Abstract

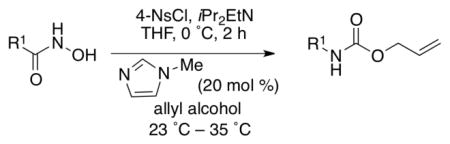

An efficient, one-pot, N-methylimidazole (NMI) accelerated synthesis of aromatic and aliphatic carbamates via the Lossen rearrangement is reported. NMI is a catalyst for the conversion of isocyanate intermediates to the carbamates. Moreover, the utility of arylsulfonyl chloride in combination with NMI minimizes the formation of often-observed hydroxamate-isocyanate dimers during the sequence. Under the present conditions, lowering of temperatures is also possible, enabling a mild protocol.

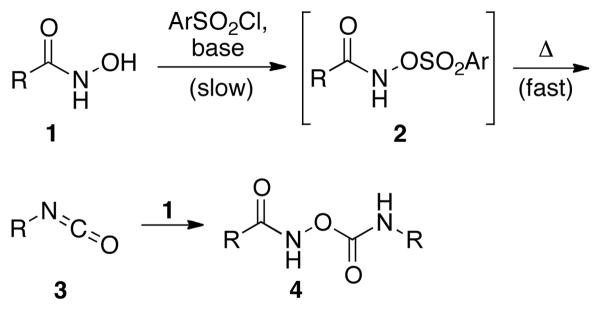

Conversion of carboxylic acid derivatives to the corresponding isocyanates is often achieved through oxidative rearrangements, such as the Hofmann or Curtius rearrangements.1 These approaches have been successfully employed to incorporate amine functionality into many substrates, including drug molecules.2 In addition, isocyanates – the direct product of the Lossen rearrangement – are useful precursors for the synthesis of carbamate and urea derivatives with pharmaceutical3 and agrochemical relevance.4 Despite the widespread use of these oxidative rearrangement methods, the use of strong hypervalent iodine reagents (Hofmann rearrangement) and potentially explosive azides (Curtius rearrangement) limit the application of these methods in large scale synthesis as well as for the derivatization of complex natural products with sensitive functional groups. As an alternative, the Lossen rearrangement5,6 provides access to isocyanates under somewhat more mild conditions. However, the application of the Lossen rearrangement is limited due to a competing side reaction, where the isocyanate 3 reacts with the hydroxamate 1, often yielding undesired pseudo-dimers like 4 (Scheme 1).5,6

Scheme 1.

Formation of the undesired dimeric side product during the Lossen rearrangement under thermal condition.

Efforts to prevent the dimerization reaction have included (a) attempted preformation of an activated hydroxamate and (b) performing the rearrangement at high temperature (65 to 85 °C).7 These conditions are typically unfavorable for incorporation of carbamate functionality into complex natural products or substrates that tend to undergo additional reactions under basic conditions (e.g., conjugated alcohols and beta-hydroxy-ketones). Despite the development of several Brønsted base,8 Brønsted acid,9 Lewis base10 and Lewis acid promoters11 for the synthesis of carbamates in this context, such methods still have limited application. To the best of our knowledge, an effective and mild Lewis base-catalyzed protocol for the synthesis of carbamates had been underexplored. Therefore, development of a Lewis base-dependent method would be a useful addition if advantages were apparent.

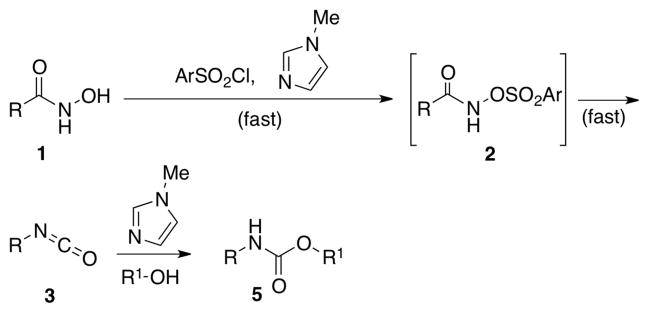

Thus, in an effort to develop a simple, low temperature method to promote the Lossen rearrangement, we hypothesized that a suitable nucleophilic catalyst might accelerate the sulfonyl-group transfer during the initial O-activation step. Such a catalyst would prevent the undesired consumption of 3, and hence the formation of dimeric side product 4 (Scheme 2). The same Lewis base, in principle, might also accelerate the reaction of the isocyanate intermediate in the presence of a suitable nucleophile, en route to carbamate products. Previously, our research group had shown that peptide-based catalysts containing the NMI moiety (e.g., π-methylhistidine) are quite effective for catalysis of sulfonyl group transfer reactions.12

Scheme 2.

