Abstract

Memory processes may be independent, compete, operate in parallel, or interact. In accordance with this view, behavioral studies suggest that the hippocampus (HPC) and prefrontal cortex (PFC) may act as an integrated circuit during performance of tasks that require working memory over longer delays, whereas during short delays the HPC and PFC may operate in parallel or have completely dissociable functions. In the present investigation we tested rats in a spatial delayed non-match to sample working memory task using short and long time delays to evaluate the hypothesis that intermediate CA1 region of the HPC (iCA1) and medial PFC (mPFC) interact and operate in parallel under different temporal working memory constraints. In order to assess the functional role of these structures, we used an inactivation strategy in which each subject received bilateral chronic cannula implantation of the iCA1 and mPFC, allowing us to perform bilateral, contralateral, ipsilateral, and combined bilateral inactivation of structures and structure pairs within each subject. This novel approach allowed us to test for circuit-level systems interactions, as well as independent parallel processing, while we simultaneously parametrically manipulated the temporal dimension of the task. The current results suggest that, at longer delays, iCA1 and mPFC interact to coordinate retrospective and prospective memory processes in anticipation of obtaining a remote goal, whereas at short delays either structure may independently represent spatial information sufficient to successfully complete the task.

Keywords: Prefrontal, Hippocampus, Working memory, Parallel processing, Interactions, Dynamics

1. Introduction

Memory processes may be independent, compete, operate in parallel, or interact [1–16]. A network of brain regions is necessary for working memory processes and accumulating evidence suggests that two structures essential for working memory, the HPC and PFC, have a functionally dynamic relationship that depends on the conditions of the task [6,13,17–20]. Specifically, it has been suggested that the HPC and mPFC may at times operate independently and in parallel under conditions in which there is a brief delay between the study phase and test phase [19] or interact under conditions in which prospective memory is necessary at longer delays [18].

Examining memory from the standpoint of processing spatial information through the temporal domain suggests that both the HPC and PFC are involved in working memory [21] and there is a growing body of evidence in support of this view. Several studies in rodents have used a disconnection procedure to show that the HPC interacts with the mPFC for spatial encoding, retrieval, and delayed spatial working memory [22–25]. There is also evidence that the HPC and mPFC may process information independently and in parallel in spatial working memory tasks with short time delays [19].

Interactions between neural systems may be inferred when performance is impaired after asymmetrical unilateral inactivation of two different regions is performed, yielding a disconnection between the targeted structures [26–31]. Conversely, parallel processing may be inferred when behavioral impairments are induced by simultaneous bilateral inactivation of two different structures, but separate bilateral inactivation of either of the two structures leaves performance intact [19,32].

In the present investigation, we intended to extend previous findings by simultaneously examining independent parallel processing and interactions in the HPC and PFC during performance of a spatial working memory task in rats. In order to do so, we used a within subjects design in which each subject received bilateral cannula implantation of both the iCA1 and mPFC. This approach allowed for inactivation of individual structures bilaterally, contralaterally or ipsilaterally, or combined bilateral inactivation of both structures simultaneously within subjects. Further, we targeted iCA1 because this region of the HPC projects directly to mPFC. Specifically, CA1 projections arise at the shoulder of the rostral CA1 region, extend ventrally along the longitudinal axis of CA1 and the entire longitudinal axis of the subiculum, and terminate in the mPFC [33]. Support for a functional relationship between iCA1 and mPFC comes from electrophysiological studies showing that long-term potentiation can be induced in mPFC through stimulation of the iCA1region [34–36].

We expected that we would be able to capture functional dynamics between the HPC and PFC that included interactions and independent parallel processing by using an inactivation approach combined with parametric manipulation of working memory requirements across the temporal domain. We hypothesized that either the iCA1or mPFC are sufficient to sustain spatial representations for working memory processes over short delays by operating independently and in parallel, whereas during longer delays, we predicted that the HPC and mPFC are both necessary and act in concert through retrospective and prospective memory processes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Surgical procedure

