Abstract

A goal of regenerative medicine is to identify cardiovascular progenitors from human ES cells (hESCs) that can functionally integrate into the human heart. Previous studies to evaluate the developmental potential of candidate hESC-derived progenitors have delivered these cells into murine and porcine cardiac tissue, with inconclusive evidence regarding the capacity of these human cells to physiologically engraft in xenotransplantation assays. Further, the potential of hESC-derived cardiovascular lineage cells to functionally couple to human myocardium remains untested and unknown. Here, we have prospectively identified a population of hESC-derived ROR2+/CD13+/KDR+/PDGFRα+ cells that give rise to cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro at a clonal level. We observed rare clusters of ROR2+ cells and diffuse expression of KDR and PDGFRα in first-trimester human fetal hearts. We then developed an in vivo transplantation model by transplanting second-trimester human fetal heart tissues s.c. into the ear pinna of a SCID mouse. ROR2+/CD13+/KDR+/PDGFRα+ cells were delivered into these functioning fetal heart tissues: in contrast to traditional murine heart models for cell transplantation, we show structural and functional integration of hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors into human heart.

Keywords: engraftment, surface markers, Stem cells, mature cardiomyocytes, clonal analysis

Human cardiomyocytes are derived from proliferating precursors during development, but there is little evidence to support a robust postnatal regenerative capacity (1, 2). As a consequence, myocardial injury or disease in adult humans results in irreversible cardiomyocyte loss that can lead to progressive heart failure. Cell transplantation may be an effective therapy to compensate for myocardial loss in an attempt to improve the pumping ability of the damaged heart (3). The expected mechanism by which the grafted cells may restore function is to couple with the native host myocardium, thereby functionally replacing the dead tissue, with the assumption that the grafted cells or tissue adopt a cardiovascular fate in situ (4, 5). However, no study to date has demonstrated the delivery of a pure population of tissue-specific stem cells capable of generating functioning cardiomyocytes in the injured or healthy myocardium. Although adult stem cells have failed to convincingly regenerate myocardial tissue, consistent with many reports that demonstrate the nonplasticity of adult organ-specific stem cells (6, 7), human ES cells (hESCs) have proven to be a potential and unlimited source for generating cardiomyocytes in vitro as a result of their pluripotent nature (8).

Although several studies have reported efficient differentiation of hESCs toward cardiovascular lineages, the two most significant barriers to therapy remain the heterogeneity of the putative progenitor cells and the fate of these cells upon transplantation, which remains insufficiently characterized for prospective clinical application (9–11). The current method to evaluate the in vivo developmental potential and functional properties of hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors is to transplant them into animal hearts [commonly murine (muridae includes mouse and rat) or porcine models] (12, 13). Although the transplanted cells engraft into these heart models, it is unclear whether they functionally integrate or whether demonstration of such a proof-of-principle concept would have relevance to the human. A recent report has shown electromechanical integration of hESC-derived cardiomyocyte grafts in guinea pig hearts (14). A system to prospectively isolate cardiovascular stem cells/progenitors and to evaluate their in vivo developmental potential in functioning human hearts will be an important step in clinical translation for myocardial regeneration.

Identification of surface markers that are uniquely expressed on hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors allows for their prospective isolation. Here, we prospectively isolate an enriched population of cardiovascular progenitors by using a combination of four surface markers. We then demonstrate the structural and functional integration of the hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors in beating human fetal heart tissues.

Results

Improved Culture Conditions to Promote Differentiation of hESCs to Primitive Streak, Mesoderm, and Cardiac Mesoderm Progenitors.

To promote efficient cardiovascular differentiation from hESCs, it is necessary to elucidate the signaling pathways that regulate cardiogenesis during embryonic development and to manipulate them in vitro. To this end, we established a protocol based on stage-specific activation and then inhibition of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway: we generated embryoid bodies (EBs) from the hBCL2-hESC line [enforced expression of antiapoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 in this transgenic line greatly improves the survival of hESCs in culture and experiments (15)] in serum-free media and temporally exposed them to activin A, BMP4, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), and Fibroblast Growth Factor 8 (FGF8) (Fig. S1) (16). Gene expression analysis of the populations generated at different stages of the differentiation protocol revealed induction of mesodermal genes initially (T or Brachyury and Mix-Like Homeobox), followed by cardiac mesodermal genes (MESP1), and cardiovascular progenitor genes (NKX2-5, TBX5, and MEF2C) at later stages (Fig. S1). Despite this robust differentiation assay, many cells with noncardiovascular developmental fates remained in the final product.

hESC-Derived Cardiovascular Progenitors Express a Unique Surface Marker Expression Signature.

