Abstract

Background

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a common complication after anesthesia and surgery; 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists have been considered as a first-line therapy. Ramosetron and palonosetron are more recently developed drugs and have greater receptor affinity and a longer elimination half-life compared with older 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. The purpose of this study was to determine which drug is more effective for preventing PONV between ramosetron and palonosetron.

Methods

We enrolled 100 patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery into this study. The subjects were divided into ramosetron group and palonosetron group. The medications were provided immediately before the induction of anesthesia. The occurrence of nausea and vomiting, severity of nausea according to a visual analogue scale, and rescue anti-emetic drug use were monitored immediately after the end of surgery and at 0-6 h, 6-24 h, and 24-48 h post-surgery.

Results

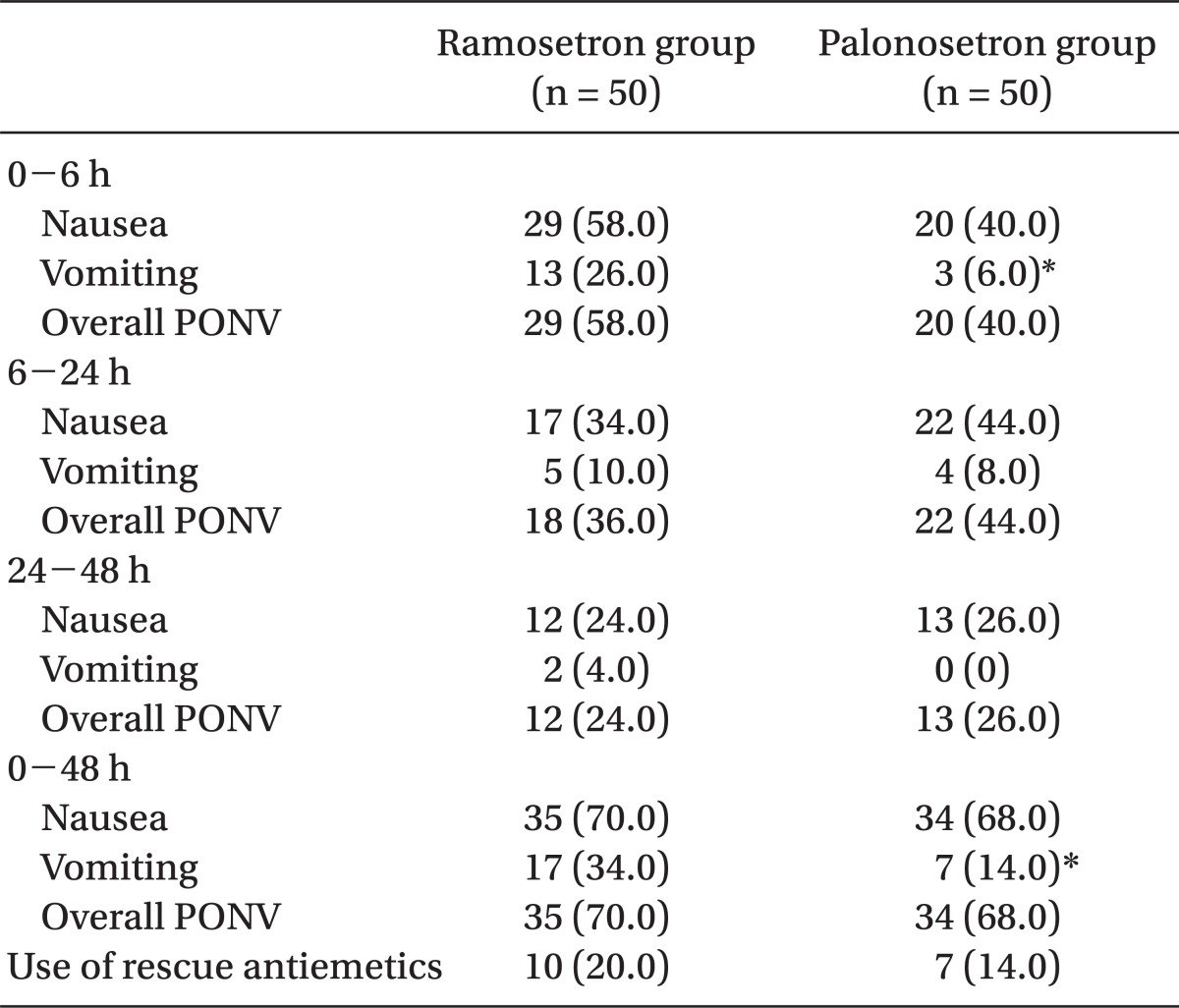

The incidence of vomiting was significantly lower in the palonosetron group than in the ramosetron group during 0-6 h (6% vs 26%, P = 0.012) and 0-48 h (14% vs 34%, P = 0.034). The incidence of nausea and overall PONV, and the use of rescue antiemetic were not significantly different during all time intervals. The severity of nausea was not different between the two groups.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the incidence of PONV between the ramosetron and the palonosetron group have not shown the difference during 0-48 h, although palonosetron results in a lower incidence of vomiting during 0-6 h post-surgery.

Keywords: Palonosetron, PONV, Ramosetron

Introduction

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a common complication after surgery. PONV may increase patient discomfort, disruption of surgical wound, pulmonary aspiration, electrolyte imbalance and dehydration [1]. Many nerves and neurotransmitters are involved in PONV, so prophylaxis and treatment are complex. Different drugs are effective, but only a few have proven reliability [2]. The 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists show similar efficacy to droperidol or dexamethasone [3]. In addition to their efficacy for PONV prevention, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists do not produce undesirable adverse effects, such as dry mouth, extra pyramidal symptoms, dysphoria, or excessive sedation. Hence, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have been considered a first-line therapy [1,4]. Among 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, ramosetron and palonosetron are more recently developed drugs. They have greater binding affinity for 5-HT3 receptors and a