Abstract

Phosphatase and tensin-homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) is a tumor-suppressor protein that regulates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) signaling by binding to the plasma membrane and hydrolyzing the 3′ phosphate from phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3) to form phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2). Several loss-of-function mutations in PTEN that impair lipid phosphatase activity and membrane binding are oncogenic, leading to the development of a variety of cancers, but information about the membrane-associated state of PTEN remains sparse. We have modeled a membrane-associated state of the truncated PTEN structure bound to PI(3,4,5)P3 via multiscale molecular dynamics simulations. We show that the location of the membrane-binding surface agrees with experimental observations and is robust to changes in lipid composition. The level of membrane interaction is substantially reduced in the phosphatase domain for the triple mutant R161E/K163E/K164E, in line with experimental results. We observe clustering of anionic lipids around the C2 domain in preference to the phosphatase domain, suggesting that the C2 domain is involved in nonspecific interactions with negatively charged lipid headgroups. Finally, our simulations suggest that the oncogenicity of the R335L mutation may be due to a reduction in the interaction of the mutant PTEN with anionic lipids.

Introduction

Cell signaling involves a number of proteins that interact with cell membranes. Several such proteins bind to the inner (cytoplasmic) surface of the plasma membrane to carry out their function. To facilitate this, many of these proteins possess one or more distinct lipid binding domains. Several of these lipid-binding domains have been identified (1), and they typically exploit the presence of anionic lipids in the plasma membrane to target proteins to the surface via electrostatic interactions (2,3). While estimates vary, the concentration of anionic lipids (of various species) in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the cell membrane is thought to be between 10 and 20% depending on the cell type (4–7).

These anionic lipids play two roles in protein targeting:

First, the pool of negatively charged lipids allows for recruitment of positively charged lipid-binding domains through nonspecific interactions with this charged surface.

Second, some species of negatively charged lipid within this pool—for example, the phosphoinositides—can act as specific recognition sites for particular protein domains (8,9).

The plasma membrane and its constituent phosphoinositides form the basis of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) signaling pathway, which is crucial for cell proliferation and survival (10). PI3-K signaling primarily relies upon two lipid species, phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) and phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3), which are differentiated by the presence or absence of a phosphate group at the 3′ position of the inositol ring (9). Activation of PI3-K signaling is dependent upon biosynthesis of PI(3,4,5)P3 from PI(4,5)P2 by the PI3-K enzyme. The newly synthesized PI(3,4,5)P3 can then provide a membrane anchor to recruit other proteins to the surface, for example Akt (protein kinase B) that binds PI(3,4,5)P3 through its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. Akt is an essential downstream effector in PI3-K signaling (11) that regulates cell proliferation and survival by inhibiting apoptosis.

Membrane localization via PI(3,4,5)P3 binding is essential for Akt activation, and so any factors that enhance Akt binding to PI(3,4,5)P3 can result in pathological membrane localization and, by extension, uncontrolled activation of Akt. This in turn leads to overall dysregulation of PI3-K signaling and has been linked to the development of several cancers. Pathological membrane localization can be caused by a mutation in Akt itself (12), or alternatively it can occur as a consequence of elevated levels of PI(3,4,5)P3. Production of PI(3,4,5)P3 is normally regulated by the phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) tumor suppressor protein, which negatively regulates PI3-K signaling by converting PI(3,4,5)P3 back to PI(4,5)P2, thereby keeping the basal level of PI(3,4,5)P3 low (13,14) However, loss-of-function mutations in PTEN can lead to overproduction of PI(3,4,5)P3 and uncontrolled PI3-K activation. PTEN is one of the most frequently mutated proteins in human cancer (15). Consequently, there is a wealth of mutational data available, as summarized in the Human Gene Mutation Database (16).

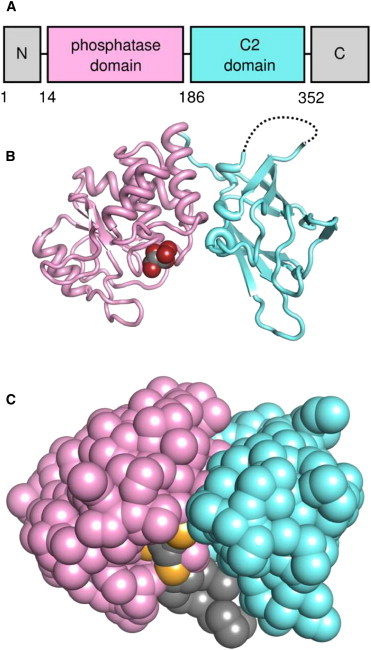

The full-length PTEN protein comprises ∼400 amino acid residues and is subdivided into four main regions: an N-terminal PI(4,5)P2 binding module; a phosphatase domain (PD); a C2 domain; and a C-terminal tail (Fig. 1). A crystal structure of truncated PTEN at 2.1 Å that includes the PD and the C2 domain has previously been determined (PDB:1D5R (17); see Fig. 1). However, although PTEN is a key component of PI3-K signaling, little is known about its mode of interaction with the plasma membrane.

