Abstract

Controlling the prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle at the pre-harvest level is critical to reduce outbreaks of this pathogen in humans. Multilayers of factors including the environmental and bacterial factors modulate the colonization and persistence of E. coli O157 in cattle that serve as a reservoir of this pathogen. Here, we report animal factors contributing to the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle. We observe the lowest number of E. coli O157 in Brahman breed when compared with other crosses in an Angus-Brahman multibreed herd, and bulls excrete more E. coli O157 than steers in the pens where cattle were housed together. The presence of super-shedders, cattle excreting >105 CFU/rectal anal swab, increases the concentration of E. coli O157 in the pens; thereby super-shedders enhance transmission of this pathogen among cattle. Molecular subtyping analysis reveal only one subtype of E. coli O157 in the multibreed herd, indicating the variance in the levels of E. coli O157 in cattle is influenced by animal factors. Furthermore, strain tracking after relocation of the cattle to a commercial feedlot reveals farm-to-farm transmission of E. coli O157, likely via super-shedders. Our results reveal high risk factors in the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle whereby animal genetic and physiological factors influence whether this pathogen can persist in cattle at high concentration, providing insights to intervene this pathogen at the pre-harvest level.

Introduction

The prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle herds (ranging 0–61%) [1], [2], [3], [4] is positively correlated to outbreaks of this pathogen causing severe diseases including hemorrhagic colitis (HC) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which can cause kidney failure and be fatal [3], [5]. Despite the implementation of government regulations and development of process interventions, food recalls and human illness related to E. coli O157 remain concerns around the world. Reducing the prevalence of this pathogen in cattle at the pre-harvest level has been highlighted recently as a critical control point to decrease the number of E. coli O157 entering the food chain [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Awareness of the risk factors that may increase the prevalence of E. coli O157 at the pre-harvest level can provide insights to develop intervention technologies to reduce its prevalence. Although risk factors on farms have been extensively studied from the bacterial perspectives, information regarding animal factors that may contribute to the prevalence of this pathogen is lacking. Here we identify high risk factors that significantly affect the prevalence of this pathogen in cattle.

Cattle are the primary reservoir of E. coli O157, and ground beef remains a significant source of foodborne transmission with other sources such as fresh vegetables [11]. Cattle that excrete more than 104 colony forming unit (CFU)/g of cattle feces have been defined as super-shedders [9], [12]. The super-shedders are responsible for about 90% of the total number of bacteria in the cattle herd [9], [12] and raise the prevalence of cattle infected with this pathogen on farms, making them a high risk factor at the pre-harvest level [6], [7], [13]. However, colonization of this pathogen in cattle is usually asymptomatic due to the lack of Shiga toxin receptor, globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), in cattle endothelial cells [14] that prevents elimination of super-shedding cattle contaminated with this pathogen at farms.

Several aspects influence the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle. The colonization of E. coli O157 at the rectal anal junction (RAJ) likely allows this pathogen to persist and shed high levels of bacteria for weeks or months [15], [16]. E. coli O157 primarily colonizes the mucosal epithelium at the RAJ [17], although it can be isolated from the gall bladder and along the gastrointestinal tract [18], [19]. More than 100 genes are involved in the colonization of the bovine intestine identified by genetic and biochemical analyses [20], including the E. coli O157 type III secretion system that enables the translocation of effector proteins into host cells and is required for colonization of cattle [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. Besides the bacterial factors, environmental factors are believed to contribute to the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle. The prevalence of E. coli O157 in feces fluctuates by season with the peak between late spring and early fall [26], [27], [28]. Water, soil, wild animals, insects, and dirty equipment are important vectors for spreading and transmission of E. coli O157 [29], [30], [31], [32]. Transmission of E. coli O157 by environmental sources is one of the challenges to the development of pre-harvest interventions.

Even though similar E. coli O157 strains are flourishing in the same herds with identical cattle husbandry practices applied, a portion of animals are considered super-shedders [9], [12], suggesting that the phenomenon of super-shedders are controlled by multilayers of factors. However, underling mechanisms by which certain animals (2–5% in herds) become super-shedders are not clearly understood. In early studies of animal inoculation with E. coli O157, inoculated orally with water, some animals were never colonized with this pathogen, indicating that some animals were resistant to E. coli O157 [10], [32]. On the basis of these observations, we hypothesized that, in addition to bacterial factors, animals play a critical role in modulating the colonization of this pathogen in animals. This study was designed to address the impact of animal genetic factors on E. coli O157 prevalence, as well as animal husbandry. Here, we present our findings that genetic and physiological factors of animals and animal husbandry practices significantly affect the prevalence of E. coli O157, suggesting potential intervention practices to reduce this pathogen entering to the food production chain.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Standard practices of animal care and use were applied to animals used in this project. Research protocols were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC number 201003744).

Animal Genetic Background

Cattle belonged to the Angus-Brahman multibreed herd at the University of Florida. The herd was established in 1988 to conduct long-term genetic studies in beef cattle under subtropical environmental conditions. Cattle were assigned to six breed groups according to the following breed composition ranges: calf breed group 1 = 100% to 80% of Angus, 0% to 20% of Brahman; calf breed group 2 = 79% to 60% of Angus, 21% to 40% of Brahman; calf breed group 3 = 62.5% of Angus, 37.5% of Brahman, calf breed group 4 = 59% to 40% of Angus, 41% to 60% of Brahman, calf breed group 5 = 39% to 20% of Angus, 61% to 80% of Brahman, and calf breed group 6∶19% to 0% of Angus, 81% to 100% of Brahman. Mating was diallel, i.e., sires from the 6 breed groups defined above were mated to dams of these same 6 breed groups [33]. Calves (n = 91) were kept at the Beef Research Unit of the University of Florida before weaning and were moved to the University of Florida Feed Efficiency Facility (UFEF) after weaning.

