Abstract

The high co-morbidity between alcohol (ethanol) and nicotine abuse suggests that nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), thought to underlie nicotine dependence, may also be involved in alcohol dependence. The β2* nAChR subtype serves as a potential interface for these interactions since they are the principle mediators of nicotine dependence and have recently been shown to modul6ate some acute responses to ethanol. Therefore, the aim of this study was to more fully characterize the role of β2* nAChRs in ethanol-responsive behaviors in mice after acute exposure to the drug. We conducted a battery of tests in mice lacking the β2 coding gene (Chrnb2) or pretreated with a selective β2* nAChR antagonist for a range of ethanol-induced behaviors including locomotor depression, hypothermia, hypnosis, and anxiolysis. We also tested the effect of deletion on voluntary escalated ethanol consumption in an intermittent access two-bottle choice paradigm to determine the extent of these effects on drinking behavior. Our results showed that antagonism of β2* nAChRs modulated some acute behaviors, namely by reducing recovery time from hypnosis and enhancing the anxiolytic-like response produced by acute ethanol in mice. Chrnb2 deletion had no effect on ethanol drinking behavior, however. We provide further evidence that β2* nAChRs have a measurable role in mediating specific behavioral effects induced by acute ethanol exposure without affecting drinking behavior directly. We conclude that these receptors, along with being key components in nicotine dependence, may also present viable candidates in the discovery of the molecular underpinnings of alcohol dependence.

Keywords: Nicotinic Receptors, C57 mice, ethanol, nicotine, dihydro-beta-erythroidine, Beta 2 nAChRs

Introduction

Alcohol (ethanol) and nicotine addiction are two of the leading causes of preventable death worldwide. In the United States alone, these drugs are collectively abused by nearly 70 million Americans and kill 500,000 annually (Li et al. 2007). The high co-morbidity of alcohol and tobacco use are clear given the estimation that nearly 80–90% of alcoholics are regular smokers (Istvan and Matarazzo 1984; DiFranza and Guerrera 1990; Batel et al. 1995; Falk et al. 2006). This high co-morbidity of use increases the difficulty of achieving long-term abstinence with either drug (Larsson et al 2004a). Furthermore, there is a high genetic correlation between alcohol and nicotine dependent individuals suggesting common neurobiological mechanisms mediating co-abuse (True et al. 1999; Davis and de Fiebre 2006). Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) may be prime candidates for mediating this vulnerability to alcoholism and nicotine addiction.

Neuronal nAChRs are ligands-gated ion channels consisting of five transmembrane spanning proteins, or subunits. These subunits complex to form many combinations of nAChR subtype consisting of α (α2–α10) and/or β (β2–β4) subunits. β2* nAChRs (*denotes the presence of additional nicotinic subunits) represent the most widely distributed and best-characterized nAChR subtypes to date (Gotti et al 2007; Changeux 2005, 2009, 2010). This receptor subtype plays a critical role in nicotine reinforcing and rewarding properties of nicotine (Picciotto et al. 1998; Walters et al., 2006). For example, dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE), an antagonist selective for β2*-containing subtypes reduces nicotine self-administration and conditioned place preference in rodents, while deletion of the β2* gene reduces nicotine conditioned place preference and alters drug discrimination and conditioned taste aversion (Walters et al. 2006, Shoaib et al. 2002, Coen et al. 2008) in rodent. Due to the high co-abuse of nicotine and alcohol, studies on the role of the β2* nAChRs in alcohol dependence continue to emerge. For example, β2 Knockout (KO) mice are less sensitive to both ethanol’s acute effects in the acoustic startle response and to ethanol withdrawal signs compared with β2 wild-type (WT) mice (Owens et al. 2003, Butt et al. 2004). Interestingly, the impairment of contextual recall by ethanol was not affected in β2* KO mice (Wehner et al. 2004). In addition to the previously mentioned effects, full agonists such as nicotine and RJR-2403 decreased ethanol induced ataxia while a partial agonist, varenicline, a non-selective α4β2* nAChRs partial agonist, actually increases the sensitivity to this response (Taslim et al. 2008, 2010; Kamens et al. 2010a). Varenicline also increases sensitivity to the sedative-hypnotic effects of acute ethanol as tested in the rotarod and Loss of Righting Reflex assays (Kamens et al. 2010a).

In contrast to the acute administration studies previously mentioned, no changes in chronic ethanol drinking behavior in the two-bottle choice paradigm were found in the β2 KO mice compared to their WT counterparts (Kamens et al. 2010b). DHβE also had no effect on either ethanol consumption (Hendrickson et al. 2009; Kuzmin et al. 2009) or dopamine release in the ventral tegmental area nor nucleus accumbens in response to ethanol-associated cues (Ericson et al. 2003, 2008, Larsson et al 2004b). Interestingly, a polymorphism in the β2 gene (CHRNB2) has also been associated with the initial subjective response to alcohol in human subjects (Ehringer et al. 2007). Collectively, these studies suggest that β2* nAChRs may be important for modulating ethanol responses, particularly the pharmacological effects after acute exposure to the drug. The initial sensitivity of an individual to the acute effects of early alcohol exposure has long been recognized as an important endophenotype for alcoholism vulnerability. For example, studies conducted as early as the1980’s show that a group of individuals family history positive for alcoholism were less responsive to an acute alcohol challenge than family history negative individuals (Schuckit, 1985). Subsequent studies would go on to show that the level of response to acute alcohol exposure early in life is predictive of future drinking behavior and alcohol abuse liability (for review, see: Schuckit and Smith 2011, Crabbe et al. 2010).

The aim of our study was to more fully characterize the role of β2* nAChRs in ethanol-responsive behaviors in mice after acute exposure to the drug. To do this, we tested mice lacking the β2 coding gene (Chrnb2) or mice pretreated with a selective β2* nAChR antagonist for a range of ethanol-induced behaviors, namely locomotor depression, hypothermia, hypnosis, and anxiolysis. Furthermore, we tested mice lacking these receptor subunits for voluntary escalated ethanol consumption using an intermittent access two-bottle choice alcohol paradigm. We hypothesized that β2* nAChRs would play a more important role in affecting acute ethanol-responsive behaviors while having little to no effect on ethanol consumption.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). β2 KO mice; Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) subunits and their WT littermates were bred in an animal care facility at Virginia Commonwealth University. All the mice used in each experiment were backcrossed at least 10 to 12 generations. Mutant and wild types were obtained from crossing heterozygote mice. This breeding scheme controlled for any irregularities that might occur with crossing solely mutant animals. Mice were housed in a 21°C humidity-controlled Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC)-approved animal care facility. They were housed in groups of six and had free access to food and water under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 a.m.) schedule. Mice were 8–10 weeks of age and weighed approximately 20–25 g at the start of all the experiments. All experiments were performed during the normal light cycle (between 6:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m.) and the study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University. All studies were carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory animals.

Drugs

Dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) was purchased from Sigma- RBI (Natick, MA, USA). The drug was dissolved in 0.9% saline and injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a volume of 10 ml/kg body weight. Ethanol was also dissolved in 0.9% saline and prepared as a 20% (v/v) solution and presented as an i.p. injection for acute experiments or per os (o.p.) during the two-bottle choice experiment. DHβE doses (1.0 – 3.0 mg/kg) were based on published and unpublished studies from our lab that were within an effective range of doses for blocking the behavioral effects of nicotine (Damaj et al. 1995, 2003). Ethanol doses (2.0 – 3.5 g/kg) were chosen based on active doses in previous studies (Alanka et al. 1992, Browman et al. 2000).

