Abstract

This research aimed to validate the specificity of the newly developed nanobeacon for imaging the Thomsen-Friedenreich (TF) antigen, a potential biomarker of colorectal cancer. The imaging agent is comprised of a submicron-sized polystyrene nanosphere encapsulated with a Coumarin 6 dye. The surface of the nanosphere was modified with peanut agglutinin (PNA) and poly(N-vinylacetamide (PNVA) moieties. The former binds to Gal-β(1–3)GalNAc with high affinity while the latter enhances the specificity of PNA for the carbohydrates. The specificity of the nanobeacon was evaluated in human colorectal cancer cells and specimens, and the data was compared with immunohistochemical staining and flow cytometric analysis. Additionally, distribution of the nanobeacon in vivo was assessed using an “ intestinal loop” mouse model. Quantitative analysis of the data indicated that approximately 2 μg of PNA were detected for each mg of the nanobeacon. The nanobeacon specifically reported colorectal tumors by recognizing the tumor-specific antigen through the surface-immobilized PNA. Removal of TF from human colorectal cancer cells and tissues resulted in a loss of fluorescence signal, which suggests the specificity of the probe. Most importantly, the probe was not absorbed systematically in the large intestine upon topical application. As a result, no registered toxicity was associated with the probe. These data demonstrate the potential use of this novel nanobeacon for imaging the TF antigen as a biomarker for the early detection and prediction of the progression of colorectal cancer at the molecular level.

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed type of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States 1. Of particular note, the incidence of colorectal cancer in Western countries is high, such that approximately half of those in the Western population will develop some form of colorectal tumor by age 70 2. While the occurrence of colorectal cancer is lower in Japan, it has increased steadily in recent years. In fact, colorectal cancer deaths now rank as the third highest cause of mortality among cancer deaths in Japan (12%) 3. While treatment of colorectal cancer during its early stage is less complicated, progression of the disease in the later stage, including metastasis and the spread of tumor cells to distant parts of the body, increases treatment complexity and is often associated with poor prognosis and death. Currently, the key element in the control, prevention and treatment of this disease is recognition of its early symptoms. In that regard, colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy are considered the gold standards for early detection of the onset of this disease. Statistics in the past three decades have indicated decreased mortality from colorectal cancer as a result of earlier diagnosis and improved treatment modalities 4. Yet since colonoscopy lacks the ability to detect cancer at the molecular level, early detection remains a significant challenge since initial tumor-derived changes are particularly slight throughout the large intestine. In contrast, molecular imaging may provide a robust approach to detecting cancer owing to its direct coupling to the underlying molecular-level development of the disease. Moreover, since molecular imaging methods can detect functional variations in tissue as opposed to structural changes, so they can highlight lesions focally by leveraging high target-to-background ratios 5.

Several approaches have been used to image biomarkers of colorectal cancer utilizing optical imaging. For example, Kimberley et al. developed a peptide indentified through differential phage display that can bind specifically to α5β1-, which is upregulated in colorectal cancer 6. The probe was effective in detecting tumors in the submucosa using a mouse endoscopic imaging system. In a similar approach, Hsiung et al. 7 reported the use of phage display to develop a specific peptide able to recognize dysplastic colonocytes. After labeling the peptides with Fluorescein, the topically applied peptide could detect dysplastic colonocytes with 81% sensitivity and 82% specificity using confocal microendoscopy 7.

In this work, we hypothesize that the integration of optical imaging with nanotechnology and probe development has the potential to improve the detection of colorectal cancer, especially if the target is overexpressed in the extracellular membrane. One of the potential molecular biomarkers associated with the development and progress of colorectal cancer is the Thomsen-Friedenreich (TF) antigen (galactose β1-3 N-acetylgalactosamine α-). TF antigen expression correlates with conventional histopathological parameters of malignancy 8. Biopsy samples from patients showed that the TF antigen is overexpressed by hyperplastic and neoplastic colon cancers while its expression is attenuated in normal mucosa 9. It has further been shown that TF-associated cancer is a marker of poor prognosis for patients with colon and gastric cancer, and it indicates cancer risk for those with ulcerative colitis 10. Therefore, it is plausible to assume that TF antigens are specific and can be used as a target for colorectal cancer imaging. The ubiquitous association of the TF antigen with tumors 11, 12 is an ideal in vivo antigen for early detection and assessment of tumor response during therapy. Additionally, epithelial cancer cells exhibit enhanced cell surface expression of TF, a property that makes it an assessable target for imaging.

