Abstract

Synaptotagmin is the major calcium sensor for fast synaptic transmission that requires the synchronous fusion of synaptic vesicles. Synaptotagmin contains two calcium-binding domains: C2A and C2B. Mutation of a positively charged residue (R233Q in rat) showed that Ca2+-dependent interactions between the C2A domain and membranes play a role in the electrostatic switch that initiates fusion. Surprisingly, aspartate-to-asparagine mutations in C2A that inhibit Ca2+ binding support efficient synaptic transmission, suggesting that Ca2+ binding by C2A is not required for triggering synchronous fusion. Based on a structural analysis, we generated a novel mutation of a single Ca2+-binding residue in C2A (D229E in Drosophila) that inhibited Ca2+ binding but maintained the negative charge of the pocket. This C2A aspartate-to-glutamate mutation resulted in ∼80% decrease in synchronous transmitter release and a decrease in the apparent Ca2+ affinity of release. Previous aspartate-to-asparagine mutations in C2A partially mimicked Ca2+ binding by decreasing the negative charge of the pocket. We now show that the major function of Ca2+ binding to C2A is to neutralize the negative charge of the pocket, thereby unleashing the fusion-stimulating activity of synaptotagmin. Our results demonstrate that Ca2+ binding by C2A is a critical component of the electrostatic switch that triggers synchronous fusion. Thus, Ca2+ binding by C2B is necessary and sufficient to regulate the precise timing required for coupling vesicle fusion to Ca2+ influx, but Ca2+ binding by both C2 domains is required to flip the electrostatic switch that triggers efficient synchronous synaptic transmission.

Introduction

Synaptic transmission occurs when Ca2+ entry into an active nerve terminal triggers the fast, synchronous fusion of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic membrane. Shortly after the identification of its two C2 domains, synaptotagmin was postulated to be the Ca2+ sensor that triggers this synchronous fusion of vesicles (Brose et al., 1992). Initial studies suggested that the vesicle proximal C2 domain, C2A, mediated the Ca2+ binding that triggered synchronous vesicle fusion events (Elferink et al., 1993; Fernández-Chacón et al., 2001). However, mutations that inhibited Ca2+ binding by C2A supported efficient synaptic transmission at excitatory synapses (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2002; Stevens and Sullivan, 2003; Yoshihara et al., 2010). Mutations in the second C2 domain, C2B, that inhibited Ca2+ binding abolished evoked-transmitter release, demonstrating that Ca2+ binding by C2B is essential for synchronous, Ca2+-triggered transmitter release (Mackler et al., 2002). Thus, Ca2+ binding by the C2B domain has been thought to be both necessary and sufficient for triggering synchronous transmitter release. Yet mutations that disrupted Ca2+-dependent interactions by the C2A domain decrease synchronous release by 50% and decrease the apparent Ca2+ affinity of release (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2003; Paddock et al., 2008, 2011), suggesting that Ca2+ binding by C2A is required for efficient synchronous release. These results raised a now long-standing question: how can Ca2+-dependent interactions by C2A be functionally more significant than C2A Ca2+ binding itself?

When synaptotagmin binds calcium, it alters the electrostatic potential of the calcium-binding pocket (Ubach et al., 1998), enhancing interactions with other presynaptic molecules, such as negatively charged membranes and proteins of the SNARE complex (Brose et al., 1992; Chapman et al., 1995; Schiavo et al., 1997; Chapman and Davis, 1998; Bai et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002). This suggests that both C2 domains function as an electrostatic switch (Davletov et al., 1998; Ubach et al., 1998; Murray and Honig, 2002) such that the bound calcium ions shield, or effectively neutralize, the negative potential of the pocket. Such neutralization permits residues at the tip of both the C2A and C2B Ca2+-binding pockets, known to interact with negatively charged phospholipids (Chae et al., 1998; Fernández-Chacón et al., 2001; Bai et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2003), to interact with the presynaptic membrane. Thus, the previously tested aspartate-to-asparagine mutations (D→N) in C2A, which inhibited Ca2+ binding by removing this negative charge, may result in minimal disruptions of synchronous transmitter release, or even enhance release, because the mutations partially mimic Ca2+ binding (Stevens and Sullivan, 2003).

Here we directly test the importance of electrostatic repulsion by C2A in inhibiting fusion. We designed an aspartate-to-glutamate mutation (D→E) to test the function of Ca2+ binding independent of charge neutralization. This mutation inhibited Ca2+ binding but maintained the negative charge (and hence the repulsive force) of the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket. Our novel mutation, which cannot mimic the charge-neutralizing function of Ca2+ binding, results in a severe decrease in synchronous synaptic transmission, demonstrating that Ca2+ binding by C2A is required for the electrostatic switch.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis.

Drosophila synaptotagmin aspartate residue 229 was mutated to glutamate. Oligonucleotides (cttggtctcgaacttcttcttcttgtcgggcagcaagtacaccttgacatagggctccgaggtac and ctcggagccctatgtcaaggtgtacttgctgcccgacaagaagaagaagttcgagac) were used to create a mutant double-stranded DNA fragment with KpnI and StyI overhangs, which was ligated into a wild-type synaptotagmin cDNA construct in pBluescript II KS (Stratagene), sequenced, and subcloned into a pUAST vector to place the mutant syt gene under the control of the UAS promoter (Brand and Perrimon, 1993); then these were sent to Best Gene to transform Drosophila.

Fly lines.

Expression of the transgene was localized to the nervous system using elavGAL4 to drive pan neuronal expression of the UAS-syt transgenes (Brand and Perrimon, 1993; Yao and White, 1994). The sytnull mutation used was sytAD4 (DiAntonio et al., 1993). Standard genetic techniques were used to cross the transgenes into the sytnull background to express the transgene in the absence of endogenous synaptotagmin 1 (Loewen et al., 2006a). No gender selection was used, thus a mix of male and female larvae were used in all experiments. Experimental flies were yw; sytnullelavGAL4/sytnull; P[UAS sytA-D229E]/+ (P[sytA-D2E], transgenic mutant) and yw; sytnullelavGAL4/sytnull; P[UAS sytWT]/+ (P[sytWT], transgenic control).

Sequence alignments.

A ClustalW2 sequence alignment was performed on the C2A domain of the following Ca2+-binding synaptotagmin isoforms: syt 1 from Drosophila melanogaster (NP_523460.2), Apis mellifera (NP_001139207.1), Manduca sexta (AAK01129.1), Loligo pealei (BAA09866.1), Caenorhabditis elegans (NP_495394.3), Gallus gallus (NP_990502.1), Mus musculus (NP_033332.1), and Rattus norvegicus (NP_001028852.2); and Homo sapiens syt 1 (NP_001129277.1), syt 2 (NP_001129976.1), syt 3 (NP_001153801.1), syt 5 (NP_003171.2), syt 6 (NP_995320.1), syt 7 (NP_004191.2), syt 9 (NP_445776.1), and syt 10 (NP_945343.1).