Locomotor Activity Measurement

Locomotor depression induced by acute ethanol was assessed in Omnitech photocell activity cages (28 × 16.5 cm) (Columbus, OH) using a 3-day procedure. Each apparatus consisted of two banks of eight cells with locomotor activity recorded as the interruptions of the photocell beams for the duration of the test. Mice were allowed to acclimate to the room at least 1 hr before the beginning of the each day of the procedure. Animals were injected with saline on days 1 and 2, and then injected with 2.5 g/kg ethanol (i.p.) on day 3 after receiving a 10 min pretreatment with DHβE or saline (i.p.). For experiments with β2 KO mice, subjects were injected with saline on days 1 and 2, and then directly treated with either ethanol (2.5 g/kg) or saline alone on day 3. Locomotor activity scores were defined as the number of interruptions of the photobeam cells measured for 10 minutes. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of the number of photocell interruptions.

Body Temperature Measurement

Hypothermia induced by acute ethanol was measured using a standard rectal thermometer (Fischer Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) with probe (inserted ~24 mm). Five min after baseline temperatures were recorded, mice in the DHβE-pretreatment groups were injected with the drug or saline 10 min before treatment with 3.0 g/kg ethanol or saline, while β2 KO mice were directly treated with the same dose of ethanol or saline alone. Body temperature measurements 15- and 60 min-post ethanol injection were recorded in degrees Celsius (C°). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of the change in body temperature from baseline after treatment. The ambient temperature of the laboratory varied from 21–24°C from day to day.

Loss of Righting Reflex (LORR)

The sedative-hypnotic effects of ethanol were measured using the loss of righting reflex assay (LORR). Mice in the DHβE-pretreatment groups were injected with the drug or saline 10 min before treatment with 3.5 g/kg ethanol or saline, while β2 KO mice were directly treated with the same dose of ethanol or saline alone. Time started immediately after the ethanol injection and mice were monitored for initial LORR and placed in a supine position in a V-shaped trough. A subject was confirmed to have achieved LORR only after it was on its back for at least 30 seconds. Mice taking longer than 5 minutes to experience LORR were eliminated from the study due to the possibility of misplaced injection. We reported two scores for this assay. The first was the total time from ethanol injection until initial LORR, which was reported as latency to LORR. The second was total time required for the subject to right itself 3 times within 30 seconds from the onset of LORR, which was reported as LORR Duration. Data (mean ± SEM) were expressed as latency to LORR and LORR Duration in seconds.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

Reduction in anxiety-like behavior induced by acute ethanol was assessed using the elevated plus maze apparatus. This is an elevated platform consisting of two crossbars that create four arms. Two of these arms have walls (closed arms) and the other two arms are exposed (open arms). Because mice commonly display an innate fear of open, elevated places, an increase in the amount of time spent in the open arms is thought to represent a reduction in anxiety-like behavior. Mice were given at least 12 hrs to acclimate to the testing room. DHβE-pretreated mice were injected with the drug or saline 10 min before treatment with 2.0 g/kg ethanol or saline, while β2 KO mice were directly treated with either ethanol or saline alone. Subjects were then returned to their home cage for 15 minutes to allow ethanol to take effect and to avoid any hyperlocomotion from stress caused by the injection. Each subject was then placed briefly in a plastic container and transferred to the center of the maze. The subject was allowed to freely explore the apparatus for 5 minutes, with time starting immediately after placement in the center of the maze. Data (mean ± SEM) were expressed as the total time spent in the open arms in seconds. The number of crossovers was also recorded to account for any chances in locomotor activity.

Intermittent Access

Chronic ethanol drinking behavior was assessed using the intermittent access (IA) procedure as described by Hwa and colleagues (Hwa et al. 2011). This procedure is advantageous over the traditional two-bottle choice drinking procedure in that it produces escalation in ethanol drinking by repeated deprivation cycles thus better approximating human drinking behavior (Rodd et al. 2004). Briefly, β2 WT and KO mice were housed individually in cages one week prior to testing with ad libitum access to food and water. Three days before the end of acclimation week, water bottles were replaced with two drinking tubes, made from 10-ml serological pipettes containing a double bearing sipper tube and a rubber stopper on either end of the tube, filled with water. At the end of the acclimation period, one water tube was replaced with one ethanol filled with 3-, 6-, and 10% w/v ethanol on alternating days (Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday) while two water tubes were presented on the deprivation days (Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday). After one week, 20% (w/v) ethanol tubes were presented on alternating days (Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday) for the remainder of the experiment. Control mice were presented with continuous access to ethanol by presenting one 3% (w/v) ethanol tube on Sunday and Monday, 6% Tuesday and Wednesday, and 10% (w/v) ethanol Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. After one week, 20% (w/v) ethanol tubes were presented daily for the remainder of the experiment. Additionally, ethanol and water tubes were placed on two empty cages, which allowed for measurement of leakage and evaporation from the tubes. The average volume depleted from these “control” tubes was subtracted from the individual drinking volumes each day before data analysis. Intake was reported as g/kg ethanol consumed and preference as the ratio between of ethanol consumed divided by total amount of ethanol and water fluid intake (ml), combined. Additional measurements including body weight (g) and total fluid intake (ml) were also recorded. Data (mean ± SEM) were expressed as total intake or preference ratio.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using multiple standard analyses of variance (ANOVA) with treatment and/or genotype as independent variables. All analyses were followed by Newman-Kuewls or Bonferroni post-hoc tests where appropriate to further analyze significant data with the null hypothesis rejected at the 0.05 level. For the IA procedure, ethanol intake (g/kg), body weight (g), volume of ethanol intake (ml), water intake (ml), total fluid intake (ml), and ethanol preference ratio during the week of increasing ethanol concentrations (week 1) for each access group and genotype were analyzed with multiple three-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs), followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis when significant group effects were found (p < 0.05). During the maintenance phase with 20% ethanol (weeks 2–5), ethanol intake (g/kg), body weight (g), volume of ethanol intake (ml), water intake (ml), total fluid intake (ml), and ethanol preference ratio were analyzed between each treatment and genotype with multiple two-way repeated measures ANOVAs followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis when significant group effects were found (p < 0.05).

Results

Locomotor Activity Measurement

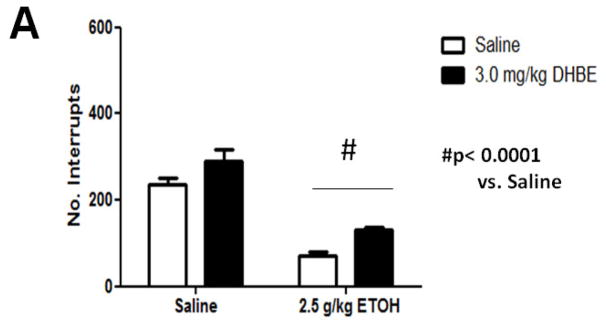

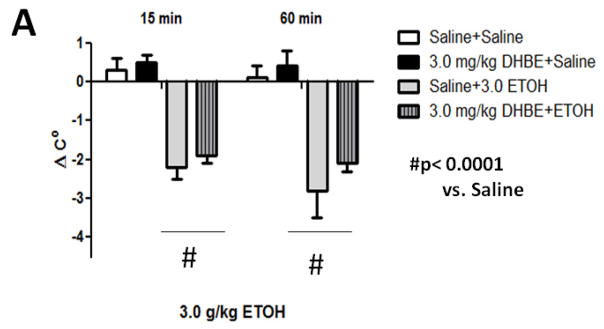

We tested locomotor activity 10 min after 2.5 g/kg ethanol injection (i.p.) since this is sufficient time for blood and brain ethanol concentrations to reach equilibrium (Smolen and Smolen 1989). Mice treated with ethanol displayed a significant decrease in locomotor activity (Figure 1A). One-way ANOVA analysis showed that ethanol produced a significant decrease in locomotor activity compared with findings for control animals [(F3, 20)= 6.821, p= 0.0024]. There was no effect of 3.0 mg/kg DHβE treatment on this ethanol-induced depression [(F1, 10)= 3.47, p= 0.0919]. Similarly, absence of the β2 gene in KO mice did not modulate locomotor depression induced by an acute injection of 2.5 g/kg ethanol (i.p.) (Figure 1B). A two-way ANOVA analysis showed a significant main effect of ethanol treatment [(F1, 19) = 56.85, p<0.0001] but not genotype [(F1, 19)= 0.019, p= 0.8913] nor interaction [(F1, 19)= 3.20, p= 0.08] on locomotor activity. Thus, the analysis suggests that neither the β2* antagonist, DHβE, nor Chrnb2 deletion affects acute ethanol-induced locomotor depression in mice.