A family of lectins that originated from dietary materials that includes Arachis hypogaea (peanut agglutinin (PNA)) has demonstrated high binding affinity to luminal TF 13. As a result, PNA histochemistry has often been applied for the in vitro detection of TF antigen-associated human colorectal tissue to differentiate a normal colon from its cancerous counterpart 14. The TF-specific PNA has been shown to bind to malignant transformation on colon tissue 15. In most of the work conducted, lectins/PNA were tagged with either Fluorescein or peroxidase for imaging using fluorescent microscopy or histochemistry, respectively 16. For in vivo application, a number of efforts have also been taken to label specific monoclonal antibodies against TF disaccharide antigens with 111In and 99Tc for single photon emission computed tomography imaging 17. In a different approach, we developed a specific probe for the topical imaging of TF antigens in the colon by employing nanotechnology. The successful design and development of nanomaterials using diversified graft copolymers has implications for both target-guided drug delivery and imaging platforms. In either application, the nanospheres produced in our laboratory are made of hybrid copolymers comprised of a hydrophobic polystyrene backbone coated with hydrophilic polyvinyl chains on the surface. This design offers several advantages, such as (i) an enhanced amphiphilic property that promotes distribution of the probe across biological barriers in vivo; (ii) ease of fine-tuning overall particle size by adjusting the ratio of the polystyrene inner core to the hydrophilic polyvinyl chains; and (iii) the ability to incorporate small hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules, such as drugs or probes into the hydrophobic core and onto the hydrophilic surface layer, respectively, through physicochemical interactions. The probe consists of Coumarin 6 dye encapsulated in the polystyrene central core. The surface of the polystyrene particle was derivatized with poly(methacrylic) acid (PMAA) and poly(N-vinyl acetamide) (PNVA). Here, the former is used to attach PNA through covalent bonding while the latter helps reduce non-specific interaction with the mucous layer of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Studies conducted previously by our group showed that PNVA is a hydrophilic and nonionic polymer that induced thick water layers which prevent PNVA-coated nanobeacons from interacting with the mucous membrane of the GI tract 18–20. In this work, we demonstrated that the nanobeacon probe can be used for topical application without the potential for biodistribution or toxicity to major organs in an orthotopic mouse model. Additionally, we validated the specificity of the probe on human colorectal cancer tissues. This work demonstrates that the probe (i) can specifically recognize TF antigen-specific tumors in human tissues and (ii) when distributed topically, it is not absorbed by the intestine, which obviates any systemic distribution-associated toxicity. Taken together, our data suggest that the nanobeacon has significant potential for use in endoscopic imaging of colorectal cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Coumarin 6 and PNA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich while N-vinylacetamide (NVA) monomers were kindly provided by Showa Denko Co. (Tokyo, Japan) as a gift. All other chemicals were obtained from commercial sources at reagent grade while styrene was purified by distillation under reduced pressure, and 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) was purified by recrystallization from acetone. All other chemicals were used without further purification. The anti-human TF monoclonal antibody was obtained from Abcam and Lifespan Biosciences. Immunohistochemical staining for clinical human colorectal section samples and Western blotting analysis were performed using the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex method available in a commercial kit (Mouse IgG Vectastain ABC Elite kit, Vector Laboratories). All experimental protocols used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University Medical Center. At the onset, male golden mice, which ranged in body weight from 20–25 g, fasted for 18 hours but had free access to water prior to the following experiments.

Cell culture

Human colorectal cancer cell lines, including SW480, HCT116, Caco-2 and HCT15 were maintained in Leibovitz’s L15 with L-glutamine (SW480), Mccoy’s 5A (HCT116), DMEM with L-glutamine (Caco-2) and RPMI with L-glutamine (HCT15). Each medium was supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%, v/v) and penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/mL). All cell lines were maintained in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

Synthesis and characterization of the nanobeacon

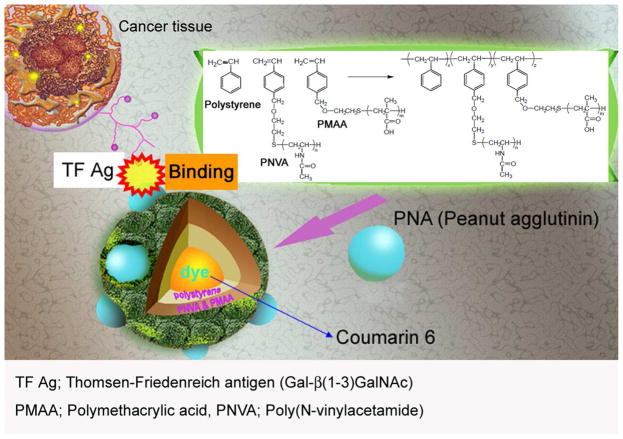

The synthesis of the nanobeacon was started with the surface coating polymer comprised of poly(N-vinylacetamide) (PNVA) and poly(tert-butyl methacrylate) (PBMA) was synthesized via free radical polymerization of NVA and BMA monomers, respectively, in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol as a chain transfer agent and in the presence of AIBN as an initiator. The resulting hydroxyl-terminated PNVA and PBMA were allowed to react with p-chloromethyl styrene in the presence of tetrabutylphosphonium bromide, sodium hydride and N,N-Dimethylformamide as a solvent. Vinylbenzyl group-terminated PBMA was hydrolyzed in an acidic solution with hydroquinone as a polymerization inhibitor to obtain vinylbenzyl group-terminated PMAA. Fabrication of the fluorescent dye-encapsulated nanobeacon was achieved by dissolving vinylbenzyl-terminated PNVA (0.5 g, molecular weight 7,300 g/mol)), vinylbenzyl-terminated PMAA (0.5 g, molecular weight 12,000 g/mol), which was obtained by hydrolysis of vinylbenzyl-terminated PMAA, and styrene (1.0 g) in 15 mL of ethanol:water (2:1 ratio) containing AIBN (approximately 1 mol% of the total monomers) and Coumarin 6 (0.1% of the total monomers). Dispersion copolymerization was accomplished successively at 60°C for 18 hours under mild stirring. After centrifugation of the resulting nanosphere dispersion, the supernatant that contained the unreacted substances and unencapsulated Coumarin 6 was removed, and the precipitated nanospheres were dispersed into the ethanol/water mixture. Fifty milligrams of fluorescent nanospheres were dispersed in 10 mL of 0.05 M KH2PO4 aqueous solution dissolving 20 mg of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide. After incubation of the dispersion at 4°C for 30 minutes, the nanosphere with activated carboxylic groups in the PMAA chains were collected by centrifugation at 18,400 g for 15 minutes. The nanospheres were dispersed in 10 mL of PBS followed by adding PNA. The reaction mixture was stirred at 4°C for 24 hours. Then, the nanosphere dispersion was centrifuged again to separate the precipitated product from the unreacted materials in the supernatant. This process was repeated three times, and the precipitated PNA-immobilized fluorescent nanospheres were finally dispersed in purified water at a concentration of 20 mg/mL (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overall design of the nanobeacon for imaging TF-associated colorectal cancer. The probe is comprised of a fluorescent dye, Coumarine 6 encapsulated in the center core by a polystyrene copolymer. The complex was then grafted with PMAA and PNVA polymers on the surface. Here, the PMAA was used as a handle to achieve the covalent binding of PNA molecules, which are the recognition molecules for the TF antigen. PNVA was used to help reduce or obviate nanobeacon interacting with the mucous tissue in the GI tract. The average size of the nanobeacon is approximately 350 nm.