Hypothesized NMI-catalyzed carbamate synthesis.

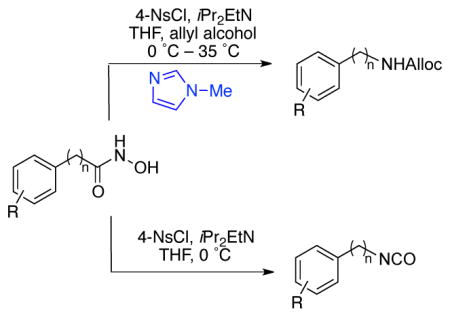

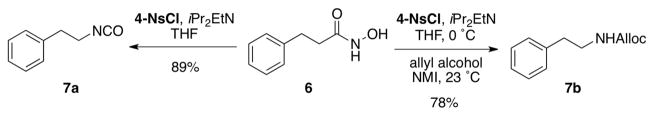

Our initial investigation began with examination of several arylsulfonyl reagents for the Lossen rearrangement of hydroxamic acid 6 in the presence and absence of NMI (Scheme 3). We found that under optimized conditions, sulfonyl chlorides, in particular 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride (4-NsCl) promoted the Lossen rearrangement of 6 very effectively at 0 °C within 2 h, yielding the isocyanate 7a with essentially complete conversion. Two aspects of this observation were surprising. First, it was unexpected that Lossen rearrangement to 7a would occur so efficiently and spontaneously at 0 °C. In contrast, when tosyl chloride is used as the sulfonylating agent, the reaction also results in isocyanate formation, but the reaction is not as effcient.13 Secondly, control experiments revealed that NMI was in fact not required for the formation of the isocyanate. Indeed, this may be due to the heightened reactivity of hydroxamic acids towards sulfonly chlorides, relative to the lower reactivity of aliphatic alcohols in this context.12 On the other hand, NMI proved essential for the conversion of 7a to carbamate 7b at ambient temperature (vide infra).

Scheme 3.

Conversion of hydroxamate 6 to either the isocyanate or the carbamate.

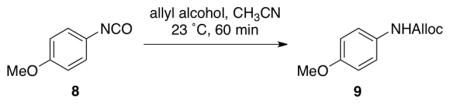

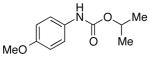

To gain more insight into NMI-catalyzed conversion of isocyanates to carbamates, we evaluated several possible Lewis bases (Table 1). We observed quite rapid and high conversion of isocyanate 8 to carbamate 9 in the presence of either NMI (entry 2; 10 mol %) or N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (entry 3; 10 mol %). At 23 °C, complete conversion of 8 was observed within 60 minutes with either catalyst. When the catalyst is omitted from the reaction, the product is observed in only 3% yield. It is also notable that neither imidazole (entry 4) nor pyridine (entry 5) are catalysts for the process. The NMI-catalyzed reaction also proceeds effectively at 0 °C, with a modest extension of the reaction time (~3 h), or with higher loading of NMI (20–30 mol %). The low temperature, together with the mild nature of the catalyst (e.g., pKa of NMI ~ 7.4), provide a very mild and practical method for the synthesis of carbamates.

Table 1.

Conversion of isocyanate 8 to the carbamate 9 using various nucleophilic catalysts.

10 mol % catalyst was used;

Isolated yield.

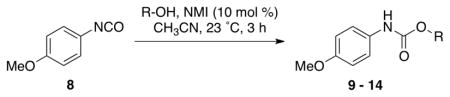

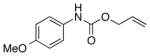

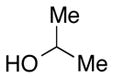

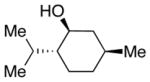

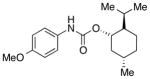

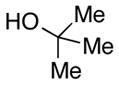

We then evaluated the versatility of this approach by exposure of isocyanate 8 to various alcohols under the optimized conditions (Table 2). Both primary (entries 1 and 2) and secondary alcohols (entries 3 and 4) work well, leading to the carbamates in high yield. Additionally, conversion of trans, trans-2,4-hexadiene-1-ol to the corresponding carbamate (entry 6) in excellent yield indicates that the reported method does not cause an elimination reaction of conjugated carbamate 14. Since many of the previously reported methods employ more harsh conditions, which could cause elimination of such carbamates,11d the present protocol provides a superior alternative. On the other hand, the reactivity of tertiary alcohol (entry 5) is noticeably low, with carbamate 13 formed in only 17% yield under the analogous reaction conditions, presumably due to the steric hindrance.

Table 2.

NMI-catalyzed carbamate synthesis using various alcohols.

