Abstract

Shikonin has anticancer activity, but it has not yet been applied into clinical use. In the present study, shikonin was prepared using liposomes. We aimed to examine several aspects of sh-L (shikonin-containing liposomes): preparation, angiogenic suppression and cellular uptake through self-fluorescence. Sh-L were prepared using soybean phospholipid and cholesterol to form the membrane and shikonin was encapsulated into the phospholipid membrane. Three liposomes were prepared with shikonin. They had red fluorescence and were analysed using a flow cytometer. Angiogenic suppression of sh-L was determined using MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide], Transwell tests, chick CAM (chorioallantoic membrane) and Matrigel™ plug assay. MTT assay showed the median IC50 (inhibitory concentrations) as follows: shikonin, sh-L1 and sh-L2 were 4.99±0.23, 5.81±0.57 and 7.17±0.69 μM, respectively. The inhibition rates of migration were 53.58±7.05, 46.56±4.36 and 41.19±3.59% for 3.15 μM shikonin, sh-L1 and sh-L2, respectively. The results of CAM and Matrigel plug assay demonstrated that shikonin and sh-L can decrease neovascularization. Effect of shikonin was more obvious than sh-L at the same concentration. The results showed that sh-L decreased the toxicity, the rate of inhibition of migration and angiogenic suppression. The cellular uptake of the sh-L could be pictured because of the self-fluorescence. The self-fluorescence will be useful for conducting further research. Sh-L might be an excellent preparation for future clinical application to cancer patients.

Keywords: angiogenic suppression, chick chorioallantoic membrane, Matrigel plug assay, self-fluorescent shikonin-containing liposome, Transwell test

Abbreviations: CAM, chorioallantoic membrane; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DIO, 3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide; PFA, paraformaldehyde; sh-L, shikonin-containing liposomes; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

INTRODUCTION

Boraginaceaeous plants, such as Onosma paniculatum Bur. et Franch. and Lithospermum erythrorhizon Sieb. et Zucc., have been of interest to researchers because of one of the chemical constituents – shikonin. Shikonin has various pharmacological activities and has been used in China to treat macular eruptions, measles, sore throat, carbuncles and burns, for several years [1]. Previous studies have shown that shikonin has multiple pharmacological properties, such as anti-proliferative activities, anti-angiogenic [2,3], anti-inflammatory [4,5], anti-virus [6], antioxidant [7], anti-adipogenesis [8], immunomodulatory effects [9], wound healing [10] and others [11,12].

Shikonin suppresses angiogenesis and inhibits various cancer cells, including HeLa cells [13], colon cancer cells [14], human breast cancer cells [15] and human lung cancer DMS114 cells [16] and so on.

Angiogenesis is the formation of new blood vessels by ‘sprouting’ and ‘splitting’ from established vasculature. It is a fundamental process that is required for new organ development and differentiation during embryogenesis, growth and wound healing [17]. Angiogenesis is also vital to the growth and metastasis of solid tumours [18].

Angiogenesis is a complex, tightly regulated process. It occurs via the activation and inhibition of a number of diverse, yet interrelated signalling pathways involving many different anti- and pro-angiogenic factors, which ultimately result in the activation or inhibition of endothelial cell growth [19]. Some of these factors are highly specific to endothelial cells, such as VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), whereas others such as metalloproteinases are much less specific, acting on a broader range of cells [17].

Angiogenesis is closely connected to cancer. The proliferation of cancer cells requires abundant oxygen and nutritive materials from blood vessels, which are recruited by angiogenesis. Therefore suppression of angiogenesis can effectively inhibit cancer growth.

However, shikonin has not been applied yet to cure cancer in clinical settings. In the present study, shikonin was prepared using liposomes. Recently, Papageorgiou's and Assimopoulou's group first prepared shikonin-loaded liposomes, in order to decrease shikonin toxicity and improve its therapeutic index [20]. Additionally, chimaeric shikonin-loaded drug-delivery systems have been presented by the same group [21].

We show that shikonin-loaded liposomes can decrease the toxicity of shikonin effectively using MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] and Transwell tests in vitro; and CAM (chorioallantoic membrane) and Matrigel plug assay in vivo. In addition, we demonstrated that self-fluorescent liposomes are a useful method to track shikonin ad-ministration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibody

Shikonin (purity 98%, HPLC) was bought from Chengdou Jianteng Biotechnological. Soya bean phospholipid and cholesterol was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Limited Corporation. Bacteria-derived recombinant human VEGF165 was purchased from Sigma. Heparin was bought from Nanjing Xinbai Pharmaceuticals. MTT was bought from the Sunshine. Growth factor-reduced Matrigel was purchased from BD Biosciences. Antibody against CD31 was bought from Epitomics. FITC-labelled secondary antibody was bought from the Abcam. All other chemicals and solvents were analytical reagent grade.

