Abstract

The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R) mediates Ca2+ signaling in epithelia and regulates cellular functions such as secretion, apoptosis and cell proliferation. Loss of one or more InsP3R isoform has been implicated in disease processes such as cholestasis. Here we examined whether gain of expression of InsP3R isoforms also may be associated with development of disease. Expression of all three InsP3R isoforms was evaluated in tissue from colorectal carcinomas surgically resected from 116 patients. Type I and II InsP3Rs were seen in both normal colorectal mucosa and colorectal cancer, while type III InsP3R was observed only in colorectal cancer. Type III InsP3R expression in the advancing margins of tumors correlated with depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, liver metastasis, and TNM stage. Heavier expression of type III InsP3R also was associated with decreased 5-year survival. shRNA knockdown of type III InsP3R in CACO-2 colon cancer cells enhanced apoptosis, while over-expression of the receptor decreased apoptosis. Thus, type III InsP3R becomes expressed in colon cancer, and its expression level is directly related to aggressiveness of the tumor, which may reflect inhibition of apoptosis by the receptor. These findings suggest a previously unrecognized role for Ca2+ signaling via this InsP3R isoform in colon cancer.

Keywords: Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; Calcium signaling; Colorectal cancer; Prognosis; Apoptosis

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death among both men and women in the US [1]. Moreover, nearly one million new cases are reported annually worldwide, and this malignancy accounts for almost half a million deaths every year. The efforts to identify new etiologic and prognostic factors have enabled us to predict the clinical outcome of colorectal cancer patients. A major focus has been on genetic and epigenetic alterations that result in colon cancer, including microsatellite and chromosome instability [2]. Mouse models have implicated a number of pathways in these processes, including Wnt/beta-catenin and arachidonic acid metabolism [3]. These pathways can directly activate Ca2+ signaling, which in turn has known effects on cell growth, but the role of Ca2+ signaling in colorectal cancer has received little attention.

Cytosolic Ca2+ is an important regulator of both cell proliferation [4] and apoptosis [5] in epithelia. In the progression of colon cancer, the balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis tips in favor of cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis [6]. This may suggest that enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ signaling could contribute to the transition from normal colonic epithelial cells, to adenomas, and finally carcinoma. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R) is the principal intracellular Ca2+ release channel in epithelia. It is an InsP3-gated Ca2+ release channel located in the endoplasmic reticulum [7]. The three isoforms of the InsP3R are denoted type I, II, and III, and each has distinct functional properties and tissue distributions. Loss of expression of the type III InsP3R occurs in a range of cholestatic disorders [8], and evidence suggests that this loss of expression may be directly responsible for impaired ductular secretion [9]. In contrast, Ca2+ release from the InsP3R is increased in disorders such as Huntington’s Disease or bipolar affective disorder, although this increased receptor channel activity is due to changes in proteins that interact with the InsP3R [10,11], rather than an increase in InsP3R expression. To our knowledge, pathological conditions that are associated with or result in part from increased expression of the InsP3R have not been reported. Because InsP3Rs provide a mechanistic link between stimulation with growth factors [12,13] and Ca2+ signals that mediate cell proliferation and tumor growth [4], the purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between InsP3R expression and colorectal carcinoma.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

Specimens were obtained from 116 patients who underwent surgery for primary colorectal carcinoma between 1995 and 2000 in the Department of Surgery I, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, Japan. Patients included 65 men and 51 women, with age ranging from 32 to 95 years (median, 65.7 years). Survival data were available for a median of 108 months (range, 2.9–115.9 months). The tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) classification system was used to define clinical stage and depth of tumor invasion. Histologic typing was determined following the World Health Organization classification system. These studies were approved by the clinical ethics committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health.

2.2. Antibodies

Type I InsP3R antibody (affinity-purified specific rabbit polyclonal antiserum) directed against the 19 C-terminal residues of the type I InsP3R was commercially obtained from Upstate Biotech (Lake Placid, NY) [14]. Type II InsP3 receptor antibody (affinity-purified specific rabbit polyclonal antiserum) directed against the 18 C-terminal residues of the rat type II InsP3 receptor was custom produced by Iwaki (Tokyo, Japan) [15]. A monoclonal antibody against the N-terminal region of the human type III InsP3 receptor was obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY) [16].

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Samples of tumor margin and normal colonic mucosa at the proximal or distal margin were fixed with formalin. Paraffin embedded materials were cut at a thickness of 2 µm. Sections were pretreated twice for 5 min with 0.01 mol/l citrate buffer, pH 6.0, at 100 °C in a microwave oven. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% H2O2 in absolute methanol for 5min. Each section was pre-incubated in sheep or rabbit serum for 10 min. Then, sections were incubated with each antibody, diluted 1:500 for type I and type II, and 1:100 for type III InsP3 receptor for 60 min. Subsequently, sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated with Envision-labeled polymer (DAKO, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 min. Finally, diaminobenzidine was used as a chromogen, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. PBS was substituted for the primary antibody in negative controls. Paraffin embedded liver sections were used as positive controls for each InsP3R isoform.

