Abstract

Mutations in the serine-threonine kinase WNK4 [with no lysine (K) 4] cause pseudohypoaldosteronism type II, a Mendelian disease featuring hypertension with hyperkalemia. In the kidney, WNK4 regulates the balance between NaCl reabsorption and K+ secretion via variable inhibition of the thiazide-sensistive NaCl cotransporter and the K+ channel ROMK. We now demonstrate expression of WNK4 mRNA and protein outside the kidney. In extrarenal tissues, WNK4 is found almost exclusively in polarized epithelia, variably associating with tight junctions, lateral membranes, and cytoplasm. Epithelia expressing WNK4 include sweat ducts, colonic crypts, pancreatic ducts, bile ducts, and epididymis. WNK4 is also expressed in the specialized endothelium of the blood–brain barrier. These epithelia and endothelium all play important roles in Cl– transport. Because WNK4 is known to regulate renal Cl– handling, we tested WNK4's effect on the activity of mediators of epithelial Cl– flux whose extrarenal expression overlaps with WNK4. WNK4 proved to be a potent inhibitor of the activity of both the Na+-K+-2Cl– cotransporter (NKCC1) and the Cl–/base exchanger SLC26A6 (CFEX) (>95% inhibition of NKCC1-mediated 86Rb influx, P < 0.001; >80% inhibition of CFEX-mediated [14C] formate uptake, P < 0.001), mediators of Cl– flux across basolateral and apical membranes, respectively. In contrast, WNK4 showed no inhibition of pendrin, a related Cl–/base exchanger. These findings indicate a general role for WNK4 in the regulation of electrolyte flux in diverse epithelia. Moreover, they reveal that WNK4 regulates the activities of a diverse group of structurally unrelated ion channels, cotransporters, and exchangers.

Polarized epithelia regulate the transepithelial flux of electrolytes and solutes, thereby maintaining the proper ionic composition and volume of different fluid compartments (1). Among these, Cl– is the most abundant biological anion and the predominant permeating anionic species in all organisms. Transepithelial Cl– flux can occur by either transcellular or paracellular routes. Cl– channels, cotransporters, and exchangers mediate transcellular movement across both apical and basolateral membranes; paracellular pathways allow selective Cl– flux across tight junctions (TJs) (1). The proper regulation of transepithelial Cl– transport is required for a wide variety of physiologic functions including the regulation of intravascular volume and blood pressure, clearance of lung water, and establishment of intralumenal flow required for the passage of bile acids, exocrine pancreatic enzymes, sweat, and semen via their respective ducts.

We have recently identified a pathway that regulates renal Cl– flux. By positional cloning, we demonstrated that mutations in the serine-threonine kinases WNK1 [with no lysine (K) 1] and WNK4 result in increased renal Cl– reabsorption and impaired K+ secretion, manifesting as the inherited syndrome of hypertension and hyperkalemia, pseudohypoaldosteronism type II (PHAII; ref. 2). WNK1 and WNK4 are most highly expressed in the kidney, localizing exclusively to the distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct (CD) (2). By expression studies in vitro, it has been shown that WT WNK4 inhibits the activity of both the NaCl cotransporter NCCT (3, 4) and the K+ channel ROMK (5) by reducing the surface expression of each. Intriguingly, missense mutations in WNK4 that cause PHAII relieve WNK4's inhibition of NCCT (3), resulting in increased NaCl reabsorption, while concomitantly increasing inhibition of ROMK (5), accounting for impaired K+ secretion. These observations establish WNK4 as a molecular switch, capable of altering the balance between renal salt reabsorption and K+ secretion (5).

We have recently shown that WNK1 expression is not limited to the kidney (6). WNK1 is selectively found in other Cl–-transporting epithelia such as pancreatic ducts, biliary ducts, sweat ducts, colonic crypts, and epididymis (6). These observations suggest a broader role for members of this kinase family as regulators of ion flux, although the specific molecular targets that might be regulated by WNK kinases in these tissues are unknown. Importantly, the known targets, NCCT and ROMK, are not present in these extrarenal epithelia. Although Northern blotting of WNK4 in humans has shown expression only in the kidney (2), these studies do not preclude lower levels of expression in other tissues. In this study, we demonstrate significant expression of WNK4 in a wide range of epithelia that mediate Cl– flux; we also show that two mediators of transcellular Cl– flux expressed in these tissues are regulated by WNK4. These findings implicate WNK4 in the regulation of Cl– flux in diverse epithelia.