2 equiv was used;

isolated yield;

3 equiv alcohol was used.

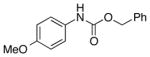

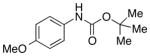

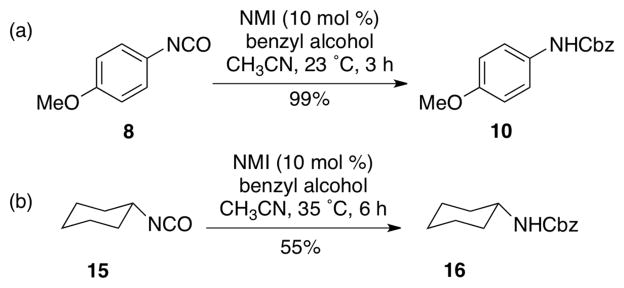

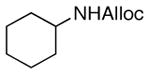

To demonstrate that NMI accelerates the reaction of both aromatic and aliphatic isocyanate, 4-methoxy phenyl isocyanate and cyclohexyl isocyanate were examined (Scheme 4). In each case, we observed efficient reactions, with the corresponding Cbz-carbamates 10 and 16 formed in 99% and 55% yield, respectively. We observed that cyclohexyl isocyanate 15 was less reactive and required slightly elevated temperature (35 °C) and a somewhat extended reaction time (6 h) to afford the observed result. We achieved an improved conversion of 15 with even longer reaction time (14 h; see Table 3, entry 12).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of aromatic and aliphatic carbamates

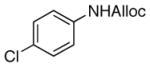

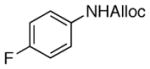

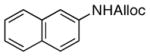

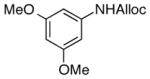

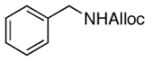

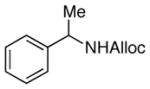

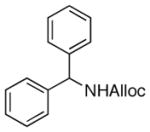

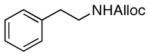

Table 3.

NMI-catalyzed synthesis of aryl and aliphatic carbamates.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yielda |

| 1 |

17

17

|

83% |

| 2 |

9

9

|

97% |

| 3 |

18

18

|

72% |

| 4 |

19

19

|

75% |

| 5 |

20

20

|

59% |

| 6 |

21

21

|

85% |

| 7 |

22

22

|

87% |

| 8 |

23

23

|

74% |

| 9 |

24

24

|

75% |

| 10 |

25

25

|

94% |

| 11 |

26

26

|

78% |

| 12 |

27

27

|

71% |

| 13 |

28

28

|

31%b |

isolated yield;

yield calculated over 3 steps.

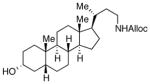

Since our initial goal was to develop an improved Lossen rearrangement protocol, we investigated the generality of the Lossen rearrangement protocol presented herein for a one-pot synthesis of carbamates. We synthesized various hydroxamic acid substrates from the corresponding carboxylic acid in one simple step (see Supporting Information).7d,14 Each hydroxamic acid was exposed to 4-NsCl (1.1 equiv), in the presence of iPr2EtN (2.5 equiv) at 0 °C for 2 h. This time frame appears adequate for complete conversion of the hydroxamate to the corresponding isocyanate. Subsequently, NMI and allyl alcohol were added to the reaction mixture to afford the desired carbamates (Table 3). This general procedure proved quite effective for a wide range of compounds, which are discussed in Table 3.

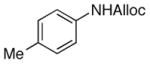

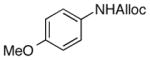

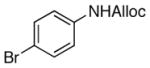

As shown in entries 1 – 7, aryl hydroxamic acids prove to be good substrates, undergoing the complete one-pot (two-step) transformation, giving the desired carbamate in good to excellent yields (59 – 97% yields). Our observations that the electron withdrawing substituents on the aromatic rings may lead to slower rearrangement, perhaps due to reduced electron density of the migrating group, is consistent with prior studies7d. The aliphatic hydroxamates (entries 8–13) also undergo rearrangement at 0 °C; however, the formation of aliphatic carbamates (23 – 28) were carried out at slightly elevated temperature (35 °C) to afford the desired carbamates in a convenient time frame.

The basis of the NMI-accelerated alcoholysis of isocyanates is not immediately clear. On the other hand, the role of nucleophilic catalysts such as DMAP for accelerating reactions of this nature seems an appropriate analogy.10a At this time, we do not have a clear understanding of the reaction mechanism to provide a definitive proposal for this aspect.