Figure 1.

Structure of PTEN. (A) Domain structure of PTEN. (B) The crystal structure of PTEN, with the phosphatase domain (PD; residues 14–185) in pink and the C2 domain (residues 186–351) in cyan. The tartrate molecule bound in the phosphatase active site is shown as van der Waals spheres. The loop missing from the crystal structure between P281 and K313 is shown as a dotted line. (C) Coarse-grained (CG) representation of PTEN. The bound tartrate has been replaced with a CG representation of PI(3,4,5)P3, with the PI(3,4,5)P3 molecule positioned as described in the main text.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide us with a computational tool to probe the interaction between membrane proteins and the lipid bilayer in near-atomic detail (18). There have been a number of MD simulation studies concerning the interactions of C2 (19–21) and other (22–24) lipid-recognizing domains with membrane surfaces. In recent studies of the membrane interaction of the PH domain from the general receptor for phosphoinositides 1 (GRP1-PH) (25) and talin (26), the specific protein-lipid contacts revealed by MD simulations have been shown to be in good agreement with experimental results.

Here we use a multiscale approach, combining coarse-grained (CG) and atomistic MD simulations (27), to develop a model of the PTEN-membrane complex. This allows us to analyze the nature of PTEN-membrane interactions, revealing the importance of anionic phospholipids in interactions with the C2 domain of PTEN. A number of disease-related mutations of PTEN are shown to be likely to perturb interactions between this important protein and the plasma membrane surface.

Materials and Methods

Model building and system setup

Our studies of membrane-bound PTEN started from the crystal structure of PTEN (PDB:1D5R (17)), which comprises the two core domains of PTEN: a phosphatase domain (PD), and a C2 domain with a missing region between residues 281 and 313 of the C2 domain (Fig. 1). In the atomistic simulations, a harmonic restraint with spring constant 100 pN/Å was placed between the Cα atoms of P281 and K313 to maintain the separation observed in the crystal structure. This was judged to be a more conservative approach than trying to model a missing loop of ∼30 residues. In the CG simulations, an elastic network model is employed to maintain the secondary structure and so this additional restraint was not required.

The protein was crystallized in the presence of tartrate, and a tartrate molecule is bound at the active site. The authors of the article in which the structure was reported observed that the separation between the two carboxylate carbon atoms of the tartrate molecule is approximately the same as that between the phosphorus atoms at the 3′ and 4′ positions of the inositol ring of PI(3,4,5)P3. We were guided by these geometric considerations when constructing our initial coarse-grained (CG) model of PI(3,4,5)P3-bound PTEN, positioning the CG phosphate particles at the coordinates of the carboxylate carbons (Fig. 1).

All MD simulations were carried out using GROMACS version 4.0.5 (28).

CG MD simulations

We conducted CG self-assembly simulations of 0.5 μs duration and subsequent atomistic simulations of 50 ns duration. Each CG simulation was repeated twice using different initial particle velocities, for a total of three simulations per system. Each CG system comprised ∼300 lipids and ∼10,000 water particles with monovalent ions added as appropriate to compensate for any net charge, leaving the system neutral overall. CG simulations were performed using the MARTINI force field (29,30). In MARTINI, zwitterionic lipids such as POPC are approximated by a positively charged particle (choline), a negatively charged particle (phosphate), two polar particles (glycerol), and two acyl chains made up of four and five hydrophobic particles, respectively. Anionic lipids such as POPS are treated in a similar fashion except that the positively charged particle is replaced with a polar particle to represent the switch from choline to serine.

The lipid headgroup then carries an overall net negative charge. A cutoff of 12 Å for both the Lennard-Jones and the electrostatic interactions was used. Simulations were performed under periodic boundary conditions and temperature was kept constant at 323 K (as in our earlier CG simulations and in the MARTINI parameterization) by coupling the system to a heat bath using a Berendsen thermostat (31) with τT = 1 ps. Pressure was maintained at 1 atm using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat (32,33) and semiisotropic pressure coupling with τp = 1 ps and a compressibility of 5 × 10−6 bar−1. A timestep of Δt = 0.01 ps was used, writing atomic positions every 10 ps. The neighbor list was updated every 10 steps. The final frame of each CG simulation was converted to an atomistic representation of the system using a fragment-based approach (27).