Preparation of sh-L (shikonin-containing liposomes)

Sh-L were prepared according to the procedure described below using 1.5 mg of shikonin, 100 mg of soybean phospholipid and 20 mg of cholesterol, which were dissolved in 10 ml of dehydrated alcohol. The mixture was aspirated using a syringe and injected into 10 ml of PBS (60±5°C). Blank control samples were prepared by adopting the same method without shikonin. After vaporizing the alcohol, the solution was filtrated using the membrane (pore size of 0.22 μm). We prepared different entrapment rates of shikonin-loaded liposomes: sh-L1, sh-L2 and sh-L3 for further research.

In order to prepare different entrapment rates of sh-L1, sh-L2 and sh-L3, 50, 80 and 100% of 1.5 mg of shikonin was put into the system to prepare the liposomes first. Then the residual quantities were added (Table 1). Finally, the volume of them was all 10 ml. So the concentration was all about 1.5 mg/ml (1.41±0.14, 1.42±0.11, 1.46±0.12 mg/ml). However, the entrapment rate of them was different.

Table 1. Amounts of each constituent of sh-L1, sh-L2 and sh-L3.

Shikonin A was the amounts added first. Shikonin B was the residual quantities added later.

| Name | Shikonin A (mg) | Shikonin B (mg) | Total shikonin (mg) | Soya bean phospholipid (mg) | Cholesterol (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sh-L1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.5 | 100 | 20 |

| sh-L2 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 100 | 20 |

| sh-L3 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 100 | 20 |

Particle size measurement and zeta-potential

Each liposomal formulation was diluted with PBS and put into sample cells of Zeta potentiometer (BI-90 Plus, Brookhaven Instrument), to measure the particle size and zeta-potential, analysed using the Zetapuls particle sizing software. All these measurements were performed immediately after liposome preparation.

Determination of entrapment efficiency

Entrapment efficiency of shikonin was estimated by UV/vis spectrophotometry (UV/Vis 2500, Shimadzu) at the characteristic wavelength of shikonin (516 nm) as described by Kontogiannopoulos et al. [20]. Then 1 ml of each liposomal suspension in PBS was suspended in 10 ml chloroform, followed by vigorously vortex-mixing for 10 min, to destroy the liposome structure, releasing the drug into the organic phase. Absorbance of the organic phase was measured and we calculated the total amount of shikonin (Qtotal). Another 1 ml of each liposomal suspension in PBS was dialysed adequately. The amount of shikonin which was not incorporated into liposomes was calculated (Qout). Then entrapment efficiency was calculated according to the following equation:

Morphology and fluorescence of sh-L

The morphology and fluorescence of the sh-L were observed using a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000-IX81). The fluorescence intensity of three batches of sh-L was analysed using an FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). In total, 10000 liposomes were analysed in each group.

Cellular uptake assay (in vitro)

The cellular uptake assay was performed as follows: HUVECs (human umbilical vein endothelial cells) were plated on to coverslips and incubated with DIO (3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate) and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) solutions to stain the membrane and nuclei of HUVECs, respectively. HUVECs were allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37°C in the 5% CO2 incubator. 200 μl of different concentrations of sh-L (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 16 μM) were added to each test well. After incubation for 5 h, the cells were fixed for 30 min using 4% PFA (paraformaldehyde) and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. The slides were examined using the confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000-IX81) at ×200 magnification.

MTT assay (in vitro)

The MTT assay was performed according to the following scheme: HUVECs were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells/well. They were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. The cytotoxicity of sh-L was evaluated after incubating the cells for 24 h. Next, 20 μl of MTT was added and incubated for 4 h. The medium was removed, and 200 μl of DMSO was added. The absorbance value was measured using the wavelength of 570 nm and the reference wavelength of 450 nm. The test was repeated four times.

Cell migration (Transwell) assay (in vitro)

The cell migration assay was performed in Transwell inserts with a pore size of 8.0 μm (Corning, 3422) in a 24-well plate. Briefly, 600 μl of sh-L (3.15 μM) or control liposomes was added to the lower compartment containing 10% fetal bovine serum in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium). Next, 200 μl of the HUVEC suspension (5×105 cells/ml) with sh-L or control liposomes was added to the upper compartment of the chamber. Migration was allowed to proceed at 37°C for 8 h in a 5% CO2 incubator. After the incubation period, the filter was removed, and cells on the upper side of the filter which had not migrated were scraped away with a cotton applicator. HUVECs on the lower side of the filter were fixed for 30 min using 4% PFA, stained with 0.1% Crystal Violet for 20 min, and washed twice with PBS. The Crystal Violet was dissolved using 33% acetic acid. The absorbance value was measured at the wavelength of 570 nm.

