1. Introduction

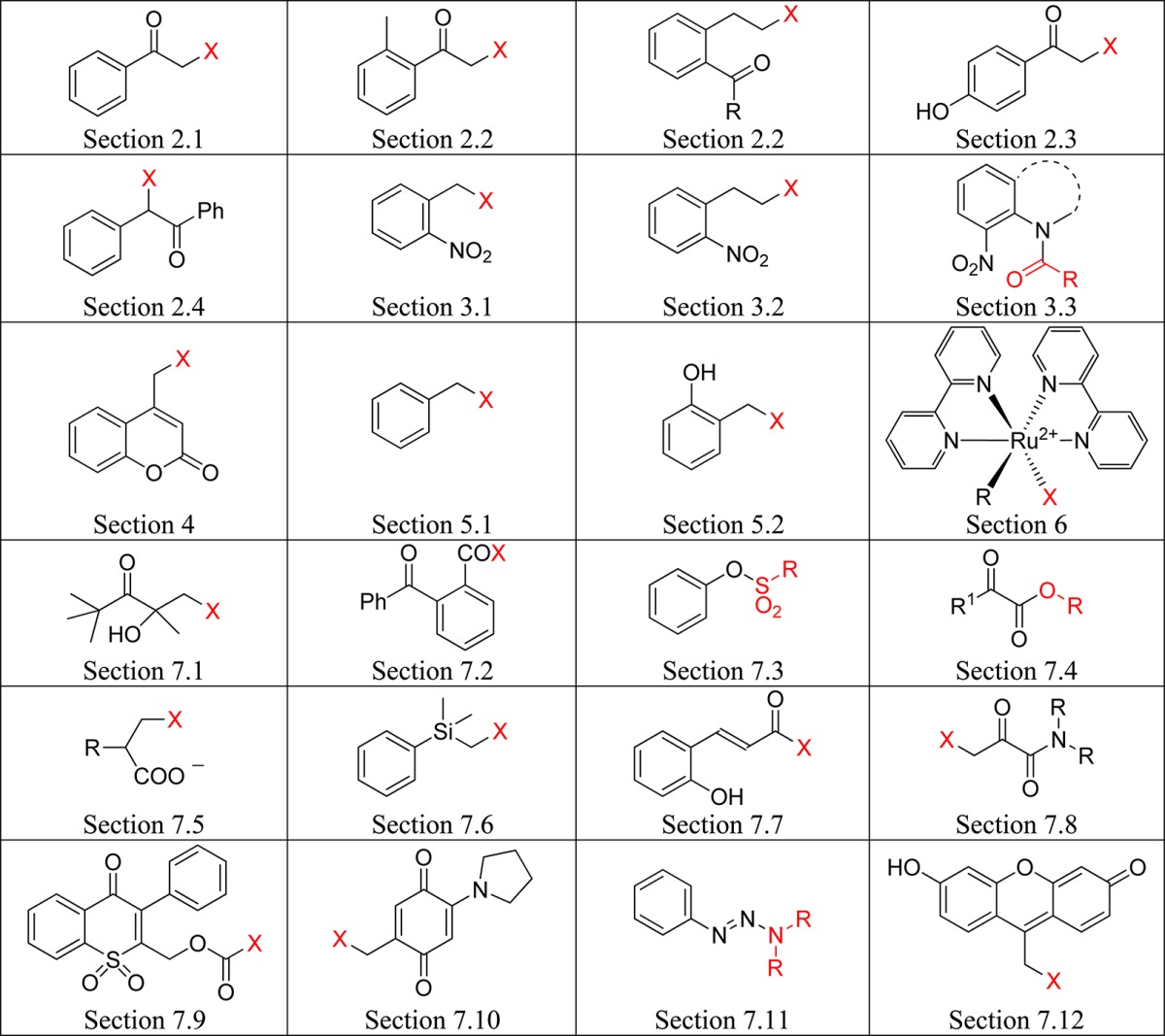

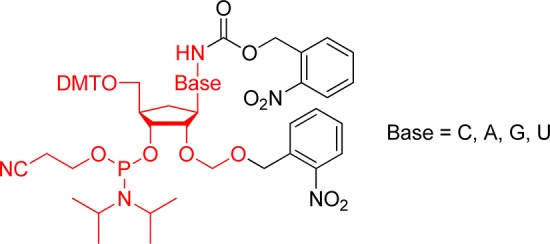

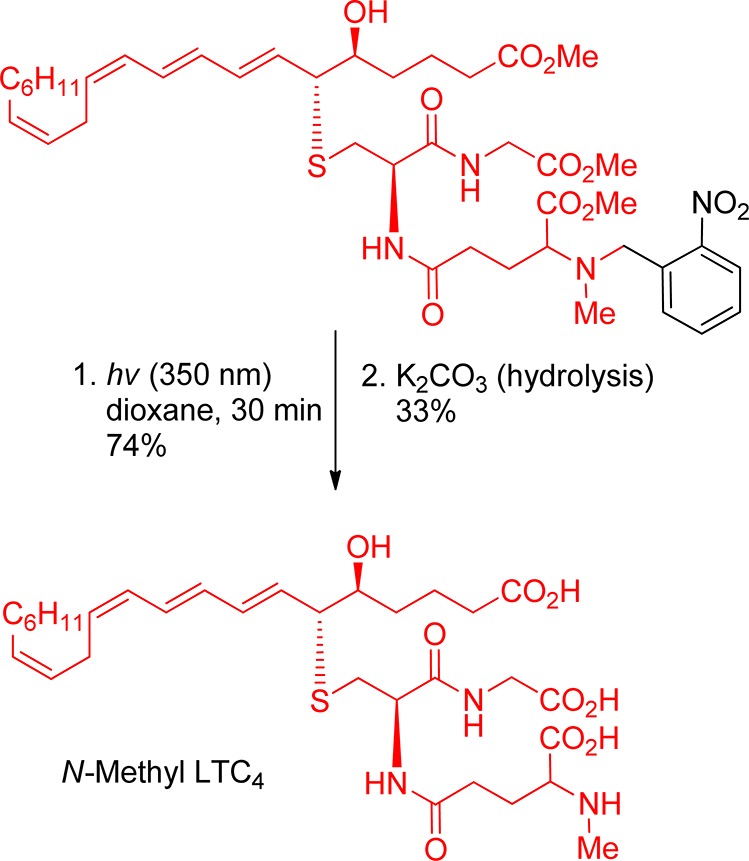

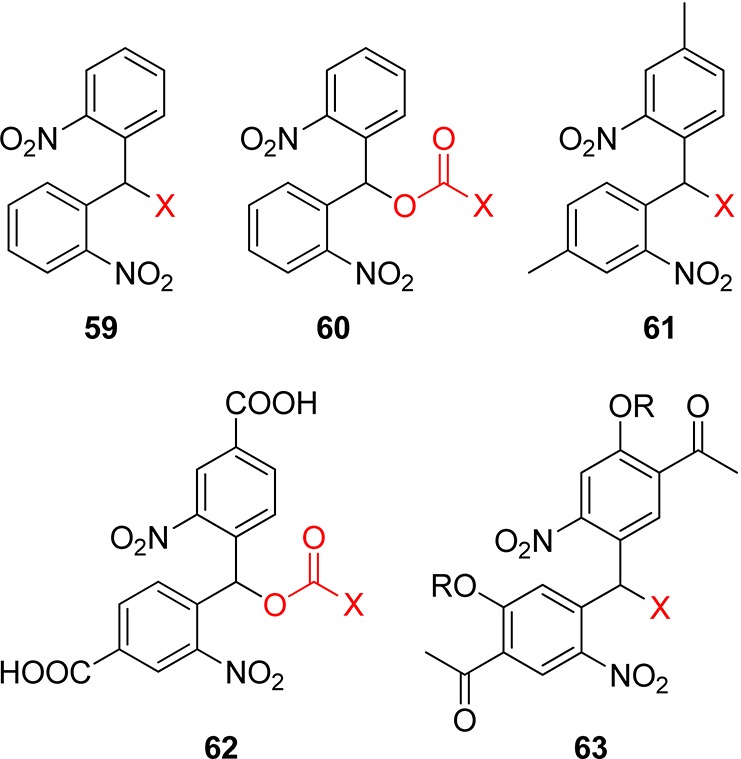

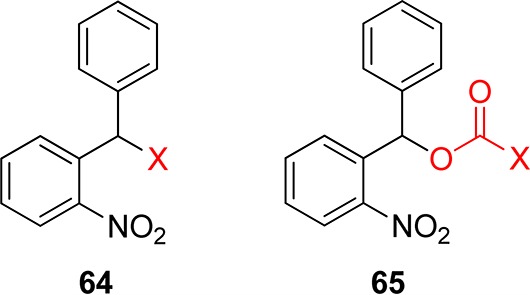

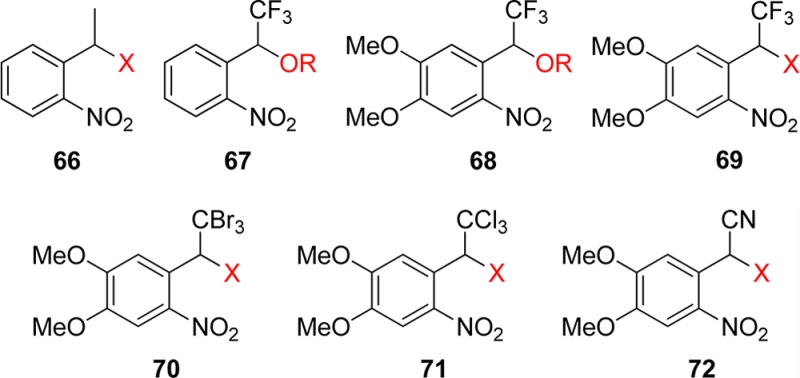

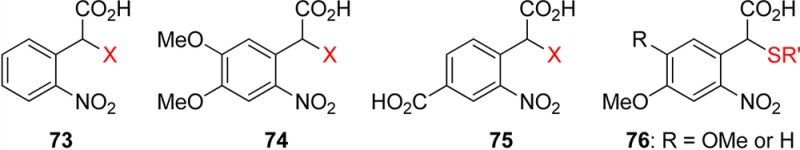

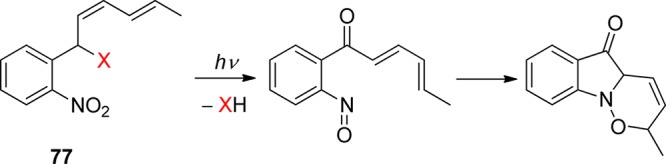

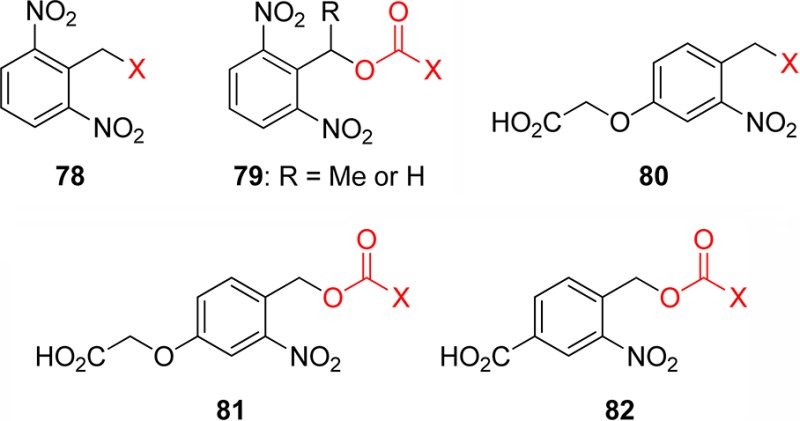

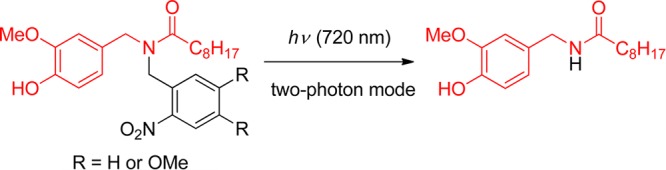

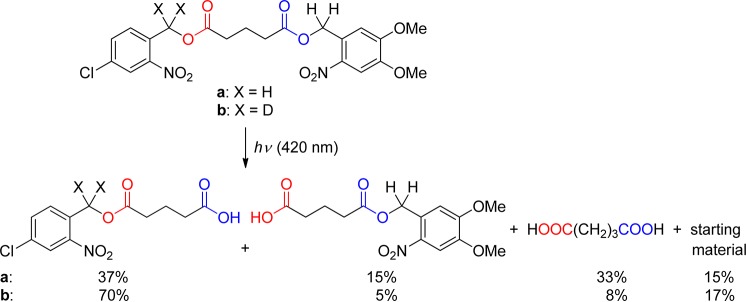

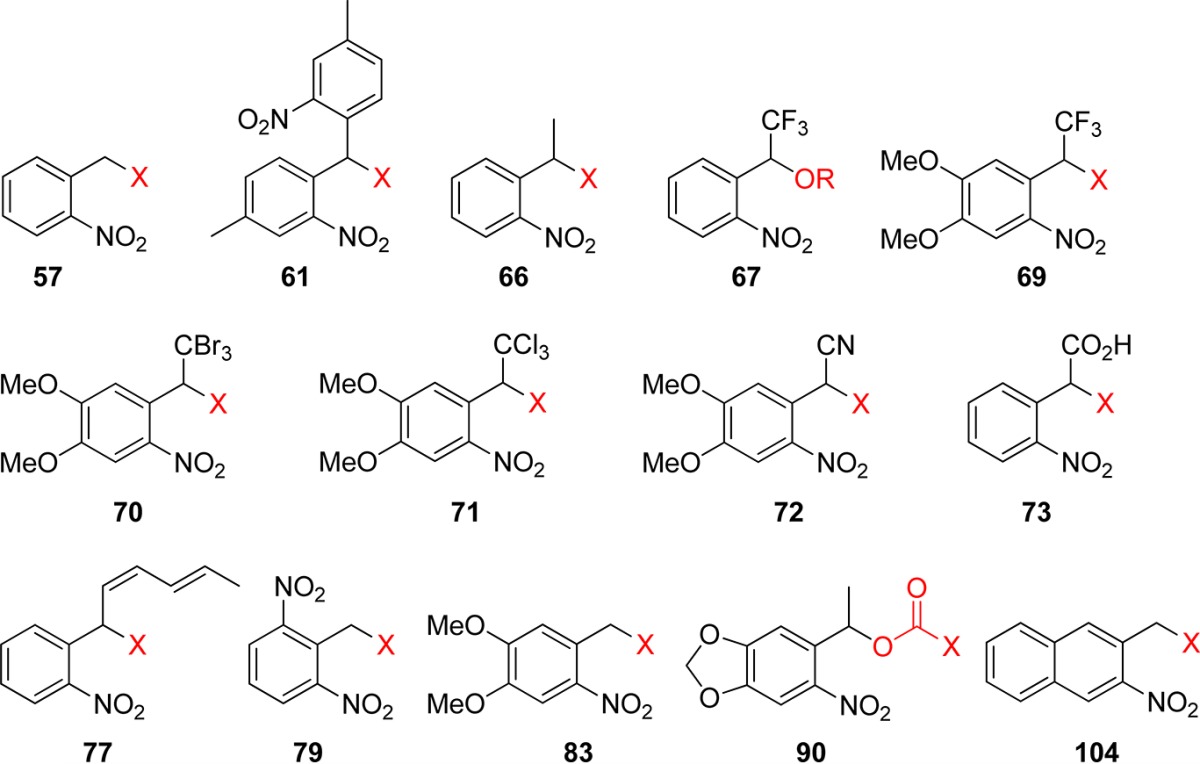

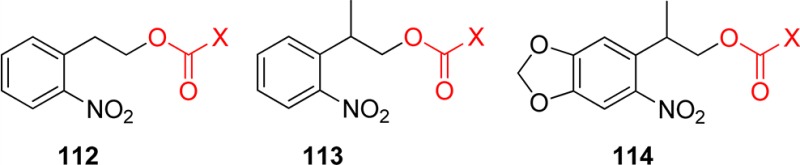

Photoremovable (sometimes called photoreleasable, photocleavable or photoactivatable) protecting groups (PPGs) provide spatial and temporal control over the release of various chemicals such as bioagents (neurotransmitters and cell-signaling molecules), acids, bases, Ca2+ ions, oxidants, insecticides, pheromones, fragrances, etc. Following early reports on PPGs for use in organic synthesis by Barltrop,1 Barton,2 Woodward,3 Sheehan4 and their co-workers, applications to biology were sparked off by Engels and Schlaeger5 and Kaplan and co-workers,6 who first achieved the photorelease of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and ATP, respectively. The latter authors introduced the convenient, if somewhat misleading, term “caged” to designate a compound protected by a PPG. Two general perspectives7 and many more specialized reviews covering applications of PPGs in synthesis,8 biochemistry and neurobiology,9 biomedicine,10 volatiles release,11 polymerization,12 and fluorescence activation13 have been published during the past decade, and a journal issue themed on these topics has recently been published.14 The present review covers recent developments in the field, focusing on the scope, limitations, and applications of PPGs, which are used to release organic molecules. Photoactivation of small inorganic species and ions, such as NO,15 CO,16 Ca2+,9h,17 Zn2+,18 Cd2+,19 or Cu+,20 is not covered. Simplified basic structures of the photoremovable protecting groups discussed in this review are listed in Table 1 (the leaving groups are shown in red).

