Abstract

Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) is a potent trophic factor for midbrain dopamine (DA) neurons, but its in vivo function and signaling mechanisms are not entirely understood. We show that the transcriptional cofactor homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) is required for the TGFβ-mediated survival of mouse DA neurons. The targeted deletion of Hipk2 has no deleterious effect on the neurogenesis of DA neurons, but leads to a selective loss of these neurons that is due to increased apoptosis during programmed cell death. As a consequence, Hipk2−/− mutants show an array of psychomotor abnormalities. The function of HIPK2 depends on its interaction with receptor-regulated Smads to activate TGFβ target genes. In support of this notion, DA neurons from Hipk2−/− mutants fail to survive in the presence of TGFβ3 and Tgfβ3−/− mutants show DA neuron abnormalities similar to those seen in Hipk2−/− mutants. These data underscore the importance of the TGFβ-Smad-HIPK2 pathway in the survival of DA neurons and its potential as a therapeutic target for promoting DA neuron survival during neurodegeneration.

Ventral midbrain DA neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) control extrapyramidal movement and a variety of cognitive functions, such as motivation, drive, addiction and reward behaviors. The selective loss of DA neurons, or perturbations to the neural circuits established by DA neurons, such as the nigrostriatal and mesolimbic pathways, have been implicated in several neurodegenerative conditions, including Parkinson’s disease1,2. After the initial phase of neurogenesis, DA neurons undergo a period of programmed cell death (PCD) during the perinatal stages. In rodents, the majority of PCD in DA neurons occurs during the perinatal stages, from postnatal day 0 (P0) to P4, with a smaller amount of PCD detected at P14 (ref. 3). Despite the occurrence of PCD, the number of neurons in the SNpc, as detected by Nissl or tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity, progressively increase from P0 to P7 and reaches a plateau at P14.

Although the detailed mechanisms that regulate PCD in DA neurons are unknown, it has been proposed that, in a manner similar to sensory neurons and spinal motoneurons4, neurotrophic factors and their signaling mechanisms may promote the survival of DA neurons. Indeed, several pro-survival trophic factors for DA neurons have been identified by using in vitro cultures of dissociated DA neurons from the ventral midbrain of mouse embryos at embryonic days 13.5–14.5 (E13.5–14.5). These include brain-derived neurotrophic factor5, neurotrophin-4 (ref. 6), glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)7 and TGFβ8,9. Most of these trophic factors have well-documented functions in regulating the survival of sensory, sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons during neurogenesis10,11, which raises the possibility that they may also provide survival cues to DA neurons during development4,12 and thereby control the final number of DA neurons.

Several recent studies provide supporting evidence that links neurotrophic factors to PCD in DA neurons. For instance, expression of the GDNF receptors c-ret and glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor family receptor α1 (GFRα1) has been detected in midbrain DA neurons during development and in postnatal brains. As would be expected from a target-derived trophic factor, GDNF mRNA is detected in the medium-sized striatal neurons, the presumptive target of DA neurons, at perinatal stages, but its concentration is significantly reduced after P14. The ectopic expression of GDNF in the striatum either by direct injection or by a transgenic approach reduces the magnitude of PCD in the DA neurons of the SNpc at perinatal stages13,14. Conversely, the injection of a neutralizing antibody to GDNF enhances cell death during the first wave of PCD, but has no detectable effect on the second wave13. Although these results support the notion that GDNF is a pro-survival trophic factor, experiments with mice that have a targeted deletion in Gdnf or Gfrα1 show no evidence of a neuronal deficiency in the SNpc at P015–17. The exact cause for this discrepancy is still unclear. It is possible that the early perinatal lethality of Gdnf and Gfrα1 mutants may have prevented the examination of the effect of GDNF in postnatal DA neurons. Alternatively, additional trophic factors could act independently of, or synergistically with, GDNF to promote the survival of midbrain DA neurons during PCD.

One potential candidate for a pro-survival trophic factor is TGFβ, which promotes the survival of cultured DA neurons with a higher potency than GDNF8,9,18. Like GDNF, at least two TGFβ isoforms, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3, are expressed in the target tissues or in the vicinity of the midbrain DA neurons during development19,20. Furthermore, application of a TGFβ blocking antibody to chick embryos leads to a severe loss of DA neurons during development8. Despite these results, the exact role of TGFβ in the development of DA neurons remains poorly characterized. Studies from non-neuronal cells have indicated that the diverse functions of TGFβ largely depend upon the formation of multimeric protein complexes between different subtypes of Smad and their interacting partners, which in turn regulate the transcription of TGFβ target genes21. HIPK2 is a transcriptional cofactor that has been recently shown to directly interact with receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads), including Smad1, Smad2 and Smad3, and that enhances the suppressor functions of Smad1 on activation by bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)22. As Smad2 and Smad3 are primarily activated by TGFβ, however, it is possible that their interaction with HIPK2 may be required for signaling by the TGFβ pathway.

In this study, we provide evidence that TGFβ3 and HIPK2 regulate the survival of DA neurons during PCD. The loss of either TGFβ3 or HIPK2 results in similar deficiencies in the DA neurons, which is due to an increase in apoptosis. As a consequence, Hipk2−/− mutants show a severe psychomotor behavioral phenotype that reflects neuronal deficiencies in the SNpc and VTA. HIPK2’s function depends on its ability to interact with and activate the downstream targets of Smad3. Deletion of the Smad3-interacting domain in HIPK2 completely abolishes the ability of HIPK2 to activate Smad3-dependent gene expression. Taken together, the results from this study provide the first evidence that the TGFβ-HIPK2 signaling mechanism regulates the survival and apoptosis of DA neurons during PCD.

RESULTS

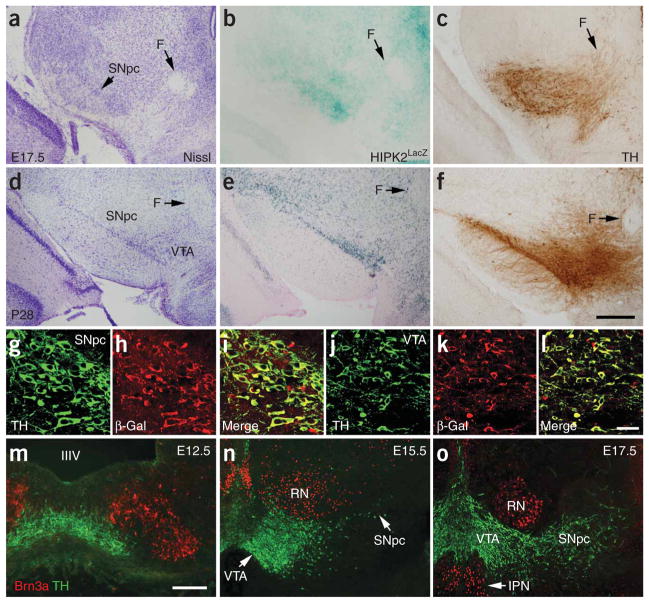

Selective loss of midbrain DA neurons in Hipk2−/− mutants

Using a reporter-gene construct, HIPK2lacZ (ref. 23), which contains the β-galactosidase gene (lacZ), targeted in-frame with the first coding exon of Hipk2, we found that this construct was expressed in the SNpc (A9) and VTA (A10), regions enriched with DA neurons (Fig. 1a–f). The expression of HIPK2lacZ was detected in these two regions as early as E15.5, became more prominent at E17.5 and remained high throughout all of the postnatal stages (Fig. 1d–f). Confocal microscopic analyses showed that essentially all of the DA neurons (marked by TH) in these two areas coexpressed HIPK2lacZ (Fig. 1g–l). In contrast to its expression in the SNpc and VTA, HIPK2lacZ was not detected in the locus ceruleus or in target tissues that are innervated by midbrain DA neurons, such as the striatum, globus pallidus or nucleus accumbens (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Unlike in sensory neurons23, expression of HIPK2 in the DA neurons of the SNpc and VTA did not colocalize with POU domain, class 4, transcription factor 1 (Pou4f1), also known as Brn3a. In fact, Brn3a was detected in a domain dorsolateral to the developing SNpc and VTA at E12.5 and in the red nucleus and interpeduncular nucleus at E15.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 1m–o). Taken together, these results indicate that DA neurons in the SNpc and VTA provide a system with which to investigate HIPK2 functions that are independent of Brn3a.