Methods

RT-PCR Analysis. A mouse multiple tissue cDNA panel (Clontech) was used to evaluate WNK4 transcript expression in mouse tissues. PCR was performed by using primers specific for WNK4 from exons 9 and 11 (primer 1, 5′-TGCCTTGTCTATTCCACGGTCTG-3′; primer 2, 5′-CAGCTGCAATTTCTTCTGGGCTG-3′); PCR yields a fragment of 280 bp from spliced WNK4 mRNA whose identity was verified by DNA sequencing. Primers for mouse GAPDH were used to control for the efficiency of PCR.

Antibodies. A rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for WNK4 was obtained from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Other antibodies include rat monoclonal anti-zona occludens-1 (ZO-1; gift of James Anderson, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), rat anti-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-Na+-K+-2Cl– cotransporter (NKCC1) T4 (7), and mouse anti-NKCC1 T9 (7). Affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit, rat, or mouse secondary antibodies were conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Zymed) or the CY2 or CY3 fluors (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Western Blot Analysis of WNK4. Homogenized mouse or human tissue lysates (Clontech) were fractionated on 4–15% polyacrylamide gradient gels by SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were blocked, incubated with anti-WNK4 at 1:500, washed, and incubated with anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. Filters were washed, and chemiluminesence was performed by using ECL+ (Amersham Pharmacia).

Immunolocalization Studies. Selected mouse or human tissues were used to study the immunolocalization of WNK4. Male mice were killed by cervical dislocation at age 10–12 weeks. Tissue was embedded in OCT and snap-frozen in isopentane at –140°C. Frozen normal human skin and colon blocks were obtained from Research Histology in the Yale Department of Pathology. Sections of 5 μm were used for immunolocalization. Studies were approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee and the Yale Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue sections were processed and incubated with rabbit anti-WNK4 (1:400) and rat anti-ZO-1 (1:100) or rat anti-CFTR (1:200) and secondary antibodies (6). Stained sections were visualized by immunofluorescence light microscopy. Results displayed are representative of results from at least four different mice or two different humans.

All immunostaining with anti-WNK4 was competed with a 3-fold molar excess of the immunizing peptide, and staining with secondary antibody alone revealed no signal.

Functional Studies in Xenopus Oocytes. Plasmids used for expression studies encoded hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged mouse WNK4 cDNA (pcDNA3.1-WNK4-HA) (3), human NKCC1 cDNA (pol1-NKCC1) (8); mouse Cl–/base exchanger SLC26A6 (CFEX) cDNA (pGH19-CFEX) (9); and human pendrin cDNA (pGEMHE-pendrin, provided by Lawrence Karniski, University of Iowa, Iowa City) (10). Plasmids were linearized by restriction enzyme digestion, and cRNA was transcribed by using T7 RNA polymerase (mMessage-mMachine kit, Ambion). cRNA quality was assessed with UV spectrometry and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Stage IV-VI Xenopus laevis oocytes were harvested and defolliculated (3) in conformity with institutional regulations. Oocytes were injected with 25 ng of each indicated cRNA in 50 nl.

NKCC1 studies. Oocytes were injected with NKCC1 cRNA ± WNK4 cRNA and incubated for 3 days at 17°C in ND96 medium (3) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin. Oocytes were equilibrated to room temperature, washed in basic flux solution, and transferred to uptake medium (78 mM Na+/83 mM Cl–/2 mM K+/1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mg2+/1 mM  Hepes/0.1 mM ouabain, pH 7.4) containing 20 μCi 86Rb/ml; oocytes were incubated for 30 min at room temperature (under these conditions, 95–99% of the 86Rb uptake is bumetanide sensitive) (8). Uptake was terminated by washing oocytes in ice-cold flux medium containing 250 μM bumetanide, and uptake was measured by lysing the oocytes in 10% SDS and β-scintillation counting of individual oocytes. Water-injected oocytes served as controls. In each experiment, at least eight oocytes were tested in each group; results were highly reproducible across three independent experiments.

Hepes/0.1 mM ouabain, pH 7.4) containing 20 μCi 86Rb/ml; oocytes were incubated for 30 min at room temperature (under these conditions, 95–99% of the 86Rb uptake is bumetanide sensitive) (8). Uptake was terminated by washing oocytes in ice-cold flux medium containing 250 μM bumetanide, and uptake was measured by lysing the oocytes in 10% SDS and β-scintillation counting of individual oocytes. Water-injected oocytes served as controls. In each experiment, at least eight oocytes were tested in each group; results were highly reproducible across three independent experiments.

