Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the association between the long-term use of bisphosphonates and the risk of hip fracture compared to never use among women aged 65 years or older.

Design

Case–control study nested in a cohort.

Setting

General practice research database operated by the Spanish Medicines Agency.

Participants

Cases of hip fracture were defined as women aged 65 years or older with a validated first diagnosis of hip fracture between 2005 and 2008. Five controls free of hip fracture were matched on age and calendar-year with each case.

Interventions

Information on bisphosphonate use, hip fractures, comedication and comorbidities was collected.

Primary outcomes

Hip fracture risk comparing bisphosphonate users versus never users.

Secondary outcomes

Hip fracture risk comparing bisphosphonate users versus never users by individual drugs.

Results

The study included 2009 incident hip fractures and 10 045 matched controls. Hip-fracture risk did not differ between bisphosphonate users and never users, adjusted OR=1.09 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.27). No association was observed between hip fracture risk and cumulative duration of bisphosphonate treatment. However, when treatment duration is analysed as time since first prescription, hip fracture risks of the different subgroups compared to never users obtained were as follows: <1 year, OR 0.85 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.21); 1 to <3 years, OR 1.02 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.26); ≥3 years, OR 1.32 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.65) (p for trend=0.03).

Conclusions

Ever use of oral bisphosphonates was not associated with a decreased risk of hip fracture in women aged 65 or older as compared to never use. No association was observed between hip fracture risk and cumulative duration of bisphosphonate treatment. However, when treatment duration is analysed as time since first prescription, a statistically significant increased risk for hip fracture was observed in patients exposed to bisphosphonates over 3 years.

Trial Registration

Spanish Ministry of Health. TRA-071

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY, PRIMARY CARE

Article summary.

Article focus

The hypothesis of this study is that oral bisphosphonates may not be effective in reducing hip-fracture risk in clinical practice in long-term use.

Key messages

Ever use of oral bisphosphonates was not associated with a decreased risk of hip fracture in women aged 65 or older as compared to never use.

No association was observed between hip-fracture risk and cumulative duration of bisphosphonate treatment.

When treatment duration is analysed as time since first prescription, a statistically significant increased risk for hip fracture was observed in patients exposed to bisphosphonates over 3 years.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strength of this study is that it sheds light on the effects of oral bisphosphonates on hip-fracture risk in clinical practice in a Mediterranean population.

One of the main limitations is the relatively short follow-up period.

Introduction

Background

When bisphosphonates came onto the market, they had demonstrated efficacy in the improvement of bone density, but there was no evidence for reduction of hip fractures. They were introduced on the theoretical assumption that the increase in bone density implied a strengthening of the bone structure, and therefore a reduction in the risk of fracture.

In most pivotal trials comparing the effects of alendronate,1–4 risedronate5–7 or ibandronate8 versus placebo, hip fractures were considered as secondary endpoints and outcomes did not show any clear potential benefit in decreasing hip-fracture risk. Several meta-analyses of alendronate and risedronate have been carried out and a statistically significant benefit of these drugs over placebo is reported. However, the clinical significance of the findings is debatable and methodology biases are also present in the reviews.9 A recent meta-analysis obtained similar results. However, a quality assessment of the trials was carried out and revealed an unclear or high risk of bias in approximately 75% of the trials. This means that the small significant reduction in hip fracture may not be real, or at best, is an exaggeration of the real benefit.10

In 2006, the longest ever clinical trial evaluating the effects of bisphosphonates was published. After 5 years under alendronate, women were randomised to either continue taking the drug or receive placebo for another 5 years. Discontinuation of alendronate for up to 5 years did not change numerically or statistically either non-spine or hip-fracture incidence.11 However, no comparison between alendronate use versus no use was established. This prompted us to carry out the present study.12

The long-term use of bisphosphonates has been associated with deleterious effects on bone structure such as osteonecrosis of the jaw, atypical fractures (subtrochanteric and diaphyseal) and bone pain, which prompted several safety communications issued by both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency.13 14

In 2008, a cohort study in Danish women with no previous hip fracture was published. The incidence of hip fractures increased in the group treated with alendronate by 50% in relative terms and by 6 cases/1000 women-years in absolute terms.15 Updated information from this Danish cohort was published in 2010 and the increased incidence of hip fractures in women taking alendronate was confirmed.16

Objective

The aim of this study is to evaluate the association between the long-term use of bisphosphonates and the risk of hip fracture compared to never use among women aged 65 years or older.