Molecular modeling.

The D2E mutation in Figure 1C was modeled using the mutagenesis plugin in PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3; Schrödinger). Asp-178, from the high-resolution rat synaptotagmin 1 C2A x-ray structure (Protein Data Bank, PDB file; 1RSY), was changed to a glutamate. The rotamer with the fewest number of collisions was selected for the figure.

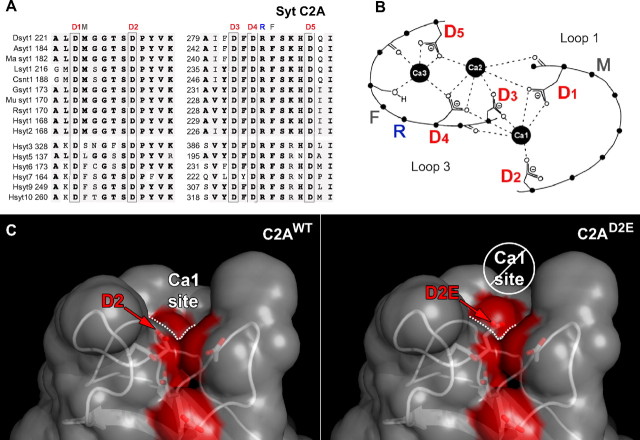

Figure 1.

The C2A domain of synaptotagmin 1 has five highly conserved aspartate residues that coordinate Ca2+. A, Alignment of C2A from Ca2+-binding synaptotagmin isoforms: synaptotagmin 1 from Drosophila (Dsyt1), bee (Asyt1), Manduca (Ma syt1), squid (Lsyt1), C. elegans (Csnt1), chicken (Gsyt1), mouse (Mu syt1), rat (Rsyt1), and human synaptotagmins (Hsyt) 1–3, 5–7, 9, and 10. Conserved residues are shown in gray and identical residues are in bold. The five conserved aspartate residues that coordinate the binding of Ca2+ ions are boxed and labeled as D1–D5. The conserved residues that mediate Ca2+-dependent interactions with negatively charged membranes are also indicated by M, R, and F. B, Schematic representation of loops 1 and 3 that form the Ca2+-binding pocket of the C2A domain. Adapted from Fernandez et al. (2001) to highlight the aspartates that coordinate Ca2+ (D1–D5) as well as the residues that interact with membranes (M, R, F). C, Molecular model of the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket illustrating the potential effect of the C2AD2E mutation. Coloring the oxygen atoms of the aspartate residues that coordinate Ca2+ by element revealed the negatively charged Ca2+-binding sites on the solvent accessible surface (red). In rat syt 1, asp178 (left, D2) participates in the coordination of the first Ca2+ (Ca1 site indicated by dotted line, see also B). Using the mutagenesis function in PyMol, we modeled the consequences of altering asp178 to a glutamate (right, D2E). We predicted that the bulging out of the solvent accessible surface (right, enlarged red bulge above white dotted line) could prevent Ca2+ binding to the Ca1 site.

Electrophysiology.

Excitatory junction potentials (EJPs) and miniature EJPs (mEJPs) were recorded using standard techniques (Reist et al., 1998; Paddock et al., 2011) from L3 muscle fiber 6 of abdominal segments 3 and 4 in HL3 saline containing 70 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 20 mm MgCl2, 10 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm Trehalose, 115 mm sucrose, 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, and 1.5 mm CaCl2, unless otherwise indicated. Dissections were performed in Ca2+-free HL3 saline. Fibers were impaled with a 10–40 mΩ recording electrode containing three parts 2 m potassium citrate to one part 3 m potassium chloride. The resting membrane potential of each fiber was maintained at −55 mV by passing a bias current. To evoke EJPs, segmental nerves were stimulated with a suction electrode filled with 1.5 mm Ca2+ HL3. The Ca2+ dependence curve was generated by averaging 10 EJPs recorded at 0.5 Hz from fibers bathed in HL3 containing Ca2+ concentrations ranging from 0.6 to 5.0 mm. Recordings in multiple Ca2+ concentrations were made from each muscle fiber. With the exception of 1.5 mm Ca2+, 10–13 fibers were recorded at each Ca2+ concentration in each genotype. At 1.5 mm Ca2+, 28–34 fibers were recorded, since most recording sessions included this concentration. All events were collected using an AxoClamp 2B (Molecular Devices) and digitized using a MacLab4s A/D converter (ADInstruments). The Ca2+-dependence data were fit with the Hill equation using Kaleidagraph software. The Ca2+ cooperativity coefficient was estimated from the slope of a double-log plot of EJP amplitude versus Ca2+ concentration. EJPs were recorded in Scope software and mEJPs were recorded in Chart Software (ADInstruments).

Immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry.

Western analysis was used to determine levels of transgene expression. The CNSs of individual third instar larvae were loaded one CNS per lane and blots were probed with an anti-synaptotagmin antibody [Dsyt-CL1 (Mackler et al., 2002)] and an anti-actin antibody (MAB 1501; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) using standard techniques (Loewen et al., 2001). Actin levels were used to normalize for equal protein loading; the synaptotagmin:actin signal ratio was determined for each lane, then normalized to the mean synaptotagmin:actin ratio of the P[sytWT] lanes on each blot to allow comparison of signal between multiple blots. Transgenic synaptotagmin was localized by immunolabeling third instar larvae with Dsyt-CL1 using standard techniques (Mackler and Reist, 2001). Neuromuscular junctions were visualized on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 upright digital imaging microscope.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were measured with an AVIV stop-flow circular dichroism spectropolarimeter at 192–260 nm using a 1 mm path-length cell. Samples containing 0.2 mg/ml of either wild-type or mutant C2A domains were assayed at 22°C. For corrections of baseline noise, the signal from a blank run of buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate) was subtracted from all the experimental spectra.

Isothermal titration calorimetry.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) data were generated using a GE Healthcare MicroCal iTC200, which, in principle, can detect dissociation constants from 10 mm to 1 nm. Wild-type and mutant C2A domains were dialyzed overnight in ITC buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 200 mm NaCl, and 10% glycerol). ITC buffer was further used to make calcium chloride stock and protein dilutions. Before each experiment, samples were degassed and cooled to experimental temperature. Heat of binding was measured from thirty 1.1 μl injections of calcium chloride into sample cells containing 1.6 mg/ml of proteins of interest at 15°C. Baseline corrections, for heat of dilution, were made by subtracting the signal of calcium chloride injections into buffer from all experimental traces. Data were analyzed using GE Healthcare MicroCal iTC200 Origin data software package.

Statistical analyses.

