Abstract

Self-renewal and pluripotency are hallmark properties of pluripotent stem cells, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and iPS cells. Previous studies revealed the ESC-specific core transcription circuitry and showed that these core factors (e.g., Oct3/4, Sox2, and Nanog) regulate not only self-renewal but also pluripotent differentiation. However, it remains elusive how these two cell states are regulated and balanced during in vitro replication and differentiation. Here, we report that the transcription elongation factor Tcea3 is highly enriched in mouse ESCs and plays important roles in regulating the differentiation. Strikingly, altering Tcea3 expression in mouse ESCs did not affect self-renewal under non-differentiating condition; however, upon exposure to differentiating cues, its overexpression impaired in vitro differentiation capacity, and its knockdown biased differentiation towards mesodermal and endodermal fates. Furthermore, we identified Lefty1 as a downstream target of Tcea3 and show that the Tcea3-Lefty1-Nodal-Smad2 pathway is an innate program critically regulating cell fate choices between self-replication and differentiation commitment. Together, we propose that Tcea3 critically regulates pluripotent differentiation of mouse ESCs as a molecular rheostat of Nodal-Smad2/3 signaling.

Keywords: Tcea3, Lefty1, pSmad2, pluripotency, self-renewal, mouse embryonic stem cells

Introduction

Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) are prototypical pluripotent cells with the potential to indefinitely self-renew and differentiate into all three germ layers 1, 2. During the last decade, numerous studies have demonstrated that multiple signaling pathways (e.g., leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), BMP/TGF-β, and Wnt) and core transcription factors (e.g., Oct3/4, Sox2, and Nanog) regulate the unique identity of ESCs 3-10. To maintain the proper ESC state, it is critical for ESCs to have an innate program of self-renewal while retaining their differentiation potential. Remarkably, ESC-specific core transcription factors appear to regulate not only self-renewal but also differentiation. For instance, in mESCs varying levels of Oct3/4 and/or Nanog were shown to determine cell fate decisions 11, 12.

In addition, critical signaling pathways have been identified to regulate the transition of ESCs from self-renewal to multi-lineage commitment, including the fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4)-extra signal-related kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2) cascade 13, 14, glycogen synthase kinase-3 15 and the calcineurin-NFAT signaling 16. Another key pathway is Nodal-Smad2 signaling which critically regulates mesoderm and endoderm lineage commitment during in vivo early development 17, 18 and in vitro mESC differentiation 19, 20. These results predict that Nodal-Smad2/3 signaling must be critically regulated to ensure proper allocation to downstream cell fates.

In the present study, we found that a transcription elongation factor Tcea3, but not its homologs Tcea1 or 2, is highly expressed in ESCs and rapidly disappears during differentiation, suggesting a functional role in the control of self-renewal and/or pluripotent differentiation potential. Strikingly, altered expression of Tcea3 does not directly influence self-renewal or induce differentiation under non-differentiating conditions, but critically regulates their differentiation upon exposure to differentiation signals. Furthermore, we identified Lefty1, an inhibitor of Nodal, a member of the TGF-β family, as a downstream target of Tcea3 and we show evidence that this Tcea3 acts as a molecular rheostat to precisely control Smad2/3 signaling and maintain a balanced pluripotent potential during the transition from self-renewal to differentiation commitment.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, EB formation, and in vitro differentiation of mESCs

J1 mESCs (Cat # SCRC-1010) were purchased from ATCC (www.atcc.org). mESCs were maintained as described previously 21. Briefly, mESCs were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (HyClone), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine (Gibco) and 1000 U/ml LIF (Chemicon). To induce mESC differentiation, mESCs were cultured in LIF-deficient ESC medium (as described above) with 100 nM all-trans RA. To form EBs, mESCs were trypsinized to achieve a single-cell suspension and subsequently cultured on uncoated Petri dishes in ESC medium without LIF. Media were changed every two days for mESC culture or differentiation. Alkaline phosphatase activity was measured by using EnzoLyte™ pNPP Alkaline Phosphatase Assay kit (AnaSpec: #71230), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Activin-induced mesendoderm differentiation was performed as previously described 19. Briefly, ESCs were cultured as monolayer in gelatinized feeder-free six-well plates with the initial plating density of 1 × 105 cells/well and the time when 25 ng/ml Activin is added was counted as day 0. The medium was composed of 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with N2 supplement (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and NeuralBasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 supplement (Stem Cell Technologies) and with β-mercaptoethanol. Neuroectoderm differentiation was performed as previously described 22. Briefly, undifferentiated mESCs were dissociated and plated into 0.1% gelatin-coated tissue culture dishes at a density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 in N2B27 medium. Medium was renewed every 2 days. N2B27 is a 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with modified N2 (25 μg/ml insulin, 100 μg/ml apo-transferrin, 6 ng/ml progesterone, 16 μg/ml putrescine, 30 nM sodium selenite and 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin fraction V) and NeuralBasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 supplement (Stem Cell Technologies). Cells were harvested at day 4 for gene expression analysis.

Genetic modification of mESCs

Five Tcea3 overexpressing mES cell lines were generated by stable transfection of Tcea3-expressing plasmid, which was constructed by cloning PCR-amplified cDNA of Tcea3 into modified pcDNA3.1 vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), of which CMV promoter was replaced to EF1α promoter. A shRNA plasmid targeting mouse Tcea3 was purchased (RMM3981-97073145, Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL) to generate five stable knockdown cell lines of Tcea3. siRNAs targeting nonspecific genes were purchased from Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea) and siRNAs targeting Tcea3 or Lefty1 were purchased from Dharmacon (Denver, CO). siRNA or plasmid were transfected into mESCs with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and stably transfected lines were established following the manufacturer's instructions. These multiple stable lines as well as transient expression analyses showed very consistent results although we presented most representative data.

SuperArray analysis

A group of 111 genes previously shown by microarray analyses to be differentially up- or down-regulated during oocyte maturation were used to produce Custom Oligo SuperArrays by Superarray Bioscience Corporation (Bethesda, MD) (Fig. S1). We then compared relative mRNA expression of these genes in mouse GV and MII oocytes, mESCs, MEFs and NIH3T3 cells according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was purified from GV and MII oocytes, mESCs, MEF and NIH3T3 cells with ArrayGrade™ Total RNA Isolation Kit (Superarray Bioscience Corporation). cRNA was synthesized and labeled with biotinylated-UTP and TrueLabeling-AMP™ 2.0 (Superarray Bioscience Corporation) following the manufacturer's instructions. Image analysis and data acquisition were performed using the Web-based integrated GEArray Expression Analysis Suite provided by SuperArray Bioscience. We used the means of housekeeping genes to normalize the intensities of the hybridization signals.

Fluorescence-based competition assay

Fluorescence-based competition assay was performed as previously described 23. GFP-expressing mESCs were generated by chromosomal integration of EGFP-expressing plasmid DNA. Tcea3OE or Tcea3KD cells were mixed with GFP-expressing mESCs at a ratio of 1:1 and plated into the gelatinized wells of 6 well plates. Every 48 hours (one passage) cells were trypsinized and re-plated. At each passage, the proportion of GFP+/GFP- cells was measured by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur using CellQuest data analysis software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Analyses were carried out for 6 consecutive passages.

Secondary EB formation

ES cells were differentiated into primary EBs in vitro in ESC medium without LIF. After 4 days, the resulting EBs were collected and dissociated into single cells by trypsinization and passaged through trituration. These EB cells were replated into ESC medium without LIF and the efficiency of secondary EB production was assessed after 10 days, to determine the proportion of undifferentiated mESCs in primary EBs.