We recently screened a large panel of mAbs to identify early lineage-committed precursors that emerge from differentiating hESCs (17). Several markers were shown to be expressed individually or in combination on mesodermal cells. A member of the receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor family, ROR2, and aminopeptidase-N (i.e., CD13) were individually shown to allow FACS to enrich for mesodermal progenitors. Because cardiac cells develop from a Flk-1 (KDR) (11)-expressing population, and the embryonic heart expresses platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFR-α) (18), we added these mAbs to the screening protocol.

To determine whether cardiovascular progenitors develop from a subpopulation of differentiating hESCs that expresses one or more of these surface markers, EBs were analyzed for expression of ROR2, CD13, KDR, and PDGFR-α after 5 d of differentiation. As shown in Fig. 1A and Fig. S2A, a distinct population marked by coexpression of ROR2 and CD13 emerges temporally as hESCs differentiate. This population exhibited a transcriptional profile similar to primitive streak/mesodermal cells (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2). Induction of genes such as T (Brachyury), MIXL, FOXA2, and SOX17 revealed patterns consistent with generation of cells of mesodermal as well as endodermal lineages.

Fig. 1.

Identification of a cardiac mesoderm population marked by four surface markers—ROR2, CD13, KDR, and PDGFRα—and their expression in human fetal hearts. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of EBs at different time points of differentiation. On day 5, a distinct population defined by coexpression of ROR2 and CD13 (II) appeared, which was further analyzed for expression of KDR and PDGFRα. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR gene expression analysis of the QP (III), ROR2+CD13+ (II), and QN (I) cells isolated from day-5 EBs. The average expression is normalized to GAPDH. Data represent mean ± SD for three biologically independent experiments (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, populations III vs. I and II vs. I). (C) Presence of NKX2-5 (Left), MEF2C (Middle), and GATA-4 (Right) immunostaining in the QP population 24 h after sorting (Fig. S2). (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (D) Immunofluorescence staining of first trimester human hearts revealed pockets of ROR2-positive cells and diffuse KDR and PDGFRα staining in the left ventricle (arrows). (Scale bar, 120 μm.) (E) An area of the left ventricle with a cluster of ROR2+ cells that also costain with NKX2-5. (Scale bar, 120 μm.)

The ROR2+/CD13+ population was sorted, and expression of KDR and PDGFRα was examined and confirmed. We then evaluated the lineage commitment of the ROR2+/CD13+/KDR+/PDGFRα+ population [hereafter referred to as the quadruple-positive (QP) population]. The QP population expressed high levels of cardiac mesoderm and cardiac developmental genes, including mesoderm posterior 1 (MESP1), the earliest known marker for cardiogenesis, and key cardiac transcription factors of the primary and secondary heart fields, including TBX5, GATA4, MEF2C, NKX2.5, and ISL1 (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2) (19, 20). In contrast, the fraction of cells in the EBs that were negative for all four markers had the highest expression of pluripotency genes, indicative of residual undifferentiated hESCs. Although the QP population highly expressed cardiac lineage genes, it also expressed genes corresponding to the primitive streak and endoderm, although to a much lesser degree (Fig. S2). Enrichment for cardiac lineage cells in the sorted QP population was confirmed by protein-level detection of NKX2-5, MEF2C, and GATA4 (Fig. 1C).

Expression of ROR2, KDR, and PDGFRα During Early Human Fetal Heart Development.

To elucidate the expression of ROR2, CD13, KDR, and PDGFRα during in utero heart development, human fetal hearts were sectioned and immunostained for these proteins. KDR and PDGFRα were broadly expressed in 9- to 10-wk-old human fetal cardiac tissue, including in the vasculature. Rare, distinct areas of ROR2 expression were detected in the myocardium and interventricular septum, but not in the epicardium (Fig. 1 D and E). In contrast, we could not detect CD13 expression. Expression of ROR2 was limited to the human fetal hearts from the first trimester, as second-trimester hearts did not stain positively for ROR2. Furthermore, examination of adult human myocardial tissues revealed no expression of ROR2 proteins.

