Background: Staphylococcus epidermidis senses and responds to oxidative stress through an unknown mechanism.

Results: The paper describes AbfR, the first oxidation sensor of S. epidermidis.

Conclusion: AbfR plays key roles in oxidative stress responses, bacterial aggregation, and biofilm formation in S. epidermidis.

Significance: Oxidative stress signals S. epidermidis to modulate key virulence properties through AbfR.

Keywords: Bacterial Signal Transduction, Biofilm, Oxidative Stress, Structural Biology, Transcription Regulation, Oxidation-sensing Regulator, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacterial Aggregation, Biofilm Formation

Abstract

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a notorious human pathogen that is the major cause of infections related to implanted medical devices. Although redox regulation involving reactive oxygen species is now recognized as a critical component of bacterial signaling and regulation, the mechanism by which S. epidermidis senses and responds to oxidative stress remains largely unknown. Here, we report a new oxidation-sensing regulator, AbfR (aggregation and biofilm formation regulator) in S. epidermidis. An environment of oxidative stress mediated by H2O2 or cumene hydroperoxide markedly up-regulates the expression of abfR gene. Similar to Pseudomonas aeruginosa OspR, AbfR is negatively autoregulated and dissociates from promoter DNA in the presence of oxidants. In vivo and in vitro analyses indicate that Cys-13 and Cys-116 are the key functional residues to form an intersubunit disulfide bond upon oxidation in AbfR. We further show that deletion of abfR leads to a significant induction in H2O2 or cumene hydroperoxide resistance, enhanced bacterial aggregation, and reduced biofilm formation. These effects are mediated by derepression of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 that lie immediately downstream of the abfR gene in the same operon. Thus, oxidative stress likely acts as a signal to modulate S. epidermidis key virulence properties through AbfR.

Introduction

Staphylococcus epidermidis is the leading cause of infections related to implanted medical devices (1) in large part because of its ability to form highly resistant biofilm (2, 3). Similar to other human pathogens, S. epidermidis must cope with reactive oxygen species derived either from host defense systems or the normal course of aerobic metabolism (4). However, the mechanism in S. epidermidis for sensing and responding to oxidative stress remains largely unknown. Recent reports indicate that oxidative stress down-regulates the development of biofilm in S. epidermidis (5, 6).

Transcriptional regulators in bacteria have evolved to sense the reactive oxygen species to coordinate the appropriate oxidative stress response (4, 7). Three peroxide-sensing transcriptional regulators, namely OxyR, PerR, and OhrR, have been well studied (8–10). OxyR and PerR are primarily responsive sensors of H2O2, whereas OhrR senses organic peroxide. OhrR belongs to the MarR family proteins, which number over 12,000 and are widely distributed within bacteria and archaea (11). In addition to OhrR (12–17), other transcriptional regulators within the MarR family also play key roles in sensing oxidative stress and regulating bacteria responses (15, 18–24). In particular, recent studies of OspR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa have shown that the activity of the oxidative stress-sensing regulators is not limited to oxidative stress response but has pleiotropic effects (21). In the Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, the MarR family proteins MgrA, SarZ, and SarA use cysteine oxidation to regulate antibiotic resistance and virulence (19, 22, 25). It is now understood that oxidation sensing and regulation affect diverse pathways beyond antioxidant genes in bacteria (7, 10, 26).

So far, the method used by S. epidermidis to detect and respond to oxidative stress is poorly understood. Not a single oxidation sensor in S. epidermidis has been described. Here, we present the first redox active regulator, AbfR, in S. epidermidis. AbfR belongs to the MarR family and resembles a two-cysteine type redox-sensing regulator. AbfR is involved in oxidative stress responses, bacterial aggregation, and biofilm formation. We further show that these effects of AbfR are mediated by the regulation of the downstream genes SERP2195 and gpxA-2. These results highlight the roles of redox-sensing regulator AbfR in modulating the key virulence properties of S. epidermidis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

S. epidermidis was grown at 37 °C with aeration in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Oxoid)3 or BM medium (per liter containing 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, 1 g of K2HPO4, and 1 g of glucose) as indicated. For plasmid maintenance in S. epidermidis, the medium was supplemented with 10 μg/ml erythromycin or chloramphenicol. Escherichia coli strains were routinely cultivated in LB (Difco) supplemented with 10 μg/ml ampicillin or 50 μg/ml kanamycin where appropriate. The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Construction of S. epidermidis ΔabfR Strain

The pKOR1 vector was used to construct an in-frame, unmarked abfR-null mutant (ΔabfR) (27, 28). 1,027-bp DNA fragments upstream and 1027-bp DNA fragments downstream of abfR were PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of S. epidermidis 1457 by using the primer pair attB2-SE2196-up-F/SE2196-NR-sacII and SE2196-CR-sacII/attB1-SE2196-CF, respectively. The two PCR products were digested with SacII and then ligated with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). After further purification, the ligation product was recombined within pKOR1, and the product was introduced to E. coli DH5α. The resulting plasmid pKOR1::ΔabfR was electroporated into RN4220 and subsequently into S. epidermidis 1457. After the allelic replacement, PCR analyses and DNA sequencing were performed to confirm the deletion of abfR.

Plasmid Construction for Constitutive Expression of abfR and SERP2195-gpxA

To construct a plasmid for the complementation of the ΔabfR strain, a 488-bp DNA fragment (covering 22 bp upstream of abfR gene, the abfR gene, and 25 bp downstream of abfR gene) was prepared by PCR using primer pair SE2196CF/SE2196CR and cloned into broad host range vector pYJ335, where the abfR gene was downstream of the tetracycline-inducible xyl/tetO promoter as previously described (19, 29), thus yielding plasmid pYJ335::abfR. Two mutations, pYJ335::abfRC13S and pYJ335::abfRC116S, were constructed by using the primer pairs C13SF/C13SR and C116SF/C116SR, respectively, through the use of a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). To simultaneously express both SERP2195 and gpxA-2 constitutively, a 2,033-bp DNA fragment was generated using the primers SE2195-gpxAF and SE2195-gpxAR and then cloned into pYJ335 in the same orientation as the tetracycline-inducible xyl/tetO promoter, yielding plasmid pYJ335::2195-gpxA. All of the constructs were sequenced to ensure that no unwanted mutations were introduced.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from exponential phase cells (A600 = 0.8) using a RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen). The cell pellets were resuspended in 700 ml of RLT buffer (supplied in kit) supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol in FastPrep tubes. The cells were lysed in a FastPrep-24 high speed homogenizer (MP Biomedicals) at the following settings: speed, 6.0; time, 30 s. This procedure was performed in triplicate, and the lysate was put on ice for 3 min in between each lysis cycle. DNA contamination was removed by in-column DNase I treatment.

The qRT-PCRs were performed on the Prism 7500 real time PCR system (ABI). 1000 ng of total RNA was reversely transcribed using a PrimeScript® RT reagent kit (Takara). Of a total volume of 20 μl of reverse transcription reaction, 0.4 μl was taken and used as a template with each specific primer pair in the presence of SYBR green PCR master mix. The gyrB gene was chosen as an internal control. The transcript level of gyrB was observed to be consistent at various growth stages (data not shown). Primer pairs RT-SE2196F/RT-SE2196R, RT-SE2195F/RT-SE2195R, and RT-gpxAF/RT-gpxAR were used for detection of the expression of abfR, SERP2195, and gpxA-2, respectively. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the transcript levels were estimated relative to those of gyrB gene.

Plate Assay for Oxidative Sensitivity

Bacterial overnight culture grown in BM was diluted 1:100 with fresh BM medium and incubated at 37 °C with aeration for 3 h until A600 was approximately 0.8. After several 1:10 serial dilutions, each aliquot of 10 or 5 μl was spotted onto a TSB agar plate in the presence of either CHP or H2O2 at varying concentrations. Bacteria growth on the oxidant-containing medium was recorded after incubation at 37 °C overnight.

Protein Expression and Purification

abfR gene was amplified using primer pair SE2196PF/SE2196PR, and the purified genomic DNA of S. epidermidis RP62A was used as a template. Ligation-independent cloning of abfR into plasmid pMCSG19 was typically carried out as described previously (30). Shortly, the purified PCR product was treated with T4 DNA polymerase (Takara) in the presence of 2.5 mm dCTP. The insert was then annealed to linearized pMCSG19 and transformed into E. coli strain DH5α. The resulting plasmid (pMCSG19::abfR) was further transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3).

For protein expression and purification, the cells were grown at 37 °C in LB until A600 of 0.6 was reached and then induced with 1 mm of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside at 30 °C for 4 h. The cells were harvested, and cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol) and sonicated. The lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatants were loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (His Trap; GE Healthcare). After being equilibrated with buffer A, His-tagged AbfR was eluted using a linear gradient of 20–400 mm imidazole. Fractions enriched for AbfR were pooled, and the His tag was then cleaved from the protein with the tobacco etch virus protease. After a second nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid was run, tag-free AbfR proteins were eluted from the column in buffer A.

A QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to construct plasmid pMCSG19::abfRC13S, pMCSG19::abfRC116S, and pMCSG19::abfRL44ML72M by using the primers pairs C13SF/C13SR, C116SF/C116SR, and L44MF/L44MR, and L72MF/L72MR, respectively. Selenomethionine-substituted SeMet-AbfRL44ML72M protein was expressed using the methionine biosynthesis inhibition method (31). The expression and purification of C13S and C116S mutants were performed as described above.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Briefly, 20 μl of the mixture of the DNA probe (50 nm), purified AbfR proteins, and 50 pg/ml sonicated salmon sperm DNA in binding buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 50 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 10% glycerol) were incubated on ice for 15 min. For oxidation, CHP was added to the binding reaction and incubated for another 30 min at room temperature. When indicated, DTT was added into the solution, and incubation was continued at room temperature for 30 min. After being mixed with 3 μl of loading buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mm KCl, 50% glycerol, and 0.05% bromphenol blue), the samples were run on a native polyacrylamide gel (6%) in 0.5× TB buffer (50 mm Tris, 41.5 mm borate, pH 8.0) at 4 °C. The gel was stained in GelRed nucleic acid staining solution (Biotium) for 10 min, and then the DNA bands were visualized by gel exposure to 260-nm UV light.

Dye Primer-based DNase I Footprinting Assay

The published DNase I footprint protocol was modified (32) in this study. A 268-bp fragment, covering bases −150 to 118 in the promoter region of abfR, was generated by PCR using the primer set FootprintF-FAM/FootprintR. 50 nm 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled abfR promoter DNA and 300 nm AbfR or BSA in 50 μl of binding buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 50 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 50 pg/ml sonicated salmon sperm DNA) was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Then 0.01 unit of DNase I was added to the reaction mixture, and it was incubated for 5 more min. The digestion was terminated by adding 90 μl of quenching solution (200 mm NaCl, 30 mm EDTA, 1% SDS), and then the mixture was extracted with 200 μl of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). The digested DNA fragments were isolated by ethanol precipitation. 5.0 μl of digested DNA was mixed with 4.9 μl of HiDi formamide and 0.1 μl of GeneScan-500 LIZ size standards (Applied Biosystems). A 3730XL DNA analyzer detected the sample, and the result was analyzed with GeneMapper software. The assay was repeated at least three times with similar results.

5,5′-Dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic Acid (DTNB) Assay

The purified reduced wild-type and mutant AbfR were buffer-exchanged to 2 × DTNB assay buffer (200 mm KH2PO4-K2HPO4, 200 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, pH 7.0) at 4 °C. The samples were oxidized by 2 eq of CHP at room temperature for 30 min. Excess of CHP was removed by desalting. Then the reduced and oxidized proteins were denatured by mixing with the same volume of 8 m guanidine HCl and heating at 95 °C for 20 min followed by quenching on ice. After treatment with an excess of DTNB, the spectrum of the samples were taken against a blank in the absence of the protein. The absorption at 412-nm wavelength from each sample was recorded, and the free thiol concentrations were calculated by using the known method (22).

Crystallization and Structure Determination of AbfR

Crystallization was performed using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 22 °C. SeMet-AbfRL44ML72M protein was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in buffer B (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine). 1 μl of protein solution was mixed with 1 μl of reservoir solution (0.1 m sodium acetate trihydrate, pH 4.8, 2.0 m ammonium sulfate) and equilibrated against 0.4 ml of reservoir solution. High quality crystals were grown within 3 days and were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen following cryoprotection with the reservoir solution containing an extra 20% of glycerol. The diffraction data were collected at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility Beamline 17U. All of the x-ray data were processed using HKL2000 program suite (33) and converted to structural factors within the CCP4 program (34). Phasing was solved in SHELX using single-wavelength anomalous dispersion data (35). A structural model was manually built in COOT (36), and computational refinement was carried out with the program REFMAC5 (37) in the CCP4 suite. Structural graphic figures were prepared in PyMOL (38).

Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Oxidized AbfR

The purified AbfR protein in reduced form was buffer-exchanged to 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl through a desalting column (HiTrap; GE Healthcare) at 4 °C. The protein was exposed to 5 eq of CHP at room temperature for 30 min. After chromatographic purification and SDS-PAGE analyses, the reduced and oxidized AbfR samples were digested by trypsin (Promega) in an enzyme to substrate ratio of 1:60 (w/w), respectively, at 37 °C for 16 h. The addition of benzamidine to a final concentration of 4 μm quenched the digestion. After being desalted, the peptide mixtures were separated by a reverse phase, ultra performance liquid chromatography (Waters) on C18 column (Agilent Eclipse Plus, 100 × 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm) at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min using 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile as mobile phases. The elution program consisted of 5% acetonitrile held for 1 min, and then acetonitrile was linearly increased to 99% within 14 min. The ultra performance liquid chromatography effluent was subjected to electrospray ionization quadrupole-TOF mass spectrometric analysis (Waters). The data were acquired using Masslynx v4.1 (Waters).

Biofilm Formation Assay

As previously described, the microtiter plate test was used to quantify the biofilm (39, 40) with slight modifications. Briefly, overnight culture of S. epidermidis strains in BM medium was diluted 1:100 in fresh BM and grown with aeration at 37 °C for 12 h. The culture was further diluted in fresh TSB to A600 of 0.01 and then inoculated into a sterile 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (200 μl/well). After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the culture supernatants were gently removed, and the wells were washed three times with PBS, pH 7.4. The adherent organisms that remained at the bottom of wells were fixed with Bouin fixative for 15 min. The fixative was removed, and the wells were washed with PBS. Then the adherent bacteria were stained with crystal violet, and the excessive stain was gently washed with very slow running water. After being dried, the stained biofilm was determined with a Micro ELISA auto reader (Bio-Rad) at a wavelength of 570 nm.

Electron Microscopy

For scanning EM (SEM) analyses, S. epidermidis strains were grown in TSB at 37 °C for 14 h on the surface of sterile glass slides, which were deposited in advance in each well of a 6-well hydroxylapatite disks. The contents of each well were then carefully aspirated with a pipette, rinsed three times with PBS, and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS at 4 °C overnight. Progressive alcohol dehydration was performed, followed by specimen-critical point drying. After being mounted on conventional SEM stubs with silver glue, the slides were gold-sputtered. Observations were carried out with a JEOL/EO (version 1.0) scanning electron microscope.

Transmission EM of strains was also performed to confirm the identification of features observed in the SEM An overnight culture of S. epidermidis in TSB was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS at 4 °C. The cells were washed with 0.1 m sodium cacodylate and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate for 1 h. The samples were washed with 0.1 m sodium cacodylate, dehydrated using a graded series of ethanol, subjected to two changes of propylene oxide, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultra thin (65–1,4970 nm) serial sections were obtained using a Leica Ultracut microtome and collected on copper grids. The samples were contrast-stained with 2% uranyl acetate followed by Reynold's lead citrate and examined using a JEOL JEM-1230 transmission electron microscope operated at 80 KeV.

The biofilms were also examined with confocal laser scanning microscopy. In brief, S. epidermidis cells were cultivated in cover glass cell culture dishes (WPI Inc.) as previously described (40–42). An overnight culture of S. epidermidis in BM grown was diluted to A600 of 0.001 with TSB, then inoculated into the dish (2 ml/dish), and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The dish was gently washed three times with 1 ml of sterile PBS and then stained with LIVE/DEAD reagents that indicate viable cells by green fluorescence (SYTO9) and dead cells by red fluorescence (PI) for 15 min. Examination with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope followed.

