Abstract

The cAMP receptor protein (CRP)/fumarate and nitrate reduction regulatory protein (FNR)-type transcription factors (TFs) are members of a well-characterized global TF family in bacteria and have two conserved domains: the N-terminal ligand-binding domain for small molecules (e.g., cAMP, NO, or O2) and the C-terminal DNA-binding domain. Although the CRP/FNR-type TFs recognize very similar consensus DNA target sequences, they can regulate different sets of genes in response to environmental signals. To clarify the evolution of the CRP/FNR-type TFs throughout the bacterial kingdom, we undertook a comprehensive computational analysis of a large number of annotated CRP/FNR-type TFs and the corresponding bacterial genomes. Based on the amino acid sequence similarities among 1,455 annotated CRP/FNR-type TFs, spectral clustering classified the TFs into 12 representative groups, and stepwise clustering allowed us to propose a possible process of protein evolution. Although each cluster mainly consists of functionally distinct members (e.g., CRP, NTC, FNR-like protein, and FixK), FNR-related TFs are found in several groups and are distributed in a wide range of bacterial phyla in the sequence similarity network. This result suggests that the CRP/FNR-type TFs originated from an ancestral FNR protein, involved in nitrogen fixation. Furthermore, a phylogenetic profiling analysis showed that combinations of TFs and their target genes have fluctuated dynamically during bacterial evolution. A genome-wide analysis of TF-binding sites also suggested that the diversity of the transcriptional regulatory system was derived by the stepwise adaptation of TF-binding sites to the evolution of TFs.

Keywords: molecular evolution, phylogenetics, spectral clustering, transcription factor, cis-element

Introduction

Because bacteria are constantly exposed to various environmental stresses during their evolution, they have developed many types of mechanisms to accommodate or resist these stresses. These include the repression of unnecessary gene expression and the activation of the metabolic gene expression that is required for survival (Perez and Groisman 2009). The cAMP receptor protein (CRP)/fumarate and nitrate reduction regulatory protein (FNR)-type TFs exemplify these processes well. The TFs are intrinsically involved in the system that senses environmental changes, activating selective gene expression to allow the organism to adapt to these changes (Körner et al. 2003). The CRP/FNR-type TF family was first proposed after CRP and FNR were recognized as homologous proteins (Shaw et al. 1983). Currently, there are a variety of family members, with correspondingly numerous functions (Körner et al. 2003). Historically, CRP was the first protein to be identified as being fundamentally involved in the control of catabolite repression, initiating gene expression when glucose levels drop (Stülke and Hillen 1999). When cAMP binds to the N-terminal domain of CNP, the C-terminal DNA-binding (helix-turn-helix [HTH]) domain in the molecule is activated. Recently, it has been reported that CRP is involved in many types of regulation, affecting more than 200 genes (Zheng et al. 2004; Shimada et al. 2011). In contrast, FNR is a representative TF involved in oxygen-regulated gene expression (Spiro and Guest 1990; Green et al. 2001). When oxygen concentrations become limiting, an iron–sulfur cluster (Fe–S-binding motif) at the N-terminus of FNR undergoes a structural change, causing FNR to bind to its target DNA (Lazazzera et al. 1996). FNR also contains a DNA-binding domain in its C-terminal region that shows a high degree of similarity to that of CRP (Spiro et al. 1990). Based on a chromatin immunoprecipitation-on-chip analysis, FNR is reported to transcribe 63 target genes in Escherichia coli (Grainger et al. 2007). Other members of the family include FixK, which regulates nitrogen fixation genes both positively and negatively in soil bacteria (Batut et al. 1989); FNR-like protein (FLP), which is found in Gram-positive bacteria and is also involved in oxygen-regulated gene expression, but binds different sequences than those bound by FNR (Gostick et al. 1998, 1999); and YeiL, which is expressed in E. coli and is proposed to regulate postexponential-phase nitrogen starvation (Anjum et al. 2000).

Structure (amino acid sequence)-based classification is the first research step in clarifying the evolution of the CRP/FNR-type TFs. Fischer (1994) first classified this family of TFs into three groups based on information about their functional domains: 1) a group mainly consisting of FNR and FixK; 2) a CRP group; and 3) a group consisting mainly of CysR/NtcA. Körner et al. (2003) then classified 314 CRP/FNR-type TFs with comprehensive phylogenetic profiling and demonstrated the relationships among several groups. Dufour et al. (2010) focused on three proteins, FNR, FixK, and DNR, in the class α-Proteobacteria and identified coevolutionary features in the TFs and their binding sequences with Markov clustering. All these studies have been very innovative in the functional classification of the TFs, but the evolutionary mechanisms involved remain unclear. This is partly attributable to the difficulty in choosing an outgroup for the phylogenetic analysis of a family of proteins. Clustering based on graph theory is suggested to effectively overcome this problem, and spectral clustering is one potentially useful representative methodology (Paccanaro et al. 2006). Several studies have reported the application of spectral clustering to the analysis of protein families, with great accuracy (Waite et al. 2006; Hooper et al. 2009), mainly because the method reduces the problems caused by clustering multidomain proteins (Pipenbacher et al. 2002).

In contrast, the functional evolution of TFs should be discussed from a coevolutionary perspective to accommodate their target genes. The evolutionary relationships between TFs and their TF-binding sites have been an important and longstanding problem. A number of models have been proposed to resolve this problem: statistical models for TF-binding sites (Berg and von Hippel 1987, 1988), evolutionary models of transcription networks (Madan Babu and Teichmann 2003; Berg et al. 2004), models of transcription regulatory systems that evolve rapidly by point mutations at the TF-binding sites (Stone and Wray 2001; Gerland and Hwa 2002; Gonzalez Perez et al. 2008), and microscopic evolution models (Hershberg and Margalit 2006; Kuo et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2011). Recently, a laboratory-based evolution experiment showed that at least 115 genes began to be expressed in a CRP-dependent manner during the evolution of E. coli for 20,000 generations (Cooper et al. 2008). It was suggested that these genes were acquired either by direct regulation or by an epistatic interaction involving CRP. It is likely that such direct regulation was the result of CRP promoter capture. Promoter capture is thought to be a key innovation in evolution, and the concept has also been supported by another laboratory-based evolution experiment in E. coli, for more than 10,000 generations (Blount et al. 2012). A comparative analysis of the upstream nucleotide sequences of each gene during E. coli evolution showed that promoter capture gave the exact time point representing a novel characteristic (e.g., aerobic citrate utilization), although the corresponding gene had already been acquired before the capture event. These results suggest that the nucleotide sequences of TF-binding sites change in the short term, contributing to the evolution of the transcription network. The computational prediction of TF-binding sites in a wide range of species is another effective approach to analyzing the evolution of transcriptional networks (McCue et al. 2002). For examples, new CRP-binding sites were predicted in the Cyanobacteria (Xu and Su 2009) and in E. coli (Brown and Callan 2004), as well as the noncanonical CRP-binding sites in the γ-Proteobacteria (Cameron and Redfield 2006).

In this article, we clarify the possible origin of the CRP/FNR-type TFs using spectral clustering and phylogenetic approaches. Stepwise clustering, in particular, allows us to identify possible processes in the evolution of a protein family, and a coevolutionary analysis of the TFs and their binding sites suggests that frequent shuffling of pairs of TFs and their target genes occurs through the selection of TF-binding sites. On the basis of these observations, we present a model of the molecular coevolution of a family of TF proteins and their binding sites during the expansion of bacterial species.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

The complete chromosomal and plasmid sequences of 1,969 species (1,845 bacteria and 124 archaea) were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) ftp site (ftp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Ftp) (June 2012). The bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences were downloaded from the Ribosomal Database (release 10, update 29) (Cole et al. 2009). Both the nucleotide and amino acid sequences for 1,455 CRP/FNR-type proteins were downloaded from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Orthology database (Kanehisa et al. 2010) with their KEGG Ortholog IDs (K01420, K10914, K13642, or K15861). The amino acid sequences for 82 well-annotated CRP/FNR-type proteins were also downloaded from the Swiss-Prot database (UniProt Consortium 2012) with their motif IDs (InterPro, IPR001808, IPR012318, or IPR018335; Pfam, PF00325; PRINTS, PR00034; PROSITE, PS00042, or PS51063; SMART: SM00419). The information is summarized in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online.

