Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the major outer leaflet constituent of the Gram-negative outer membrane (OM) bilayer. A bipartite protein complex of LptD and LptE assembles LPS into the OM. It has been established that LptE assists folding and assembly of its β-barrel partner LptD, yet reported biochemical evidence suggested additional LptE functions. Here, we isolated dominant negative lptE mutations, seeking to inform these functions. The lptE14 mutation increased OM permeability to erythromycin, even when the wild-type lptE gene was present. We show that the lptE14 mutation does not cause a defect in either LptD assembly or LPS export. A spontaneous IS1 insertion in secA suppressed lptE14 erythromycin sensitivity by removing the C-terminal SecB-binding domain of SecA. While this suppressor mutation broadly impeded SecB-dependent secretion of preproteins, we show that suppression was a direct and specific consequence of reduced LptD levels in the OM. We suggest that lptE14 causes poor plugging of the LptD β barrel and that a reduction of ineffectively plugged LptD-LptE14 complexes in the OM decreases permeability to erythromycin. Hence, lptE14 supports a proposed plug-and-barrel LptE-LptD arrangement.

INTRODUCTION

The cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria consists of an inner membrane (IM) and an outer membrane (OM) that are separated by an aqueous periplasmic space. The OM is an essential organelle, serving as a selective permeability barrier that permits influx of nutrients while excluding toxins and hydrophobic antibiotics (1). The glycolipid lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is central to OM barrier function, forming the outer leaflet of this lipid bilayer (2, 3). LPS is synthesized at the IM and must traverse the aqueous periplasmic environment to reach the OM, where it is assembled at the cell surface (4). Seven essential LPS transport (Lpt) proteins involved in this pathway have now been identified in Escherichia coli (5). The Lpt proteins collectively form a transenvelope complex that delivers LPS from the IM to the OM (6). The current model of LPS transport posits that LptBFG, which constitute an ABC transporter, extract LPS from the IM (5, 7–11), and then the molecule is passed to the periplasmic domain of LptC (8, 10–12). Next, additional ATP hydrolysis by LptBFG facilitates passage of LPS from LptC to LptA in the periplasm (6, 11–13). Multiple LptA proteins polymerize in end-on-end fashion to span the periplasm, from the IM LptBCFG components to the OM LptDE complex (14–16). The soluble N-terminal domain of LptD is homologous to LptA and likely serves as the final subunit in the LptA multimer (6, 13). As a consequence of this docking, LPS is thought to flow from LptA to LptD (11). The final steps in the Lpt pathway insert LPS into the OM outer leaflet and are accomplished by the LptDE complex but remain mechanistically poorly understood.

LptD is a large β-barrel outer membrane protein (OMP), and the biogenesis of this protein is an especially complex process. Once secreted into the periplasm, LptD is largely reliant on the chaperone function of SurA, which maintains the molecule in an assembly-competent state and delivers it to the Bam complex, which assembles β-barrel proteins into the OM (17–19). Before LptD reaches Bam, a pair of disulfide bonds forms in a process that requires DsbA (20–22). Late in assembly, once the protein is inserted in the OM, these disulfide bonds are rearranged (22). The properly oxidized LptD protein (LptDOX) comprises the mature form that is functional in LPS export (20, 22).

Genetic analysis of the lptE6 mutation demonstrated that LptE is required for the biogenesis of mature LptD (23). This mutation caused a severe reduction in LptD levels and a concomitant increase in OM permeability to antibiotics. OM permeability could be suppressed by mutations in bamA and lptD that restored levels of mature LptD. More recently, it has emerged that LptE is required to guide the proper oxidation of LptD, once assembly of the β-barrel domain into the OM is complete (22). At the OM, LptE forms a high-affinity stable 1:1 complex with LptD (24). Indeed, cross-linking experiments demonstrated extensive interaction sites across the surface of LptE and prompted a model of the LptE-LptD plug-and-barrel arrangement where LptE resides in the lumen of the LptD β barrel (25). In addition to its role in LptD assembly, purified LptE has been shown to specifically bind LPS, hinting that the protein may also function directly in LPS assembly into the OM (24).

While the isolation of lptE6 was valuable in understanding LptD assembly, no mutations isolated to date have further informed the other functions of LptE. In particular, the function of LptE in the LPS assembly process in vivo is wholly unknown. This study set out to identify and characterize novel mutations that affect the LptD assembly-independent functions of LptE.

The LptDE complex is extremely stable in vivo, so we reasoned that a properly assembled LptDE complex that contained a nonfunctional LptE protein could probably not be rescued by functional LptE provided in trans. If so, then an excess of functionally compromised mutant LptE could then decrease the levels of functional LptDE complex even in the presence of lptE+, thereby disrupting OM integrity. Such mutations would therefore be dominant negative. On the other hand, lptE mutations impairing early steps in LptD biogenesis—before the LptDE complex is formed—such as lptE6, would be recessive. Hence, we sought to isolate dominant negative lptE mutations as a means of enriching for genetic alterations that affect the LptD assembly-independent functions of LptE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cultures were routinely grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Where appropriate, growth media were supplemented with the following: 50 μg/ml ampicillin (Amp), 25 μg/ml kanamycin, 25 μg/ml tetracycline, 50 μg/ml erythromycin (Ery), 10 μg/ml rifampin, 625 μg/ml bacitracin, 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose, and 0.2% (wt/vol) l-arabinose (Ara).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− endA1 thi-1 recA1 relA1 gyrA96 deoR nupG ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 hsdR17(rK− mK+) λ− | |

| MC4100 | F− araD139 Δ(arg-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 thi | 26 |