Figure 1.

Expression of HIPK2 in midbrain DA neurons during development and in postnatal life. (a–f) HIPK2LacZ can be detected in the midbrain DA neurons at E17.5, as seen in b, and at P28, as seen in e. Adjacent brain sections are stained with Nissl or antibody to TH to highlight the location of the SNpc and VTA. The P28 brain section shows the level at Bregma −2.9. F indicates fornix. Scale bar, 250 μm. (g–l) Confocal images showing colocalization of TH and β-galactosidase in the SNpc, seen in panels g–i, and VTA, seen in panels j–l, at P28. Scale bar, 20 μm. (m–o) Immunofluorescence staining in the ventral mesencephalon of an E12.5 embryo shows that Brn3a expression is present adjacent to, but not overlapping with, DA neurons, as seen in panel m. As development progresses, Brn3a expression becomes more restricted to the red nucleus (RN) and the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN), but not in the SNpc or VTA. Scale bar, 250 μm.

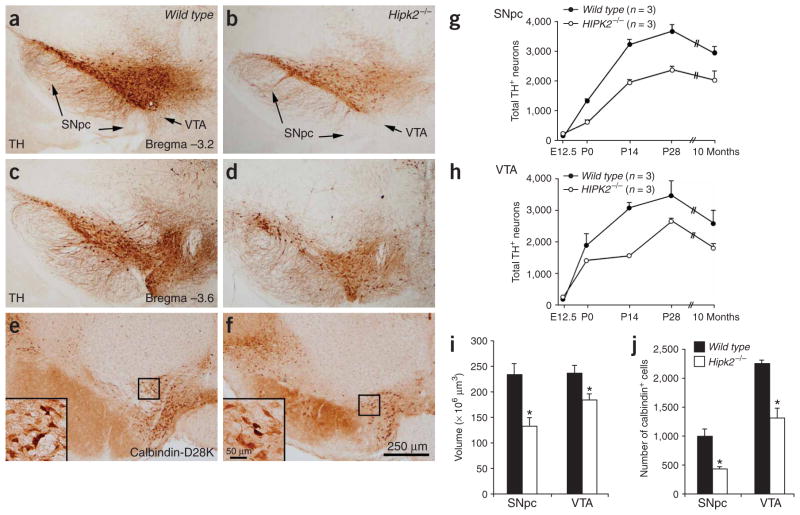

To determine whether the loss of HIPK2 affected the development of midbrain DA neurons, we analyzed the cellular and volumetric contents of the SNpc and VTA by stereology. Consistent with previous reports3, we found that the number of DA neurons in the SNpc and VTA in wild-type mice increased progressively during embryogenesis, reaching its maximum at P14, with a slight decrease in older mice (Fig. 2). Although the number of midbrain DA neurons in wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants seemed to be similar at E12.5, a substantial reduction was detected in Hipk2−/− mutants as early as P0 and persisted into adulthood (Fig. 2b,d,g,h). Specifically, a 40% loss of DA neurons was detected in the SNpc of Hipk2−/− mutants throughout the postnatal stages, whereas the VTA showed a more pronounced deficit at P14, followed by a slight increase in the number of DA neurons at P28 (Fig. 2g,h). The loss of DA neurons in Hipk2−/− mutants seemed to involve the entire SNpc and VTA (Fig. 2a,c and b,d, respectively). Consistent with the substantial loss of neurons, we observed a reduction of 43% and 32% in the volumes of the SNpc and VTA of the Hipk2−/− mutants, respectively, and a 20% reduction in striatal dopamine content, by HPLC (Fig. 2i and data not shown). The calbindin-D28K–expressing DA neurons, which are relatively spared in Parkinson’s disease24, were also reduced, by 57% and 42% in the SNpc and VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants at P28, respectively (Fig. 2e,f, j). In contrast to the DA neuron deficiencies seen in the SNpc and VTA, there was no detectable loss of GABAergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars reticularis (Supplementary Fig. 2 online).

Figure 2.

Loss of DA neurons in the SNpc and VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants. (a–d) Both the SNpc and VTA show a substantial reduction in the density of DA neurons at P28. The deficiency appears to be quite uniform throughout the SNpc and VTA and shows no regional predilection. Images in panels a and b were taken at the level of Bregma −3.2, whereas those in panels c and d were taken at Bregma −3.6. (e,f) The calbindin-D28K–expressing neurons in the SNpc and VTA also show substantial reductions in Hipk2−/− mutants at P28. Scale bar: 250 μm. (g,h) The DA neuron deficiencies in the SNpc and VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants are determined using unbiased stereology methods during development and in postnatal brains. The counts of the DA neurons at E12.5 represent the entire pool of TH+ neurons in the ventral mesencephalon. (i) The volumes of the SNpc and VTA are reduced in Hipk2−/− mutants. (j) The number of calbindin-D28K–positive neurons shows a 57% and 43% reduction in the SNpc and VTA, respectively. Student’s t-test, n = 3 for each genotype. * indicates P = 0.005 for SNpc and 0.006 for VTA.

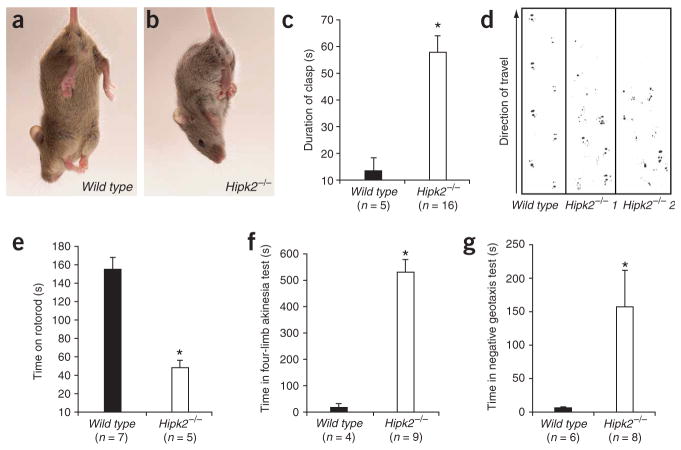

Psychomotor behavioral abnormalities in Hipk2−/− mutants

Perturbations of dopamine transmission resulting from deletion of the Th gene, blockade of dopamine re-uptake or neurotoxin treatment have been shown to produce psychomotor behavioral abnormalities25,26. Given the substantial loss of DA neurons in Hipk2−/− mutants, we performed a battery of tests to evaluate behavioral correlates of nigrostriatal function. We found that the majority of Hipk2−/− mice showed dystonia, characterized by the clasping of hindlimbs when mice were suspended by their tails (Fig. 3a,b). In a 2-min test, >85% of Hipk2−/− mutants showed significantly longer durations of clasping compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 3c; P = 0.001). In addition, Hipk2−/− mutants had a shuffling gait, characterized by a reduced gait width and a consistent failure to finish the tandem walk compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 3d). The distance between the hind paws was substantially reduced in Hipk2−/− mutants, similar to that observed in MPTP-induced neurotoxicity27. We observed that Hipk2−/− mutants showed poor motor coordination on the Rotorod test (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, Hipk2−/− mutants showed severe retardation in the initiation of voluntary movement in four-limb akinesia and negative geotaxis tests (Fig. 3f,g).

