Abstract

Impairments in pituitary FSH synthesis or action cause infertility. However, causes of FSH dysregulation are poorly described, in part because of our incomplete understanding of mechanisms controlling FSH synthesis. Previously, we discovered a critical role for forkhead protein L2 (FOXL2) in activin-stimulated FSH β-subunit (Fshb) transcription in immortalized cells in vitro. Here, we tested the hypothesis that FOXL2 is required for FSH synthesis in vivo. Using a Cre/lox approach, we selectively ablated Foxl2 in murine anterior pituitary gonadotrope cells. Conditional knockout (cKO) mice developed overtly normally but were subfertile in adulthood. Testis size and spermatogenesis were significantly impaired in cKO males. cKO females exhibited reduced ovarian weight and ovulated fewer oocytes in natural estrous cycles compared with controls. In contrast, ovaries of juvenile cKO females showed normal responses to exogenous gonadotropin stimulation. Both male and female cKO mice were FSH deficient, secondary to diminished pituitary Fshb mRNA production. Basal and activin-stimulated Fshb expression was similarly impaired in Foxl2 depleted primary pituitary cultures. Collectively, these data definitively establish FOXL2 as the first identified gonadotrope-restricted transcription factor required for selective FSH synthesis in vivo.

FSH is a dimeric glycoprotein produced by anterior pituitary gonadotrope cells. Defects in FSH synthesis or action cause infertility in women and female rodents due to an arrest in ovarian follicle maturation (1–6). FSH deficiency similarly impairs spermatogenesis in men and male rodents, but the ultimate impact on fertility depends on the species and the nature of the lesion (3, 6–14).

Elevated FSH is observed clinically and is used as a serum biomarker of diminished or diminishing ovarian follicle reserve in the diagnosis of menopause and premature ovarian failure (15–18). In these contexts, increases in FSH most often reflect augmented hypothalamic GnRH and/or intrapituitary activin signaling in the face of reduced negative feedback regulation by estrogens and inhibins from the depleted follicle pool (19–22). Both GnRH and activins stimulate FSH synthesis via the transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of its β-subunit (FSHB/Fshb) (23–30). Abnormally low FSH is also associated with absent or diminished fertility and in rare cases is directly linked to loss-of-function mutations in the FSHB gene (4, 5, 7, 8). Other genetic causes of isolated FSH deficiency are largely unknown (10, 31–33), in part because of our incomplete understanding of mechanisms of FSH synthesis and secretion.

Research over the past decade using immortalized murine gonadotrope-like cells, LβT2, has provided insight into mechanisms controlling FSHB/Fshb subunit transcription, particularly in response to activins (34). Based on our own and others' work (eg, Refs. 35–40), we developed a model whereby activins stimulate the formation of complexes of SMAD (homolog of Drosophila mothers against decapentaplegic) proteins (SMADs 2, 3, and 4) and the forkhead transcription factor forkhead protein L2 (FOXL2) to drive Fshb transcription via conserved and species-specific cis-elements in the proximal promoter.

Foxl2 expression is restricted to developing eyelids, ovarian granulosa cells, and pituitary thyrotrope and gonadotrope cells (41, 42). Global deletion of the single exon Foxl2 gene in mice causes craniofacial (eyelid) defects, impaired ovarian folliculogenesis, and perinatal lethality (43, 44). Mutations in the FOXL2 gene similarly cause eyelid malformations and, in some cases, premature ovarian failure in blepharophimosis, ptosis, and epicanthus inversus syndrome patients (45–47). Recently, reductions in pituitary FSH immunoreactivity and Fshb mRNA levels were reported in 3-week-old male and female Foxl2−/− mice, respectively (48). Although these data appear consistent with FOXL2's presumptive role in activin-stimulated Fshb transcription, there are shortcomings of this animal model that preclude any definitive conclusions regarding the pituitary-specific function of FOXL2.

First, Foxl2−/− females show severe ovarian defects due to FOXL2 ablation in granulosa cells, which might indirectly impact FSH synthesis. Second, 50%–95% of Foxl2−/− mice die before weaning (43, 44). This high rate of perinatal mortality limited the analysis of pituitary function to only small numbers of prepubertal mice in Ref. 48. Third, Foxl2−/− mice have hypoplastic pituitaries, with decreased cell numbers and increased cell density. Surviving animals exhibit general defects in pituitary development, because gene ablation affects pituitary cell lineages that do not express Foxl2. For example, there are increases in the numbers of ACTH- and GH-producing cells in Foxl2−/− males and decreased pituitary Gh and prolactin (Prl) mRNA expression in Foxl2−/− females. FOXL2 is first detected in developing murine anterior pituitary at embryonic day (E)11.5 and is implicated in cellular differentiation (49). Thus, at present, it is unclear whether the observed effects on Fshb expression in Foxl2−/− mice are cell autonomous and/or the result of more generalized defects in pituitary gland development.

To directly test the hypothesis that FOXL2 is required for FSH synthesis in vivo, we generated gonadotrope-specific Foxl2 knockout (KO) mice using a Cre/lox approach. These conditional KO (cKO) mice develop normally and survive into adulthood. However, both male and female cKO mice are FSH deficient and subfertile, establishing FOXL2 as an essential and cell autonomous regulator of Fshb expression in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

M199 (Medium 199) and Hank's Balanced Salt Solution media, fetal bovine serum (FBS), normal donkey serum, gentamycin, Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG, TRIzol reagent, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey antirabbit/594 donkey antigoat antibodies, β-tubulin antibody (32-2600, clone 2-28-33), and ProLong Gold Antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole were from Invitrogen (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by IDT (Coralville, Iowa). Deoxynucleotide triphosphates were from Wisent Inc (St-Bruno, Québec, Canada). Protease inhibitor tablets were from Roche (Indianapolis, Indiana). Equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) (G4877), human CG (hCG) (C1063), hyaluronidase (H3884), SB431542, pancreatin, collagenase, and FOXL2 (F0805), and β-actin (A5316) antibodies were from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri). FOXL2 (IMG3228) antibody was from Imgenex (San Diego, California). FSH antibody (lot no. AFP7798_ 1289P) was from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Bethesda, Maryland). Lutropin β (LH) antibody (sc-7824) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, California). Tissue-Tek OCT compound was from Sakura Finetek Europe B.V. (Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands). Human recombinant activin A was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minnesota). DNA/RNA AllPrep kit was from QIAGEN (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Tyramide signal amplification/fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) kit was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, Massachusetts). FOXL2 antibody directed against the C terminus of the protein was custom ordered from Eurogentec (Liège, Belgium) as described in Ref. 41. Biotinylated antirabbit secondary antibody and Fab fragment goat antirabbit antibody were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, Pennsylvania). TSHβ primary rabbit antibody was from the National Hormone and Peptide Program (Torrance, California).

Animals

Gonadotrope-specific Foxl2 KO models (cKO) were generated by crossing Foxl2flox/flox (50) and GnRH receptor IRES Cre (GRIC) (51) mice. For gonadotrope purification experiments, control (Foxl2+/+;GnrhrGRIC/+;Rosa26EYFP/+) and cKO (Foxl2flox/flox;GnrhrGRIC/+;Rosa26EYFP/+) animals were generated by introducing the Rosa26-stop-EYFP (enhanced YFP) allele (mice acquired from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (52). Animals were housed on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle and were given ad libitum access to food and water. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of McGill University.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Tissues from 6- to 8-week-old mice were harvested and processed individually. Briefly, tissues were homogenized in TRIzol, and RNA was extracted. Reverse transcription was performed on 2 μg of deoxyribonuclease-treated RNA as previously described (53) and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) carried out on cDNA using SYBRgreen Supermix in a Corbett Rotorgene 6000 qPCR machine (Corbett Life Science, Valencia, CA). mRNA expression of target genes, as determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method (54), was normalized to ribosomal protein L19 (Rpl19) as previously described (55). qPCR primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Table 1, Please see Supplemental Table 1 published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org.

Western blotting

Whole-cell protein extracts from pituitaries, testes, and ovaries were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors. Briefly, tissues were processed with a hand-held homogenizer (for pituitaries) or a Polytron, followed by 3 freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. Insoluble material was pelleted at 4°C at maximum speed for 30 minutes and supernatants collected and quantified before Western blotting as previously described (39).

Gonadotrope purification by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Whole pituitaries collected from 8- to 10-week-old male and female Foxl2flox/flox;GnrhrGRIC/+;ROSA26eYFP/+ mice were enzymatically dispersed as previously described (56). Cells were then filtered with a 40-μm nylon mesh, and FACS was performed on the resulting cell suspension using a FACSAria cell sorter. Subsequent analyses were performed on both yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)+ (ie, gonadotropes) and YFP- (ie, nongonadotropes) purified fractions. Total RNA and genomic DNA (gDNA) were extracted with the AllPrep kit according to the manufacturer's instructions followed by RT-qPCR analysis (see above section) of gene expression or PCR for detection of recombination (see Supplemental Table 1).