A Student's t test was used to determine whether any statistically significant differences existed between the two independent P[sytA-D2E] lines (line 3 and line 5). One-way ANOVA and Tukey range tests were used for statistical comparisons of P[sytWT] and the two P[sytA-D2E] lines.

Results

Sequence and structural analyses of C2A

C2 domains are a common functional motif found in multiple proteins. Although not all C2 domains are regulated by Ca2+, many C2 domains mediate a Ca2+-dependent translocation of the protein to membranes (Nalefski and Falke, 1996; Cho and Stahelin, 2006). In these proteins, Ca2+ is coordinated by five negatively charged residues located in loops 1 and 3 of the C2 domain β-sandwich structure (Fig. 1A,B, D1–D5) (Sutton et al., 1995; Nalefski and Falke, 1996; Ubach et al., 1998). Both aspartate and glutamate residues are used in the Ca2+-binding motifs of diverse C2 domains (Nalefski and Falke, 1996). To assess whether Ca2+ binding by C2A could be supported by either aspartate or glutamate residues, we compared the sequence of C2A domains of synaptotagmin isoforms that bind Ca2+. A sequence alignment revealed that glutamate is excluded from these key positions. In the C2A Ca2+-binding motifs of synaptotagmin 1 from many species, as well as of all of the human synaptotagmin isoforms that bind Ca2+, all five aspartate residues are 100% conserved (Fig. 1A), suggesting that glutamate residues in these positions would not provide full function.

Examination of the crystal structure of rat syt 1 C2A demonstrates that the deepest parts of this Ca2+-binding pocket are spatially quite restricted (Sutton et al., 1995). Glutamate, like aspartate, is negatively charged, but glutamate possesses a significantly larger molecular volume (91 Å3 for Asp vs 109 Å3 for Glu) (Creighton, 1994). Coupled with the exclusion of glutamate from C2A Ca2+-binding motifs, this observation suggests that a D→E mutation may impair Ca2+ binding. In the crystal structure of rat syt 1 C2A, both aspartate residue 178 (Fig. 1A,B, D2) and aspartate residue 230 (Fig. 1A,B, D3) are well ordered and located deep in the Ca2+-binding pocket (Sutton et al., 1995). To assess whether a D→E mutation in either of these locations may occlude the Ca2+-binding pocket, we modeled the C2AD2E and C2AD3E mutations in silico. Results suggest that the C2AD2E mutation might occlude Ca2+-binding site 1 (Fig. 1C, Ca1 site). If true, this novel mutation would directly assess the importance of the electrostatic repulsion provided by C2A in inhibiting vesicle fusion since it would inhibit Ca2+ binding without reducing the negative charge of the pocket (Fig. 1C, red).

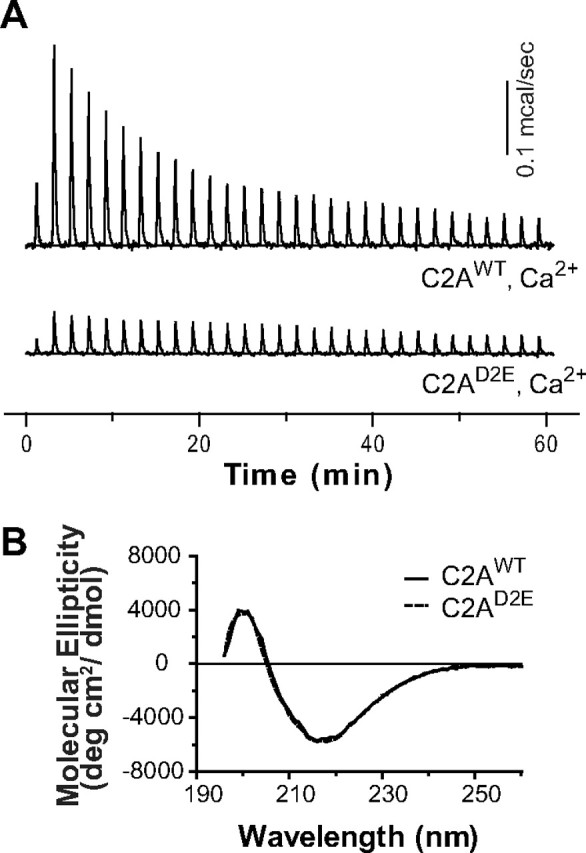

The sytA-D2E mutation inhibits Ca2+ binding to C2A

To directly measure Ca2+ binding to the C2A domain of Drosophila synaptotagmin 1, we used ITC. The titration data indicate three Ca2+-binding sites in Drosophila C2A (Fig. 2A, Table 1). The intrinsic Ca2+ affinities of the three sites measured by ITC (KD values were: 20.7 ± 3.9 μm, 83.4 ± 19 μm, and 766 ± 302 μm, respectively; Table 1) were in the same range, though the KDs were somewhat lower than those in previous reports on murine synaptotagmin using NMR (Shao et al., 1996; Ubach et al., 1998). As predicted, Figure 2A demonstrates that the C2AD2E mutation inhibited Ca2+ binding by the C2A domain. We assessed protein folding by CD spectroscopy to exclude misfolding of the mutant C2A domain. As shown in Figure 2B, the C2AD2E mutation does not alter the CD spectrum compared with wild-type C2A. Thus, our novel C2A mutation is correctly folded and largely inhibits Ca2+ binding by the C2A domain. D2 only directly coordinates the first Ca2+ site (Fig. 1B, D2–Ca1). If the C2AD2E mutation does in fact remove all Ca2+ binding, this would support a model in which Ca2+ binding to site 1 is requisite for Ca2+ binding to sites 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

The C2AD2E mutation inhibits Ca2+ binding by C2A without disrupting protein folding. A, ITC analysis of Ca2+ binding to the isolated C2A domain of WT and mutant Drosophila synaptotagmin 1; a representative Ca2+ titration is shown (n = 3). C2AWT bound three calcium ions (Table 1). The heat of binding of Ca2+ by C2AD2E was so small that the data could not be accurately fit. B, C2AD2E is correctly folded. The CD spectra of the mutant domain (C2AD2E) was identical to wild-type (C2AWT).

Table 1.

Thermodynamic properties of calcium binding to C2AWT using ITC

| KD (μm) | ΔH (cal/mol) | ΔS (cal/mol/K) | ΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| KD1 = 20.7 ± 3.9 | ΔH1 = 1005 ± 72.3 | ΔS1 = 24.9 ± 0.12 | ΔG1 = −6.17 |

| KD2 = 83.4 ± 19 | ΔH2 = 407.5 ± 166 | ΔS2 = 20.1 ± 0.35 | ΔG2 = −5.38 |

| KD3 = 766 ± 302 | ΔH3 = 2406 ± 597 | ΔS3 = 22.7 ± 1.3 | ΔG3 = −4.13 |

Data represent mean ± SD, n = 3. KD, Dissociation constant; Δ, change in; H, enthalpy; S, entrophy; G, Gibbs free energy.

