Abstract

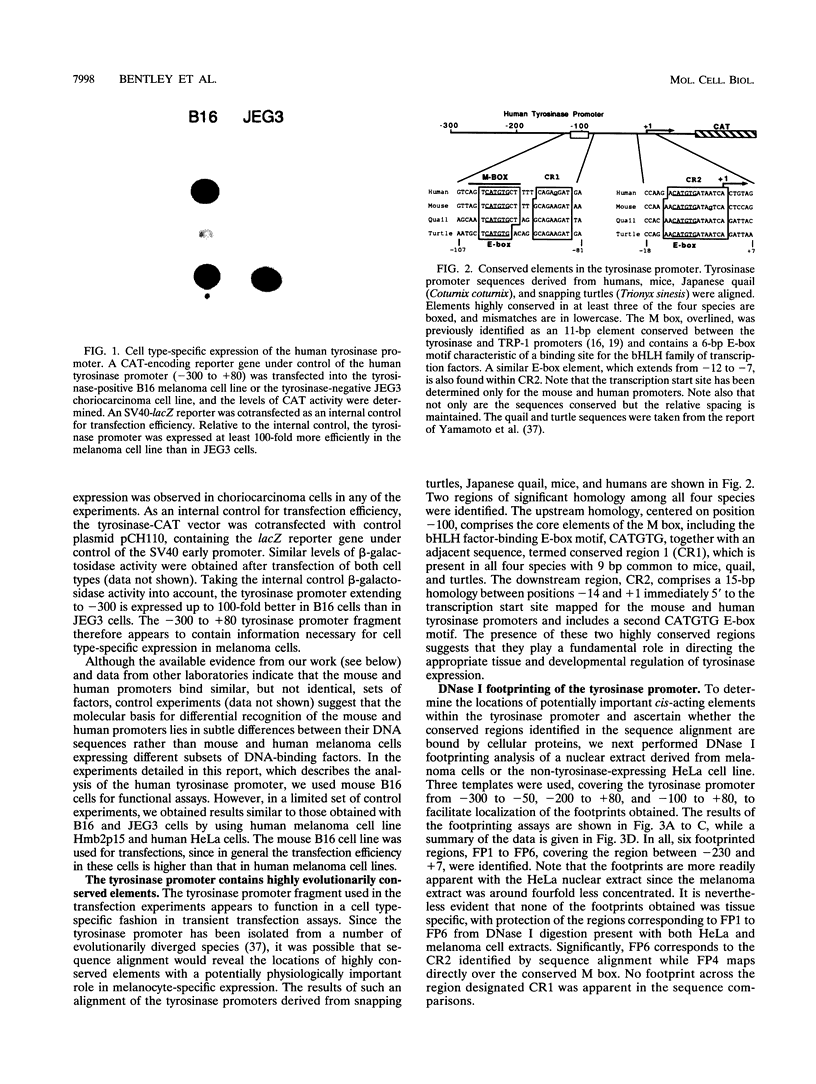

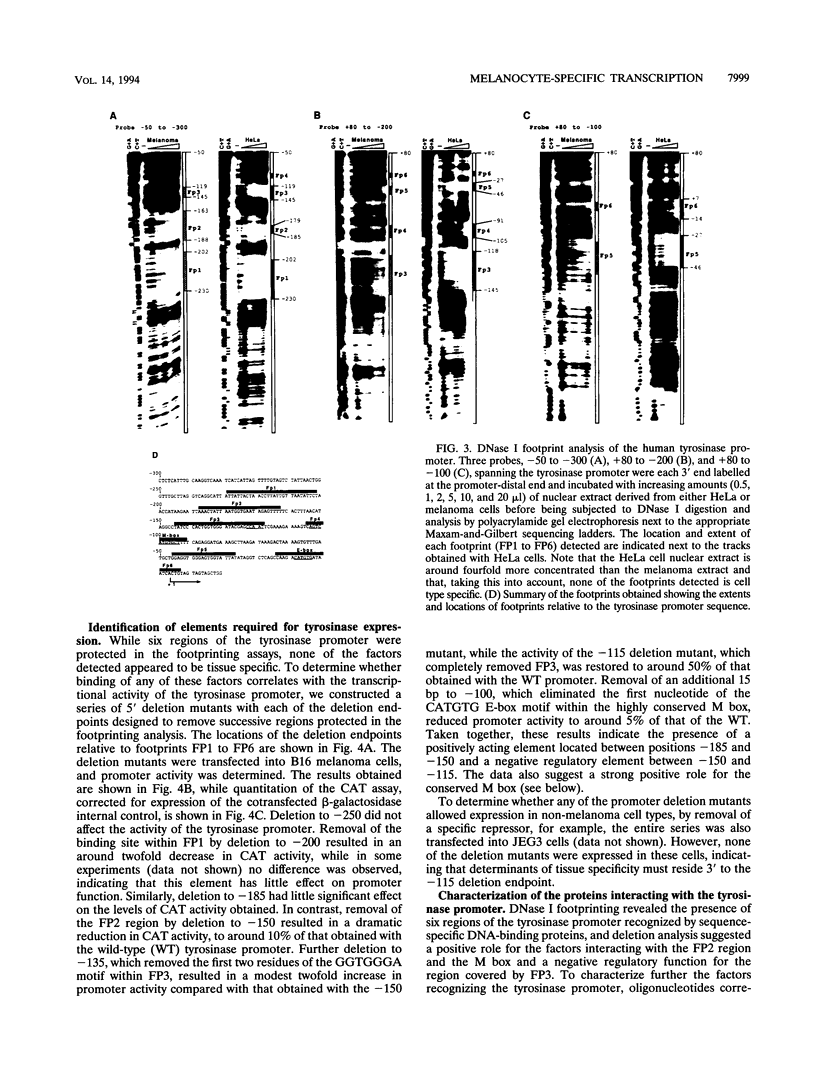

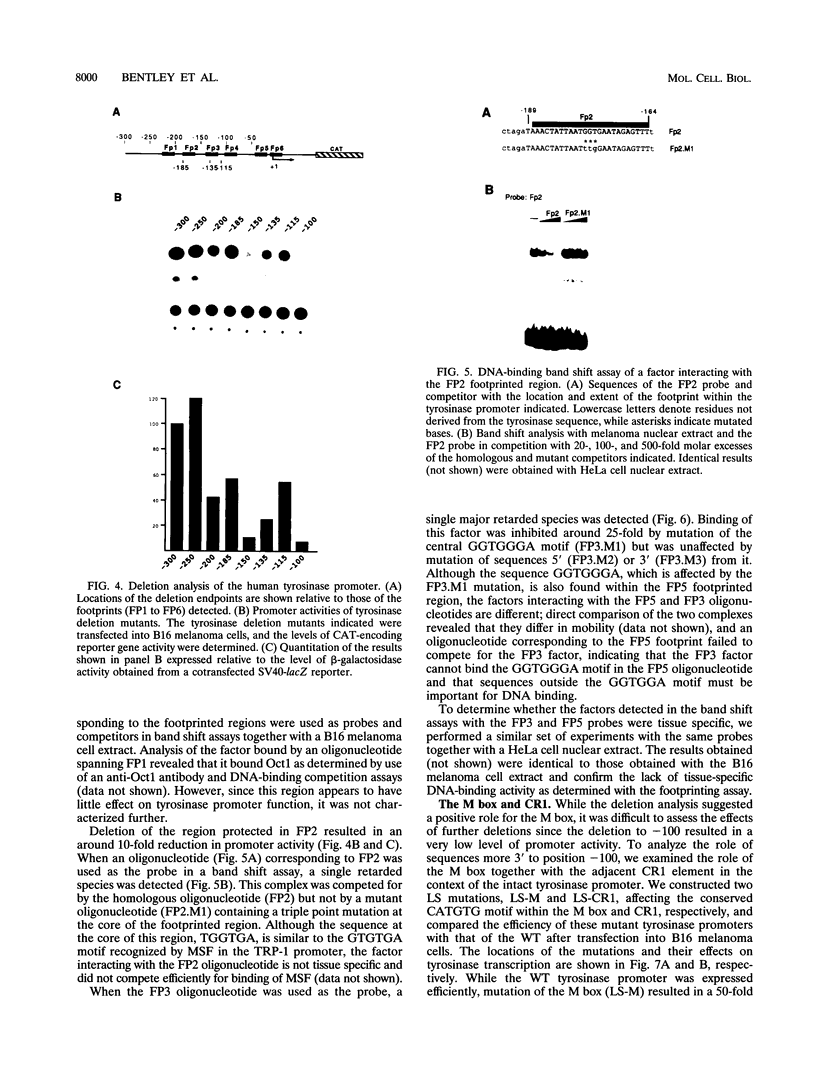

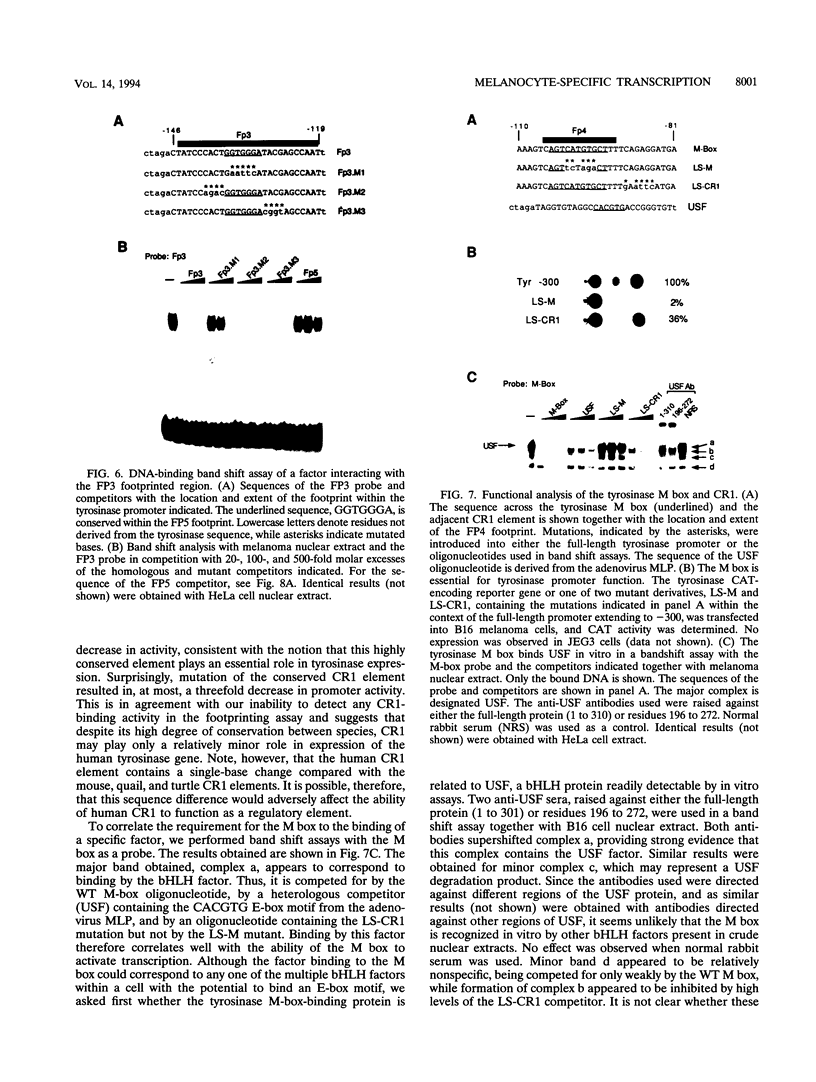

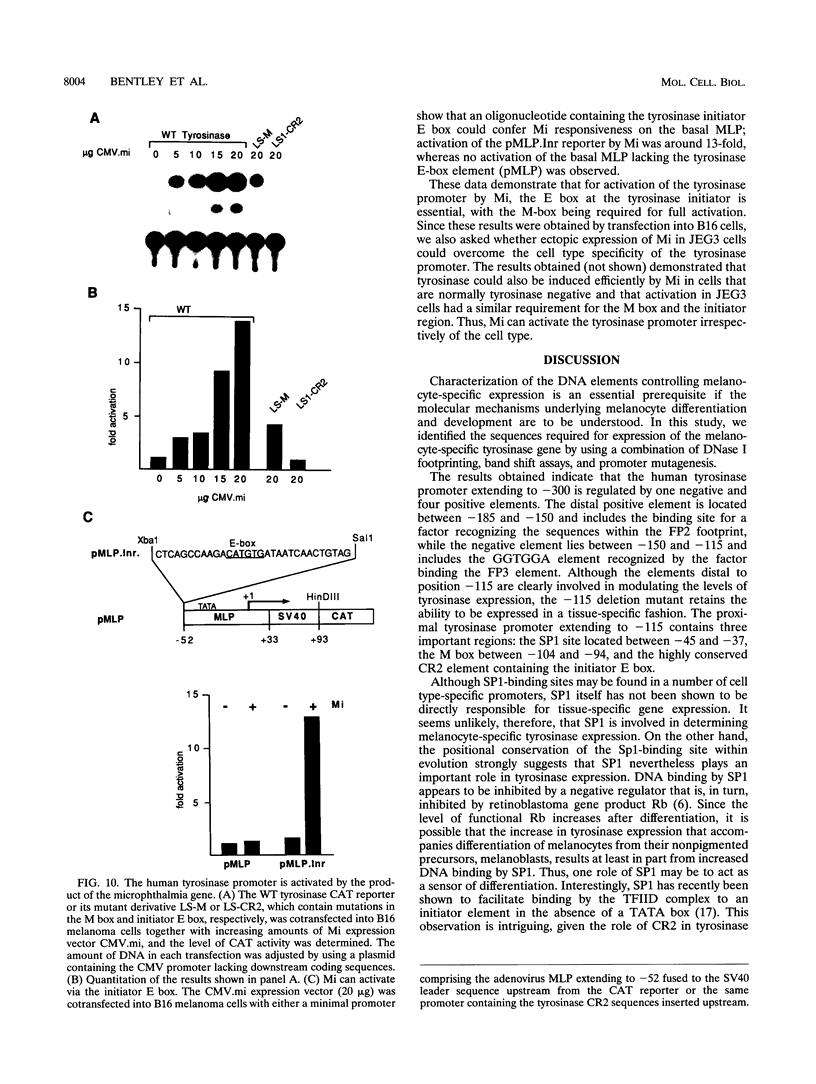

The tyrosinase gene is expressed specifically in melanocytes and the cells of the retinal pigment epithelium, which together are responsible for skin, hair, and eye color. By using a combination of DNase I footprinting and band shift assays coupled with mutagenesis of specific DNA elements, we examined the requirements for melanocyte-specific expression of the human tyrosinase promoter. We found that as little as 115 bp of the upstream sequence was sufficient to direct tissue-specific expression. This 115-bp stretch contains three positive elements: the M box, a conserved element found in other melanocyte-specific promoters; an Sp1 site; and a highly evolutionarily conserved element located between -14 and +1 comprising an E-box motif and an overlapping octamer element. In addition, two further elements, one positive and one negative, are located between positions -185 and -150 and positions -150 and -115, respectively. We also found that the basic helix-loop-helix factor encoded by the microphthalmia gene, which is essential for melanocyte differentiation, can transactivate the tyrosinase promoter via the M box and the conserved E box located close to the initiator. Since in vitro assays failed to identify any melanocyte-specific DNA-binding activity, the possibility that the specific arrangement of elements within the basal tyrosinase promoter determines melanocyte-specific expression is discussed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bennett D. C. Mechanisms of differentiation in melanoma cells and melanocytes. Environ Health Perspect. 1989 Mar;80:49–59. doi: 10.1289/ehp.898049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T., Bober E., Arnold H. H. Inhibition of muscle differentiation by the adenovirus E1a protein: repression of the transcriptional activating function of the HLH protein Myf-5. Genes Dev. 1992 May;6(5):888–902. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcamo J., Maldonado E., Cortes P., Ahn M. H., Ha I., Kasai Y., Flint J., Reinberg D. A TATA-like sequence located downstream of the transcription initiation site is required for expression of an RNA polymerase II transcribed gene. Genes Dev. 1990 Sep;4(9):1611–1622. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso M., Martelli F., Giordano A., Felsani A. Regulation of MyoD gene transcription and protein function by the transforming domains of the adenovirus E1A oncoprotein. Oncogene. 1993 Feb;8(2):267–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Aug;7(8):2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. I., Nishinaka T., Kwan K., Kitabayashi I., Yokoyama K., Fu Y. H., Grünwald S., Chiu R. The retinoblastoma gene product RB stimulates Sp1-mediated transcription by liberating Sp1 from a negative regulator. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Jul;14(7):4380–4389. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam J. D., Martin P. L., Shastry B. S., Roeder R. G. Eukaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:582–598. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson D. G., Olson E. N. Helix-loop-helix proteins as regulators of muscle-specific transcription. J Biol Chem. 1993 Jan 15;268(2):755–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goding C. R., Temperley S. M., Fisher F. Multiple transcription factors interact with the adenovirus-2 EII-late promoter: evidence for a novel CCAAT recognition factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Oct 12;15(19):7761–7780. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.19.7761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman C. M., Moffat L. F., Howard B. H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Sep;2(9):1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing V. J., Jiménez M. Mammalian tyrosinase--the critical regulatory control point in melanocyte pigmentation. Int J Biochem. 1987;19(12):1141–1147. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(87)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hen R., Sassone-Corsi P., Corden J., Gaub M. P., Chambon P. Sequences upstream from the T-A-T-A box are required in vivo and in vitro for efficient transcription from the adenovirus serotype 2 major late promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Dec;79(23):7132–7136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson C. A., Moore K. J., Nakayama A., Steingrímsson E., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Arnheiter H. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell. 1993 Jul 30;74(2):395–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90429-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson I. J., Bennett D. C. Identification of the albino mutation of mouse tyrosinase by analysis of an in vitro revertant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(18):7010–7014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson I. J., Chambers D. M., Budd P. S., Johnson R. The tyrosinase-related protein-1 gene has a structure and promoter sequence very different from tyrosinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991 Jul 25;19(14):3799–3804. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann J., Smale S. T. Direct recognition of initiator elements by a component of the transcription factor IID complex. Genes Dev. 1994 Apr 1;8(7):821–829. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klüppel M., Beermann F., Ruppert S., Schmid E., Hummler E., Schütz G. The mouse tyrosinase promoter is sufficient for expression in melanocytes and in the pigmented epithelium of the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 May 1;88(9):3777–3781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowings P., Yavuzer U., Goding C. R. Positive and negative elements regulate a melanocyte-specific promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Aug;12(8):3653–3662. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick A., Brady H., Fukushima J., Karin M. The pituitary-specific regulatory gene GHF1 contains a minimal cell type-specific promoter centered around its TATA box. Genes Dev. 1991 Aug;5(8):1490–1503. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misseyanni A., Klug J., Suske G., Beato M. Novel upstream elements and the TATA-box region mediate preferential transcription from the uteroglobin promoter in endometrial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991 Jun 11;19(11):2849–2859. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.11.2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. J., Tjian R. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science. 1989 Jul 28;245(4916):371–378. doi: 10.1126/science.2667136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mymryk J. S., Lee R. W., Bayley S. T. Ability of adenovirus 5 E1A proteins to suppress differentiation of BC3H1 myoblasts correlates with their binding to a 300 kDa cellular protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1992 Oct;3(10):1107–1115. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare P., Goding C. R. Herpes simplex virus regulatory elements and the immunoglobulin octamer domain bind a common factor and are both targets for virion transactivation. Cell. 1988 Feb 12;52(3):435–445. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder R. G. The complexities of eukaryotic transcription initiation: regulation of preinitiation complex assembly. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991 Nov;16(11):402–408. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90164-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. L., Malik S., Meisterernst M., Roeder R. G. An alternative pathway for transcription initiation involving TFII-I. Nature. 1993 Sep 23;365(6444):355–359. doi: 10.1038/365355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. L., Meisterernst M., Pognonec P., Roeder R. G. Cooperative interaction of an initiator-binding transcription initiation factor and the helix-loop-helix activator USF. Nature. 1991 Nov 21;354(6350):245–248. doi: 10.1038/354245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto E., Shi Y., Shenk T. YY1 is an initiator sequence-binding protein that directs and activates transcription in vitro. Nature. 1991 Nov 21;354(6350):241–245. doi: 10.1038/354241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara S., Okinaga S., Tomita Y., Takeda A., Yamamoto H., Sato M., Takeuchi T. A point mutation in the tyrosinase gene of BALB/c albino mouse causing the cysteine----serine substitution at position 85. Eur J Biochem. 