Abstract

Wolbachia are endosymbiotic bacteria that commonly infect arthropods, inducing certain phenotypes in their hosts. So far, no endemic South American species of terrestrial isopods have been investigated for Wolbachia infection. In this work, populations from two species of Balloniscus (B. sellowii and B. glaber) were studied through a diagnostic PCR assay. Fifteen new Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences were detected. Wolbachia found in both species were generally specific to one population, and five populations hosted two different Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences. Prevalence was higher in B. glaber than in B. sellowii, but uninfected populations could be found in both species. Wolbachia strains from B. sellowii had a higher genetic variation than those isolated from B. glaber. AMOVA analyses showed that most of the genetic variance was distributed among populations of each species rather than between species, and the phylogenetic analysis suggested that Wolbachia strains from Balloniscus cluster within Supergroup B, but do not form a single monophyletic clade, suggesting multiple infections for this group. Our results highlight the importance of studying Wolbachia prevalence and genetic diversity in Neotropical species and suggest that South American arthropods may harbor a great number of diverse strains, providing an interesting model to investigate the evolution of Wolbachia and its hosts.

Keywords: Wolbachia, prevalence, diversity, South America, Oniscidea

Introduction

Wolbachia are maternally transmitted alpha-proteobacteria known to infect a wide range of arthropods and nematodes, where they can be found in either germ line or somatic tissues (Bandi et al., 1998; O’Neill et al., 1997; Werren et al., 1995a). Depending on both bacterial lineage and host, they may have different effects on host reproduction, such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (Breeuwer and Werren, 1990; O’Neill and Karr, 1990), male killing (Hurst et al., 1999), parthenogenetic reproduction (Stouthamer, 1997; Zchori-Fein et al., 2001) or feminization of genetic males (Bouchon et al., 1998; Juchault et al., 1994). Therefore, these bacteria may have a strong influence on the evolution of their host populations.

Terrestrial isopod species (Crustacea, Oniscidea) are widely infected with Wolbachia with prevalence reaching ∼61% (∼36 infected species) in this group (Bouchon et al., 2008). Accurate estimates of Wolbachia prevalence are difficult to obtain, and both under and/or overestimation may occur. Underestimation may be caused by: (1) incomplete sampling (not all populations are infected), and because (2) infected and uninfected individuals often coexist in the same population (Cook and Butcher, 1999; Hilgenboecker et al., 2008). For example, six species tested by Bouchon et al. (1998) and showing no evidence of infection were positive in other assays. Furthermore, Verne et al. (2011) studied 13 French populations of Armadillidium vulgare and found that the prevalence in females ranged from 0% to 100%, and Bouchon et al. (2008), in a meta-analysis of infected populations, found a frequency of infected females that ranged from 5% to 74%. In both studies, the authors observed that the overall prevalence of Wolbachia was higher than that found in other studies in France with the same species (Cordaux et al., 2004; Moret et al., 2001; Rigaud et al., 1999). On the other hand, overestimation may result from sampling bias if infected populations are more frequently sampled, and also from false positives in PCR surveys (Li et al., 2007).

Due to the non-cultivable nature of Wolbachia, the most common method for detecting infection is the enzymatic amplification of one or more Wolbachia gene fragments (O’Neill et al., 1997). Sequencing of one or several Wolbachia genes is applied for genotyping of Wolbachia strains, although a multiple-gene sequencing approach would be desirable (Baldo et al., 2006b; Paraskevopoulos et al., 2006; Ros et al., 2009). Previous analyses based on ftsZ, wsp, (Lo et al., 2002; van Meer et al., 1999) and 16S rDNA genes (Bandi et al., 1999; Vanderkerckhove et al., 1999) suggested that current Wolbachia strains are structured in eight Supergroups (A–H). Recently, three new supergroups (I, J and K) were proposed based on the analysis of four Wolbachia genes (ftsZ, groEL, glta and 16S rDNA) (Ros et al., 2009).

Phylogenetic relationships between Wolbachia strains are very controversial and could not be well established (Lo et al., 2007). It is possible that at least in some cases, exchanges of genetic material (recombination) between Wolbachia strains may account for the observed relations between supergroups (Baldo et al., 2006a). Recombination is widespread throughout Wolbachia genomes, causing some phylogenetic uncertainties. For example, Supergroup G, containing strains infecting spiders, seems to be the result of recombination between strains of Supergroups A and B (Baldo and Werren, 2007). However it is well known that the phylogenetic relationships of Wolbachia do not mirror those of its hosts since numerous host shifts have been reported (Riegler and O’Neill, 2006).

To date, almost all Wolbachia strains from terrestrial isopods belong to Supergroup B, based on 16 rDNA and ftsZ sequences and corroborated by wsp and groEL phylogenies (Bouchon et al., 1998; Cordaux et al., 2001; Baldo et al., 2006b; Wiwatanaratanabutr et al., 2009). In Supergroup B, phylogenies suggested that Wolbachia strains from terrestrial isopods form a polyphyletic clade, even though the majority of strains group in the Oniclade (Bouchon et al., 1998; Cordaux et al., 2001; Wiwatanaratanabutr et al., 2009).

Although terrestrial isopods have long been known to be infected (Legrand and Juchault, 1970), no endemic South American species has been investigated up to now for prevalence and genetic diversity of Wolbachia. Balloniscus sellowii is a species with wide distribution, occurring from southern Brazil to Uruguay and Argentina (Lemos de Castro, 1976), where it is often associated with anthropized environments and exotic forests (Araujo et al., 1996). On the other hand, B. glaber (Araujo and Zardo, 1995), whose distribution overlaps with that of B. sellowii, is endemic and restricted to the southernmost state of Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul, where it occurs associated with remnants of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Due to deforestation, fragmentation and replacement by exotic species in this biome (Morellato and Haddad, 2000), B. glaber is susceptible to extinction (Quadros et al., 2009).