longer elimination half-life than the older 5-HT3 receptor antagonists [5]. Of note, the most recently-developed palonosetron has far stronger receptor affinity and a longer half-life than other drugs [5]. Many studies have compared different 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for the prevention of PONV. However, no study has evaluated the efficacy of ramosetron and palonosetron in prevention of PONV. Therefore, we designed the present randomized double-blind study to compare the efficacy of ramosetron and palonosetron to prevent PONV after gynecological laparoscopic surgery.

Materials and Methods

Patients who were scheduled to undergo elective gynecological laparoscopic surgery of ≥ 1 h duration between May and August 2011, were enrolled into the study on a random basis. All enrolled patients were ≥ 20 years-old-age with American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status 1 or 2. The study approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and registered with clinicaltrials.gov under #NCT01476280, and all patients provided verbal and written informed consent before enrollment. Patients were excluded if they had received anti-emetics, steroids, or psychoactive medications within 24 h of study enrollment. Patients with vomiting or retching in the 24 h preceding surgery, patients with ongoing vomiting from gastrointestinal disease, and patients who had received emetogenic cancer chemotherapy within 4 weeks or radiotherapy within 8 weeks before study entry were excluded as well.

No patient received pre-anesthetic medications. Patients were randomly assigned to one of 2 prophylactic interventions by a computer generated number table and received a single dose of ramosetron 0.3 mg (ramosetron group) or palonosetron 0.075 mg (palonosetron group) intravenously. Trained nurses, who were blinded to the study, opened the envelopes containing the allocation group before induction of anesthesia, and then prepared study medications diluted to 2 ml. The medications were provided immediately before the induction of anesthesia. Anesthesia was induced with propofol 2 mg/kg and maintained with sevoflurane 1-4% and 2-4 L/min of oxygenair mixture (FiO2 = 0.5). Adjunctive medication to anesthesia like remifentanil was not used. For all patients, tracheal intubation was facilitated with rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg and at the end of surgery, patients received pyridostigmine 0.2 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.008 mg/kg for reversal of neuromuscular blockade. Post-operative pain was controlled using a patientcontrolled analgesia (PCA) device containing 1,000 µg of fentanyl in 100 ml of normal saline and prepared to deliver a 10 µg/h background infusion of fentanyl with a 10 µg bolus, and a lock-out time of 15 min.

