Abstract

Introduction

Describe differences in sexual activity and function in women with and without pelvic floor disorders (PFDs).

Methods

Heterosexual women > 40 years of age who presented to either Urogynecology or general gynecology clinics at 11 clinical sites were recruited. Women were asked if they were sexually active with a male partner. Validated questionnaires and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) examinations assessed urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence (FI) and/or pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Sexual activity and function was measured by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Student’s t-tests were used to assess continuous variables; categorical variables were assessed with Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to assess the impact of PFDs on FSFI total and domain scores.

Results

505 women met eligibility requirements and consent for participation. Women with and without PFDs did not differ in race, BMI, co-morbid medical conditions, or hormone use. Women with PFDs were slightly older than women without PFDs (55.6 + 10.8 vs. 51.6 + 8.3 years, P <0.001); all analyses were controlled for age. Women with PFDs were as likely to be sexually active as women without PFDs (61.6 vs. 75.5%, P=0.09). There was no difference in total FSFI scores between cohorts (23.2 + 8.5 vs. 24.4 + 9.2, P= 0.23) or FSFI domain scores (all p = NS).

Conclusion

Rates of sexual activity and function are not different between women with and without PFDs.

Keywords: anal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, questionnaires, sexual function, urinary incontinence

Introduction

The World Health Organization refers to sexual health as the physical, emotional, mental and social well-being of people in relation to sexuality.1 Pelvic floor disorders, including urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence (FI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), are common and affect up to one third of pre-menopausal and 45% of postmenopausal women.2 Data regarding the effects of PFDs on women’s sexual function is limited and conflicted, with some studies showing no effect on function and others showing a profound effect. The quality of these studies varies significantly, as some use ad- hoc questionnaires, others use condition-specific questionnaires in a general population and nearly all studies exclude women who are not sexually active. 3-5

In order to accurately evaluate the impact of surgery or medical therapies on a woman’s sexual function, baseline data regarding the sexual function and activity status of women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) are needed. The specific aim of this study was to compare rates of sexual activity and sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders to women without PFDs using validated questionnaires.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for all study sites and all participants provided written informed consent. Women with and without PFDs were recruited from specialty urogynecology or general gynecology clinics at 11 sites throughout the United States from September 2007 to April 2009. Women who presented for scheduled visits to general gynecology clinics served as controls for women who presented to urogynecology clinics. Eligible participants included heterosexual women > 40 years of age who were not currently pregnant, did not have a diagnosis of gynecological cancer and had not undergone recent pelvic surgery. Only women who were able to complete the questionnaires in English were included. Both women who reported sexual activity and those who reported that they were sexually inactive were included because one of the aims of the study was to explore whether PFDs affected rates of sexual activity.

Participants completed demographic information as well as validated UI, FI and POP symptom-severity and quality-of-life questionnaires. Patient characteristics collected included age, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, race, parity, hormonal status, martial/relationship status, medications, depression, and other medical co-morbidities. Participants completed the self-administered questionnaires during their office visit. UI was evaluated with the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI). The ISI is a two-question urinary incontinence symptom severity questionnaire. 6 Total scores range from 0-8 (0=dry, 1-2=slight, 3-4=moderate, 6-8=severe). 6 FI was assessed with the Wexner Fecal Incontinence Scale (FIS), which records both the type (gas, mucus, liquid or solid stool) and frequency of anal incontinence symptoms. Scores range from 0-12, with higher scores representing more severe anal incontinence. Prolapse was assessed with Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System All participants also underwent a pelvic examination that included a supine cough stress test for urinary incontinence, evaluation for flatal and fecal incontinence with cough and/or Valsalva, and a Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification Examination (POP-Q)10,11 to document prolapse stage; these exams were conducted by a trained clinician during the scheduled office visit.

For our analyses, UI was defined as a score >1 on the ISI questionnaire or from observation of UI during physical exam. AI was defined as a score ≥1 for the incontinence of liquid or solid stool questions on the FIS or by observation of fecal material on the perineum or loss of fecal material during the physical exam. POP was defined as the leading edge of prolapse > 0 (beyond the hymeneal ring) as measured on POP-Q exam.

