Summary

In the past decade, Xenopus tropicalis has emerged as a powerful new amphibian genetic model system, which offers all of the experimental advantages of its larger cousin, Xenopus laevis. Here we investigated the efficiency of transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) for generating targeted mutations in endogenous genes in X. tropicalis. For our analysis we targeted the tyrosinase (oculocutaneous albinism IA) (tyr) gene, which is required for the production of skin pigments, such as melanin. We injected mRNA encoding TALENs targeting the first exon of the tyr gene into two-cell-stage embryos. Surprisingly, we found that over 90% of the founder animals developed either partial or full albinism, suggesting that the TALENs induced bi-allelic mutations in the tyr gene at very high frequency in the F0 animals. Furthermore, mutations tyr gene were efficiently transmitted into the F1 progeny, as evidenced by the generation of albino offspring. These findings have far reaching implications in our quest to develop efficient reverse genetic approaches in this emerging amphibian model.

Key words: Reverse genetics, TAL effector, Nuclease, Targeted mutagenesis

Introduction

Xenopus laevis has been a staple model organism in biomedical research for over half a century (Harland and Grainger, 2011). In the past decade, Xenopus tropicalis has come onto the scene of amphibian model organisms, due to its diploid genome and shorter generation time, making it especially attractive for both genomic and genetic studies (Amaya et al., 1998; Amaya, 2005; Hellsten et al., 2010). However, one serious limitation to this system has been the paucity of efficient methods for generating targeted mutations of endogenous genes. A recent study described the efficacy of using engineered zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) to generate targeted mutations in X. tropicalis (Young et al., 2011). However, there are several disadvantages to the use of ZFNs, including their expense and the need for extensive screening in order to optimize binding specificity for each target sequence of interest (reviewed by Davis and Stokoe, 2010). We therefore decided to assess whether TALENs might be able to provide an alternative approach for generating targeted mutations in X. tropicalis.

Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) are artificial proteins containing TAL effector DNA binding domains fused to the catalytic domain of the endonuclease, FokI (Christian et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2011). Transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) are natural proteins originating from Xanthomonas, a plant pathogen (Boch and Bonas, 2010; Bogdanove et al., 2010). TALEs bind target sequences in the host genome, where they modulate gene expression. The DNA binding domain of TALEs comprises tandem repeats of 34 amino acid sequences, whereby each repeat recognizes one nucleotide in the target DNA binding sequence. Each repeat is highly conserved with the exception of two amino residues, termed the repeat variable diresidues (RVDs), which are responsible for binding specificity to each individual nucleotide. Repeats with different RVD bind to different nucleotides generating a simple one-to-one correspondence of RVD per nucleotide (Boch et al., 2009; Moscou and Bogdanove, 2009). By engineering the sequential repeats in a defined order, one is able to generate TALENs that can bind any sequence of interest (Zhang et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011). Due to the presence of Fok1 endonuclease, TALENs induce double strand breaks in the target site, thereby stimulating non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) or homology directed repair (HDR), which often generates mutations at or near the target site (Christian et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2011). Given the purported high efficiency TALENs for gene editing and targeted mutagenesis in various organisms (Huang et al., 2011; Tesson et al., 2011; Hockemeyer et al., 2011; Bedell et al., 2012), we decided to assess the efficiency of TALENs for generating targeted mutations in Xenopus tropicalis.