Each step of probe assembly was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (S-3500N, Hitachi Co. Ltd) and transmission electron microscopy (Philips CM12, Hillsboro, OR). And the hydrodynamic diameter of the nanobeacon was determined using dynamic light scattering (ELSZ-2, Otsuka Electronics, Osaka, Japan). The content of the coating polymer was assessed using gel permeation chromatography. We also assessed the polymer chemical composition on the surface of the nanobeacon using X-ray photoelectron spectrometry (Kratos Axis Ultra, Shimadzu Co., Japan). The content of fluorescence dye was assessed using IV-Vis (U-3300, Hitachi, Japan).

Biodistribution study

Mice (n=16) were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine solution and maintained in that state with a mixture of 1.0% isoflurane and 2.0% oxygen during the surgery. The abdominal cavity of the mouse was opened and an intestinal loop of about 5 cm in length was made at the proximal jejunum or the large intestine by string ligation of the proximal side of each intestine. Then, 0.1 mL of a test solution containing either nanosphere (20 mg/mL) or Coumarin 6 (10 μg/mL) was introduced into the intestinal loops from the distal side using a syringe, and the end of loop was ligated. At a predetermined period of 2 hours, mice were sacrificed and blood samples (approximately 0.2 mL), the intestinal loops, livers and kidneys were collected, weighed and homogenized in PBS for HPLC analysis.

Oral administration study

At a predetermined time of 2 hours after mice were orally administered the solution containing the nanosphere (20 mg/mL, 0.1 mL), they were sacrificed. Approximately 0.2 mL blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta using a heparinized syringe with a needle, and other tissues, such as stomach, small intestines, ceca, large intestines, liver, and kidneys were dissected and weighed. Each sample was homogenized in PBS (g tissue/3 mL PBS) using a homogenizer (Tissuemizer Homogenizer, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Blood samples were diluted in PBS (mL blood/3 mL PBS).

Ex vivo imaging TF expression in the colon of MUC1 transgenic mice

MUC1 transgenic and wild-type mice (male, n = 8 each) were anesthetized with isoflurane. After opening the abdomen, the entire intestine was eviscerated carefully from the bottom of the stomach to the colon and rectum. Excess adipose tissue from around the intestine was removed. The whole intestine was separated into four parts including the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon/rectum. Each part was washed once with 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) after which each was cut open. Next, each part of the whole intestine was treated with 0.2 mL of the nanobeacon (2 mg/mL). Then, the intestine portions were washed twice with 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) to remove the excess probe prior to optical imaging (IVIS 200, Caliper Life Sciences). The resultant imaging data was analyzed using Living Image 4.0 software, and the fluorescence intensity of each part of the intestine was analyzed in terms of the photon count noted in the drawn region of interest.

Patient specimens, probe staining and immunohistochemistry

Colorectal cancer tissue samples (n=7) and normal colorectal tissue samples (n=7), from different individuals were collected from the Vanderbilt Cooperative Human Tissue Network and the National Disease Research Interchange network (Philadelphia, USA), respectively. All parts of the study were approved by Vanderbilt’s Institutional Review Board.

Prior to treatment of the human tissue with the nanobeacon probe or immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, frozen sections of sample tissues were air-dried and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. Then, the slides were subjected to antigen retrieval by exposing them to a warm solution of citric acid buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0). After antigen retrieval, the sample slides were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) before exposure to 0.1 mL of the nanobeacon (20 mg/mL) for fluorescence microscopy (Nuance FX, CRI). A fluorescent filter for FITC was used during fluorescence observation of the nanobeacon, Coumarin 6 and the tissue alone (for autofluorescence). Images observed under fluorescence/white visible light were captured with a CCD camera operated via Nuance software (Version. 2, CRI).

For IHC, the antigen-retrieved tissue was stained using the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex method available in a commercial kit (Mouse IgG Vectastain ABC Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories, USA). The endogenous biotin blocking step was adopted using a commercial kit (Avidin/Biotin Blocking kit, Vector Laboratories, USA). The anti-human TF monoclonal antigen was used for detection. Finally, IHC staining using ABC method was conducted following the manufacturer’s protocol included with the kit.

Quantitative analysis of human tissues

Quantitative analysis of TF antigen expression was conducted using MATLAB software (MathWorks, Inc., USA). The analysis protocol was programmed based on the TF expression of each tissue obtained via imaging analysis that focused on the positive (brown colored) area of IHC staining. The data represented the ratio of the positive area in normal and cancerous tissues.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from human colorectal tissues using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, Nanodrop technologies). Reverse transcription reaction was performed using a high-capacity cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of human 1,3 -galactosyltransferase using the forward primer: 5′-CATAGGAGCGGGAATGAAAA-3′ and the reverse primer: 5′-AGCTCCAAAAAGCACAAGGA-3′. The TF mRNA level was quantified by qRT-PCR using the SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) and normalized to β-actin. Changes in the expression were calculated using the ΔΔCt method 21.

Western blot analysis

The NuPAGE gel electrophoresis system with the XCell II Blot Module (Invitrogen) were used for the Western blot analysis. Whole protein from snap frozen clinical colorectal sample tissues was extracted using CelLyticMT (SIGMA) with an added protease inhibitor (protease inhibitor cocktail, SIGMA). The whole protein extracts were harvested in SDS-sample buffer (NuPAGE LDS Sample buffer 4x, Invitrogen), and total protein concentration was measured by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific). Protein samples (100 μg) were applied on 4–12 % gradient gel (NuPAGE Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE gradient gel, Invitrogen) and electrophoresed. Afterward, the gel was transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was probed with the anti-human TF antibody and anti-human beta-actin. The beta-actin was detected as a loading control.