Chick CAM assay (in vivo)

CAM assay was performed as described elsewhere [22]. All procedures were carried out in a laminar flow hood under sterile conditions. Briefly, fertilized 6-day eggs were incubated at 90% humidity and kept in 37°C. A window was made on the top of each egg after 2 days’ incubation. Test samples (5.5 μM) and appropriate buffer controls were spotted on to sterilized Whatman filter paper disks and applied to the surfaces of the growing CAMs above the dense subectodermal plexus. After 48 h of incubation, the CAMs were observed and photographed.

Matrigel plug assay (in vivo)

The Matrigel plug assay was employed as previously described [23] with some modifications. Briefly, Matrigel containing 100 ng of VEGF and 20 IU of heparin with or without indicated amounts of shikonin or sh-L was subcutaneously injected into the dorsal area of ICR mice (n=6 each group). After 8 days, intact Matrigel plugs were carefully exposed, frozen and embedded with OCT (optimal cutting temperature) compound and sliced. To identify infiltrating endothelial cells to form the blood vessels, immunofluorescence analysis was performed with anti-CD31 monoclonal primary antibody and FITC-labelled secondary antibody.

All experimental animals used in the present study were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center, Yangzhou University and maintained in a laminar airflow cabinet under specific-pathogen-free conditions and a 12 h light/dark cycle. Mice were maintained according to the NIH standards established in the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and the study protocol was approved by local institution review boards and animal study was carried out in accordance with the ethical guidelines for animal use and care established by Nanjing University.

RESULTS

Characterization of sh-L

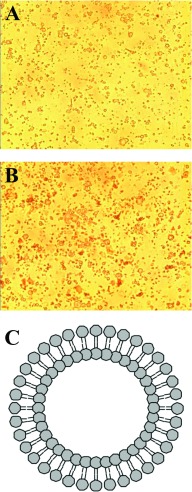

Sh-L have a double phospholipid membrane. The bigger of them were visible through the confocal microscope (Figure 1). Particle size, zeta-potential and entrapment efficiency of sh-L1, sh-L2 and sh-L3 were determined. Results are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1. Morphology of sh-L.

The morphology of the control (A) and sh-L (B) under the confocal microscope (×400) and schematic diagram of the liposomes (C).

Table 2. Particle size, zeta-potential and entrapment efficiency of sh-L1, sh-L2 and sh-L3.

| Name | Particle size (nm) | Zeta-potential (mV) | Entrapment efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sh-L1 | 124.7±11.1 | −34.18±2.23 | 50.5±4.36 |