RESULTS

Identification of P. aeruginosa OspR/S. aureus MgrA Homologue AbfR in S. epidermidis

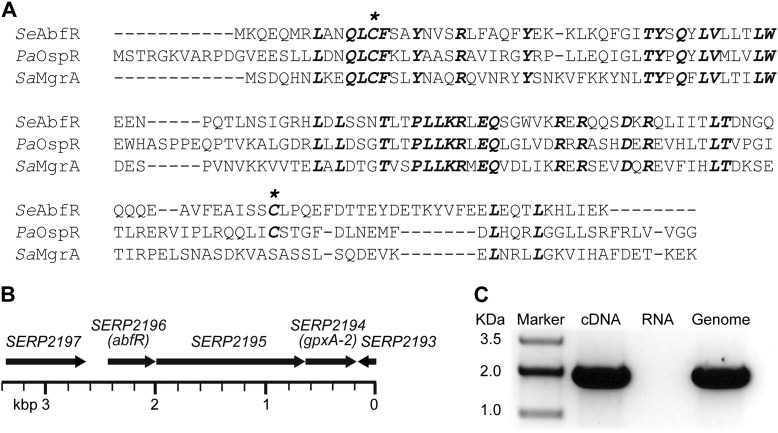

Our previous work has shown that the MarR family transcriptional regulator OspR, homologous to MgrA, plays a key role in antibiotic resistance and virulence regulation in P. aeruginosa (21). To identify the OspR homologues in S. epidermidis, we performed BLASTP analyses with OspR against the genome of S. epidermidis RP62A. The most significant hit was SERP2196, which exhibited 47% identity to OspR and shared 43% identity with S. aureus MgrA (Fig. 1A). We renamed SERP2196 as AbfR based on observed phenotypes presented in this study. Similar to OspR, AbfR harbors two cysteine residues at positions 13 and 116 (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Deduced structure and genomic environment of abfR in S. epidermidis. A, sequence alignment of SeAbfR, PaOspR, and SaMgrA was performed with Clustal Omega (67). The identical residues are highlighted in bold italic type. Asterisks indicate the cysteine residues. B, genetic context of the abfR locus is shown. The ORF number is indicated according to the S. epidermidis RP62A strain annotation. C, shown is co-transcription of abfR and gpxA-2. cDNA indicates co-transcriptional analyses of abfR and gpxA-2. RNA represents negative controls without reverse transcriptase. Genome represents positive controls using chromosomal DNA from S. epidermidis RP62A strain.

DNA sequence analysis implies that abfR, SERP2195, and gpxA-2 are likely the same operon (Fig. 1B). To confirm this, we carried out reverse transcriptase-PCR using the primer pair RT-SE2196R/RT-gpxAF, which encompasses the abfR-SERP2195 intergenic region and the 3′ end of gpxA-2 gene. A PCR without reverse transcriptase was also carried out to exclude the presence of contaminating genomic DNA in the mRNA preparations. As shown in Fig. 1C, the primer pair RT-SE2196R/RT-gpxAF amplified fragments of expected size (1,871 bp), which could not be detected in the reaction without reverse transcriptase. These results suggest that abfR, SERP2195, and gpxA-2 are transcribed as a single mRNA.

AbfR Is Involved in the Cellular Response to Oxidative Stress

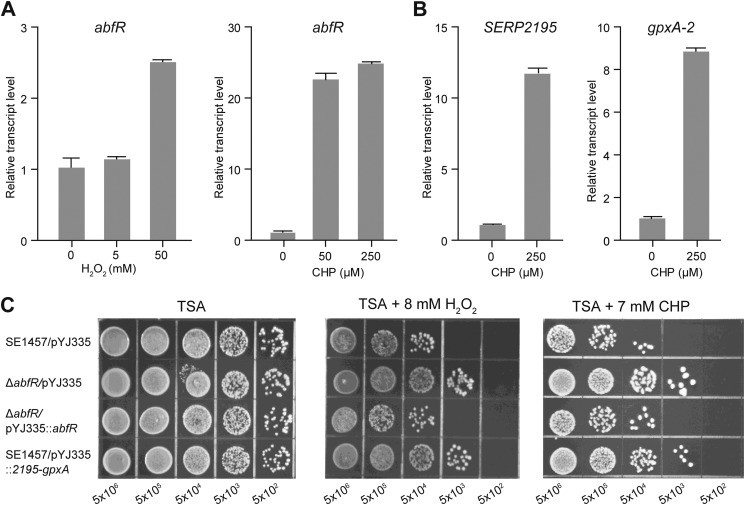

To assess whether abfR responds to oxidative stress, we used qRT-PCR to analyze the expression of abfR in the S. epidermidis 1457 strain after the H2O2 and CHP challenge, respectively. We observed a 2.6-fold increase in the expression of abfR gene after a 30-min treatment with 50 mm H2O2 (Fig. 2A). A significant increase (25-fold) in abfR mRNA was observed under the stress of 250 μm CHP (Fig. 2A). In addition, we also analyzed the expression of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 because these two genes are co-transcribed with the abfR gene. As expected, CHP challenge apparently (> 9-fold) induces the expressions of either SERP2195 or gpxA-2 (Fig. 2B). We then used a stress plate assay to test the sensitivity of the ΔabfR strain to oxidative stress. As shown in Fig. 2C, the ΔabfR strain was ∼10-fold more resistant to H2O2 or CHP stress than the wild-type and complemented strains, indicating that abfR plays a key role in cellular response to oxidative stress in S. epidermidis.

FIGURE 2.

Gene expressions and phenotypes of S. epidermidis strains under oxidative stresses. Total RNA was extracted from S. epidermidis 1457 cultures (A600 = 0.8) treated with H2O2 or CHP for 30 min. A, qRT-PCR analyses of the transcripts of abfR in the presence of H2O2 and CHP, respectively. B, qRT-PCR analyses of the transcripts of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 under CHP stress. C, sensitivities of wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 strain harboring plasmid pYJ335 (SE1457/pYJ335), ΔabfR/pYJ335 strain, complemented strains (ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR), and the SERP2195/gpxA-2 constitutive expression strain (SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA) to oxidants. Exponential phase cells grown in BM medium were serially diluted (1:10 dilutions), and 10 μl of each dilution was spotted onto TSA agar containing either 8 mm H2O2 or 7 mm CHP. After incubation at 37 °C for ∼24 h, growth of the bacteria was observed. All of the experiments were performed in triplicate.

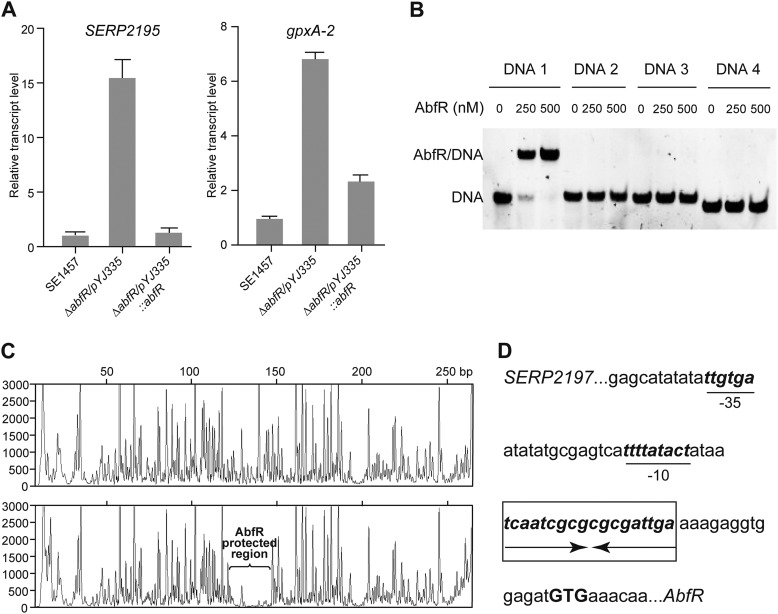

AbfR Modulates abfR, SERP2195, and gpxA-2 Expression

qRT-PCR analysis was employed to examine the expression level of the SERP2195 gene in the ΔabfR strain. The mRNA level of SERP2195 gene was dramatically overexpressed (15-fold) in the ΔabfR strain compared with the wild-type strain, which could be restored to the wild-type level in an abfR complementation strain (pYJ335::abfR) (Fig. 3A). Similarly, deletion of abfR also led to overexpression (6.5-fold) of the gpxA gene (Fig. 3A). Thus, the expression of abfR gene is negatively autoregulated by its own product AbfR, because abfR, SERP2195, and gpxA-2 are co-transcribed in a single mRNA.

FIGURE 3.

Quantitative PCR, gel shift assay, and DNase I footprint analysis. A, expression levels of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 in SE1457/pYJ335, ΔabfR/pYJ335, and ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR were estimated by qRT-PCR. The experiment was replicated four times, and similar results were obtained. B, EMSA shows AbfR selectively bound to a 50-bp fragment DNA1, which included the putative −10 and −35 promoter regions. The sequence of DNAs 1–4 are listed in supplemental Table S2. C, AbfR binding site was determined by DNase I footprint assay. Electropherograms show the protection pattern of the abfR promoter in the absence or presence of 0.3 mm AbfR. The AbfR-protected region is indicated in the lower panel. D, the abfR promoter sequence (−31 to −8 from putative start codon GTG) is shown. The putative −35 and −10 promoter regions are underlined. Arrows show the palindromic AbfR-binding sequence that is highlighted in bold type within a box.