Immunocytochemical staining

Immunocytochemical staining was performed as described 24. Rabbit anti-mouse Oct4 antibody at 1:200 and Alexa Fluor 488- (A21206, Molecular Probes) or Alexa Fluor 594-labeled anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (A21207, Molecular Probes) at 1:300 dilutions were used to detect Oct4 in the cells. For Tcea3 detection, the anti-mouse Tcea3 antibody at 1:300 and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) at 1:300 dilution.

Microarrays

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and biotinylated cRNA were prepared from 0.55 μg total RNA using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) following the manufacturer instructions. Following fragmentation, 1.5 μg of cRNA were hybridized to the Illumina Mouse WG-6 Expression Beadchip according to the manufacturer's instructions (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). Arrays were scanned with an Illumina Bead Array Reader Confocal Scanner according to the Manufacturer's instructions. Array data processing and analysis were performed using Illumina BeadStudio v3.1.3 (Gene Expression Module v3.3.8).

Teratoma formation

For teratoma formation assay, cells were trypsinized, and 5 × 105 cells were suspended in a DMEM/Matrigel solution (BD Biosciences Inc) (1:1 ratio (v/v)). The cell suspension was then injected subcutaneously into NOD/SCID mice (Charles River Laboratories, Yokohama, Japan). Teratoma formation was examined for eight weeks after injection.

GST pull down assay

Tcea3 was cloned into pGEX-4T1 (Addgene, Cambridge, MA). For bait protein preparation, approximately 20 mg of GST fusion Tcea3 were prepared in 5 ml PBS and incubated with 100 μl of glutathione-beads for 1 hr at 4 °C. After three washing steps with PBS supplemented with 15% glycerol and 0.5% triton X-100, beads were suspended in 500 μl of PBS. For GST-pull-down assays, 500 μl of glutathione-beads coupled with GST-Tcea3 were incubated for 4 hrs at 4 °C with 500 μl of PBS or mESC total lysate. After three washing steps with PBS supplemented with 15% glycerol and 0.5% triton X-100, beads were suspended in 40 μl of 1X SDS loading buffer. After boiling, 20 μl of samples were analyzed on 10% SDS-PAGE.

Identification of Tcea3 binding proteins

Gel bands were excised and reduced with DTT and alkylation with indole-3 acetic acid (IAA) before each gel band was treated with trypsin to digest the proteins in situ 25. Peptides were recovered by two cycles of extraction with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 100% ACN. Lyophilized peptide samples were dissolved in mobile phase A for Nano-LC/ESI-MS/MS. Peptides were identified using MS/MS with a nano-LC-MS system consisting of a Nano Acquity UPLC system (Waters, USA) and a LTQFT mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, USA) equipped with a nano-electrospray source. To identify the peptides, the software MASCOT (version 2.1, Matrix Science, London, UK), operated on a local server, was used to search the IPI mouse protein database released by the European Bioinformatics Institute. MASCOT was used with monoisotopic mass or second monoisotopic mass selected (where one 13C carbon is considered), a precursor mass error of 100 ppm, and a fragment ion mass error of 1 Da. Trypsin was selected as the enzyme, with two potential missed cleavage. Oxidized methionine and carbamidomethylated cysteine, were chosen as variable and fixed modifications, respectively. Only proteins that were identified by two more high scoring peptides were considered to be true matches. The high scoring peptides corresponded to peptides that were above the threshold in our MASCOT search (expected <0.05, peptide score >38).

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from mESCs and teratoma was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and 2~5 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the SuperScriptII™ First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using cDNAs with Quantitect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reactions were carried out in triplicates using an Exicycler™ 96 real-time quantitative thermal block (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). For quantification, target genes were normalized against glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh). PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table S3.

Immunoblotting

For Immunoblotting assay, cells were washed twice with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), lysed with tissue lysis buffer (TLB; 20 mM Tris-base, pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1 mM benzamidine) and clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Whole-cell extracts were prepared and 20~50 μg of proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences; Boston, MA) and probed using antibodies against Tcea3 (sc-55782, Santa Cruz), Oct4 (sc-9081, Santa Cruz), pStat3 (Tyr-705) (#9131, Cell Signaling Technology), Nanog (sc-30328, Santa Cruz), Lefty1 (MAB994, R&D Systems), pSmad2 (#3101, Cell Signaling Technology), Smad2/3 (sc-8332, Santa Cruz), pSmad1/5 (#9516, Cell Signaling Technology), Smad5 (sc-7443, Santa Cruz), α-tubulin (sc-5286, Santa Cruz), and β-actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz). Immunoreactivity was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

The ChIP experiments were performed as previously described with modifications26. After crosslinking with 1% formaldehyde, frozen Wild type, Tcea3 OE, and Tcea3 KD cell pellets were suspended in 700 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes(pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml Pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml Aprotinin) and, using a Branson sonifier, sonicated on ice 5 times for 15 seconds each at 40% duty cycle, followed by 1 min pause. After centrifugation, supernatants were diluted with ChIP dilution buffer (16.7 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 167 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM EDAT, 1.1% Triton X-100) and pre-cleared with protein G conjugated agarose beads (16-201, Upstate). Pre-cleared chromatin samples were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of polyclonal Tcea3 antibody (SC-55782) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

To compare relative amounts of each amplified products for the ChIP experiment, genomic fragments of Lefty1 locus were amplified by real-time PCR and calculated according to the 2 ΔΔCT method27 and compared with those of controls. GAPDH was used as an internal endogenous control.

Statistical analysis

Graphical data are presented as means ± SD. Each experiment was performed at least three times and subjected to statistical analysis. Statistical significance between two groups and among three groups was determined using Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following the Scheffe test, respectively. A p value below 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS statistical package v.9.13 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

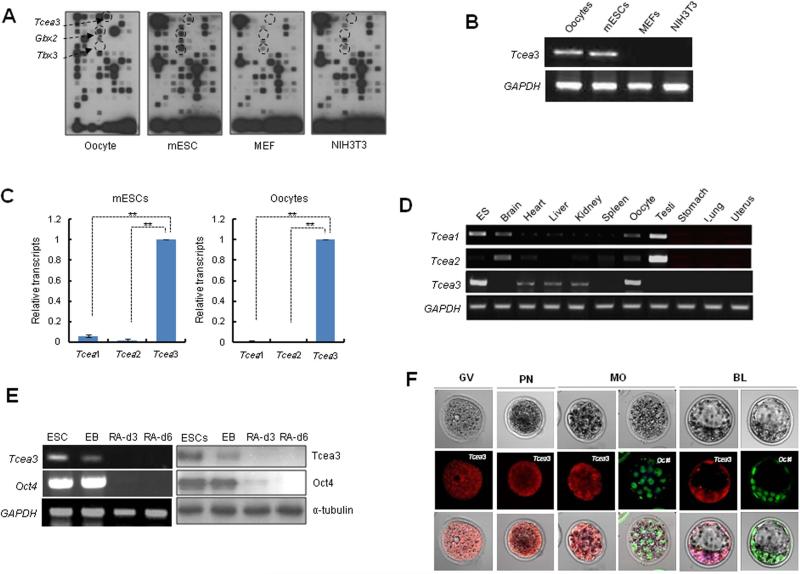

Transcription elongation factor Tcea3, but not Tcea1 or Tcea2, is predominantly expressed in mESCs and oocytes

Since both oocytes and ESCs have the unique ability to induce pluripotency 28, 29, we sought to identify novel pluripotency-regulating factors by comparing the specific gene expression patterns of oocytes, mESCs, and terminally differentiated tissues. Based on genome-wide transcriptome analysis of mouse oocytes during in vitro maturation 30; and data not shown), we generated a custom oligonucleotide array containing 111 genes dynamically expressed during oocyte maturation (Fig. S1). Hybridization analysis with total RNAs prepared from mouse oocytes, mESCs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), and NIH3T3 cells identified four genes that are specifically expressed in oocytes and/or ESCs, but not in MEF and NIH3T3 cells; Tbx3 and Gbx2, which are known markers of ESC pluripotency 31, 32 and Tcea3, which is only known as a transcription elongation factor (Fig. 1A). Specific expression pattern of Tcea3 was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Transcription elongation factor Tcea3 is predominantly expressed in undifferentiated mESCs, oocytes, and early embryos.

