Abstract

Clinical treatment of cartilage defects is challenging due to concomitant post-traumatic joint inflammation. This study was to demonstrate that the antioxidant ability of human adult synovium-derived stem cells (SDSCs) could be enhanced by ex vivo expansion on a decellularized stem cell matrix (DSCM). Microarray was used to evaluate oxidative, antioxidative, and chondrogenic status in SDSCs after expansion on the DSCM and induction in the chondrogenic medium. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added to create oxidative stress in either expanded SDSCs or chondrogenically induced premature pellets. The effect of H2O2 on SDSC proliferation was evaluated using flow cytometry. Chondrogenic differentiation of expanded SDSCs was evaluated using histology, immunostaining, biochemical analysis, and real-time polymerase chain reaction. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways and p21 were compared in the DSCM and plastic-flask-expanded SDSCs with or without H2O2 treatment. We found that expansion on the DSCM upregulated antioxidative gene levels and chondrogenic potential in human SDSCs (hSDSCs), retarded the decrease in the cell number and the increase in apoptosis, and rendered SDSCs resistant to cell-cycle G1 arrest resulting from H2O2 treatment. Treatment with 0.05 mM H2O2 during cell expansion yielded pellets with increased chondrogenic differentiation; treatment in premature SDSC pellets showed that the DSCM-expanded cells had a robust resistance to H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 and p38 were positively involved in antioxidative and chondrogenic potential in SDSCs expanded on the DSCM in which p21 was downregulated. DSCM could be a promising cell expansion system to provide a large number of high-quality hSDSCs for cartilage regeneration in a harsh joint environment.

Introduction

Cartilage defects, especially from trauma-induced cartilage injuries, do not heal or self-regenerate well due to the absence of blood supply. Current treatment options include microfracture, osteochondral transplantation, and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) [1]. Compared to other treatments, ACI has been shown to work in older, active populations with larger defects. Some limitations of ACI, however, prevent its ultimate success. For example, trauma-induced cartilage injuries may lead to early post-traumatic osteoarthritis [2]. A major source of the destructive power of inflammation is the direct and indirect generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals after the inflammatory cytokine response [3]. Despite studies investigating the inflammatory environment in cartilage repair [4,5], there are few reports focusing on the effect of oxidative stress on stem cell-based chondrogenesis. Oxidative stress induces chondrocyte senescence [6]; oxidative DNA damage has been demonstrated in osteoarthritic articular cartilage in both porcine [7] and human samples [8], indicating that oxidative stress is one of the most important hurdles to overcome to increase the efficacy of ACI.

Adult stem cells could be an excellent cell candidate not only because of their self-renewal and multilineage differentiation capacities but also due to their antioxidant capacity [9]. A recent report demonstrated that there were distinct DNA responses to damage and repair mechanisms in stem cells that render them tolerant to stressors [10], making them superior to their more differentiated counterparts [11,12]. Synovium-derived stem cells (SDSCs), a tissue-specific stem cell for chondrogenesis, are an appropriate stem cell candidate for cartilage engineering and regeneration [13,14]. The regenerative capacity of synovium has been demonstrated after surgical and chemical synovectomy [15]. Synovium can be obtained in a minimally invasive fashion with few complications during arthroscopy. Although stem cells exhibit some intrinsic degree of antioxidant capacity [16,17], this intracellular defense system may be rapidly overwhelmed in an inflammatory environment, resulting in poor cell survival and engraftment [18–20].

For successful cell therapy or tissue engineering, measures must be taken to control the inflammatory and oxidative environment in which cartilage is regenerated. The regulation of intracellular ROS is crucial for cell survival in the harsh environment and guarantees successful cell therapy. Our previous work suggested that the decellularized stem cell matrix (DSCM) provides an in vitro microenvironment for SDSC rejuvenation in terms of enhancing expanded cell proliferation and chondrogenic potential [21–23]. It is possible that a small-punch biopsy plus our DSCM approach would be sufficient for growth of a clinically useful quantity of cells. Our recent findings indicated that DSCM expansion decreases expanded cell ROS level [24,25]. In addition, our microarray data suggested that DSCM expansion could upregulate SDSCs' antioxidant gene levels, indicating that DSCM expansion may benefit SDSCs by increasing the resistance to oxidative stress and promoting cell chondrogenic capacity. In this study, we hypothesized that human SDSCs (hSDSCs) expanded on DSCM acquired an ability to resist oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and enjoyed expanded cell chondrogenic potential.

Materials and Methods

SDSC culture

Adult human synovial fibroblasts [4 donors, 2 men (39 and 42 years old) and 2 women (43 and 47 years old), average 43 years old with no known joint disease], referred to as hSDSCs [26], were obtained from Asterand (North America Laboratories, Detroit, MI). hSDSCs were plated and cultured in a growth medium [Alpha-Minimum Essential Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL Fungizone (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)] at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 and 21% O2 incubator. The medium was changed every 3 days.

DSCM preparation

The preparation of DSCM was described in our previous study [21]. Briefly, plastic flasks (Plastic) were precoated with 0.2% gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C for 1 h and seeded with passage-3 (P3) hSDSCs. After cells reached 90% confluence, 50 μM l-ascorbic acid phosphate (Wako Chemicals USA, Inc., Richmond, VA) was added for 8 days. The deposited matrix was incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 containing 20 mM ammonium hydroxide at 37°C for 5 min and stored at 4°C in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL Fungizone.

Global gene expression by microarrays and data analyses

A preliminary study was conducted to evaluate global gene expression changes in hSDSCs during DSCM expansion and chondrogenic induction. P3 hSDSCs were expanded on either DSCM (Ecell) or Plastic (Pcell) for one passage. Expanded cells were chondrogenically induced in a pellet culture system (Ep and Pp, respectively) for 21 days. Total RNAs were isolated from expanded cells and 21-day pellets using Trizol (Invitrogen) followed by additional purification using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The required amount of cDNA (5.5 μg) was processed for fragmentation and biotin labeling using the GeneChip® WT Terminal Labeling Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The entire reaction of fragmented and biotin-labeled cDNA (50 μL) with added hybridization controls was hybridized to the human GeneChip 1.0 ST Exon Arrays (Affymetrix) at 45°C for 17 h in the GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640 (Affymetrix). The scaling factor, background, noise, and percent present were calculated according to manufacturer's procedures (Affymetrix). The raw data were uploaded into GeneSpring (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and Partek (St. Louis, MO) software for initial analysis and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Redwood City, CA) for pathway and functional analysis. Briefly, raw intensity was background-subtracted, robust multiarray average normalized, log-transformed, and fold changes determined. The batch effects (scan date) were removed before fold change calculation.

SDSC expansion and H2O2 treatment

P3 hSDSCs were cultured at 3,000 cells/cm2 for 1 passage on 2 substrates: DSCM or Plastic. To determine the effects of H2O2 on expanded cells, oxidative stress was induced 48 h after cell seeding by exposing cells to 0.05, 0.5, and 5 mM H2O2 throughout the culture. Since higher concentrations (0.5 and 5 mM) of H2O2 caused obvious cell death, 0.05 mM H2O2 was chosen for our cell expansion studies. Nontreated groups served as a control. The cell number was counted using a hemocytometer. Expanded cells were also evaluated for proliferation index, apoptosis, and cell cycle using flow cytometry.

Cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle analysis

P3 hSDSCs were prelabeled with CellVue® Claret (Sigma) at 2×10−6 M for 5 min according to the manufacturer's protocol. After a 7-day expansion, cells treated with or without 0.05 mM H2O2 in the DSCM and Plastic groups were collected and analyzed using BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For each sample, 20,000 events were collected using CellQuest™ Pro Software (BD Biosciences), and the cell proliferation index was analyzed by ModFit LT 3.1 (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

After cell expansion, an annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) Apoptosis Detection Kit (Biovision, Mountain View, CA) was used to detect apoptosis. Briefly, 2×105 cells treated with or without 0.05 mM H2O2 in the DSCM and Plastic groups (n=3 each) were labeled with FITC annexin V and propidium iodide for 15 min. For each sample, 10,000 events were collected; samples were analyzed using BD FACSCalibur. FCS Express V3 (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA) was used to generate the histograms.

After hSDSCs were treated with 0.05 mM H2O2 for 2 h, the medium was switched to a fresh medium for cell recovery. Detached cells were washed with PBS containing 1% FBS, and then fixed with 80% ethanol at 4°C for 15 min. Fixed cells were stained with 20 μg/mL propidium iodide in a PBS buffer containing 1% FBS, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 50 μg/mL RNase. After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, a flow cytometer was used to determine the percentage of cells in different phases of the cell cycle (G1, S, and G2/M phase) with CFlow software (Accuri Cytometers, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI).

Chondrogenic differentiation

The effect of H2O2 treatment on SDSC-based chondrogenesis was evaluated in 2 phases. During cell expansion on either DSCM or Plastic, 0.05 mM H2O2 was added to the medium throughout the culture period. A 21-day chondrogenic induction followed in a pellet culture system. We also evaluated the effect of H2O2 on premature SDSC pellets, in which both DSCM- and Plastic-expanded SDSCs were incubated in a chondrogenic medium for 21 days, followed by the medium being supplemented with 0.05 or 0.1 mM H2O2 for 7 days. The chonodrogenic induction protocol is briefly described below: after in vitro expansion, 0.3×106 of SDSCs from each group were centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min in a 15-mL polypropylene tube to form a pellet. After overnight incubation, the pellets were cultured in a serum-free chondrogenic medium consisting of a high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 40 μg/mL proline, 100 nM dexamethasone, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.1 mM ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, and 1×ITS™ Premix [6.25 μg/mL insulin, 6.25 μg/mL transferrin, 6.25 μg/mL selenous acid, 5.35 μg/mL linoleic acid, and 1.25 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), from BD Biosciences] with supplementation of 10 ng/mL transforming growth factor beta 3 (PeproTech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ). Chondrogenic differentiation was evaluated using histology, immunostaining, biochemical analysis, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Histology and immunostaining

The pellets (n=3) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight, followed by dehydrating in a gradient ethanol series, clearing with xylene, and embedding in paraffin blocks. Sections that were 5-μm thick were histochemically stained with Alcian blue (Sigma; counterstained with fast red) for sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). For immunohistochemical analysis, the sections were immunolabeled with primary antibodies against collagen II (II-II6B3; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) and collagen X (Sigma), followed by the secondary antibody of biotinylated horse anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Immunoactivity was detected using Vectastain ABC reagent (Vector) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as a substrate.

Biochemical analysis

The pellets (n=4) were digested for 4 h at 60°C with 125 μg/mL papain in a PBE buffer (100 mM phosphate and 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH 6.5) containing 10 mM cysteine, by using 200 μL enzyme per sample. To quantify cell density, the amount of DNA in the papain digestion was measured using the QuantiT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA assay kit (Invitrogen) with a CytoFluor® Series 4000 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). GAG was measured using dimethylmethylene blue dye and a Spectronic BioMate 3 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Milford, MA) with bovine chondroitin sulfate as a standard.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from samples (n=4) using an RNase-free pestle in TRIzol (Invitrogen). About 1 μg of mRNA was used for reverse transcriptase with a High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems) at 37°C for 120 min. Chondrogenic marker genes [collagen II (COL2A1), aggrecan (ACAN), and SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 9 (SOX9)] and hypertrophic marker gene [collagen X (COL10A1)] were customized by Applied Biosystems as part of the Custom TaqMan Gene Expression Assays [27]. Eukaryotic 18S RNA (Assay ID HS99999901_s1) was carried out as the endogenous control gene. Real-time PCR was performed with the iCycler iQ™ Multi-Color Real-Time PCR Detection (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). Relative transcript levels were calculated as χ=2−ΔΔCt, in which ΔΔCt=ΔE−ΔC, ΔE=Ctexp−Ct18s, and ΔC=Ctct1−Ct18s.

Western blot

To further determine potential mechanisms underlying DSCM-mediated cell proliferation and differentiation under oxidative stress, the expanded cells from each group were homogenized and dissolved in the lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) with protease inhibitors. Total proteins were quantified using BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Thirty micrograms of protein from each sample was denatured and separated using NuPAGE® Novex® Bis-Tris Mini Gels (Invitrogen) in the XCell SureLock™ Mini-Cell (Invitrogen) at 120 V at 4°C for 3 h. Bands were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen) using an XCell II™ Blot module (Invitrogen) at 15 V at 4°C overnight. The membrane was incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies in 5% BSA, 1×TBS (10 mM Tris–HCl and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), and 0.05% Tween-20 at room temperature for 1 h (β-actin served as an internal control), followed by the secondary antibody of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at room temperature for 1 h. SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and CL-XPosure Film (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for exposure. The primary antibodies used in immunoblotting included the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family antibody sampler kit (catalog number: 9926) and phosphor (p)-MAPK family antibody sampler kit (catalog number: 9910) as well as p21 Waf1/Cip1 (12D1) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog number: 2947) were ordered from Cell Signaling.