2.4. Histopathology

Each slide was assessed independently by two investigators (KS and KH) who were unaware of clinical outcomes. Inter-observer agreement with regard to the scoring of immunostaining exceeded 95%. InsP3R staining at the invasive margin and in central tumor areas was separately scored by counting the frequency of labeled cells in 5 high-power fields containing roughly 100 cells each. This count was performed using the following criteria: 0, staining in <25% of tumor cells; +, staining in <50% of tumor cells (0 and + indicated weak InsP3 receptor expression); ++, staining in 50–75% of tumor, and +++, staining in 75–100% of tumor cells (++ and +++ indicated strong InsP3 receptor expression). The intensity of staining in all tumors was compared with staining in histologically normal colonic mucosa from the same specimens.

2.5. Cell culture and reagents

CACO-2 cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in Eagle’s Minimal Essential Media (EMEM; ATCC) supplemented with 20% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; ATCC) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S; Gibco, Carlsbad, California). Staurosporine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was diluted in Dimethyl Sulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Scrambled (ca# 4390643) and InsP3R Type III (IP3R3) (ca# 4390771) Silencer® Select short hairpin RNAi molecules were purchased from Applied Biosystems Inc. (Foster City, CA). Transient transfection was carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) in OPTI-MEM Serum Reduced Media (Gibco, Carlsbad, California). The BrdU Colorimetric Cell Proliferation ELISA kit was obtained from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Protein lysate was harvested in Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (M-PER, Pierce, Rockford, IL) with 2% Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma St. Louis, MO). Cells were fixed using 100% Methanol (J.T. Baker, Austin, TX) and nuclei were stained with Hoescht DNA Stain (Lonza, Allendale, NJ).

2.6. Transient transfections

CACO-2 cells were grown to a confluency of approximately 70% before transfection. Briefly, cells were washed with 1X PBS and media was replaced with OPTI-MEM before transfection. Silencer® Select shRNA (Applied Biosystems) was transfected at a final concentration of 5 nM in OPTI-MEM media via Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent using the manufacturer’s protocol. OPTI-MEM media was replaced 24 h after transfection with complete media (EMEM + 20% FBS and 1% P/S). For overexpression experiments, 5 µg of cDNA corresponding to type III InsP3R (courtesy of David Yule, University of Rochester) was transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent, using manufacturer protocol. Exchange of media and protein harvesting were as previously stated. In both RNAi and overexpression experiments, protein lysate was harvested 72 h after transfection.

2.7. Western blot detection

For InsP3R isoform western blots, 50 µg of protein from control or CACO-2 cells was loaded onto a 4–20% SDS PAGE gel. CACO-2 lysate was collected in M-PER reagent, supplemented with 2% protease inhibitor. Positive controls for type I, II, and III InsP3R were mouse total cortex, hepatocyte lysate, and CHO cell lysate, respectively. Protein was then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was then blocked with Tris-Buffered Saline (BioRad, Hercules, CA) plus 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST). Polyclonal antibodies were used for type I InsP3R (Upstate ca# 07-514) and type II InsP3R (Wojcikiewicz Lab) at concentrations of 1:2000 and 1:100, respectively. A monoclonal antibody against type III InsP3R (BD Biosciences ca# 610312) was used for all type III InsP3R western blots at a concentration of 1:1000. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C in TBST + 5% milk. The incubated membrane was then washed three times with TBST and subsequently probed with a sheep anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to a peroxidase enzyme (GE Healthcare, Giles, United Kingdom) at a dilution of 1:5000 for 1 h at room temperature. After three more washes, bands were visualized using the ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare, Giles, United Kingdom) and BioMAX MR Film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). RNAi and type III InsP3R overexpression western blots were carried out with the addition of α-tubulin (monoclonal antibody, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 1:5000 dilution) as a loading control. In the case of type III InsP3R overepression, western blots used 25 and 50 µg protein.

2.8. Apoptosis

CACO-2 cells were plated on 22 mm × 22 mm glass coverslips and transfected with shRNAs or type III InsP3R cDNA. 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with either Staurosporine diluted in DMSO or DMSO alone. Mock transfected (Mock), scrambled shRNA (SCR), and InsP3R3 shRNA or Mock and type III InsP3R cDNA transfected cells (IP3R3 Over Expressed) were analyzed in the presence or absence of Staurosporine (1 µM) for a total of 6 coverslips per experiment. Apoptosis was induced for 24 h and cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with methanol at −20 °C for 15 min. Cells were then washed again and probed with Hoescht DNA stain diluted 1:1 × 105 in PBS plus 0.1% BSA. Coverslips were washed after fixation and mounted on slides using 10 µl Hydro-mount(National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA). Cells were then analyzed for apoptosis using a Nikon Eclipse 800 Fluorescent Microscope. Briefly, nuclei were visualized to determine chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation, indicative of cells undergoing apoptosis, as described previously [5]. Five random pictures were taken per coverslip and > 300 cells were analyzed per condition per experiment (n = 3).

2.9. BrdU proliferation assay

CACO-2 cells were plated on clear flat bottom 96-well plates at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/ml (5000 cells/well). Cells were transfected 48 h after plating with shRNA molecules (5 nM) or InsP3R3 cDNA (100 ng/well), then 10 µl of BrdU labeling solution was added to each well 48 h after transfection. Treated cells were incubated for 24 h with BrdU labeling reagent and were subsequently dried at 60 °C for 1 h. Treated cells were then fixed and labeled according to manufacturer protocol. Upon completion of the protocol, cells were analyzed on a plate reader at an absorbance of 370 nm and measurements were recorded and analyzed using Excel.