Figure 1.

Effects of DHβE pretreatment and deletion of the Chrnb2 gene on ethanol-induced locomotor depression in mice. Data (mean ± SEM) represent total number of photocell interruptions of (A) C57BL/6J mice with 10 min DHβE pretreatment and (B) β2 KO mice after receiving an injection of 2.5 g/kg ethanol or saline. N= 6 per group.

Body Temperature Measurement

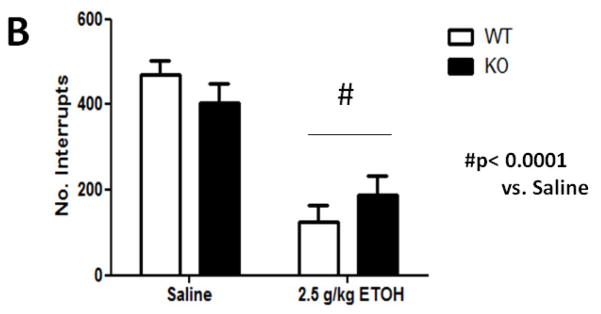

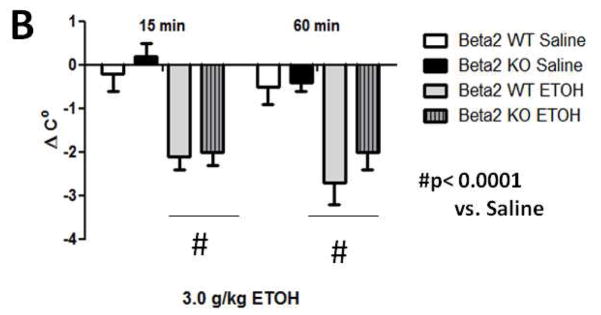

Treatment with 3.0 g/kg ethanol (i.p.) induced a significant drop in body temperature (Figure 2A). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed ethanol treatment caused significant hypothermia compared to saline control animals [F(3,18)= 17.359; p< 0.0001] at 15- and 60-min time points post ethanol injection. A dose of 3.0 mg/kg DHβE treatment did not produce significant changes [F (1,10)= 0.991; p= 0.3430] in ethanol-induced hypothermia compared to findings with control animals indicating this dose of DHβE has no effect on this measure of acute ethanol response. Deletion of the β2 gene also had no effect on hypothermia induced by an acute injection of 3.0 g/kg ethanol (i.p.) (Figure 2B). Three-way repeated measure ANOVA (genotype x treatment group x time) showed a main significant effect of ethanol treatment [F(1,20)= 0.126, p< 0.0001), but neither genotype [F(1,20)= 1.844, p< 0.1897] nor interaction [F(1,20)= 0.1897, p< 0.7263] on ethanol hypothermia. There were also no genotype differences detected between saline control groups. Taken together, these results suggest that pharmacological and genetic antagonism of β2* nAChRs have no effect on acute ethanol-induced hypothermia.

Figure 2.

Effects of DHβE pretreatment and deletion of the Chrnb2 gene have no effect on ethanol-induced hypothermia in C57BL/6J mice. Data (mean ± SEM) represent the change in body temperature from baseline in degrees Celsius of (A) mice with 10 min DHβE pretreatment and (B) β2 KO mice at 15- and 60 min time points after receiving an injection of 3.0 g/kg ethanol. N= 6 per group.

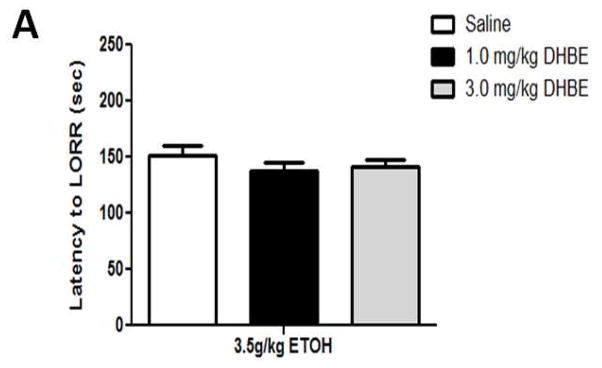

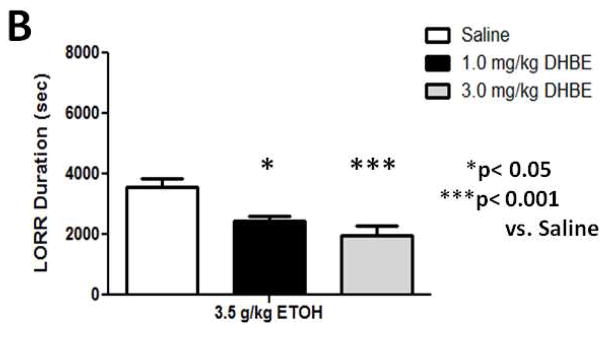

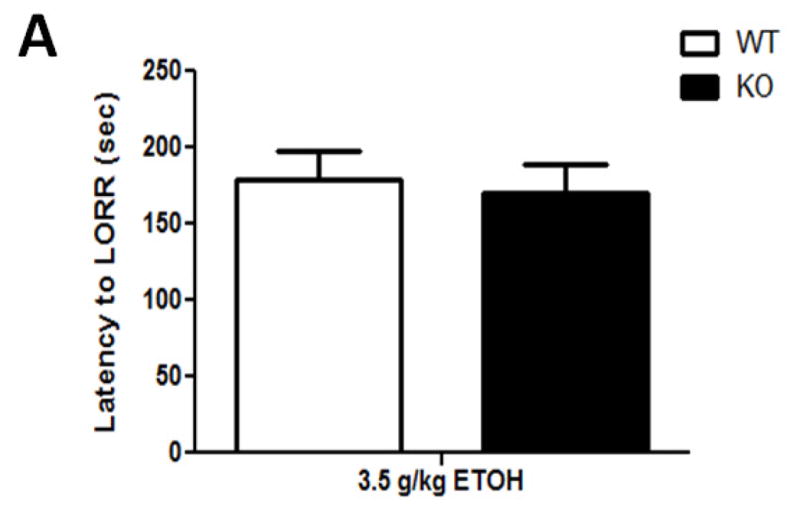

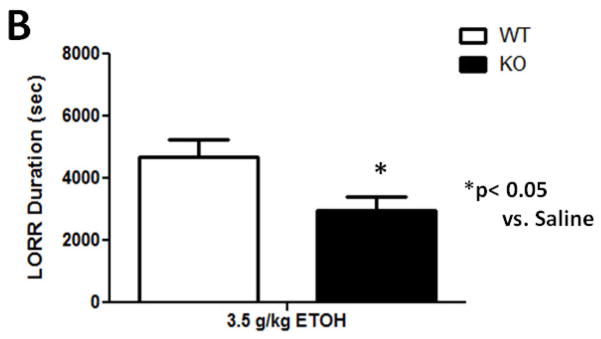

LORR

A dose of 3.5 g/kg ethanol had the intended effect of inducing LORR (Figure 3). A one-way ANOVA analysis revealed that while there was no significant effect of either 1.0- or 3.0 mg/kg DHβE treatment on latency to LORR onset ([F(3,35)= 0.456; p= 0.7144], Figure 3A), the nicotinic antagonist significantly reduced LORR duration at these doses ([F(1,20)= 6.982; p= 0.0156], Figure 3B). β2 KO mice showed a similar response (Figure 4) with one-way ANOVA analysis showing genotype did not have an effect on the latency to LORR onset ([F(1,13)= 0.92; p= 0.7669], Figure 4A) but did have a significant effect on LORR duration ([F(1,13)= 5.57; p= 0.346] between KO and WT mice (Figure 4B). β2 KO mice took less time to right themselves than β2 WT mice, thus displaying decreased response to the hypnotic effects induced by acute ethanol. These results show that pharmacological and genetic antagonism of β2 * nAChRs reduces the response to ethanol-induced hypnosis in naïve mice.