Atomistic MD simulations

Atomistic simulations were performed with the GROMOS96 43a1 force field (34) using the simple point charge water model (35). A cutoff of 10 Å was used for the Lennard-Jones interactions and electrostatic interactions were treated using the particle-mesh Ewald (36) approach with a short-range real-space cutoff of 10 Å. Atomistic simulations were performed using the same parameters as for the CG simulations, except that T = 296 K (which is above the phase transition temperatures of both POPC and POPS; see, e.g., http://avantilipids.com), τT = 0.1 ps and compressibility was set to 4.6 × 10−5 bar−1. For the atomistic simulations, bond lengths and angles were constrained using the LINCS algorithm (37) and a timestep of Δt = 0.002 ps was used.

Continuum electrostatics calculations

Electrostatic potentials were computed on a cubic grid of dimensions 129 Å × 129 Å × 129 Å with a grid spacing of 1 Å using the Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver (38) at an anionic strength of 0.1 M and a temperature of 300 K.

Umbrella sampling and potential of mean force calculations

Umbrella sampling CG MD simulations were performed by displacing the PTEN protein from the surface of the bilayer by 1 Å intervals along the z axis perpendicular to the plane of the membrane. Umbrella sampling was performed by simulating each window for 0.5 μs using a restraining potential of 100 pN/Å fixed at the center of mass of PTEN. The last 0.1 μs of each window was used to calculate the potential of mean force (PMF). The PMF was computed using the g_wham tool, available as part of the GROMACS package.

Results and Discussion

Simulations and the bilayer interaction of PTEN

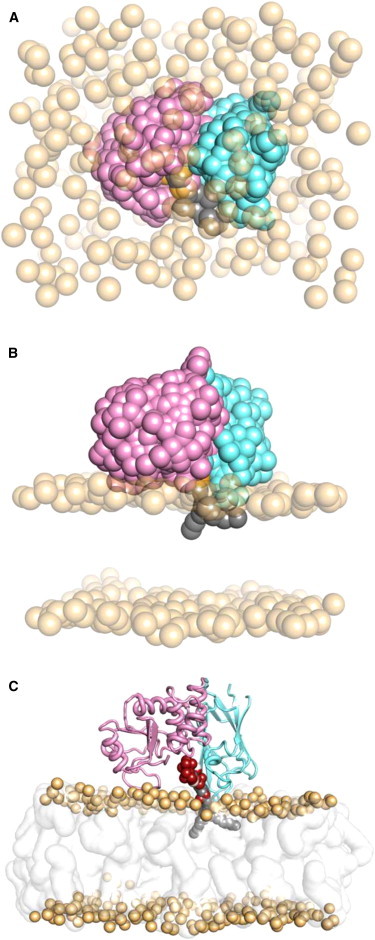

To determine the mode of interaction of PTEN with lipid bilayers, we used a serial combination of CG MD simulations and atomistic MD simulations. To start, CG MD simulations of 0.5 μs duration were used to self-assemble a lipid bilayer around the protein and identify the location of the membrane-binding interface. These were followed by shorter (50 ns) atomistic simulations to probe the detailed protein-lipid contacts in the PTEN-membrane complex (Fig. 2). Of course, in 50 ns of atomistic simulations large-scale changes in protein-lipid interactions are unlikely to occur, but such simulations enable, e.g., refinement of sidechain-headgroup contacts formed during the initial CG-MD simulations. Two different bilayer lipid compositions were explored: either a bilayer entirely composed of a zwitterionic lipid (phosphatidylcholine, PC; see Materials and Methods), or a two-component bilayer formed from a mixture of zwitterionic and anionic lipids (80% PC and 20% phosphatidylserine, PS). A set of simulations utilizing higher concentrations of anionic lipids (60% PC and 40% PS) was also performed (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material) as a simple model of localized clustering of anionic lipids in a cell membrane.

Figure 2.

Self-assembly and simulation of the PTEN-membrane complex, outlining the serial multiscale MD workflow. (A) Initial simulation setup. Lipids are randomly distributed throughout the simulation box. Lipid phosphate headgroups are shown as transparent orange spheres, while lipid tails, water, and ions are omitted for clarity. (B) Simulation snapshot after 0.5 μs CG simulation. Bilayer self-assembly and PTEN-membrane complex formation occurs within the first few tens of nanoseconds of simulation in all cases. (C) The final frame of the CG simulation shown in panel B is converted to an atomistic representation, which is then simulated for a further 50 ns.