Statistics

Numerical data are presented as the mean and the standard error of the mean. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparison in biochemistry and real-time PCR data analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

DSCM expansion promoted hSDSC antioxidation and chondrogenic potential

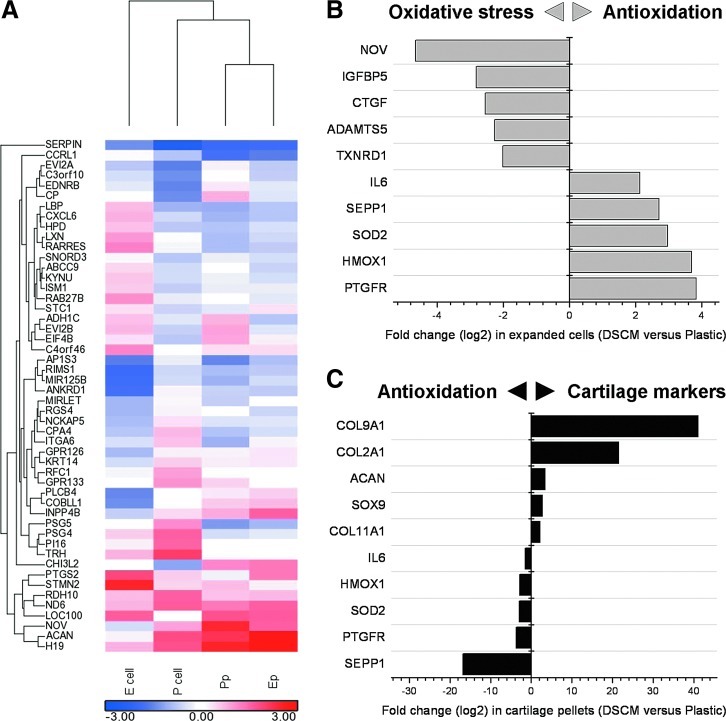

To explore the possible mechanisms of DSCM interaction with expanded cells, a microarray was conducted for global analysis of gene expression in expanded hSDSCs and subsequent chondrogenic differentiation in a pellet system. The top 100 genes (50 up- and 50 downregulated) were analyzed for gene–gene interaction networks and signaling pathways (Fig. 1A). The top associated networks included (1) antigen presentation, cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, and inflammatory response; (2) cellular development; and (3) cell death, cellular growth, and proliferation. Top molecular and cellular functions with P-values ranging from 1.59E-08 to 5.07E-03 included (1) cellular movement and development; (2) cellular growth and proliferation; and (3) cell-to-cell signaling and interaction. The top pathways included (1) endothelin-1 signaling; (2) acute phase response signaling; and (3) G-protein-coupled receptor signaling.

FIG. 1.

Effect of decellularized stem cell matrix (DSCM) pretreatment on human synovium-derived stem cell (hSDSC) oxidative stress and chondrogenic potential. In the heatmap (A), the expression intensity was log2-transformed and visualized by color ranging from low expression (blue) to high expression (red). The comparisions of Ecell versus Pcell in the genes (>2-fold change) related to oxidative stress and antioxidation (B) and Ep versus Pp in the genes (>2-fold change) related to antioxidation and cartilage markers (C) were clustered by hierarchical clustering methods. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

During the cell expansion phase, we found that DSCM expansion upregulated the genes for antioxidation, including prostaglandin F2alpha receptor (PTGFR), heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 (HMOX1), superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), selenoprotein P, plasma, 1 (SEPP1), and interleukin 6 (IL-6). In the meantime, DSCM expansion also downregulated the genes for oxidative stress, including nephroblastoma overexpressed (NOV), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (IGFBP5), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 5 (ADAMTS5), and thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) (Fig. 1B). In the subsequent chondrogenic differentiation, the genes of antioxidation as above were downregulated in DSCM-pretreated hSDSCs; chondrogenic marker genes were also upregulated, including collagen 9 alpha 1 (COL9A1), collagen 2 alpha 1 (COL2A1), aggrecan (ACAN), SOX9, and collagen 11 alpha 1 (COL11A1) (Fig. 1C).

DSCM expansion alleviated oxidative stress-mediated proliferation reduction through lowering the apoptosis rate and elevating the G1 transition

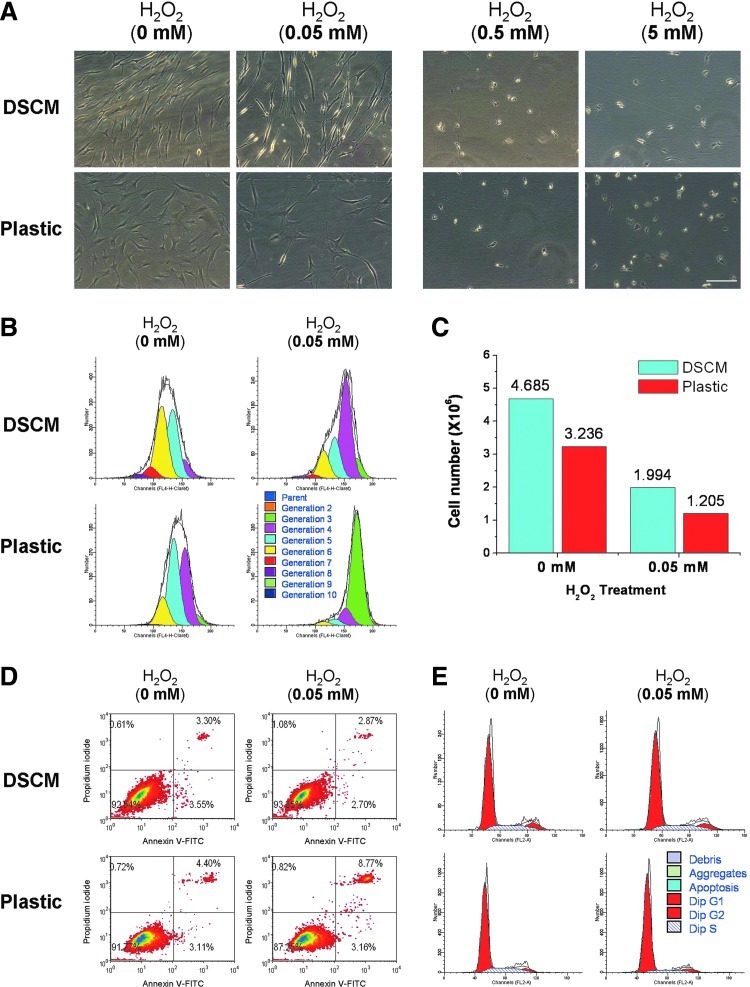

To determine an appropriate concentration of H2O2 for this study, a series of concentrations (0, 0.05, 0.5, and 5 mM) were chosen to evaluate toxicity in hSDSCs (Fig. 2A). After hSDSCs were plated on either the DSCM or Plastic for 48 h, the medium was added with varying concentrations of H2O2. When treated with high concentrations of H2O2 (0.5 and 5 mM), a number of floating cells and attached round cells were in both groups, indicative of cell death. At a low concentration of H2O2 treatment (0.05 mM), both DSCM and Plastic groups showed that a decrease in cell number compared with the nontreated group despite a similarity in cell morphology. hSDSCs grown on Plastic displayed random arrangements and flattened shapes, while DSCM expanded hSDSCs exhibited an ordered arrangement and glistening fiber-like shapes. Thus, 0.05 mM of H2O2 was chosen for cell expansion to evaluate its effect on cell proliferation and subsequent multilineage differentiation.

FIG. 2.