Immunofluorescence

Mice aged 10–13 weeks were euthanized with 200 mg/kg ip Avertin and transcardiacally perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Pituitaries were isolated and postfixed for 30 minutes in cold 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by subsequent 30-minute incubations in ice-cold ethanol (50%, followed by 75%) before paraffin embedding. Pituitary sections were deparaffinized in xylenes and progressively rehydrated in ethanol. For FOXL2 immunofluorescence, endogenous peroxidases were inactivated by incubation in 1.5% hydrogen peroxide followed by epitope unmasking by boiling in 10mM citric acid, pH 6.0. Sections were blocked in blocking solution from the tyramide signal amplification/FITC kit for 10 minutes and then incubated with a custom antibody against FOXL2 overnight at 4°C. Next, sections were incubated in a biotinylated antirabbit secondary antibody (1:100) followed by streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase and the FITC fluorophore, as per the manufacturer's directions. Colocalization of FOXL2 with TSHβ was performed as described above except blocking was performed by using a Fab fragment goat antirabbit antibody (1:100) for 30 minutes followed by a 1-hour incubation at room temperature with a TSHβ primary rabbit antibody (1:1000). The specimens were then incubated with tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated antirabbit antibodies as described above. For FSH and LH immunofluorescence, deparaffinized and rehydrated pituitary sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) as described (57). Sections were incubated with 5% normal donkey serum for 1 hour at room temperature and then with primary antibodies (FSH, 1:500; LHβ, 1:500) overnight at 4°C. All washing steps were performed in PBS-0.1%/Tween 20 followed by incubation with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

Fertility assessment

Eight-week-old male and female control and cKO mice were paired with wild-type C57BL/6 mice for 6 months (n = 7 pairs/genotype/sex). Breeding cages were monitored daily and dates of birth and litter sizes recorded. Pups were killed at 2 weeks of age. At the end of the breeding trials, sera, pituitaries, and gonads were harvested and snap frozen. Several animals were perfused and their pituitaries fixed for histological analyses.

Reproductive organ weights

Eight- to 13-week-old animals were euthanized and weighed. Uteri and ovaries of metestrus/diestrus-staged females, as assessed by vaginal cytology, were harvested, as were testes, epididymides, and seminal vesicles from males. All organs were kept at room temperature and weighed on a precision balance within 1 hour of harvesting.

Histology and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase 2′-deoxyuridine, 5′-triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) analyses

Reproductive organs from 8- to 13-week-old mice were dissected and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (for ovaries) or Bouin's fixative (for testes) at room temperature. Tissues were paraffin embedded and sectioned (5 μm). Hematoxylin-eosin (HE)-stained ovarian and testicular sections were analyzed using light microscopy. Testis sections were subjected to TUNEL analysis (ApopTag Fluorescein in Situ Apoptosis detection kit; Chemicon, Temecula, California). A serial sectioning protocol was used for corpora lutea (CL) counts, as described (58).

Sertoli cell (SC) counts

The left testis from adult males used for sperm count analyses was fixed in formalin, paraffin embedded, and processed for immunofluorescence. SCs were identified by staining their cytoskeleton with an antibody against β-tubulin (1:300), which resulted in a radiating pattern from the base of the seminiferous tubules to the lumen. Additionally, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole nucleic acid staining enhanced their distinctive nucleus (with often visible nucleolus) and position at the periphery of the tubules. For each animal, 8 imaging fields (approximately 300 SCs in total) were taken at ×20 magnification and SCs counted in round or nearly round seminiferous tubule cross-sections using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) by an investigator blinded to the animal genotype. Average numbers of SCs per tubule were calculated for each animal.

Sperm analysis

Eight- to 13-week-old males were killed and the left caudal epididymides dissected. The tissue was cut 5 times with a scalpel and sperm allowed to disperse for 8 minutes in warm M199 media supplemented with 3-mg/mL BSA. Sperm dilutions were subjected to computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA) using a TOX IVOS automated semen analyzer (Hamilton Thorne, Beverly, Massachusetts). A minimum of 500 sperm were assayed by CASA per animal. The right caudal epididymis and testis were immediately snap frozen and saved for homogenization-resistant sperm counts with a hematocytometer. Tissue homogenization was performed on ice in 0.9% NaCl with 0.1% Thimerosal/0.5% Triton X-100 (for cauda epididymis) or 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (for testis) for 2 × 15 seconds at 30-second intervals at Polytron power setting 5.

Puberty onset and estrous cyclicity

After weaning at post-natal day 21, control and cKO females were monitored daily for vaginal canalization (opening) to assess puberty onset. Once vaginal opening was observed, estrous cyclicity was assessed by daily vaginal swabbing for a minimum of 21 consecutive days. Metestrus and diestrus were classified into a single stage and characterized by the presence of leukocytes. A cycle was operationally defined as the observation of proestrus, estrus, metestrus/disestrus in sequence. Both methods were performed as described (59).

Superovulation with exogenous gonadotropins

Before lights off, female control or cKO mice (aged 23–28 d) were injected ip with 5 IU of eCG, followed 48 hours later by 5 IU of hCG. Animals were killed 12–14 hours after hCG and oocytes recovered by microdissection after puncturing of the ampullary region of the oviduct. Cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were harvested and incubated at 37°C with hyaluronidase (0.5 mg/mL) for 10 minutes with occasional shaking. Oocytes were then counted on an inverted microscope.

Natural mating/ovulation experiment

Nine-week-old females were housed with C57BL/6 proven breeder males and inspected for vaginal plugs every morning before 7:30 am. Once mating was confirmed, animals were immediately killed (before 10:00 am) and sera, ovaries, and oviducts (for COC microdissection) collected. Oocytes were counted and the ovaries fixed in neutral-buffered formalin for histological analyses and CL counting.

Hormone measurements

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture in the same 8- to 13-week-old animals used for reproductive organ analyses (above), stored at room temperature for 1 hour, and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. Serum was collected and stored at −20°C until submitted to the Ligand Assay and Analysis Core of the Center for Research in Reproduction at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia). LH and FSH were measured by multiplex ELISA. Total testosterone and estradiol were measured by ELISA (Calbiotech, Spring Valley, California) and RIA (Siemens, Malvern, Pennsylvania), respectively.

Primary pituitary cultures and adenoviral infection

Whole pituitaries collected from 8- to 10-week-old Foxl2flox/flox mice (for ex vivo recombination experiments) or female cKOs were enzymatically dispersed and plated in culture as previously described (56). Cells were cultured in 10% FBS/M199 medium for 48 hours before infection with adenovirus expressing GFP or Cre-IRES-eGFP (enhanced GFP) at a multiplicity of infection of 60. Adenoviruses were obtained from the Baylor College of Medicine Vector Development Laboratory (Houston, Texas). After 24 hours, cells were washed with serum-free medium and treated with 1nM activin A in 2% FBS/M199 for 24 hours. Total RNA and gDNA were analyzed by RT-qPCR for gene expression or PCR for detection of recombination (see Supplemental Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed as indicated in the figure or table legends using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, California). Significance was assessed relative to P < .05.

Results

Foxl2 mRNA and FOXL2 protein expression are depleted in cKO gonadotropes

We generated gonadotrope-specific Foxl2 cKO mice by crossing “floxed” Foxl2 (Foxl2flox/flox) and GRIC lines (50, 51). The latter directs Cre recombinase expression to pituitary gonadotropes and male germ cells. Therefore, matings were designed so that the Cre allele was contributed by the female parent. Animals with varying genotypes resulting from crosses of Foxl2flox/flox males and Foxl2flox/+;GnrhrGRIC/+ females were born at the expected Mendelian ratios (data not shown). Foxl2flox/flox;Gnrhr+/+ and Foxl2flox/flox;GnrhrGRIC/+ mice served as controls and cKOs, respectively. Limited analyses were also conducted with Foxl2flox/+;GnrhrGRIC/+ mice. Because these animals resembled controls, there were no clear effects of haploinsufficiency (data not shown).

