Abstract

Pheromones are central to the mating systems of a wide range of organisms, and reproductive isolation between closely related species is often achieved by subtle differences in pheromone composition. In insects and moths in particular, the use of structurally similar components in different blend ratios is usually sufficient to impede gene flow between taxa. To date, the genetic changes associated with variation and divergence in pheromone signals remain largely unknown. Using the emerging model system Ostrinia, we show the functional consequences of mutations in the protein-coding region of the pheromone biosynthetic fatty-acyl reductase gene pgFAR. Heterologous expression confirmed that pgFAR orthologs encode enzymes exhibiting different substrate specificities that are the direct consequences of extensive nonsynonymous substitutions. When taking natural ratios of pheromone precursors into account, our data reveal that pgFAR substrate preference provides a good explanation of how species-specific ratios of pheromone components are obtained among Ostrinia species. Moreover, our data indicate that positive selection may have promoted the observed accumulation of nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments substantiate the idea that amino acid polymorphisms underlie subtle or drastic changes in pgFAR substrate preference. Altogether, this study identifies the reduction step as a potential source of variation in pheromone signals in the moth genus Ostrinia and suggests that selection acting on particular mutations provides a mechanism allowing pheromone reductases to evolve new functional properties that may contribute to variation in the composition of pheromone signals.

Keywords: chemical communication, Lepidoptera, speciation, genetics

Chemical signals such as pheromones play a central role in mediating the reproductive behavior of many animals (1). Also, population divergence often involves changes in the sex pheromone signals and/or their perception that cause modification of the associated behaviors and, subsequently, prezygotic reproductive isolation (1–3). Although some progress has been made in identifying the genetic architecture underlying pheromone communication systems (3, 4), the molecular bases of intraspecific variation or transitions in pheromone systems remain poorly documented. To unravel general patterns concerning the cause of divergence (5), it is fundamental to move beyond studies of individual species. Indeed, studies on intra- and interspecific differences among isolated taxa have the potential to reveal the causes of signal divergence that are associated with reproductive isolation (3).

In this context, moths (Insecta: Lepidoptera), which represent one of the largest group of insects with ∼160,000 described species (6), provide highly relevant examples because subtle changes in their sex pheromone composition are often the initial trigger for population divergence and can lead to speciation (7, 8). Typically, female moths emit a sex pheromone that attracts males over long distances. Moth sex pheromones usually consist of a bouquet of structurally similar chemical components, and species specificity is in many cases achieved by the use of a narrow range of pheromone components combined in a specific ratio (1, 7, 8). The moth genus Ostrinia is an emerging model system ideal for addressing questions on the genetic bases of pheromone evolution and identifying genes that shape pheromone signals (9–12). The Ostrinia female sex pheromones are typically blends of monounsaturated tetradecenyl (C14) acetates that vary in double bond position (∆9, ∆11, or ∆12) and geometry [cis (Z) or trans (E); Fig. 1]. Like in many moths, specificity of the signals results from the makeup and proportion of pheromone components. A number of field and flight tunnel studies conducted using the European and Asian corn borer O. nubilalis and O. furnacalis, respectively, have demonstrated that males respond to a narrow range of pheromone ratios and that small changes in the pheromone ratio have a clear behavioral impact (13–16). The Ostrinia system has received much attention because of naturally occurring pheromone polymorphisms and the relatively simple nature of the pheromone components. These features have made the system amenable to reductionist approaches, although it has turned out to be surprisingly complex.

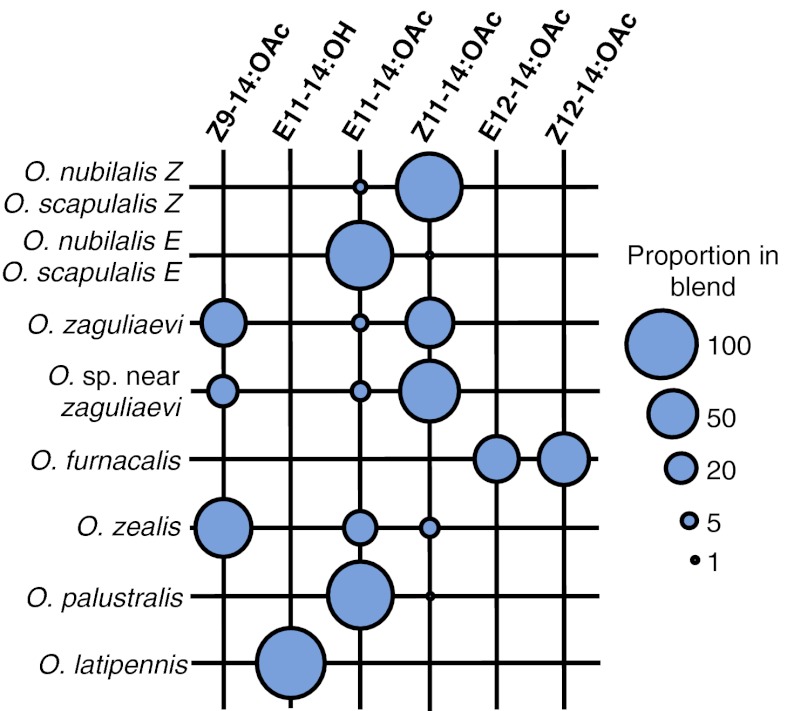

Fig. 1.