Spectral Clustering of Protein Sequences and Construction of Networks

Spectral clustering is a method that classifies factors based on the structure of a network graph (in a type of graph-partitioning problem). This method is powerful when an extremely complex network is clustered, such as the CRP/FNR-type family proteins. We first calculated the similarity scores of all the TFs and constructed the network, and then performed spectral clustering.

The similarity scores (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool [BLAST] bit scores) (Altschul et al. 1997) for all the CRP/FNR-type proteins obtained from the KEGG Orthology database were calculated based on a round-robin BLASTP (BLAST 2.2.25+) analysis (Camacho et al. 2009) with a cutoff at E value ≤ 1e–5. This score is defined as S′bits(x, y) and indicates the bit score between the “database” sequence x and the “query” sequence y. The bit scores were normalized according to the following equation (Dufour et al. 2010):

| (1) |

with 0 ≤ Sim(x, y) ≤ 1, where Sim(x, y) represent the normalized sequence similarity between two sequences x and y. Each Sim(x, y) value was then calculated against all pairs of CRP/FNR-type proteins, and a weighted-undirected graph was constructed. Clustering was performed with the spectral clustering algorithm using SCPS 0.9.5 (Nepusz et al. 2010), and the network graph was visualized from the clustering results with Cytoscape 2.8.2 (Smoot et al. 2011).

Bacterial and Archaeal Phylogenetic Trees Based on 16S rRNA Gene Sequences

We classified 1,969 bacterial and archaeal species into 36 phyla (31 Bacteria and 5 Archaea) according to the NCBI Taxonomy database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy, last accessed January 25, 2013). We then manually selected one representative species from each phylum (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). A multiple alignment of the 16S rRNA sequences of these species was created with Muscle 3.7 (Edgar 2004), and a phylogenetic tree was constructed with the maximum likelihood method using PHYLIP 3.5 (Felsenstein 1989, 1993) (LG model with 1,000 bootstrap replicates).

Multiple Sequence Alignment of the CRP/FNR Family Proteins

We selected 41 unique proteins from the 82 CRP/FNR-type proteins in the Swiss-Prot database by removing the homologous proteins of related species. The amino acid sequences were aligned with Muscle 3.7 (Edgar 2004), and a phylogenetic analysis was performed using PHYLIP 3.5 (Felsenstein 1989, 1993) based on the LG substitution model, supported by bootstrap resampling with 1,000 replications. Seaview 4.3.3 (Gouy et al. 2010) was used to visualize the multiple sequence alignment and the phylogenetic tree. Information about the protein secondary structures was obtained from their motif IDs in the Swiss-Prot database and was represented using the R software (R Development Core Team 2012). Spectral clustering of the 82 CRP/FNR-type proteins was conducted as described earlier.

Evolutionary Conservation Analysis

The list of phosphotransferase system (PTS)-related proteins in both E. coli and B. subtilis was obtained from GenBank (NCBI). The proteins with the highest amino acid sequence similarities to these PTS-related proteins and the representative CRP/FNR-type TFs were extracted from either the chromosomal or plasmid sequences of 1,969 bacterial and archaeal species with a TBLASTN analysis (Camacho et al. 2009), with a cutoff at E value ≤ 1e–5. The similarity distance score between each retrieved sequence was measured based on Sim(x,y) (eq. 1) using the bit scores calculated with the TBLASTN analysis.

Coevolutionary Analysis

Coevolutionary analysis is a group of methods used to identify the evolutionary relationships among multiple factors. Phylogenetic profiling is one of these methods and indicates the intensities of the evolutionary relationships by calculating coconservations based on comparative genomics.

To quantify the pairwise evolutionary distances among the PTS-related proteins and the representative CRP/FNR-type TFs, a phylogenetic profiling analysis was performed. In this study, a linear regression was applied as a measure of phylogenetic profile using similarity distance scores with a cutoff at 0.2 ≤ Sim(x,y). The linear correlation coefficient r (Pearson’s correlation coefficient [Goh et al. 2000]) between sequences x and y was defined as:

|

(2) |

with −1 ≤ r ≤ 1, where xi and yi are the similarity distance scores of x and y, respectively, in species i.  and

and  are the means of all xi and all yi, respectively. If the r value is closer to 1, the pair is estimated to be evolutionarily interactive. If the r value is closer to −1, the pair is estimated to be evolutionarily unrelated.

are the means of all xi and all yi, respectively. If the r value is closer to 1, the pair is estimated to be evolutionarily interactive. If the r value is closer to −1, the pair is estimated to be evolutionarily unrelated.

For the coevolutionary analysis of a transcription factor (TF) and its target genes, a list of target genes for the CRP/FNR-type TFs in E. coli and B. subtilis was obtained from the RegulonDB (Gama-Castro et al. 2011) and DBTBS (Sierro et al. 2008), respectively. The pairwise evolutionary distances among the CRP/FNR-type TFs and their target genes were calculated using the linear correlation coefficient r, in the manner described earlier.

For the coevolutionary analysis of a TF and its target nucleotide sequence (TF-binding site [TFBS]), possible TFBSs were predicted using a position weight matrix (PWM) model (Tan et al. 2001) for all genes from the 1,969 species examined. Initially, 300 bases in the 5′-upstream region from the start codon of each gene were obtained from the NCBI database. The PWMs described by Tan et al. (2001) were used for both the CRP and FNR models, and the PWM for the CcpA model was obtained from the DBTBS. The list of target genes of CRP and FNR in E. coli was obtained from the RegulonDB, and the list of target genes of CcpA in B. subtilis was obtained from the DBTBS. Proteins with the highest amino acid sequence similarities to these target-gene-encoded proteins were extracted from either the chromosomal or plasmid sequences of the 1,969 species with a BLASTP analysis (Camacho et al. 2009), with a cutoff at E value ≤ 1e – 5. The similarity distance score between each retrieved sequence was measured based on equation 1, using the bit scores calculated with the BLASTP analysis. Orthologous genes are defined as those genes showing a similarity distance score with a cutoff at 0.4 ≤ Sim(x,y).

Results

Spectral Clustering of the CRP/FNR-Type Transcription Regulators Reveals Their Stepwise Evolution in Bacteria

The CRP/FNR-type TF family is one of the very large, highly diverse protein families, and it is difficult to apply commonly used strategies to classify the members. Therefore, we used a spectral clustering methodology and analyzed the relationships among the clusters thus defined to reveal the molecular evolution of the family.

