Abstract

Differentiation is accompanied by extensive epigenomic reprogramming, leading to the repression of stemness factors and the transcriptional maintenance of activated lineage-specific genes. Here we use the mammalian Hoxa cluster of developmental genes as a model system to follow changes in DNA modification patterns during retinoic acid induced differentiation. We find the inactive cluster to be marked by defined patterns of 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Upon the induction of differentiation, the active anterior part of the cluster becomes increasingly enriched in 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), following closely the colinear activation pattern of the gene array, which is paralleled by the reduction of 5mC. Depletion of the 5hmC generating dioxygenase Tet2 impairs the maintenance of Hoxa activity and partially restores 5mC levels. Our results indicate that gene specific 5mC-5hmC conversion by Tet2 is crucial for the maintenance of active chromatin states at lineage-specific loci.

Keywords: DNA methylation, Hoxa cluster, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, epigenetic maintenance, Ten-Eleven-Translocation 2 (Tet2)

Introduction

In the developing mammalian embryo the characteristic features of the body plan are defined by the coordinated expression of homeotic (Hox) genes in an anterior-posterior order. Hox genes show a clustered organization where the arrangement of transcription units on the chromosome often mirrors their spatiotemporal expression domains along the anterior-posterior axis of the developing embryo1,2. These particular patterns of transcription are usually induced and regulated by morphogens, like all-trans-retinoic acid (RA), a conserved intercellular signaling molecule found in most vertebrates3. In pluripotent cell populations Hox genes are tightly repressed, but kept in a poised chromatin state that allows rapid lineage-specific expression upon morphogen induction4.

A prominent example of a poised developmental gene array is the Hoxa cluster. In stem cells, this cluster is silenced by repressive complexes of the Polycomb group (PcG) and characterised by the presence of bivalent histone methylation marks5. Hoxa activation has been extensively studied in cell culture, using embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or embryonal carcinoma (EC) cell lines6,7. In these systems, RA treatment induces colinear derepression of the anterior Hoxa genes, which is accompanied by the progressive loss of PcG proteins and repressive histone modifications8–10. Despite the presence of several CpG islands within the cluster, the role of DNA methylation in Hoxa regulation is poorly understood. The inactive Hoxa cluster was found strongly methylated in differentiated fibroblasts and monocytes, but also in cancer cell lines and tumours11–13. Nevertheless, there are also regions with significant DNA methylation throughout the cluster in undifferentiated stem cells or embryonal carcinoma cells, often coinciding with promoter regions or regulatory elements13,14.

The presence of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) at or near promoter regions of genes is thought to be mostly incompatible with activated transcription, indicating that methylated cytosines have to be removed or converted to ensure the maintenance of the active state15,16. The recent mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) in the mouse genome shed light on a potential demethylation pathway that is triggered by the conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine17,18. Additional processing steps and base-excision repair mechanisms would then result in the removal of the methylated base and its substitution with an unmethylated cytosine18. 5hmC is generated from existing 5mC by the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of proteins19,20. Two of these enzymes, Tet1 and Tet2, are significantly expressed in mouse ESCs20. Their depletion has been shown to lead to a partial loss of the undifferentiated state and to induce differentiation towards trophoectodermal, endodermal and mesodermal lineages19–21. This suggests that both proteins have an important role in maintaining pluripotency by controlling 5hmC levels and thus orchestrate the balance between stemness and lineage commitment20, 21.

In mouse embryonic stem cells 5hmC has been mostly associated with euchromatin, gene bodies and active genes21,22, suggesting that the presence of 5hmC facilitates activated transcription. Nevertheless, 5hmC and Tet1 were also found enriched in or near inactive genes with bivalent chromatin marks23–25. Here, 5hmC could prime for rapid activation, either by triggering DNA demethylation or by recruiting transcriptional regulators that recognise 5hmC23. Taken together, 5mC-5hmC conversion seems to protect active genes and poised bivalent domains from becoming permanently methylated and might be needed for fine-tuning regulated transcription and for protecting the genome from unspecific DNA methylation23,24.

Importantly, however, the presence of 5hmC is not restricted to embryonic stem cells. Tet2 is expressed in a variety of differentiated tissues, especially in the haematopoietic and neuronal lineages, in brain, neuronal progenitors and postmitotic neurons19,26–28. Furthermore, Tet2 mutations are frequent in patients with myeloid leukaemias, a group of diseases that is characterised by impaired differentiation of myeloid precursor cells29,30. Nevertheless, the functional role of cytosine hydroxymethylation during differentiation has remained unclear.

In order to study 5mC and 5hmC levels in relation to activated transcription in a defined genomic region we focused on the human HOXA cluster and followed DNA methylation patterns in the pluripotent human embryonic carcinoma cell line NTERA2 D1 during RA-induced differentiation. We found that CpG-rich regions in the anterior part of the cluster showed significant 5mC-5hmC conversion during RA-induced HOXA activation that followed the colinear gene expression pattern in NT2 cells. Small interfering RNA-mediated depletion of TET2 during RA induction impaired the maintenance of HOXA activity and partially restored genomic 5mC levels. Tissue-specific Hoxa gene expression patterns were also significantly reduced in a Tet2 knock out mouse model, suggesting a general role of Tet2 for the maintenance of active expression patterns in the cluster. These results indicate that Tet2-dependent conversion of repressive 5mC to 5hmC is crucial for the maintenance of open chromatin states and active gene expression patterns.

Results

A human embryonic carcinoma cell line as stem cell model

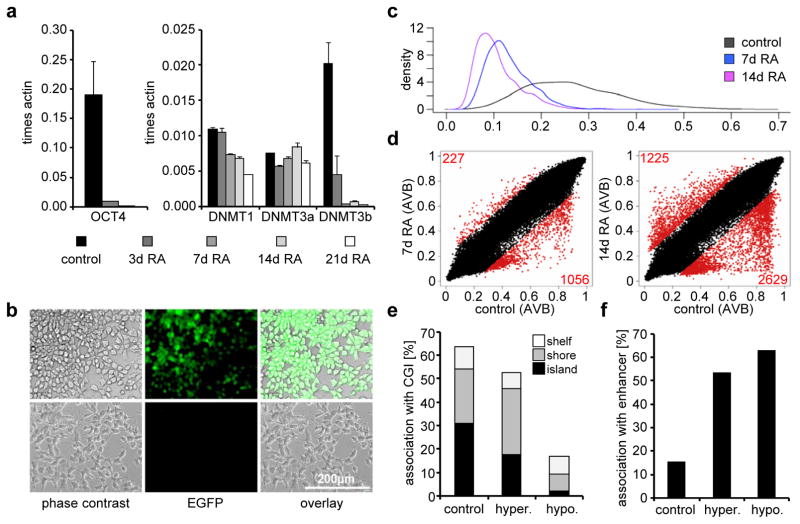

The embryonal carcinoma cell line NTERA2 D1 (NT2) represents a well-established model system to study HOX cluster regulation6. NT2 cells have not only been shown to differentiate along the neuronal lineage upon RA induction, but also show mesodermal and ectodermal lineage potential and are thus considered to be a valuable stem cell model system31,32. They express high levels of the stem cell specific transcription factor OCT4, other stemness factors, PcG proteins and DNA methyltransferases (Fig. 1a; ref. 14). Expression of pluripotency genes and the DNA methyltransferase DNMT3B is rapidly reduced upon RA-dependent differentiation (Fig. 1a, 1b).

Figure 1. Pluripotency features and DNA methylation profiles of NT2 cells upon retinoic acid induction.