| NR754 | MC4100 Ara+ | 27 |

| JW3584 | BW25113 ΔsecB::kan | 28 |

| JY17 | NR754/plptE6 | 23 |

| JY18 | NR754 ΔlptE2::kan/plptE6 | 23 |

| JY32 | NR754/plptE+ | This study |

| JY33 | NR754 ΔlptE2::kan/plptE+ | This study |

| JY34 | NR754/plptE14 | This study |

| JY35 | NR754 ΔlptE2::kan/plptE14 | This study |

| JY105 | JY33 secA+ leuA::Tn10 | This study |

| JY106 | JY33 secA827::IS1 leuA::Tn10 | This study |

| JY107 | JY35 secA+ leuA::Tn10 | This study |

| JY108 | JY35 secA827::IS1 leuA::Tn10 | This study |

| MG934 | NR754 ΔlptE secB+/plptE+ | This study |

| MG935 | NR754 ΔlptE secB+/plptE14 | This study |

| MG949 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔsecB::kan/plptE+ | This study |

| MG950 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔsecB::kan/plptE14 | This study |

| MG1053 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA+ leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE+/plptD | This study |

| MG1054 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA827::IS1 leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE+/plptD | This study |

| MG1055 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA+ leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE14/plptD | This study |

| MG1056 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA827::IS1 leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE14/plptD | This study |

| MG1057 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA+ leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE+/psfmC-lptD | This study |

| MG1058 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA827::IS1 leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE+/psfmC-lptD | This study |

| MG1059 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA+ leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE14/psfmC-lptD | This study |

| MG1060 | NR754 ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 secA827::IS1 leuA::Tn10/pBAD33::lptE14/psfmC-lptD | This study |

| JCM537 | MC4100 Arar/− ΔpldA ΔmlaC | 29 |

| Plasmids | ||

| plptE+ | lptE+ cloned into pBAD18 | 30 |

| pBAD33::lptE+ | lptE+ cloned into pBAD33 | This study |

| pBAD33::lptE14 | lptE14 cloned into pBAD33 | This study |

| plptD | lptD cloned into pET23/42 | 30 |

| psfmC-lptD | SfmC signal sequence fused to LptD mature sequence, cloned into pET23/42 | N. Ruiz |

Random PCR mutagenesis and antibiotic sensitivity screening.

The oligonucleotide primers used in this study are provided in Table 2. Random PCR mutagenesis was performed using a GeneMorphII random mutagenesis kit (Agilent) and 125 ng each of primers 5lptE670828 and 3lptE671409 to amplify lptE from 0.1 ng of the plptE+ template in 40 cycles. A heavy mutagenesis was achieved, yielding an average of 2 to 5 coding changes per lptE amplicon. The MEGAWHOP cloning method was used to generate mutagenized plasmid pools (31). Briefly, the mutagenized amplicons were purified and 250 ng was used to prime PCR with about 50 ng of plptE+, generating a pool of nicked plasmids that contained mutagenized lptE which was subsequently treated with DpnI to digest the plptE+ template. Plasmid pools were passaged through E. coli DH5α with transformants selected on LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% glucose. Plasmid pools were then isolated from DH5α and electroporated into competent strain NR754, and transformants were selected on LB medium supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% glucose.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| 5lptE670828 | TTAATCACCGCCGGGTGT |

| 3lptE671409 | CGGGTACAACCGAATCATCA |

| lptE_g71a_F | GCTGGCATCTGCATGATACCACGCAG |

| lptE_g71a_R | CTGCGTGGTATCATGCAGATGCCAGC |

| lptE_c159g_F | GTGCGGTGCGTAAGCAGTTACGTCTG |

| lptE_c159g_R | CAGACGTAACTGCTTACGCACCGCAC |

| lptE_t192a_F | GGTGTCGAGTTGCTTGAAAAAGAAACCACGCGTAAG |

| lptE_t192a_R | CTTACGCGTGGTTTCTTTTTCAAGCAACTCGACACC |

| lptE_t302c_F | CAGAGTATCAGATGACCATGACGGTTAATGC |

| lptE_t302c_R | GCATTAACCGTCATGGTCATCTGATACTCTG |

| lptE_t408c_F | CAAATGGCGTTAGCGAACGATAACGAACAAGACATG |

| lptE_t408c_R | CATGTCTTGTTCGTTATCGTTCGCTAACGCCATTTG |

| lptE_c556t_F | AACGCCTGCATGCGTCTCCACCACGCTGGGTAACT |

| lptE_c556t_R | AGTTACCCAGCGTGGTGGAGACGCATGCAGGCGTT |

| JY10 | ATGCTGATGCACCACGTAACG |

| JY18 | TTGCAGCTTTTTCATTGTCTTAAACC |

| SacI_lptE | AAAGAGCTCGCGCGGGAGGAAGC |

| lptE_R_XbaI | GATGCCTCTAGAACCGAATCATCAGTTACCCA |

Individual NR754 transformant colonies were then identified, picked with a Genetix Qpix2 XT colony picker, and transferred to 96-well plates filled with 200 μl LB broth supplemented with ampicillin and 0.2% glucose. In total, 3,700 transformants were picked. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Plate cultures were replica plated onto LB medium-ampicillin plates additionally supplemented with either 0.2% glucose, 0.2% arabinose, 0.2% arabinose with erythromycin, 0.2% arabinose with rifampin, or 0.2% arabinose with bacitracin. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. Plates were examined to identify antibiotic sensitivity, and mutant strains were isolated.

Haploid lptE strains were generated following P1vir transduction of ΔlptE2::kan. The kanamycin resistance cassette was cured from this disruption with plasmid pCP20, as previously described (32).

Plasmid construction.

