Abstract

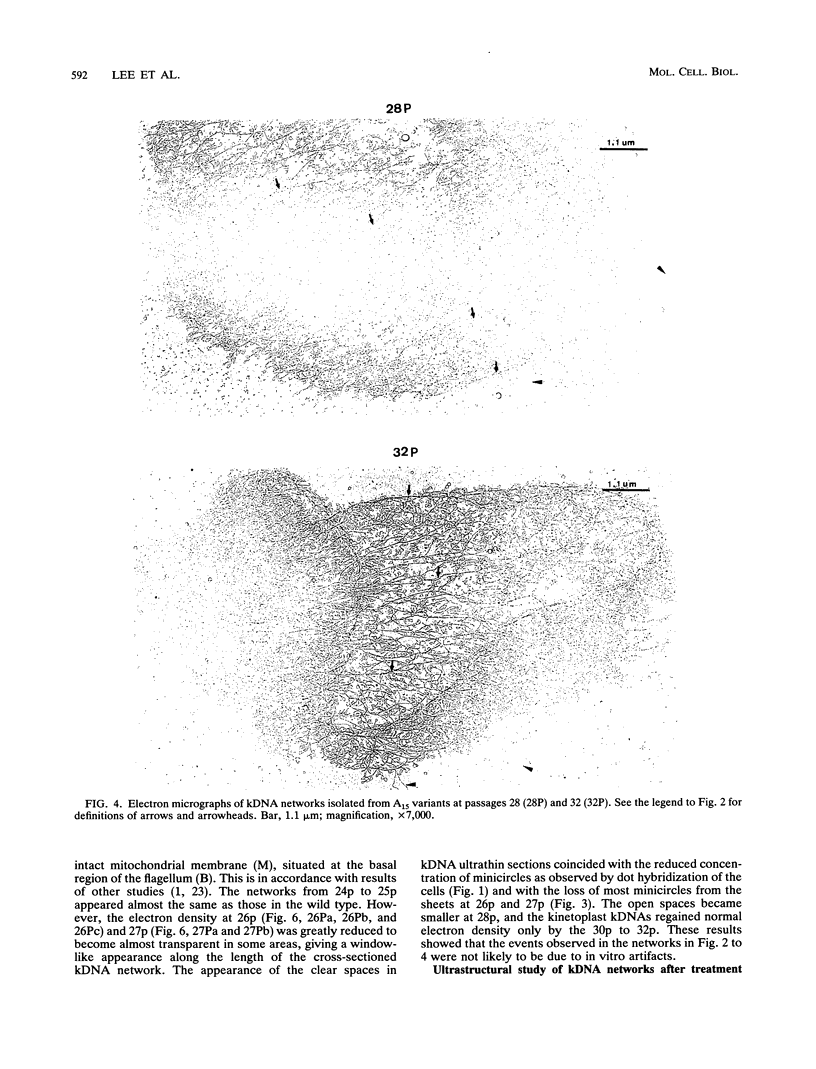

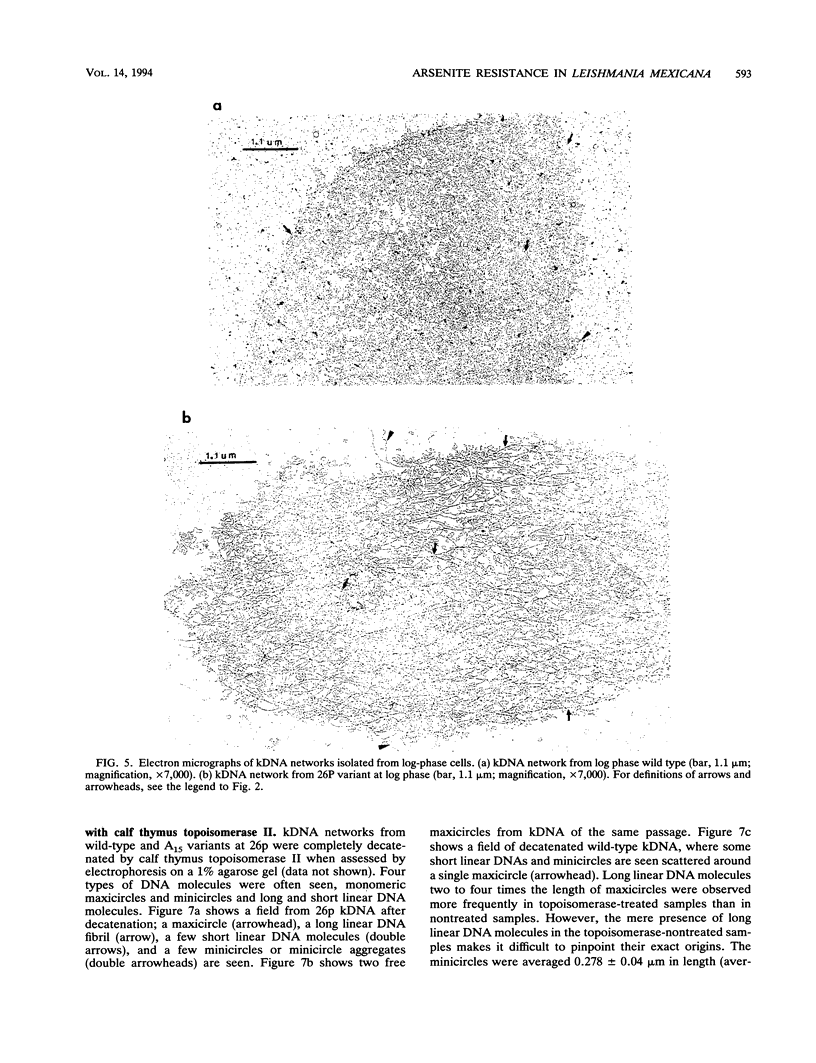

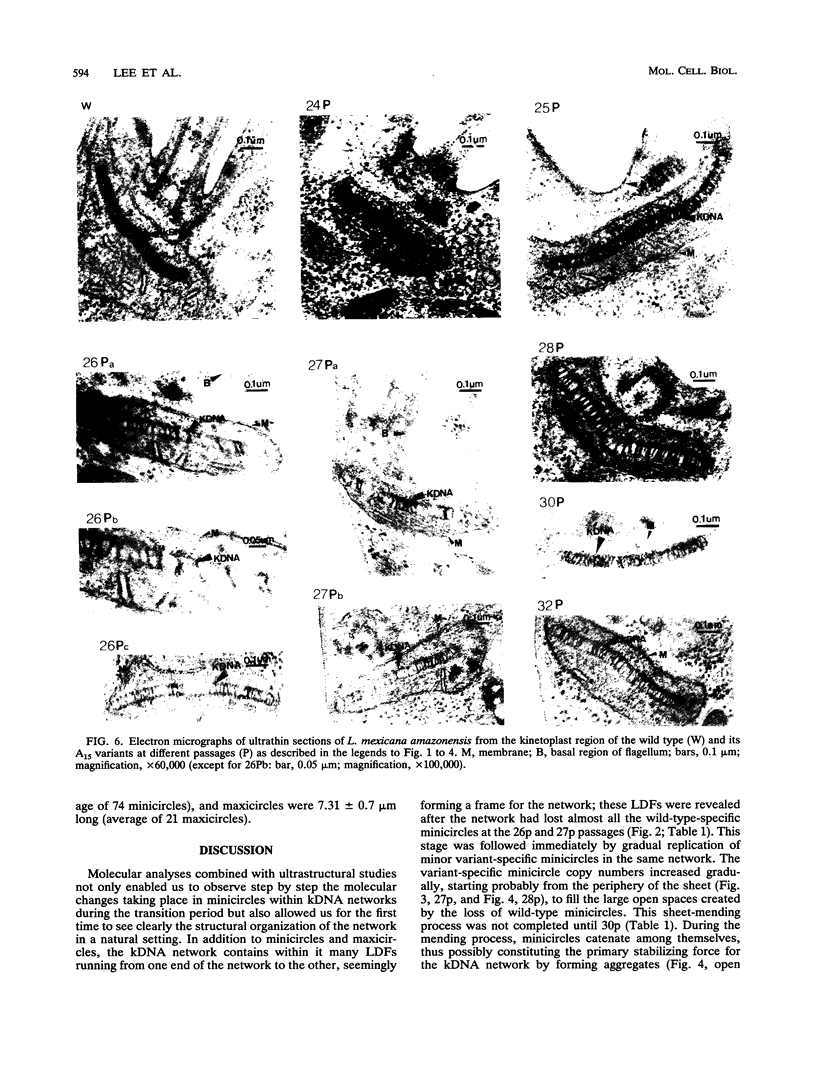

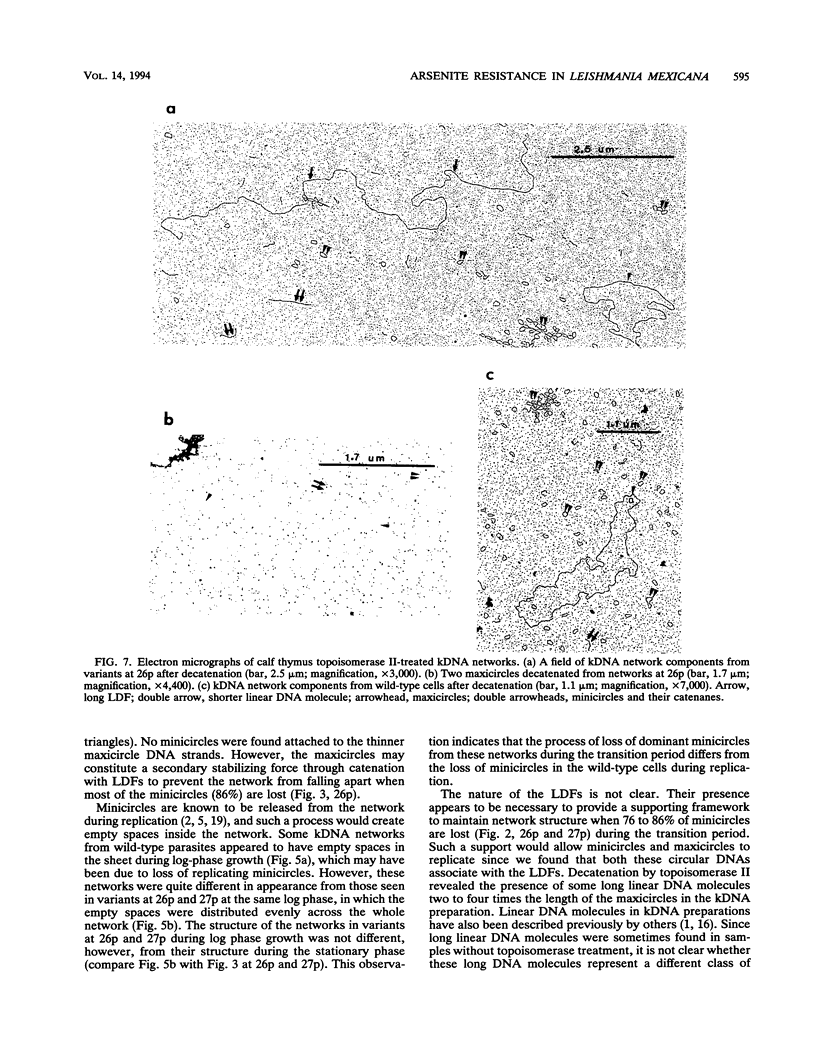

Certain minor minicircle sequence classes in the kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) networks of arsenite- or tunicamycin-resistant Leishmania mexicana amazonensis variants whose nuclear DNA is amplified appear to be preferentially selected to replicate (S. T. Lee, C. Tarn, and K. P. Chang, Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 58:187-204, 1993). These sequences replace the predominant wild-type minicircle sequences to become dominant species in the kDNA network. The switch from wild-type-specific to variant-specific minicircles takes place rapidly within the same network, the period of minicircle dominance changes being defined as the transition period. To investigate the structural organization of the kDNA networks during this transition period, we analyzed kDNA from whole arsenite-resistant Leishmania parasites by dot hybridization with sequence-specific DNA probes and by electron-microscopic examination of isolated kDNA networks in vitro. Both analyses concluded that during the switch of dominance the predominant wild-type minicircle class was rapidly lost and that selective replication of variant-specific minicircles subsequently filled the network step by step. There was a time during the transition when few wild-type- or variant-specific minicircles were present, leaving the network almost empty and exposing a species of thick, long, fibrous DNA which seemed to form a skeleton for the network. Both minicircles and maxicircles were found to attach to these long DNA fibrils. The nature of the long DNA fibrils is not clear, but they may be important in providing a framework for the network structure and a support for the replication of minicircles and maxicircles.