Figure 3.

DHβE pretreatment reduces ethanol-induced LORR duration while having no effect on LORR onset in C57BL/6J mice. Data (mean ± SEM) represent (A) latency to LORR onset and (B) total duration of LORR in seconds in mice with 10 min DHβE pretreatment after receiving an injection of 3.5 g/kg ethanol. N= 7–10 per group.

Figure 4.

Deletion of the Chrnb2 gene reduces ethanol-induced LORR duration while having no effect on LORR onset in C57BL/6J mice. Data (mean ± SEM) represent (A) latency to LORR onset and (B) total duration of LORR in seconds in mice with 10 min DHβE pretreatment after receiving an injection of 3.5 g/kg ethanol. N= 6–7 per group.

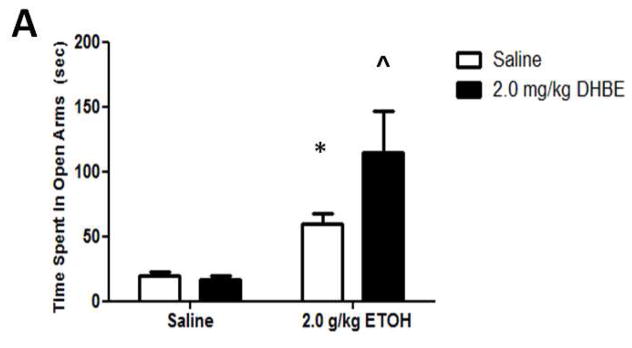

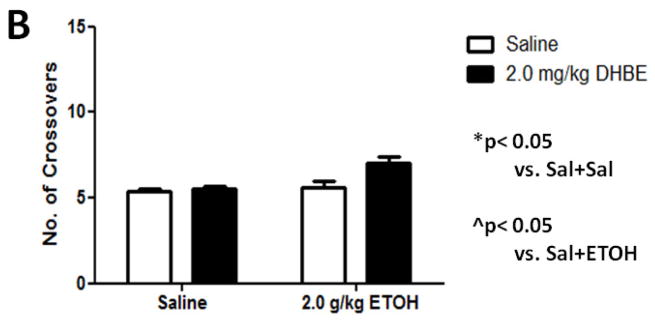

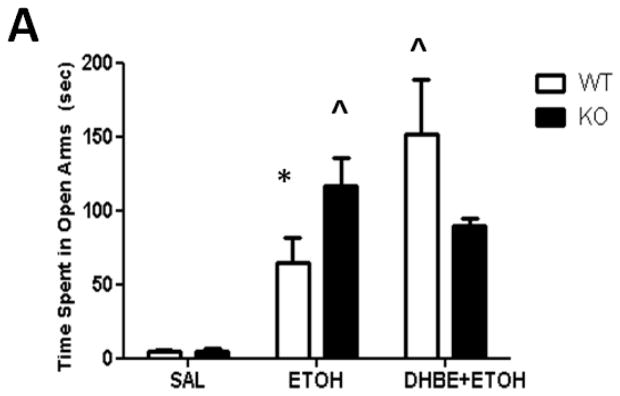

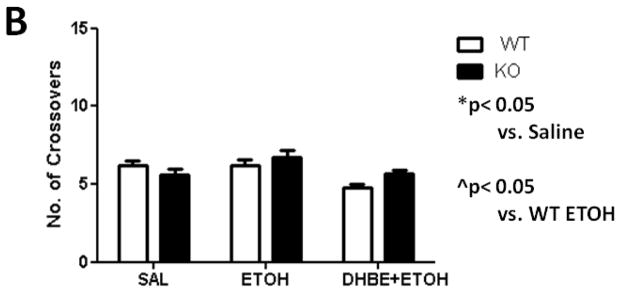

EPM

As expected, a dose of 2.0 g/kg ethanol caused an anxiolytic-like response in mice (Figure 5A) compared with saline-treated mice. Two-way ANOVA analysis showed a main significant of ethanol treatment [F(1,17)= 24.795; p= 0.0001] as well as interaction between ethanol and 2.0 mg/kg DHβE pretreatment [F(1,17)= 7.669; p= 0.0131, post-hoc p< 0.05] but not pretreatment. One-way ANOVA analysis of the number of crossovers revealed no significant differences between either group [F(3,18)= 2.16; p= 0.1011] (Figure 5B). The results in β2 KO mice showed that ethanol-induced increase in open arm time was also enhanced in these mice compared to WT (Figure 6A). Two-way ANOVA analysis of time spent in the open arms showed a significant main effect of treatment [F(1,17)= 33.711; p<.0001], genotype [F(1,17)= 7.38; p= 0.0147], and interaction [F(1,17)= 7.116; p= 0.0162]. Subsequent one-ANOVA analysis revealed a significant difference in ethanol-treated KO mice [F (1,10)= 5.521, p< 0.0407, post-hoc p< 0.05 ] compared to WT mice. No differences were detected in either genotype treated with saline. One-way ANOVA analysis of the number of crossovers revealed no significant differences between either group ([F (1,17)= 2.729, p< 0.1169], Figure 6B). To confirm if this effect is mediated through β2 nAChRs we also tested the effect of 2.0 mg/kg DHβE pretreatment in β2 KO and WT mice (Figure 5B). One-way ANOVA analysis revealed a trend for a KO-pretreated mice to spend less time in the open arms than their WT counterparts, though this trend was non-significant [F(1,10)= 2.770; p= 0.1270]. Furthermore, One-way ANOVA analysis was also used to compare DHβE-pretreated WT mice to WT mice from the previous experiment treated with ethanol alone, revealing that DHβE-pretreated WT mice did indeed spend more time in the open arms than the control [F(1,11)= 5.084; p=0.0455]. Thus, the data reveal that DHβE significantly increased ethanol-induced open arm in WT but not KO mice. Taken together, these data suggest that functional disruption of β2* nAChRs enhances aspects of the anxiety-reducing effects of acute ethanol administration as measured by the EPM.

Figure 5.

DHβE pretreatment enhances ethanol-induced increase in open arm time without affecting locomotor activity. Data (mean ± SEM) represent (A) time spent in open arms in seconds and (B) total number of crossovers in mice with 10 min DHβE pretreatment after receiving an injection of 2.0 g/kg ethanol. N= 7–10 per group.

Figure 6.

Deletion of the Chrnb2 gene enhances ethanol-induced increase in open arm time without affecting locomotor activity. Data (mean ± SEM) represent (A) time spent in open arms in seconds and (B) total number of crossovers in β2 KO mice after receiving an injection of 2.0 g/kg ethanol. N= 7 per group.