C2A Ca2+-binding mutant inhibits synchronous transmitter release in vivo

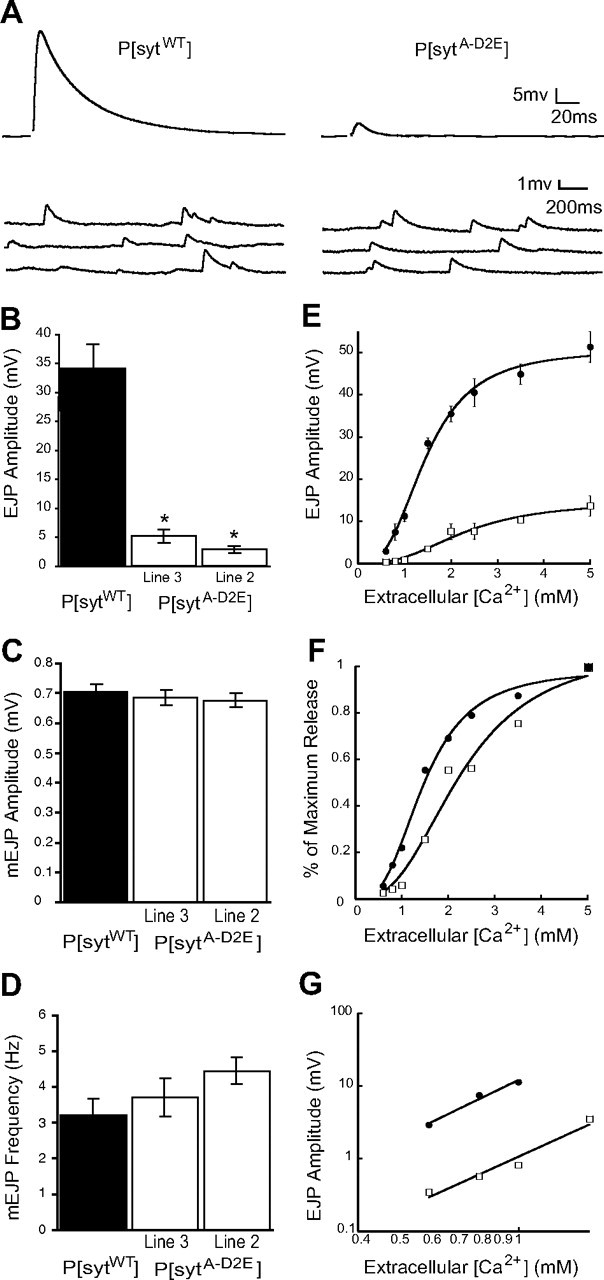

To determine the importance of electrostatic repulsion by the C2A domain for synchronous synaptic transmission at an intact synapse, we examined evoked transmitter release at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions expressing our mutant transgenic synaptotagmin protein (sytA-D2E) in the absence of any wild-type synaptotagmin 1. To indicate its transgenic origin, we will refer to the mutant as P[sytA-D2E] and the transgenic controls as P[sytWT]. We found that the sytA-D2E Ca2+-binding motif mutation, which maintains the negative charge of the C2A pocket, decreased synchronous evoked release by >80% (Fig. 3A,B). The amplitude of the EJP in P[sytA-D2E] was 5.16 ± 0.96 mV (line 3, n = 11) or 2.84 ± 0.41 mV (line 2, n = 8) compared with 34.19 ± 3.97 (n = 8) in P[sytWT] controls [Fig. 3A (line 3 shown), B, p ≪ 0.001]. There was no significant difference between the independent mutant lines (p > 0.07), demonstrating that the decrease in evoked release is not due to the insertion sites of the transgene, but rather is a direct result of the mutation.

Figure 3.

Synchronous evoked release is severely impaired in C2A Ca2+-binding mutants, but spontaneous release remains unchanged. A, Representative traces of EJPs and mEJPs recorded in saline containing 1.5 mm [Ca2+]. B, Mean EJP amplitude was markedly decreased in P[sytA-D2E] mutants compared with P[sytWT] controls (mean ± SEM, *p ≪ 0.001, one-way ANOVA). Neither mEJP amplitude (C, mean ± SEM, p > 0.7, one-way ANOVA) nor frequency (D, mean ± SEM, p > 0.15, one-way ANOVA) varied significantly between P[sytA-D2E] mutants compared with P[sytWT] controls. E, EJP amplitude versus [Ca2+] fit with the Hill equation. F, Ca2+ dose–response data normalized to the maximal response in each line to illustrate the decrease in apparent Ca2+ affinity in the P[sytA-D2E] mutant. G, EJP amplitudes within the nonsaturating range of Ca2+ on a double log plot demonstrate that the Ca2+ cooperativity of release is not changed in the P[sytA-D2E] mutants. A linear regression line was used to determine the slope. Error bars are SEM. Black circles indicate P[sytWT], white squares indicate P[sytA-D2E].

Since analogous aspartate-to-asparagine mutations in C2A, which also inhibit Ca2+ binding but partially neutralize the negative charge of the pocket, did not significantly impair synchronous evoked release at this same synapse (Robinson et al., 2002; Yoshihara et al., 2010) or at cultured excitatory synapses (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2002; Stevens and Sullivan, 2003), our findings demonstrate that the key function of Ca2+ binding to the C2A domain is to neutralize the negative charge of the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket. Thus, Ca2+ binding to the C2B domain is necessary and sufficient for synchronizing synaptic vesicle fusion to Ca2+ influx (Mackler et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2002), as seen by the low level of fast, synchronous, evoked release that remains in our P[sytA-D2E] mutants (Fig. 3A,B). But it is not sufficient to efficiently trigger the electrostatic switch. Efficient, synchronous release requires Ca2+ binding to the C2A and C2B domains to neutralize both negatively charged Ca2+-binding pockets and to flip the electrostatic switch resulting in fast, synchronous vesicle fusion.