TF antigen removal assay

Frozen human colorectal sample section tissues were fixed (4%PFA) and subjected to antigen retrieval. O-glycanase (Endo-α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase, EC 3.2.1.97, SIGMA) in 50 mM sodium-phosphate (pH 5.0) containing 100 μg/mL BSA was applied to the sample sections (12 mU/section) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Slides were covered with parafilm to prevent evaporation during incubation. After incubation, the slides were washed with DPBS twice and used for nanobeacon treatment and IHC staining. Only buffer solution was applied on the tissues as control.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

During the TF antibody treatment, cells were stained with a fluorescently conjugated anti-mouse monoclonal antibody (Alexa fluor 647, Invitrogen) after treatment with the TF antibody using conventional method. For the nanobeacon treatment, cells were treated exclusively with nanobeacon (0.5 mg/mL). Labeled cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (5-laser-BD LSRII cytometer, Becton–Dickinson). Fluorescence histograms and ratio of positive cells data were created and analyzed with CellQuest software (Becton–Dickinson). Specificity of the nanobeacon was determined by comparing the parameters of the nanobeacon treated cells and fluorescent conjugated antibody labeled cells.

Cell imaging

Cells were trypsinized and harvested. After washing each cell line with DPBS, cells were incubated for 2 days on chamber slides (Nunc, USA) and treated with an appropriate medium. After incubation, cells were washed gently DPBS twice after which the nanobeacon (4 mg/mL) solution was applied. Cells were incubated for 20 minutes in the incubator (25°C, 2% CO2). After incubation, cells were washed twice with DPBS and observed via fluorescent microscopy.

Statistical analysis

All values were measured by independent experiments conducted in triplicate and represented as the mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was analyzed using Student’s t-test conducted with StatView for Windows Ver. 4.5 (Abacus Software, USA), and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Physicochemical properties and in vitro assessment of nanobeacon specificity for human colorectal cancer cells

The design uses the hydrophobic interaction approach to trap the fluorescent dye within the nanoparticle core comprised of the hydrophobic polystyrene architecture. The nanobeacon particles are uniform in size and shape (Figs. 2A & 2B), and are dispersed thoroughly in PBS buffer. Most importantly, the nanobeacons are very stable. They can be stored in the dark at room temperature for an extended period of time without signs of bleaching. The average overall size of the spherical particles is approximately 350 nm as measured via transmission electron microscopy. To quantify the number of PNA molecules on the surface of the nanobeacon, we employed the adsorption-isotherm experiments. The data showed that there are 2.0–2.2 micrograms of PNA on each mg/mL of the nanobeacon (Supplementary Fig. S1). The amount of PNA was quantified by hydrolysis of the PNA from a known concentration of nanobeacons in the solution using hydrochloric acid. Under such conditions, PNA was also being hydrolyzed into amino acids. Amino acids were separated from the nanoparticles by active filtration. Then the concentration of amine was quantified by ninhydrin assay and compared to a calibrated PNA concentration curve. From this data, we approximated about 200–300 PNA molecules were fabricated on the surface of each nanobeacon. By changing the ratio of surface polymer PNVA and PMAA, we can fine-tune the desired size of the particles for a particular application. For instance, if we maintain equal amounts of PNVA and styrene and a 1.5 equivalent excess of PMAA, the resultant particles would have an approximate size of 350 nm, which is suitable to our intention of preventing bioabsorption of the particles in the intestine. More information about fine tuning the size of the nanobeacon could be found in the supporting information (Supplementary Table S1). With the current synthesis protocol, we can consistently synthesize a homogenous nanobeacon solution at a concentration of approximately 20 mg/mL. The concentration of the fluorescence dye was approximately 0.05 wt% within each particle.

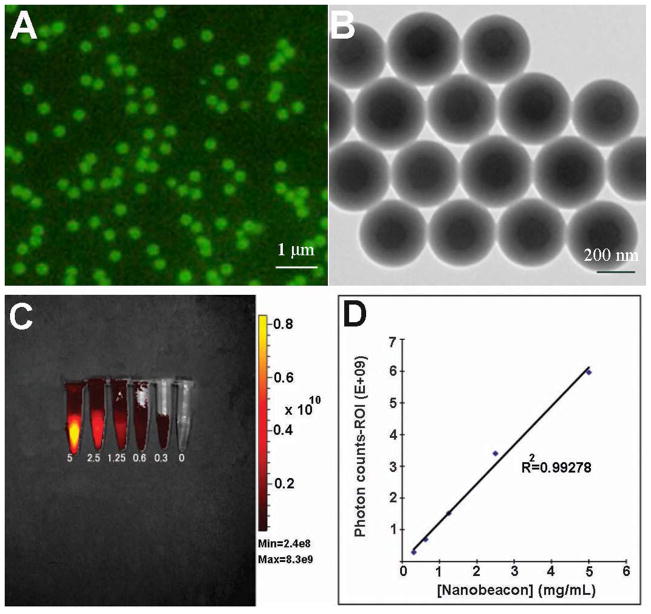

Figure 2.

Physical properties of the nanobeacon. A) A well-dispersed solution of the nanobeacon was observed under fluorescence microscopy. An equal distribution of Coumarin 6 within the center core of the particle results in a homogenous fluorescence signal being emitted from each particle. B) Homogeneity was confirmed via transmission electron microscopy. C) and D) Where phantom optical imaging of the nanobeacon is obtained, the data show a linear relationship between concentration and fluorescence.

To assess the fluorescence property of the nanobeacon, serial dilutions of the particles were prepared and imaged using an IVIS 200 equipped with a CCD camera (Caliper Life Sciences). The fluorescence intensity was analyzed relative to the photon counts noted in the drawn region of interest (ROI). The uniform distribution of Coumarin 6 dye in the polystyrene’s center core resulted in an even fluorescent signal across the phantom tube of a given concentration (Fig. 2C). Quantitative imaging obtained by drawing the ROI in the area of fluorescence showed that the fluorescence correlated linearly with the corresponding concentration (R2 = 0.993) (Fig. 2D).