(a) Expression of OCT4, DNMT1, DNMT3a and DNMT3b in untreated NT2 cells and cells treated for 3, 7, 14 and 21 days with retinoic acid (RA). qRT-PCR measurements with at least three biological replicates were internally normalised to the corresponding β-actin expression levels. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars. (b) Microscopic images of NT2 cells showing the expression of EGFP under the control of the OCT4-promoter (first row) and the same cells after treatment with retinoic acid for 7 days (second row). The first column shows the light microscopic images (phase contrast), the second column EGFP fluorescence, the third column an overlay. (c) Density plot showing the distribution of the AVB-values (x-axis) of 3091 non-CpG methylation states interrogated by the Infinium450K BeadChip, measured in uninduced NT2 cells (black, mean = 0.27) and cells treated for 7 days (blue, mean = 0.13) and 14 days (purple, mean = 0.11) with RA. (d) Scatter plots showing the comparison of Illumina DNA methylation profiles (including non-CpG sites) of untreated NT2 cells with profiles of cells treated for 7 days (left plot) and 14 days (right plot) with RA. Red dots and numbers indicate differentially methylated sites. (e) Bar diagram showing the association of all sites interrogated by the Infinium450K BeadChip (control), RA-induced hypomethylated sites (hypo.) and hypermethylated sites (hyper.) with CpG islands, shelf and shore regions. (f) Bar diagram showing the correlation of RA-induced differentially methylated sites (hypo- or hypermethylated compared to controls) identified using the Infinium450K BeadChip with annotated enhancer regions.

In order to study detailed DNA methylation patterns before and after RA induction, we analysed genomic DNA of RA-treated and untreated NT2 cells using Infinium450K BeadChips (Illumina). These arrays interrogate more than 450,000 methylation sites in the human genome, including CpG islands (CGIs), CpG sites outside of CGIs and non-CpG methylation sites identified in human embryonic stem cells33. Low levels of strand specific DNA methylation outside the CpG context have been found specifically in mouse and human embryonic stem cells34,35. Interestingly, NT2 cells also showed significant levels of non-CpG methylation that was greatly reduced upon RA-induced differentiation (Fig. 1c), which further illustrates the value of this cell line as a human stem cell model.

DNA methylation analysis in differentiating NT2 cells

A detailed analysis of the Infinium450K data showed significant dynamic changes in site-specific genomic methylation patterns, which increased during RA treatment (Fig. 1d). After 14 days of RA induction, 2629 individual markers were hypomethylated and 1225 markers hypermethylated compared to the untreated control, which corresponds to 1286 differentiation-dependent hypomethylated and 529 hypermethylated genes. Array-predicted methylation changes were experimentally validated by 454 bisulfite sequencing (see below) and thus represent genuine epigenetic changes associated with RA-induced differentiation.

Further data analysis addressed the molecular characteristics of differentially methylated sites. Hypomethylated sites were substantially less frequently associated with CGis (including annotated shelf and shore regions) when compared to hypermethylated sites or to all sites represented on the array (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, differentially methylated sites were more frequently associated with CpG island shores, which is in line with previous reports showing that the majority of DNA methylation variation occurs in shores rather than in CGIs36. Additional characterization showed that differentially methylated sites were significantly associated with enhancer regions (Fig. 1f). Pathway analyses of differentially methylated genes revealed ‘gene expression’ and ‘cellular development’ as the most significantly enriched molecular and cellular functions (Supplementary Figure S1). Furthermore, the most significantly enriched physiological function identified for the hypomethylated gene set was ‘nervous system development and function’ (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting that DNA methylation plays a role in the neuronal differentiation induced by RA treatment of NT2 cells.

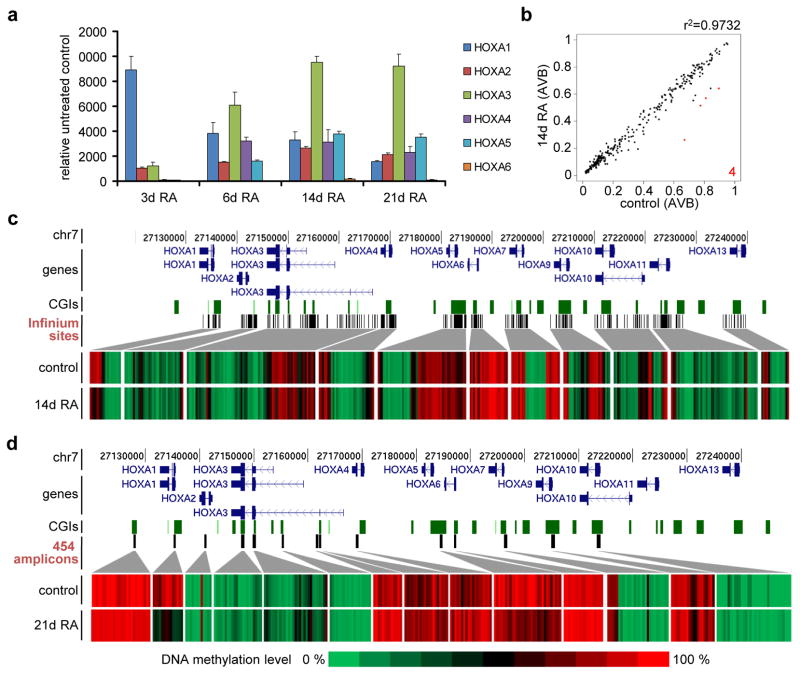

Epigenetic changes in the activated HOXA cluster

One of the best-studied genomic regions in NT2 cells is the anterior half of the HOXA cluster, which is colinearly activated upon RA treatment (Fig. 2a; refs. 8 and 9). HOXA1 was rapidly activated, and peaked after 3 days of RA treatment, whereas HOXA2 and HOXA3 levels were steadily increasing over the course of the experiment. Expression of HOXA4 and HOXA5 started to increase after 3 days of RA exposure, whereas HOXA6 only began to be expressed after 14 days. The posterior part of the cluster, starting with HOXA7, does not respond to RA in NT2 cells8,9.

Figure 2. Epigenetic regulation of the HOXA cluster.

(a) qRT-PCR expression analysis of HOXA genes (1 to 6) after RA treatment for 3, 6, 14 and 21 days. qPCR values were internally normalised to the corresponding lamin-b and β-actin expression levels. Expression values indicate fold induction compared to the non-treated control. All treatments and measurements were repeated three times. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars. (b) Scatter plot showing the comparison of Illumina DNA methylation values of sites located within the HOXA cluster of NT2 cells treated for 14 days with RA with those of untreated cells. Red dots indicate differentially methylated sites. Only four sites were significantly hypomethylated upon RA treatment, corresponding to the HOXA1 gene body. (c) Array-predicted DNA methylation levels in the HOXA cluster in untreated NT2 cells (control) and cells treated for 14 days with retinoic acid (14d RA). HOXA transcription units on chromosome 7 are indicated in dark blue, CpG islands as green squares and interrogated Infinium sites as black bars. Genomic features are viewed as custom tracks in the UCSC genome browser55. (d) DNA methylation levels in the HOXA cluster, as obtained by 454 bisulfite sequencing of selected amplicons (black bars) in untreated NT2 cells (control) and in cells treated for 21 days with retinoic acid (21d RA). HOXA transcription units on chromosome 7 (in dark blue), CGIs (green bars) and 454 amplicons (black bars) are indicated. Genomic features are viewed as custom tracks in the UCSC genome browser55.