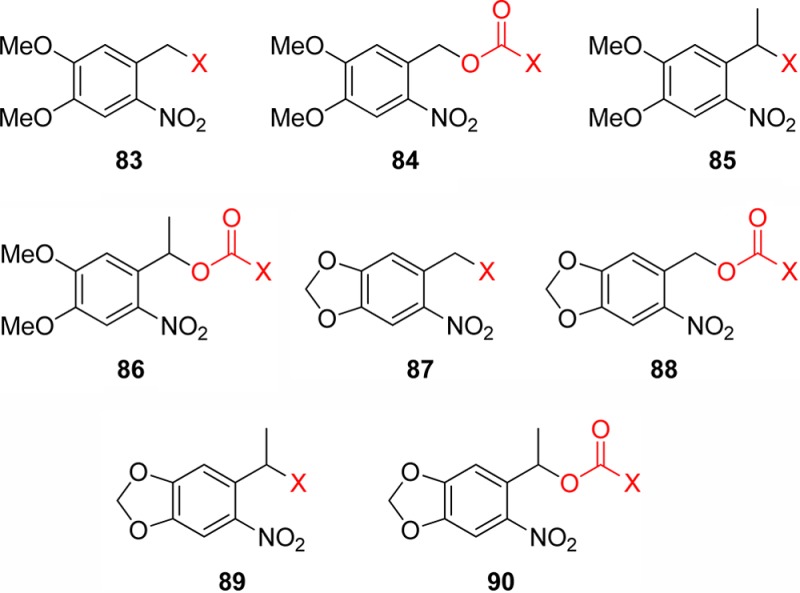

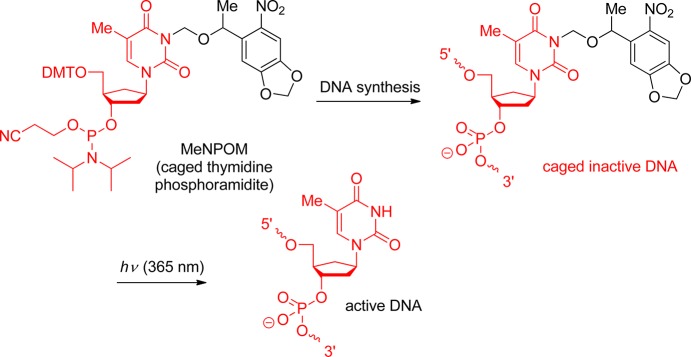

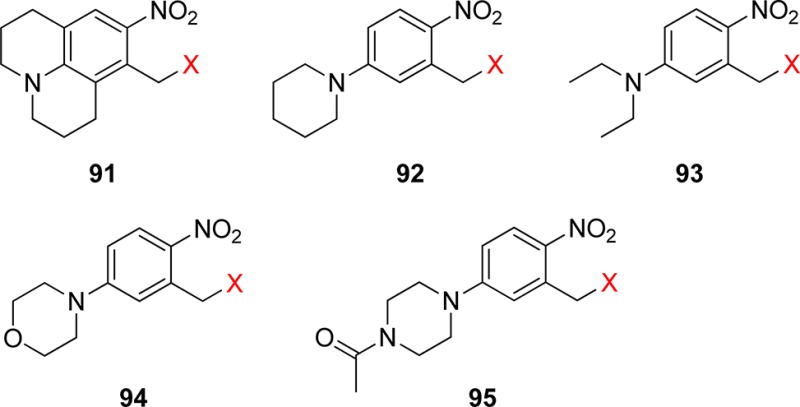

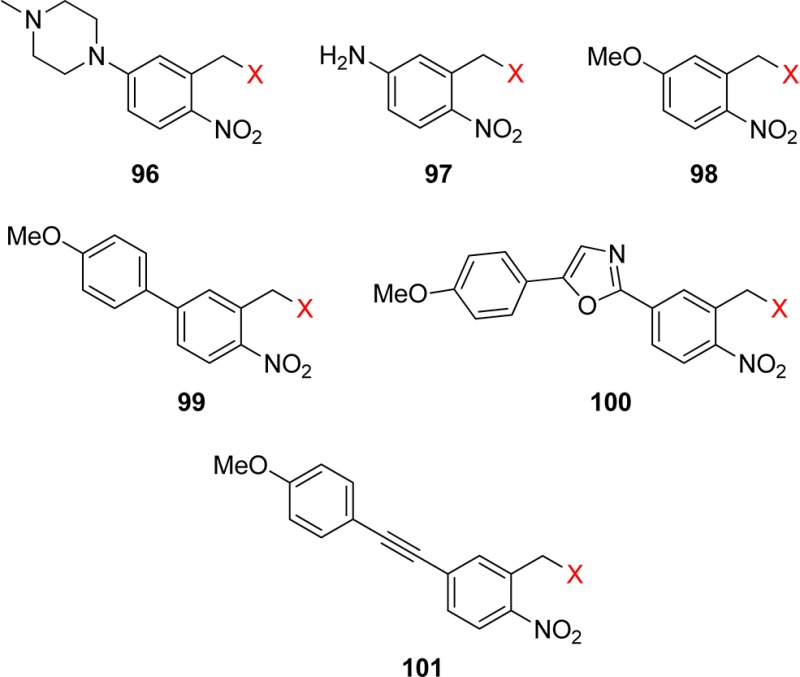

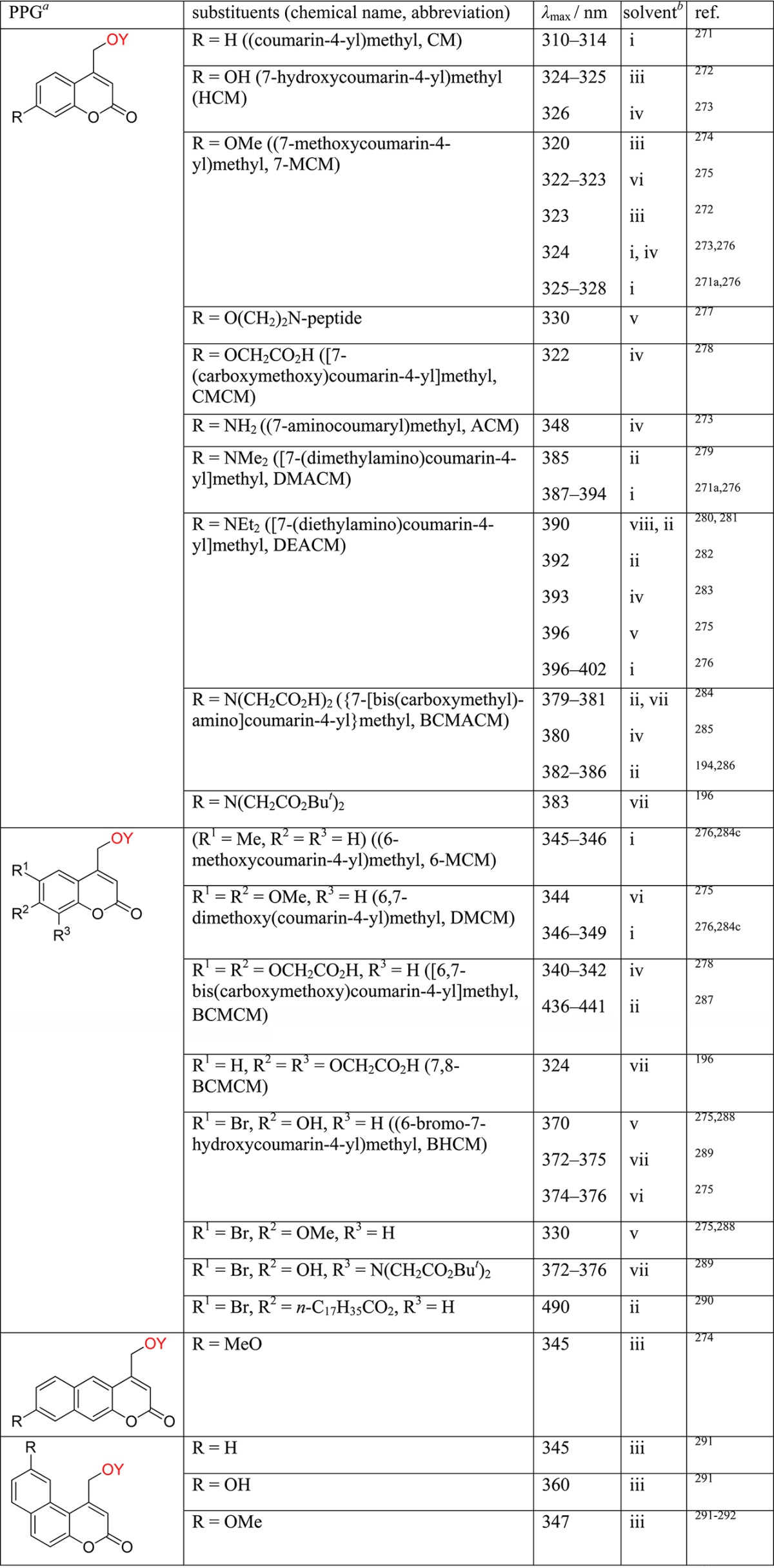

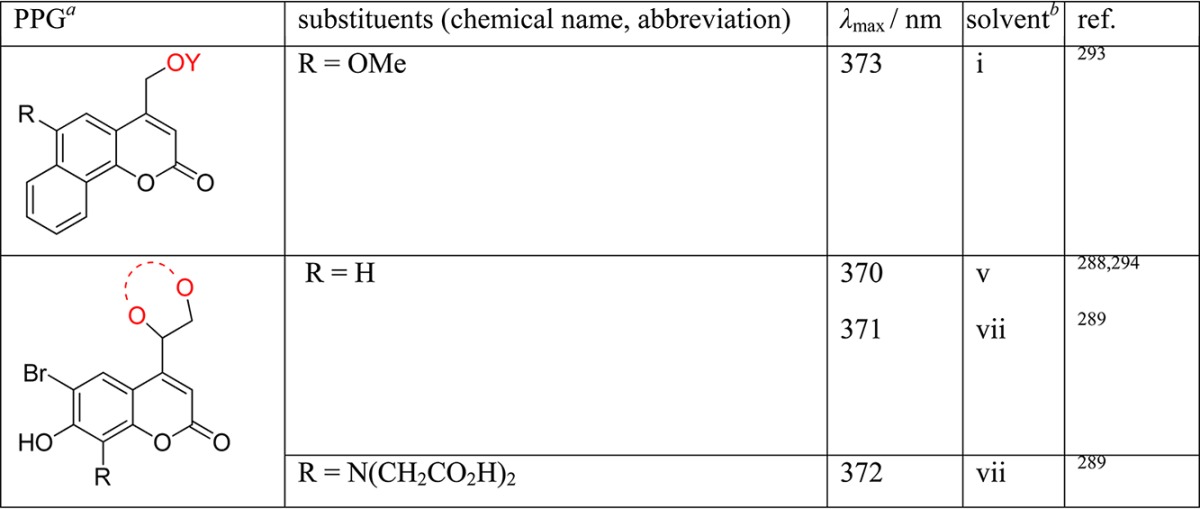

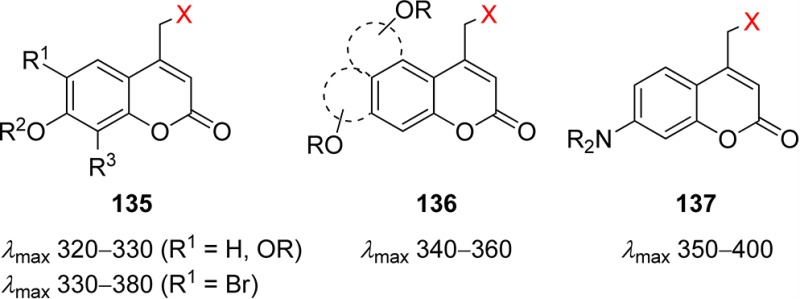

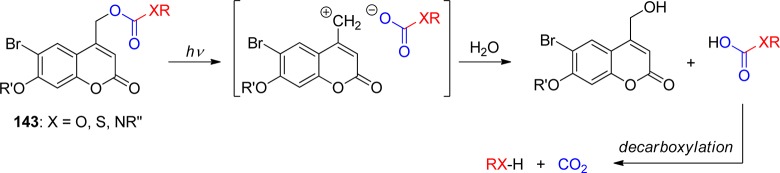

Table 1. Photoremovable Protecting Groups.

The criteria for the design of a good PPG will depend on the application. No single system needs to fulfill all of the following requirements:

-

(i)

In general, the PPG should have strong absorption at wavelengths well above 300 nm, where irradiation is less likely to be absorbed by (and possibly cause damage to) the biological entity.21 Moreover, the photoreaction should be clean and should occur with a high quantum yield or efficiency for release, Φrel. The quantum yield Φrel is equal to the amount of released substrate, nrel/mol, divided by the amount of photons at the irradiation wavelength λ, np/mol = np/einstein, that were absorbed by the caged compound: Φrel = nrel/np. An important measure for the efficacy of a PPG is the product of the quantum yield and the molar decadic absorption coefficient ε of the PPG, Φrelε(λirr), which is proportional to the amount of release at the given excitation wavelength.22

-

(ii)

Sensitive detection of the response under study often depends not only on the product Φrelε(λirr) but also on the background level of activity of the caged compound prior to irradiation. Hence, the PPGs must be pure, exhibit low intrinsic activity, and be stable in the media prior to and during photolysis.

-

(iii)

The PPGs should be soluble in the targeted media; they may further be required to pass through biological barriers such as cell membranes and show affinity to specific target components, for example, binding sites on cancer cells or the active site of an enzyme.

-

(iv)

The photochemical byproducts accompanying the released bioactive reagent should ideally be transparent at the irradiation wavelength to avoid competitive absorption of the excitation wavelengths. Moreover, they must be biocompatible, i.e., they should not react with the system investigated.

-

(v)

To study the kinetics of rapid responses to a released agent in samples such as brain tissue or single live cells, the PPG must be excited by a short light pulse and the appearance rate constant kapp of the desired free substrate must exceed the rate constant of the response under investigation. Commonly, there are several reaction steps involving ground- and excited-state intermediates that precede the actual release of the free substrate. Therefore, detailed knowledge of the reaction mechanism is needed; in particular, the rate-determining step in the reaction path and its lifetime τrd or kapp must be known, unless the appearance of the free substrate (kapp) can be monitored directly by time-resolved techniques.

Nitrobenzyl, nitrophenethyl compounds, and their dimethoxy derivatives (nitroveratryl) (section 3) are by far the most commonly used PPGs. The decay of their primary quinonoid intermediates on the microsecond time scale does not generally correspond to the rate-determining step of the overall reaction, and the release of the free substrate may be orders of magnitude slower. Moreover, photolysis of these compounds forms potentially toxic and strongly absorbing byproducts such as o-nitrosobenzaldehyde. Quite a number of alternative PPGs have been developed that do not suffer from these disadvantages.

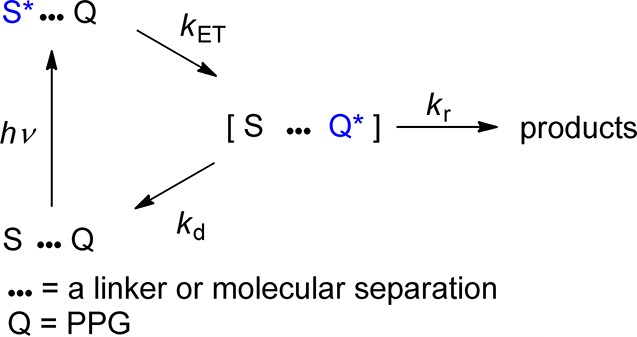

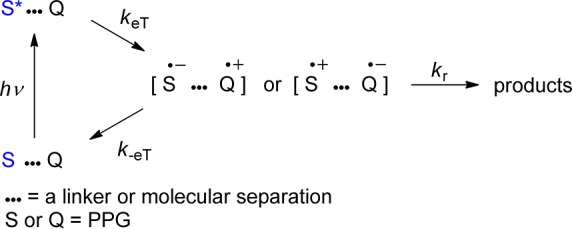

The appearance rate constant kapp of the desired product is equal to the inverse of the rate-determining intermediate’s lifetime τrd, kapp = 1/τrd, which often depends on the solvent as well as on the concentrations of acids and bases including those of the general acids and bases contained in buffers. Release rate constants, kr = ηr/τr, are sometimes quoted, where ηr is the efficiency of the releasing reaction step, ηr = kr /Σk, and τr = 1/Σk is the lifetime of the intermediate that is assumed to release the substrate; Σk includes kr and the rate constant of all competing reactions occurring from that intermediate. Note that the release rate constant kr may be higher or lower than the more relevant appearance rate constant kapp of the desired substrate. Case (a): kr < kapp if Σk > kr, i.e., if reactions other than substrate release contribute to the decay rate of the releasing intermediate. A trivial example of case (a) is shown in Scheme 1. Case (b): kr > kapp if the actual release is preceded by a slower, rate-determining step of the reaction sequence.

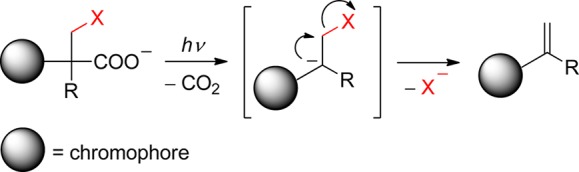

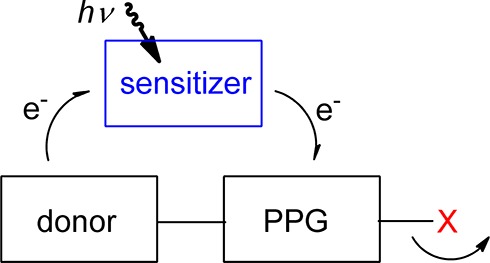

Scheme 1. Simple Case Where the Release Rate Constant of the Free Substrate (Leaving Group) X, kr, Is Smaller than Its Appearance Rate Constant, kapp.

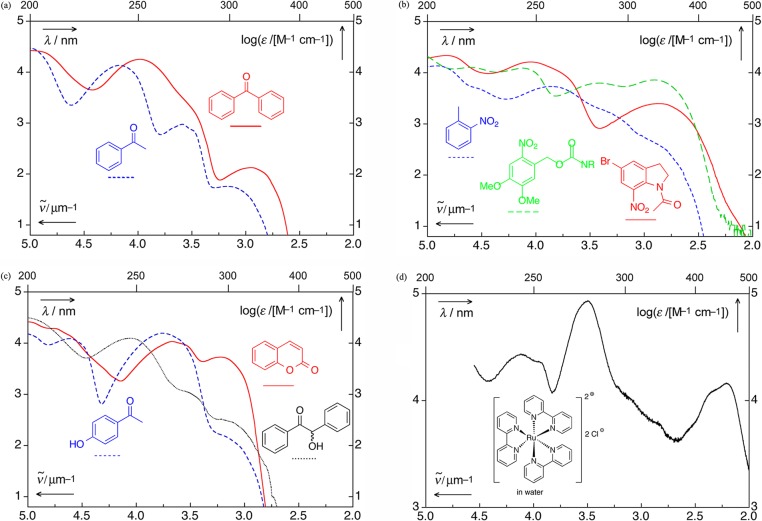

The speed of release is an ambivalent expression; it may refer to the efficiency of a PPG, Φrelε(λirr), the amount released by a given irradiation dose, or to the appearance rate constant in time-resolved work. The absorption spectra of a number of chromophores frequently encountered as PPGs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

UV spectra of selected chromophores.23 (a) Benzophenone (ethanol; solid, red),24 acetophenone (ethanol; dashed, blue);24 (b) 1-acetyl-5-bromo-7-nitroindoline (acetonitrile; solid, red), 2-nitrotoluene (dashed, blue), (3,4-dimethoxy-6-nitrophenyl)methyl (nitroveratryl) derivative (acetonitrile, dashed, green);25 (c) coumarin (acetonitrile, solid, red), p-hydroxyacetophenone (acetonitrile, dashed, blue), and benzoin (acetonitrile, dotted, black); (d) tris(bipyridyl)ruthenium(II) chloride (water).26

2. Arylcarbonylmethyl Groups

Aromatic ketones are thermally stable and synthetically readily accessible compounds; their photophysical and photochemical properties are well understood. The lowest energy transition of simple carbonyl compounds is typically a weak n,π* band (ε ≈ 10–100 M–1 cm–1).27 The higher-energy π,π* absorption bands are strong, and internal conversion to the S1 state is very fast (e.g., ∼100–260 fs for acetophenone).28 The electronic transitions of aromatic ketones are sensitive to solvent polarity and to substitution on the phenyl ring. Hydrogen bonding of protic solvents to the carbonyl oxygen stabilizes the oxygen nonbonding orbital, giving rise to a hypsochromic shift of the n,π* absorption band. Both electron-donating groups and polar solvents tend to stabilize the π,π* states. The strong bathochromic shift induced by para-amino substituents is attributed to a CT interaction29 (for example, λmax for p-aminobenzaldehyde is ∼325 nm (π,π*) in cyclohexane).24 Aromatic ketones are highly phosphorescent and only weakly fluorescent30 due to their fast (>1010 s–1), very efficient intersystem crossing to the triplet state, for which two energetically close lying states (n,π* and π,π*) seem to play a crucial role, possibly due to a S1/T2/T1 intersection.31 The singlet–triplet energy gap is much larger for π,π* than for n,π* states. The lowest π,π* and n,π* triplet states are nearly degenerate, and substitution on the phenyl ring as well as polar solvents may lead to triplet-state inversion.27,32 Some of the important photophysical properties of acetophenone, the parent aryl ketone, are summarized in Table 2. Examples of the absorption spectra of other representative PPG aryl ketones are provided in Figure 1.

Table 2. Photophysical Properties of Acetophenonea.

| solvent | ES/kJ mol–1b | τS/psc | Φfd | ΦTe | ET/kJ mol–1f | Φpg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nonpolar | 33030b | 2533 | <1 × 10–6 34 | 135 | 31036 | 4 × 10–4 37 |

| polar | 33836 | 3933 | 135 | 31136 |

Photophysical properties of many other aromatic ketones can be found in the Handbook of Photochemistry.38

Lowest excited singlet state (S1) energy.

The lifetime of S1.

Fluorescence quantum yield.

Intersystem crossing (ISC) quantum yield.

Lowest triplet state (T1) energy.

Phosphorescence quantum yield (23 °C, isooctane).