In all cases, a lipid bilayer formed from the initially randomly placed lipid molecules within ∼50 ns of the CG simulation, with the PTEN molecule bound to the surface of the bilayer. In all 15 simulations of both the wild-type and various mutant PTEN proteins (see below and Table S1 in the Supporting Material), with different bilayer compositions the same overall position and orientation of PTEN relative to the bilayer was obtained, with the center of mass of the protein located ∼41 Å from the center of the bilayer along the bilayer normal (z) axis. This places the PTEN molecule such that it interacts with the lipid headgroups but does not largely penetrate the hydrophobic core of the bilayer. The PI(3,4,5)P3 molecule modeled at the active site of the PD domain is positioned such that its fatty acyl tails penetrate into the hydrophobic core of the bilayer (Fig. 2 C).

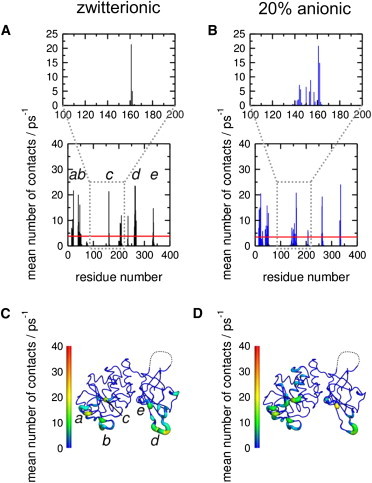

The membrane-binding model predicted by this multiscale simulation procedure is such that the major interactions between PTEN and the lipid bilayer correspond to those regions of the protein previously suggested by experiment to be most important for membrane binding, namely the cationic patch defined by residues R161, K163, and K164 (39), and the basic residues present in the third Ca2+ binding region (CBR3) of the C2 domain: K260, K263, K266, K267, and K269 (40) (Fig. 3). This further validates our simulation approach, lending some confidence that our model of the PTEN-membrane complex is a reasonable approximation of the cell membrane–bound state.

Figure 3.

Membrane binding of PTEN. Protein-lipid heavy atom contacts within 4 Å from the atomistic simulations for the wild-type PTEN protein and (A) a zwitterionic bilayer, and (B) a bilayer containing 20% anionic lipids. The region containing residues R161, K163, and K164 is expanded in each case. (C and D) Respective contacts mapped onto the PTEN structure, illustrating the location of the interaction surface with the lipid bilayer. The region missing from the crystal structure is shown as a dotted line, and is seen to be distant from the lipid-binding interface. Note that panels A and C are annotated to indicate regions (a–e) of the sequence that interact most strongly with the lipid bilayer. The main peaks occur in approximately the same residues for both the zwitterionic and the 20% anionic bilayer. Thus, the largest peaks are for (a) D22, (b) R41 (R47 for the 20% anionic bilayer), (c) R161, (d) K263, and (e) R335.

PTEN is able to bind to both purely zwitterionic and mixed zwitterionic/anionic lipid vesicles, with a higher binding affinity for the latter (39). Comparison of residue interactions with lipid headgroups for PTEN interactions with PC versus PC/PS bilayers reveals that, in each case, both the PD and C2 domains of PTEN form substantive bilayer interactions and, for example, in the presence of anionic lipids, the interactions between the cationic patch and the membrane are enhanced (Fig. 3).

Mapping the lipid contacts onto the PTEN structure reveals that the missing region in the crystal structure is far removed from the PI(3,4,5)P3 binding site and the proposed membrane-binding surface, and this region does not interact with bilayer lipids during any of the simulations (Fig. 3).

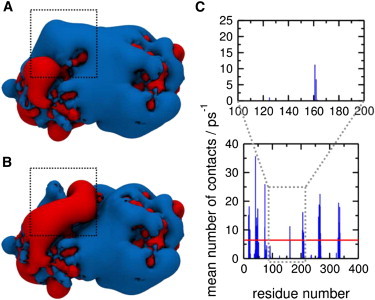

Mutation of a cationic surface patch reduces the membrane interaction of PTEN

Three basic side chains (R161, K163, and K164) of the PD form a cationic patch on the surface of PTEN. Previously Das et al. (39) established that mutation of these residues resulted in a decrease in membrane-binding affinity. However, the mutant retained phosphatase activity, suggesting that this region did not interact with the substrate PI(3,4,5)P3 directly. To further explore our binding model for PTEN, we simulated a triple mutant (R161E/K163E/K164E) in which we replaced this cationic patch by an anionic equivalent (Fig. 4). The protein-lipid contacts in this region between the charge reversal mutant PTEN and the bilayer are substantially reduced, especially for the anionic PS-containing lipid bilayer (Fig. 4). Similar behavior was observed when simulations were run using higher concentrations (40%) of anionic lipids, in which case the interaction between the mutant patch and the lipid bilayer was almost completely abrogated (see Fig. S1). In all cases, there are markedly fewer contacts between the residues at positions 161, 163, and 164 and the lipids in the bilayer upon mutation.