2.10. Statistics

Data are presented as arithmetic means ± S.E.M. unless otherwise indicated. For statistical analysis, means between groups were compared by the t test. Chi-square tests, and Mann–Whitney U-tests were used for comparison of clinicopathologic features of tumors with strong and weak InsP3R expression. Survival rates were estimated by using the method of Kaplan and Meier and were compared using the log-rank test. Various parameters were analyzed for prognostic significance by univariate Cox proportional hazards methods using the SAS software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. InsP3R expression in normal colorectal mucosa and in carcinoma

Clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients in this study are summarized in Table 1. For each patient, InsP3R labeling was examined in tissue from the tumor and from normal mucosa at the resection margin. Both type I and II InsP3Rs were detected in normal mucosa. Type I InsP3R was uniformly distributed throughout the cytosol, although the nucleus appeared to be excluded (Fig. 1A). In contrast, type II InsP3R expression was observed only in the apical region of colonocytes (Fig. 1B). No type III InsP3R was detected in normal mucosa (Fig. 1C), and no labeling was seen in negative control tissues stained with secondary antibody alone (data not shown). Therefore, this pattern of InsP3R isoform expression and distribution is similar to what has been observed in hepatocytes [17] but differs from what has been reported in other digestive epithelia, including pancreatic acinar cells [18] and cholangiocytes [19].

Table 1.

Patients and clinicopathologic data.

| Variable | No. of patients (%) (n = 116) |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs) (mean ± S.D.) | 65.7 ± 1.1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 65 (56) |

| Female | 51 (44) |

| Tumor location | |

| Colon | 58 (50) |

| Rectum | 58 (50) |

| Histologic type | |

| Well-differentiated | 29 (25) |

| Moderately differentiated | 80 (69) |

| Poorly differentiated | 4(3.4) |

| Mucinous | 3(2.6) |

| Depth of invasiona | |

| T1 | 1(0.9) |

| T2 | 22 (19) |

| T3 | 64(55.1) |

| T4 | 29 (25) |

| Clinical stagea | |

| I | 18(15.5) |

| II | 32(27.6) |

| III | 38(32.8) |

| IV | 28(24.1) |

The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification was used with respect to clinical stage and depth of tumor invasion.

Fig. 1.

Human colorectal mucosa expresses type I and type II but not type III InsP3 receptors. Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens in colorectal mucosa. (A) Type I InsP3 receptor expression in normal mucosa. Strong type I InsP3 receptor expression is seen in a granular pattern, diffusely throughout the cytoplasm (brown). (B) Type II InsP3 receptor expression in normal mucosa. Strong type II InsP3 receptor expression is seen in the region near the apical membrane. (C) Normal mucosa does not express the type III InsP3 receptor. Original magnification A, B, and C: 200×; insets of A and B: 1000×. Nuclei were counterstained with haematoxylin (blue). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Colorectal carcinomas expressed each of the three isoforms of the InsP3R, but to variable degrees (Fig. 2). In tumors expressing the type I InsP3R, it was seen throughout the cytosol in a granular distribution (Fig. 2A), similar to what was observed in normal colonocytes (Fig. 1A). However, type I InsP3R expression was absent in some tumors (Fig. 2B). Similarly, in tumors expressing the type II InsP3R, the receptor was mostly concentrated in the apical region (Fig. 2C), as it was in normal colonocytes (Fig. 1B). However, in some tumors type II InsP3R expression was absent (Fig. 2D). Although no type III InsP3R expression was observed in normal colorectal mucosa, this isoform was seen in some colorectal cancers (Fig. 2E), but not in all cases (Fig. 2F). Moreover, expression of the type III InsP3R tended to be greater in cancer cells at the invasive margin of the tumor (Fig. 3A and B). Intense labeling of type III InsP3R was particularly noticeable in actively invading cancer cells that showed budding from cellular nests or sheets, as well as in cells that were infiltrating singly or as small clusters of cells (Fig. 3B). These findings demonstrate a variable change in the expression of InsP3R isoforms in colonic epithelial cells in colon cancer, and in particular suggest an increase in type III isoform expression in tumor invasion.

Fig. 2.

Colorectal cancer expresses various levels of all InsP3 receptor isoforms. Immunostaining of colorectal cancers variably reveals strong (A, C, and E) or weak (B, D, and F) labeling of each isoform of the InsP3 receptor. (A) Strong type I InsP3 receptor expression in a granular pattern in the cytoplasm. (B) Weak expression of the type I InsP3 receptor in colorectal cancer. (C) Strong type II InsP3 receptor expression in the apical region of a colorectal cancer. (D) A representative case of no type II InsP3 receptor expression in colorectal cancer. (E) Strong luminal expression of type III InsP3 receptor. (F) A representative case of no type III InsP3 receptor expression. Original magnification (A–F): 400×. Nuclei were counterstained with haematoxylin (blue). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Fig. 3.