Effect of DSCM pretreatment on hSDSC expansion under hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). (A) Cell morphology of hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic was shown under phase-contrast microscope after treatment with varying concentrations (0, 0.05, 0.5, and 5 mM) of H2O2 for 4 days. Scale bar is 200 μm. (B) The effect of 0.05 mM H2O2 on the proliferation of hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic was evaluated using proliferation index by flow cytometry. (C) The effect of 0.05 mM H2O2 on the proliferation of hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic was evaluated using cell count (n=8 flasks each group) by a hemocytometer. (D) The effect of 0.05 mM H2O2 on apoptosis of hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic was evaluated using flow cytometry. (E) The effect of 0.05 mM H2O2 on the cell cycle of hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic was evaluated using flow cytometry. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

To determine the effect of the DSCM on cell proliferation under oxidative stress, expanded hSDSCs were evaluated using both proliferation index (Fig. 2B) and cell number counting (Fig. 2C) approaches. Under treatment with H2O2, the proliferation index in the DSCM group was 9.20 compared to 4.36 in the Plastic group; without H2O2 treatment, the proliferation index in the DSCM group was 18.75 compared to 10.62 in the Plastic group. Despite the fact that H2O2 treatment affected the proliferation index in both groups, DSCM-expanded cells retained more than twice the proliferation compared to Plastic-expanded cells, which is also consistent with cell number counts. Despite the same initial seeding density (0.525×106 in a 175-cm2 flask), after a 7-day incubation under H2O2 treatment, DSCM expansion yielded 1.99×106 cells compared to 1.21×106 cells in the Plastic group; without H2O2 treatment, the cell number in the DSCM group was 4.69×106 compared to 3.24×106 in the Plastic group. The proliferation difference in both the DSCM and Plastic groups may be related to a lower apoptosis rate in the DSCM group (Fig. 2D). There was a slightly lower apoptosis rate in the DSCM group (3.30%) compared to the Plastic group (4.40%); under treatment with H2O2, the apoptosis rate in the DSCM group decreased to 2.87% compared to an increase in the Plastic group (8.77%).

The discrepancy in cell proliferation may also be explained by cell cycle data (Fig. 2E). Flow cytometric analysis revealed concomitant cell cycle arrest at the G1 checkpoint when expanded on Plastic versus DSCM and incubated in the medium supplemented with versus without 0.05 mM H2O2. After hSDSCs were treated with 0.05 mM H2O2 for 20 h, we found that Plastic-expanded cells were 85.00% (vs. 75.20% without treatment) in the G1 phase, 8.63% (vs. 18.18% without treatment) in the S phase, and 6.36% (vs. 6.62% without treatment) in the G2/M phase, suggesting that H2O2 treatment resulted in an arrest at the G1 phase of the cell cycle. In contrast, we found that DSCM-expanded cells were 73.62% (vs. 72.70% without treatment) in the G1 phase, 16.81% (vs. 16.76% without treatment) in the S phase, and 9.57% (vs. 10.54% without treatment) in the G2/M phase, suggesting that DSCM-expanded cells were able to resist the G1 arrest from H2O2. We also found that after 20 h of H2O2 treatment, DSCM expansion could greatly enhance cell proliferation ability, as evidenced by the cells either without H2O2 treatment (10.54% vs. 6.62% in the G2/M phase) or with H2O2 treatment (9.57% vs. 6.36% in the G2/M phase), which was in accord with the initial cells before H2O2 treatment (5.11% on DSCM vs. 3.73% on Plastic in the G2/M phase) (data not shown).

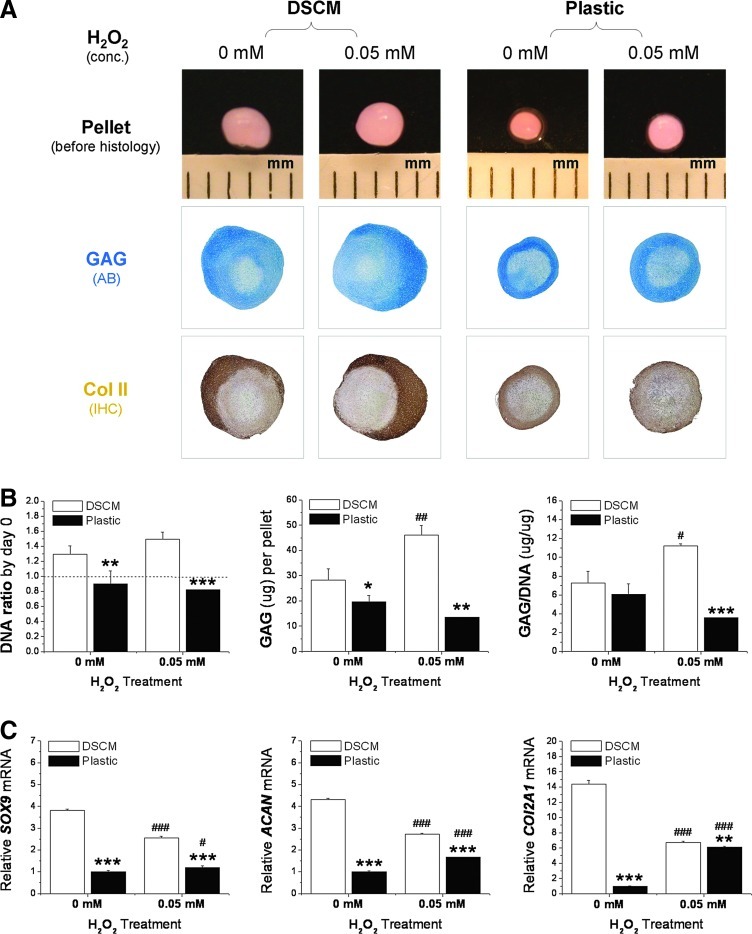

DSCM-expanded hSDSCs acquired enhanced chondrogenic potential after treatment with H2O2 in both proliferation and chondrogenic phases

The effect of oxidative stress on expanded hSDSC chondrogenic differentiation was evaluated in 2 distinct phases: the proliferation phase (H2O2 was added during cell expansion followed by chondrogenic induction) and the chondrogenic phase (H2O2 was added 21 days after expanded cell chondrogenic induction). For the proliferation phase study, the expanded hSDSCs with or without H2O2 treatment were incubated in a pellet system with a chondrogenic medium for 21 days. DSCM-expanded hSDSCs yielded pellets with larger size and intense staining of cartilage markers, in terms of sulfated GAGs and collagen II, compared with Plastic-expanded hSDSCs (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, H2O2 treatment during cell expansion enhanced the resulting pellet in both size and chondrogenic differentiation, especially for the DSCM group, which is supported by biochemical analysis data. DSCM-expanded hSDSCs yielded pellets with higher GAG amount and ratio of GAG to DNA (chondrogenic index) when treated with H2O2 compared with the nontreated group. In contrast, Plastic-expanded hSDSCs yielded pellets with a relatively low GAG amount and chondrogenic index when treated with H2O2, but did not show a significant difference when compared with the nontreated group (Fig. 3B). Despite enhanced chondrogenic differentiation in DSCM-expanded hSDSCs as evidenced by histology and biochemical analysis data, H2O2 treatment did downregulate chondrogenic marker gene expression (SOX9, ACAN, and COL2A1) in the pellets after a 21-day chondrogenic induction. On the other hand, for Plastic-expanded hSDSCs, H2O2 treatment upregulated chondrogenic marker gene expression, despite the fact that all chondrogenic marker genes from Plastic-expanded hSDSCs were significantly lower than those from DSCM-expanded hSDSCs under treatment either with or without H2O2 (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Effect of DSCM pretreatment with 0.05 mM H2O2 on expanded hSDSC chondrogenic potential. (A) hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic with H2O2 treatment were chondrogenically induced in a pellet culture system for 21 days. Alcian blue (AB) was used to stain sulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was used to detect collagen II (Col II). (B) Biochemical analysis was used for DNA and GAG contents in the 21-day chondrogenically induced pellets. Cell proliferation and viability were evaluated using the DNA ratio (DNA content at day 21 adjusted by that at day 0). Chondrogenic index at day 21 was evaluated using a ratio of GAG to DNA. (C) Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to evaluate chondrogenic marker gene expression (SOX9, ACAN, and COL2A1) in day-21 pellets. Data are shown as average±standard deviation (SD) for n=4. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001 compared with the corresponding DSCM group. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, and ###P<0.001 compared with the corresponding group without H2O2 treatment. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