Composition of female sex pheromones of Ostrinia moths. The size of a dot is proportional to the ratio of an individual pheromone component. Based on data reported elsewhere (14, 38, 48–50) and references therein.

In Ostrinia, all of the pheromone precursors are synthesized de novo from palmitic acid (C16) through a few enzymatic steps including desaturation and chain-shortening (Fig. 2). Acyl precursors are subsequently converted into fatty alcohols, usually followed by acetylation to produce the acetate esters used as pheromone components. Earlier in vivo experiments demonstrated that the acetyltransferase, which is involved in the last step of the biosynthesis pathways leading to acetate pheromone components, has low substrate specificity in Ostrinia species (17–19). These results imply that pheromone blend ratio regulation occurs before the acetylation step. Previously, the intraspecific differences in pheromone blend ratio causing reproductive isolation between the diverging pheromone races of the European corn borer O. nubilalis were shown to result from mutations in the pheromone gland–specific fatty-acyl reductase gene pgFAR, which encodes the reductase catalyzing the specific reduction of the fatty-acyl pheromone precursors into fatty alcohols (10). To assess whether variation in the pgFAR gene parallels interspecific differences in pheromone phenotypes across the genus, we cloned and functionally characterized the orthologs of O. nubilalis pgFAR from six additional Ostrinia congeners. Here our results establish that the pgFARs exhibit different substrate specificities that are the consequence of variation in the protein-coding regions of the pgFAR orthologs. Moreover, we show that pgFAR substrate preference has to be taken into account to explain the final ratios of the pheromone components. Finally, the results from site-directed mutagenesis experiments substantiate the idea that nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions can underlie subtle or drastic changes in pgFAR substrate preference that have the potential to impact the ratio of components found in the female sex pheromone.

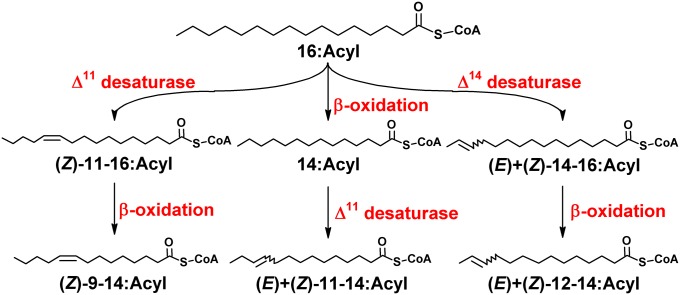

Fig. 2.

Pathways toward pheromone precursors in Ostrinia moths. De novo biosynthesis of all precursors starts from palmitoyl-CoA (16:Acyl). A ∆11 desaturase catalyzes the production of (Z)-11-hexedecenoyl [(Z)-11–16:Acyl], which undergoes one cycle of β-oxidation to give (Z)-9-tetradecenoyl [(Z)-9–14:Acyl] (9, 51). The same ∆11 desaturase acts on myristoyl-CoA (14:Acyl) to produce (E)- and (Z)-11-tetradecenoyl [(E)+(Z)-11–14:Acyl] (9, 52). In O. latipennis, a different ∆11 desaturase uniquely catalyzes the stereo-specific production of (E)-11-tetradecenoyl [(E)-11–14:Acyl] (11). Finally, in O. furnacalis, (E)- and (Z)-12-tetradecenoyl [(E)+(Z)-12–14:Acyl] moieties are produced through chain-shortening of (E)- and (Z)-14-hexedecenoyl [(E)+(Z)-14–16:Acyl], respectively, the production of which is catalyzed by a ∆14 desaturase (9, 32).

Results

Functional Characterization of Ostrinia pgFARs.