Site-directed mutagenesis of plptE+ was used to construct plasmids carrying individual mutations of lptE14. The primers used are listed in Table 2. To generate pBAD33::lptE+ plasmids, the lptE allele was PCR amplified from plptE+ plasmids using primers SacI_lptE and lptE_R_XbaI, digested with SacI and XbaI, and cloned into correspondingly digested pBAD33.

Immunoblot analysis.

For logarithmic-phase protein samples, culture density was determined by measurement of the A600, and 1 ml of the culture was pelleted and resuspended in a volume of SDS-PAGE sample buffer corresponding to the A600 divided by 7. For stationary-phase protein samples, 0.25 ml of the culture was pelleted and resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer corresponding to the A600 divided by 40. When appropriate, samples were prepared under nonreducing conditions where SDS-PAGE sample buffer lacked β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were boiled for 5 min and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. To detect LptD, 20 μl of protein sample was loaded; for detection of all other proteins, samples were first diluted 1:25 in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and then 20 μl was loaded. The oxidation state of LptD was assessed by comparing the migration of the protein when subjected to SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. Reduced LptD species migrate further than the oxidized protein under these conditions, and incorrectly oxidized LptD also displays altered migration, as described elsewhere (20).

Resolved proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were then blocked in milk and incubated overnight with polyclonal rabbit antisera: anti-LptD (1:5,000), anti-LptE (1:30,000), anti-DegP (1:30,000), anti-OmpA (1:20,000), and anti-LamB (1:20,000). Membranes were subsequently incubated with donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (used at 1:10,000) for 2 h. Blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) and visualized by exposure of X-ray film (Denville).

Linkage mapping.

Linkage mapping using pools of random Tn10 insertions was used to isolate transposon insertions linked to suppressing loci, as previously described (29). The secA IS1 insertions were found to be approximately 40% linked to leuA::Tn10. The mutation was confirmed by PCR amplification of the secA locus with primers JY10 and JY18 and sequencing of the resultant amplicon. The IS1 insertion increased the amplicon size by 777 bp compared to that for the secA+ strain.

Lipid A palmitoylation assay.

Overnight cultures were subcultured 1:100 into 5 ml of fresh LB broth supplemented with 0.2% arabinose to which 5 μCi/ml of 32PO4 was added. Cultures were grown at 37°C for 2.5 h. LPS was purified from radiolabeled bacteria, and lipid A was released by mild acid hydrolysis, as previously described (33). Equal quantities of radiolabeled lipid A were spotted onto a silica thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (Macherey-Nagel) and developed with chloroform, pyridine, 88% formic acid, and water (50:50:16:5, vol/vol). Plates were then dried and exposed to a phosphor screen overnight. Samples were visualized using a Typhoon scanner (GE).

RESULTS

Screen for isolating dominant negative lptE alleles identifies lptE14.

To generate mutant lptE alleles, random error-prone PCR mutagenesis was used to mutagenize plptE+. Pools of mutagenized plasmids were transformed into strain NR754 with wild-type lptE. Increased OM permeability to hydrophobic antibiotics is a hallmark of OM biogenesis defects (34). To identify dominant negative alleles, lptE diploid transformants were screened for sensitivity to hydrophobic antibiotics erythromycin, rifampin, and bacitracin in media supplemented with arabinose (to fully induce expression of the plasmid-encoded mutagenized lptE allele).

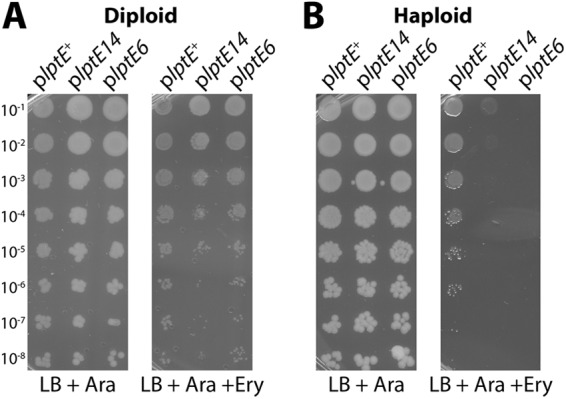

One isolated, haploid-viable allele, lptE14, showed significant sensitivity to erythromycin when expressed in diploid with chromosomally encoded lptE+ (Fig. 1A). Hence, this mutant was dominant negative, compromising the OM barrier, despite the presence of a functional LptE protein. Notably, the LptD assembly-defective mutation lptE6 was recessive in diploid analysis, despite its reported acute antibiotic sensitivity in haploid (23). In haploid strains which contain the chromosomal ΔlptE2::kan null allele, the plptE14-carrying mutant was viable and actually showed no growth defect compared to the plptE+-carrying control (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Clearly, the LptE14 protein was proficient in the essential functions required of LptE. However, when OM permeability was assessed in the lptE14 haploid strain, sensitivity to erythromycin was more pronounced (Fig. 1B). Additionally, the lptE14 mutation caused increased sensitivity to rifampin (not shown).

Fig 1.

LptE14 expression induces OM permeability to erythromycin antibiotics. Stationary-phase cultures of lptE diploid strains expressing chromosomally encoded lptE+ and either plptE+ (JY32), plptE14 (JY34), or plptE6 (JY17) (A) or cultures of ΔlptE2::kan strains carrying either plptE+ (JY33), plptE14 (JY35), or plptE6 (JY18) (B) were serially diluted and replica plated onto LB plates supplemented with ampicillin and Ara or plates additionally supplemented with 50 μg/ml Ery. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C.

LptE14 does not impair LptD assembly.

