Abstract

The antimicrobial peptide nisin shows potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria including the most prevalent implant-associated pathogens. Its mechanism of action minimizes the opportunity for the rise of resistant bacteria and it does not appear to be toxic to humans, suggesting good potential for its use in antibacterial coatings for selected medical devices. A more quantitative understanding of nisin loading and release from polyethylene oxide (PEO) brush layers will inform new strategies for drug storage and delivery, and in this work optical waveguide lightmode spectroscopy was used to record changes in adsorbed mass during cyclic adsorption-elution experiments with nisin, at uncoated and PEO-coated surfaces. PEO layers were prepared by radiolytic grafting of Pluronic® surfactant F108 or F68 to silanized silica surfaces, producing long- or short-chain PEO layers, respectively. Kinetic patterns were interpreted with reference to a model accounting for history-dependent adsorption, in order to evaluate rate constants for nisin adsorption and desorption, as well as the effect of pendant PEO on the lateral clustering behavior of nisin. Nisin adsorption was observed at the uncoated and F108-coated surfaces, but not at the F68-coated surfaces. Nisin showed greater resistance to elution by peptide-free buffer at the uncoated surface, and lateral rearrangement and clustering of adsorbed nisin was apparent only at the uncoated surface. We conclude peptide entrapment at the F108-coated surface is governed by a hydrophobic inner region of the PEO brush layer that is not sufficient for nisin entrapment in the case of the shorter PEO chains of the F68-coated surface.

Keywords: adsorption kinetics, history dependent model, nisin, PEO brush, peptide entrapment

Introduction

Nisin is a small (3.4 kDa) cationic, amphiphilic peptide that is an effective inhibitor of Gram positive bacteria [1]. Its potential use in anti-infective coating strategies has motivated interest in its adsorption and function at biomaterial interfaces. We have described nisin adsorption and various aspects of its behavior at PEO-coated surfaces through ellipsometry [2], circular dichroism and assays of antibacterial activity [3], zeta potential [4], and TOF-SIMS [5].

In this paper, optical waveguide lightmode spectroscopy (OWLS) was used to record changes in adsorbed mass during cyclic adsorption-elution experiments with nisin, at PEO layers prepared by covalent stabilization of Pluronic® surfactant F108 or F68 to silanized silica surfaces, producing long- or short-chain PEO layers, respectively. Kinetic patterns were interpreted with reference to a model accounting for history-dependent adsorption [6].

Materials and Methods

Solution preparation

Nisin (3510 Da) was obtained from Prime Pharma (Batch number 20050810, Gordons Bay, South Africa) and dissolved in 10 mM monobasic phosphate buffer (10 mM monobasic sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride). The pH was adjusted to 7.4 by dilution with dibasic phosphate buffer (10 mM dibasic sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride) to bring the final nisin concentration to 0.5 mg/mL. The solution was stirred overnight in a 37 °C incubator. Plasminogen-free human fibrinogen (340 kDa, 1 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) as needed. Prior to use, all protein solutions were drawn into sterile, disposable syringes and degassed for 1 h at 700 torr vacuum. All protein free PBS solutions were degassed in a sterile, disposable syringe at 700 torr vacuum for 4 h. The Pluronic® surfactants F108 (approximate composition EO141PO44EO141, HLB > 24) and F68 (approximate composition EO80PO27EO44, HLB > 24) were obtained from BASF (Mount Olive, NJ) and dissolved in PBS, each at 5% (w/v) as needed. All water used was HPLC grade.