| sh-L2 | 145.4±10.6 | −38.72±2.43 | 80.37±3.89 |

| sh-L3 | 208.1±13.2 | −36.31±5.15 | 97.62±5.66 |

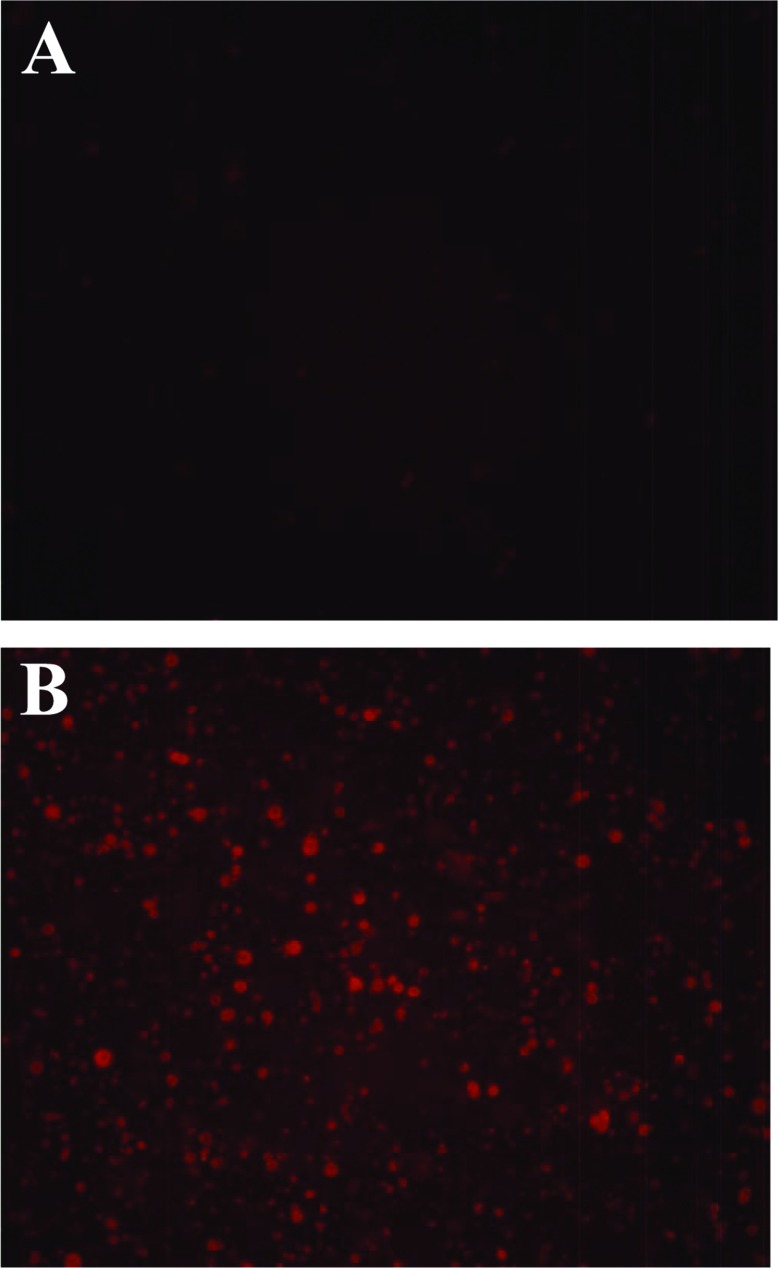

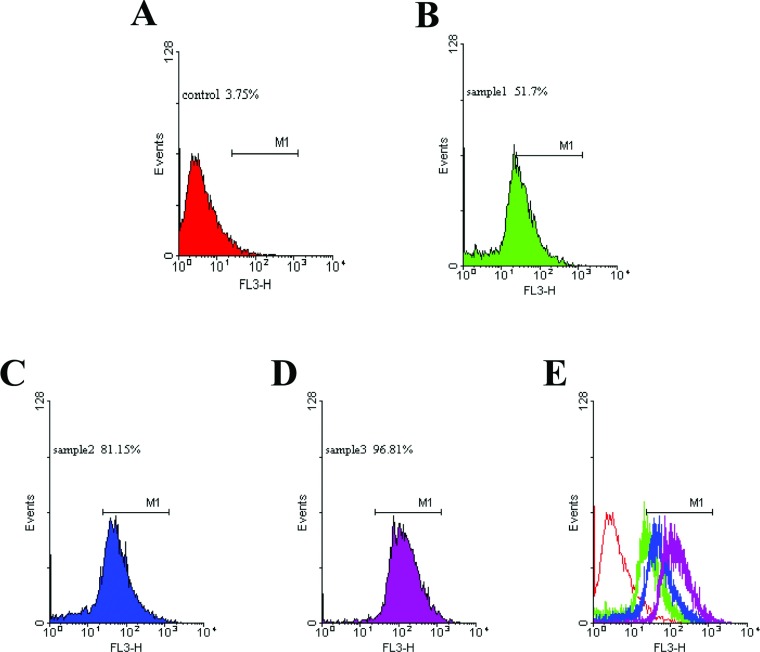

Red fluorescence of sh-L

Red fluorescence was observed (Figure 2) in the liposomes. The intensity of fluorescence was analysed using the flow cytometer, and the values for the control and samples 1–3 (sh-L1, sh-L2 and sh-L3) were 3.75, 51.7, 81.15 and 96.81%, respectively (Figure 3). The results were closely related to the entrapment efficiency above.

Figure 2. Fluorescence of sh-L.

The fluorescence of the blank control (A) and sh-L (B) using a fluorescence microscope (×400).

Figure 3. Fluorescence intensity of sh-L analysed using the flow cytometer.

Flow cytometry results are shown. (A) is the control; (B–D) represent samples 1–3; (E) is the overlap of A, B, C and D.

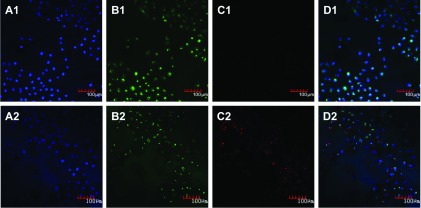

Localization on the membranes of cells (in vitro)

In the cellular uptake experiment, red fluorescence was observed on part of the membranes of HUVECs (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Cellular uptake assay of sh-L.

The blank control (A1–D1) and sh-L (A2–D2) incubated with HUVECs for 5 h were examined using a confocal microscope (×200). (A) Channel of the laser at a wavelength of 405 nm. Blue was the nuclei stained by DAPI; (B) channel of the laser at a wavelength of 488 nm. Green was the membrane stained by DIO; (C) channel of the laser at a wavelength of 543 nm. Red was sh-L fused with the membrane; (D) merged image of (A)–(C).