Figure 3.

Motor behavioral abnormalities in Hipk2−/− mutants. (a–c) The majority of Hipk2−/− mutants showed hindlimb clasping when suspended by their tails. In a 2-min test, Hipk2−/− mutants spent about 60 s in the clasping position. Student’s t-test, P = 0.001, n = 16 for Hipk2−/− mutants and n = 5 for wild type. (d) Hipk2−/− mutants also had gait abnormalities, including an inability to initiate tandem walk and a severe hesitation during the test. (e) Rotorod test showed that wild-type mice (n = 7) performed significantly better than Hipk2−/− mutants (n = 5). Repeated-measures ANOVA, * indicates P = 0.001. (f,g) For four-limb akinesia tests, as seen in panel f, mice were placed on a brightly lit table and the amount of time taken for the mice to move all four limbs was recorded (n = 4, wild type and n = 9, Hipk2−/−). In the negative geotaxis test, seen in g, mice were placed head-down on a platform tilted at 60° and the time for the mice to turn around and move up toward the top was recorded (n = 6, wild type and n = 8, Hipk2−/− mutants)25. Under both tests, Hipk2−/− mutants performed significantly worse than wild type mice. One-way ANOVA, * indicates P = 0.001, f, and P = 0.038, g.

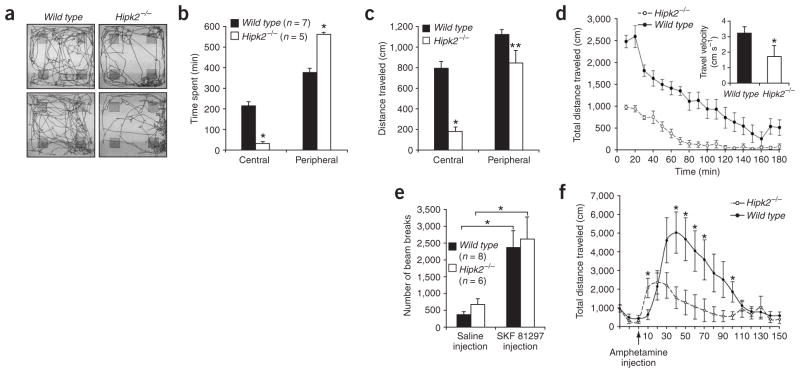

In addition to the dystonia and impaired coordination, Hipk2−/− mutants showed reduced responses to novelty compared with wild-type mice. In contrast to the active exploratory behaviors of wild-type mice, Hipk2−/− mutants showed reduced locomotion when placed in an unfamiliar environment. To quantify the difference, we used an open-field apparatus to measure novelty-related locomotion in wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants. Compared with controls, Hipk2−/− mutants traveled a smaller total distance, entered the center of the field less frequently and spent more time in the periphery (Fig. 4a,b). As a result, the distance of travel by Hipk2−/− mutants was markedly reduced in the central portion of the test field, but only modestly affected in the peripheral areas (Fig. 4c). The total distance traveled was significantly reduced in Hipk2−/− mutants (P = 0.003), whereas their average travel velocity was only modestly reduced (Fig. 4d). After 5 d of acclimation, however, wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants showed no detectable difference in baseline motor activity (data not shown). Notably, treatment with the dopamine type 1 (D1) receptor agonist SKF 81297 increased similar home cage activity in wild-type and Hipk2−/− mice, whereas injection with saline caused no difference in motor activity (Fig. 4e). These results suggested that the function of the postsynaptic D1 receptor remained intact in the absence of HIPK2. To determine whether the loss of mesencephalic DA neurons and the reduction of DA in the striatum of Hipk2−/− mutants affect responses to psychomimetic stimulants, we injected wild-type mice and Hipk2−/− mutants with amphetamine, which inhibits DA reuptake and induces DA efflux at nerve terminals. Locomotor activity was monitored in the open field apparatus for 150 min. Hipk2−/− mutants showed a substantially diminished response to amphetamine, whereas wild-type mice showed a marked increase in locomotor activity (Fig. 4f).

Figure 4.

Reduced response to unfamiliar environment and to amphetamine challenge in Hipk2−/− mutants. (a) Although wild-type mice covered the entire territory in open-field test cages, Hipk2−/− mutants tended to stay in corners and rarely crossed the center. Representative locomotive activity paths from two wild-type mice and two Hipk2−/− mutants are presented. (b,c) Compared with wild type, Hipk2−/− mutants spent less time in the central portion of the field and more time in the periphery (b). The distance traveled in the central portion of the open field is reduced in Hipk2−/− mutants (c). Multivariant ANOVA test, n = 7 for wild type and n = 5 for Hipk2−/− mutants. *P = 0.013; **P = 0.32. (d) The total distance traveled was reduced in Hipk2−/− mutants in the first 3 h of recording (20,367.46 ± 6,557 cm in wild type versus 5,337.22 ± 830 cm in Hipk2−/− mutants). ANOVA test, P = 0.003, n = 7 for wild type and n = 5 for Hipk2−/− mutants. A trend for travel velocity to be reduced in Hipk2−/− mutants is depicted in the inset, P = 0.06. (e) Wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants showed no difference in motor activity after acclimation to test cages (data not shown). Injection with D1 agonist SKF 81297 increased overall activity in wild-type (n = 8) and Hipk2−/− (n = 6) mice. Cumulative beam breaks over 90 min from initial injection of vehicle (left) and SKF 81297 (right) are shown on the y axis. * indicates that the total beam breaks after SKF 81297 administration are significantly different from vehicle controls by two-way ANOVA (F1,24 = 24.08, P < 0.001). (f) Compared to wild-type mice, Hipk2−/− mutants showed reduced motor activity after amphetamine injection. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of genotype versus time; F14, 196 = 4.70, P < 0.0001; * indicates significant difference at the given time points, P < 0.05, n = 8 for each genotype.

