Abstract

Although biallelic mutations in non-collagen genes account for <10% of individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta, the characterization of these genes has identified new pathways and potential interventions that could benefit even those with mutations in type I collagen genes. We identified mutations in FKBP10, which encodes the 65 kDa prolyl cis–trans isomerase, FKBP65, in 38 members of 21 families with OI. These include 10 families from the Samoan Islands who share a founder mutation. Of the mutations, three are missense; the remainder either introduce premature termination codons or create frameshifts both of which result in mRNA instability. In four families missense mutations result in loss of most of the protein. The clinical effects of these mutations are short stature, a high incidence of joint contractures at birth and progressive scoliosis and fractures, but there is remarkable variability in phenotype even within families. The loss of the activity of FKBP65 has several effects: type I procollagen secretion is slightly delayed, the stabilization of the intact trimer is incomplete and there is diminished hydroxylation of the telopeptide lysyl residues involved in intermolecular cross-link formation in bone. The phenotype overlaps with that seen with mutations in PLOD2 (Bruck syndrome II), which encodes LH2, the enzyme that hydroxylates the telopeptide lysyl residues. These findings define a set of genes, FKBP10, PLOD2 and SERPINH1, that act during procollagen maturation to contribute to molecular stability and post-translational modification of type I procollagen, without which bone mass and quality are abnormal and fractures and contractures result.

INTRODUCTION

During the last several years nine genes have been identified in which biallelic mutations give rise to autosomal recessive forms of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) and related conditions. We have found that recessively inherited forms of OI account for ∼5% of all mutations in the >2500 individuals we have characterized (unpublished data). Although >90% of individuals with OI have dominant mutations in the type I collagen genes, COL1A1 and COL1A2, the recessively inherited forms of OI hold out the promise that the identification of the minimal alteration that results in the phenotype could identify better and more directed forms of intervention than currently available. The genes targeted in the recessive forms of OI and related disorders fall into six groups: first, a transcription factor involved in osteoblast differentiation (SP7, which encodes osterix) (1); second, CRTAP (2–4), LEPRE1 (2,5) and PPIB (6–8) which encode the components of the prolyl 3-hydroxylation complex, cartilage associate protein (CRTAP), prolyl 3-hydroxylase (P3H1) and cyclophilin B (CYPB), respectively; third, SERPINH1 (9) and FKBP10 (10–16) which encode two chaperone-like proteins, heat shock protein 47 (HSP47) and FKBP65, respectively; fourth, PLOD2 (17,18) which encodes lysyl hydroxylase 2 (LH2) that can hydroxylate lysyl residues outside the major triple helix of type I collagen crucial to formation of mature intermolecular cross-links in bone, cartilage and other tissues and, fifth, BMP1 (19,20), which encodes the protease that removes the carboxyl-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen. Mutations in SERPINF1 (21,22), which encodes pigment epithelium-derived factor, form a separate group with the mechanism yet to be clearly defined.

Mutations in CRTAP, LEPRE1 and PPIB appear to affect the rate of chain association or the efficiency of folding of the triple helix of the chains of type I procollagen so that the chains can become overmodified because of prolonged residence in an unfolded form. The effect mimics that of mutations in type I collagen genes (COL1A1 and COL1A2) that disrupt chain association or helix propagation. A complex of these three proteins in the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) is responsible for 3-hydroxylation of the prolyl residue at position 986 of the triple-helical domain in the proα1(I) chain (3,5,6). In contrast, mutation in SERPINH1 does not disrupt the initial phases of folding but the final details of helix formation appear to be left unattended so that apparently intact molecules remain unexpectedly protease sensitive (9,23). In the absence of HSP47 (encoded by SERPINH1), type I procollagen molecules have a shorter residence time in the RER and are quickly transported to the Golgi (9). Although mutations in FKBP10 appear to effect a subtle delay in the rate of type I procollagen secretion (10), neither type I procollagen molecules made by those cells nor those made by cells from individuals with mutations in PLOD2 (24) are overmodified, indicating that the actions of FKBP65 and LH2 are independent of CRTAP, P3H1 and CYPB in the assembly and secretory pathway of type I procollagen molecules.