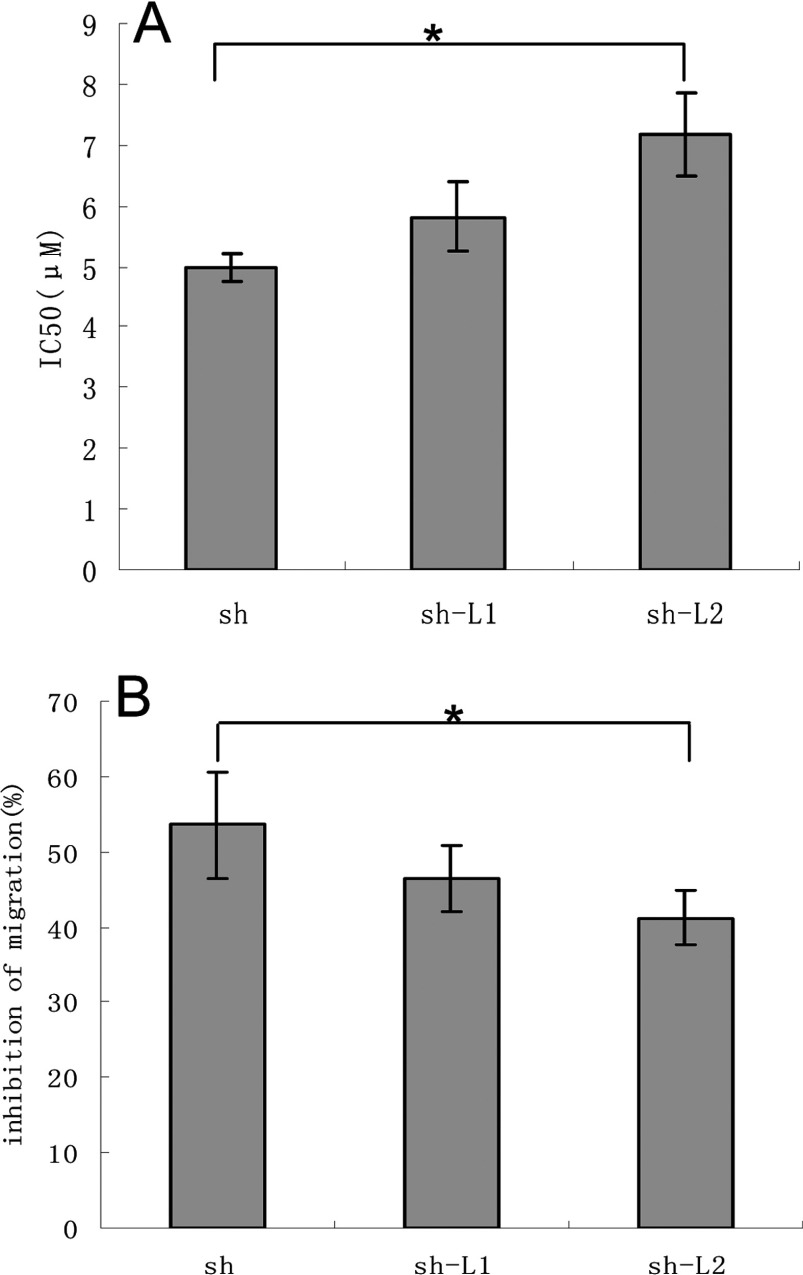

Inhibition of the growth and migration of endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro

The MTT assay showed the median inhibitory concentrations (IC50) as follows: shikonin, sh-L1 and sh-L2 were 4.99±0.23, 5.81±0.57 and 7.17±0.69 μM respectively (Figure 5A). The inhibition rates of migration were 53.58±7.05, 46.56±4.36 and 41.19±3.59% for 3.15 μM shikonin, sh-L1 and sh-L2, respectively (Figure 5B). Differences in the treatments were expressed as means and compared statistically using the LSD (least significant differences) at the 5% level using the one-way ANOVA test with SPSS 13.0 software.

Figure 5. MTT and Transwell assays of shikonin and sh-L.

The statistical analysis of the results of the MTT assay (A) and the Transwell assay (B) (*P<0.05).

The statistical analysis showed that the optimum, sh-L2, which contains high entrapment efficiency (80.37±3.89%) as indicated before significantly decreased the toxicity and the rate of migration inhibition of shikonin (*P<0.05) compared with sh-L1 (low entrapment efficiency). Hence, it was correlated with the entrapment efficiency.