Loss of HIPK2 increases apoptosis in DA neurons during PCD

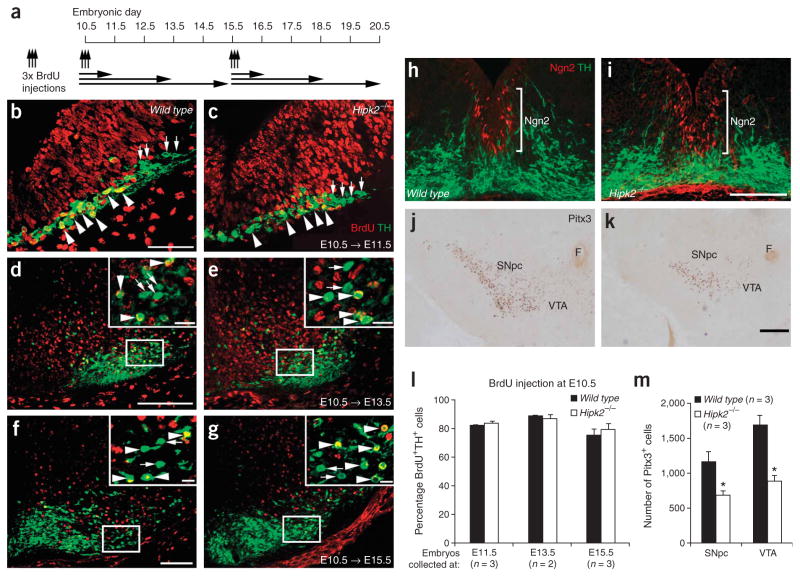

The timing and magnitude of DA neuron loss in the SNpc and VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants suggest that such deficits could result from either impaired neurogenesis or increased cell death during development (Fig. 2g,h). The absence of any detectable difference in the number of DA neurons in the SNpc or VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants at E12.5, however, suggests that loss of HIPK2 most likely did not affect the generation of DA neurons during the early stages (Fig. 2g,h). To further examine the effect of HIPK2 loss, we designed neuronal birth-dating experiments to determine whether the initial stages in the neurogenesis of DA neurons were affected in Hipk2−/− mutants. In the first experimental scheme, we pulse-labeled pregnant dams with BrdU at E10.5, collected the embryos at E11.5, E13.5 and E15.5, and counted the numbers of DA neurons (Fig. 5a). Our results indicated that, in wild-type mice, the percentages of TH+BrdU+ neurons, which represents the nascent DA neurons generated within the chase periods, were 82%, 89% and 76% at E11.5, E13.5 and E15.5, respectively (Fig. 5b,d,f,l). Notably, there was no detectable difference between the wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 5b–g,l). We used a second protocol, with injections of BrdU at E15.5, to examine the later phase of neurogenesis. Under this condition, however, no TH+BrdU+ neurons were detected at E16.5, E18.5 or P0 in the wild type or Hipk2−/− mutants (data not shown). The lack of colabeling may be due to a prolonged cell cycle in the progenitor cells, which may have exceeded the detection time frame. To further study the role of HIPK2 in the neurogenesis and differentiation of DA neurons, we examined the expression of several DA neuron–specific markers, including nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 (Nurr1), paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 3 (Pitx3), neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) and DA transporter (DAT), at various stages during development and in postnatal life. Our results showed no reduction in the expression of these markers in DA neurons of Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 5h–k and Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Using Pitx3 as an independent marker, we found that the number of Pitx3+ cells in the SNpc and VTA at P0 were reduced by 42% and 48%, respectively, similar to what was determined using TH as marker (Fig. 5m and Fig. 2g,h).

Figure 5.

Loss of HIPK2 does not affect neurogenesis in DA neurons. (a) Schematic diagram of neuronal birth-dating experiments. To examine the early phases of neurogenesis, we pulse-labeled pregnant dams with 3 BrdU injections at E10.5 or E15.5 and embryos were collected 1, 3 or 5 d after injection. (b–g) Double immunofluorescence for BrdU (red) and TH (green) shows no difference between the total number of DA neurons and the percentage of DA neurons that have incorporated BrdU at E11.5, E13.5 and E15.5. Insets in panels d to g are higher magnifications of the enlarged areas. Arrowheads indicate TH+BrdU+ neurons and arrows indicate TH+BrdU− neurons. Scale bar, 50 μm (b,c), 100 μm (d–g), 12.5 μm (insets in d–g. (h,i) Double immunofluorescence of Ngn2 (red) and TH+ neurons (green) at E12.5 shows no detectable difference between wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants. Scale bar, 50 μm. (j,k) The expression of Pitx3 shows no detectable reduction in the number of in Hipk2−/− DA neurons at P0, although the density of Pitx3+ cells is reduced. Scale bar, 250 μm. (l) The percentage of TH+BrdU+ neurons shows no difference between wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants. (m) Quantification of Pitx3+ neurons shows a 42% and 48% reduction in the SNpc (P = 0.018) and VTA (P = 0.002) of Hipk2−/− mutants at P0, respectively. Student’s t-test, n = 3 for each genotype.

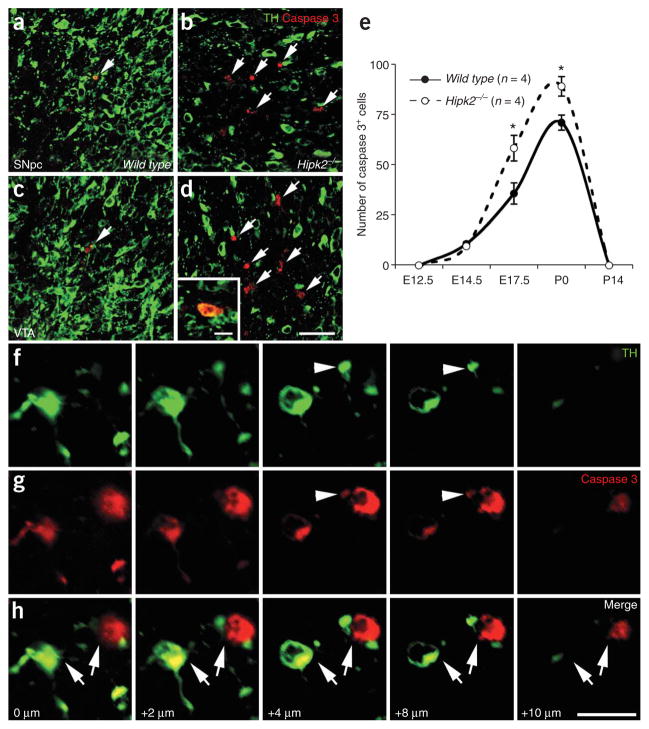

To examine whether the loss of DA neurons in Hipk2−/− mutants results from an increase of cell death during development, we used activated caspase 3 as a marker to determine the extent of PCD in Hipk2−/− mutants3. Consistent with previous results, we found that apoptosis in wild-type mice reached its peak in both the SNpc and VTA at E17.5 and P0 (Fig. 6). Although the extent of apoptosis in DA neurons was similar between wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants at E12.5 and E14.5, it was significantly higher (P <0.05) in Hipk2−/− mutants at E17.5 and P0 (Fig. 6b,d,e, arrows). After P0, there was no detectable cell death in the SNpc or VTA in the postnatal brains of wild-type mice and Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 6e). Many of the apoptotic cells in Hipk2−/− mutants seemed to lack immunoreactivity for TH at lower magnifications, with only a few showing colabeling for activated caspase 3 and TH (Fig. 6b,d). To determine whether the lack of colabeling was due to the different subcellular localization of activated caspase 3 and TH, we used a series of confocal images taken at incremental 2-μm intervals in the z positions, which showed partial or extensive colabeling of caspase 3 and TH in several apoptotic DA neurons of Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 6f,h). Similarly, DA neurons also showed coexpression of caspase 3 with another DA neuron marker, Nurr1 (Supplementary Fig. 4 online). The increase of apoptosis in the SNpc and VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants at E17.5 and P0 coincided with the reduction of DA neurons at similar stages and supports the notion that the loss of HIPK2 leads to an increase in cell death in midbrain DA neurons.

Figure 6.

Loss of HIPK2 leads to increased apoptosis of DA neurons during periods of PCD. (a–d) Immunofluorescence microscopy shows an increase in apoptotic cell death, highlighted by the activated caspase 3 antibody (red), in the SNpc and VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants. The presence of DA neurons is marked by a TH antibody (in green). (e) Quantification of activated caspase 3–positive cells in the SNpc and VTA highlights the window of PCD of DA neuron in wild-type mice at E17.5 and P0. A significant increase of caspase 3–positive cells is noted in Hipk2−/− mutants at the peak of PCD. Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, n = 4 for wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants. (f–h) A series of confocal images, taken at incremental 2-μm intervals in the z positions to demonstrate the colocalization of caspase 3 and TH in 2 apoptotic neurons in the VTA of Hipk2−/− mutants (arrows). Although the neuron on the left shows extensive colabeling of caspase 3 and TH, only partial colocalization is present in the neuron on the right (arrowhead). Scale bar, 20 μm in h.