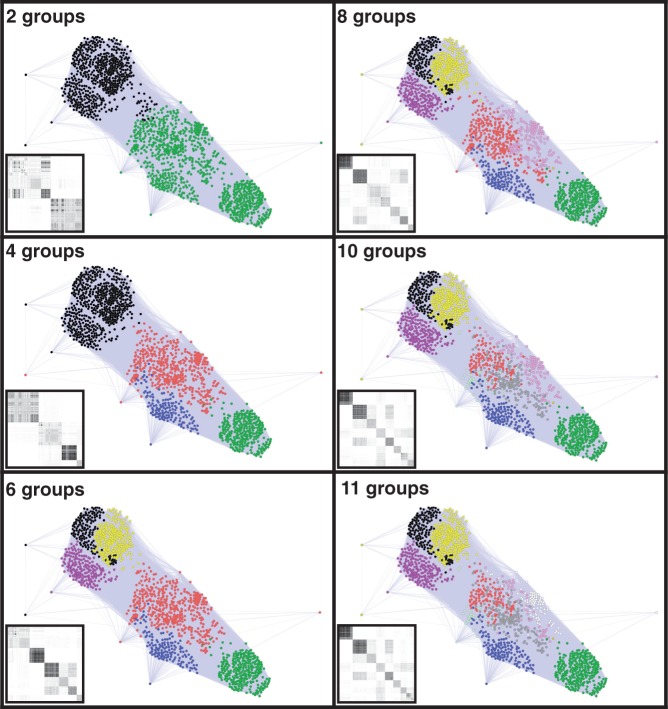

To clarify the evolution of the CRP/FNR-type TFs throughout the bacterial kingdom, we used a well-organized database, the KEGG Orthology database, and obtained 1,455 amino acid sequences for CRP/FNR-type TFs with reliable annotated information (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). Because these 1,455 sequences include various types of family members, a spectral clustering technique was used to classify them into functional subgroups based on sequence similarities (BLAST bit scores) (Nepusz et al. 2010), and the sequence similarity networks were visualized. Figure 1 shows the results of this stepwise clustering (examples of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, or 11 groups). In the first two-group stage, a group primarily consisting of FNR is distinguished (shown in black). A group mainly consisting of CRP is then distinguished (green) at the four-group stage. The group mainly consisting of FNR is then segmented (black, yellow, and magenta) at the six-group stage. From the 8-group stage to the final 12-group stage (fig. 2), both CRP and FNR are further segmented (pink, white, and gray). We constructed a phylogenetic tree that represents the order of the group segmentation (supplementary fig. S1A, Supplementary Material online) and found that the tree corresponds well to the functional divergence of the protein family and/or the species distributions (fig. 3 and table 1). These results suggest that stepwise clustering could clarify the processes of protein evolution.

Fig. 1.—

Stepwise analysis of the sequence similarity networks of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators. A total of 1,455 CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators obtained from the KEGG Orthology database were clustered into 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, or 11 groups based on the spectral clustering method. The circular symbol represents each transcription regulator, and the colors indicate regulators from the same group. The edge lengths represent the sequence similarities. The heatmap box on the lower left shows the rearranged similarity matrix of the network. Darker dots correspond to greater similarities.

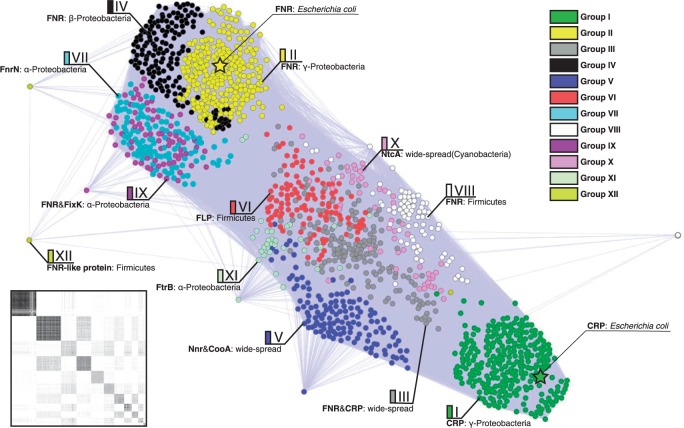

Fig. 2.—

Sequence similarity network of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators (12 groups). A total of 1,455 CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators obtained from the KEGG Orthology database were clustered into 12 groups (I–XII) based on the spectral clustering method. Symbols (circle or star) represent each transcription regulator, and the colors indicate regulators from the same group. The edge lengths represent the sequence similarities. The annotated gene names with the corresponding species are shown below each group name. The heatmap box on the lower left shows the rearranged similarity matrix of the network. Darker dots correspond to greater similarities.

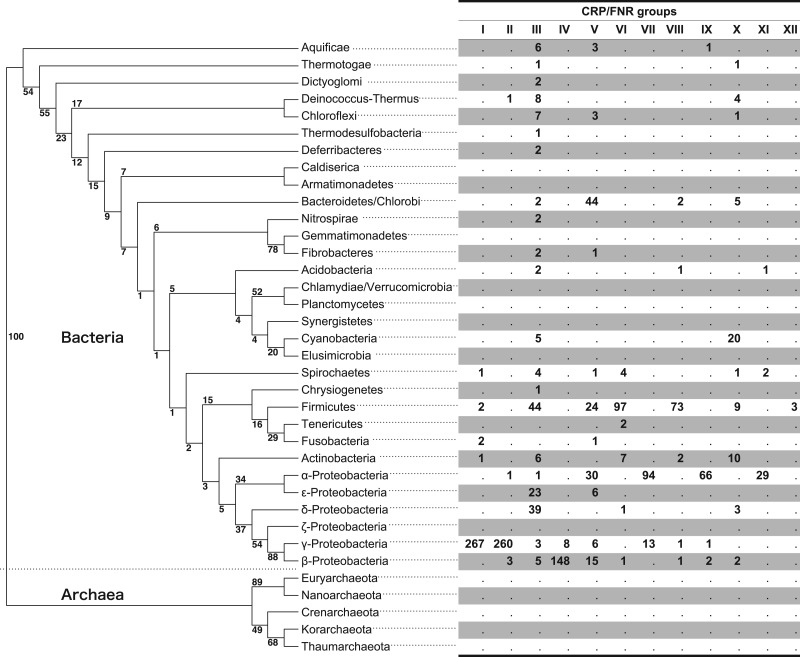

Fig. 3.—

Phylogenic distribution of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulator groups in bacteria. The numbers in each CRP/FNR group clustered by the sequence similarity network analysis (fig. 2) are mapped onto a 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree of 36 representative phyla (31 Bacteria and five Archaea). Bootstrap values are shown near the nodes (based on 1,000 replications). The CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators (1,455 in total) were obtained from the KEGG Orthology database (table 1). A single dot represents zero.

Table 1.

CRP/FNR-Type Transcription Regulator Groups and Their Numbers of Annotated Genes

| Groups | KEGG Orthology |

Annotated Proteins | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K01420 | K10914 | K13642 | K15861 | ||

| I | 273 | CRP:116, Vfr:10, CLP:8 | |||

| II | 265 | FNR:106, ANR:17, HlyK:6, EtrA:2, CRP:1, CydR:1 | |||

| III | 158 | 8 | CRP:5, FNR:3, NssR:1, Vfr:1, DNR:1, YieJ:1 | ||

| IV | 156 | FNR:18, BTR:7, FnrL:4 | |||

| V | 135 | Nnr:2, CRP:2, CrpA:2, FNR:1, CooA:1 | |||

| VI | 112 | FLP:11, FNR:2, RcfA:1, CRP:1 | |||

| VII | 107 | FixK:7, FnrN:7, AadR:4, FNR:4, FnrA:4, FnrL:4, CRP:2, ANR:1 | |||

| VIII | 79 | 1 | FNR:16 | ||

| IX | 22 | 48 | FixK:32, CRP:2 | ||

| X | 56 | NtcA:16, FNR:1, GlxR:1 | |||

| XI | 3 | 29 | FtrB:21 | ||

| XII | 3 | FNR-like:3 | |||

Note.—The number in each group is listed according to the four KEGG Orthology IDs (K01420, K10914, K13642, and K15861). See also supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online.