Results

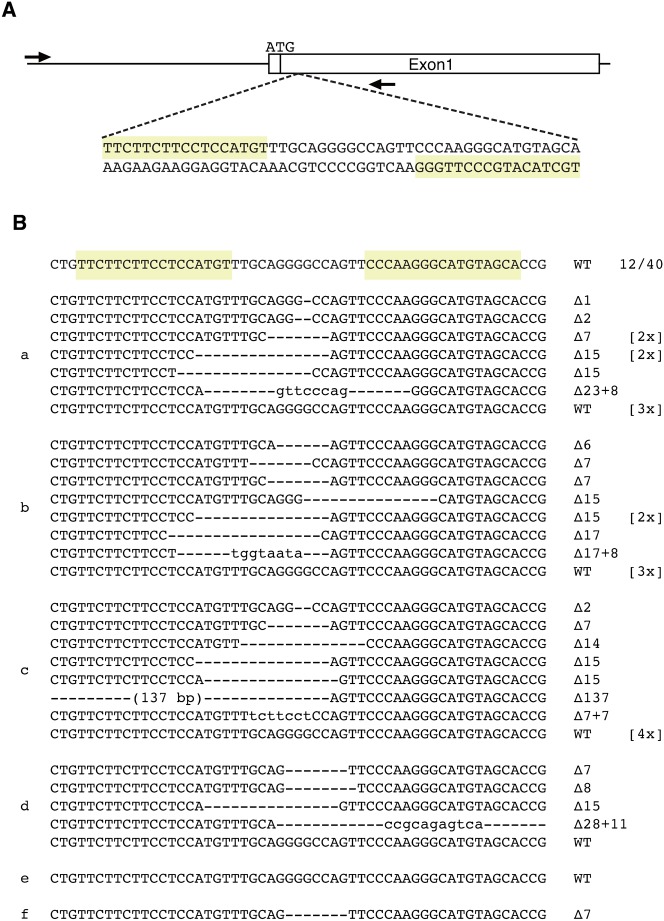

We designed TALENs to target the first exon of the tyrosinase (oculocutaneous albinism IA) gene of Xenopus tropicalis (Fig. 1A). We chose the tyr gene as mutations in this gene would be expected to be viable, but lead to an easily discernible phenotype, namely albinism (Koga et al., 1995; Oetting et al., 2003; Beermann et al., 2004; Damé et al., 2012). Synthetic mRNAs for TALENs were injected into each blastomere at the 2-cell stage. At the mid-neurula stage, genomic DNA was extracted individually from six embryos injected with TALEN RNAs. We amplified by PCR a 932 bp genomic DNA region from each embryo, including the target sequence. Between 1 and 11 PCR clones from each embryo were sequenced to determine what mutations, if any, had been induced by the tyr TALENs. As shown in Fig. 1B, 28/40 (70%) of clones carried deletions of varying sizes from 1 bp to 137 bp around the target sequence.

Fig. 1. Mutations in the tyr gene following TALEN mRNAs injection into embryos.

(A) TALEN target sequences in exon 1, 27 bp downstream from the initiation codon in the tyr gene are boxed in yellow. (B) Mutations induced by TALENs. 400 pg of each TALEN RNA was injected into 2-cell stage embryos and DNA was extracted at stage 18 (mid-neurula) from six individual embryos. The wild type sequence is shown at the top with TALEN binding sites marked in yellow. Sequences from each individual embryo is shown separately, with each having a separate annotation, from “a” to “f”. Deletions are indicated by dashes. The sizes of deletion (▵) and insertion (+) are presented in the right of the each allele. The number of times that each mutant allele was isolated is shown between square brackets.