Cattle Maintenance

Angus, Brahman, and Angus × Brahman crossbred steers (n = 80, 253±38 kg) and bulls (n = 11, 345±29 kg) were housed in the UFEF at the North Florida Research and Education Center in Marianna, Florida for 97 days (From October 19, 2011 until January 24, 2012). Upon arrival (day 0) to the UFEF, cattle were fitted with electronic identification tags (Allflex USA Inc., Dallas-Fort Worth, TX) and were randomly allocated to 5 concrete floor pens of 108 m2 each with wood shavings bedding for a total of 18 animals per pen with the exception of one pen which contained 19 animals. The 11 bulls were allocated to only 2 of the 5 pens (one pen with 5 and another pen with 6 bulls). Cattle had ad libitum access to feed and water at all times and intake was monitored continuously via a GrowSafe system (GrowSafe Systems Ltd., Airdrie, Alberta, Canada). Each pen contained two GrowSafe nods, thus the mean stocking rate per node was 9 cattle. Cattle received a diet comprised of (DM basis) 34% ground bahiagrass hay, 31% corn gluten feed pellets, 31% soybean hulls pellets, 4% of supplement containing molasses, urea, vitamin and minerals. The diet was formulated to have 14.7% crude protein and 0.97 Mcal of Net Energy of gain/kg of diet dry matter.

Detection and Enumeration of E. coli O157

The presence or absence of E. coli O157 in swabs of the RAJ was determined as previously described with minor modifications [10]. Rectal anal junction swab samples were collected from 91 cattle at the UFEF and a commercial feedlot. Samples were taken to the lab on ice within 4 h of collection to minimize bacterial growth and further tested for microbiological identification. Swab samples were resuspended in 2 ml of Tryptic soy broth (Difco) and serially diluted in 0.1% (w/v) peptone. Two hundred microliters of diluted samples (neat, 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4) were then plated on MacConkey sorbitol agar (Difco) supplemented with cefixime (50 µg/liter; Lederle Labs, Pearl River, N.Y.) and potassium tellurite (2.5 mg/liter; Sigma) (CT-SMAC) to determine the number of E. coli O157 [34]. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h and typical E. coli O157 colonies (i.e., sorbitol-negative colonies and multiplex PCR positive, described below) were enumerated. The minimum detection limit of the direct plating procedure was approximately 10 CFU/swab. Enrichment was used for the presence or absence determinations on samples that did not yield E. coli O157 by direct plating. For this purpose, samples were enriched in TSB supplemented with novobiocin (20 µg/ml; Sigma) for 18 to 24 h at 37°C with shaking, and E. coli O157 was detected by direct plating after serial dilution (neat, 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, and 10−4) with 0.1% (w/v) peptone. Sorbitol-negative colonies were confirmed by multiplex PCR.

Multiplex PCR

Multiplex PCR was conducted to confirm E. coli O157. Bacterial strains used in this paper are listed (Table 1). E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 and DH5α were used as a positive and negative control of multiplex PCR, respectively. Primers were designed to detect stx1, stx2, hly, and rbfE (Table 2). stx1 and stx2 primers detected subunit A of Stx1 and Stx2, respectively. Each PCR wells contained 25 µl of reaction mix, comprised of 2.5 µl of 10X buffer, 0.5 µl of dNTP, 1 µl of Taq polymerase and a mixture of the 8 primers. PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min for pre-denature, 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min each 30 cycles, and 72°C for 10 min for a final extension. PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-EDTA buffer after electrophoresis.

Table 1. Strains used in this study.

| Strain name | Description | references |

| E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 | ATCC43895 | [37] |

| E. coli DH5α | Lab collection | |

| KCJ1220 | Isolated from medium-shedding animal in pen 17 | This study |

| KCJ1225 | Isolated from medium-shedding animal in pen 13 | This study |

| KCJ1231 | Isolated from super-shedding animal in pen 17 | This study |

| KCJ1237 | Isolated from medium-shedding animal in pen 15 | This study |

| KCJ1238 | Isolated from medium-shedding animal in pen 16 | This study |

| KCJ1242 | Isolated from low-shedding animal in pen 15 | This study |

| KCJ1244 | Isolated from low-shedding animal in pen 16 | This study |

| KCJ1252 | Isolated from super-shedding animal in pen 14 | This study |

| KCJ1254 | Isolated from medium-shedding animal in pen 14 | This study |

| KCJ1265 | Isolated from low-shedding animal in pen 13 | This study |

| KCJ1266 | Isolated from super-shedding animal in pen 13 | This study |

| KCJ1268 | Isolated from low-shedding animal in pen 14 | This study |

| KCJ1430 | Isolated from a commercial feedlot | This study |

| KCJ1432 | Isolated from a commercial feedlot | This study |

Table 2. Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Target | Name | Sequence (5′- 3′) | Orientation | Size (bp) |