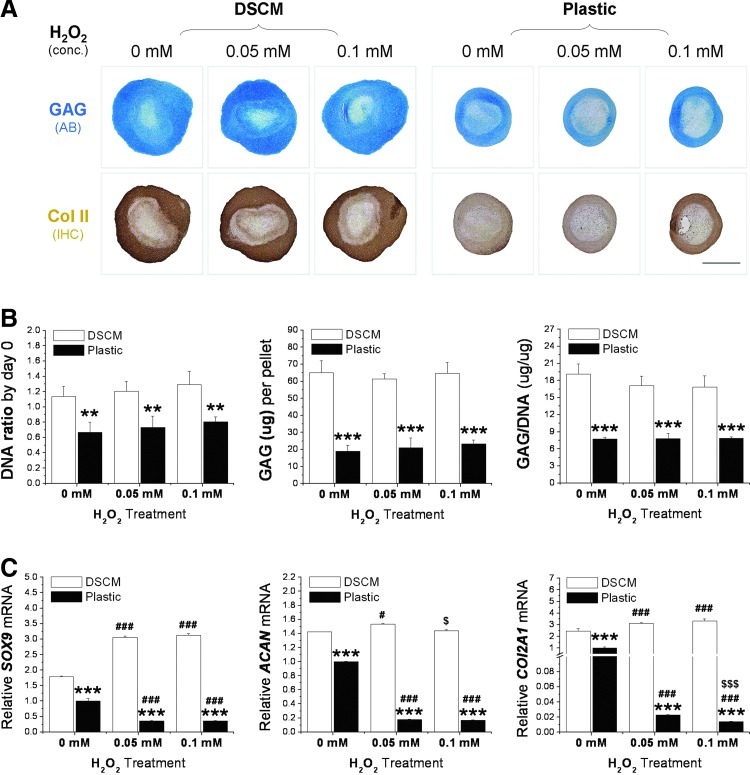

For the differentiation-phase study, expanded hSDSCs incubated in a pellet system with a chondrogenic medium for 21 days were subsequently supplemented with H2O2 for an additional 7 days. DSCM-expanded hSDSCs yielded pellets with larger size and intense staining of cartilage markers, with or without H2O2 treatment, compared with Plastic-expanded hSDSCs (Fig. 4A). There was no difference in the size and chondrogenic staining of pellets from either DSCM- or Plastic-expanded cells between H2O2-treated and nontreated groups. The histology data were supported by biochemical data, in which DSCM-expanded hSDSCs yielded pellets with a higher DNA ratio, GAG amount, and chondrogenic index than those from Plastic-expanded cells, despite no significant difference from H2O2 treatment in either DSCM or Plastic expanded cells being found (Fig. 4B). Real-time PCR data showed that, compared to pellets from Plastic-expanded cells, DSCM-expanded cells yielded pellets with a higher chondrogenic marker gene expression with or without H2O2 treatment. DSCM-expanded hSDSCs exhibited an upregulation of all 3 chondrogenic marker genes (SOX9, ACAN, and COL2A1) when treated with a low concentration of H2O2 (0.05 mM) compared to an upregulation of 2 chondrogenic marker genes (SOX9 and COL2A1) when treated with a higher concentration of H2O2 (0.1 mM). In contrast, Plastic-expanded hSDSCs displayed a dramatic decrease of all 3 chondrogenic marker genes under treatment with H2O2 at both 0.05 and 0.1 mM (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Effect of DSCM pretreatment on expanded hSDSC chondrogenic differentiation with either 0.05 or 0.1 mM H2O2. (A) hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic with H2O2 treatment were chondrogenically induced in a pellet culture system for 21 days and treated with H2O2 for the following 7 days. AB was used to stain sulfated GAGs. IHC staining was used to detect Col II. Scale bar is 1 mm. (B) Biochemical analysis was used for DNA and GAG contents in the 28-day chondrogenically induced pellets. Cell proliferation and viability were evaluated using DNA ratio (DNA content at day 28 adjusted by that at day 0). Chondrogenic index at day 28 was evaluated using ratio of GAG to DNA. (C) Real-time PCR was used to evaluate chondrogenic marker gene expression (SOX9, ACAN, and COL2A1) in day-28 pellets. Data are shown as average±SD for n=4. **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001 compared with the corresponding DSCM group. #P<0.05, and ###P<0.001 compared with the corresponding group without H2O2 treatment. $P<0.05 and $$$P<0.001 compared with the corresponding group treated with 0.05 mM H2O2. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