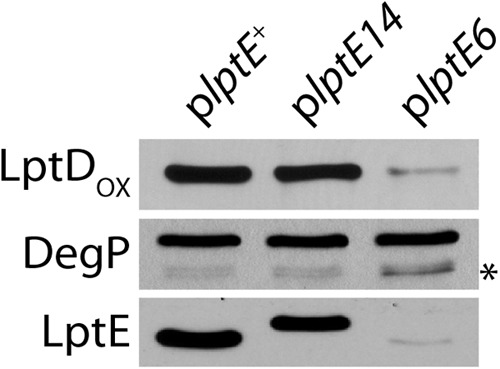

We sought to isolate mutations that affect LptE function in OM biogenesis, but not because they caused defects in LptD assembly. Mature, OM-assembled LptD forms two intramolecular disulfide bonds, and LptE is required for this oxidation (20, 23). Therefore, the oxidized form of the protein (LptDOX) can be used to assess the efficiency of the LptD assembly process. We examined the levels of LptDOX from stationary-phase lptE haploid culture samples processed under nonreducing conditions. The levels of LptDOX in the plptE14 mutant were the same as those in the plptE+ control strain (Fig. 2). Additionally, we did not detect activation of DegP proteolytic activity, which has been described as a hallmark of defective LptD assembly in the plptE6 mutant (23) (Fig. 2). These results demonstrated that the lptE14 mutation did not impair LptD assembly. Rather, the increased OM permeability phenotype of the plptE14 mutant must have been due to a deficiency in some other LptE function. Hence, the lptE14 allele had satisfied the criteria of our screen.

Fig 2.

LptE14 is stable and supports LptD assembly. Protein samples from stationary-phase cultures of ΔlptE2::kan strains expressing plptE+ (JY33), pltE14 (JY35), or plptE6 (JY18) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-LptD, anti-DegP, and anti-LptE antibodies. Samples in LptDOX were prepared under nonreducing conditions. LptE14 displays altered migration in SDS-PAGE. *, a DegP degradation product that appears upon protease activation.

The mutations in lptE14 introduced six amino acid substitutions throughout the protein: R24H, N53K, D64E, I101T, K136N, and R186C. These mutations did not affect the stability of LptE14, with the protein expressed at levels comparable to those of wild-type LptE (Fig. 2). We wondered if any individual substitution was directly responsible for the OM permeability caused by lptE14. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we generated single substitution mutations in plasmid plptE+, and the resultant strains were assessed in both diploid and haploid for sensitivity to erythromycin. No single mutation was sufficient to confer the plptE14 mutant phenotype (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Owing to the many possible combinations of substitutions, we did not further pursue identification of a minimal subset of changes sufficient to induce OM permeability.

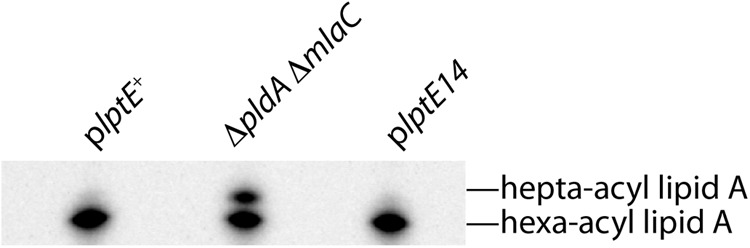

LptE14 does not affect LPS export.

Biochemical evidence suggests that the wild-type E. coli LptE protein directly and specifically binds LPS (24). Since the increased OM permeability associated with lptE14 could not be attributed to faulty LptD assembly, another possible cause for permeability might be that the LptE14 protein has been functionally compromised in the process of LPS export. Under normal conditions, LPS is the predominant lipid species of the OM outer leaflet (3); phospholipids are actively excluded from the outer leaflet but can become mislocalized when Lpt components are depleted and LPS export is impaired (7, 30, 35). Mislocalization of phospholipids in the outer leaflet of the OM activates the OM enzyme PagP, which then uses these phospholipids as the substrate for palmitoylation of the hexa-acyl form of lipid A to produce a hepta-acyl lipid A form (33). This modification has previously been used to detect LPS export defects (30, 35). To determine if PagP activity was stimulated by the lptE14 mutation, we extracted lipid A from the haploid plptE14 mutant and the corresponding control plptE+ strain. Lipid A was also extracted from a ΔpldA ΔmlaC mutant strain defective in removing mislocalized phospholipids as a positive control for detection of hepta-acyl lipid A species (29). Cultures were grown to logarithmic phase in medium radiolabeled with 32P, and lipid A was extracted, developed by thin-layer chromatography, and finally detected by autoradiography (33). Hexa-acyl lipid A was detected in all strains examined (Fig. 3). While hepta-acyl lipid A was readily apparent in the control ΔpldA ΔmlaC strain, we were unable to detect this PagP-modified species in lipid A prepared from either the mutant plptE14 strain or the plptE+ control (Fig. 3). The absence of lipid A palmitoylation suggested that LPS export was not significantly impaired in the plptE14 mutant, at least not to a level at which PagP becomes activated.

Fig 3.

LptE14 does not induce palmitoylation of lipid A by PagP. LPS was extracted from stationary-phase cultures of ΔlptE2::kan strains carrying plptE+ (JY33) and plptE14 (JY35), grown in LB medium supplemented with 0.2% arabinose, and radiolabeled with 32P. Samples were developed by TLC and then visualized by phosphorimaging. The ΔpldA ΔmlaC mutant (JCM537) was included as a positive control for hepta-acyl lipid A.

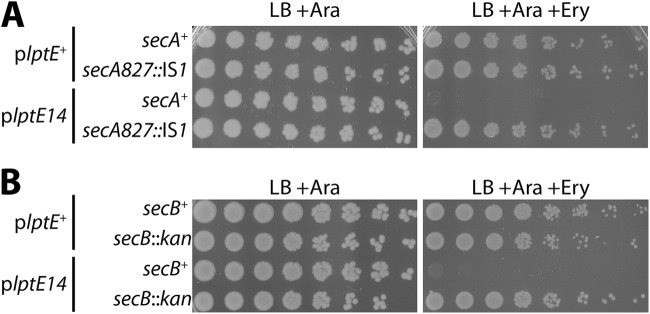

Inhibition of SecB-dependent secretion suppresses plptE14 OM permeability.

