Abstract

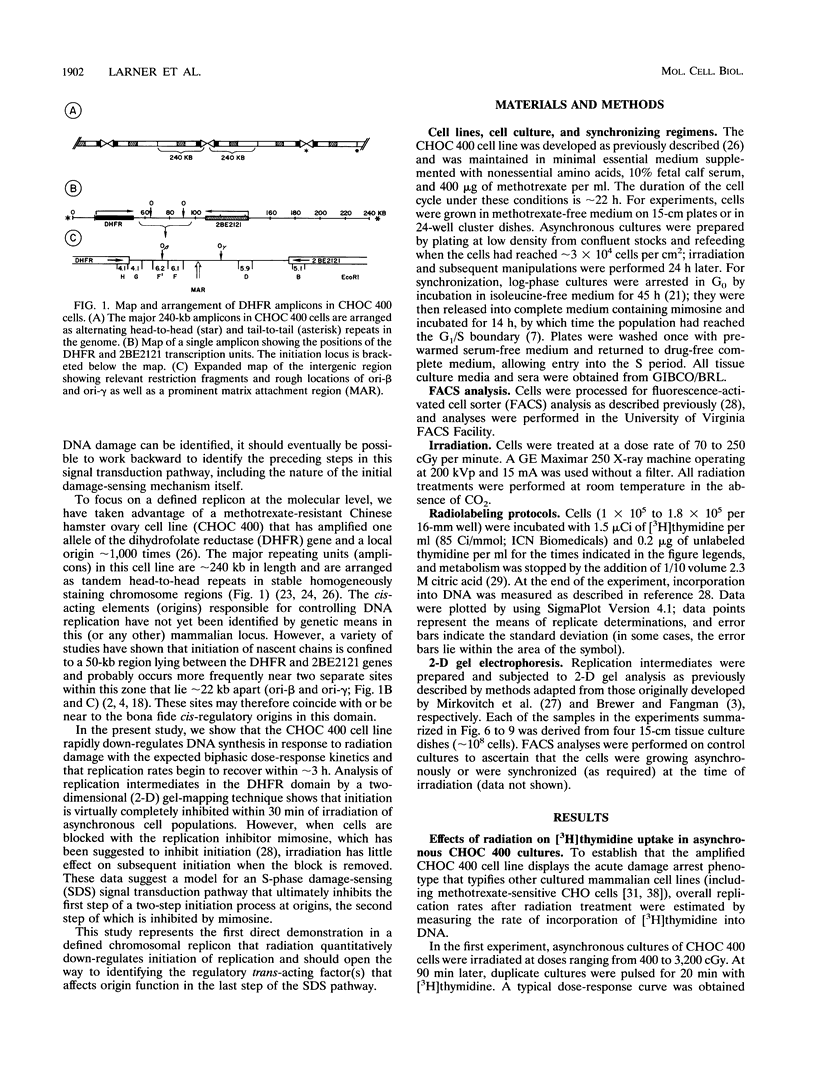

It has recently been shown that the tumor suppressor p53 mediates a signal transduction pathway that responds to DNA damage by arresting cells in the late G1 period of the cell cycle. However, the operation of this pathway alone cannot explain the 50% reduction in the rate of DNA synthesis that occurs within 30 min of irradiation of an asynchronous cell population. We are using the amplified dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) domain in the methotrexate-resistant CHO cell line, CHOC 400, as a model replicon in which to study this acute radiation effect. We first show that the CHOC 400 cell line retains the classical acute-phase response but does not display the late G1 arrest that characterizes the p53-mediated checkpoint. Using a two-dimensional gel replicon-mapping method, we then show that when asynchronous cultures are irradiated with 900 cGy, initiation in the DHFR locus is completely inhibited within 30 min and does not resume for 3 to 4 h. Since initiation in this locus occurs throughout the first 2 h of the S period, this result implies the existence of a p53-independent S-phase damage-sensing pathway that functions at the level of individual origins. Results obtained with the replication inhibitor mimosine define a position near the G1/S boundary beyond which cells are unable to prevent initiation at early-firing origins in response to irradiation. This is the first direct demonstration at a defined chromosomal origin that radiation quantitatively down-regulates initiation.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anachkova B., Hamlin J. L. Replication in the amplified dihydrofolate reductase domain in CHO cells may initiate at two distinct sites, one of which is a repetitive sequence element. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Feb;9(2):532–540. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer B. J., Fangman W. L. The localization of replication origins on ARS plasmids in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1987 Nov 6;51(3):463–471. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhans W. C., Vassilev L. T., Caddle M. S., Heintz N. H., DePamphilis M. L. Identification of an origin of bidirectional DNA replication in mammalian chromosomes. Cell. 1990 Sep 7;62(5):955–965. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90270-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver J. E. Replication of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in X-ray-damaged cells: evidence for a nuclear-specific mechanism that down-regulates replication. Radiat Res. 1992 Sep;131(3):338–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver J. E., Rose R., Mitchell D. L. Replication of chromosomal and episomal DNA in X-ray-damaged human cells: a cis- or trans-acting mechanism? Radiat Res. 1990 Dec;124(3):294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkwel P. A., Hamlin J. L. Initiation of DNA replication in the dihydrofolate reductase locus is confined to the early S period in CHO cells synchronized with the plant amino acid mimosine. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Sep;12(9):3715–3722. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkwel P. A., Vaughn J. P., Hamlin J. L. Mapping of replication initiation sites in mammalian genomes by two-dimensional gel analysis: stabilization and enrichment of replication intermediates by isolation on the nuclear matrix. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Aug;11(8):3850–3859. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin J. L., Leu T. H., Vaughn J. P., Ma C., Dijkwel P. A. Amplification of DNA sequences in mammalian cells. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1991;41:203–239. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. H., Weinert T. A. Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science. 1989 Nov 3;246(4930):629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan M. B., Onyekwere O., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Craig R. W. Participation of p53 protein in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1991 Dec 1;51(23 Pt 1):6304–6311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan M. B., Zhan Q., el-Deiry W. S., Carrier F., Jacks T., Walsh W. V., Plunkett B. S., Vogelstein B., Fornace A. J., Jr A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia. Cell. 1992 Nov 13;71(4):587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbitz S. J., Plunkett B. S., Walsh W. V., Kastan M. B. Wild-type p53 is a cell cycle checkpoint determinant following irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Aug 15;89(16):7491–7495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalande M., Hanauske-Abel H. M. A new compound which reversibly arrests T lymphocyte cell cycle near the G1/S boundary. Exp Cell Res. 1990 May;188(1):117–121. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90285-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb J. R., Petit-Frère C., Broughton B. C., Lehmann A. R., Green M. H. Inhibition of DNA replication by ionizing radiation is mediated by a trans-acting factor. Int J Radiat Biol. 1989 Aug;56(2):125–130. doi: 10.1080/09553008914551271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu T. H., Hamlin J. L. High-resolution mapping of replication fork movement through the amplified dihydrofolate reductase domain in CHO cells by in-gel renaturation analysis. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Feb;9(2):523–531. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A. J., Kang H. S., Billheimer F. E. DNA replication in SV40 infected cells. I. Analysis of replicating SV40 DNA. J Mol Biol. 1970 Jun 14;50(2):549–568. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A. J., Momand J. Tumor suppressor genes: the p53 and retinoblastoma sensitivity genes and gene products. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990 Jun 1;1032(1):119–136. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(90)90015-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone L. R., White A., Sprouse J., Livanos E., Jacks T., Tlsty T. D. Altered cell cycle arrest and gene amplification potential accompany loss of wild-type p53. Cell. 1992 Sep 18;70(6):923–935. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looney J. E., Hamlin J. L. Isolation of the amplified dihydrofolate reductase domain from methotrexate-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Feb;7(2):569–577. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C., Looney J. E., Leu T. H., Hamlin J. L. Organization and genesis of dihydrofolate reductase amplicons in the genome of a methotrexate-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Jun;8(6):2316–2327. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.6.2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino F., Okada S. Effects of ionizing radiation on DNA replication in cultured mammalian cells. Radiat Res. 1975 Apr;62(1):37–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milbrandt J. D., Heintz N. H., White W. C., Rothman S. M., Hamlin J. L. Methotrexate-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cells have amplified a 135-kilobase-pair region that includes the dihydrofolate reductase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Oct;78(10):6043–6047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkovitch J., Mirault M. E., Laemmli U. K. Organization of the higher-order chromatin loop: specific DNA attachment sites on nuclear scaffold. Cell. 1984 Nov;39(1):223–232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca P. J., Dijkwel P. A., Hamlin J. L. The plant amino acid mimosine may inhibit initiation at origins of replication in Chinese hamster cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Oct;12(10):4375–4383. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitis G., Pardee A. B. Citric acid arrest and stabilization of nucleoside incorporation into cultured cells. Anal Biochem. 1980 Jan 1;101(1):221–224. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter R. B. Inhibition of mammalian cell DNA synthesis by ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1986 May;49(5):771–781. doi: 10.1080/09553008514552981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter R. B., Young B. R. Formation of nascent DNA molecules during inhibition of replicon initiation in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976 Jan 19;418(2):146–153. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(76)90063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter R. B., Young B. R. X-ray-induced inhibition of DNA synthesis in Chinese hamster ovary, human HeLa, and Mouse L cells. Radiat Res. 1975 Dec;64(3):648–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povirk L. F. Localization of inhibition of replicon initiation to damaged regions of DNA. J Mol Biol. 1977 Jul;114(1):141–151. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark G. R., Wahl G. M. Gene amplification. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:447–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn J. P., Dijkwel P. A., Hamlin J. L. Replication initiates in a broad zone in the amplified CHO dihydrofolate reductase domain. Cell. 1990 Jun 15;61(6):1075–1087. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90071-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. p53 function and dysfunction. Cell. 1992 Aug 21;70(4):523–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters R. A., Hildebrand C. E. Evidence that x-irradiation inhibits DNA replicon initiation in Chinese hamster cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975 Jul 8;65(1):265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(75)80088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walworth N., Davey S., Beach D. Fission yeast chk1 protein kinase links the rad checkpoint pathway to cdc2. Nature. 1993 May 27;363(6427):368–371. doi: 10.1038/363368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe I. Radiation effects on DNA chain growth in mammalian cells. Radiat Res. 1974 Jun;58(3):541–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler J. A., Gross J. D. Escherichia coli mutants temperature-sensitive for DNA synthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1971;113(3):273–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00339547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Tainsky M. A., Bischoff F. Z., Strong L. C., Wahl G. M. Wild-type p53 restores cell cycle control and inhibits gene amplification in cells with mutant p53 alleles. Cell. 1992 Sep 18;70(6):937–948. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Khodairy F., Carr A. M. DNA repair mutants defining G2 checkpoint pathways in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 1992 Apr;11(4):1343–1350. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]