Women were asked if they were currently sexually active with a male partner (defined as caressing, foreplay, masturbation and vaginal intercourse within the past 6 months) and if not active, to indicate reasons for sexual inactivity. Participants who were not sexually active could select from the following options: “I do not have a partner”, “I have a partner but my partner is not interested”, “I am not healthy enough to have sex for other medical reasons”, “My partner is not healthy enough to have sex”, “My bladder, bowel or vaginal prolapse problems keep me from having sex” or “other” and write in a comment.

Sexually active women also completed the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a 19- item validated questionnaire used to measure sexual function in women. The FSFI assesses six domains of sexual functioning (sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) and total scores range from 2 to 36 with higher scores indicating better function. 13 Each domain is scored for women who have been sexually active within the last month with a range from lowest score of 0.8 to highest score of 6 (with higher scores indicating better function).

Sample Size

The primary objective of the present analysis was to determine if rates of sexual activity were different between women with and without pelvic floor disorders. In order to detect a 20% difference in rates of sexual activity between women with PFDs and those without, we estimated that a total of 500 study participants were required to provide 80% power with an alpha of 0.05; 200 women with PFDs and 300 women without PFDs would need to be recruited. We recruited more women from gynecology clinics than Urogynecology clinics based on the assumption that 25% of the women presenting to the general gynecology clinics would report pelvic floor dysfunction when questioned.

Participant characteristics associated with sexual activity and function was assessed with student’s t-tests for continuous variables, while categorical variables were assessed with Fisher’s exact test, Chi-square, and logistic regression. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to determine if pelvic floor disorders are associated with sexual inactivity and poorer sexual function while controlling for the potentially confounding effects of specific patient characteristics. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina),

Results

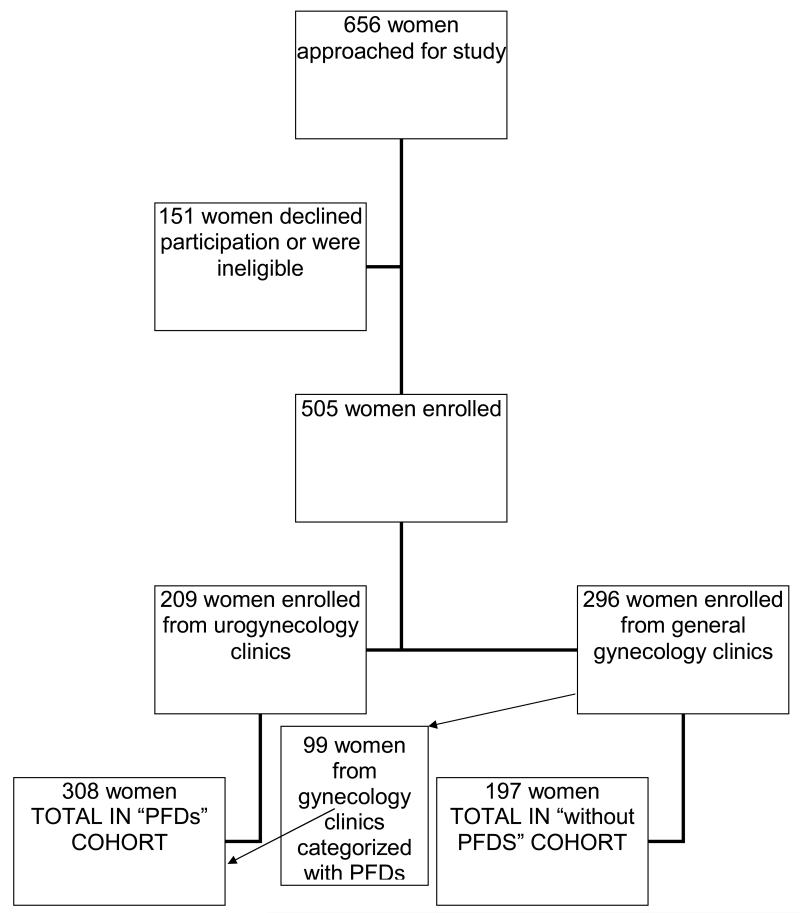

Six hundred and fifty six women were approached for participation in this study; 505 (77%) women met eligibility requirements, enrolled and completed questionnaires. Two hundred and nine of these women were recruited from Urogynecology specialty clinics and 296 were recruited from general gynecology. As anticipated, based on our definitions for UI, FI and POP, 99 (33%) of participants who had presented to general gynecology clinics met our preset criteria for the diagnosis of UI, FI and/or POP. All subsequent analyses included these women in the PFDs cohort (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment diagram

