Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the reliability and agreement of digital tender point (TP) examination in chronic low back pain (LBP) patients.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Settings

Hospital-based validation study.

Participants

Among sick-listed LBP patients referred from general practitioners for low back examination and return-to-work intervention, 43 and 39 patients, respectively (18 women, 46%) entered and completed the study.

Main outcome measures

The reliability was estimated by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and agreement was calculated for up to ±3 TPs. Furthermore, the smallest detectable difference was calculated.

Results

TP examination was performed twice by two consultants in rheumatology and rehabilitation at 20 min intervals and repeated 1 week later. Intrarater reliability in the more and less experienced rater was ICC 0.84 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.98) and 0.72 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.95), respectively. The figures for inter-rater reliability were intermediate between these figures. In more than 70% of the cases, the raters agreed within ±3 TPs in both men and women and between test days. The smallest detectable difference between raters was 5, and for the more and less experienced rater it was 4 and 6 TPs, respectively.

Conclusions

The reliability of digital TP examination ranged from acceptable to excellent, and agreement was good in both men and women. The smallest detectable differences varied from 4 to 6 TPs. Thus, TP examination in our hands was a reliable but not precise instrument. Digital TP examination may be useful in daily clinical practice, but regular use and training sessions are required to secure quality of testing.

Keywords: Rheumatology, Statistics & Research Methods, Pain Management

Article summary.

Article focus

Diffuse hyperalgesia may be evaluated by tender point (TP) examination and may reflect deficient descending pain inhibition as in fibromyalgia.

TP examination is increasingly relevant to improve clinical assessment in inflammatory as well as non-inflammatory rheumatological disorders.

Reproducibility of this examination technique is not well documented and was therefore investigated.

Key messages

In sick-listed chronic low back pain (LBP) patients, digital TP examination was a reliable but not precise instrument.

In both women and men, there was more than 70% agreement within ±3 TPs.

The method was quick and easy to use with no requirements of equipment, except in initial training sessions.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study included a well-defined chronic LBP population that was referred from general practitioners for LBP examination and return-to-work intervention.

The number of patients was limited and only two raters were involved, resulting in wide CIs and limited generalisability.

Introduction

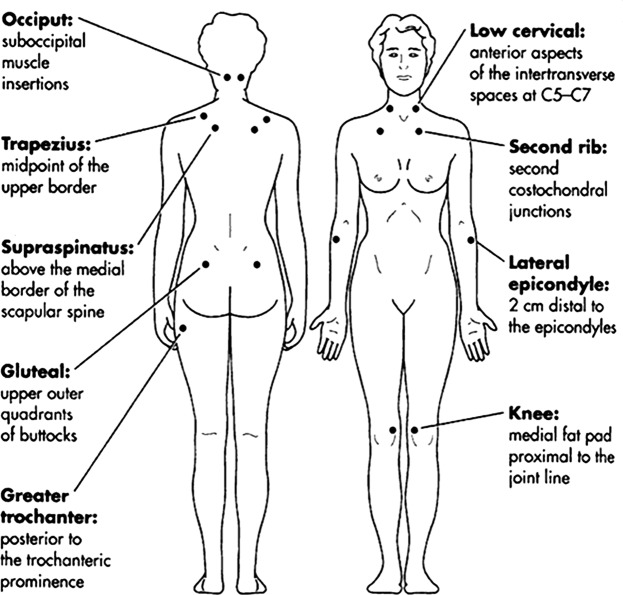

Tender point (TP) examination has been the cornerstone examination in patients with chronic widespread pain (CWP) to distinguish fibromyalgia patients from patients with CWP only. In the general population, the former and latter conditions have been identified in 0.5–4%1 and 10–13%,2 3 respectively. Persons fulfilling the fibromyalgia criteria (CWP and ≥11 TPs) report more pain and disability than persons with CWP who have less than 11 TPs.4 TP examination is performed by standardised digital palpation at 18 points symmetrically distributed on the body (figure 1).5 In the general population, men and women had a median of 3 and 6 TPs, respectively,6 and women may have up to 4 TPs more than men.7

Figure 1.