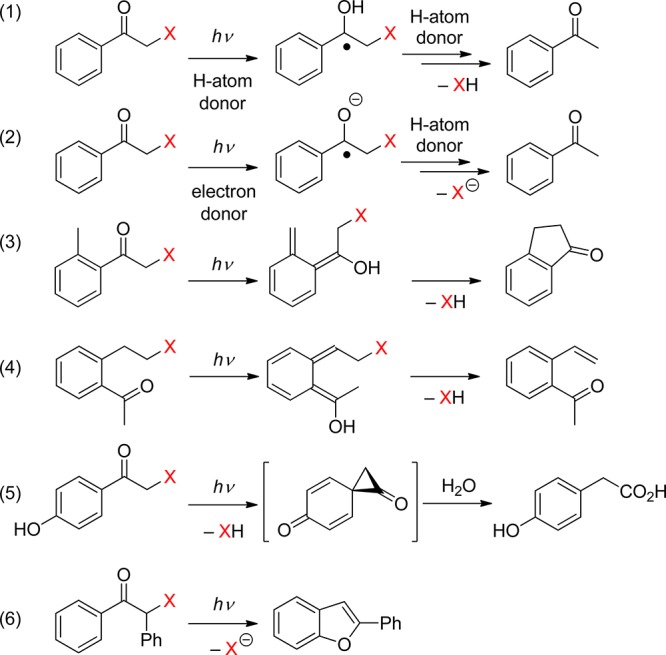

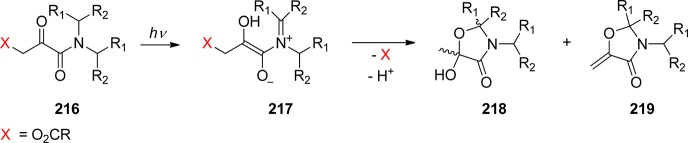

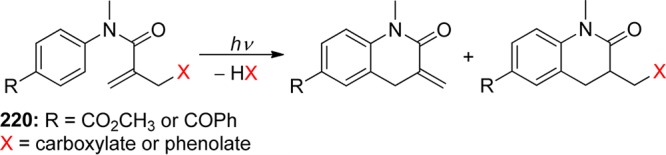

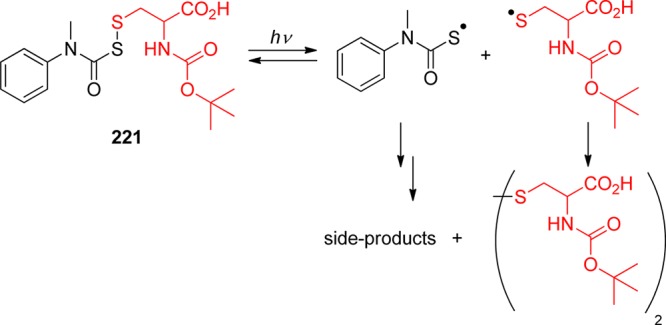

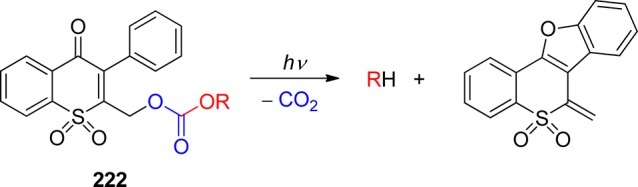

The carbonyl group of aromatic ketones is usually the center of the photochemical reactivity. Scheme 2 shows the most important photoreactions that lead to the liberation of a leaving group (X) and are discussed in the following paragraphs. Ketones with n,π* lowest triplets, possessing a half vacant n orbital localized on the carbonyl oxygen, are far more reactive than those with π,π* lowest triplets with spins delocalized on the aromatic ring. The singlet or triplet n,π* states thus readily abstract hydrogen atoms from suitable donors (entry 1), whereas both n,π* and π,π* states can be reduced in the presence of good electron donors (entry 2). The reaction intermediates hereby formed may subsequently release X– from the α-position. Intramolecular H-transfer reactions in o-alkylacetophenones result in the formation of ground-state photoenols that liberate X– from the α- (entry 3) or o-ethyl (entry 4) positions. Entry 5 shows the p-hydroxyphenacyl moiety, which undergoes a photo-Favorskii rearrangement to release X–. Finally, the benzoin derivative in entry 6 releases X– to form 2-phenylbenzofuran.

Scheme 2. Photochemistry of Aromatic Ketones that Release a Leaving Group (X).

2.1. Phenacyl and Other Related Arylcarbonylmethyl Groups

Using phenacyl compounds as PPGs has been a subject of interest for several decades.39 α-Substituted esters of the phenacyl chromophore are typical of the PPG framework for release of carboxylic acids, for example. Homolytic scission of the ester C–O bond, which would result in the formation of phenacyl and acyloxy radicals, has not been confirmed. Instead, a mechanism that involves hydrogen abstraction from a hydrogen-atom donor by the excited carbonyl group (photoreduction27) of phenacyl ester via a ketyl ester intermediate (entry 1, Scheme 2) has been established by laser flash photolysis.40

Excited phenacyl and 3-pyridacyl esters of benzoic acid were reported to react with an excess of aliphatic alcohols in a chain reaction process to give benzoic acid in addition to acetophenone and 3-acetylpyridine, respectively, as the byproducts.41 Singh and co-workers have reported that arylcarbonylmethyl groups, i.e., naphth-2-ylcarbonylmethyl42 and pyren-1-ylcarbonylmethyl,43 can release various carboxylic acids upon irradiation. The photochemistry of the 4-methoxyphenacyl moiety is discussed in section 2.3.

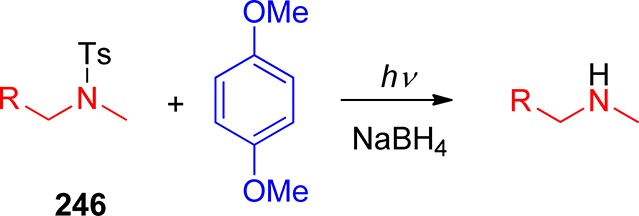

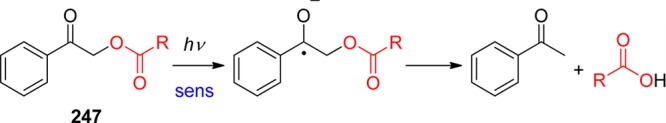

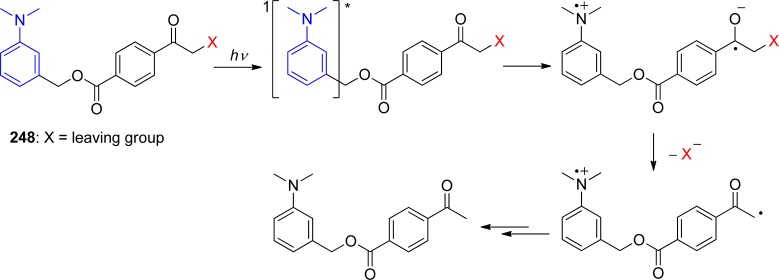

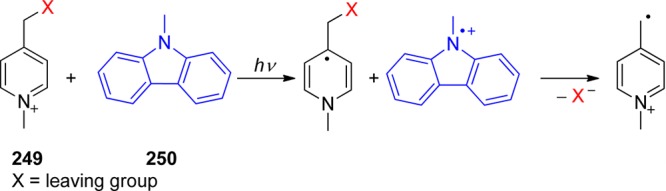

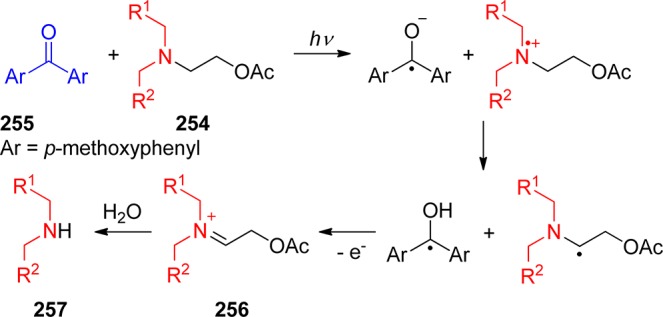

In the presence of an electron donor, a mechanism involving electron transfer from the donor to the carbonyl group, followed by release of the leaving group, can also be accommodated (entry 2, Scheme 2). This PPG strategy will be discussed in section 8.2.

When a relatively stable radical can be released from the α-carbon of the phenacyl group, phenacyl radicals are produced in the primary homolytic step. This has been demonstrated in the reactions of phenacyl halogenides44 or azides.45 An alternative mechanism, formation of the phenacylium cation from phenacyl ammonium salts, which are used as photoinitiators for cationic polymerization reactions, upon irradiation via a heterolytic cleavage of the C–N bond, has been proposed.46 Recently Klán and co-workers demonstrated that readily accessible S-phenacyl xanthates undergo photoinitiated homolytic scission of the C–S bond in the primary step, opening their use as PPGs for alcohols in the presence of H-atom-donating solvents, where the xanthate moiety represents a photolabile linker.47

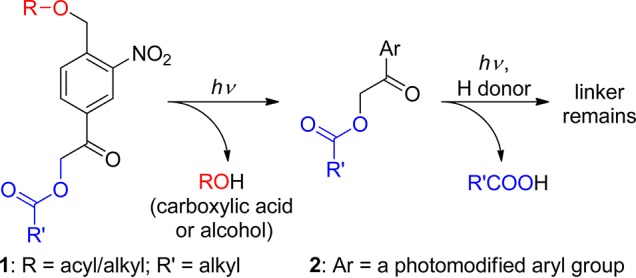

The 4-acetyl-2-nitrobenzyl (ANB, 1) moiety, substituted in both the benzylic and the phenacyl positions with leaving groups, has recently been proposed as a monochromophoric photocleavable linker (Scheme 3).48 This linker thus combines the properties of two well-known photoremovable groups, 2-nitrobenzyl (section 3.1) and phenacyl moieties, in a single chromophore. Liberation of R′CO2H from the intermediate 2 requires the presence of an H-atom donor. Depending on the presence or absence of H-atom donors, the attached groups can be disconnected selectively and orthogonally upon irradiation in high chemical yields (88–97%).

Scheme 3. Monochromophoric Photocleavable Linker48.

2.2. o-Alkylphenacyl Groups

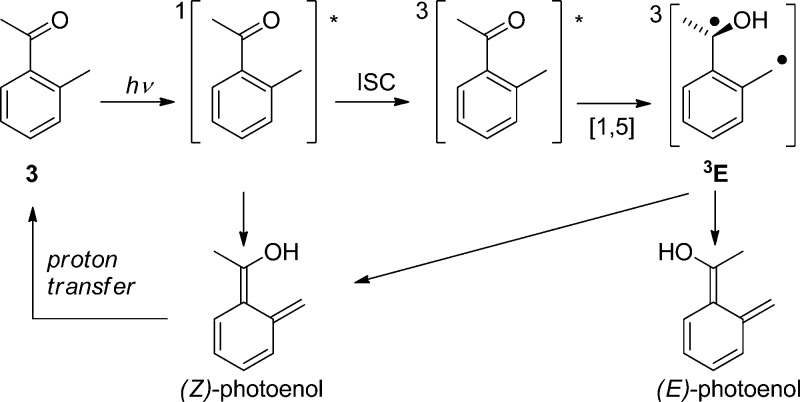

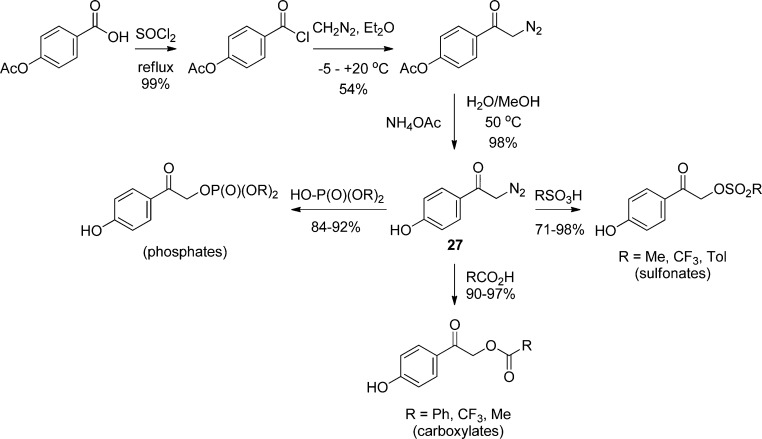

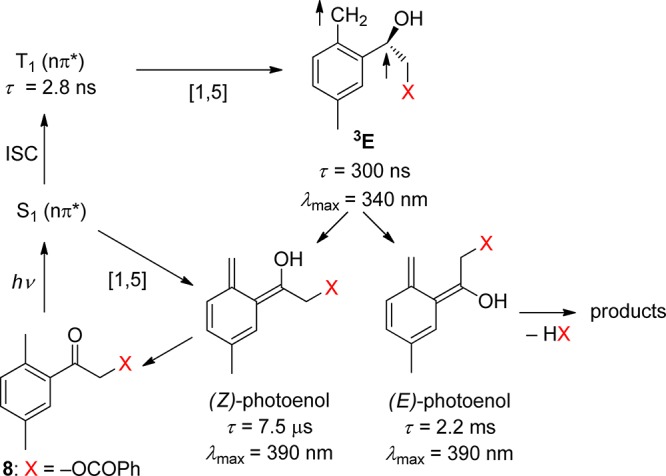

2-Alkylphenyl ketones readily photoenolize to the corresponding dienols (photoenols, o-xylylenols). For example, 2-methylacetophenone (3) undergoes intramolecular 1,5-hydrogen abstraction via the triplet state to form a triplet 1,4-biradical (enol, 3E) that yields two isomeric, (E)- and (Z)-, photoenols, whereas fast direct enolization from the lowest excited singlet state produces only the (Z)-isomer (Scheme 4).49 This scheme may serve as a blueprint for the reactions of related 2-alkylphenacyl compounds. The (Z)-isomer, having a lifetime similar to that of the triplet biradical, is generally converted efficiently back to the starting molecule via a 1,5-sigmatropic hydrogen transfer. Its lifetime is solvent-dependent because hydrogen bonding of the hydroxyl group to a polar solvent strongly retards intramolecular hydrogen back-transfer.49a In contrast, reketonization of the (E)-dienols requires intermolecular proton transfer that may occur either by protonation of the methylene group by a general acid or by proton transfer from the enol by the solvent or a general base, followed by carbon protonation of the dienol anion.49a The resulting long lifetime of the (E)-isomers in dry solvents allows for thermal conrotatory ring closure to give benzocyclobutenols, or trapping by diverse dienophiles such as alkenes, alkynes, or carbonyl compounds in a stereospecific [4 + 2]-cycloaddition reaction.50 However, they may persist up to seconds in the absence of trapping agents. Photoenolization reactions have been thoroughly reviewed by Sammes in the 1970s,51 recently by Klán et al.,52 and, to a modest extent, in several other reviews and book chapters.8d,27,32,50,53

Scheme 4. Photoenolization of 2-Methylacetophenone49.

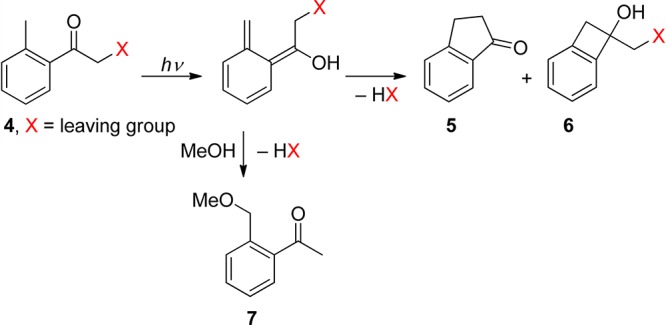

When leaving groups are present on the α-carbon of 2-alkylphenacyl derivatives (4), they are released from the photoenol intermediates (Scheme 5). In general, the indanone54 (5) and benzocyclobutenol55 (6) side-products are formed in non-nucleophilic solvents, whereas acetophenone derivatives substituted on the o-methyl group 7 are produced in the presence of a nucleophile, such as methanol.

Scheme 5. Photochemistry of 2-Alkylphenacyl Compounds54.

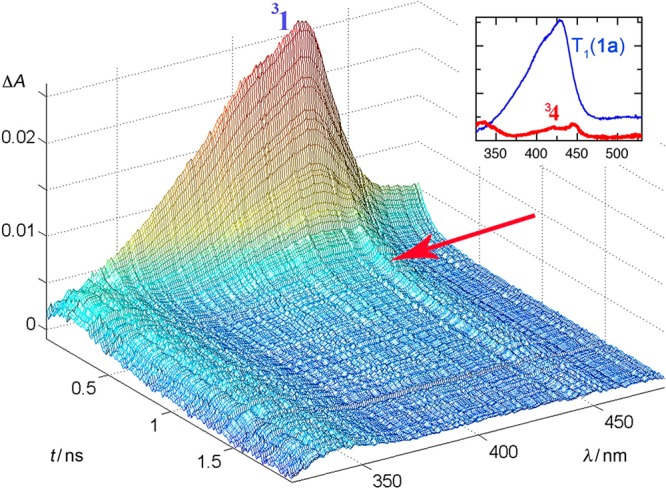

This reaction, reported for the first time on phenacyl chlorides and bromides by Bergmark,56 was shown by Klán and co-workers to be useful for PPG applications.54b Klán and Wirz later demonstrated that 2,5-dimethylphenacyl (DMP) can serve as a PPG for carboxylic acids,57 phosphates, sulfonates,54a alcohols (as carbonates),58 and amines (as carbamates).59 It was recognized that only moderately good or excellent leaving groups are released efficiently within the photoenol lifetime. Studies by laser flash photolysis showed that photolysis produces the anticipated reaction intermediates, the short-lived triplet enol 3E, and two longer-lived, ground-state photoenols assigned to the corresponding (Z)- and (E)-photoenols.54a,57b,58 For example, the (E)-photoenol was found to have a sufficient lifetime (1–100 ms) to release carboxylic acids and carbonates, while the (Z)-photoenol (τ = 0.5–10 μs) regenerated the starting ketone.57b,58 Irradiation of DMP esters in methanol efficiently releases the corresponding free acid (HX) along with indanone and 2-(methoxymethyl)-5-methylacetophenone as the major coproducts, as shown in Scheme 5. The mechanism of DMP benzoate (8) photolysis, determined by laser flash spectroscopy (LFP) in degassed methanol, is displayed in Scheme 6.57b Three intermediates, a short-lived one, λmax ≈ 340 nm (triplet enol 3E), and two longer-lived ones, λmax ≈ 390 nm (photoenols), were formed. In this case, only the longer-lived (E)-photoenol released benzoic acid via the triplet pathway with an appearance rate constant for benzoate of kapp = 1/τ(E-enol) = 4.5 × 102 s–1.

Scheme 6. Photochemistry of DMP Esters57b.

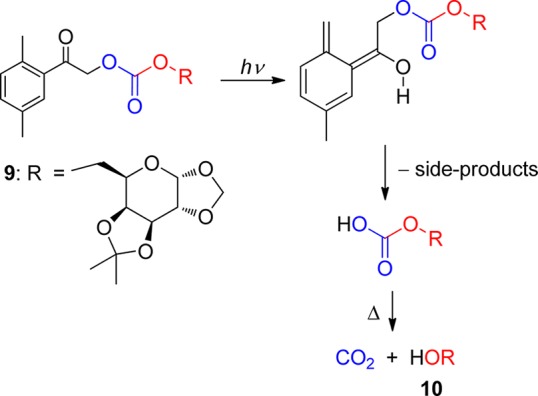

Structurally constrained phenyl ketones, such as 1-oxoindan-2-yl and 1,3-dioxoindan-2-yl derivatives, which can form only the short-lived (Z)-xylylenols, do not release carboxylic acids upon irradiation.60 Only the chloride anion was found to be eliminated from the (Z)-xylylenol (τ = 23 μs in methanol) obtained from 2,5-dimethylphenacyl chloride via the singlet pathway.61 Poor leaving groups such as alcohols and amines that are not efficiently eliminated from the short-lived photoenol intermediates have been attached through a carbonate58 or carbamate59 linkage, respectively, which have similar leaving group properties to that of a carboxylate. For example, the galactopyranosyl carbonate 9 releases a carbonate monoester in a high chemical yield that disintegrates thermally into the corresponding alcohol 10 and CO2 (Scheme 7)58 on the millisecond time scale.62 Table 3 summarizes the photochemical data for the DMP chromophore substituted by various leaving groups.

Scheme 7. Photochemistry of a DMP Galactopyranosyl Carbonate58.

Table 3. 2,5-Dimethylphenacyl (8, DMP) Photoremovable Group.

| leaving group, X (protected species) | solvent | quantum yield, Φ | chemical yield of HX release (%) | kapp/s–1 a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl | benzene | 0.1156a (0.12)54a | 4.4 × 106 61 | |

| methanol | 0.7656a (0.78)54a | 4.4 × 104 61 | ||

| OC(=O)R (carboxylic acids) | benzene | 0.18–0.2554b,57b | 85–9554b | ∼257b |

| methanol | 0.09–0.1457b | 9254b | 4.5 × 102 57b | |

| OP(=O)(OR)2 (phosphates) | benzene | 0.0954a | ∼254a | |

| methanol | 0.7154a | 9454a | 5 × 104 54a | |

| OS(=O)2R (sulfonic acids) | benzene | 0.16–0.1954a | ||

| methanol | 0.6854a | 90–9354a | 4 × 104 54a | |

| OC(=O)OR (alcohols) | cyclohexane | 0.36–0.5158 | >7058 | b |

| methanol | 0.09–0.2058 | b | ||

| OC(=O)NR2 (amines) | cyclohexane | 0.054–0.08959 | b | |

| acetonitrile | 0.035–0.07059 | 9759 | b | |

| methanol | 0.027–0.06159 | b |

Appearance rate constant of the leaving group, calculated as kapp = 1/τenol.

Slow, presumably <1 ms–1.