| rfbE a | KCP57 | CGGACATCCA TGTGATATGG | F | 259 |

| KCP58 | TTGCCTATGTA CAGCTAATCC | R | ||

| stx1 b | KCP11 | TGTCGCATAGTGGAACCTCA | F | 655 |

| KCP12 | TGCGCACTGAGAAGAAGAGA | R | ||

| stx2 b | KCP13 | CCATGACAACG GACAGCAGTT | F | 477 |

| KCP14 | TGTCGCCAGTTA TCTGACATTC | R | ||

| hlyA b | KCP19 | GCGAGCTAAGCAGCTTGAAT | F | 199 |

| KCP20 | CTGGAGGCTGCACTAACTCC | R |

Subtyping of E. coli O157 Isolates Using Pulsed-field Gel Electrophoresis

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed to subtype farm isolates in accordance with PulseNet standardized laboratory protocol. A colony purified on CT-SMAC was grown overnight in a shaker in Luria Broth (LB) at 37°C. Concentration of cell suspension was adjusted to an optical density of 1.0 at 600 nm. Cells (400 µl) were mixed with 20 µl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml stock, Fisher Scientific) and 1% Sekem Gold agarose (Lonza). The mixture was placed into a well of disposable plug molds (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Agarose plugs were lysed in cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 and 1% Sarcosyl) for 2 h at 55°C with constant shaking at 170 rpm. Lysed plugs were washed one time with sterile distilled-water, followed by TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) twice at 55°C. Plugs were digested with 10 units of XbaI (New England BioLabs), and then electrophoresed using a CHEF Mapper (Bio-Rad Laboratories) under the following condition: 0.5 X Tris-Borate EDTA buffer at 14°C, 6 V/cm for 19 h, and an initial switch time from 2.16 s to 54.17 s. Lambda Ladder PFG Marker (New England BioLabs) was run as a size marker. The PFGE patterns were visualized by using GelDoc™ XR+ with Image Lab™ software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The banding patterns were analyzed with GelCompar II software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad InStat version 3.10. Differences among pens were analyzed by the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Tukey’s test. Proportions of the super-shedders between bulls and steers were compared by Fisher’s exact test. All data were expressed as mean ± standard error. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Prevalence of E. coli O157 in the Multibreed Cattle

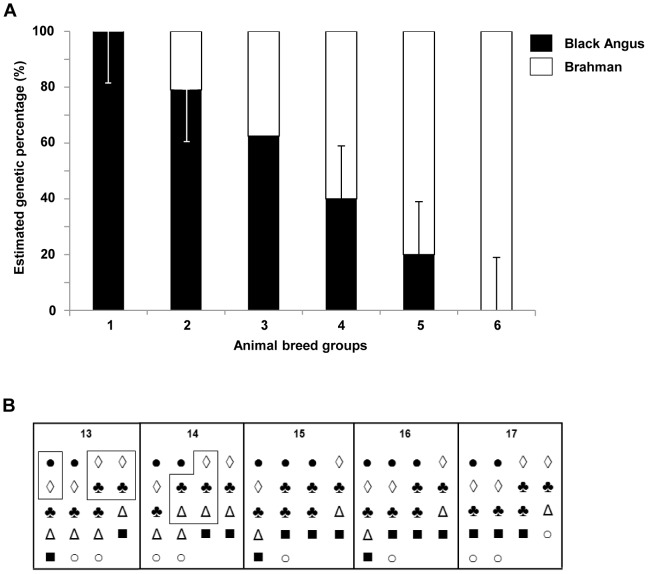

As a first step to understand the animal factors that may affect the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle, we enumerated this pathogen at the RAJ. A total of 91 animals were produced by the diallel mating system described previously [33] and assigned to six groups according to their estimated breed composition. As shown in figure 1A, calf breed group 1 contained the largest expected portion of genetic traits from Angus (100–80%) and the smallest expected portion from Brahman (0–20%). As the calf breed group numbers increase, the Angus portion decreases and Brahman portion increases. Thus, breed group 1 is more closely related to Angus while breed group 6 is more closely related to Brahman. Six different breed groups were randomly housed in 5 pens, but bulls were housed only in pen 1 and 2 to test if castration may affect the levels of this pathogen in the groups (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Estimated genetic backgrounds of animals used and housing in five pens.

(A) Cattle consisted of six Angus-Brahman multibred groups. Group 1 = 100% to 80% Angus, 0% to 20% Brahman; Group 2 = 79% to 60% Angus, 21% to 40% Brahman; Group 3 = 62.5% Angus, 37.5% Brahman, Group 4 = 59% to 40% Angus, 41% to 60% Brahman, Group 5 = 39% to 20% Angus, 61% to 80% Brahman, Group 6∶19% to 0% Angus, 81% to 100% Brahman. Bars indicate the expected portion of Angus and Brahman genetic traits in each breed group. (B) Animals were systemically housed in five pens according to their genetic background and sex. • is Calf breed group 1, ◊ is Calf breed group 2, ♣ is Calf breed group 3, Δ is Calf breed group 4, ▪ is Calf breed group 5, and ○ is Calf breed group 6. Bulls in pen 13 and 14 are boxed.