Figure 4.

Membrane binding of a mutant PTEN. The electrostatic potential around (A) the wild-type protein and (B) the R161E/K163E/K164E mutant protein are shown, calculated using the Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver (38). The location of the cationic patch formed by R161, K163, and K164 is indicated by the dotted line. (C) Protein-lipid heavy atom contacts within 4 Å from the atomistic simulations for the R161E/K163E/K164E mutant protein and a bilayer containing 20% anionic lipids. The region containing E161, E163, and E164 is highlighted to facilitate comparison with Fig. 3. Electrostatic potential isocontours are shown at contour values of −1 kT/e (red) to +1 kT/e (blue).

The close correspondence between experiment and simulation in this case suggests that our multiscale model may be used predictively to examine the effects of mutations on PTEN-membrane interactions, at least in a qualitative fashion.

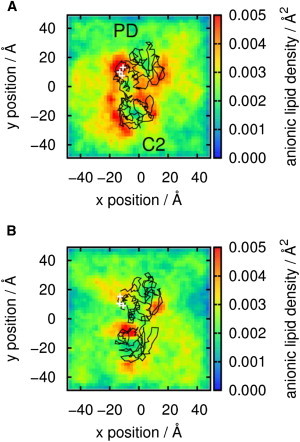

Anionic lipids interact with both of the PTEN domains

It is of interest to see how PTEN binding may perturb the bilayer lipid composition local to the protein, particularly in the context of, for example, studies of lipid nanoclustering adjacent to other classes of membrane proteins (41). Anionic lipid distributions around PTEN may be visualized via surface density maps (Fig. 5) and quantified by computation of radial distribution functions of the anionic lipids in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the lipid bilayer around the bound protein (see Fig. S2). It is clear from either analysis that anionic lipids cluster around both the PD and C2 domains of PTEN. This behavior is also observed in the simulations of the R161E/K163E/K164E mutant protein, although the extent of the PD-associated cluster is reduced. This also helps to explain the experimental observation that the membrane-binding affinity of the R161/K163/K164 mutant is much lower than that of the wild-type despite the fact that it remains catalytically competent and able to bind to PI(3,4,5)P3. It has been suggested that the C2 domain of PTEN is responsible for positioning the PD in an optimal orientation for binding to PI(3,4,5)P3 (42), and that it enhances the interaction of the PD with the membrane (39) possibly by binding to anionic lipids (43,44). This would correlate with the strong clustering of anionic lipids around the C2 domain, in both the wild-type and mutant protein simulations.

Figure 5.

Anionic lipid association with membrane bound PTEN. The results of analysis of the frequency of occurrence of anionic (PS) lipid headgroups in the bilayer (xy) plane adjacent to PTEN based on simulations of (A) the wild-type and (B) the R161E/K163E/K164E mutant proteins. The analysis is derived from the CG MD simulations in the presence of 20% PS in the bilayer. The color contours show the surface density of lipid headgroups. For 20% PS in an equilibrated bilayer with even distribution of lipids one would expect a surface density of ∼0.003 Å−2 assuming the area per lipid for POPS is 55 Å−2 (54). This would correspond to yellow/green contours in the density maps. The black trace shows the position of PTEN, used as a reference frame in this analysis, with the PD and C2 domains labeled.

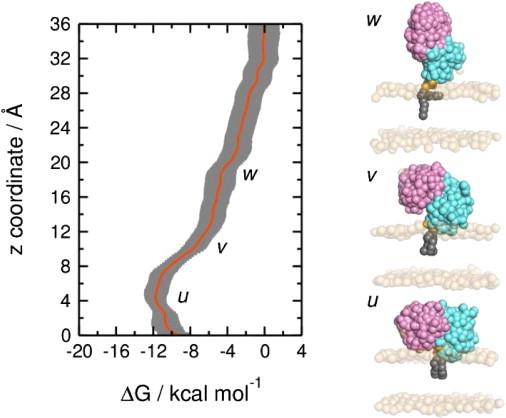

Potential of mean force of PTEN-membrane interactions

We calculated a PMF to provide a semiquantitative insight into the thermodynamics of the interaction between PTEN and a PI(3,4,5)P3-containing lipid bilayer. More specifically, the PMF provides a one-dimensional view of the CG free energy landscape along a reaction coordinate corresponding to center-of-mass separation between PI(3,4,5)P3 and PTEN as PTEN is translated along the bilayer normal.