Intermittent Access

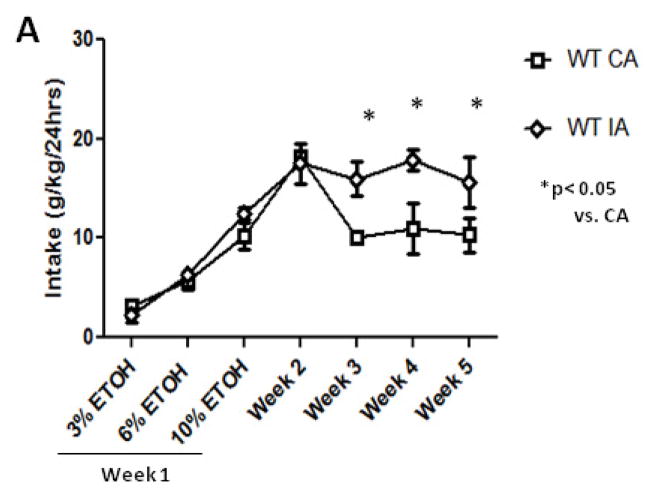

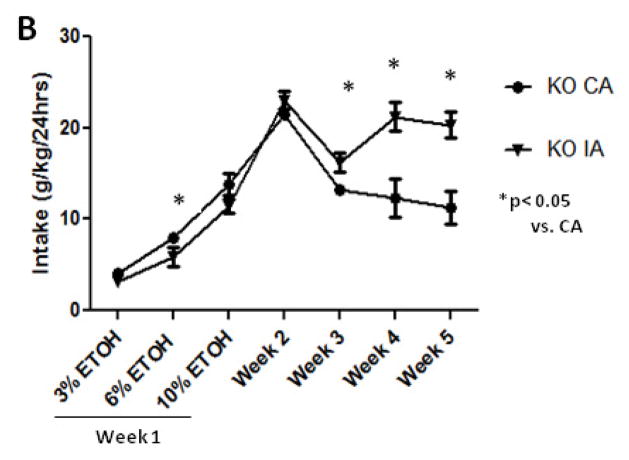

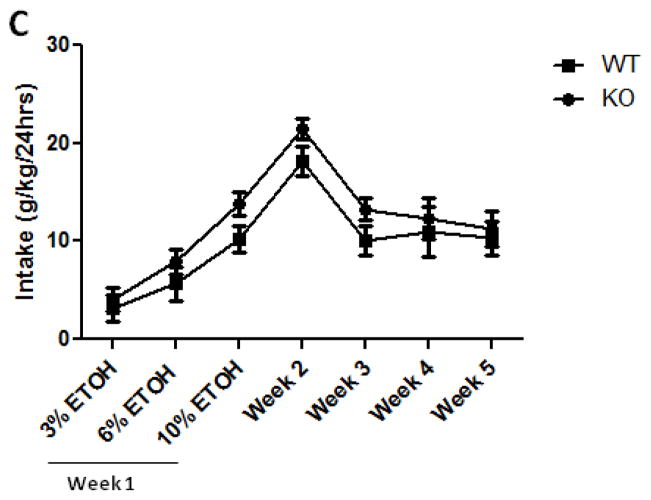

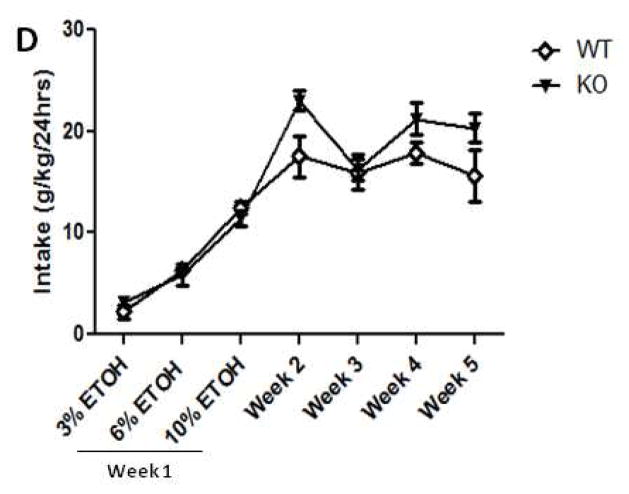

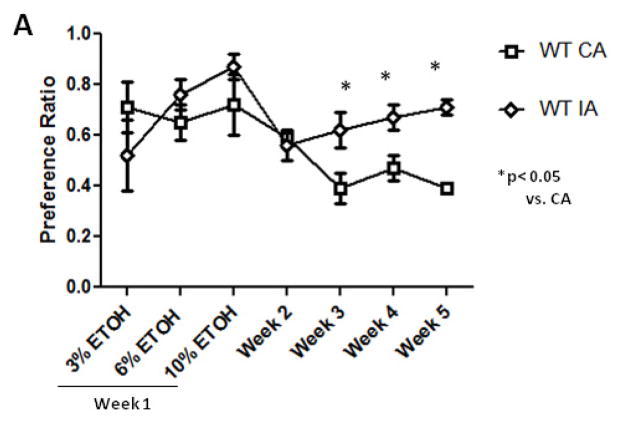

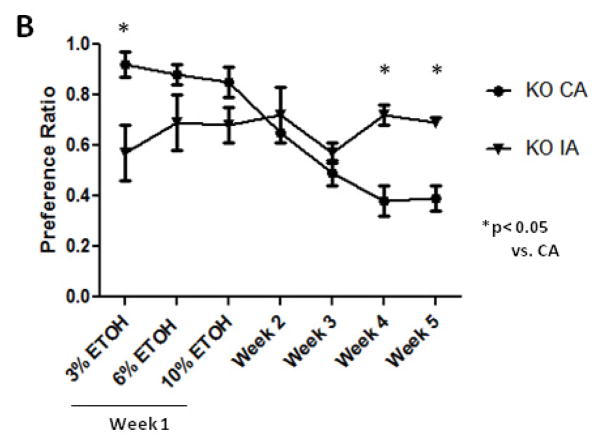

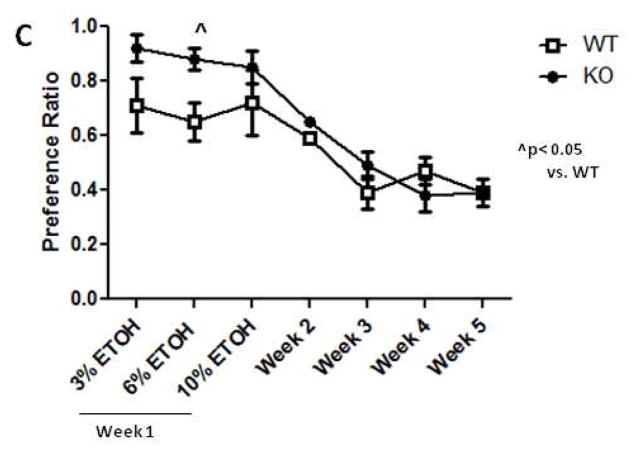

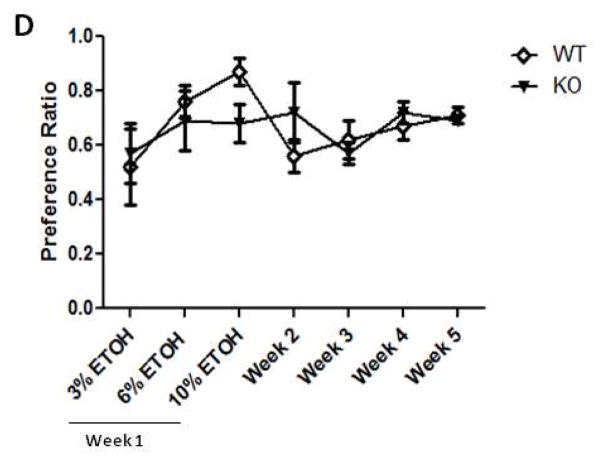

Mice given either intermittent or continuous two-bottle choice access to water and increasing concentrations of ethanol during the acclimation week (Week 1) displayed a concentration-dependent increase in ethanol intake (Figure 7). An initial three-way ANOVA (access group x concentration x genotype) revealed main significant effects of concentration [F(2,63)=130.457, p= 0.0001, post-hoc <0.0001], genotype [F(1,63)= 5.317, p= 0.0244, post-hoc< 0.05], and interaction [F(1,63)= 7.892, p= 0.0066]. Separate one-way ANOVA analyses for KO and WT mice at each concentration showed that while WT mice with continuous or intermittent access displayed similar ethanol intake, KO mice with continuous access had significantly higher intake at 6% ethanol [F(1,10)= 6.011, p= 0.034] than their counterparts with intermittent access. Thus, the data show that while the increase in ethanol intake during the first week was driven largely by concentration, genotype did modestly influence ethanol depending on access conditions. Furthermore, the concentration-dependent increase in ethanol intake was not due to differences in total fluid intake between groups as three-way ANOVA analysis showed no difference between groups [F(2,63)= 0.249, p= 0.7807]. As for the preference results (Figure 8), three-way ANOVA revealed a main significant effect of access group [F(1,63)= 4.678, p= 0.0344] and access group x genotype interaction [F(1,63)= 6.750, p= 0.0117] with further analysis supporting the effect of access group (post hoc, p< 0.05) but not genotype (post hoc, p> 0.05) on ethanol preference for 3% ethanol ([F(1,10)= 8.722, p= 0.0145]. Thus, while this effect on preference did not depend on concentration nor genotype, it seemed that the conditions of access to ethanol, either intermittent or continuous, did initially affect preference for ethanol in drug naïve mice.