HOXA activation is accompanied by rapid changes of histone modification patterns8,9. We followed epigenetic changes in the HOXA1 region by chromatin immunoprecipitation (X-ChIP) using antibodies against modified variants of histone H3. As expected, the HOXA1 promoter was marked by bivalent chromatin (trimethylation of lysine 4 and 27) in the uninduced state (Supplementary Figure S2). Upon RA treatment, these structures were resolved to H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 was successively lost (Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, an exonic HOXA1 region, containing one of the few potential NANOG/OCT4 binding sites in the cluster37, was mainly marked by H3K27me3 in the uninduced state. Upon RA treatment, this pattern rapidly changed to H3K4me3, which reflects the activated transcription of the gene (Supplementary Figure S2).

The HOXA cluster is characterised by several CpG-rich regions that often localise near transcription units, suggesting the involvement of DNA methylation in their regulation9. We therefore extracted the 383 CpG sites associated with the cluster from the Infinium450K data and analysed their methylation status (Fig. 2b and 2c). Many of these sites were methylated in untreated NT2 cells, especially downstream of HOXA1, in the gene body of HOXA3, between HOXA5 and HOXA7 and also in the HOXA9 gene body (Fig. 2c). This pattern did not change significantly upon RA treatment for 14 days, which is in contrast to the strong activation of the anterior part of the cluster observed during this time period (Fig. 2a and 2c). We validated and expanded this analysis using deep 454 bisulfite sequencing of selected CpG-rich regions of the cluster after 3 weeks of RA treatment (Fig. 2d). We obtained very similar results, with highly methylated regions downstream of HOXA1, in the HOXA3 gene body, in several regions between HOXA4 and HOXA7 and in the HOXA9 locus. Similar patterns were also described in human ESCs using high throughput bisulfite sequencing13. Again, most of these regions did not change their methylation state upon differentiation, even after 3 weeks (Fig. 2d). A notable exception was the first exon of HOXA1 that showed significant demethylation after 14 days of RA treatment (Fig. 2c), which was further increased after 21 days (Fig. 2d). We have previously shown that a knock down of the maintenance DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 leads to a significant loss of DNA methylation in CpG islands of the HOXA cluster14. We thus measured the expression levels of the first three HOXA genes after three days of DNMT1 depletion and found a significant but weak derepression of these genes (Supplementary Figure S3). Nevertheless, this effect was minimal compared to RA induction, indicating that DNA methylation might have an accessory role in HOXA repression.

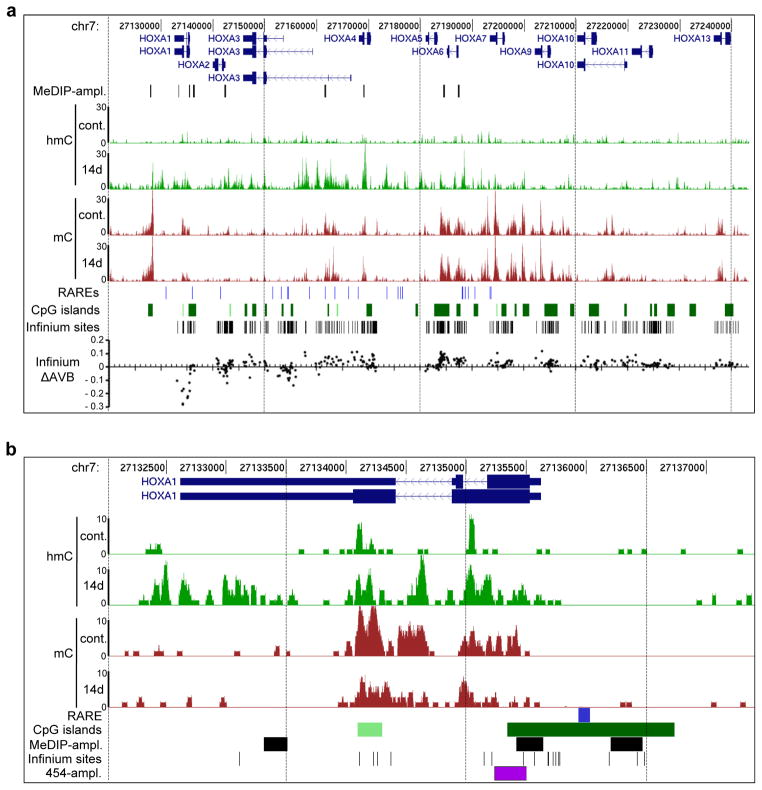

Increased 5-hydroxymethylation in the activated HOXA cluster

The persistence of DNA methylation patterns in RA-induced cells appeared to contradict the colinear transcriptional activation of the HOXA cluster, which is accompanied by clear epigenetic changes on the level of histone modifications (Supplementary Figure S2; refs. 8 and 9). However, our methods for DNA methylation analysis were based on bisulfite conversion, which does not distinguish between 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine38. If HOXA activation was accompanied by oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC, this conversion could not have been detected by our methods. We therefore used methylated DNA immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies21,22 against 5mC (MeDIP) and 5hmC (hMeDIP) and massive parallel sequencing to examine changes in 5mC and 5hmC distribution during RA-induced differentiation of NT2 cells. We obtained 10 to 50 million reads for each sample (Supplementary Table S1), which were mapped to the most recent human genome assembly (GRCh37/hg19). All reads from the cluster were extracted and read coverage over genomic HOXA regions were calculated. As shown in Figure 3a we found high levels of DNA methylation at specific regions in untreated NT2 cells, often related to CpG islands, which closely correspond to our Infinium450K and 454 bisulfite sequencing results. Interestingly, 5mC was basically absent at potential retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) of the anterior cluster9, which might indicate their accessibility (Fig. 3a). 5-hydroxymethylation was found to be evenly distributed at low levels throughout the cluster in untreated NT2 cells. Upon RA treatment, a strong overall increase in 5hmC levels was observed in the activated part of the cluster (HOXA1-HOXA6). This is shown in more detail for the HOXA1 region in Figure 3b. Of note, we also observed that increasing levels of 5hmC were paralleled by a reduction of 5mC, in particular in the HOXA1 region (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Distribution of 5mC and 5hmC within the HOXA cluster.

(a) hMeDIP-seq (hmC) and MeDIP-seq (mC) profiles of the HOXA cluster in untreated NT2 cells (cont.) and cells treated for 14 days with retinoic acid (14d). Enrichments are indicated as increase in the sequence coverage. HOXA transcription units on chromosome 7 are indicated on top in dark blue, below (h)MeDIP-amplicons are indicated as black lines. Potential retinoic acid response elements (RAREs)9 are shown as light blue lines below the profiles, CpG islands as green squares and sites interrogated by the Infinium450K BeadChip as black bars. At the bottom the difference of methylation values of the Infinium analysis (ΔAVB) between untreated and NT2 cells treated for 14 days with RA for each Infinium site is indicated. Genomic features are viewed as custom tracks in the UCSC genome browser55 (b) Detailed hMeDIP-seq (hmC) and MeDIP-seq (mC) profiles at the HOXA1 locus in untreated NT2 cells (cont.) and cells treated for 14 days with retinoic acid (14d). The HOXA1 RARE (blue bar), CpG islands (green squares), (h)MeDIP-amplicons (black squares), Infinium sites (black lines) and the 454 bisulfite sequencing amplicon (purple square) are indicated below the profiles. Genomic features are viewed as custom tracks in the UCSC genome browser55.