In the final 12-group stage, group VII, mainly consisting of FnrN, and group IX, mainly consisting of FixK, are differentiated (supplementary figs. S1 and S2, Supplementary Material online), although their boundaries are still tangled. It has been reported that the amino acid sequences of these two proteins are quite similar, although only FnrN has the four conserved cysteine residues that are required for Fe–S binding (Moore et al. 2006). Based on these results, the 12-group stage was used for the functional subgroups in this article. In these 12 groups, three of the four KEGG Ortholog IDs correspond well to three individual groups: K10914 (group I), K13642 (group XI), and K15861 (group IX). Conversely, ID K01420 corresponds to many groups (table 1). Some proteins are classified well into specific groups according to the protein annotations: CRP (group I), FLP (group VI), FixK (group IX), NtcA (group X), and FtrB (group XI). In contrast, FNR straddles several groups (groups II/IV/VII/VIII/IX). Furthermore, the protein network structure shows that two large clusters are located at the edges of the network: one cluster consisting of group I (mainly CRP proteins) and the other consisting of groups II/IV/VII/IX (mainly FNR proteins). Between these two clusters is another cluster consisting of groups III/V/VIII/VI/X/XI/XII, with several annotated genes (fig. 2).

To analyze the evolutionary positions of the 12 clustered groups (I–XII), a phylogenetic tree of 31 bacterial and five archaeal phyla was constructed using a multiple alignment of the 16S rRNA sequences of representative species from each phylum (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online), and the 12 groups were mapped onto the tree. As shown in figure 3, no archaeal proteins are related to the CRP/FNR-type TFs. Groups I and II/IV/VII/IX, which are located at opposite ends of the network, correspond to the Proteobacteria phylum, whereas the groups located in the central region of the network correspond to multiple phyla, including Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Cyanobacteria. Groups III, V, and X show especially wide ranges of bacterial species from Aquifex to Proteobacteria.

Characterization of the Structural Domains in the CRP/FNR-Type Transcription Regulators

To determine the relationships between the clustered CRP/FNR-type TF groups and their functional features, focusing particularly on their structural domains, a further analysis was conducted using the amino acid sequence data for 82 of these TFs in the Swiss-Prot database, although the number of CRP/FNR-type TFs registered in the database is limited (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). Initially, the same spectral clustering analysis was performed. In this analysis, both CRP and FNR were clearly separated as individual groups at the seven-group stage (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online): group A contained mainly FNR proteins and group C mainly contained CRP proteins. Groups B and D corresponded to the CRP/FNR-type TFs from either Firmicutes or Cyanobacteria, respectively. In contrast, groups E, F, and G showed “independent” characteristics, with no connections to other groups. It is noteworthy that group F contained two YeiL proteins, which are reported to have only 20% amino acid similarities to known CRP/FNR-type TFs, such as FNR, FLP, and FixK (Gostick et al. 1999; Anjum et al. 2000). However, groups E and G contained different types of proteins, with only a secondary structural motif similar to the HTH motif in the CRP/FNR-type TFs (Projan et al. 1987; Mashhadi et al. 2008). We also confirmed that the main clustered groups from the two databases, Swiss-Prot and KEGG Orthology, overlap (see supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online; discussed later).

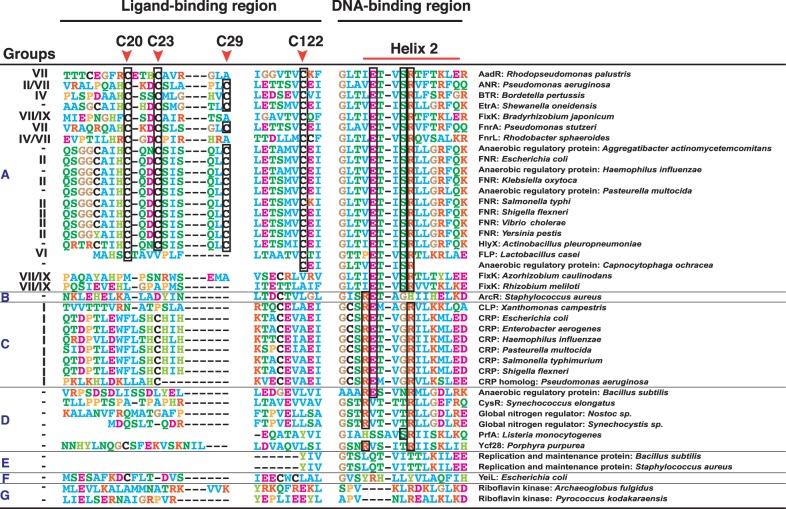

Based on this analysis, of the 82 proteins taken from the Swiss-Prot database, 41 unique proteins with appropriate functional annotations were further selected manually as reference sequences. A phylogenetic analysis of the 41 proteins supported the clustering results (supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online). A multiple alignment analysis of the amino acid sequences of the 41 proteins was then performed, focusing on the ligand-binding and DNA-binding domains (fig. 4). Most of the group A proteins contained the four conserved cysteine residues of the Fe–S-binding motif in the ligand-binding domain and another seven group A proteins lacking the motif included proteins such as FixK. It has been reported that FixK, an FNR homolog, lacks the Fe–S-binding motif and does not bind the Fe(II) ion (Batut et al. 1989). However, all the proteins in group A contain the ExSR motif (FNR-type DNA-binding motif), and all the proteins in group C contain an RExxR motif (CRP-type DNA-binding motif) in each of their DNA-binding domains (Tan et al. 2001). The proteins of groups B and D also contain the RExxxH motif and the RxxxxR motif, respectively, and both these motifs are considered to be CRP-like DNA-binding motifs (Vega-Palas et al. 1992; Maghnouj et al. 2000). In contrast, the proteins in groups E, F, and G share neither the CRP-type nor the FNR-type DNA-binding motifs. The domains in the same 41 proteins were also characterized according to information about their secondary structures (supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online). As the ligand-binding domain, the N-terminal region of nine proteins in group A were annotated as containing the Fe–S-binding motif, and all the proteins in group C contained the cyclic nucleotide monophosphate (cNMP)-binding motif in their N-terminal regions. Interestingly, the Fe–S-binding motif was also observed in both groups F and G. Some proteins in groups A, B, and D also contained the cNMP-binding motif. All the proteins, except those in groups E and G, contained the HTH motif in the C-terminal region, the DNA-binding region. Some discrepancies between the analyses based on the amino acid sequences and the secondary structures are discussed later.

Fig. 4.—

Amino acid sequence alignment of the ligand-binding and DNA-binding domains of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators. Amino acid residues of two conserved regions (ligand-binding and DNA-binding domains) are compared among 41 unique CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators from the Swiss-Prot database. These sequences are clustered into seven groups (A–G) based on the spectral clustering method (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). The corresponding groups based on spectral clustering using the KEGG Orthology database are also indicated. Amino acid residues are colored according to their physicochemical properties, and functionally important amino acid residues are boxed. Protein and species names are shown on the right. Each group corresponds to a specific functional group (see supplementary figs. S4 and S5, Supplementary Material online). For example, the ligand-binding domain in group A is characterized by the amino acid residues required for Fe–S binding (red arrows; C20, C23, C29, and C122). The amino acid sequences from the second helix region of the helix–turn–helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain are also shown.

Coevolution of the CRP/FNR-Type Transcription Regulators and Their Target Genes

To determine the relationships among the TFs and their target genes during bacterial evolution, both an evolutionary conservation analysis and a phylogenetic profiling analysis were conducted. The results showed that combinations of TFs and their target genes have fluctuated dynamically during evolution.