Since the plptE14 mutant appeared to be neither defective in LptD assembly nor impaired in LPS export, it must have been deficient in a distinct function. To determine this function, we sought to isolate and identify second-site mutations that restore the integrity of the OM permeability barrier and suppress the sensitivity of the haploid plptE14 strain to erythromycin. Spontaneous suppressors were selected from medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml erythromycin. Mutations suppressing the erythromycin sensitivity of plptE14 arose at frequencies of approximately 10−6. Linkage mapping was used to determine the chromosomal loci of suppressors.

One class of erythromycin-resistant suppressors mapped to the secA locus and was found to have an IS1 insertion in the 3′ region of secA; such IS1 insertion mutations were isolated independently three times. These suppressors fully restored the erythromycin resistance of the plptE14 mutant to the levels of the plptE+ strain (Fig. 4A). Additionally, these suppressors also restored resistance to rifampin (not shown). The effect of the IS1 insertions was to truncate the SecA protein at either amino acid 827 (secA827::IS1) or amino acid 830 (secA830::IS1), thereby removing the final 95 or 92 amino acids, respectively. The region removed included the entire SecB-binding domain (36). SecB is a secretion-specific cytoplasmic chaperone that maintains preproteins in a secretion-competent form (37). SecB binds with high affinity to SecA at the SecYEG translocon (38); in this way, SecB delivers preproteins to the secretion machinery.

Fig 4.

Mutations in secA or secB suppress plptE14 OM permeability. (A) Stationary-phase cultures of ΔlptE2::kan strains carrying plptE+ with secA+ (JY105) or with secA827::IS1 (JY106) and strains carrying plptE14 with secA+ (JY107) or with secA827::IS1 (JY108) were serially diluted and replica plated onto LB medium with 0.2% arabinose plates or plates additionally supplemented with 50 μg/ml erythromycin. (B) Likewise, cultures of ΔlptE strains carrying plptE+ with secB+ (MG934) or with ΔsecB::kan (MG949) and strains carrying plptE14 with secB+ (MG935) or ΔsecB::kan (MG950) were serially diluted and replica plated. Plates were incubated at 37°C.

It seemed likely that the secA827::IS1 mutation would inhibit the SecB-dependent secretion pathway by removing the SecB-binding site in SecA. Indeed, a deletion-insertion ΔsecB::kan allele was also able to fully suppress plptE14 sensitivity to erythromycin (Fig. 4B). Thus, inhibition of SecB-dependent secretion seemed central to restoring OM barrier integrity in plptE14. To directly confirm that the secA827::IS1 mutation impeded secretion, protein samples from logarithmic-phase cultures of secA+ and secA827::IS1 strains were immunoblotted with antibodies to detect OMPs LamB and OmpA and the periplasmic protein maltose-binding protein (MBP). The secretion of these proteins has been directly shown to proceed via the SecB pathway (39–41). Upon export from the cytoplasm, the signal sequence is cleaved from the N terminus of these proteins. We observed clear accumulation of the signal sequence-carrying preprotein forms of these proteins in the secA827::IS1 strains, confirming that secretion of these proteins was being impaired in this background (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). As expected in the secA827::IS1 background, preproteins were detected in strains carrying either plptE14 or functional plptE+. Collectively, the data confirmed that reducing the secretion of SecB-dependent substrates was an effective strategy to restore the barrier function of the OM of the plptE14 mutant.

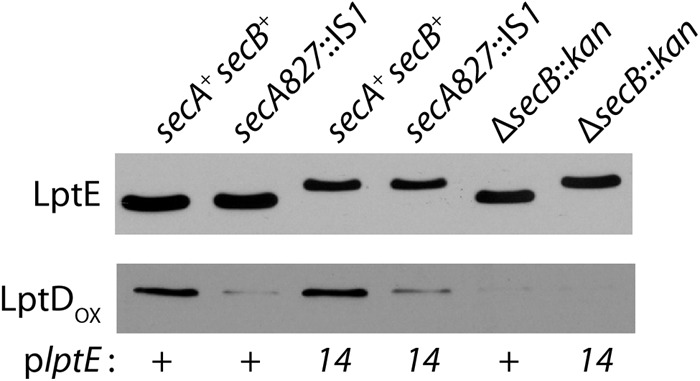

secA827::IS1 does not affect LptE14 levels but lowers LptDOX.

Clearly, the secA827::IS1 suppressor was affecting a broad range of secreted proteins destined for the periplasm or OM, possibly including LptE and/or LptD. One possibility was that secA827::IS1 restored OM barrier function by lowering the amount of LptE14 protein that reached the OM. However, immunoblotting indicated that secA827::IS1 did not reduce the levels of LptE or LptE14 compared to those for the secA+ controls, and no preprotein forms were detected (Fig. 5). Likewise, ΔsecB::kan did not lower the levels of LptE compared to those for the secB+ strains (Fig. 5). Simply, restoration of OM integrity could not be attributed to lowered levels of the mutant protein. More broadly, the data demonstrated that LptE secretion is SecB independent.

Fig 5.

LptDOX levels are decreased by secA and secB suppressor mutations. ΔlptE strains carrying plasmid plptE+ with secA+ secB+ (JY105), with secA827::IS1 secB+ (JY106), or with secA+ ΔsecB::kan (MG949) and ΔlptE strains carrying plptE14 with secA+ secB+ (JY107), with secA827::IS1 secB+ (JY108), or with secA+ ΔsecB::kan (MG950) were grown to stationary phase, and protein samples were prepared under reducing (LptE) or nonreducing (LptDOX) conditions and immunoblotted with anti-LptE or anti-LptD antisera.