QP Progenitor Population Gives Rise to Cardiomyocytes and Endothelial and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells.

To further characterize the in vitro developmental potential of the QP progenitor population, freshly sorted QP cells were cultured as aggregates in suspension for 7 to 10 d in the presence of Wnt11 and FGF8 in serum-free media. Consistent with the gene expression profile described earlier, the QP population gave rise to cells of the cardiovascular lineage based on immunostaining and gene expression (Fig. 2 A and B and Fig. S3A). We consistently detected a high frequency of cardiomyocytes beating spontaneously as a synchronous mass (Movie S1). When plated on Matrigel-coated dishes and treated with a high concentration of VEGF, the QP cells acquired the morphology of endothelial cells and formed a lattice (Fig. S3B). These cells expressed CD31 and von Willebrand factor and efficiently incorporated Dil-labeled acetylated LDL (Dil-Ac-LDL), confirming their endothelial phenotype functionally (Fig. 2 C and D).

Fig. 2.

In vitro characterization of QP cells. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of QP cells 6 d after sorting for markers of cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle and endothelial cells. (Scale bar, 25 μm.) (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of QP cells grown in culture after 13 d after sorting for cardiac genes. Data represent mean ± SD for three biologically independent experiments. (C) Upon exposure to VEGF after sorting, QP cells (derived from hBCL2-hESC line and therefore expressing GFP) formed a lattice of tubular structures. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (D) Endothelial phenotype was further confirmed by Dil-labeled acetylated LDL uptake. (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

To quantify the extent of cardiomyocyte generation, a cardiac troponin-GFP reporter hESC line was used and the QP population was maintained in culture for more than 30 d. More than 55% of the derived cells developed into cardiomyocytes, based on troponin expression, reflecting efficient enrichment of progenitors in the QP population (Figs. S3C and S4 A and B; Tables S1 and S2). To determine the nature of the other cell types that arise from QP cells, we performed immunostaining for endodermal, ectodermal, and hematopoietic (i.e., mesodermal) lineages. The majority of these cells stained positive for vimentin, a marker expressed on many cell types, including fibroblasts (Fig. S3D). These cells appear to expand rapidly over time (Fig. S3C).

The functional properties of the QP-derived cardiomyocytes were evaluated 10 d after sorting, using field potential measurements, as well as whole-cell patch-clamp recording (Fig. 3A). Synchronous multifocal field potential recordings performed on microelectrode arrays showed homogeneous spread of electrical activity throughout the adherent cultures (Fig. S5 A–C). Additionally, action potential (AP) recordings from single cells revealed the presence of pacemaker-, atrial-, and ventricular-like patterns characterized predominantly by a fast phase 1 depolarization. More than 90% of the single cells studied exhibited a ventricular-like AP morphology. These results confirm that the QP population can differentiate to contractile cardiomyocytes with a fetal-like AP phenotype (21).

Fig. 3.

Developmental potential of QP cells. (A) Whole-cell current-clamp recordings of spontaneous APs demonstrate ventricular-, atrial-, and nodal-like APs in the cultured QP population (Fig. S5). (B) Immunostaining of cells grown from a single GFP-QP cell indicates the presence of cardiomyocytes and endothelial and smooth muscle cells. (Top Left) Corresponding GFP cells (Fig. S6). (Scale bar, 50 μm.).

To further understand the mechanism by which QP cells commit to the cardiovascular fate, we tested whether the addition of conditioned media from cultured QP cells to control (i.e., unsorted) EBs could recapitulate the cardiac specification of QP cells. The daily addition of the QP conditioned media did not promote cardiac differentiation in control cells, indicating that QP cells do not secrete soluble proteins that enhance cardiovascular specification, arguing against a cell-nonautonomous mechanism. We next confirmed the specification of the QP population to a cardiomyocyte fate by transferring freshly sorted QP cells derived from a GFP-expressing hESC line into a synchronous EB derived from unlabeled hESCs. The majority of the GFP+ cells in the chimeric EB developed into contracting foci (Fig. S5 D–F and Movie S2). These results suggest that QP cells are a distinct population with commitment to cardiovascular fate, most likely through a cell-autonomous mechanism.

