Abstract

Terrestrial arthropods are often infected with heritable bacterial symbionts, which may themselves be infected by bacteriophages. However, what role, if any, bacteriophages play in the regulation and maintenance of insect–bacteria symbioses is largely unknown. Infection of the aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum by the bacterial symbiont Hamiltonella defensa confers protection against parasitoid wasps, but only when H. defensa is itself infected by the phage A. pisum secondary endosymbiont (APSE). Here, we use a controlled genetic background and correlation-based assays to show that loss of APSE is associated with up to sevenfold increases in the intra-aphid abundance of H. defensa. APSE loss is also associated with severe deleterious effects on aphid fitness: aphids infected with H. defensa lacking APSE have a significantly delayed onset of reproduction, lower weight at adulthood and half as many total offspring as aphids infected with phage-harbouring H. defensa, indicating that phage loss can rapidly lead to the breakdown of the defensive symbiosis. Our results overall indicate that bacteriophages play critical roles in both aphid defence and the maintenance of heritable symbiosis.

Keywords: endosymbionts, APSE, bacteriophage, proteobacteria, Hamiltonella, Wolbachia

1. Introduction

Bacteriophages are the most abundant biological entities on the Earth, and they perform key ecological functions at scales ranging from local to global [1]. Among free-living bacteria, phages can influence host population dynamics via host cell lysis and other mechanisms, which can affect community structure. Temperate phages often encode functional pathways, such as antibiotic resistance or virulence factors, which enhance bacterial host fitness, and vector these traits within and among bacterial lineages [2]. Many bacterial lineages, however, persist only in association with animal cells. Heritable bacterial infections, for example, are widespread among terrestrial arthropods, where many have evolved into beneficial symbionts that provide nutritional or defensive services [3,4]. Several heritable symbionts also harbour phage infections, yet the prevalence and roles of phages in heritable symbioses remain poorly understood [5,6].

A bacteriophage named Acyrthosiphon pisum secondary endosymbiont (APSE) infects Hamiltonella defensa, a gamma-proteobacterial symbiont of aphids and related insects [7–10]. APSEs are temperate bacteriophages related to the lambdoid phage P22 (Podoviridae) [7,11]. There are two APSE variants (APSE-2 and APSE-3) commonly found in North American populations of A. pisum. Each variant shares a core of conserved genes but also contains a variable region consisting of holin, lysozyme and toxin genes from two protein families: cytolethal distending toxin (CdtB; APSE-2), and YD-repeat toxin (Ydp; APSE-3) [8,9]. Phylogenetic evidence shows that APSEs move these pathways horizontally between H. defensa lineages [9]. Prior studies with the pea aphid, A. pisum, established that H. defensa confers protection against an important natural enemy, the parasitic wasp Aphidius ervi, by killing wasp offspring that otherwise develop within the aphid haemocoel [12,13]. This protective phenotype was further found to depend on whether the bacterial symbiont was infected by APSE, and to differ with phage variant: H. defensa strains carrying APSE-3 confer near-complete resistance and those with APSE-2 confer partial resistance [10,14].

Given the lytic capabilities of phages, APSEs and other temperate viruses have the potential to influence symbiont abundance in insect hosts. Within-host bacterial abundance can affect conferred phenotypes [15,16], rates of horizontal transfer and establishment of novel infections [17], and maintenance of tripartite symbioses [18,19]. All stable beneficial heritable symbiont infections must also be coordinated between host and symbiont(s) to strike a balance between sufficient titre to produce the beneficial phenotype and ensure vertical transmission to progeny, while limiting over-replication that might be detrimental to host fitness [19]. The mechanisms underlying the regulation of heritable symbionts, however, are poorly understood. Hosts may restrict symbionts to particular tissues and the host immune system may regulate symbiont infection [20–22], though some facultative symbionts maintain a pathogen-like capacity for colonization of novel host tissues. Symbionts, in turn, may use chemical communication (e.g. quorum sensing) to assess titres, but quorum sensing has been characterized in only one heritable insect symbiont, Sodalis [23]. Temperature has also been shown to affect within-host density of endosymbionts in several insects [24], including wasps in the genus Nasonia, where temperature decreases the abundance of Wolbachia but increases the abundance of the phage WO [18]. We became interested in the role of APSE in regulation of H. defensa densities when we anecdotally observed that haemolymph from A. pisum infected with H. defensa lacking APSE contained higher densities of this symbiont than aphids infected by H. defensa with APSE. To elaborate on this observation, we conducted a set of experimental and correlation-based studies to examine whether APSE was responsible for reducing symbiont titres, and if so, whether phage loss and symbiont deregulation affect aphid fitness.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study organisms

