Abstract

Little is known about changes in hemoglobin concentration early in the course of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and its subsequent relation to survival. We analyzed data for 40,410 HIV-infected adults on ART in Lusaka, Zambia. Our main exposure of interest was 6-month hemoglobin, but we stratified our analysis by baseline hemoglobin to allow for potential effect modification. Patients with a six-month hemoglobin <8.5 g/dL, regardless of baseline, had the highest hazard for death after six months (HR: 4.5; 95%CI: 3.3, 6.3). Future work should look to identify causes of anemia in settings such as ours and evaluat strategies for more timely diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Anemia, hemoglobin, HIV, antiretroviral therapy, Africa, Zambia

Introduction

The prevalence of anemia among HIV-infected adults in Africa is alarmingly high. Estimates range from 10 to 30%, depending on the hemoglobin (Hb) thresholds used and populations studied.1-4 Limited data are available regarding the commonest causes for anemia in these settings; however, they likely include drug toxicities, malaria, nutritional deficiencies, vitamin B12 deficiency, and various opportunistic infections.5

The association between an individual's Hb concentration at time of antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation and treatment response is well-documented. Numerous studies have shown low Hb to be a strong predictor of compromised clinical outcomes.3, 6-11 Following ART initiation, average Hb concentrations increase and the anemia incidence decreases,4 trends that are at least partially dependent on the drug combinations prescribed.1, 12 Recent findings from industrialized countries also suggest that changes in Hb concentrations at six months post-ART initiation may be associated with subsequent mortality.7 It is unknown, however, whether these observations can be extended to African populations. Given the high prevalence and varied etiologies of anemia in the region – alongside the great need for ART – the answer to this question could have important implications for optimized HIV care.

Methods

In this report, we examined the impact of early Hb change (i.e., within the first six months) on subsequent mortality. We analyzed data from a programmatic cohort of patients receiving HIV care and treatment in Lusaka, Zambia. This program and the care it provides have been described previously.3, 13 Since program inception, first-line regimens have consisted of a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (nevirapine or efavirenz) combined with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (lamivudine and either zidovudine or stavudine). Tenofovir and emtricitabine were introduced as alternative nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in July 2007.14 The decision to start patients on zidovudine, stavudine, or tenofovir has historically been based on national guidelines, with tenofovir being recommended as first choice for most patients since 2009. We note two exceptions due to medical contraindications: Hb less than 10 g/dL (for zidovudine) and creatinine clearance less than 50 mL/min (for tenofovir).

Our analysis cohort comprised treatment-naïve, HIV-infected adults (≥16 years) who initiated ART across 18 Lusaka sites between May 1, 2004 and April 30, 2010. We excluded patients who were not on treatment for at least six months; initiated or switched to a regimen containing a protease inhibitor (i.e. second line regimen) prior to six months; or had a missing Hb measurement at either ART initiation or six months into treatment.

Based on the 2004 Division of AIDS toxicity grading scale for HIV positive adults, Hb values were categorized as normal (>10.0 g/dL), mild anemia (8.5 – 10.0 g/dL), or moderate and severe anemia (<8.5 g/dL).15 Our main exposure of interest was Hb concentrations at six months following ART initiation. To allow for potential effect modification, we stratified our analysis by baseline Hb measurements as well. We used Cox proportional hazard models to determine associations with death after the initial six-month window. Patients with Hb measurements above >10.0 g/dL at ART initiation and six months follow-up were designated as the reference group. Our primary analysis was restricted to the cohort of patients with complete data for all variables of interest. Multivariate models were adjusted for age, sex, baseline body mass index (BMI), baseline CD4+ cell count, baseline clinical WHO staging, tuberculosis status, baseline ART regimen, and adherence based on a medication possession ratio at six months.16 In a secondary analysis, we used a multiple imputation approach to replace missing values. Separate multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were analyzed for each imputed dataset and results were combined to obtain hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

In a subset analysis, patients with Hb <10.0 g/dL and a documented mean corpuscular volume (MCV) at six months were further classified as having microcytic (<80 fL), normocytic (80-100 fL) or macrocytic anemia (>100 fL). We again used a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to determine associations with death. Patients with normocytic anemia were designated as the reference group in this secondary analysis.

Patient data available as of October 31, 2010 were considered. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Use of these observational data was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Zambia (Lusaka, Zambia) and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (Birmingham, AL, USA).