Single QP Cell Is Multipotent for Cardiovascular Lineages.

To determine further whether the QP cells are multipotential in a clonal manner, a single QP cell from a GFP-expressing hESC line was sorted directly into each well of a 96-well plate containing 1,000 WT QP cells. This approach was taken as a result of the poor survival of single QP cells when grown individually compared with their growth in clusters, in which they have better survival. After a few days in culture, colonies emerged that included foci of GFP+ cells, which were analyzed to determine the differentiation potential of a single QP cell (Fig. S6 A–D). Immunostaining of these colonies confirmed the presence of GFP+ cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle cells in these culture clones (Fig. 3B and Fig. S6D). Taken together, the clonal analysis shows that a single QP cell can generate progeny of multiple lineages, i.e., cardiomyocytes, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro, as would be expected of an embryonic cardiac progenitor.

QP Cells Transplanted into Mouse Hearts Mature to Cardiomyocytes but Fail to Integrate.

To test their in vivo developmental potential, day-5 EB-derived QP cells from a GFP-hESC line were transplanted into healthy or injured hearts of nonobese diabetic/SCID mice with common γ-chain KO. Approximately 5 to 10 × 105 QP cells were sorted and immediately transplanted by direct injection into the left ventricle of healthy mice or into the periinfarct area of mice following occlusion of the left anterior descending artery. As controls, quadruple-negative (QN) cells from the same EB culture as described earlier were also sorted and transplanted in similar areas in healthy and injured nonobese diabetic/SCID mice with common γ-chain KO. The animals were euthanized after 8 wk, and histological analyses of the explanted QP-transplanted hearts showed clusters of GFP-positive cells throughout the injected area (Fig. 4A). Although no teratomas were observed in any of the animals transplanted with the QP cardiovascular progenitors, one of the seven mice transplanted with the QN cells developed teratomas in the heart (Fig. 4D and Fig. S7D), demonstrating that even EB cells exposed to as much as 5 d of potent differentiation factors harbor some teratogenic cells, which can be excluded on the basis of the QP markers. The GFP-positive QP cells were detected only as clusters in the injection sites without significant migration, but exhibited cardiac differentiation as evidenced by expression of troponin and myosin heavy chain (Fig. 4 B and C). Despite their engraftment and differentiation into mature cells, detailed histological examination of the explanted hearts showed no gap junction formation between hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors and the host myocardium: the human QP cells failed to integrate with the mouse myocardium. We hypothesized that the failure of hESC-derived cardiomyocytes to structurally and functionally integrate into the adult mouse host may be a result of several factors, including: (i) interspecies differences that prevent the coupling of human and mouse cells, (ii) inability of an adult heart to provide an optimal environment for maturation and integration of the cardiac progenitors, and/or (iii) an inherent inability of QP-derived cardiovascular progenitors to functionally integrate.

Fig. 4.

Engraftment of QP cells in mouse myocardium. (A) (Left) Whole mouse heart explanted 8 wk after injection of GFP+ QP cells. The dotted circle indicates the approximate location of the infarct zone. (Scale bar, 0.5 mm.) GFP-hESC–derived QP cells engraft into the periinfarct regions of mouse hearts (Middle and Right). (Scale bar, 120 μm.) (B and C) Immunofluorescence staining of mouse hearts 8 wk after QP transplantation reveals presence of GFP-hESC–derived QP cells that costain with troponin (B) and with human cardiomyocyte-specific β-myosin heavy chain (C). (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (D) Immunohistochemical evidence for teratoma formation after 8 wk upon transplantation of QN cells. The QN-derived cells gave rise to all three germ layers including columnar epithelium (Left), cartilage (Center), and neural rosette (Right). (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

Structural and Functional Integration of QP Cells in Viable Fetal Human Heart.