Acyrthosiphon pisum is a cosmopolitan pest of herbaceous legumes, including important forage crops [25]. In most temperate regions, A. pisum is cyclically parthenogenetic; aphids reproduce asexually and viviparously for most of the growing season, and only in response to a shortening photoperiod in autumn are sexual morphs produced, which lay overwintering eggs [26]. In the laboratory, clonal lines can be maintained indefinitely by mimicking long day-length conditions. Single parthenogenetic females collected from the field were used to initiate the lines in this study (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). All aphids were reared on Vicia faba on a 16 L : 8 D cycle at temperature of 19±1°C.

In laboratory-reared pea aphid clones, H. defensa is vertically transmitted at rates approaching 100 per cent [4]. APSE-3 infections are also transmitted with very high fidelity, but can be spontaneously lost at very low rates [14]. We therefore used previously established sub-lines from the aphid clone 5A that had been inoculated with the APSE-3-harbouring H. defensa strain A1A (A1A+ → 5A), some sub-lines of which subsequently lost APSE-3 (A1A− → 5A) [14]. Lines 82B → 5A-1 and 82B → 5A-2 were established by a single transfer of H. defensa (82B, collected in Cayuga Co, NY 2000) via microinjection into line 5A, but parthenogenetically reproducing lines were maintained separately for at least 3 years [13]. All other aphid clonal lines used in this study contained their natural symbiont infections (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1).

(b). APSE effects on Hamiltonella defensa titres

(i) To determine whether phage loss influences symbiont abundance, we used real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) to compare H. defensa titres in aphids that share the same genotype and symbiont strain, but that differed in status of phage infection (A1A± → 5A). To create cohorts of equal-aged aphids, between 10 and 15 actively reproducing female A. pisum were placed on a single V. faba plant. The 24 h cohorts were produced within ±2 h, all other cohorts (i.e. 48–336 h) were produced within ±4 h. Aphids were destructively sampled and each time point represents a unique cohort. Quantities of aphid symbiont levels at different time points during development (24–336 h) were then determined by preparing whole aphid DNA extractions in a lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–Cl, pH 8.2; 1 mM EDTA; 25 mM NaCl) with 1 per cent proteinase K (20 mg ml−1) scaled by aphid size from 10 μl for a first instar aphid to 100 μl for adults [27]. Standard curves for quantification were produced via serial dilutions from 1E2 to 1E9 [28], and efficiencies for all quantification reactions were above 93 per cent. After extraction, aphids from line A1A+ → 5A were first tested using diagnostic PCR to confirm phage infection (primers and reaction conditions in table 1). Unique fragments of the single-copy gene dnaK were used to quantify the abundance of H. defensa by qPCR (table 1). For all aphid ages except for 336 h, the relative bacterial and phage titres were calibrated using the aphid gene EF1α to account for differences in extraction efficiency and body size. All 10 μl reactions were performed on a Roche LightCycler 480 II using Roche LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master chemistry and 0.5 μM of each primer. Preincubation: 95°C for 5 min; amplification (repeated 45 times): 95°C for 10 s, 68°C to 55°C touchdown with 10 steps each at 1°C, 72°C for 10 s; melting curve: 95°C for 5 s, 65°C for 1 min, then ramped to 97°C; hold at 40°C.

(ii) We also discovered that one sub-line of clone A1A+ → 5A produced a small percentage of offspring infected with H. defensa but without APSE-3. This finding allowed us to examine the differences in symbiont titre between phage negative and phage positive siblings from the same (phage positive) mother. We used qPCR, as described earlier, to estimate H. defensa titres from 24 ± 2 h APSE-infected and APSE-free offspring produced by a single mother aphid. Diagnostic PCR was used to determine phage infection status.