Until now, only a few applications of the o-methylphenacyl moiety as a photoremovable protecting group have been reported. Wang and co-workers used the DMP photoremovable group in polymer-supported synthesis,63 and Park and Lee showed that this moiety can be part of new photoresponsive polymers.64

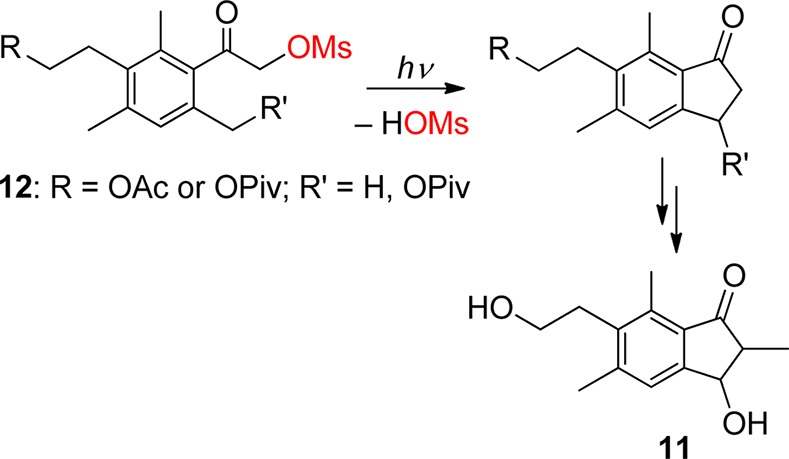

On the other hand, the photochemistry of α-substituted o-alkylphenacyl derivatives was utilized for the photochemical synthesis of interesting functionalized indan-1-ones. In such cases, releasing the leaving group is not of primary interest; it is designed to be a good leaving group and not to interfere with the course of the synthesis. Wessig and co-workers used this concept to prepare various synthetically interesting 1-indanone model derivatives65 and later two sesquiterpene indane derivatives, pterosine B or C (e.g., 11, Scheme 8), in which the key step is the photoenolization reaction of 12.66 Klán and co-workers showed that photolysis of 4,5-dimethoxy-2-methylphenacyl benzoate can lead to the corresponding indanone derivative that is a precursor for the subsequent synthesis of donepezil, a centrally acting reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor used to treat Alzheimer’s disease.67 Park and collaborators have recently shown that photolysis of 2,4,6-trialkylphenacyl benzoates can also lead to the corresponding benzocyclobutenols (6 in Scheme 5) in addition to indanones,55 whereas irradiation of α-dichloro-2-acetophenone yields a mixture of various photoproducts.68 Berkessel and co-workers used the photoenolization reaction as a tool to study the cyclization of 4′-benzophenone-substituted nucleoside derivatives as models for ribonucleotide reductases.69

Scheme 8. Photochemical Synthesis of Pterosines66.

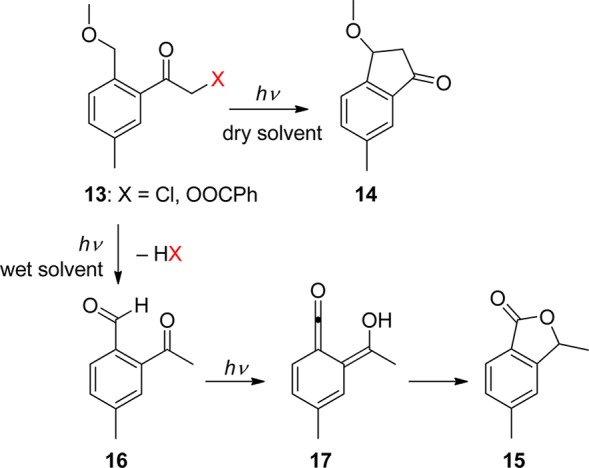

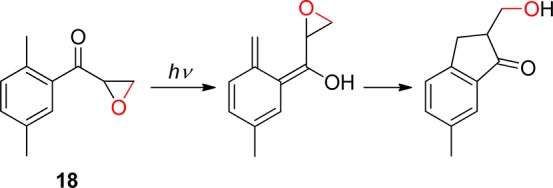

Klán and co-workers reported that the photolysis of 2-(alkoxymethyl)-5-methyl-α-chloroacetophenones (13) is very sensitive to traces of water in the solvent (Scheme 9).70 Whereas 3-methoxy-6-methylindan-1-one (14) was a major product in dry, non-nucleophilic solvents, the isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one 15 was obtained in the presence of trace amounts of water. The authors demonstrated that the photoenols produced by photolysis of 13 add water as a nucleophile to yield 2-acetyl-4-methylbenzaldehyde (16), which subsequently forms 17 via a second, singlet-state photoenolization reaction. The same research group also reported that irradiation of the 2,5-dimethylbenzoyl oxiranes 18 results in a relatively efficient and high-yield formation of β-hydroxy-functionalized indanones that structurally resemble biologically active pterosines (Scheme 10).71 In this case, a ring-opening process, rather than release of a leaving group, follows the photoenolization step. An electronic excited-state switching strategy has been utilized to control the selectivity of this reaction in the total synthesis of indanorine.72 The excited-state character of the parent compound was changed to create a productive 3n,π* state by a temporary structural modification selected on the basis of quantum chemical calculations prior to the synthesis. In addition, competition of a triplet-state photoenolization reaction with a photo-Favorskii rearrangement for (o/p)-hydroxy-o-methylphenacyl esters was shown to depend on the water content of the solvent.73

Scheme 9. Photochemistry of 2-(Alkoxymethyl)-5-methyl-α-chloroacetophenones70.

Scheme 10. Photochemistry of 2,5-Dimethylbenzoyl Oxiranes71.

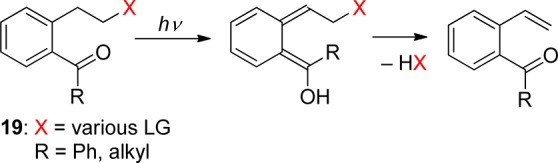

In the 1970s, Tseng and Ullman proposed a new PPG based on (2-hydroxyethyl)benzophenone derivatives (19, R = Ph, Scheme 11), having a leaving group attached in the benzophenone ortho position via an ethylene linker.74 A recent methodical investigation by Pirrung and his co-workers was carried out to elucidate the scope and limitations of the deprotection reaction.75 Alternatively, Wirz7a and later Banerjee and their co-workers76 proposed a similar photoremovable protecting group based on the 1-[2-(2-hydroxyalkyl)phenyl]ethanone 19 (R = alkyl, Scheme 11). The leaving group was reported to be released with a low photochemical efficiency.76 Interestingly, irradiation of 2-acetylphenyl- or 2-benzoylphenylacetic acid results in efficient release of CO2.77

Scheme 11. Photochemistry of 1-[2-(2-Hydroxyalkyl)phenyl]ethanones74.

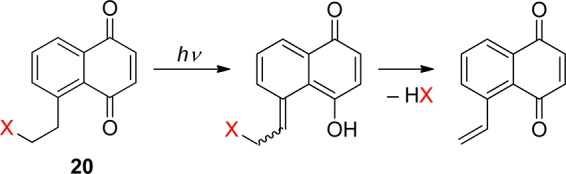

The same mechanism, photoenolization followed by heterolytic elimination of HX, was shown to operate in substituted 5-(ethylen-2-yl)-1,4-naphthoquinones (20, X = Br, dialkyl phosphate, carboxylate), a photoremovable protecting group that absorbs up to 405 nm and provides fast and efficient release of bromide or diethyl phosphate (Φ = 0.7 in aqueous solution) (Scheme 12).78 The blue photoenol is formed in the ground state within 2 ps of excitation and with a quantum yield of unity.79

Scheme 12. Photochemistry of 5-(Ethylen-2-yl)-1,4-naphthoquinones78.

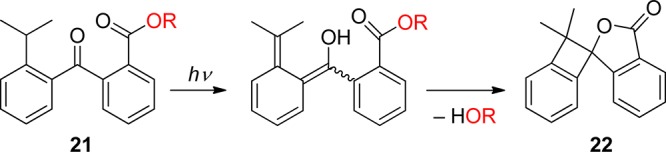

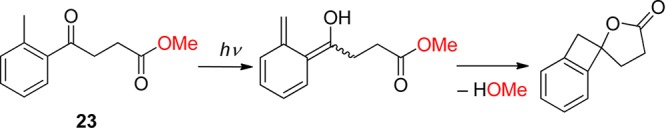

Photoenolization reactions can also be used for releasing protected alcohols through intramolecular lactonization. Gudmundsdottir and her collaborators reported that the corresponding (Z)- and (E)-photoenols are produced by irradiation of the 2-(2-isopropylbenzoyl)benzoate ester 21 via the triplet excited state (Scheme 13).8d,80 An alcohol, such as geraniol (in up to 90% chemical yield), and the side-product 22 are formed in various solvents as well as in thin films. 2-(2-Methylbenzoyl)benzoate esters are not reactive under the same conditions.80a In addition, the 4-oxo-4-o-tolylbutanoate 23 releases methanol by a photoenolization-induced lactonization process (Scheme 14).81

Scheme 13. Photochemistry of 2-(2-Isopropylbenzoyl)benzoate Esters8d,80.

Scheme 14. Photochemistry of 4-Oxo-4-o-tolylbutanoate81.

2.3. p-Hydroxyphenacyl Groups

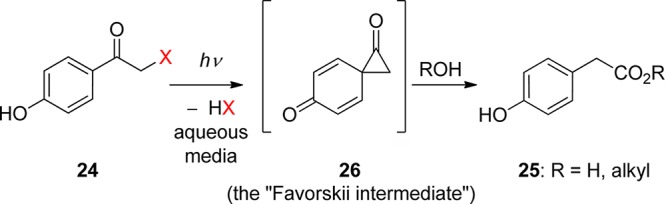

Among the known photoremovable protecting groups, p-hydroxyphenacyl (24, pHP, Scheme 2 entry 5 and Scheme 15) has emerged as a promising candidate.82 Since debuting a little over a decade ago, the pHP chromophore has found application as a photoremovable protecting group in neurobiology,7,83 enzyme catalysis,7b,9u,83b,83c and synthetic organic chemistry.84 The intriguing features of this protecting group are the skeletal rearrangement that accompanies the release of a substrate, the quantitative chemical yield of released product, and the necessary role of water.7,9u,82,83,85 Advantageous properties are the hydrophilicity of the pHP ligand, the high quantum yields, and the unusually clean reaction that yields only one significant byproduct.

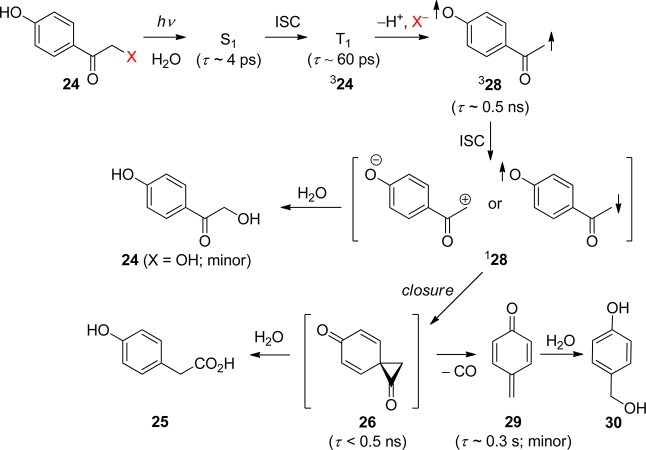

Scheme 15. Photochemistry of pHP as a Protecting Group82.

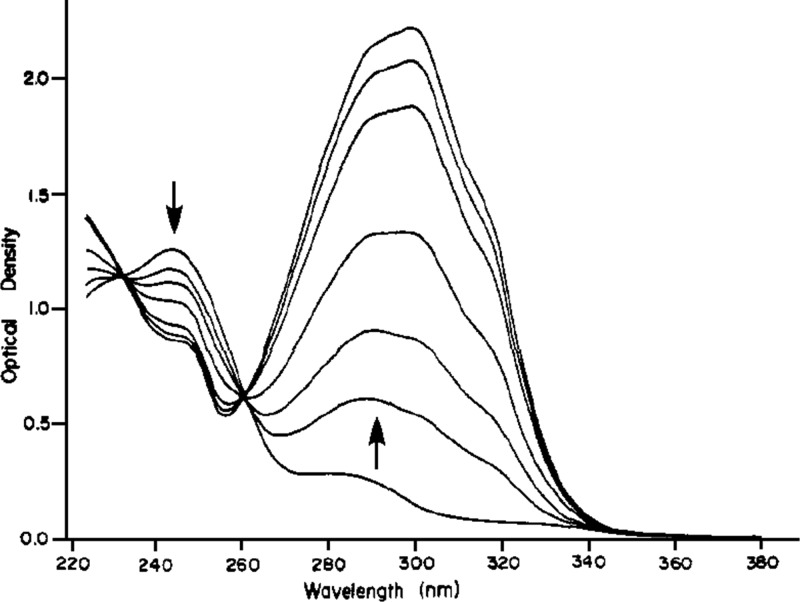

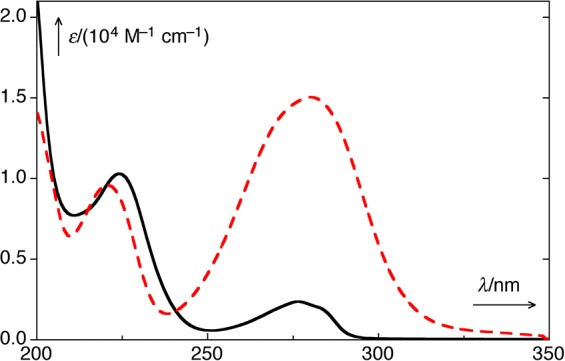

The absorption spectrum changes drastically as the reaction progresses from a conjugated phenyl ketone (Figure 1) to a nonconjugated phenol, 4-hydroxyphenyl acetate (25, R = H, Figure 2). The purported intermediate (26) shown in Scheme 15 is reminiscent of the cyclopropanone intermediates proposed for the Favorskii rearrangement;86 thus this transformation has been termed the photo-Favorskii rearrangement.87

Figure 2.

UV–vis absorption spectra of p-hydroxyphenacyl diethyl phosphate (24, X = OPO(OEt)2; pHP DEP; dashed, red) and p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (25, R = H; black) in H2O/MeCN (1:1).88

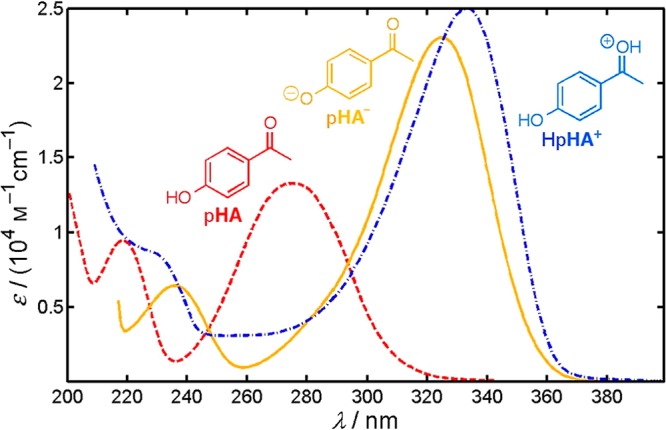

p-Hydroxyacetophenone (pHA, 24, X = H) serves as a model for the pHP chromophore. Figure 3 displays the absorption spectra of pHA in neutral water, of pHA– in aqueous NaOH, and of protonated HpHA+ in aqueous HClO4.89

Figure 3.

Absorption spectra of pHA (24, X = H; dashed, in red) in neutral water (λmax = 278 nm), of pHA– in 0.05 M aqueous NaOH (λmax = 325 nm; solid, in yellow), and of HpHA+ in 70% aqueous HClO4 (λmax = 333 nm; dash–dot, in blue). The triplet excited state equilibria are shown in Scheme 18. The pKa of ground state pHA is 7.9 ± 0.1 (the concentration quotient at ionic strength I = 0.1 M, 25 °C). Adapted with permission from ref (89). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

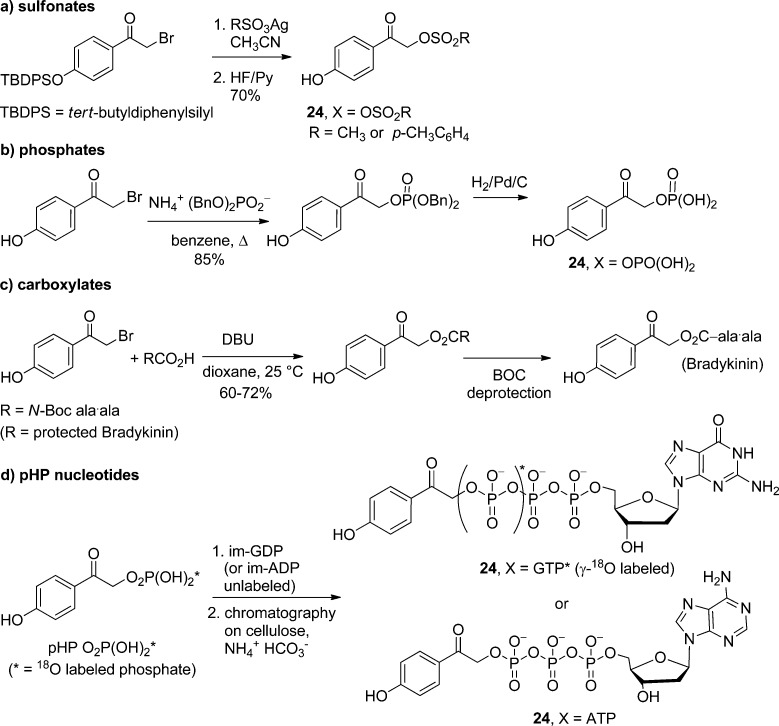

pHA (24, X = H) is also the basic framework for the synthesis of the parent pHP protecting group that accommodates an expanding number of leaving groups (HX).7,9u,82,83,85d,85e Most of the leaving groups have been introduced through a sequence of bromination of pHA followed by its SN2 displacement with the conjugate base of the leaving group (X–) under basic conditions82,83c,85a−85c (Scheme 16a–c). In some instances, protection of the phenol group by benzylation, silylation, or acetylation is required.

Scheme 16. Nucleophilic Substitution Routes for pHP (24) Functional Group Protection.

More complex syntheses are required for more reactive or highly functionalized leaving groups, such as protected nucleotides, i.e., pHP ATP (24, X = ATP),82,83c,84,90 pHP GTP,91 and 18O-labeled isotopomers of pHP GTP.91,92p-Hydroxyphenacyl monophosphates are available either through displacement of pHP Br (24, X = Br) or through esterification of 2,4′-dihydroxyacetophenone.85b Dibenzyl, diphenyl, and diethyl phosphates, for example, are sufficiently nucleophilic to undergo SN2 replacement when the reagents and solvents are rigorously dried. The benzyl groups can be removed by hydrogenolysis with H2/Pd after ketal protection of the phenacyl carbonyl.82,83cp-Hydroxyphenacyl phosphoric acid then can be coupled with ADP or GDP through their imidazolium salts to provide the protected nucleotides pHP ATP82,83c,90 and pHP GTP,90,91 respectively (Scheme 16d). These protected nucleosides have found several applications in studies on enzyme catalysis. An advantage of this sequence is the ability to introduce site-specific 18O-labeled isotopomers of GTP90,91 that are used as probes for functional group assignment and dynamic changes in time-resolved Fourier transform infrared (TR-FTIR) studies. Of the leaving groups thus far explored, sulfonates,9u,85d,93 phosphates,7,9u,82,83,85a−85d,90−93 and carboxylates,7,9u,83,85a−85c,93 are the most efficacious and therefore most commonly encountered.

Another, less frequently encountered synthetic method uses addition of α-diazo-p-hydroxyacetophenone (27) to the conjugate acid of the leaving group (HX) under acidic conditions (Scheme 17).93 This approach is particularly useful for protection of highly reactive or base-sensitive leaving groups. Advantages of the diazoketone approach include the ease of synthesis of a variety of substituted diazoacetophenones and the mild conditions for the coupling reaction. The yields are generally good, and the only byproduct is N2. Furthermore, protection of the phenolic OH group or other, less acidic functional groups on the leaving group is normally unnecessary. When the phenolic OH does require protection, the acetate ester is either retained or otherwise readily prepared and is later removed by mild hydrolysis.

Scheme 17. Strategies for α-Diazo-p-Hydroxyacetophenone Coupling to Protect Acidic Leaving Groups93.