Results

Between May 1, 2004, and April 30, 2010, 73,016 HIV-infected adults initiated ART across participating Lusaka sites. By six months, 5,272 (7.2%) patients had died, 8,628 (11.8%) were lost to follow-up, and 357 (0.5%) initiated second-line therapy. Of the remaining 58,759 patients, 40,410 (68.8%) had Hb measurements at both baseline and six months, and were thus included in our analysis. Compared to those included in this analysis, patients with missing baseline and/or six-month Hb measurement had a lower median baseline CD4 count (140 vs. 146 cells/uL; p<0.01) and were less likely to demonstrate ≥ 95% ART adherence over the first six months of treatment (63.3% vs. 73.7%; p<0.01). We noted statistical differences in age, sex, BMI, clinical staging, and initial ART regimen between patients included and excluded from the analysis; however, they were not thought to be clinically meaningful. (Supplemental Digital Content 1)

In the analysis cohort, median follow-up was 22 months (IQR: 9-37) beyond the initial six-month window. Post-six month mortality was 1.59 deaths per 100 person-years (95% CI: 1.51-1.67). The median Hb at treatment initiation was 11.1 g/dL (IQR: 9.7, 12.5). Overall, 28,131 (69.6%) had Hb > 10 mg/dL; 8,121 (20.1%) were mildly anemic; and 4,158 (10.3%) were moderately or severely anemic. After six months of ART, the median Hb increased to 12.3 g/dL (IQR: 11.2, 13.4) and the overall proportions with mild anemia (n=3,030; 7.5%) or moderate to severe anemia (n=1,117; 2.8%) had decreased.

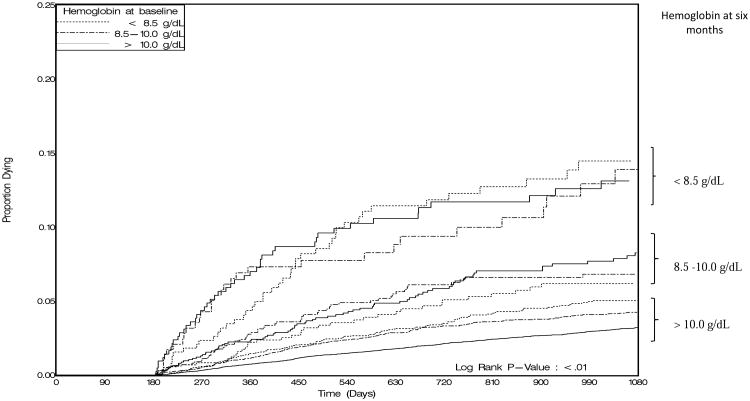

Regardless of their baseline hemoglobin concentration, patients with anemia at six months had consistently higher hazards for death compared to those with six-month Hb >10.0g/dL in our primary analysis (p<0.01; Figure 1). Moderate or severe anemia at six months was associated with a 4.5-fold (95% CI: 3.3, 6.3) increase in hazard of death when compared to patients with normal Hb concentrations at six months. The hazard for mildly anemic patients at six months was also higher compared to patients with normal Hb concentrations (AHR: 2.5; 95% CI: 1.9, 3.1). Among the nine subcategories of our stratified analysis, the three subcategories containing patients with a six-month Hb measurement less than 8.5 g/dL had the highest estimated hazard for death (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative probability of death stratified by anemia status at baseline and six months.

*Separate survival curves are plotted for nine subgroups determined by Hb concentrations at baseline and six months.

Table 1. Hemoglobin at baseline and six months and hazard of death after six months, adjusted HR (95% CI).

| Hb at six months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 10.0 g/dL | 8.5 – 10.0 g/dL | < 8.5 g/dL | ||

| Baseline HB | > 10.0 g/dL | 1.0 n=26,432; 65.4% | 2.6 (2.0 - 3.3) n=1,271; 3.2% | 4.5 (3.2 - 6.1) n=428; 1.0% |

| 8.5 – 10.0 g/dL | 1.3 (1.1 - 1.5) n=6,807; 16.8% | 2.4 (1.8 - 3.2) n=1,021; 2.5% | 4.6 (3.1 - 6.7) n=293; 0.7% | |

| < 8.5 g/dL | 1.4 (1.1 - 1.7) n=3,024; 7.5% | 1.9 (1.3 - 2.6) n=738; 1.8% | 5.4 (4.0 - 7.4) n=396; 1.1% | |

Multivariate analysis adjusted for the following covariates of interest: age, sex, CD4+ cell count, World Health Organization clinical stage, ART regimen at treatment initiation, active tuberculosis at time of treatment initiation, and adherence based on a medication possession ratio at six months

We then conducted a secondary analysis where missing values were replaced using a multiple imputation approach. We found that moderate or severe anemia at six months (AHR: 3.8; 95% CI: 3.2, 4.6) and mild anemia at six months (AHR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.8, 2.5) were consistently associated with increased in hazard of death compared to patients with normal Hb concentrations at six months.