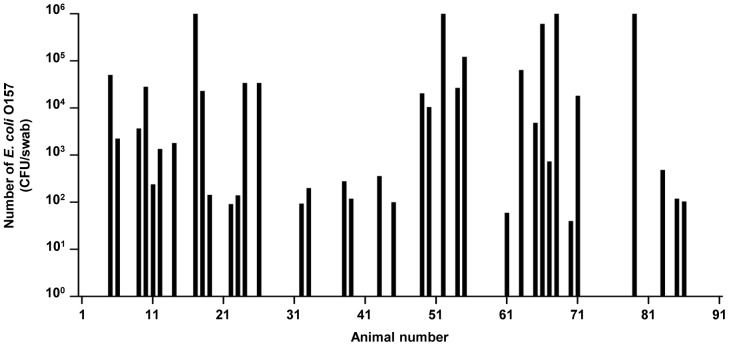

The total number of E. coli O157 from the RAJ swab samples was enumerated by a direct plating method without enrichment to monitor the real number of bacteria colonized on the RAJ. Swab samples were serial diluted before plated on CT-SMAC plate and incubated for 24 hours. Colonies with characteristic sorbitol negative color were picked and confirmed by using multiplex PCR. Out of 91 samples, 37 samples (40.66%) were found to be positive for E. coli O157 with a detection limit of 10 CFU/swab (Fig. 2). Samples that were negative for the direct plating method were enriched overnight followed by direct plating on CT-SMAC after serial dilution, but O157 was not detected from these samples (data not shown). The total number of E. coli O157 from the RAJ varied between animals, ranging from 101 to more than 106 (Fig. 2). The majority of positive samples contained this pathogen at 102–105 CFU/swab (n = 31; 83.78% of positive samples) and 6 cattle (16.21% of positive samples) contained more than 105 CFU/swab (Table 3). Cattle were categorized into four groups depending on the number of E. coli O157 shedding, non-shedder (<101/swab; n = 54; 59.34% of cattle), low-shedder (101–103 CFU/swab; n = 16; 17.59% of cattle), medium shedder (103–105 CFU/swab, n = 15; 16.48% of cattle), and super-shedder (>105 CFU, n = 6; 6.6% of cattle). Previously, super-shedder was defined as an animal that excretes E. coli O157 at more than 104 CFU/g of feces. However, in this study we defined a super shedder at excretions of more than 105 CFU/swab because previous results showed that RAJ swab samples were 10 fold higher than fecal samples [10].

Figure 2. The number of E. coli O157 isolated from rectal anal junction in cattle.

Rectal swabs were enumerated by direct plating on CT-SMAC and further identified by multiplex PCR detecting the stx1, stx2, rbfE, and hlyA genes. Cattle were designate as low-shedders (101–102 CFU), medium-shedders (103–104 CFU), and super-shedders (>105 CFU). Six out of 91 cattle were super-shedders, accounting for 6.6% of all calves. Limit of detection was 10 CFU in this direct plating method.

Table 3. Distribution of cattle based on the level of E. coli O157 counts.

| Number of cattle (%) | |||||

| Type of shedder | CFU/swab | Total | Bull | Steer | |

| Non-shedder | 0–101 | 54 (59.34) | 7 (63.64) | 47 (58.75) | |

| Low-shedder | 101–102 | 4 (4.40) | 0 (0) | 4 (5.00) | |

| 102–103 | 12 (13.19) | 1 (9.09) | 11 (13.75) | ||

| Medium-shedder | 103–104 | 5 (5.49) | 0 (0) | 5 (6.25) | |

| 104–105 | 10 (10.99) | 0 (0) | 10 (12.50) | ||

| Super-shedder | 105–106 | 2 (2.20) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (1.25) | |

| >106 | 4 (4.40) | 2 (18.18) | 2 (2.50) | ||

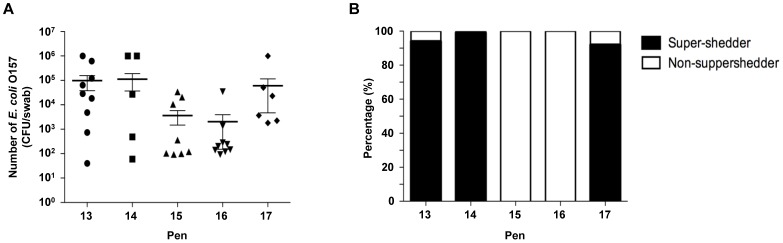

Presence of Super-shedders in Pens Increases the Total Number of Bacteria in Herds

It has been shown that the presence of super-shedders increases the prevalence of E. coli O157 in hides and carcass by enhancing transmission of this pathogen [6], [7], [13]. However, it is not well known if the super-shedders increase the total number of this pathogen in herds. We determined if there was a correlation between the presence of super-shedders and the level of E. coli O157 in different pens. Pen 13, 14, and 17 had 3, 2, and 1 super-shedder in the group of cattle, respectively (Fig. 3A), resulting in a higher number of E. coli O157 in the pens compared to the pens without super-shedders (pen 15 and 16). To understand the role of super-shedders in the transmission of E. coli O157, the total number of E. coli O157 bacteria excreted from super-shedders was calculated to determine what percentage of this pathogen was shed from super-shedders. E. coli O157 excreted from super-shedder accounted for more than 95% of total bacteria in the herds (Fig. 3B). These data confirm that super-shedders serve as a high risk factor for the transmission of this pathogen to other animals (Fig. 2 or Table 3). In addition, it suggests that removing super-shedders in cattle herds can be an effective method to reduce the number of this pathogen in herds, thus identification of super-shedders is a critical control point to reduce potential outbreaks caused by this pathogen.

Figure 3. Super-shedders increase the total number of E. coli O157 in pens with high density.