HIPK2 cooperates with R-Smads to regulate TGFβ targets

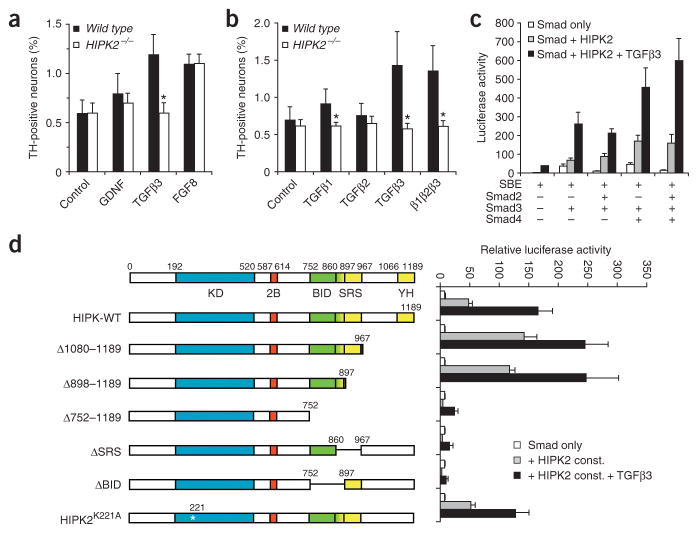

The identification of HIPK2 as a direct interacting partner with receptor-activated Smads led us to hypothesize that HIPK2 is an essential component of the TGFβ-mediated signaling pathways that support the survival of DA neurons. To test this hypothesis, we cultured DA neurons from the ventral mesencephalon of E13.5 wild-type and Hipk2−/− mutant embryos. Our goal was to determine whether the loss of HIPK2 led to a compromise in the survival of neurons cultured in certain trophic factors. Similar to published results8,18, we found that both TGFβ3 and FGF8 were robust survival signals for wild-type DA neurons in vitro, whereas the effect of GDNF was modest (Fig. 7a). Notably, although DA neurons from Hipk2−/− mutants survived in the presence of FGF8 and GDNF, they failed to survive in the presence of TGFβ3 (Fig. 7a). To further investigate whether the loss of HIPK2 led to selective defects in the responses to different subtypes of TGFβ, we cultured wild-type and Hipk2−/− DA neurons with TGFβ1, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3. We found that TGFβ3 was the most effective of the three at promoting the survival of wild-type DA neurons, whereas TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 had a very modest or no obvious effect, respectively (Fig. 7b). The presence of all three TGFβs did not provide an additive or synergistic effect for promoting the survival of the wild-type neurons, nor did they restore the survival of DA neurons from Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7.

HIPK2 is important in the TGFβ-Smad signaling pathway. (a) DA neurons from the ventral mesencephalon of E13.5 embryos are cultured in the defined medium. DA neurons lacking HIPK2 fail to survive in the presence of TGFβ3, but survive in the presence of FGF8 or GDNF. (b) Among the three TGFβ isoforms, TGFβ3 shows the most potent effect in supporting cultured DA neurons, whereas TGFβ1 shows a very modest effect and TGFβ2 has no detectable effect. Statistical analyses for panels a and b use Student’s t-test, n = 4 for wild-type and n = 5 for Hipk2−/− mutants. * indicates P < 0.05.

(c) HIPK2 enhances the ability of R-Smads, especially Smad3, to activate luciferase reporter SBE in HEK293 cells. The coactivator effect of HIPK2 is further enhanced by TGFβ3 (5 ng ml−1). (d) Deletion of the Brn3a-interaction domain (ΔBID), speckle-retention domain or both (Δ752–1189) completely abolishes the coactivator effect of HIPK2 in SBE luciferase assays in HEK293 cells. In contrast, loss of the co-repressor domain in the C-terminus (Δ1080–1189 or Δ898–1189) leads to a slight increase in the SBE activity. Point mutation of the conserved lysine residue in the ATP binding pocket, HIPK2K221A, does not affect the activity of HIPK2 in SBE luciferase assays. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments.

Previous results have shown that HIPK2 directly interacts with R-Smads, including Smad2 and Samd3, which raises the possibility that such interactions may be required for TGFβ3-mediated survival in DA neurons22. To test this, we first determined the function of HIPK2 in the downstream signaling pathways of TGFβ in HEK293 cells using a reporter construct, SBE-luc, that contains multiple Smad binding elements upstream of the firefly luciferase gene28. We found that HIPK2 synergized with R-Smad to activate SBE-luc. HIPK2-induced activation of SBE-luc was most pronounced in assays using Smad3 alone or when Smad3 was used in combination with Smad2 or Smad4 (Fig. 7c). This effect was further enhanced by TGFβ3 (Fig. 7c).

The Smad-interacting domain in HIPK2 has been mapped to the region between amino acids 635 and 867, which also contained interaction domains for homeodomain proteins, such as Brn3a and NK3 (refs. 22,23,29). To identify the region(s) in HIPK2 required to activate SBE, we performed a series of deletions from the C-terminus of HIPK2. Our results showed that the deletion of amino acids 1080–1189 (Δ1080–1189) or amino acids 898–1189 (Δ898–1189) did not affect the ability of HIPK2 to activate SBE. In contrast, these two mutants showed slightly higher activities in SBE luciferase assays (Fig. 7d). These results were consistent with the findings that sequences between amino acids 976 and 1189 can recruit transcriptional co-repressors, such as CtBP (G. Wei and E.J.H., unpublished data). Therefore, removing these sequences increased the coactivator effect of HIPK2. Further deletion of the C-terminal half of the Smad-interacting domain at amino acid 752 (Δ752–1189) completely abolished the ability of HIPK2 to activate SBE (Fig. 7d). As the Brn3a-interacting domain (amino acids 752–897) in HIPK2 contains the C-terminal half of the Smad-interacting domain, we reasoned that deletion of the Brn3a-interacting domain might affect the interaction with Smad. Consistent with this prediction, deleting the Brn3a-interacting domain (ΔBID) completely abolished the coactivator activity of HIPK2 (Fig. 7d). Notably, deleting the speckle-retaining sequence also abolished the activity of HIPK2, probably by preventing HIPK2 localization to the nuclear body30. In contrast, inactivation of the kinase activity of HIPK2 by altering the highly conserved lysine residue in the ATP-binding pocket (HIPK2K221A) did not alter the effect of HIPK2, suggesting that the kinase activity of HIPK2 may not be necessary for its function as a coactivator (Fig. 7d).

DA neuron deficiencies in Tgfβ3−/− mutants

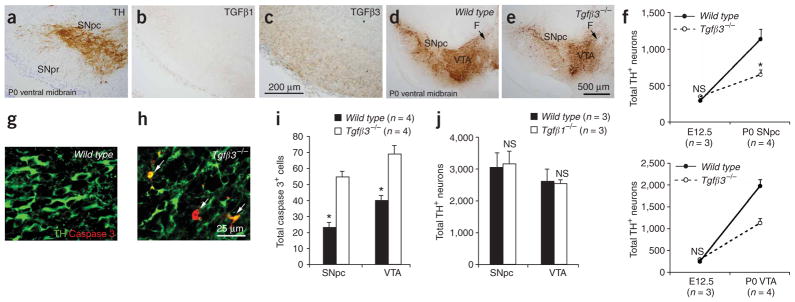

The distinctive effect of TGFβ3 on DA neuron survival suggests that TGFβ3 may also provide pro-survival signals to DA neurons during PCD in vivo. Therefore, on the basis of the proposed function of HIPK2, one would predict that the removal of TGFβ3 should result in a phenotype similar to that observed in Hipk2−/− mutants. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the expression of TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 in the ventral mesencephalon during the periods of PCD. Using isoform-specific antibodies, we found that TGFβ3 was expressed at a high concentration in regions that are adjacent to DA neurons (Fig. 8a–c). In contrast, immunoreactivity for TGFβ1 was barely detectable (Fig. 8b). We then examined the extent of apoptosis and cell loss in the midbrain DA neurons of mice lacking TGFβ1 or TGFβ3. Mice with the targeted deletion of Tgfβ3 were maintained in the same genetic background as Hipk2−/− mutants (C57B6; 129SvJ). Tgfβ3−/− mutants undergo perinatal lethality because of craniofacial defects31,32, limiting our analyses of DA neuron deficiencies to prenatal and perinatal stages. Analyses of DA neurons showed that, similarly to what occurs in Hipk2−/− mutants, the loss of TGFβ3 did not affect the total number of midbrain DA neurons at E12.5, but it led to a 40–50% reduction in the number of DA neurons in the SNpc and VTA at P0 (Fig. 8d–f). The number of DA neurons in the SNpc and VTA of Tgfβ3−/− mutants was almost identical to those in Hipk2−/− mutants at P0 (Fig. 8f and Fig. 2g,h). Corresponding to the neuronal deficiencies, a twofold increase in activated caspase 3–positive neurons was identified in the SNpc and VTA of Tgfβ3−/− mutants at the same stages (Fig. 8g–i).

