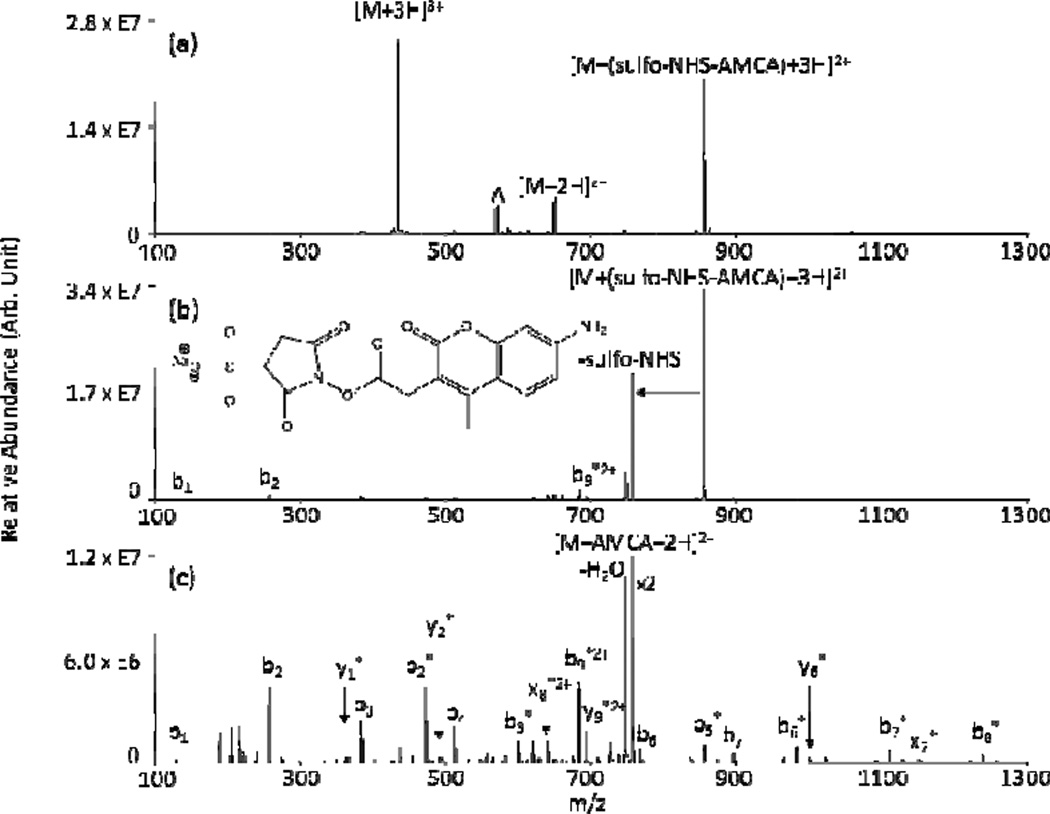

C. N-hydroxysuccinimide esters

Perhaps the most common amine-reactive derivatization reagents utilized today are N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters. These reagents have found extensive use in the solution phase in studies examining the relative reactivities of primary amine groups of native and denatured proteins,147,148 peptide and protein cross-linking,149,150,151 the covalent anchoring of peptides onto solid supports,152 and the attachment of chromophores to peptides so as to facilitate photoactivation experiments.153 As such, many different types of NHS esters are commercially available. In addition to being performed in solution in an offline fashion, this type of chemistry has also recently been shown to occur in reactive desorption electrospray ionization (DESI), allowing rapid bioconjugation during the ionization process.154,155,156,157,158 The targeted nature of this (and all bioconjugation) chemistry can allow site-specific information to be obtained about the peptide or protein of interest. Extending the well-established NHS reactivity to the gas-phase enables gas-phase derivatization approaches that are analogous to those already developed in solution.