C2A mutant does not impact spontaneous transmitter release

The C2A Ca2+-binding motif mutation had no significant effect on either the amplitude or frequency of spontaneous transmitter release. The amplitude of mEJPs in P[sytA-D2E] was 0.69 ± 0.03 mV (line 3, n = 12) or 0.68 ± 0.03 mV (line 2, n = 12) compared with 0.70 ± 0.02 mV (n = 12) in P[sytWT] (Fig. 3C, p > 0.7). The constant mEJP amplitude demonstrates that synaptic vesicle filling and the postsynaptic response to neurotransmitter are unimpaired. The frequency of mEJPs in the C2A mutants was also not significantly different at 3.71 ± 0.52 Hz (line 3) or 4.45 ± 0.37 Hz (line 2) in P[sytA-D2E] compared with 3.19 ± 0.48 Hz in P[sytWT] controls (Fig. 3D, p > 0.15). Since this C2A Ca2+-binding motif mutation results in a large decrease in evoked release (Fig. 3A,B), yet does not affect the rate of spontaneous release (Fig. 3A,D), the increase in spontaneous release seen in other synaptotagmin point mutants (Mackler and Reist, 2001; Mackler et al., 2002; Paddock et al., 2008) cannot be explained as an indirect developmental artifact resulting from the decrease in evoked release. Rather, our findings support the hypothesis that synaptotagmin plays a direct role in regulating the rate of spontaneous release (Broadie et al., 1994; Morimoto et al., 1995; Mace et al., 2009) and that the negative charge of the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket plays a key role in this process. Indeed, when Ca2+ binding is inhibited by D→N mutations of the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket, the rate of spontaneous release is increased sixfold (Yoshihara et al., 2010). This dramatic difference in the effect on spontaneous fusion frequency between D→N mutations and our D→E mutation demonstrates that the electrostatic repulsion created by the negative charge in the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket must be neutralized to enhance any fusion.

C2A mutants decrease apparent Ca2+ affinity of release

To assess whether the decrease in evoked release resulted from changes in either the apparent Ca2+ affinity or cooperativity of release, we measured EJP amplitudes in extracellular Ca2+ concentrations ranging from 0.6 to 5 mm. P[sytA-D2E] had a significantly reduced evoked response compared with the control at every extracellular Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 3E). To facilitate comparison, the data were plotted as a percentage of the maximal response (Fig. 3F). The apparent Ca2+ affinity of release in vivo was decreased in the P[sytA-D2E] mutants; 45% more Ca2+ was required to trigger a half maximal response (EC50 = 1.92 ± 0.26 mm) compared with P[sytWT] controls (EC50 = 1.33 ± 0.18 mm). By plotting the mean EJP amplitude against the extracellular Ca2+ concentration at nonsaturating levels on a double log plot (Fig. 3G), we found that the Ca2+ cooperativity of release was not affected by the sytA-D2E mutation [n = 2.52 for P[sytA-D2E] and n = 2.69 for P[sytWT], similar to previously reported values at wild-type neuromuscular junctions in Drosophila (Stewart et al., 2000; Okamoto et al., 2005)]. The shift in the Ca2+ affinity of release with no effect on the cooperativity of release is consistent with the stochastic model of cooperativity (Dodge and Rahamimoff, 1967; Stewart et al., 2000; Fernández-Chacón et al., 2001; Mackler et al., 2002). However, some synaptotagmin mutations alter the cooperativity of release, which would favor the stoicheiometric model (Dodge and Rahamimoff, 1967; Yoshihara and Littleton, 2002; Tamura et al., 2007). Further work will be necessary to discriminate between these models. Regardless, the decrease in the apparent Ca2+ affinity of evoked release is consistent with the finding that the sytA-D2E mutation specifically inhibits Ca2+ binding by the C2A domain and demonstrates that Ca2+ binding by C2A is essential for fast, synchronous synaptic transmission.

Transgene expression and distribution are unaffected

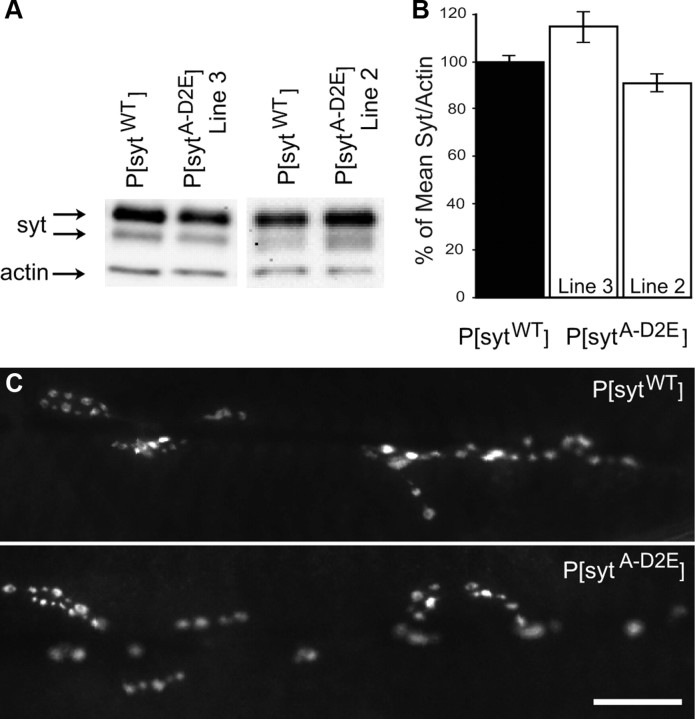

Since a decrease in synchronous evoked release could also result from protein misexpression, we assessed transgenic synaptotagmin expression levels in each transgenic line. Western blot analysis of third instar larval CNSs with an anti-synaptotagmin antibody demonstrated that the C2A Ca2+-binding motif mutant lines expressed similar levels of transgenic synaptotagmin as the transgenic control (Fig. 4A,B). In addition, the mutant synaptotagmin was appropriately localized to the neuromuscular junction (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the deficits in evoked release are not due to insufficient protein expression or protein mislocalization.

Figure 4.

Synaptotagmin expression is similar in P[sytA-D2E] mutants compared with P[sytWT] controls. A, Representative Western blots of the CNS of third instar larvae probed with anti-synaptotagmin and anti-actin antibodies. B, Synaptotagmin:actin ratio normalized to the mean ratio of the transgenic control, P[sytWT]. There was no significant difference between genotypes (mean ± SEM, p > 0.3, one-way ANOVA; P[sytWT], n = 15; P[sytA-D2E]: line 3, n = 6; line 2, n = 7). C, Synaptotagmin is properly localized to the larval neuromuscular junction in both mutant and control transgenic synaptotagmin lines. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Discussion

Our results now clearly demonstrate that Ca2+ binding by the C2A domain is a key functional component of the electrostatic switch that triggers synchronous synaptic vesicle fusion. A comparison of multiple C2A Ca2+-binding mutants reveals that the key function of Ca2+ binding by C2A is to neutralize the negative charge of this pocket. Our D→E mutant inhibits Ca2+ binding but maintains the negative charge of the C2A pocket. D→N mutants also inhibit Ca2+ binding, but they decrease the negative charge of the C2A pocket. Neutralization of the C2A pocket results in a dramatic increase in the fusion-stimulating activity of synaptotagmin.