(iii) Diagnostic screening identified additional laboratory-held clonal A. pisum lines that were either fixed for or lacked APSE-3 (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). Using the same protocols, we conducted qPCR on 72 ± 4 h offspring of four clones infected with H. defensa plus APSE-3 and three clones without APSE to determine if phage-free lines generally have higher H. defensa titres than phage-infected lines.

(iv) The other common North American phage variant, APSE-2, has never been reported lost from a laboratory-held line, preventing us from directly assessing the effects of APSE-2 loss on H. defensa abundance. However, we were able to examine two lines that shared the same aphid clonal background (5A), strain of H. defensa (82B) and haplotype of APSE-2, but which had been reared as separate parthenogenetically reproducing colonies for at least 3 years. Using qPCR as described earlier, we estimated H. defensa and APSE-2 titres (amplifying a unique fragment of APSE gene P28; table 1) at two time points in aphid development: 96 h (third instar) and 144 h (fourth instar) nymphs.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used with diagnostic and quantitative procedures.

| target gene (source organism) | 5′-primer sequences-3′ | primer and reaction source |

|---|---|---|

| P2 (bacteriophage APSE) | F: GTC CAG GCA TTA TTA GCG C | [8] |

| R: TTT TTC TAA GGC AAC CAT | ||

| P28 (bacteriophage APSE) | F: TGA TAA AAG CGG ATA ATG CC | [8] |

| R: GCG TTT GTC ATA CTG AAA AGG | ||

| cdtB (variant APSE-2) | F: ATA TTT TTT TTA CCG CCC CG | [8] |

| R: CCA GCT TCA TTT CTA CCA CCT C | ||

| Ydp (variant APSE-3) | F: CGC CCA CGC CCT CAA CGA TT | this study |

| R: CTG GCC GGC CTT TGA CCA GG | ||

| dnaK (Hamiltonella defensa) | F: GGT TCA GAA AAA AGT GGC AG | [8] |

| R: CGA GCG AAA GAG GAG TGA | ||

| ef1α (Acyrthosiphon pisum) | F: CTG ATT GTG CCG TGC TTA TTG | [35] |

| R: TAT GGT GGT TCA GTA GAG TCC |

(c). Effects of phage loss on aphid fitness

To assess the effects of phage loss on aphid fitness, we compared three aphid fitness parameters (fecundity, development time and fresh weight at adulthood) in our experimental lines (A1A± → 5A) that shared the same genotype and symbiont strain, but differed in phage infection status. Fitness assays were conducted as in Oliver et al. [28]. For each replicate (n = 10) of the fecundity assay, a cohort of four similarly aged (±16 h), pre-reproductive, apterous female aphids were placed on a single V. faba plant in an isolated cup cage. Offspring were counted and removed every 3 days after the onset of reproduction. The number of surviving adults from the initial cohort was also noted at each time point until day 26. At this point, most aphids had ceased reproducing and more than a quarter of all cohorts had no surviving adults. Plants were changed occasionally to promote optimal conditions for aphid development. We also examined development time, defined here as time from birth to first reproduction (TFR). To determine TFR, nymphs were moved to new plants after birth (±1.5 h) and, starting at 7 days post-birth, were monitored every 3 h during the light cycle until all reproduced. Adult fresh weight of apterous aphids was taken at time of first reproduction.

(d). Fidelity of Hamiltonella defensa and APSE transmission

(i) The vertical transmission rate of H. defensa is near 100 per cent under standard laboratory conditions (approx. 20°C, 16 L : 8 D) [4], but no comparison of H. defensa transmission rates has been reported for lines with and without APSE. To do this, we regularly screened all lines in the electronic supplementary material, table S1 for H. defensa infection via diagnostic PCR (table 1). Laboratory-based cage experiments show that uninfected aphids spread at the expense of H. defensa-infected aphids [29], which would increase the likelihood of detecting any instances of symbiont loss.

(ii) We also determined the phage variant of each line (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1) using primers (table 1) that amplify fragments of the cdtB and Ydp genes, which are found on APSE-2 and APSE-3, respectively. To examine vertical transmission of APSEs, these lines were regularly screened for phage presence using the P2 and P28 primers (table 1).