Figure 7.

Deletion of the Chrnb2 gene has no effect on intermittent access ethanol intake in C57BL/6J mice. Data (mean ± SEM) in the top graphs represent intake in g/kg in (A) WT and (B) KO intermittent (IA) vs. continuous access (CA) groups at 3-, 6-, 10-, and 20% (w/v) ethanol during weeks 1–5. The bottom graphs display the same data, but rearranged to show comparisons between each genotype during (C) continuous and (D) intermittent access exposure. N= 7 per group.

Figure 8.

Deletion of the Chrnb2 gene has no effect on intermittent access ethanol preference in C57BL/6J mice. Data (mean ± SEM) in the top graphs represent the preference ratio in (A) WT and (B) KO intermittent vs. continuous access groups at 3-, 6-, 10-, and 20% (w/v) ethanol during weeks 1–5. The bottom graphs display the same data, but rearranged to show comparisons between each genotype during (C) continuous and (D) intermittent access exposure. N= 7 per group.

For the maintenance phase of the experiment, weeks 2–5, intermittent access to ethanol had the intended effect of increasing both intake and preference for ethanol in each test group (Table 2). Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA analysis of ethanol intake revealed a significant main effect of access group [F(1,16)= 18.65, p= 0.0005] but not genotype [F(1,16)= , p= 0.0687] nor interaction [F(1,16)= 0.206, p= 0.6557] over the course of the maintenance phase. Separate one-way repeated measures ANOVA analyses for each week revealed significantly higher intake in intermittent access mice compared to continuous access mice during week 3 [F(1,23)= 5.653., p= 0.261], week 4 [F(1,23)= 26.718, p< 0.0001], and week 5 [F(1,23)= 20.139, p= 0.0002]. The results for preference were similar with two-way repeated-measures ANOVA analysis revealing a significant main effect of access group [F(1,17)= 20.361 p= 0.0003] but not genotype [F(1,17)= 0.732 p= 0.732] nor interaction [F(1,17)= 0.002, p= 0.9661] over the course of the maintenance phase (Table 2). Separate one-way repeated measures ANOVA analyses for each week revealed significantly higher preference in intermittent access mice compared to continuous access at mice during week 4 [F(1,23)= 15.006, p= 0.0007], and week 5 [F(1,23)= 20.445, p= 0.0002]. Taken together, the results show that intermittent exposure to ethanol induces escalation of drinking behavior of a similar magnitude in both β2 WT and KO mice.

Table 2.

Average Ethanol Intake and Preference in Beta 2 WT and KO mice during the maintenance phase of the IA procedure. Data (mean ± SEM) represent intake in g/kg and preference ratio, respectively, for each group.

| 20% Ethanol Intake and Preference in Beta 2 WT and KO mice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA Group | IA Group | |||

| Genotype | Beta 2 WT | Beta 2 KO | Beta 2 WT | Beta 2 KO |

| Intake Weeks 2–5 | 12.35 ± 1.80 | 14.59 ± 1.55 | 16.73 ± 1.48a | 20.20 ± 1.26a |

| Preference Weeks 2–5 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.64 ± 0.05a | 0.68 ± 0.05a |

Represents significantly higher intake or preference than CA

Discussion

The goal of our studies was to further characterize the involvement of β2* nAChRs in acute ethanol-responsive behaviors as well as in ethanol drinking behavior. We examined the effect of pharmacological antagonism and genetic deletion of β2* nAChRs on a wide range of acute responses including locomotor depression, hypothermia, LORR, and reduction of anxiety-like behavior in the EPM, as well as in escalated drinking behavior using an intermittent access model. As hypothesized, manipulation of β2* nAChRs modulated some acute behaviors, namely reducing LORR duration and increasing time spent in the open arms in the EPM, while having minimal effect on ethanol drinking behavior.

The observation that drinking behavior in the intermittent access paradigm did not differ between β2 WT and KO mice show that β2* nAChRs do not affect chronic drinking behavior, even after repeated cycles of deprivation. While β2 KO mice appeared to display a tendency for higher intake and preference in the initial phase compared to the WT mice, the two genotypes did not significantly differ in their levels of intake or preference. In line of our observations, studies in rats and mice have not implicated these subunits in ethanol drinking behavior in the mouse two-bottle choice paradigm (Kamens et al. 2010b) and self-administration procedure in rats (Hendrickson et al. 2009; Kuzmin et al. 2009). It is also noteworthy that additional studies using this same drinking model showed a lack of involvement of α6*, a subtype which often co-assembles with β2* (Yang et al. 2009, Kamens et al. 2012). Furthermore, the β2* antagonist, DHβE, had no effect on drinking behavior in models testing additional aspects of ethanol consumption such as acute binge drinking and operant self-administration behavior (Lé et al. 2000, Kuzmin et al. 2009, Hendrickson et al. 2009). Taken together with our results, these data collectively demonstrate that antagonism of β2* nAChRs do not have a major effect on ethanol consumption.

While we observed no effect of β2* modulation on ethanol drinking directly, we did find that functional disruption of β2* nAChRs differentially affects some acute ethanol-responsive behaviors. Interestingly, these effects did not extend to all the acute responses measured, as no change in ethanol-induced hypothermia, locomotor depression, or latency to LORR were detected. We tested a wide range of acute ethanol responses across a range of active doses of the drug since this approach may provide convergent information about the role nAChRs in ethanol-responsive behaviors. β2* nAChRs do not play an important role in ethanol-induced hypothermia nor locomotor activity depression. Our locomotor results were strengthened by the fact that β2* nAChR antagonism also had no effect on latency to LORR, another measure of initial sensitivity to ethanol-induced sedation (Ponomarev and Crabbe, 2002b). Interestingly, recent pharmacological studies in mice and rats suggested a role for α3β4/α3β2 nAChR subtypes in ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation (Larsson et al. 2002, Kamens et al. 2008). These findings are also supported by Kamens et al. (2009) study that showed that mice overexpressing α3 subunits in the brain were less sensitive to this acute effect of ethanol. Unfortunately, our β2 KO mice exist on a C57BL/6 background that shows a minimal stimulant response to ethanol (Demarest et al.1999; Randall et al, 1975).

The results that DHβE-pretreated and β2 KO mice displayed a significant difference in LORR duration and not latency to LORR were very intriguing. It is generally accepted that level of response to acute ethanol challenge may represent a combination of initial sensitivity to acute ethanol exposure and acute functional tolerance directly following exposure (Ponomarev and Crabbe 2002b). Because latency to LORR and LORR duration may correlate to these two respective measures, the results may indicate that disruption of β2* nAChR activity enhances the rate of the neuronal tolerance that develops minutes to hours after early ethanol exposure without necessarily affecting the initial sensitivity to ethanol’s effects. This may explain why a difference in KO mice was only seen in the LORR assay, and not the locomotor depression assay, since the 10 min time window measured in the latter may not have been long enough to observe β2’s influence on this behavior. While ethanol pharmacokinetics was not studied in the β2 KO and WT mice, we believe that differences in ethanol metabolism between the two genotypes do not play an important role in the decrease in the LORR phenotype for several reasons. A similar decrease in the LORR response was also seen with the β2* antagonist, DHβE. Furthermore, no difference in hypothermia and hypomotility induced by ethanol was found between β2 KO and WT mice. In fact, we observed an increase in ethanol-induced anxiolysis in the β2 KO mice compared to the WT counterparts. The α7 and α6 nAChR subunits have also been implicated in the LORR phenotype. In contrast to our results obtained in the β2 KO mice, however, mice lacking α6 and α7 subunits took longer to right themselves in the LORR paradigm compared to WT animals (Bowers et al., 2005; Kamens et al., 2012). These data suggest that various nAChR subtypes differentially modulate this behavioral trait. They also suggest that α6*-containing nAChR subtypes involved in this phenotype do not probably associate with β2 subunits.