EMSA was used to test the direct interaction of AbfR protein with its promoter DNA. The purified AbfR bound specifically to a 50-bp DNA fragment (−50 to −1 upstream of the start codon, DNA1). This fragment includes the putative −10 and −35 promoter regions of abfR, although it failed to shift three other DNA fragments (−150 to −101, −100 to −51, and −83 to −40 upstream of the start codon, respectively) located upstream of abfR (Fig. 3B). To probe further the binding site of AbfR within DNA1, we performed a DNase I footprint assay. A specific AbfR-protected region (approximately −31 to −8 upstream of the start codon of abfR) was found within the abfR promoter DNA (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the AbfR-protected region harbors a palindromic sequence of 18 bp, 5′-TCAATCGCGCGCGATTGA-3′ (Fig. 3D).

SERP2195 encodes the E3 component of α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex, whereas gpxA-2 encodes a glutathione peroxidase, indicating their putative functions in response to oxidative stress (43, 44). Thus, it is tempting to suppose that the overexpression of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 might contribute to enhanced resistance against oxidative stress in the ΔabfR strain. To this end, the SERP2195/gpxA-2 constitutive expression strain (SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA) was constructed; additional stress plate assays were performed thereafter. This strain displayed 1 order of magnitude more resistance to H2O2 or CHP than the parental strain (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results indicate that 1) AbfR contributes in adaptive response to oxidative stress in S. epidermidis, and 2) this process is mediated by modulating the expression of SERP2195 and gpxA-2, at least in part.

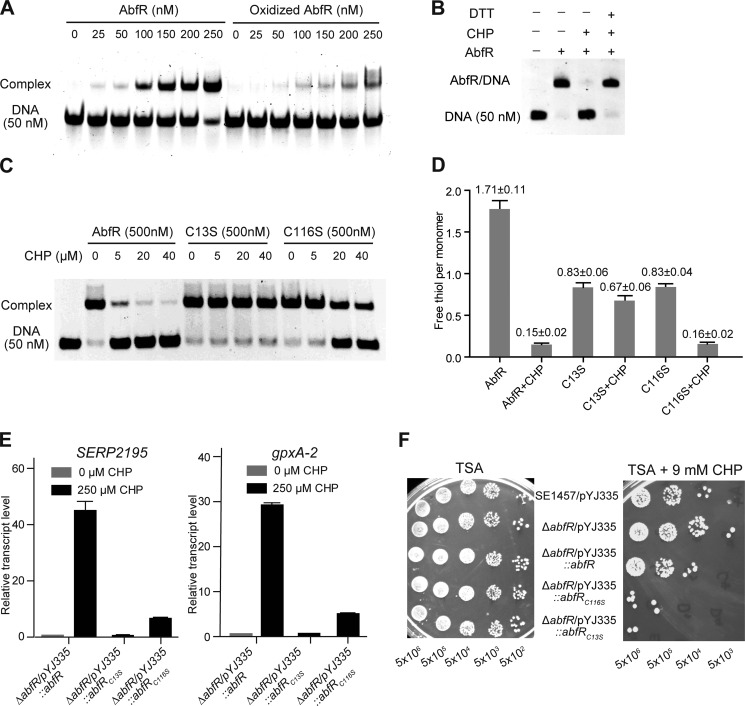

Cys-13 and Cys-116 Are the Key Functional Residues in AbfR

Suspecting that oxidation with H2O2 or CHP might lead to dissociation of AbfR from its promoter DNA and then derepression of abfR-SERP2195-gpxA-2 operon in S. epidermidis, we performed EMSA with the purified AbfR protein and the specific 50-bp DNA1. The addition of CHP led to dissociation of AbfR from DNA1 (Fig. 4A). In addition, the binding of AbfR and DNA1 could be restored by the addition of the excess DTT (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that AbfR likely serves as a redox-sensing regulator.

FIGURE 4.

Role of cysteine residues in the regulatory function of AbfR. A, EMSA shows the binding between DNA1 and the reduced and oxidized AbfR proteins. CHP oxidation led to AbfR dissociation from the promoter DNA1. B, switching of EMSA binding between AbfR and DNA1 under the oxidized and reduced conditions. EMSA assays were performed on 50 nm DNA1 and 0.5 μm AbfR and 100 μm CHP or 1 mm DTT as indicated. A plus sign indicates the presence of a feature, and a minus sign indicates the absence of a feature. C, the binding of AbfR, AbfRC13S, and AbfRC116S to DNA1 under CHP exposure is shown. EMSA was performed on 50 nm DNA1, 0.5 μm protein, and CHP at varying concentration. D, DTNB analyses of the wild-type and mutant AbfR proteins treated or untreated with CHP are shown. E, qRT-PCR analyses of the transcripts of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 in a strain of ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR, ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfRC13S, and ΔabfR/pYJ335:: abfRC116S, which were treated or untreated with CHP. F, plate assay showing sensitivities of S. epidermidis strains to CHP. Exponential phase cells grown in BM medium were serially diluted (1:10 dilutions), and 5 μl of each dilution was spotted onto TSA agar plate containing 9 mm CHP. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for ∼24 h.

AbfR harbors two cysteine residues at amino acid positions 13 and 116. To investigate the contributions of these two residues to the regulatory function of AbfR, EMSA was performed with the purified AbfR protein, AbfRC13S protein, and AbfRC116S protein, respectively (Fig. 4C). All three proteins completely bound to DNA1 with a 10:1 molar ratio of protein to DNA. The DNA binding activity of wild-type AbfR was significantly reduced in the presence of 5 μm CHP, whereas the addition of 5 μm CHP did not affect the DNA binding activity of either AbfRC13S or AbfRC116S. These results indicate that Cys-13 and Cys-116 are likely required for AbfR to sense and respond to oxidants such as CHP. We also observed that addition of a 20 μm CHP to the binding reaction could reduce the DNA binding activity of AbfRC116S, although the DNA binding activity of AbfRC13S is not affected even by the presence of 40 μm CHP.

To determine the function of cysteine residues in their reduced and oxidized form, a DTNB titration assay was used to find the content of free thiol in reduced and oxidized wild-type AbfR (Fig. 4D). The thiol content of the wild-type AbfR in reduced and oxidized forms was 1.71 ± 0.11 and 0.15 ± 0.02 per subunit, respectively. Thus, the reduced AbfR likely has two free thiol groups, whereas oxidized AbfR has no free sulfhydryl group. In addition, the reduced and oxidized forms of AbfRC13S gave similar values for their thiol content, at approximately one free sulfhydryl group/subunit, indicating that the CHP treatment had no effect on the Cys-116 residues in the absence of Cys-13. In contrast, the thiol content of reduced and oxidized AbfRC116S was 0.83 ± 0.04 and 0.16 ± 0.02 per subunit, respectively. These results clearly suggest that Cys-13 plays a key role in CHP-mediated oxidation of AbfR.

We further introduced pYJ335::abfRC13S andpYJ335::abfRC116S into the abfR mutant strain and performed qRT-PCR to examine the transcripts of SERP2195 and gpxA-2, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4E, CHP stress dramatically induced (>30-fold) the expression of both SERP2195 and gpxA-2 in the complemented wild-type strain (ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR). However, a less significant increase of the mRNA level of SERP2195 or gpxA-2 was observed in the ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfRC13S strain treated with CHP compared with untreated bacteria. In addition, increases of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 transcription (∼6-fold) were also observed in the ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfRC116S strain treated with CHP, but to a far lesser extent when compared with those (>30-fold) of the ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR treated with CHP. Further, we observed that the ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfRC13S and ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfRC116S strains are ∼100-fold more sensitive to CHP stress than the parent ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR strain (Fig. 4F). Again, these results clearly indicate that both Cys-13 and Cys-116 of AbfR play important roles in sensing and responding to oxidative stress in S. epidermidis.