In vitro analysis the specificity of the nanobeacon

To characterize the specificity of the nanobeacon, colorectal cancer cell lines known for TF expression were treated either with respective fluorescently-labeled antibodies or the nanobeacon and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis of probe binding. As shown in Fig. 3A, the data indicated that the probe detected TF expression on the cell’s surface, which resulted in a strong fluorescence signal at the rims of cells, albeit with different intensities that reflected the different levels of TF expression on each cell type. To ensure that what we observed was the fluorescence signal emitted by the probe rather than autofluorescence, untreated cells were also observed under the same microscopic conditions. In fact, the fluorescence from the untreated cells was minimal (data not shown).

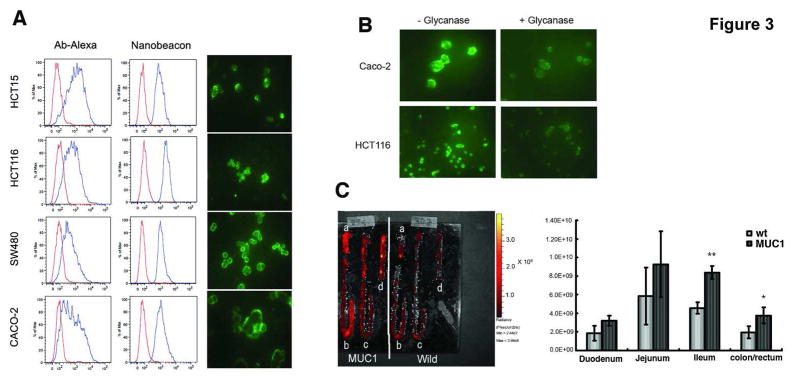

Figure 3.

(A) FACS analysis of TF-associated cell lines after the cells were exposed to either Alexa Fluor-conjugated mAb or the nanobeacon. The red histograms represent isotype control while the blue and shifted histograms indicate labeled cells. For fluorescence microscopy, live cells were incubated with the nanobeacon (4 mg/mL) in a chamber slide for 20 minutes before observation using the FITC channel. Exposure time was 400 ms at a magnification of 400 x each; (B) Specificity of the nanobeacon on human colorectal cancer cells. Treating cells with glycanase resulted in loss of fluorescence signal; (C) Representative fluorescence image captured with IVIS system. After being separated into a) duodenum, b) jejunum, c) ileum and d) colon/rectum and treated with the nanobeacon. ROI photon counts of each part of the intestines were measured by independent experiments in triplicate and represented by mean ± SD. Differences in photon counts were compared using Student’s t-test. *, p<0.05 and **, p<0.01.

We observed slightly different profiles between the antibody and nanobeacon stains, it is plausible that this phenomenon was due to the different antigenic specificities among the PNA and antibodies. For example, antibodies recognize TF through the Galβ1-3GalNAcα-chains as in PNA, but with some differences and lower capacity 22. FACS analysis from these data also suggested that the nanobeacon seems to be superior to antibodies in the detection of TF antigens as suggested in the past 8. Fluorescence imaging data for the nanobeacon-treated cells corroborate with the results obtained from the cell sorting data. The fluorescent signal emits from the rim of the cells manifests the distribution of TF primarily in the outer cellular membrane 23, 24. Furthermore, reports in the past also observed that PNA tends to stain the cell membrane rather than the cytoplasm 8. Additional experiments were performed to confirm that the fluorescence signal was produced via PNA-TF interaction, cells were treated with O-glycanase to remove TF before exposing them to the nanobeacon. In this case, the fluorescence signal diminished significantly using the same fluorescent microscopy parameter (Fig. 3B).

The nanobeacon can detect TF expression in the intestines of mice

We assessed the specificity of the nanobeacon by ex vivo optical imaging of the intestines freshly removed from the mice. It was apparent that the TF expression level was higher in MUC1 transgenic mice than in wild-type mice as noted by the higher fluorescence signal in all parts of the intestines (Fig. 3C). This was particularly evident in the ileum and colon/rectal sections which displayed a statically significant fluorescence signal approximately twofold beyond the signal detected in the wild-type mice (p<0.01 and 0.05, respectively).

Biodistribution study reveals that the nanobeacon is not absorbed by the intestine, and no systemic homing of the probe was noted in major organs

When the nanobeacon was injected intraluminally into the jejunum or large intestine of fasting mice, most of the material was recovered from the injection sites 2 hours afterward (Table 1). Among age-matched mice, there is a slightly amount of the probe was detected in the liver (0.42%), kidneys (0.063%) and serum (0.11%) when applied via the jejunum. While there is no registered homing of the nanobeacon in those major organs if it is distributed topically in the large intestine. However, when introducing only the Coumarin 6 into the jejunum or large intestine of the age-matched mice, it became evident that the rather smaller size dyed compared to the nanobeacons was absorbed significantly at both intestinal sites and distributed systemically to major organs. Specifically, a high concentration of free dye was detected in the liver and kidneys regardless of its point of entry. Total recovery of Coumarin 6 from the intra-jejunal deposition was 44.2 ± 8.4% versus 53.3 ± 7.5% of the dose administered via the large intestine.

Table 1.