Our results also showed that both DHβE-pretreated and β2* KO mice demonstrated an enhanced response to ethanol’s effect on reducing anxiety-like behavior in these subjects during the EPM test. These data may suggest that the presence of β2* nAChRs attenuate some aspects of the anxiolytic effects induced by acute ethanol administration. The experiment showing the attenuated effect of DHβE pretreatment in β2 KO mice seems to corroborate this idea. Furthermore, this behavior was not due to changes in animal locomotor activity as there was no difference in the number of crossovers in either DHβE-pretreated or β2 KO mice. It may be possible that β2* nAChRs mediate an endogenous pathway(s) that negatively modulate ethanol’s effects on this behavioral trait. Interestingly, β2 nAChR subunits are expressed in brain regions including the amygdala, the hippocampus, and limbic regions, which are known to regulate anxiety behaviors (Silveira et al. 1993, Walf et al. 2007, Gotti et al. 2007). When used appropriately, the EPM test can be a very valuable tool in drug testing and our results suggest that one aspect of anxiety and emotional behavior is modulated by alcohol-nicotinic interaction. Nevertheless, we realize it is likely that different tests for anxiety-like behaviors will measure somewhat different forms of emotional behavior and anxiety, which may be mediated by distinct neural circuits and genes. Investigating additional models that test different aspects of anxiety in order to further understand the nature of the role of β2 nAChR subunits in ethanol’s anxiolytic effects would address this issue. The implications of such studies could be important, especially when considering that anxiety behavior is thought to serve as a motivating factor for sustained alcohol consumption in humans that may increase risk for excessive drinking in the future (Spanagel et al. 1995, Zimmerman et al. 2003). It would be expected that an increase in the anxiolytic response to ethanol would increase ethanol drinking.

Several subunits such as α4, α5, α6, and β3 are often coexpressed with β2 subunits generating multiple β2-containing nAChR subtypes (Gotti et al. 2007). While our studies did not address the composition of β2* subtypes involved in ethanol’s effects, our data likely suggest the involvement of α2β2* subtypes due the similarity of the results displayed between mice pretreated with DHβE, an antagonist with high affinity for α4β2* nAChRs, and β2 KO mice. A limitation of our study is the chance that the effects observed in the β2 KO mice were due to compensatory or developmental changes that occur with the deletion of the β2 gene. While the expression of many subunits nAChRs, namely α4, α5, β4, and β3, are not altered by removal of the β2 gene (Picciotto et al. 1995, 1998), compensatory mechanisms with other nicotinic subunits or non-nicotinic mechanisms is still unknown. Importantly, our results with β2 KO mice were complemented with those seen with DHβE, a selective β2* nAChRs antagonist.

Our results seem to complement the human genetics studies providing support for the role of Chrnb2 in alcohol behaviors. Consistent with what we observed in animal models, human genetic association studies have implicated Chrnb2 in alcohol behaviors since an association between polymorphisms in the Chrnb2 gene and initial subjective response to early alcohol exposure was found (Ehringer et al. 2007). Therefore, nicotinic receptors, along with being key components in nicotine dependence, may also present viable candidates in the discovery of molecular underpinnings of behaviors related to alcohol dependence. Our results support the hypothesis that behavioral responses to alcohol and nicotine are likely to be differentially modulated by specific nicotinic subunits.

Table 1.

Experimental Design and Timeline of the Intermittent Access procedure. During Week 1, intermittent access mice were presented choice of water and 3-, 6-, and 10% w/v ethanol on Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday, respectively. Continuous access mice received 3% (w/v) ethanol on Sunday and Monday, 6% Tuesday and Wednesday, and 10% ethanol Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. During Weeks 2–5, 20% (w/v) ethanol was presented on Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday to intermittent access (IA) mice and daily continuous access (CA) mice, respectively. Only data from ethanol exposure days were reported for each group.

| Characterization of Ethanol Consumption in Beta 2 WT and KO mice | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Week 1 | Weeks 2–5 | ||||||||||||

| Day | Sun | Mon | Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat | Sun | Mon | Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat |

| IA Group | 3% (w/v) ETOH | H2O | 6% (w/v) ETOH | H2O | 10% (w/v) ETOH | H2O | H2O | 20% (w/v) ETOH | H2O | 20% (w/v) ETOH | H2O | 20% (w/v) ETOH | H2O | H2O |

| CA Group | 3% (w/v) ETOH | 3% (w/v) ETOH | 6% (w/v) ETOH | 6% (w/v) ETOH | 10% (w/v) ETOH | 10% (w/v) ETOH | 10% (w/v) ETOH | 20% (w/v) ETOH | 20% (w/v) ETOH | 20% (w/v) ETOH | 20% (w/v) ETOH | 20% (w/v) ETOH | 20% (w/v) ETOH | 20% (w/v) ETOH |

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tie Shan-Han for his technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DA-019377.

ABBREVIATIONS

- nAChR(s)

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor(s)