(A) Membrane array analysis was performed using total RNA samples from mouse oocytes, mESCs, MEFs, and NIH3T3 cells. The spots indicated by arrows correspond to Tcea3, Gbx2 and Tbx33. (B) RT-PCR analysis reveals that Tcea3 is expressed in mouse oocytes and ESCs but not in MEF and NIH3T3 cells. (C) Relative expression of Tcea1, Tcea2 and Tcea3 in mESCs and oocytes, as analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. (D) Analysis of mouse tissue-specific expression of Tcea1, Tcea2 and Tcea3 transcripts by RT-PCR of total RNA prepared from the indicated tissues. (E) Expression analyses of Tcea3 by RT-PCR from total RNA and immunoblotting of whole cell extracts from ESCs, EBs and in vitro differentiated cells at day 3 and 6, following LIF withdrawal and RA addition (RA-d3, RA-d6). GAPDH and α-tubulin were used as loading controls for RT-PCR or Western blot analysis, respectively. (F) Expression of Tcea3 in oocytes, fertilized eggs, and early stage mouse embryos by immunocytochemical staining.

All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. ** Indicates highly significant (P<0.01) results based on Student's T-test analyses.

Abbreviations: GV, germinal vesicle; PN, pronucleus; MO, morula; BL, blastocyst.

Tcea3 (also called SII-h or SII-K1) belongs to the TFIIS (SII) elongation factor subfamily, which comprise three SII genes in Xenopus, mouse, rat, and human 33. We next performed real time PCR analysis to compare expression of Tcea3 with those of other isoforms of the Tcea family, Tcea1 and Tcea2. As shown in Fig. 1C, expression of Tcea1 and Tcea2 was either undetectable or minimal in mESCs and oocytes. Tissue-specific expression of Tcea genes was further examined using mRNAs prepared from diverse tissues (Fig. 1D). As previously reported, Tcea2 transcripts are most abundant in testis 34. In addition, expression of Tcea3 is detected in heart, liver, and kidney 35, 36 but was more robust in mESCs and oocytes. Overall, our expression analysis confirmed that Tcea3 is most prominently expressed in ESCs and oocytes. Consistent with our results, analysis of large publicly available gene expression data sets identified Tcea3 as one of five biomarkers of the ESC state 37. Furthermore, Tcea3 has recently been found to be one of the common targets of multiple core transcription factors in mESCs and/or iPSCs 6, 8.

Next, we examined whether Tcea3 expression is altered during mESC differentiation in vitro. Indeed, following LIF withdrawal and retinoic acid (RA) addition, mRNA and protein expression levels of Tcea3 dramatically decreased during differentiation and became undetectable within 3 days, even faster than the rate observed for Oct4 (Fig. 1E). We also examined the expression pattern of Tcea3 during early embryo development by immunohistochemistry. As shown in Fig. 1F, we found that Tcea3 is prominently expressed in oocytes, fertilized pronuclear eggs, developing morula- and blastocyst-stage embryos. In contrast to Oct4, which is mainly localized in nucleus of morula and the inner cell mass of blastocyst, Tcea3 is localized in both nucleus and cytoplasm. Collectively, these data suggest that Tcea3 may regulate self-renewal and/or pluripotency and that it may function both in nucleus and cytoplasm.

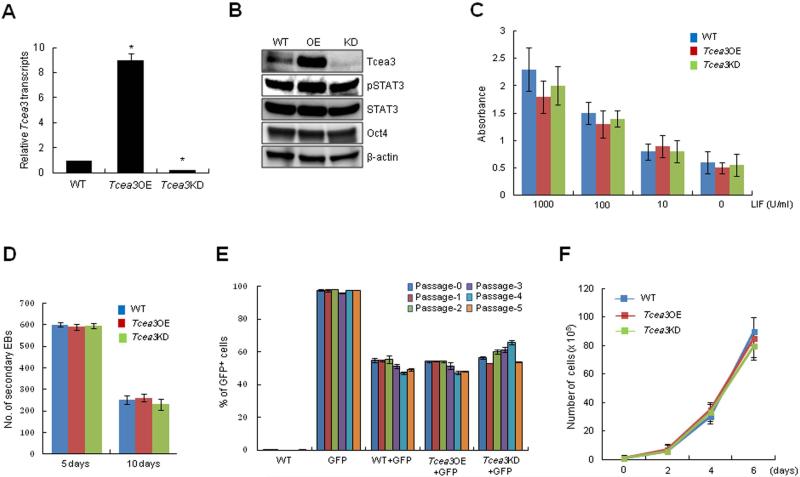

Tcea3 does not regulate self-renewal/proliferation of mESCs

To investigate the potential functional role of Tcea3, we established multiple mESC lines over-expressing (Tcea3 OE) or down-regulating Tcea3 (Tcea3 KD) (Fig. 2A, 2B). Functional effect of these changes on self-renewal was systematically examined. Neither overexpression nor knockdown of Tcea3 affected expression of two undifferentiated ESC markers, Oct3/4 and phosphorylated Stat3 (p-Stat3) (Fig. 2B); other ESC-specific transcription factors such as Sox2 and Nanog were unaltered as well (see below). To further investigate the effect of altering Tcea3 expression on self-renewal, we examined the LIF dependency of these cells by reducing LIF concentration in ES culture media (ranging from 1000 to 0 U). Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity, an indicator of the undifferentiated ESC state, gradually decreased in a dose dependent manner regardless of Tcea3 expression levels (Fig. 2C). The efficiency of secondary EB formation, which reflects mESCs’ ability to maintain an undifferentiated state 38, was comparable regardless of Tcea3 expression levels (Fig. 2D). In addition, we performed a fluorescence-based competition assay to compare the self-renewal capacity of mESCs 23. Wild type (WT) mESCs stably expressing GFP (GFP+) were mixed with GFP- cells (WT, Tcea3 OE or Tcea3 KD) at a 1:1 ratio, and the GFP+/GFP- ratio was measured at every passage. We found that regardless of Tcea3 expression levels the GFP+/GFP- ratio remained comparable up to five passages tested here (Fig. 2E). Finally, altered expression of Tcea3 did not have any effect on mESCs’ proliferation rate (Fig. 2F). Together, these data suggest that Tcea3 is not required for self-renewal/proliferation or expression of ESC marker genes under non-differentiating conditions.

Figure 2. Altered expression levels of Tcea3 do not affect self-renewal of mESCs.

(A) Tcea3 transcript levels were analyzed by realtime RT-PCR. (B) Protein expression of Tcea3, Oct4, and p-Stat3 was analyzed by immunoblot using cell extracts from WT, Tcea3 OE, and KD mESCs. (C) WT, Tcea3 OE and Tcea3 KD mESCs were maintained in different concentrations of LIF for 5 days and AP activity was measured. (D) 1st EBs from indicated cells were dissociated into single cells and re-seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in the same medium. The number of 2nd EB colonies was counted under light microscope. (E) GFP-positive (GFP+) mESCs were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 with GFP-negative (GFP-) WT, Tcea3 OE, and Tcea3 KD cells, respectively. The GFP+/GFP- ratios were measured at each passage. (F) Cell proliferation of WT, Tcea3 OE and Tcea3 KD mESCs was analyzed by counting cell number every 2 days under ESC culture condition. All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. * indicates significant (P<0.05) results based on Student's T-test analyses.