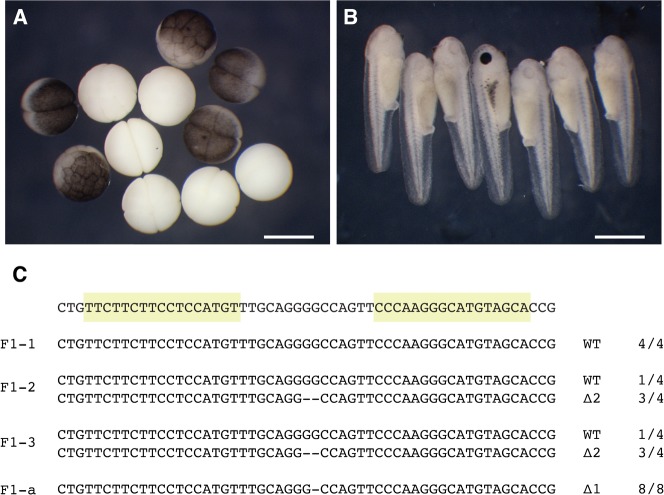

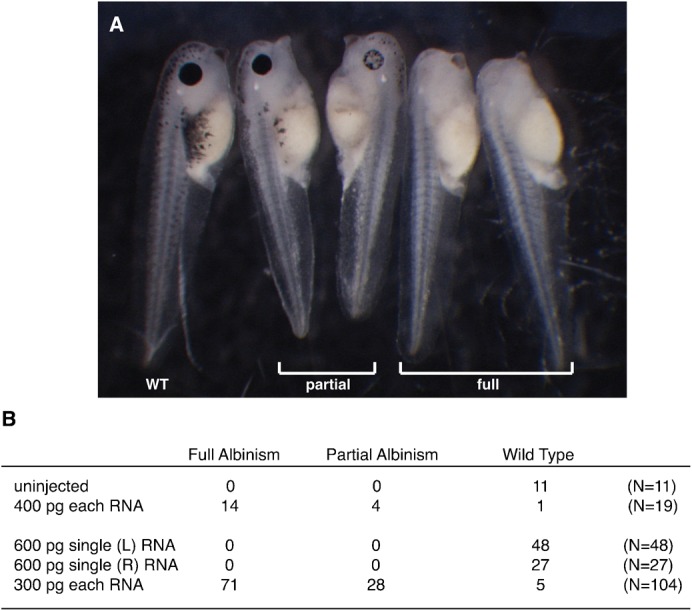

A total of 153 embryos were injected with 300 pg of each TALEN RNA in three independent experiments. 58–90% of the injected embryos survived and were raised for phenotypic analysis. To our surprise, a high percentage of the injected embryos displayed either partial or full albinism as tadpoles (Fig. 2A, Fig. 3A). Indeed the vast majority (71 out of 104, or 68%) of tadpoles showed full albinism (Fig. 2B). Embryos injected with 600 pg of mRNA encoding only the Left TALEN or the Right TALEN survived at similar rates to those injected with mRNA encoding the TALEN pair (82–85%, n = 90). However, all surviving embryos injected with the single TALENs developed normal pigmentation (Fig. 2B, Fig. 3A). Given that the survival rates varied amongst each experiment, regardless of whether the embryos were injected with mRNA encoding the TALEN pairs or individual TALENs, we believe that the variable survival rates were not due to TALEN toxicity, but rather due to variable egg or embryo batch quality. Some tadpoles injected with mRNA encoding both tyr TALENs were raised to adulthood, and three frogs, one male and two females, have reached maturity. Although they showed some mosaicism, most of the skin in all the frogs was albino (Fig. 3B). These results strongly suggest that TALENs can induce widespread bi-allelic mutations in somatic cells of tadpole and adult X. tropicalis.

Fig. 2. Phenotypic analysis of the embryos injected with tyr TALEN RNAs.

(A) Representative embryos injected with tyr TALEN RNAs. We screened the injected embryos and split them into groups showing wild type, partial albinism or full albinism. (B) Number of embryos showing wild type, partial or full albinism after injecting with mRNA encoding the shown TALENs.

Fig. 3. Phenotype in F0 tadpoles and adult frogs, with bi-allelic mutations in the tyr gene, resulting in albinism.

(A) Tadpole injected with 600 pg of RNA encoding Left TALEN (upper) and albino tadpole injected with 300 pg of RNA encoding each of the TALEN pair targeting the tyr gene (lower). Scale bar: 1 mm. (B) Control, wild type (right) and albino frog (left), generated by injecting TALEN mRNAs targeting the tyr gene.