CFEX and pendrin studies. Oocytes were injected with cRNAs encoding CFEX or pendrin ± WNK4 and incubated at 17°C for 48 h in ND96 medium. Cl–/formate exchange activity was determined by the uptake of [14C] formate in the presence of an outward Cl– gradient (9). Before assay, oocytes were washed at room temperature in Cl–-free buffer (98 mM K+-gluconate/1.8 mM hemi-Ca2+-gluconate/1 mM hemi-Mg2+-gluconate/5 mM Tris·Hepes, pH 7.5), then incubated for 10 min in the presence of 71 μCi/ml [14C] formate in 100 mM K+-gluconate, 5 mM Tris, adjusted to pH 7.5 with Hepes. Oocytes were then washed in ice-cold Cl–-free buffer; uptake was measured by lysing oocytes in 10% SDS and β-scintillation counting of individual oocytes. Water-injected oocytes served as controls. In each experiment there were at least 12 oocytes in each group; results were highly reproducible in five independent experiments for CFEX and two for pendrin.

Data for each experimental group did not violate the assumption of a normal distribution, and the statistical significance of observed differences in flux between groups of oocytes was determined by two-tailed Student's t test.

Western Blot Analysis of Xenopus Oocyte Extracts. Western blot analysis of NKCC1 in oocytes injected with NKCC1 RNA ± WNK4 was performed essentially as described (8). Briefly, 2–4 days after injection with the appropriate RNA, four oocytes from each experimental group were removed from ND96 medium and homogenized in ice-cold anti-phosphatase solution (150 mM NaCl/30 mM NaF/5 mM EDTA/15 mM Na2HPO4/15 mM pyrophosphate/20 mM Hepes, pH 7.2) with 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics). The homogenate was cleared by centrifugation, and sample buffer was added; duplicate samples were fractionated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, incubated with anti-NKCC1 T4 antibody at a 1:1,000 dilution, washed, and incubated with anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. Chemiluminescence was performed as above.

Immunocytochemistry of Xenopus Oocytes. Two to 4 days after injection, oocytes were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, embedded in epon resin after EtOH dehydration, and cut in 1- to 2-μm sections. To increase antigen exposure, sections were etched with KOH-methanol-propylene oxide, followed by microwave pretreatment. Sections were then incubated with anti-NKCC1 T9 antibody at a 1:400 dilution. Sections were then incubated with anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody and visualized by immunofluoresence light microscopy.

Results

Extrarenal Expression of WNK4. To examine the expression of WNK4 transcripts in extrarenal mouse tissues, a mouse multiple tissue Northern blot was hybridized with a probe consisting of exons 16–18 of mouse WNK4 cDNA. Similar to results in humans (2), a major transcript of ≈5.5 kb is most abundant in kidney, but is also detected in testis and heart (Fig. 6a, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

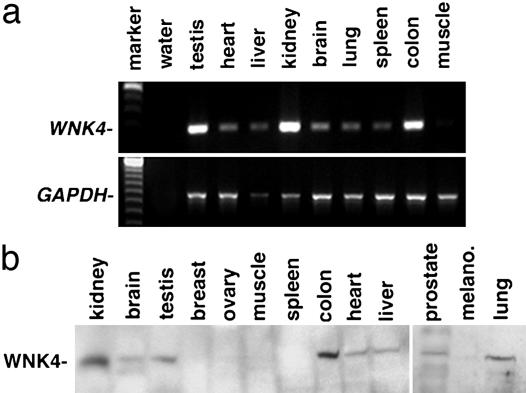

To use a more sensitive assay for extrarenal WNK4 transcripts, primers in exons 9 and 11 of mouse WNK4 were used to direct PCR by using cDNA from mouse tissues as a template. All tissues studied except skeletal muscle produced a 280-bp product derived from bona fide WNK4 mRNA (Fig. 1a). WNK4 transcripts were most abundant in kidney, testis, and colon.

Fig. 1.

Expression of WNK4 in extrarenal tissues. (a) RT-PCR analysis of WNK4. cDNA from indicated mouse tissues was used as a template for PCR by using primers specific for WNK4 (Upper) and GAPDH (Lower) mRNA, and the products were fractionated on agarose gels. (b) Western blot analysis of WNK4. Mouse or human tissue lysates were fractionated by SDS/PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-WNK4. A protein of ≈135 kDa, the expected size of WNK4 (2), is not exclusively expressed in kidney, but is also present in brain, testis, colon, heart, liver, prostate, and lung. All lysates are from mouse except breast, ovary, colon, melanocytes (melano.), and prostate.

To investigate whether WNK4 expression results in WNK4 protein, an anti-WNK4 antibody was used. In vitro-coupled transcription-translation demonstrated the specificity of this antibody (Fig. 6b). Whole-cell lysates of mouse or human tissues were analyzed by Western blotting using this anti-WNK4 antibody (Fig. 1b). Consistent with the results of RT-PCR, WNK4 is present in extrarenal tissues including brain, testis, colon, heart, liver, prostate, and lung. The concordance of mRNA and protein data provides strong evidence that WNK4 is expressed in extrarenal tissues.