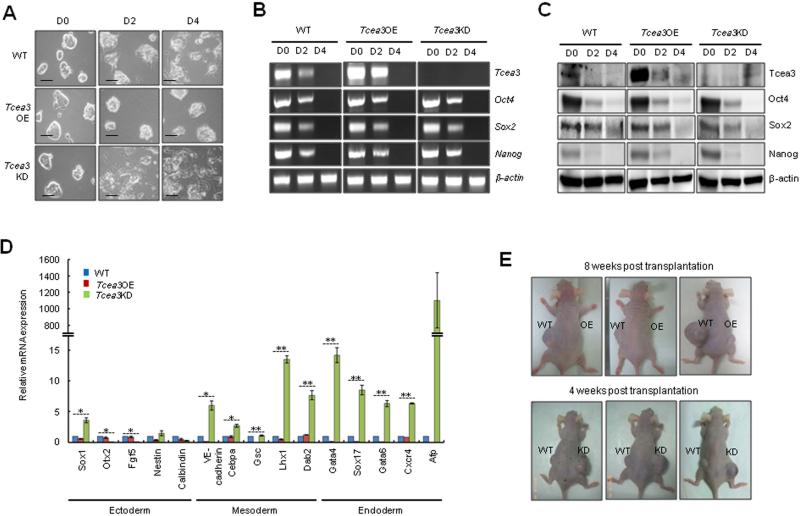

Tcea3 critically controls the differentiation potential of mESCs

We next investigated whether Tcea3 regulates the differentiation potential of mESCs under in vitro differentiation condition. As expected, upon removal of LIF and addition of RA, WT mESCs almost completely lost their typical morphology by day 2 and developed flattened epithelial-like outgrowth (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, Tcea3 OE cells were resistant to differentiation stimuli and maintained an undifferentiated mESC morphology even at day 4 following LIF removal and RA addition. In contrast, Tcea3 KD cells became flat and differentiated more rigorously and faster than WT mESCs. A possible mechanism is that Tcea3 regulates ESCs’ core transcription factors under differentiation condition, leading to their altered differentiation properties. To test this, we compared the pattern of core transcription factors such as Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog during in vitro differentiation. Remarkably, the pattern of gene expression changes for ESC markers (Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog) was almost identical during in vitro differentiation both at the RNA and protein levels regardless of Tcea3 expression levels (Fig. 3B, 3C), thus excluding the possibility that Tcea3 regulates in vitro differentiation via controlling expression of core transcription factors. We next examined and compared mRNA expression patterns for various lineage markers at day 4 following LIF withdrawal and RA treatment. The great majority of mesoderm and endoderm marker genes were markedly increased in Tcea3 KD cells whereas they were mostly downregulated in Tcea3 OE cells (Fig. 3D). In contrast, while Tcea3's influence on ectoderm marker genes varied depending on individual genes, there was a trend towards decreased activation of ectodermal genes in Tcea3 KD cells (Fig. 3D). Consistently, mesoderm and endoderm markers were significantly activated whereas ectoderm markers were decreased in Tcea3 KD cells differentiated into mesoendoderm or ectoderm lineage (Fig. S2).

Figure 3. Altered expression of Tcea3 influences multi-lineage differentiation potential of mESCs both in vitro and in vivo.

(A) In vitro differentiation was induced by removing LIF and adding RA to WT, Tcea3 OE, and KD mESCs. Cells were examined at day 0 (D0), day 2 (D2) or day 4 (D4) following in vitro differentiation. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) RT-PCR analysis of Tcea3, Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog expression during in vitro differentiation of WT, Tcea3 OE, and KD mESCs. (C) Immunoblot analysis of Tcea3, Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog expression during in vitro differentiation of WT, Tcea3 OE, and KD mESCs. (D) WT, Tcea3 OE, and KD mESCs differentiated for 4 days (RA-d4) were analyzed for the expression of markers representing ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm by real-time RT-PCR. The expression level of each gene was shown as relative value following normalization against that of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) gene. (E) WT, Tcea3 OE and Tcea3 KD cells were injected into NOD/SCID mice and teratoma development was examined. Teratoma formation of Tcea3 OE cells was compared with that of WT cells 8 weeks after injection and teratoma formation of Tcea3 KD cells was compared with that of WT cells 4 weeks after injection. This teratoma analysis was repeated twice with identical results (data not shown).

All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. * indicates significant(P<0.05) and ** highly significant (p<0.01) results based on ANOVA analyses following the Scheffe test.

We next injected equal numbers of Tcea3 OE, KD, or WT cells into SCID mice and monitored the extent of teratoma formation. As shown in Fig. 3E, Tcea3 OE-injected mice developed small or barely visible teratomas while mice injected with WT mESCs developed well-formed teratomas after 8 weeks. Interestingly, Tcea3 KD-injected mice developed teratomas more rapidly than mice injected with WT mESCs. Given that teratoma formation is an in vivo indicator of pluripotency, our results indicate that the enhanced multi-lineage differentiation potential of Tcea3 KD cells resulted in more rapid and robust teratoma formation and vice versa for Tcea3 OE cells. In line with this notion, recent studies showed that mESCs with enhanced multi-lineage differentiation potential either by overexpression of calcineurin-NFAT 16 or by knockdown of Tet1 enzyme 39 generated much bigger teratomas compared to WT mESCs. Furthermore, consistent with in vitro differentiation analyses, expression of all mesoderm and endoderm marker genes was prominently increased in teratomas generated by Tcea3 KD cells compared to those by wild type mESCs (Fig. S3).

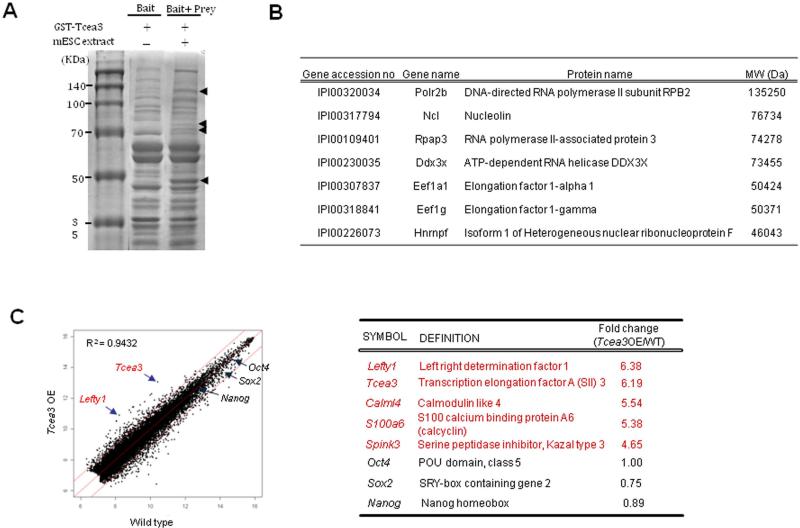

Tcea3 is a component of RNA polymerase II transcription complex in mESCs

Although Tcea3 (also called SII-h or SII-K1) is known to be a transcription elongation factor belonging to the TFIIS (SII) subfamily based on its homology with other members 35, 36, its biological function is unknown. To understand the function of Tcea3, we attempted to identify the binding proteins of Tcea3 in mESCs by GST pull down assay using GST-Tcea3 fusion protein. When mESC extracts were analyzed after the pull down, four distinct bands were evidently identified in the prey and bait lane compared to the bait only lane (Fig. 4A). We identified individual proteins corresponding to each band by mass spectrometric analysis. As shown in Fig. 4B and Table S1, components of transcription complex such as RNA polymerase II RPB2 and RNA polymerase II-associated protein were identified as Tcea3 binding partners, supporting that Tcea3 indeed functions as a transcription elongation factor in mESCs. Interestingly, two translation elongation factors (Eef1a1 and Eef1g) were also identified to be Tcea3 binding partners, suggesting that Tcea3 may have additional functional role(s) beyond transcriptional elongation. This is in line with our finding that expression of Tcea3 is detected not only in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm of early embryos (Fig. 1F). The functional significance of Tcea3's interaction with these factors awaits further investigation.