The SecB-dependent secretory pathway is favored by OMPs; since LptD is an OMP, it seemed likely that the secA827::IS1 and ΔsecB::kan suppressor mutations would affect LptD biogenesis. We examined the levels of LptDOX by immunoblotting stationary-phase protein samples. Both suppressor mutations, secA827::IS1 and ΔsecB::kan, drastically lowered the levels of LptDOX in comparison to those for the secA+ secB+ strains (Fig. 5). Although we did not detect the precursor form of the LptD protein, we think it likely that these suppressors were reducing the amount of LptD that was secreted from the cytoplasm.

Restoring LptDOX levels abrogates secA827::IS1 suppression.

The secA827::IS1 suppressor must certainly cause broad alterations to the composition of both the OM and the periplasm, and suppression might require such nonspecific reductions of envelope proteins. However, the striking reduction in LptDOX caused by secA827::IS1 and ΔsecB::kan raised the more intriguing possibility that these suppressors might remedy the OM permeability defect caused by LptE14 by specifically reducing the levels of LptDOX and correspondingly lowering the number of LptD-LptE14 complexes in the OM. To test this hypothesis, we sought to increase LptDOX levels in the secA827::IS1 background and determine whether this restored the erythromycin sensitivity conferred by lptE14.

Preproteins are directed to the Sec machinery for translocation from the cytoplasm by either the posttranslational, SecB pathway or the cotranslational, signal recognition particle (SRP) pathway (42). The secretory route taken by nascent preproteins is determined by the composition of their signal sequence; a heterologous signal sequence can redirect the secretory route of a protein (43, 44). The signal sequence of the periplasmic pilin chaperone SfmC has been shown to direct secretion via the SRP pathway (45). An SfmC-LptD fusion where the native LptD signal sequence has been replaced by the SfmC signal sequence was expressed from plasmid psfmC-lptD. The SfmC-LptD fusion was fully able to complement a ΔlptD::kan2 null mutation. This was unsurprising, since the protein sequence of the mature, secreted SfmC-LptD fusion was identical to that of the wild-type LptD protein.

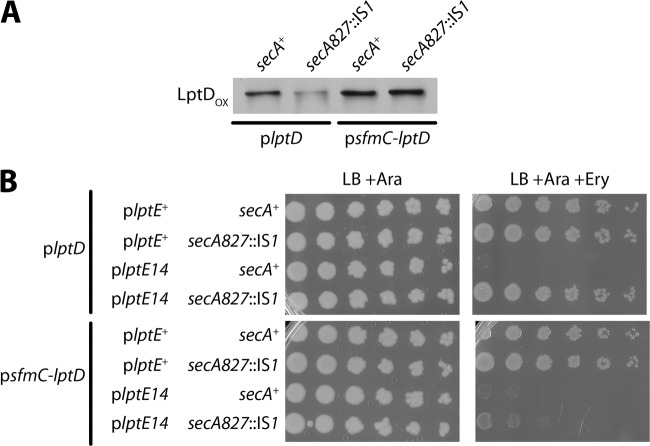

We then constructed haploid plptE+ and plptE14 strains carrying either secA827::IS1 or secA+ and expressing either the plasmid-encoded SfmC-LptD fusion or wild-type LptD. We then deleted the native lptD+ gene in these strains by introducing ΔlptD::kan2 so that only plasmid-encoded LptD was expressed. To maintain plasmid compatibility, lptE alleles were expressed from pBAD33.

Immunoblots were performed to determine whether rerouting LptD to the SRP-dependent pathway would increase LptDOX levels in the secA827::IS1 background. In the pBAD33::lptE14 mutant, we observed that LptDOX levels from plasmid plptD+ were significantly reduced by secA827::IS1 (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, the levels of the LptDOX from psfmC-lptD were unaffected by secA827::IS1 and were equivalent to the levels in secA+ (Fig. 6A). Clearly, routing LptD secretion via SRP was able to circumvent the effect of the secA suppressor mutation and maintain wild-type levels of functional LptD at the OM.

Fig 6.

Routing of LptD secretion via the SRP pathway restores levels of LptDOX and abolishes secA827::IS1 suppression. (A) Protein samples were obtained from stationary-phase cultures of ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 strains carrying pBAD33::lptE14 with plptD and either secA+ (MG1055) or secA827::IS1 (MG1056) or carrying pBAD33::lptE14 with psfmC-lptD and either secA+ (MG1059) or secA827::IS1 (MG1060). Samples were prepared under nonreducing conditions and immunoblotted with anti-LptD. (B) Stationary-phase cultures were serially diluted and plated onto LB plates with 0.2% arabinose or plates additionally supplemented with 50 μg/ml erythromycin. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. Cultures were of ΔlptE ΔlptD::kan2 strains carrying pBAD33::lptE+ and either plptD with secA+ (MG1053), plptD with secA827::IS1 (MG1054), psfmC-lptD with secA+ (MG1057), or psfmC-lptD (MG1058); alternatively, strains carried pBAD33::lptE14 and either plptD with secA+ (MG1055), plptD with secA827::IS1 (MG1056), psfmC-lptD with secA+ (MG1059), or psfmC-lptD (MG1060).