Women with PFDs were significantly older than women without PFDs and had higher parity (Table 1). However, after multivariate logistic regression, only age remained significantly different between groups; all further analyses were controlled for age. Women with and without PFDs did not differ in race, BMI, co-morbid medical conditions, depression, or postmenopausal hormone use. The PFD cohort consisted of 232 (75%) women with UI, 162 (53%) with FI and 92 (30%) with POP; the majority of women in this cohort had 2 or more PFDs (56%). The mean ISI score for the sexually active women with urinary incontinence was 3.5 (classified as moderately severe UI), while the mean FI score on the FIS for this cohort was 3.6. The majority of the participants (62%) with POP had Stage 2 on the POP-Q exam. (Table 2)

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (variables controlled for age)

| Variable | with PFDs n=308(%) |

without PFDs n=197(%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age* | 55.6 ± 10.8 |

51.6 ± 8.3 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| African American | 45(15%) | 47(23%) | |

| White | 222(72%) | 121(62%) | NS |

| Other | 10(3%) | 8(4%) | |

|

| |||

| BMI* | 29.5 ± 8.0 | 27.9 ± 7.0 | NS |

|

| |||

| Parity | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.003 |

|

| |||

| Relationship status | |||

| Single | 90(28%) | 58(31%) | |

| Married/Stable relationship |

217(72%) | 138(69%) | NS |

|

| |||

| Hormone Replacement Therapy(HRT) |

|||

| Menopausal (without HRT) |

41 | 40 | NS |

| Menopausal (with oral or vaginal HRT) |

108 | 106 | |

|

| |||

|

**Co-morbid medical conditions |

99 (47%) | 113 (38%) | NS |

|

| |||

| Depression | 67 (21%) | 28 (14%) | NS |

|

| |||

| Surgical History | |||

| Hysterectomy | 99(32%) | 34(17%) | 0.002 |

| Bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy |

54(17%) | 16(8%) | 0.001 |

|

| |||

| ***Sexual activity rates | Women withPFDs 125(61%) |

Women without PFDs 208(71%) |

0.44 |

Means ± standard deviations (SD)

Co-morbid conditions included Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, Coronary Artery Disease, stroke and multiple sclerosis

when controlled for age

Table 2.

Distribution of Types and combination of PFDs* in the women with PFDs (n= 308)

| Type of PFD | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| UI | 232(75%) |

| AI | 162(53%) |

| POP(beyond hymen) |

92 (30%) |

| POP-Q Stage | |

| 2 | 57(62%) |

| 3 | 35(38%) |

| 4 | 0 |

| Only 1 PFD | 135 (44%) |

| 2 or more PFDs | 172 (56%) |

PFDS were defined by criteria based on the ISI/Wexner questionnaires, cough stress test and POP-Q exam

Seventy-five percent of women without PFDs reported sexual activity with a male partner in the last 6 months versus 61.6% of women with PFDs; rates of sexual activity did not differ between women with and without PFDs when controlled for age (P=0.09). The most common reason cited for sexual inactivity given by both cohorts was the “lack of a partner”; only 6 subjects (<1%) with PFDs reported their “bladder, bowel or vaginal problems” was a reason for sexual inactivity. However, women who were sexually inactive had more severe UI symptoms as measured by the ISI (p=0.002) and more severe FI symptoms as measured by the FIS (0.003). There was no difference in stage of POP between sexually active and inactive women.