All planned procedures and animal care were in accordance with the National Institute of Health and Institute for Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Utah. Nine male Long Evans rats weighing 250–350g were housed in individual plastic containers and kept on a 12/12 light/dark cycle. Their weight was maintained at 80–90% of free feed weight with water available ad libitum. Prior to surgery, subjects were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane gas, placed in a sterotaxic apparatus with a continuous flow of isoflurane, and prepared for the surgical procedure by applying a surgical drape and betadine antiseptic to the surgical site. An incision was made in the skin above the skull. The skin was retracted and burr holes were drilled in the skull to receive stainless-steel anchor screws and provide access to the regions intended for cannula implantation. Cannulas were lowered bilaterally in both structures to the following coordinates: mPFC: 25° from midline, 3.0 mm anterior to bregma, ±2.0 mm lateral from midline, 4.6 mm ventral from dura; iCA1: 5.8 mm posterior to bregma, ±5.3 mm lateral from midline, 3.4 mm ventral from dura. Cranioplastic cement was applied around cannulas and screws to permanently anchor the cannulas in place. Following surgery subjects remained on a heating pad and were monitored until they were conscious and upright. Prior to being returned to their home cage each subject received acetaminophen (Children's Tylenol; 200 mg/100 ml of water) as an analgesic. Subjects also received mashed food for 3 days following surgery. The health status of all subjects was closely monitored following surgery until post-surgical testing was initiated.

2.2. Behavioral apparatus

The experiment was performed on a radial 8-arm maze (Fig. 1). The maze was 65 cm high, with eight 60 cm long × 9 cm wide arms. The arms had 30 cm high clear Plexiglas walls. There were 2.5 cm in diameter × 1.5 cm deep wells at the end of each arm for food rewards. The center platform was a 40 cm in diameter octagon with each arm centered on the middle of one side. Above the center of the platform, there was a cylindrical plastic bucket (38 cm in diameter and 75 cm in height). Each arm had a retractable Plexiglas barrier between the entrance to the arm and the center platform, allowing the animal to gain entrance to the arms. A 3-dimensional visual cue was attached to each of the walls. Raising and lowering of the Plexiglas barriers and bucket was remotely controlled from a smaller room outside of the testing room.

Fig. 1.

Shows 8-arm maze and testing procedure for the delay non-match to sample task using two different time delays, 10 s and 5 min.

2.3. Behavioral task and experimental design

Subjects were trained on a delayed non-match to place task. We generally followed the behavioral methods of Lee and Kesner [19] in this study. However, the present investigation was distinguished by the fact that subjects were trained prior to testing for both 10 s and 5 min delays and separation between study phase and testing phase arms were pseudorandomly selected as opposed to being adjacent. A further difference in our design involved using temporary pharmacological inactivation for all conditions of testing. Prior to training, subjects were handled by a single experimenter for 5 min each day over 5 consecutive days. Following the handling period, subjects were habituated to the training apparatus. Habituation entailed placing food rewards (Froot Loops cereal; Kellogg, Battle Creek, MI) on the maze for 20 min and allowing the subject to explore the maze and obtain the rewards. Over the 5-day habituation period, food rewards were moved closer to the food well until they were placed in the well. The goal of behavioral training was to have subjects obtain food rewards for remembering spatial locations. Experimental designs that test working memory vary greatly; however, they maintain a general set of features. Typically, a study phase occurs in which a modality specific sensory stimulus is presented to the subject. The study phase is followed by a delay in the absence of the stimulus. Following the delay, a test phase occurs in which the subject must remember the original stimulus and make a behaviorally appropriate response to receive a reward. Variables that are frequently manipulated include the length of the delay period, the amount of information to be remembered, and the type of information to be remembered. In the current study we presented a single spatial location as the study stimulus to be remembered, manipulated the length of the delay, and used two spatial locations (the sample location and a new location) during the testing phase.