Methods

Study design and setting

We carried out a case-control study nested in a cohort in Spain using the information from BIFAP (Base de Datos para la Investigación Farmacoepidemiológica en Atención Primaria, Database for Pharmacoepidemiologic Research in Primary Care). This is a longitudinal population-based database kept by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices that collates, from 2001 onwards, the computerised medical records of more than 1800 physicians throughout Spain. It includes anonymised information on over 3.2 million patients, totalling over 13.7 million person-years of follow-up.17 18

This project was approved by the Navarre Research Ethics Board, Pamplona, Spain. All data were anonymised and no written consent was necessary for this type of study according to the Spanish regulations (law 41/2002, article 16).

Participants

Cases were defined as women aged 65 years or older with a first diagnosis of hip fracture, using the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC)-1 codes, recorded between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2008, and with at least 1 year of follow-up in BIFAP before the event date. The date of hospitalisation served as the index date. All hip-fracture cases were double-checked and validated by both BIFAP and the research team. We excluded women with any history of cancer, Paget disease, prevalent hip fracture and fractures resulting from trauma or motor vehicle collisions. For each case, five controls with no history of hip fracture by the time of the index date of their corresponding case were selected, matched by the same age and calendar year of enrolment in BIFAP.

Medication use and other covariates

Use of bisphosphonates before the index date was obtained from the computerised database. Duration of bisphosphonate exposure was evaluated by examining prescriptions for oral alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate or etidronate from the beginning of therapy to the index date or the corresponding date among controls (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification (ATC) codes: alendronate, M05BA04; alendronate plus vitamin D, M05BB; risedronate, M05BA07 and ibandronate, M05BA06).

Individuals were classified as ever versus never users. Ever users were also divided into current users (if the most recent prescription lasted through the index date or ended in the month before it), recent users (if the most recent prescription ended between 1 and 6 months before the index date) and past users (if the most recent prescription ended more than 6 months before the index date).

In order to assess the effects of treatment length on the outcomes, four different subgroups were considered based on the cumulative duration of actual treatment, namely 30 days or less; >30 days to ≤1 year; >1 to ≤3 years and over 3 years. The effects of time of bisphosphonate exposure on hip-fracture risk were also analysed. Exposure was measured as the time (in days) since the first prescription.

Information on comorbidities (ICPC-1 codes) and use of other medications (ATC codes) was obtained. Patients were considered exposed if the most recent prescription lasted through the index date or ended in the month before it. Other variables such as weight (kg), height (cm), body mass index (kg/m2) and smoking status (yes/no/past smoker) were obtained as well.

Statistical methods

Between 2005 and 2008, we expected to find some 2000 cases and 10 000 controls in our database. This would provide statistical power >90% to detect a change >20% in the risk of having hip fracture associated to biphosphonate use with an α risk of 5% and a prevalence of exposure of 20%.

We used conditional logistic regression to estimate the ORs and 95% CIs for the association between bisphosphonate exposure and hip fractures. Bisphosphonate use was categorised as ever versus never. In separate analyses, current, recent or past use was also evaluated. Treatment duration was assessed as well and results were tested to identify a trend. The level of significance was established at p=0.05. In the duration analysis adjusted for exposure, never users were considered as the reference group. These results were also compared to bisphosphonate users for less than 1 year as a sensitivity analysis in case of selection bias.

An initial ‘model 1’ adjusted only for matching variables. A second ‘model 2’ adjusted additionally for smoking, body mass index (BMI), alcoholism, previous fracture, kidney disease, malabsorption, stroke, dementia, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, thyroid disease, proton pump inhibitors (PPI) (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, antihypertensives, oral corticosteroids (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), raloxifene, hormone replacement therapy and thiazolidinediones.