We next examined if the increased LptDOX derived from psfmC-lptD altered the secA827::IS1 suppression of pBAD33::lptE14 mutant OM permeability. We found that secA827::IS1 was still able to suppress erythromycin sensitivity when wild-type LptD was expressed from plptD+ (Fig. 6B). However, when the SfmC-LptD fusion was expressed, suppression was abolished and erythromycin sensitivity was restored (Fig. 6B). The SfmC-LptD fusion itself did not seem to cause any increase in OM permeability, since the pBAD33::lptE+ strain remained fully resistant to erythromycin. We conclude that the secA827::IS1 and ΔsecB::kan suppressors act by specifically reducing the amount of LptD-LptE14 complexes in the OM.

DISCUSSION

While LptE is central to the correct assembly and oxidation of LptD, biochemical evidence suggested that it has additional roles, including active involvement in the LPS insertion process carried out by the OM LptDE complex (24). To gain insight into these additional roles, we screened for dominant negative lptE mutations. The lptE14 mutation satisfied the criteria of our screen: it exhibited compromised OM integrity, despite the presence of functional lptE+ in diploid analysis, yet it was fully competent in assisting LptD assembly and oxidation in haploid strains. In these regards, lptE14 was quite different from previously characterized mutations such as lptE6, which is recessive in diploid analysis and where impaired LptD assembly is the underlying cause of increased OM permeability (23). For these reasons, we believe that lptE14 defines a new class of mutations that affects a distinct function of LptE.

Purified LptE binds specifically to LPS molecules (24). Thus, it is possible that lptE14 impaired this binding or otherwise interfered with LPS transport. To compensate for such LPS assembly defects, phospholipids flip from the inner leaflet of the OM to the outer leaflet, and this triggers the enzymatic activity of PagP (30, 35). However, we could not detect PagP activation in the lptE14 mutant strain. If LptE14 was impairing LPS export, it was doing so at levels where PagP activation could not be detected. Such a mild defect does not seem to account for the significant sensitivity to erythromycin that we observe in the mutant strain. Hence, it is unlikely that LptE14 is defective in LPS transport.

We suspected that the nature of the lptE14 defect might be informed by examining suppressor mutations. The erythromycin sensitivity of lptE14 could be suppressed by IS1 insertions in secA. Specifically, secA827::IS1 restored OM barrier integrity by inhibiting the posttranslational SecB-dependent secretion pathway that is utilized preferentially by OMPs. Indeed, a secB null allele was also a suppressor of lptE14. These suppressors answered our selection because they specifically reduced the levels of mature LptD. We demonstrated that rerouting the secretion of LptD via the cotranslational SRP pathway, circumventing the effect of secA827::IS1, abrogated suppression and restored the OM permeability to erythromycin caused by lptE14.

The very existence of the secA827::IS1 and ΔsecB::kan suppressors provides additional support to the argument that the mutant LptE14 protein is functional for LPS transport. If LptE14 was compromised in an LPS transport function, reducing the number of LptE14-LptD complexes would exacerbate the defect and not suppress it. We conclude that the LptE14 mutant protein is competent to assemble LptD and that—in the properly assembled LptD-LptE14 complex—LptE14 functions properly in LPS transport. What, then, is the defect cause by lptE14?

We propose a model whereby LptE14 is defective in plugging the LptD β-barrel lumen. The inability of LptE14 to properly plug LptD would provide a direct avenue for antibiotic entry into the cell. This model is consistent with the dominance of the lptE14 mutation: complexes of LptE14-LptD would permit antibiotic entry into the cell, despite the presence of wild-type, effectively plugged LptE-LptD complexes. The suppressors of lptE14 antibiotic sensitivity further support the model. These mutations reduce the levels of LptE14-LptD complexes within the OM. Decreasing the number of improperly plugged LptE14-LptD complexes would reduce the avenues for entry of antibiotics and restore higher levels of resistance. The lptE14 mutation provides genetic evidence for the plug-barrel architecture and supports biochemical studies that identified extensive LptE-LptD interactions and first proposed this LptE-LptD arrangement (25).

The lptE14 model poses important questions for the biogenesis and function of OM Lpt components. It has been suggested that the folded LptE plug is a template for LptD β-barrel assembly, hence the requirement of LptE for LptD assembly (25). LptE14 remains fully functional in its role during LptD biogenesis, yet our data suggest that LptE14 is a poor plug of the resulting β barrel. We think that this suggests that LptE assists LptD folding in a manner that is distinct from the plugging function. Indeed, the emerging landscape suggests that LptE has three distinct functions—LPS export, LptD assembly, and LptD plugging—each of which might be genetically separable.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GM34821 (to T.J.S.).