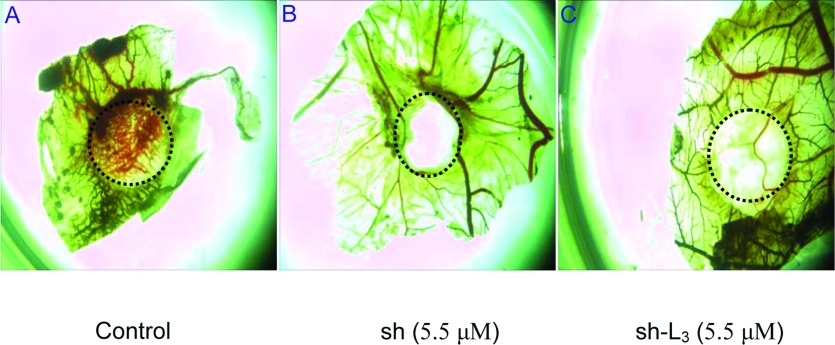

Reduced angiogenesis in CAM assay in vivo

CAM assays were used to examine the effects of shikonin and sh-L on angiogenesis in vivo as they provide a unique model to investigate the process of new blood vessel formation and effects of anti-angiogenic agents.

Compared with the control group, neovascularization of CAM treated with shikonin and sh-L was dramatically decreased. Effect of sh-L on neovascularization was less obvious than shikonin at the same concentration (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effects of shikonin and sh-L on angiogenesis of the chick CAM.

Results of chick CAM assays (A–C).

Not all of the shikonin was released from the liposomes when we performed the assay. So the drug's actual concentration of sh-L groups was lower than that of shikonin groups.

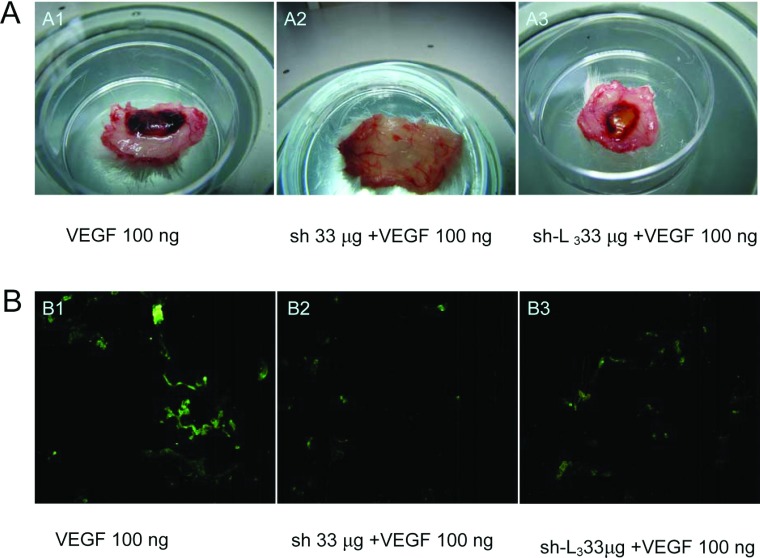

Inhibited VEGF-induced angiogenesis in vivo

We used the mouse Matrigel plug assay to validate shikonin and sh-L-mediated inhibitory actions on angiogenesis in a whole animal model. When embedded subcutaneously into mice, Matrigel plugs containing VEGF alone developed a dark red appearance (Figures 7A-A1, VEGF), indicating that new vasculatures had formed inside the Matrigel through VEGF-triggered angiogenesis. In contrast, the addition of shikonin and sh-L (33 μg/plug) to the Matrigel plugs dramatically inhibited the generation of infiltrating vasculature, leading to the formation of much paler Matrigel plugs in colour (Figure 7A-A2 or A3, VEGF+shikonin or sh-L), suggesting that shikonin and sh-L blocked the formation of new vasculatures in the Matrigel plugs. The effect of sh-L was less obvious than shikonin at the same concentration. This was because the shikonin was released from the liposomes slowly.

Figure 7. Shikonin and sh-L inhibit VEGF-induced angiogenesis.

Representative Matrigel plugs in mice were photographed (A) and inhibition of new blood vasculature formation immunostained with specific anti-CD31 antibody for blood vessels (B). (A1 and B1 were groups of VEGF 100 ng; A2 and B2 were groups of sh 33 μg +VEGF 100 ng; A3 and B3 were groups of sh-L3 33 μg +VEGF 100 ng).

We next performed immunofluorescent analysis with anti-CD31 monoclonal antibody to identify the new vasculature content in the plugs. We found that the groups of CD31-positive endothelial cells in plugs with VEGF alone had brighter fluorescence than those of VEGF+shikonin and VEGF+sh-L (Figure 7B), suggesting that shikonin and sh-L potently suppressed angiogenesis in vivo. Effect of sh-L was less obvious than shikonin at the same concentration too. This was due to the slow release of shikonin from the liposomes. In other words, shikonin was not released from liposomes completely.

DISCUSSION

The double phospholipid membrane of sh-L was similar to that of cells. We hypothesized they might display a good bioaffinity and readily fused with the membrane of target cells. The encapsulated drug was released into the cancer cells and caused specific effects on the cancers, such as inhibiting proliferation and promoting apoptosis. In order to keep the liposomes stable, sh-L were also prepared by the thin-film hydration method, then frozen overnight and lyophilized [21].

