In a reported cluster of cases of SARS among Canadian health care workers,1 infections occurred despite apparent compliance with recommended infection control precautions. In the report it was noted that contact with a patient or with a contaminated environment might have led to health care workers infecting themselves as they removed their personal protective equipment (PPE). Many health care workers apparently lacked a clear understanding of how best to remove PPE without contaminating themselves. However, the correct order of removal as presented in the report was extremely condensed (gloves first, followed by mask and goggles).1

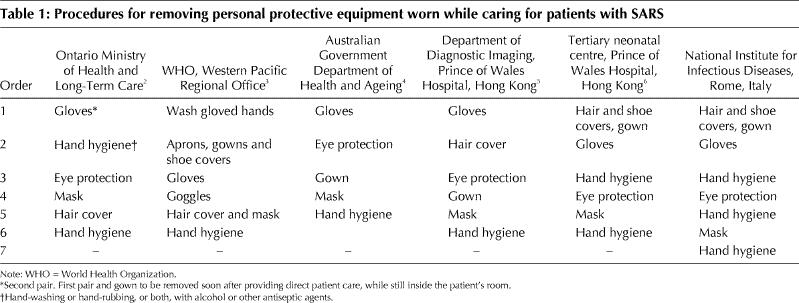

In fact, little information about the appropriate sequence of removing PPE is available, and what is available often contains contrasting recommendations (Table 1).2,3,4,5,6 Moreover, for several of these sets of recommendations, hands potentially contaminated through contact with patients' droplets and secretions present on the PPE could contact the nose, mouth or eyes while the health care worker is removing his or her mask and eye protection.

Table 1

Careful hand hygiene plays a pivotal role in reducing the risk of transmission of SARS. Accordingly, the National Institute for Infectious Diseases in Italy has developed a procedure whereby the health care worker removes most PPE while wearing mask and eye protection and carefully decontaminates the hands before removing protection of the mucous membranes of the face. This procedure must be carried out in the health care worker's change area, outside the patient's isolation room.

Vincenzo Puro Emanuele Nicastri National Institute for Infectious Diseases IRCCS Lazzaro Spallanzani Rome, Italy

References

- 1.Cluster of severe acute respiratory syndrome cases among protected health care workers — Toronto, April 2003. Can Commun Dis Rep 2003;11:93-7. [PubMed]

- 2.Young JG, D'Cunha C. Directive 03-05(R). Directives to all Ontario acute care hospitals regarding infection control measures for SARS units. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2003 Apr 24. Available: www.homecareontario.ca/docs/sars/Apr%2024%20-%20Infection%20Control%20Directive%20Acute%20Care%20Hospitals.pdf (accessed 2003 Nov 6).

- 3.Interim guidelines for national SARS preparedness. Manila, Philippines: World Health Organization, Western Pacific Regional Office; updated 2003 May 13, revised 2003 May 26. Available: www.wpro.who.int/sars/interim_guidelines/interim_guidelines_26May.pdf (accessed 2003 Nov 6).

- 4.Interim Australian infection control guidelines for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; updated 2003 May 16. Available: www.health.gov.au/sars/guidelines/index.htm (accessed 2003 Nov 6).

- 5.Ahuja AT, Wong JKT. Management and infection control in a radiology department during the SARS outbreak. In: Radiological appearance of recent cases of atypical pneumonia in Hong Kong. Shatin, NT, Hong Kong: Prince of Wales Hospital; 2003 Mar 21, updated 2003 Jul 30. Available: www.droid.cuhk.edu.hk/web/atypical_pneumonia/atypical_pneumonia.htm#infection (accessed 2003 Nov 6). See “Specific personal infection control guidelines for staff and patients.”

- 6.Ng PC, So KW, Leung TF, Cheng FW, Lyon DJ, Wong W, et al. Infection control for SARS in a tertiary neonatal centre. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003;88(5):F405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]