Figure 4. Tcea3 is a component of RNA polymerase II transcription complex and regulates expression of Lefty1 in mESCs.

(A) Agarose gel analysis of Tcea3 binding proteins from mESCs. mESC total cell extracts were used as “prey” and GST fused Tcea3 were used as “bait” for the GST pull down assay. (B) List of representative proteins identified as protein binding partners of Tcea3 by the mass spectrometric analysis of peptides extracted from four agarose bands of (A). (C) Scatter plots of cDNA microarray analysis of Tcea3 OE mESCs revealed that Lefty1 expression is most robustly upregulated (R2 = correlation coefficients).

We next sought to identify downstream target(s) of Tcea3 by comparing global gene expression profiles of Tcea3 OE with that of WT mESCs. Scatter plotting of Tcea3 OE cDNA microarrays showed that their gene expression profile was in general similar to that of WT mESCs (R2=0.9432) (Fig. 4C). However, of the 26,766 total genes on the MouseWG-6 v2 Expression BeadChip (Illumina, Inc), 359 genes were significantly altered in Tcea3 OE according to a Student's t-test with 99% confidence level (up: 155 genes, down: 204 genes) (Table S2).

Lefty1 is a downstream target of Tcea3 in mESCs

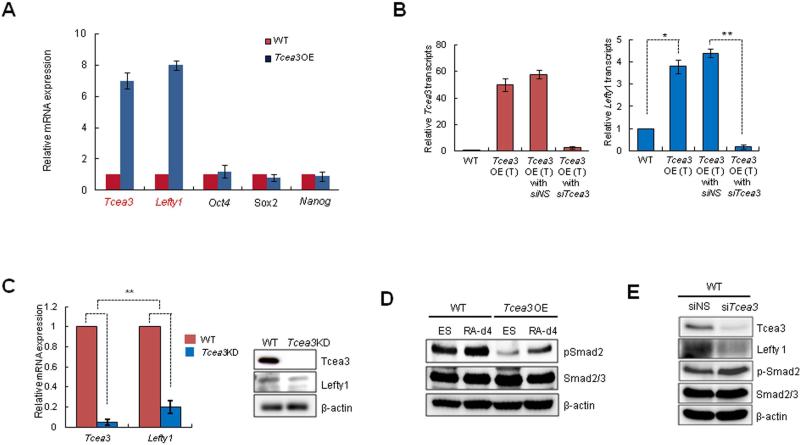

From the microarray analysis, we noticed that Lefty1 was most remarkably induced in Tcea3 OE while core transcription factors such as Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog were not significantly altered (Fig. 4C). These results were confirmed by qRT-PCR analyses using independently prepared mRNAs (Fig. 5A). In addition, the Tcea3-overexpressing vector was transiently co-transfected along with non-specific (siNS) or Tcea3-specific siRNAs (siTcea3), and Lefty1 gene expression monitored. As shown in Fig. 5B, the enhanced levels of Tcea3 and Lefty1 expression by the Tcea3-overexpressing vector were greatly reduced by siTcea3 treatment. Consistently, the expression levels of both Tcea3 and Lefty1 were lower in Tcea3 KD than WT, both at the RNA and protein levels (Fig. 5C). In support of this, chromatin immunoprecipitation assay showed that Tcea3 interacts with the transcription start site of the Lefty1 gene (Fig. S4). These results strongly suggest that Lefty1 is a downstream target of Tcea3.

Figure 5. Lefty1 is a downstream target gene of Tcea3.

(A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis confirms the microarray results. (B) Real-time RT-PCR analysis shows that transient transfection of Tcea3-expressing vector (Tcea3 OE (T)) dramatically induced Tcea3 (left) and Lefty1 (right) transcript expression and that co-transfection of Tcea3-specific siRNA reduced them. Non-specific siRNA (siNS) was transfected as control. The error bars correspond to three replicates (n=3) and show the mean ± s.d. (C) Lefty1 expression in Tcea3 KD mESCs compared with that of WT mESCs by qRT-PCR (left) and immunoblotting analysis (right). (D) Immunoblotting results of p-Smad2 in Tcea3 OE and WT mESCs at 0 (ES) or 4 days (RA-d4) during in vitro differentiation. β-actin was used as loading control. (E) Expression levels of Lefty1 and p-Smad2 were analyzed by immunoblotting after siRNA-mediated transient knockdown of Tcea3 in WT mESCs.

All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. * indicates significant (P<0.05) and ** highly significant (p<0.01) results based on Student's T-test analyses.

Abbreviation: siNS, non-specific siRNA; siTcea3, siRNA targeting to Tcea3; siLefty1, siRNA targeting to Lefty1.

Lefty1, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, is known to function as a negative regulator of Nodal signaling during embryogenesis 40-42, whereas Nodal/Activin signaling involves phosphorylation and activation of the effectors Smad2/3 17, 18, 43. Thus we investigated whether altered Tcea3 expression affects Smad2 phosphorylation. The levels of phosphorylated Smad2 (p-Smad2) in Tcea3 OE were significantly lower than in WT mESCs under both undifferentiated and RA-induced differentiation conditions (Fig. 5D). To rule out the possibility that these results are caused by unexpected mutations and/or adaptive responses of Tcea3 OE cells, we introduced small interfering RNA (siRNA) in WT mESCs to achieve transient Tcea3 knockdown and found that siRNA-induced Tcea3 knockdown caused suppression of Lefty1 and upregulation of p-Smad2 (Fig. 5E), further confirming our results using Tcea3 OE and KD cells. We also examined the effect of Tcea3 over-expression on the phosphorylation of Smad1/5 (p-Smad1/5) which is linked to BMP signaling 18. As shown in Fig. S5A, p-Smad1/5 levels appear to be comparable in Tcea3 OE cells. In addition, microarray analysis of Tcea3 OE cells showed that the expression levels of either BMP4 or BMP4 target genes such as ID1, ID2 and ID3 were unaffected (Fig. S5B). These results suggest that Tcea3 specifically regulates Nodal-Smad2 signaling without affecting BMP-Smad1/5 signaling. Consistently, when serum-starved WT or Tcea3 OE mESCs were stimulated with Nodal, the phosphorylation status of Smad1/5 was unaffected whereas phosphorylation of Smad2 was retarded in Tcea3 OE compared to WT mESCs (Fig. S5C). Since BMP signaling functions to maintain mESCs’ self-renewal 22, these results are consistent with our finding that Tcea3 does not affect the self-renewal capacity of mESCs.