Here, we present the first description of Wolbachia infection in two South American species of terrestrial isopods, specifically in Balloniscus sellowii and B. glaber. Moreover, Wolbachia sequences were shown to exhibit a high level of genetic variation within and between their host species. There is evidence of cross-specific transmissions between species and the evolutionary implications of these observations are discussed.

Material and Methods

Sample collection

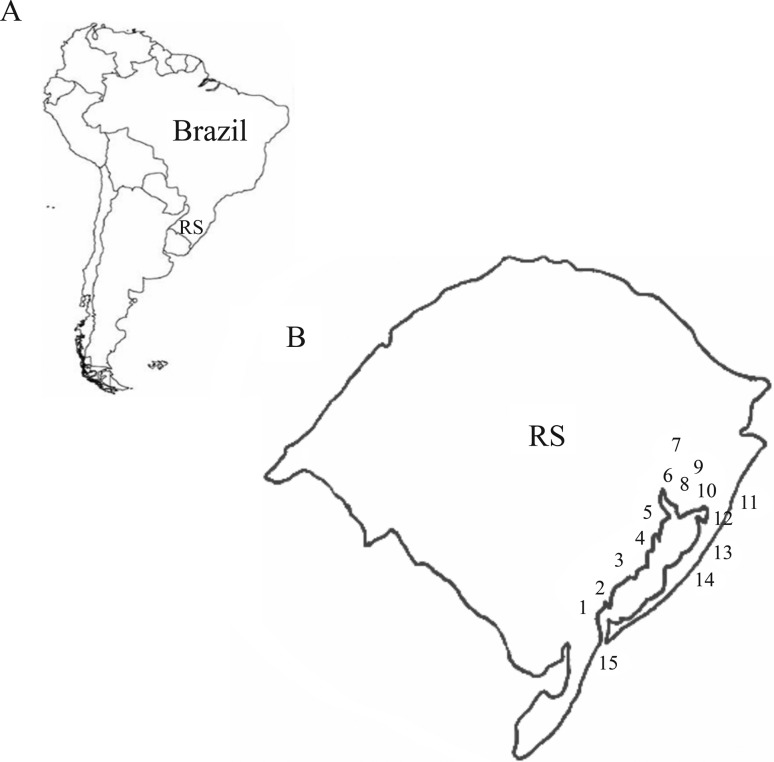

Individuals of B. sellowii and B. glaber were hand collected from soil, placed in 100% ethanol and kept refrigerated until DNA extraction. Nine populations of B. glaber and thirteen populations of B. sellowii were sampled in the coastal plain of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (Figure 1). This area is an elongate (620 km) and wide (up to 100 km) physiographic province which covers about 33,000 km2 (Tomazelli et al., 2000).

Figure 1.

Study area (RS: Rio Grande do Sul; PL: Patos lagoon). Populations; PEL (1) (Pelotas); CZ3 (2) (Colônia Z3); SLS (3) (São Lourenço do Sul); TAP (4) (Tapes); BRI (5) (Barra do Ribeiro); ABE (6) (Águas Belas); CSU (7) (Caxias do Sul); POA (8) (Porto Alegre); MSA (9) (Morro Santana); GLO (10) (Glorinha); CID (11) (Cidreira); PAL (12) (Palmares do Sul);. MOS (13) (Mostardas); TAV (14) (Tavares); CAS (15) (Cassino).

DNA extraction

Total genomic DNA was obtained by the Chelex® (BioRad) method from different parts of the body including reproductive (ovaries and testis), nerve and muscular tissue of fixed individuals. Dissection procedures were performed under sterile conditions as previously described (Bouchon et al., 1998).

Assay for Wolbachia

The presence of Wolbachia was detected by PCR with Wolbachia-specific primers for 16S rDNA (O’Neill et al., 1992). Failure of amplification with general 16S rDNA primers could be due to either: (i) absence of Wolbachia, (ii) failure in DNA extraction procedure, and/or (iii) incorrect concentration of DNA solutions (Werren et al., 1995a). In order to control for the last two possibilities, we tested whether the samples scored as negative for Wolbachia would result in positive amplification of the host mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I gene (COI) (Folmer et al., 1994). Samples yielding a product of expected size were considered to be true negatives for the Wolbachia assay.

Additionally, we tested four other Wolbachia genes (groEL, dnaA, ftsZ and wsp) using PCR, and each of them showed different results for Wolbachia detection. For example, in one assay out of 20 positives for the 16S rDNA gene, we observed only ten, six, four and two positives for groEL, dnaA, ftsZ and wsp genes, respectively. Based on these findings we concluded that amplification of the 16S rDNA seems to be the most sensitive for Wolbachia detection in Balloniscus species by means of a PCR assay. Furthermore, we tested five and 10 individuals of Armadillidium vulgare and A. nasatum, respectively, for all genes cited above. These are exotic Palearctic species forming sympatric populations with those of Balloniscus. Variations in prevalence were checked by logistic regressions using JMP 5.0.1 software (SAS Institute).