Our C2A D→E mutant inhibits Ca2+ binding but maintains the negative charge of the C2A pocket. With the repulsive force of the C2A domain intact, both synchronous release and the apparent Ca2+ affinity of release were decreased. In C2A D→N mutants, synchronous transmitter release proceeds efficiently with Ca2+ binding to C2B, providing the synchronization to Ca2+ influx (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2002; Yoshihara et al., 2010). Indeed, C2A D→N mutants that include D4N enhanced synchronous fusion as shown by an increase in the apparent Ca2+ affinity of release (Stevens and Sullivan, 2003; Pang et al., 2006; Yoshihara et al., 2010). The major difference between these mutants is the charge of the Ca2+-binding pocket. Thus, the electrostatic repulsion provided by the C2A domain must be neutralized, by either Ca2+ binding or mutation, to activate synaptotagmin's fusion-stimulating function during synchronous transmitter release. Interestingly, one multiple C2A mutant (C2AD2,3,4A) that both inhibits Ca2+ binding and neutralizes the negative charge of the pocket decreased synchronous release by ∼30% at cultured inhibitory synapses (Shin et al., 2009). Yet similar multiple C2A D→N mutations (even the C2AD1-5N mutation) do not decrease synchronous release (Stevens and Sullivan, 2003). The effect of these mutations on spontaneous release was not reported. This differential effect may indicate that neutral asparagine (vs alanine) residues more closely mimic Ca2+-bound aspartates. Regardless of the source of these differences, the finding that our C2A D→E mutation inhibits synchronous release by 80% demonstrates that the major mechanism used by C2A to inhibit synaptotagmin's fusogenic activity is electrostatic repulsion.

The effect of mutations on spontaneous vesicle fusion events demonstrates that the negative charge of the C2A pocket acts as a clamp to inhibit an inherent fusion-stimulating activity of synaptotagmin. Our C2A D→E mutation maintains the ability of synaptotagmin to suppress spontaneous release, while C2A D→N mutations result in a massive increase in spontaneous vesicle fusion events (Yoshihara et al., 2010). Thus, regardless of the downstream effector interaction(s) that mediate the fusion reaction, the negative charge of the C2A Ca2+-binding pocket functionally inhibits synaptic vesicle fusion until neutralized.

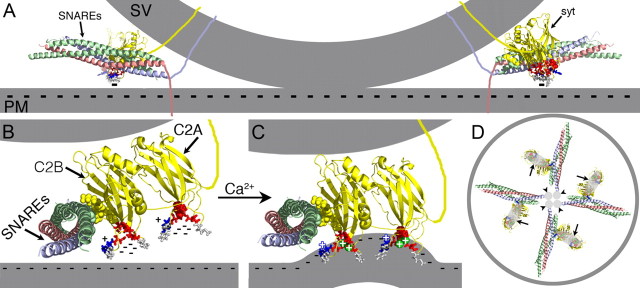

D→N mutations in both C2A and C2B increase the rate of spontaneous transmitter release (Mackler et al., 2002; Yoshihara et al., 2010), in effect removing the need for Ca2+ to unleash the fusion-stimulating activity of synaptotagmin. So why do these mutations impact synchronous release so differently? C2B D→N mutants nearly completely block synchronous release (Mackler et al., 2002), while C2A D→N mutants do not (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2002; Yoshihara et al., 2010). Here we propose a possible mechanism (Fig. 5) that may contribute to this differential action, although additional interactions must also be involved, as noted below.

Figure 5.

Ca2+ binding by C2A is an essential component of the electrostatic switch. The crystal structure of the core complex [PDB file 1SFC, containing syntaxin (red), SNAP-25 (green), and VAMP/synaptobrevin (blue)], the NMR structures of the C2A (PDB file 1BYN) and C2B (PDB file 1K5W) domains of synaptotagmin (yellow), and Ca2+ (green circles with plus signs) are shown to scale using PyMOL. The membranes, the transmembrane domains, and the link between C2A and C2B were added in Adobe Photoshop. A, Cross-section of a docked vesicle showing two SNARE complexes and their associated synaptotagmin molecules (syt). SC, Synaptic vesicle; PM, plasma membrane. B, One synaptotagmin/SNARE complex viewed from the site of vesicle/presynaptic membrane apposition. A Ca2+-independent docking/priming interaction between the C2B polylysine motif (yellow, space-filled residues) and SNAP-25 (green, space-filled residues) (Rickman et al., 2004; Loewen et al., 2006b) holds the C2B Ca2+-binding site immediately adjacent to the presynaptic membrane with the C2A Ca2+-binding site further removed. In the absence of Ca2+, the conserved aspartate residues (red residues: sytC2A-D2, space-filled; the rest as sticks) within the pockets create a high concentration of negative charge (cluster of minus signs), resulting in electrostatic repulsion of the presynaptic membrane that prevents any membrane interactions by the tips of the C2 domains. C, Upon Ca2+ binding, the electrostatic repulsion of the pockets is neutralized, thereby initiating the electrostatic switch: a strong attraction of the negatively charged membrane by the bound Ca2+ (green circles with plus signs) and the basic residues at the tips of Ca2+-binding pockets (blue stick residues, blue plus signs). Insertion of the hydrophobic residues (gray stick residues) at the tips of the C2 domains into the core of the presynaptic membrane then triggers fusion by promoting a local Ca2+-dependent positive curvature of the plasma membrane (Martens et al., 2007; Hui et al., 2009; Paddock et al., 2011). The C2 domain interactions with the membrane likely pull the synaptic vesicle (upper gray membrane) toward the presynaptic membrane (lower gray membrane). The Ca2+-induced increase in positive charge at the end of the C2B domain also likely increases the strength of the electrostatic interaction between the C2B polylysine motif and the SNARE complex, resulting in simultaneous binding of the SNARE complex and the presynaptic membrane (Davis et al., 1999; Bhalla et al., 2006; Loewen et al., 2006a; Dai et al., 2007). D, Membrane penetration by multiple synaptotagmins (large gray ovals, arrows) would pull the plasma membrane toward the vesicle in a ring around the SNARE transmembrane domains (small gray circles, arrowheads) facilitating fusion.