Of the 333 women who were sexually active, 327(98.2%) participants completed the FSFI. Total FSFI scores did not differ between women with and without PFDs (23.2 ± 8.5 vs. 24.4 ± 9.2, P= 0.23.) although mean FSFI desire domain scores were lower in women with PFDs than those without (3.1± 1.2 vs. 3.5 ± 1.3, P=0.01). The FSFI arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain domains were not different between groups. (Table 3) There was no association between increasing UI severity, as measured by the ISI, and FSFI total or domain scores. There was an association between increasing FI severity as measured by the FIS and worsening FSFI desire domain scores (p=0.028), but after controlling for age this was no longer significant (p=0.056). There was no association between stage of POP and FSFI total or domain scores.

Table 3.

Female Sexual Function Index Questionnaire*

| FSFI | with PFDS (n = 308) |

without PFDs (n = 197) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 23.2 ± 8.5 | 24.4 ± 9.2 | NS |

| Desire | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0.01 |

| Arousal | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | NS |

| Lubrication | 4.1 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 1.9 | NS |

| Orgasm | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 1.9 | NS |

| Satisfaction | 4.3 ± 1.8 | 4.3 ± 1.9 | NS |

| Pain | 4.0 ± 2.2 | 4.1 ± 2.0 | NS |

Mean FSFI Scores ± SD

Univariate analysis identified the following variables to be significantly different between sexually active and inactive women: age, BMI, relationship status, hormone status, co-morbid medical conditions, UI severity as measured by the ISI, FI severity as measured by the FIS, total vaginal length, prior hysterectomy, and prior incontinence surgery. (Table 4) These variables were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Variables that remained significant predictors of sexual inactivity were increasing age, increasing BMI and being single. The same variables plus maximum stage of prolpase were included in multivariable regression models for FSFI total and domain scores within sexually active women. Increasing age was a significant predictor of worse scores for FSFI total and desire and lubrication domain scores. Relationship status (being single) was a significant predictor of better desire domain scores. In these multivariable models, UI, FI and POP were not significantly associated with sexual inactivity or poorer sexual function.

Discussion

In our large cohort of women with and without pelvic floor dysfunction, we found that sexual activity rates and sexual function scores as measured by a validated questionnaire did not vary between women with and without PFD’s. Data describing the effect of PFDs on women’s sexual function are limited and conflicted. Handa et al studied 495 women with UI and/or POP and showed that UI negatively affected sexual function, while POP did not, however women did not undergo physical exam to document prolapse in this retrospective study.3 In contrast, Barber et al found that prolapse is more likely than UI to result in sexual inactivity and to be perceived as affecting sexual relations, although this study did not use a validated questionnaire and did not compare women with pelvic floor dysfunction to those without.5 Weber et al, compared women with prolapse to a control group and concluded that women with prolapse and/or UI have similar sexual function as women without PFDs, although her analysis did not include data regarding anal incontinence and the data were from a single center.18

The primary objective of this study was to compare rates of sexual activity in women with PFDs to a cohort of women without pelvic floor dysfunction. In addition we assessed sexual function between these two distinct groups of women with a validated general sexual function questionnaire, the FSFI. In this multi-center study, we found that women with PFDs were just as likely to be sexually active as women without PFDs. In addition, among those women who reported that they were sexually active, FSFI total scores were not different between groups. The strongest predictor of both activity and function was age; less than 1% of women reported that their PFD interfered with sexual activity. The only difference between groups was in the desire domain of the FSFI. This difference was small and, as there is no published data on the minimally clinically important difference of the FSFI, we can conjecture that the small difference we observed in a single domain may not be clinically important.

The challenge of comparative studies is to choose the proper control group. We chose to recruit women presenting to general gynecology clinics. Gynecology patients have served as asymptomatic controls in other descriptive urogynecology studies, but to our knowledge, not for studies comparing sexual function between women with and without PFDs.14,15 Based on studies that have shown a high prevalence of undiagnosed PFDs in the general population, we anticipated that approximately 25% of the gynecology patients would also have pelvic floor dysfunction. In actuality, 33% of gynecologic patients met out present criteria for UI, AI and/or POP, based on our strict definitions for pelvic floor disorders. Because our goal was to compare women with and without disorders, we assigned gynecology patients with PFD to the PFD group. Assignment of gynecologic patients with pelvic floor dysfunction to the group of women with PFDs ensured that we had an accurate comparison of two distinct and clearly defined groups.