Surface modification

OW 2400 waveguide sensors for use with OWLS instrumentation were purchased from MicroVacuum (Budapest, Hungary). A thin film of silica dioxide was applied by the manufacturer prior to purchase. Sensor cleaning consisted of submersion in chromosulfuric acid (Acros Organics, NJ) for 10 min, rinsing with HPLC grade water, and blow drying with dry nitrogen. Surface silanization was performed via vapor deposition with trichlorovinylsilane (TCVS, TCI America, Portland, OR). Silanization was carried out in a sealed vessel using dry argon as the carrier gas [7]. Cleaned OWLS sensors were arranged on the sample stage with the waveguides facing up. Dry argon was allowed to flow through the vapor deposition unit to equilibrate the internal environment and purge any atmospheric moisture. A 200 μL aliquot of TCVS was injected into the injection well and argon flow directed through the well to transport silane vapors into the main chamber. After 1 h, another 200 μL aliquot of TCVS was injected into the well. Argon flow was continued for an additional hour before bypassing the injection well. Argon was then passed through the main chamber for an additional 20 min to purge any unreacted silane vapors from the system.

Silanized waveguides were cured at 150 °C for 20 min to stabilize the newly formed vinyl layer. Each silanized and cured waveguide was incubated for a minimum of 12 h in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing the desired triblock solution. After incubation, these tubes were exposed to γ-radiation from a 60Co source (Oregon State University Radiation Center) for a total dose of 0.3 Mrad (6.5 hours) to achieve polymer grafting [8]. Sensors were then removed from incubation tubes, rinsed with PBS, dried with nitrogen, and stored in dry nitrogen filled microcentrifuge tubes until needed.

OWLS measurements

OWLS waveguides (with or without surface modifications) were immersed in PBS overnight prior to use in order to equilibrate their surface with the buffer [9]. The waveguide was then removed from solution and immediately installed in the OWLS flow cell (total volume 4.8 μL). Experiments were carried out in an OWLS 210 instrument controlled with BioSense 2.6 software (MicroVacuum, Budapest, Hungary). A Rheodyne manual sample injector (IDEX, Oak Harbor, WA) was used to inject protein samples through a flow loop (PEEK tubing, 2.3 mL approximate volume) to the OWLS flow cell. The flow rate was maintained at 50 μL/min in all experiments to ensure an injection residence time of at least 30 min in the flow cell. As refractive index measurements are highly sensitive to temperature variations, flow cell temperature was maintained at 20 °C by an internal OWLS TC heater/cooler unit. Incident angle scans were performed from −5° to 5° at a step size of 0.01°. All four peaks were measured (the characteristic transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM) peaks) to determine the relative refractive index of the surface adlayer. The OWLS instrument allows 4–10 peak scans per minute (depending on scanning speeds, peak ranges, and number of peaks used), which resulted in about 6 s being needed for determination of a single data point. Adsorbed mass versus time data were calculated from changes in the refractive index of the adlayer, applying the assumption that refractive index changes linearly with protein concentration [10].

Adsorption kinetics

Cyclic, adsorption-elution experiments were performed with each triblock surfactant (5% w/v), fibrinogen (1 mg/mL), or nisin (0.5 mg/mL). In each case, once loaded into the injection loop, about 6 mL of solution was passed through the loop to purge any remaining equilibration buffer. In the case of the triblocks, adsorption was performed for 30 min on a TCVS-treated sensor, immediately followed by a 30 min rinse with protein-free buffer in each cycle. In the case of fibrinogen, adsorption was performed for 10 min on triblock-coated and uncoated (TCVS-treated) sensors for the purpose of confirming the presence of protein-repellent PEO layers after grafting. Nisin adsorption was performed for 30 min, immediately followed by a 30 min rinse with protein-free buffer on uncoated, F108-coated, and F68-coated surfaces. This process was repeated two times during the course of one experiment.