In adult cKO animals, recombination of the Foxl2 locus was detected in whole pituitary but not in tail or ovarian DNA (Figure 1A). The extent of recombination in pituitary was consistent with the relatively small proportion of gonadotrope cells (5%–10%) in the anterior lobe. Recombination of the Foxl2 locus was not observed in 7 other tissues but was detected in cKO testes and epidydimides (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1A), because GRIC drives Cre activity in male germ cells (51). This was not a concern, because FOXL2 is not expressed in the testis (Ref. 60; see also Supplemental Fig. 1C). Foxl2 mRNA and FOXL2 protein levels were significantly depleted in whole pituitaries of male and female cKOs (Figure 1, B and C). Immunofluorescence analysis of pituitary sections further demonstrated the dramatic loss of FOXL2 protein in cKO mice (Figure 1D, compare top 2 panels) and that residual FOXL2 was predominantly in thyrotrope cells (Figure 1D, lower right panel). To provide a more quantitative assessment of cell-specific recombination efficiency and Foxl2 knockdown, we introduced a Cre-activated reporter allele to facilitate purification of gonadotropes from control (Foxl2+/+;GnrhrGRIC/+; Rosa26EYFP/+) and cKO (Foxl2flox/flox;GnrhrGRIC/+;Rosa26EYFP/+) mice. Recombination was nearly complete in FACS-sorted gonadotropes (YFP+) in cKOs of both sexes and was absent in nongonadotropes (YFP−; Figure 1E). Analysis of RNA from the same cells showed the enrichment of Foxl2 mRNA in gonadotropes relative to nongonadotropes of control mice (Figure 1F). This difference was abolished in cKO mice, reflecting the near complete ablation of Foxl2 expression in gonadotropes of cKO mice. Importantly, ovarian Foxl2 mRNA and FOXL2 protein expression were unaffected in cKO relative to control females (Supplemental Figure 1, B and C). cKO mice developed overtly normally, did not display craniofacial defects, and had body sizes and weights that were indistinguishable from controls (data not shown). Collectively, these data show that recombination of the floxed Foxl2 allele was both efficient and specific.

Figure 1.

In vivo recombination of the Foxl2 locus is restricted gonadotropes and testes of cKO mice. (A) PCR detection of floxed and recombined Foxl2 alleles in gDNA isolated from pituitary, testis, ovary, and tail of control and cKO animals. (B) RT-qPCR detection of Foxl2 mRNA levels in whole pituitaries of control and cKO mice (n = 10/group). All data here and in subsequent figures are means (±SEM), and an asterisk indicates statistical significance with P < .05 by t test (unless stated otherwise). (C) Pituitary FOXL2 protein expression in control and cKO mice as assessed by immunoblot (IB). Pooled protein lysates (100 μg) from 3 pituitaries per genotype per lane. Duplicates are shown for each genotype. LβT2 cell lysates were included as a positive control. ACTB, β-Actin. (D) Immunofluorescence for FOXL2 (green) and TSHβ (red) in pituitary sections from adult control (left) and cKO (right) mice. Arrows indicate examples of double-labeled cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) PCR detection of floxed, recombined, and wild-type (WT) Foxl2 alleles in gDNA isolated from FACS-purified pituitary cells of control (Foxl2+/+;GnrhrGRIC/+;Rosa26EYFP/+) and cKO (Foxl2 flox/flox;Gnrhr GRIC/+;Rosa26EYFP/+) mice. YFP−, Nongonadotropes; YFP+, gonadotropes. (F) Foxl2 mRNA levels from the sorted cells in E. Data are from 5 independent experiments (n = 3 using males and n = 2 using females), and pooled results were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA (Tukey post hoc).

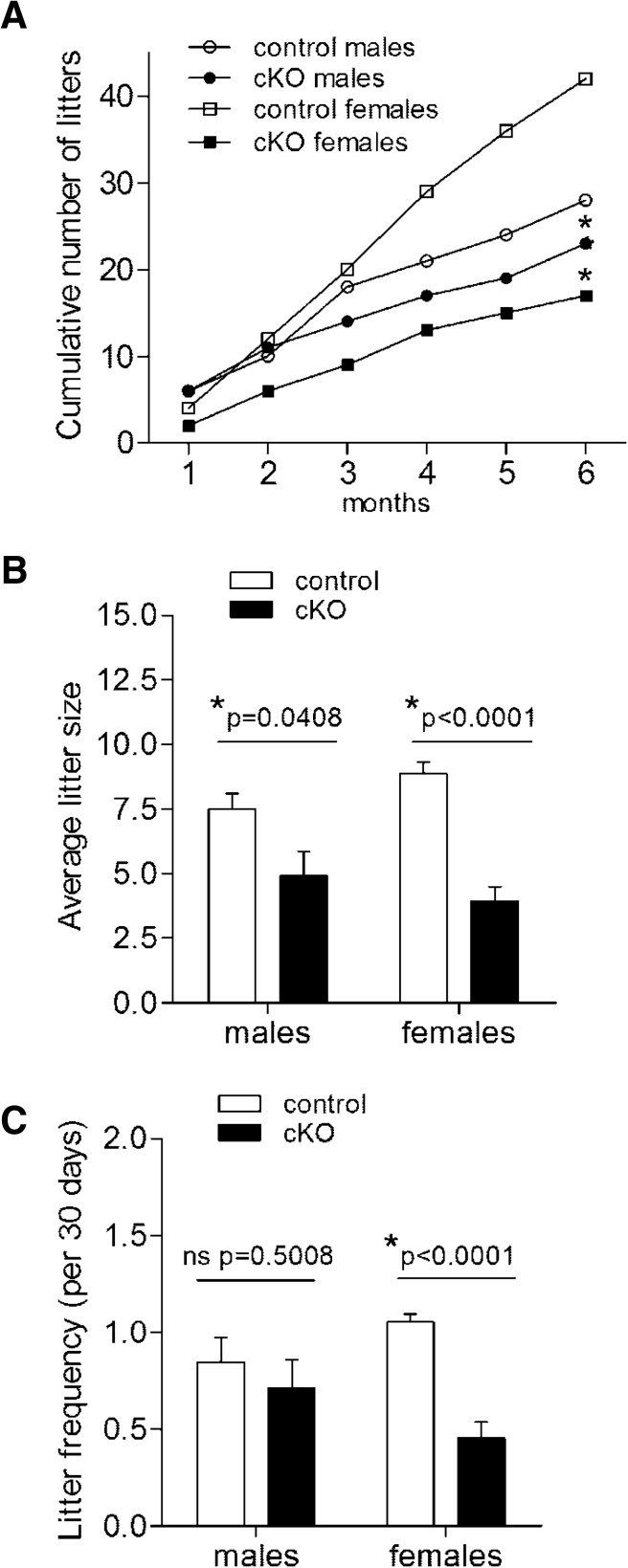

Foxl2 cKO mice are subfertile

Adult Foxl2 cKO males and females produced fewer total litters than controls when paired with wild-type C57BL/6 mice for a period of 6 months (Figure 2A). Average litter size was reduced by 35% and 56% in cKO males and females, respectively (Figure 2B). However, litter frequency was decreased in cKO females only (Figure 2C). cKO females showed a delay relative to controls in the number of days from pairing to delivery of the first litter, but this was not statistically significant (Supplemental Figure 2). Although fertility was uniformly impaired in females, we observed marked interindividual variation in cKO males. Four of 7 cKO males cumulatively produced 23 litters and 87% of all pups, whereas the other 3 cKO males only sired 4 total litters. Thus, gonadotrope-specific Foxl2 ablation causes subfertility in both sexes, although with variable penetrance in males.

Figure 2.

Foxl2 cKO mice are subfertile. (A) Cumulative numbers of litters over 6 months in control and cKO males and females (n = 7/genotype). At 6 months, an asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P < .05) between control and cKO groups within the same sex. (B) Average litter size per couple. (C) Litter frequency. In C, data from 1 cKO male were omitted, because he did not sire any pups.