Colorectal cancer in the invasive margin showed strong expression of type III InsP3 receptor. (A) Tumor center and invasive margin of colorectal cancer are shown. (B) Higher magnification of the rectangular area in (A). Although type III InsP3 receptor expression was weak in the center of the tumor (A, asterisk), stronger labeling was evident in the invasive margin of the tumor (B, arrow heads). Original magnification A: 200×, B: 400×. Nuclei were counterstained with haematoxylin (blue). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

3.2. Type III InsP3R expression is associated with worse clinical course

The clinical significance of the expression and distribution of the three InsP3R isoforms was examined in several ways. Table 2 summarizes InsP3R expression in the center and in the invasive margin of tumors. Strong type I InsP3 receptor expression was seen in the central area of the tumor in 23 patients (19.8%) and in the invasive margin in 75 patients (64.7%). In contrast, type II InsP3 receptor expression was strong with nearly equal frequency in the central regions of tumors and in invasive margins (84 patients: 72.4%, vs. 83 patients: 71.6%, respectively). Marked type III InsP3 receptor expression was found in the central region of tumors in 15 patients (12.9%), and was seen in the invasive margins of tumors in 34 patients (29.3%). These findings suggest that expression of both the type I and type III isoform of the InsP3R is increased more often in the invasive edge than in the central region of colon cancers.

Table 2.

Expression of the InsP3 receptor expression in tumor center and invasive front of the tumor.

| Type I | Type II | Type III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | Front | Center | Front | Center | Front | |

| Strong | 23(19.8) | 75(64.7) | 84(72.4) | 83(71.6) | 15(12.9) | 34(29.3) |

| Weak | 93(81.2) | 41(35.3) | 32(27.6) | 33(28.4) | 101(87.1) | 82(70.7) |

Type I: type I InsP3 receptor, type II: type II InsP3 receptor, type III: type III InsP3 receptor, Center: tumor center, front: invasive front of the tumor, No. of patients (%).

Next, the relationship between InsP3R expression and various clinicopathologic characteristics was examined. Neither type I nor type II InsP3R expression, in either the center or the invasive margin of the tumor, was correlated with any clinical or pathological factors (not shown). Type III InsP3R expression in the center of the tumor also did not correlate with any clinicopathological factors. However, strong type III InsP3R expression in the invasive margin was significantly correlated with several measures of tumor aggressiveness (Table 3). Patients with strong type III InsP3R expression exhibited significantly more advanced tumor invasion (p = 0.029) and more frequent lymph node metastasis (p = 0.004). Furthermore, patients with strong type III InsP3R expression had a higher frequency of hepatic metastasis compared to patients with weak type III InsP3R expression (23.5% vs. 8.5%, respectively, p = 0.02). Finally, the clinical stage of the disease tended to be worse in patients with strong type III InsP3R expression in the invasive front of the tumor (p = 0.015). Thus, type III InsP3R expression in the invasive margin of the tumor strongly indicates more aggressiveness of the tumor.

Table 3.

Clinicopathologic features and type III InsP3 receptor expression in invasive front of the tumor.

| Variable | No. of patients (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak type III InsP3R expression (n = 82) | Strong type III InsP3R expression (n = 34) | ||

| Age (yrs) (mean±S.D.) | 66±1.2 | 64.9±2.2 | 0.649 |

| Gender | 0.104 | ||

| Male | 42(51.2) | 23(67.6) | |

| Female | 40(48.8) | 11(32.4) | |

| Tumor location | 0.999 | ||

| Colon | 41 (50) | 17 (50) | |

| Rectum | 41 (50) | 17 (50) | |

| Histologic type | 0.999 | ||

| Well-differentiated | 20(24.4) | 8(23.5) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 57(69.5) | 24(70.6) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 3(3.7) | 1(2.9) | |

| Mucinous | 2(2.4) | 1(2.9) | |

| Depth of invasiona | 0.029 | ||

| T1 | 1(1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| T2 | 21(25.6) | 2(5.9) | |

| T3 | 42(51.2) | 21(61.8) | |

| T4 | 18 (22) | 11(32.3) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.004 | ||

| N0 | 46(56.2) | 8(23.5) | |

| N1 | 22(26.8) | 17 (50) | |

| N2 | 14 (17) | 9(26.5) | |

| Liver metastasis | 0.02 | ||

| Absent | 75(91.5) | 26(76.5) | |

| Present | 7(8.5) | 8(23.5) | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.185 | ||

| Absent | 65(79.3) | 24(70.6) | |

| Present | 17(20.7) | 10(29.4) | |

| Clinical stagea | 0.015 | ||

| I | 17(20.7) | 1(2.9) | |

| IIa | 23 (28) | 7(20.6) | |

| IIb | 2(2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| IIIa | 3(3.7) | 3(8.8) | |

| IIIb | 13(15.9) | 10(29.4) | |

| IIIc | 7(8.5) | 2(5.9) | |

| IV | 17(20.7) | 11(32.3) | |

NS: no significant difference; (−) negative; (+) positive.

The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification was used with respect to clinical stage and depth of tumor invasion.

Survival rates were examined for the 116 patients by using the method of Kaplan and Meier and were compared using a log-rank test (Fig. 4). There was no difference in 5-year survival rates between patients with strong or weak expression of each InsP3R isoform in the center of the tumors (78.5% vs. 76.1% for type I, 76.7% vs. 76.5% for type II, 76.2% vs. 80% for type III InsP3 receptor, respectively). Thus, expression of type I, type II, or type III InsP3R in the center of the tumor does not correlate with prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. However, the overall 5-year survival rate in patients with strong expression of type III InsP3R in the invasive margin of their tumor was significantly lower than that of patients with weak expression in their tumor (5-year survival rates, 61.5% vs. 82.7%, p = 0.033; Fig. 4). No such difference in survival rate was observed in relation to expression of type I or type II InsP3 receptors.

Fig. 4.