(e). Data analysis

All within-treatment qPCR estimates of symbiont titres, except for the 192 h time point in the experimental line comparisons (§2b(i)), were normally distributed. Thus, comparisons among treatments were analysed by ANOVA. Confidence intervals presented in figure 1 were calculated with unpooled variance. Because our phage-infected and phage-uninfected treatments for 192 h exhibited a log-normal distribution, we log-transformed these data prior to ANOVA. The resulting means and confidence intervals were then back transformed for presentation in figure 1a. For cross-line comparisons of symbiont abundances (§2b(iii)), we conducted an ANOVA to compare all phage-infected and phage-free lines, followed by a post hoc Tukey–Kramer HSD test to assess which mean differences were significant. For our fitness assays (§2c), lifetime fecundity and fresh weight were normally distributed and subjected to t-tests, whereas TFR was non-normally distributed, which necessitated our use of a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP v. 8.0.2 platform (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007).

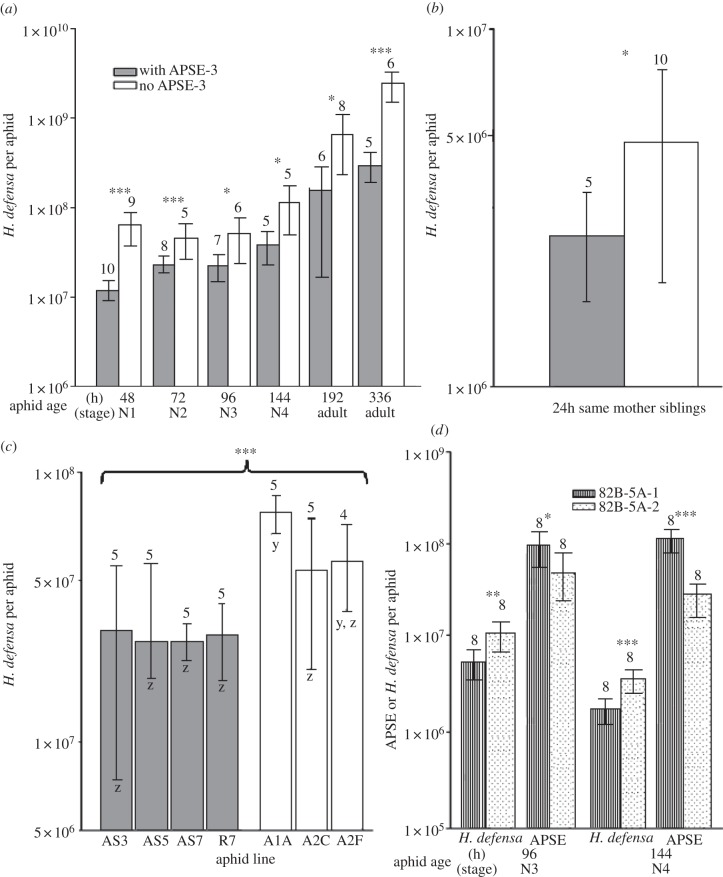

Figure 1.

Bacteriophage APSE affects H. defensa abundance. (N denotes nymphal instar, t-test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.) Columns represent mean symbiont abundances for APSE-3 infected (dark) and phage-free (open) treatments: numbers above columns indicate number of aphids in the treatment. Bars represent 95% CIs. (a) H. defensa titres in experimental line A1A+ → 5A (aphid clone 5A infected with H. defensa A1A and with phage APSE-3) versus line A1A− → 5A (aphid clone 5A infected with H. defensa A1A but without phage APSE-3). (b) H. defensa titres in siblings from the experimental line demonstrating changed H. defensa titres within a single generation. All aphids, with and without phage, used for the 24 h time point were the offspring of a single A1A+ → 5A mother. (c) H. defensa titres in 72 h (second instar) clonal lineages with and without APSE-3. ANOVA comparison of summed phage-infected group to summed phage-free group is presented at top; individual lines were compared via post hoc Tukey–Kramer HSD: shared letters (y or z) indicate levels not significantly different. (d) APSE-2 and H. defensa in lines 82B → 5A-1 and 82B → 5A-2.

3. Results

(a). APSE-3 loss is associated with increases in Hamiltonella defensa titre

The A1A → 5A sub-lines, identical in aphid genotype and H. defensa strain but differing in APSE-3 infection status, allowed us to experimentally investigate the consequences of phage loss. Our qPCR estimates of symbiont abundance revealed that phage-free aphids contained significantly more H. defensa than aphids with APSE-3 at all examined time points in aphid development (figure 1a). Hamiltonella defensa titres rose throughout aphid development, such that older aphids lacking APSE contained much larger numbers of H. defensa than adult aphids with phage (figure 1a).