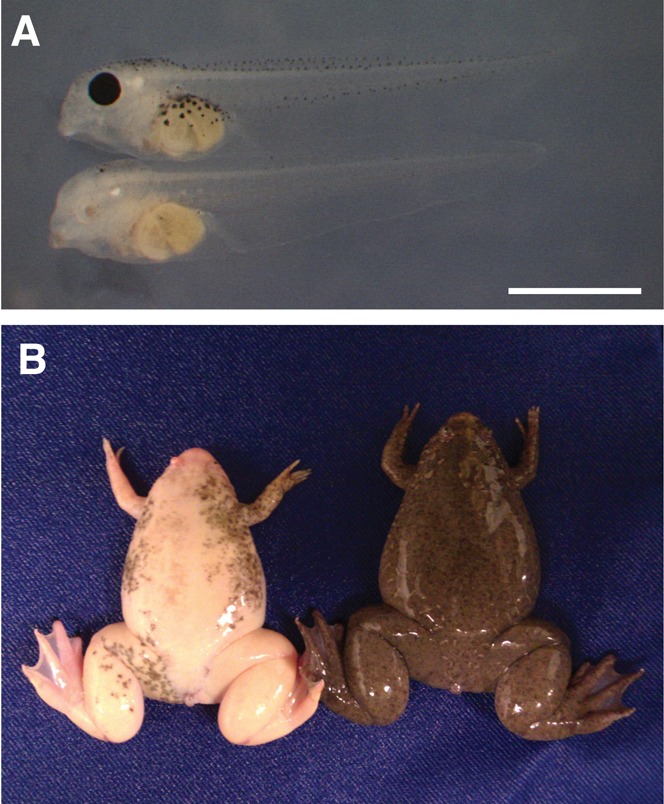

Next we sought to determine whether TALENs could also be used to generate mutations in the tyr gene in the germline. Thus we tested whether albinism in the adult F0 animals could be transmitted to the next generation by mating the three mature frogs. We mated the male frog with both females. One of the matings gave rise to 423 fertilized embryos. Of these, 16 embryos were albino at the cleavage stage, suggesting that a subset of germ cells in the female were homozygous mutant (Fig. 4A). 60% of these became pigmented by the tailbud stage, suggesting that the embryos inherited a wild type tyr allele from the male. On the other hand, 11.4% (18/158) of the pigmented cleavage stage embryos later became albino, suggesting that they had inherited a mutant allele from each parent (Fig. 4B). The other female was also mated with the male used in the previous mating. 150 fertilized embryos were obtained and they were all pigmented at the cleavage stage. The tyr loci from three randomly chosen pigmented embryos at stage 11–12 were amplified by PCR and 4–6 clones from each embryo were sequenced, in order to assess the genotype of both tyr alleles in these embryos. We found that one embryo was a wild type, while the other two were heterozygous, carrying one wild type allele and one mutant allele with two nucleotides deletion at the TALENs target site (Fig. 4C). We also extracted genomic DNA from one albino F1 embryo and analysed its genotype through genomic PCR amplification, followed by cloning and sequencing as before. All 8 clones sequenced from the albino F1 embryo had one nucleotide deletion in the tyr locus, confirming that this embryo was homozygous mutant for the tyr gene (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. Mutations induced by TALENs are heritable through the germline.

(A) F1 cleavage stage embryos produced by mating F0 frogs previously injected with mRNAs encoding TALENs targeting the tyr gene, give rise to a mixture of albino and pigmented embryos. (B) F1 tadpoles produced by mating F0 frogs previously injected with mRNAs encoding TALENs targeting the tyr gene, give rise to a mixture of albino tadpoles, flanking a pigmented sibling tadpoles (centre). (C) The tyr loci were amplified by PCR from three randomly selected F1 embryos (F1-1 to 3), and PCR clones from these embryos were sequenced. One was homozygous wild type (top), the other two were heterozygous mutant. F1-a represents sequence from an albino F1 embryo, which confirmed that the embryo was homozygous mutant. Genotype and frequency of sequence are shown in the right of the each allele. Scale bar: 1 mm.

Discussion

We have shown that TALENs are highly efficient in inducing bi-allelic mutations in a target gene in X. tropicalis embryos. These results have far reaching implications in the advancement of methodologies for performing efficient reverse genetics in Xenopus. Since TALE repeats can be assembled cheaply by using standard cloning methods in the laboratory (Zhang et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011), combined with the low cost of maintaining X. tropicalis, our findings suggest that TALENs offers a relatively cheap and efficient means of generating targeted mutations in genes in this system.