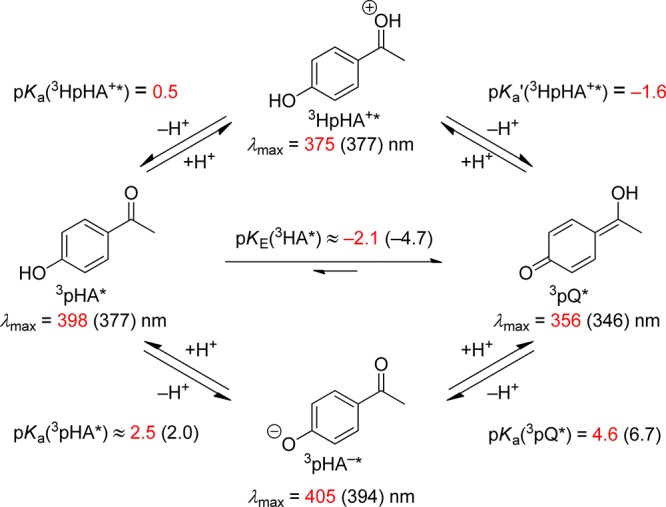

The excited-state equilibria of p-hydroxyacetophenone (24, X = H; pHA) reflect the important nonproductive reactions and the photophysical properties of pHP. A recent, detailed study89 of the primary photophysical processes of pHA and the ensuing proton transfer reactions in aqueous solution by picosecond pump–probe spectroscopy and nanosecond laser flash photolysis has provided a comprehensive reaction scheme (Scheme 18): Following fast and quantitative ISC of excited pHA, τ(1pHA*) = 3.4 ps, to the triplet state, 3pHA*, spontaneous adiabatic ionization of 3pHA* in aqueous solution occurs with a rate constant kH+ ≈ 1 × 108 s–1, yielding the triplet of the conjugate base anion 3pHA–* and, simultaneously, the quinoid triplet enol tautomer 3pQ*. The latter is formed by in-cage capture of a proton at the more basic carbonyl oxygen of 3pHA–*. The equilibrium 3pQ* ⇆ 3pHA–* + H+ is established subsequently by diffusional processes on the nanosecond time scale. The formation of 3pQ* from 3pHA* is accelerated by strong acids (via the protonated species 3HpHA+*) and is suppressed by buffer bases, which form 3pHA–* upon encounter with 3pHA*. The triplet-state proton-transfer equilibria of 3pHA* are summarized in Scheme 18.89

Scheme 18. Triplet-State Proton Transfer Equilibria of pHA (24, X = H) in Aqueous Solution (the Experimental Values for the pKa's and Absorption Maxima Are in Black and Calculated Values Are in Red). Adapted with Permission from Ref (89). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

It has been suggested89 that similar proton-transfer processes may account for the lower-than-unity quantum yields found for most pHP PPGs, especially those carrying poor leaving groups, as formation of the less-reactive pHP triplet anion and the nonreactive triplet quinoid enol represent energy-wasting pathways.85d,85e,94 Furthermore, earlier studies on pHP phosphate and carboxylate esters had documented the importance of aqueous solvents for the photochemical release of the leaving group, the rearrangement of the chromophore, and the role of the triplet state as the reactive excited state, i.e., a short-lived, quenchable triplet (ET = 71.2 kcal mol–1).82,83c Subsequent work by Wan and Corrie,95 Phillips85a,85b,96 and Givens and Wirz7,9u,83b,83c,85d,94,97 and their co-workers added a rich compilation of spectroscopic and kinetic information. Recently, the effect of ring size on the photo-Favorskii-induced ring-contraction reaction of various hydroxybenzocycloalkanonyl acetate and mesylate esters has provided new insight into the mechanism of the rearrangement.98

The Phillips group assigned electronic configurations of the key excited states, confirming the triplet state as the reactive excited state, using a combination of time-resolved transient absorption, fluorescence, and resonance Raman spectroscopy, as well as femtosecond and picosecond Kerr-gated resonance Raman spectroscopy (KTRF). An examination of the weak fluorescence from p-hydroxyphenacyl acetate (pHP OAc; 24, X = OAc) in anhydrous CH3CN revealed that the excited singlet manifold of the pHP chromophore is composed of two fluorescing states, a 1π,π* (334 nm) state and a lower lying 1n,π* (427 nm).96a The positions of the two emission bands are influenced by the solvent: in more polar, aqueous media (e.g., 90% aq. CH3CN), the two bands are shifted toward one another to 356 and 392 nm, respectively, or to an energy difference between the 1π,π* and 1n,π* states of 7.4 kcal mol–1 from an energy difference of 18.7 kcal mol–1 in anhydrous CH3CN. The shift enhances the overlap of the two states, resulting in increased vibronic coupling and consequently more efficient internal conversion to the lower 1n,π* state. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the electronic states of pHP OAc further suggest that the 3π,π* state (ET = 72.9 kcal mol–1) lies just below the 1n,π* state (ES = 75 kcal mol–1) and is sandwiched between the 1n,π* singlet and the nearby 3n,π* state (71.5 kcal mol–1).85a,95,96,99 The authors suggest that the surfaces of these three states31 merge, resulting in enhanced intersystem crossing (ΦST = 1.0) with a rate of kisc = 5 × 1011 s–1 to a nearly degenerate, “mixed 3n,π*–3π,π*” state. Their findings reaffirmed the important role of water on the photophysical and photochemical processes of pHP.96a

For instance, the picosecond (ps)-KTRF studies showed that added water made only a small difference in the growth rate of the triplet (from 7 to 12 ps) but greatly influenced its decay rate, resulting in second-order quenching of the triplet.96a A solvent change from anhydrous to 50% aqueous CH3CN caused a 100-fold diminution in the 3π,π* triplet lifetime. Phillips and co-workers attributed the large decrease in the lifetime to a leaving group effect: pHP OAc, with the poorer leaving group, had nearly the same triplet rate constant in neat, air-saturated CH3CN as that of pHP diethyl phosphate (pHP DEP, 150 ns). In the aqueous media, both triplet lifetimes (3τ ∼ 150 ns) decreased, but the pHP OAc lifetime (3τ = 2.13 ns) was five times longer than the lifetime of the more reactive pHP DEP (3τ ≈ 420 ps; 70% CH3CN).96a

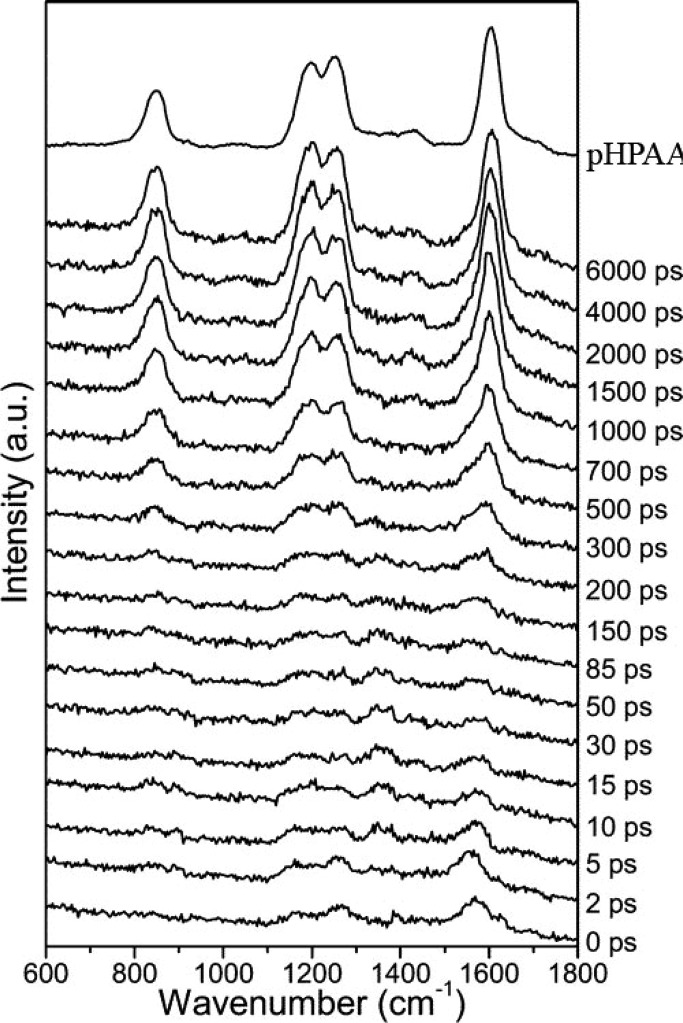

The most important mechanistic information obtained by Phillips’ group was from the picosecond time-resolved resonance Raman (ps-TR-RR) results of the 600–1600 cm–1 spectral region measured during photolysis of pHP DEP (Figure 4). Scans taken in the first few ps show only diffuse, weak absorption signals attributable to the excited singlet and triplet states of pHP DEP. At ∼300 ps, the scans show the emergence of four new bands that become prominent after 0.7–1.0 ns and by 6 ns are the only bands remaining. These four peaks precisely match those obtained with an authentic sample of the photoproduct, p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (25, R = H). This TR-RR profile sets the reaction time-constant for the rearrangement and, therefore, encompasses the period for both the release of the leaving group and the rearrangement of the chromophore. In fact, the rearrangement product is in full bloom within just 1 or 2 ns, demonstrating both that the leaving group has departed and, more strikingly, that the complex rearrangement including any intermediates that may intervene between the excited triplet state and 25 had silently formed and then expired completely, escaping ps-TR-RR detection. On the basis of a kinetic analysis of the appearance of 25, Phillips and co-workers showed that such a silent intermediate or intermediates were necessary. He assigned a candidate for the intermediate to “M” to a p-quinone methide cation that was formed by direct heterolysis of the leaving group from triplet pHP DEP. This assignment was corrected in a later study (vide infra).100

Figure 4.

Picosecond time-resolved resonance Raman spectra of pHP DEP (24, X = diethyl phosphate) obtained with a 267 nm pump and 200 nm probe wavelengths in a H2O/CH3CN (1:1) mixed solvent. The resonance Raman spectrum of an authentic sample of p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid recorded with 200 nm excitation is displayed at the top. Reprinted with permission from ref (96a). Copyright 2005 American Chemical Society.

Another significant result came from the analyses of the photolysis products from a series of pHP-substituted acetate esters in the study by Corrie, Wan, and co-workers.95 The acetates were chosen for their increasing propensity toward decarboxylation when converted to carboxy radicals by photoinduced homolysis of the corresponding arylmethyl esters. Photolysis of the pHP esters, i.e., acetate, phenylacetate, pivalate, and diphenylhydroxyacetate, however, produced only carboxylic acids in >90% yield, free of any radical-derived decarboxylation products.101 This confirmed the heterolytic pathway suggested by the groups of Givens,85d,85e Falvey,40 and Phillips.99,100

The next layer of evidence on the photo-Favorskii mechanism arose from time-resolved transient absorption (TR-TA) studies,85d which revealed two additional reactive intermediates: an early, very short-lived transient appearing on the tail of the triplet decay (Figure 5) and a later, long-lived species. The critical evidence for the first transient was obtained using pHP OTs (24, X = OTs), OMs, and DEP, all excellent leaving groups that depart efficiently and rapidly. For example, the transient formed from 3pHP DEP (lifetime, 3τ = 63 ps; in water) appears as a weak set of absorptions on the tail of the pHP triplet. These three maxima were assigned to an allyloxy–phenoxy triplet biradical (328, Scheme 19): the decay profile of 324 (3τ = 100 ps in 87% aqueous CH3CN) transforms into the profile of the slightly longer-lived transient 328 (τbirad = 500 ps).

Figure 5.

Pump–probe spectra of pHP DEP (24, X = diethyl phosphate) in 87% aqueous CH3CN. The sample was excited with a pulse from a Ti/Sa–NOPA laser system (266 nm, 150 fs pulse width, pulse energy 1 μJ). The inset shows the species spectra of 3pHP DEP and biradical 328 that were determined by global analysis of the spectra taken with delays of 10–1800 ps using a biexponential fit. Reprinted with permission from ref (85d). Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society.

Scheme 19. Refined Mechanism Based on Time-Resolved Transient Absorption Analysis85d.

The three weak absorptions of 28 were detected85d only with the best leaving groups. The bands at 340, 430, and 440 nm were taken as evidence of a phenoxy radical intermediate and thus assigned to the biradical 28. As noted earlier, kinetic analysis of the ps-TR-RR spectra by Phillips and co-workers85a,85b had suggested the intervention of an intermediate “M”, formed from the triplet state that proceeded to the final product 25. The intermediate “M” is now attributed85d to the triplet biradical 328 that is assumed to be formed adiabatically. The formation of 328 can be viewed as being extruded from 324, leaving behind the leaving group X– and a proton in the ground state, thus obeying the Wigner spin rule. The fate of 328 is ISC and closure to an as yet undetected spirodienedione 26. The resulting traditional Favorskii-like intermediate very rapidly hydrolyzes to p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, completing the formal ground state events normally proposed for the Favorskii rearrangement.102

A further, long-lived intermediate was identified as the known p-quinone methide10329 (τ = 0.3 s) that hydrates yielding p-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (30).85d The formation of small amounts of 30 is also a signature of the elusive spirodione intermediate 26, the lifetime of which appears to be shorter than its rate of formation under the reaction conditions. Thus, the validation of 26 is based solely on a requirement for the carbon skeleton reorganization and a very facile CO extrusion from 26 due to its strained bicyclic structure, and is complemented by DFT calculations.

A summary of the photo-Favorskii mechanism, as currently understood, is outlined in Scheme 19.104 The rearrangement proceeds from the chromophore’s triplet excited state (324) by a concerted departure of the leaving group and the phenolic proton generating the triplet biradical 328. Intersystem crossing of 328 gives an intermediate common to the ground state Favorskii rearrangement,102a−102c the putative cyclopropanone,86,98,102 that either hydrolyzes or decarbonylates on its pathway to the final products. The evidence provided, however, requires involvement of another intermediate, presumably the singlet allyloxy-phenoxy species 128,98,99,104b to account for the complete racemization of a p-hydroxypropiophenone analogue where the leaving group is affixed to a stereogenic α-carbon.104b This mechanism also provides a pathway for the minor photohydrolysis byproduct 24 (X = OH) that becomes predominant for the ring-contraction photoreactions of hydroxybenzocycloalkanonyl esters when ring strain discourages or prevents cyclopropanone formation.98

Position and Requirement for a p-Hydroxy Group

Unsubstituted phenacyl, which is also a PPG (section 2.1), does not undergo a photo-Favorskii rearrangement but rather reacts through a photoreduction mechanism. The p-OH modification of the phenacyl chromophore causes a profound change in the photochemical behavior. The search for alternative functional groups or other locations of the OH group on the phenacyl chromophore that would accommodate a Favorskii rearrangement pathway has met with very little success. Only 2-hydroxyphenacyl esters were shown to release carboxylic acids.73m-Hydroxyphenacyl acetate and a 5-hydroxy-1-naphthacyl analog were unreactive under photo-Favorskii conditions.105

Electron donors such as p-methoxy and o-methoxyphenacyl have been tested as early as the seminal report of the photo-Favorskii rearrangement by Anderson and Reese.87 For these examples, the photo-Favorskii rearrangement competes with photoreduction, forming mixtures of the corresponding methoxyacetophenones and phenyl acetates. In the early 1970s Sheehan and Umezawa developed the p-methoxyphenacyl derivatives as a PPG for photolysis in dioxane or ethanol, producing reduction products.39,106 Givens and co-workers later showed that the reaction in methanol or t-butanol (hydroxylic solvents) did undergo the Favorskii rearrangement as the major pathway, yielding p-methoxyphenylacetates. The competing photoreduction pathway was also evident from the significant proportion of reduction to p-methoxyacetophenone.107 Phillips and co-workers showed that p-methoxyphenacyl diethyl phosphate undergoes a rapid heterolytic cleavage that results in deprotection and formation of a solvolytic rearrangement product.108

Other electron-donating substituents have met with even less success toward the rearrangement of the chromophore.82 Although several p-methoxy and other p-alkoxy analogues have been successfully employed as PPGs for the release of carboxylates,39,106,109 phosphates,82,107 carbonates, and carbamates,110 they do not lead to rearrangement of the chromophore.

Nature of the Leaving Group

The most efficacious leaving groups are conjugate bases of moderate to strong acids, e.g., sulfates,85d,93 phosphates7,9u,82−85,99 (thiophosphate),100,111 carboxylates,7b,9u,85a−85c,93−95,97b,97c,112 phenolates,9u,93 and thiolates.111,113 In general, quantum yields monotonically decrease with an increase in the acid leaving group’s pKa (Table 4), conforming to a Brønsted leaving group relationship (βLG), which correlates the pHP release rate constant with the Ka of the leaving group. A correlation of the log of the rate constants (log kr), derived from the quantum yields and the triplet lifetimes as kr = Φ/3τ (see Table 4 footnote b for details), with the pKa of the leaving groups gave βLG = −0.24 ± 0.03.9u,114

Table 4. Disappearance Quantum Yields, pKa’s, and Rates of Release for Different Leaving Groups (X) for pHP X (24) Arranged According to the pKa of HX.

| X (released substrate) | λmax (log ε)a (pHP X) | pKa (HX) | Φ–Xb | kr/108 s–1c | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mesylate | –1.54 | 0.93 | 50 | (85d, 93, 114) | |

| tosylate | –0.43 | 1.00 | 100 | (85d, 93, 114) | |

| OPO3Et2 | 271 (4.18) | 2.12 | 0.4 | 12. | (82, 85a−85c, 96a, 99, 114) |

| Glu | 273 (3.94) | 4.33 | 0.14 | 1.9 | (83c, 97b, 97c) |

| Ala·Ala | 282 (4.12) | 3.4 | 0.27 | 1.8 | (83c, 112a) |

| bradykinin | 282 (4.07) | 3.4 | 0.22 | 1.8e | (83c, 112a) |

| p-CF3C6H4CO2– | 3.69 | 0.2 | 3.2 | (9u, 93, 114) | |

| formate | 3.75 | 0.94 | 14 | (9u) | |

| benzoate | 4.21 | 0.32 | 2.8 | (9u, 73, 85c, 93, 114) | |

| acetate | 279 (4.09) | 4.76 | 0.4 | N/Af | (85a−85c, 95, 96) |

| GABA | 282 (4.16); 325 | 4.76 | 0.2 | 6.2 | (83c, 85e, 94, 97b, 97c) |

| RPO3S–d | 5.3 | 0.21 | N/A | (111) | |

| OPO3–2 | 280 (4.48) | 7.19 | 0.38 | N/A | (82) |

| GTP | 7.4 | N/A | N/A | (91, 92) | |

| ATP | 253 (4.3); 320 (2.70) | 7.4 | 0.37 | 68 | (82, 83c, 90) |

| p-CNC6H4O– | 7.8 | 0.11 | 0.76 | (9u, 93) | |

| RS–d | 8.4 | 0.085 | N/A | (111, 113, 115) | |

| C6H5O– | 9.89 | 0.04 | 1.0 | (9u, 93) | |

| HO– | 15.7 | <0.01 | N/A | (95) |

In H2O unless otherwise noted.

Appearance efficiencies were identical within experimental error (±5%). See Table 5 for examples.

The rates are derived from several sources and conditions vary. The H2O content was between 10% and 50%, causing small variations in the quantum yields/rates (see text).

Decaging of the catalytic subunit C199A/C343A of PKA (protein kinase A) at Thr-197.111

Assumed to be the same as the model, Ala·Ala.

N/A = not available.

The good quantum efficiencies and high appearance rate constants of the free substrates (kapp = 1/3τ) make the pHP protecting group attractive for quantitative and mechanistic studies in biology and physiology.9u Other beneficial features include good aqueous solubility and stability, the ease of synthesis, the biologically benign quality of the pHP group and its photoproducts, and the lack of quenching by adventitious O2 in aqueous solvents.

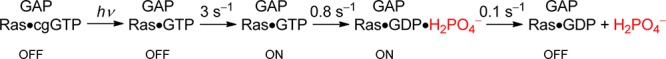

ATP and GTP release from the pHP-protected nucleotides has been extensively investigated, resulting in pHP becoming the “phototrigger” of choice for fast kinetic studies of the enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis by Ras and Rap GTPase activating proteins (GAP proteins).90−92 The phototrigger methodology for activating hydrolysis by photodeprotection of GTP or ATP is rapid (an appearance rate constant kapp = 1/3τ = 1.6 × 1010 s–1 as measured for pHP diethyl phosphate in water99) and was assumed by the authors to be sufficient for measuring the kinetic rate constants for most subsequent binding and hydrolysis steps for the nucleotide.116 Thus, the pHP protecting group provides researchers with a powerful arsenal for fast kinetic mechanistic investigations.

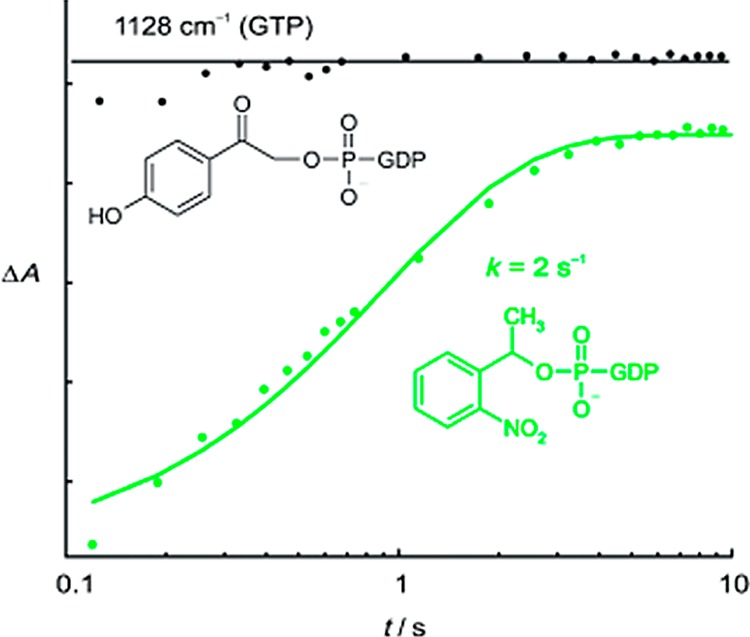

Kötting, Gerwert, and co-workers, for example, compared the release rates for pHP versus NPE (1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl; section 3.2) GTP esters (Figure 6).116 The rise time for photorelease of GTP from pHP GTP was too fast to record by their TR-FTIR instrument (τrise = 10 ms), whereas they were able to monitor the GTP appearance rate constant (kapp = 2 ± 1 s–1, Figure 6). They then exploited the rate advantage of pHP GTP to study the catalytic GTP hydrolysis by Ras GTPase and other GAP-based catalytic hydrolysis mechanisms.