(b). Phage loss results in immediate increases in Hamiltonella defensa titres

In a sub-line of clone A1A+ → 5A, which infrequently produced APSE-free offspring, we compared symbiont titres of 24 h offspring produced by a single APSE-3/H. defensa positive mother and found that nymphs lacking APSE-3 carried on average 83 per cent more H. defensa than their phage-harbouring sisters (figure 1b; ANOVA, F1,14 = 6.0, p = 0.03), indicating that phage loss results in immediate increases in H. defensa abundance per aphid.

(c). Phage-free lines generally exhibit higher Hamiltonella defensa titres

We screened 72 h offspring of laboratory-held lines infected with H. defensa and APSE-3, and lines infected with phage-free H. defensa (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1) to determine whether phage-free lines generally contain higher symbiont titres. We found that clones lacking APSE-3 contained on average more than twice the number of H. defensa per aphid than clones with APSE-3 (figure 1c; ANOVA F6,33 = 11.85, p < 0.0001).

(d). APSE-2 and Hamiltonella defensa titres have an inverse relationship

To determine whether APSE-2 also influenced symbiont titres, we assessed the abundance of H. defensa and phage in lines sharing the same aphid background (5A) and same H. defensa strain and APSE-2 haplotype (from line 82B). We found that aphids from the 82B → 5A-1 line contained more APSE-2 than aphids from the 82B → 5A-2 line (figure 1d). Conversely, the abundance of H. defensa was significantly lower in 82B → 5A-1 aphids than 82B → 5A-2 aphids (figure 1d), indicating an inverse association between phage and symbiont titre.

(e). APSE loss has severely deleterious effects on measures of aphid fitness

The loss of APSE and concomitant rise in the abundance of H. defensa could affect aphid fitness. To test this idea, we used the A1A+ → 5A and A1A− → 5A aphid sub-lines, which were genetically identical and contained the same strain of H. defensa but differed in whether or not they contained APSE-3. We then measured three fitness parameters: fecundity, development time and fresh weight at adulthood. In each instance, our results showed that the absence of APSE-3 significantly increased fitness costs to the aphid host (table 2). Aphids lacking APSE-3 (line A1A− → 5A) reproduced, on average, 18 h later than A1A+ → 5A aphids with APSE-3. They also weighed 20 per cent less than their phage-harbouring counterparts at adulthood, and produced roughly half as many offspring (table 2).

Table 2.

Aphid fitness assays in experimental lines with APSE (A1A+ → 5A) and without APSE (A1A− → 5A). (Includes maternal age (h) at time of first live offspring produced, maternal mass immediately after first reproduction and total offspring produced by cohorts of four adult aphids by age 26 days. The statistical test used for each fitness measure is shown in the right column. p-values in each case were also highly significant. Means are in bold text.)

| assay | + APSE-3 | − APSE-3 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time to first reproduction (h) | range | 189.5–236.5 | 199.5–236.5 | 0.000006 (Wilcoxon rank-sum) |

| mean | 205.87 | 223.20 | ||

| aphids | 19 | 20 | ||

| fresh weight (mg) | range | 2.74–4.29 | 1.99–4.01 | 0.0002 (t-test) |

| mean | 3.79 | 3.17 | ||

| aphids | 19 | 20 | ||

| offspring per cage by day 26 | range | 116–335 | 66–183 | <0.0001 (t-test) |

| mean | 237 | 122 | ||

| cages | 10 | 10 |

(f). Hamiltonella defensa is vertically transmitted with high fidelity with and without APSE

We have held numerous H. defensa-infected lines with and without APSE in continuous culture for many years (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1), and despite routine screening, we have not detected any losses of H. defensa. On the basis of a conservative average of 30 generations per year, we calculated the number of generations with successful vertical transmission [30]. We estimated 1470 generations of successful transfer in APSE-3 infected lines and 540 generations in APSE-free H. defensa-infected lines.