The occurrence of nausea and vomiting, severity of nausea according to a visual analogue scale (VAS) (0, none; 10, maximum) and rescue anti-emetic drug use were monitored immediately after the end of surgery and at 0-6 h, 6-24 h, and 24-48 h post-surgery. Nausea was defined as a subjectively unpleasant sensation associated with awareness of the urge to vomit, whereas episodes of vomiting included both vomiting (forceful expulsion of gastric contents from the mouth) and retching (labored, spasmodic, rhythmic contractions of the respiratory muscles without expulsion of gastric contents). Intravenous metoclopramide (10 mg) was permitted as a rescue anti-emetic when vomiting or retching occurred or the patients requested treatment. Details of any adverse effects, including headache, dizziness, constipation, myalgia were recorded and patients were also asked to rate their overall satisfaction on a 3-point scale (satisfied, neutral, and dissatisfied) 48 h after completion of surgery. All subjects were observed and interviewed by doctors unaware of the study drug.

Sample size was calculated by a power analysis, while designing the study. Allowing an α error of 5% and a β error of 20%; it was estimated that a minimum of 49 patients per group would be required to show a 30% difference (from 60% to 42%) in the incidence of PONV [6,7]. Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney rank sum test were used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. A difference was regarded as significant at a P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS® statistical package version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows®.