Immunolocalization of Extrarenal WNK4. To determine the cell types in which WNK4 is expressed, we performed immunolocalization of WNK4 in mouse and/or human tissue sections. As described (2), WNK4 expression in kidney tubules (Fig. 2a) is confined to the distal convoluted tubule and CD of the distal nephron, as shown by costaining with antibodies to aquaporin 2 and NCCT (data not shown). In the distal convoluted tubule, WNK4 is largely associated with TJs, whereas in the CD, WNK4 localizes to the cytoplasm and TJs (data not shown).

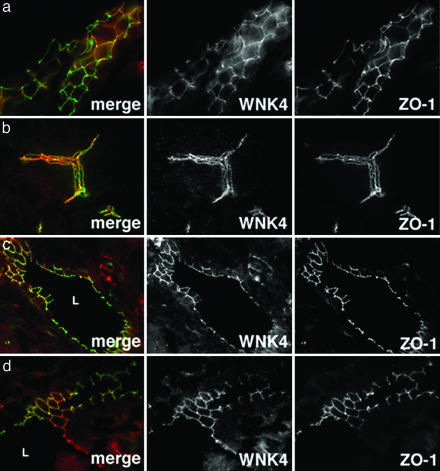

Fig. 2.

Immunolocalization of WNK4 in kidney, pancreas, liver, and epididymis. Frozen sections of mouse kidney, pancreas, liver, and epididymis were stained with anti-WNK4 (red) and anti-ZO-1 (green) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Composite images and views for WNK4 and ZO-1 alone are shown. (a) A renal tubule in longitudinal section is shown; WNK4 is confined to tubule epithelium and in this nephron segment largely colocalizes with the TJ protein ZO-1. (b) A large pancreatic duct in longitudinal section is shown; WNK4 expression is confined to pancreatic duct epithelia and largely overlaps with ZO-1. (c) A bile duct in cross section demonstrates that WNK4 localizes to epithelial cells that line the biliary tract lumen (L). WNK4 localization largely overlaps with ZO-1. (d) Image of the epididymis in cross section demonstrates WNK4 expression in the columnar epithelial cells lining the epididymal lumen (L) as well as more basal layers. WNK4 becomes more tightly membrane associated with apical progression. (Magnifications: ×600.)

In nonrenal tissues, WNK4 is not expressed in all cell types, but shows selective expression to polarized epithelia. Moreover, as seen in the kidney, WNK4 often shows prominent localization to intercellular junctions, extending from the TJ down the lateral membrane.

In the pancreas and liver, WNK4 is expressed in the cuboidal epithelial cells of interlobular and main pancreatic ducts, and the biliary ducts, respectively (Fig. 2 b and c). These ducts respectively mediate flow of exocrine pancreatic secretions and bile. WNK4 shows strong colocalization with ZO-1 in TJs and the lateral membrane in both tissues.

In the male reproductive tract, WNK4 is expressed in epididymis (Fig. 2d). WNK4 is found throughout the pseudostratified columnar epithelium; it is cytoplasmic in basal layers and becomes associated with intercellular junctions at more superficial layers. WNK4 is also expressed in the superficial layers of the seminiferous tubule stratified epithelium, where it localizes to TJs and the lateral membrane (data not shown).

In the brain, WNK4 is expressed in endothelial cells that comprise the blood–brain barrier (Fig. 3a). Within this endothelium, WNK4 is expressed near TJs and lateral membranes. WNK4 shows weaker staining in endothelial cells of other tissues (data not shown).

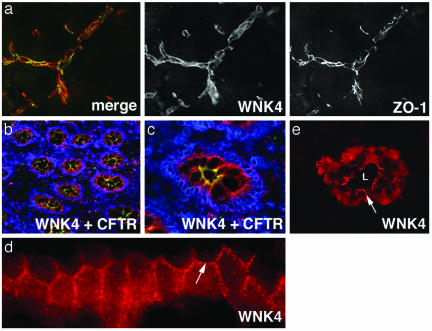

Fig. 3.

Expression of WNK4 in brain, colon, and skin. Frozen sections of mouse brain, human colon, and human skin were stained with anti-WNK4 (red), ZO-1 (green in a), CFTR (green in b and c), or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) and analyzed by immunofluorescence light microscopy. (a) Section of brain reveals WNK4 expression is highest in endothelial cells that comprise the blood–brain barrier and overlaps with ZO-1. (b) A low-power view of colonic crypts in cross section, demonstrating WNK4 localizes to the epithelium of crypts. CFTR staining highlights the crypt apical membrane. DAPI staining highlights nuclei. (c) A high-power view of a crypt in cross section showing WNK4, CFTR, and DAPI staining. (d) A longitudinal section of a crypt under high-power demonstrates the localization of WNK4 at intercellular junctions (arrow) in this epithelium. (e) High-power view of a sweat duct in cross section demonstrates that WNK4 is expressed in cuboidal epithelial cells lining sweat duct lumens (L). The arrow demonstrates WNK4's localization along the lateral membrane between adjacent epithelial cells. (Magnifications: ×600, a, c, and e; ×400, b; and ×1,000, d.)