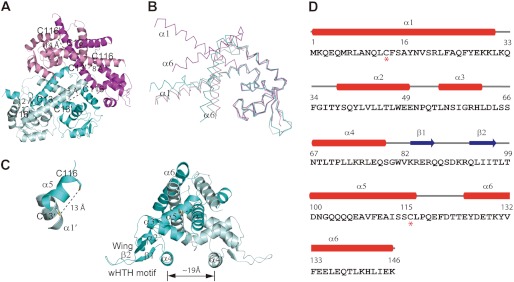

Crystal Structure of the Reduced AbfR Protein

The AbfR protein in reduced form was crystallized in space group C2 (Table 1). The structure was solved by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion from a selenomethionine-substituted crystal form and refined at 2.5 Å resolution. Four AbfR monomers assembled as a dimeric dimer in each asymmetric unit (Fig. 5A). Superimpositions of the four monomers in the asymmetric unit revealed conformational flexibility of the AbfR protein in a DNA-free state, in particular, the orientations of the dimerization motif, such as α1 and α6 (Fig. 5B). The overall folding of the AbfR homodimer resembled other known structures of the MarR family proteins that share a triangular shape (Fig. 5, C and D) (16–19, 45–49). The top half of the dimer contains helices α1, α5, and α6 to form the dimerization domain, and the bottom half includes helices α3 and α4, thereby forming a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain. Between helices α4 and α5, the wing motif comprised two antiparallel β-strands and their connecting loops. These loops were well positioned in one dimer but disordered in the other dimer and could not be built (Fig. 5, A and C). A close examination of the structure also showed that the intersubunit proximity of Cys-13′ from one monomer and Cys-116 from the other is located between 8 and 14 Å: close enough to potentially form a disulfide bond. Overall, these structural features indicate that AbfR might respond to an oxidative signal. AbfR might alter its DNA binding affinity through changes in dimerization domain conformations. It might also reorient its DNA binding helices through switches of the intersubunit disulfide bonds (17, 18, 49, 50).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| SeMet-AbfR | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 127.78, 50.62, 107.45 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 110.4, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–2.50 (2.59–2.50)c |

| No. of observations | 142190 (7434) |

| No. unique | 21526 (1770) |

| Rsyma | 0.103 (0.477) |

| I/σ(I) | 20.2 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.4 (79.8) |

| Redundancy | 6.6 (4.2) |

| Data refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.0–2.50 (2.57–2.50) |

| No. reflections | 20399 (1127) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 21.0/25.9 |

| Root mean square deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.516 |

| Ramachandran plotb | |

| Most favored (%) | 97.7 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.3 |

a Rsym = Σ|(I − <I>)|/Σ(I), where I is the observed intensity.

b The values were calculated in CCP4 suite using Procheck.

c The highest resolution shell is shown in parentheses.

FIGURE 5.

Crystal structure of the reduced AbfR. A, crystal structure of AbfR in a dimeric dimmer is shown in cartoon. Two dimers existed in one asymmetric unit, in which one dimer is shown in magenta and pink and the other is shown in cyan and pale cyan. The distances between the intersubunit pairs Cys-13(′) and Cys-116(′) are shown, respectively. B, superimposition of the four monomers observed in A. The large conformational variation came from the dimerization motifs α1 and α6. C, one AbfR dimer is presented in cartoon. The secondary structural elements are shown (α, α-helices; β, β-sheets; wHTH motif, the helix-turn-helix wing region, β1-loop-β2). The distance between two α4 helices is ∼19 Å (defined as Cα of Asn-67). The distance between Cys-13 and Cys-116′ is 13 Å; these residues are favored for disulfide bond formation. D, secondary structure assignment of AbfR is shown. The residue numbers are shown on top of the sequence of AbfR, with the two Cys residues marked below with an asterisk. The secondary structural elements of the AbfR crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 4HBL) are shown as red tubes for α-helices and blue arrows for β-sheets, respectively.

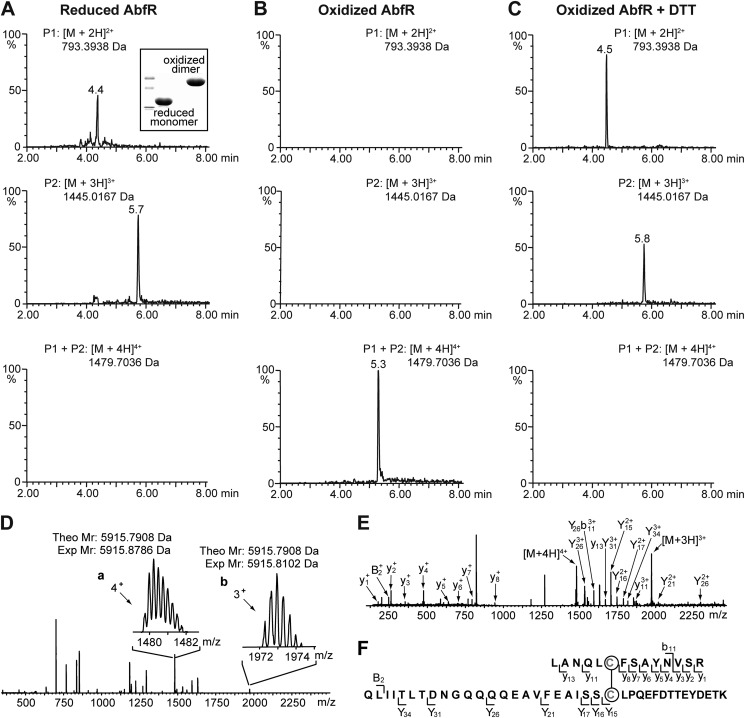

Characterization of Disulfide Bond Formation in the Oxidized AbfR

To determine the intersubunit disulfide bond formation in AbfR after oxidation, we prepared a reduced and an oxidized form of AbfR and performed mass spectroscopic mapping characterization as previous reported (49, 51). Nonreducing SDS-PAGE analyses confirmed the qualities (Fig. 6A). In the full scan mass spectrum of the oxidized AbfR sample, evident quadruply (m/z 1479) and triply (m/z 1972) charged peaks corresponding to the disulfide-containing peptide of interest (cross-link between Cys-13 and Cys-116′; theoretically molecular mass, 5,915.8102 Da) were observed (Fig. 6, B and D). In a control experiment, this species could not be captured in the reduced AbfR sample (Fig. 6A). In addition, this species was lost if the oxidized sample, which has been shown to contain this species, was reduced in the presence of DTT (5 mm) (Fig. 6C). Further MSE fragmentation (52) of this peptide generated a variety of cross-linked fragment ions, including y11, Y15, Y16, Y17, Y21, Y26, Y34, Y26b11, and y13Y31, suggesting the presence of a disulfide bond between Cys-13 and Cys-116′ (Fig. 6, E and F). Moreover, we failed to detect the intersubunit “homo-cross-link” between Cys-13 and Cys-13′ or Cys-116 and Cys-116′ in this MS characterization. Overall, these mass spectrometric analyses provide strong evidence that the intersubunit disulfide bond was formed between Cys-13 and Cys-116′ under oxidative stress.

FIGURE 6.

Characterization of disulfide bond formation in the oxidized AbfR. A–C, ultra performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization quadrupole-TOF mass spectrometric analysis extracted ion chromatograms of reduced AbfR (A), the oxidized AbfR (B), and the oxidized AbfR (C) treated with DTT after trypsin digestion. P1 indicates LANQLCFSAYNVSR, P2 indicates QLIITLTDNGQQQQEAVFEAISSCLPQEFDTTEYDETK, and P1 + P2 indicates cross-linked peptide between P1 and P2 through a disulfide bond. Nonreducing SDS-PAGE analyses of the reduced and oxidized AbfR samples are shown. D, electrospray ionization quadrupole-TOF mass spectrometric analysis mass spectrum of an unfractionated tryptic digestion. The quadruply charged (m/z 1478–1484) and triply charged (m/z 1970–1976) peaks, which are corresponding to the target disulfide-containing peptide (Theo Mr, theoretical mass: 5,915.7908 Da) are shown in a and b, respectively. Exp Mr, experimental mass. E, spectrum of the MSE fragmentation of the disulfide-containing peptide is shown. Y, y, B, b are types of ions. F, graphical fragment map that correlates the fragmentation ions to the peptide sequence. The disulfide-linked cysteines are shown in red and circled.