Figure 8.

Loss of TGFβ3, but not TGFβ1, leads to DA neuron deficiencies similar to those in Hipk2−/− mutants. (a–c) Immunohistochemistry shows that TGFβ1 is undetectable in the ventral mesencephalon at P0 (b). In contrast, a relatively high concentration of TGFβ3(c) is present in regions adjacent to DA neurons in the SNpc (a). (d,e) Reduction of DA neuron density is present in the SNpc and VTA of Tgfβ3−/− mutants at P0. Scale bar, 500 μm. (f) Quantification of DA neurons in wild-type and Tgfβ3−/− mutants shows no difference at E12.5, but does show a 50% reduction in both the SNpc and VTA at P0. * indicates two-tailed Student’s t-test, P = 0.018 for SNpc and P = 0.002 for VTA, n = 3 for E12.5 and n = 4 for P0. (g,h) Increased apoptotic cell death is present in the SNpc and VTA in Tgfβ3−/− mutants at P0. Confocal images of double immunofluorescence using activated caspase 3 (red) and TH (green). Arrows indicate double positive cells. Scale bar, 25 μm. (i) Quantification of DA neurons and activated caspase 3–positive cells in the SNpc and VTA of Tgfβ3−/− mutants shows deficits similar to those in Hipk2−/− at the same stage. (j) No detectable loss of DA neurons is found in the SNpc or VTA of Tgfβ1−/− mutants at P28. NS indicates not significant, two-tailed Student’s t-test, n = 3 for each genotype.

Unlike the Tgfβ3−/− mutants, mice with a targeted deletion of Tgfβ1 showed no gross abnormalities at birth and, in the NIH-Olac genetic background, survived more than 1 month after birth, but suffered from auto-immune disorders and neurodegeneration in the cortical neurons33–35. The differences in genetic background between the Tgfβ1−/− and Hipk2−/− mutants did not affect the number of DA neurons (Supplementary Table 1 online). Notably, Tgfβ1−/− mutants showed no detectable reduction in the number of DA neurons in the SNpc or VTA at 4 weeks of age (Fig. 8j). Taken together, these results are consistent with the selective effect of TGFβ isoforms in supporting the survival of DA neurons in vitro (Fig. 7). The marked similarity of the DA neuron deficiencies between Tgfβ3−/− and Hipk2−/− mutants support the notion that signaling mechanisms involving TGFβ3 and the Smad-interacting transcriptional cofactor HIPK2 are required for the survival of DA neurons.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we present evidence that TGFβ3 and the transcriptional cofactor HIPK2 are essential for the survival of midbrain DA neurons. Our results indicate that both Hipk2−/− and Tgfβ3−/− mutants show a substantial loss of DA neurons that is due to increased apoptosis during PCD. The prominent psychomotor behavioral abnormalities in Hipk2−/− mutants are consistent with those described in mouse mutants lacking TH in DA neurons25,26. Injection with amphetamine, which induces DA efflux from nerve terminals, produced markedly reduced locomotor activity in Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 4f). In contrast, treatment with the D1 receptor agonist SKF 81297 restored locomotor activity in Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 4e). Taken together, these results support the notion that the motor phenotypes in Hipk2−/− mutants are due primarily to deficiencies in the number of DA neurons, whereas postsynaptic D1 receptor function remains intact.

Despite the similarity of DA neuron deficiencies between Hipk2−/− and Ngn2−/− mutants36,37, the mechanisms by which HIPK2 and Ngn2 regulate the development of DA neurons are quite different. In contrast to the severe impairment of neurogenesis observed in Ngn2−/− mutants from E11.5 to E14.5, the loss of HIPK2 does not affect the number of DA neurons at E12.5 (Fig. 2). In addition, the expression of several cell fate and differentiation markers for DA neurons, including Nurr1, Pitx3, Ngn2 and DA transporter (DAT), was not detectably reduced in Hipk2−/− mutants (Fig. 5h–k and Supplementary Fig. 3). Furthermore, detailed neuronal birth-dating experiments also did not show any difference in neurogenesis between wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants during embryogenesis (Fig. 5a–g). BrdU injections at E15.5 fail to label any BrdU+TH+ neurons at E16.5, E18.5 and P0. These results are consistent with a previous report that progenitors in the SNpc have limited potential to differentiate into DA neurons38. It is possible that these progenitors may have prolonged cell cycles after E15.5. Alternatively, the neurogenesis of DA neurons after E15.5 may involve a longer maturation process. Regardless of the exact mechanism, the loss of HIPK2 has no detectable effect on the neurogenesis of DA neurons. In contrast, the timing and the magnitude of apoptosis in DA neurons of Hipk2−/− mutants during PCD, and the selective failure of Hipk2−/− DA neurons to survive in TGFβ3, support the hypothesis that HIPK2 is an important component in the TGFβ signaling pathway that regulates the survival of DA neurons (Supplementary Fig. 5 online).

The manner by which TGFβ controls neuronal survival or apoptosis is cell type dependent. For instance, TGFβ promotes the survival of midbrain DA neurons in dissociated cultures, and blocking TGFβ signaling with neutralizing antibody in chick embryos8,9 or through the targeted deletion of Tgfβ3 or Hipk2 in mouse (Figs. 2, 5 and 7) leads to similar reductions in the number of DA neurons. Notably, the deficiencies in the number of DA neurons of treated chick embryos occur after the induction of DA neurons, suggesting that these particularly sensitive stages may correspond to the periods of PCD identified in rodents3. In contrast to its effects on DA neurons, a reduction of TGFβ signals produces a robust reduction in neuronal apoptosis in sensory neurons during PCD39. Consistent with these results, the targeted deletion of Hipk2 results in reduced apoptosis and increased neuron number in the trigeminal ganglion during PCD23. The phenotypes observed in the sensory ganglion and midbrain DA neurons of Hipk2−/− mutants are consistent with the function of TGFβ in these neurons and further support the notion that the signaling mechanisms involving TGFβ and HIPK2 are cell type specific.

Two lines of evidence further indicate that HIPK2 is an essential element in the downstream signaling pathway of TGFβ. First, DA neurons lacking HIPK2 fail to survive in the presence of TGFβ, but not in the presence of other trophic factors (Fig. 7). Second, HIPK2 directly interacts with R-Smads22, including Smad2 and Smad3, suggesting that HIPK2 can modulate the signaling pathways of TGFβ. Finally, we show that HIPK2 enhances the ability of Smad3 to activate the SBE luciferase construct. The presence of TGFβ further promotes the coactivator effect of HIPK2 (Fig. 7c). Conversely, deletion of the Smad-interacting domain completely abolishes the ability of HIPK2 to promote the activity of Smad3 (Fig. 7d). Taken together, these results suggest that the interactions between HIPK2 and R-Smads are essential for DA neurons to respond to the survival cues of TGFβ. Although it is tempting to propose that the interactions between HIPK2 and R-Smads in the ‘canonical’ TGFβ signaling pathway are essential for the pro-survival function of TGFβ (Fig. 6e), HIPK2 may regulate the survival of DA neurons through Smad-independent mechanisms. For instance, HIPK2 has been implicated in the p53-induced apoptotic pathway by the activation of p53 phosphorylation40,41. In addition, recent evidence has shown that the p53-mediated activation of caspase 6 can further activate HIPK2 (ref. 42). Our results, however, indicate that in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), a more sensitive system for p53 function, loss of HIPK2 has essentially no negative impact on p53 phosphorylation (G. Wei and E.J.H., unpublished data).