In human colon (Fig. 3a), WNK4 expression is confined to the colonic crypt epithelium, the same cells that express CFTR (Fig. 3 b–d) (11). WNK4 appears to be both cytoplasmic and at intercellular junctions in this epithelium. In human skin, WNK4 is expressed in the epithelium of eccrine sweat ducts (Fig. 3e). In this epithelium, WNK4 is found both in the cytoplasm and at intercellular junctions.

WNK4 Regulates NKCC1. NCCT and ROMK, the known targets of WNK4, are not expressed in any of the extrarenal epithelia described above; these observations imply the presence of additional WNK4 targets in these tissues. The knowledge that the WNK4-expressing epithelia all are involved in Cl– transport, coupled with the genetic and biochemical evidence of WNK4's role in the regulation of renal Cl– homeostasis (2–4), suggests that WNK4 may play a role in regulating Cl– flux in these epithelia. One prominent candidate target is NKCC1, a mediator of Cl– transport across the basolateral membrane of Cl–-secreting epithelia; this entry step is integral for Cl– secretion in many epithelia including pancreatic ducts, colonic crypts, sweat ducts, epididymis, and respiratory tract (12). Moreover, NKCC1 is closely related in structure to the WNK4 target NCCT, sharing over >45% amino acid identity (13).

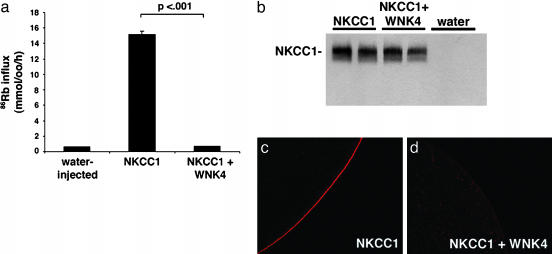

We expressed NKCC1 in Xenopus oocytes in the presence or absence of WNK4 and measured 86Rb-influx into oocytes (see Methods). Expression of NKCC1 alone resulted in a 15-fold increase in 86Rb influx compared with water-injected controls (Fig. 4a). Coexpression of NKCC1 with WT WNK4 resulted in loss of nearly all 86Rb influx attributable to NKCC1 (>95% reduction, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4a). This strong suppression was highly reproducible. Western blotting of whole oocyte homogenates with anti-NKCC1 shows no apparent difference in total cellular levels of NKCC1 with or without WNK4 (Fig. 4b), indicating that WNK4 does not impair the translation of NKCC1.

Fig. 4.

WNK4 is a regulator of NKCC1. (a) Effect of WNK4 on 86Rb influx mediated by NKCC1. Oocytes were injected with water or cRNA encoding NKCC1 alone or in combination with cRNA encoding WNK4 as indicated; 86Rb influx was measured as described in Methods. Results of a representative experiment are shown; bar graphs represent means ± SE of 86Rb influx for each experimental group. (b) Effect of WNK4 on total cellular NKCC1 protein. A Western blot of whole oocyte lysates expressing NKCC1 in the presence or absence of WNK4 is shown. Samples were run in duplicate. The total amount of NKCC1 produced in injected oocytes is not altered by the presence of WNK4. (c and d) Effect of WNK4 on the surface expression of NKCC1. Representative examples of immunofluoresence microscopy of Xenopus ooctyes stained with anti-NKCC1 antibody. Oocytes were injected with cRNA encoding NKCC1 alone (b) or in combination with WNK4 (c) as described in Methods. (Magnifications: ×600.)

WNK4 inhibits the activity of NCCT and ROMK by reducing the expression of these proteins at the plasma membrane (3–5). To determine whether WNK4 inhibits NKCC1 activity by a similar mechanism, we examined the surface expression of NKCC1 by using an anti-NKCC1 antibody (Fig. 4 c and d). Surface expression of NKCC1 is dramatically reduced by the addition of WNK4. These findings indicate that a major, if not the sole, mechanism by which WNK4 inhibits NKCC1 function is via reduced surface expression of NKCC1.