Results and Discussion

Triblock adsorption

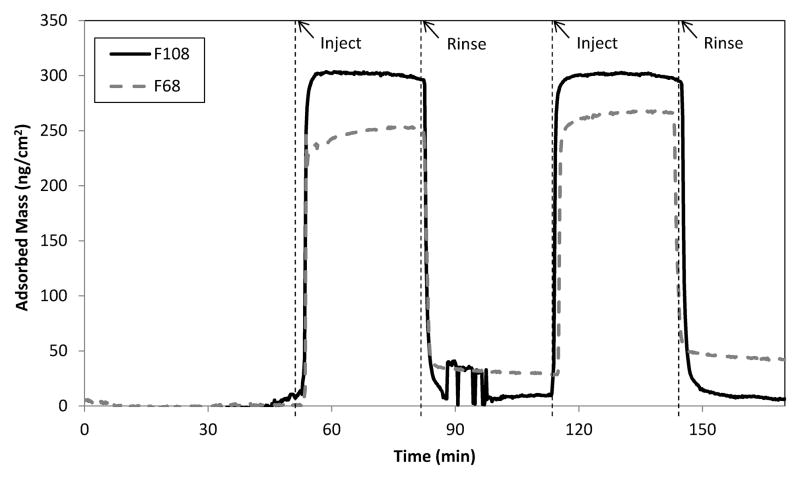

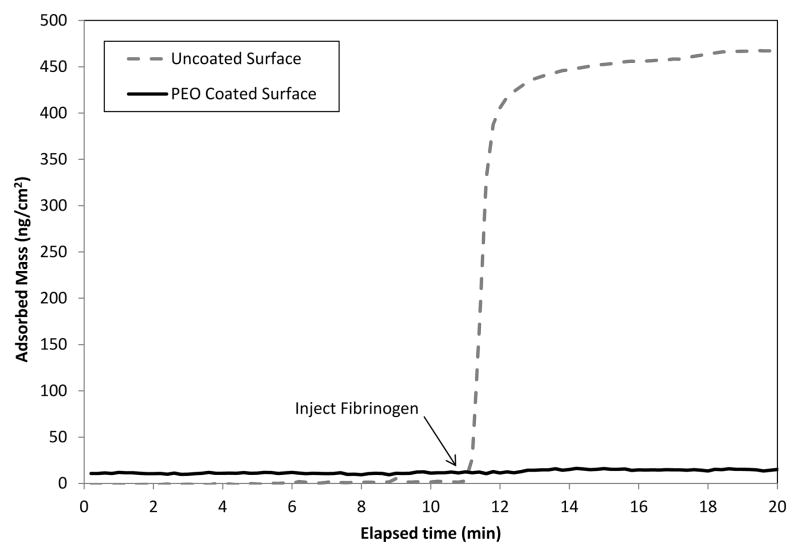

The Pluronic® surfactants F108 and F68 were adsorbed to silanized OWLS waveguides prior to covalent immobilization (while immersed in 5% triblock solution) through γ-irradiation. Figure 1 shows representative results of adsorption experiments performed on these waveguide sensors to confirm triblock association with the hydrophobic surface. Each triblock adsorbed rapidly to the hydrophobic surface of the waveguide, and adsorbed mass remained fairly constant over the 30 min adsorption cycle. Taking the plateau amounts of adsorbed triblock shown in Fig. 1 as an upper limit to estimate the PEO chain density at each surface, we would record 0.25 and 0.34 chains/nm2 in the case of F108 and F68, respectively. Formation of a less dense brush layer in the case of F108 is consistent with its longer PEO chains (about 141 repeat units vs. 80 for F68) as well as the larger footprint afforded by its PPO center block (about 44 repeat units vs. 27 for F68). This would constitute only a rough estimate, however, as it is difficult to know the orientation and association state of triblocks at the time of γ-irradiation. Instead, we verified adoption of a brush configuration in each case by fibrinogen repulsion (Fig. 2). PEO brush layers with good steric-repulsive function are expected to form at chain densities greater than about 0.2 chains/nm2 [11]. The nonfouling character of the PEO layers formed in this work was clearly evident upon introduction of human fibrinogen to uncoated and PEO-coated waveguide sensors (Fig. 2).

Fig 1.

Adsorption patterns recorded after exposure of TCVS-treated OWLS waveguides to a 5% F108 or F68 solution (in PBS), followed by elution in surfactant-free PBS.

Fig 2.