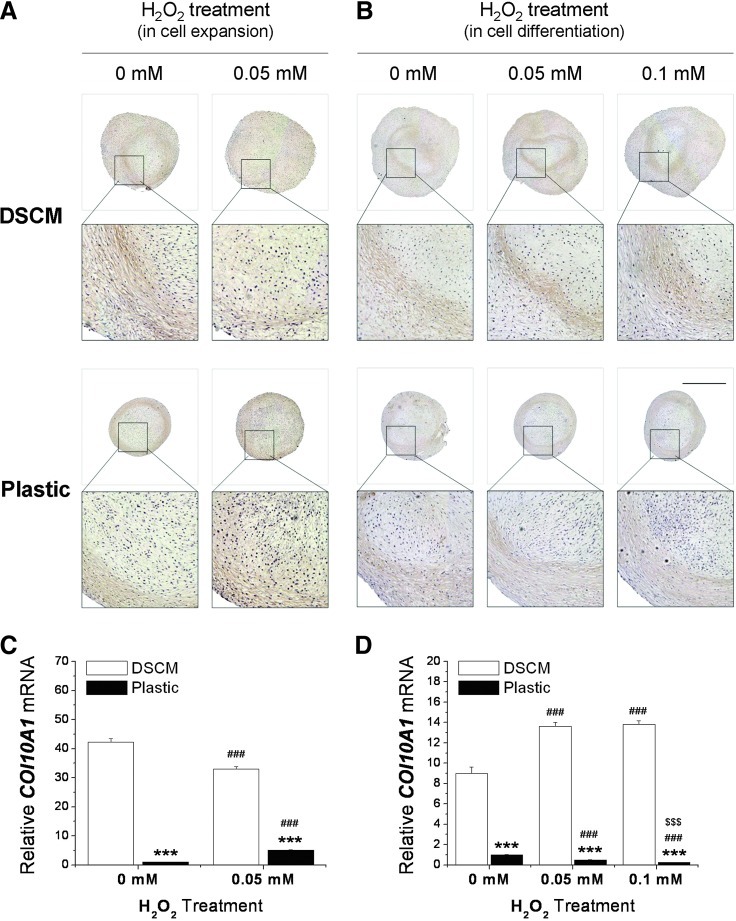

Similar to the SOX9 mRNA level, for the proliferation-phase study, DSCM-expanded hSDSCs exhibited a downregulation of the COL10A1 level compared to an upregulation in Plastic-expanded cells after H2O2 treatment followed by a 21-day pellet culture (Fig. 5A, C). For the differentiation-phase study, DSCM-expanded hSDSCs displayed an upregulation of COL10A1 level compared to a downregulation in Plastic-expanded cells after a 21-day pellet culture followed by a 7-day H2O2 treatment (Fig. 5B, D).

FIG. 5.

Effect of H2O2 treatment in an either cell expansion or chondrogenic differentiation phase on expanded SDSC chondrogenic hypertrophy. (A, C) hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic with 0.05 mM H2O2 treatment were chondrogenically induced in a pellet culture system for 21 days. (B, D) hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic were chondrogenically induced in a pellet culture system for 21 days and treated with H2O2 for the following 7 days. IHC staining was used to detect collagen X (A, B). Scale bar is 1 mm. Real-time PCR was used to evaluate hypertrophy marker gene expression (COL10A1) (C, D). Data are shown as average±SD for n=4. ***P<0.001 compared with the corresponding DSCM group. ###P<0.001 compared with the corresponding group without H2O2 treatment. $$$P<0.001 compared with the corresponding group treated with 0.05 mM H2O2. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

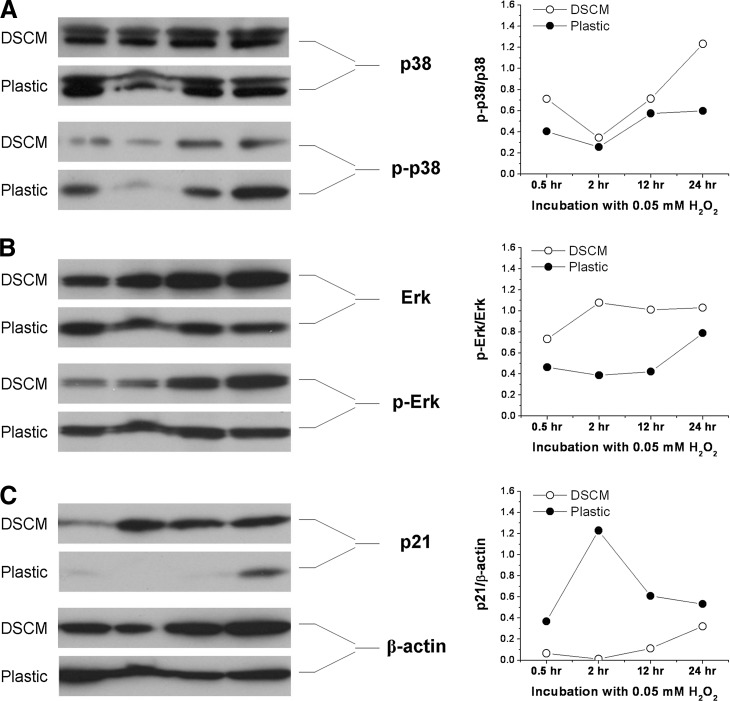

Under oxidative stress, DSCM-expanded hSDSCs exhibited an upregulation of p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 and a downregulation of p21

To further determine potential mechanisms underlying DSCM-mediated cell proliferation and differentiation under oxidative stress, western blot was used to investigate the expression of the MAPK signaling pathway [extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (Erk1/2), p38] and a senescence-associated marker (p21) in hSDSCs after exposure to 0.05 mM H2O2. ImageJ analysis showed that with H2O2 treatment, DSCM-expanded cells exhibited higher levels of p-p38/p38 (Fig. 6A) and p-Erk/Erk (Fig. 6B) compared to those from Plastic-expanded cells; in contrast, DSCM=expanded cells exhibited a lower level of p21 (Fig. 6C), a senescence-associated marker, compared to those from Plastic-expanded cells.

FIG. 6.

Western blot was used to measure the levels of p38 [(A) p-p38/p38] and Erk1/2 [(B) p-Erk/Erk] (the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway) and the level of p21 (a senescence-associated marker) [(C) p21/β-actin] in the hSDSCs expanded on either DSCM or Plastic after the treatment with 0.05 mM H2O2. β-actin served as an internal control. ImageJ software was used to quantify immunoblotting bands.

Discussion

Chondrocytes produce superoxide, H2O2, and hydroxyl radicals under resting conditions [28,29] and nitric oxide during chondrogenesis [30]. ROS are produced at a low level in articular chondrocytes and are important as integral actors of intracellular signaling mechanisms; they modulate gene expression and are likely to contribute to the maintenance of cartilage homeostasis [31]. Increased production of ROS contributes to the pathology observed in inflammatory joint diseases [31], which is believed to be responsible for the fact that cartilage defects are difficult to repair, except in the presence of inflammatory factors (interleukin 1-beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) [5]. Our recent studies demonstrated that DSCM expansion enhanced SDSC proliferation and chondrogenic potential [21,22]. It would be interesting to know if DSCM expansion could resist H2O2-induced oxidative stress while enhancing cell expansion and chondrogenic capacity. Our microarray data suggested that DSCM expansion not only dramatically enhanced hSDSC chondrogenic potential but also promoted expanded cell antioxidation ability, indicating that DSCM expansion could rejuvenate hSDSCs by decreasing the senescence-associated secretory phenotypes [32].