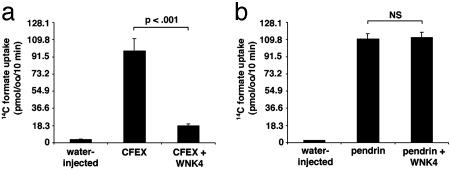

WNK4 Regulates SLC26A6 (CFEX) but Not Pendrin. If WNK4 regulates basolateral Cl– flux, does it also regulate apical Cl– flux? The anion exchanger CFEX mediates several different Cl–/base exchange activities, including Cl–/formate, Cl–/oxalate, and Cl–/HCO3– exchange (9, 14–16). Outside of the renal proximal tubule (9), CFEX has been immunolocalized to the apical membranes of epithelia in the intestine (16) and pancreatic ducts (17); CFEX is also expressed in testis (9) and liver (9). In these epithelia, CFEX may function in series with CFTR to mediate net  secretion via

secretion via  exchange (9); the expression of WNK4 in these epithelia suggests it could regulate this process. We expressed CFEX in Xenopus oocytes alone or in combination with WNK4 and determined the resulting [14C] formate uptake via Cl–/formate exchange. Expression of CFEX alone resulted in a 25-fold increase of [14C] formate influx compared with water-injected controls (Fig. 5a). Coexpression of CFEX with WT WNK4 resulted in a >80% reduction of [14C] formate influx (Fig. 5a). This inhibition was highly statistically significant (P < 0.001) and reproducible.

exchange (9); the expression of WNK4 in these epithelia suggests it could regulate this process. We expressed CFEX in Xenopus oocytes alone or in combination with WNK4 and determined the resulting [14C] formate uptake via Cl–/formate exchange. Expression of CFEX alone resulted in a 25-fold increase of [14C] formate influx compared with water-injected controls (Fig. 5a). Coexpression of CFEX with WT WNK4 resulted in a >80% reduction of [14C] formate influx (Fig. 5a). This inhibition was highly statistically significant (P < 0.001) and reproducible.

Fig. 5.

WNK4 is a regulator of CFEX, but not pendrin. (a) Effect of WNK4 on 14C formate uptake mediated by CFEX. Oocytes were injected with water or cRNA encoding CFEX alone or in combination with WNK4; 14C formate uptake was measured as described in Methods. Results of a representative experiment are shown. (b) Effect of WNK4 on 14C formate uptake mediated by pendrin. Oocytes were injected with water or cRNA encoding pendrin alone or in combination with WNK4 as indicated; 14C formate uptake was measured as described in Methods. Results of a representative experiment are shown.

We also examined WNK4's effect on the activity of pendrin, a related SLC26 family anion exchanger (≈40% amino acid identify with CFEX) capable of mediating Cl–/formate, Cl–/iodide, and  exchange (18). Pendrin is expressed on the apical membranes of epithelia in the inner ear (19), thyroid gland (20), and a subpopulation of intercalated cells in the renal CD (21–23). Pendrin mutation results in the Pendred syndrome of congenital sensorineural hearing loss and goiter (24). Expression of pendrin alone resulted in a >20-fold increase of [14C] formate influx into oocytes compared with water-injected controls. Coexpression of pendrin with WT WNK4 resulted in no significant change in [14C] formate influx (Fig. 5b).

exchange (18). Pendrin is expressed on the apical membranes of epithelia in the inner ear (19), thyroid gland (20), and a subpopulation of intercalated cells in the renal CD (21–23). Pendrin mutation results in the Pendred syndrome of congenital sensorineural hearing loss and goiter (24). Expression of pendrin alone resulted in a >20-fold increase of [14C] formate influx into oocytes compared with water-injected controls. Coexpression of pendrin with WT WNK4 resulted in no significant change in [14C] formate influx (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

Previous work identified WNK4 as an important regulator of renal electrolyte flux. WT WNK4 inhibits the activity of NCCT and ROMK, and missense mutations in WNK4 found in PHAII have divergent effects on these inhibitory actions, relieving inhibition of NCCT but increasing inhibition of ROMK (5). Moreover, WNK4 inhibits NCCT and ROMK via distinct mechanisms, the former being kinase dependent (3), the latter being kinase independent via a clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway (5).

We now show that WNK4 plays a role outside the kidney. WNK4 is expressed in many extrarenal tissues and shows selective expression in epithelia that mediate electrolyte flux. These include epithelia that regulate the ionic composition and volume of fluid flowing through the lumens of the colon, pancreatic duct, bile duct, sweat duct, and epididymis. These extrarenal sites of WNK4 expression show strong overlap with the localization of the structurally and functionally related kinase WNK1 (6), and also CFTR (25), a mediator and regulator of Cl– flux. Cl– flux across these epithelia are important for their normal function, as demonstrated by the pathology of cystic fibrosis resulting from loss of CFTR activity. In addition to impaired pulmonary function, affected patients have exocrine pancreatic insufficiency caused by inadequate Cl–-dependent  secretion into pancreatic ducts, hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis caused by inspissated biliary secretions, male sterility caused by obstruction and atrophy in the distal epididymis, and abnormal sweat duct function and meconium pseudoileus or distal intestinal impaction caused by reduced intestinal fluid secretion (26–30).

secretion into pancreatic ducts, hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis caused by inspissated biliary secretions, male sterility caused by obstruction and atrophy in the distal epididymis, and abnormal sweat duct function and meconium pseudoileus or distal intestinal impaction caused by reduced intestinal fluid secretion (26–30).