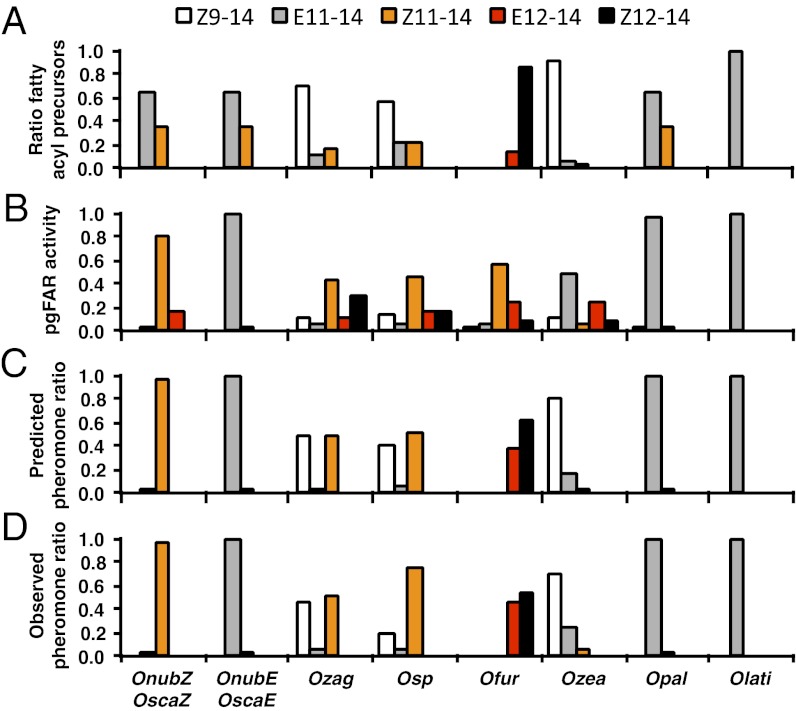

Coding sequences of the pgFAR orthologs showed on average 4.6% nucleotide divergence (0.4–8.4%) and 8.1% amino acid divergence (0.4–13.8%; Fig. S1; Table S1). These data show that there are extensive nonsynonymous substitutions compared with synonymous ones and, consequently, extensive amino acid variation in pgFARs, which may have functional consequences. In addition, the ratios of acyl precursors and pheromone components exhibit great disparities in most Ostrinia species (Fig. 3 A and D), which strongly suggests that the pgFAR orthologs encode reductases with different catalytic properties contributing to determine the final ratio used by a given species. To assess the effect of the observed amino acid differences on the reductase substrate specificity, we expressed the different pgFARs in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisae) while supplementing the growth medium with the ∆9-, ∆11-, or ∆12-tetradecenoyl pheromone precursors. In a first set of experiments, the precursors were added individually, and their conversion into fatty alcohols was monitored by GC-MS analysis. The pgFAR orthologs conferred on the yeast the ability to convert acyl precursors into fatty alcohols, and more importantly, the enzymes varied in their ability to convert the different precursors (Fig. 3B). Based on the relative conversion efficiency of each precursor into the corresponding alcohol, we inferred the ratios of pheromone components that would result from combining the relative abundance of precursors and the affinity of pgFARs. Hence, the ratios of pheromone components predicted matched closely with the actual pheromone blend phenotypes produced by in Ostrinia female moths (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

Activity of pgFARs in vitro compared with pheromone composition. (A) Schematic view of the relative abundance of acyl precursors in the female pheromone gland of Ostrinia species. (B) Relative abundance of the fatty alcohols accumulating in yeast expressing different pgFARs supplemented with methyl-ester precursors, one at a time (0.5 mM). (C) Predicted ratio of pheromone components calculated based on the relative abundance of precursors and the corresponding affinity of pgFARs. (D) Pheromone components and their ratio as reported previously (Fig. 1).

In a second set of experiments, we supplemented the yeast growth medium with ratios of acyl precursors as observed in the Ostrinia female pheromone glands from which the pgFARs had been isolated. As anticipated, the final ratio of fatty alcohols produced by each pgFAR corresponded perfectly to the ratio of pheromone components found in insecta (Fig. 4).

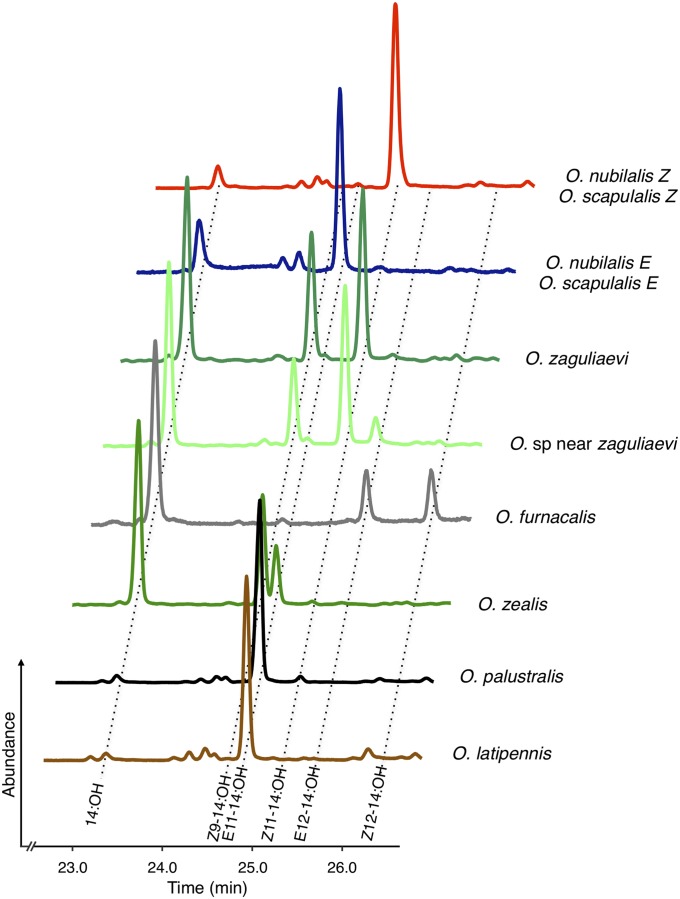

Fig. 4.

Alcohol production of yeast expressing Ostrinia pgFARs when supplemented with pheromone precursors at natural ratios. The traces represent portions of the total ion chromatogram of extracts made from yeast grown in the presence of all methyl esters precursors (0.5 mM in total). The ratios of precursors supplemented correspond to the relative abundance of each fatty-acyl precursor naturally occurring in the pheromone gland (Fig. 3A).

pgFAR Polymorphisms and Tests of Selection.

Our data show that there is extensive amino acid variation in pgFAR, raising the possibility that positive selection may have influenced the evolutionary trajectory of this gene. We investigated this in two complementary approaches: phylogenetic reconstruction and comparative analysis of the sequence data.