FKBP65 is an RER resident protein and is a member of the family of prolyl cis–trans isomerases that are inhibited by FK506, a drug that has effects on immunological integrity (25). It is not clear that FKBP65 has an immune system function but, instead, has been found to associate with the extracellular matrix protein tropoelastin during its transit through the secretory pathway (25). Recently, Alanay et al. (10) identified a set of families from Turkey that had the combination of a recessively inherited form of epidermolysis bullosa simplex that resulted from mutations in KRT14, located on chromosome 17 and a co-segregating recessive form of OI. A region of 4 Mb on chromosome 17q21.2 was identical by descent in all affected members in multiple families. This region contained FKBP10, which had become a candidate because of its ability to bind gelatin (denatured collagen) sepharose (26). All affected members of these families were homozygous for a 33 bp deletion in exon 2 of FKBP10. Analysis of DNA from a consanguineous Mexican family identified a 1 bp insertion that led to a frameshift, a downstream termination codon and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay with no residual protein. Subsequent studies suggested that the phenotypic range in those with FKBP10 mutations overlapped that of individuals with mutations in the PLOD2 gene and a clinical picture of Bruck syndrome (12).

We have now identified missense, nonsense and frameshift mutations in FKBP10 all of which are associated with a phenotype that overlaps with Bruck syndrome, characterized by congenital contractures and fractures, that results from mutations in PLOD2 (18). We have confirmed that some individuals thought to have Bruck syndrome have mutations in FKBP10, we have found that members of a previously published Bruck syndrome family in which bone collagen cross-linking was abnormal (24) have missense mutations in FKBP10, and we have demonstrated that bone collagen cross-links are abnormal in individuals with null mutations in FKBP10. Given this clinical overlap and biochemical analysis of bone collagen from one of the subjects studied here that demonstrated abnormal hydroxylation of cross-links, it is clear that FKBP10 represents a Bruck syndrome locus. The absence or marked diminution of FKBP65 appears to mediate the phenotype, at least in part, through a failure of LH2, encoded by PLOD2, to fully hydroxylate telopeptide lysines in type I collagen molecules in bone.

RESULTS

Clinical presentations: phenotype and clinical findings

We identified 33 subjects with FKBP10 mutations from 21 unrelated families; a further five subjects from three of these families were identified on clinical grounds to bring the total number of affected individuals to 38 (Table 1). Seventeen subjects (from 10 families) originated from Samoa (or nearby islands) in the South Pacific, and 17 subjects (from 7 families) from different Middle Eastern countries and the remaining 4 were identified in the USA. Clinical data on four subjects from two families (Families K and R, Table 1), thought on clinical grounds to have Bruck syndrome, were previously published (27,28).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of individuals with FKBP10 mutations

| ID | Sex | Contractures at birth | Fractures |

Scoliosis | Long bone deformity | Mobility | Acetabular protrusion | Height Z-scorea | Skull |

Cortical width—2nd MCa | Radial shaft BMDa | Comment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth to age 1 year | Fracture site and (age) | Head Circuma | Wormian bones | Platybasia | |||||||||||

| Family A FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| A1 | F | No | No | Femur (18y) | Yes (13y) | Yes | Unaided (22y) | Yes | −4.7 (A) | +3.7 | Yes | Yes | −1.0 | +0.5 | |

| A2 | F | Talipes | No | Humerus (16y) | Yes | Yes | Two crutches (18y) | Yes | −3.4 (12y) | +3.8 | Yes | Yes | +1.3 | ||

| Family B FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| B1 | F | No | Multiple (incl both femora) | Femur (5y), Tibia (15y), Radius/ulna (23y) | Yes (15y) | Yes | Never walked (44) | Yes | −6.0 (A) | +4.0 | Yes | Yes | −1.0 | +0.3 | |

| B2b | M | Wrist | Femur, ulnae | Femur (4y) | Yes (14y) | Yes | Two crutches (14y) | Yes | −5.5 (14y) | Yes | Died following scoliosis surgery (age 14y) | ||||

| B3b | F | No | Multiple | Tibia (20y) | Yes (10y) | Yes | Never walked (22y) | Yes | −5.5 (A) | Died age 22y – cause unknown | |||||

| B4 | M | No | No | Femur (10y), Tibiae (20y) | Yes | Yes | Unaided (34y) | Yes | −3.6 (A) | +2.5 | Yes | Yes | +0.5 | +0.3 | |

| B5 | F | No | No | Femur (4y,14y,18y) | Yes | Yes | One crutch (19y) | Yes | −3.1 (A) | +2.5 | Yes | Yes | 0.0 | −0.9 | |

| Family C FKBP10: [c.831dupC] + [c.948dupT], [p.Gly278Argfs*95] + [p.Ile317Tyrfs*56] | |||||||||||||||

| C1 | F | No | No | Femur (11y,13y) | Yes | Yes | Unaided (35y) | Yes | −5.6 (A) | +3.0 | Yes | Yes | −0.5 | −0.3 | |