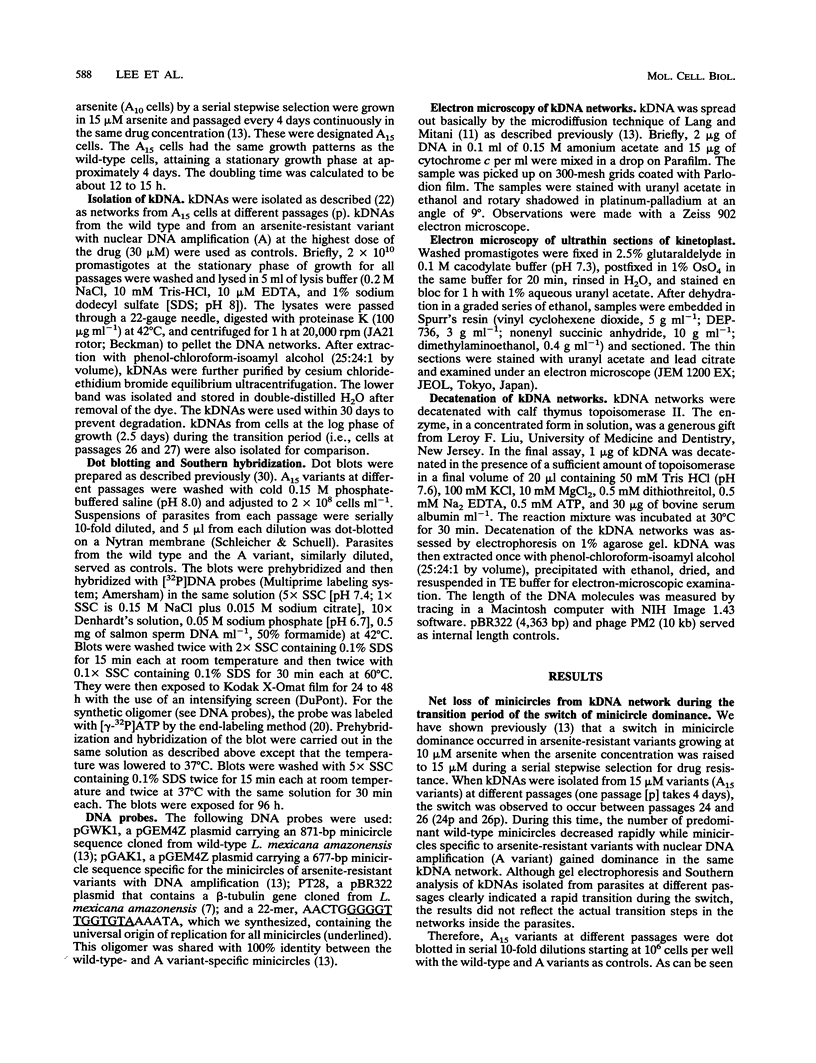

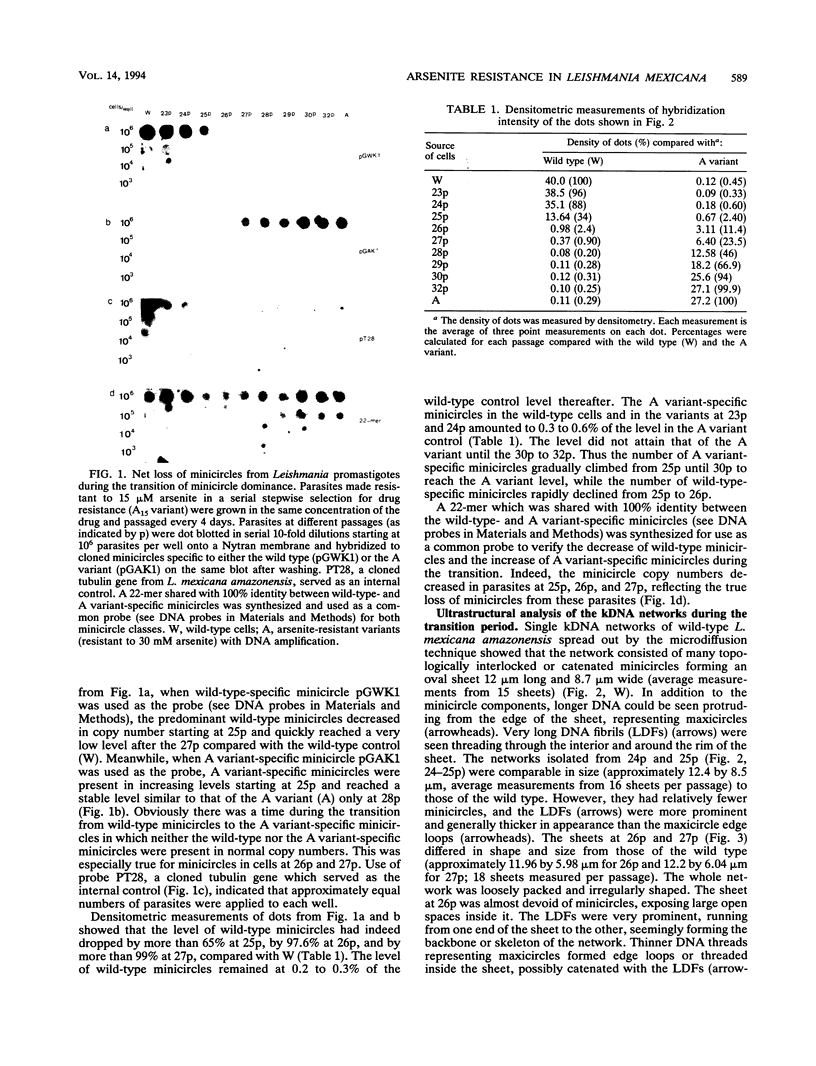

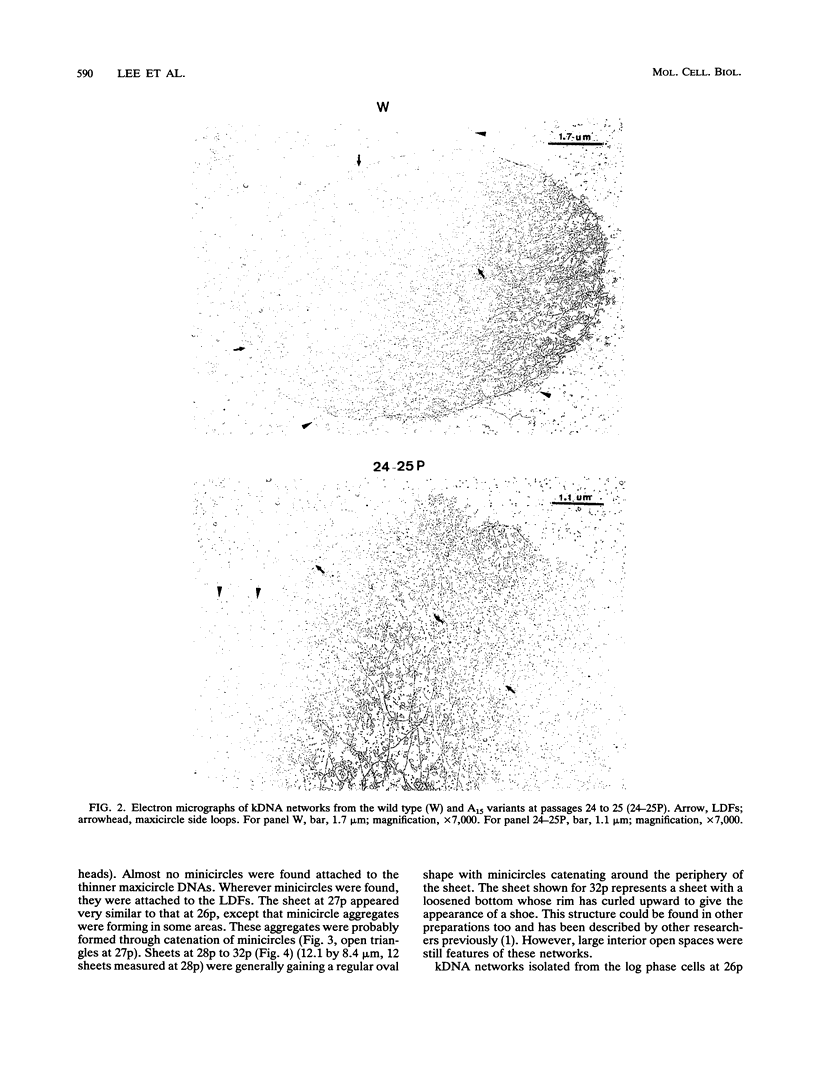

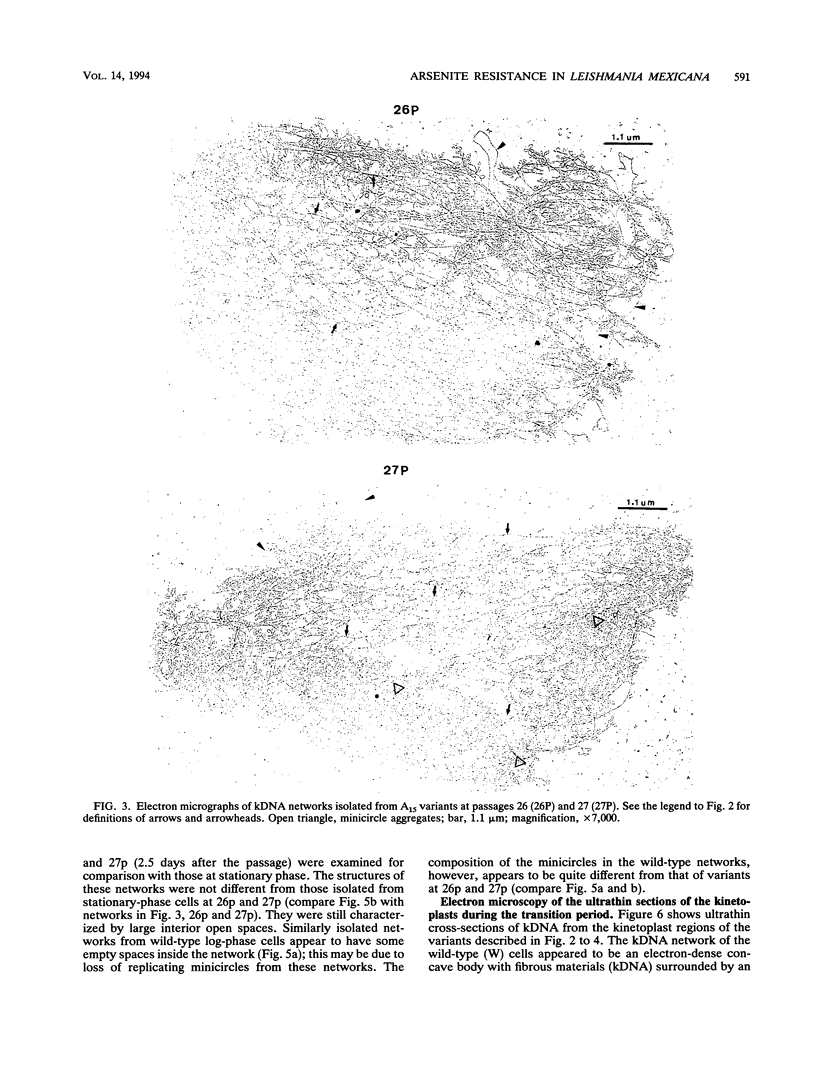

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Birkenmeyer L., Ray D. S. Replication of kinetoplast DNA in isolated kinetoplasts from Crithidia fasciculata. Identification of minicircle DNA replication intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1986 Feb 15;261(5):2362–2368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douc-Rasy S., Kayser A., Riou J. F., Riou G. ATP-independent type II topoisomerase from trypanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Oct;83(19):7152–7156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.19.7152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund P. T. Free minicircles of kinetoplast DNA in Crithidia fasciculata. J Biol Chem. 1979 Jun 10;254(11):4895–4900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlamb A. H., Weislogel P. O., Hoeijmakers J. H., Borst P. Isolation and characterization of kinetoplast DNA from bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. J Cell Biol. 1978 Feb;76(2):293–309. doi: 10.1083/jcb.76.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong D., Lee B. Beta tubulin gene of the parasitic protozoan Leishmania mexicana. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988 Oct;31(1):97–106. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouts D. L., Wolstenholme D. R., Boyer H. W. Heterogeneity in sensitivity to cleavage by the restriction endonucleases ECORI and HindIII of circular kinetoplast DNA molecules of Crithidia acanthocephali. J Cell Biol. 1978 Nov;79(2 Pt 1):329–341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.79.