Our study found that during the cell proliferation phase, DSCM expansion decreased the decline in cell proliferation and the increase in cell apoptosis in hSDSCs under H2O2-induced oxidative stress; this finding may be because DSCM-expanded cells were able to resist the G1 arrest from H2O2. In contrast to the cell proliferation phase, expanded SDSCs were differently affected in chondrogenic potential by oxidative stress in terms of an upregulation in Plastic-expanded SDSCs compared to a downregulation in DSCM-expanded SDSCs. Our result differed from a previous report [33], in which H2O2 inhibited cartilage formation in chicken micromass cultures. This difference could be because they used 1 mM H2O2 treatment for 30 min, and we used 0.05 mM H2O2 as a continuous treatment. Moreover, different types of cells have different responses and tolerances to H2O2-induced oxidative stress [34]. In fibroblasts, low concentrations of H2O2 (<0.01 mM) stimulate cell proliferation; intermediate concentrations (∼0.15 mM) cause growth arrest or senescence; and high levels of H2O2 (>0.4 mM) induce rapid apoptosis [35]. Our dose of H2O2 causing growth arrest is also in accordance with a previous study [36], in which inflammatory conditions (rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis) were imitated; synoviocytes were inhibited in both hyaluronan and DNA synthesis at concentrations of H2O2 (10–100 μM), less than those which caused loss of cell integrity (>200 μM). The preconditioned effect from 0.05 mM H2O2 might be responsible for the upregulation of chondrogenic marker genes [37].

We also evaluated the effect of H2O2 on 21-day SDSC pellets in a chondrogenic medium and found that predifferentiated SDSCs in a pellet could better resist H2O2-induced oxidative stress, as evidenced by comparable staining of sulfated GAGs and collagen II as well as stable cell viability and chondrogenic index. Our data were in accord with a study investigating the effects of peroxynitrite (0.1–0.6 mM) and H2O2 (0.1–4 mM) on poly(adp-ribose) polymerase activation and extracellular matrix (ECM) production of high-density micromass cultures prepared from chick limb bud mesenchymal cells [38]. They found that both oxidative species strongly inhibited matrix formation of high-density micromass cultures treated on day 2, but not on day 5. In micromass cultures, the major steps of cartilage differentiation occur on days 2 and 3 when young cartilage cells start to secrete a specific ECM rich in collagen II and aggrecan [39], suggesting that ECM could protect chondrogenically differentiated mesenchymal cells from oxidative stress. Despite resistance at the protein level, DSCM-expanded SDSCs yielded pellets with enhanced levels of chondrogenic marker genes upon stimulation by H2O2; in contrast, Plastic-expanded SDSCs yielded pellets with downregulation of chondrogenic marker genes, indicating that DSCM expansion renders SDSCs with enhanced chondrogeneic potential.

Despite an enhanced antioxidation level in DSCM-expanded cells, chondrogenic induction made these cells lose their antioxidation capacity when compared with Plastic-expanded cells. Since enhanced endogenous antioxidant levels can protect cells from oxidative stress and inhibit chondrocyte hypertrophy [40], a decline in the antioxidative level may explain why DSCM-expanded hSDSCs exhibited a higher level of collagen X after chondrogenic induction compared to those grown on Plastic. When H2O2 was used to treat chondrogenically differentiated SDSCs, it was also understandable that DSCM-expanded SDSCs exhibited an enhanced collagen X expression compared with Plastic-expanded SDSCs. After H2O2 treatment during monolayer culture, Plastic-expanded SDSCs exhibited an increased ROS level, which is responsible for a higher level of collagen X expression in these chondrogenically differentiated cells. Interestingly, we found that DSCM-expanded SDSCs displayed a different response when incubated in a chondrogenic induction medium, while H2O2-treated SDSCs had a lower level of collagen X than nontreated cells. The mechanism is still under investigation.

The Erk cascade is a prominent component of the MAPK family that, in particular, plays an integral role in both growth factor and stress signaling, although it preferentially regulates cell growth and differentiation [41]. p38MAPKs are described as stress-activated protein kinases, because they are frequently activated by a wide range of environmental stresses such as oxidative stress and cytokines to induce inflammation, a key process in the host defense system [42]. The activation of Erk1/2 and p38MAPK after treatment with H2O2 was demonstrated in different types of cells, such as PC12 cells [43], skeletal myoblasts [44], alveolar epithelial cells [45], and ATDC5 cells [40], indicating that Erk1/2 and p38MAPK have universal protection against oxidative stress in different cell types. Our western blot data showed that the MAPK pathway was involved in the H2O2-mediated and DSCM-mediated cell activities in terms of proliferation and differentiation; both Erk1/2 and p38MAPK were upregulated in DSCM-expanded SDSCs, indicating that DSCM expansion might activate the MAPK signal pathway, helping combat H2O2-induced oxidative stress. A higher level of p38MAPK in DSCM-expanded SDSCs after H2O2 treatment might benefit subsequent differentiation due to its positive role in mesenchymal stem cell chondrogenesis [46]. p21, a potent cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor, functions as a regulator of cell cycle progression at G1 through binding and inhibiting the activity of cyclin–CDK2 or CDK4 complexes. Compared to SDSCs grown on Plastic, DSCM-expanded SDSCs exhibiting a lower level of p21 might result from the observation that DSCM-expanded cells were able to resist G1 arrest from H2O2, demonstrating that DSCM expansion could rejuvenate SDSCs from oxidative stress-induced cell senescence [47].