PCR methods, purification and sequencing

We amplified most of the Wolbachia 16SrDNA gene using the Wolbachia-specific primers 99F 5′-TTG TAG CCT GCT ATG GTA TAA CT-3′ and 994R 5′-GAA TAG GTA TGA TTT TCA TGT-3′ (O’Neill et al., 1992), which yield a product of around 900 bp. PCR was carried out in a volume of 25 μL, using 12.5 ng of total DNA, 0.125 U of GoTaq (Promega), 1x GoTaq buffer (Promega), 5 μM of each primer, and 0.2 mM of dNTPs. PCR cycling conditions were 35 cycles (1 min at 95 °C, 1 min at 50.6 °C, 1 min at 72 °C), including an initial denaturing step of 95 °C for 2 min and a final extension step of 72 °C for 5 min. To check PCR success and size of the amplified DNA, 5 μLof the reaction product was run on 1.5% agarose gel. PCR products were purified using Exosap-IT (Amersham Biosciences). Sequencing was done using BigDye v3.1 and an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). All different strains were deposited in the GenBank-EMBL database under the accession numbers GQ229434-GQ229446 and GQ229448-GQ229450.

Sequence polymorphism and phylogeny

A total of 77 16S rDNA sequences, representing almost all Wolbachia supergroups were aligned using Clustal X (Thompson et al., 1997). The alignment was visually inspected using the BioEdit program (Hall, 1999). Exceptions were Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences of Supergroups G and H. As sequences from Supergroup G probably resulted from a recombination event between strains of Supergroups A and B (Baldo and Werren, 2007), the inclusion of sequences from these supergroups resulted in phylogenetic trees with very low support values (data not shown). Concerning sequences from Supergroup H (Zootermopsis angusticollis - AY764279 and Z. nevadensis - AY764280) a different portion of the 12S gene was amplified and these sequences did not align with those sequenced in this study.

Two 16S rDNA sequences from Rickettsia ricketsii and Anaplasma marginale were included as outgroups. Alignment was improved by checking the secondary structure of 16S rDNA sequences according to the RDP database. As the current strain definition in Wolbachia involves data from multiple genes we did not consider the 16S lineages found in this study as representing different bacterial “strains”. Anyway, for naming purposes two lineages were considered identical only if they had identical nucleotide sequences. Presence of recombination was checked using RDP version 2.0 (Martin et al., 2005), since recombination may occur in individuals infected with multiple Wolbachia strains (see Jiggins et al., 2001 for a review). We used the Arlequin 3.1 program (Excoffier et al., 2005) to assess how much of the total genetic variation (measured by ΦST) was partitioned between the two species through AMOVA (Excoffier et al., 1992).

The phylogeny of all Wolbachia sequences was estimated using the Bayesian method implemented in Beast version 1.4.7 software (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007), in which the tree-space and the parameter space are analyzed simultaneously running a MCMC for 100,000,000 steps based on the GTR+Γ model, on a Yule speciation process, and assuming a lognormal relaxed molecular clock (Drummond et al., 2006). All other priors were set to the default values. The monophyly of Wolbachia lineages from Balloniscus was tested through the Bayes factor (BF) (Suchard et al., 2005) by comparing an unconstrained topology with that generated with the same search strategy described above, but enforcing a monophyletic group formed by all lineages found in Balloniscus. Results are expressed as log10BF. Values of log10BF = 2 or higher are considered significant evidence for a given hypothesis (Kass and Raftery, 1995).

Finally, a median-joining network (Bandelt et al., 2000) was constructed using the Network version 4.610 software to check the number of mutated nucleotide positions defining each grouping, as well as to infer the genetic diversity within the 16S rDNA sequences from Supergroup B.

Results

Wolbachia prevalence in B. glaber and B. sellowii

In all, 265 individuals of B. sellowii were sampled in 13 populations with 42 of them being infected, while for B. glaber 254 individuals were sampled in nine populations with 99 individuals being infected (Table 1). There was no significant difference in population sex ratio for either species (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.5206). The percentages of males and females were 34% and 66% and 37% and 63% in B. selowii and B. glaber, respectively. No intersexual individual was found in either species. B. sellowii showed no differences of prevalence between males (13%) and females (17%) (Logistic regression, Wald test, p = 0.9998), while B. glaber showed a higher Wolbachia prevalence in females (45%) than in males (23%); (Logistic regression Wald test; p < 0.001). On average, B. sellowii also showed lower infection rates than B. glaber (16% and 37%; Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001), mainly due to the higher frequency of infected females in B. glaber (nested logistic regression, Wald test, p < 0.001) (Table 1). For each species, the prevalence varied widely in different populations (logistic regression, Wald test, p < 0.001) ranging from 0% to 52.6% in B. selowii and from 0% to 87.5% in B. glaber. Wolbachia was found in seven out of nine populations of B. glaber and in nine out of 13 populations of B. sellowii suggesting that Wolbachia prevalence is not different between these species (Fisher’s exact test; p = 0.65). Considering both species, no infected individuals were found in four (ABE, 6; PEL, 1; PAL, 12 and CSU, 7) out of 15 populations. B. sellowii and B. glaber were sympatric in two of all uninfected populations (ABE, 6 and PEL, 1), while in the remaining two (PAL, 12 and CSU, 7) only B. sellowii individuals were observed.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Wolbachia in B. sellowii and B. glaber populations.

|

B. sellowii

|

B. glaber

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locality | N (F/M) | Strain | IF | IM | II | N (F/M) | Strain | IF | IM | II |

| ABE (6) | 7/12 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26/21 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BRI (5) | 20/6 | wSel1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 13/8 | wGla1 | 11 | 4 | 15 |

| CAS (15) | 11/5 | wSel2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 18/12 | wGla1 | 11 | 4 | 16 |

| CID (11) | 13/11 | wSel7 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 26/6 | wGla3 | 24 | 4 | 28 |

| CSU (7) | 8/5 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| CZ3 (2) | 25/13 | wBal2 wSel6 | 4* | 1* | 5* | 15/17 | wGla1 | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| GLO (10) | 11/5 | wSel3 wSel7 | 2* | 0* | 2* | - | - | - | - | - |

| MOS (14) | - | - | - | - | - | 10/5 | wGla2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| MSA (9) | - | - | - | - | - | 33/11 | wBal2 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| PAL (12) | 14/8 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| PEL (1) | 11/5 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6/5 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| POA (8) | 20/4 | wSel4 wSel5 | 8* | 1* | 9* | - | - | - | - | - |

| SLS (3) | 13/6 | wSel8 wSel9 | 8* | 2* | 10* | - | - | - | - | - |

| TAP (4) | 12/6 | wSel9 wSel10 | 0* | 4* | 4* | - | - | - | - | - |

| TAV (14) | 10/4 | wBal1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 13/9 | wBal1 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Total | 175/90 | 30 | 12 | 42 | 160/94 | 77 | 22 | 99 | ||

N = Number of individuals tested (Females; Males); IF: Number of infected females; IM: Number of infected males; II: Number of infected individuals.