Results

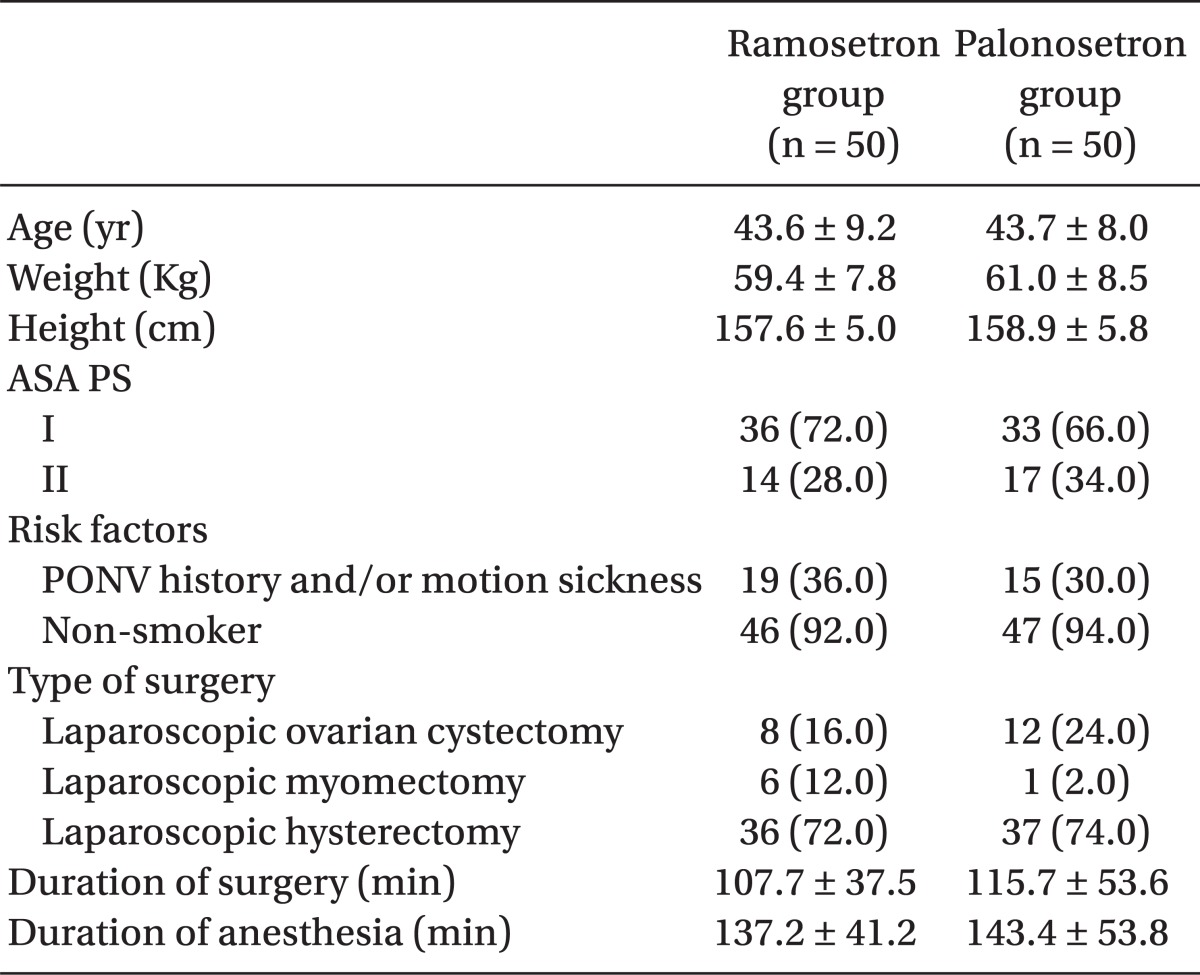

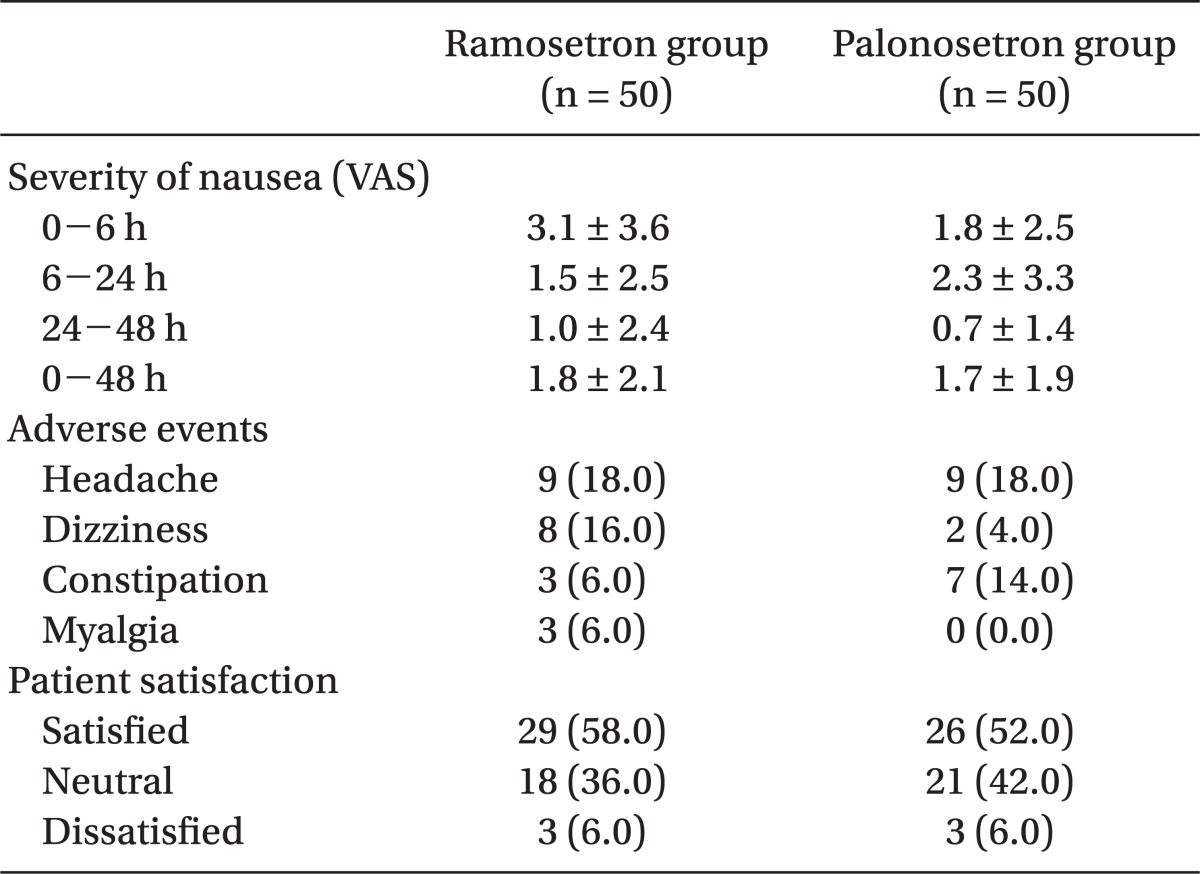

One hundred patients were recruited, all of whom completed the study. The patients' characteristics, risk factors, and operative data were not significantly different between the 2 groups (Table 1). The incidence of vomiting was significantly lower in the palonosetron group than in the ramosetron group at the following time points: 0-6 h (6% vs 26%, P = 0.012) and 0-48 h (14% vs 34%, P = 0.034) (Table 2). The incidence of nausea and overall PONV, and the use of rescue antiemetic was not statistically different during all time intervals (Table 2). The severity of nausea (VAS), incidence of adverse effects, and patient satisfaction ratings were not different between the 2 groups (Table 3).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Operative Data

Data are presented as number of patients (%) or means ± SD. ASA PS: the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Physical Status classification, PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Table 2.

Incidence of PONV

Data are presented as number of patients (%). PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting. *P < 0.05 compared with ramosetron group.

Table 3.

Severity of Nausea, Adverse Events and Patient Satisfaction

Data are presented as number of patients (%) or means ± SD. VAS: visual analogue scale.

Discussion