In addition to the striking overlap of expression with CFTR, we show that WNK4 regulates NKCC1 and CFEX. The expression of both proteins in extrarenal WNK4-expressing epithelia suggests the physiologic significance of this inhibition. NKCC1 is required for Cl– flux across basolateral membranes, whereas CFEX mediates Cl–/anion exchange across apical membranes. Similar to NCCT and ROMK, WNK4's inhibition of NKCC1 occurs via reduced surface expression of the cotransporter; further work will be required to establish details of the molecular mechanism(s).

These findings expand the list of ion transporters regulated by WNK4 to four members that are diverse in nature, including a cation channel, two electroneutral cotransporters, and an anion exchanger. The complete spectrum of WNK4 targets and mechanisms of regulation remains to be established. Similarly, the upstream factors that regulate WNK4's inhibitory effects are also unknown; although NaCl appears to regulate the kinase activity of WNK1 (31), the mechanism of this effect remains to be determined.

In addition to regulating mediators of transcellular Cl– flux, the prominent localization of WNK4 at TJs and lateral membranes of epithelia is noteworthy. This localization is seen in the kidney with two different anti-WNK4 antibodies and in many extrarenal epithelia as well. The TJ constitutes the barrier to paracellular flux of electrolytes and solutes; in many epithelia, paracellular Cl– flux plays an important role in electrolyte homeostasis (1). For example, electrogenic Na+ reabsorption via the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) in the renal CD can be accompanied either by paracellular Cl– reabsorption or transcellular K+ secretion. Opening this paracellular pathway would increase net NaCl reabsorption while inhibiting K+ secretion. The phenotype of PHAII and the expression of WNK4 at TJs raises the question of whether WNK4 might play a role in the regulation of paracellular Cl– flux, and thus regulate both transcellular and paracellular flux pathways. Further work will be required to determine whether WNK4 might also regulate functional components of the paracellular pathway such as the claudins, pore-forming TJ proteins that exhibit channel-like properties such as charge and size selectivity (1, 32–34).

The regulation of CFEX by WNK4 is of interest. CFEX was first characterized as a Cl–/formate exchanger in the brush border of proximal tubule cells (9); however, it can also participate in Cl–/oxalate and  exchange (14–16). CFEX is expressed in pancreas, liver, and testis (9, 17, 35), tissues whose epithelial ducts all secrete

exchange (14–16). CFEX is expressed in pancreas, liver, and testis (9, 17, 35), tissues whose epithelial ducts all secrete  by

by  exchange coupled to CFTR-regulated Cl– secretion (36). It is tempting to speculate that WNK4 and CFEX play a role in these processes in vivo.

exchange coupled to CFTR-regulated Cl– secretion (36). It is tempting to speculate that WNK4 and CFEX play a role in these processes in vivo.

Finally, the recognition that WNK kinases play a role in the regulation of electrolyte homeostasis in epithelia outside the kidney raises the question of whether PHAII patients with mutations in WNK1 or WNK4 have extrarenal phenotypes. WNK4 missense mutations are genetically complex, resulting in loss-of-function for regulation of NCCT (3) but gain-of-function for ROMK (5); the effects on other targets are presently unknown. Evaluation of the function and/or composition of sweat, bile, and pancreatic secretions among PHAII patients might be revealing. Similarly, evaluation of animals with directed mutation in WNK function in selected tissues will also be of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Steven Hebert, Qiang Leng, Gordon MacGregor, and Tony O'Connell for advice and insightful comments; members of the laboratories of Steven Hebert and Walter Boron for harvest of oocytes; and SueAnn Mentone for oocyte immunofluorescence experiments. This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Specialized Center of Research in Hypertension grant (to R.P.L.) and National Institutes of Health Grants DK33793 and DK17433 (to P.S.A.). K.T.K. is a recipient of a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Student Research Fellowship. R.P.L. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations: WNK, with no lysine (K); PHAII, pseudohypoaldosteronism type II; CFEX, Cl–/base exchanger SLC26A6; NKCC1, Na+-K+-2Cl– cotransporter; CD, collecting duct; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; TJ, tight junction; ZO-1, zona occludens-1.