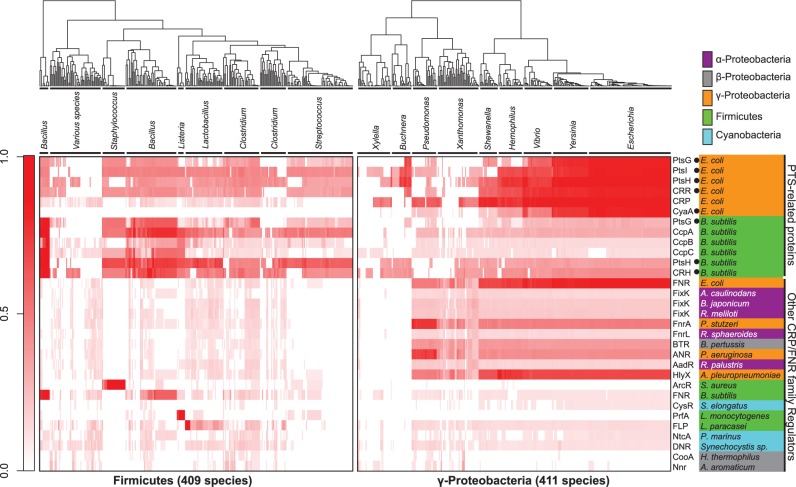

First, an evolutionary conservation analysis of the CRP/FNR-type TFs and their target genes in bacteria was performed. In this analysis, we focused on two major TFs, CRP from E. coli (class γ-Proteobacteria) and CcpA from Bacillus subtilis (phylum Firmicutes), as well as other CRP/FNR-type TFs from several bacteria. The PTS-related genes were selected as the target genes. For example, it has been reported that CRP is involved in carbon catabolite repression (CCR) through the PTS proteins, such as PtsI, PtsH, Crr, and CyaA in E. coli (Ishizuka et al. 1994); CcpA is also involved in CCR through the B. subtilis PTS genes, including PtsG, PtsH, and Crh (Warner and Lolkema 2003). Figure 5 shows that CRP and the target proteins that are homologous to the E. coli PTS proteins are highly coconserved in Escherichia, Yersinia, and Vibrio genera in the class γ-Proteobacteria. It is especially noteworthy that within the genus Escherichia, the level of coconservation per protein is quite uniform (supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). However, lower levels of coconservation of the PTS-related proteins in the genera Pseudomonas, Xanthomonas, Shewanella, and Haemophilus were observed, although the CRP/FNR-type TFs, such as CRP, FNR, and HlyX, represent higher levels of coconservation. Markedly lower coconservation of the CRP/FNR-type TFs was observed in the genera Buchnera and Xylella. However, CcpA and proteins homologous to the B. subtilis PTS proteins are also highly coconserved in the genera Bacillus and Staphylococcus of the phylum Firmicutes. No other CRP/FNR-type TF is highly conserved throughout the phylum, although ArcR, FNR, PrfA, and FLP are conserved genus specifically in the phylum Firmicutes (fig. 5). Within the Bacillus genus, subspecies-specific coconservation was also observed. For example, FNR and FLP are conserved in a mutually exclusive manner (supplementary fig. S7, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 5.—

Amino acid conservation analysis of the PTS-related proteins and the other CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators in bacteria. Degrees of amino acid conservation of the PTS-related proteins and the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators among either the Firmicutes or γ-Proteobacteria are shown as heatmaps. The PTS-related proteins contain both the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators and their target gene products (black dots). Darker red corresponds to a greater similarity score. The phylogenetic dendrogram was generated with the neighbor-joining method.

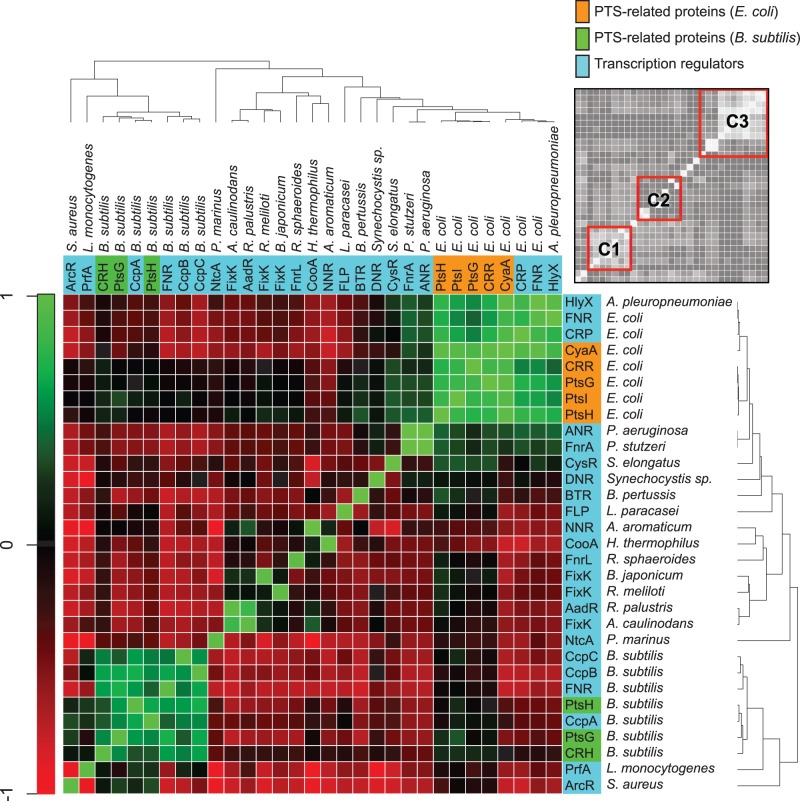

Next, a phylogenetic profiling analysis of all members of the CRP/FNR-type TFs was performed. The results showed two strong clusters (C1 and C3) and one weak cluster (C2) in the coevolutionary matrix plot (fig. 6). The C1 cluster contained the PTS-related proteins as well as CcpA and FNR from B. subtilis, and the C3 cluster contained the PTS-related proteins as well as CRP and FNR from E. coli. The C3 cluster also contains HlyX from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, ANR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, FnrA from P. stutzeri, and CysR from Synechococcus elongatus. All these proteins showed strong coevolutionary profiles. In contrast, the C2 cluster contained Nnr, CooA, FnrL, FixK, and AadR from various bacteria. It is noteworthy that no coevolutionary profile was identified between FNR from E. coli and FNR from B. subtilis, although they are orthologous proteins. Similarly, no coevolutionary profile was identified between FNR and FixK, although the amino acid sequences of these two proteins are quite similar. These results are consistent with the results of the spectral clustering analysis (figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 6.—

Coevolutionary matrix plot of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators and the PTS-related proteins in bacteria. Degrees of phylogenetic co-occurrence of the PTS-related proteins and the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators among bacteria are shown as a heatmap using red–green colors. The degrees correspond to Pearson correlation coefficients based on a phylogenetic profiling method. The phylogenetic dendrogram was generated with the neighbor-joining method. The gray-scale heatmap on the upper right indicates the three characteristic clusters (C1, C2, and C3).

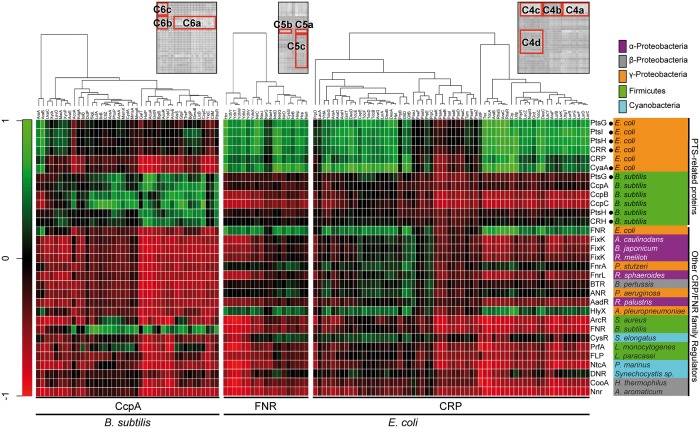

A phylogenetic profiling analysis of the TFs (CPR, FNR, and CcpA) and their target gene products was conducted based on the deduced amino acid sequences from 1,969 prokaryotic genomes. For this analysis, sets of target gene products were initially created per genome based on information about the E. coli CPR targets, E. coli FNR targets, and B. subtilis CcpA targets, and the degrees of phylogenetic co-occurrence were calculated (see Materials and Methods). The results confirmed the known relationships between each of the three TFs and their targets, with strong degrees of phylogenetic co-occurrence (clusters C4a, C4b, C5a, C5b, and C6a in fig. 7). The results also showed that some target gene products are not phylogenetically conserved with their TFs; CRP and the gene products from neither the paa operon nor the prp operon (C4b); FNR and neither NarG nor NarH; and CcpA and the gene products from neither the ara operon nor XylA (C6b). In contrast, the enzymes related to sugar metabolism, such as the gene products from the ara operon and XylA, showed weak degrees of phylogenetic co-occurrence with CRP (cluster C6c), although the gene products from the paa operon were not phylogenetically conserved with any other CRP/FNR-type TF, except CRP. According to the observation of clusters C6b and C6c, the relationships between TFs and their target gene product are exchanged rarely in the two species E. coli and B. subtilis. It is also true that some of the CRP target gene products are evolutionally regulated either only by CRP (cluster C4a) or also by other TFs, such as FixK, Btr, Anr, CysR, and DNR (clusters C4c and C4d). Similarly, some of the FNR target gene products are evolutionally regulated either only by FNR (cluster C5b) or also by other TFs (clusters C5a and C5c).