Overall prevalence (individuals may harbor one or both sequences found in these populations) -: Species not found; Populations: PEL (1) (Pelotas); CZ3 (2) (Colônia Z3); SLS (3) (São Lourenço do Sul); TAP (4) (Tapes); BRI (5) (Barra do Ribeiro); ABE (6) (Águas Belas); CSU (7) (Caxias do Sul); POA (8) (Porto Alegre); MSA (9) (Morro Santana); GLO (10) (Glorinha); CID (11) (Cidreira); PAL (12) (Palmares do Sul);. MOS (13) (Mostardas); TAV (14) (Tavares); CAS (15) (Cassino).

Genetic variation among Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences from Balloniscus

A total of 35 sequences of Wolbachia 16S rDNA from Balloniscus were obtained. No recombination event was detected among the sequences. The general level of genetic diversity is presented in Table 2. By any measure, Wolbachia sequences from B. sellowii had a higher genetic variation when compared to those isolated from B. glaber. AMOVA estimates were that 25.61% of the total genetic variance is contained at the between-species level, while an additional 60.15% is distributed among populations of each species. The within-population level accounts for the remaining 14.24% of the genetic variance. The genetic diversity found in Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences from Balloniscus was higher than that found in sequences obtained from species belonging to the genus Armadillidium, and was comparable to that found in sequences obtained from all species of European terrestrial isopods together (Table 2).

Table 2.

Wolbachia diversity and polymorphism of 16S rDNA in Balloniscus species and European isopods.

| Balloniscus | Armadillidium | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of polymorphic sites | B. sellowii (24) | Armadillidium genus1 (15) |

|

| ||

| B. glaber (9) | All sampled European species2 (34) | |

| Balloniscus genus (33) | ||

|

| ||

| Nucleotide diversity (π) | B. sellowii (0.008) | Armadillidium genus1 (0.002) |

| B. glaber (0.005) | All sampled European species2 (0.013) | |

| Balloniscus genus (0.010) | ||

A. vulgare Angouleme (France) AJ223238, A. vulgare Niort (France) X65669, A. vulgare Dunasziget (Hungary) AJ306311, A. nasatum Mignaloux (France) AJ223239, A. nasatum Barra do Ribeiro/RS (Brazil) GQ 229450, A. album Yves (France) AJ223240.

A. album Yves (France) AJ223240, A. nasatum Mignaloux (France) AJ223239, A. vulgare Angouleme (France) AJ223238, A. vulgare Niort (France) X65669, A. vulgare Dunasziget (Hungary) AJ306311, Cylisticus. convexus Avanton (France) AJ001602, C. convexus Tatabanya (Hungary) AJ306312, Porcellio scaber Ahun (France) AJ001608, P. scaber Dunasziget AJ306307, P. spinicornis Quincay (France) AJ001609, P. dilatatus St. Honorat Island (France) X65673, P. dilatatus Tatabanya (Hungary) AJ306314, Chaetophiloscia elongata Celle sur Belle (France) AJ223241, Helleria brevicornis Bastia (France) AJ001603, Haplophthalmus danicus Quincay (France) AJ001604, Ligia oceanica Angoulins (France) AJ001605, Oniscus asellus Quincay (France) AJ001606, Philoscia muscorum Quincay (France) AJ001607, Porcellionides pruinosus AJ 223242, P. pruinosus AJ133196, Trachelipus atzeburgii Tatabanya (Hungary) AJ306315, T. ratzeburgii Dunasziget (Hungary) AJ306309, T. politus Tatabanya (Hungary) AJ306313, T. rathkii Dunasziget (Hungary) AJ306310, H. riparius Dunasziget (Hungary) AJ306308.

Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequence diversity and distribution

We found 15 new Wolbachia sequences in the two Balloniscus species studied here. Among these, 10 were associated exclusively with B. sellowii and named wSel1, wSel2, wSel3, wSel4, wSel5, wSel6, wSel7, wSel8, wSel9 and wSel10, and three sequences were associated exclusively with B. glaber and named wGla1, wGla2 and wGla3. Furthermore, two sequences were shared by both species: wBal1 and wBal2. The 16S rDNA sequence of the Wolbachia found in one individual of A. nasatum sampled in BRI (5) (wNasBRI) differed from those found in European populations by a single 1 bp indel. Noteworthy, five out of nine infected populations (CZ3, 2; GLO, 10; POA, 8; SLS, 4 and TAP, 4) hosted two different Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences, although no evidence of co-infections in a single individual was found.