Locations of tender points according to the American College of Rheumatology.5

TP examination may be relevant in conditions other than CWP or regional pain syndromes. In inflammatory rheumatic diseases, TP examination may also contribute to the clinical evaluation. For instance, high-disease activity in the absence of inflammatory activity in rheumatoid arthritis is often seen in patients with many TPs.8 This may lead to inappropriate treatment of disease activity. In systemic lupus erythematosus, health status has been shown to be inferior in patients with many TPs as compared with patients with few TPs.9

In sick-listed low back pain (LBP) patients, the intensity of back pain is associated with the number of TPs, and patients with radiculopathy have fewer TPs than patients with non-specific LBP.10 Furthermore, TPs are associated with the reporting of widespread pain and with long-term prognosis.11 According to another study,12 patients with both CWP and non-specific LBP have more pain, higher disability and more TPs than patients with LBP only.

Reliability and agreement studies are, however, few and insufficient. The original study defining fibromyalgia5 included 293 patients and 265 controls. Since then, we have been able to identify only three small studies comparing the reliability of digital palpation and dolometry with TPs defined as in the original study.13–15 Each study included 15–25 individuals. The reliability was acceptable and comparable for both dolorimetry and digital palpation, and κ values of 0.44–0.92 were reported for the digital examination. However, only the reliability of testing each TP location as positive was estimated, not the reliability of the total TP counts. In other non-specific pain studies, the reliability of TP examination was not formally tested, or digital examination was not used.16–20

Since the total TP count—and not each single TP—is used for the clinical evaluation in rheumatological conditions, more reliability and agreement studies of the total TP count are needed.

Accordingly, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the reproducibility of total TP counts based on digital TP examination in chronic sick-listed LBP patients in terms of (1) intrarater and inter-rater reliability and (2) intrarater and inter-rater agreement.

Methods

The patients were recruited among patients referred from their general practitioners to the Spine Center for participation in a controlled study.

Inclusion criteria: partly or fully sick-listed for more than 4 weeks due to LBP with or without radiculopathy, LBP should be the prime reason for sick-listing and at least as bothersome as pain elsewhere, age 16–60 years, referred from a well-defined geographical area of about 280 000 inhabitants, and the patient should be able to speak and understand Danish.

Exclusion criteria: living outside the referral area, continuing or progressive radiculopathy resulting in plans for surgery, low back surgery within the last year, previous lumbar fusion operation, suspected cauda equina syndrome, progressive paresis or other serious back disease, (eg, tumour), pregnancy, known dependency on drugs or alcohol or primary psychiatric disease.

The patients were contacted between 1 November 2009 and 1 March 2010 and were only included in the present study after more than 3 weeks had passed since their first consultation at the Spine Center. They were offered participation in the study by one of the authors (JC), who was the leader of the project but was not a staff member, and they were told that the investigation had nothing to do with the management of their LBP. The patients were informed that the examination would only include measuring of diffuse tenderness by TP examination and spinal range of motion (not reported in this paper). Previously, all patients had been subjected to a clinical low back examination and TP examination at their first consultation at the Spine Center.

The examinations were performed by two clinicians (OKJ and MGN), both consultants in rheumatology and rehabilitation. Beforehand, the TP examination method was taught by the more experienced rater (OKJ=Rater A) to the less experienced rater (MGN=Rater B) during a 2 h session. Each test day, before starting examinations, the two raters calibrated their thumbs with a dolorimeter,21 which was able to register four pressures at a time and calculate means and SDs.

The examinations were performed during two test days, days 1 and 2, at 1-week intervals. To include all patients, the test days were repeated twice. The patients were randomised so that half of the patients were first tested by Rater A, the other half first by Rater B, but keeping the same sequence on day 2 as on day 1. Twenty minutes passed between the examinations.