Gas-phase NHS ester reactivity has shown useful applicability in two general areas: covalent tagging139,159 and cross-linking. 159,160 Covalent tagging via ion/ion reactions has been demonstrated on both multiply protonated and multiply deprotonated analytes. With cationic analytes, the NHS ester reagent is a sulfo-NHS ester. The sulfonate group carries the negative charge and aids in the formation of the long-lived complex necessary for covalent chemistry to proceed (Scheme 3). With anionic analytes, the NHS ester “X” group has been a fixed charge 4-trimethylammonium butyrate (TMAB-NHS). Nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the NHS ester by an unprotonated primary amine on the peptide results in loss of either neutral NHS or neutral sulfo-NHS upon collisional activation. These losses represent signatures for amide bond formation between the peptide and the reagent, resulting in tagging the peptide with the residual X group from the reagent. Fig. 16 shows an example in which the peptide KKKKKKKKKK has been tagged with the blue fluorescent dye aminomethylcoumarin acetate (AMCA) via an ion/ion reaction using a sulfo-NHS-AMCA anionic reagent. As with FBDSA, the absence of unprotonated primary amines on the analyte (e.g., doubly protonated YGGFLK), leads to no reactivity, resulting in a neutral loss of the entire reagent rather than covalent bond formation via rearrangment and concomitant signature neutral loss.139 In the case of the sulfo-NHS reagents, the group covalently attached to the peptide (e.g., the chromophore AMCA, in the case of Fig. 16) is easily varied by swapping the X groups on the reagent. This flexibility in labeling primary amine groups of peptides is being explored further as means to tune reactivity and activation/fragmentation channels for peptides or proteins of interest.

Scheme 3.

Ion/ion reaction scheme for covalent amide bond formation between a sulfo-NHS based monoanion and a multiply protonated peptide. Reprinted with permission from ref. 139. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

Fig. 16.

Product ion spectra from (a) an ion/ion reaction between [KKKKKKKKKK+3H]3+ and [(sulfo-NHS-AMCA)-Na]−, (b) CID of [KKKKKKKKKK+(sulfo-NHS-AMCA)+3H]2+, and (c) CID of [KKKKKKKKKK+AMCA+2H]2+. Asterisks (*) indicates ions covalently tagged with AMCA and deltas (Δ) indicates ions from the precursor ion isolation. Reprinted with permission from ref. 139. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