Representative plot of fibrinogen adsorption at an uncoated and PEO-coated surface.

Nisin adsorption

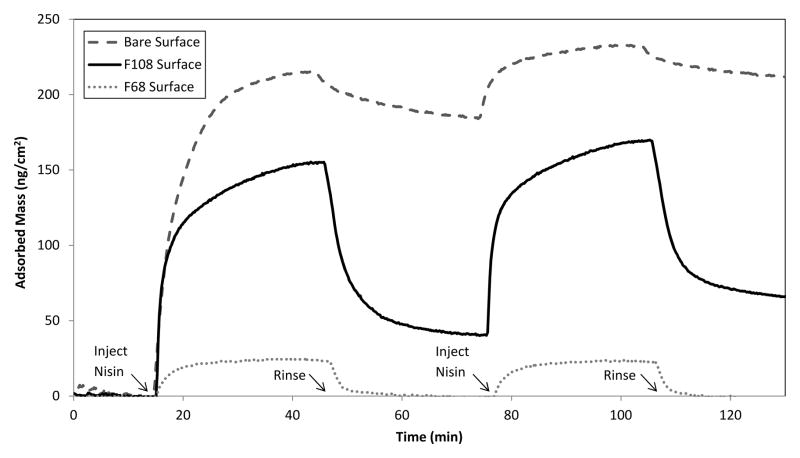

Representative results for nisin adsorption at uncoated, F108-coated, and F68-coated waveguides is shown in Fig. 3. The greatest extent of adsorption and greatest resistance to elution was recorded on the uncoated surface. While nisin adsorbed to the F108-coated surface with good affinity, it was substantially less resistant to elution. No appreciable adsorption of nisin was recorded at the F68 layer.

Fig 3.

Nisin adsorption at uncoated, F108-coated, and F68-coated waveguides.

While nisin apparently entered the F68 brush during the adsorption step, association with the surface and/or the surrounding PEO chains was not sufficient to retain the peptide during the rinse step. We note that while preparation of fibrinogen-repellent PEO layers based on F108 triblocks was straightforward, preparation of such layers based on F68 triblocks was not routinely successful. As a result nisin adsorption was recorded at F68 layers in some experiments, but fibrinogen adsorption was recorded in such cases as well. Analysis of these outcomes, to be discussed in a separate report, suggests that any nisin adsorption at an F68 layer is attributable to non-uniform brush formation, allowing direct contact and adsorption of the peptide at uncoated defect regions on the surface.