Emetic response in PONV is very complex and is triggered by multiple inputs that arrive from areas, such as the higher cortical centers, cerebellum, vestibular apparatus, glossopharyngeal and vagal afferent nerve. A variety of neurotransmitter and receptor systems including histaminergic, cholinergic, dopaminergic, neurokininergic and serotonergic mediate these signals. Peripheral 5-HT3 receptors are in vagal terminals linked to the vomiting center, and competitive 5-HT3 antagonists can block initiation of the vomiting reflex at these sites [1]. Selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have a well established role in the prophylaxis and treatment of PONV. They have greater efficacy, as well as a better safety and side-effect profile compared with traditional antiemetic agents [8].

Ramosetron is a relatively recent drug and has a longer and more potent efficacy than previously developed 5-HT3 antagonists [9]. There are several reports that ramosetron was as effective as or more effective than the older 5-HT3 receptor for the prevention of PONV during 0-24 h after anesthesia [10]. Furthermore, the antiemetic effect of ramosetron can last up to 48 h [11]. The differences in effectiveness between the older 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and ramosetron may be related to the longer elimination half life (5.8 ± 1.2 h) and higher receptor affinity (pKi = 8.5) of ramosetron [1,5].

Palonosetron is the latest 5-HT3 antagonist. Its unique properties have led to it being described as the first of a second generation of 5-HT3 antagonists. Palonosetron shows avid binding to the 5-HT3 receptor, with a pKi of 10.4, which far exceeds the other 5-HT3 antagonists [5]; palonosetron has the longest elimination half-life with 40 h [8].