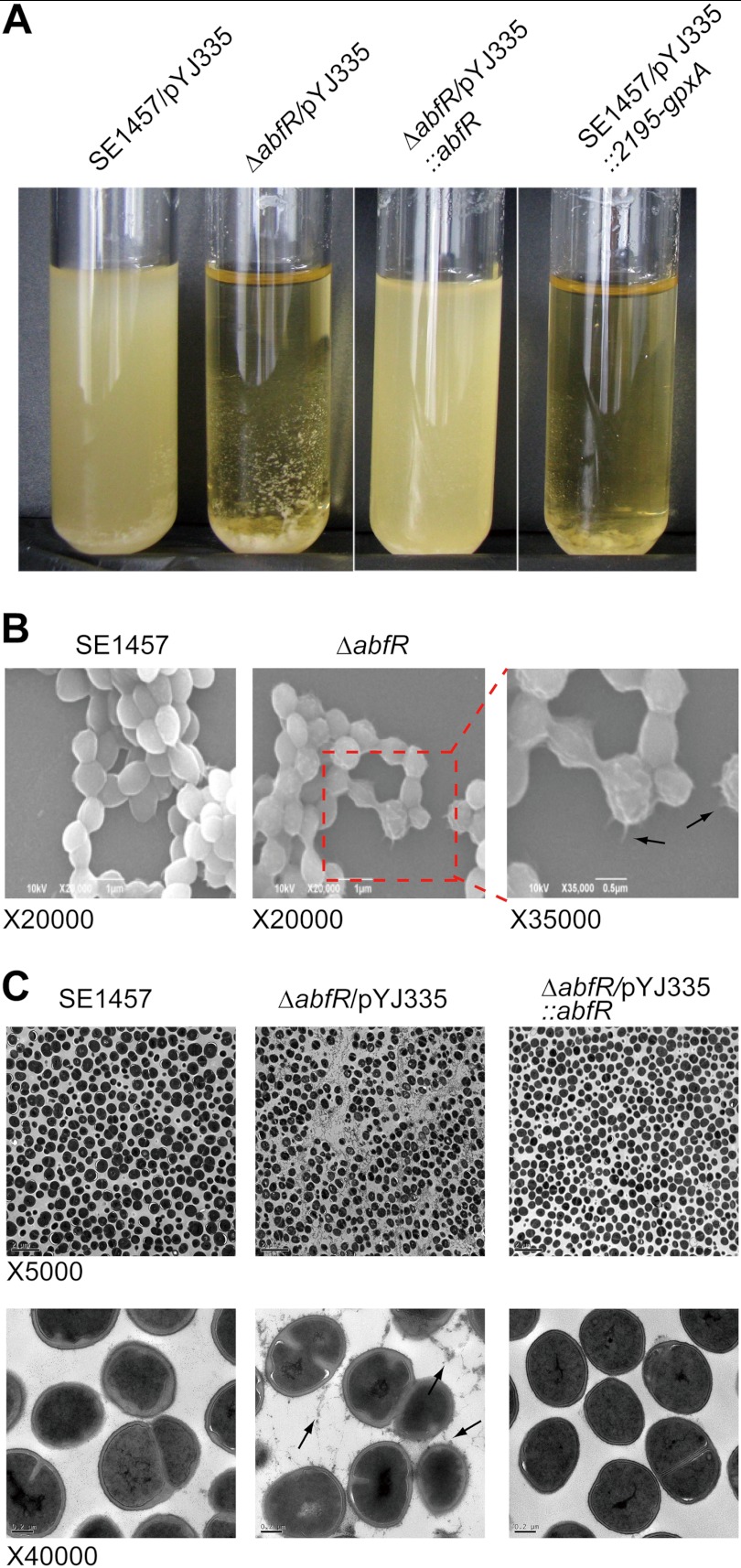

AbfR Affects Cell Intercellular Aggregation in S. epidermidis

Deletion of abfR results in enhanced bacterial aggregation when bacteria were grown in TSB medium. As shown in Fig. 7A, macroscopic aggregates of ΔabfR strain in liquid cultures settled to the bottom of the test tube. This phenotype could be restored by complementation of the ΔabfR mutant with the abfR gene. In addition, constitutive expression of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 also caused aggregation of wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, we investigated the morphology of ΔabfR mutant and wild-type cells by using SEM. As shown in Fig. 7B, ΔabfR cells displayed more extracellular matrix compared with wild-type S. epidermidis 1457. Transmission EM of wild-type and the abfR knock-out strains was also performed to confirm features observed in the SEM. The wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 showed a smooth surface without fuzzy appendages (Fig. 7C), whereas ΔabfR strain exhibited tuft-like surface material and extracellular polymeric substances that were especially prominent between adjacent cells (Fig. 7C). This phenotype of the mutant cells could be restored by abfR gene complementation, because the pYJ335::abfR strain exhibited a smooth surface similar to that observed in the wild-type strain (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Phenotypes of S. epidermidis strains. A, bacterial aggregation of SE1457/pYJ335, ΔabfR/pYJ335, ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR, and SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA. The strains were grown in TSB at 37 °C for 12 h. ΔabfR/pYJ335 and SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA cultures formed macroscopic aggregates that rapidly settled at the bottom of the test tubes. B, SEM images of SE1457 and ΔabfR are shown. It is presented at magnifications of ×20,000 and ×35,000, respectively. Arrows show the extracellular polymeric substances. C, transmission EM images of SE1457 and variants. Planktonic cells of SE1457, ΔabfR, and ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR cultured for 16 h were examined by transmission EM. The images are displayed at magnification of ×5000 (top panels) and ×40,000 (bottom panels). Arrows show tuft-like surface material and extracellular polymeric substances between adjacent cells.

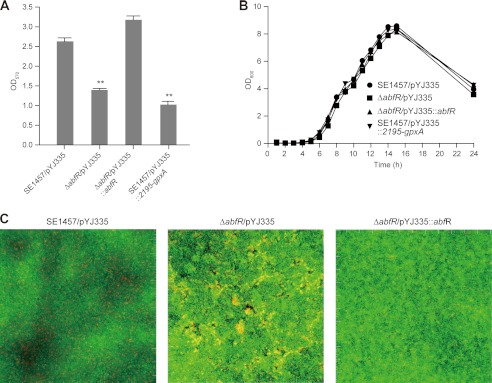

Role of AbfR in Biofilm Formation

To examine whether AbfR modulates biofilm formation in S. epidermidis, we performed a semiquantitative adherence assay as previously described (39, 40, 42). As shown in Fig. 8A, the ΔabfR mutant strain exhibited significantly decreased biofilm formation (A570 = 1.4 ± 0.04), compared with its wild-type counterpart (A570 = 2.7 ± 0.1). Complementation of abfR gene fully restored the ability of biofilm formation of the ΔabfR mutant strain (A570 = 3.2 ± 0.1) to that of the wild-type S. epidermidis 1457. Furthermore, constitutive expression of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 in the wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 (SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA) resulted in decreased biofilm formation (A570 = 1.0 ± 0.1) (Fig. 8A). These observations of decreased biofilm formation in ΔabfR and SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA strains were not a result of the differences in bacterial growth, because all of the strains showed similar growth rates in BM medium (Fig. 8B). We further monitored the three-dimensional biofilm formation through the use of confocal laser scanning microscopy. More dead cells were observed in the ΔabfR mutant biofilm compared with that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 8C), indicating that abfR plays a regulatory role in biofilm development in S. epidermidis.

FIGURE 8.

Effect of abfR deletion on biofilm formation. A, biofilm formation of SE1457/pYJ335, ΔabfR/pYJ335, ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR, and SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA are presented. The experiments were replicated four times, and similar results were obtained. The data are the means of 12 microtiter plate wells. Student's t test reveals significance. **, p value < 0.01. B, shown is the growth curve of SE1457/pYJ335, ΔabfR/pYJ335, ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR, and SE1457/pYJ335::2195-gpxA. C, confocal laser scanning microscopy shows biofilm of S. epidermidis. Strains of SE1457, ΔabfR, and ΔabfR/pYJ335::abfR were incubated in glass-bottomed cell culture dishes. The results depict a stack of images taken at ∼0.3-μm-deep increments, and one of the three experiments is presented.

DISCUSSION

Oxidation-sensing regulators have been extensively studied in pathogenic bacteria, including S. aureus (19, 22, 51, 53, 54), Enterococcus faecium (55), E. coli (56–60), P. aeruginosa (20, 21), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (61). Several redox-sensitive regulatory proteins act as major regulators of bacteria adaptability to oxidative stress or antibiotic stress and impact bacterial virulence (19–22, 55). Redox regulation involving reactive oxygen species is now recognized as a critical component of bacterial signaling and regulation (26, 62). However, the mechanism by which S. epidermidis senses and responds to oxidative stress remains largely unknown. Here, we have examined the abfR gene, which encodes a functional homologue of the OspR/MgrA proteins and which serves as an oxidation-sensing regulator in S. epidermidis (Figs. 1 and 2). To our knowledge, this is the first thiol-based redox-switching sensor identified in S. epidermidis.

AbfR belongs to the two-cysteine protein family that senses peroxides. Similar to P. aeruginosa OspR (21) and Xanthomonas campestris OhrR (16, 17), AbfR harbors two cysteine residues, Cys-13 and Cys-116, to sense and respond to oxidants such as H2O2 and CHP (Fig. 4). It is likely that AbfR directly senses peroxides by Cys-13 and forms an intersubunit disulfide bond between Cys-13 and Cys-116′ subsequently, resulting in the dissociation of AbfR from promoter DNA (Figs. 5 and 6).

Negatively autoregulated, AbfR binds to its own promoter and represses the expression of the abfR-SERP2195-gpxA operon (Fig. 3). In addition, AbfR plays a key role in adapting to oxidative stress, autoaggregation, and biofilm formation in S. epidermidis (Figs. 7 and 8). Thus, AbfR regulation is not restricted to oxidative stress response but extends to the modulation of bacterial virulence properties, which includes the autoaggregation of bacterial and biofilm formation, suggesting that oxidative stress may act as a signal to modulate virulence properties of S. epidermidis during infection.