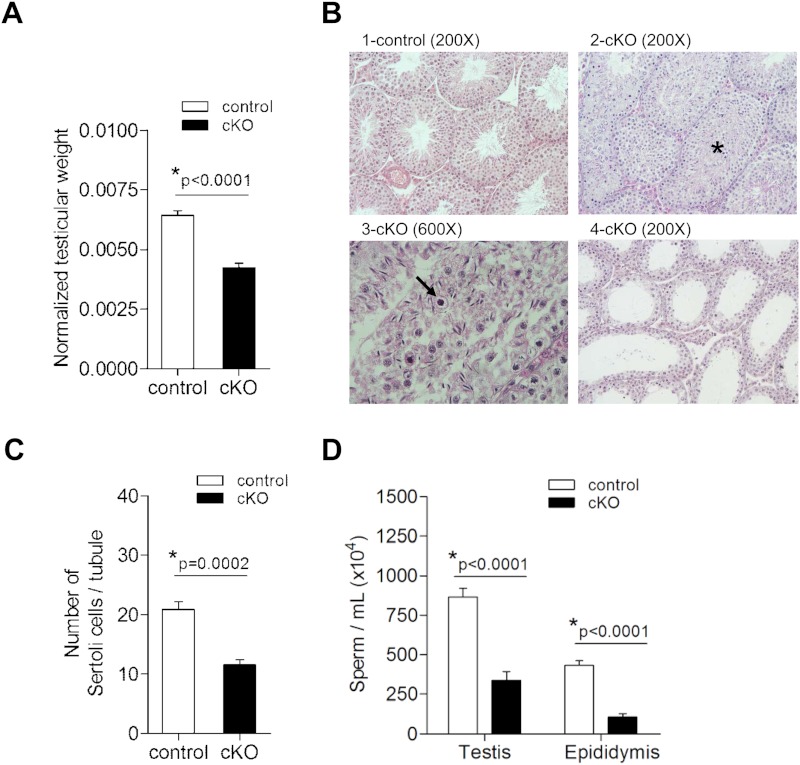

Spermatogenesis is disrupted in cKO males

Given their impaired fertility, we next investigated reproductive tract defects in cKO males. Testes, but not epididymal or seminal vesicle, weights were significantly reduced in 8- to 13-week-old cKOs relative to age-matched controls (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 3, A and B). Histopathological analysis of the testes of 7 cKO males revealed a range of spermatogenic defects, spanning from subtle (alterations in spermatogenic cell associations; Figure 3B, panel 3) to a complete arrest of spermatogenesis, as evidenced by a lack of luminal spermatids (Figure 3B, panel 4). Common to all cKOs were tubules showing a disorganization of the characteristic spermatogenic stages, retention of spermatids, sloughing of germ cells, and appearance of pyknotic cells (Figure 3B). Lumina were either reduced in size or absent in many cKO testes (Figure 3B, panel 2). cKO animals showed a 43% decrease in SC numbers (Figure 3C). We did not detect any increases in numbers of apoptotic cells, as revealed by TUNEL assay (data not shown). Decreased testes weights were also associated with 61% and 75% reductions in testicular and cauda epididymal sperm counts, respectively (Figure 3D). In 30% of sampled cKO males, we could not detect motile sperm, whereas the remaining 70% appeared to have normal sperm vigor and progression (Supplemental Table 2). These data demonstrate decreased SC number, impaired spermatogenesis, and variable asthenospermia in cKO males. Whether SC function is also impaired awaits further investigation.

Figure 3.

Testicular weights, SC numbers, and sperm count are reduced in cKO males. (A) Paired testicular weights (in grams) normalized to body weight (in grams) for adult control (n = 14) and cKO (n = 34) males. (B) HE-stained sections of testes from representative control and cKO males showing variable disruption of spermatogenesis. 1, Control testis with normal spermatogenesis with open lumens and all stages of spermatogenesis; 2, cKO testis with abnormal retention of spermatids as denoted by the asterisk; 3, cKO testis with pyknotic cells (arrow) and sloughed germ cells filling the lumen; 4, cKO testis with spermatogenesis arrested at meiosis; few to no haploid round spermatids observed. (C) SC counts from left testis of control and cKO males (n = 6/group). (D) Posthomogenization sperm counts from right testis and cauda epididymis of control (n = 11) and cKO (n = 10).

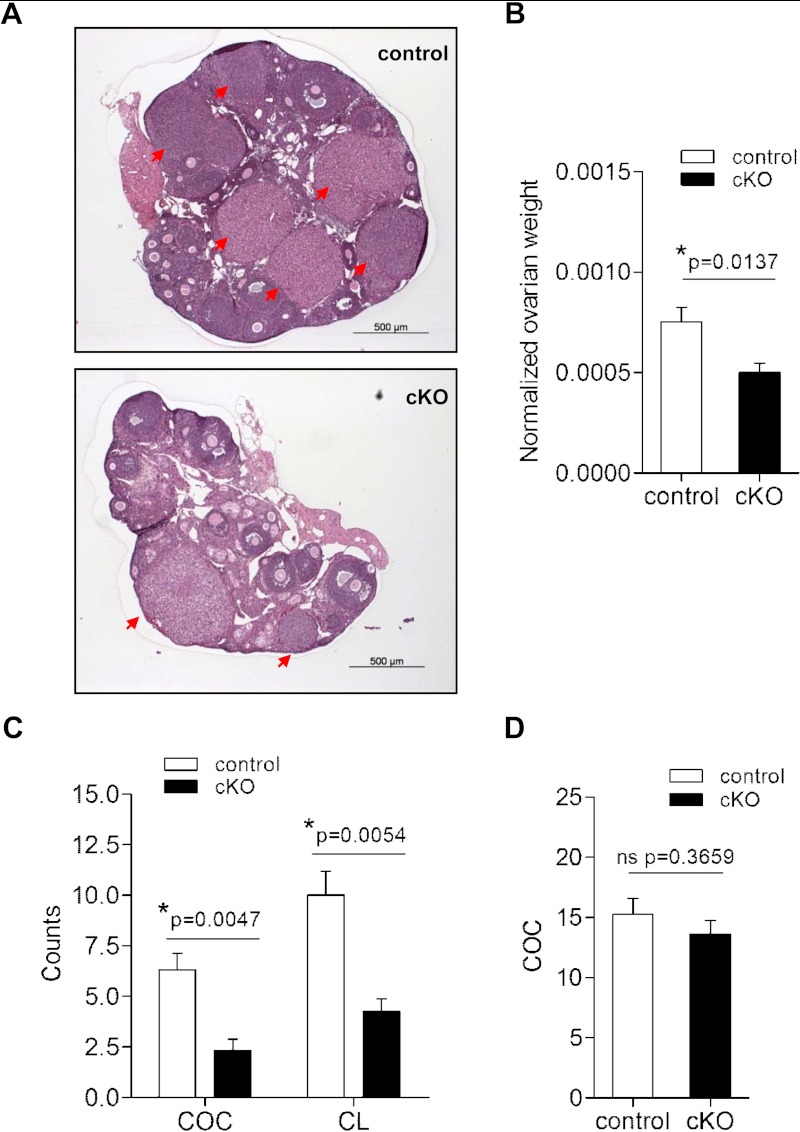

cKO females ovulate fewer follicles than controls

As described above, female cKOs produced smaller litters at a lower frequency than controls. Ovarian histology from 6- to 11-week-old cKO females revealed follicles at all stages of development, as well as the presence of CL (eg, Figure 4A). Nonetheless, ovarian, but not uterine, weights were decreased (by 34%) in cKO females relative to age-matched controls (Figure 4B and Supplemental Figure 4A). Although cKOs showed a slight delay in puberty onset (Supplemental Figure 4B), all sexually mature females exhibited vaginal cytology consistent with active estrous cyclicity (Supplemental Figure 5A). Indeed, we did not observe significant differences in the number of cycles per 5 days or percentage of time spent in each cycle stage between genotypes (Supplemental Figure 5, B and C). However, mice in this background strain, regardless of genotype, did not show robust 4- to 5-day cycles, and some cKO females appeared to spend extended periods of time in estrus (Supplemental Figure 5A).

Figure 4.

Ovarian weights and ovulation rates are decreased in cKO females. (A) HE-stained ovarian sections from representative 8-week-old control and cKO females. Red arrows indicate CL. (B) Paired ovarian weight (in grams) normalized to body weight (in grams) in metestrous/diestrous control (n = 9) and cKO (n = 12) females aged 8–13 weeks. (C) COC and CL counts after mating in control (n = 10 for COC, n = 5 for CL) and cKO (n = 6 for COC, n = 4 for CL) females. (D) COC counts after exogenous gonadotropin stimulation in 24- to 28-day-old control and cKO females (n = 8/genotype). ns, nonsignificant.

To examine ovulation, we paired age-matched control (65.8 ± 1.3 d old) and cKO females (64.3 ± 1.6 d old) with wild-type males. After detection of vaginal plugs, we counted COCs present in the oviducts. We observed plugs in 78% (11/14) and 75% (6/8) of control and cKO females, respectively, with no difference between genotypes in the number of days between pairing and apparent mating (3.9 ± 0.8 vs 3.1 ± 0.7 d). However, cKO females ovulated fewer COCs than controls, and examination of ovaries from the same animals revealed proportionately fewer CL (Figure 4C). Although ovarian Foxl2 transcript and FOXL2 protein levels were normal (Supplemental Figure 1), and recombination of the Foxl2 locus was not detected in cKO ovaries (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1A), we nonetheless treated juvenile females with exogenous gonadotropins to rule out potential ovarian defects. When sequentially stimulated with eCG and hCG, cKO and control females ovulated similar numbers of COCs (Figure 4D). These data indicate that subfertility in cKO mice derived, at least in part, from a reduction in ovarian follicle development and/or ovulation but not a primary ovarian defect.

cKO mice are FSH deficient

The physiological data from both males and females were suggestive of gonadotropin deficiency. Indeed, serum FSH levels were significantly reduced in both cKO males and randomly-cycling cKO females relative to age-matched controls (Table 1). Similar results were observed in females from the breeding trials (data not shown) and those sampled on the morning of (presumptive) estrus in the postmating ovulation experiment described above (Supplemental Figure 6). In contrast, serum LH levels were increased 2.5-fold in cKO females (Table 1), whereas 17β-estradiol levels were equivalent in metestrus/diestrus-staged animals of the 2 genotypes (Supplemental Figure 7A). In cKO males, circulating LH levels were statistically decreased (Table 1), whereas serum testosterone levels were unchanged (Supplemental Figure 7B).

Table 1.