One of the strengths of this study is that, unlike similar studies, we did not exclude women who were sexually inactive and we were able to ascertain reasons for sexual inactivity.4 In both cohorts, the majority of participants who were not sexually active cited “absence of a partner” as the primary reason for inactivity. Another strength of this study was that we recruited women from throughout the United States, while many other studies reflect only the sexual health of women at a single site or region.3,4,16 We believe that this broad representation makes our findings generalizable to the majority of women who seek care for pelvic floor dysfunction.

Limitations of our study are associated with participant selection and study design. We recruited women over the age of 40 because that is the age of peak incidence of surgery for UI and/or POP, which enabled us to recruit from an enriched sample of symptomatic women, and we assumed that women presenting to gynecology clinics would be younger than women presenting to Urogynecology clinics.17 Despite limiting our recruitment to women over 40, our two groups still differed in age. Secondly, this study was limited to heterosexual women because during the study period because validated measures did not exist to evaluate sexual function in homosexual women.18 In these analyses, we were unable to include women who do not speak English, since the FSFI has not been validated in other languages.

In conclusion, we evaluated sexual activity and sexual function in a large cohort of women with and without PFDs using validated measures for PFDs and sexual function and determined that these disorders did not have a negative impact on sexual activity or function in this population. Ultimately, the information gained from this study and similar areas of research will help further educate healthcare providers about sexual activity and function of the women they manage with and without pelvic floor disorders.

Acknowledgements

Financial support sponsored in part by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Research Committee (Fellows’ Pelvic Research Network) a and the DHHS/NIH/NCRR/GCRC Grant #5M01 RR 00997 (for use of the Biostatistician at the University of New Mexico HSC)

Footnotes

Recruitment Sites

Presented in abstract form as oral presentation at the American Urogynecologic Society Annual Scientific Meeting, Hollywood, FL, September 2009.

References

- 1.Defining Sexual health: report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28-31; January 2002. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers RG, Villarreal A, Kammerer-Doak D, Qualls C. Sexual function in women with and without urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2001;12(6):361–5. doi: 10.1007/s001920170012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Handa VL, Harvey L, Cundiff GW, et al. Sexual function among women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):751–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handa VL, Cundiff G, Chang HH, Helzlsouer KJ. Female sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 May;111(5):1045–52. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816bbe85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barber MD, Visco AG, Wyman JF, et al. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):281–89. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanley J, Capewell S, Hagen S, et al. Validity study of the severity index, a simple measure of urinary incontinence in women. Br Med J. 2001;322:1096–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorge J, Wexner S. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwood T, Church J, Fleshman JW, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: The fecal incontinence severity index. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1525–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Buckwalter JG, Burchette RJ, Nager CW, Luber KM. Epidemiology of prolapse and incontinence questionnaire; validation of a new epidemiologic survey. Int. Urogynecol J Pelvor Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16(4):272–84. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bump RC, Mattiason A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall A, Theofrastous J, Cundiff G, et al. Inter-observer and intra-observer reliability of the proposed International Continence Society of Gynecologic Surgeons and American Urogynecological Society pelvic organ prolapse quantification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1467–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Pelvic Floor Disorders Network Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000 Apr-Jun;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swift SE. The distribution of pelvic organ polapse in a population of women presenting for routine gynecologic healthcare. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:277–85. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boreham MK, Richter H, Kenton K, et al. Anal incontinence in women presenting for gynecologic care: Prevalence, risk factors, and impact upon quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1637–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novi JM, Jeronis S, Morgan MA, Arya LA. Sexual function in women with pelvic organ prolapse compared to women without pelvic organ prolapse. J Urol. 2005 May;173(5):1669–72. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154618.40300.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waetjen LE, Subak LL, Shen H, et al. Stress urinary incontinence surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(4):p671–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)03124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapple C. Multidisciplinary Management of Female Pelvic Floor Disorders. Elsiver; Philadelphia: 2006. pp. 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber AM, Walters MD, Schover LR, Mitchinson A. Sexual function in women with uterovaginal prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:483–7. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00434-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]