Figure 6.

Formation of GTP measured as its Mg2+ complex at 1128 cm–1 from pHP-caged GTP (black) is already complete at the first data point. Formation of GTP from NPE-caged GTP (green) takes place more slowly with a rate constant of 2 s–1 because the rate-limiting step is the release from a ground-state hemiacetal intermediate (section 3.2), an inherently slow process on the time scale necessary for the kinetic measurements reported here.116 Reprinted with permission from ref (116). Copyright 2007 Wiley and Sons.

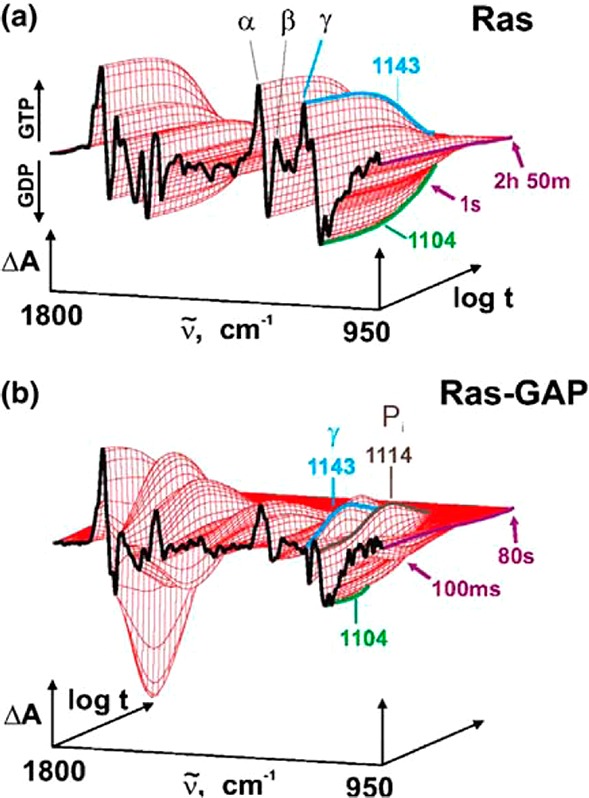

In pursuing the mechanistic pathway for Ras GTPase catalysis, comparisons of the FTIR spectra of individual α-, β-, and γ-18O-labeled and unlabeled phosphates of GTP, inorganic phosphate (Pi), and GDP hydrolysis products as well as 13C and 14N-labeled site-specific amino acids provided detailed information on both bonding and environmental changes at the enzyme active site. TR-FTIR was then employed to monitor the changes in binding and the evolution and decay of the intermediates during hydrolysis as well as the product-release step and to determine the rate constants.92 Figure 7 illustrates the power of TR-FTIR to resolve the changes in structure and binding at the labeled sites as a function of reaction time. Scheme 20 summarizes the key steps for the hydrolysis, beginning with initial binding of free GTP and ending with the release of inorganic phosphate (Pi) from the enzyme “pocket”, in the rate-limiting step that controls signal transduction. In contrast, with NPE GTP as the phototrigger, only the (last) rate-limiting step could be determined.92

Figure 7.

(a) Difference spectra by TR-IR absorption of the intrinsic Ras-catalyzed GTPase reaction. A single exponential function by global fit analysis shows the change from Ras GTP to Ras GDP at 1143 cm–1. (b) TR-IR absorbance difference spectra for the GAP-catalyzed GTPase by Ras. Two intermediates are seen by the fit of three exponential functions at 1143 and 1114 cm–1. The appearance of GTP at 1143 cm–1 arises from pHP-caged GTP followed by GTP hydrolysis. Protein bound Pi appears at 1114 cm–1, which is subsequently released as the rate-limiting step (Scheme 20). Reprinted with permission from ref (92a). Copyright 2004 Elsevier B. V.

Scheme 20. Rate Constants and Mechanism for Ras GTPase (GAP) Hydrolysis of GTP Derived from the Initial Photorelease of GTP from pHP-Caged GTP (the Nonsignaling “OFF” to the signaling “ON” States Are Shown)92b.

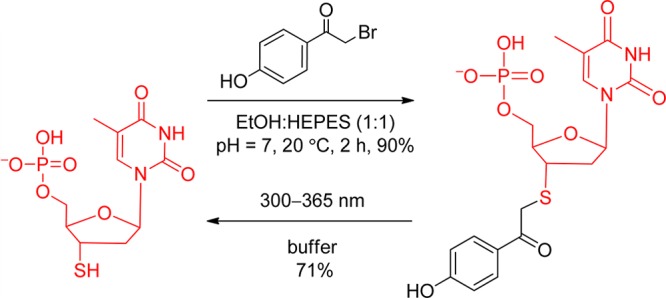

For thiolates, the nucleophilicity of the leaving group is especially noteworthy because leaving groups can readily be protected through in situ derivatization. pHP Br can be added directly to thiols and thiophosphates, even in the presence of other nucleophilic groups on the substrate or in the media. Direct derivatization of thiols and thiophosphates has been exploited for peptides and proteins that possess exposed cysteine and thiophosphate residues, an especially useful feature when the thiol group is an integral part of the catalytic center.115 Model reactions where pHP Br was reacted directly with 3′-thiodeoxythymidine, cysteine, and glutathione produced the corresponding pHP thioethers in 80–90% yields in buffered solutions (Scheme 21). Deprotection by irradiation at 300–365 nm releases the thiol in 60–70% yield, performing essentially as a protection–deprotection switch.

Scheme 21. Reversible Protection–Deprotection of a Thiol on 3′-Thiodeoxythymidine with pHP Br115.

The switch sequence was employed by Pei and co-workers113 and by Bayley and co-workers.111 Pei and co-workers inhibited the phosphorylation of a cysteine located at the active site of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTK) by direct addition of pHP Br. The phosphorylated cysteine turned “OFF” PTK, a common type of suicide inhibition used with other phenacyl halides. However, photolysis of the pHP thiolates freed the catalytic cysteine unit, turning PTK back “ON”. Interestingly, the protection step was regioselective for blocking only Cys 453, the cysteine at the catalytic site, and none of the other three available cysteine residues.

The protection–deprotection sequence was also reported for the C subunit of protein kinase A (PKA) at Thr-197 and for a thiophosphorylated tyrosine (Y) on a model 11-aa peptide, EPQYEEIPILG, by Bayley’s group.111 Two PPGs were compared: reacting thiophosphate with o-nitrobenzyl bromide (75%) and protection with pHP Br (90%). Deprotection proved more difficult with the o-nitrobenzyl (oNB, section 3.1) thioether because the nitrosobenzaldehyde as a side-product reacted with the newly exposed thiol, causing inhibition. The quantum yield for the reaction was modest (0.37). pHP deprotection was more efficient (Φ = 0.56 to 0.65) and the 70% recovery of the activity was higher because there were no competing reactions of the byproducts with the exposed thiophosphate. This methodology was transferrable into in vitro cell machinery by simply importing the pHP Br into human B cells.111

Substituent Effects on the Chromophore

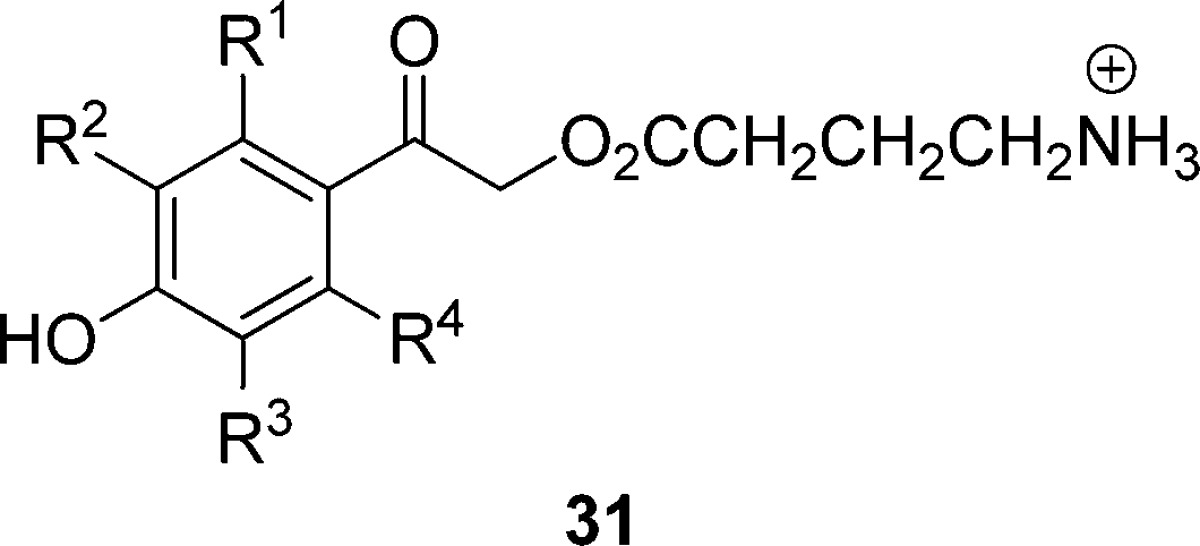

Very recently, a number of new ortho- and meta-substituted p-hydroxyphenacyl PPGs were introduced to extend the versatility by absorbing at longer wavelengths and by altering the solubility properties. The influence of substituents on the chromophore’s physical, spectral, and mechanistic capabilities, by necessity, became the target of several studies. GABA was selected as the common leaving group because it imparts good aqueous solubility and is biologically significant. Quantum yields of a representative collection of 2- and 3-substituted pHP GABA (31, Table 5) vary only modestly for these substituents. meta-Electron donors such as 3-OCH3 generally display lowered quantum yields whereas electron-withdrawing groups such as 3-CF3 and 3-CN often give rise to slightly increased yields. The rate constants for release are consistently high, in the range of 109 s–1.94

Table 5. Effects of Substituents and pKa on Quantum Yieldsa for the Substituted pHP GABA 31 in Unbuffered H2O;b Entries Are Arranged in the Order of Decreasing pKa of the Substituted pHP Chromophore94.

| 31 | pKa | Φdisc | ΦGABA | Φ (25)d | Φdis (Ac or DEP)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,5-CH3 | 8.2 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.13 | |

| 3-CH3 | 8.1 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.13 | |

| 2-CH3 | 8.0 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 3-OCH3 | 7.9 | 0.07 | 0.06 | NDe | 0.39 (DEP) |

| R1–R4 = H | 7.8 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.30 (Ac) |

| 0.40 (DEP) | |||||

| 3,5-OCH3 | 7.8 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ND | 0.44 (DEP) |

| 2-F | 7.2 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.26 | |

| 2,6-F | 6.8 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |

| 3-F | 6.7 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| 3-OCF3 | 6.5 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | |

| 2,3-diF | 5.9 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.22 | |

| 2,5-diF | 5.7 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.2 | |

| 3-CF3 | 5.5 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.14 | |

| 3,5-F | 5.3 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.1 | |

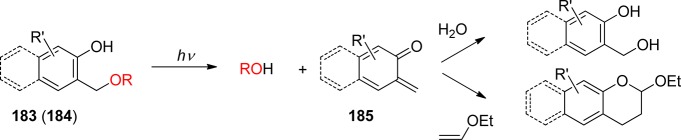

| 3-CN | 5.2 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.17 (Ac) |

| 2,3,5-triF | 4.5 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | |

| tetra-F | 3.9 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

All runs were low conversions to products (<5%); standard deviations were < ±0.02.

Unbuffered 18 MΩ ultrapure H2O.

Disappearance quantum yield when GABA is the leaving group.

Quantum yield for the substituted phenylacetic acid (25).

Disappearance quantum yield when Ac (acetate) or DEP (diethyl phosphate) is the leaving group.

ND = not determined.94

Certain groups, m-nitro, m-OH, and m-acetyl, when present on the chromophore completely quench the photorearrangement reaction.94

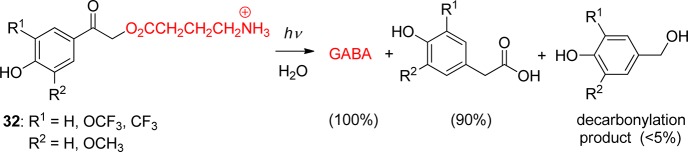

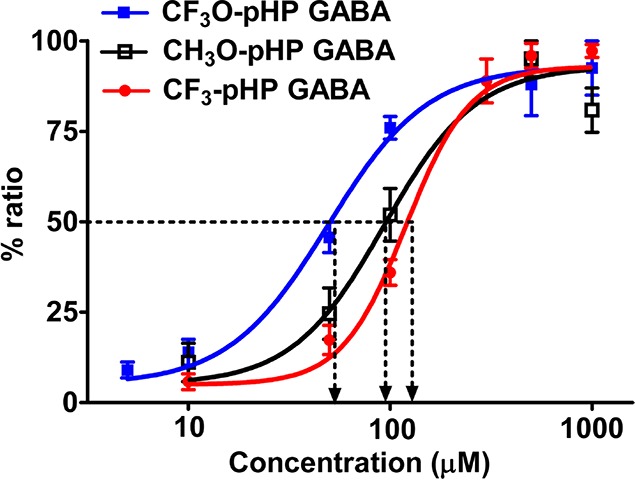

In addition to GABA, there are many other small-molecule and amino acid neuroactive agonists and antagonist with carboxylic acid end-groups. Although carboxylate release is generally less efficient than those of phosphates and tosylates, caged carboxylates find useful applications in neurobiology and neurophysiology, taking advantage of the rapid rate of release and the unreactive, benign qualities of 25 photoproduct vis-à-vis o-nitrobenzyl-based PPGs (section 3.1).92,97b,97c,117 Substituent modification of the pHP derivative 32, such as the 3-CF3 and 3-OCH3 pHP GABA compounds shown in Scheme 22, expands and extends the versatility of the PPG methodology. Here, the relative efficacy of modified pHP GABA to stimulate the GABAA receptor is documented in Figure 8.

Scheme 22. m-Electron-Donor and -Acceptor Group Compatibility for Photorelease of GABA from m-Substituted pHP GABA97b.

Figure 8.

Comparison of EC50’s for GABAA receptor activation by rapid photolysis of pHP (24) GABA. Dose–response curves for 3-CF3O-pHP GABA (blue, n = 7 neurons), 3-CF3-pHP GABA (red, n = 6 neurons), and 3-CH3O-pHP GABA (black, n = 6 neurons) with population data of peak currents normalized to the maximum peak response. EC50 and Hill’s coefficient values were as follows: 3-CF3O-pHP GABA, 49.2 μM, 1.8, n = 7 neurons; 3-CH3O-pHP GABA, 93.4 μM, 1.9, n = 6; and 3-CF3-pHP GABA 119.8 μM, 2.73, n = 6. Reprinted with permission from ref (97b). Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

The effect of m-methoxy, trifluoromethoxy, and trifluoromethyl groups on pHP-caged GABAs were tested for their efficacy to release GABA in whole-cell patch-clamp studies on neurons in cortical slices. Local photolysis with short UV light pulses (10–50 ms) delivered through a small-diameter optical fiber produced transient whole-cell inward currents from released GABA.97b

Effect of Media pH and pHP pKa

Because the ionization of substituted pHP derivatives to their conjugate bases changes during irradiation in unbuffered media (Figure 3), the pH effects on the pHP photochemistry were examined (Table 6). The extent of quinone methide formation is altered also by the pH and the substituents on the chromophore (Scheme 18).

Table 6. Substituent Effects on the Quantum Yieldsa As a Function of pH for GABA Release from 31 at 300 nm in Buffered CH3CN–H2O; Entries Are Arranged According to Decreasing pKa of the Substituted pHP GABA94.

| pHP GABA | pKa | Φdis pH 5.0b | Φdis pH 7.3c | Φdis pH 8.2c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,5-(CH3)2 | 8.2 | N/A | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| 3-CH3 | 8.1 | N/A | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| parent | 8.0 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.09 |

| 2-F | 7.2 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| 3-F | 6.7 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| 3-OCF3 | 6.5 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 3-CF3 | 5.5 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| 3,5-F2 | 5.3 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| 3-CN | 5.2 | 0.21 | 0.33d | 0.19e |

| 2,3,5,6-F4 | 3.9 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

Standard deviations were < ±0.02.

0.01 M ammonium acetate.

0.01 M HEPES, 0.1 M LiClO4, pH 7.3.

0.01 M ammonium acetate, pH 7.

0.01 M ammonium acetate, pH 9.

Raising the pH above 8 lowers the quantum yields, reflecting the lower reactivities of the conjugate bases (Table 6). In all cases, the quantum yields were maximal in neutral or slightly acidic conditions but dropped at higher pH. As shown for the pKa’s of the corresponding acetophenones, there is a substantial substituent effect on the pKa, which is manifested in a pronounced UV–vis spectral change (see Figure 3). The prominent π,π* transition at 260–280 nm for neutral p-hydroxyacetophenone is shifted to 320–340 nm, the π,π* transition for the conjugate base, and the absorptivity nearly doubles.

The resultant interplay of pKa of the substituted pHP derivative and the pH of the solution influence the quantum yield as illustrated with 3-CF3 pHP GABA. The quantum yields at pH 5 (Φ = 0.24) decrease to half of their value when the pH is 7.3 (Φ = 0.12) and a third at pH 9.2 (Φ = 0.08). Product yields remain the same at all three pH values, demonstrating that the photo-Favorskii rearrangement is still the major reaction pathway for the conjugate base. These initial results on substituted pHP protecting groups show promise for extending their use in chemistry, physiology, and biochemistry.

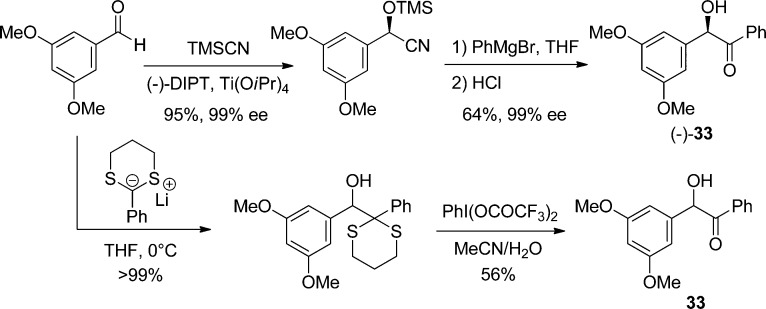

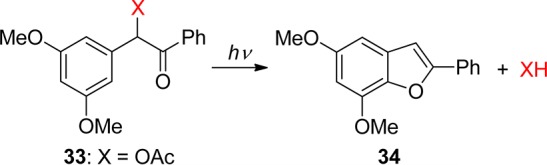

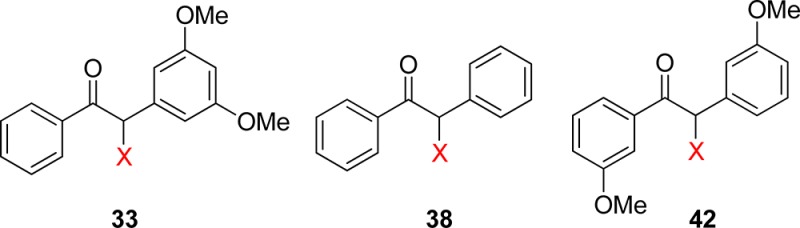

2.4. Benzoin Groups

In the course of their ground-breaking studies on benzoin (desyl alcohol; Figure 1; Scheme 2, entry 6) acetates, Sheehan and Wilson determined that the 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzoin (DMB, 33, X = OAc) derivative performed best as a PPG of acetate.4,118 The reaction proceeded in an extraordinarily smooth fashion as illustrated by the spectra shown in Figure 9. The expected product 2-phenyl-5,7-dimethoxybenzofuran (34, DMBF, Scheme 23) was formed in quantitative yield, and the quantum yield was determined as 0.64 ± 0.03. The authors noted that the photocyclization of DMB acetate was not quenched by either naphthalene or neat piperylene, and they concluded that the reaction proceeds from the excited singlet state or an extremely short-lived triplet state.

Figure 9.