The efficiency rates we have obtained are sufficiently high that one could easily contemplate using TALEN technology as a low cost alternative to antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) for performing loss of function experiments in Xenopus. In recent years, injection of antisense MOs into cleaving embryos has become a mainstay technique in the Xenopus toolkit (Eisen and Smith, 2008). However, there are several potential disadvantages to the use of MOs for loss of function experiments. First, it depends on the purchase of reagents from a single supplier, which can be costly. Second, antisense MOs result in transient knockdowns (Nutt et al., 2001), which mean that assessment of gene function at later stages of development becomes less efficient, and other methods of delivery must be employed (such as electroporation or lipofection) (Falk et al., 2007; Ohnuma et al., 2002). In contrast, TALENs have the potential of generating targeted bi-allelic mutations in endogenous genes at high frequency, thus resulting in permanent, rather than transient, disruption in gene function. Furthermore, given that TALENs are gene based, one can contemplate using this technology for performing tissue specific knockouts of genes or generating knockouts under temporal control. The TALEN constructs can be driven under the control of temporal or spatially restricted promoters, via transgenesis, thus resulting in cell type specific or temporally restricted knockout of endogenous genes in embryos, tadpoles or adult animals. For these reason, we predict that TALENs have the potential of transforming the sort of reverse genetic experiments that become possible in this emerging genetic system.

Materials and Methods

TALEN constructs

Custom TALENs were purchased from Cellectis bioresearch (France). The target sequence for left and right TALENs are in Fig. 1A. TALENs coding region were cloned into the pCS2+ vector (Turner and Weintraub, 1994).

RNA synthesis and microinjections

pCS2+ TALEN vectors were linearized with NotI and transcribed in vitro using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 kit (Ambion). X. tropicalis embryos were obtained by natural mating after hormone injections and dejellied in 2% L-Cysteine, pH 8.0. Each blastomere of two-cell stage embryos was injected with 1 nl of 150 or 200 ng/µl each TALEN RNA. Injected embryos were incubated at 23°C in 0.01× Marc's Modified Ringers.