Results

Participants

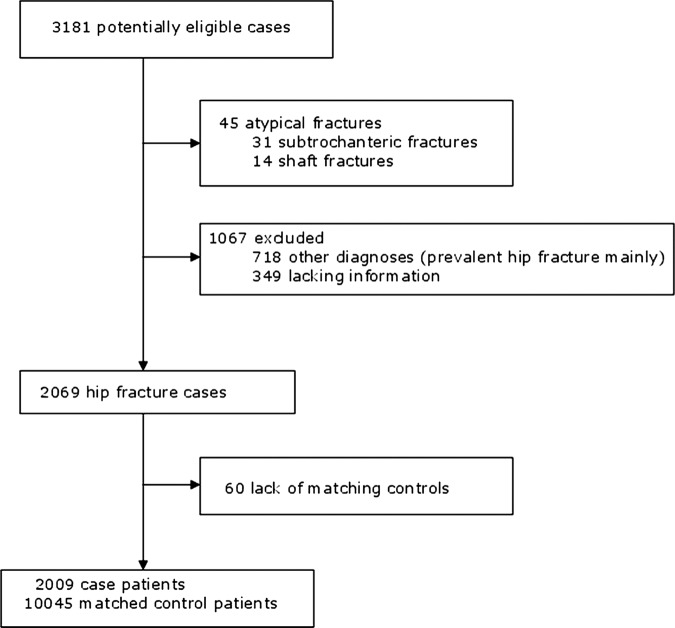

Between 2005 and 2008, 3181 potentially eligible cases were registered. Out of them, we validated 2069 hip fractures and 45 atypical fractures (31 subtrochanteric and 14 shaft fractures). Out of the remainder, 1067 records were classified as ‘no case’, 718 ‘other diagnoses’ and 349 ‘lacking information’. Sixty cases were excluded owing to lack of matching controls. A total of 2009 cases were obtained and 10 045 matching controls were selected (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of study population.

The average age of cases was 82.4±6.6 years. In general terms, comorbidities and drug use were more prevalent in cases, whereas smoking status and BMI were similar between cases and controls (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases and controls

| Cases | Controls | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2009 | 10045 | |

| Age (years) | 82.4 (6.6) | 82.4 (6.6) | 1.00 |

| Smoking (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Non-current smoker | 69.5 | 73.4 | |

| Current smoker | 2.7 | 2.0 | |

| Not recorded | 27.8 | 24.6 | |

| Alcoholism (%) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.30 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.2 (5.0) | 29.0 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| <20 kg/m2 (%) | 2.7 | 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| 20–<25 kg/m2 (%) | 17.6 | 12.2 | |

| 25–<30 kg/m2 (%) | 25.5 | 28.9 | |

| ≥30 kg/m2 (%) | 19.8 | 30.8 | |

| Not recorded (%) | 34.4 | 27.1 | |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||

| Previous fracture | 17.2 | 10.1 | <0.0001 |

| Kidney disease | 4.9 | 3.6 | 0.006 |

| Malabsorption | 2.3 | 2.1 | 0.54 |

| Stroke | 10.7 | 6.2 | <0.0001 |

| Dementia | 14.6 | 6.2 | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2.3 | 1.3 | 0.0006 |

| Diabetes | 22.2 | 17.7 | <0.0001 |

| Epilepsy | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.03 |

| Parkinson's disease | 4.9 | 1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Thyroid disease | 10.2 | 10.8 | 0.47 |

| Use of medication (%) | |||

| PPI or H2 receptor blocker | 38.2 | 34.0 | 0.0004 |

| Anxiolytic | 29.1 | 24.8 | <0.0001 |

| Antidepressants | 22.6 | 13.8 | <0.0001 |

| Antihypertensives | 56.8 | 61.6 | <0.0001 |

| Corticosteroids | 8.0 | 7.4 | 0.33 |

| Sedatives | 11.8 | 9.3 | 0.0006 |

| Raloxifene | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.14 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.00 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.43 |

Values correspond to the percentage or means (SD).