The possible mechanisms of palonosetron and ramosetron for preventing PONV are similar, but palonosetron is further differentiated from other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists including ramosetron, by interacting with the receptors in an allosteric and positively cooperative manner [12]. Furthermore, palonosetron may promote internalization of the 5-HT3 receptor and decrease the function of the receptor [13]. The collective data led to the hypothesis that palonosetron would have stronger and longer lasting antiemetic effect compared with ramosetron. In our study, palonosetron was statistically more effective than ramosetron in preventing vomiting during the first 0-6 h and 0-48 h post-surgery. It has been known that the anti-vomiting effect of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists is greater than the anti-nausea effect [5], but there has been no direct examination comparing the efficacy of ramosetron and palonosetron inspecifically curbing vomiting or nausea. A few previous comparative studies of palonosetron with ondansetron or granisetron have yielded different results, with the anti-vomiting effect of palonosetron being similar to granisetron and superior to ondansetron [14,15].

As mentioned above, we expected that palonosetron would have a stronger and longer-lasting effect. However, we could not detect a statistical significant difference during 6-48 h; indeed, there was a trend towards a lower incidence of PONV in the ramosetron group during that time, in spite of its known shorter elimination half-life and weaker binding affinity compared with palonosetron. It would be necessary to clarify the reasons or situations that produced the disagreement between biological properties and clinical effects of ramosetron and palonosetron. It has been established that an equal dose of 0.3 mg ramosetron is effective for prevention or treatment for CINV and PONV [16]. For palonosetron, the recommended initial treatment dose for CINV is 0.25 mg and the minimum effective dose for PONV is 0.075 mg [5,17,18]. However, Tang et al. [19] reported that 30 µg/kg of palonosetron is the effective dose in reducing postoperative vomiting. In addition, a post-marketing surveillance reported tolerable adverse events at a higher dose of palonosetron in prophylaxis for CINV [20]. Therefore, we think that studies are necessary to determine the efficacy and safety of higher doses of palonosetron in the prevention of PONV.

The risk of PONV is associated with various factors that include age, sex, smoking status, prior history of PONV or motion sickness, postoperative opioid use, anesthesia technique, type and duration of surgery, and others [1]. These factors were well-balanced between the 2 groups in this study. All enrolled patients were female and were anticipated to use PCA devices containing opioid. Most were nonsmokers and some had a history of PONV or motion sickness. Thus, the majority had at least 3 risk factors, corresponding to more than a 60% risk for PONV, according to the simplified risk score of Apfel [1]. We suggest that for this reason, the present study still showed a high incidence of PONV after prophylaxis with ramosetron or palonosetron (70.0% and 68.0%, respectively, during the 0-48 h). In addition, the incidence of PONV after laparoscopic surgery has been considered to be high [21].

Patients at moderate or high risk of PONV should receive combination prophylaxis [22]. Thus, careful studies are needed to decide the safety and cost-effectiveness of operative combination therapies using palonosetron. Blitz et al. [23] reported that the combination of palonosetron plus dexamethasone did not significantly reduce the incidence of PONV when compared with palonosetron alone for the first 72 h after laparoscopic surgeries.

Adverse effects of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are not clinically serious; headache and dizziness are most commonly reported [8,17]. No difference was found in the incidence of adverse effects between ramosetron and palonosetron groups in the present study and most side-effects were mild and transient.

A control group was not included in our study because we regarded it as unethical to withhold prophylaxis in these patients at high risk for PONV. Thus, the baseline incidence of PONV was not evaluated. Another limitation is that we compared ramosetron and palonosetron based on the known optimal doses without knowledge of their equipotent doses. The manufacturer's recommended doses of ramosetron and palonosetron are 0.3 and 0.075 mg intravenous respectively, and were chosen for this study. Finally, outcomes were measured during preset time intervals (0-6 h, 6-24 h, 24-48 h and 0-48 h) rather than in a particular setting such as time intervals related to extubation, stay at recovery room, transfer to general wards, ambulation, and diet.