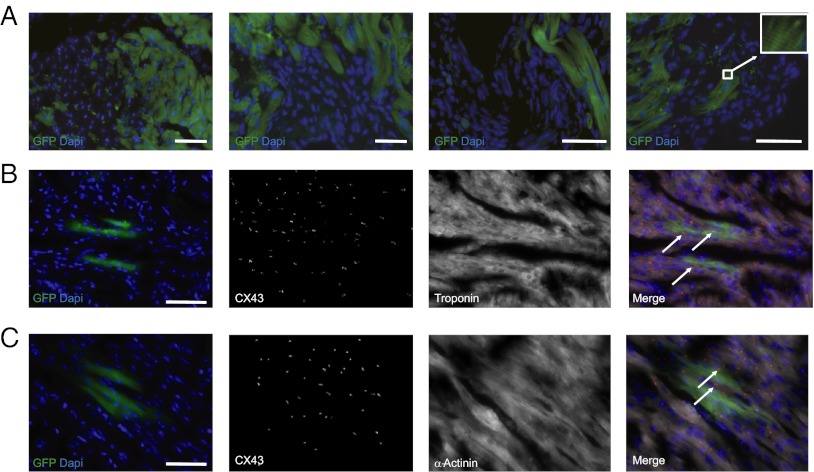

To address these issues, we developed a transplantation model that allows us to assess the functional development of hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors in fetal human hearts (22, 23). The ventricular tissues from a second-trimester human fetal heart (15 wk gestation) were implanted s.c. into a pouch formed in the ear pinna of an SCID mouse (Fig. S7A and Movie S3). Graft viability was confirmed by the presence of autonomous beating determined by visual inspection and electrocardiography ∼7 to 10 d after implantation (Fig. S7B and Movie S3). Two weeks later, ∼5 × 105 freshly sorted QP cardiovascular progenitors (and QN cells as control) from a GFP-hESC line were transplanted into the heart graft. The animals were euthanized after 8 wk, and confocal microscopy of the explanted heart receiving QP cells revealed clusters of GFP-positive cells spread throughout the myocardium, including areas distant from the injection site (Fig. 5A). Such a distribution of the grafted cells is most likely a result of migration or simple spreading, in contrast to the possibility of the cells passively spreading along the injection site (5). The GFP-positive cells coexpressed troponin, α-actinin, or CD31, which suggests in vivo differentiation of the progenitors into cardiomyocyte and endothelial lineages (Fig. 5 B and C and Fig. S7C). No teratoma formation was observed in animals receiving QP cells (n = 4). In contrast, transplantation of QN cells resulted in teratoma formation in one ear–heart model (n = 4), and transplanted QN cells did not differentiate into cardiomyocyte or endothelial lineages.

Fig. 5.

Structural Integration of QP cells in a human fetal heart. (A) Myocardial sections from human fetal heart tissues 8 wk after transplantation s.c. into mouse ear and delivery of QP cells shows clusters of GFP+ cells spread throughout the ventricle. The site of injection of QP cells in the first micrograph is in the left upper corner. (Right, Inset) High-magnification image of sarcomeric structure. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (B and C) Coexpression of GFP with cardiac-specific markers troponin (B) or α-actinin (C) and Connexin43 staining between host and transplanted GFP+ cells. (Right) Overlay with Connexin43 staining depicted in red and troponin or α-actinin in white. (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

A careful histological examination of the explanted QP-recipient heart tissues revealed typical punctate staining for connexin-43 along the regions of intimate cell-to-cell contact between hESC-derived cardiomyocytes (GFP+) and host cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5 B and C). These results indicate that, when transplanted into a human fetal heart, hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors not only mature to cardiomyocytes, they can also migrate and couple structurally to their neighboring allogeneic cells. We seldom observed phosphohistone H3-positive QP cells in explanted sections (phosphohistone H3 is a marker for mitotic activity), suggesting that, at some point within 8 wk after transplantation, the QP cells lose the robust proliferative activity they exhibit in vitro (Fig. S7E).