- s.c

subcutaneous injection; subunits

- DHβE

dihydro-beta-erythroidine

- i.p

intraperitoneal injection

- WT

wildtype

- KO

knockout

- MEC

mecamylamine

- CNS

central nervous system

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alkana RL, Finn DA, Jones BL, Kobayashi LS, Babbini M, Bejanian M, et al. Genetically determined differences in the antagonistic effect of pressure on ethanol-induced loss of righting reflex in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16(1):17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batel P, Pessione F, Matre C, Rueff B. Relationship between alcohol and tobacco dependencies among alcoholics who smoke. Addiction. 1995;90(7):977–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90797711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers B, McClure Begley T, Keller J, Paylor R, Collins A, Wehner J. Deletion of the alpha7 nicotinic receptor subunit gene results in increased sensitivity to several behavioral effects produced by alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(3):295–302. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156116.40817.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browman KE, Rustay NR, Nikolaidis N, Crawshaw L, Crabbe JC. Sensitivity and tolerance to ethanol in mouse lines selected for ethanol-induced hypothermia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67(4):821–829. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt C, King N, Stitzel J, Collins A. Interaction of the nicotinic cholinergic system with ethanol withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308(2):591–599. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone A, Moroni M, Groot-Kormelink P, Bermudez I. Pentameric concatenated (alpha4)(2)(beta2)(3) and (alpha4)(3)(beta2)(2) nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Subunit arrangement determines functional expression. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(6):970–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux JP. Nicotine addiction and nicotinic receptors: Lessons from genetically modified mice. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(6):389–401. doi: 10.1038/nrn2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux J. Nicotinic receptors and nicotine addiction. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 2009;332(5):421–425. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Coe JW, Hurst RS, et al. Partial agonists of the alpha3beta4(*) neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor reduce ethanol consumption and seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(3):603–615. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen K, Adamson KL, Corrigall W. Medication-related pharmacological manipulations of nicotine self-administration in the rat maintained on fixed- and progressive-ratio schedules of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2009;201(4):557–568. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Bell RL, Ehlers CL. Human and laboratory rodent low response to alcohol: Is better consilience possible? Addiction Biol. 2010;15(2):125–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI, Kao W, Martin BR. Characterization of spontaneous and precipitated nicotine withdrawal in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307(2):526–534. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI, Welch SP, Martin BR. In vivo pharmacological effects of dihydro-beta-erythroidine, a nicotinic antagonist, in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1995;117(1):67–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02245100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TJ, de Fiebre CM. Alcohol’s actions on neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):179–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest K, Hitzemann B, Phillips T, Hitzemann R. Ethanol-induced expression of c-fos differentiates the FAST and SLOW selected lines of mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23(1):87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Guerrera MP. Alcoholism and smoking. J Stud Alcohol. 1990;51(2):130–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer MA, Clegg HV, Collins AC, Corley RP, Crowley T, Hewitt JK, et al. Association of the neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 subunit gene (CHRNB2) with subjective responses to alcohol and nicotine. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B(5):596–604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Lof E, Stomberg R, Chau P, Soderpalm B. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the anterior, but not posterior, ventral tegmental area mediate ethanol-induced elevation of accumbal dopamine levels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326(1):76–82. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Molander A, Lf E, Engel J, Sderpalm B. Ethanol elevates accumbal dopamine levels via indirect activation of ventral tegmental nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;467(1–3):85. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Yi H, Hiller-Sturmhfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Yi H, Hiller-Sturmhfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego X, Ruiz Medina J, Valverde O, Molas S, Robles N, Sabri J, et al. Transgenic over expression of nicotinic receptor alpha 5, alpha 3, and beta 4 subunit genes reduces ethanol intake in mice. Alcohol. 2012;46(3):205–15. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Gaimarri A, Zanardi A, Clementi F, Zoli M. Heterogeneity and complexity of native brain nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74(8):1102. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Tapper AR. Modulation of ethanol drinking-in-the-dark by mecamylamine and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204(4):563–572. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1488-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa L, Chu A, Levinson S, Kayyali T, Debold J, Miczek K. Persistent escalation of alcohol drinking in C57BL/6J mice with intermittent access to 20% ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(11):1938–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istvan J, Matarazzo JD. Tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine use: A review of their interrelationships. Psychol Bull. 1984;95(2):301–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerlhag E, Grotli M, Luthman K, Svensson L, Engel JA. Role of the subunit composition of central nicotinic acetylcholine receptors for the stimulatory and dopamine-enhancing effects of ethanol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41(5):486–493. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens H, Hoft N, Cox R, Miyamoto J, Ehringer M. The α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit influences ethanol-induced sedation. Alcohol. 2012;46(5):463–71. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens H, Andersen J, Picciotto M. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline increases the ataxic and sedative-hypnotic effects of acute ethanol administration in C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(12):2053–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR. Modulation of ethanol consumption by genetic and pharmacological manipulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208(4):613–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, McKinnon CS, Li N, Helms ML, Belknap JK, Phillips TJ. The alpha 3 subunit gene of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is a candidate gene for ethanol stimulation. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8(6):600–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Phillips TJ. A role for neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in ethanol-induced stimulation, but not cocaine- or methamphetamine-induced stimulation. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196(3):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0969-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keir WJ, Deitrich RA. Development of central nervous system sensitivity to ethanol and pentobarbital in short- and long-sleep mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254(3):831–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliethermes C. Anxiety-like behaviors following chronic ethanol exposure. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;28(8):837–850. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin A, Jerlhag E, Liljequist S, Engel J. Effects of subunit selective nACh receptors on operant ethanol self-administration and relapse-like ethanol-drinking behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2009;203(1):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lé AD, Lo S, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Marinelli P, Funk D. Coadministration of intravenous nicotine and oral alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208(3):475–86. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1746-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lé AD, Corrigall WA, Harding JW, Juzytsch W, Li TK. Involvement of nicotinic receptors in alcohol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(2):155–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A, Engel JA. Neurochemical and behavioral studies on ethanol and nicotine interactions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27(8):713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A, Svensson L, Soderpalm B, Engel JA. Role of different nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mediating behavioral and neurochemical effects of ethanol in mice. Alcohol. 2002;28(3):157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A, Jerlhag E, Svensson L, Soderpalm B, Engel JA. Is an alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive mechanism involved in the neurochemical, stimulatory, and rewarding effects of ethanol? Alcohol. 2004;34(2–3):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Hewitt B, Grant B. Is there a future for quantifying drinking in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of alcohol use disorders? Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42(2):57. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Harrison EL, O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault JM, et al. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(3):801–805. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JC, Balogh SA, McClure-Begley TD, Butt CM, Labarca C, Lester HA, et al. Alpha 4 beta 2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors modulate the effects of ethanol and nicotine on the acoustic startle response. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(12):1867–1875. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000102700.72447.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Léna, Marubio LM, Pich EM, et al. Acetylcholine receptors containing the beta2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature. 1998;391(6663):173–7. doi: 10.1038/34413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Léna C, Bessis A, Lallemand Y, Le Novére N, et al. Abnormal avoidance learning in mice lacking functional high-affinity nicotine receptor in the brain. Nature. 1995;374(6517):65–67. doi: 10.1038/374065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarev I, Crabbe JC. Ethanol-induced activation and rapid development of tolerance may have some underlying genes in common. Genes Brain Behav. 2002;1(2):82–87. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2002.10203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarev I, Crabbe JC. A novel method to assess initial sensitivity and acute functional tolerance to hypnotic effects of ethanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302(1):257–263. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd Z, Bell R, Sable HJK, Murphy J, McBride W. Recent advances in animal models of alcohol craving and relapse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79(3):439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis-Segura C, Spanagel R. Behavioural assessment of drug reinforcement and addictive features in rodents: An overview. Addiction Biol. 2006;11(1):2–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. Onset and course of alcoholism over 25 years in middle class men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Ethanol-induced changes in body sway in men at high alcoholism risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(4):375–379. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790270065007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib M, Gommans J, Morley A, Stolerman IP, Grailhe R, Changeux J. The role of nicotinic receptor beta-2 subunits in nicotine discrimination and conditioned taste aversion. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42(4):530–539. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira MC, Sandner G, Graeff FG. Induction of fos immunoreactivity in the brain by exposure to the elevated plus-maze. Behav Brain Res. 1993;56(1):115–118. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90028-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Mogg A, Tafi E, Peacey E, Pullar I, Szekeres P, et al. Ligands selective for alpha4beta2 but not alpha3beta4 or alpha7 nicotinic receptors generalise to the nicotine discriminative stimulus in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190(2):157–170. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen A, Smolen TN. Reproducibility of ethanol elimination rates in long-sleep and short-sleep mice. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50(6):519–524. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Montkowski A, Allingham K, Sthr T, Shoaib M, Holsboer F, et al. Anxiety: A potential predictor of vulnerability to the initiation of ethanol self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1995;122(4):369–373. doi: 10.1007/BF02246268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensland P, Simms J, Holgate J, Richards J, Bartlett S. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(30):12518–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705368104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabakoff B, Ritzmann RF. Acute tolerance in inbred and selected lines of mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1979;4(1–2):87–90. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(79)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taslim N, Saeed Dar M. The role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) α7 subtype in the functional interaction between nicotine and ethanol in mouse cerebellum. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;35(3):540–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taslim N, Al Rejaie S, Saeed Dar M. Attenuation of ethanol-induced ataxia by alpha(4)beta(2) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtype in mouse cerebellum: A functional interaction. Neuroscience. 2008;157(1):204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True WR, Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, et al. Common genetic vulnerability for nicotine and alcohol dependence in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):655–661. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf A, Frye C. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nature Protoc. 2007;2(2):322–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters C, Brown S, Changeux J, Martin B, Damaj MI. The beta2 but not alpha7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is required for nicotine-conditioned place preference in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184(3–4):339–44. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner J, Radcliffe R. Cued and contextual fear conditioning in mice. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. 2004;Chapter 8(Unit 8):5C. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0805cs27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Jin G, Wu J. Mysterious alpha6-containing nAChRs: Function, pharmacology, and pathophysiology. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2009;30(6):740–51. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: A 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1211–22. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]