Visual inspection of history-dependent behavior

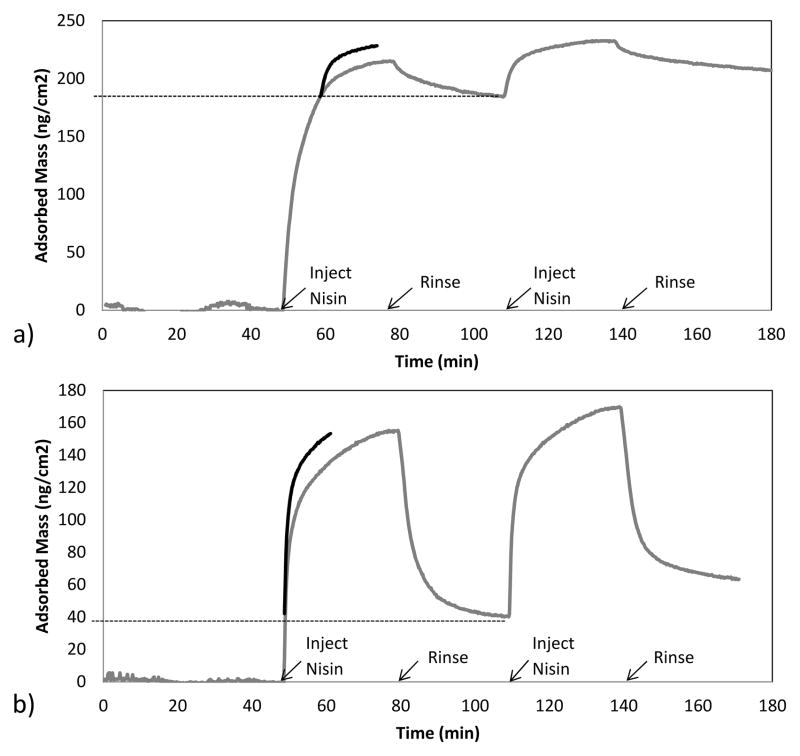

At a given surface loading, the rate of adsorption will depend on the formation history of the adsorbed layer. For example, adsorbed protein may rearrange laterally or “cluster” at the surface to form more ordered domains, in this way increasing the interfacial area available for incoming protein to adsorb without overlapping those previously adsorbed [6]. Such history dependent adsorption behavior has been recorded for a number of proteins at solid surfaces [2, 12–14]. The curves in Fig. 4a show that the initial adsorption rate during the second cycle was considerably greater than the adsorption rate at the uncoated hydrophobic surface, at the same surface coverage as during the first cycle. Based on its solution dimensions, a monolayer of nisin adsorbed “end-on” (occupying about 4 nm2/molecule) would be consistent with an adsorbed mass of about 145 ng/cm2 [15]. It is thus reasonable to suspect that an outer layer of adsorbed nisin, bound by its association with nisin molecules that are adsorbed in the primary layer, may participate in the lateral clustering giving rise to history dependent behavior at the uncoated surface.

Fig 4.

Nisin adsorption at (a) uncoated and (b) F108-coated waveguides. In each panel, the initial rate data in the second cycle is shifted back in order to allow comparison of adsorption rates at equal surface coverages in each cycle.

On the other hand the initial adsorption rate during the second cycle was similar to the adsorption rate at the same surface coverage during the first cycle in the case of adsorption to the F108 layer (Fig. 4b). This lack of history dependence might suggest inhibition of nisin clustering owing to the presence of the PEO chains. However theoretical and experimental evidence suggests that below the hydrophilic outer region of a PEO brush there exists a hydrophobic region that is favorable for protein adsorption [16, 17]. At the high chain concentrations consistent with brush formation, the specific configuration of the PEO that enables hydrophilic interaction with water becomes disrupted, rendering the pendant chains less soluble (or even insoluble) in water [18–20]. Recently, Lee et al. demonstrated that PEO chains are not hydrophilic when they are arranged in the brush configuration [21]. They found however that the brush layer hydrophobicity is not sufficient to overcome the PEO conformational entropy, consequently preventing collapse and preserving the widely observed steric-repulsive character.

The presence or absence of history dependent adsorption might indicate different adsorption mechanisms at play in each instance. Adsorption to the F108 layer may be best characterized by entrapment within the hydrophobic PEO phase, without contacting the underlying surface. Beyond some threshold concentration of peptide within this phase, its attractiveness for further protein adsorption may become compromised as interactions among PEO chains are disrupted or otherwise give way to PEO-peptide interactions. Peptides arriving after this threshold is reached could well be highly elutable. Certainly the lack of stable nisin adsorption recorded at the F68 layer also points to a lack of stable association between nisin and the underlying surface. We suggest nisin entrapment involves its location within the hydrophobic region of the immobilized PEO layer. While no evidence of stable association between nisin and the hydrophobic region of the F68 layer was recorded, this may be owing to the relatively short PEO chain length afforded by immobilized F68.

Comparison to a model

When a surface is exposed to a protein solution and the adsorption is kinetically limited, the rate of adsorption can be described by

| [1] |

where Γ is the adsorbed mass, t is time, ka is the intrinsic adsorption rate constant, Cb is the bulk concentration of the adsorbing molecules in solution, and kd,i and Γi are the desorption rate constant and the density of adsorbed molecules in the ith adsorption state [6]. Φ is the cavity function, dependent on different factors but conveniently considered to be the fraction of the surface where a molecule can adsorb without overlapping a previously adsorbed molecule. The term, , accounts for the influence of protein surface concentration on the adsorption rate, where −Ūs(Γ) is an average energy for the first adsorbates, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is temperature. Multiplying through by ,

| [2] |

where , which can be experimentally determined during the first adsorption cycle on an empty surface (i.e., at Γ = 0), and .