The global minimum of the PMF (u in Fig. 6) corresponds to the native location as defined by the CG self-assembly simulations described above. This is reassuring, as it demonstrates that the self-assembly procedure correctly locates the minimum energy configuration of the PTEN-membrane system. Thus one may compare the system configuration corresponding to the minimum along the PMF with the equilibrium (i.e., self-assembly) simulations by calculating the values of the PTEN-POPC center-of-mass separations along z. Averaging over three repeats of the CG MD self-assembly simulations (over 100–500 ns; i.e., after the bilayer has formed) yields a PTEN-bilayer separation of 41 ± 1 Å. For the minimum along the free energy profile the PTEN-bilayer separation is 43 ± 2 Å).

Figure 6.

Potential of mean force (i.e., free energy profile) along a reaction coordinate defined by the distance between the PTEN and PI(3,4,5)P3 centers of mass along the bilayer normal (z). This PMF was evaluated using CG MD simulations and the bilayer containing 20% PS. The PMF was calculated over the intervals 400–500 ns for each window on z: this 100-ns interval was divided into ten segments each of 10-ns duration (400–410, 410–420 ns, etc.) and the PMF evaluated for each segment. The resultant ten PMF profiles were used to calculate a mean profile (red line) and standard deviations (gray bars), as shown. The windows at 4 Å, 10 Å, and 18 Å are labeled along the PMF by u, v, and w, respectively, and snapshots from the final frame of each of these windows are shown on the right of the figure.

We may also compare the position of the protein relative to the bilayer predicted by simulations with the results of recent neutron reflection studies of PTEN-membrane interactions (45). In the experimental studies, the lipid-bilayer headgroup to protein center-of-mass distance is ∼25 Å. In CG PMF simulations (configuration u in Fig. 6), the corresponding distance is ∼27 Å. Given the intrinsic resolution limits of CG, this is excellent agreement.

More detailed examination of the configurations of the system corresponding to shoulders in the PMF (v and w in Fig. 6) suggests that the C2 domain may interact more tightly with the membrane than does the PD. However, we are aware that the PMF provides a one-dimensional view of a more complex energy landscape for PTEN/bilayer interactions, and so this conclusion remains tentative. We have evaluated the convergence of our (one-dimensional) PMF (see Fig. S3). This suggests that convergence of a multidimensional PMF (with, for example, both protein separation and orientation as reaction coordinates) could require enhanced sampling techniques such as metadynamics (46).

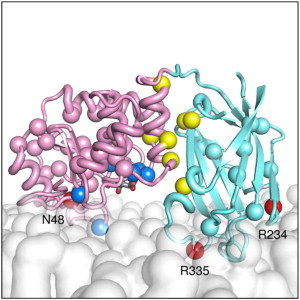

Membrane-interacting residues and disease-causing mutations

To determine whether our model of membrane-bound PTEN was able to shed any light on mutations implicated in human cancer, we compared the contacts observed in our simulations to the disease-causing mutations documented in the Human Gene Mutation Database (16). A summary of the PTEN mutations extracted from this database is provided as Table S2.

Many of the oncogenic and disease-causing mutations in PTEN occur either at the PD:C2 domain interface or are hydrolysis-defective mutations located at the phosphatase active site. However, several mutations occur at locations spatially distinct from these regions. We identified N48K (47), R234Q (48), and R335L (49) as potential membrane-interacting residues based on our simulations (Fig. 7). Of these three residues, R335 was observed to interact with the membrane to the greatest extent across all of the simulations. R335L, in common with several other germline mutations, has been associated with the inherited cancer syndrome Cowden’s disease (50), which results in higher risk of developing breast and thyroid cancer. The close proximity of this residue to the membrane in our simulations, coupled with the charged to nonpolar nature of the mutation, led us to speculate that the oncogenic nature of the R335L mutant may in part be due to a reduced binding affinity for anionic lipids.

Figure 7.

Locations of membrane-interacting clinically important mutations. Most oncogenic mutants occur at the PD:C2 domain interface or at the phosphatase active site. A selection of these is shown as yellow van der Waals spheres. However several mutants occur at sites spatially separated from these locations. In the PD (pink), N48K is shown in red and labeled. In the C2 domain (cyan), R234Q and R335L are also shown in red and labeled. The lipid bilayer is shown as a translucent white surface.

To examine this, we performed simulations of the R335L mutant protein with the zwitterionic and 20% anionic lipid systems, and again analyzed the contacts between the protein and the lipid bilayer. We observe a modest reduction in protein-lipid contacts for this region of the protein, with the protein-lipid interaction originating from the residue at position 335 in the mutant R335L reduced to just over one third of that detected in the wild-type in both cases. This provides some support for our hypothesis that a reduction in the interaction between the mutant protein and the membrane contributes to its oncogenicity, though clearly further studies (both simulation and experiment) to quantify changes in interactions and clinical effects of mutants are needed to confirm this.