Although junctional proteins connecting QP cells to the surrounding cells were readily detected, it is important to determine whether the transplanted cells were also electrically connected to the host myocardium. Human fetal heart tissues with QP transplantation were removed from the mouse ear and immediately sectioned, and real-time Ca2+ transients were measured in areas with QP-derived GFP-positive cells. GFP-positive cells demonstrated periodic Ca2+ oscillations similar to—and synchronized with—the host cells (24). The Ca2+ oscillations responded to increasing frequencies of external electrical stimulation. These recordings showed conduction of Ca2+ signals from the host myocardium into areas of GFP-positive transplanted cells resembling a continuous electrical propagation (Fig. 6A and Movie S4). Although these results indicate functional integration of the transplanted QP cells into the human myocardium, the present model has limitations. We cannot rule out the possibility that the graft can be transilluminated by calcium transients in the surrounding tissue.

Fig. 6.

QP cells integrate into fetal human myocardium. (A) Myocardial sections show evoked calcium signals when paced electrically ex vivo. Fluo-4 calcium dye was added to tissue, which was then electrically paced at 2 Hz. (Right) Same area after treatment with anti-GFP antibody reveals a GFP+ area. This region was analyzed for dye intensity changes (f) and results are plotted normalized to the intensity of the initial movie frame (f0). Real-time Ca2+ flux through the tissue indicate functional integration of GFP+ cells into the host tissue. (B) GFP+ cells, derived from XX H9 ESCs, were traced for FISH analyses to reveal XX karyotype (white arrowhead, Inset), whereas the host myocardium, from a male donor, expresses XY karyotype (white arrowhead, Inset). (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

As some studies have reported fusion between transplanted cells and host myocardium (25, 26), we sought to determine whether the extent of cell fusion was significant enough to explain our findings. Because the H9 ESC line is of female origin and the transplanted fetal heart was male, we were able to perform sex mismatch analysis by evaluating for the presence of the Y chromosome in the GFP transplanted cells (derived from XX H9 cells). We traced donor GFP-positive cells for FISH with X- and Y- chromosome paints to assess karyotype (Fig. 6B). Fewer than 3.8% of the transplanted cells expressed the Y in addition to the X chromosome, which may be an overestimate for degree of cell fusion as a result of the overlap of nuclei of unique cells on 6-μm sections contributing to this value. This experiment indicates that, although rare fusion events may occur, they cannot account for the overall integration of the transplanted cardiovascular progenitors into the host tissue.

Discussion

We have identified four surface markers, ROR2, CD13, KDR, and PDGFRα, that mark early cardiovascular progenitors among differentiating hESCs. These cells, designated QP cells, can give rise to three distinct cell populations, namely cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells.

The possibility that progenitors marked by QP markers represent only a distinct, transitory state of differentiating hESCs cannot be formally excluded. We have provided evidence that ROR2/CD13 cells may resemble a population of primitive-streak/mesodermal cells. This claim is based on several lines of evidence from our work and that of others: (i) the similarity of the gene expression profiles of ROR2/CD13 cells and primitive streak cells (i.e., expression of MIXL, T, GSC, Mesp1, KDR, GATA4); (ii) in vitro phenotype of a subpopulation of ROR/CD13 cells that differentiate to cardiomyocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells, which are mesoderm-derived progeny; (iii) expression of ROR2 in the first-trimester human fetal heart; (iv) transplantation into the human fetal heart of a subpopulation of ROR2/CD13 cells resulting in robust commitment toward cardiovascular lineages; and (v) expression of ROR2 in the entire region of the primitive streak in embryonic day 7.5 mouse embryo and subsequent ROR2 mutation in mice leading to defects in somitogenesis and cardiogenesis (27, 28). To formally show that QP cells also exist in utero is ethically impermissible, as it would require access to early human embryos to comprehensively screen for ROR2 and CD13 expression in early human development (i.e., during primitive streak and lateral plate mesoderm formation). Nonetheless, the identification of cells that can generate three major cell types in the heart provides a unique opportunity to investigate the mechanisms that regulate the onset of human cardiac development as well as those that control their specification to the cardiac and vascular cells.

The role of the ROR2 protein has been studied in developmental processes, cell migration, and polarity (29, 30). It has been shown that ROR2 is expressed in the entire primitive streak region during mouse embryonic development and later in the developing limbs, brain, heart, and lungs (27). In humans, mutations in the ROR2 gene have been associated with autosomal-recessive Robinow syndrome, characterized by short stature, mesomelic limb shortening, abnormal craniofacial features, and distinct cardiac anomalies affecting the myocardium (31). The observed phenotypes arising from deficient or mutated ROR2 emphasizes its essential roles in morphogenetic and developmental processes.