In the present study, for the first time, we demonstrated that the DSCM could enhance adult hSDSC in vitro expansion and chondrogenic potential; more importantly, we found that DSCM expansion could prevent hSDSCs from oxidative stress-induced cell senescence, in terms of cell proliferation and differentiation. Since most patients with cartilage defects have diseased joints with oxidative stress, this finding provides important information for the potential application of using the DSCM in cartilage engineering and regeneration. DSCM could be a promising cell expansion system to provide a large number of high-quality hSDSCs for cartilage regeneration in a harsh joint environment. Our DSCM model, as a new strategy and intervention aimed at reducing oxidative damage in implanted cells, might be a promising alternative in the treatment of osteoarthritis patients with cartilage defects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzanne Smith for editing. This project was partially supported by research grants from West Virginia University Senate Research Grant Award (R-12-010), the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, the AO Foundation (project no. S-12-19P), and NIH R03 (no. 5 R03 DE021433-02).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Fitzpatrick K. Tokish JM. A military perspective to articular cartilage defects. J Knee Surg. 2011;24:159–166. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John T. Stahel PF. Morgan SJ. Schulze-Tanzil G. Impact of the complement cascade on posttraumatic cartilage inflammation and degradation. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:781–790. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhalla NS. Golfman L. Takeda S. Takeda N. Nagano M. Evidence for the role of oxidative stress in acute ischemic heart disease: a brief review. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francioli S. Cavallo C. Grigolo B. Martin I. Barbero A. Engineered cartilage maturation regulates cytokine production and interleukin-1β response. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2773–2784. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1826-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wehling N. Palmer GD. Pilapil C. Liu F. Wells JW. Müller PE. Evans CH. Porter RM. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibit chondrogenesis by human mesenchymal stem cells through NF-kappaB-dependent pathways. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:801–812. doi: 10.1002/art.24352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandl A. Hartmann A. Bechmann V. Graf B. Nerlich M. Angele P. Oxidative stress induces senescence in chondrocytes. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1114–1120. doi: 10.1002/jor.21348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen AF. Davies CM. De Lin M. Fermor B. Oxidative DNA damage in osteoarthritic porcine articular cartilage. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:828–833. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grishko VI. Ho R. Wilson GL. Pearsall AW., 4th Diminished mitochondrial DNA integrity and repair capacity in OA chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urish KL. Vella JB. Okada M. Deasy BM. Tobita K. Keller BB. Cao B. Piganelli JD. Huard J. Antioxidant levels represent a major determinant in the regenerative capacity of muscle stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:509–520. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanpain C. Mohrin M. Sotiropoulou PA. Passegué E. DNA-damage response in tissue specific and cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dernbach E. Urbich C. Brandes RP. Hofmann WK. Zeiher AM. Dimmeler S. Antioxidative stress-associated genes in circulating progenitor cells: evidence for enhanced resistance against oxidative stress. Blood. 2004;104:3591–3597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He T. Peterson TE. Holmuhamedov EL. Terzic A. Caplice NM. Oberley LW. Katusic ZS. Human endothelial progenitor cells tolerate oxidative stress due to intrinsically high expression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2021–2027. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000142810.27849.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones B. Pei M. Synovium-derived stem cells: a tissue-specific stem cell for cartilage tissue engineering and regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:301–311. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2012.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pei M. He F. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Synovium-derived stem cell-based chondrogenesis. Differentiation. 2008;76:1044–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentley G. Kreutner A. Ferguson AB. Synovial regeneration and articular cartilage changes after synovectomy in normal and steroid-treated rabbits. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:454–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim WS. Park BS. Kim HK. Park JS. Kim KJ. Choi JS. Chung SJ. Kim DD. Sung JH. Evidence supporting antioxidant action of adipose-derived stem cells: protection of human dermal fibroblasts from oxidative stress. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;49:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valle-Prieto A. Conget PA. Human mesenchymal stem cells efficiently manage oxidative stress. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1885–1893. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angelos MG. Kutala VK. Torres CA. He G. Stoner JD. Mohammad M. Kuppusamy P. Hypoxic reperfusion of the ischemic heart and oxygen radical generation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H341–H347. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00223.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bredesen DE. Neuronal apoptosis. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:839–851. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao EH. Yu Y. Fukuda N. Oxidative stress on progenitor and stem cells in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2006;7:101–108. doi: 10.2174/138920106776597685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He F. Chen X. Pei M. Reconstruction of an in vitro tissue-specific microenvironment to rejuvenate synovium-derived stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3809–3821. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li JT. Pei M. Optimization of an in vitro three-dimensional microenvironment to reprogram synovium-derived stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:703–712. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pei M. Li JT. Shoukry M. Zhang Y. A review of decellularized stem cell matrix: a novel cell expansion system for cartilage tissue engineering. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;22:333–343. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v022a25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He F. Pei M. Extracellular matrix enhances differentiation of adipose stem cells from infrapatellar fat pad toward chondrogenesis. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011 doi: 10.1002/term.505. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pei M. He F. Kish VL. Expansion on extracellular matrix deposited by human bone marrow stromal cells facilitates stem cell proliferation and tissue-specific lineage potential. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:3067–3076. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JT. Jones B. Zhang Y. Pei M. Low density expansion rescues human synovium-derived stem cells from replicative senescence. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2012;2:363–374. doi: 10.1007/s13346-012-0094-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li JT. He F. Pei M. Creation of an in vitro microenvironment to enhance human fetal synovium-derived stem cell chondrogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;345:357–365. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henrotin Y. Deby-Dupont G. Deby C. De Bruyn M. Lamy M. Franchimont P. Production of active oxygen species by isolated human chondrocytes. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:562–567. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.7.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiran TS. Moulton PJ. Hancock JT. Detection of superoxide and NADPH oxidase in porcine articular chondrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:736–743. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson K. Jung A. Murphy A. Andreyev A. Dykens J. Terkeltaub R. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is a downstream regulator of nitric oxide effects on chondrocyte matrix synthesis and mineralization. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1560–1570. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1560::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henrotin YE. Bruckner P. Pujol JP. The role of reactive oxygen species in homeostasis and degradation of cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:747–755. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freund A. Orjalo AV. Desprez PY. Campisi J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zákány R. Szíjgyártó Z. Matta C. Juhász T. Csortos C. Szucs K. Czifra G. Bíró T. Módis L. Gergely P. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits formation of cartilage in chicken micromass cultures and decreases the activity of calcineurin: implication of ERK1/2 and Sox9 pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2005;305:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon SO. Yun CH. Chung AS. Dose effect of oxidative stress on signal transduction in aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:1597–1604. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(02)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim BY. Han MJ. Chung AS. Effects of reactive oxygen species on proliferation of Chinese hamster lung fibroblast (V79) cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:686–698. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutadilok N. Smith MM. Ghosh P. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on the metabolism of human rheumatoid and osteoarthritic synovial fibroblasts in vitro. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:219–226. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.4.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramakrishnan P. Hecht BA. Pedersen DR. Lavery MR. Maynard J. Buckwalter JA. Martin JA. Oxidant conditioning protects cartilage from mechanically induced damage. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:914–920. doi: 10.1002/jor.21072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zákány R. Bakondi E. Juhász T. Matta C. Szíjgyártó Z. Erdélyi K. Szabó E. Módis L. Virág L. Gergely P. Oxidative stress-induced poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in chick limb bud-derived chondrocytes. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:597–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandell LJ. Adler P. Developmental patterns of cartilage. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D731–D742. doi: 10.2741/sandell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morita K. Miyamoto T. Fujita N. Kubota Y. Ito K. Takubo K. Miyamoto K. Ninomiya K. Suzuki T, et al. Reactive oxygen species induce chondrocyte hypertrophy in endochondral ossification. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1613–1623. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishida E. Gotoh Y. The MAP kinase cascade is essential for diverse signal transduction pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:128–131. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90019-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coulthard LR. White DE. Jones DL. McDermott MF. Burchill SA. p38MAPK: stress responses from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su QJ. Chen XW. Chen ZB. Sun SG. Involvement of ERK1/2 and p38MAPK in up-regulation of 14-3-3 protein induced by hydrogen peroxide preconditioning in PC12 cells. Neurosci Bull. 2008;24:244–250. doi: 10.1007/s12264-008-0307-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kefaloyianni E. Gaitanaki C. Beis I. ERK1/2 and p38-MAPK signalling pathways, through MSK1, are involved in NF-kappaB transactivation during oxidative stress in skeletal myoblasts. Cell Signal. 2006;18:2238–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carvalho H. Evelson P. Sigaud S. González-Flecha B. Mitogen-activated protein kinases modulate H(2)O(2)-induced apoptosis in primary rat alveolar epithelial cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:502–513. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J. Zhao Z. Liu J. Huang N. Long D. Wang J. Li X. Liu Y. MEK/ERK and p38 MAPK regulate chondrogenesis of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through delicate interaction with TGF-beta1/Smads pathway. Cell Prolif. 2010;43:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ju Z. Choudhury AR. Rudolph KL. A dual role of p21 in stem cell aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:333–344. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]