Serum Gonadotropin Levels in Adult Males and Randomly-Cycling Females

| Measurement | Control | cKO | Statistical analysis by t test |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSH | |||

| Males | 245.2 ± 21.5 | 23.7 ± 2.1 | *P < .0001 |

| (n = 10) | (n = 12) | ||

| Females | 34.5 ± 9.6 | 11.9 ± 2.9 | *P = .0385 |

| (n = 14) | (n = 13) | ||

| LH | |||

| Males | 15.3 ± 1.9 | 7.4 ± 0.9 | *P = .0008 |

| (n = 14) | (n = 12) | ||

| Females | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | *P < .0001 |

| (n = 14) | (n = 13) |

Hormones (in nanograms per milliliter) were measured by multiplex ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Sample sizes are shown in parentheses.

Consistent with the circulating hormone data, FSHβ protein and Fshb mRNA expression were significantly reduced in pituitaries of cKO mice relative to controls as indicated by immunofluorescence and quantitative RT-PCR, respectively (Figure 5). Conversely, LHβ protein and Lhb mRNA were robustly expressed in both genotypes and sexes. Pituitary follistatin (Fst) mRNA levels were also reduced in cKO mice (Figure 5, B and C), whereas Gnrhr, chorionic gonadotropin α (Cga), GH (Gh), Prl, and TSHβ (Tshb) expression were unchanged (Figure 5, B and C, and Supplemental Figure 8). We did not observe any obvious effects of gene deletion on pituitary size or cell density (data not shown). Thus, loss of FOXL2 in gonadotropes caused FSH deficiency, likely secondary to a selective reduction in Fshb expression.

Figure 5.

Pituitary FSH synthesis is impaired in cKO mice. (A) Immunofluorescence for FSH (green) and LH (red) on pituitary sections from adult control and cKO mice (×400 magnification; scale bar, 50 μm). Mean (±SEM) mRNA level as assessed by RT-qPCR for the indicated genes from pituitaries of control and cKO (B) males and (C) females; n = 7–10/genotype. ns, nonsignificant.

FSH target gene expression is altered in gonads of cKO mice

We next examined the potential effects of FSH deficiency on gonadal gene expression. Secreted by SCs, androgen-binding protein (Abp) is important for testosterone-dependent sperm maturation, and its secretion can be stimulated by FSH (61, 62). Abp mRNA levels were similar between control and cKO mice (Supplemental Figure 9A). FSH down-regulates expression of its own receptor (Fshr) in rat SCs (63, 64). We observed a significant increase in Fshr mRNA levels in cKO testes (Supplemental Figure 9A). In females, FSH classically stimulates aromatase (Cyp19a1), LH receptor (Lhr), and cyclin D2 (Ccnd2) expression (65–67). Lhr and Ccnd2 mRNAs were significantly reduced in ovaries of cKO relative to control mice (Supplemental Figure 9B). There was also a nonsignificant trend for Cyp19a1 mRNA levels to be decreased in ovaries of randomly-cycling cKO females. Therefore, reductions in circulating FSH levels were associated with increased testicular Fshr mRNA and attenuated FSH target gene expression in the ovaries of cKO mice.

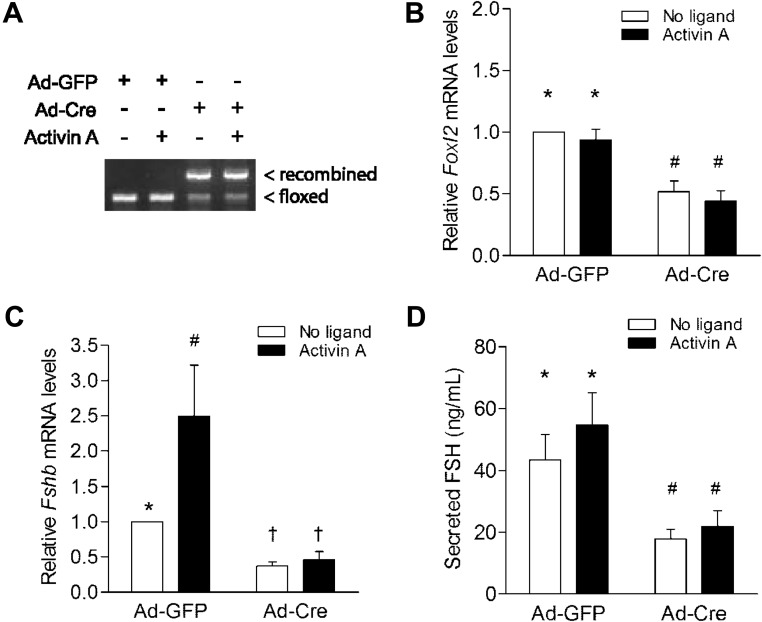

Ex vivo deletion of Foxl2 in primary pituitary cells reduces basal and activin A-induced FSH synthesis

We previously identified FOXL2 as a mediator of activin-regulated Fshb transcription in immortalized gonadotrope-like cells (35, 37, 68). To assess whether reduced pituitary Fshb mRNA expression in vivo might derive from impaired activin-induced Fshb transcription, we recombined the floxed Foxl2 loci in primary pituitary cultures from male Foxl2flox/flox mice. Cells were transduced with control (Ad [adenovirus]-GFP) or Cre-expressing (Ad-Cre) adenoviruses. Cre efficiently recombined the floxed Foxl2 alleles and significantly depleted Foxl2 mRNA expression in the cultures (Figure 6, A and B). In Ad-Cre-treated cells, basal Fshb mRNA expression was significantly depleted and activin A-induced Fshb expression completely blocked (Figure 6C). FSH, but not LH, concentrations in the culture media were similarly reduced in Ad-Cre relative to control cultures (Figure 6D and Supplemental Figure 10). We obtained comparable results with cultures from Foxl2flox/flox females (Supplemental Figure 11). Finally, we cultured pituitary cells from Foxl2flox/flox; GnrhrGRIC/+ (cKO) females (where recombination occurred in vivo) and observed similar (if not more pronounced) reductions in basal FSH secretion and Fshb mRNA expression (Supplemental Figure 12, B and C). Interestingly, LH concentrations were increased in cKO cultures (Supplemental Figure 12D). Because “basal” Fshb expression and FSH secretion are thought to depend upon endogenous activin B signaling in primary pituitary cultures (27, 69), these data suggest a fundamental role for FOXL2 in activin-regulated Fshb expression and FSH release in primary gonadotrope cells.

Figure 6.

Decreased Fshb transcription and FSH synthesis in primary pituitary cultures after ex vivo Foxl2 recombination. (A) Recombination of floxed Foxl2 in male primary pituitary cells. Ad-GFP, Adenovirus expressing GFP; Ad-Cre, adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase; floxed and recombined Foxl2 alleles are indicated. Mean (±SEM) relative (B) Foxl2 mRNA, (C) Fshb mRNA, and (D) secreted FSH levels in treated cultures from 5 independent experiments. Data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA (Tukey post hoc). Bars with different symbols were statistically different; those sharing symbols did not differ.

Discussion

Using a cKO approach, we show that ablation of the Foxl2 gene in pituitary gonadotropes causes a selective reduction in Fshb mRNA expression and associated FSH deficiency and subfertility in male and female mice. FOXL2 thus joins a select group of transcription factors, including early growth response 1 (for Lhb) and T-box 19 (for Pomc), required for cell type-specific expression of pituitary hormone-encoding genes (70, 71).

Our data provide the first definitive demonstration of FOXL2's cell autonomous role in FSH biosynthesis by gonadotropes and are consistent with our earlier in vitro observations (35, 37, 68). Indeed, the data collectively show a necessary role for FOXL2 in activin-stimulated Fshb subunit expression in both primary cells and immortalized gonadotrope cells. By extension, one might predict that FSH deficiency in cKO mice stems from impaired activin regulation of Fshb expression. However, we cannot rule out potential effects of Foxl2 ablation on gonadotrope development and/or activin-independent roles for FOXL2 in Fshb transcription. Nonetheless, normal Gnrhr, Lhb, and Cga mRNA expression in cKO mice argue against nonselective effects on gonadotrope development. The data from ex vivo recombination experiments further suggest that it is the absence of FOXL2 in adulthood rather than during development that explains the impairment in FSH synthesis. Ultimately, Foxl2 ablation in gonadotropes of adult mice in vivo will be required to address this hypothesis directly.

Similar to other FSH-deficient mouse models (3, 72), Foxl2 cKO males exhibit decreased testis size and oligospermia. Normal serum testosterone levels and testicular Abp mRNA levels (Supplemental Figures 7B and 9A) suggest that reduced sperm counts in cKO males are not likely the result of decreased intratesticular testosterone production or action. Instead, oligospermia more likely reflects the effects of diminished FSH signaling on SC function. Although we did not directly measure cell function in our animals, we did observe a marked reduction in SC number, which dictates spermatogenic potential (73, 74), in the cKO males. Similar data were reported in Fshb and activin type II receptor (Acvr2) global KOs (75, 76). Our results therefore indicate that FSH deficiency is associated with impaired SC endowment, resulting in oligospermia and subfertility in cKO males.