*p Values calculated from χ2 test for categorical values and Student's t test for continuous variables.

PPI, proton pump inhibitors.

Outcome data

Hip fractures were more frequent among bisphosphonate users, 283 (14.1%) compared to never users, 1207 (12.0%). Results according to timing, duration and bisphosphonate exposure are described in table 2.

Table 2.

Association of any bisphosphonate use with the risk of hip fracture

| Cases | Controls | Average cumulative duration (days) | Time since first BP prescription (days) | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Use | ||||||

| No use | 1726 (85.9) | 8838 (88.0) | – | – | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Ever use | 283 (14.1) | 1207 (12.0) | 600 (556) | 968 (622) | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.39) | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.27) |

| Timing | ||||||

| No use | 1726 (85.9) | 8838 (88.0) | – | – | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Past use | 111 (5.5) | 347 (3.5) | 315 (415) | 1164 (601) | 1.63 (1.31 to 2.04) | 1.50 (1.19 to 1.89) |

| Recent use | 43 (2.1) | 127 (1.3) | 515 (521) | 774 (599) | 1.74 (1.22 to 2.47) | 1.34 (0.92 to 1.95) |

| Current use | 129 (6.4) | 733 (7.3) | 769 (563) | 903 (612) | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.10) | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.03) |

| p for trend | 0.54 | 0.53 | ||||

| Duration | ||||||

| No use (≤30 days) | 1726 (85.9) | 8838 (88.0) | – | – | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| >30 days to ≤1 year | 139 (6.9) | 533 (5.3) | 147 (106) | 687 (590) | 1.34 (1.10 to 1.63) | 1.20 (0.97 to 1.47) |

| >1 to ≤3 years | 92 (4.6) | 458 (4.6) | 684 (211) | 956 (419) | 1.03 (0.82 to 1.30) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.20) |

| >3 years | 52 (2.6) | 216 (2.2) | 1566 (375) | 1698 (437) | 1.25 (0.91 to 1.70) | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.60) |

| p for trend | 0.16* | 0.63* | ||||

| Time since first BP use | ||||||

| No use (≤30 days) | 1726 (85.9) | 8838 (88.0) | – | – | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| >30 days to ≤1 years | 41 (2.0) | 222 (2.2) | 140 (99) | 194 (103) | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.33) | 0.85 (0.60 to 1.21) |

| >1 to ≤3 years | 120 (6.0) | 546 (5.4) | 454 (299) | 727 (209) | 1.13 (0.92 to 1.38) | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.26) |

| >3 years | 122 (6.1) | 439 (4.4) | 990 (660) | 1618 (445) | 1.44 (1.17 to 1.78) | 1.32 (1.05 to 1.65) |

| p for trend† | 0.0008 | 0.03 | ||||

Model 1: Conditional logistic regression model.

Model 2: Conditional logistic regression model adjusted for smoking, body mass index, alcoholism, previous fracture, kidney disease, malabsorption, stroke, dementia, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and thyroid disease, PPI (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, antihypertensives, oral corticosteroids (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), raloxifene, hormone replacement therapy and thiazolidinediones.

*Modelled as the median duration of use in each category.

†Modelled as time in days since first bisphosphonate prescription (0 for no users).

BP, bisphosphonate.

Main results

Ever users of bisphosphonates had a higher risk of hip fracture compared to never users (unadjusted OR=1.21, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.39). After adjusting for comedication and pathologies, no significant differences were found between bisphosphonate users and never users, OR=1.09 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.27).

No association was observed between hip-fracture risk and cumulative duration of bisphosphonate treatment: <1 year, OR 1.20 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.47); 1 to <3 years, OR 0.94 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.20); ≥3 years, OR 1.15 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.60) (p for trend=0.63). However, when treatment duration is analysed as time since first prescription, hip-fracture risk of the different subgroups compared to never users obtained were as follows: <1 year, OR 0.85 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.21); 1 to <3 years, OR 1.02 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.26); ≥3 years, OR 1.32 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.65) (p for trend=0.03). If women exposed to bisphosphonates during less than 1 year were considered as the reference group, hip-fracture risks observed in the different subgroups were: 1 to <3 years, OR 1.56 (95% CI 0.73 to 3.31); ≥3 years, OR 2.31 (95% CI 1.00 to 5.36) (p for trend=0.03) (tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Risk of hip fracture by time since first prescription for bisphosphonates