Tcea3 controls the in vitro differentiation potential of mESCs by regulating the Lefty1 expression

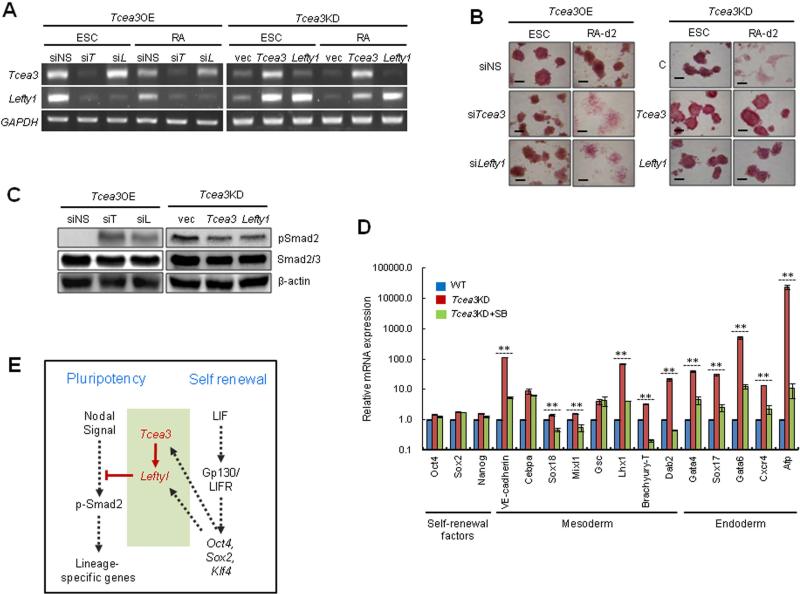

TGF-β signaling is known to play important roles in early embryogenesis and maintenance of ESC identities 41, 42, 44. Our results suggest that Tcea3 regulates Nodal signaling in mESCs through modulation of Lefty1 expression. To further explore this model, we transiently suppressed or overexpressed Tcea3 or Lefty1 in Tcea3 OE or Tcea3 KD mESCs by using siRNAs and expression vectors, respectively (Fig. 6A). We then examined whether alteration of Lefty1 could revert or rescue the effect of Tcea3 OE or KD on the differentiation capacity of mESCs. When non-specific siRNA was used, Tcea3 OE remained resistant to differentiation following RA treatment (Fig. 6B, left panel). However, following siRNA-mediated knockdown of Tcea3 or Lefty1 expression, Tcea3 OE regained their differentiation capacity, as examined by morphological changes and AP staining (Fig. 6B, left panel). In addition, transient expression of Tcea3 or Lefty1 rendered Tcea3 KD resistant to differentiation upon RA stimulation (Fig. 6B, right panel). Consistent with the phenotypic complementation results, siRNA mediated knockdown of Tcea3 or Lefty1 induced phosphorylation of Smad2 in Tcea3 OE and expression of Tcea3 or Lefty1 in Tcea3 KD resulted in dephosphorylation of Smad2 (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Tcea3 controls the in vitro differentiation potential of mESCs by regulating the Lefty1 expression.

(A) Tcea3 OE mESCs were transfected with siTcea3 or siLefty1 and transcript levels of Tcea3 and Lefty1 were analyzed by RT-PCR either at 0 or 2 days following in vitro differentiation (left). Tcea3 KD mESCs were transfected with Tcea3 or Lefty1 expressing plasmid and transcript levels were analyzed by RT-PCR (right). (B) Tcea3 OE mESCs were transfected with siTcea3 or siLefty1 and Tcea3 KD mESCs were transfected with Tcea3 or Lefty1 expressing plasmid. Differentiation was analyzed by morphological changes and AP staining. (C) Tcea3 OE mESCs were transfected with siRNA targeting Tcea3 or Lefty1 and Tcea3 KD mESCs were transfected with Tcea3 or Lefty1 expressing plasmids for 24 hr. Levels of pSmad2 were analyzed by immunoblotting. (D) Tcea3 KD mESCs were differentiated for 2 days by removing LIF and adding RA in the presence or absence of SB431542 (20 μM) and the expression of self-renewal factors or mesoendoderm marker genes were analyzed by RT-PCR. (E) A schematic diagram depicting the proposed role of the Tcea3-Lefty1-Nodal-Smad2 pathway controlling cell fate choices between self-renewal and differentiation commitment. Proper expression levels of Tcea3 appear to be critical for balancing the transition between these two cell fates. In addition, our model suggests that Tcea3 and Lefty1 importantly link these two cell fates by being regulated by core transcription factors and inhibiting Nodal signaling (see text).

All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. ** indicates highly significant (P<0.01) results based on ANOVA analyses following the Scheffe test.

Abbreviation: siNS, non-specific siRNA; siT, siRNA targeting Tcea3; siL, siRNA targeting to Lefty1.

Smad2 is an essential intracellular protein mediating the effects of TGF-β signaling, which is essential for embryonic mesoderm development and establishment of anterior-posterior polarity 17, 45. Furthermore, it was recently reported that Smad2 mediates Activin/Nodal signaling for mesendoderm differentiation in mESCs 19. In addition, microarray analysis of Tcea3 OE showed mesoderm marker genes of Tcea3 OE are activated compared to wild type mESCs under self-renewing condition (Figure S6). Our results corroborate these previous studies and provide evidence that Tcea3 particularly inhibits expression of mesoderm and endoderm lineage genes by suppressing Nodal-mediated TGF-β signaling. To further test this hypothesis, we treated differentiating Tcea3 KD with SB-431542, a specific chemical inhibitor of TGF-β receptor kinase, blocking phosphorylation of Smad2/3. Indeed, we found that treatment of Tcea3 KD cells with SB-431542 during in vitro differentiation significantly suppressed the increased expression of mesodermal and endodermal lineage genes whereas expression of ESC marker genes was unaffected (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

Pluripotent stem cells such as ESCs and iPSCs are exposed to constant cell fate choices between self-replication and differentiation. Thus, detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the transition between these cell fates is pivotal for their developmental studies and application to regenerative medicine. Surprisingly, our results reveal that the transcription elongation factor Tcea3 is highly expressed in mESCs and has an important function in regulating the differentiation potential. Despite its high expression in undifferentiated mESCs and rapid down-regulation during in vitro differentiation, expression levels of Tcea3 do not affect self-renewal, as demonstrated by their typical ESC morphology, stable passaging property without losing self-renewal capacity, ESC marker expression, LIF responsiveness, secondary EB formation, proliferation rate, and competition assays. Notably, there was no sign of differentiation of mESCs associated with altered expression levels of Tcea3 under undifferentiated condition, indicating that it does not directly induce differentiation. However, altered levels of Tcea3 in mESCs appear to critically influence the transition from self-renewal to multi-lineage differentiation commitment upon exposure to differentiating signals. When overexpressed (Tcea3 OE), mESCs were rendered more resistant to differentiation commitment, as evidenced by much delayed morphological changes and lower expression levels of lineage-specific genes, in particular mesoderm- and endodermlineage genes. In contrast, Tcea3 knockdown makes mESCs much more prone to differentiation upon exposure to differentiation-stimulating conditions, in particular to mesoderm- and endoderm-lineages, indicating a biased equilibrium between self-renewal and differentiation commitment. Remarkably, in sharp contrast to significantly altered expression of lineage-specific genes, overall expression patterns of core transcription factors (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog) were almost identical during in vitro differentiation of WT, Tcea3 OE, and Tcea3 KD cells, indicating that Tcea3 regulates multi-lineage differentiation commitment independently of self-renewal marker gene expression. The critical role of Tcea3 on differentiation potential was further confirmed by teratoma formation; while injection of Tcea3 KD generated larger size teratomas, injection of Tcea3 OE generated significantly smaller teratomas. In addition, Tcea3 KD cells formed teratomas faster than WT or Tcea3 OE cells.