Conclusions

Using a multiscale simulation approach developed and tested using a number of simpler membrane proteins, we have generated a detailed model of the interaction of PTEN with lipid bilayer membranes. This model correlates well with experimental data, in particular the correlation of the predicted lipid-binding surface with the properties of scanning mutations which perturb lipid binding (39), in the agreement between the predicted distance of the protein center of mass from the lipid-bilayer center of mass with that estimated from neutron reflection experiments (45), and with structural data (i.e., tartrate binding) on PI(3,4,5)P3 binding to the protein (17).

Our studies emphasize the importance of both the phosphatase and the C2 domain in providing membrane recognition platforms, in addition to the primary catalytic role of the phosphatase domain. Binding modes of membrane-localizing proteins that involve multiple recognition points have been observed in recent studies of PH domains (25) and of talin (26). The importance of both the PD and C2 domains in membrane recognition by PTEN agrees with and extends previous studies on nonspecific electrostatic recognition of bilayers by C2 domains from PTEN and other proteins (43).

Our simulations reveal aspects of the complex interrelationships of protein and lipid in the PTEN interactions, with PTEN binding leading to a degree of nanoclustering of anionic lipids. This is likely to be a general feature of binding of membrane recognizing proteins and enzymes, and as such merits further attention.

Our model adds to the interpretation of clinical mutational data in terms of the structure/function basis of the underlying mutation. In particular, we are able to show that a mutation leading to Cowden syndrome (R335L (50)) results in a significant perturbation of protein-bilayer interactions.

It is important to consider the likely limitations of this study. One is the focus on the core PTEN structure and its interactions with membranes, neglecting the N-terminal PI(4,5)P2 binding module and the C-terminal tail (neither of which is present within the x-ray structure). The N-terminal PI(4,5)P2 binding module is thought to have an influence in membrane binding (45) and it has been suggested (40) these two regions act in an autoinhibitory fashion when PTEN is present in the cytosol, by associating with the membrane binding surfaces of the PD and the C2 domains respectively through electrostatic interactions.

We also acknowledge the simplicity of our lipid bilayer composition, which is closer to in vitro model bilayers than those occurring naturally in vivo. In the future it should be possible to introduce more complex membrane compositions including most lipids identified in recent lipidomics studies (7) to further characterize the membrane-associated state of PTEN under more physiological conditions. Looking ahead, the model described here will form the basis of more complex and indeed more realistic computational studies, exploring in more detail the relationship between membrane binding, (anionic) lipid recruitment, and catalysis.

This will in turn enable improvements in models of PTEN/inhibitor interactions (51). It should also be possible to extend such models to other membrane proteins using a PTEN-like domain for bilayer recognition, for example auxilins (52) and the voltage-sensing phosphatase from Ciona intestinalis (53).