Training was composed of a pre-training and post-training period (Fig. 2). During the pre-training period, animals were placed at the center of an 8-arm maze platform and one of eight pseudorandomly selected arms was opened. The study arm was closed after the subject obtained the food reward and returned to the center platform and a bucket was lowered over the center platform for 10 s. At the end of the delay, the test phase began. The bucket was raised and the rat faced two open arms (Fig. 1). To obtain a food reward the rat was required to choose the non-match arm. A twenty sec intertrial interval followed each trial. Subjects received eight daily trials, until they obtained at least 100% choice accuracy. After obtaining 100% accuracy at the 10 s delay, half of the trials were pseudorandomly interleaved with the 5 min delay trials until the subjects again obtained 100% correct on all trials. Subjects typically required 2–3 weeks of training to reach the final criterion. After reaching criterion, subjects received surgery. Ten days following recovery from surgery, training was reinitiated with eight trials daily at the 10 s and 5 min delay until subjects reached eight/eight correct trials in a single day. Post-training typically required 1 week for subjects to reacquire criterion performance at both delays. Post-training testing occurred in three stages corresponding to patterns of inactivation (Figs. 2 and 3). Once subjects reached 100% correct trials in a single session, in stage 1 of testing, saline infusions were administered bilaterally into mPFC or iCA1 until subjects obtained a criterion of at least 75% correct trials for both delays for 2 consecutive days. On the day following criterion acquisition, subjects received bilateral infusions of muscimol to temporarily and reversibly inactivate the selected neural structures (iCA1 or mPFC). In stage two of testing, training was again initiated with subjects receiving either ipsilateral or contralateral infusions of saline into iCA1 and mPFC. After reaching a criterion of at least 75% correct trials for both delays for 2 consecutive days, subjects received ipsilateral or contralateral infusions of muscimol into iCA1 and mPFC in accord with whichever pattern had been used during the saline condition. In stage three of testing, subjects received bilateral infusions of saline into iCA1 and mPFC until reaching a criterion of at least 75% correct performance for both delays for 2 consecutive days. On the day following criterion acquisition, subjects received infusions of musicmol bilaterally into both iCA1 and mPFC.

Fig. 2.

Shows study design divided into pre-training, surgery and post-training periods. During pre-training subjects were trained at the 10 s and 5 min delay until they reached a criterion of 100% correct performance for both delays. Surgery followed pre-training criterion performance, with bilateral cannula implantation of both iCA1 and mPFC. Subjects were then retrained to a criterion of at least 100% correct performance for both delays, at which time saline was infused bilaterally into either iCA1 or mPFC. After reaching at least 75% correct performance for both delays under the saline condition for 2 consecutive days, the following day subjects received bilateral infusions of muscimol into either iCA1 or mPFC prior to testing. Following reacquisition of criterion performance with either ipsilateral or contralateral saline infusions into iCA1 and mPFC, subjects received ipsilateral or contralateral muscimol infusions into iCA1 or mPFC. Lastly, subjects were retrained to a criterion of at least 75% correct performance at both delays while receiving bilateral infusions of saline into both iCA1 and mPFC iCA1. After reaching criterion performance under the saline condition, bilateral infusions of iCA1 and mPFC were performed. iCA1 = hippocampus intermediate CA1; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex.

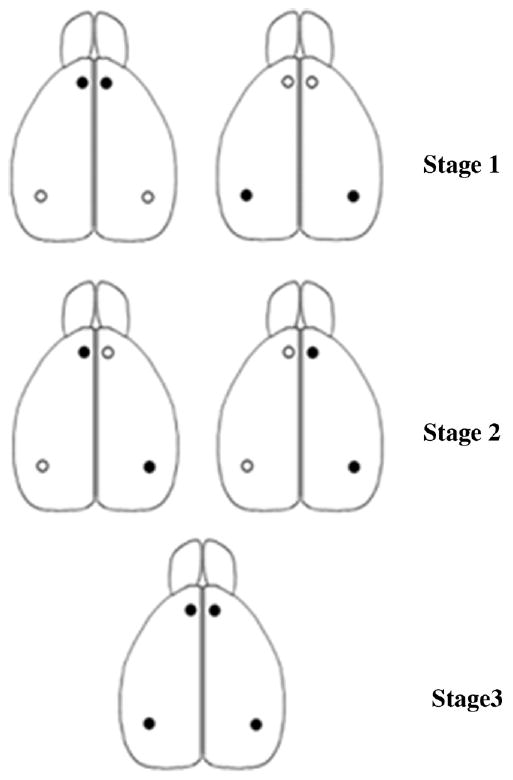

Fig. 3.

Shows dorsal view of the rat brain with patterns of inactivation used to test for interactions and independent parallel processing indicated by black dots. Stage 1-top left = bilateral mPFC; top right = bilateral iCA1; Stage 2 – middle left = contralateral iCA1and mPFC; middle right = ipsilateral iCA1 and mPFC; Stage 3-bottom middle = bilateral iCA1 and mPFC. iCA1 = hippocampus intermediate CA1; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex.