| C2 | M | Talipes, multiple contractures | No | No (26y) | Yes | Yes | Two crutches (26y) | Yes | −5.0 (A) | Died of respiratory failure (age 26y) | |||||

| Family D FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| D1 | M | Talipes, multiple contractures | No | No (3y) | No | No | Unable to stand (2y) | No | −2.0 (2y) | +0.2 | |||||

| Family E FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| E1 | M | Talipes, multiple contractures | Multiple, including both femora | Fibula (2½y) | No | Yes | Unable to walk (3y) | No | −1.2 (1y) | +2.5 | Yes | Yes | |||

| Family F FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| F1 | M | No | Clavicle, scapula | Scapula (2y), clavicle (3y), femur (5y), vertebral | No (8y) | Yes | Stopped walking age 3y | Yes | +0.3 (7y) | Yes | |||||

| Family G FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| G1 | F | Talipes, knee contractures | Femur x2, forearm, ribs | Kyphosis | No | Yes | |||||||||

| Family H FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| H1 | F | Ribs, clavicle | ‘Acetabular dysplasia’ | 0.0 (5m) | −0.7 (5m) | Yes | |||||||||

| Family I FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| I1 | F | No | No | Tibiae and others (from age 3y) | Yes (11y) | Wheelchair (39y) | Sibling with ‘spina bifida’ died in infancy | ||||||||

| I2 | F | No | No | Vertebrae, femora, shoulder (from age 8y) | Yes (13y) | Wheelchair (37y) | |||||||||

| Family J FKBP10: c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | |||||||||||||||

| J1 | M | Yes | Tibiae, forearm, humerus | Yes | Never walked | ||||||||||

| Family K FKBP10: c.344G > A, p.Arg115Gln | |||||||||||||||

| K1 | F | Yes; severe degree at knees, ankles (12y) | No | L ilium (12y) | Yes | Unable to walk (12y) | Yes, severe | −4.5 (12y) | +0.4(12y) | Yes (12y) | (24,28) | ||||

| K2 | F | Yes; severe degree at hips, knees, ankles (7y) | No | Femur, recurrent (7y) | Yes | Yes, both femora (7y) | Unable to walk (7y) | −3.8 (7y) | −2.9 (7y) | Yes (7y) | |||||

| K3b | M | Yes; both hips, knee (2y) | No | No | No | No (2y) | Able to stand (2y) | −4.9 (2y) | 0.0 (2y) | ||||||

| Family L FKBP10: c.1330C > T, p.Gln444Ter | |||||||||||||||

| L1 | F | Both elbows | 2 fractures at birth | Multiple long bones | Yes (8y) | Yes, tibiae | −4.5 (8y) | −0.3 (8y) | Yes | ||||||

| L2 | M | L elbow | Femur x2 by 14d | No (4y) | −4.0 (4y) | 0.0 | Pectus carinatum | ||||||||

| L3 | F | L elbow, both knees | No | No (3y) | +0.7 (3y) | ||||||||||

| L4b | F | L elbow | R femur and tibia | +2.0 | |||||||||||

| L5b | F | Talipes, knee, elbow | |||||||||||||

| Family M FKBP10: c.743dupC, p.Gln249Thrfs*12 | |||||||||||||||

| M1 | F | ‘OI type III’ (age 6y) | |||||||||||||

| M2 | F | Yes | ‘OI type III’ (age 4y) | ||||||||||||

| Family N FKBP10: c.831dupC, p.Gly278Argfs*95 | |||||||||||||||

| N1 | F | Yes (knees) | Arm fracture (8m) | Several long bones (humeri, femora) | Yes | Yes (femora, tibiae) | Walks with difficulty | −3.9 (13y) | +0.0 (13y) | Yes | |||||

| N2 | F | Yes (knees) | Several long bones (humeri, femora), vertebrae | Yes | Yes (femora, tibiae) | Walks (6y) | −3.8 (6y) | −0.1 (6y) | Yes | ||||||

| Family O FKBP10: c.14delG, p.Gly5Alafs*154 | |||||||||||||||

| O1 | F | Yes | R foot at 4m | 3–4 every year | Yes (11y) | Yes | Wheelchair (11y) | Yes | −5.7 (13y) | +2.0 (11y) | Yes | Yes | |||

| O2 | F | Yes (elbows, knees, ankles) | At 6m | 7 fractures by age 13 | Yes (13y) | Yes | Wheelchair (13y) | Yes | −3.9 (13y) | +3.3 (13y) | Yes | Yes | Died of restrictive lung disease | ||