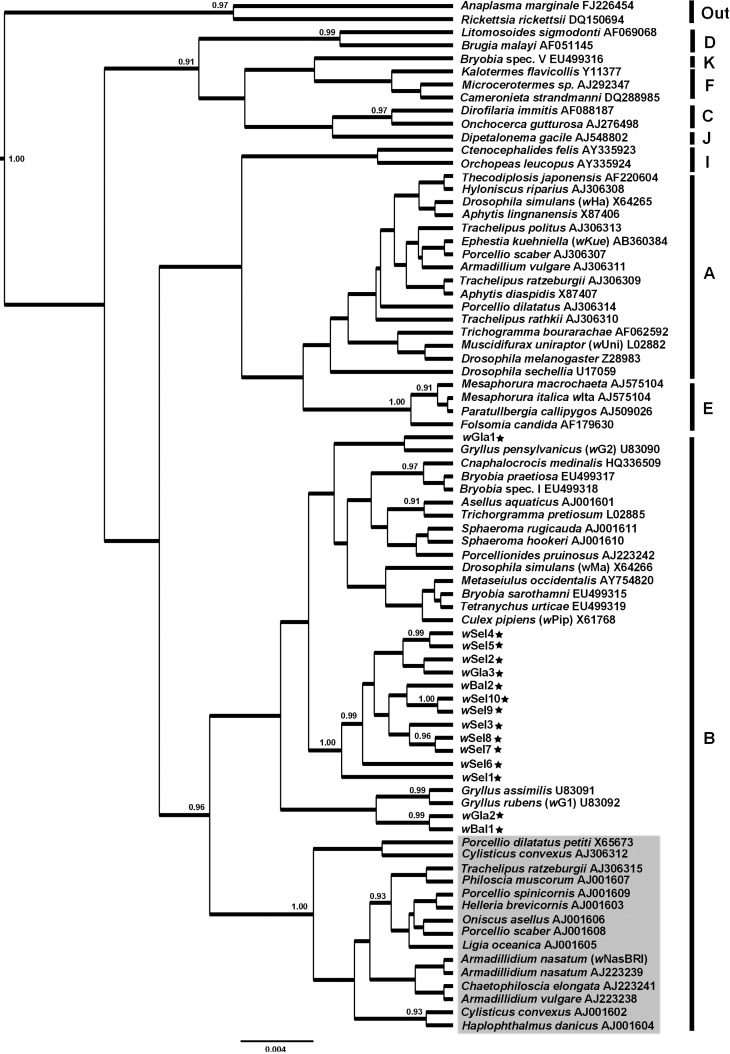

Phylogenetic relationship of 16S rDNA Wolbachia sequences

The inferred phylogenetic relationship among Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences found in this study and from other hosts is shown in Figure 2 together with the Bayesian posterior clade probabilities (PCP). This analysis suggested that Balloniscus Wolbachia sequences group in Supergroup B, in agreement with previous results obtained from other species of terrestrial isopods (Bouchon et al., 1998, Cordaux et al., 2001, Wiwatanaratanabutr et al., 2009). However, they fell outside the classical terrestrial isopod subclade named Oni clade (which was recovered with Bayesian PCP of 1.00 in this study) (Cordaux et al., 2001).

Figure 2.

Bayesian tree constructed based on partial 16S rDNA sequences of Wolbachia from Balloniscus species (denoted with stars) and another 16S rDNA from Wolbachia supergroups. Bayesian PCP values are shown (only those above 0.90). Names the host arthropod species followed by Wolbachia strain name and an accession number denotes the specific Wolbachia strain. Letters A–F denote Wolbachia supergroups; out: outgroup. Grey square: Oni clade.

Wolbachia sequences from Balloniscus grouped in three different positions in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 2): twelve Wolbachia sequences (wSel1, wSel2, wSel3, wSel4, wSel5, wSel6, wSel7, wSel8, wSel9, wSel10, wGla3 and wBal2) formed a cluster with Bayesian PCP 1.00; alternatively, wGla2 and wBal1 formed a small cluster with Bayesian PCP 0.99; while wGla1 did not group with any other sequence with high support. Interestingly, the Wolbachia sequences obtained from Balloniscus species did not form a monophyletic group, which could be indicative of multiple infections occurring throughout the history of these species.

When compared to an alternative topology where all Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences from Balloniscus were forced into a monophyletic clade the unconstrained topology (non-monophyly hypothesis) was supported by the Bayes factor analysis by a log10BF of 2.033, which is considered to be strong evidence in favor of a hypothesis. This value can be understood intuitively as a support of ∼108:1 in favor of the unconstrained topology. The scenario of multiple infections was also supported in the median-joining network (Supplementary Material Figure S1), since Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences from Balloniscus were mixed with other sequences found in different species, in such a way that forcing their monophyly would necessarily invoke a number of recurrent mutations. Notably, none of the analyses suggest that the sequences infecting each Balloniscus species form a monophyletic group, even when only species-specific Wolbachia sequences are taken into account.

Discussion

Wolbachia is a maternally inherited endosymbiont, common to several species of terrestrial isopods (Bouchon et al., 1998, 2008; Cordaux et al., 2001, Nyrö et al., 2002; Ben Afia Hatira et al., 2008; Wiwatanaratanabutr et al., 2009) and infecting North African, North American, Southeast Asia and European populations. This study presents the first record of Wolbachia occurrence in South American species of terrestrial isopods, and shows the highest sequence diversity previously found among terrestrial isopods for the Wolbachia 16S rDNA gene.

Wolbachia prevalence

Overall, B. sellowii was, on average, less infected than B. glaber. A possible explanation for this is an older co-evolutionary history with B. sellowii, which therefore would have more protection mechanisms against Wolbachia infection. This explanation is supported by our phylogenetic analyses, indicating that B. sellowii is a less fortuitous host, being infected by more genetically related lineages of Wolbachia.