2.4. Injection procedure

Subjects were habituated to the injection procedure by loosening and tightening the cannula obdurators for three days prior to behavioral testing. Prior to testing subjects received central infusions consisting of 0.2 μL phosphate buffered saline or muscimol 0.2 μL (20.0 μg/0.5 μL) (Sigma–Aldrich, USA). Infusions were made with a Hamilton 10.0 μL syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) controlled by a microinfusion pump (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) at a rate of 0.1 μL/min. The injection cannula was left in place for at least 1 min after each infusion to allow the drug to diffuse away from the cannula tip. Subjects began training 5–10 min after the final infusion.

2.5. Histological procedure

After testing, subjects were euthanized with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital. Transcardial infusion of 0.9% saline was followed by infusion of 10% formaldehyde. Brains were refrigerated for 48 h at 4°C in a 10% sucrose and 30% formalin solution. Coronal sections of frozen brains were obtained using a cryostat and stained with cresyl violet to verify cannula placements.

3. Results

3.1. Statistical results

The results are shown in Fig. 4A–C for the 5 min delay and Fig. 5A–C for the 10 s delay. Compared to saline infusions, subjects (n = 9) receiving bilateral infusions of muscimol into mPFC or iCA1, contralateral infusions of muscimol into mPFC and iCA1, or bilateral infusions of muscimol into both mPFC and iCA1 were impaired at the 5 min delay, whereas only bilateral infusions of muscimol into both mPFC and iCA1 produced impairments at the 10 s delay. A two factor repeated measure design was used to examine the number of correct choices as a function of treatment (2 levels: saline; muscimol) and pattern of inactivation (5 levels: bilateral mPFC; bilateral iCA1; contralateral iCA1-mPFC; ipsilateral iCA1-mPFC; bilateral mPFC and iCA1). Separate analyses were carried out for the 10 s delay and the 5 min delay conditions. Post hoc tests used the Bonferroni adjustment for comparisons of interest.

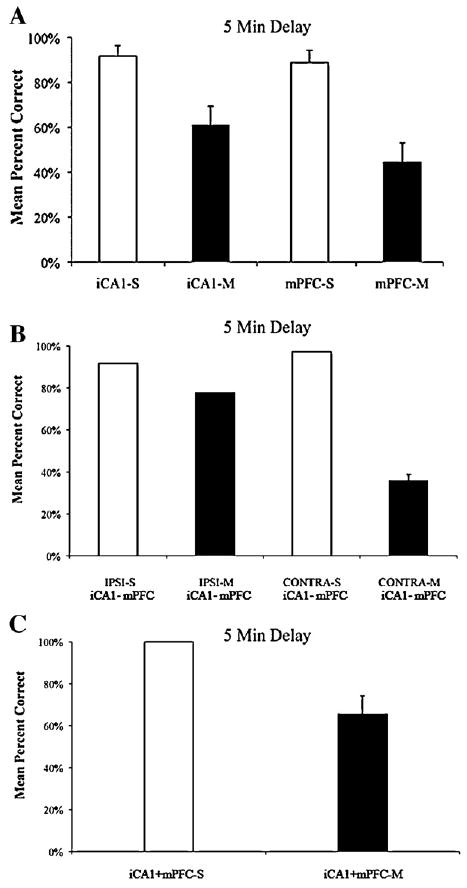

Fig. 4.

(A) Shows mean percent correct performance with standard error at the 5 min delay for subjects receiving bilateral infusions of saline (S) or muscimol (M) into iCA1 or mPFC (B) Shows mean percent correct performance with standard error at the 5 min delay for subjects receiving ipsilateral or contralateral infusions of saline (S) or muscimol (M) into iCA1 and mPFC (C) Shows mean percent correct performance with standard error at the 5 min delay for subjects receiving bilateral infusions of saline (S) or muscimol (M) into both iCA1 and mPFC.

Fig. 5.

(A) Shows mean percent correct performance with standard error at the 10 s delay for subjects receiving bilateral infusions of saline (S) or muscimol (M) into iCA1 or mPFC. (B) Shows mean percent correct performance with standard error at the 10 s delay for subjects receiving ipsilateral or contralateral infusions of saline (S) or muscimol (M) into iCA1 and mPFC. (C) Shows mean percent correct performance with standard error at the 10 s delay for subjects receiving bilateral infusions of saline (S) or muscimol (M) into both iCA1 and mPFC.