Our results in Figure 7 and results from several previous studies indicate that TGFβ is a more potent pro-survival factor than GDNF8,9,18. Among the three isoforms of TGFβ, TGFβ3 seems to be the most efficacious in supporting DA neuron survival (Fig. 7). TGFβ3 is expressed at a relatively high concentration in regions close to DA neurons in the SNpc (Fig. 8) and therefore may provide local survival cues for these neurons at perinatal stages. In contrast, TGFβ1 expression is barely detectable in the ventral midbrain and its loss has no negative impact on the survival of DA neurons (Fig. 8b,j). These results, together with recent studies33, suggest that TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 are required for the survival of cortical and DA neurons, respectively. Notably, a recent paper suggests that TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 are both required for the proper development of DA neurons43. Thus, it remains unclear as to why cultured DA neurons respond less favorably to TGFβ1 and TGFβ2. Several explanations could account for this discrepancy. First, different TGFβ isoforms may have distinct post-translational modifications, which may affect their efficacy and potency in vitro. Second, isoform-specific receptor subtypes or co-receptors may be required for full activation by different TGFβs. The expression of these receptors may be cell type specific or disrupted by the culture conditions for DA neurons. Finally, TGFβ isoforms may have stage-dependent effects on the proliferation, survival and differentiation of DA neurons.

In addition to their pro-survival functions, TGFβ signaling mechanisms have also been implicated in the regulation of synaptic plasticity. In the synapses of Aplysia californica sensory-motor neurons, TGFβ1 is necessary and sufficient for the induction of long-term facilitation and, on acute application, activates MAP kinase and synapsin phosphorylation44,45. Furthermore, genetic analyses in Drosophila melanogaster provide direct evidence that mutations in BMP homolog gbb (glass bottom boat) and BMP receptors tkv (thickveins), sax (saxophone) and wit (wishful thinking) lead to a marked reduction in synaptic size, aberrant synaptic ultrastructure and decreased synaptic transmission46–49. In light of these results, it is interesting to note that, although Hipk2−/− mutants still retain about 50–60% of the DA neurons in the SNpc and VTA, they show marked motor deficits and reduced locomotor responses to amphetamine (Fig. 3). These results suggest that TGFβ signaling mechanisms involving Smad and HIPK2 may also regulate synaptic transmission in DA neurons.

In summary, we have identified HIPK2 as a transcriptional coactivator in the TGFβ signaling pathway that regulates the survival of midbrain DA neurons during PCD. Our results indicate that interaction with Smad3 is essential for HIPK2 function and that the loss of HIPK2 or TGFβ3 results in similar robust neuronal deficits in ventral midbrain DA neurons. These results suggest that the TGFβ-HIPK2 signaling pathway may serve as a potential therapeutic target for promoting the survival of DA neurons.

METHODS

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Detailed methods for histology, immunohistochemistry and luciferase assays can be found in the Supplementary Methods online.

Stereology

The total numbers of TH+ neurons in the SNpc and VTA were determined in wild type and Hipk2−/− mutants using the optical fractionator, an unbiased cell counting method that is not affected by either the volume of reference (for example, the SNpc or VTA) or the size of the counted elements (for example, neurons). Neuronal counts were performed by using a computer-assisted image analysis system consisting of an Olympus BX-51 microscope equipped with a XYZ computer-controlled motorized stage and the Stereo-Investigator software (Microbrightfield). TH-stained neurons were counted in the left SNpc or VTA of every sixth section throughout the entire SNpc. Each section was viewed at lower power (4×) and outlined. The numbers of TH-stained cells were counted at high power (100×oil; NA 1.4) using a 50- × 50-μm counting frame. For P28 and P14 mice, a 15-μm dissector was placed 2 μm below the surface of the section. For embryos and P0 mice, a 10-μm dissector was placed 1.5 μm below the surface of sections. Because tissues at E12.5 were cut thinner, a fractionator method was employed in counting TH+ neurons, where only cell profiles were counted, and is considered as an estimate of cell population. The counts of DA neurons at E12.5 represented the entire pool of TH+ neurons in the ventral mesencephalon.

Measurements of locomotor activity

Mice (n = 5 for Hipk2−/− mutants, n = 7 wild type) were housed individually in photobeam activity cages (40 × 20 × 20 cm, San Diego Instruments) for 48 hrs after they were allowed to habituate in the same room for 7 d. Cages were equipped with 4 infrared photobeams, spaced 8.8 cm apart along the long axis. For the open field test, mice were placed in transparent Plexiglas cages for 10 min and locomotor activity was monitored by video tracking software (Ethovision Tracking Software, Noldus Information Technology) for 5 d. Details of the motor activity tests are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Amphetamine challenge

Mice were habituated to the open field apparatus for 6 d until baseline locomotor activity showed no difference between the genotypes. For each of these days, mice were injected with saline 30 min after placement into the chamber and distance traveled over the ensuring 150 min was recorded. On day 7, 30 min after placement into the chamber, mice were injected with saline or 5 mg per kg (body weight) amphetamine and the distance traveled was monitored for 150 min.

Locomotor response to SKF 81297

Mice were singly housed in low profile cages and placed within standard photobeam frames. Mice had 4 d to acclimatize to their home cages before testing began. On day 5, half of the mouse cohort received an intraperitoneal injection of saline vehicle; the other half received the D1 receptor agonist SKF 81297 (Sigma). The drug was aliquoted to a dosage of 10 mg per kg, delivered in an injection volume of 10 ml g−1. After a further 4 d of acclimatization, all mice were tested a second time. Mice that received vehicle injection on day 5 received SKF 81297 on day 11, and vice versa. No test session effect was observed. All injections occurred between 15:00 and 16:00 on the testing day. Activity data (measured by photobeam breaks) were collected for all mice for 90 min after all injections.

DA neuron cultures

Primary DA neurons were prepared according to published procedures6,8. Briefly, E13.5 mouse embryos were collected from time-pregnant Hipk2+/− females. The ventral mesencephalon was dissected, dissociated after treatment with trypsin and cultured on cover slides coated with poly-D-lysine and laminin. The dissociated cells were cultured in the presence of a mixture of F12, DMEM, N1 additives (Sigma) and designated trophic factors. In general, 2,500 cells were plated on each cover slide and allowed to grow in the presence of GDNF (50 ng ml−1), TGFβ (10 ng ml−1) or FGF8 (1 ng ml−1, R&D Systems). Pilot cultures were established 2 hours after plating to determine the total number TuJ1-positive cells and TH-positive cells. Representative results of such cultures are presented (Supplementary Fig. 6 online).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test (for stereology counting (Figs. 2 and 7), clasping analyses (Fig. 3a), quantification of apoptosis (Figs. 5 and –7) and DA neuron cultures and luciferase assays (Fig. 6) and one-way or two-way ANOVA for behavioral tests (Figs. 3 and 4). Values were expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L.F. Reichardt and S. Pleasure for comments on the manuscript. Special thanks to J. Siegenthaler for TGFβ1 antibody, D.J. Anderson for Ngn2 antibody, R. Akhurst for Tgfβ1 mutants, T. Doestchman for Tgfβ3 mutants, D. Di Monte for dopamine HPLC assays, T. Wyss-Coray for Smads and SBE-luciferase plasmids, A. Buckley for characterizing HIPK2LacZ expression, S. Ku for mutant HIPK2 plasmids, C. Wong for histology and G. Wei for generating Hipk2 mutants. V.P. was supported in part by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Parkinson Disease Association. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS44223 and NS48393), a Pilot Project Grant from the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (AG23501), Veteran’s Administration Merit Review, Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers, National Parkinson Foundation, and The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research to E.J.H., funds from the state of California for medical research on alcohol and drug abuse through UCSF to P.H.J., and grants from the US National Institutes of Health to P.H.J. and L.H.T.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.Z., V.P., A.T.T. and S.T. performed the cellular, molecular and histological experiments and the mouse genetics. L.H.T. supervised and S.J.B. and J.H. performed the Open Field, Rotorod and D1 agonist tests. P.H.J. supervised and J.H. performed the amphetamine tests. J.Z., V.P. and E.J.H. wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENTS

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information is available on the Nature Neuroscience website.