For two populations (ABE, 6 and PEL, 1), where B. sellowii and B. glaber were sympatric, we could not detect infection by Wolbachia in any specimen. In addition, Wolbachia was not found in two other B. sellowii populations (PAL, 12 and CSU, 7). At least two non-exclusive hypotheses can explain this pattern. Either Wolbachia infection did not reach these populations or some evolutionary mechanisms are keeping Wolbachia prevalence at a very low level (decreasing the probability of sampling Wolbachia infected specimens). In the first case, the absence of migration between infected and uninfected population may prevent infection. The second case involves several potential factors. For example, environmental conditions (Keller et al., 2004), deficiency in vertical transmission (Rigaud and Juchault, 1992), competition between Wolbachia strains or with other elements (parasites or genetic factors), time of the Wolbachia invasion (Shoemaker et al., 2003), or stochastic demographic factors (Rigaud and Juchault, 1992, Jansen et al., 2008) which can slow down the spread of Wolbachia within and across populations, or even exclude the reproductive parasites from some host populations. Horizontal transfers from one species to the other, although rare when compared to migrations, can partly counterbalance some of the factors previously discussed. An interesting observation was the high variation in Wolbachia prevalence resulting from intragenomic conflict between different sex distorters reported in some European populations (Bouchon et al., 2008). As this was the first attempt to detect Wolbachia infection in Brazilian Oniscidea, understanding the role of such numerous factors will require much future efforts.

Genetic diversity and phylogeny of Wolbachia sequences

Some recent studies used a multiple-gene PCR and sequencing approach for the detection and characterization of Wolbachia lineages (Ros et al., 2009). Even though our findings are only based on the Wolbachia 16S rDNA gene, this marker has been widely used to detect the presence of Wolbachia and assess the level of polymorphism of its lineages (e.g. Werren et al., 1995b; Bouchon et al., 1998; Vandekerckhove et al., 1999; Rowley et al., 2004; Bordenstein and Rosengaus, 2005). However, because of the limitations of characterizing Wolbachia strains based on only one gene we did not consider sequences as true “strains”, and other assays must be performed to resolve this issue.

Nonetheless, because the 16S rDNA gene is less polymorphic than other markers, such as wsp (Schulenburg et al., 2000), the genetic diversity of the sequences found in Balloniscus is very impressive and higher than that observed in Wolbachia 16S lineages isolated from European species. For example, the mean Wolbachia sequence divergence found for the genus Balloniscus was comparable to that for Wolbachia sequences from all species of European terrestrial isopods (Table 2). Also, the AMOVA results suggested that the genetic diversity of the parasite is not obviously limited by the specific barriers of its host. Processes like horizontal Wolbachia transmission between Balloniscus species and/or multiple infections from other arthropod hosts may play some role in preventing a clear relationship between the phylogeny of the host species and Wolbachia. These findings would suggest a different co-evolutionary history between terrestrial isopods and Wolbachia from South America and Europe.

The phylogenetic analysis showed that Wolbachia sequences from Balloniscus were grouped outside the Oni clade, corroborating previous findings of terrestrial isopod species (one in Europe and two in Asia) where Wolbachia lineages were also found outside this clade (Cordaux et al., 2001; Nyrö et al., 2002; Wiwatanaratanabutr et al., 2009). A Wolbachia sequence from A. nasatum, a European species which was introduced to South America, was found in one individual of BRI (5). This sequence was identical to the one found in French populations of this species. Studies from other introduced species also showed that their Wolbachia were carried during introduction (Zimmermann et al., unpublished data). These results suggest that Wolbachia followed independent evolutionary trajectories in South America and Europe and corroborates the idea that Wolbachia spread differently within each host clade, according to geographic regions (Wiwatanaratanabutr et al., 2009).

Concerning the origins of the Wolbachia in Balloniscus, the monophyly of these sequences has not been supported based on Bayes Factor (BF). The BF is calculated by integrating the parameter space and tree space and provides an intuitive way of contrasting alternative hypotheses in a Bayesian framework (Suchard et al., 2005). However, estimating BF based on posterior samples drawn from MCMC phylogenetic algorithms is not easy, and some caution is needed when interpreting this result. Nonetheless, the median-joining network (Figure S1) clearly supported the notion that forcing the monophyly for Wolbachia lineages from Balloniscus would result in a scenario which is less consistent with these data.

In conclusion, like other South American arthropods (Shoemaker et al., 2000; Ciociola Jr et al., 2001; Ono et al., 2001; Selivon et al., 2002; Vega et al., 2002; Dittmar and Whiting, 2004; Heukelbach et al., 2004; Rocha et al., 2005; Cônsoli and Katajima, 2006; Souza et al., 2009), Wolbachia also infects South American terrestrial isopods. The population-based approach we took allowed a more accurate estimation of prevalence rates in these species, and permitted the discovery of a high genetic diversity of Wolbachia isolates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Debenest, Carine Delaunay, and Maryline Raimond for technical assistance and two anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions on a previous version of the manuscript. We also thank CAPES for the grant to AMP and the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Genética e Biologia Molecular-UFRGS.

Supplementary Material

The following online material is available for this article:

Figure S1 - Median-joining network of Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences from Balloniscus species.

This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.scielo.br/gmb.