The results revealed that there was a significant main effect at the 5 min delay for treatment F(1, 31) = 60.12, p < 0.001, pattern of inactivation F(4, 124) = 2.59, p < 0.05, and treatment x pattern of inactivation F(4, 124) = 5.41, p < 0.001. For stage 1, Post hoc tests demonstrated significant effects of bilateral inactivation of mPFC t(35) = 4.78, p < 0.001 or iCA1 t(35) = 3.92, p < 0.001 with subjects in the muscimol conditions making significantly fewer correct choices when compared to the respective saline conditions (Fig. 4A). Similarly, for stage 2, contralateral infusions of muscimol into iCA1 and mPFC also caused subjects to produce more errors than ipsilateral infusions of muscimol into the same regions t(35) = 5.0, p < 0.001, (Fig. 4A). For stage 3, bilateral inactivation of both iCA1 and mPFC also caused subjects to commit more errors than in the saline control condition t(31) = 5.97, p < 0.001, (Fig. 4A).

For the 10 s delay, there was a significant main effect of treatment F(1, 31) = 18.21, p < 0.001, pattern of inactivation F(4, 124) = 9.78, p < 0.001 and treatment x pattern of inactivation F(4, 124) = 9.78, p < 0.001. Post hoc tests revealed no significant effects for stage 1 with bilateral mPFC saline compared to muscimol t(35) = 1.0, p > 0.3, bilateral iCA1 saline compared to muscimol t(35) = 1.78, p > 0.08, or stage 2 with contralateral compared with ipsilateral iCA1 and mPFC muscimol infusions t(35) = 1.0, p > 0.3, (Fig. 5A and B). However, for stage 3 there was a significant difference between the saline and muscimol conditions for bilateral inactivation of both iCA1 and mPFC t(31) = 4.03, p < 0.001 (Fig. 5C).

3.2. Histological results

Cannula placements are shown in Fig. 6. Cannulas targeting the mPFC were observed across the medial orbital, infralimbic, and prelimbic regions. Cannulas targeting the intermediate CA1 region of the hippocampus were observed across the posterior hippocampus through the shoulder of CA1 bordering the dentate gyrus and longitudinally across the CA1/2 transition area. Cannulas targeting the intermediate CA1 were also observed between the most rostral portion of dorsal CA1 extending into the dorsocaudal compartment of the subiculum.

Fig. 6.

Histological plates showing locations of bilateral cannula tips for implantation in both iCA1 and mPFC for all subjects (N = 9). Some points overlap. Histological plates were adapted from [59].

4. Discussion

In the first stage of testing, we found that bilateral inactivation of the iCA1 or mPFC led subjects to commit more errors at the 5 min delay, but not the 10 s delay, thus demonstrating that, under distinct memory requirements, the iCA1 region of the hippocampus and mPFC are both necessary for normal working memory processes. Our observations are consistent with several studies showing that the HPC and mPFC are involved in delayed working memory and spatial memory [18,37–41].

In the second stage of the study, disconnection of iCA1 and mPFC also significantly increased errors during the 5 min delay, but not the 10 s delay, when compared to the ipsilateral inactivation control condition. Taken together with the initial observation that each structure is necessary at longer delays, the results suggest that these brain regions also interact under long delay memory requirements. This finding adds to a growing body of evidence in support of interactions between the HPC and mPFC in working memory and memory processes [18,23–25,41–44].

Working memory performance decrements observed at long delays are thought to result from memory impairment, per se [45]. Extending the temporal requirement for spatial information maintenance may enhance the need to store and retrieve spatial representations, which may be disrupted by functional inactivation of the HPC and mPFC. Consistent with this idea, it has been suggested that the HPC and mPFC share a functional overlap in retrieving episodic information about where an event occurred [46]. However, there is evidence to argue against a purely mnemonic interpretation of delay memory performance. For example, Gisquet-Verrier and Delatour [47] tested rats in a spatial win-shift task with a within session change from a zero time delay to a one minute delay and found that rats with lesions of mPFC showed a transient decrement in performance at the one minute delay when compared to controls. This led them to further assess the role of mPFC in delayed memory by changing from a long 5 min delay to a longer 30 min delay, which showed that mPFC lesioned subjects were unimpaired in contrast to controls. These results suggested that memory maintenance was not disrupted in the mPFC lesioned rats. In contrast, when an interference condition was introduced during the delay, they found that mPFC subjects were impaired. They concluded that mPFC is not involved in maintaining information over delays but rather performs monitoring processes essential for adapting to new contingencies subsequently necessary for planning. Similarly, Floresco et al. (1997) suggested that interactions between the HPC and mPFC during a delayed foraging task are not the product of the delay per se, but rather result from the need for these structures to interact in prospective memory.