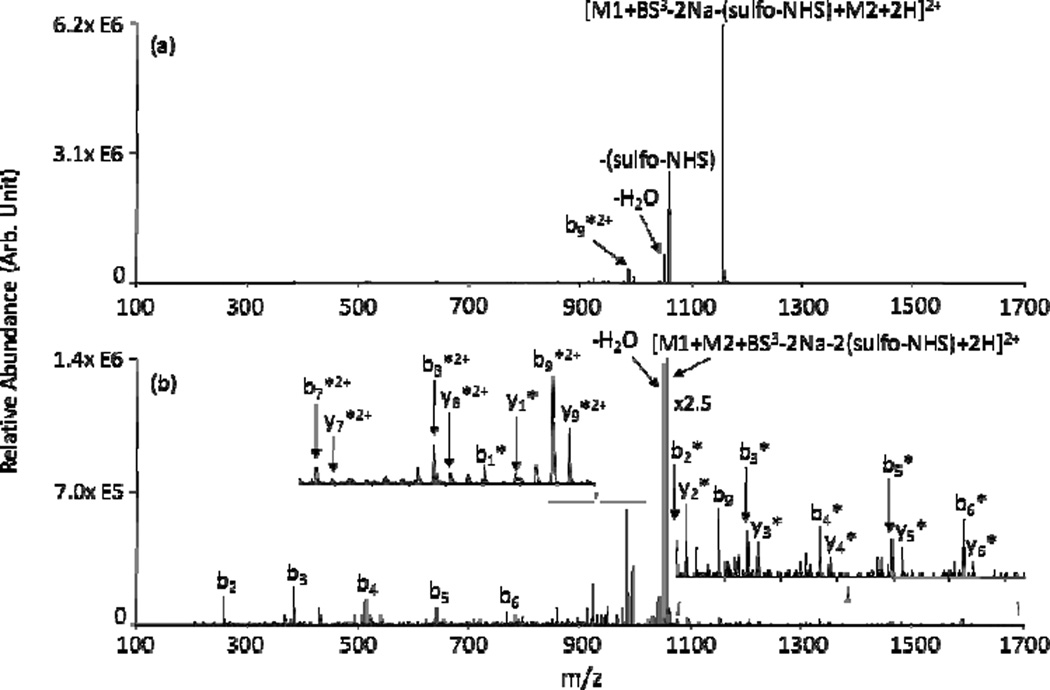

The use of homo-bifunctional sulfo-NHS reagents, i.e., two sulfo-NHS groups spaced by a linker arm, can be used to perform covalent chemistry in the context of a charge inversion experiment, similar to those performed using FBDSA. The homo-bifunctional sulfo-NHS reagent contains two sulfonate groups that can be utilized to charge invert singly charged peptide and protein cations. A novel application of these homo-bifunctional sulfo-NHS reagents is the gas-phase cross-linking of polypeptide ions. In this case, loss of two neutral sulfo-NHS molecules from the ion/ion complex signifies the formation of two amide bonds, resulting in a cross-linked product. NHS- and sulfo-NHS-based cross-linking techniques are well-established solution phase methods for the modification and conjugation of biomolecules and are becoming increasingly popular in experiments designed to map the tertiary (viz. 3-dimensional) structure of proteins. Ion/ion reactions producing inter- and intra-molecular cross linking of polypeptides have been performed, resulting in the gasphase synthesis of covalently bound peptide complexes [e.g., using bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3) to inter-molecularly link peptides YGGFLK and KKKKKKKKKK, as shown in Fig. 17].157 In solution phase protein mapping experiments, reactive sites are probed by attaching cross-linkers of varying spacer arm lengths to the proteins. MS/MS of the derivitized proteins can reveal the sites of cross-linker attachment, allowing for the determination of distances between reactive sites and mapping of 3-D protein structure.161,162 Much like in solution, initial studies show that mapping of tertiary protein structure can also be performed in the gas-phase via ion/ion reactions.163 However, the gas-phase studies can be sensitive to ionic properties such as protein charge state. That is, protonated primary amines are unreactive, a situation which is more pervasive throughout the protein as the charge state increases (however, it has been noted that as protein charge state increases, proteins tend to adopt more unfolded conformations so as to better distribute charge density, which could expose previously buried unprotonated primary amines and make them available for reaction).

Fig. 17.

Product ion spectra from CID of (a) [YGGFLK+KKKKKKKKKK+BS3-2Na-(sulfo-NHS)+2H]2+ and (b) [YGGFLK+KKKKKKKKKK+BS3-2Na-2(sulfo-NHS)+2H]2+. M1 and M2 represent YGGFLK and KKKKKKKKKK, respectively. Asterisks (*) indicate b- and y-type ions from M2 cross-linked with the entire M1. Reprinted from ref. 160 [original source “Figure 6: Product ion spectra derived from (a) ion trap CID of [YGGFLK + KKKKKKKKKK + BS3 – 2Na-(sulfo-NHS) + 2H]2+ and (b) MS3 of [YGGFLK + KKKKKKKKKK + BS3 – 2Na-2(sulfo-NHS) + 2H]2+. *Ions intermolecularly cross-linked with BS3”], Copyright 2011 American Society for Mass Spectrometry, with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media.