C2B, by virtue of its Ca2+-independent priming interaction with the SNARE complex (Rickman et al., 2004; Loewen et al., 2006b) and being the vesicle distal C2 domain, would be located immediately adjacent to the presynaptic membrane, while C2A is likely further removed. Before Ca2+ entry, electrostatic repulsion prevents interactions between the C2 domains and the negatively charged presynaptic membrane (Fig. 5A,B, minus signs). Ca2+ influx initiates the electrostatic switch: an immediate change from electrostatic repulsion (due to the negatively charged residues) to electrostatic attraction of the negatively charged presynaptic membrane (due to the bound Ca2+ and the conserved, positively charged residue; Fig. 5B,C, blue sticks, plus signs), which pulls the vesicle toward the presynaptic membrane. Hydrophobic residues on the tip of the C2 domain (Fig. 5B,C, gray sticks) can then penetrate the presynaptic membrane, destabilizing it and promoting the fusion reaction by pulling the presynaptic membrane toward the vesicle in a ring around the site of SNARE-mediated fusion (Fig. 5D). Since C2B is located immediately adjacent to the presynaptic membrane, it would attract and penetrate the membrane first (Bai et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2003; Herrick et al., 2006; Fuson et al., 2007; Martens et al., 2007; Paddock et al., 2008, 2011; Hui et al., 2009). This action may then pivot the vesicle proximal C2A domain toward the membrane where it can also then participate in the electrostatic attraction and hydrophobic penetration activities (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2001; Bai et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2003; Herrick et al., 2006; Paddock et al., 2008, 2011). When interactions of the C2B domain with the presynaptic membrane are prevented by mutation, the C2A domain would not be pivoted into position for interactions with the membrane and synaptic transmission would be blocked (Mackler et al., 2002; Paddock et al., 2011). When Ca2+ binding by the C2A domain is inhibited via D→N mutations, the decreased negative charge of the pocket may partially mimic Ca2+ binding (Stevens and Sullivan, 2003), permitting the remaining C2A lipid-interacting residues to bind and penetrate the presynaptic membrane when C2B pivots the C2A domain into position. Thus, these C2A mutations would result in little to no disruption in evoked release (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2002; Stevens and Sullivan, 2003; Pang et al., 2006). On the other hand, removal of the C2A positively charged residue (Fig. 5B,C, C2A, blue plus sign) or the hydrophobic residues (Fig. 5B,C, C2A, gray sticks) by preventing C2A from participating in effector interactions with the presynaptic membrane would result in a more severe disruption in evoked release (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2001; Paddock et al., 2008, 2011) than the D→N mutations.

Studies examining biochemical interactions between C2A domains and negatively charged phospholipids in vitro may not fully reflect interactions in vivo due to the necessarily simplified environment of the in vitro assays. For instance, the positive charge of the Ca2+ bound to C2A helps attract and bind negatively charged liposomes in vitro. D→N mutations in isolated C2A domains inhibit this lipid binding despite charge neutralization (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2002; Robinson et al., 2002). But only one or two of the five negatively charged aspartates are mutated in the D→N mutations tested. Thus, this partial charge neutralization may be insufficient to actively attract negatively charged liposomes in vitro. Yet in vivo, active attraction by bound Ca2+ may not be necessary to permit near normal membrane interactions mediated by the remaining arginine and hydrophobic residues due to the coordinated action of the SNARE-associated C2B domain to pivot the C2A pocket onto the presynaptic membrane. Additional interactions not modeled above are undoubtedly also involved.

By inhibiting Ca2+ binding yet maintaining the negative charge of the pocket, the sytA-D2E mutation would interrupt all Ca2+-dependent interactions mediated by C2A; the effect would not be limited to the membrane interactions discussed in our model above. Indeed, since the sytA-D2E mutation results in an 80% decrease of synchronous release while the C2A positively charged or hydrophobic mutations inhibit only 50% (Fernández-Chacón et al., 2001; Paddock et al., 2008, 2011), the impact of Ca2+ binding to C2A clearly influences more than just these interactions with the membrane. Thus, C2A likely participates in additional electrostatic interactions upon Ca2+ binding that play a role in triggering synchronous release, perhaps with SNARE complexes or other effector molecules. Regardless of which C2A interactions trigger fusion, the finding that C2A D→N mutations support efficient synaptic transmission while our C2A D→E mutation inhibits transmission by 80% demonstrates the central importance of the change in electrostatic potential of C2A for triggering fusion.

In summary, our current findings show severe disruption of synchronous synaptic transmission in vivo caused by inhibiting Ca2+-binding by the C2A domain without removal of the negative charge of the pocket. These results demonstrate that this negative charge in C2A is a critical component of the electrostatic inhibition that prevents synaptic vesicle fusion. Thus, the essential function of Ca2+ binding to the C2A domain of synaptotagmin is to neutralize this charge and, along with C2B, to initiate the electrostatic switch mechanism that triggers vesicle fusion.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS-045865 to N.E.R., MN-61876 to E.R.C.), the National Science Foundation (IOS-9982862 and IOS-1025966 to N.E.R.), the Microscope Imaging Network, and the College Research Council of Colorado State University. We thank Drs. Gary Pickard and Mike Tamkun for fruitful discussions and Dr. Deborah M. Garrity for comments on this manuscript.