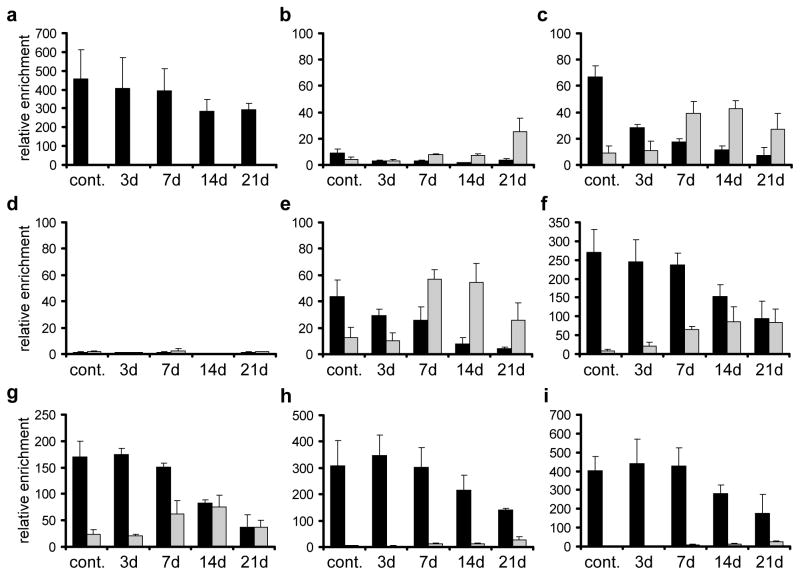

In order to validate the sequencing data and to extend the time frame of the analysis, we repeated the immunoprecipitation analysis with genomic DNA from untreated NT2 cells and cells treated for 3, 7, 14 and 21 days with RA and analysed the immunopurified DNA by gene specific real-time-PCR at selected genomic regions (see Fig. 3 for amplicon positions). The human genes UEB2B and HIST1H3B served as umethylated control regions (Supplementary Figure S4). As shown in Figure 4, the (h)MeDIP-seq data was essentially confirmed. We found high levels of 5mC at the CpG island downstream of HOXA1, at exonic regions of HOXA1, HOXA3, HOXA4, an intergenic region between HOXA5 and 6 and at the HOXA6 promoter. Lower, but significant levels of DNA methylation were also present at the promoters of HOXA1 and HOXA2. Except for the CpG island downstream of HOXA1, we also detected low levels of DNA hydroxymethylation in all these regions (Fig. 4). Hydroxymethylation significantly increased during RA treatment, which was accompanied by decreasing 5mC levels (Fig. 4). Taken together, our results show that during RA-induced differentiation, the anterior part of the HOXA cluster loses 5-methylcytosine marks and gains significant levels of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. These changes follow the physiological colinear activation pattern of the cluster: changes were greater for anterior genes that respond faster and stronger to RA (HOXA1, HOXA2) than for posterior genes that respond slower (HOXA5, HOXA6). In addition, after 21 days of RA treatment, we also observed a low degree of total (5hmC plus 5mC) demethylation, especially for the promoters of HOXA1 and HOXA2 and the second exon of HOXA4. This finding probably reflects further oxidation of hydroxymethylated cytosines after prolonged RA treatment.

Figure 4. Levels of 5mC and 5hmC at selected regions of the HOXA cluster.

Genomic DNA from untreated NT2 cells and cells treated for 3, 7, 14 and 21 days with retinoic acid was analysed by (h)MeDIP using antibodies against 5mC and 5hmC. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by gene specific qPCR. The following regions were analysed: (a) HOXA1 downstream CpG island, (b) HOXA1 second exon (covering a potential NANOG/OCT4 binding site37), (c) HOXA1 promoter/1st exon, (d) HOXA1 upstream RARE (e) HOXA2 promoter/1st exon (f) HOXA3 2nd CpG island (g) HOXA4 2nd exon (h) HOXA5–6 intergenic CpG island (i) HOXA6 promoter/1st exon. Enrichments were calculated relative to the unmethylated UEB2 control. 5mC values are shown as black bars, 5hmC values as grey bars. Diagrams show the results of at least three independent experiments. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

TET2 mediates hydroxymethylation in the HOXA cluster

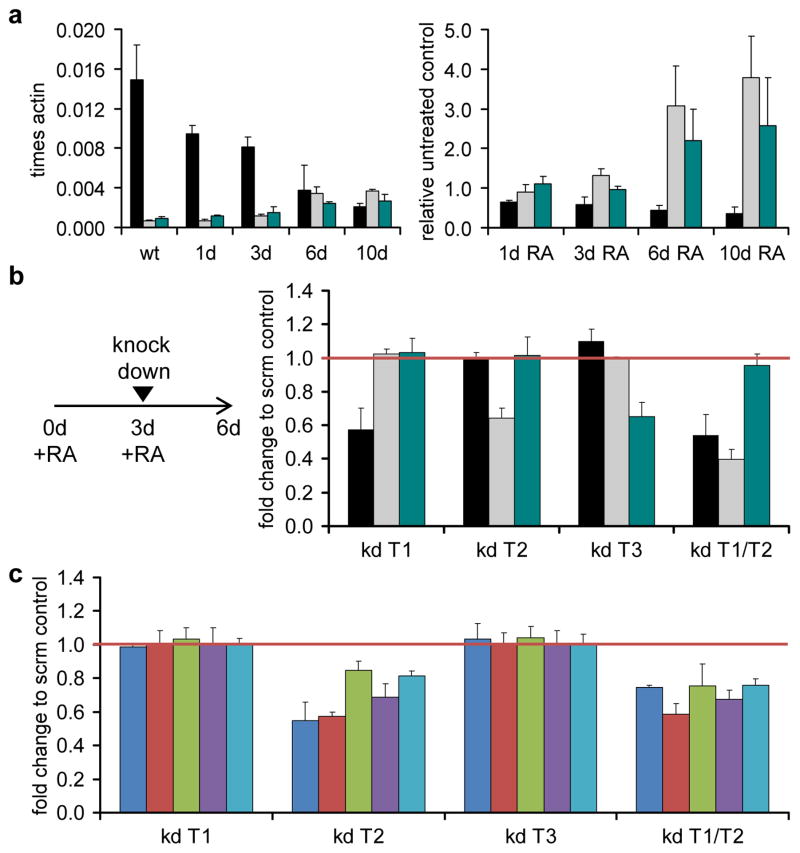

To address mechanistic aspects behind the observed methylation changes, we analysed the expression of TET1–3 in differentiating NT2 cells. As shown in Figure 5a, TET1 was highly expressed in uninduced NT2 cells, consistent with the pluripotent potential of the cell line. TET2 and TET3 were expressed at much lower levels. Upon RA induction, TET1 was downregulated, whereas TET2 and TET3 were significantly upregulated (Fig. 5a). In order to analyze the role of TET proteins in maintaining the active state of the HOXA cluster, NT2 cells were treated with RA for 3 days, followed by siRNA-mediated knock down of TET enzymes. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of TET1–3 mRNA levels showed that the depletion was effective (Fig. 5b) and comparable to other publications21. The expression of the most proximal HOXA genes, especially of HOXA1 and HOXA2, was significantly lower for the TET2 knock down when compared to the control (Fig. 5c). Also, HOXA3, HOXA4 and HOXA5 were less expressed upon knock down of TET2. A combination of TET1 and TET2 knock down, that was shown to have the strongest effect on the derepression of pluripotency-related genes in mouse ESCs21, gave similar results (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5. TET2 is necessary for the maintenance of HOXA activity.