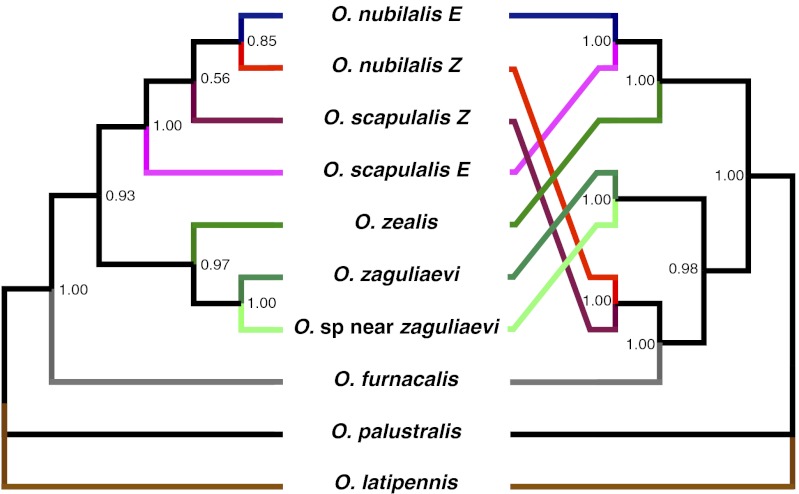

First, we examined the correspondence between the species phylogeny and the gene genealogy obtained with pgFAR. We obtained sequence information for five informative gene regions that have been successfully used to elucidate phylogenetic relationships among lepidopterans (20, 21), namely elongation factor-1α (EF-1α), malate dehydrogenase (MDH), isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), and ribosomal protein S5 (RpS5) from the nuclear genome and cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) from the mitochondrial genome. Our molecular phylogenetic reconstruction is based on the combined nucleotide sequence dataset for these genetic markers totaling 4,804 bp. Interestingly, our phylogenetic analyses reveal a strong discordance between the pgFAR gene tree and the species tree (Fig. 5). The two trees have an overall topological similarity of 59.9%, and close examination of the trees reveals a shift of topological position across numerous sequences, which may have been caused by selection. One may speculate that the topology of the pgFAR gene tree depicts in part the functional relatedness between encoded enzymes rather than ancestry alone.

Fig. 5.

Discordance between the phylogenetic trees of Ostrinia species and pgFAR orthologs. The Bayesian phylogenetic species tree (Left) was established based on five markers (COI, EF-1α, MDH, IDH, and RpS5) that are informative in the context of Lepidoptera phylogenetics (21), whereas the pgFAR tree (Right) was built using the coding region of the gene. Both nucleotide and amino acid datasets produced the same topology. Numbers correspond to Bayesian posterior probabilities.

All proteins experience purifying selection due to the need to maintain structural and functional integrity, which narrows the range of possible amino acid substitutions, and the coding region of a gene is not uniform regarding the threshold of change acceptability (22). Consequently, positive selection may operate only on a subset of sites, with a large majority of codons experiencing purifying selection. We used a sliding-window analysis to uncover the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions (Ka/Ks) along the pgFAR protein sequence and detect regions of the protein that may have experienced positive selection. The analysis revealed that several regions in the protein exhibit a Ka/Ks ratio >1 (Fig. S2). Most of these regions are in the C-terminal part of the protein, which comprises the more variable Sterile pfam domain. The N-terminal region of FARs, which contains a Rossmann fold–like NADPH-binding pfam domain, harbors several regions that are highly conserved throughout the eukaryotes. To identify which sites may have experienced positive selection, we next inferred selection on individual amino acids using different detection tools. Results from the different evolutionary models supported the action of positive selection, and, of 465 codons, site-specific analyses showed strong evidence for positive selection at a total of 45 sites, 24 of which were supported by the three methods used (Fig. S3; Table S2 and S3). Again, the C-terminal region contained a greater proportion of sites predicted to be under selection. Among the selected codons, 7 were associated with transitions in the charge of the encoded amino acid, 11 were associated with changes in the hydrophobicity profile, and 5 corresponded to changes in both charge and hydrophobicity at the particular site (Fig. S3). These predicted sites may mediate the biochemical specificity of the encoded enzyme and participate in enzyme-ligand interactions.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of O. furnacalis pgFAR.