We thank members of the T. J. Silhavy lab for helpful comments and discussions and Jennifer Munko for her assistance in preparing the manuscript. We are grateful to Natividad Ruiz (Ohio State University) for the gift of psfmC-lptD, and to Wai-Leung Ng (Tufts University) for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02142-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ruiz N, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2006. Advances in understanding bacterial outer-membrane biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nikaido H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:593–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamio Y, Nikaido H. 1976. Outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: accessibility of phospholipid head groups to phospholipase c and cyanogen bromide activated dextran in the external medium. Biochemistry 15:2561–2570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:635–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruiz N, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2009. Transport of lipopolysaccharide across the cell envelope: the long road of discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:677–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Freinkman E, Okuda S, Ruiz N, Kahne D. 2012. Regulated assembly of the transenvelope protein complex required for lipopolysaccharide export. Biochemistry 51:4800–4806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sperandeo P, Pozzi C, Dehò G, Polissi A. 2006. Non-essential KDO biosynthesis and new essential cell envelope biogenesis genes in the Escherichia coli yrbG-yhbG locus. Res. Microbiol. 157:547–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sperandeo P, Lau FK, Carpentieri A, de Castro C, Molinaro A, Dehò G, Silhavy TJ, Polissi A. 2008. Functional analysis of the protein machinery required for transport of lipopolysaccharide to the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:4460–4469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sperandeo P, Cescutti R, Villa R, Di Benedetto C, Candia D, Dehò G, Polissi A. 2007. Characterization of lptA and lptB, two essential genes implicated in lipopolysaccharide transport to the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189:244–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Narita S-I, Tokuda H. 2009. Biochemical characterization of an ABC transporter LptBFGC complex required for the outer membrane sorting of lipopolysaccharides. FEBS Lett. 583:2160–2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okuda S, Freinkman E, Kahne D. 2012. Cytoplasmic ATP hydrolysis powers transport of lipopolysaccharide across the periplasm in E. coli. Science 338:1214–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tran AX, Dong C, Whitfield C. 2010. Structure and functional analysis of LptC, a conserved membrane protein involved in the lipopolysaccharide export pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 285:33529–33539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowyer A, Baardsnes J, Ajamian E, Zhang L, Cygler M. 2011. Characterization of interactions between LPS transport proteins of the Lpt system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 404:1093–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chng S-S, Gronenberg LS, Kahne D. 2010. Proteins required for lipopolysaccharide assembly in Escherichia coli form a transenvelope complex. Biochemistry 49:4565–4567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Merten JA, Schultz KM, Klug CS. 2012. Concentration-dependent oligomerization and oligomeric arrangement of LptA. Protein Sci. 21:211–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suits MDL, Sperandeo P, Dehò G, Polissi A, Jia Z. 2008. Novel structure of the conserved Gram-negative lipopolysaccharide transport protein A and mutagenesis analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 380:476–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ricci DP, Silhavy TJ. 2012. The Bam machine: a molecular cooper. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818:1067–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Denoncin K, Schwalm J, Vertommen D, Silhavy TJ, Collet J-F. 2012. Dissecting the Escherichia coli periplasmic chaperone network using differential proteomics. Proteomics 12:1391–1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vertommen D, Ruiz N, Leverrier P, Silhavy TJ, Collet J-F. 2009. Characterization of the role of the Escherichia coli periplasmic chaperone SurA using differential proteomics. Proteomics 9:2432–2443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruiz N, Chng SS, Hiniker A, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2010. Nonconsecutive disulfide bond formation in an essential integral outer membrane protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:12245–12250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braun M, Silhavy TJ. 2002. Imp/OstA is required for cell envelope biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1289–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chng S-S, Xue M, Garner RA, Kadokura H, Boyd D, Beckwith J, Kahne D. 2012. Disulfide rearrangement triggered by translocon assembly controls lipopolysaccharide export. Science 337:1665–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chimalakonda G, Ruiz N, Chng S-S, Garner RA, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2011. Lipoprotein LptE is required for the assembly of LptD by the β-barrel assembly machine in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2492–2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chng SS, Ruiz N, Chimalakonda G, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. 2010. Characterization of the two-protein complex in Escherichia coli responsible for lipopolysaccharide assembly at the outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:5363–5368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Freinkman E, Chng S-S, Kahne D. 2011. The complex that inserts lipopolysaccharide into the bacterial outer membrane forms a two-protein plug-and-barrel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2486–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Casadaban MJ. 1976. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104:541–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Button JE, Silhavy TJ, Ruiz N. 2007. A suppressor of cell death caused by the loss of σE downregulates extracytoplasmic stress responses and outer membrane vesicle production in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189:1523–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. doi:10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malinverni JC, Silhavy TJ. 2009. An ABC transport system that maintains lipid asymmetry in the Gram-negative outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:8009–8014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu T, McCandlish AC, Gronenberg LS, Chng S-S, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. 2006. Identification of a protein complex that assembles lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11754–11759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miyazaki K. 2003. Creating random mutagenesis libraries by megaprimer PCR of whole plasmid (MEGAWHOP). Methods Mol. Biol. 231:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jia W, El Zoeiby A, Petruzziello TN, Jayabalasingham B, Seyedirashti S, Bishop RE. 2004. Lipid trafficking controls endotoxin acylation in outer membranes of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 279:44966–44975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ruiz N, Falcone B, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2005. Chemical conditionality: a genetic strategy to probe organelle assembly. Cell 121:307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ruiz N, Gronenberg LS, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2008. Identification of two inner-membrane proteins required for the transport of lipopolysaccharide to the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:5537–5542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fekkes P, van der Does C, Driessen AJ. 1997. The molecular chaperone SecB is released from the carboxy-terminus of SecA during initiation of precursor protein translocation. EMBO J. 16:6105–6113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Driessen AJM, Nouwen N. 2008. Protein translocation across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77:643–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hartl FU, Lecker S, Schiebel E, Hendrick JP, Wickner W. 1990. The binding cascade of SecB to SecA to SecY/E mediates preprotein targeting to the E. coli plasma membrane. Cell 63:269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumamoto CA. 1989. Escherichia coli SecB protein associates with exported protein precursors in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5320–5324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Altman E, Bankaitis VA, Emr SD. 1990. Characterization of a region in mature LamB protein that interacts with a component of the export machinery of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 265:18148–18153 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Collier DN, Bankaitis VA, Weiss JB, Bassford PJ. 1988. The antifolding activity of SecB promotes the export of the E. coli maltose-binding protein. Cell 53:273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fekkes P, Driessen AJ. 1999. Protein targeting to the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:161–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee HC, Bernstein HD. 2001. The targeting pathway of Escherichia coli presecretory and integral membrane proteins is specified by the hydrophobicity of the targeting signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:3471–3476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bowers CW, Lau F, Silhavy TJ. 2003. Secretion of LamB-LacZ by the signal recognition particle pathway of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:5697–5705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Steiner D, Forrer P, Stumpp MT, Plückthun A. 2006. Signal sequences directing cotranslational translocation expand the range of proteins amenable to phage display. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:823–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.