(g). APSE-2 has higher vertical transmission fidelity than APSE-3

We currently maintain 16 aphid lines bearing APSE-2–H. defensa, most of which have been held for at least 1 year, and despite routine screening, we have documented no instances of APSE-2 loss, including in one line held, in multiple subclones, for more than 12 years. By contrast, we have held at least 10 lines infected with APSE-3, and most have lost phage within 4 years (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1).

4. Discussion

By controlling aphid genotype, symbiont genotype and environmental conditions, such as temperature, this study shows that APSE reduces within-host densities of H. defensa. In lines with identical aphid genotypes and H. defensa strains, APSE loss resulted in significant increases in H. defensa titre across all examined time points ranging from first instar nymphs to adults (figure 1a). While it is possible that additional changes (other than APSE loss) which influence H. defensa abundance have occurred in our clonal experimental lines, our finding that APSE-free offspring contain fewer H. defensa than their APSE-3-harbouring siblings (figure 1b), strongly suggests that phage loss results in immediate increases in symbiont titres in this line (figure 1b) and that APSE loss alone is a sufficient explanation for H. defensa titre differences we observe in the experimental lines. Furthermore, among genetically diverse A. pisum lines, those lacking APSE-3 consistently contain roughly twice the number of H. defensa as lines maintaining the phage (figure 1c). These experimental and correlation-based findings indicate that APSE-3 infection significantly reduces the abundance of H. defensa in A. pisum. While no APSE-2 loss event has been reported, genetically identical aphid sub-lines with the same strain of H. defensa have H. defensa titres inversely associated with APSE-2 titre. This inverse relationship is consistent with the lysis of H. defensa by APSE-2, and, along with our APSE-3 results, suggests that APSE-2 also reduces the abundance of H. defensa in A. pisum.

We also found that the higher H. defensa titres associated with phage loss correlated with severe fitness costs to A. pisum. In our experimental line sharing H. defensa strain and aphid genotype, phage-free H. defensa-infected aphids developed more slowly, reached a smaller fresh weight at adulthood, and produced approximately 50 per cent fewer offspring than their APSE-3-infected counterparts (table 2). The underlying cause of these costs was not investigated, but H. defensa is auxotrophic for most essential amino acids and probably relies on the aphid and its obligate nutritional symbiont Buchnera aphidicola for growth [31], and increases in H. defensa abundance may reduce resources available for aphid growth and reproduction.

Costs associated with phage loss may play an important role in the maintenance of this protective symbiosis. Hamiltonella defensa is found at intermediate frequencies in nature [28,32] and most field-collected H. defensa-infected aphids are also infected by APSE [14,33]. Population cage studies reveal that aphids infected with H. defensa and APSE-3 rapidly spread to near-fixation when parasitism pressure is present, whereas uninfected aphids are favoured in the absence of parasitism [29]. Thus, aphids infected with H. defensa plus APSE have a fitness advantage over uninfected aphids when exposed to parasitism pressure, owing to the resistance traits APSE encodes. By contrast, aphids infected by H. defensa alone derive no protection from parasitism and incur higher fitness costs than aphids infected by H. defensa plus APSE. Moreover, while individual H. defensa cells could benefit from the absence of APSE infection, the within-host reductions in symbiont density APSE causes do not appear to adversely affect transmission fidelity, as symbiont inheritance approaches 100 per cent under standard laboratory conditions whether or not APSE is present. We conclude that APSE is probably essential for maintenance of the H. defensa–aphid symbiosis because its loss favours reductions in the prevalence of symbiont-infected aphids under conditions of both high and low parasitism pressure. APSE is therefore a vital component in the H. defensa–aphid symbiosis not only because of the pathways it encodes but also for its ability to regulate symbiont density without compromising transmission fidelity. The loss of this bacteriophage, by contrast, leads to an immediate proliferation of bacterial symbionts, deleterious effects on the animal host and the rapid breakdown of the heritable symbiosis.

The fitness costs of phage loss to aphids may also explain why aphids harbouring APSE-2 are maintained in natural populations despite being inferior protectors against parasitism. We found that, in the laboratory, APSE-2–H. defensa interactions appear more stable than those involving APSE-3, albeit in a limited sample (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). The underlying basis for the differential persistence of APSE-2 and -3 is currently unclear. The reduction in H. defensa titre that occurs with phage infection suggests both phage variants undergo lytic cycles, but both also persist in H. defensa as integrated prophages [10]. Thus, differences in the timing of lytic and lysogenic activity during the life cycle of the aphid or H. defensa may underlie the differential persistence of these APSE variants. Given evidence that higher temperatures reduce the protective benefits of H. defensa, abiotic factors may play a role in the within-host dynamics between APSE and H. defensa [34]. Studies with Nasonia also show that temperature shock reduces the abundance of Wolbachia while increasing the abundance of phage WO [18].