Like Fshb and Acvr2 KO males, many Foxl2 cKO males are fertile in the face of marked oligospermia. In apparent contrast to the other models, however, several Foxl2 cKO males were subfertile. At present, we can neither explain the difference between the models nor the incomplete penetrance of the phenotype in our mice. That said, it is notable that some Foxl2 cKO males display more dramatic effects on testicular (tubule) morphology and sperm motility than others. Although we neglected to assess testicular morphology and sperm counts in males used in the breeding trials, one might predict that subfertile males had these more extreme testicular anomalies. Circulating FSH levels are reduced by 90% in Foxl2 cKO males. Although this is a larger decline than observed in Acvr2 KOs (58%), it is clearly less than in Fshb KOs. Therefore, differences in the extent of FSH depletion do not likely explain the divergent fertility phenotypes between the 3 models. Moreover, FSH was uniformly low in Foxl2 cKO males regardless of their fertility status. The Cre allele used here (GRIC) is active in the male germ line (51). Therefore, we cannot completely rule out an effect of the gene deletion at the level of the testis itself (at least in some animals). However, the lack of testicular FOXL2 expression makes this possibility seem unlikely.

Interestingly, although their FSH levels are significantly depleted, Foxl2 cKO females exhibit apparent estrous cyclicity and are fertile. These data contrast with those of Fshb KO mice, which are infertile due to a block in folliculogenesis at the pre- or early-antral stage (3). Acvr2−/− females have a similar impairment in FSH production to Foxl2 cKO females but are infertile and show ovarian abnormalities, including increased follicular atresia and a near absence of CL (72). These data suggest that at least part of the infertility phenotype in Acvr2 KOs is attributable to loss of the receptor in the ovary. Indeed, activins regulate an array of ovarian processes (77–81). In contrast, there is no evidence that subfertility in Foxl2 cKO females derives from loss of FOXL2 function in the ovary. First, we detect control levels of Foxl2 mRNA and FOXL2 protein in ovaries from Foxl2 cKO females. Second, juvenile Foxl2 cKO females ovulate a similar number of oocytes as controls when treated with exogenous gonadotropins. Third, loss of Foxl2 in the ovary either disrupts follicle development/assembly or causes trans-differentiation of female into male somatic cell types (43, 44, 50, 82). Although the ovaries are smaller in cKO mice than in controls, follicle development appears qualitatively normal (ie, follicles at all stages are observed). We did note seminiferous tubule-like structures in a few rare instances (data not shown), but this was limited both in terms of the number of animals affected and the extent of trans-differentiation. We were unable to detect recombination of the floxed Foxl2 allele (by PCR) in the ovaries of any of the animals used in breeding trials or in 14 additional adult cKO animals (data not shown). Because tubule-like structures were never noted in controls, it is possible that the GRIC allele is expressed (perhaps transiently) in some ovarian cells in some animals. Nonetheless, given the rarity of tubule formation and the sensitivity of PCR to detect recombination, it is very unlikely that this had any effect on the observed ovarian and pituitary phenotypes. Collectively, these data indicate that ovarian development and physiology are normal in Foxl2 cKO females. We therefore conclude that female subfertility is principally a consequence of FSH deficiency and a corresponding impairment in ovarian follicle selection and/or growth.

Consistent with this idea, we observe decreases in classical markers of FSH action, including Ccnd2 and Lhr, in the ovaries of adult Foxl2 cKO females. Moreover, circulating LH levels are increased in cKO females relative to controls, which one would expect if there is diminished estrogen negative feedback from a reduced number of growing follicles. That said, we do not detect any significant differences in circulating 17β-estradiol levels or uterine weights in cKO females, although their ovarian Cyp19a1 mRNA levels tend to be lower than in controls. Fshb KO females similarly show elevated LH in the face of seemingly normal estradiol levels (3). Pituitary cultures from Foxl2 cKO females show increased LH secretion, suggesting an effect at the gonadotrope level. Because Lhb mRNA levels are unaltered, enhanced LH secretion might simply reflect increased dimerization of LHβ with CGA, in the face of reduced competition with FSHβ. Ultimately, the most direct indicator of impaired follicle growth is the reduced number of CL and ovulated oocytes in naturally-cycling cKO females after pairing with males. Thus, in Foxl2 cKO females, FSH levels are sufficient to support estrous cyclicity and fertility (unlike the case in Fshb KOs) but are insufficient to maintain quantitatively normal follicle selection and/or growth.

It is notable that FSH synthesis is reduced, but not absent, in Foxl2 cKO mice. Residual hormone could reflect incomplete recombination of floxed Foxl2 alleles in gonadotropes or FOXL2-independent FSH expression. The available data favor the latter possibility. First, the floxed alleles were efficiently recombined and Foxl2 mRNA levels significantly depleted in purified gonadotropes from cKO mice. Second, although it is possible that FOXL2 is expressed in a subpopulation of FSH-positive/GnRHR-negative cells (in which the Cre allele would not be active), most FOXL2-positive cells remaining in cKO mice are TSHβ-positive (and therefore thyrotropes). Finally, Foxl2−/− mice produce small amounts of FSH, showing that FOXL2 is not absolutely required for Fshb expression (48). Nonetheless, the underlying mechanisms cannot compensate for the loss of FOXL2.

Although data from cKO and Foxl2−/− mice converge to show a necessary role for FOXL2 in Fshb expression, there are important distinctions between the 2 models. Most relevant in the current context are apparent differences in pituitary development and hormone synthesis. Foxl2−/− mice show impairments in pituitary growth and in the expression of several hormone-encoding genes, including Fshb, Cga, Gh, and Prl. In cKO mice, pituitary size appears normal, and Fshb mRNA expression is uniquely affected. Although we have not definitely established the mechanisms underlying these differences, it seems likely that temporal and/or spatial characteristics of the gene deletion play a role. That is, FOXL2 protein is first expressed in nonproliferating cells of the developing murine anterior pituitary at E11.5 and is colocalized with CGA (49). Therefore, in Foxl2−/− mice, the gene is never expressed in the cells that will ultimately become terminally differentiated gonadotropes and thyrotropes. In contrast, the GRIC allele is first expressed at E12.75 and only in those cells committed to the gonadotrope lineage (51). Therefore, the later timing and/or more cell-restricted nature of the gene deletion appear to allow pituitaries of cKO mice to develop relatively normally and for effects to be limited to Fshb subunit regulation.

Juvenile female Foxl2−/− mice show decreases in pituitary Gnrhr, Cga, and Fst mRNA expression (48). These data are consistent with cell line experiments implicating FOXL2 in transcriptional regulation of these genes (42, 49, 83). Although we similarly observe decreases in pituitary Fst mRNA expression in adult male and female cKO mice, Gnrhr and Cga expression are unchanged. We did not examine pituitary gene expression in prepubertal animals and therefore cannot rule out the possibility that there is an early effect of Foxl2 deletion on Gnrhr and Cga expression that is then resolved later in life. It is also possible that the decline in Cga in Foxl2−/− mice reflects loss of FOXL2 function in thyrotropes rather than (or in addition to) gonadotropes. An examination of pituitary gene expression in Foxl2 cKO mice at different ages might help resolve these apparent discrepancies and thereby establish whether FOXL2 truly regulates the Gnrhr and Cga genes in vivo or whether the observed declines in Foxl2−/− mice reflect nonselective effects of gene ablation on gonadotrope and thyrotrope development.

Finally, although the data here clearly establish FOXL2's necessary role in murine Fshb expression, their relevance for human FSHB regulation is presently unresolved. Mechanisms of human FSHB transcription are poorly understood compared with mouse (34). That said, FOXL2 is expressed in human gonadotropes (84), and the protein can bind a conserved cis-element in the proximal FSHB promoter (35). One might therefore predict that loss-of-function mutations in the human FOXL2 gene would similarly cause FSH deficiency. Although more than 100 FOXL2 mutations and/or variants have been described (85–87), to our knowledge, there have been no systematic investigations of FSH synthesis in affected individuals (however, see Refs. 88–91). Ultimately, establishing FOXL2's role in human FSH production may require analysis of patients with bona fide loss-of-function mutations in both alleles (as described here in cKO mice). However, FOXL2 variants are rare and homozygous mutations are particularly uncommon (46, 91).

In summary, our data firmly establish FOXL2 as the first essential, cell-autonomous regulator of FSH synthesis in vivo. FSH deficiency in gonadotrope-specific Foxl2 KO mice causes oligospermia in males and impaired ovarian folliculogenesis and/or ovulation in females. Activins are potent regulators of FSH synthesis. Although in vitro data link activin signaling to Fshb transcription via the formation of SMAD/FOXL2 complexes at the proximal promoter, additional genetic evidence is needed to determine how loss of FOXL2 impairs Fshb mRNA expression and ultimately FSH synthesis in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hugh Clarke for help with the oocyte harvest protocol and Dr. Bernard Robaire and Dr. Cristian O'Flaherty for use of equipment and technical advice with CASA. Jérôme Fortin and Beata Bak provided helpful feedback on the manuscript. Dr. Reiner Veitia (Institut Jacques Monod, Paris, France) generously provided the FOXL2 antibody used in immunofluorescence. Dr. A.F. Parlow (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) provided the antibody for TSHβ. Finally, we dedicate this article to the late Dr. Wylie Vale, his pioneering research on activins and inhibins inspired our work.