Of the 4,147 patients diagnosed with anemia at six months, a six-month MCV measurement was available for 2,769 (66.8%). Among these patients, 1,314 (47.5%) had normocytic anemia; 804 had (29.0%) microcytic anemia; and 651 (23.5%) had macrocytic anemia. Macrocytic anemia was associated with a 1.3-fold (95%CI: 0.9-1.8) increased hazard for death when compared to normocytic anemia. Patients with microcytic anemia appeared to have a decreased hazard for death (AHR: 0.7; 95%CI: 0.5, 1.1). Neither, however, reached statistical significance.

Discussion

In this large African cohort, anemia six months after ART initiation was associated with higher risk for death, regardless of the baseline Hb measurement. We demonstrated elevated risk for death among patients who either develop anemia over the first six months of HIV treatment or have worsening disease over that window period. Similar trends have been observed among developed world cohorts.7 However, ours is the first to assess this relationship in an African setting, where the incidence and causes of anemia may differ greatly. These results reinforce the importance of continued Hb monitoring following initiation of ART, regardless of the regimen dispensed.

The association between low Hb concentrations at time of ART initiation and poor clinical outcomes among HIV-infected patients is well-documented. In an analysis of four sub-Saharan African cohorts, patients with severe anemia had a nearly four-fold higher risk of death in the first year of treatment compared to patients with no anemia.9 Similar findings have been shown in separate studies across Zambia,3 South Africa,11 Senegal,6 and Tanzania.8 To our knowledge, however, none have investigated post-initiation Hb concentrations and their relationship to subsequent mortality in resource-constrained settings.

Although ART has been shown to generally improve Hb levels,4 certain agents may have the opposite effect. Known side effects of zidovudine (ZDV), for example, include myelosuppression and macrocytic anemia. Although ZDV is commonly prescribed in our setting, our findings suggest that the incidence of anemia was not driven solely by unrecognized ZDV-related drug toxicity. Only 24% of all anemic patients at six months post-initiation had macrocytic anemia. It is important to note, however, that macrocytic anemia did appear to be associated with elevated risk for mortality, even if it did not meet pre-defined standards for statistical significance.

We recognize that the strong association between six-month Hb concentrations and mortality does not imply a causal relationship. It is possible that low Hb may only serve as marker for other underlying health conditions, ones that will ultimately be responsible for subsequent death. In Malawi, for example, Lewis and colleagues found that HIV-positive patients had higher incidences of serious but treatable conditions such as tuberculosis (38% vs. 14%) and bacteraemia (24% vs. 9%) compared to those who were HIV-negative.17 Rigorously conducted clinical trials are needed to determine whether proper diagnosis and treatment of anemia can lead to improved patient outcomes. Simple interventions such as vitamin supplementation (e.g., B12, folic acid) and/or antibiotic treatment for underlying infections could be used to prevent certain anemia types, particularly in settings where malnutrition and food insecurity are prevalent. Resources for more comprehensive laboratory evaluations could also improve patient outcomes, since treatment for anemia in Zambia is often empiric and may not accurately address the underlying cause of disease.

The key strength of this study was the availability of treatment outcomes and routinely collected Hb measurements for a large number of Zambian adults on ART. Even though the overall mortality rate after six months of HIV treatment was 1.59 deaths per 100 person-years, we were able to compare outcomes for different anemia classifications with precision. We also recognize several limitations. First, nearly one-third of patients had missing Hb measurements. We assumed that these measurements were missing at random and excluded observations from these patients in our primary analysis. Since patients with missing Hb measurements had a lower median CD4+ count when compared to our analysis cohort, it is possible that our findings are biased. In our secondary analysis, we replaced missing observations using multiple imputations. We were encouraged to find that the two results were similar, suggesting our primary analysis was robust despite the missing data. Second, our cohort comprised individuals who were living and receiving care in an urban African setting, where resources for healthcare are often limited. As a result, there may be concerns about external validity, particularly since the causes of anemia may vary greatly across different settings. Finally, in the absence of consistent standards for defining anemia in this population within the literature, we used established toxicity levels developed by the U.S. NIH's Division of AIDS. We recognize that other guidelines have higher thresholds for anemia (< 12 g/dL for females and < 13 g/dL for males);18 however, in our setting, clinical action is typically not taken unless a Hb concentration is less than 10 g/dL. We believe that our definition of anemia has utility for clinicians practicing in similar environments.