(A) The total number of E. coli O157 was calculated from individual animals in the five pens. Super-shedders increased the total number of E. coli O157 in the pens (pen 13, 14, and 17), and the average number of E. coli O157 was 100 fold less when a super-shedder was not identified in the pens (pen 15 and 16). The results are represented as mean ± SEM. (B) The percentage of E. coli O157 shed from super-shedders in the pens. Black bars represent the percentage of E. coli O157 isolated from super-shedders and white bars represent the percentage of E. coli O157 from non super-shedders.

Bulls are More Susceptible to E. coli O157 than Steers

To determine whether castration may affect the prevalence of E. coli O157, the number of this pathogen was counted in bulls and steers at the RAJ. The number of super-shedders was significantly different (P = 0.022) between bulls (27.27%, n = 11) and steers (3.75%, n = 80), indicating bulls are more susceptible to become super-shedders. However, it was remarkable that the prevalence of E. coli O157 in both cattle groups was similar at 36.36% and 41.25% respectively (Table 3). Taken together, even though steers and bulls are exposed to this pathogen in the same environment, probably by transmission from super-shedders, bulls are more likely to develop into super-shedders. This data suggest that steers may need to be separated from bulls to reduce total number of this pathogen in herds.

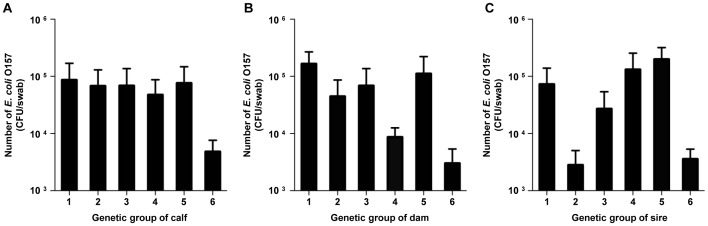

Brahman Cattle are More Resistant to E. coli O157

Results from previous inoculation studies of E. coli O157 with steers showed that certain cattle were resistant to this pathogen, despite repeated inoculation [32], suggesting animal factors were critical for colonization at the RAJ. We hypothesized that genetic factors play a significant role in the prevalence of E. coli O157 in animals. To assess the role of the genetic factors, we examined six different breed groups to identify if there is a correlation between breed groups and resistance to E. coli O157. The breed group 6 excreted the lowest number of E. coli O157 among the groups. As shown in Fig. 4A, the level of E. coli O157 was the lowest in breed group 6 compared to other groups, indicating that Brahman calves were more resistant to E. coli O157 than others. When calves were progeny of dams or sires from group 6, the calves had the lowest number of E. coli O157 compared to other groups (Fig. 4B and 4C). Notably, we could not observe a linear relationship between genetic composition and E. coli O157 resistance in calves, suggesting the resistance against pathogens may not be additive, but existing only in 100% Brahman cattle.

Figure 4. Brahmans are more resistant to E. coli O157 than other animals containing different genetic background.

All calves (A), dams (B), and sires (C) were classified into the same breed groups. Overall, resistance to O157 was shown in breed group 6.

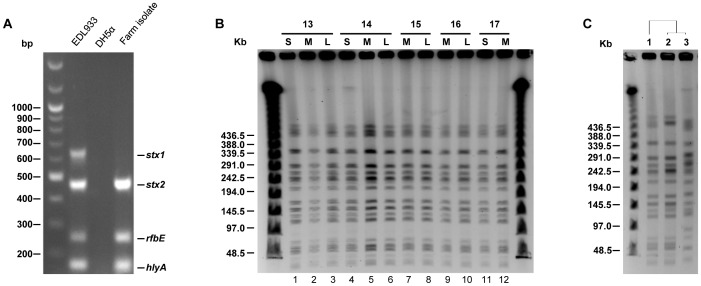

One Dominant E. coli O157 Strain was Prevalent Among Cattle

Although we observed that animal factors play key roles in determining the levels of E. coli O157 in cattle, we could not remove the possibility that a different level of this pathogen among cattle may have been mediated by different E. coli O157 strains. Bacterial factors are critical for prevalence and persistence of this pathogen in hosts; therefore, the different levels of E. coli O157 among cattle could have resulted by difference of bacterial strains rather than animal factors. Thus, we conducted molecular subtyping to eliminate the possibility that super-shedders carried a well-adapted E. coli O157 strain to cattle, while low shedders carried not-well-fitted strains. Strains isolated from low, medium, and super shedders of each pen were analyzed by multiplex PCR to compare strains. Multiplex PCR amplified the rfbE gene, which is specific for the O157 serotype, and three virulence genes, stx1, stx2, and hlyA. Unlike the EDL933 strain, all of the E. coli O157 isolates contained only stx2 and hlyA genes without stx1 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, PFGE analysis with XbaI digestion identified only one type of PFGE pattern in the pens (Fig. 5B). Strains isolated from different cattle shedding low, medium, or super number of E. coli O157 displayed 100% similarity, indicating they are the same strains. Only one homogenous E. coli O157 strain was dominant among the cattle, indicating one specific strain containing only the stx2 gene was originated from one common source. These results support that bacterial factors were not major factors making super-shedding cattle in this experiment.

Figure 5. All of the E. coli O157 isolates were identical, indicating the strain originated from one common source.