(a) qRT-PCR expression analysis of the three TET genes after RA treatment for 1, 3, 6 and 10 days. The left panel shows the expression levels of TET1 (black bars), TET2 (grey bars) and TET3 (green bars) as a fraction of the β-actin expression levels. The right panel shows the expression changes of the three TET mRNAs during RA treatment relative to the untreated control, internally normalised to the corresponding expression levels of lamin-b and β-actin. (b) qRT-PCR expression analysis of TET1 (black bars), TET2 (grey bars) and TET3 (green bars) after RA treatment and successive depletion with specific siRNA pools in single knock downs (kd T1, kd T2, kd T3) or in a TET1/TET2 double knock down (kd T1/T2). NT2 cells were treated for 3 days with retinoic acid, replated and transfected with siRNAs. After 3 more days cells were harvested and total RNA for qRT-PCR analysis was isolated. Y-axis values indicate fold change compared to the scrambled knock down control (non-targeting pool). qPCR values were internally normalised to the corresponding lamin-b and β-actin expression levels. (c) qRT-PCR expression analysis of HOXA1 (blue bars), HOXA2 (red bars), HOXA3 (green bars) HOXA4 (purple bars), HOXA5 (light blue bars) after RA treatment and successive TET-depletion with specific siRNAs in single knock downs (kd T1, kd T2, kd T3) or in TET1/TET2 double combination (kd T1/T2). Y-axis values indicate fold change compared to the scrambled knock down control (non-targeting pool). qPCR values were internally normalised to the corresponding lamin-b and β-actin expression levels.

Treatments and measurements in (a)–(c) were repeated at least three times. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

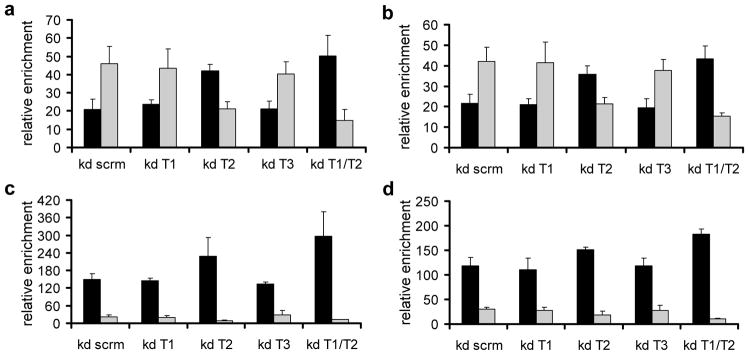

Next we investigated the functional role of TET proteins for the methylation state of the cluster. Again NT2 cells were treated for 3 days with RA, followed by knock down of TET enzymes. Genomic DNA was then prepared and analysed by (h)MeDIP, with a focus on the four HOXA-regions that showed significant methylation changes upon RA treatment: the promoters of HOXA1 and HOXA2, a CpG-rich region of HOXA3 and the second exon of HOXA4. As shown in Figure 6, the patterns observed for the control are in excellent agreement with the (h)MeDIP-seq data shown in Figure 4. Knock down of TET1 and TET3 did not change these patterns, whereas TET2 depletion led to reduced levels of 5hmC in all four regions, while 5mC levels became partially restored. An even stronger effect was observed when TET1 and TET2 were simultaneously depleted, leading to 5mC levels that approached untreated NT2 cells (Fig. 6). Thus, TET2 depletion reverses the epigenetic DNA methylation changes induced by retinoic acid, which results in defects in the maintenance of the active state of the HOXA cluster.

Figure 6. TET2 is mainly responsible for the 5mC-5hmC conversion in the HOXA cluster during retinoic acid induction.

The diagrams show the distribution of 5mC and 5hmC at four regions of the HOXA cluster in NT2 cells transfected with control siRNAs (non-targeting pool - kd scrm), siRNA pools against TET1 (kd T1), TET2 (kd T2), TET3 (kd T3) and TET1/TET2 (kd T1/T2). NT2 cells were treated for 3 days with retinoic acid, replated and transfected with siRNAs. After 3 additional days, cells were harvested and genomic DNA for (h)MeDIP analysis with antibodies specific for 5mC and 5hmC was isolated. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by gene specific qPCR. The following regions were analysed: (a) HOXA1 promoter/1st exon, (b) HOXA2 promoter/1st exon, (c) HOXA3 2nd CpG island and (d) HOXA4 2nd exon. Enrichments were calculated relative to the unmethylated UEB2 control. 5mC values are shown as black bars, 5hmC values as grey bars. Diagrams show the results of three independent experiments. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

Knock out of Tet2 leads to reduced Hoxa expression

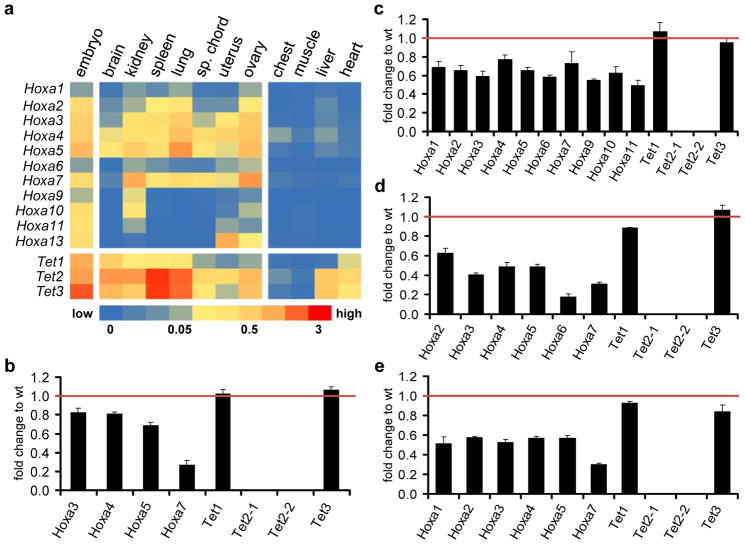

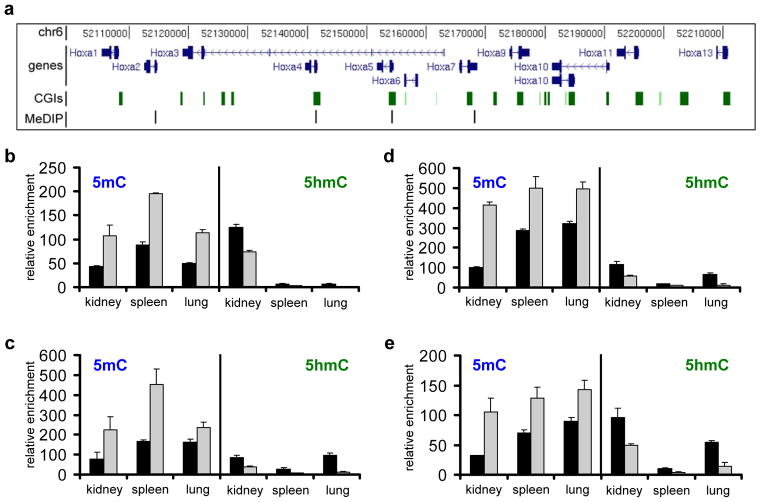

Finally, in order to further confirm a role for Tet2 in Hoxa transcriptional maintenance, we also measured Hoxa expression levels in various mouse tissues and compared them to Tet2 knock out tissues39. Total RNA of samples of an one year old Tet2−/− mouse and a wild type animal with the same genetic background was prepared and Hoxa and Tet expression patterns were analysed (Fig. 7). We restricted further analysis to seven tissues that were previously reported to contain significant 5hmC levels26–28 and showed clear Tet2 and Hoxa expression patterns in adult wild type mice (Fig. 7a). With very few exceptions, active Hoxa genes showed significantly reduced expression levels in the corresponding Tet2−/ − tissues (Fig. 7b-e; Supplementary Figure S5). In contrast, Tet1 and Tet3 patterns remained mostly unchanged. Finally, to analyse the effect of the Tet2 deletion on the methylation state of the murine Hoxa cluster, we performed (h)MeDIP using wild type and Tet2−/− genomic DNA of three tissues that showed significant Hoxa expression patterns in wild type mice (kidney, spleen, lung). We restricted our analysis to four genomic fragments, corresponding to regions that contain the promoter or reside in the first exon of Hoxa2, Hoxa4, Hoxa5 and Hoxa7, respectively (Fig. 8a). The results showed that loss of Tet2 induced a significant increase of 5mC in these regions, paralleled by a reduction of 5hmC (Fig. 8b–e). These changes are in excellent agreement with the reduced expression levels observed for these genes in these tissues (Fig. 7c–e). These data confirm a general role for Tet2 in controlling 5hmC levels and thereby the maintenance of active expression patterns in the mammalian Hoxa cluster.