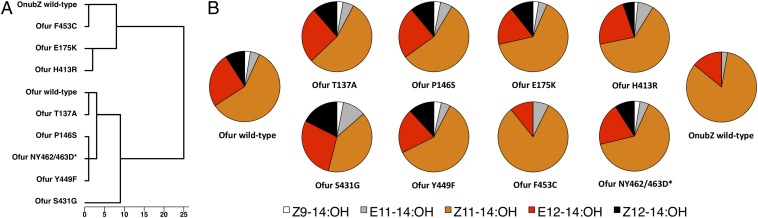

The tertiary structure of fatty-acyl reductases cannot be modeled with accuracy, and structure–function relationships cannot be predicted either. Experimental approaches using methods such as site-specific mutagenesis can assist in teasing out the role of individual sites within a protein. Here we conducted mutagenesis experiments on two pgFAR orthologs displaying different substrate preferences while having the highest degree of sequence identity at the amino acid level: Ofurnacalis-pgFAR and OnubilalisZ-pgFAR. Both enzymes exhibit a strong substrate preference for Z11-14 acyl but differ in their biochemical properties: OnubilalisZ-pgFAR is unable to reduce the Z9-14 and Z12-14 acyl precursors that Ofurnacalis-pgFAR readily converts into the corresponding alcohols. The two enzymes also differ in the absolute amounts of primary fatty alcohols produced in our in vitro assay (Fig. S4). The two encoded proteins differ at 16 positions mainly found in the C-terminal region, 13 of which corresponded to sites predicted to have potentially experienced diversifying selection (Fig. S3). Five of these sites involving conservative substitutions (e.g., valine-leucine, isoleucine-leucine) were excluded a priori because they were unlikely to cause a change in function or structure (23). We mutated the remaining eight sites in Ofurnacalis-pgFAR individually to the corresponding OnubilalisZ-pgFAR residue in a loss-of-function approach. Using this strategy, we identified mutation F453C as affecting the enzyme’s affinity for the Z9-14 and Z12-14 acyl precursors (Fig. 6). The Ofurnacalis-pgFARF453C mutant exhibited a substrate preference remarkably similar to WT OnubilalisZ-pgFAR. Conversely, the chimeric enzyme with the reverse mutation C453F in OnubilalisZ-pgFAR had a substrate specificity highly similar to that of WT Ofurnacalis-pgFAR (Fig. 7). Two mutations, T137A and P146S, did not lead to any significant modification of the blend. Three of the other mutations, S431G, Y449F, and NY462/463D*, caused more minor modifications of enzymatic activity, resulting in the alteration of the relative ratios of the resulting alcohols (Fig. 6; Fig. S4). The substitutions E175K and H413R led to an overall decrease in alcohol production (approximately fourfold), without affecting the relative ratios of the alcohols (Fig. 6; Fig. S4). Subsequently, we produced double mutants by introducing each mutation individually in the Ofurnacalis-pgFARF453C background. Our results confirmed that these other mutations have the potential to modify the enzymatic activity and alter alcohol ratios (Fig. S5). For example, the introduction of S431G in either the Ofurnacalis-pgFARWT or Ofurnacalis-pgFARF453C background resulted in an increased proportion of E12-14:OH in the blend. Interestingly, a mutant carrying all five mutations T137A, P146S, S431G, Y449F, and NY462/463D* in an Ofurnacalis-pgFAR background was still capable of reducing the Z9-14 and Z12-14 acyl precursors, indicating that the F453C mutation is essential to generate the shift in substrate preference.

Fig. 6.

Functional expression assays of parental and single-codon mutant pgFARs. (A) Hierarchical cluster dendrogram (Ward’s grouping method, Euclidean distances) showing distances among the eight mutants and the WT pgFAR from O. furnacalis (parental background) and O. nubilalis Z. (B) Ratios of fatty-alcohol products for WT and mutant pgFARs.

Fig. 7.

Functional impact of the reverse mutation C453F on OnubilalisZ-pgFAR activity compared with the Ofurnacalis WT. The pie charts and graphs represents the relative and absolute abundances of alcohols, respectively (n = 4).

Discussion

Sex pheromones are one of the main features that define biological species within Lepidoptera (8, 24). After 50 y of research in this field, it is clear that the use of a narrow range of blend ratios is one of the hallmarks defining the species specificity of moth pheromones (3, 8). The diversity of signals has its roots in the biochemical pathways that take place in the female pheromone gland, involving key enzymatic steps (25, 26). Although the sex pheromones of hundreds of lepidopteran species have been identified to date (27), our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underpinning variation and evolution within pheromone communication systems remains limited. To further address these questions, we investigated the molecular and biochemical differences in a fatty-acyl reductase gene involved in pheromone biosynthesis within the moth genus Ostrinia, revealing the functional consequences of coding variation in the pgFAR gene and showing how it correlates with observed differences in pheromone composition among congeners. Our data illustrate how reductases may evolve new functional properties as a consequence of accumulating nonsynonymous amino acid changes.

The composition of available acyl precursors may differ from species to species, which in itself contributes to variation in blend composition (26). Indeed, differential regulation of desaturase genes has been shown to be associated with evolutionary transitions in the pheromone communication systems of flies and moths including in Ostrinia (9, 11, 28–31). However, in most Ostrinia species, the precursor and pheromone component ratios exhibit significant disparities, and the pgFAR substrate preference is in many cases necessary to explain how the final blend ratios are obtained. Our results show that structural mutations in pgFAR can alter the specificity for the location and isomeric nature of double bonds in the desaturated precursors, which has the potential to modify the isomeric composition of sex pheromone blends. In Ostrinia, pgFARs act in concert with other biosynthetic enzymes and catalyze an enzymatic step that shapes the final pheromone blend ratio, thus contributing to determine species-specific ratios, an essential feature of the pheromone signals. Taken together, our data support that coding variation in pgFAR may influence how pheromone blends evolve and thereby contribute to the specificity of the Ostrinia mating systems.