Although the potential of hESCs to generate cardiovascular cells is indisputable, a set of challenges remains that limit the therapeutic application of hESC-derived cells. A major concern is their capacity to from teratomas after transplantation (32). The progenitor population we isolated based on the expression of distinct surface markers did not form teratomas when transplanted into mouse or human hearts. On the contrary, the population characterized by absence of the QP surface proteins resulted in teratoma formation upon transplantation into mouse or human hearts, which indicates that pluripotent stem cells can remain in culture even after 5 d of differentiation.

Another significant challenge to clinical application relates to the fate of the hESC-derived cardiac cells upon transplantation (12). Several investigators have reported engraftment of hESC-derived cells in infarcted mouse, rat, guinea pig, and pig hearts (14, 33, 34). Aside from the recent report of electromechanical integration of hESC-derived cardiomyocytes into guinea pig hearts, careful examination of animal models has revealed that the transplanted cells form islands of nascent myocardium within the scar zone (12). Furthermore, the rapid heart rate of mice (∼600 beats/min) may prevent the human cardiac cells, which have an intrinsic rate of 60 to 100 beats/min, from keeping pace with the mouse cardiomyocytes. In our experiments involving QP cell transplantation, we failed to see coupling of these cells within the mouse heart. In contrast, transplantation of QP cells into the human fetal heart revealed maturation, migration, coupling with resident cardiomyocytes, and electrophysiological activity in concert with the host myocardium.

Our findings clarify the ambiguity regarding the fate of transplanted hESC-derived cardiovascular cells. We show here that cardiovascular progenitors generated from hESCs engraft into mouse hearts, but fail to integrate. However, when transplanted into a human fetal heart tissue, they integrate into the host myocardium. A major limitation of the described model is that it is not amenable to a variety of physiological activities (i.e., hemodynamics or sinoatrial and atrioventricular conduction), the lack of which may influence the development of hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors. Fetal hearts also have much less developed connective tissue, which may promote integration of the QP cells that would be absent in adult hearts. Additionally, the present model represents transplantation in an uninjured heart, which may be a different environment for engraftment than an injured heart, and, moreover, does not allow us to investigate whether the engrafted cells could provide any functional improvement after injury. Nevertheless, the data herein establish the transplantability of hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors into human fetal hearts as a proof of concept of functional allogeneic integration.

Taken together, the data presented in this article suggest that hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors, defined by four surface markers, can structurally and functionally integrate into the electrical syncytia of human fetal heart tissue upon transplantation. Additionally, our finding of ROR2 as an early marker for cardiac lineage specification highlights a previously unknown role of ROR2 expression in cardiac development. Further research to delineate the mechanism by which ROR2 is involved in early cardiovascular progenitor formation is warranted. These valuable results provide the basis for future hESC-based cardiac therapy by identification of a progenitor population capable of engraftment and regeneration without risk of teratoma formation.