Figure 7. Expression of Hoxa genes is reduced in mouse Tet2−/− tissues.

(a) qRT-PCR expression analysis of the eleven Hoxa and three Tet genes in murine wild type tissues (indicated above the columns). The heat map shows average Hoxa and Tet expression as percentage of the internal GPDH levels. Expression patterns of both groups of genes in 13.5 days wild type embryos is shown as a positive control (most left column). Four examples of tissues with very low or absent expression are also shown (chest, muscle, liver, heart). (b)–(d) qRT-PCR expression analysis of Hoxa genes that showed significant levels in (a) and the three Tet genes in selected Tet2−/− tissues. Diagrams show the expression as fold change relative to the wild type (=1). For Tet2, two different primer pairs were used39. (b) brain, (c) kidney, (d) spleen, (e) lung. Standard deviations of three replicates are indicated by error bars.

Figure 8. Levels of 5mC and 5hmC at selected regions of the murine Hoxa cluster in control and Tet2−/− tissues.

Genomic DNA was isolated from three tissues showing significant Hoxa expression in the wild type situation (kidney, spleen and lung) and used for (h)MeDIP analysis with antibodies specific for 5mC and 5hmC. (a) Diagram showing the mouse Hoxa transcription units on chromosome 6 (in dark blue), the CpG islands within the cluster (green squares) and the four (h)MeDIP-amplicons (indicated as black lines) used for the analysis. Genomic features are viewed as custom tracks in the UCSC genome browser55. The following regions were analysed: (b) mHoxa2 promoter, (c) mHoxa4 1st exon, (d) mHoxa5 1st exon and (e) mHoxa7 promoter. The diagrams show the distribution of 5mC (left in each panel) and 5hmC (right in each panel) at four regions of the mouse Hoxa cluster in three tissues (kidney, spleen, lung) in wt (black bars) and Tet2−/− (grey bars). Enrichments were calculated relative to the unmethylated mGapdh and mbeta-actin controls. Standard deviations of three replicates are indicated by error bars.

Discussion

In this study we show that the repressed human HOXA cluster is characterised by a specific pattern of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine marks. Both marks appeared to decorate larger regions, similar to the domains described for bivalent histone modifications in repressed HOX clusters5. Upon differentiation, the anterior half of the cluster became active and was marked by high levels of 5hmC. In parallel, 5mC levels were reduced, especially in the HOXA1 and HOXA2 regions. A more detailed analysis of selected HOXA-loci revealed that the increase of 5hmC followed the colinear gene activation pattern of the cluster, i.e. expression changes and higher 5hmC levels were first observed at proximal HOXA genes, whereas more distal genes showed delayed activation and responded substantially later. These findings further underscore the association of the 5hmC mark with activated HOXA transcription.

We identified TET2 as an important factor for the RA-induced 5mC-5hmC conversion. TET2 was significantly upregulated in RA-treated NT2 cells. Knock down of TET2 after 3 days of RA treatment led to a significant decrease in expression levels of the anterior HOXA genes, indicating that the maintenance of their transcription is disturbed. This appeared to be directly caused by reduced hydroxymethylation, as TET2 knock down also led to reduced 5hmC levels at selected HOXA regions and partially restored 5mC levels. Our data suggest that the 5mC-5hmC conversion by TET2 at neuronal selector genes (like the anterior HOXA cluster), is important for ongoing differentiation processes that depend on their expression. A comparable role for Tet2 has been suggested for the haematopoietic lineage. Tet2 is highly expressed in erythroid precursors and granulocytes29 and loss of the protein has been shown to lead to various haematopoietic differentiation defects39,40–42.

Furthermore, our results obtained with tissues from Tet2−/− mice39 suggest that Hoxa expression patterns in terminally differentiated tissues are also negatively affected by the deletion of Tet2. Interestingly, the tissues that showed the strongest effect were kidney, lung and the spleen, which also showed the highest Tet2 expression levels. These tissues showed a clear reduction of 5hmC in Hoxa target regions in the Tet2−/− mouse and significantly increased 5mC levels, which corresponded to the reduced Hoxa transcription. Nevertheless, Hoxa genes remained active at lower levels, which might explain the lack of strong developmental phenotypes in Tet2−/− mice. As shown in our knock down experiments in NT2 cells, a partial redundancy between TET1 and TET2 cannot be excluded, and it will be interesting to analyze the developmental phenotypes of Tet1−/−/Tet2−/− double mutant mice.

Interestingly, the specific patterns of HOXA methylation we have identified in untreated NT2 cells did not prevent initial transcriptional activation. For the first three HOXA genes high transcriptional activity can be observed already after a few hours of RA treatment9, when methylation patterns have not yet changed. HOXA activation during development strongly depends on the interaction of the ligand-bound retinoic acid receptors with specific RAREs, the subsequent changes in histone modifications and the recruitment of activating protein complexes10,43. In agreement with this notion, we found that reduction of DNA methylation by depletion of DNMT1 only led to a minimal HOXA activation in untreated NT2 cells. It is known that the repressed cluster has a particular higher order structure and that transcriptional activation is accompanied by structural changes within the cluster10,44,45. Changes in DNA methylation patterns during differentiation might thus influence the three-dimensional architecture of the cluster and thus affect the maintenance and fine-tuning of gene expression states46. Our data indicate that once the cluster has been activated, 5mC-5hmC conversion is necessary for the maintenance of RA-induced transcription patterns and active higher order structures.

While most regions with RA-induced 5hmC show already significant cytosine methylation in untreated NT2 cells, we also observed elevated 5hmC levels in some regions (mostly outside of CpG islands) that appeared not to be marked by 5mC. It should be noted that the 5mC antibody used in our experiments is significantly less efficient in dot blots and in immunoprecipitations, when compared to the 5hmC antibody21–23. In addition, its binding depends much more on the CpG density in the DNA fragments23. Thus, in regions with low CpG density, 5mC will not be recognised very well (or not at all), whereas detection of 5hmC will be more efficient. Nevertheless, our Infinium450K data show that total DNA methylation levels in the HOXA cluster did not change significantly upon RA treatment for 14 days for most of the interrogated sites (Fig. 3a, bottom panel). This indicates that 5hmC signals detected after RA treatment largely depend on pre-existing 5mC.

Although we could observe some degree of total DNA demethylation after prolonged RA treatment in NT2 cells, the overall rate appeared rather low. While we did not analyse further processing and excision of the 5hmC mark in later stages, the substantial levels of 5hmC during the first three weeks of differentiation and the colinear pattern of 5mC-5hmC conversion indicate that already the presence of 5hmC allows the maintenance of active higher order structures. Interestingly, it was shown that oxidation of cytosines in CpG-rich regions reduces significantly the binding of methyl-CpG binding proteins and DNA methyl transferases47,48. Thus 5mC-5hmC conversion might passively inhibit the maintenance of repressive structures by disturbing DNA-protein interactions. In addition, chromatin remodeling complexes can directly interact with regions marked with 5hmC and influence 5hmC patterns49, which suggests that 5hmC itself can be read as an epigenetic mark. The three mouse tissues we used for (h)MeDIP analysis, despite high expression of Tet2, harbour very different total 5hmC levels26–28,39,40. Our results show that knock out of Tet2 results in a general strong increase of 5mC in these tissues. This suggests tissue specific differences regarding the further processing of 5hmC, which is in line with recent findings that tissue type is the major determinant of 5hmC content50.