(A) Multiplex PCR was conducted using primers amplifying stx1, stx2, rbfE, and hlyA. Strains used were E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 (lane 1), DH5α (lane 2), and KCJ1266 (lane 3). (B) XbaI-digested PFGE analysis. Strains used were isolated from the pens indicated on top of the line from animals shed low, medium, and super number of E. coli O157. Strains used; lane 1: KCJ1266, lane 2: KCJ1225, lane 3: KCJ1165, lane 4: KCJ1152, lane 5: KCJ1154, lane 6: KCJ1168, lane 7: KCJ1137, lane 8: KCJ1142, lane 9: KCJ1138, lane 10: KCJ1144, lane 11: KCJ1131, lane 12: KCJ1120 (C) The E. coli O157 strain isolated from animals raised at a commercial feedlot facility was probably transmitted from super-shedders. XbaI-digested PFGE analysis was conducted using the strains isolated from a super-shedder at NFREC and two animals at a commercial feedlot facility. Strains used; lane 1: KCJ1266, lane 2: KCJ1430, lane 3: KCJ1432.

Farm-to-farm Transmission of E. coli O157 via Animals

After the pen study at the NFREC, 80 steers were transported to a commercial feedlot X, and we traced the dominant E. coli O157 strain, which was first identified at the NFREC, to study if farm-to-farm transmission is mediated by cattle. After six months in feedlot X, we collected rectal swab samples (n = 44) from cattle used in the pen study and additional rectal swab samples (n = 19) were collected from random cattle raised in the feedlot. Swab samples were directly, without enrichment, plated on CT-SMAC plate and E. coli O157 strains were isolated. Sorbitol negative colonies were further identified by multiplex PCR and PFGE was conducted to evaluate similarity among strains. Unexpectedly, we identified only 2 steers that carried E. coli O157 strains, which were positive for rbfE, stx1, stx2, and hlyA. This is an unexpected result because normally the prevalence of E. coli O157 is high at feedlots compared to cattle on pasture. It is not known at this time point why the prevalence of E. coli O157 in feedlot X was very low compared to previous studies. However, we isolated the same E. coli O157 strain, which was dominant at NFREC, from the E. coli O157 positive cattle in feedlot X. As shown in Fig. 5C, one strain had 96.6% similarity, suggesting this strain probably originated from cattle transported from NFREC. It is not known at this time whether the strain originated from super-shedders or not, although it is likely that the strain originated from the super-shedders because they accounted for 90% of total bacteria at NFREC. It is noteworthy that we also isolated one strain showing 70.2% similarity compared to the dominant NFREC strain that may have originated from other sources, probably from cattle in feedlot X because it was not existing at NFREC. Therefore, these data strongly support our hypothesis that cattle transmit pathogens between farms and can be a critical control point to intervene E. coli O157 at the pre-harvest level.

Discussion

We report here the role of animal and environmental factors in the prevalence of E. coli O157. In addition to the bacterial factors, animal genetic and physiological factors contribute to the prevalence of this pathogen in cattle. Brahman breed among the Angus-Brahman multibreed excreted the lowest level of E. coli O157, suggesting this breed is less prone to colonization of this pathogen. Bulls were more susceptible for colonization of this pathogen when compared with steers. These data indicate animal factors significantly contribute to the generation of super-shedders. The presence of super-shedders increased the number of bacteria in the pens and cattle. Super-shedders found in 6.6% of total cattle were responsible for more than 90% of the total number of pathogen in herd, increasing the chance of animal-to-animal and farm-to-farm transmission by either direct or indirect contact.

PFGE results from the commercial feedlot X isolates were in agreement with the data acquired from the pen isolates at the NFREC (Fig. 5C). The E. coli O157 strains isolated from the commercial feedlot X had high similarity, 96.6%, compared to the strains isolated from the NFREC dominant strain, indicating the commercial feedlot isolates were clonal variants of NFREC strain. Interestingly, we also isolated E. coli O157 showing lower similarity (70.2%) compared to the NFREC strains, indicating cattle likely acquired this strain from other cattle at the commercial feedlot X. Although it is plausible that this strain originated from NFREC, we believe that this strain was introduced from the commercial feedlot X. Taken together our data demonstrate the farm-to-farm transmission of E. coli O157 via cattle.

In addition to our data showing the transmission of E. coli O157 strains between farms, we observed a profound effect on animal-to-animal transmission of E. coli O157 strains in the pens. E. coli O157 is present in cattle at the prevalence ranging from 0% to 61% [3]; however, the prevalence of this pathogen at NEFREC farm was 40.66% (37 of 91 cattle). Furthermore, when we investigated the prevalence of E. coli O157 from grazing cattle at the same farm (i.e., NFREC), prevalence of this pathogen was 1.1% (1 out of 91 animals; Oh and Jeong’s unpublished data). Although the high prevalence of E. coli O157 in the pens could be mediated by other risk factors such as transmission vectors (i.e., wild animals, insects, and soil) and diet, it is unlikely because the two groups of cattle were raised in the same environmental conditions, except cattle density (pen vs. pasture). Previous studies [10], [32] showed that contaminated water could be a major source for E. coli O157 contamination in the confined environment; however, water was negative for E. coli O157 at NFREC (data not shown), eliminating the possibility that the cattle in the pans were contaminated via water. Thus, this unusual high prevalence of E. coli O157 was probably caused by the high density of cattle in the pens that may increase animal-to-animal transmission. Taken together cattle were probably the major source of E. coli O157 contamination via animal-to-animal transmission, and we suggest that maintaining cattle at the high density in the pens likely in part increased the prevalence of E. coli O157.