References

- 1.Manji HK, Drevets WC, Charney DS. The cellular neurobiology of depression. Nat Med. 2001;7:541–547. doi: 10.1038/87865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson-Lewis V, et al. Developmental cell death in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra of mice. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:476–488. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000828)424:3<476::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oppenheim RW. Cell death during development of the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:453–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyman C, et al. Overlapping and distinct actions of the neurotrophins BDNF, NT-3, and NT-4/5 on cultured dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons of the ventral mesencephalon. J Neurosci. 1994;14:335–347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00335.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hynes MA, et al. Neurotrophin-4/5 is a survival factor for embryonic midbrain dopaminergic neurons in enriched cultures. J Neurosci Res. 1994;37:144–154. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490370118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin LF, Doherty DH, Lile JD, Bektesh S, Collins F. GDNF: a glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. 1993;260:1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.8493557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farkas LM, Dunker N, Roussa E, Unsicker K, Krieglstein K. Transforming growth factor-beta(s) are essential for the development of midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5178–5186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05178.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poulsen KT, et al. TGF beta 2 and TGF beta 3 are potent survival factors for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Neuron. 1994;13:1245–1252. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. The GDNF family: signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:383–394. doi: 10.1038/nrn812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao MV. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barde YA. Trophic factors and neuronal survival. Neuron. 1989;2:1525–1534. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oo TF, Kholodilov N, Burke RE. Regulation of natural cell death in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra by striatal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5141–5148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05141.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kholodilov N, et al. Regulation of the development of mesencephalic dopaminergic systems by the selective expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in their targets. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3136–3146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4506-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enomoto H, Heuckeroth RO, Golden JP, Johnson EM, Milbrandt J. Development of cranial parasympathetic ganglia requires sequential actions of GDNF and neurturin. Development. 2000;127:4877–4889. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cacalano G, et al. GFRalpha1 is an essential receptor component for GDNF in the developing nervous system and kidney. Neuron. 1998;21:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80514-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enomoto H, et al. GFR alpha1-deficient mice have deficits in the enteric nervous system and kidneys. Neuron. 1998;21:317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieglstein K, Suter-Crazzolara C, Fischer WH, Unsicker K. TGF-beta superfamily members promote survival of midbrain dopaminergic neurons and protect them against MPP+ toxicity. EMBO J. 1995;14:736–742. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flanders KC, et al. Localization and actions of transforming growth factor-beta s in the embryonic nervous system. Development. 1991;113:183–191. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unsicker K, Flanders KC, Cissel DS, Lafyatis R, Sporn MB. Transforming growth factor beta isoforms in the adult rat central and peripheral nervous system. Neuroscience. 1991;44:613–625. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90082-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massague J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harada J, et al. Requirement of the co-repressor homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 for ski-mediated inhibition of bone morphogenetic protein-induced transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38998–39005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiggins AK, et al. Interaction of Brn3a and HIPK2 mediates transcriptional repression of sensory neuron survival. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:257–267. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada T, McGeer PL, Baimbridge KG, McGeer EG. Relative sparing in Parkinson’s disease of substantia nigra dopamine neurons containing calbindin-D28K. Brain Res. 1990;526:303–307. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91236-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou QY, Palmiter RD. Dopamine-deficient mice are severely hypoactive, adipsic, and aphagic. Cell. 1995;83:1197–1209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szczypka MS, et al. Feeding behavior in dopamine-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12138–12143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernagut PO, Diguet E, Labattu B, Tison F. A simple method to measure stride length as an index of nigrostriatal dysfunction in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;113:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin AH, et al. Global analysis of Smad2/3-dependent TGF-beta signaling in living mice reveals prominent tissue-specific responses to injury. J Immunol. 2005;175:547–554. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YH, Choi CY, Lee SJ, Conti MA, Kim Y. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinases, a novel family of co-repressors for homeodomain transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25875–25879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YH, Choi CY, Kim Y. Covalent modification of the homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) by the ubiquitin-like protein SUMO-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12350–12355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaartinen V, et al. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-beta 3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;11:415–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proetzel G, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brionne TC, Tesseur I, Masliah E, Wyss-Coray T. Loss of TGF-beta 1 leads to increased neuronal cell death and microgliosis in mouse brain. Neuron. 2003;40:1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonyadi M, et al. Mapping of a major genetic modifier of embryonic lethality in TGF beta 1 knockout mice. Nat Genet. 1997;15:207–211. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shull MM, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kele J, et al. Neurogenin 2 is required for the development of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Development. 2006;133:495–505. doi: 10.1242/dev.02223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson E, Jensen JB, Parmar M, Guillemot F, Bjorklund A. Development of the mesencephalic dopaminergic neuron system is compromised in the absence of neurogenin 2. Development. 2006;133:507–516. doi: 10.1242/dev.02224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lie DC, et al. The adult substantia nigra contains progenitor cells with neurogenic potential. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6639–6649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06639.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krieglstein K, et al. Reduction of endogenous transforming growth factors beta prevents ontogenetic neuron death. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/80598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann TG, et al. Regulation of p53 activity by its interaction with homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:1–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D’Orazi G, et al. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 phosphorylates p53 at Ser 46 and mediates apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:11–19. doi: 10.1038/ncb714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gresko E, et al. Autoregulatory control of the p53 response by caspase-mediated processing of HIPK2. EMBO J. 2006;25:1883–1894. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roussa E, et al. Transforming growth factor beta is required for differentiation of mouse mesencephalic progenitors into dopaminergic neurons in vitro and in vivo: ectopic induction in dorsal mesencephalon. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2120–2129. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang F, Endo S, Cleary LJ, Eskin A, Byrne JH. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in long-term synaptic facilitation in Aplysia. Science. 1997;275:1318–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chin J, Angers A, Cleary LJ, Eskin A, Byrne JH. Transforming growth factor beta1 alters synapsin distribution and modulates synaptic depression in Aplysia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC220. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-j0004.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rawson JM, Lee M, Kennedy EL, Selleck SB. Drosophila neuromuscular synapse assembly and function require the TGF-beta type I receptor saxophone and the transcription factor Mad. J Neurobiol. 2003;55:134–150. doi: 10.1002/neu.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aberle H, et al. wishful thinking encodes a BMP type II receptor that regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron. 2002;33:545–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCabe BD, et al. Highwire regulates presynaptic BMP signaling essential for synaptic growth. Neuron. 2004;41:891–905. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marques G, et al. The Drosophila BMP type II receptor Wishful Thinking regulates neuromuscular synapse morphology and function. Neuron. 2002;33:529–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.