Materials and Methods

Human ES cells were maintained in standard ES culture as described. EBs were differentiated in the presence of Wnt 3a, BMP4, VEGF, activin A, sFz 8, FGF8, and Wnt11 Tables S3 and S4. Fetal heart tissues were obtained from Advanced Bioscience Resources. The Stanford institutional review board approved the use of one fetal heart for transplantation into a mouse ear, followed by injection of hESC-derived cardiovascular progenitors. A more detailed discussion is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yoav Soen for valuable advice, Dr. Mirko Corselli for his help in immunostaining, Libuse Jerabek for excellent laboratory management, and members of the I.L.W laboratory for advice and assistance. This work was supported by California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Grant RCI 00354 (to I.L.W); National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Fellowship 5T32 HL00708; an American College of Cardiology/Pfizer Career Development Award (to R.A.); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to S.R.A.); and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (to R.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1220832110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bergmann O, et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324(5923):98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porrello ER, et al. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331(6020):1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segers VF, Lee RT. Stem-cell therapy for cardiac disease. Nature. 2008;451(7181):937–942. doi: 10.1038/nature06800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Heart regeneration. Nature. 2011;473(7347):326–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soonpaa MH, Koh GY, Klug MG, Field LJ. Formation of nascent intercalated disks between grafted fetal cardiomyocytes and host myocardium. Science. 1994;264(5155):98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.8140423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagers AJ, Weissman IL. Plasticity of adult stem cells. Cell. 2004;116(5):639–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balsam LB, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004;428(6983):668–673. doi: 10.1038/nature02460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda K, Yuasa S. Stem cells as a source of regenerative cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2006;98(8):1002–1013. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218272.18669.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbel G, et al. Methods for human embryonic stem cells derived cardiomyocytes cultivation, genetic manipulation, and transplantation. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;660:85–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-705-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kattman SJ, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(2):228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453(7194):524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laflamme MA, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(9):1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue T, et al. Functional integration of electrically active cardiac derivatives from genetically engineered human embryonic stem cells with quiescent recipient ventricular cardiomyocytes: Insights into the development of cell-based pacemakers. Circulation. 2005;111(1):11–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151313.18547.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiba Y, et al. Human ES-cell-derived cardiomyocytes electrically couple and suppress arrhythmias in injured hearts. Nature. 2012;489(7415):322–325. doi: 10.1038/nature11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ardehali R, et al. Overexpression of BCL2 enhances survival of human embryonic stem cells during stress and obviates the requirement for serum factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(8):3282–3287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019047108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filipczyk AA, Passier R, Rochat A, Mummery CL. Regulation of cardiomyocyte differentiation of embryonic stem cells by extracellular signalling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64(6):704–718. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6523-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drukker M, et al. Isolation of primitive endoderm, mesoderm, vascular endothelial and trophoblast progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):531–542. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kataoka H, et al. Expressions of PDGF receptor alpha, c-Kit and Flk1 genes clustering in mouse chromosome 5 define distinct subsets of nascent mesodermal cells. Dev Growth Differ. 1997;39(6):729–740. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1997.t01-5-00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.David R, et al. MesP1 drives vertebrate cardiovascular differentiation through Dkk-1-mediated blockade of Wnt-signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(3):338–345. doi: 10.1038/ncb1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srivastava D. Making or breaking the heart: from lineage determination to morphogenesis. Cell. 2006;126(6):1037–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacot JG, et al. Cardiac myocyte force development during differentiation and maturation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1188:121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fey TA, et al. Improved methods for transplanting split-heart neonatal cardiac grafts into the ear pinna of mice and rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1998;39(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(97)00106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billingham M, Warnke R, Weissman IL. The cellular infiltrate in cardiac allograft rejection in mice. Transplantation. 1977;23(2):171–176. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197702000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roell W, et al. Engraftment of connexin 43-expressing cells prevents post-infarct arrhythmia. Nature. 2007;450(7171):819–824. doi: 10.1038/nature06321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez-Dolado M, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425(6961):968–973. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nygren JM, et al. Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells generate cardiomyocytes at a low frequency through cell fusion, but not transdifferentiation. Nat Med. 2004;10(5):494–501. doi: 10.1038/nm1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomi M, et al. Loss of mRor1 enhances the heart and skeletal abnormalities in mRor2-deficient mice: Redundant and pleiotropic functions of mRor1 and mRor2 receptor tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(24):8329–8335. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8329-8335.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwabe GC, et al. Ror2 knockout mouse as a model for the developmental pathology of autosomal recessive Robinow syndrome. Dev Dyn. 2004;229(2):400–410. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda T, et al. Expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase genes, Ror1 and Ror2, during mouse development. Mech Dev. 2001;105(1-2):153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minami Y, Oishi I, Endo M, Nishita M. Ror-family receptor tyrosine kinases in noncanonical Wnt signaling: Their implications in developmental morphogenesis and human diseases. Dev Dyn. 2010;239(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Afzal AR, et al. Recessive Robinow syndrome, allelic to dominant brachydactyly type B, is caused by mutation of ROR2. Nat Genet. 2000;25(4):419–422. doi: 10.1038/78107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee AS, et al. Effects of cell number on teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(16):2608–2612. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandes S, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes engraft but do not alter cardiac remodeling after chronic infarction in rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49(6):941–949. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kehat I, et al. Electromechanical integration of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1038/nbt1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.