Fuster [48] defines working memory as the “ability to retain an item of information for the prospective execution of an action that is dependent on that information”. Consistent with this view of working memory, increased delays may require prospective coding that depends on retroactive memory search [4,19]. Prospective memory process are largely defined by the intention to execute an action plan in the future and rely on the ability to code and later retrieve the plan content at the appropriate time in the future, often in the presence of an action-eliciting cue. There is evidence to suggest that the HPC is involved in both prospective and retrospective memory [49,50] and that mPFC is involved in a shift from retrospective to prospective memory processes [51]. Moreover, a study examining single-unit recordings acquired from the PFC of rhesus monkeys performing a delayed paired-associate task showed that cells in this region reflect the sample object at the beginning of the delay and anticipate the target object towards the end of the delay, indicating the use of a prospective code [52]. It has also been shown that the HPC and mPFC are necessary for temporal ordering of spatial location sequences [53–55]. Since long delays may dictate a shift in memory strategy, the mPFC may be necessary to organize spatial sequences represented in the HPC for prospective coding. To the extent that the long delay condition in the current task requires encoding, retrieval, and execution of a plan based on memory for a past event in anticipation of obtaining a goal in the future, the HPC and mPFC may be required to act as a functionally integrated circuit to facilitate working memory performance when both retrospective and prospective information processing are necessary.

In the third stage of testing, simultaneous bilateral inactivation of iCA1 and mPFC led to impairments at short and long delays. However, bilateral inactivation of either the iCA1 or mPFC regions separately at the 10 s delay did not produce an appreciable difference in performance, in contrast with the saline vehicle control condition. From the perspective of a circuit-level analysis, it would appear that either iCA1 or mPFC are sufficient at short delays, but at least one structure is necessary. Mizumori et al. [2] has proposed that spatial information may be continuously encoded by multiple neural structures simultaneously and, consistent with this view, the present study suggests that either the HPC or mPFC are sufficient to maintain spatial information necessary for performance of a working memory task over brief delays. Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that parallel processing occurs in these structures and a number of previous studies support this view.

Although lesions of PFC are known to induce disruptions in working memory performance, there is substantial evidence to suggest that such impairments are not present at very short delays but rather begin to emerge at longer delays. For example, lesions of primate dorsolateral PFC or infusion of a dopamine receptor antagonist into the same region produced impairments that are present at increasing delays [56,57]. Delay dependent deficits have also been observed after lesions or inactivation of the mPFC performed in rats [39,40]. Similarly, lesions of the primate HPC do not produce impairments at very brief delays, but subjects become significantly impaired at 30 s delays [58]. HPC inactivation also produces impairments at longer but not short delays in rats tested in a delayed alternation task [41]. Further, Watanabe and Niki [59] showed that 46% of cells recorded from the primate HPC were active during the delay period of a working memory task and delay dependent HPC cells have been reported to increase in activity level as the delay period progresses [60]. Consistent with our observations, these studies strongly suggest that either the HPC or PFC is sufficient for working memory over brief delays.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a unique methodological strategy for testing functional dynamics within memory networks using an animal model. Specifically, we used simultaneous bilateral cannula implantation of multiple neural structures within subjects to provide a circuit-level analysis of HPC and PFC function in spatial working memory while simultaneously parametrically manipulating temporal memory requirements. Our observations based on this approach advances theory by providing empirical support that memory is sustained by dynamic neural processes. Specifically, the present results suggest that the HPC or mPFC can represent mnemonic information independently and in parallel sufficient for working memory performance at very brief delays. Moreover, at longer delays, the iCA1 and mPFC interact to coordinate retrospective and prospective memory processes by separating and sequencing past episodes for prospective coding in anticipation of obtaining a remote goal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R1MH065314.