The fluorescence intensity of the sh-L corresponded to the entrapment efficiency. Therefore the fluorescence might be a direct and effective way to determine the entrapment efficiency using a flow cytometer.

Red fluorescence of sh-L appeared on part of the membranes of HUVECs first. After some time, it was apparent that cell membrane marker (green) and shikonin fluorescence (red) were overlapping. Therefore sh-L might localize on the cell membrane. Shikonin was then released from the liposomes into the cells and caused the cells to die. These liposomes may play an important role at the cell membrane by interacting with membrane receptors or ion channels or others.

The fluorescence of sh-L has broad applications, including the investigation of the entrapment efficiency, the localization of the cells, cellular uptake or internalization, the mechanisms of endocytosis and the metabolism of the drug in vivo.

Fluorescent substances, such as FITC, DIO and DAPI, have been used as visual markers for drugs. However, fluorescent markers may adversely affect the characteristics of drugs. Therefore self-fluorescent drugs are desirable for studies.

Vascular endothelial cells proliferate much more rapidly during angiogenesis than under normal conditions. They are the major component making up blood vessels. Vascular endothelial cells can migrate to tumours to promote the formation of capillaries during tumour growth. Therefore the inhibition of vascular endothelial cells might suppress tumours. In this study, MTT and cell migration assays were conducted in vitro. The results indicated that sh-L decreased the toxicity and the rate of migration inhibition of shikonin. The rate was correlated with the entrapment efficiency. The results might be attributed to shikonin slow release from the liposomes. At the same time it was also reported that liposomes could be used as a sustained and controlled delivery system [24].

VEGF plays a vital role in angiogenesis. It regulates vascular permeability and mediates vasculogenesis, angiogenic remodelling and angiogenic sprouting [25]. Thus we used VEGF to construct a Matrigel plug model to test the antiangiogenic activities of shikonin and sh-L in vivo. We found that shikonin and sh-L inhibited VEGF-induced angiogenesis.

CD31 is a specific endothelial marker, which represents angiogenesis. It was convenient to track the CD31 expression via the immunofluorescence staining or immunocytochemical staining.

To improve the targeting on specific tumours, methods for modifying the surface of liposomes with anti-VEGF antibody [26] and anti-EGFR antibodies [27], as well as folate [28], should be adopted in future experiments.

Furthermore, sh-L might bypass MDR (multiple drug resistance) and decrease the inflammatory response.

In summary, sh-L emitted red fluorescence and has extensive applications in pharmacology and pharmaceuticals. Liposomes significantly decreased the toxicity of shikonin in vitro and in vivo. Thus sh-L might be an excellent preparation for future clinical applications in the treatment of cancers.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Hongmei Xia did the most of the experimentation and wrote the paper. Chengyi Tang and Heng Gui participated in the experimental work. Xiaoming Wang gave comments on the paper. Jinliang Qi, Xiuqiang Wang and Yonghua Yang devised the hypothesis and experimental plan.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [grant numbers 30701041, 31071082, 31171161 and 31170275], the Project of New Century Excellent Talents in University [grant number NCET-05-0448], and the Natural Science Foundations of the Jiangsu Bureau of Science and Technology [grant numbers BK2010053 and BK2011414].