E.R.C. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Bai J, Wang P, Chapman ER. C2A activates a cryptic Ca2+-triggered membrane penetration activity within the C2B domain of synaptotagmin I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1665–1670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032541099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla A, Chicka MC, Tucker WC, Chapman ER. Ca(2+)-synaptotagmin directly regulates t-SNARE function during reconstituted membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:323–330. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadie K, Bellen HJ, DiAntonio A, Littleton JT, Schwarz TL. Absence of synaptotagmin disrupts excitation-secretion coupling during synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10727–10731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N, Petrenko AG, Südhof TC, Jahn R. Synaptotagmin: a calcium sensor on the synaptic vesicle surface. Science. 1992;256:1021–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1589771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae YK, Abildgaard F, Chapman ER, Markley JL. Lipid binding ridge on loops 2 and 3 of the C2A domain of synaptotagmin I as revealed by NMR spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25659–25663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman ER, Davis AF. Direct interaction of a Ca2+-binding loop of synaptotagmin with lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13995–14001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman ER, Hanson PI, An S, Jahn R. Ca2+ regulates the interaction between synaptotagmin and syntaxin 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23667–23671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho W, Stahelin RV. Membrane binding and subcellular targeting of C2 domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:838–849. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton TE. Proteins: structure and molecular properties. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Shen N, Araç D, Rizo J. A quaternary SNARE-synaptotagmin-Ca2+-phospholipid complex in neurotransmitter release. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:848–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AF, Bai J, Fasshauer D, Wolowick MJ, Lewis JL, Chapman ER. Kinetics of synaptotagmin responses to Ca2+ and assembly with the core SNARE complex onto membranes. Neuron. 1999;24:363–376. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80850-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davletov B, Perisic O, Williams RL. Calcium-dependent membrane penetration is a hallmark of the C2 domain of cytosolic phospholipase A2 whereas the C2A domain of synaptotagmin binds membranes electrostatically. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19093–19096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A, Parfitt KD, Schwarz TL. Synaptic transmission persists in synaptotagmin mutants of Drosophila. Cell. 1993;73:1281–1290. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90356-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge FA, Jr, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action of calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elferink LA, Peterson MR, Scheller RH. A role for synaptotagmin (p65) in regulated exocytosis. Cell. 1993;72:153–159. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez I, Araç D, Ubach J, Gerber SH, Shin O, Gao Y, Anderson RG, Südhof TC, Rizo J. Three-dimensional structure of the synaptotagmin 1 C2B-domain: synaptotagmin 1 as a phospholipid binding machine. Neuron. 2001;32:1057–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Chacón R, Königstorfer A, Gerber SH, García J, Matos MF, Stevens CF, Brose N, Rizo J, Rosenmund C, Südhof TC. Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium regulator of release probability. Nature. 2001;410:41–49. doi: 10.1038/35065004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Chacón R, Shin OH, Königstorfer A, Matos MF, Meyer AC, Garcia J, Gerber SH, Rizo J, Südhof TC, Rosenmund C. Structure/function analysis of Ca2+ binding to the C2A domain of synaptotagmin I. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8438–8446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08438.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuson KL, Montes M, Robert JJ, Sutton RB. Structure of human synaptotagmin 1 C2AB in the absence of Ca2+ reveals a novel domain association. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13041–13048. doi: 10.1021/bi701651k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick DZ, Sterbling S, Rasch KA, Hinderliter A, Cafiso DS. Position of synaptotagmin I at the membrane interface: cooperative interactions of tandem C2 domains. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9668–9674. doi: 10.1021/bi060874j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui E, Johnson CP, Yao J, Dunning FM, Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin-mediated bending of the target membrane is a critical step in Ca(2+)-regulated fusion. Cell. 2009;138:709–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen CA, Mackler JM, Reist NE. Drosophila synaptotagmin I null mutants survive to early adulthood. Genesis. 2001;31:30–36. doi: 10.1002/gene.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen CA, Royer SM, Reist NE. Drosophila synaptotagmin I null mutants show severe alterations in vesicle populations but calcium-binding motif mutants do not. J Comp Neurol. 2006a;496:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cne.20868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen CA, Lee SM, Shin YK, Reist NE. C2B polylysine motif of synaptotagmin facilitates a Ca2+-independent stage of synaptic vesicle priming in vivo. Molec Biol Cell. 2006b;17:5211–5226. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace KE, Biela LM, Sares AG, Reist NE. Synaptotagmin I stabilizes synaptic vesicles via its C2A polylysine motif. Genesis. 2009;47:337–345. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackler JM, Reist NE. Mutations in the second C2 domain of synaptotagmin disrupt synaptic transmission at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:4–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackler JM, Drummond JA, Loewen CA, Robinson IM, Reist NE. The C(2)B Ca(2+)-binding motif of synaptotagmin is required for synaptic transmission in vivo. Nature. 2002;418:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature00846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens S, Kozlov MM, McMahon HT. How synaptotagmin promotes membrane fusion. Science. 2007;316:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1142614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T, Popov S, Buckley KM, Poo MM. Calcium-dependent transmitter secretion from fibroblasts: modulation by synaptotagmin I. Neuron. 1995;15:689–696. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D, Honig B. Electrostatic control of the membrane targeting of C2 domains. Mol Cell. 2002;9:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalefski EA, Falke JJ. The C2 domain calcium-binding motif: structural and functional diversity. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2375–2390. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Tamura T, Suzuki K, Kidokoro Y. External Ca2+ dependency of synaptic transmission in drosophila synaptotagmin I mutants. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:1574–1586. doi: 10.1152/jn.00205.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock BE, Striegel AR, Hui E, Chapman ER, Reist NE. Ca2+-dependent, phospholipid-binding residues of synaptotagmin are critical for excitation-secretion coupling in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7458–7466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0197-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock BE, Wang Z, Biela LM, Chen K, Getzy MD, Striegel A, Richmond JE, Chapman ER, Featherstone DE, Reist NE. Membrane penetration by synaptotagmin is required for coupling calcium binding to vesicle fusion in vivo. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2248–2257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3153-09.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Shin OH, Meyer AC, Rosenmund C, Südhof TC. A gain-of-function mutation in synaptotagmin-1 reveals a critical role of Ca2+-dependent soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor complex binding in synaptic exocytosis. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12556–12565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3804-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reist NE, Buchanan J, Li J, DiAntonio A, Buxton EM, Schwarz TL. Morphologically docked synaptic vesicles are reduced in synaptotagmin mutants of Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7662–7673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07662.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickman C, Archer DA, Meunier FA, Craxton M, Fukuda M, Burgoyne RD, Davletov B. Synaptotagmin interaction with the syntaxin/SNAP-25 dimer is mediated by an evolutionarily conserved motif and is sensitive to inositol hexakisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12574–12579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson IM, Ranjan R, Schwarz TL. Synaptotagmins I and IV promote transmitter release independently of Ca(2+) binding in the C(2)A domain. Nature. 2002;418:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature00915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavo G, Stenbeck G, Rothman JE, Söllner TH. Binding of the synaptic vesicle v-SNARE, synaptotagmin, to the plasma membrane t-SNARE, SNAP-25, can explain docked vesicles at neurotoxin-treated synapses [see comments] Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:997–1001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X, Davletov BA, Sutton RB, Südhof TC, Rizo J. Bipartite Ca2+-binding motif in C2 domains of synaptotagmin and protein kinase C. Science. 1996;273:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin OH, Xu J, Rizo J, Südhof TC. Differential but convergent functions of Ca2+ binding to synaptotagmin-1 C2 domains mediate neurotransmitter release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16469–16474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908798106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Sullivan JM. The synaptotagmin C2A domain is part of the calcium sensor controlling fast synaptic transmission. Neuron. 2003;39:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart BA, Mohtashami M, Trimble WS, Boulianne GL. SNARE proteins contribute to calcium cooperativity of synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13955–13960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250491397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RB, Davletov BA, Berghuis AM, Südhof TC, Sprang SR. Structure of the first C2 domain of synaptotagmin I: a novel Ca2+/phospholipid-binding fold. Cell. 1995;80:929–938. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T, Hou J, Reist NE, Kidokoro Y. Nerve-evoked synchronous release and high K+-induced quantal events are regulated separately by synaptotagmin I at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:540–549. doi: 10.1152/jn.00905.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubach J, Zhang X, Shao X, Südhof TC, Rizo J. Ca2+ binding to synaptotagmin: how many Ca2+ ions bind to the tip of a C2-domain? EMBO J. 1998;17:3921–3930. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Wang CT, Bai J, Jackson MB, Chapman ER. Mutations in the effector binding loops in the C2A and C2B domains of synaptotagmin I disrupt exocytosis in a nonadditive manner. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47030–47037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao KM, White K. Neural specificity of elav expression: defining a Drosophila promoter for directing expression to the nervous system. J Neurochem. 1994;63:41–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63010041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara M, Littleton JT. Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium sensor to synchronize neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2002;36:897–908. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara M, Guan Z, Littleton JT. Differential regulation of synchronous versus asynchronous neurotransmitter release by the C2 domains of synaptotagmin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14869–14874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000606107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Kim-Miller MJ, Fukuda M, Kowalchyk JA, Martin TF. Ca2+-dependent synaptotagmin binding to SNAP-25 is essential for Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Neuron. 2002;34:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]