Based on an extensive E. coli O157 enumeration analysis, we have identified heterogeneous levels of this pathogen among cattle. Six cattle carried high level of E. coli O157 (>105 CFU/swab) that corresponds to the top 6.6% and 59.34% of cattle did not carry this pathogen even though they were housed in the same pens. Consistent with these data, previous research has shown that some cattle harbor and shed E. coli O157 at higher concentration than others [2], [6], [12]. In this study, we observed the role of super-shedders at high cattle density. Super-shedders were present in 3 pens, and the total number of bacteria in those pens was about 55 fold higher than pens without super-shedders. Super-shedders were responsible for more than 90% of the total number of pathogen in the pens. These data suggest that a super-shedder could increase not only the mean level of O157 among cattle but also the risk of E. coli O157 transmission to other cattle. Thus, identification and segregation of super-shedders from uninfected cattle may be a practical strategy to reduce the E. coli O157 prevalence in cattle and human disease.

Previous research has shown that bacterial factors may determine super-shedders by showing that diverse E. coli O157 strains were observed, but a few of them with particular phage types such as PT 21/28 are more likely to associate with super-shedding cattle via alteration in gene expression of E. coli O157 [9]. Unlike the previous findings, our data indicated that only one type of E. coli O157 strains was predominant among cattle in 37 cattle without bacterial strain preference (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that animal factors likely determine the colonization or shedding of this pathogen, but not bacterial factors.

We obtained multiple pieces of data indicating that the levels of E. coli O157 in cattle were modulated by multiple factors. These data include genetic factors (Fig. 4), physiological characteristics (i.e., castration, Table 3), and cattle density. Among the six breed groups examined, calves in the breed group 6 excreted the lowest number of E. coli O157. In addition, super-shedders were not identified in the group 6. As the breed group 6 was composed of Brahman and high percent Brahman cattle, it is reasonable to conclude that Brahman carry genetic factors that confer resistance against E. coli O157. Our findings are supported by a previous study where Riley et al. [35] found that 17.3% of Angus beef cattle (n = 52) were positive for E. coli O157 while 10.1% of Brahman (n = 109) beef cattle were positive with this pathogen by using an overnight enrichment method. The finding suggested that breed difference might affect the prevalence of E. coli O157 in the herd. Further studies regarding identification of genetic loci that confer resistance to E. coli O157 shedding and colonization will give us insights to develop intervention technologies to reduce E. coli O157 at the pre-harvest levels.