Fig. 7.—

Coevolutionary matrix plot of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators and their target gene products in bacteria. Degrees of phylogenetic co-occurrence of either the PTS-related proteins or CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators and their target gene products among bacteria are shown as heatmaps. Three sets of target gene products were determined based on information for the CRP target gene products in Escherichia coli, the FNR target gene products in E. coli, and the CcpA target gene products in Bacillus subtilis. The PTS-related proteins contain both CRP/FNR-type transcription regulators and their target gene products (black dots). Each gray-scale heatmap on the upper right of the panel indicates the characteristic clusters (C4a–d, C5a–c, or C6a–c).

Evolution of the TF-Binding Sites Targeted by the CRP/FNR-Type Transcription Regulators

TFs regulate their target genes by binding to TF-binding nucleotide sequences located in the promoter regions of these genes. We investigated the evolutionary processes underlying the relationship between each TF and its target gene by analyzing the TF-binding sequences at a genome-wide level.

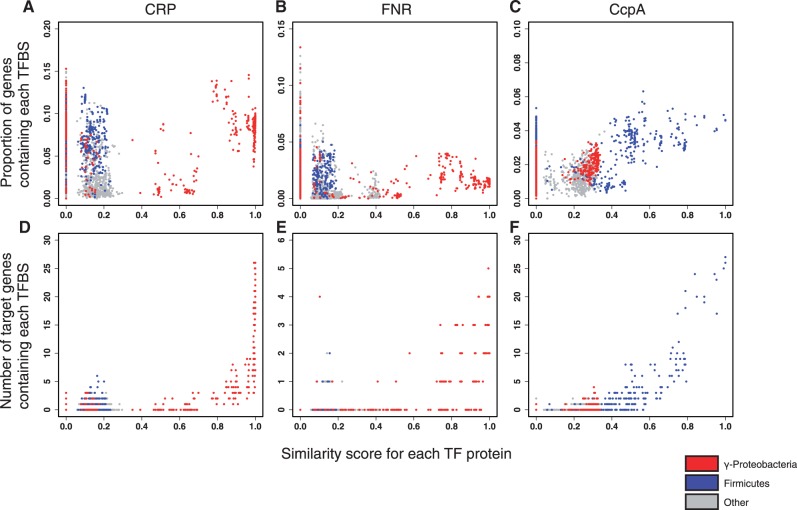

A correlation analysis of the TFs (CRP, FNR, and CcpA) and their binding sites was conducted. Initially, each TF-binding site was predicted in 1,969 prokaryotic genomes based on the consensus sequence. The proportions of genes containing the consensus sequence recognized by each TFs and the degree of amino acid conservation for each TF was compared (fig. 8A–C). The binding sites for CRP and FNR were roughly divided into three categories, depending on the degree of amino acid similarity with the TFs. In the species with low amino acid conservation of the TF (Sim(x,y) = 0.0–0.3), the proportion of genes containing the consensus sequence was distributed relatively widely (0–15%). In the species with medium amino acid conservation of the TF (Sim(x,y) =0.3–0.7), the proportion of genes containing the consensus sequence was distributed a little less widely (0–10%). Finally, in the species with high amino acid conservation of the TF (Sim(x,y) = 0.7–1.0), the proportion of genes containing the consensus sequence was again high (4%–15%). The same data were also analyzed for the following three taxa (fig. 8): γ-Proteobacteria (shown in red), Firmicutes (blue), and other (gray). The results can be clearly divided into two categories: 1) Firmicutes phylum and other bacteria (Sim(x,y) ≤ 0.3) and 2) γ-Proteobacteria class (Sim(x,y) ≥ 0.3). In the range Sim(x,y) ≤ 0.3, the proportion of genes containing the CRP consensus sequence is relatively higher in the Firmicutes phylum, but the proportion of genes containing the FNR consensus sequence is the same in all three phyla. For CcpA, which is not one of the CRP/FNR-type TFs, the proportion of genes containing the CcpA-binding site correlates weakly with the degree of amino acid conservation in CcpA. In this case, a phylum-specific distribution of the genes containing the CcpA-binding site was also observed: the phylum Firmicutes (Sim(x,y) ≥ 0.3) and the class γ-Proteobacteria (Sim(x,y) = 0.2–0.35). However, the weak correlation was not dependent on the kind of phylum. The same analysis was performed on extracted known target genes and their homologs (fig. 8D–F). The number of genes containing the TF-binding site increased for all TFs (CRP, FNR, and CcpA) in the range Sim(x,y) = 0.7–1.0. However, the overall patterns of these distributions were similar in the two sets of data (shown in fig. 8A–F).

Fig. 8.—

Analysis of genes containing each TFBS. The upper three panels indicate the proportions of genes containing each TFBS. The proportion per species is mapped with the amino acid similarity scores for Escherichia coli CRP (A), E. coli FNR (B), or Bacillus subtilis CcpA (C). The lower three panels indicate the numbers of target genes containing each TFBS. The number per species is mapped with the amino acid similarity scores for E. coli CRP (D), E. coli FNR (E), or B. subtilis CcpA (F). Each dot represents one bacterial strain belonging to the γ-Proteobacteria (red), Firmicutes (blue), or other phyla (gray).

Discussion

In this study, a spectral clustering analysis of 1,455 annotated CRP/FNR-type TFs was performed and classified the TFs into 12 representative groups (fig. 2). Stepwise clustering allows us to clarify the possible processes of protein evolution and our results suggest that the origin of the CRP/FNR-type TFs was an ancestral FNR protein. The 12 groups actually correspond to functionally different proteins and are not influenced by any factor that might create inappropriate bias in the KEGG Orthology database. There are obvious relationships between 4 of the 12 groups (groups I–XII) from the KEGG Orthology database and four of the seven groups (A–G) from the Swiss-Prot database: I-to-C (mainly consisting of CRP), II-to-A (mainly consisting of FNR), VI-to-B (CRP/FNR-type TFs from the phylum Firmicutes), and X-to-D (CRP/FNR-type TFs from the phylum Cyanobacteria) (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online). Furthermore, some proteins also overlap between groups III and F. Group F consists of two YeiL proteins, which are known to be distinct CRP/FNR-type TFs with only 20% amino acid sequence similar to other CRP/FNR-type TFs, such as CRP, FNR, FLP, and FixK (Gostick et al. 1999; Anjum et al. 2000). These results indicate that the main distributions of the CRP/FNR-type TFs in the two networks are quite similar between the two clustering groups. In summary, our clustering approach provides well-fractionated representative CRP/FNR-type TFs, including CRP, FNR FixK, CysR, and FLP. Moreover, the sequence similarity network calculated in this study (fig. 2) is consistent with those of previous studies (Fischer 1994; Körner et al. 2003; Dufour et al. 2010). Therefore, our method of spectral clustering combined with a phylogenetic analysis is very effective, especially for families of proteins for which it is difficult to define an outgroup. In contrast, groups E and G did not contain the corresponding orthologous proteins from the KEGG Orthology database. Group G was composed of two archaeon-specific riboflavin kinases (Mashhadi et al. 2008), and group E was composed of proteins similar to a firmicute plasmid replication protein, RepL (Projan et al. 1987). According to the Uniprot database (http://www.uniprot.org/, last accessed January 25, 2013), all four proteins from group E contain the CRP-type HTH motif in the middle of the protein, suggesting that the HTH motif is used to bind to the plasmid replication origin. Similarly, each of the two proteins from group G has an HTH motif in its N-terminal half and an Fe–S-binding-like motif in the C-terminal half, suggesting that these motifs are related to the Zn(II)- and CTP-dependent activities of the archaeon-specific riboflavin kinases, although the location of each motif is inverted relative to those of the usual CRP or FNR proteins. Because these group E/G proteins are not the members of the CRP/FNR-type TF family, they can be treated as “negative controls” for the clustering of the CRP/FNR-type TFs from the KEGG Orthology database.