In summary, Hb response early in the course of ART was associated with higher subsequent mortality in this programmatic cohort. Our findings emphasize the importance of continued Hb monitoring following ART initiation, even for those on non-ZDV-based regimens. It is unclear whether treatment of anemia early in the course of ART may lead to improved clinical outcomes; however, such an approach appears reasonable and would clearly have some health benefit. Further work is needed to better understand the mechanisms behind anemia-associated mortality among ART patients. Resource-appropriate interventions should be designed and evaluated with the goal of improving public health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

** Chi-square test; ++ Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Ssali F, Stohr W, Munderi P, et al. Prevalence, incidence and predictors of severe anaemia with zidovudine-containing regimens in African adults with HIV infection within the DART trial. Antivir Ther. 2006;11(6):741–749. doi: 10.1177/135965350601100612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mugisha JO, Shafer LA, Van der Paal L, et al. Anaemia in a rural Ugandan HIV cohort: prevalence at enrolment, incidence, diagnosis and associated factors. Trop Med Int Health. 2008 Jun;13(6):788–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006 Aug 16;296(7):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiragga AN, Castelnuovo B, Nakanjako D, Manabe YC. Baseline severe anaemia should not preclude use of zidovudine in antiretroviral-eligible patients in resource-limited settings. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010 Nov 3;13:42. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005: WHO global database on anaemia. Geneva: WHO Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etard JF, Ndiaye I, Thierry-Mieg M, et al. Mortality and causes of death in adults receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Senegal: a 7-year cohort study. AIDS. 2006 May 12;20(8):1181–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226959.87471.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris RJ, Sterne JA, Abgrall S, et al. Prognostic importance of anaemia in HIV type-1-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy: collaborative analysis of prospective cohort studies. Antivir Ther. 2008;13(8):959–967. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johannessen A, Naman E, Ngowi BJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.May M, Boulle A, Phiri S, et al. Prognosis of patients with HIV-1 infection starting antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a collaborative analysis of scale-up programmes. Lancet. 2010 Aug 7;376(9739):449–457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, et al. Rapid scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy in 10,000 adults in Cote d'Ivoire: 2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS. 2008 Apr 23;22(7):873–882. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f768f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell EC, Charalambous S, Pemba L, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD, Fielding K. Low haemoglobin predicts early mortality among adults starting antiretroviral therapy in an HIV care programme in South Africa: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010 Jul 23;10:433. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyle G, Sawyer W, Law M, Amin J, Hill A. Changes in hematologic parameters and efficacy of thymidine analogue-based, highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis of six prospective, randomized, comparative studies. Clin Ther. 2004 Jan;26(1):92–97. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolton-Moore C, Mubiana-Mbewe M, Cantrell RA, et al. Clinical outcomes and CD4 cell response in children receiving antiretroviral therapy at primary health care facilities in Zambia. JAMA. 2007 Oct 24;298(16):1888–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi BH, Mwango A, Giganti M, et al. Early clinical and programmatic outcomes with tenofovir-based antiretroviral therapy in Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 May 1;54(1):63–70. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c6c65c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Division of AIDS table for grading the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events. Bethesda, MD, USA: Dec, 2004. pp. 1–21. Version 1.0. Clarification August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chi BH, Cantrell RA, Zulu I, et al. Adherence to first-line antiretroviral therapy affects non-virologic outcomes among patients on treatment for more than 12 months in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Epidemiol. 2009 Jun;38(3):746–756. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis DK, Whitty CJ, Walsh AL, et al. Treatable factors associated with severe anaemia in adults admitted to medical wards in Blantyre, Malawi, an area of high HIV seroprevalence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005 Aug;99(8):561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. WHO Technical Report Series 405. Vol. 1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1968. Nutritional Anemias: report of a WHO scientific group; p. 37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

** Chi-square test; ++ Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test