Before examination, the patients filled out a questionnaire including questions regarding back+leg pain22 and disability,23 increasing scores representing increasing pain and disability. At the clinical examination, the patient's range of spinal motion was first measured in the standing position. Subsequently, the patient was asked to lie prone, and a 4 kg digital pressure was demonstrated on the distal, dorsal aspect of the forearm. The patient was instructed in the following way: “This is a firm pressure. Afterwards, this pressure will be applied on different spots on the body. At every spot, I would like you to report if the pressure is painful or is felt like firm pressure.” The TPs (figure 1) were tested in a standardised manner from right to left, first testing the medial fat pads of the knees and the posterior aspects of the greater trochanter. Afterwards, with the patient seated, the spots were tested from the top and downwards as follows: the suboccipital muscle insertions, the anterior-lateral aspect of the intertransverse aspects of C5–7, the midpoints of the upper borders of the trapezius, the medial parts of the supraspinatus, the costochondral junctions of costa 2, the forearm 2 cm distal to the epicondyles and the outer upper quadrants of the buttocks. The patients were instructed not to tell the result of the TP examination to the raters or others.

Positive TPs (eg, pressures causing pain) were memorised by the raters and summed up to the total number of TPs (the TP count). The procedure lasted 6–8 min per examination. A secretary was associated with each rater. The TP counts were reported to this secretary, who passed the data to the project leader (JC). In this way, the raters were blinded in relation to each other.

The secretary also registered pain response at every single TP location.

Statistical analyses

The requirement for testing intrarater and inter-rater reliability was planned to include a sample size of at least 40 persons.24 The TP counts were distributed as discrete numerical variables and were normally distributed. For the quantification of intrarater and inter-rater reproducibility of TP examination, two types of analysis were applied: the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the Bland-Altman method for assessing agreement.25 26 ICC provides information on the ability to differentiate between the variation between subjects and measurement variation. The ICC was defined as the ratio of variance among patients (subject variability) over the total variance (subject variability, observer variability and measurement variability). ICC ranges between 0 (no reliability) and 1 (perfect reliability), and values of ICCs are excellent when >0.75 and poor when <0.40. Results between these ranges represent moderate-to-good reliability.27 According to another reference, ICC >0.7 is considered good.25

The Bland-Altman method provides insight into the distribution of differences in relation to mean values.28 Agreement was quantified by calculating the mean difference between two sets of observations and the SD for this difference. The closer the mean difference was to 0 and the smaller the SD of this difference, the better was the agreement. The differences were depicted in relation to the mean values. The 95% limits of agreement were defined as the mean difference between the raters ±1.96 × SDof the difference. Furthermore, agreement within ±1 TPs and ±3 TPs was calculated.

To determine whether a real change in outcome has occurred in clinical practice and research, a change must be at least the smallest detectable difference (SDD) of a measurement procedure.25 The SDD was calculated as 1.96 × √(2 × SEM2), where the SE of measurement (SEM) was defined as SDof the difference/√2. SDD was calculated and rounded up to the nearest whole number.

Cronbach's α is a measure of internal consistency indicating if different items of a test battery are intercorrelated and measure the same construct. Values >0.9 are considered excellent.

The reliability of each TP location was measured by κ statistics.

Results

Eighty-three patients were invited to join the study, and 39 patients completed both test days (figure 2). Four patients dropped out from days 1 to 2, three without explanation, and the fourth was excluded because of hospital admission and change of pain medication between the two test days. Pain medication was unchanged in the other patients.

Figure 2.

Flow chart.

Baseline characteristics are displayed in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Sex (men/women) | 21/18 |

| Age (mean, range) | 42.0 (24–58) |

| Back+leg pain (0–60, median, range) | 22 (2–50) |

| Disability (0–23, median, range) | 14 (0–23) |

| Tender points* (0–18, median, range) | 8 (0–18) |

| Duration of pain (n, %) | |

| 3–6 months | 13 (33) |

| 7–12 | 12 (31) |

| >12 | 14 (36) |

Back+leg pain measured as the sum of worst, average and actual pain.