There is a discrepancy in the annotation of the Fe–S motif between the primary amino acid analysis (fig. 4) and the secondary structural analysis (supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online). Specifically, five proteins (ANR, BTR, EtrA, FnrA, and HlyX) are shown to contain the four conserved cysteine residues that act as an Fe–S-binding motif, similar to another nine proteins in figure 4. However, these five proteins are not annotated as proteins with Fe–S motifs in supplementary figure S5, Supplementary Material online. We observed that the nine annotated proteins showed complete conservation of both the four cysteine residues and the neighboring amino acid residues in the motif. However, in ANR, BTR, EtrA, FnrA, and HlyX, several amino acid replacements have occurred in the sequences neighboring each conserved cysteine residue. Two interpretations can be made. 1) There might be an annotation bias in the Swiss-Prot database, such that the Fe–S motif was annotated using the orthologous FNR-type TFs as the first data set. 2) Alternatively, the neighboring sequences of each conserved cysteine residue are actually important for the ligand-binding activity of each protein. The latter explanation is supported by the observation that the regular positioning of the four cysteine residues is important in binding Fe(II) ions (Lazazzera et al. 1996).

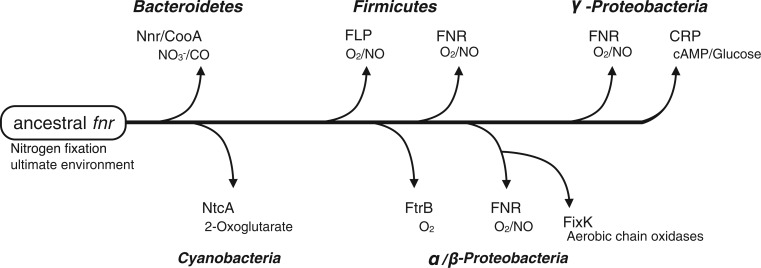

In this article, we have suggested that the “core protein” of the sequence similarity network graph, which indicates the origin of the CRP/FNR-type TFs, is the FNR-type TF, because FNR orthologs are located in the center of the network graph (fig. 2) and are widely distributed on the 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree (fig. 3). On the phylogenetic tree of representative CRP/FNR-type TFs (supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online), the evolutionary distances among the members of group A (FNR family proteins) are longer, and the members are more diverse than those of group C (CRP family proteins). Because the core protein has persisted for more evolutionary time, longer evolutionary distances are usually observed between its orthologous proteins. Similarly, proteins that are derived from the core protein are located at distances that reflect the time since their divergence. Therefore, we conclude that the phylogenetic analysis also supports the concept that the core protein is the FNR-type TF. The facts that nitrogen-fixing bacteria are ancient organisms (Fani et al. 2000; Raymond et al. 2004; Muraki et al. 2010) and FNR is involved in nitrogen fixation supports this concept. Furthermore, TFs such as CRP, NtcA, FixK, Nnr, and CooA, each with a specific function, are distributed throughout the surrounding areas of the network (fig. 2), and these proteins are clustered in a phylum-specific manner (fig. 3). Therefore, it is reasonable that these CRP/FNR-type TFs evolved from the ancestral FNR in a phylum-specific way. Based on these observations and the phylogenetic position of each organism, a model of the evolution of the CRP/FNR-type TFs is proposed (fig. 9).

Fig. 9.—

Model of the evolution of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulator genes. The tentative common ancestor of the CRP/FNR-type transcription regulator is defined as “ancestral FNR.” The arrows indicate a possible evolutionary scenario for the protein family. Representative protein names are shown with their phyla and ligands.

A coevolutionary analysis of the CRP/FNR-type TFs revealed a rather complex relationship among this family of proteins (fig. 6). For example, evolutionary conservation is observed between two different functional TFs, such as between CRP and Hly, between CRP and ANR, and between FixK and AadR. Evolutionary conservation is also evident between the PTS-related proteins and each newly reported member of the TFs (CysR, FnrA, ANR, and HlyX). Furthermore, the same complexity of relationships is observed between the TFs and their target genes (proteins) in figure 7. All these results suggest that the partnerships between TFs or between TFs and their target genes are not fixed as a single specific combination but represent a variety of combinations. Furthermore, the coevolutionary analysis of the PTS-related proteins and the TFs that regulate their expression showed that some of these pairs are rearranged in a species-specific manner (figs. 5 and supplementary figs. S6 and S7, Supplementary Material online). These results suggest that the partnerships between TFs and their target genes vary, even within the same phylum. According to a mathematical model analysis (Berg et al. 2004) and laboratory-based evolutionary experiments (Blount et al. 2012), genetic variability in promoter sequences plays an important role in the rapid evolution of transcriptional networks. Therefore, promoter sequence (TF-binding site) variations could contribute to the rearrangement of pairs of TFs and their target genes at the species level. In this context, figure 8A (CRP) and B (FNR) shows that the proportions of genes with a TF-binding site can be divided roughly into three categories, depending on the degree of amino acid similarities within the TFs. Here, the consensus sequences of the TF-binding sites extracted in the low-amino-acid-conservation group may have emerged coincidentally after neutral fluctuations in the nucleotide sequences, and many of these consensus sequences suggest the existence of a neutral variation step during the molecular evolution of the sequences, even before the emergence of specific TFs (such as α). These results suggest that the promoter sequence (TF-binding site) itself evolved according to the evolution of the TFs, in the following three steps: 1) neutral variations; 2) reduction in the numbers of TF-binding sites under selective pressure; and 3) increase in the numbers of TF-binding sites undergoing adaptation. In contrast, this type of evolutionary process is not applicable to CcpA (fig. 8C), probably because CcpA is not a member of a family of proteins in a single organism, whereas CRP and FNR coexist in one organism. When a new TF with the same DNA-binding specificity is generated by gene duplication, new pairs of TFs and their target genes also arise, causing harmful “cross lines” through the DNA-binding sites that were previously neutral features. In this case, strong selection pressures may remove unfavorable DNA-binding sites. Thus, we have presented a speculative model of the coevolution of the TFs and their target sequences (supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online). In this model, it is important to include an “idling step” in the evolution of the promoter (especially step 3 of supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online). This step may contribute to the generation of the variety of transcriptional networks and TF family proteins. To date, several coevolutionary models of TFs and their target sequences have been proposed to explain some specific situations (Berg et al. 2004; Hershberg and Margalit 2006; Kuo et al. 2010). However, we believe that our model (both figs. 9 and supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online) explains the more general evolutionary processes, including the origins of protein families and the shuffling of pairs of TFs and their target genes via the selection of TF-binding sites. This model also contributes to the effective compartmentalization of many family proteins.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables S1 and S2 and figures S1–S8 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the members of the RNA group at the Institute for Advanced Biosciences, Keio University, Japan, for their insightful discussions. This work was supported in part by research funds from the Yamagata Prefectural Government and Tsuruoka City, Japan, and a research fund from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to M.M.