References

- Araujo PB, Buckup L, Bond-Buckup G. Isópodos terrestres (Crustacea, Oniscidea) de Santa Catarina e Rio Grande do Sul. Iheringia. 1996;81:111–138. [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, Bordenstein S, Wernegreen JJ, Werren JH. Widespread recombination throughout Wolbachia genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006a;23:437–449. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, Hotopp JCD, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, Hayashi C, Maiden MCJ, Tettelin H, Werren JH. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006b;72:7098–7110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00731-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, Werren JH. Revisiting Wolbachia supergroup typing based on wsp: Spurious strains and discordance with MLST. Curr Microbiol. 2007;55:81–87. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-0055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt HJ, Macaulay V, Richards M. Median Networks: Speedy construction and greedy reduction, one simulation, and two case studies from human mtDNA. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2000;16:8–28. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2000.0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi C, Anderson TJ, Genchi C, Blaxter ML. Phylogeny of Wolbachia in filarial nematodes. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1998;265:2407–2413. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi C, Slatko B, O’Neill SL. Wolbachia genomes and the many faces of symbiosis. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:428–429. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01543-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Afia Hatira H, Charfi Cheikhrouha F, Bouchon D. Wolbachia in terrestrial isopods in Tunisia. In: Zimmer M, Charfi-Cheikhrouha F, Taiti S, editors. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Terrestrial Isopod Biology. Shaker Verlag; Aachen: 2008. pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein S, Rosengaus RB. Discovery of a novel Wolbachia super group in Isoptera. Curr Microbiol. 2005;51:393–398. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchon D, Rigaud T, Juchault P. Evidence for widespread Wolbachia infection in isopod crustaceans: Molecular identification and host feminization. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1998;265:1081–1090. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchon D, Cordaux R, Grève P. Feminizing Wolbachia and the evolution of sex determination in isopods. In: Bourtzis K, Miller T, editors. Insect Symbiosis. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2008. pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Breeuwer JAJ, Werren JH. Microorganisms associated with chromosome destruction and reproductive isolation between two insect species. Nature. 1990;346:558–560. doi: 10.1038/346558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciociola AI, Jr, Almeida RP, Zucchi RA, Stouthamer R. Detecção de Wolbachia em uma população telítoca de Trichogramma atopovirilia Oatman and Platner (Hymenoptera, Trichogrammatidae) via PCR com o primer específico wsp. Neotrop Entomol. 2001;30:489–491. [Google Scholar]

- Cônsoli FL, Katajima EW. Symbiofauna associated with the reproductive system of Cotesia flavipes and Doryctobracon areolatus (Hymenoptera, Braconidae) Braz J Morphol Sci. 2006;23:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JM, Butcher RDJ. The transmission and effects of Wolbachia bacteria in parasitoids. Res Pop Ecol. 1999;41:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R, Michel-Salzat A, Bouchon D. Wolbachia infection in crustaceans: Novel hosts and potential routes for horizontal transmission. J Evol Biol. 2001;14:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R, Michel-Salzat A, Frelon-Raimond M, Rigaud T, Bouchon D. Evidence for a new feminizing Wolbachia strain in the isopod Armadillidium vulgare: Evolutionary implications. Heredity. 2004;93:78–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar K, Whiting MF. New Wolbachia endosymbionts from nearctic and neotropical fleas (Siphonaptera) J Parasitol. 2004;90:953–957. doi: 10.1645/GE-186R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Ho SYW, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biology. 2006;4:699–710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Smouse P, Quattro J. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: Application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics. 1992;131:479–491. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin ver. 3.1: An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Heukelbach J, Bonow I, Witt LH. High infection rate of Wolbachiaendobacteria in the sand flea Tunga penetrans from Brazil. Acta Trop. 2004;92:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia? A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst GDD, Jiggins FJ, Schulenburg J, Bertrand D, West SA, Goriacheva II, Zakharov IA, Werren JH, Stouthamer R, Majerus MEN. Male-killing Wolbachia in two species of insect. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1999;266:735–740. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen VAA, Turelli M, Godfray HCJ. Stochastic spread of Wolbachia. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2008;275:2769–2776. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juchault P, Frelon M, Bouchon D, Rigaud T. New evidence for feminizing bacteria in terrestrial isopods: Evolutionary implications. C R Acad Sci III. 1994;317:225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Keller GP, Windsor DM, Saucedo JM, Werren JH. Reproductive effects and geographical distributions of two Wolbachia strains infecting the Neotropical beetle, Chelymorpha alternans Boh. (Chrysomelidae, Cassidinae) Mol Ecol. 2004;13:2405–2420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiggins FM, van der Schulenburg JHG, Hurst GDD, Majerus MEN. Recombination confounds interpretations of Wolbachia evolution. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2001;268:1423–1427. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand JJ, Juchault P. Modification expérimentale de la proportion des sexes chez les crustacés isopodes terrestres: Induction de la thélygénie chez Armadillidium vulgare Latr. C R Acad Sci III. 1970;270:706–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos de Castro A. Considerações sobre a sinonímia e a distribuição geográfica de Balloniscus sellowii (Brandt, 1833) (Isopoda, Balloniscidae) Rev Bras Biol. 1976;36:392–391. [Google Scholar]

- Li ZX, Lin HZ, Guo X. Prevalence of Wolbachia infection in Bemisia tabaci. Curr Microbiol. 2007;54:467–471. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-0011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo N, Casiraghi M, Salati E, Bazzocchi C, Bandi C. How many Wolbachia supergroups exist? Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:341–346. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo N, Paraskevopoulos C, Bourtzis K, O’Neill SL, Werren JH, Bordenstein SR, Bandi C. Taxonomic status of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia pipientis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:654–657. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Williamson C, Posada D. RDP2: Recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:260–262. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morellato LPC, Haddad CFB. Introduction: The Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Biotropica. 2000;32:786–792. [Google Scholar]