We provide evidence that the derepression of SERP2195 and gpxA-2 mediate the effects of AbfR on bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation (Figs. 7 and 8). Indeed, cell surface structures often mediate biofilm formation and bacterial aggregation (63–65), whereas either the SERP2195 or gpxA-2 gene encode the putative enzyme involved in glutathione metabolism. It is tempting to suppose that the intercellular redox state of S. epidermidis might modulate bacteria cell surface structures and thus lead to the altered ability of autoaggregation of S. epidermidis. The relationship between the redox state of S. epidermidis and bacterial aggregation remains to be demonstrated, and further studies are therefore necessary.

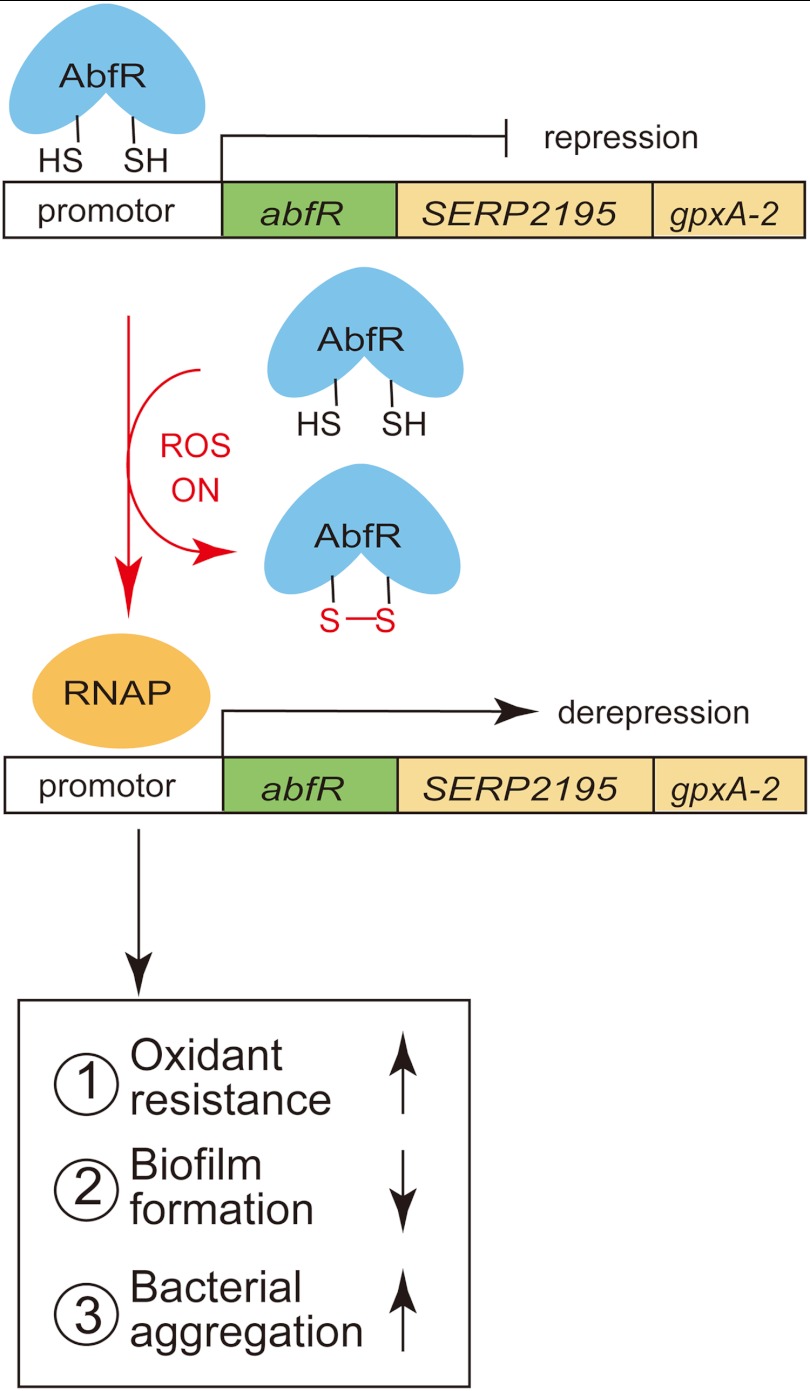

In summary, AbfR plays key roles in responses to oxidative stress, bacterial aggregation, and biofilm formation in S. epidermidis, which is summarized in a model (Fig. 9). Oxidative stress inactivates AbfR, which acts as a repressor of abfR-SERP2195-gpxA operon. It has been shown that mild oxidative stress down-regulates S. epidermidis biofilm development (5, 6, 66). Similarly, we may speculate that oxidative stress acts as a signal to modulate S. epidermidis key virulence properties through AbfR.

FIGURE 9.

A proposed model of AbfR-based sensing and regulation of oxidative stress in S. epidermidis. Upon oxidative stress, AbfR senses reactive oxygen species (ROS) signals through the formation of the intersubunit disulfide bond and then dissociates from promoter DNA, which leads to derepression of the abfR-SERP2195-gpxA-2 operon. Consequently, the derepression of the SERP2195-gpxA-2 results in the reduced susceptibility to oxidant stress, decreased biofilm formation, and enhanced bacterial aggregation in S. epidermidis. RNAP, RNA polymerase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank user support at Beamline BL17U at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility and S.F. Reichard for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 90913010, 21172234, 20972173, and 81271791; the Hundred Talent Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences; National Science and Technology Key New Drug Creation and Manufacturing Program Major Project Grant 2013ZX09507-004; and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province Grant BK2010358.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4HBL) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- TSB