This work was supported by operating funds from Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grants MOP 89991 (to D.J.B. and D.B.) and 211274 (to S.K.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R15-HD063469 (to B.S.E.), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft BO1743/2 (to U.B.). D.J.B. and S.T. were supported by a Chercheur-boursier (Senior) and a doctoral fellowship, respectively, from the Fonds de recherche en santé du Québec (FRSQ). S.T. was also funded by a McGill Faculty of Medicine internal studentship award. The Ligand Assay and Analysis Core of the Center for Research in Reproduction at the University of Virginia is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH (Specialized Cooperative Centers Program for Reproduction and Infertility Research) Grant U54-HD28934.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- Abp

- androgen-binding protein

- Acvr2

- activin type II receptor

- Ad

- adenovirus

- CASA

- computer-assisted sperm analysis

- Ccnd2

- cyclin D2

- Cga/CGA

- chorionic gonadotropin α

- cKO

- conditional KO

- CL

- corpora lutea

- COC

- cumulus-oocyte complex

- E

- embryonic day

- eCG

- equine chorionic gonadotropin

- eGFP

- enhanced GFP

- eYFP

- enhanced YFP

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FOXL2

- forkhead protein L2

- Fst

- follistatin

- GRIC

- GnRHR IRES Cre

- hCG

- human CG

- HE

- hematoxylin-eosin

- IRES

- internal ribosomal entry site

- KO

- knockout

- Lhr

- LH receptor

- M199

- Medium 199

- Prl

- prolactin

- RT-qPCR

- reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SC

- Sertoli cell

- SMAD

- homolog of Drosophila mothers against decapentaplegic

- TUNEL

- terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase 2′-deoxyuridine, 5′-triphosphate nick end labeling