References

- 1.Tsukita, S., Furuse, M. & Itoh, M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson, F., Disse-Nicodeme, S., Choate, K., Ishikawa, K., Nelson-Williams, C., Desitter, I., Gunel, M., Milford, D., Lipkin, G., Achard, J., et al. (2001) Science 293, 1107–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson, F., Kahle, K., Sabath, E., Lalioti, M., Rapson, A., Hoover, R., Hebert, S., Gamba, G. & Lifton, R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 680–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang, C., Angell, J., Mitchell, R. & Ellison, D. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 7, 1039–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahle, K., Wilson, F., Leng, Q., Lalioti, M., O'Connell, A., Dong, K., Rapson, A., MacGregor, G., Giebisch, G., Hebert, S. & Lifton, R. (2003) Nat. Genet. 4, 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choate, K., Kahle, K., Wilson, F., Nelson-Williams, C. & Lifton, R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 663–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lytle, C., Xu, J., Biemesderfer, D., Haas, M. & Forbush, B. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 35, 25428–25437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimenez, I., Isenring, P. & Forbush, B. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 11, 8767–8770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knauf, F., Yang, C., Thomson, R., Mentone, S., Giebisch, G. & Aronson, P. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 16, 9425–9430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott, D. & Karniski, L. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 1, C207–C211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheppard, D. & Welsh, M. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, Suppl. 1, S23–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas, M. & Forbush, B. (2000) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62, 515–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamba, G., Saltzberg, S., Lombardi, M., Miyanoshita, A., Lytton, J., Hediger, M., Brenner, B. & Hebert, S. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 2749–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang, Z., Grichtchenko, I., Boron, W. & Aronson, P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 37, 33963–33967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie, Q., Welch, R., Mercado, A., Romero, M. & Mount, D. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 4, F826–F838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, Z., Petrovic, S., Mann, E. & Soleimani, M. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 3, G573–G579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohi, H., Kujala, M., Kerkela, E., Saarialho-Kere, U., Kestila, M. & Kere, J. (2000) Genomics 1, 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markovich, D. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 4, 1499–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Everett, L., Morsli, H., Wu, D. & Green, E. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 17, 9727–9732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royaux, I., Suzuki, K., Mori, A., Katoh, R., Everett, L., Kohn, L. & Green, E. (2000) Endocrinology 2, 839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royaux, I., Wall, S., Karniski, L., Everett, L., Suzuki, K., Knepper, M. & Green, E. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 7, 4221–4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, Y., Kwon, T., Frische, S., Kim, J., Tisher, C., Madsen, K. & Nielsen, S. (2002) Am. J Physiol. 4, F744–F754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner, C., Finberg, K., Stehberger, P., Lifton, R., Giebisch, G., Aronson, P. & Geibel, J. (2002) Kidney Int. 62, 2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Everett, L., Glaser, B., Beck, J., Idol, J., Buchs, A., Heyman, M., Adawi, F., Hazani, E., Nassir, E., Baxevanis, A., et al. (1997) Nat. Genet. 17, 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tizzano, E. & Buchwald, M. (1995) Ann. Intern. Med. 123, 305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kartner, N., Augustinas, O., Jensen, T., Naismit, A. & Riordan, J. (1992) Nat. Genet. 5, 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marino, C., Matovcik, L., Gorelick, F. & Cohn, J. (1991) J. Clin. Invest. 2, 712–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tizzano, E., Silver, M., Chitayat, D., Benichou, J. & Buchwald, M. (1994) Am. J. Pathol. 5, 906–914. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohn, J., Strong, T., Picciotto, M., Nairn, A., Collins, F. & Fitz, J. (1993) Gastroenterology 6, 1857–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strong, T., Boehm, K. & Collins, F. (1994) J. Clin. Invest. 93, 347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu, B., English, J., Wilsbacher, J., Stippec, S., Goldsmith, E. & Cobb, M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 22, 16795–16801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitic, L., Van Itallie, C. & Anderson, J. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 279, G250–G254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang, V. & Goodenough, D. (2003) Biophys. J. 84, 1660–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon, D., Lu, Y., Choate, K., Velazquez, H., Al-Sabban, E., Praga, M., Casari, G., Bettinelli, A., Colussi, G., Rodriguez-Soriano, J., et al. (1999) Science 5424, 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldegger, S., Moschen, I., Ramirez, A., Smith, R., Ayadi, H., Lang, F. & Kubisch, C. (2001) Genomics 72, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welsh, M., Ramsey, B., Accurso, F. & Cutting, G. (2001) in The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease, eds. Scriver, C., Beaudet, A., Sly, W. & Valle, D. (McGraw–Hill, New York), pp. 5121–5188.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.