Tcea1, Tcea2, and Tcea3 belong to the subfamily of transcription elongation factor TFIIS (SII) 33. Tcea1 is the original form, referred to as “general SII”, and its knockout mice die of severe anemia at midgestation 46. In contrast, biological functions of Tcea2 (also called SII-T1) and Tcea3 (also called SII-h or SII-K1) have been unknown. Our results show that Tcea3, but not Tcea1 or Tcea2, is highly expressed in mESCs. In addition, overexpression of Tcea3, but not that of Tcea1 or Tcea2, rescues the phenotype of Tcea3 KD mESCs, demonstrating its functional specificity.

Importantly, our results show that Tcea3 regulates balanced differentiation primarily through Lefty1 induction and subsequent inhibition of Nodal-Smad2 signaling, as evidenced by reversal of the Tcea3 effect by altered Lefty1 expression during ESC in vitro differentiation. In agreement with previous findings that Nodal and its effector Smad2 are critical for mesoderm and endoderm in vivo development 17, 18 and in vitro mESC differentiation 19, 20, we found that expression of mesoderm and endoderm-lineage genes were markedly up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively, in differentiating cells and teratomas from Tcea3 KD and Tcea3 OE. However, ectoderm marker genes were not always regulated in the same pattern, indicating that there are additional factors/pathways regulating the ectoderm differentiation commitment. Taken together, while Tcea3 levels do not control self-renewal of mESCs per se, their differentiation potential seems to be affected by Tcea3 before the differentiation process by altered Lefty1-Nodal-Smad2. In support of this, Tcea3 OE showed up-regulated mesoderm marker genes compared to wild type mESCs under self-renewing condition in our microarray analysis (Figure S6).

As illustrated in Fig. 6E, we propose that Tcea3 is a novel factor which biases the lineage allocation of differentiating mESCs, via the Lefty1-Nodal-Smad2 pathway. If Tcea3 expression levels are altered, this cell fate transition is biased and mESCs become either “desensitized” or “sensitized” to differentiation signals, indicating that Tcea3 regulates the transition between self-renewal and differentiation commitment as a molecular rheostat. Interestingly, core transcription factors, i.e., Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4, form a complex that activates Tcea3 as well as Lefty1 gene promoters 6, 47 supporting the idea that they serve as a molecular link between self-renewal and pluripotency (Fig. 6E). Our findings may be useful to understand distinct pluripotent states (e.g., “naïve” and “primed” pluripotent states) and reprogramming/differentiation processes 8, 48-51. In line with this, Tcea3 was found to be one of the genes that is expressed in fully reprogrammed iPSCs but not in partially reprogrammed cells 8 and is not expressed in mouse epiblast stem cells 52.

Conclusion

We found that Tcea3 controls cell fate choices of mESCs during the transition from self-renewal state to multi-lineage differentiation commitment by regulating the Lefty1-Nodal-Smad2 pathway and that its proper level is important for the balanced pluripotency of mESCs (Fig. 6E). Our data demonstrates that Tcea3 induces Lefty1 expression and limits differentiation potential by suppressing Nodal-pSmad2 signals. Upon exposure to differentiation-stimulating signals, expression of Tcea3, and subsequently Lefty1, is diminished and Nodal signals suppressed by Lefty1 are activated, leading to phosphorylation of Smad2 and induction (and/or “derepression”) of differentiation-related genes, in particular mesoderm- and endoderm-lineage genes.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. A customized SuperArray membrane was constructed with 111 selected genes based on genome-wide transcriptome analysis of mouse oocytes during in vitro maturation.

Figure S2. mESCs were differentiated into mesoendoderm lineage for 4 days and markers representing mesoderm and endoderm were analyzed for the expression by real-time RT-PCR. All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. * indicates significant (P<0.05) and ** highly significant (p<0.01) results based on ANOVA analyses following the Scheffe test.

Figure S3. 4 weeks old teratoma of WT and Tcea3 KD were analyzed for the expression of markers representing each lineage by real-time RT-PCR. The expression level of each gene was shown as relative value following normalization against that of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) gene.

Figure S4. Chromatin immunoprecipitation using antibodies against Tcea3 and rabbit IgG (as an immunoprecipitation control). DNA fragments were analyzed by PCR using primers specific for the proximal promoter region (Chip1) and downstream region of the Lefty1 gene (Chip2) (left). Relative quantification of Tcea3 immunoprecipitation enrichment at the Chip1 and Chip2 region was performed with WT, Tcea3 KD and Tcea3 OE cells. All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. * indicates significant (P<0.05) results based on Student's T-test analyses.

Figure S5. (A) Immunoblot analysis of p-Smad1/5 in Tcea3 OE and WT mESCs. Total cell extracts were prepared either from undifferentiated cells or 4 days after RA-induced differentiation. β-actin was used as loading control. (B) Expression levels of BMP4, ID1, ID2 and ID3 by microarray analysis of Tcea3 OE cells. (C) WT and Tcea3 OE cells were serum starved for 24 hrs and stimulated with Nodal (1 μg/ml). Cells were harvested at the indicated times after Nodal stimulation and pSmad2 (left panel) or pSmad1/5 (right panel) were analyzed by immunoblot.

Figure S6. Microarray analysis of Tcea3 OE shows mesoderm marker genes of Tcea3 OE are activated compared to wild type mESCs under self-renewing condition.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grants funded by the Korean government (MEST) (2010-0003254 and 2011-0014084). This work was also supported by Priority Research Centers Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2009-0093821). This work was also supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) grants MH087903, HL106627, and NS070577.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Kyung-Soon Park : Concept and design, Data analysis and interpretation, Writing

Young Cha: Concept and design, Collection and/or assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation

Chun-Hyung Kim: Collection and/or assembly of data

Hee-Jin Ahn: Collection and/or assembly of data

Dohoon Kim: Collection and/or assembly of data

Sanghyeok Ko: Collection and/or assembly of data

Kyeoung-Hwa Kim: Collection and/or assembly of data

Mi-Yoon Chang: Collection and/or assembly of data

Jong-Hyun Ko: Collection and/or assembly of data

Yoo-Sun Noh: Data analysis and interpretation

Yong-Mahn Han: Data analysis and interpretation

Jonghwan Kim: Collection and/or assembly of data

Jihwan Song: Collection and/or assembly of data

Jin Young Kim: Collection and/or assembly of data

Paul J. Tesar: Data analysis and interpretation

Robert Lanza: Data analysis and interpretation

Kyung-Ah Lee: Data analysis and interpretation

Kwang-Soo Kim: Concept and design, Data analysis and interpretation, Writing

References

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, et al. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boiani M, Scholer HR. Regulatory networks in embryo-derived pluripotent stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:872–884. doi: 10.1038/nrm1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Chu J, Shen X, et al. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niwa H, Ogawa K, Shimosato D, et al. A parallel circuit of LIF signalling pathways maintains pluripotency of mouse ES cells. Nature. 2009;460:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature08113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sridharan R, Tchieu J, Mason MJ, et al. Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell. 2009;136:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng HH, Surani MA. The transcriptional and signalling networks of pluripotency. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:490–496. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young RA. Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell. 2011;144:940–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalmar T, Lim C, Hayward P, et al. Regulated fluctuations in nanog expression mediate cell fate decisions in embryonic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunath T, Saba-El-Leil MK, Almousailleakh M, et al. FGF stimulation of the Erk1/2 signalling cascade triggers transition of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from self-renewal to lineage commitment. Development. 2007;134:2895–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.02880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichols J, Silva J, Roode M, et al. Suppression of Erk signalling promotes ground state pluripotency in the mouse embryo. Development. 2009;136:3215–3222. doi: 10.1242/dev.038893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doble BW, Patel S, Wood GA, et al. Functional redundancy of GSK-3alpha and GSK-3beta in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling shown by using an allelic series of embryonic stem cell lines. Dev Cell. 2007;12:957–971. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Zhu L, Yang A, et al. Calcineurin-NFAT signaling critically regulates early lineage specification in mouse embryonic stem cells and embryos. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nomura M, Li E. Smad2 role in mesoderm formation, left-right patterning and craniofacial development. Nature. 1998;393:786–790. doi: 10.1038/31693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moustakas A, Heldin CH. The regulation of TGFbeta signal transduction. Development. 2009;136:3699–3714. doi: 10.1242/dev.030338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fei T, Zhu S, Xia K, et al. Smad2 mediates Activin/Nodal signaling in mesendoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Res. 2010;20:1306–1318. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KL, Lim SK, Orlov YL, et al. Graded Nodal/Activin signaling titrates conversion of quantitative phospho-Smad2 levels into qualitative embryonic stem cell fate decisions. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jirmanova L, Afanassieff M, Gobert-Gosse S, et al. Differential contributions of ERK and PI3-kinase to the regulation of cyclin D1 expression and to the control of the G1/S transition in mouse embryonic stem cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:5515–5528. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I, et al. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanova N, Dobrin R, Lu R, et al. Dissecting self-renewal in stem cells with RNA interference. Nature. 2006;442:533–538. doi: 10.1038/nature04915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu RH, Peck RM, Li DS, et al. Basic FGF and suppression of BMP signaling sustain undifferentiated proliferation of human ES cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nmeth744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu SL, Amato H, Biringer R, et al. Targeted proteomics of low-level proteins in human plasma by LC/MSn: using human growth hormone as a model system. J Proteome Res. 2002;1:459–465. doi: 10.1021/pr025537l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidder BL, Yang J, Palmer S. Stat3 and c-Myc genome-wide promoter occupancy in embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tada M, Takahama Y, Abe K, et al. Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells by in vitro hybridization with ES cells. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1553–1558. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, et al. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature. 1997;385:810–813. doi: 10.1038/385810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon SJ, Kim KH, Chung HM, et al. Gene expression profiling of early follicular development in primordial, primary, and secondary follicles. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galan-Caridad JM, Harel S, Arenzana TL, et al. Zfx controls the self-renewal of embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2007;129:345–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmqvist L, Glover CH, Hsu L, et al. Correlation of murine embryonic stem cell gene expression profiles with functional measures of pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2005;23:663–680. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wind M, Reines D. Transcription elongation factor SII. Bioessays. 2000;22:327–336. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200004)22:4<327::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umehara T, Kida S, Hasegawa S, et al. Restricted expression of a member of the transcription elongation factor S-II family in testicular germ cells during and after meiosis. J Biochem. 1997;121:598–603. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taira Y, Kubo T, Natori S. Molecular cloning of cDNA and tissue-specific expression of the gene for SII-K1, a novel transcription elongation factor SII. Genes Cells. 1998;3:289–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labhart P, Morgan GT. Identification of novel genes encoding transcription elongation factor TFIIS (TCEA) in vertebrates: conservation of three distinct TFIIS isoforms in frog, mouse, and human. Genomics. 1998;52:278–288. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yap DY, Smith DK, Zhang XW, et al. Using biomarker signature patterns for an mRNA molecular diagnostic of mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation state. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qu CK, Feng GS. Shp-2 has a positive regulatory role in ES cell differentiation and proliferation. Oncogene. 1998;17:433–439. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koh KP, Yabuuchi A, Rao S, et al. Tet1 and Tet2 regulate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine production and cell lineage specification in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meno C, Gritsman K, Ohishi S, et al. Mouse Lefty2 and zebrafish antivin are feedback inhibitors of nodal signaling during vertebrate gastrulation. Mol Cell. 1999;4:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schier AF, Shen MM. Nodal signalling in vertebrate development. Nature. 2000;403:385–389. doi: 10.1038/35000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabibzadeh S, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Lefty at the crossroads of “stemness” and differentiative events. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1998–2006. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitman M, Mercola M. TGF-beta superfamily signaling and left-right asymmetry. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.64.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watabe T, Miyazono K. Roles of TGF-beta family signaling in stem cell renewal and differentiation. Cell Res. 2009;19:103–115. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waldrip WR, Bikoff EK, Hoodless PA, et al. Smad2 signaling in extraembryonic tissues determines anterior-posterior polarity of the early mouse embryo. Cell. 1998;92:797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito T, Arimitsu N, Takeuchi M, et al. Transcription elongation factor S-II is required for definitive hematopoiesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3194–3203. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3194-3203.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakatake Y, Fukui N, Iwamatsu Y, et al. Klf4 cooperates with Oct3/4 and Sox2 to activate the Lefty1 core promoter in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7772–7782. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00468-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanna JH, Saha K, Jaenisch R. Pluripotency and cellular reprogramming: facts, hypotheses, unresolved issues. Cell. 2010;143:508–525. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stadtfeld M, Hochedlinger K. Induced pluripotency: history, mechanisms, and applications. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2239–2263. doi: 10.1101/gad.1963910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han DW, Tapia N, Joo JY, et al. Epiblast stem cell subpopulations represent mouse embryos of distinct pregastrulation stages. Cell. 2010;143:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tesar PJ, Chenoweth JG, Brook FA, et al. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature05972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. A customized SuperArray membrane was constructed with 111 selected genes based on genome-wide transcriptome analysis of mouse oocytes during in vitro maturation.

Figure S2. mESCs were differentiated into mesoendoderm lineage for 4 days and markers representing mesoderm and endoderm were analyzed for the expression by real-time RT-PCR. All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. * indicates significant (P<0.05) and ** highly significant (p<0.01) results based on ANOVA analyses following the Scheffe test.

Figure S3. 4 weeks old teratoma of WT and Tcea3 KD were analyzed for the expression of markers representing each lineage by real-time RT-PCR. The expression level of each gene was shown as relative value following normalization against that of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) gene.

Figure S4. Chromatin immunoprecipitation using antibodies against Tcea3 and rabbit IgG (as an immunoprecipitation control). DNA fragments were analyzed by PCR using primers specific for the proximal promoter region (Chip1) and downstream region of the Lefty1 gene (Chip2) (left). Relative quantification of Tcea3 immunoprecipitation enrichment at the Chip1 and Chip2 region was performed with WT, Tcea3 KD and Tcea3 OE cells. All values are means ± s.d. from at least triplicate experiments. * indicates significant (P<0.05) results based on Student's T-test analyses.

Figure S5. (A) Immunoblot analysis of p-Smad1/5 in Tcea3 OE and WT mESCs. Total cell extracts were prepared either from undifferentiated cells or 4 days after RA-induced differentiation. β-actin was used as loading control. (B) Expression levels of BMP4, ID1, ID2 and ID3 by microarray analysis of Tcea3 OE cells. (C) WT and Tcea3 OE cells were serum starved for 24 hrs and stimulated with Nodal (1 μg/ml). Cells were harvested at the indicated times after Nodal stimulation and pSmad2 (left panel) or pSmad1/5 (right panel) were analyzed by immunoblot.

Figure S6. Microarray analysis of Tcea3 OE shows mesoderm marker genes of Tcea3 OE are activated compared to wild type mESCs under self-renewing condition.