| Cases | Controls | Average cumulative duration (days) | Time since first BP prescription (days) | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Time since first BP use | ||||||

| >30 days to ≤1 year | 41 (14.5) | 222 (18.4) | 157 (133) | 194 (103) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| >1 to ≤3 years | 120 (42.4) | 546 (45.2) | 535 (451) | 727 (209) | 1.23 (0.68 to 2.23) | 1.49 (0.71 to 3.13) |

| >3 years | 122 (43.1) | 439 (36.4) | 1138 (873) | 1618 (445) | 1.79 (0.94 to 3.40) | 2.21 (0.96 to 5.09) |

| p for trend* | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||

Model 1: Conditional logistic regression model.

Model 2: Conditional logistic regression model adjusted for smoking, body mass index, alcoholism, previous fracture, kidney disease, malabsorption, stroke, dementia, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and thyroid disease, PPI (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, antihypertensives, oral corticosteroids (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), raloxifene, hormone replacement therapy and thiazolidinediones.

*Modelled as time in days since first bisphosphonate prescription.

BP, bisphosphonate.

No significant trend was observed for timing (past, recent and current use). Past use of bisphosphonates was associated with a statistically significant increase in hip-fracture risk (OR=1.50, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.89), whereas current or recent use was not (table 2).

No protective effect on hip-fracture risk was observed when the results were analysed by individual drugs. On the contrary, a statistically significantly increased risk was found for ibandronate users (OR=3.67, 95% CI 1.31 to 10.3) and for switchers as well (OR=1.63, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.47; table 4).

Table 4.

Association of ever use of individual bisphosphonates with the risk of hip fracture

| Cases | Controls | Average duration | Time since first prescription | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | (days) | (days) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Never use | 1726 (85.9) | 8838 (88.0) | – | – | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Alendronate | 128 (6.4) | 598 (6.0) | 599 (566) | 956 (603) | 1.10 (0.90 to 1.34) | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.22) |

| Risedronate | 95 (4.7) | 438 (4.4) | 508 (459) | 822 (503) | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.41) | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.30) |

| Etidronate | 19 (1.0) | 63 (0.6) | 818 (629) | 1478 (746) | 1.55 (0.92 to 2.59) | 1.56 (0.91 to 2.65) |

| Ibandronate | 7 (0.4) | 9 (0.1) | 161 (137) | 239 (151) | 4.18 (1.55 to 11.2) | 3.67 (1.31 to 10.3) |

| Switcher | 34 (1.7) | 99 (1.0) | 898 (676) | 1397 (714) | 1.80 (1.21 to 2.68) | 1.63 (1.07 to 2.47) |

Model 1: Conditional logistic regression model.

Model 2: Conditional logistic regression model adjusted for smoking, body mass index, and alcoholism, previous fracture, kidney disease, malabsorption, stroke, dementia, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and thyroid disease, PPI (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, antihypertensives, oral corticosteroids (no use, ≤1 year, >1 year), raloxifene, hormone replacement therapy and thiazolidinediones.

Discussion

Key results

According to our findings, oral bisphosphonates may not decrease hip-fracture risk in elderly women. In order to reduce selection bias, results were adjusted for copathologies and medication. However, residual selection bias may still occur. In a cohort study in Danish women with a previous fracture but no previous hip fracture, the risk of hip fracture was increased in the group treated with alendronate.15 16 This study was performed on alendronate only, whereas in our study all oral bisphosphonates were included. Our findings are in line with the Danish study in which a higher hip-fracture risk was observed.

A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials assessed the effects of bisphosphonates on hip-fracture and wrist-fracture risk. Similar results to previous meta-analyses were observed, namely a 1% absolute reduction of hip-fracture risk in bisphosphonate users. What is new about this publication is that a quality assessment of trials was carried out and revealed an unclear or high risk of bias in approximately 75% of the trials. This means that the small, significant reduction in hip fracture may not be real, or at best, is an exaggeration of the real benefit,10 which is in line with our findings.