Enhanced expression of type III InsP3 receptor is associated with poorer survival rate in colorectal cancer patients. Kaplan-Meier curve is shown for InsP3 receptor expression levels (weak vs. strong) in the invasive margin of colorectal carcinoma and the corresponding survival rate of patients over 5 years. (A) Weak (n = 41) and strong (n = 75) type I InsP3 receptor expression, p = 0.66. (B) Weak (n = 33) and strong type II InsP3 receptor expression (n = 83), p = 0.26. (C) Weak (n = 82) and strong type III InsP3 receptor expression (n = 34). The 5-year survival rate of patients with strong type III InsP3 receptor expression (61.5%) was significantly lower than that of patients with weak expression (82.7%). p = 0.033.

3.3. Effect of type III InsP3R on cell survival

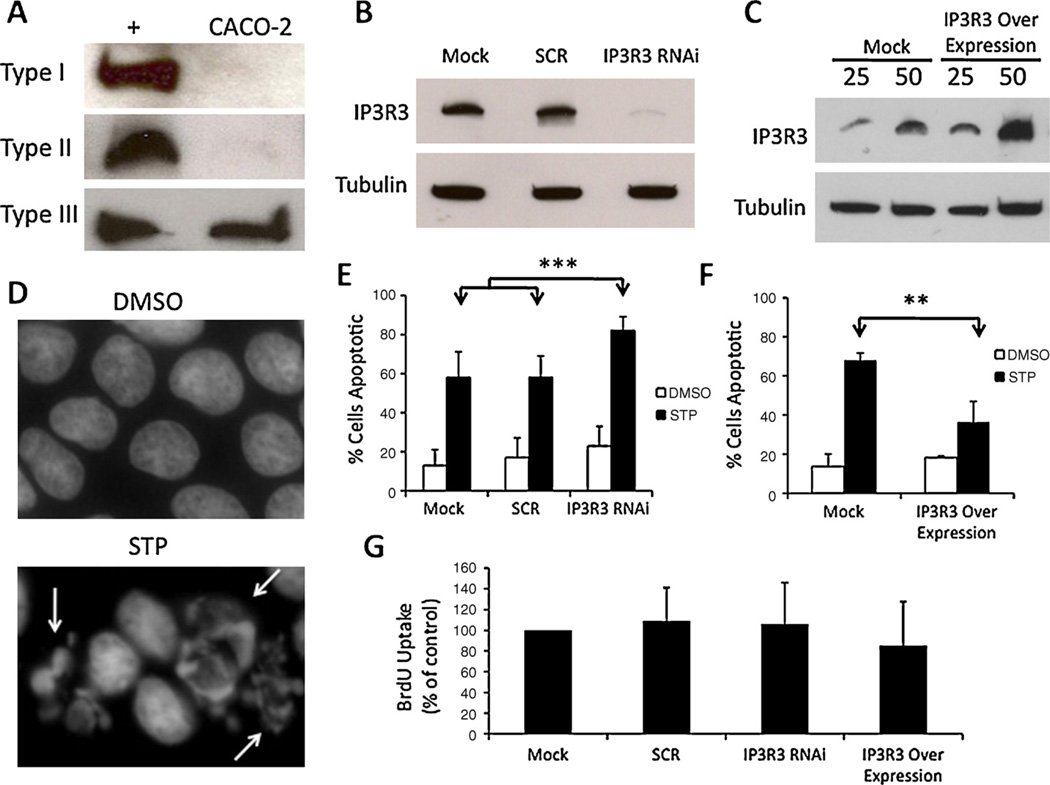

In order to determine the effect of type III InsP3R expression on survival in colorectal cancer cells, CACO-2 cells were manipulated via RNAi knockdown or overexpression of type III InsP3R. In CACO-2 cells, the type III InsP3R isoform is predominant and expression of the types I and II isoforms is nil (Fig. 5A). Expression of endogenous type III was reduced by ~90% using RNAi (Fig. 5B), while expression was increased nearly two-fold by transfection of the receptor (Fig. 5C). Apoptosis was analyzed in CACO-2 cells using staurosporine (STP) as an apoptosis-inducing agent by assessing nuclear fragmentation, which occurs during programmed cell death, but not with DMSO alone (Fig.5D, white arrows).Mock transfected cells, cells transfected with scramble (SCR) or type III InsP3R shRNA, and cells transfected with type III InsP3R cDNA were incubated with either 1 µM STP or DMSO vehicle alone for 24 h. With respect to RNAi treatments involving DMSO alone there was no significant difference among groups in the frequency of apoptosis. However, in the presence of STP, type III InsP3R knockdown significantly (p < 0.0001) increased the frequency of apoptosis relative to other groups; 58.1% of mock transfected cells and 58.1% of cells transfected with scrambled shRNA underwent apoptosis, as compared to 82.7% of CACO-2 cells in which type III InsP3R was knocked down (Fig. 5E). When type III InsP3R expression was increased, STP-induced apoptosis was significantly reduced (p < 0.01); only 36.3% of over-expressing cells scored apoptotic relative to 67.9% under mock transfected conditions (Fig. 5F). Differences in apoptosis with DMSO treatment alone were not significant. BrdU experiments were carried out to assess whether type III InsP3R expression also affects cell proliferation. No significant difference was observed between control cells and those with either reduced or enhanced expression of InsP3R3 (Fig. 5G). Taken together, these results suggest that the type III IP3R expression that occurs in colon cancer cells confers a survival advantage, and that this occurs by inhibiting apoptosis rather than by stimulating cell proliferation.