Disability estimated by the Roland Morris Questionnaire, and tender points estimated by standardised digital palpation.

*Median tender points of Observer A on day 1: men 5, women 10.5.

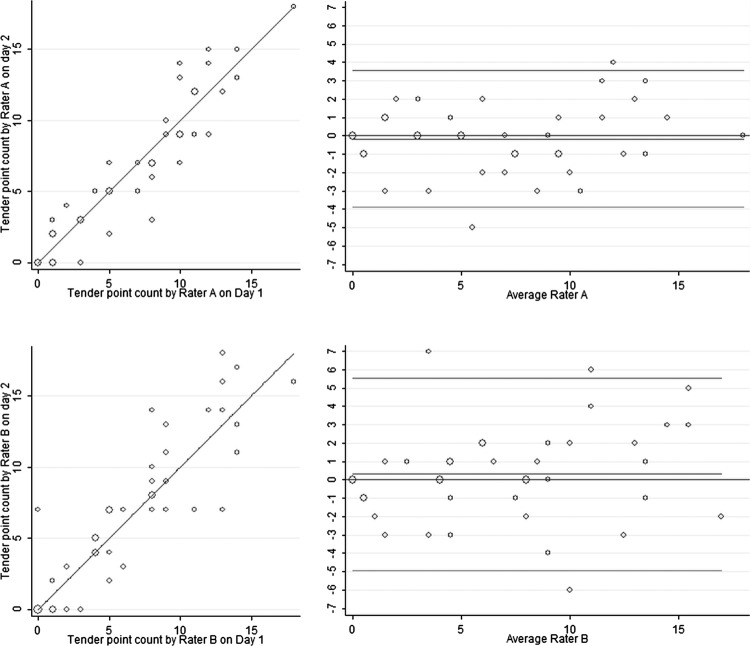

Intrarater reliability and agreement

The mean TP count was seven and differed little between test days (table 2). The ICC in Rater A was excellent, 0.83 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.98), reflecting a high degree of reliability. ICC was somewhat lower, but still good in Rater B, 0.72 (CI 0.49 to 0.95). The relations between TP counts on days 1 and 2 are graphically displayed in figure 3 (left panel). The circles representing more than one observation were all located near the equality lines, and the observations were distributed over the whole range of TP counts.

Table 2.

Intrarater differences, reliability and agreement

| Day 1 mean (SD) | Day 2 mean (SD) | Intraobserver difference mean (SD) | Intraclass correlation coefficient (CI) | Agreement (%) |

Limits of agreement | SDD* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ±1 TP all men women | ±3 TP all men women | |||||||

| Observer A | 7.23 (4.61) | 7.08 (4.95) | −0.15 (1.90) | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.98) | 62 | 95 | −3.65; 3.95 | 4 |

| 62 | 90 | |||||||

| 61 | 100 | |||||||

| Observer B | 7.10 (4.73) | 7.41 (5.78) | 0.31 (2.68) | 0.72 (0.49 to 0.95) | 49 | 85 | −5.05; 5.66 | 6 |

| 62 | 90 | |||||||

| 33 | 78 | |||||||

Reliability estimated by the intraclass correlation coefficient.

*Smallest detectable difference.

SDD, smallest detectable difference; TP, tender points.

Figure 3.

Intrarater reliability and agreement. Reliability with lines of equality shown in the left panel. Agreement shown by Bland-Altman plots in the right panel displaying differences of tender point (TP) counts on the y-axis and average of TP counts on the x-axis. The upper and the lower horizontal lines represent 95% limits of agreement. Areas of the circles are proportional to the number of observations.

In about half of the observations, agreement was within ±1 TP. For both raters, more than 75% of the TP counts were within ±3 TPs in both sexes. The limits of agreement were within ±4 and ±6 TPs for Rater A and Rater B, respectively (figure 3 right panel), corresponding to the SDD (table 2). Measurement errors (SEM) were 1.34 (1.90/√2) and 1.89 (2.68/√2) for Rater A and Rater B, respectively. Cronbach's α was 0.96 and 0.92 for Rater A and B, respectively.