Biodistribution of the nanobeacon versus free Coumarin 6 dye two hours post treatment in an orthotopic mouse model.

| Nanobeacona | Coumarin 6b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue weight (g) | Recovery (% of dose) | Tissue weight (g) | Recovery (% of dose) | |

| Intra-jenunal | ||||

| Jejunum | 0.342 ± 0.03 | 97.4 ± 8.5 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 44.2 ± 8.4 |

| Liver | 0.838 ± 0.05 | 0.42 ± 0.3 | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 3.2 ± 0.8 |

| Kidney | 0.251 ± 0.03 | 0.063 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.1 |

| Blood | -c | 0.11 ± 0.09 | -c | 2.03 ± 1.0 |

| Intra-colorectal | ||||

| Large Intestine | 0.241 ± 0.06 | 104 ± 4.3 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 53.3 ± 7.5 |

| Liver | 0.846 ± 0.19 | n.d.d | 1.07 ± 0.12 | 2.86 ± 1.5 |

| Kidney | 0.308 ± 0.04 | n.d.d | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.2 |

| Blood | -c | nd.d | -c | 2.12 ± 1.2 |

Injection dose 2mg/mouse

Injection dose 1.0 μg/mouse

Approximately 0.2mL of blood collected from the abdominal artery

Not detected

The nanobeacons can selectively detect TF expression on human colorectal specimens

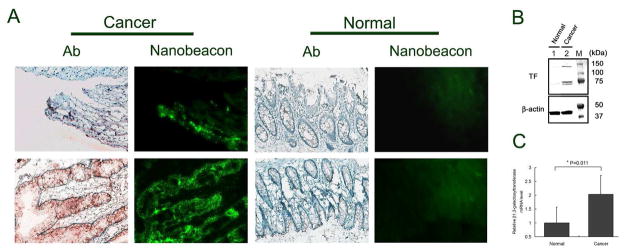

Normal human colorectal or cancer specimens (n = 7 each) were treated with the 0.1 mL of nanobeacon (20 mg/mL) for 30 minutes prior to fluorescence imaging. Additionally, consecutive slides from the same frozen tissue were subjected to immunohistochemical staining using TF-specific mAb for direct comparison with the TF distribution and intensity using the fluorescence data.

Representative images in Fig. 4A depict a strong fluorescence signal that corresponds to TF expression in the colorectal cancer tissues. These data were further corroborated with the positive signals obtained via IHC staining of their consecutive slides. It is apparent that TF antigen expression is significant in poorly differentiated carcinoma in the mucosa area. Furthermore, the highly damaged crypts also express high levels of the TF antigen. In contrast to cancer tissue, normal colonocytes did not express the TF antigen. As a result, no registered florescence signal was detected upon exposure to the nanobeacon.

Figure 4.

A) The expression of TF antigen on human colonic tissue from normal controls and cancer patients were detected using PNA molecules immobilized on the surface of the nanobeacon and confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Strong fluorescence from representative cancer sections (observation of 60 slides collected from 7 colorectal cancer patients) is correlated to a positive signal in IHC staining of the consecutive slides. Exposure time in fluorescence observation was 400 ms with magnification at 200x each. B) Representative results of Western blot (immunoblot) analysis of TF antigen expression in clinical human tissues with and without colorectal cancer. Beta-actin was shown as a loading control. TF antigen detected in human colorectal tissue samples which molecular weights are approximately 147, 84 and 77 kDa, respectively. C) A relative mRNA expression level of β1,3- galactosyltransferase in clinical human colorectal tissues with and without cancer (n=3) analyzed by qPCR. (* p=0.011).

To confirm and quantify TF expression in human tissue, Western blot analysis was performed on the same tissue block whose slides were used for fluorescence imaging. The data showed an increase in TF expression in human colorectal cancer (Fig. 4B). Since β1,3-galactosyltransferase has been involved in the synthesis of the TF epitope (Core 1) in colorectal cancer, to quantify TF antigens we performed an RT-PCR of β1,3-galactosyltransferase from human colorectal tissue. Quantitative PCR analysis noted a significant overexpression of mRNA in cancerous compared to normal tissues. Quantitatively, cancer tissues express mRNA for TF antigen synthesis at a rate approximately 2.5-fold higher than normal tissue (Fig. 4C, p=0.011). This quantification is consistent with another analysis we performed on histology slides using a MATLAB-based program developed in house. In this work, we developed an automatic threshold algorithm to separate the brown colored pixels which indicate positive for TF from the background. We then combined these data to create masked brown images (Supplementary Fig. S2). Analysis of the combined data showed that TF expression is from 3–10 fold higher in cancerous than in normal tissue.

DISCUSSION

Colonic epithelium is characterized by the expression of mucin glycoproteins which contain O-linked oligosaccharide synthesis on a polypeptide backbone 25. Changes in O-glycosylation are very common in colon cancer and often result in the expression of specific antigens such as the disaccharide Galβ1-3GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr, also known as the TF antigen 26. The TF antigen is well established as an oncodevelopmentally regulated, cancer-associated antigen that is occluded from normal cells and widely distributed among human tumors, especially in colorectal cancers 27, 28. In any of these cases, increased TF occurrence correlates with cancer progression and metastasis 29, 30. The significance of this work is that it represents the first attempt to image TF antigen-associated colorectal cancer using topically applied fluorescence nanoparticles in human colorectal cancer tissues. The data suggest that the nanobeacon was not absorbed by the large intestine; therefore, no systemic distribution occurred and no toxicity was present since no association occurred with the major organs. It is worth noting that in this probe, the Coumarin 6 was held tightly at the center core of the polystyrene particle. Not only did this prevent toxicity, but the fluorescent signal obtained from the probe was also concentration dependent. Thus, it is suitable for quantitative imaging. Beyond Coumarin 6, any hydrophobic fluorescence dye can be incorporated into the polymer core with the same efficiency. Our laboratory also developed similar nanobeacons using near-infrared dyes using the in-housed developed cyanine dyes (data not shown). However, our focus is on testing the Coumarin 6-associated nanobeacon since current commercial microendoscopic imaging systems are equipped with only blue excitation. The data shown in Table 1 indicate that Coumarin 6 may be a highly absorbable compound due to its high lipophilicity. This accounts for the fact that only 44.2% and 53.3% of the dose of Coumarin 6 was recovered from the intestinal loops after intra-jejunal and colorectal administration, respectively, of Coumarin 6 alone. This indicates that if Coumarin 6 was released from the nanosphere the dye could be absorbed and distributed to the liver, kidneys and blood. Additional work also showed that while the probe is well suited for topical application, it is inappropriate for oral administration. Studies using a live orthotopic mouse model show that the majority of the probe will concentrate in the stomach (Supplementary table S2).