Genomic PCR for sequencing analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from each embryo and the target site was amplified using following primers: 5′-GAATGGAGCGGATCTATCACGGGCTGCCTCTG-3′ and 5′-GCCAGTGACTATGACATAGTCACGGCTGGTGG-3′ (Sigma–Aldrich, UK). PCR was performed using ExTaq (TAKARA) under the following conditions: 94°C for 5 min followed by 36 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 68°C for 1 min. PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO using TOPO-TA kit (Invitrogen). After transformation, single colonies were cultured and plasmid DNA was prepared using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (QIAGEN) for sequencing. Colonies were also used for direct PCR to amplify the insert using M13 forward and M13 reverse primers under the conditions: 94°C for 5 min followed by 34 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min. 40–100 ng PCR product was incubated with 4 units of ExoI nuclease (New England Biolabs) and 0.5 units of TSAP (Promega) and sequenced using M13 forward primer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adam Johnson and Robert Hallworth for maintenance of the frog facility. This work was supported by a Programme Grant from the Wellcome Trust (WT082450MA).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Amaya E. (2005). Xenomics. Genome Res. 15, 1683–1691 10.1101/gr.3801805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaya E., Offield M. F., Grainger R. M. (1998). Frog genetics: Xenopus tropicalis jumps into the future. Trends Genet. 14, 253–255 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01506-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedell V. M., Wang Y., Campbell J. M., Poshusta T. L., Starker C. G., Krug Ii R. G., Tan W., Penheiter S. G., Ma A. C., Leung A. Y.et al. (2012). In vivo genome editing using a high-efficiency TALEN system. Nature [Epub ahead of print] 10.1038/nature11537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beermann F., Orlow S. J., Lamoreux M. L. (2004). The Tyr (albino) locus of the laboratory mouse. Mamm. Genome 15, 749–758 10.1007/s00335-004-4002-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch J., Bonas U. (2010). Xanthomonas AvrBs3 family-type III effectors: discovery and function. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 419–436 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch J., Scholze H., Schornack S., Landgraf A., Hahn S., Kay S., Lahaye T., Nickstadt A., Bonas U. (2009). Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science 326, 1509–1512 10.1126/science.1178811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove A. J., Schornack S., Lahaye T. (2010). TAL effectors: finding plant genes for disease and defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 394–401 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian M., Cermak T., Doyle E. L., Schmidt C., Zhang F., Hummel A., Bogdanove A. J., Voytas D. F. (2010). Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics 186, 757–761 10.1534/genetics.110.120717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damé M. C., Xavier G. M., Oliveira–Filho J. P., Borges A. S., Oliveira H. N., Riet–Correa F., Schild A. L. (2012). A nonsense mutation in the tyrosinase gene causes albinism in water buffalo. BMC Genet. 13, 62 10.1186/1471-2156-13-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D., Stokoe D. (2010). Zinc finger nucleases as tools to understand and treat human diseases. BMC Med. 8, 42 10.1186/1741-7015-8-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen J. S., Smith J. C. (2008). Controlling morpholino experiments: don't stop making antisense. Development 135, 1735–1743 10.1242/dev.001115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk J., Drinjakovic J., Leung K. M., Dwivedy A., Regan A. G., Piper M., Holt C. E. (2007). Electroporation of cDNA/Morpholinos to targeted areas of embryonic CNS in Xenopus. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 107 10.1186/1471-213X-7-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland R. M., Grainger R. M. (2011). Xenopus research: metamorphosed by genetics and genomics. Trends Genet. 27, 507–515 10.1016/j.tig.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellsten U., Harland R. M., Gilchrist M. J., Hendrix D., Jurka J., Kapitonov V., Ovcharenko I., Putnam N. H., Shu S., Taher L.et al. (2010). The genome of the Western clawed frog Xenopus tropicalis. Science 328, 633–636 10.1126/science.1183670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockemeyer D., Wang H., Kiani S., Lai C. S., Gao Q., Cassady J. P., Cost G. J., Zhang L., Santiago Y., Miller J. C.et al. (2011). Genetic engineering of human pluripotent cells using TALE nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 731–734 10.1038/nbt.1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P., Xiao A., Zhou M., Zhu Z., Lin S., Zhang B. (2011). Heritable gene targeting in zebrafish using customized TALENs. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 699–700 10.1038/nbt.1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga A., Inagaki H., Bessho Y., Hori H. (1995). Insertion of a novel transposable element in the tyrosinase gene is responsible for an albino mutation in the medaka fish, Oryzias latipes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 249, 400–405 10.1007/BF00287101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. C., Tan S., Qiao G., Barlow K. A., Wang J., Xia D. F., Meng X., Paschon D. E., Leung E., Hinkley S. J.et al. (2011). A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 143–148 10.1038/nbt.1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscou M. J., Bogdanove A. J. (2009). A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science 326, 1501 10.1126/science.1178817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt S. L., Bronchain O. J., Hartley K. O., Amaya E. (2001). Comparison of morpholino based translational inhibition during the development of Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis. Genesis 30, 110–113 10.1002/gene.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting W. S., Fryer J. P., Shriram S., King R. A. (2003). Oculocutaneous albinism type 1: the last 100 years. Pigment Cell Res. 16, 307–311 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma S., Mann F., Boy S., Perron M., Harris W. A. (2002). Lipofection strategy for the study of Xenopus retinal development. Methods 28, 411–419 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00260-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesson L., Usal C., Ménoret S., Leung E., Niles B. J., Remy S., Santiago Y., Vincent A. I., Meng X., Zhang L.et al. (2011). Knockout rats generated by embryo microinjection of TALENs. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 695–696 10.1038/nbt.1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D. L., Weintraub H. (1994). Expression of achaete-scute homolog 3 in Xenopus embryos converts ectodermal cells to a neural fate. Genes Dev. 8, 1434–1447 10.1101/gad.8.12.1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. J., Cherone J. M., Doyon Y., Ankoudinova I., Faraji F. M., Lee A. H., Ngo C., Guschin D. Y., Paschon D. E., Miller J. C.et al. (2011). Efficient targeted gene disruption in the soma and germ line of the frog Xenopus tropicalis using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7052–7057 10.1073/pnas.1102030108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Cong L., Lodato S., Kosuri S., Church G. M., Arlotta P. (2011). Efficient construction of sequence-specific TAL effectors for modulating mammalian transcription. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 149–153 10.1038/nbt.1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]