In conclusion, the incidence of PONV between the ramosetron group and the palonosetron group did not demonstrate a difference during the 0-48 h time period, although palonosetron results in a lower incidence of vomiting during 0-6 h post-surgery.

References

- 1.Apfel CC. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. In: Miller RD, editor. Miller's anesthesia. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2010. pp. 2729–2755. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlisle JB, Stevenson CA. Drugs for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004125. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004125.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, et al. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golembiewski J, Chernin E, Chopra T. Prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1247–1260. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.12.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muchatuta NA, Paech MJ. Management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: focus on palonosetron. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:21–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SK, Cho EJ. A randomized, double-blind trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:399–407. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi DK, Chin JH, Lee EH, Lim OB, Chung CH, Ro YJ, et al. Prophylactic control of post-operative nausea and vomiting using ondansetron and ramosetron after cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:962–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho KY, Gan TJ. Pharmacology, pharmacogenetics, and clinical efficacy of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor antagonists for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006;19:606–611. doi: 10.1097/01.aco.0000247340.61815.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabasseda X. Ramosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist for the control of nausea and vomiting. Drugs Today (Barc) 2002;38:75–89. doi: 10.1358/dot.2002.38.2.820104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SI, Kim SC, Baek YH, Ok SY, Kim SH. Comparison of ramosetron with ondansetron for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing gynaecological surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:549–553. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii Y, Tanaka H, Ito M. Ramosetron compared with granisetron for the prevention of vomiting following strabismus surgery in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:670–672. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.6.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Rojas C, Stathis M, Thomas AG, Massuda EB, Alt J, Zhang J, et al. Palonosetron exhibits unique molecular interactions with the 5-HT3 receptor. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:469–478. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fa74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rojas C, Thomas AG, Alt J, Stathis M, Zhang J, Rubenstein EB, et al. Palonosetron triggers 5-HT(3) receptor internalization and causes prolonged inhibition of receptor function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;626:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharjee DP, Dawn S, Nayak S, Roy PR, Acharya A, Dey R. A comparative study between palonosetron and granisetron to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26:480–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bajwa SS, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Sharma V, Singh A, Goraya S, et al. Palonosetron: A novel approach to control postoperative nausea and vomiting in day care surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:19–24. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii Y, Uemura A, Tanaka H. Prophyaxis of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy with ramosetron: randomised controlled trial. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:583–586. doi: 10.1080/11024150201680002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navari RM. Palonosetron: a second generation 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor antagonist. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:1577–1586. doi: 10.1517/17425250903407289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Candiotti KA, Kovac AL, Melson TI, Clerici G, Joo Gan T. A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:445–451. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817b5ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang J, D'Angelo R, White PF, Scuderi PE. The efficacy of RS-25259, a long-acting selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after hysterectomy procedures. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:462–467. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199808000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petru E, Andel J, Angleitner-Boubenizek L, Steger G, Bernhart M, Busch K, et al. Early Austrian multicenter experience with palonosetron as antiemetic treatment for patients undergoing highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158:169–173. doi: 10.1007/s10354-008-0515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leksowski K, Peryga P, Szyca R. Ondansetron, metoclopramid, dexamethason, and their combinations compared for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:878–882. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scuderi PE, James RL, Harris L, Mims GR., 3rd Multimodal antiemetic management prevents early postoperative vomiting after outpatient laparoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1408–1414. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200012000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blitz JD, Haile M, Kline R, Franco L, Didehvar S, Pachter HL, et al. A randomized double blind study to evaluate efficacy of palonosetron with dexamethasone versus palonosetron alone for prevention of postoperative and postdischarge nausea and vomiting in subjects undergoing laparoscopic surgeries with high metogenic risk. Am J Ther. 2012;19:324–329. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e318209dff1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]