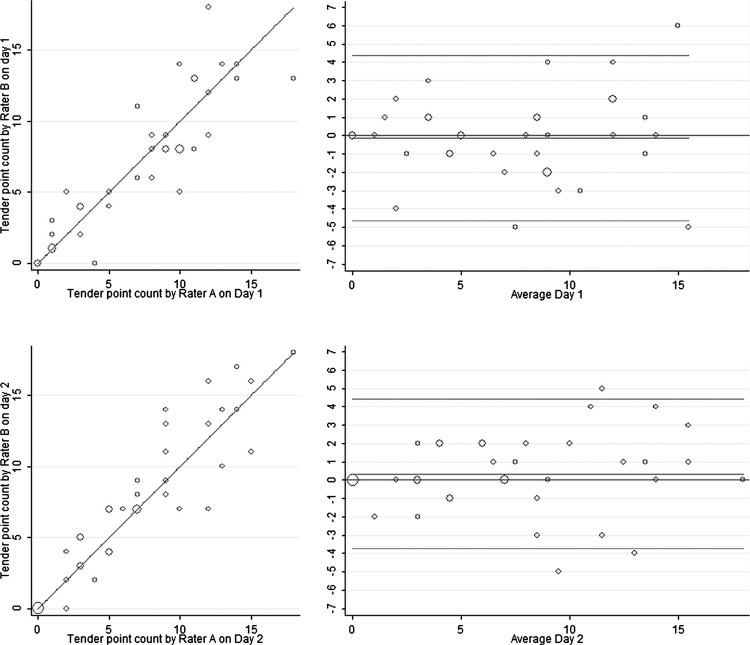

Inter-rater reliability and agreement

The mean differences of TP counts differed little between the two raters (table 3). The relations between TP counts of Raters A and B are shown in figure 4, left panel, and the limits of agreement in the right panel. The circles representing more than one observation were all located near the equality and zero lines. On both test days, ICC was higher than 0.75. In more than 70% of the cases, Rater B agreed with Rater A regarding ±3 TPs in both men and women. The limits of agreement were within ±5 TPs, corresponding to SDD of 5 TPs. measurement errors (SEM) were 1.63 (2.30/√2) and 1.47 (2.08/√2) on days 1 and 2, respectively. Cronbach's α was 0.94 and 0.96 on days 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 3.

Interrater differences, reliability and agreement

| Observer A mean (SD) | Observer B mean (SD) | Interobserver difference mean (SD) | Intraclass correlation coefficient (CI) | Agreement (%) |

Limits of agreement | SDD* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ±1 TP all men women | ±3 TP all men women | |||||||

| Day 1 | 7.23 (4.61) | 7.10 (4.73) | −0.13 (2.30) | 0.77 (0.58 to 0.97) | 59 | 85 | −4.64; 4.72 | 5 |

| 67 | 95 | |||||||

| 50 | 72 | |||||||

| Day 2 | 7.08 (4.95) | 7.41 (5.78) | 0.33 (2.08) | 0.84 (0.70 to 0.99) | 56 | 87 | −3.83; 4.50 | 5 |

| 57 | 90 | |||||||

| 56 | 83 | |||||||

Reliability estimated by the intraclass correlation coefficient.

*Smallest detectable difference.

SDD, smallest detectable difference; TP, tender points.

Figure 4.

Inter-rater reliability and agreement. Reliability with lines of equality shown in the left panel. Agreement shown by Bland-Altman plots in the right panel displaying differences of tender point (TP) counts on the y-axis and the average of TP counts on the x-axis. The upper and the lower horizontal lines represent 95% limits of agreement. Areas of the circles are proportional to the number of observations.

Reliability of testing each TP location

In the appendix is shown the reliability of testing each TP location. Agreement varied from 69% to 90%, and κ values varied from 0.13 to 0.89.