Literature Cited

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum MF, Green J, Guest JR. YeiL, the third member of the CRP-FNR family in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2000;146(Pt 12):3157–3170. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-12-3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batut J, et al. fixK, a gene homologous with fnr and crp from Escherichia coli, regulates nitrogen fixation genes both positively and negatively in Rhizobium meliloti. EMBO J. 1989;8:1279–1286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J, Willmann S, Lassig M. Adaptive evolution of transcription factor binding sites. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg OG, von Hippel PH. Selection of DNA binding sites by regulatory proteins. Statistical-mechanical theory and application to operators and promoters. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:723–750. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg OG, von Hippel PH. Selection of DNA binding sites by regulatory proteins. II. The binding specificity of cyclic AMP receptor protein to recognition sites. J Mol Biol. 1988;200:709–723. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount ZD, Barrick JE, Davidson CJ, Lenski RE. Genomic analysis of a key innovation in an experimental Escherichia coli population. Nature. 2012;489:513–518. doi: 10.1038/nature11514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Callan C. Evolutionary comparisons suggest many novel cAMP response protein binding sites in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2404–2413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308628100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron A, Redfield R. Non-canonical CRP sites control competence regulons in Escherichia coli and many other gamma-proteobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6001–6015. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TF, Remold SK, Lenski RE, Schneider D. Expression profiles reveal parallel evolution of epistatic interactions involving the CRP regulon in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour Y, Kiley P, Donohue T. Reconstruction of the core and extended regulons of global transcription factors. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani R, Gallo R, Lio P. Molecular evolution of nitrogen fixation: the evolutionary history of the nifD, nifK, nifE, and nifN genes. J Mol Evol. 2000;51:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s002390010061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: phylogenetic inference package, version 3.52. 1993. Distributed by the author. Department of Genetics, University of Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer HM. Genetic regulation of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:352–386. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.352-386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama-Castro S, et al. RegulonDB version 7.0: transcriptional regulation of Escherichia coli K-12 integrated within genetic sensory response units (Gensor Units) Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D98–D105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerland U, Hwa T. On the selection and evolution of regulatory DNA motifs. J Mol Evol. 2002;55:386–400. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh CS, Bogan AA, Joachimiak M, Walther D, Cohen FE. Co-evolution of proteins with their interaction partners. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:283–293. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Perez AD, Gonzalez Gonzalez E, Espinosa Angarica V, Vasconcelos AT, Collado-Vides J. Impact of transcription units rearrangement on the evolution of the regulatory network of gamma-proteobacteria. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostick DO, Green J, Irvine AS, Gasson MJ, Guest JR. A novel regulatory switch mediated by the FNR-like protein of Lactobacillus casei. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 3):705–717. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-3-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostick DO, et al. Two operons that encode FNR-like proteins in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1523–1535. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:221–224. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger DC, Aiba H, Hurd D, Browning DF, Busby SJ. Transcription factor distribution in Escherichia coli: studies with FNR protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:269–278. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Scott C, Guest JR. Functional versatility in the CRP-FNR superfamily of transcription factors: FNR and FLP. Adv Microb Physiol. 2001;44:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(01)44010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberg R, Margalit H. Co-evolution of transcription factors and their targets depends on mode of regulation. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R62. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-7-r62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SD, et al. Integration of phenotypic metadata and protein similarity in Archaea using a spectral bipartitioning approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2096–2104. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka H, Hanamura A, Inada T, Aiba H. Mechanism of the down-regulation of cAMP receptor protein by glucose in Escherichia coli: role of autoregulation of the crp gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:3077–3159. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D355–D360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner H, Sofia H, Zumft W. Phylogeny of the bacterial superfamily of Crp-Fnr transcription regulators: exploiting the metabolic spectrum by controlling alternative gene programs. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:559–651. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo D, et al. Coevolution within a transcriptional network by compensatory trans and cis mutations. Genome Res. 2010;20:1672–1680. doi: 10.1101/gr.111765.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazazzera B, Beinert H, Khoroshilova N, Kennedy M, Kiley P. DNA binding and dimerization of the Fe-S-containing FNR protein from Escherichia coli are regulated by oxygen. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2762–2770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madan Babu M, Teichmann SA. Evolution of transcription factors and the gene regulatory network in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1234–1244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghnouj A, Abu-Bakr AA, Baumberg S, Stalon V, Vander Wauven C. Regulation of anaerobic arginine catabolism in Bacillus licheniformis by a protein of the Crp/Fnr family. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;191:227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashhadi Z, Zhang H, Xu H, White RH. Identification and characterization of an archaeon-specific riboflavin kinase. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2615–2618. doi: 10.1128/JB.01900-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue LA, Thompson W, Carmack CS, Lawrence CE. Factors influencing the identification of transcription factor binding sites by cross-species comparison. Genome Res. 2002;12:1523–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.323602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L, Mettert E, Kiley P. Regulation of FNR dimerization by subunit charge repulsion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33268–33343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraki N, et al. X-ray crystal structure of the light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase. Nature. 2010;465:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature08950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepusz T, Sasidharan R, Paccanaro A. SCPS: a fast implementation of a spectral method for detecting protein families on a genome-wide scale. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paccanaro A, Casbon JA, Saqi MA. Spectral clustering of protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1571–1580. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JC, Groisman EA. Evolution of transcriptional regulatory circuits in bacteria. Cell. 2009;138:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipenbacher P, et al. ProClust: improved clustering of protein sequences with an extended graph-based approach. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(Suppl 2):S182–S191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_2.s182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Projan SJ, Monod M, Narayanan CS, Dubnau D. Replication properties of pIM13, a naturally occurring plasmid found in Bacillus subtilis, and of its close relative pE5, a plasmid native to Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5131–5139. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5131-5139.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2012. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; [Google Scholar]

- Raymond J, Siefert JL, Staples CR, Blankenship RE. The natural history of nitrogen fixation. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:541–554. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DJ, Rice DW, Guest JR. Homology between CAP and Fnr, a regulator of anaerobic respiration in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Fujita N, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A. Novel roles of cAMP receptor protein (CRP) in regulation of transport and metabolism of carbon sources. PloS One. 2011;6:e20081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierro N, Makita Y, de Hoon M, Nakai K. DBTBS: a database of transcriptional regulation in Bacillus subtilis containing upstream intergenic conservation information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D93–D96. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro S, Guest JR. FNR and its role in oxygen-regulated gene expression in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;6:399–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro S, et al. Interconversion of the DNA-binding specificities of two related transcription regulators, CRP and FNR. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1831–1838. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JR, Wray GA. Rapid evolution of cis-regulatory sequences via local point mutations. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1764–1770. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stülke J, Hillen W. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:195–396. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Collado-Vides J, Stormo GD. A comparative genomics approach to prediction of new members of regulons. Genome Res. 2001;11:566–584. doi: 10.1101/gr.149301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium. Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D71–D75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Palas MA, Flores E, Herrero A. NtcA, a global nitrogen regulator from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus that belongs to the Crp family of bacterial regulators. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1853–1859. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite RD, et al. Clustering of Pseudomonas aeruginosa transcriptomes from planktonic cultures, developing and mature biofilms reveals distinct expression profiles. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner J, Lolkema J. CcpA-dependent carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:475–490. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.475-490.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Su Z. Computational prediction of cAMP receptor protein (CRP) binding sites in cyanobacterial genomes. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, et al. Correlated evolution of transcription factors and their binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2972–2978. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D, Constantinidou C, Hobman J, Minchin S. Identification of the CRP regulon using in vitro and in vivo transcriptional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5874–5967. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]