To test the specificity of the nanobeacon on freshly isolated tissue, we treated and compared the fluorescence intensity depicted from the probe in the whole intestines of wild-type mice versus MUC1 transgenic mice. It has been demonstrated previously that TF is expressed by mucins encoded in humans by the MUC1 gene; thus TF should be evident in the epithelial tissue of MUC1 mice 31, 32. Other studies also demonstrated that TF epitope is carried by MUC1 on the apical surface of these cells 33. The data in Figure 3C indicated that the nanobeacon could recognize the TF antigen in the MUC1 mouse model. It appeared that the antigen expressed significantly in the colon/rectum compared to other intestinal sections of the transgenic mice and produced strong fluorescence (p<0.05).

One of the findings of this study highlights the notion that the nanobeacon can report TF expression in human colorectal cancer tissue (Figure 4). The optical imaging data on human tissue corroborate clearly with the IHC stains of the consecutive slides. The IHC and imaging data indicate a high concentration of TF were expressed on poorly differentiated cancer which fails to form crypts. To demonstrate that the fluorescence signal detected from the colon cancer tissue originated from the specific interaction between the TF antigen and the PNA-immobilized nanobeacon, TF was removed from the cells and the tissues using O-glycanase, before treating with the nanobeacon. The TF antigen removal on cells was quantified by FACS analysis, and we observed more than 50% of the antigen was removed using this method (Supplementatry Fig. S3). The data showed that the nanobeacon was nearly unable to adhere to the surface of cells or tissues once the TF antigen was removed. This suggests that PNA derivatized on the surface of the nanobeacon probe is in fact the specific molecular recognition moiety for the TF antigen (Fig. 5).

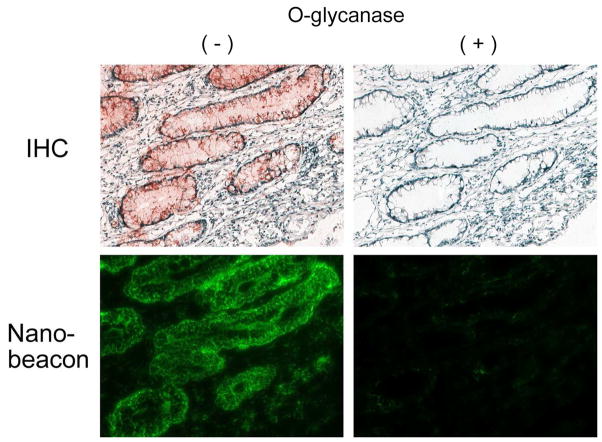

Figure 5.

Representative of the slides of nanobeacon treatment versus IHC staining of human colorectal cancer tissues to test the specificity using O-glycanase on consecutive slides. Treatment with O-glycanase (O-glycanase (+)) and consecutive untreated counterparts as a control (O-glycanase (−)). Exposure time for fluorescence observation was 400ms with magnification at 200x each.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a novel nanobeacon that offers the potential of imaging colorectal cancer via colonoscopy. The probe can detect dynamic changes of TF in human tissue, which suggests that in addition to being used for detection, it offers tremendous promise that imaging using this probe can be utilized to evaluate tumor response to treatment at the molecular level. Of note, the concentration of the probe used in this study was below the threshold for any possible concerns about the mitogenicity caused by PNA 13. We hope this evaluation will bring us a step closer to accelerating the translation of imaging and nanotechnology capabilities in order to impact favorably and significantly the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Combined with the CCD-based colonoscopy instruments presently available, the development of a new specific optical contrast agent for topical colon treatment makes this probe development ideal for clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Impact Statements.

We describe the development of a novel nanobeacon intended for colorectal cancer imaging. There is no systemic distribution accompanying the probe’s application to the intestine of a mouse. To help stimulate the translation of this research into clinical imaging, we also confirm the specificity of the nanobeacon directly on human colorectal cancer tissues. All together, we believe the results presented in this work offer critical input that will prove potentially beneficial in clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

The work described was supported by grants, R01CA160700 to WP and P50CA128323 to JCG from the National Cancer Institute. We would like to thank Michiyo Koyama for excellent assistance with manuscript preparation and Meiying Zhu for technical assistance during the course of work.