References

- 1.Chen X., Yang L., Oppenheim J. J., Howard O. M. Z. Cellular pharmacology studies of shikonin derivatives. Phytother. Res. 2002;16:199–209. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komi Y., Suzuki Y., Shimamura M., Kajimoto S., Nakajo S., Masuda M., Shibuya M., Itabe H., Shimokado K., Oettgen P., et al. Mechanism of inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by β-hydroxyisovalerylshikonin. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:269–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan W., Lu J., Huang M., Li Y., Chen M., Wu G., Gong J., Zhong Z., Xu Z., Dang Y., et al. Anti-cancer natural products isolated from Chinese medicinal herbs. Chin. Med. 2011;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu S. C., Yang N. S. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α through selective blockade of pre-mRNA splicing by shikonin. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:1640–1645. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.032821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu L., Qin A., Huang H., Zhou P., Zhang C., Liu N., Li S., Wen G., Zhang C., Dong W., et al. Shikonin extracted from medicinal Chinese herbs exerts anti-inflammatory effect via proteasome inhibition. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;658:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F. Method of Treatment of Virus Infections Using Shikonin Compounds. Beijing JBC Chinese Traditional Medicine Science and Technology Develop Co. Ltd.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assimopoulou A. N., Boskou D., Papageorgiou V. P. Antioxidant activities of alkannin, shikonin and alkanna tinctoria root extracts in oil substrates. Food Chem. 2004;87:433–438. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H., Bae S., Kim K., Kim W., Chung S.-I., Yang Y., Yoon Y. Shikonin inhibits adipogenesis by modulation of the WNT/ β-catenin pathway. Life Sci. 2011;88:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pietrosiuk A., Skopinska-Rozewska E., Furmanowa M., Wiedenfeld H., Sommer E., Sokolnicka I., Rogala E., Radomska-Lesniewska D., Bany J., Malinowski M. Immunomodulatory effect of shikonin derivatives isolated from Lithospermum canescens on cellular and humoral immunity in Balb/c mice. Pharmazie. 2004;59:640–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papageorgiou V. P., Assimopoulou A. N., Ballis A. C. Alkannins and shikonins: a new class of wound healing agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:3248–3267. doi: 10.2174/092986708786848532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papageorgiou V. P., Assimopoulou A. N., Couladouros E. A, Hepworth D., Nicolaou K. C. Chemistry and biology of alkannins, shikonins and related naphthazarin natural products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1999;38:270–300. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<270::AID-ANIE270>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papageorgiou V. P., Assimopoulou A. N., Samanidou V. F., Papadoyannis I. N. Recent advances in chemistry, biology and biotechnology of alkannins and shikonins. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006;10:2123–2142. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y.-H., Gan Y., Guo Z.-H., Xie S.-Q. Involvement of ROS/p38 signal pathway in shikonin-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells. Zhongguo Yaolixue Tongbao. 2011;27:864–867. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calonghi N., Pagnotta E., Parolin C., Mangano C., Bolognesi M. L., Melchiorre C., Masotti L. A new EGFR inhibitor induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;354:409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou Y., Guo T., Wu C. F., He X. A., Zhao M. H. Effect of shikonin on human breast cancer cells proliferation and apoptosis in vitro. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006;126:1383–1386. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.126.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kajimoto S., Horie M., Manabe H., Masuda Y., Shibayama-Imazu T., Nakajo S., Gong X. F., Obama T., Itabe H., Nakaya K. A tyrosine kinase inhibitor, β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin, induced apoptosis in human lung cancer DMS114 cells through reduction of dUTP nucleotidohydrolase activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1782:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor as a target for anticancer therapy. Oncologist. 2004;9:2–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-suppl_1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folkman J. What is the evidence that tumours are angiogenesis dependent? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990;82:4–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirte H. Novel developments in angiogenesis cancer therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2009;16:50–54. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i3.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontogiannopoulos K. N., Assimopoulou A. N., Dimas K., Papageorgiou V. P. Shikonin-loaded liposomes as a new drug delivery system: physicochemical characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011;113:1113–1123. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontogiannopoulos K. N., Assimopoulou A. N., Hatziantoniou S., Karatasos K., Demetzos C., Papageorgiou V. P. Chimeric advanced drug delivery nano systems (chi-aDDnSs) for shikonin combining dendritic and liposomal technology’. Int. J. Pharm. 2012;422:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J., Wei D., Zhuang H., Qiao Y., Tang B., Zhang X., Wei J., Fang S., Chen G., Du P., et al. Proteomic screening of anaerobically regulated promoters from salmonella and its antitumor applications. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2011;10:M111.009399. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pang X., Zhang L., Lai L., Chen J., Wu Y., Yi Z., Zhang J., Qu W., Aggarwal B. B., Liu M. 1′-Acetoxychavicol acetate suppresses angiogenesis-mediated human prostate tumor growth by targeting VEGF-mediated Src-FAK-Rho GTPase-signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:904–912. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mumper R. J., Hoffman A. S. The stabilization and release of hirudin from liposomes or lipid-assemblies coated with hydrophobically modified dextran. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2000;1:E3. doi: 10.1208/pt010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain R. K. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat. Med. 2003;9:685–693. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tirand L., Frochot C., Vanderesse R., Thornas N., Trinquet E., Pinel S., Viriot M. L., Guillemin F., Barberi-Heyob M. A peptide competing with VEGF (165) binding on neuropilin-1 mediates targeting of a chlorin-type photosensitizer and potentiates its photodynamic activity in human endothelial cells. J. Controlled Release. 2006;111:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim I. Y., Kang Y. S., Lee D. S., Park H. J., Choi E. K., Oh Y. K., Son H. J., Kim J. S. Antitumor activity of EGFR targeted pH-sensitive immunoliposomes encapsulating gemcitabine in A549 xenograft nude mice. J. Controlled Release. 2009;140:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L. K., Hou S. X., Mao S. J., Wei D. P., Song X. R., Lu Y. Uptake of folate-conjugated albumin nanoparticles to the SKOV3 cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2004;287:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]