Discussion

The present study showed that digital TP examination resulted in total TP counts with acceptable-to-excellent reliability when calibration of the thumbs with a dolorimeter was performed before the testing. This indicated that the measurement error, which was less than 2 TPs, was considerably smaller than the variation between individuals. The lesser experienced Rater B did not perform as well as the more experienced Rater A, and this was especially evident on comparison of the lower limits of the CIs. However, the reliability of Rater B was acceptable, but more training and regular use would probably improve the results. Training has been shown to reduce the variability in applying a 4 kg digital force.29

Agreement is independent of the variation between subjects. We consider an agreement of more than 70% as good, and it was found for ±3 TPs in both men and women, indicating that digital TP examination in daily practice may be used, keeping in mind the uncertainty of ±3 TPs. This part of the result was especially important, since we found that TP counts were higher in women than in men, in line with other studies. In the general population, TP counts of more than 10 and 6 have been identified in 10–20% of women and men, respectively.6 7 Thus, a TP count of 9 may be normal in women, but high in men.

The median TP count of 8 was elevated as compared with the median TP count in the general population, which is between 3 and 6 TPs.6 Previously, it has been shown that TP counts were elevated in regional pain conditions as compared with pain-free controls, but lower than in fibromyalgia.30

However, SDD ranged from 4 to 6, indicating less precision of TP examination than reliability. Thus, according to the present study, TP examination may result in TP counts that may differentiate between high, intermediate or low levels, but not between different levels in the low or high range. Moreover, TP examination—as used in the present study—would not be sufficiently precise to differentiate between patients with higher or lower TP counts than 10/11 TPs such as are used in the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.

Accordingly, an SDD of 4–6 was not impressive, but it was not so different from other measures in LBP. The minimal detectable change, which is defined closely to SDD,25 31 has been shown to be 4–5 points in the Roland Morris Questionnaire,32 a commonly used instrument in LBP.

In fibromyalgia, the peripheral sensory thresholds are normal, but pain processing is augmented, primarily due to dysfunction of the descending pain inhibition system in the brainstem.33 In the present study, the patients were sick-listed because of chronic LBP, and we have previously presented data making it plausible that LBP can partly be explained by mechanisms similar to those seen in fibromyalgia patients.10

We found high internal consistency, as all of Cronbach's α values were above 0.90. This may support the assumption that TP counts measure the same construct, that is, insufficient pain inhibition, rather than local abnormality. Therefore, in chronic LBP patients, TPs may be interpreted as follows: a high TP count may indicate an insufficiently functioning descending pain inhibition system, whereas a low TP count may indicate a well-functioning system. TP counts in the middle of the distribution are inconclusive. The present study does not provide sufficient data to set limits for high or low TP counts in LBP patients.

In the present chronic LBP population, there was no significant change in TP counts during 1 week. We could have chosen a shorter or longer interval, but 1 week was chosen for pragmatic reasons, because we assumed that 1 week would not be too long in a patient population with long-lasting pain. One might expect more change in TP counts during 1 week in patients with acute LBP. A systematic difference in TP count between the first and second TP examinations might have occurred, but such a potential difference was not apparent because the raters were randomised to be either the first or second rater.

The value of TP examination has been questioned. First, the examination method may be unreliable, because the pain response may be affected by expectations1 or distress.34 When the examination is performed randomly with the patient blinded for the pressure gradient, the results are different as compared with non-blinded testing.34 35 Second, it may be inadequate to use a sharp cut-point (≥11 TPs) to distinguish health from disease in pain conditions.36 At present, fibromyalgia is considered part of a larger continuum.37 38 Third, there have been problems with implementation of the examination technique, especially in primary care. Often, it has been incorrectly performed, and some physicians have refused to use the method.39

Therefore, new criteria for diagnosing fibromyalgia have been developed and validated. These criteria do not include TP examination, and therefore they will enable clinicians and researchers to diagnose fibromyalgia by surveys. However, the new criteria were not meant to replace the original American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria, but to represent an alternative method of diagnosis39; and the new criteria have not been tested in rheumatic conditions and may not be relevant in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. In these conditions, fibromyalgia symptoms may be caused by rheumatic disease and not by dysfunction of the descending pain inhibition system. Therefore, TP examination will still be relevant both at present and in the future.