Some pgFARs have the ability to convert in vitro precursors that are not naturally present in the species from which the gene originated. Similar observations have been reported when the reductase system of O. nubilalis and O. furnacalis were studied in vivo using deuterium-labeled precursors (18, 19), substantiating the idea that these are not artifacts of the yeast system. We interpret these enzymatic properties as both ghosts from the evolutionary past of the species, i.e., the remains of ancestral features, as well as evidence for intrinsic preadaptations. Such preadaptations of the reductase system were necessary to allow the evolution of O. furnacalis, which uniquely possesses ∆12-tetradecenyl precursors as a consequence of the activity of a ∆14 desaturase (9, 32). Interestingly, although distantly related to Ostrinia, the pgFAR active in small ermine moths of the genus Yponomeuta (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) also has the ability to reduce ∆12-tetradecenyl precursors (33). In addition, our data exemplify that different substitutions can produce similar functional effects, which may result from convergent evolution. Hence, OnubilalisE-pgFAR and Opalustralis-pgFAR have the same substrate preference and produce an identical ratio of alcohols despite showing 12.3% divergence in their amino acid sequences. In contrast, OnubilalisZ-pgFAR and Ofurnacalis-pgFAR show 96.1% identity at the amino acid level (98.2% at the nucleotide level). Although both enzymes exhibit a strong substrate preference for Z11-14 acyl, they differ in their biochemical properties. This result points to the necessity of performing tests of gene function, as computational analyses of sequence similarity alone may be misleading. We engineered chimeric pgFAR mutants to begin to disentangle sequence–structure–function relationships. Our mutagenesis data show that a single nucleotide mutation in the C-terminal region can determine the ability to catalyze the reduction of Z9-14 and Z12-14 acyl precursors. It is worth noting that, although remarkable in itself, the change in activity conveyed by the Ofurnacalis-pgFARF453C mutation is close but not identical to OnubilalisZ-pgFAR. Indeed, the fine-tuning of the reduction step and the precise OnubilalisZ ratio is likely the consequence of the subtle additive effects of additional mutations.

In conclusion, because mutations at the pgFAR locus have the potential to modify the proportion of individual pheromone components, our study identifies the enzymatic step catalyzed by pgFAR as a candidate source of variation in moth pheromone signals. Variation is necessary to provide the conditions for divergence in pheromone signals. It has been suggested earlier that natural selection on mate recognition may be a major component of the evolution of the mate recognition system of many taxa (34, 35). In moths, selection acting on the female pheromone signals is both direct and indirect as a consequence of the selection operating on males that are attracted to the female-produced pheromone blend (36). Because of the important role played by pgFAR in shaping the pheromone signal emitted by females, selection would have acted to maintain and enhance the fixation probability of those mutations, leading to new phenotypes whenever conferring a slight selective advantage. Hence, male moths may prefer a deviant pheromone ratio if it promotes privacy of the communication channel and limits interference with other species, which may in turn increase their fitness (36, 37). Chemical messages to recruit potential mates can act as a strong impediment to gene flow with inappropriate mates, and divergence in chemical signals is often an essential step in divergence between populations that may or may not lead to speciation. Whether a new signal will emerge depends on the ability of receivers to respond to it and the adaptive advantages inherent in the use of the new signal. Variation in the pheromone signal must therefore be paralleled by variation in male reception, as exemplified by the potential role played by a shift in pheromone receptor sensitivity in the evolution of O. furnacalis (12). Functional and comparative genomic studies of male olfactory receptor genes and genes defining the architecture of neurophysiological pathways will help us to better infer the evolutionary processes that have shaped pheromone communication systems and signal response coevolution.

Materials and Methods

Amplification of pgFAR Transcripts.

We sampled and pooled per species 10–20 pheromone glands of 0- to 3-d-old virgin females of the Far Eastern knotweed borer O. latipennis, the dock borer O. palustralis, the adzuki bean borer O. scapulalis (E and Z pheromone strains), the butterbur borer O. zaguliaevi, the leopard plant borer O. sp. near zaguliaevi [a new member of Ostrinia for which the taxonomic status remains to be determined (38)], and the burdock borer O. zealis, all of which were collected in Japan. Females of the Asian corn borer O. furnacalis originated from a Chinese laboratory strain, whereas females of both pheromone strains of the European corn borer O. nubilalis were from France. We extracted total RNA using the RNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen) and synthesized first-strand cDNA using Stratascript reverse transcriptase (Stratagene). An ∼290-bp fragment was amplified using pgFAR_F and pgFAR_R primers as previously described (10, 39). Gene-specific primers were designed and used in PCRs to amplify the 5′ and 3′ cDNA ends with the SMART RACE amplification kit (Clontech) following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were gel-purified and ligated into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) or the PCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen). Ligation products were used to transform Escherichia coli TOPO10 chemically competent cells (Invitrogen). Plasmids were purified and served as templates for sequencing reactions with the BigDye terminator kit v1.1 (Applied Biosystems) followed by analysis on a ABI PRISM 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Primer walking sequencing was carried out to obtain information from long amplification products. Full-length sequences were compiled using the sequence information from the 5′ and 3′ RACE PCR products. Data were analyzed using Bioedit version 7 (40).

Phylogenetic Analysis.

The sequence data used to build the species phylogeny corresponded to four protein-coding nuclear regions and one mitochondrial region amplified using pheromone gland cDNAs as template. Phylogenetic reconstruction was inferred using MrBayes v3.2 (41). Only the open-reading frame sequence was used for phylogenetic reconstruction of the pgFARs. The similarity in topology between the species and pgFAR trees was estimated following the method described in ref. 42. (SI Materials and Methods).

Sequence Analysis and Tests of Selection.

Before testing for evidence of positive selection in the evolutionary history of the pgFAR gene, we explored whether recombination might have impacted our phylogenetic reconstruction and generated the pattern we observe. We tested for the presence of recombination breakpoints using GARD, a genetic algorithm for recombination detection available through the Datamonkey webserver (www.datamonkey.org) (43, 44). GARD predicted three breakpoints of which none showed significant topological incongruence using the Kishino-Hasegawa test, even at P = 0.1. Therefore, the breakpoints predicted by GARD are more likely due to spatial rate variation or heterotachy rather than recombination.