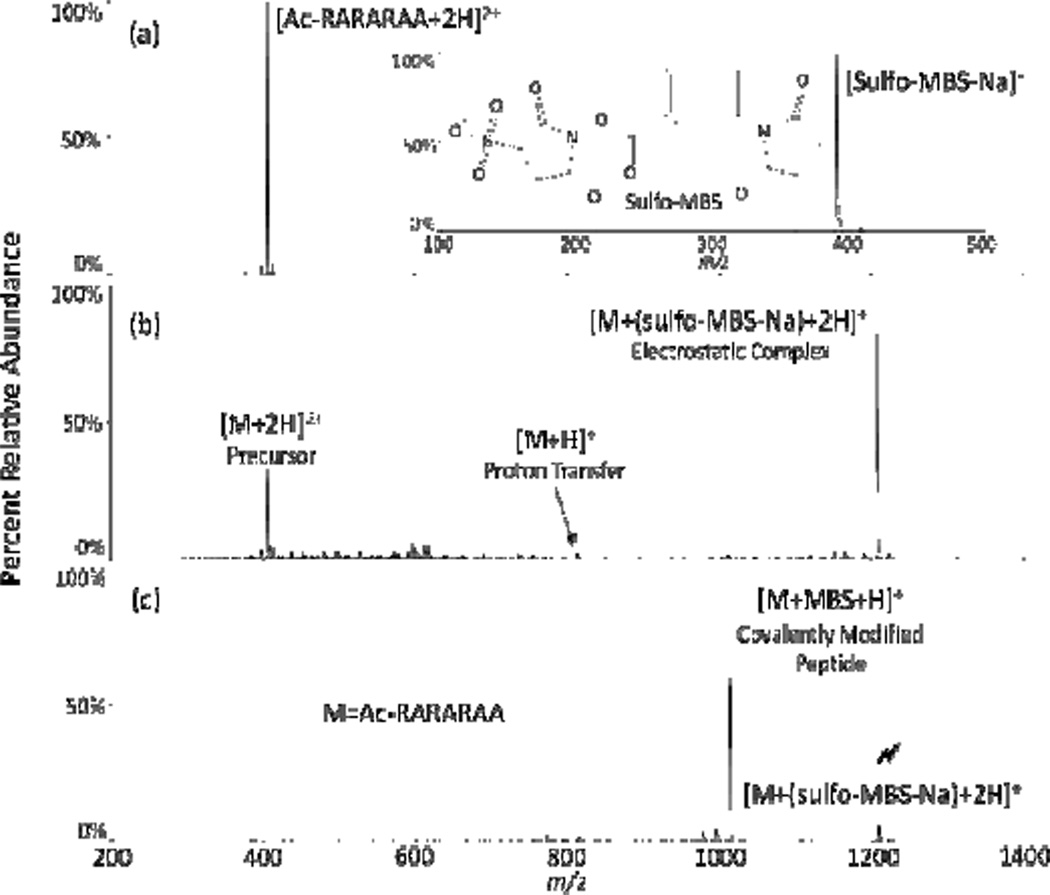

While much of the ion/ion covalent chemistry noted to date mirrors reactivity in the condensed-phase, significant differences have also been noted. For example, the neutral arginine side chain has been shown to be highly reactive towards NHS esters through both charge reduction and charge inversion ion/ion reaction pathways (Fig. 18).164 In this study, the doubly protonated, N-terminally acetylated peptide RARARAA was reacted with m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide ester (sulfo-MBS). Following formation of an ion/ion chemical complex, subsequent CID resulted in signature loss of neutral sulfo-NHS, indicating covalent modification. Similar to the primary amine reactivity noted previously, the highly basic guanidino group of the arginine side chain initiates a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the reagent ester, resulting in the same signature loss of a neutral sulfo-NHS molecule. This observation stands in contrast to behavior in the condensed-phase where arginine amino acids are unreactive towards NHS-esters. This inert behavior is due to their high pKa values in solution (>12), which results in arginine protonation under normal solution conditions, rendering them poor nucleophiles and, as a result, unreactive in many bioconjugation experiments. The solution pH at which arginine would be unprotonated readily hydrolyzes the ester functionality of the NHS reagent, also disrupting the covalent chemistry. However, in the gas-phase, depending on the amino acid composition and charge state of the polypeptide, arginine residues need not be protonated and thereby represent possible reactive sites for NHS-ester chemistry.

Fig. 18.

(a) Isolated precursor ions and (b) product ion spectrum from the ion/ion reaction between [ac-RARARAA+2H]2+ and [(sulfo-MBS)-Na]− and (c) product ion spectrum from CID of [YGGFLK+(sulfo-NHSAMCA)+ 2H]+. The lightning bolt ( ) indicates the ion subjected to CID. Reprinted with permission from ref. 164. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

) indicates the ion subjected to CID. Reprinted with permission from ref. 164. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

D. Carbodiimides

Gas-phase selective covalent reactivity has also been demonstrated for carboxylic acid groups using carbodiimide reagents.140 N-cyclohexyl-N′-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide (CMC) is a fixed charge quaternary ammonium-containing reagent commonly used in solution phase cross-linking experiments. CMC has seen extensive use in solution phase peptide synthesis165 and amino acid quantitation experiments.166 The fixed charge ammonium group serves to anchor the reagent to a multiply deprotonated analyte via a strong electrostatic interaction. In solution, carbodiimides react with carboxylic acid groups to form reactive o-acylisourea intermediates. These intermediates then typically undergo facile nucleophilic attack by a primary amine in the vicinity167 or by hydrolysis that regenerates a carboxylate168 (though the reactive acylisourea intermediate can be stabilized by converting it to a sulfo-NHS ester169). However, in the gas-phase, where there is no water or primary amine, a stable ion/ion complex can be observed. Subequent activation of a peptide/CMC ion/ion complex results in an cyclohexyl isocyanate neutral loss (125 Da) from one side of the carbodiimide functionality, a signature for this covalent amide bond formation. In the absence of a reactive carbodiimide group on the reagent [i.e., when CMC is oxidized to N-cyclohexyl-N′-(2-morpholinoethyl)urea, CMU], the covalent chemistry does not occur and no signature loss is observed. This study extends further the development of site-specific gas-phase covalent ion/ion bioconjugation reactions to carboxylic acid functionalities.