In conclusion, we have developed a quite mild and efficient catalytic approach for the conversion of hydroxamic acids to the corresponding carbamate in a one-pot operation. As the Lossen rearrangement provides a practical alternative approach for the modification of a carboxylic acid, the reported method can be used for oxidative rearrangement of carboxylic acids found in complex molecules as well as in sensitive substrates. Our group has been interested in developing chemical methods to modify complex natural products.15 Efforts will be taken to investigate the application of the reported method to introduce amine and carbamate functionalities into complex natural products in the near future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank colleagues at Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Drs. Y. Gu, N. Yin and Y. He) for support and insightful discussions. We are also grateful to the National Institutes of Health (R37 GM068649) and Yale University for partial support of this effort.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Procedures and characterization data. This information is available free of charge at: http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Shiori Y. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 6. Pergamon; Oxford: 1991. p. 795. [Google Scholar]; (b) Franklin EC. Chem Rev. 1934;14:219. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ishikawa H, Bondzic BP, Hayashi Y. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:6020. [Google Scholar]; (b) Maung KM, Wustmann DJ, Herzon SB. Chem Sci. 2011;2:2251. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Kasnanen H, Myllymaki MJ, Minkkila A, Kataja AO, Saario SM, Nevalainen T, Koskinen AMP, Poso A. Chem Med Chem. 2010;5:213. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Otrubova K, Ezzili C, Boger DL. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:4674. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li HQ, Lv PC, Yan T, Zhu HL. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:471. doi: 10.2174/1871520610909040471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Boijeaf Gennäs G, Mologni L, Ahmed S, Rajaratnam M, Marin O, Lindholm N, Viltadi M, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Scapozza L, Yli-Kauhaluoma J. Chem Med Chem. 2011;6:1680. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma HJ, Xie RL, Zhao QF, Mei XD, Ning J. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:12817. doi: 10.1021/jf1032284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Yale HL. Chem Rev. 1943;33:209. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hurd CD, Bauer L. J Am Chem Soc. 1954;76:2791. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bauer L, Exner O. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1974;13:376. [Google Scholar]; (d) Stolberg MA, Tweit RC, Steinberg GM, Wagner-Jauregg T. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:765. [Google Scholar]; (e) Pihuleac J, Bauer L. Synthesis. 1989:61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.For selected examples, see: Wallace RG, Barker JM, Wood ML. Synthesis. 1990:1143.Hoare DG, Olson A, Koshland DE., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:1638. doi: 10.1021/ja01008a040.

- 7.(a) Miller MJ, Loudon GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:5295. doi: 10.1021/ja00851a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stafford JA, Gonzales SS, Barrett DG, Suh EM, Feldman PL. J Org Chem. 1998;63:10040. [Google Scholar]; (c) Anilkumar R, Chandrasekhar S, Sridhar M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:5291. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dubé P, Nathel NFF, Vetelino M, Couturier M, Aboussafy CL, Pichette S, Jorgensen ML, Hardink M. Org Lett. 2009;11:5622. doi: 10.1021/ol9023387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillard RD, Poore GA, Easton NR, Sweeney MJ, Gibson WR. J Med Chem. 1968;11:1155. doi: 10.1021/jm00312a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Benalil A, Roby P, Carboni B, Vaultier M. Synthesis. 1991:787. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lammiman SA, Satchell RS. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 1974:877. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Höfle G, Steglich W, Vorbrüggen H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1978;17:569. [Google Scholar]; (b) Keyes RF, Carter JJ, Zhang X, Ma Z. Org Lett. 2005;7:847. doi: 10.1021/ol047406r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Duggan ME, Imagire JS. Synthesis. 1989:131. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nishikawa T, Urabe D, Tomita M, Tsujimoto T, Iwabuchi T, Isobe M. Org Lett. 2006;8:3263. doi: 10.1021/ol061123c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stock C, Bruckner R. Synlett. 2010:2429. [Google Scholar]; (d) Stock C, Bruckner R. Adv Synth Catal. 2012;354:2309. [Google Scholar]; (e) Spino C, Joly MA, Godbout C, Arbour M. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6118. doi: 10.1021/jo050712d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Francis T, Thorne MP. Can J Chem. 1976;54:24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiori KW, Puchlopek ALA, Miller SJ. Nat Chem. 2009;1:630. doi: 10.1038/nchem.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.TsCl, 3-NsCl and 4-NsCl gave complete conversion of 6 to 7a. TsF and 4-NsF gave no conversion to the desired isocyanate 7a.

- 14.Usachova N, Leitis G, Jirgensons A, Kalvinsh I. Synth Commun. 2010;40:927. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Fowler BS, Laemmerhold KM, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9755. doi: 10.1021/ja302692j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pathak TP, Miller SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6120. doi: 10.1021/ja301566t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lewis CA, Miller SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5616. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.