We performed a sliding window analysis of the Ka/Ks ratio of nonsynonymous over synonymous substitutions based on Li’s method (45) by using the SWAAP 1.0.2 software. Next, we tested for evidence of positive selection using the random effects likelihood (REL) and the fast unbiased approximate Bayesian (FUBAR) tests of selection (both are implemented on the Datamonkey webserver) and the maximum likelihood methods implemented in Codeml, part of the PAML 4.4b package (46). In Codeml, we performed the analysis using the species tree and tested the specific site models implemented (M1, M2, M7, and M8). Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare the neutral models with the corresponding selection models (M1 vs. M2, M7 vs. M8, and M8a vs. M8). Results from the comparisons were consistent, all supporting the action of positive selection. The Bayes empirical Bayes procedure implemented under model M8 was used to identify sites under positive selection.

Analysis of Pheromone Precursors.

Data were taken from previous published studies. When no data were available, tetradecenoyl precursors of pheromone components were analyzed in the form of methyl-esters (FAMEs) according to the method described earlier (47).

Functional Assays.

Functional assays were carried out in a yeast expression system following the procedures described previously (10, 33). Briefly, the ORFs of the various pgFAR genes were cloned into the expression vector pYES2.1/V5-His TOPO (Invitrogen), and the resulting recombinant vectors were used to transform the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisae (INVSc1 strain; Invitrogen). Samples were analyzed by GC-MS (SI Materials and Methods).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Targeted mutagenesis was performed using a PCR-based approach and the Quickchange II Site-directed mutagenesis method (Stratagene). Mutagenic oligonucleotide primers were designed with the QuikChange Primer design program (www.stratagene.com). In most cases, a single nucleotide substitution was sufficient to introduce the targeted amino acid change. All clones were sequenced in both directions to confirm the introduction of the mutated nucleotide. The functional assays with individual precursors were carried out following the procedures described above. For each pgFAR mutant and substrate, the absolute amount of fatty alcohol produced was derived using the internal standard method (n = 2–4). Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to define clusters based on the dissimilarities (distances) between the WT and single-codon mutant pgFARs. We used the absolute amount of each fatty-alcohol product and the proportion of each individual alcohol within the total amount of alcohol produced (standardized z scores). The analysis was carried out in SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Hedenström and coworkers for supplying the precursors and J. Bielawski, R. G. Harrison, W. L. Roelofs, and N. D. Rubinstein for valuable discussions and comments. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, Carl Trygger Foundation for Scientific Research, and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant 23248008.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. JX683280–JX683364).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1208706110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wyatt TD. Pheromones and Animal Behaviour: Communication by Smell and Taste. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smadja C, Butlin RK. On the scent of speciation: The chemosensory system and its role in premating isolation. Heredity (Edinb) 2009;102(1):77–97. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Symonds MRE, Elgar MA. The evolution of pheromone diversity. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23(4):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butlin R, et al. Marie Curie SPECIATION Network What do we need to know about speciation? Trends Ecol Evol. 2012;27(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristensen NP, Scoble MJ, Karsholt O. Lepidoptera phylogeny and systematics: The state of inventorying moth and butterfly diversity. Zootaxa. 2007;1668:699–747. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Löfstedt C. Moth pheromone genetics and evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1993;340:167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardé RT, Haynes KF. Structure of the pheromone communication channel in moths. In: Carde RT, Millar JG, editors. Advances in Insect Chemical Ecology. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2004. pp. 283–332. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roelofs WL, et al. Evolution of moth sex pheromones via ancestral genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(21):13621–13626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152445399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassance J-M, et al. Allelic variation in a fatty-acyl reductase gene causes divergence in moth sex pheromones. Nature. 2010;466(7305):486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature09058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii T, et al. Sex pheromone desaturase functioning in a primitive Ostrinia moth is cryptically conserved in congeners’ genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(17):7102–7106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019519108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leary GP, et al. Single mutation to a sex pheromone receptor provides adaptive specificity between closely related moth species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(35):14081–14086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204661109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linn CE, Young MS, Gendle M, Glover TJ, Roelofs WL. Sex pheromone blend discrimination in two races and hybrids of the European corn borer moth, Ostrinia nubilalis. Physiol Entomol. 1997;22(3):212–223. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kochansky J, Cardé RT, Liebherr J, Roelofs WL. Sex pheromone of the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), in New York. J Chem Ecol. 1975;1(2):225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y, et al. Geographic variation in sex pheromone of Asian corn borer, Ostrinia furnacalis, in Japan. J Chem Ecol. 1998;24(12):2079–2088. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boo KS, Park JW. Sex pheromone composition of the Asian corn borer moth, Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in South Korea. J Asia Pac Entomol. 1998;1(1):77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurenka RA, Roelofs WL. Characterization of the acetyltransferase used in pheromone biosynthesis in moths: Specificity for the Z isomer in tortricidae. Insect Biochem. 1989;19(7):639–644. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao CH, Lu F, Bengtsson M, Löfstedt C. Substrate specificity of acetyltransferase and reductase enzyme systems used in pheromone biosynthesis by Asian corn borer, Ostrinia furnacalis. J Chem Ecol. 1995;21(10):1496–1510. doi: 10.1007/BF02035148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu JW, Zhao CH, Bengtsson M, Löfstedt C. Reductase specificity and the ratio regulation of E/Z isomers in the pheromone biosynthesis of the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;26(2):171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wahlberg N, Wheat CW. Genomic outposts serve the phylogenomic pioneers: Designing novel nuclear markers for genomic DNA extractions of lepidoptera. Syst Biol. 2008;57(2):231–242. doi: 10.1080/10635150802033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mutanen M, Wahlberg N, Kaila L. Comprehensive gene and taxon coverage elucidates radiation patterns in moths and butterflies. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277(1695):2839–2848. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwast KE, et al. Genomic analyses of anaerobically induced genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Functional roles of Rox1 and other factors in mediating the anoxic response. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(1):250–265. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.1.250-265.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betts MJ, Russell RB. Amino acid properties and consequences of substitutions. In: Barnes MR, Gray IC, editors. Bioinformatics for Geneticists. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2003. pp. 289–316. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linn CE, Roelofs WL. Pheromone communication in moths and its role in the speciation process. In: Lambert DM, Spencer HG, editors. Speciation and the Recognition Concept: Theory and Application. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Press; 1995. pp. 263–300. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tillman JA, Seybold SJ, Jurenka RA, Blomquist GJ. Insect pheromones—an overview of biosynthesis and endocrine regulation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;29(6):481–514. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roelofs WL, Rooney AP. Molecular genetics and evolution of pheromone biosynthesis in Lepidoptera. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(16):9179–9184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1233767100a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Sayed AM. 2011. The Pherobase: Database of insect pheromones and semiochemicals. Available at http://www.pherobase.com. Accessed February 2, 2012.