References

- 1.Daley D, Lewis S, Platzer P, MacMillen M, Willis J, Elston RC, Markowitz SD, Wiesner GL. Identification of susceptibility genes for cancer in a genome-wide scan: results from the colon neoplasia sibling study. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:723–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fahy B, Bold RJ. Epidemiology and molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol. 1998;7:115–23. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(99)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito H. Colorectal cancer screening using immunochemical faecal occult blood testing in Japan. J Med Screen. 2006;13:S6–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortega J, Vigil CE, Chodkiewicz C. Current progress in targeted therapy for colorectal cancer. Cancer Control. 2010;17:7–15. doi: 10.1177/107327481001700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheth RA, Mahmood U. Optical molecular imaging and its emerging role in colorectal cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G807–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00195.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly K, Alencar H, Funovics M, Mahmood U, Weissleder R. Detection of invasive colon cancer using a novel, targeted, library-derived fluorescent peptide. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6247–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsiung PL, Hardy J, Friedland S, Soetikno R, Du CB, Wu AP, Sahbaie P, Crawford JM, Lowe AW, Contag CH, Wang TD. Detection of colonic dysplasia in vivo using a targeted heptapeptide and confocal microendoscopy. Nat Med. 2008;14:454–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan M, Itzkowitz SH, Boland CR, Kim YD, Tomita JT, Palekar A, Bennington JL, Trump BF, Kim YS. Comparison of T-antigen expression in normal, premalignant, and malignant human colonic tissue using lectin and antibody immunohistochemistry. Cancer Res. 1986;46:4841–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg WM, Prince C, Kaklamanis L, Fox SB, Jackson DG, Simmons DL, Chapman RW, Trowell JM, Jewell DP, Bell JI. Increased expression of CD44v6 and CD44v3 in ulcerative colitis but not colonic Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 1995;345:1205–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91991-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh R, Campbell BJ, Yu LG, Fernig DG, Milton JD, Goodlad RA, FitzGerald AJ, Rhodes JM. Cell surface-expressed Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen in colon cancer is predominantly carried on high molecular weight splice variants of CD44. Glycobiology. 2001;11:587–92. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.7.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan M, Itkowitz SH, Boland CR, Kim YD, Tomita JT, Palekar A, Bennington JL, Trump BF, Kim YS. Comparison of T-Antigen Expression in Normal, Premalignant, and malignant Human Colonic Tissue Using Lectin and Antibody Immunohistochemistry. Cancer Res. 1986;46:4841–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bray J, MacLean GD, JDF, McPherson TA. Decreased Levels of Circulating Lytic Anti-T in The Serum of Patients With Metastatic Gastrointestinal Cancer: A Correlation with Disease Burden. Clin Exp Immunol. 1982;47:176–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryder SD, Smith JA, Rhodes JM. Peanut lectin: a mitogen for normal human colonic epithelium and human HT29 colorectal cancer cells. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1992;84:1410–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.18.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boland CR, Roberts JA. Quantitation of lectin binding sites in human colon mucins by use of peanut and wheat germ agglutinins. J Histochem Cytochem. 1988;36:1305–7. doi: 10.1177/36.10.3138307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boland CR, Montgomery CK, Kim YS. A cancer-associated mucin alteration in benign colonic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhodes JM, Black RR, Savage A. Glycoprotein abnormalities in colonic carcinomata, adenomata, and hyperplastic polyps shown by lectin peroxidase histochemistry. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:1331–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.12.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McEwan AJ, MacLean GD, Hooper HR, Sykes T, McQuarrie SA, Golberg L, Bodnar DM, Lloyd SL, Noujaim AA. MAb 170H. 82: an evaluation of a novel panadenocarcinoma monoclonal antibody labelled with 99Tcm and with 111In. Nucl Med Commun. 1992;13:11–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakuma S, Sudo R, Suzuki N, Kikuchi H, Akashi M, Ishida Y, Hayashi M. Behavior of mucoadhesive nanoparticles having hydrophilic polymeric chains in the intestine. J Control Release. 2002;81:281–90. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakuma S, Hayashi M, Akashi M. Design of nanoparticles composed of graft copolymers for oral peptide delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;47:21–37. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakuma S, Sudo R, Suzuki N, Kikuchi H, Akashi M, Hayashi M. Mucoadhesion of polystyrene nanoparticles having surface hydrophilic polymeric chains in the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Pharm. 1999;177:161–72. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(98)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steuden I, Duk M, Czerwinski M, Czeslaw R, Lisowska E. The Monoclonal Antibody, Anti-Asialoglycophorin from Human Erythrocytes, Specific for -D-Gal-I-3-c -D-GalNAc-Chains (Thomsen-Friedenreich Receptors) Glycoconjugate journal. 1985;2:303–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao Y, Karsten UR, Liebrich W, Haensch W, Springer GF, Schlag PM. Expression of Thomsen-Friedenreich-related antigens in primary and metastatic colorectal carcinomas. A reevaluation. Cancer. 1995;76:1700–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951115)76:10<1700::aid-cncr2820761005>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nemoto-Sasaki Y, Mitsuki M, Morimoto-Tomita M, Maeda A, Tsuiji M, Irimura T. Correlation between the sialylation of cell surface Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen and the metastatic potential of colon carcinoma cells in a mouse model. Glycoconjugate journal. 2001;18:895–906. doi: 10.1023/a:1022252509765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itzkowitz SH, Yuan M, Montgomery CK, Kjeldsen T, Takahashi HK, Bigbee WL, Kim YS. Expression of Tn, sialosyl-Tn, and T antigens in human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1989;49:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brockhausen I, Schutzbach J, Kuhns W. Glycoproteins and their relationship to human disease. Acta Anat (Basel) 1998;161:36–78. doi: 10.1159/000046450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Springer GF. T and Tn, General Carcinoma autoantigens. Science. 1984;224:1198–206. doi: 10.1126/science.6729450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Springer GF, Desai PR, Wise W, Carlstedt SC, Tegtmeyer H, Stein R, Scanlon EF. Pancarcinoma T and Tn epitopes: autoimmunogens and diagnostic markers that reveal incipient carcinomas and help establish prognosis. Immunol Ser. 1990;53:587–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moriyama H, Nakano H, Igawa M, Nihira H. T antigen expression in benign hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Urologia internationalis. 1987;42:120–3. doi: 10.1159/000281868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf MF, Ludwig A, Fritz P, Schumacher K. Increased expression of Thomsen-Friedenreich antigens during tumor progression in breast cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 1988;9:190–4. doi: 10.1159/000217561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y, Sette A, Sidney J, Gendler SJ, Franco A. Tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens: a possible avenue for cancer prevention. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:440–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Y, Gendler SJ, Franco A. Designer glycopeptides for cytotoxic T cell-based elimination of carcinomas. J Exp Med. 2004;199:707–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeschke U, Walzel H, Mylonas I, Papadopoulos P, Shabani N, Kuhn C, Schulze S, Friese K, Karsten U, Anz D, Kupka MS. The human endometrium expresses the glycoprotein mucin-1 and shows positive correlation for Thomsen-Friedenreich epitope expression and galectin-1 binding. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:871–81. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.952085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.