In conclusion, we envisage the repressed HOXA cluster to be marked by specific methylation patterns and to be part of a silent looped structure in pluripotent cells. After RA induction activated genes would move sequentially or by specific looping interactions to an open compartment (Supplementary Figure S6). This is accompanied by progressive 5-hydroxymethylation, which prevents DNA re-methylation and gene re-silencing.

Material and Methods

Cell culture

The human cell line NT2 D1 was a kind gift from Peter W. Andrews. Cell line authentication was provided by LGC Standards (Teddington, report tracking no. 71008933). NT2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (D-MEM, with l-glutamine, 4500 mg/l d-glucose, without sodium pyruvat; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 200 U/ml penicillin and 200 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Gibco) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. NT2 cells were induced to differentiate with 10 μM all-trans retinoic acid (Sigma). Medium containing RA was changed every 2 days. Cells were harvested by trypsin treatment and stored at −80 °C.

Protein depletion via siRNAs

For depletion of TET1, TET2, TET3 and DNMT1 ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNAs (Dharmacon) were used. Untreated NT2 cells or cells treated for 3 days with RA were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 2×105 in 2 ml of medium. siRNAs were transfected with the DharmaFECT1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon). The final siRNA concentration was 50 nM. Cells were harvested after 72 hours and pellets were stored at −80°C. Scrambled siRNAs for negative control experiments (non-targeting pool) were also obtained from Dharmacon.

RT PCR and real time analysis

Total RNA from RA-induced and untreated NT2 cells was prepared using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Real-time RT-PCR was performed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). One μg of total RNA was processed in 20 μl reactions. One μl of cDNA was used for a 10 μl PCR reaction using the Absolute QPCR SYBR Green Mix (Thermo Scientific) and a Roche LightCycler 480. PCR conditions: 1 cycle: 95°C×15 minutes; 50 cycles: 95°C×15 seconds, 60°C×40 seconds, read; melting curve 65°C–95°C, read every 1°C. Cycle threshold numbers for each amplification were measured with the LightCycler 480 software and relative expression values were calculated and normalised using β-actin and lamin-b as internal standards. qRT-PCR measurements were repeated at least three times on biological replicates. For primer sequences see Supplementary Table S2.

Array based DNA methylation profiling and data analysis

Genomic DNA from RA-induced and untreated NT2 cells was prepared using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Invitrogen). Array-based gene-specific DNA methylation analysis was performed using Infinium HumanMethylation450 bead chip technology (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Genomic DNA (500 ng) from each sample was bisulfite converted using the EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research Corporation). Bisulfite treated genomic DNA was whole-genome amplified and hybridised to HumanMethylation450 BeadChips. The methylation status of a specific cytosine was indicated by average beta (AVB) values where 1 corresponds to full methylation and 0 to no methylation. Raw array data were quantile normalised and p-values for comparisons between different datasets were statistically adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction as described previously51. Individual loci were scored as differentially methylated if the AVB difference was greater than or equal to 0.2. Functional categories of differentially methylated genes were identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (www.ingenuity.com). The Infinium methylation data is available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under accession code GSE33130.

454 DNA bisulfite sequencing

Deep DNA bisulfite sequencing was performed as described previously51. For 454 sequencing, bisulfite-treated genomic DNA was amplified using sequence-specific primers containing cell type-specific barcodes and 454 linker sequences (see Supplementary Table S3).

ChIP assay

Crosslinked chromatin from untreated or RA-treated NT2 cells was prepared and immunoprecipitated as described previously14. ChIP-grade antibodies specific for H3K27me3 (07-449) and H3K4me3 (07-473) were purchased from Upstate. Immunoprecipitates were finally dissolved in 30 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCL pH 8, 1 mM EDTA). One μl was analysed by real time PCR using HOXA1-specific primer pairs (see Supplementary Table S4) in 10 μl PCR reactions, using the Absolute QPCR SYBR Green Mix (Thermo Scientific) and a Roche LightCycler 480. PCR conditions: 1 cycle: 95°C×15 minutes; 50 cycles: 95°C×15 seconds/60°C×40 seconds, read; melting curve 65°C–95°C, read every 1°C. Cycle threshold numbers for each amplification were measured with the LightCycler 480 software and enrichments were calculated as percentage of the input.

MeDIP and hMeDIP

Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation was performed as described52. Genomic DNA from NT2 cells or mouse tissues was randomly sheared using a Bioruptor (Diagenode). 5 μg of sonicated DNA was used for immunoprecipitations with 2 μg of antibodies specific for 5-methylcytosine (monoclonal; Active Motif, 39649) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (polyclonal, Active Motif, 39791). Co-precipitated DNA was finally resolved in 60 μl TE buffer. Two μl of the IP or 20 ng of input DNA were analysed by real time PCR using specific primer pairs (see Supplementary Table S4) in 10 μl PCR reactions, using the Absolute QPCR SYBR Green Mix (Thermo Scientific) and a Roche LightCycler 480. PCR conditions: 1 cycle: 95°C×15 minutes; 50 cycles: 95°C×15 seconds/60°C×40 seconds, read; melting curve 65°C–95°C, read every 1°C. Cycle threshold numbers for each amplification were measured with the LightCycler 480 software and enrichments were calculated as percentage of the input. As negative controls for unmethylated regions served UEB2B and HIST1H3B for human samples or the mGapdh and mBeta-actin promoters for mouse52 (Supplementary Figure S4). Final enrichments were calculated relative to these unmethylated controls as described52. For primer sequences see Supplementary Table S4.

(h)MeDIPs-Seq

Genomic DNA was purified from untreated and RA-treated NT2 cells as described above Fifty μg of genomic DNA for each sample was sonicated to 300bp fragments using a Covaris S220 (Covaris). Sheared DNA was ethanol precipitated, washed with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in TE buffer (pH8.0). Illumina adapters were ligated as described25 using the End-It DNA End-repair kit (Epicentre). DNA was purified with the QiaQuick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and diluted to 122.5μl with ddH2O. After the addition of 15μl NEB buffer 2, 3.5μl of 10mM ATP and 9μl of 5U/μl Klenow exo− (NEB), reactions were incubated at 37°C for 50min. DNA was subsequently purified with the QiaQuick PCR purification kit, diluted to 24μl with ddH2O, and mixed with 50μl of 2x NEB quick ligation buffer, 20 μl of barcoded Illumina adapter and 6μl of quick T4 DNA ligase (NEB). After 20 minutes incubation at room temperature, DNA was purified again with QiaQuick PCR purification kit. Ligation efficiency was analyzed by PCR on 10ng of final ligated DNA with Illumina sequencing primers. Finally, five μg of adapter ligated DNA was used for the immunoprecipitation, as described above. Immunoprecipitated DNA was resolved in 20μl of water and all (h)MeDIP samples were pooled to create the MeDIP and hMeDIP libraries, respectively. Both libraries were purified on e-Gel (Invitrogen) and the 300bp bands (containing roughly 200bp fragments of adapter-ligated immunopurified DNA) were extracted. Libraries were amplified using Illumina-Enrichment Primers for 12 cycles and purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter). DNA concentrations were measured using a Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Assay (Agilent Technologies) and 7 pmol were used for cluster PCR and substantial 50bp single-end sequencing on a HiSeq2000 (Illumina).