Acknowledgments

C.N.L. thanks the Medical Research Council for financial support. Research in the laboratory of M.S.P.S. is supported by grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, and The Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Lemmon M.A. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin S. The electrostatic properties of membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1989;18:113–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lumb C.N., Sansom M.S.P. Finding a needle in a haystack: the role of electrostatics in target lipid recognition by PH domains. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2012;8:e1002617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin S., Wang J., Murray D. PIP2 and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaughlin S., Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vance J.E., Steenbergen R. Metabolism and functions of phosphatidylserine. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005;44:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampaio J.L., Gerl M.J., Shevchenko A. Membrane lipidome of an epithelial cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:1903–1907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019267108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kutateladze T.G. Translation of the phosphoinositide code by PI effectors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:507–513. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunney T.D., Katan M. Phosphoinositide signaling in cancer: beyond PI3K and PTEN. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:342–352. doi: 10.1038/nrc2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantley L.C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpten J.D., Faber A.L., Thomas J.E. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448:439–444. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantley L.C., Neel B.G. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song M.S., Salmena L., Pandolfi P.P. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumor suppressor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali I.U., Schriml L.M., Dean M. Mutational spectra of PTEN/MMAC1 gene: a tumor suppressor with lipid phosphatase activity. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1922–1932. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenson P.D., Mort M., Cooper D.N. The Human Gene Mutation Database: 2008 update. Genome Med. 2009;1:13. doi: 10.1186/gm13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J.O., Yang H., Pavletich N.P. Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association. Cell. 1999;99:323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stansfeld P.J., Sansom M.S.P. Molecular simulation approaches to membrane proteins. Structure. 2011;19:1562–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mollica L., Fraternali F., Musco G. Interactions of the C2 domain of human factor V with a model membrane. Proteins. 2006;64:363–375. doi: 10.1002/prot.20986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaud S., Tobias D.J., White S.H. Self-induced docking site of a deeply embedded peripheral membrane protein. Biophys. J. 2007;92:517–524. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manna D., Bhardwaj N., Cho W. Differential roles of phosphatidylserine, PtdIns(4,5)P2, and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in plasma membrane targeting of C2 domains. Molecular dynamics simulation, membrane binding, and cell translocation studies of the PKCα C2 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26047–26058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Psachoulia E., Sansom M.S.P. Interactions of the pleckstrin homology domain with phosphatidylinositol phosphate and membranes: characterization via molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4211–4220. doi: 10.1021/bi702319k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psachoulia E., Sansom M.S.P. PX- and FYVE-mediated interactions with membranes: simulation studies. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5090–5095. doi: 10.1021/bi900435m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arcario M.J., Ohkubo Y.Z., Tajkhorshid E. Capturing spontaneous partitioning of peripheral proteins using a biphasic membrane-mimetic model. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:7029–7037. doi: 10.1021/jp109631y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lumb C.N., He J., Sansom M.S.P. Biophysical and computational studies of membrane penetration by the GRP1 pleckstrin homology domain. Structure. 2011;19:1338–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalli A.C., Wegener K.L., Sansom M.S.P. The structure of the talin/integrin complex at a lipid bilayer: an NMR and MD simulation study. Structure. 2010;18:1280–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stansfeld P.J., Sansom M.S.P. From coarse-grained to atomistic: a serial multi-scale approach to membrane protein simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:1157–1166. doi: 10.1021/ct100569y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marrink S.J., Risselada H.J., de Vries A.H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monticelli L., Kandasamy S.K., Marrink S.J. The MARTINI coarse grained force field: extension to proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:819–834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parrinello M., Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single-crystals—a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nose S., Klein M.L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics for molecular systems. Mol. Phys. 1983;50:1055–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Gunsteren W.F., Kruger P., Tironi I.G. BIOMOS/Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH; Zurich: 1996. Biomolecular Simulation: The GROMOS96 Manual and User Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermans J., Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M. A consistent empirical potential for water-protein interactions. Biopolymers. 1984;23:1513–1518. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald—an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess B., Bekker H., Fraaije J.G.E.M. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baker N.A., Sept D., McCammon J.A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das S., Dixon J.E., Cho W.W. Membrane-binding and activation mechanism of PTEN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7491–7496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahdar M., Inoue T., Devreotes P.N. A phosphorylation-dependent intramolecular interaction regulates the membrane association and activity of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:480–485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811212106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Bogaart G., Meyenberg K., Jahn R. Membrane protein sequestering by ionic protein-lipid interactions. Nature. 2011;479:552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georgescu M.M., Kirsch K.H., Hanafusa H. Stabilization and productive positioning roles of the C2 domain of PTEN tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7033–7038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray D., Honig B. Electrostatic control of the membrane targeting of C2 domains. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulgrew-Nesbitt A., Diraviyam K., Murray D. The role of electrostatics in protein-membrane interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1761:812–826. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shenoy S., Shekhar P., Lösche M. Membrane association of the PTEN tumor suppressor: molecular details of the protein-membrane complex from SPR binding studies and neutron reflection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leone V., Marinelli F., Parrinello M. Targeting biomolecular flexibility with metadynamics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vega A., Torres J., Pulido R. A novel loss-of-function mutation (N48K) in the PTEN gene in a Spanish patient with Cowden disease. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1356–1359. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2003.12638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staal F.J.T., van der Luijt R.B., Staal G.E. A novel germline mutation of PTEN associated with brain tumors of multiple lineages. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;86:1586–1591. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawada T., Hamano N., Mabuchi H. Mutation analysis of the PTEN / MMAC1 gene in Japanese patients with Cowden disease. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2000;91:700–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liaw D., Marsh D.J., Parsons R. Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997;16:64–67. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Q., Wei Y., Krilov G. Understanding the stereospecific interactions of 3-deoxyphosphatidylinositol derivatives with the PTEN phosphatase domain. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2010;29:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guan R., Han D., Kirchhausen T. Structure of the PTEN-like region of auxilin, a detector of clathrin-coated vesicle budding. Structure. 2010;18:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuda M., Takeshita K., Nakagawa A. Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-like region of Ciona intestinalis voltage-sensing phosphatase provides insight into substrate specificity and redox regulation of the phosphoinositide phosphatase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:23368–23377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukhopadhyay P., Monticelli L., Tieleman D.P. Molecular dynamics simulation of a palmitoyl-oleoyl phosphatidylserine bilayer with Na+ counterions and NaCl. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1601–1609. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74227-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.