VII. Conclusions

Ion/ion reactions represent flexible means for aiding in the gasphase analysis of peptides and proteins by mass spectrometry. The reactions enable a wide variety of chemical transformations in the gas-phase that can facilitate peptide/protein mixture analysis and identification/characterization. Useful applications include simplifying ESI spectra of complex mixtures of multiply charged ions and product ion spectra derived from multiply charged precursors, manipulating the ion type generated by the ionization method to provide for the observation of enhanced or complementary structural information via tandem mass spectrometry, synthesis of gas-phase complexes, and gasphase derivatization to facilitate structural characterization. In addition to the more well-established acid/base and redox ion/ion reaction classes, site-specific covalent chemical transformations represent a promising new area of gas-phase reactivity that is largely unexplored. Initial experiments demonstrate that such functional-group-specific ion chemistry is indeed possible and potentially useful in the primary and 3-D structural analysis of peptides and proteins. Despite the fact that gas-phase covalent chemistry is still in its infancy and much remains to be understood and explored, the selectivity demonstrated by these types of ion/ion bioconjugation reactions shows promise in targeted characterization approaches of peptide and protein biopolymers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank previous and current group members, collaborators, and colleagues whose work has contributed to the experiments and insights represented in this article. The National Institutes of Health is gratefully acknowledged for its support in our laboratory of the development of ion/ion reactions for biomedically relevant applications (Grant GM 45372). B.M.P. wishes to acknowledge receipt of an American Chemical Society, Division of Analytical Chemistry (ACS DAC) Fellowship sponsored by the Society for Analytical Chemists of Pittsburgh (SACP).