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- 1. Aittomäki K, Dieguez Lucena J, Pakarinen P, et al. Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure. Cell. 1995;82:959–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Themmen APN, Huhtaniemi IT. Mutations of gonadotropins and gonadotropin receptors: elucidating the physiology and pathophysiology of pituitary-gonadal function. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:551–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumar TR, Wang Y, Lu N, Matzuk MM. Follicle stimulating hormone is required for ovarian follicle maturation but not male fertility. Nat Genet. 1997;15:201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matthews CH, Borgato S, Beck-Peccoz P, et al. Primary amenorrhoea and infertility due to a mutation in the β-subunit of follicle-stimulating hormone. Nat Genet. 1993;5:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Layman LC, Lee EJ, Peak DB, et al. Delayed puberty and hypogonadism caused by mutations in the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:607–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abel MH, Wootton AN, Wilkins V, Huhtaniemi I, Knight PG, Charlton HM. The effect of a null mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene on mouse reproduction. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1795–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lindstedt G, Nystrom E, Matthews C, Ernest I, Janson PO, Chatterjee K. Follitropin (FSH) deficiency in an infertile male due to FSHβ gene mutation. A syndrome of normal puberty and virilization but underdeveloped testicles with azoospermia, low FSH but high lutropin and normal serum testosterone concentrations. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1998;36:663–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Layman LC, Porto AL, Xie J, da Motta LA, da Motta LD, Weiser W, Sluss PM. FSHβ gene mutations in a female with partial breast development and a male sibling with normal puberty and azoospermia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3702–3707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tapanainen JS, Aittomaki K, Min J, Vaskivuo T, Huhtaniemi IT. Men homozygous for an inactivating mutation of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor gene present variable suppression of spermatogenesis and fertility. Nat Genet. 1997;15:205–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mantovani G, Borgato S, Beck-Peccoz P, Romoli R, Borretta G, Persani L. Isolated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) deficiency in a young man with normal virilization who did not have mutations in the FSHβ gene. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:434–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dierich A, Sairam MR, Monaco L, et al. Impairing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) signaling in vivo: targeted disruption of the FSH receptor leads to aberrant gametogenesis and hormonal imbalance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13612–13617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Diez JJ, Iglesias P, Sastre J, et al. Isolated deficiency of follicle-stimulating hormone in man: a case report and literature review. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1994;39:26–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murao K, Imachi H, Muraoka T, et al. Isolated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) deficiency without mutation of the FSHβ gene and successful treatment with human menopausal gonadotropin. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:2012.e17–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phillip M, Arbelle JE, Segev Y, Parvari R. Male hypogonadism due to a mutation in the gene for the β-subunit of follicle-stimulating hormone. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1729–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coulam CB, Ryan RJ. Premature menopause. I. Etiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133:639–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lenton EA, Sexton L, Lee S, Cooke ID. Progressive changes in LH and FSH and LH: FSH ratio in women throughout reproductive life. Maturitas. 1988;10:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goldenberg RL, Grodin JM, Rodbard D, Ross GT. Gonadotropins in women with amenorrhea. The use of plasma follicle-stimulating hormone to differentiate women with and without ovarian follicles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;116:1003–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones GS, De Moraes-Ruehsen M. A new syndrome of amenorrhae in association with hypergonadotropism and apparently normal ovarian follicular apparatus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;104:597–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sherman BM, West JH, Korenman SG. The menopausal transition: analysis of LH, FSH, estradiol, and progesterone concentrations during menstrual cycles of older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;42:629–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsai CC, Yen SSC. Acute Effects of intravenous infusion of 17β-estradiol on gonadotropin release in pre- and post-menopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971;32:766–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shaw ND, Histed SN, Srouji SS, Yang J, Lee H, Hall JE. Estrogen negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion: evidence for a direct pituitary effect in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1955–1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gill S, Sharpless JL, Rado K, Hall JE. Evidence that GnRH decreases with gonadal steroid feedback but increases with age in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2290–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Ortolano GA, Marshall JC, Shupnik MA. A pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulus is required to increase transcription of the gonadotropin subunit genes: evidence for differential regulation of transcription by pulse frequency in vivo. Endocrinology. 1991;128:509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dalkin AC, Burger LL, Aylor KW, et al. Regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene transcription by gonadotropin-releasing hormone: measurement of primary transcript ribonucleic acids by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assays. Endocrinology. 2001;142:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dalkin AC, Haisenleder DJ, Gilrain JT, Aylor K, Yasin M, Marshall JC. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene expression in female rats: actions on follicle-stimulating hormoneβ messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) involve differential expression of pituitary activin (β-B) and follistatin mRNAs. Endocrinology. 1999;140:903–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weiss J, Harris PE, Halvorson LM, Crowley WF, Jameson JL. Dynamic regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone-β messenger ribonucleic acid levels by activin and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in perifused rat pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1403–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Corrigan AZ, Bilezikjian LM, Carroll RS, et al. Evidence for an autocrine role of activin B within rat anterior pituitary cultures. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1682–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carroll RS, Corrigan AZ, Vale W, Chin WW. Activin stabilizes follicle-stimulating hormone-β messenger ribonucleic acid levels. Endocrinology. 1991;129:1721–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Attardi B, Miklos J. Rapid stimulatory effect of activin-A on messenger RNA encoding the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit in rat pituitary cell cultures. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:721–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carroll RS, Corrigan AZ, Gharib SD, Vale W, Chin WW. Inhibin, activin, and follistatin: regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone messenger ribonucleic acid levels. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:1969–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hägg E, Tollin C, Bergman B. Isolated FSH deficiency in a male. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1978;12:287–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mozaffarian GA, Higley M, Paulsen CA. Clinical studies in an adult male patient with “isolated follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) deficiency.” J Androl. 1983;4:393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trarbach E, Silveira L, Latronico A. Genetic insights into human isolated gonadotropin deficiency. Pituitary. 2007;10:381–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bernard DJ, Fortin J, Wang Y, Lamba P. Mechanisms of FSH synthesis: what we know, what we don't, and why you should care. Fert Steril. 2010;93:2465–2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lamba P, Fortin J, Tran S. A novel role for the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 in activin A-regulated follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1001–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Corpuz PS, Lindaman LL, Mellon PL, Coss D. FoxL2 Is required for activin induction of the mouse and human follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1037–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tran S, Lamba P, Wang Y, Bernard DJ. SMAD and FOXL2 synergistically regulate murine FSHβ transcription via a conserved proximal promoter element. Mol Endocrinol. 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suszko MI, Balkin DM, Chen Y, Woodruff TK. Smad3 mediates activin-induced transcription of follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1849–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bernard DJ. Both SMAD2 and SMAD3 mediate activin-stimulated expression of the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit in mouse gonadotrope cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:606–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lamba P, Santos MM, Philips DP, Bernard DJ. Acute regulation of murine follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription by activin A. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36:201–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cocquet J, Pailhoux E, Jaubert F, et al. Evolution and expression of FOXL2. J Med Genet. 2002;39:916–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ellsworth BS, Burns AT, Escudero KW, Duval DL, Nelson SE, Clay CM. The gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor activating sequence (GRAS) is a composite regulatory element that interacts with multiple classes of transcription factors including Smads, AP-1 and a forkhead DNA binding protein. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;206:93–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Uda M, Ottolenghi C, Crisponi L. Foxl2 disruption causes mouse ovarian failure by pervasive blockage of follicle development. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1171–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schmidt D, Ovitt CE, Anlag K, et al. The murine winged-helix transcription factor Foxl2 is required for granulosa cell differentiation and ovary maintenance. Development. 2004;131:933–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Crisponi L, Deiana M, Loi A. The putative forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 is mutated in blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;27:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. De Baere E, Beysen D, Oley C, et al. FOXL2 and BPES: mutational hotspots, phenotypic variability, and revision of the genotype-phenotype correlation. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:478–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Udar N, Yellore V, Chalukya M, Yelchits S, Silva-Garcia R, Small K. Comparative analysis of the FOXL2 gene and characterization of mutations in BPES patients. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Justice NJ, Blount AL, Pelosi E, Schlessinger D, Vale W, Bilezikjian LM. Impaired FSHβ expression in the pituitaries of Foxl2 mutant animals. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1404–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ellsworth BS, Egashira N, Haller JL. FOXL2 in the pituitary: molecular, genetic, and developmental analysis. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2796–2805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Uhlenhaut NH, Jakob S, Anlag K, et al. Somatic sex reprogramming of adult ovaries to testes by FOXL2 ablation. Cell. 2009;139:1130–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wen S, Schwarz JR, Niculescu D, Dinu C, Bauer CK, Hirdes W, Boehm U. Functional characterization of genetically labeled gonadotropes. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2701–2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lee KB, Khivansara V, Santos MM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 and activin A synergistically stimulate follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38:315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lamba P, Khivansara V, D'Alessio AC, Santos MM, Bernard DJ. Paired-like homeodomain transcription factors 1 and 2 regulate follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription through a conserved cis-element. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3095–3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ho CC, Zhou X, Mishina Y, Bernard DJ. Mechanisms of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) stimulated inhibitor of DNA binding 3 (Id3) transcription. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;332:242–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lanctot C, Lamolet B, Drouin J. The bicoid-related homeoprotein Ptx1 defines the most anterior domain of the embryo and differentiates posterior from anterior lateral mesoderm. Development. 1997;124:2807–2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boyer A, Lapointe É, Zheng X, et al. WNT4 is required for normal ovarian follicle development and female fertility. FASEB J. 2010;24:3010–3025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Caligioni CS. Assessing reproductive status/stages in mice. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2009;Appendix 4:Appendix 4I [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pisarska MD, Bae J, Klein C, Hsueh AJW. Forkhead L2 is expressed in the ovary and represses the promoter activity of the steroidogenic acute regulatory gene. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3424–3433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hrhansson V, Weddington SC, Petrusz P, Martinritzen E, Nayfeh SN, French FS. FSH stimulation of testicular androgen binding protein (ABP): comparison of ABP response and ovarian augmentation. Endocrinology. 1975;97:469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hagenäs L, Ritzén EM, Plöen L, Hansson V, French FS, Nayfeh SN. Sertoli cell origin of testicular androgen-binding protein (ABP). Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1975;2:339–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Maguire SM, Tribley WA, Griswold MD. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) regulates the expression of FSH receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in cultured Sertoli cells and in hypophysectomized rat testis. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:1106–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Themmen APN, Blok LJ, Post M, et al. Follitropin receptor down-regulation involves a cAMP-dependent post-transcriptional decrease of receptor mRNA expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991;78:R7–R13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Geng Y, et al. Cyclin D2 is an FSH-responsive gene involved in gonadal cell proliferation and oncogenesis. Nature. 1996;384:470–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Richards JS, Ireland JJ, Rao MC, Bernath GA, Midgley AR, Jr, Reichert LE., Jr Ovarian follicular development in the rat: hormone receptor regulation by estradiol, follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology. 1976;99:1562–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hickey G, Chen S, Besman M, et al. Hormonal regulation, tissue distribution, and content of aromatase cytochrome P450 messenger ribonucleic acid and enzyme in rat ovarian follicles and corpora lutea: relationship to estradiol biosynthesis. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1426–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lamba P, Wang Y, Tran S, et al. Activin A regulates porcine follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription via cooperative actions of SMADs and FOXL2. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5456–5467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Roberts V, Meunier H, Vaughan J, Rivier J, et al. Production and regulation of inhibin subunits in pituitary gonadotropes. Endocrinology. 1989;124:552–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lee SL, Sadovsky Y, Swirnoff AH, et al. Luteinizing hormone deficiency and female infertility in mice lacking the transcription factor NGFI-A (Egr-1). Science. 1996;273:1219–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lamolet B, Pulichino AM, Lamonerie T. A pituitary cell-restricted T box factor, Tpit, activates POMC transcription in cooperation with Pitx homeoproteins. Cell. 2001;104:849–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Matzuk MM, Kumar TR, Bradley A. Different phenotypes for mice deficient in either activins or activin receptor type II. Nature. 1995;374:356–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Griswold MD. The central role of Sertoli cells in spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Orth JM, Gunsalus GL, Lamperti AA. Evidence from Sertoli cell-depleted rats indicates that spermatid number in adults depends on numbers of Sertoli cells produced during perinatal development. Endocrinology. 1988;122:787–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Johnston H, Baker PJ, Abel M, et al. Regulation of Sertoli cell number and activity by follicle-stimulating hormone and androgen during postnatal development in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2004;145:318–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wreford NG, Rajendra Kumar T, Matzuk MM, de Kretser DM. Analysis of the testicular phenotype of the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit knockout and the activin type II receptor knockout mice by stereological analysis. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2916–2920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Findlay JK, Drummond AE, Dyson ML, Baillie AJ, Robertson DM, Ethier JF. Recruitment and development of the follicle; the roles of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;191:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Knight P, Glister C. Potential local regulatory functions of inhibins, activins and follistatin in the ovary. Reproduction. 2001;121:503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mizunuma H, Liu X, Andoh K, et al. Activin from secondary follicles causes small preantral follicles to remain dormant at the resting stage. Endocrinology. 1999;140:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Alak BM, Coskun S, Friedman CI, Kennard EA, Kim MH, Seifer DB. Activin A stimulates meiotic maturation of human oocytes and modulates granulosa cell steroidogenesis in vitro. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:1126–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. da Silva SJM, Bayne RAL, Cambray N, Hartley PS, McNeilly AS, Anderson RA. Expression of activin subunits and receptors in the developing human ovary: activin A promotes germ cell survival and proliferation before primordial follicle formation. Dev Biol. 2004;266:334–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ottolenghi C, Omari S, Garcia-Ortiz JE, et al. Foxl2 is required for commitment to ovary differentiation. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2053–2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Blount AL, Schmidt K, Justice NJ, Vale WW, Fischer WH, Bilezikjian LM. FoxL2 and Smad3 coordinately regulate follistatin gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7631–7645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Egashira N, Takekoshi S, Takei M, Teramoto A, Osamura RY. Expression of FOXL2 in human normal pituitaries and pituitary adenomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:765–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. De Baere E, Dixon MJ, Small KW, et al. Spectrum of FOXL2 gene mutations in blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus (BPES) families demonstrates a genotype-phenotype correlation. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1591–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Fan J-Y, Han B, Qiao J, et al. Functional study on a novel missense mutation of the transcription factor FOXL2 causes blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome (BPES). Mutagenesis. 2011;26:283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kuo F-T, Bentsi-Barnes IK, Barlow GM, Pisarska MD. Mutant forkhead L2 (FOXL2) proteins associated with premature ovarian failure (POF) dimerize with wild-type FOXL2, leading to altered regulation of genes associated with granulosa cell differentiation. Endocrinology. 2011;152:3917–3929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Meduri G, Bachelot A, Duflos C, et al. FOXL2 mutations lead to different ovarian phenotypes in BPES patients: case report. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fraser IS, Shearman RP, Smith A, Russell P. An association among blepharophimosis, resistant ovary syndrome, and true premature menopause. Fertil Steril. 1988;50:747–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Raile K, Stobbe H, Trobs RB, Kiess W, Pfaffle R. A new heterozygous mutation of the FOXL2 gene is associated with a large ovarian cyst and ovarian dysfunction in an adolescent girl with blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153:353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Nallathambi J, Moumne L, De Baere E, et al. A novel polyalanine expansion in FOXL2: the first evidence for a recessive form of the blepharophimosis syndrome (BPES) associated with ovarian dysfunction. Hum Genet. 2007;121:107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.