- Moret Y, Juchault P, Rigaud T. Wolbachia endosymbiont responsible for cytoplasmic incompatibility in a terrestrial crustacean: Effects in natural and foreign hosts. Heredity. 2001;86:325–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyrö G, Oravecz O, Márialigeti K. Detection of the Wolbachia pipientis infection in arthropods in Hungary. Eur J Soil Biol. 2002;38:63–66. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SL, Karr TL. Bidirectional cytoplasmic incompatibility between conspecific populations of Drosophila simulans. Nature. 1990;348:178–180. doi: 10.1038/348178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SL, Giordano R, Colbert AME, Karr TL, Robertson HM. 16S rDNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;94:2699–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SL, Hoffmann AA, Werren JH. Influential Passengers: Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction. Oxford University Press; New York: 1997. p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Braig HR, Munstermann LE, Ferro C, O’Neill SL. Wolbachia infections of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) J Med Entomol. 2001;38:237–241. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevopoulos C, Bordenstein SR, Wernegreen JJ, Werren JH, Bourtzis K. Toward a Wolbachia multilocus sequence typing system: Discrimination of Wolbachia strains present in Drosophila species. Curr Microbiol. 2006;53:388–395. doi: 10.1007/s00284-006-0054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadros AF, Caubet Y, Araujo PB. Life history comparison of two terrestrial isopods in relation to habitat specialization. Acta Oecol. 2009;35:243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Riegler M, O’Neill SL. The genus Wolbachia. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrand E, editors. The Prokaryotes. 1st edition. Springer Science; New York: 2006. pp. 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud T, Juchault P. Genetic control of the vertical transmission of a cytoplasmic sex factor in Armadillidium vulgare Latr. (Crustacea, Oniscidea) Heredity. 1992;68:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud T, Bouchon D, Souty-Grosset C, Raimond R. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism, sex ratio distorters and population genetics in the isopod Armadillidium vulgare. Genetics. 1999;152:1669–1677. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha LS, Mascarenhas RO, Perondini ALP, Selivon D. Occurrence of Wolbachia in Brazilian samples of Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Diptera, Tephritidae) Neotrop Entomol. 2005;34:1013–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Ros VID, Fleming VM, Feil EJ, Breeuwer AJ. How diverse is the genus Wolbachia? Multiple-gene sequencing reveals a putatively new Wolbachia supergroup recovered from spider mites (Acari, Tetranychidae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1036–1043. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01109-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SM, Raven RJ, McGraw EA. Wolbachia pipientis in Australian spiders. Curr Microbiol. 2004;49:208–214. doi: 10.1007/s00284-004-4346-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg JHGVD, Hurst GDD, Huigens TME, van Meer MMM, Jiggins FM, Majerus MEN. Molecular evolution and phylogenetic utility of Wolbachia ftsZ and wsp gene sequences with special reference to the origin of male-killing. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:584–600. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selivon D, Perondini ALP, Ribeiro AF. Wolbachia endosymbiont in a species of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera, Tephritidae) Invert Reprod Dev. 2002;42:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker DD, Ross KG, Keller L, Vargo EL, Werren JH. Wolbachia infections in native and introduced populations of fire ants (Solenopsis spp.) Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:661–673. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker DD, Keller G, Ross KG. Effects of Wolbachia on mtDNA variation in two fire ant species. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:1757–1771. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza RF, Ramalho JDS, Morini MSC, Wolf JLC, Araújo LC, Mascara D. Identification and characterization of Wolbachia in Solenopsis saevissima fire ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in southeastern Brazil. Curr Microbiol. 2009;58:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer R. Wolbachia-induced parthenogenesis. In: O’Neill SL, Hoffman AA, Werren JH, editors. Influential Passengers: Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction. Oxford Univerity Press; New York: 1997. pp. 102–124. [Google Scholar]

- Suchard M, Weiss RE, Sinsheimer JS. Models for estimating Bayes factors with applications to phylogeny and tests of monophyly. Biometrics. 2005;61:665–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The Clustal X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomazelli LJ, Dillemburg SR, Villwock JA. Late quaternary geological history of Rio Grande Sul coastal plain, southern Brazil. Rev Bras Geoci. 2000;30:470–472. [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerckhove TMT, Watteyne S, Willems A, Swings JG, Mertens J, Gillis M. Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rDNA of the cytoplasmic bacterium Wolbachia from the novel host Folsomia candida (Hexapoda, Collembola) and its implications for wolbachial taxonomy. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer MMM, Witteveldt J, Stouthamer R. Phylogeny of the arthropod endosymbiont Wolbachia based on the wsp gene. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8:399–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.83129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega FE, Benavides P, Stuart JA, O’Neill SL. Wolbachia infection in the coffee berry borer (Coleoptera, Scolytidae) Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2002;95:375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Verne S, Jonhson M, Bouchon D, Grandjean F. Effects of parasitic sex-ratio distorters on host genetic structure in the Armadillidium vulgare-Wolbachia association. J Evol Biol. 2011;25:264–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werren JH, Windsor DM, Guo L. Distribution of Wolbachia among Neotropical arthropods. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1995a;262:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Werren JH, Zhang W, Guo L. Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia: Reproductive parasites of arthropods. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1995b;261:55–71. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiwatanaratanabutr I, Kittayapong P, Caubet Y, Bouchon D. Molecular phylogeny of Wolbachia strains in arthropod hosts based on groE-homologous gene sequences. Zool Sci. 2009;26:171–177. doi: 10.2108/zsj.26.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zchori-Fein E, Gottlieb Y, Kelly SE, Brown JK, Wilson JM, Karr TL, Hunter MS. A newly discovered bacterium associated with parthenogenesis and a change in host selection behavior in parasitoid wasps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12555–12560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221467498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- RDP (Ribosomal Database Project), http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/ (accessed September 15, 2011).

- Network version 4.610 software, http://www.flux-us-engineering.com/sharenet.htm (accessed October 10, 2011).

- Beast (Bayesian evolutionary analysis sampling trees) version 1.7.4 software, http://evolve.zoo.ox.ac.uk/beast/ (accessed September 10, 2011).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 - Median-joining network of Wolbachia 16S rDNA sequences from Balloniscus species.