Mapping of sequencing data

All processing steps of the sequencing data were carried out using the short read analysis pipeline shore53. Reads were trimmed by removing stretches of bases having a quality score <30 at the ends of the reads. The trimmed reads were mapped to the most recent human genome assembly hg19 using the mapping program bowtie54. After the mapping duplicate reads were removed and the position-wise coverage of the HOXA cluster by sequencing reads was integrated as custom tracks in the UCSC genome browser55 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). The sequencing data is available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession code GSE33130.

Gene expression analysis in Tet2 knockout mice

Tet2 knock out mice have been described previously39. One female Tet2−/− mouse and one wild type female of the same genetic background were sacrificed and 18 tissue samples (total brain, heart, kidney, spleen, liver, pad, chest bone, nose, tongue, tail, skin, eye, small intestine, skeletal muscle, spinal chord, uterus, ovary and lung) were taken and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage at −80 °C. Total RNA was prepared using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and a TissueRuptor (Qiagen). Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described above. Relative quantifications of expression status of the genes under observation comparing treated to non-treated cells were calculated and normalised using mouse β-actin and GPDH as internal standards. qRT-PCR measurements were repeated at least three times on technical replicates. For mouse-specific primer sequences see Supplementary Table S2. All mouse studies were approved by the MSSM Animal Care and Use Committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter W. Andrews (University of Sheffield) for the original NT2 cells, Kristian Helin (University of Copenhagen) for human HOXA-specific RT-primer sequences, Janetta Bijl (Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Montreal) for murine HOXA-specific RT-primer sequences and Rudolf Jaenisch (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge) for advice on Tet2 mutant mice. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Priority Programmes 1356 and 1463) to AB and FL. We are particularly thankful to André Leischwitz and the DKFZ Genomics and Proteomics core facility for high throughput sequencing and overall support.

Footnotes

Author contribution

AB and FL conceived the study. MB, FL and AB designed the experiments and interpreted results. FCY and MX provided mouse tissues. MB, FT, TM and AB performed the experiments. MB and GR performed the bioinformatic analyses. MB, FL and AB wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Duboule D, Morata G. Colinearity and functional hierarchy among genes of the homeotic complexes. Trends Genet. 1994;10:358–364. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kmita M, Duboule D. Organizing axes in time and space; 25 years of colinear tinkering. Science. 2003;301:331–333. doi: 10.1126/science.1085753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soshnikova N, Duboule D. Epigenetic regulation of Hox gene activation: the waltz of methyls. Bioessays. 2008;30:199–202. doi: 10.1002/bies.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein BE, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boncinelli E, Simeone A, Acampora D, Mavilio F. HOX gene activation by retinoic acid. Trends Genet. 1991;7:329–334. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90423-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langston AW, Gudas LJ. Retinoic acid and homeobox gene regulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:550–555. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90071-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Hansen KH, Helin K. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1123–1136. doi: 10.1101/gad.381706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sessa L, et al. Noncoding RNA synthesis and loss of Polycomb group repression accompanies the colinear activation of the human HOXA cluster. RNA. 2007;13:223–239. doi: 10.1261/rna.266707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashyap V, et al. Epigenomic reorganization of the clustered Hox genes in embryonic stem cells induced by retinoic acid. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3250–3260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.157545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novak P, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the HOXA gene cluster in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10664–10670. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauch T, et al. Homeobox gene methylation in lung cancer studied by genome-wide analysis with a microarray-based methylated CpG island recovery assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5527–5532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701059104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurent L, et al. Dynamic changes in the human methylome during differentiation. Genome Res. 2010;20:320–331. doi: 10.1101/gr.101907.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musch T, Oz Y, Lyko F, Breiling A. Nucleoside drugs induce cellular differentiation by caspase-dependent degradation of stem cell factors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouse SD, et al. Promoter CpG methylation contributes to ES cell gene regulation in parallel with Oct4/Nanog, PcG complex, and histone H3 K4/K27 trimethylation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu SC, Zhang Y. Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:607–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito S, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He YF, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito S, et al. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh KP, et al. Tet1 and Tet2 regulate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine production and cell lineage specification in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ficz G, et al. Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nature. 2011;473:398–402. doi: 10.1038/nature10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine distribution reveals its dual function in transcriptional regulation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2011;25:679–684. doi: 10.1101/gad.2036011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastor WA, et al. Genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2011;473:394–397. doi: 10.1038/nature10102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams K, et al. TET1 and hydroxymethylcytosine in transcription and DNA methylation fidelity. Nature. 2011;473:343–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Y, et al. Genome-wide regulation of 5hmC, 5mC, and gene expression by Tet1 hydroxylase in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell. 2011;42:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Globisch D, et al. Tissue distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and search for active demethylation intermediates. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haffner MC, et al. Global 5-hydroxymethylcytosine content is significantly reduced in tissue stem/progenitor cell compartments and in human cancers. Oncotarget. 2011;2:627–637. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langemeijer SM, et al. Acquired mutations in TET2 are common in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2009;41:838–842. doi: 10.1038/ng.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tefferi A, et al. Detection of mutant TET2 in myeloid malignancies other than myeloproliferative neoplasms: CMML, MDS, MDS/MPN and AML. Leukemia. 2009;23:1343–1345. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews PW. From teratocarcinomas to embryonic stem cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:405–417. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pal R, Ravindran G. Assessment of pluripotency and multilineage differentiation potential of NTERA-2 cells as a model for studying human embryonic stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2006;39:585–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandoval J, et al. Validation of a DNA methylation microarray for 450,000 CpG sites in the human genome. Epigenetics. 2011;6:692–702. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.6.16196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lister R, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meissner A, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irizarry RA, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyer LA, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y, et al. The behaviour of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in bisulfite sequencing. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, et al. Deletion of Tet2 in mice leads to dysregulated hematopoietic stem cells and subsequent development of myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2011;118:4509–4518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ko M, et al. Ten-Eleven-Translocation 2 (TET2) negatively regulates homeostasis and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14566–14571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112317108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pronier E, et al. Inhibition of TET2-mediated conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine disturbs erythroid and granulomonocytic differentiation of human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2011;118:2551–2555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quivoron C, et al. TET2 inactivation results in pleiotropic hematopoietic abnormalities in mouse and is a recurrent event during human lymphomagenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gudas LJ, Wagner JA. Retinoids regulate stem cell differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:322–330. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferraiuolo MA, et al. The three-dimensional architecture of Hox cluster silencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7472–7484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim YJ, Cecchini KR, Kim TH. Conserved, developmentally regulated mechanism couples chromosomal looping and heterochromatin barrier activity at the homeobox gene A locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7391–7396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018279108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noordermeer D, et al. The dynamic architecture of Hox gene clusters. Science. 2011;334:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1207194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valinluck V, Sowers LC. Endogenous cytosine damage products alter the site selectivity of human DNA maintenance methyltransferase DNMT1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:946–950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valinluck V, et al. Oxidative damage to methyl-CpG sequences inhibits the binding of the methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4100–4108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yildirim O, et al. Mbd3/NURD Complex Regulates Expression of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine Marked Genes in Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. 2011;147:1498–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nestor CE, et al. Tissue type is a major modifier of the 5-hydroxymethylcytosine content of human genes. Genome Res. 2012;22:467–477. doi: 10.1101/gr.126417.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gronniger E, et al. Aging and chronic sun exposure cause distinct epigenetic changes in human skin. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohn F, Weber M, Schübeler D, Roloff TC. Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) Methods Mol Biol. 2009;507:55–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-522-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ossowski S, et al. Sequencing of natural strains of Arabidopsis thaliana with short reads. Genome Res. 2008;18:2024–2033. doi: 10.1101/gr.080200.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dreszer TR, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: extensions and updates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40 (database issue):D918–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.