References

- 1.Gold PE. Coordination of multiple memory systems. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:230–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizumori SJ, Yeshenko O, Gill KM, Davis DM. Parallel processing across neural systems: implications for a multiple memory system hypothesis. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:278–98. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaffan D. Against memory systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:1111–21. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kesner RP, Rogers J. An analysis of independence and interactions of brain substrates that subserve multiple attributes, memory systems, and underlying processes. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:199–215. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White NM, McDonald RJ. Multiple parallel memory systems in the brain of the rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;77:125–84. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baddeley A, Bueno O, Cahill L, Fuster JM, Izquierdo I, McGaugh JL, et al. The brain decade in debate: I, neurobiology of learning and memory. BrazJ Med Biol Res. 2000;33:993–1002. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranganath C, D'Esposito M. Directing the mind's eye: prefrontal, inferior and medial temporal mechanisms for visual working memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poldrack RA, Packard MG. Competition among multiple memory systems: converging evidence from animal and human brain studies. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:245–51. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaffan D. What is a memory system? Horel's critique revisited. Behav Brain Res. 2001;127:5–11. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuster JM. Cortical dynamics of memory. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;35:155–64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris RG, Hagan JJ, Rawlins JN. Allocentric spatial learning by hippocampectomised rats: a further test of the “spatial mapping” and “working memory” theories of hippocampal function. QJ Exp Psychol B. 1986;38:365–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGaugh JL, Cahill L, Roozendaal B. Involvement of the amygdala in memory storage: interaction with other brain systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13508–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Constantinidis C, Procyk E. The primate working memory networks. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2004;4:444–65. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JJ, Baxter MG. Multiple brain-memory systems: the whole does not equal the sum of its parts. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:324–30. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeDoux JE. Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. New York: Viking; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olton DS. Neurobiology of the hippocampus. In: Seifert W, editor. Memory Functions and the Hippocampus. London; New York: Academic Press; 1983. p. xxv.p. 632p. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gazzaley A, Rissman J, Desposito M. Functional connectivity during working memory maintenance. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2004;4:580–99. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.4.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Floresco SB, Seamans JK, Phillips AG. Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical, and ventral striatal circuits in radial-arm maze tasks with or without a delay. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1880–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01880.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee I, Kesner RP. Time-dependent relationship between the dorsal hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex in spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1517–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01517.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranganath C. Working memory for visual objects: complementary roles of inferior temporal, medial temporal, and prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;139:277–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sybirska E, Davachi L, Goldman-Rakic PS. Prominence of direct entorhinal-CA1 pathway activation in sensorimotor and cognitive tasks revealed by 2-DG functional mapping in nonhuman primate. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5827–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05827.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seamans JK, Floresco SB, Phillips AG. D1 receptor modulation of hippocampal-prefrontal cortical circuits integrating spatial memory with executive functions in the rat. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1613–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01613.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang GW, Cai JX. Disconnection of the hippocampal-prefrontal cortical circuits impairs spatial working memory performance in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Churchwell JC, Morris AM, Musso ND, Kesner RP. Prefrontal and hippocampal contributions to encoding and retrieval of spatial memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;93:415–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izaki Y, Takita M, Akema T. Specific role of the posterior dorsal hippocampus-prefrontal cortex in short-term working memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:3029–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geschwind N. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man I. Brain. 1965;88:237–94. doi: 10.1093/brain/88.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ettlinger G. Visual discrimination following successive temporal ablations in monkeys. Brain. 1959;82:232–50. doi: 10.1093/brain/82.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baxter MG, Parker A, Lindner CC, Izquierdo AD, Murray EA. Control of response selection by reinforcer value requires interaction of amygdala and orbital prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4311–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04311.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Floresco SB, Ghods-Sharifi S. Amygdala-prefrontal cortical circuitry regulates effort-based decision making. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:251–60. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogers JL, Kesner RP. Hippocampal-parietal cortex interactions: evidence from a disconnection study in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2007;179:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Churchwell JC, Morris AM, Heurtelou NM, Kesner RP. Interactions between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala during delay discounting and reversal. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:1185–96. doi: 10.1037/a0017734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald RJ, White NM. Hippocampal and nonhippocampal contributions to place learning in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:579–93. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jay TM, Witter MP. Distribution of hippocampal CA1 and subicular efferents in the prefrontal cortex of the rat studied by means of anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. J Comp Neurol. 1991;313:574–86. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jay TM, Burette F, Laroche S. Plasticity of the hippocampal-prefrontal cortex synapses. J Physiol Paris. 1996;90:361–6. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(97)87920-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takita M, Izaki Y, Jay TM, Kaneko H, Suzuki SS. Induction of stable long-term depression in vivo in the hippocampal-prefrontal cortex pathway. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4145–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takita M, Izaki Y, Kuramochi M, Yokoi H, Ohtomi M. Synaptic plasticity dynamics in the hippocampal-prefrontal pathway in vivo. NeuroReport. 2010;21:68–72. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283344949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark RE, West AN, Zola SM, Squire LR. Rats with lesions of the hippocampus are impaired on the delayed nonmatching-to-sample task. Hippocampus. 2001;11:176–86. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hampson RE, Jarrard LE, Deadwyler SA. Effects of ibotenate hippocampal and extrahippocampal destruction on delayed-match and -nonmatch-to-sample behavior in rats. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1492–507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01492.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor CL, Latimer MP, Winn P. Impaired delayed spatial win-shift behaviour on the eight arm radial maze following excitotoxic lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2003;147:107–14. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izaki Y, Maruki K, Hori K, Nomura M. Effects of rat medial prefrontal cortex temporal inactivation on a delayed alternation task. Neurosci Lett. 2001;315:129–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maruki K, Izaki Y, Hori K, Nomura M, Yamauchi T. Effects of rat ventral and dorsal hippocampus temporal inactivation on delayed alternation task. Brain Res. 2001;895:273–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang GW, Cai JX. Reversible disconnection of the hippocampal-prelimbic cortical circuit impairs spatial learning but not passive avoidance learning in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:365–73. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones MW, Wilson MA. Theta rhythms coordinate hippocampal-prefrontal interactions in a spatial memory task. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyman JM, Zilli EA, Paley AM, Hasselmo ME. Working memory performance correlates with prefrontal-hippocampal theta interactions but not with prefrontal neuron firing rates. Front Integr Neurosci. 2010;4:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.002.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez JS, Paule MG. Methods of Behavioral Analysis in Neuroscience Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2nd. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2009. p. xxi.p. 351p. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devito LM, Eichenbaum H. Distinct contributions of the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to the “what-where-when” components of episodic-like memory in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gisquet-Verrier P, Delatour B. The role of the rat prelimbic/infralimbic cortex in working memory: not involved in the short-term maintenance but in monitoring and processing functions. Neuroscience. 2006;141:585–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuster JM. The prefrontal cortex: anatomy, physiology, and neuropsychology of the frontal lobe. 4th. London: Academic press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kametani H, Kesner RP. Retrospective and prospective coding of information: dissociation of parietal cortex and hippocampal formation. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:84–9. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferbinteanu J, Shapiro ML. Prospective and retrospective memory coding in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2003;40:1227–39. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kesner RP. Retrospective and prospective coding of information: role of the medial prefrontal cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1989;74:163–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00248289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rainer G, Rao SC, Miller EK. Prospective coding for objects in primate prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5493–505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05493.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiba AA, Kesner RP, Gibson CJ. Memory for temporal order of new and familiar spatial location sequences: role of the medial prefrontal cortex. Learn Mem. 1997;4:311–7. doi: 10.1101/lm.4.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiba AA, Kesner RP, Reynolds AM. Memory for spatial location as a function of temporal lag in rats: role of hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;61:123–31. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kesner RP, Holbrook T. Dissociation of item and order spatial memory in rats following medial prefrontal cortex lesions. Neuropsychologia. 1987;25:653–64. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(87)90056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawaguchi T, Goldman-Rakic PS. The role of D1-dopamine receptor in working memory: local injections of dopamine antagonists into the prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkeys performing an oculomotor delayed-response task. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:515–28. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Funahashi S, Bruce CJ, Goldman-Rakic PS. Dorsolateral prefrontal lesions and oculomotor delayed-response performance: evidence for mnemonic “scotomas”. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1479–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01479.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zola SM, Squire LR, Teng E, Stefanacci L, Buffalo EA, Clark RE. Impaired recognition memory in monkeys after damage limited to the hippocampal region. J Neurosci. 2000;20:451–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00451.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe T, Niki H. Hippocampal unit activity and delayed response in the monkey. Brain Res. 1985;325:241–54. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colombo M, Gross CG. Responses of inferior temporal cortex and hippocampal neurons during delayed matching to sample in monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:443–55. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]