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk S. L., Cosgrove W. B. Kinetoplast DNA from normal and dyskinetoplastic strains of Trypanosoma equiperdum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979 Jan 26;561(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(79)90484-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleisen M. C., Borst P., Weijers P. J. The structure of kinetoplast DNA. 1. The mini-circles of Crithidia lucilae are heterogeneous in base sequence. Eur J Biochem. 1976 Apr 15;64(1):141–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang D., Mitani M. Simplified quantitative electron microscopy of biopolymers. Biopolymers. 1970;9(3):373–379. doi: 10.1002/bip.1970.360090310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent M., Steinert M. Electron microscopy of kinetoplastic DNA from Trypanosoma mega. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970 Jun;66(2):419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.2.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. T., Tarn C., Chang K. P. Characterization of the switch of kinetoplast DNA minicircle dominance during development and reversion of drug resistance in Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993 Apr;58(2):187–203. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90041-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. T., Tarn C., Wang C. Y. Characterization of sequence changes in kinetoplast DNA maxicircles of drug-resistant Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992 Dec;56(2):197–207. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90169-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Y., Lee S. T., Chang K. P. Transkinetoplastidy--a novel phenomenon involving bulk alterations of mitochondrion-kinetoplast DNA of a trypanosomatid protozoan. J Protozool. 1992 Jan-Feb;39(1):190–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1992.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini J. C., Miller K. G., Englund P. T. Decatenation of kinetoplast DNA by topoisomerases. J Biol Chem. 1980 Jun 10;255(11):4976–4979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou G. F., Saucier J. M. Characterization of the molecular components in kinetoplast-mitochondrial DNA of Trypanosoma equiperdum. Comparative study of the dyskinetoplastic and wild strains. J Cell Biol. 1979 Jul;82(1):248–263. doi: 10.1083/jcb.82.1.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou G., Pautrizel R. Isolation and characterization of circular DNA molecules heterogeneous in size from a dyskinetoplastic strain of Trypanosoma equiperdum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977 Dec 21;79(4):1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)91116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K. A., Shapiro T. A., Rauch C. A., Englund P. T. Replication of kinetoplast DNA in trypanosomes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:339–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlomai J., Zadok A. Reversible decatenation of kinetoplast DNA by a DNA topoisomerase from trypanosomatids. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983 Jun 25;11(12):4019–4034. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.12.4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A. M., Simpson L. Isolation and characterization of kinetoplast DNA networks and minicircles from Crithidia fasciculata. J Protozool. 1974 Nov;21(5):774–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1974.tb03751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L., Da Silva A. Isolation and characterization of kinetoplast DNA from Leishmania tarentolae. J Mol Biol. 1971 Mar 28;56(3):443–473. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. Kinetoplast DNA in trypanosomid flagellates. Int Rev Cytol. 1986;99:119–179. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. The mitochondrial genome of kinetoplastid protozoa: genomic organization, transcription, replication, and evolution. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:363–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart K. Kinetoplast DNA, mitochondrial DNA with a difference. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1983 Oct;9(2):93–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(83)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth D. F., Pratt D. M. Rapid identification of Leishmania species by specific hybridization of kinetoplast DNA in cutaneous lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Nov;79(22):6999–7003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.22.6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]