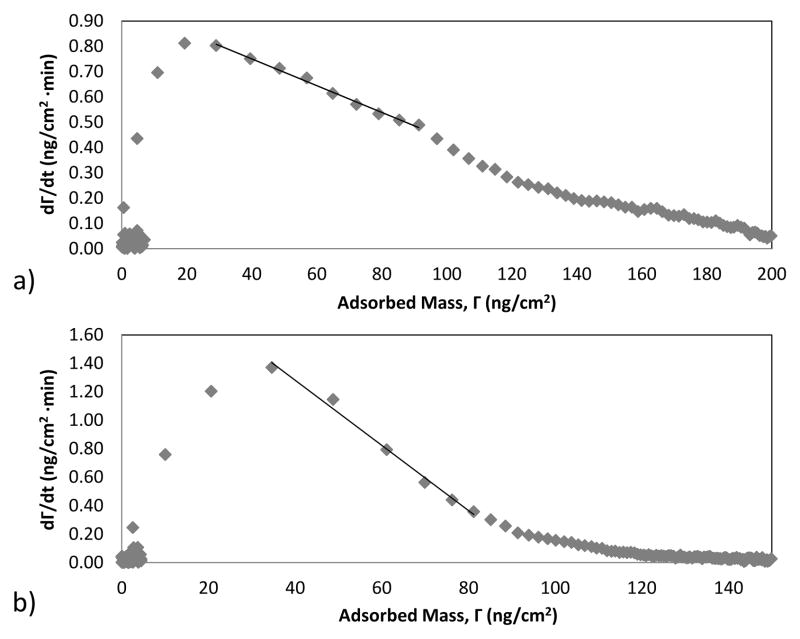

The data of Fig. 3 can be replotted as adsorption rate vs. adsorbed mass to determine the kinetic parameters in Eq. [2]. At Γ = 0, the modified cavity function, Φ′, is equal to 1, and Eq. [2] can be written as . Thus the y-intercept of the best fit lines in Fig. 5 may be used to determine an effective kC for each surface.

Fig 5.

The rate of adsorption versus the surface density for the first adsorption cycle of nisin at an (a) uncoated and (b) F108-coated surface. The solid line is a best fit to data in the linear, surface limited adsorption regime.