1990 Apr 30;189(2):455–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata K., Muraosa Y., Tomita Y., Tagami H., Shibahara S. Identification of a cis-acting element that enhances the pigment cell-specific expression of the human tyrosinase gene. J Biol Chem. 1992 Oct 15;267(29):20584–20588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale S. T., Baltimore D. The "initiator" as a transcription control element. Cell. 1989 Apr 7;57(1):103–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster K. A., Muscat G. E., Kedes L. Adenovirus E1A products suppress myogenic differentiation and inhibit transcription from muscle-specific promoters. Nature. 1988 Apr 7;332(6164):553–557. doi: 10.1038/332553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wefald F. C., Devlin B. H., Williams R. S. Functional heterogeneity of mammalian TATA-box sequences revealed by interaction with a cell-specific enhancer. Nature. 1990 Mar 15;344(6263):260–262. doi: 10.1038/344260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H., Kudo T., Masuko N., Miura H., Sato S., Tanaka M., Tanaka S., Takeuchi S., Shibahara S., Takeuchi T. Phylogeny of regulatory regions of vertebrate tyrosinase genes. Pigment Cell Res. 1992 Nov;5(5 Pt 2):284–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1992.tb00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavuzer U., Goding C. R. Melanocyte-specific gene expression: role of repression and identification of a melanocyte-specific factor, MSF. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 May;14(5):3494–3503. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama T., Silversides D. W., Waymire K. G., Kwon B. S., Takeuchi T., Overbeek P. A. Conserved cysteine to serine mutation in tyrosinase is responsible for the classical albino mutation in laboratory mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Dec 25;18(24):7293–7298. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenzie-Gregory B., O'Shea-Greenfield A., Smale S. T. Similar mechanisms for transcription initiation mediated through a TATA box or an initiator element. J Biol Chem. 1992 Feb 5;267(4):2823–2830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]