The reliability of testing each TP location was not different from previous reporting in the literature.13–15

Strengths

The present study was conducted in a well-defined population recruited by general practitioners on the basis of sick-listing due to LBP, and all had chronic LBP. TPs were normally distributed, making it possible to analyse data with parametric methods.

Weaknesses

The number of patients was small, resulting in wide CIs of ICC, and only two raters participated. If more raters had participated, the results would have been more generalisable.

Perspectives

The possible advantages of using TP examination in LBP patients include ease and speed, no requirements of equipment and good reliability and agreement. Furthermore, malingering or appealing distress will probably not induce bias in LBP patients, who do not know what to prefer, many or few TPs.

The possible disadvantages include lack of precision and the need for training and equipment (dolorimeter).

We need to know more about the variability of the TP count over time, and we need reproducibility studies comparing TP counts with other measures of dysfunction of the descending pain-inhibiting system.37 As an example, lack of cold tolerance has been documented in whiplash patients with prolonged symptoms.40 TP counts may be compared with cold tolerance.

Furthermore, it would be interesting to see reliability and agreement studies of the total TP count in fibromyalgia patients and patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Findings resembling the results of the present study may have implications for the fibromyalgia criteria.

Conclusion

Digital TP examination in sick-listed chronic LBP patients was a reliable but not precise instrument. More reliability and agreement studies are needed in LBP patients and other populations, including patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Senior Biostatistician Robin Christensen, MSc, PhD, Head of the Musculoskeletal Statistics Unit, The Parker Institute, Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark, for invaluable help with the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Contributors: JC, OKJ and TE planned the study. JC designed the study in detail and was responsible for acquisition of data and obtaining funding. MGN and OKJ performed the clinical examinations. JC and OKJ were responsible for analysing and interpreting the data. OKJ wrote the manuscript, which was again revised by JC, TE and MGN. OKJ was responsible for administrative and technical support. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by The Research Fund of Regional Hospital Silkeborg, Denmark.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: All patients signed informed consent. The study was reported to the Regional Ethics Committee, who answered that approval was not necessary because only methodology was studied. The study was reported to the Danish Data Protection Agency (No. 2007-58-0010).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Clauw DJ, Crofford LJ. Chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia: what we know, and what we need to know. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003;17:685–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macfarlane GJ, Pye SR, Finn JD, et al. Investigating the determinants of international differences in the prevalence of chronic widespread pain: evidence from the European Male Ageing Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:690–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergman S, Herrstrom P, Hogstrom K, et al. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1369–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coster L, Kendall S, Gerdle B, et al. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain—a comparison of those who meet criteria for fibromyalgia and those who do not. Eur J Pain 2008;12:600–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft P, Schollum J, Silman A. Population study of tender point counts and pain as evidence of fibromyalgia. BMJ 1994;309:696–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, et al. Aspects of fibromyalgia in the general population: sex, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia symptoms. J Rheumatol 1995;22:151–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ton E, Bakker MF, Verstappen SM, et al. Look beyond the disease activity score of 28 joints (DAS28): tender points influence the DAS28 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2012;39:22–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akkasilpa S, Goldman D, Magder LS, et al. Number of fibromyalgia tender points is associated with health status in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2005;32:48–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen OK, Nielsen CV, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Low back pain may be caused by disturbed pain regulation: a cross-sectional study in low back pain patients using tender point examination. Eur J Pain 2010;14:514–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen OK, Nielsen CV, Stengaard-Pedersen K. One-year prognosis in sick-listed low back pain patients with and without radiculopathy. Prognostic factors influencing pain and disability. Spine J 2010;10:659–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordeman L, Gunnarsson R, Mannerkorpi K. Prevalence and characteristics of widespread pain in female primary health care patients with chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain 2012;28:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cott A, Parkinson W, Bell MJ, et al. Interrater reliability of the tender point criterion for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 1992;19:1955–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunks E, McCain GA, Hart LE, et al. The reliability of examination for tenderness in patients with myofascial pain, chronic fibromyalgia and controls. J Rheumatol 1995;22:944–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen JO, Smidth M, Hansen TM. Examination of tender points in soft tissue. Palpation versus pressure-algometer. Ugeskr Laeger 1990;152:1522–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maquet D, Croisier JL, Demoulin C, et al. Pressure pain thresholds of tender point sites in patients with fibromyalgia and in healthy controls. Eur J Pain 2004;8:111–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McVeigh JG, Finch MB, Hurley DA, et al. Tender point count and total myalgic score in fibromyalgia: changes over a 28-day period. Rheumatol Int 2007;27:1011–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tastekin N, Uzunca K, Sut N, et al. Discriminative value of tender points in fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain Med 2010;11:466–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tastekin N, Birtane M, Uzunca K. Which of the three different tender points assessment methods is more useful for predicting the severity of fibromyalgia syndrome? Rheumatol . Int 2007;27:447–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harden RN, Revivo G, Song S, et al. A critical analysis of the tender points in fibromyalgia. Pain Med 2007;8:147–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Commander Algometry JTECH Medical. 470 Lawndale Drive, Salt Lake City, 84115 Utah, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manniche C, Asmussen K, Lauritsen B, et al. Low back pain rating scale: validation of a tool for assessment of low back pain. Pain 1994;57:317–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albert HB, Jensen AM, Dahl D, et al. Criteria validation of the Roland Morris questionnaire. A Danish translation of the international scale for the assessment of functional level in patients with low back pain and sciatica. Ugeskr Laeger 2003;165:1875–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopkins WG. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med 2000;30:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. When to use agreement versus reliability measures. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1033–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kottner J, Audige L, Brorson S, et al. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:661–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andresen EM. Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:S15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smythe H. Examination for tenderness: learning to use 4 kg force. J Rheumatol 1998;25:149–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granges G, Littlejohn G. Pressure pain threshold in pain-free subjects, in patients with chronic regional pain syndromes, and in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:642–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stauffer ME, Taylor SD, Watson DJ, et al. Definition of non-response to analgesic treatment of arthritic pain: an analytical literature review of the smallest detectable difference, the minimal detectable change, and the minimal clinically important difference on the pain visual analog scale. Int J Inflam 2011. Published online 5 May 2011 doi:10.4061/2011/231926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, et al. Defining the minimum level of detectable change for the Roland-Morris questionnaire. Phys Ther 1996;76:359–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen LA, Henriksson KG. Pathophysiological mechanisms in chronic musculoskeletal pain (fibromyalgia): the role of central and peripheral sensitization and pain disinhibition. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21:465–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petzke F, Gracely RH, Park KM, et al. What do tender points measure? Influence of distress on 4 measures of tenderness. J Rheumatol 2003;30:567–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris RE, Gracely RH, McLean SA, et al. Comparison of clinical and evoked pain measures in fibromyalgia. J Pain 2006;7:521–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe F. The relation between tender points and fibromyalgia symptom variables: evidence that fibromyalgia is not a discrete disorder in the clinic. Ann Rheum Dis 1997;56:268–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arendt-Nielsen L, Graven-Nielsen T. Central sensitization in fibromyalgia and other musculoskeletal disorders. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2003;7:355–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perrot S, Dickenson AH, Bennett RM. Fibromyalgia: harmonizing science with clinical practice considerations. Pain Pract 2008;8:177–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:600–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasch H, Qerama E, Bach FW, et al. Reduced cold pressor pain tolerance in non-recovered whiplash patients: a 1-year prospective study. Eur J Pain 2005;9:561–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.