We evaluated the effects of treatment length and the results by individual drugs as secondary outcomes. No association was observed between hip-fracture risk and cumulative duration of bisphosphonate treatment. However, fracture risk increased with longer exposure to bisphosphonates. A statistically significant trend for increased risk of hip fracture was observed among bisphosphonate users, irrespective of whether the reference group was never users or women under treatment for less than 1 year. Results were tested against the two different reference groups because of the possible selection bias in any of them. The results were consistent in both analyses.

According to the results by individual drugs, no protective effect was observed. On the contrary, a statistically significant increased risk was found for ibandronate users and for switchers as well. Probably the ibandronate results in our study are conditioned by a small sample size.

No significant trend was observed for timing (past, recent and current use). Past users showed a statistically significantly higher fracture risk when compared to never users, whereas current or recent users did not. This could be interpreted as if bisphosphonates provided a protective effect on hip-fracture risk that disapears after drug withdrawal. However, there are some other possible explanations for this. First, treatment withdrawal could be more frequent in patients suffering from drug adverse reactions, in those who did not tolerate treatment, or in those who had a poorer clinical status. All these patients have a higher fracture risk, and selection bias is another possible explanation for a higher fracture risk in patients who stopped taking bisphosphonates.

Second, bisphosphonates accumulate in bone structure, and past users are exposed to the drug effects for many years after withdrawal. Given the relatively short follow-up period in this study, all patients are exposed to the drug effects irrespective of whether they are past, recent or current users. Thereby, interpreting results according to these subgroups may be meaningless. The Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX) trial shows that there is no difference in hip-fracture risk between past and current users. Past users had been under treatment for 5 years and had stopped taking the drug 5 years before assessment. This trial supports that alendronate accumulates in the bone, and past users are exposed to the drug effects for many years after withdrawal. Thereby, it makes sense to consider exposure to bisphosphonates in the results analysis. Also, we must take into account that in the FLEX trial there is no selection bias owing to randomisation, and consequently, its findings support that the higher risk observed in the past users in our study may be related to a selection bias and a longer exposure to bisphosphonates in this subgroup as well.

A recent article published by FDA researchers analysed the results of three long-term extension trials on alendronate, risedronate and zoledronic acid. Pooled data pertaining to patients who received continuous bisphosphonate treatment for six or more years resulted in fracture rates ranging from 9.3% to 10.6%, whereas the rate for patients switched to placebo was 8% to 8.8%. These data raise the question on whether long-term use of bisphosphonates is beneficial for patients.19

With long-term use, it is widely accepted that bisphosphonates may cause osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical (subtrochanteric and diaphyseal) fractures as well. Recently, a self-controlled case series analysis showed that bisphosphonate use was associated with osteonecrosis at any site.20 Deleterious effects on bone structure have been observed with bisphosphonates and denosumab as well, but not with other osteoporosis drugs. Both type of drugs inhibit bone turnover, and thereby bone strength may be weaker as a result of treatment. Besides, bisphosphonates prolong secondary mineralisation, leading to increased bone density, but decreased bone toughness occurs owing to higher mineral content (brittle bones).21 Since there is a biological rationale to explain the harmful effects of bisphosphonates on bone, more long-term studies are needed to test our findings.

Limitations

One of the main limitations in our study is the relatively short follow-up period. Besides, we relied on prescription data to determine the duration of bisphosphonate exposure. It is sensible to think that real exposure will very likely be lower than registered. In the clinical records included in the BIFAP database, x-ray images are not available, which might occasionally lead to misclassification of cases. However, we believe that this may not be a relevant limitation; yet hip-fracture cases are described in detail in the surgical procedures.

Another aspect to be pointed out is that ibandronate was marketed in Spain in January 2007, and in our study we included incident cases of hip fracture that occurred between 2005 and 2008. Thereby, the exposure of both cases and controls to ibandronate is rather short term.