Fig. 5.

Type III InsP3 receptor expression is protective against apoptosis in a human colorectal cancer cell line. (A) Western blot of type I, II, III InsP3R in positive control (+) and CACO-2 cells shows nearly all InsP3R is type III in CACO-2 cells. Controls for type I, II, and III were mouse cortex, Hepatocyte, and CHO lysates, respectively. (B) An isoform-specific shRNA resulted in ~90% reduction in type III InsP3R in CACO-2 cells and was used in subsequent studies. The same concentration (5 nM) of a non-specific scrambled (SCR) shRNA was used as a control in all RNAi experiments. Alpha-tubulin was used as a loading control, and 50 µg of protein was used for Western Blot. Mock corresponds to a mock transfection control that contains transfection reagent but no RNAi material. (C) Type III InsP3R3 was over-expressed in CACO-2 cells via transient transfection of type III InsP3R cDNA. “25” and “50” correspond to 25 and 50 µg protein loaded, respectively. Tubulin used as loading control. Expression was increased by ~100%. (D) Hoescht stain of CACO-2 nuclei under DMSO (vehicle) and STP (1 µM) treatments (24 h). Arrows indicate fragmented nuclei, which were scored as apoptotic. (E) Percentage of cells scored as apoptotic under RNAi conditions. For mock transfected cells, 13 ± 8% of cells underwent apoptosis in the presence of DMSO and 58 ± 13% were apoptotic in the presence of STP. For Scrambled transfected cells, 17 ± 10% of cells were apoptotic in the presence of DMSO as compared to 58 ± 11% in the presence of STP. For shIP3R3 transfected cells, 23 ± 10% of cells were apoptotic in the presence of DMSO as compared to 82 ± 7% in the presence of STP. Over 300 cells were analyzed under each condition and in each experiment. Values are mean ± S.D. of triplicate measurements (***p < 0.0001). (F) For mock transfected cells, 13 ± 6% of cells underwent apoptosis in the presence of DMSO and 67 ± 3% were apoptotic in the presence of STP. In cells transfected with type III InsP3R over expressed, 18 ± 1% of cells were apoptotic in the presence of DMSO and 36 ± 10% were apoptotic in the presence of STP (**p < 0.01). (G) BrdU uptake was used to measure proliferation of cells with either reduced or enhanced expression of InsP3R3. No statistically significant differences relative to control (Mock transfection) were observed. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

4. Discussion

A wide range of cell signaling pathways converge to regulate InsP3-mediated Ca2+ signaling. This is particularly important for cancer biology, because both apoptosis [5] and tumor growth [4] are regulated in part by Ca2+ signals. The expression and subcellular distribution of the three InsP3R isoforms is important for establishing the range of effects of InsP3-mediated Ca2+ signals in epithelia [20,9], so we investigated the expression of InsP3R isoforms in normal and neoplastic colonic epithelia, and the relationship between InsP3R expression and clinical course. Type I and II InsP3 receptors were expressed in both normal mucosa and colorectal cancer cells. In contrast, the type III InsP3 receptor was found only in cancer cells, and especially in actively invading cancer cells. Moreover, increased expression of the type III InsP3 receptor in the invasive margin of tumors related to poor prognosis. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating enhanced expression of InsP3Rs in a disease state, and in particular identifies expression of the type III InsP3 receptor in the invasive margin of the tumor as a prognostic predictor in patients with colon cancer. Expression of the type III InsP3R also conferred a survival advantage by inhibiting apoptosis in colon cancer-derived cells, suggesting a pathophysiological basis for this novel biomarker.

In this study we found that normal colonic epithelia express the type I InsP3R throughout the cell, while they express the type II InsP3R in the peri-apical region. The type I InsP3 receptor is the dominant subtype expressed in the central nervous system, but is also observed in kidney, cholangiocytes, hepatocytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells [21]. The type II InsP3 receptor is found in several organs including heart, pancreas, lung, liver, and kidney [22]. The type III InsP3 receptor, which is absent from normal colonocytes, is also absent in normal hepatocytes [17], but is found in cholangiocytes, pancreas, lung, and kidney [19,23]. In virtually all polarized epithelia, at least one InsP3R isoform appears to be concentrated in the peri-apical region. Hepatocytes, like colonocytes, express the type II InsP3R in this region [17], while cholangiocytes instead express the type III InsP3R predominantly in this region [19], and pancreatic acinar cells express both the type II and III InsP3R in the apical region [24]. It is thought that the local accumulation of InsP3Rs in the apical region is important for regulating epithelial secretion, because it permits local increases in Ca2+ to reach the low micromolar range, which in turn facilitates docking and fusion of exocytic vesicles with the apical membrane [25]. It is possible that the type II InsP3R serves a similar role in colonic epithelia, but this has not been investigated. Both type I and II InsP3 receptor expression also appeared to be enhanced among colonocytes nearer to the lumen (Fig. 1), but it is unclear whether this relates to specific differences in the ability of cells at the surface and the upper part of the crypt to absorb water and electrolytes, relative to apical transport activity among cells that are deeper in the crypt.