In general, phage infections have the potential to exert dynamic and profound influences on animal–bacterial symbioses. In addition to encoding pathways that benefit both the bacterial and animal hosts [8,10,14], bacteriophages may alter symbiont abundance within individual hosts and thereby play critical roles in the maintenance of heritable symbiosis within host populations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicole Ferguson, Nasreen Bano and Eric Katz for technical assistance. This project was supported by a National Science Foundation (IOS) grant no. 1050128 to K.M.O. Data presented in this paper are available at doi:10.5061/dryad.fc546.

References

- 1.Weinbauer MG. 2004. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28, 127–181 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001 (doi:10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clokie MRJ, Millard AD, Letarov AV, Heaphy S. 2011. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage 1, 31–45 10.4161/bact.1.1.14942 (doi:10.4161/bact.1.1.14942) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran NA, McCutcheon JP, Nakabachi A. 2008. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 165–190 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130119 (doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130119) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver KM, Degnan PH, Burke GR, Moran NA. 2010. Facultative symbionts in aphids and the horizontal transfer of ecologically important traits. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55, 247–266 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085305 (doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085305) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belda E, Moya A, Bentley S, Silva FJ. 2010. Mobile genetic element proliferation and gene inactivation impact over the genome structure and metabolic capabilities of Sodalis glossinidius, the secondary endosymbiont of tsetse flies. BMC Genomics 11, 449. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-449 (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-449) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darby AC, Choi JH, Wilkes T, Hughes MA, Werren JH, Hurst GDD, Colbourne JK. 2010. Characteristics of the genome of Arsenophonus nasoniae, son-killer bacterium of the wasp Nasonia. Insect Mol. Biol. 19, 75–89 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00950.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00950.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Wilk F, Dullemans AM, Verbeek M, van den Heuvel JFJM. 1999. Isolation and characterization of APSE-1, a bacteriophage infecting the secondary endosymbiont of Acyrthosiphon pisum. Virology 262, 104–113 10.1006/viro.1999.9902 (doi:10.1006/viro.1999.9902) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran NA, Degnan PH, Santos SR, Dunbar HE, Ochman H. 2005. The players in a mutualistic symbiosis: insects, bacteria, viruses, and virulence genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16 919–16 926 10.1073/pnas.0507029102 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0507029102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degnan PH, Moran NA. 2008. Evolutionary genetics of a defensive facultative symbiont of insects: exchange of toxin-encoding bacteriophage. Mol. Ecol. 17, 916–929 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03616.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03616.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degnan PH, Moran NA. 2008. Diverse phage-encoded toxins in a protective insect endosymbiont. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6782–6791 10.1128/Aem.01285-08 (doi:10.1128/Aem.01285-08) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandstrom JP, Russell JA, White JP, Moran NA. 2001. Independent origins and horizontal transfer of bacterial symbionts of aphids. Mol. Ecol. 10, 217–228 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01189.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01189.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver KM, Moran NA, Hunter MS. 2005. Variation in resistance to parasitism in aphids is due to symbionts not host genotype. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 12 795–12 800 10.1073/pnas.0506131102 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0506131102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver KM, Russell JA, Moran NA, Hunter MS. 2003. Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1803–1807 10.1073/pnas.0335320100 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0335320100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver KM, Degnan PH, Hunter MS, Moran NA. 2009. Bacteriophages encode factors required for protection in a symbiotic mutualism. Science 325, 992–994 10.1126/science.1174463 (doi:10.1126/science.1174463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda T, Ishikawa H, Sasaki T. 2003. Infection density of Wolbachia and level of cytoplasmic incompatibility in the Mediterranean flour moth, Ephestia kuehniella. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 84, 1–5 10.1016/S0022-2011(03)00106-X (doi:10.1016/S0022-2011(03)00106-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noda H, Koizumi Y, Zhang Q, Deng KJ. 2001. Infection density of Wolbachia and incompatibility level in two planthopper species, Laodelphax striatellus and Sogatella furcifera. Insect Biochem. Mol. 31, 727–737 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00180-6 (doi:10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00180-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chafee ME, Funk DJ, Harrison RG, Bordenstein SR. 2010. Lateral phage transfer in obligate intracellular bacteria (Wolbachia): verification from natural populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 501–505 10.1093/molbev/msp275 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msp275) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bordenstein SR, Bordenstein SR. 2011. Temperature affects the tripartite interactions between bacteriophage WO, Wolbachia, and cytoplasmic incompatibility. PLoS ONE 6, e29106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029106 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaenike J. 2009. Coupled population dynamics of endosymbionts within and between hosts. Oikos 118, 353–362 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17110.x (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17110.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchner P. 1965. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms, xvii, 909 pp. Rev. Eng. edn. New York, NY: Interscience Publishers [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran NA, Russell JA, Koga R, Fukatsu T. 2005. Evolutionary relationships of three new species of Enterobacteriaceae living as symbionts of aphids and other insects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3302–3310 10.1128/Aem.71.6.3302-3310.2005 (doi:10.1128/Aem.71.6.3302-3310.2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Login FH, Balmand S, Vallier A, Vincent-Monegat C, Vigneron A, Weiss-Gayet M, Rochat D, Heddi A. 2011. Antimicrobial peptides keep insect endosymbionts under control. Science 334, 362–365 10.1126/science.1209728 (doi:10.1126/science.1209728) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pontes MH, Babst M, Lochhead R, Oakeson K, Smith K, Dale C. 2008. Quorum sensing primes the oxidative stress response in the insect endosymbiont, Sodalis glossinidius. PLoS ONE 3, e3541. 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0003541 (doi:10.1371/Journal.Pone.0003541) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurst GDD, Johnson AP, von der Schulenburg JHG, Fuyama Y. 2000. Male-killing Wolbachia in Drosophila: a temperature-sensitive trait with a threshold bacterial density. Genetics 156, 699–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Emden HF, Harrington R. 2007. Taxonomic issues. In Aphids as crop pests (eds van Emden HF, Harrington R.), pp. 1–29 Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brisson JA, Stern DL. 2006. The pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum: an emerging genomic model system for ecological, developmental and evolutionary studies. Bioessays 28, 747–755 10.1002/bies.20436 (doi:10.1002/bies.20436) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gloor GB, Preston CR, Johnsonschlitz DM, Nassif NA, Phillis RW, Benz WK, Robertson HM, Engels WR. 1993. Type-I repressors of p-element mobility. Genetics 135, 81–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver KM, Moran NA, Hunter MS. 2006. Costs and benefits of a superinfection of facultative symbionts in aphids. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1273–1280 10.1098/rspb.2005.3436 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3436) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliver KM, Campos J, Moran NA, Hunter MS. 2008. Population dynamics of defensive symbionts in aphids. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 293–299 10.1098/rspb.2007.1192 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1192) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moran NA, Dunbar HE. 2006. Sexual acquisition of beneficial symbionts in aphids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12 803–12 806 10.1073/pnas.0605772103 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0605772103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degnan PH, Yu Y, Sisneros N, Wing RA, Moran NA. 2009. Hamiltonella defensa, genome evolution of protective bacterial endosymbiont from pathogenic ancestors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9063–9068 10.1073/pnas.0900194106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0900194106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrari J, West JA, Via S, Godfray HCJ. 2012. Population genetic structure and secondary symbionts in host-associated populations of the pea aphid complex. Evolution 66, 375–390 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01436.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01436.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell J, et al. In press Uncovering symbiont-driven genetic diversity across North American pea aphids. Mol. Ecol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bensadia F, Boudreault S, Guay JF, Michaud D, Cloutier C. 2006. Aphid clonal resistance to a parasitoid fails under heat stress. J. Insect Physiol. 52, 146–157 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2005.09.011 (doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2005.09.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson ACC, Dunbar HE, Davis GK, Hunter WB, Stern DL, Moran NA. 2006. A dual-genome microarray for the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, and its obligate bacterial symbiont, Buchnera aphidicola. BMC Genomics 7, 50. 10.1186/1471-2164-7-50 (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-7-50) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]