Notes and references

- 1.Thompson JJ, Rutherford E. Philos. Mag. 1896;42:392–407. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutherford E. Philos. Mag. 1897;44:422–440. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahan BH. In: Advances in Chemical Physics. Prigogine I, Rice SA, editors. Vol. 23. New York: Wiley; 1973. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flannery MR. In: Applied Atomic Collision Physics. McDaniel EW, Nighan WL, editors. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 141–172. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates DR. Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Science. 1989;246:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 1990;9:37–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loo RRO, Udseth HR, Smith RD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1992;3:695–705. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(92)87082-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLuckey SA, Stephenson JL., Jr Mass Spectrom. Rev. 1998;17:369–407. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1998)17:6<369::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scalf M, Westphall MS, Krause J, Kaufman SL, Smith LM. Science. 1999;283:194–197. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitteri SJ, McLuckey SA. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2005;24:931–958. doi: 10.1002/mas.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Good DM, Wirtala M, McAlister GC, Coon JJ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:1942–1951. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700073-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia Y, Mcuckey SA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:173–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sohn CH, Chung CK, Yin S, Ramachandran P, Loo JA, Beauchamp JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:544–5459. doi: 10.1021/ja806534r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loo RRO, Udseth HR, Smith RD. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:6412–6415. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scalf M, Westphall MS, Smith LM. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:52–60. doi: 10.1021/ac990878c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Votham VC, Holden D, Brodbelt JS. Proceedings of the 60th Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics; Vancouver; Canada. 2012. WP31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mather RE, Todd JFJ. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Phys. 1980;33:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louris JN, Brodbelt-Lustig JS, Cooks RG, Glish GL, Van Berkel GJ, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Processes. 1990;96:117–137. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells JM, Chrisman PA, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:614–622. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephenson JL, Jr, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Processes. 1997;162:89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syka JEP, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:9528–9533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia Y, Wu J, Londry FA, Hager JW, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Hager JW, Xia Y, Londry FA, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:5006–5015. doi: 10.1021/ac049359m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang X, Hager JW, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:3363–3370. doi: 10.1021/ac062295q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang X, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:882–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emory JF, Hassel KH, Londry FA, McLuckey SA. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2009;23:409–418. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams JP, Brown JM, Campuzano I, Sadler PJ. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:5458–5460. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00358a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia Y, Chrisman PA, Erickson DE, Liu J, Liang X, Londry FA, Yang MJ, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:4146–4154. doi: 10.1021/ac0606296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAlister GC, Phanstiel D, Good DM, Berggren WT, Coon JJ. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:3525–3534. doi: 10.1021/ac070020k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan DA, Hartmer R, Speir JP, Stoermer C, Gumerov D, Easterling ML, Brekenfeld A, Kim T, Laukien F, Park MA. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:271–278. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ledvina AR, Westphall MS, Saba J, Viner R, Coon JJ. Proceedings of the 60th Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics; Vancouver; Canada. 2012. MP06. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephenson JL, Jr, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:7390–7397. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLuckey SA, Stephenson JL, Jr, Asano KG. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:1198–1202. doi: 10.1021/ac9710137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson JJ. Philos. Mag. 1924;47:337–378. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells JM, Chrisman PA, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7238–7249. doi: 10.1021/ja035051l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bates DR, Morgan WL. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990;64:2258–2260. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan WL, Bates DR. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1992;25:5421–5430. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunawardena HP, He M, Chrisman PA, Pitteri SJ, Hogan JM, Hodges BDM, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12627–12639. doi: 10.1021/ja0526057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLuckey SA. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010;16:429–436. doi: 10.1255/ejms.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herron WJ, Goeringer DE, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:11555–11562. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephenson JL, Jr, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:4026–4032. doi: 10.1021/ac9605657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebeling DD, Westphall MS, Scalf M, Smith LM. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:5158–5161. doi: 10.1021/ac000559h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebeling DD, Westphall MS, Scalf M, Smith LM. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:401–405. doi: 10.1002/rcm.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams JD, Cooks RG. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1993;7:380–382. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLuckey SA, Wu J, Bundy JL, Stephenson JL, Jr, Hurst GB. Anal. Chem. 74:976–984. doi: 10.1021/ac011015y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engel BJ, Pan P, Reid GE, Wells JM, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2002;219:171–187. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hogan JM, McLuckey SA. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003;38:245–256. doi: 10.1002/jms.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reid GE, Shang H, Hogan JM, Lee GU, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7353–7362. doi: 10.1021/ja025966k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wells JM, Stephenson JL, Jr, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000;203:A1–A9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cargile BJ, McLuckey SA, Stephenson JL., Jr Anal. Chem. 2001;73:1277–1285. doi: 10.1021/ac000725l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newton KA, Chrisman PA, Reid GE, Wells JM, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001;212:359–376. doi: 10.1002/rcm.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He M, Reid GE, Shang H, Lee GU, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:4653–4661. doi: 10.1021/ac025587+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reid GE, Stephenson JL, Jr, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 74:577–583. doi: 10.1021/ac015618l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hogan JM, Pitteri SJ, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:6509–6516. doi: 10.1021/ac034410s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amunagama R, Hogan JM, Newton KA, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:720–727. doi: 10.1021/ac034900k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reid GE, Wu J, Chrisman PA, Wells JM, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:3274–3281. doi: 10.1021/ac0101095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watson DJ, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006;255–256:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chanthamontri C, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009;283:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muddiman DC, Cheng XH, Udseth HR, Smith RD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1996;7:697–706. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(96)80516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iavarone AT, Jurchen JC, Williams ER. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:1455–1460. doi: 10.1021/ac001251t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lomeli SH, Peng IX, Yin S, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Loo JA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McLuckey SA, Van Berkel GJ, Glish GL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:5668–5670. [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLuckey SA, Glish GL, Van Berkel GJ. Anal. Chem. 1991;63:1971–1978. doi: 10.1021/ac00018a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams ER. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003;31:831–842. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199608)31:8<831::AID-JMS392>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cassidy CJ, Carr SR. J. Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:247–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199603)31:3<247::AID-JMS285>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McLuckey SA, Reid GE, Wells JM. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:336–346. doi: 10.1021/ac0109671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chrisman PA, Pitteri SJ, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:3411–3414. doi: 10.1021/ac0503613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chrisman PA, Pitteri SJ, McLuckey SA. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:310–316. doi: 10.1021/ac0515778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prentice BM, Xu W, Ouyang Z, McLuckey SA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2011;306:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reid GE, Shang H, Hogan JM, Lee GU, McLuckey SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7353–7362. doi: 10.1021/ja025966k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]