Course of the photolysis of DMB (33) acetate to DMBF (34) in acetonitrile (Scheme 23); irradiated in a photochemical reactor at 360 nm. Reprinted with permission from ref (118). Copyright 1971 American Chemical Society.

Scheme 23. Photocyclization of DMB Acetate4,118.

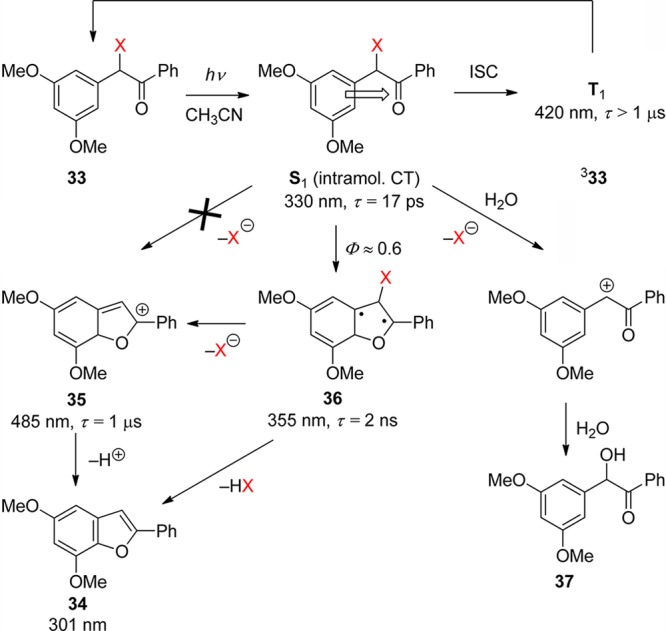

It has taken substantial efforts to elucidate the detailed mechanism of this reaction, and a clear picture (Scheme 24) has emerged only in recent years. Time-resolved work on DMB derivatives was performed by the groups of Trentham,119 Wan,120 Simon,121 Wirz,122 and Phillips.123 By ns-LFP of several DMB carboxylate esters (33, X = OCOR) in dry acetonitrile, Shi, Corrie, and Wan120 observed a strong transient absorption at 485 nm that was formed within the lifetime of their laser pulse (∼10 ns) and decayed with a lifetime of 1 μs. This transient was assigned to the cyclohexadienyl cation (35, Scheme 24). An additional transient absorption with μs lifetime was observed at λmax = 330 and 420 nm. Introduction of air resulted in a faster decay of this transient but did not affect the lifetime of the 485-nm transient or the yield of the final product 34 (DMBF). The (330, 420)-nm transient was therefore assigned to the (nonreactive) triplet state of the DMB esters (333). These assignments have stood the test of time. However, subsequent studies with better time resolution showed that heterolytic cleavage of the excited singlet state is not, as claimed,120 the primary photochemical step of DMB esters, and that the cyclohexadienyl cation is not even an intermediate along the predominant reaction path releasing the substrate HX.122,123b

Scheme 24. Mechanism of the Photocyclization of 3′,5′-Dimethoxybenzoin (DMB) Derivatives (X = OCOR, OPO(OEt)2, F)122,123b.

Pump–probe experiments of DMB acetate and fluoride (33, X = OCOMe, F) with picosecond time resolution revealed a preoxetane biradical intermediate 36, λmax = 355 nm, that was formed from the singlet state, τ = 17 ps, and decayed with a lifetime of 1–2 ns.122 The biradical 36 was shown to be the precursor of the cyclohexadienyl cation 35, λmax = 485 nm, the lifetime of which was found to be strongly reduced by the addition of water to the acetonitrile solution, kw = 6 × 106 M–1 s–1. This work proved that the reactive intermediate is the biradical 36, which releases the DMB-caged ligands HX on a time scale of 1–2 ns, largely independent of the leaving group ability of X. Thus, DMB is an excellent PPG for the kinetic investigation of fast processes such as protein folding.124 The existence of a biradical intermediate 36 had been proposed earlier on the basis of preparative work by Rock and Chan, who also showed that a benzoin side-product (37) is formed in aqueous solution.125 Otherwise, the reaction proceeds cleanly and efficiently in both polar and apolar solvents.

In the most recent time-resolved study of DMB phosphate (X = OPO(OEt2), Phillips and co-workers123b investigated the ultrafast primary photophysical processes by absorption spectroscopy and provided evidence for the formation of an intramolecular charge-transfer singlet state (S1, τ = 14 ps), as had been proposed earlier.120 Moreover, using nanosecond time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy, they proved that the final product 34 (DMBF) is largely formed within the time resolution (∼10 ns) of their setup. It was postulated that DMBF is formed by concerted HX elimination directly from the biradical 36, largely independent of the solvent, and that the cyclohexadienyl cation is not a precursor of DMBF. Nevertheless, earlier ns-LFP experiments had shown that a second, minor wave of DMBF is also released from the cyclohexadienyl cation on a time scale of 1 μs in dry acetonitrile.122,126 Finally, Phillips and co-workers127 reported extensive CASPT2 calculations in support of the ultrafast primary processes that they had observed by transient absorption.123b

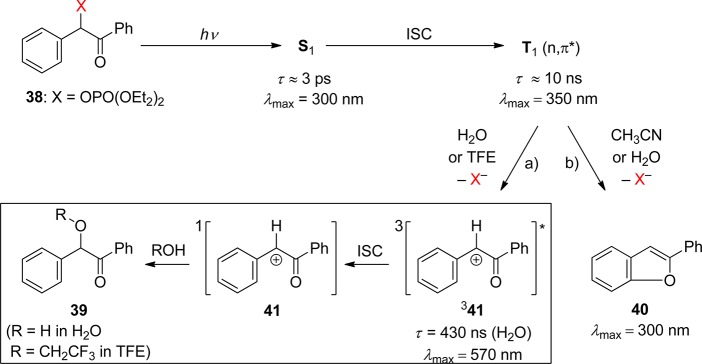

The photoreaction of parent benzoin derivatives follows an entirely different course (Scheme 25). Givens and Matuszewski reported that irradiation of benzoin diethyl phosphate (38, X = OPO(OEt)2; BDP) in acetonitrile proceeds cleanly and quantitatively with a quantum yield of 0.28.128 Stern–Volmer quenching studies with either piperylene or naphthalene indicated that the reaction proceeds via the triplet state with a lifetime of a few nanoseconds. A study using ps-pump–probe and ns-LFP of BDP was reported by Rajesh et al.129 The assignment of the observed transient intermediates was assisted by DFT calculations. Two competing reaction paths of diethyl phosphate elimination proceed from the triplet state of BDP: Reaction via path (a) yielding 39 (R = H or CH2CF3) predominates in water and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE), while exclusively path (b) yielding 2-phenylbenzofuran (40) is followed in acetonitrile. Path (a) proceeds via a transient intermediate, λmax = 570 nm, that was attributed to the triplet state of the carbocation formed adiabatically from 338 by heterolytic release of the phosphate anion. A triplet multiplicity of the cation 341 was indicated by the observation of oxygen quenching, kq ≈ 1 × 109 M–1 s–1, and by the fact that its lifetime in water (430 ns) is similar to that in the much less nucleophilic solvent TFE (660 ns). This indicated that the rate-determining step for hydrolysis of the triplet cation is ISC to the singlet ground state. For both pathways, the reactive intermediate releasing diethyl phosphate is thus the excited triplet state with a lifetime of about 10 ns.

Scheme 25. Mechanism of the Photorelease of Diethylphosphate from 38 (X = OPO(OEt)2) in Various Solvents129,130.

The assignments of the observed transients have been largely confirmed and corroborated by Phillips and co-workers using fs-pump–probe and ns-resonance Raman spectroscopies as well as DFT calculations.130,131 The formation and decay of the cation intermediate in 75% aqueous acetonitrile solution was measured by ns-time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy. An essential difference from the previous study129 is that two cationic species appeared in sequence: The first of these (main feature at 1560 cm–1), which was formed within the rise time of the instrument (∼10 ns), was attributed to the triplet cation 341 with optical absorption at 570 nm. The 1560 cm–1 signal decayed with a lifetime of 100 ns, forming another transient species (main feature 1626 cm–1), which decayed with a lifetime of 200 ns and was attributed to the singlet ground state of the cation (41). The lifetime of the short-lived species (100 ns, 1560 cm–1) was reduced by purging the solution with oxygen. It is hard to reconcile the observations by optical LFP129 and Raman spectroscopy,130 and more work may be required to settle this point.

Very soon after the initial reports on PPGs, Sheehan published the photoconversion of substituted benzoin esters into benzofurans with the concomitant loss of acetate (38, X = OAc, Scheme 23).4,132 Several years later he exploited this reaction as a PPG for carboxylic acids.118

The benzoin group remained remarkably underutilized for two decades, until Baldwin and co-workers used it for the photorelease of phosphates. Thus, phosphate derivatives of 33, 38, and 42 (X = OPO32–) were investigated, and all three released inorganic phosphate upon irradiation with a laser at 308 or 355 nm with appreciable yields (35–55% under continuous irradiation).106a

Although, as Sheehan and co-workers had already pointed out in their initial studies, the 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzoin derivative 33 was the most reactive, easier synthesis of the symmetrical benzoin derivative 38 made it equally attractive. Doubts on the purity of the substrates prompted another study, which provided a reliable preparative method for the phosphate (X = OPO32–) and esters (X = OAc), rendering 33 an ideal candidate for a fast and clean release of phosphates.119 The same PPG was used to protect the 3′-phosphate of nucleotides.133

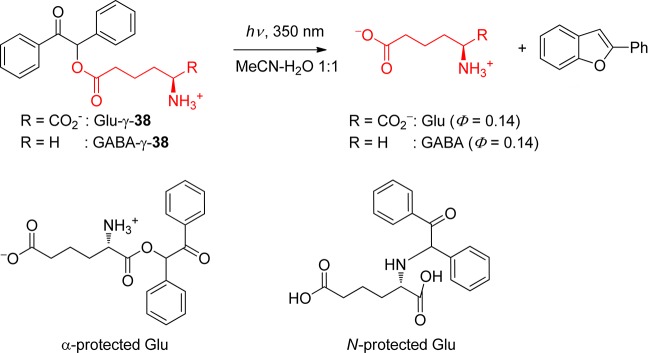

DMB phototriggers have been extensively used for applications in drug delivery,134 muscle relaxation studies,119 lithography,135 biochip fabrication,133,136 protein folding and unfolding,124 or for masking a photochemical switch.137 cAMP derivatives of 38 were also able to release cAMP upon photolysis.107b,107c,138 Likewise, glutamate and GABA were released from 38, with the PPG at the γ-carboxyl group (Scheme 26). However, neither the α- nor the N-protected derivatives of 38 led to a clean photolysis.139

Scheme 26. Release of Glutamate and GABA from Benzoin Derivatives107b,107c,138.

Various types of leaving groups, such as amines, can be released from derivatives of 3′,5′-dimethoxybenzoin (33).140 Although there are no photochemical reasons preventing the use of a whole array of leaving groups, the sometimes delicate preparation of certain derivatives has to be considered. α-Ketol rearrangement can scramble the position of the methoxy groups on both arenes, and an activated ester precursor can react intramolecularly into an inert cyclic product. However, carbamates could be prepared by the reaction of 33 (X = OH) with cyclohexylisocyanate or by preparing the p-nitrophenyl mixed carbonate.140c,141 They were utilized for the photogeneration of bases in films.142 In the solid state, 33 released cyclohexylamine with Φ = 0.067 (254 nm), 0.08 (313 nm), 0.054 (336 nm), and 0.028 (365 nm). The liberated benzofuran side-product absorbs at longer wavelengths; this photobleaching is crucial for applications in thick films, allowing light to reach deeper layers. Again, the methoxy groups on the benzylic side were found to be important for the reactivity; other substituents on the benzoyl side also had an impact, but less significant. An alternative preparative method was devised by Pirrung and Huang, where the benzoin is allowed to react with carbonyl diimidazole (preactivated by methyl triflate), followed by the amine.140b Primary amines, however, failed to give the desired carbamate and gave instead the cyclic product mentioned above.

The activation procedure with carbonyldiimidazole proved to be efficient also for the preparation of carbonates, thus allowing 33 to release alcohols (X = OCOOR). It was used to protect the 5′ primary alcohol of nucleotides,135b various kinds of alcohols, or benzylthiol.136

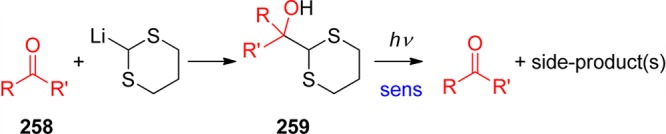

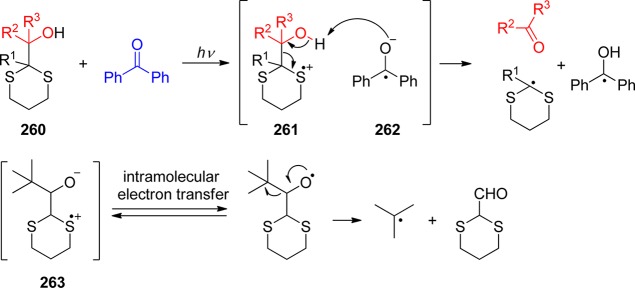

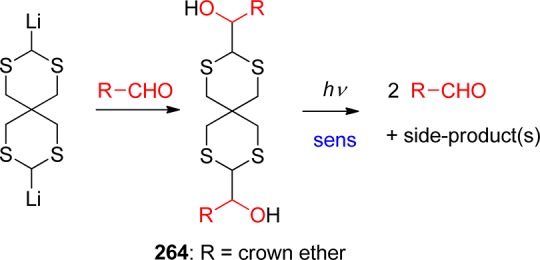

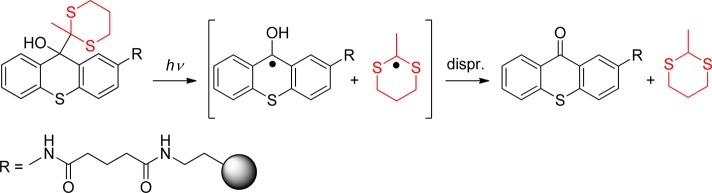

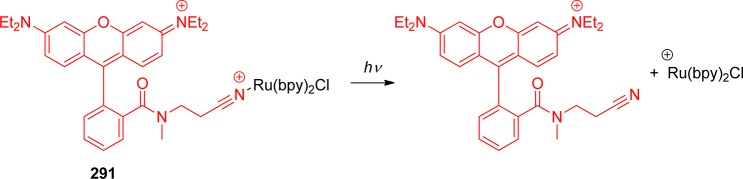

The protection of chiral molecules (such as nucleotides) can be problematic with DMB, because it also bears a stereogenic center. Access to an enantiopure derivative of 33 would therefore be highly desirable. Enantioselective syntheses of 33 have been published, using enantiopure TMS-protected cyanohydrins generated either by asymmetric catalysis or enzymatic resolution (Scheme 27).143 Addition of an aryl-Grignard reagent to the nitrile, followed by acidic hydrolysis, leads to chiral unsymmetrical benzoin. When asymmetry is not required, more straightforward routes are available, in particular by using a dithiane as a benzoyl anion equivalent.144 This method was used to prepare derivatives of DMB that could release a phenol (ubiquinol),145 or as a linker for peptides.144 This dithiane route was cleverly exploited in a safety-catch strategy, where keeping the carbonyl function masked prevented any photolytic activity, whereas hydrolysis restored the initial sensitivity.146 A related strategy was recently proposed, where the carbonyl group is masked as a dimethyl ketal, which can be smoothly hydrolyzed into the photolabile benzoin derivative (3% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in CH2Cl2, 5 min).147

Scheme 27. Preparation of Racemic and Enantiopure 3′,5′-Dimethoxybenzoin (DMB; 33, X = OH)143,144.

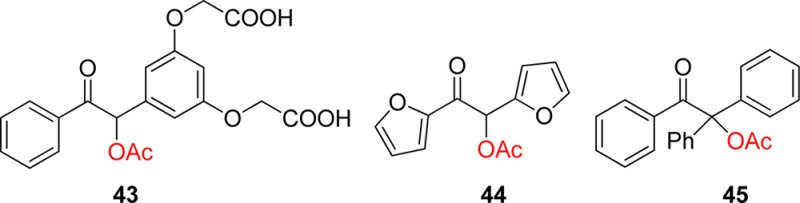

As will be mentioned in the next section on nitrobenzyl derivatives (section 3.1), water-insolubility is a major issue when the release of bioactive material is sought under physiologic conditions. Thus, the water-soluble derivative 43 was prepared. The possibility of carrying out the photolysis in aqueous solution gave an additional hint in favor of the cationic mechanism (Scheme 24), as the free DMB alcohol was also observed as a side-product, in addition to the expected benzofuran.125

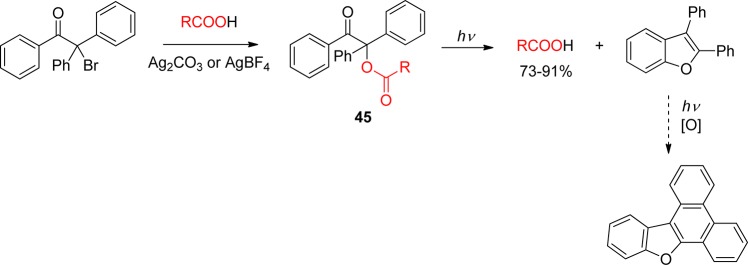

Attempts to improve the reactivity by further modification of the main core were proposed, such as the replacement of both aromatic groups by the 2-furyl moiety. Dipeptide esters of this “furoin” analogue 44 indeed could be deprotected, but in lower yields than the parent structure.148 On the other hand, esters of the achiral 1,2,2-triphenylethanone 45 proved to be as reactive as 33 (DMB) (Scheme 28).149 The diphenylbenzofuran side-product continues to react under irradiation to form a more conjugated heterocycle.

Scheme 28. Photolysis of 1,2,2-Triphenylethanone Esters149.

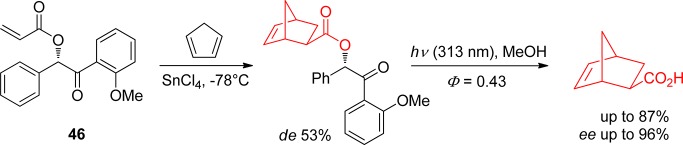

Chirality in the PPG is not necessarily a problem and can actually be exploited. Klán and co-workers used enantiopure acrylate derivatives as a photoremovable chiral auxiliary (PCA). Thus, the acrylate 46 reacted in a highly enantioselective manner with cylclopentadiene in the presence of a Lewis acid, and the cycloadduct was photolyzed (Φ = 0.43) at 313 nm to give the Diels–Alder exo product as the main diasteroisomer, with enantiomeric excessed (ee’s) up to 96% (Scheme 29).150 The photochemistry of several benzoin derivatives is summarized in Table 7.

Scheme 29. Use of a Chiral Benzoin as a Photoremovable Chiral Auxiliary150.

Table 7. Photolysis Quantum Yields for Benzoin Derivatives.