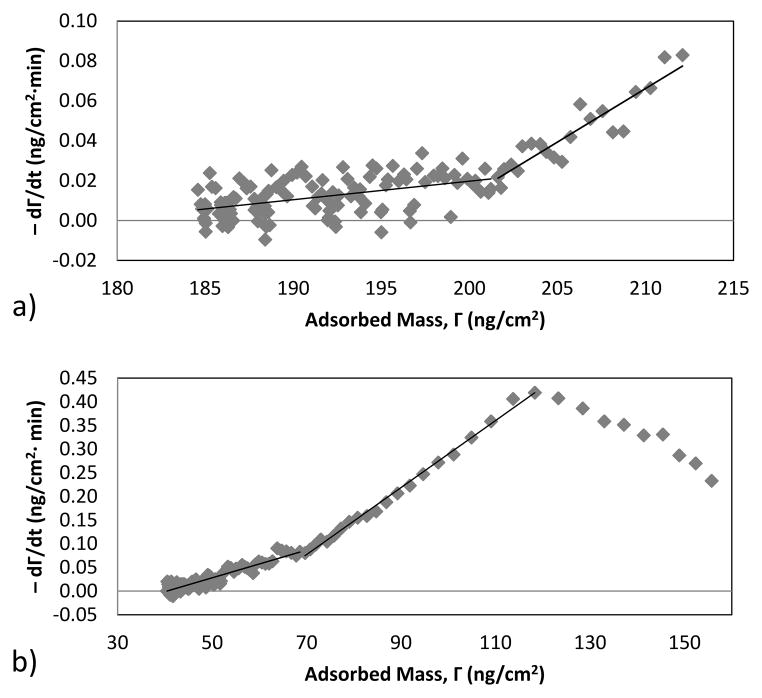

Desorption rate constants were determined in a similar fashion (Fig. 6). The two linear regions appearing in plots of adsorption rate vs. adsorbed mass indicate the presence of three adsorbed states: one that shows little resistance to elution (state 1), one with substantially greater resistance to elution (state 2), and one that is not elutable upon introduction of peptide-free buffer (state 3). During elution Eq. [2] can be written , as kd,3 = 0 initially. The slopes of the two distinct linear regions thus provide the desorption rate constants, kd,1 and kd,2.

Fig 6.

Negative desorption rate versus surface density for the first desorption cycle of nisin at an (a) uncoated and (b) F108-coated surface. The solid lines are best fits to two linear regions, used to determine desorption rate constants as well as adsorbed states and populations.

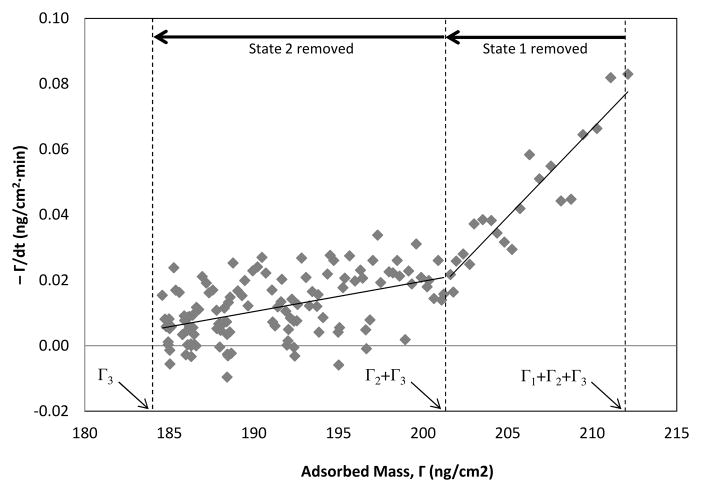

The populations of protein in states 1–3 at the end of the first adsorption cycle can also be determined from Fig. 6, recognizing that all states are present at the onset of desorption, only states 2 and 3 are present at the intersection of the two regions, and the intersection of the low surface concentration with the x-intercept, i.e., where , determines the adsorbed mass in state 3 (Fig. 7).

Fig 7.

Desorption rate versus surface density for an uncoated surface is shown as an example for desorption rate and population determination.

Once kC, and the kd,i and Γi have all been determined, Eq. [2] can be used to evaluate the modified cavity function at the onset of the second adsorption cycle for comparison to that at the same surface coverage during the first cycle, for each surface. At the onset of the second adsorption cycle, all protein is assumed to be “irreversibly” adsorbed (i.e. in state 3), and Φ′ can be determined at that point. Assuming that all protein is adsorbed in state 3 at the same surface coverage during the first cycle, i.e., that the first adsorbing proteins are those that are most stably adsorbed or entrapped, Φ′ can be determined at this point as well.

Table 1 lists kinetic parameters determined for the uncoated and F108-coated surfaces by the analysis summarized above. The uncoated surface showed history dependent adsorption, i.e., an increase in the modified cavity function between the first and second adsorption cycles, suggesting surface rearrangement of molecules (whether adsorbed in a primary or outer layer). The F108 surface however showed little change in the cavity function between adsorption cycles consistent with little evidence of history dependence. Adsorption into the F108 layer was also characterized by the highest initial adsorption rate (high kC), the highest elution rate (highest kd,i Γi) and the lowest value of Γ3 (least amount of stably bound protein).