- tryptic soy broth

- CHP

- cumene hydroperoxide

- SEM

- scanning EM

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real time RT-PCR

- DTNB

- 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Uçkay I., Pittet D., Vaudaux P., Sax H., Lew D., Waldvogel F. (2009) Foreign body infections due to Staphylococcus epidermidis. Ann. Med. 41, 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Götz F. (2002) Staphylococcus and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1367–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Otto M. (2013) Staphylococcal infections. Mechanisms of biofilm maturation and detachment as critical determinants of pathogenicity. Annu. Rev. Med. 64, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Imlay J. A. (2008) Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 755–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schlag S., Nerz C., Birkenstock T. A., Altenberend F., Götz F. (2007) Inhibition of staphylococcal biofilm formation by nitrite. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7911–7919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glynn A. A., O'Donnell S. T., Molony D. C., Sheehan E., McCormack D. J., O'Gara J. P. (2009) Hydrogen peroxide induced repression of icaADBC transcription and biofilm development in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Orthop. Res. 27, 627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Antelmann H., Helmann J. D. (2011) Thiol-based redox switches and gene regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1049–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zuber P. (2009) Management of oxidative stress in Bacillus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 575–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duarte V., Latour J. M. (2010) PerR vs OhrR. Selective peroxide sensing in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Biosyst. 6, 316–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dubbs J. M., Mongkolsuk S. (2012) Peroxide-sensing transcriptional regulators in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 194, 5495–5503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perera I. C., Grove A. (2010) Molecular mechanisms of ligand-mediated attenuation of DNA binding by MarR family transcriptional regulators. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 243–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fuangthong M., Helmann J. D. (2002) The OhrR repressor senses organic hydroperoxides by reversible formation of a cysteine-sulfenic acid derivative. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6690–6695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee J. W., Soonsanga S., Helmann J. D. (2007) A complex thiolate switch regulates the Bacillus subtilis organic peroxide sensor OhrR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8743–8748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sukchawalit R., Loprasert S., Atichartpongkul S., Mongkolsuk S. (2001) Complex regulation of the organic hydroperoxide resistance gene (ohr) from Xanthomonas involves OhrR, a novel organic peroxide-inducible negative regulator, and posttranscriptional modifications. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4405–4412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Atichartpongkul S., Fuangthong M., Vattanaviboon P., Mongkolsuk S. (2010) Analyses of the regulatory mechanism and physiological roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa OhrR, a transcription regulator and a sensor of organic hydroperoxides. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2093–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hong M., Fuangthong M., Helmann J. D., Brennan R. G. (2005) Structure of an OhrR-ohrA operator complex reveals the DNA binding mechanism of the MarR family. Mol. Cell 20, 131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Newberry K. J., Fuangthong M., Panmanee W., Mongkolsuk S., Brennan R. G. (2007) Structural mechanism of organic hydroperoxide induction of the transcription regulator OhrR. Mol. Cell 28, 652–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilkinson S. P., Grove A. (2006) Ligand-responsive transcriptional regulation by members of the MarR family of winged helix proteins. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 8, 51–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen P. R., Bae T., Williams W. A., Duguid E. M., Rice P. A., Schneewind O., He C. (2006) An oxidation-sensing mechanism is used by the global regulator MgrA in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 591–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen H., Hu J., Chen P. R., Lan L., Li Z., Hicks L. M., Dinner A. R., He C. (2008) The Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug efflux regulator MexR uses an oxidation-sensing mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13586–13591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lan L., Murray T. S., Kazmierczak B. I., He C. (2010) Pseudomonas aeruginosa OspR is an oxidative stress sensing regulator that affects pigment production, antibiotic resistance and dissemination during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 76–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen P. R., Nishida S., Poor C. B., Cheng A., Bae T., Kuechenmeister L., Dunman P. M., Missiakas D., He C. (2009) A new oxidative sensing and regulation pathway mediated by the MgrA homologue SarZ in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 198–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aoki R., Takeda T., Omata T., Ihara K., Fujita Y. (2012) MarR-type transcriptional regulator ChlR activates expression of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis genes in response to low-oxygen conditions in cyanobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13500–13507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luong T. T., Newell S. W., Lee C. Y. (2003) Mgr, a novel global regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 185, 3703–3710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ballal A., Manna A. C. (2010) Control of thioredoxin reductase gene (trxB) transcription by SarA in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 192, 336–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vázquez-Torres A. (2012) Redox active thiol sensors of oxidative and nitrosative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 1201–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bae T., Schneewind O. (2006) Allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus with inducible counter-selection. Plasmid 55, 58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun F., Ding Y., Ji Q., Liang Z., Deng X., Wong C. C., Yi C., Zhang L., Xie S., Alvarez S., Hicks L. M., Luo C., Jiang H., Lan L., He C. (2012) Protein cysteine phosphorylation of SarA/MgrA family transcriptional regulators mediates bacterial virulence and antibiotic resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15461–15466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ji Y., Marra A., Rosenberg M., Woodnutt G. (1999) Regulated antisense RNA eliminates alpha-toxin virulence in Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Bacteriol. 181, 6585–6590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Donnelly M. I., Zhou M., Millard C. S., Clancy S., Stols L., Eschenfeldt W. H., Collart F. R., Joachimiak A. (2006) An expression vector tailored for large-scale, high-throughput purification of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 47, 446–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doublié S. (1997) Preparation of selenomethionyl proteins for phase determination. Methods Enzymol. 276, 523–530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zianni M., Tessanne K., Merighi M., Laguna R., Tabita F. R. (2006) Identification of the DNA bases of a DNase I footprint by the use of dye primer sequencing on an automated capillary DNA analysis instrument. J. Biomol. Tech. 17, 103–113 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode, pp. 307–326, Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., New York: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite. Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sheldrick G. M. (2010) Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E. Combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) COOT. Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrodinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 39. Christensen G. D., Baddour L. M., Madison B. M., Parisi J. T., Abraham S. N., Hasty D. L., Lowrance J. H., Josephs J. A., Simpson W. A. (1990) Colonial morphology of staphylococci on Memphis agar. Phase variation of slime production, resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, and virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 161, 1153–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lou Q., Zhu T., Hu J., Ben H., Yang J., Yu F., Liu J., Wu Y., Fischer A., Francois P., Schrenzel J., Qu D. (2011) Role of the SaeRS two-component regulatory system in Staphylococcus epidermidis autolysis and biofilm formation. BMC Microbiol. 11, 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qin Z., Yang X., Yang L., Jiang J., Ou Y., Molin S., Qu D. (2007) Formation and properties of in vitro biofilms of ica-negative Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 56, 83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang R. Z., Zheng L. K., Liu H. Y., Pan B., Hu J., Zhu T., Wang W., Jiang D. B., Wu Y., Wu Y. C., Han S. Q., Qu D. (2012) Thiazolidione derivatives targeting the histidine kinase YycG are effective against both planktonic and biofilm-associated Staphylococcus epidermidis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 33, 418–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. (2005) Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. A target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 360, 2335–2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moore T. D., Sparling P. F. (1996) Interruption of the gpxA gene increases the sensitivity of Neisseria meningitidis to paraquat. J. Bacteriol. 178, 4301–4305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alekshun M. N., Levy S. B., Mealy T. R., Seaton B. A., Head J. F. (2001) The crystal structure of MarR, a regulator of multiple antibiotic resistance, at 2.3 A resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 710–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Poor C. B., Chen P. R., Duguid E., Rice P. A., He C. (2009) Crystal structures of the reduced, sulfenic acid, and mixed disulfide forms of SarZ, a redox active global regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23517–23524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dolan K. T., Duguid E. M., He C. (2011) Crystal structures of SlyA protein, a master virulence regulator of Salmonella, in free and DNA-bound states. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22178–22185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu R. Y., Zhang R. G., Zagnitko O., Dementieva I., Maltzev N., Watson J. D., Laskowski R., Gornicki P., Joachimiak A. (2003) Crystal structure of Enterococcus faecalis SlyA-like transcriptional factor. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20240–20244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Palm G. J., Khanh Chi B., Waack P., Gronau K., Becher D., Albrecht D., Hinrichs W., Read R. J., Antelmann H. (2012) Structural insights into the redox-switch mechanism of the MarR/DUF24-type regulator HypR. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 4178–4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen H., Yi C., Zhang J., Zhang W., Ge Z., Yang C. G., He C. (2010) Structural insight into the oxidation-sensing mechanism of the antibiotic resistance of regulator MexR. EMBO Rep. 11, 685–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sun F., Liang H., Kong X., Xie S., Cho H., Deng X., Ji Q., Zhang H., Alvarez S., Hicks L. M., Bae T., Luo C., Jiang H., He C. (2012) Quorum-sensing agr mediates bacterial oxidation response via an intramolecular disulfide redox switch in the response regulator AgrA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 9095–9100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Plumb R. S., Johnson K. A., Rainville P., Smith B. W., Wilson I. D., Castro-Perez J. M., Nicholson J. K. (2006) UPLC/MS(E). A new approach for generating molecular fragment information for biomarker structure elucidation. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 20, 1989–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ingavale S., van Wamel W., Luong T. T., Lee C. Y., Cheung A. L. (2005) Rat/MgrA, a regulator of autolysis, is a regulator of virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 73, 1423–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ji Q., Zhang L., Sun F., Deng X., Liang H., Bae T., He C. (2012) Staphylococcus aureus CymR is a new thiol-based oxidation-sensing regulator of stress resistance and oxidative response. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 21102–21109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lebreton F., van Schaik W., Sanguinetti M., Posteraro B., Torelli R., Le Bras F., Verneuil N., Zhang X., Giard J. C., Dhalluin A., Willems R. J., Leclercq R., Cattoir V. (2012) AsrR is an oxidative stress sensing regulator modulating Enterococcus faecium opportunistic traits, antimicrobial resistance, and pathogenicity. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pomposiello P. J., Bennik M. H., Demple B. (2001) Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J. Bacteriol. 183, 3890–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Choi H., Kim S., Mukhopadhyay P., Cho S., Woo J., Storz G., Ryu S. E. (2001) Structural basis of the redox switch in the OxyR transcription factor. Cell 105, 103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zheng M., Aslund F., Storz G. (1998) Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science 279, 1718–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kim S. O., Merchant K., Nudelman R., Beyer W. F., Jr., Keng T., DeAngelo J., Hausladen A., Stamler J. S. (2002) OxyR. A molecular code for redox-related signaling. Cell 109, 383–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee C., Lee S. M., Mukhopadhyay P., Kim S. J., Lee S. C., Ahn W. S., Yu M. H., Storz G., Ryu S. E. (2004) Redox regulation of OxyR requires specific disulfide bond formation involving a rapid kinetic reaction path. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 1179–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brugarolas P., Movahedzadeh F., Wang Y., Zhang N., Bartek I. L., Gao Y. N., Voskuil M. I., Franzblau S. G., He C. (2012) The oxidation-sensing regulator (MosR) is a new redox dependent transcription factor in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 37703–37712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dwyer D. J., Kohanski M. A., Collins J. J. (2009) Role of reactive oxygen species in antibiotic action and resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 482–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vergara-Irigaray M., Maira-Litrán T., Merino N., Pier G. B., Penadés J. R., Lasa I. (2008) Wall teichoic acids are dispensable for anchoring the PNAG exopolysaccharide to the Staphylococcus aureus cell surface. Microbiology 154, 865–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Holland L. M., Conlon B., O'Gara J. P. (2011) Mutation of tagO reveals an essential role for wall teichoic acids in Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm development. Microbiology 157, 408–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fey P. D., Olson M. E. (2010) Current concepts in biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Future Microbiol. 5, 917–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Aiassa V., Barnes A. I., Albesa I. (2012) In vitro oxidant effects of d-glucosamine reduce adhesion and biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Rev. Argent Microbiol. 44, 16–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T. J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., Soding J., Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.