Variability in expression of each InsP3R isoform was seen among patients with colon cancer (Fig. 2), and this may in turn have affected the susceptibility of colon cancer cells to undergo apoptosis. Apoptosis generally occurs through one of two pathways. The extrinsic pathway is initiated by activation of death receptors, whereas the intrinsic pathway acts on mitochondria to induce formation of the permeability transition pore and release of cytochrome c. Both apoptotic pathways are dependent on InsP3 receptor expression [26]. Each of the three InsP3R isoforms may mediate induction of apoptosis, although with differing propensities [5]. The ability of the InsP3 receptor to modulate apoptosis is thought to be related to its actions as a Ca2+ release channel; Ca2+ released from the ER via the InsP3R stimulates mitochondria to release cytochrome c, which then binds directly to the InsP3 receptor and enhances further Ca2+ release from ER, which further promotes apoptosis [27]. Conversely, a variety of proteins that inhibit apoptosis do so by inhibiting InsP3R-mediated increases in mitochondrial Ca2+. For example, Bcl-xL inhibits InsP3 receptor expression [28], Bcl-2 decreases the size of ER Ca2+ stores [29], and Mcl-1 inhibits mitochondrial Ca2+ signals [30]. Although each of the three InsP3R isoforms may participate in inducing apoptosis, the type III isoform has been thought to be particularly important. For example, the role of the type III isoform has been reported in cell types including a B cell line (DT-40), kidney cell line (COS-7, HEK293), pheochromocytoma cell line (PC-12), ovarian cell lines (ROSE-179 and CHO), and a biliary adenocarcinoma cell line (Mz-Cha-1) [26,23,31,32,19]. Evidence suggests this characteristic of the type III InsP3R may be because it co-localizes more closely with mitochondria and can transmit Ca2+ signals to them more effectively [5]. However, we observed here that expression of the type III InsP3 receptor inhibited rather than enhanced apoptosis in a colorectal cancer cell line. It is not clear whether this reflects a cell type-specific effect, whether the type III InsP3 receptor localizes differently within cancer cells, or whether this reflects some different process entirely. The InsP3R can associate with other proteins, including scaffolding proteins [33], and can localize to signaling microdomains related to lipid rafts as well [34], so type III InsP3R in colon cancer cells may localize to tumor-promoting or apoptosis-inhibiting signaling domains that remain to be identified.

Ca2+ signaling affects a broad range of cell functions, and a wide range of human diseases have been attributed to alterations in Ca2+ signaling. Several human diseases have been linked to altered InsP3R expression or function in particular. Expression of the type III InsP3R in cholangiocytes is decreased in a number of cholestatic conditions, including primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, biliary atrersia, and bile duct obstruction [8]. Knockdown of this InsP3R isoform in microperfused bile ducts results in impaired ductular bicarbonate secretion [9], suggesting that the loss of InsP3Rs in cholestatic diseases may be an important factor in the development of cholestasis. Several clinical conditions have been identified in which InsP3R function is enhanced. For example, byproducts of alcohol metabolism enhance Ca2+ release from type II and III InsP3Rs in pancreatic acinar cells, and this has been linked to intracellular zymogen activation and development of pancreatitis [35]. Also, mutations in presenilin cause this protein to interact with neuronal InsP3Rs, leading to enhanced Ca2+ release that has been linked to development of a familial form of Alzheimer’s Dementia [36], and a mutant form of ataxin-2 has similarly been linked to enhanced activation of InsP3Rs in cerebellar purkinje neurons and development of spinocerebellar ataxia [37]. Expression of the type III InsP3R is increased in gastric cancer cells lines established from malignant ascites, relative to expression levels in normal gastric epithelium [38]. The significance of this finding is unclear because type III InsP3R expression generally is increased in cell lines relative to what is observed in primary cells [23]. In the current work, the novel observation is made that colon cancer cells express type III InsP3R de novo, and that increased expression of this isoform is associated with increased aggressiveness of the tumor and decreased long-term survival. The relationship may be a causal one, because knockdown of this receptor isoform enhances susceptibility to apoptosis. Additional work will be needed to understand the stimulus for expression of this InsP3R isoform in colon cancer, and whether inhibition of either expression or function of the type III InsP3R would be a useful target for treatment.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Y. Ueda for her skillful technical assistance and Dr. David Yule for providing cDNA for type III InsP3R. This work was supported in part by Grant-in-aid for scientific research (C) number 20591583, 20591598, and 18591490 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan to KS, KH, and KY, and NIH grants DK57751, DK45710, DK61747, and DK34989 to MHN, and YCCI (ULRR024139) and DK082600 to YI.

Abbreviations

- InsP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- InsP3R

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- Ca2+i

cytosolic Ca2+

Footnotes

Grant support: This work was supported by Grant-in-aid for scientific research (C) number 20591583, 20591598, and 18591490 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan to KS, KH, and KY, and by NIH grants DK57751, DK45710, DK34989, and DK61747 to MHN, and YCCI (ULRR024139) and DK082600 to YI.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflict of interest to disclose for all authors.