Table 1.

Calculated kinetic parameters for uncoated and F108-coated surfaces. and refer to the modified cavity function at identical surface coverages during the first and second adsorption cycle, respectively.

| Parameter | Uncoated | F108-coated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| kC (ng/cm2·min) | 0.96 | 2.2 | |

| kd,1 (min−1) | 0.0054 | 0.0071 | |

| kd,2 (min−1) | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Γ1 (ng/cm2) | 10.5 | 85.6 | |

| Γ2 (ng/cm2) | 17.4 | 29.3 | |

| Γ3 (ng/cm2) | 184 | 40.4 | |

|

|

0.10 | 0.52 | |

|

|

0.27 | 0.59 |

Conclusions

Nisin adsorption to the uncoated surface showed history dependence while nisin adsorption to the F108-coated surface did not show history dependence. This was interpreted as lateral movement of peptide, whether in a primary or outer layer, resulting in cleared area for more rapid adsorption at the onset of the second cycle than recorded at the same surface coverage during the first cycle for the uncoated surface, and a lack of such rearrangement at the F108-coated surface. Nisin adsorption was not recorded at (fibrinogen-repellent) F68-coated surfaces. The lack of history dependence and high elutability characterizing nisin adsorption to the F108 layer, and the obvious lack of nisin association with the underlying surface or with the surrounding PEO chains at F68-coated surfaces, suggest nisin entrapment involves its location within the hydrophobic phase of immobilized PEO, without contacting the underlying surface. While nisin entry into the F68 brush was observed (Figure 3), its high elutability is possibly a result of the relatively short PEO chain length afforded by immobilized F68 being insufficient to form the level of attractive associations required for entrapment.

Research Highlights.

Nisin entrapment occurs within the inner, hydrophobic phase of pendant PEO

Nisin entrapment in PEO does not involve association with the underlying surface

Sufficient hydrophobic association with PEO is required for stable entrapment

Peptide entrapment in PEO layers offers an attractive platform for drug delivery

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB, grant no. R01EB011567). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIBIB or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wiedemann I, Breukink E, van Kraaij C, Kuipers OP, Bierbaum G, de Kruijff B, Sahl HG. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai Y-C, Joshi P, McGuire J, Neff JA. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2008;322:112. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tai Y-C, McGuire J, Neff JA. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2008;322:104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryder MP, Schilke KF, Auxier JA, McGuire J, Neff JA. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2010;350:194. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2010.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schilke KF, McGuire J. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2011;358:14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tie Y, Calonder C, Van Tassel PR. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2003;268:1. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9797(03)00516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popat KC, Johnson RW, Desai TA. Surf Coat Technol. 2002;154:253. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson T, Kidane A, Szleifer I, Park K. Langmuir. 1998;14:176. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsden JJ. J Mater Chem. 1994;4:1263. [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Feijter JA, Benjamins J, Veer FA. Biopolymers. 1978;17:1759. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unsworth LD, Sheardown H, Brash JL. Langmuir. 2008;24:1924. doi: 10.1021/la702310t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calonder C, Tie Y, Van Tassel PR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181337298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calonder C, Van Tassel PR. Langmuir. 2001;17:4392. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi O, Lee HJ, McGuire J, Finneran P, Bird KE. Colloids Surf B. 2006;50:26. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakamraju M, McGuire J, Daeschel M. J Colloid Interf Sci. 1996;178:495. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halperin A. Langmuir. 1999;15:2525. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheth SR, Leckband D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halperin A. Eur Phys J B. 1998;3:359. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu T, Wu C. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;83:4105. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner M, Brochard-Wyart F, Hervet H, Gennes P. Colloid Polym Sci. 1993;271:621. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, Kim DH, Witte KN, Ohn K, Choi J, Akgun B, Satija S, Won YY. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:7367. doi: 10.1021/jp301817e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]