Confounding by indication is a possible bias of this study. Theoretically, women in a poor baseline condition could be prescribed bisphosphonates to a greater extent when compared to women with a better health status. In order to minimise this bias, results were adjusted for previous fractures, comorbidities and use of other medications.

Bone mineral density (BMD) determination is not a standard test available in the public health system in Spain. Thereby, information on BMD in clinical records was rather scarce. However, this test has a very poor fracture risk predictive value and its clinical relevance can be challenged. When it comes to adjusting crude data, we used other bone-related variables instead, such as the prevalence of previous fractures.

In our study, no information on vitamin D plasma levels in our patients was available. However, we believe that this does not pose any problem since patients were not institutionalised, and in Spain the exposure to sunlight is sufficient to ensure adequate levels of vitamin D. Furthermore, almost 90% of women aged 65 or older take supplements of calcium plus vitamin D.22

Conclusions

Ever use of oral bisphosphonates was not associated with a decreased risk of hip fracture in women aged 65 or older as compared to never use. No association was observed between hip-fracture risk and cumulative duration of bisphosphonate treatment. However, when treatment duration is analysed as time since first prescription, a statistically significantly increased risk for hip fracture was observed in patients exposed to bisphosphonates over 3 years.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the collaboration of general practitioners contributing to BIFAP.

Footnotes

Contributors: JE, AA, JG and AL were responsible for developing the study concept and design, data validation and interpretation of the results. AA performed the statistical analyses. JE drafted the manuscript. All authors have been involved in revising and elaborating it critically in the intellectual context. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The present study is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health, grant SAS/2481/2009 no TRA-071.

Competing interests: The Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) provided the crude data from BIFAP to the researchers according to an agreement with the Health Department of Navarre Government but did not take part in the design or in the study development. Authors are fully responsible for the analysis, results and opinions appearing in the paper and do not represent the position of the AEMPS. The views expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the position of their respective institutions.

Ethics approval: Navarre Research Ethics Board, Pamplona, Spain.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet 1996;348:1535–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson D, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures. Results from the fracture intervention trial. JAMA 1998;280:2077–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liberman UA, Weiss SR, Broll J, et al. Effects of oral alendronate on bone mineral density and the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1437–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone HG, Downs RW, Tucci JR, et al. Dose-response relationships for alendronate treatment in osteoporotic elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:265–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reginster JY, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, et al. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2000;11:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genent HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and non-vertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;282:1344–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. N Engl J Med 2001;344:333–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chesnut CH, Skag A, Christiansen C, et al. Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:1241–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erviti J. Bisphosphonates: do they prevent or cause bone fractures? Drug Ther Bull 2009;17:65–75 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Therapeutics initiative A systematic review of the efficacy of bisphosphonates. Ther Lett 2011;83:1–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment. The Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA 2006;296:2927–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erviti J, Gorricho J. Use of alendronate after 5 years of treatment (letter). JAMA 2007;297:1979–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CHMP assessment report on bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. EMEA/CHMP/291125/2009. http://www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2010/01/WC500051428.pdf (accessed 2 Aug 2012)

- 14.FDA Drug Safety Communication: ongoing safety review of oral bisphosphonates and atypical subtrochanteric femur fractures. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2010/ucm229171.htm (accessed 2 Aug 2012)

- 15.Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: a register-based national cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:1095–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Cumulative alendronate dose and the long-term absolute risk of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures: a register-based National cohort analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:5258–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvador JC, Moreno D, Sonego LA, et al. El Proyecto BIFAP: Base de datos para la Investigación. Aten Primaria 2002;30:655–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Proyecto BIFAP http://www.bifap.org/summary.php (accessed 22 Aug 2012)

- 19.Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, et al. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Where do we go from here? N Engl J Med 2012;366:2048–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlad SC, Zhu Y, Niu J, et al. Bisphosphonate use may be a risk factor for osteonecrosis at any site: a self-controlled case series analysis [abstract]. 27th ICPE: International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management. Chicago, 2011;[274] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, et al. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:1294–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garjón Javier J. Calcium supplements: are we doing it right? DTB Navarre 2012;20(3):1–12 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.