References

- 1.Stewart BK, Kleihues P. World Cancer Report, World Health Organization, International Agency of Research on Cancer. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. Colorectal Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grady WM, Carethers JM. Genomic and epigenetic instability in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1079–1099. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taketo MM, Edelmann W. Mouse models of colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:780–798. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Leite MF, et al. Nucleoplasmic calcium is required for cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:17061–17068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700490200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendes CC, Gomes DA, Thompson M, et al. The type III inositol 1, 4,5-trisphosphate receptor preferentially transmits apoptotic Ca2+ signals into mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:40892–40900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitfield JF. Calcium, calcium-sensing receptor and colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;275:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibao K, Hirata K, Robert ME, Nathanson MH. Loss of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors from bile duct epithelia is a common event in cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01201-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minagawa N, Nagata J, Shibao K, et al. Cyclic AMP regulates bicarbonate secretion in cholangiocytes through release of ATP into bile. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1592–1602. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehmerle W, Splittgerber U, Lazarus MB, et al. Paclitaxel induces calcium oscillations via an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and neuronal calcium sensor 1-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:18356–18361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607240103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varshney A, Ehrlich BE. Intracellular Ca2+ signaling and human disease: the hunt begins with Huntington’s. Neuron. 2003;39:195–197. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomes DA, Rodrigues MA, Leite MF, et al. c-Met must translocate to the nucleus to initiate calcium signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:4344–4351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706550200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Andrade VA, Leite MF, Nathanson MH. Insulin induces calcium signals in the nucleus of rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2008;48:1621–1631. doi: 10.1002/hep.22424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mignery GA, Sudhof TC, Takei K, De Camilli P. Putative receptor for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate similar to ryanodine receptor. Nature. 1989;342:192–195. doi: 10.1038/342192a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wojcikiewicz RJ. Type I, II, and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are unequally susceptible to down-regulation and are expressed in markedly different proportions in different cell types. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11678–11683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagar RE, Burgstahler AD, Nathanson MH, Ehrlich BE. Type III InsP3 receptor channel stays open in the presence of increased calcium. Nature. 1998;396:81–84. doi: 10.1038/23954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirata K, Pusl T, O’Neill AF, Dranoff JA, Nathanson MH. The type II inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor can trigger Ca2+ waves in rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1088–1100. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathanson MH, Fallon MB, Padfield PJ, Maranto AR. Localization of the type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in the Ca2+ wave trigger zone of pancreatic acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:4693–4696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirata K, Dufour JF, Shibao K, et al. Regulation of Ca(2+) signaling in rat bile duct epithelia by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms. Hepatology. 2002;36:284–926. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez E, Leite MF, Guerra MT, et al. The spatial distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms shapes Ca2+ waves. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10057–10067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700746200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuichi T, Shiota C, Mikoshiba K. Distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor mRNA in mouse tissues. FEBS Lett. 1990;267:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80294-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujino I, Yamada N, Miyawaki A, Hasegawa M, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K. Differential expression of type 2 and type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor mRNAs in various mouse tissues: in situ hybridization study. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;280:201–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00307790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blondel O, Takeda J, Janssen H, Seino S, Bell GI. Sequence and functional characterization of a third inositol trisphosphate receptor subtype, IP3R-3, expressed in pancreatic islets, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and other tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:11356–11363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yule DI, Ernst SA, Ohnishi H, Wojcikiewicz RJ. Evidence that zymogen granules are not a physiologically relevant calcium pool. Defining the distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in pancreatic acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9093–9098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito K, Miyashita Y, Kasai H. Micromolar and submicromolar Ca2+ spikes regulating distinct cellular functions in pancreatic acinar cells. EMBO J. 1997;16:242–251. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan AA, Soloski MJ, Sharp AH, et al. Lymphocyte apoptosis: mediation by increased type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Science. 1996;273:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehning D, Patterson RL, Sedaghat L, Glebova NO, Kurosaki T, Snyder SH. Cytochrome c binds to inositol (1,4,5) trisphosphate receptors, amplifying calcium-dependent apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:1051–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Fox CJ, Master SR, et al. Bcl-X(L) affects Ca(2+) homeostasis by altering expression of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:9830–9835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152571899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bassik MC, Scorrano L, Oakes SA, Pozzan T, Korsmeyer SJ. Phosphorylation of BCL-2 regulates ER Ca2+ homeostasis and apoptosis. EMBO J. 2004;23:1207–1216. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minagawa N, Kruglov EA, Dranoff JA, Robert ME, Gomes GJ, Nathanson MH. The anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 inhibits mitochondrial Ca2+ signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33637–33644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larini F, Menegazzi P, Baricordi O, Zorzato F, Treves S. A ryanodine receptor-like Ca2+ channel is expressed in nonexcitable cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lail-Trecker MR, Peluso CE, Peluso JJ. Hepatocyte growth factor disrupts cell contact and stimulates an increase in type 3 inositol triphosphate receptor expression, intracellular calcium levels, and apoptosis of rat ovarian surface epithelial cells. Endocrine. 2000;12:303–314. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:12:3:303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maximov A, Tang TS, Bezprozvanny I. Association of the type 1 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor with 4.1N protein in neurons. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:271–283. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagata J, Guerra MT, Shugrue CA, et al. Lipid rafts establish calcium waves in hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:256–267. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerasimenko JV, Lur G, Sherwood MW, et al. Pancreatic protease activation by alcohol metabolite depends on Ca2+ release via acid store IP3 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:10758–10763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904818106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheung KH, Shineman D, Muller M, et al. Mechanism of Ca2+ disruption in Alzheimer’s disease by presenilin regulation of InsP3 receptor channel gating. Neuron. 2008;58:871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang TS, Guo C, Wang H, Chen X, Bezprozvanny I. Neuroprotective effects of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor C-terminal fragment in a Huntington’s disease mouse model. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:1257–1266. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4411-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakakura C, Miyagawa K, Fukuda K, et al. Possible involvement of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 3 (IP3R3) in the peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancers. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3691–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]