In addition to the genetic factors, castration decreased the susceptibility of male calves against this pathogen (Table 3). This was supported by data showing that 27.27% of bulls were super-shedders, whereas only 3.75% of steers were super-shedders. However, prevalence and colonization of E. coli O157 is probably influenced by many factors including rumen microflora [36], age [2], immune stress, the amount of feed intake, and unknown animal factors; thus, genetic variation and castration are likely associated with the prevalence of E. coli O157 directly or indirectly. Further studies, including identification of genetic loci, will be necessary to identify animal factors that directly govern the prevalence of pathogens. Our principal finding from this study is that animal factors, including genetic factors and castration, influence the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle. Super-shedders play a critical role in animal-to-animal and farm-to-farm transmission of E. coli O157. Identification of animal factors and controlling super-shedders will undoubtedly contribute to the development of intervention technologies to reduce outbreaks caused by this pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mara Brueck, Matthew Taylor, and Drs. Je Chul Lee, Won Sik Yeo, Man Hwan Oh, and Sung Cheon Hong for the technical assistance.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, and Emerging Pathogens Institute at University of Florida, grants to KCJ. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Besser RE, Lett SM, Weber JT, Doyle MP, Barrett TJ, et al. (1993) An outbreak of diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fresh-pressed apple cider. Jama 269: 2217–2220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cray WC Jr, Moon HW (1995) Experimental infection of calves and adult cattle with Escherichia coli O157:H7. Applied and environmental microbiology 61: 1586–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elder RO, Keen JE, Siragusa GR, Barkocy-Gallagher GA, Koohmaraie M, et al. (2000) Correlation of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 prevalence in feces, hides, and carcasses of beef cattle during processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 2999–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shere JA, Bartlett KJ, Kaspar CW (1998) Longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 dissemination on four dairy farms in Wisconsin. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 1390–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nataro JP, Kaper JB (1998) Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli . Clinical microbiology reviews 11: 142–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arthur TM, Brichta-Harhay DM, Bosilevac JM, Kalchayanand N, Shackelford SD, et al. (2010) Super shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by cattle and the impact on beef carcass contamination. Meat science 86: 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arthur TM, Nou X, Kalchayanand N, Bosilevac JM, Wheeler T, et al. (2011) Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on cattle hides. Applied and environmental microbiology 77: 3002–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Callaway TR, Carr MA, Edrington TS, Anderson RC, Nisbet DJ (2009) Diet, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and cattle: a review after 10 years. Curr Issues Mol Biol 11: 67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chase-Topping ME, McKendrick IJ, Pearce MC, MacDonald P, Matthews L, et al. (2007) Risk factors for the presence of high-level shedders of Escherichia coli O157 on Scottish farms. J Clin Microbiol 45: 1594–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jeong KC, Kang MY, Kang J, Baumler DJ, Kaspar CW (2011) Reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 shedding in cattle by addition of chitosan microparticles to feed. Applied and environmental microbiology 77: 2611–2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rangel JM, Sparling PH, Crowe C, Griffin PM, Swerdlow DL (2005) Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982–2002. Emerging infectious diseases 11: 603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matthews L, Low JC, Gally DL, Pearce MC, Mellor DJ, et al. (2006) Heterogeneous shedding of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle and its implications for control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103: 547–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arthur TM, Keen JE, Bosilevac JM, Brichta-Harhay DM, Kalchayanand N, et al. (2009) Longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in a beef cattle feedlot and role of high-level shedders in hide contamination. Applied and environmental microbiology 75: 6515–6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lingwood CA (1996) Role of verotoxin receptors in pathogenesis. Trends in microbiology 4: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lim JY, Li J, Sheng H, Besser TE, Potter K, et al. (2007) Escherichia coli O157:H7 colonization at the rectoanal junction of long-duration culture-positive cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 1380–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis MA, Rice DH, Sheng H, Hancock DD, Besser TE, et al. (2006) Comparison of cultures from rectoanal-junction mucosal swabs and feces for detection of Escherichia coli O157 in dairy heifers. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 3766–3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Naylor SW, Low JC, Besser TE, Mahajan A, Gunn GJ, et al. (2003) Lymphoid follicle-dense mucosa at the terminal rectum is the principal site of colonization of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the bovine host. Infection and immunity 71: 1505–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jeong KC, Kang MY, Heimke C, Shere JA, Erol I, et al. (2007) Isolation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from the gall bladder of inoculated and naturally-infected cattle. Vet Microbiol 119: 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keen JE, Laegreid WW, Chitko-McKown CG, Durso LM, Bono JL (2010) Distribution of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli O157 in the gastrointestinal tract of naturally O157-shedding cattle at necropsy. Applied and environmental microbiology 76: 5278–5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dziva F, van Diemen PM, Stevens MP, Smith AJ, Wallis TS (2004) Identification of Escherichia coli O157 : H7 genes influencing colonization of the bovine gastrointestinal tract using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology 150: 3631–3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abe A, Heczko U, Hegele RG, Brett Finlay B (1998) Two enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secreted proteins, EspA and EspB, are virulence factors. The Journal of experimental medicine 188: 1907–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bretschneider G, Berberov EM, Moxley RA (2007) Reduced intestinal colonization of adult beef cattle by Escherichia coli O157:H7 tir deletion and nalidixic-acid-resistant mutants lacking flagellar expression. Veterinary microbiology 125: 381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dean-Nystrom EA, Bosworth BT, Moon HW, O’Brien AD (1998) Escherichia coli O157:H7 requires intimin for enteropathogenicity in calves. Infection and immunity 66: 4560–4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sharma VK, Sacco RE, Kunkle RA, Bearson SM, Palmquist DE (2012) Correlating levels of type III secretion and secreted proteins with fecal shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cattle. Infection and immunity 80: 1333–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sheng H, Lim JY, Knecht HJ, Li J, Hovde CJ (2006) Role of Escherichia coli O157:H7 virulence factors in colonization at the bovine terminal rectal mucosa. Infection and immunity 74: 4685–4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barkocy-Gallagher GA, Arthur TM, Rivera-Betancourt M, Nou X, Shackelford SD, et al. (2003) Seasonal prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, including O157:H7 and non-O157 serotypes, and Salmonella in commercial beef processing plants. J Food Prot 66: 1978–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laegreid WW, Elder RO, Keen JE (1999) Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in range beef calves at weaning. Epidemiol Infect 123: 291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heuvelink AE, van den Biggelaar FL, de Boer E, Herbes RG, Melchers WJ, et al. (1998) Isolation and characterization of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 strains from Dutch cattle and sheep. J Clin Microbiol 36: 878–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferens WA, Hovde CJ (2011) Escherichia coli O157:H7: animal reservoir and sources of human infection. Foodborne pathogens and disease 8: 465–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Franz E, Semenov AV, van Bruggen AH (2008) Modelling the contamination of lettuce with Escherichia coli O157:H7 from manure-amended soil and the effect of intervention strategies. Journal of applied microbiology 105: 1569–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Franz E, van Bruggen AH (2008) Ecology of E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica in the primary vegetable production chain. Critical reviews in microbiology 34: 143–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shere JA, Kaspar CW, Bartlett KJ, Linden SE, Norell B, et al. (2002) Shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dairy cattle housed in a confined environment following waterborne inoculation. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 1947–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elzo MA, West RL, Johnson DD, Wakeman DL (1998) Genetic variation and prediction of additive and nonadditive genetic effects for six carcass traits in an Angus-Brahman multibreed herd. J Anim Sci 76: 1810–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zadik PM, Chapman PA, Siddons CA (1993) Use of tellurite for the selection of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O157. J Med Microbiol 39: 155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Riley DG, Gray JT, Loneragan GH, Barling KS, Chase CC Jr (2003) Escherichia coli O157:H7 prevalence in fecal samples of cattle from a southeastern beef cow-calf herd. Journal of food protection 66: 1778–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao T, Doyle MP, Harmon BG, Brown CA, Mueller PO, et al. (1998) Reduction of carriage of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cattle by inoculation with probiotic bacteria. Journal of clinical microbiology 36: 641–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perna NT, Plunkett G, 3rd, Burland V, Mau B, Glasner JD, et al (2001) Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409: 529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Valadez AM, Debroy C, Dudley E, Cutter CN (2011) Multiplex PCR detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains belonging to serogroups O157, O103, O91, O113, O145, O111, and O26 experimentally inoculated in beef carcass swabs, beef trim, and ground beef. Journal of food protection 74: 228–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bai J, Shi X, Nagaraja TG (2010) A multiplex PCR procedure for the detection of six major virulence genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Journal of microbiological methods 82: 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]