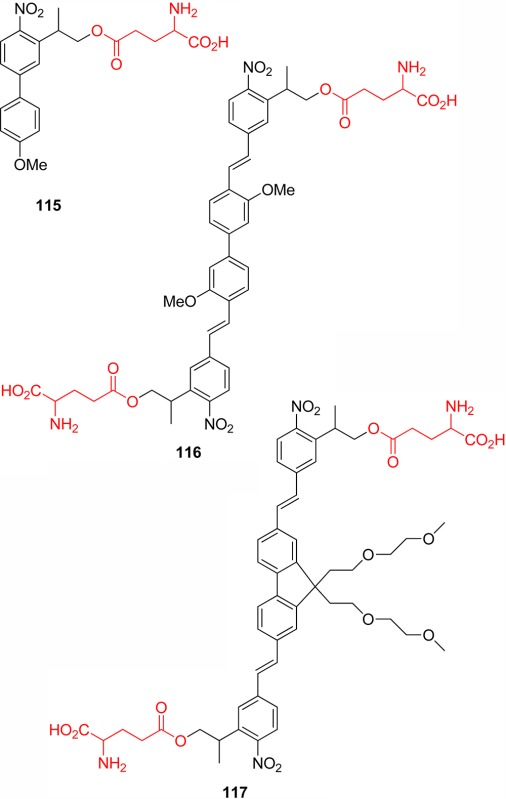

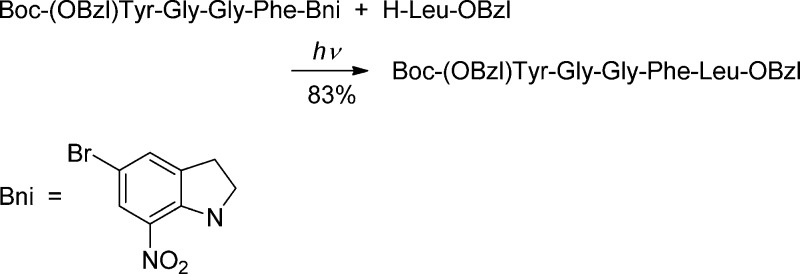

3. Nitroaryl Groups

3.1. o-Nitrobenzyl Groups

o-Nitrobenzylic derivatives have been widely used despite their disadvantages. They were proposed as general PPGs in 1970,3 but there were earlier reports on their photochemistry,151 including the one on the photoisomerization of o-nitrobenzaldehyde into the corresponding nitrosobenzoic acid.152

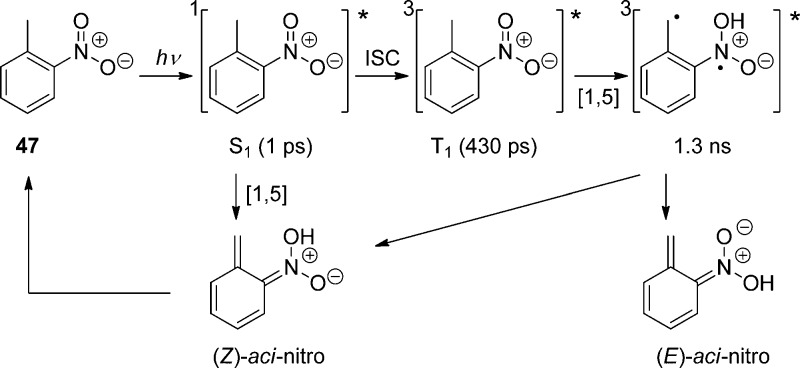

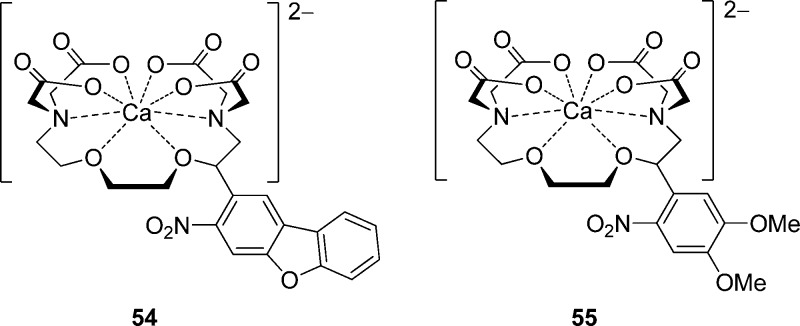

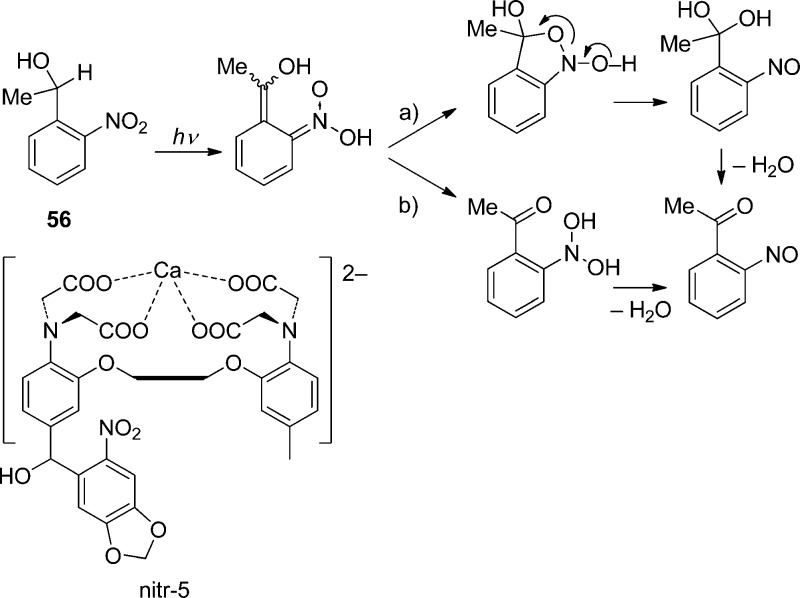

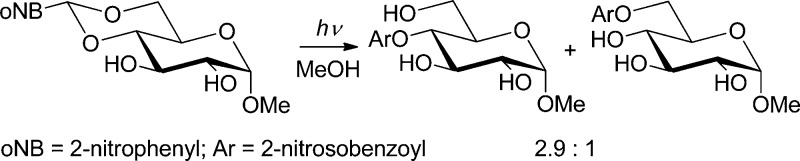

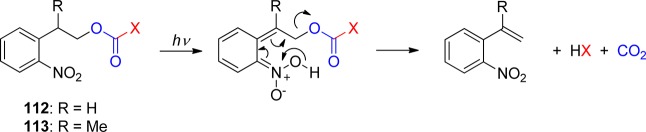

Hydrogen transfer from the o-alkyl substituent to the nitro group forming an aci-nitro tautomer in the ground state is commonly taken to be the primary photoreaction of o-alkylnitroarenes. Parent o-nitrotoluene (47, oNT, Scheme 30) and several derivatives have been studied by time-resolved spectroscopy.153 The most recent investigation of oNT and the analogous o-nitrobenzaldehyde by Gilch and co-workers,154 who used femtosecond transient absorption and stimulated Raman spectroscopy, has finally provided a convincing and complete picture of the early events. The results reported by these authors about oNT154a are summarized in Scheme 30, which bears a striking similarity to that for the photoenolization of o-methylacetophenone (Scheme 4 in section 2.2).

Scheme 30. Reaction Mechanism for the Phototautomerization of oNT in THF154a.

In aqueous solution, equilibration between the (Z)- and (E)-aci-isomers by proton exchange between the oxygen atoms through solvent water is faster than the intramolecular back-reaction (Z)-aci → oNT and the aci-decay obeys a single exponential rate law.153f A detailed investigation of the pH–rate profile provided the acidity constant of the equilibrated aci-tautomers of oNT, pKa = 3.57 ± 0.02, and kinetic isotope effects on the aci-decay kinetics indicated that the dominant rate-determing step for aci-decay switches from carbon protonation by H+ below pH 6 to carbon protonation by water above pH 6. In strongly acidic solutions, acid-catalyzed addition of water to the methylene carbon followed by dehydration of the resulting nitroso hydrate yields o-nitrosobenzyl alcohol.153f

A total quantum yield (Φaci = 0.08) for the formation of aci-nitro tautomers from oNT in tetrahydrofuran (THF) was estimated on the basis of transient absorbance intensities;154a this value is an order of magnitude larger than previous estimates that were obtained with aqueous solutions of oNT by photoinduced H/D exchange153f and by another comparison of transient absorbance intensities.155 The discrepancy was attributed to fast retautomerization of the (Z)-aci-nitro isomer to oNT.154a However, this explanation cannot hold as the (Z)- and (E)-isomers are rapidly equilibrated in aqueous solution.153f An independent value of Φaci for oNT might be obtained by measuring the quantum yield of the irreversible reaction in strongly acidic solutions.153f Fortunately, many derivatives of oNT show much higher quantum yields Φaci (vide infra).

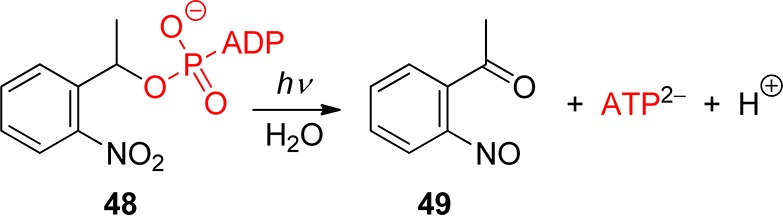

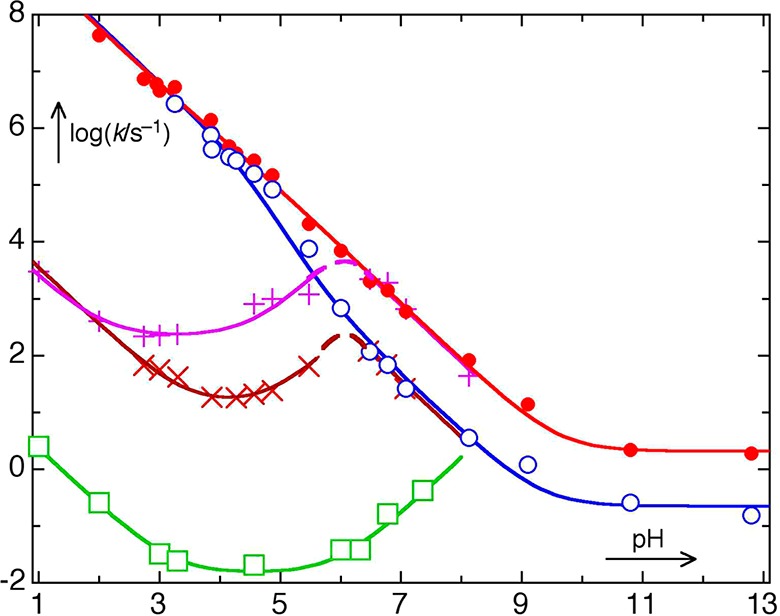

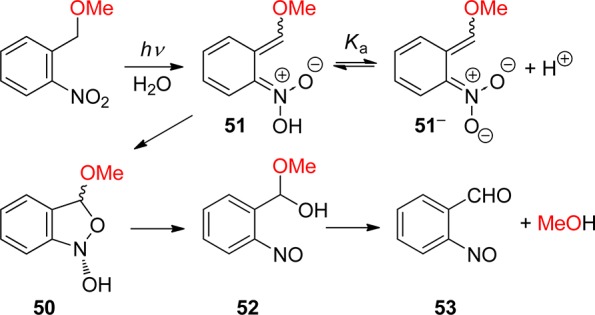

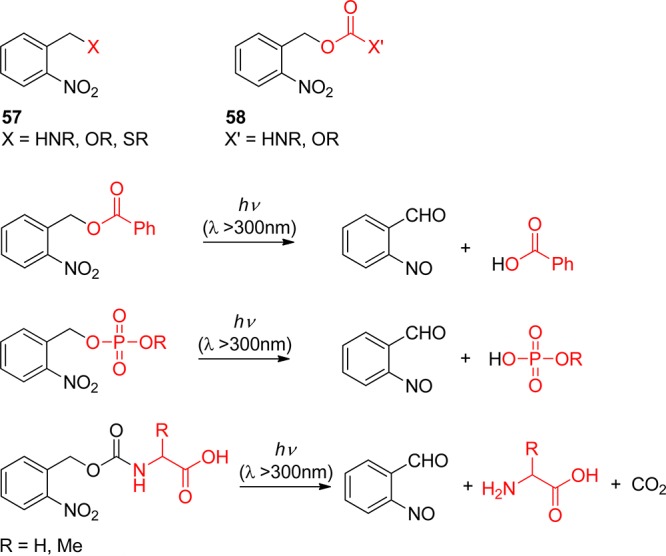

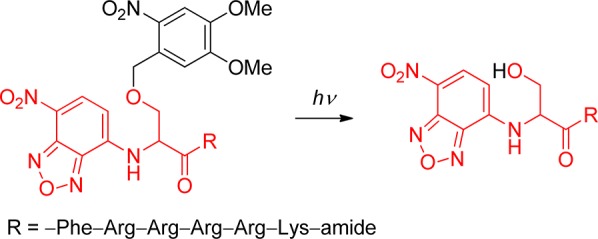

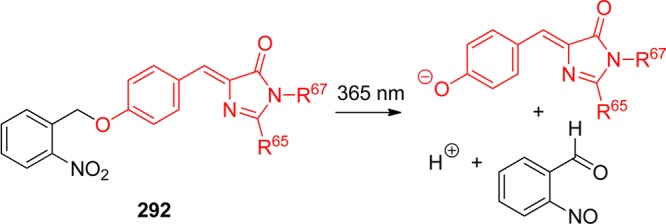

o-Nitrobenzyl (oNB) and 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl (NPE; see section 3.2) derivatives that carry a leaving group at the benzylic position release the protected substrate upon irradiation. The reaction proceeds via aci-nitro intermediates that are readily observed by flash photolysis at λmax ≈ 400 nm. The decay of these aci-transients frequently follows a biexponential rate law (due, presumably, to the formation of both geometrical isomers at the methylene group); the aci-decay rate constants are on the order of 102–104 s–1 and vary strongly with substitution, solvent, and pH in aqueous solution. A detailed mechanistic study of the release of ATP from “caged ATP”,6P3-1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl ester of adenosine triphosphate 48 (Scheme 31), was reported in 1988 by Trentham and co-workers.156

Scheme 31. Photochemistry of P3-1-(2-Nitrophenyl)ethyl Ester of Adenosine Triphosphate156.

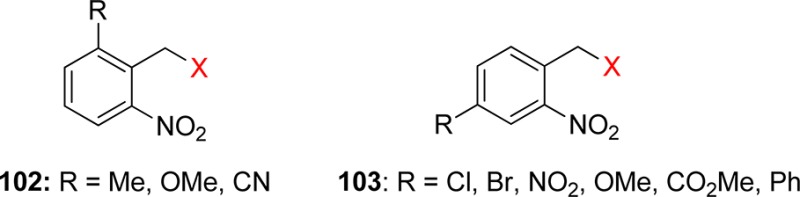

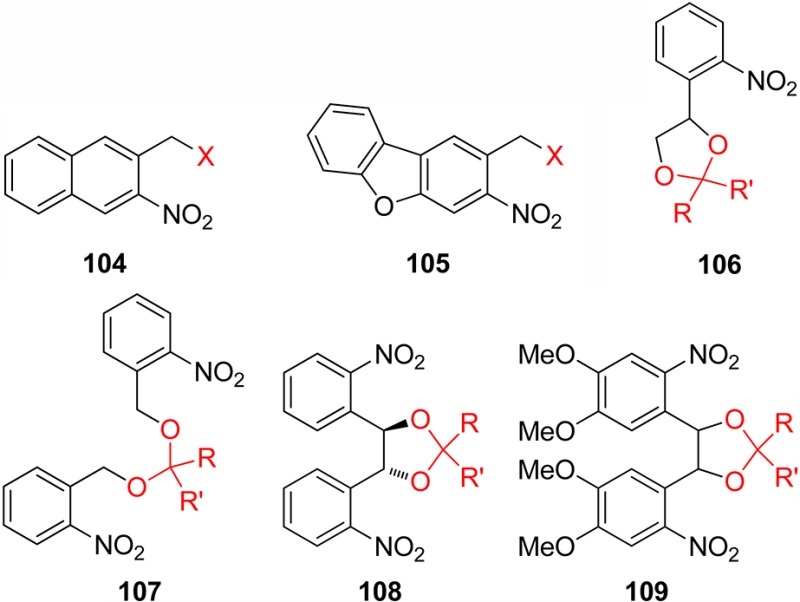

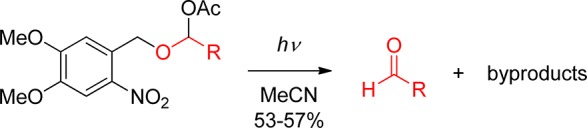

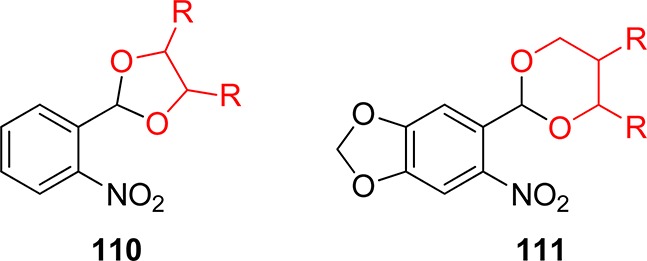

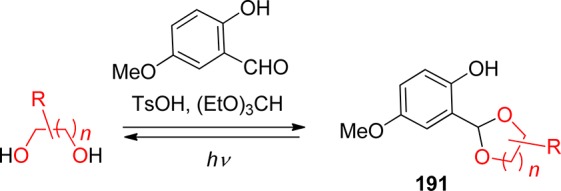

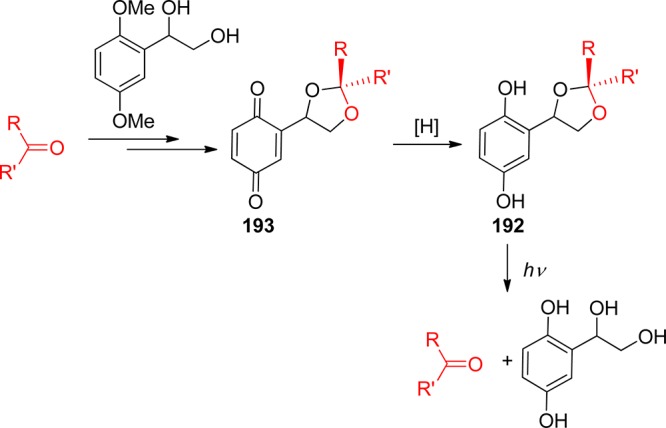

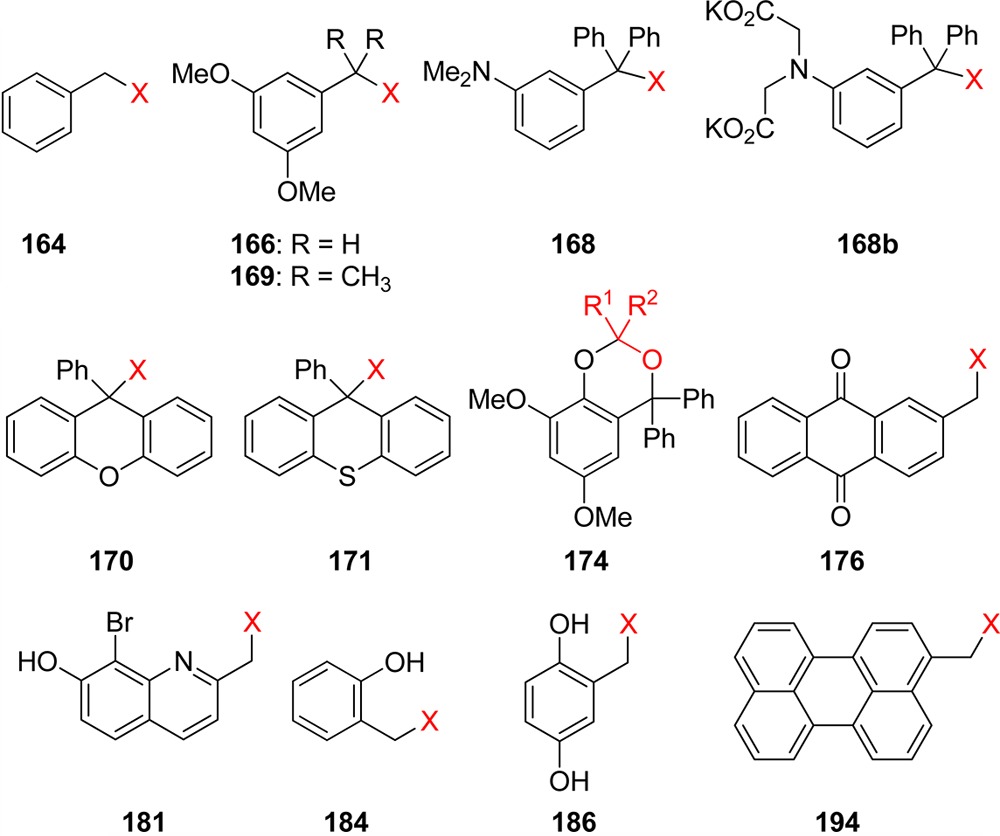

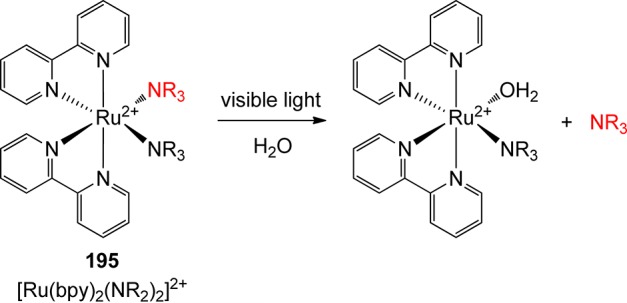

The appearance rates of the three products formed by irradiation of caged ATP, namely, ATP2–(bioassay), 2-nitrosoacetophenone (49, absorption at 740 nm), and H+ (using an indicator dye), were each monitored and were found to coincide with the decay of the aci-nitro intermediate. Later work using time-resolved infrared detection and isotopic labeling further established that the release of ATP occurs in a first-order reaction that is synchronous with the decay of the aci-anion (k = 52 s–1 at pH 7, 10 °C).157 The reaction mechanism proposed by Trentham and co-workers156 was unchallenged for many years, and it was frequently taken for granted that aci-decays were synchronous with substrate release. That assumption is not warranted in general, however, especially with more nucleophilic leaving groups.