- 28.Sakai R, Fukuzawa M, Nakano R, Tatsuki S, Ishikawa Y. Alternative suppression of transcription from two desaturase genes is the key for species-specific sex pheromone biosynthesis in two Ostrinia moths. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39(1):62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albre J, et al. Sex pheromone evolution is associated with differential regulation of the same desaturase gene in two genera of leafroller moths. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(1):e1002489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shirangi TR, Dufour HD, Williams TM, Carroll SB. Rapid evolution of sex pheromone-producing enzyme expression in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(8):e1000168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dallerac R, et al. A delta 9 desaturase gene with a different substrate specificity is responsible for the cuticular diene hydrocarbon polymorphism in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(17):9449–9454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150243997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao CH, Löfstedt C, Wang XY. Sex pheromone biosynthesis in the Asian corn borer Ostrinia furnacalis (II) - Biosynthesis of (E)-12-tetradecenyl and (Z)-12-tetradecenyl acetate involves delta14 desaturation. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1990;15(1):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liénard MA, Hagström ÅK, Lassance J-M, Löfstedt C. Evolution of multicomponent pheromone signals in small ermine moths involves a single fatty-acyl reductase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(24):10955–10960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000823107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dobzhansky T. Genetics and the Origin of Species. New York: Columbia Univ Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butlin R. Genetic variation in mating signals and responses. In: Lambert DM, Spencer HG, editors. Speciation and the Recognition Concept: Theory and Application. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Press; 1995. pp. 327–366. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bengtsson BO, Löfstedt C. Direct and indirect selection in moth pheromone evolution: Population genetical simulations of asymmetric sexual interactions. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 2007;90(1):117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groot AT, et al. Experimental evidence for interspecific directional selection on moth pheromone communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(15):5858–5863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508609103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabata J, et al. Sex pheromone of Ostrinia sp newly found on the leopard plant Farfugium japonicum. J Appl Entomol. 2008;132(7):566–574. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antony B, et al. Pheromone-gland-specific fatty-acyl reductase in the adzuki bean borer, Ostrinia scapulalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39(2):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall TA. (1999) BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(12):1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nye TMW, Liò P, Gilks WR. A novel algorithm and web-based tool for comparing two alternative phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(1):117–119. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pond SLK, Frost SDW. Datamonkey: Rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(10):2531–2533. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Posada D, Gravenor MB, Woelk CH, Frost SDW. GARD: A genetic algorithm for recombination detection. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(24):3096–3098. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li W-H. Unbiased estimation of the rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution. J Mol Evol. 1993;36(1):96–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02407308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang ZH. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabata J, Hoshizaki S, Tatsuki S, Ishikawa Y. Heritable pheromone blend variation in a local population of the butterbur borer moth Ostrinia zaguliaevi (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Chemoecology. 2006;16(2):123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishikawa Y, et al. Ostrinia spp. in Japan: Their host plants and sex pheromones. Entomol Exp Appl. 1999;91(1):237–244. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng ZQ, et al. Sex pheromone components isolated from China corn borer, Ostinia furnacalis Guenée (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae), (E)-12-tetradecenyl and (Z)-12-tetradecenyl acetates. J Chem Ecol. 1981;7(5):841–851. doi: 10.1007/BF00992382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lassance J-M. Journey in the Ostrinia world: From pest to model in chemical ecology. J Chem Ecol. 2010;36(10):1155–1169. doi: 10.1007/s10886-010-9856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu X, Fukuzawa M, Tabata J, Tatsuki S, Ishikawa Y. Sex pheromone biosynthesis in Ostrinia zaguliaevi, a congener of the European corn borer moth O. nubilalis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35(6):621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roelofs WL, et al. Sex pheromone production and perception in European corn borer moths is determined by both autosomal and sex-linked genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(21):7585–7589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.