| Family P FKBP10: c.288dupG, p.Arg97Alafs*101 | |||||||||||||||

| P1 | F | ‘Multiple neonatal’ | Several - long bones, ribs, vertebrae | No (3½y) | Yes | Not walking (3½y) | −4.0 (3½y) | Yes | L1–4″ −6.7″ (3½y) | ||||||

| Family Q FKBP10: c.337G > A, p.Glu113Lys | |||||||||||||||

| Q1 | M | Yes (arms and legs) | Multiple- long bones, ribs | Yes | Yes | Mostly wheelchair | Yes | −10.0 (20y) | −0.7 (20y) | ||||||

| Q2 | F | No | Several (femora, tibiae) | No | Non-ambulatory (3½y) | ||||||||||

| Family R FKBP10: c.337G > A, p.Glu113Lys | |||||||||||||||

| R1 | M | Elbows, thumbs, bilateral talipes | R femur, ribs | ‘Many fractures’ incl. vertebral | Yes | Yes (femora) | Never walked | −9.0 (19y) | −0.6 (19y) | Yes | Died age 21y - respiratory failure (27) | ||||

| Family S FKBP10: c.407C > T, p.Pro136Leu | |||||||||||||||

| S1 | M | Yes (elbows, knees) | Long bones, ribs, vertebrae | Yes (tibiae, R femur) | |||||||||||

| Family T FKBP10: c.831dupC, p.Gly278Argfs*95 | |||||||||||||||

| T1 | F | Yes (arms) | None | ‘many’ from age 2y | Yes | Some bowing - not severe | Walker at home, wheelchair outside | −6.5 (30y) | Basilar invagination (8y) | ||||||

| Family U FKBP10: c.831dupC, p.Gly278Argfs*95 | |||||||||||||||

| U1 | M | No | Yes (14y) | Walks with difficulty | Yes, severe (14y) | ‘Mild short stature’ | ‘OI type IV’ | ||||||||

Numbers in parentheses indicate age in years (y), months (m), or days (d) at which assessment was made or event occurred. A, adult. In the case of scoliosis the age at which corrective spinal surgery was undertaken is shown. Blank fields, no information available.

aStandard deviation scores.

bPhenotypic information only (no genetic confirmation).

BMD, bone mineral density, measured by DEXA scanning; Circum, circumference; L/R, left/right; MC, metacarpal.

Some details of families K and R have been previously published—references are shown in the last column.

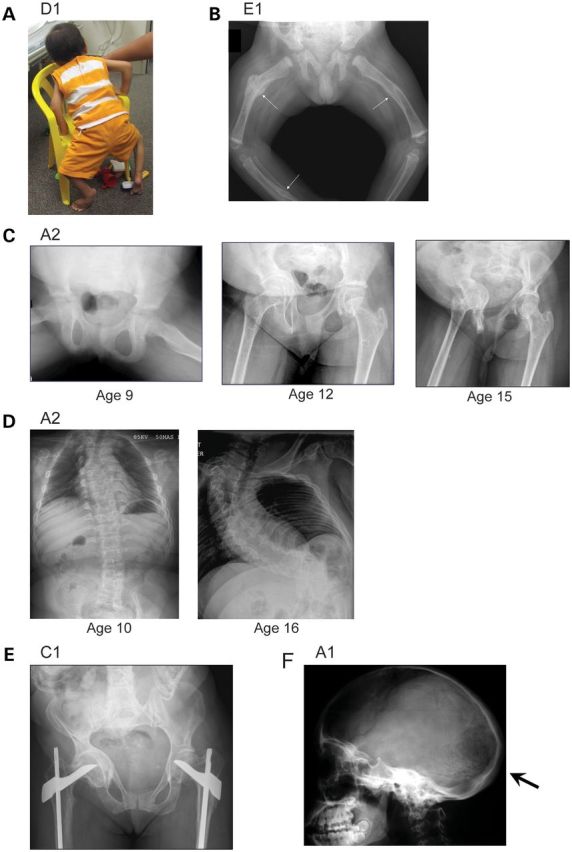

Twenty eight of the subjects were identified in infancy because they presented with contractures (14 subjects) or fractures (5 subjects) or both (9 subjects). Flexion contractures were evident at birth, and variably affected the elbows and knees (preventing full extension) and the ankle, preventing dorsiflexion and presenting as talipes (Fig. 1A). Contractures of the wrists or digits were uncommon. Fractures were most common in the femurs (Fig. 1B), were often multiple and occasionally were detected in utero.

Figure 1.

Clinical and radiographic variability in patients with FKBP10 mutations. (A) Subject D1 (age 2½ years). He is of short stature (<3rd centile) and is unable to plantar flex either foot or extend the knees because of contractures. By the age of 3 he had sustained no fractures. (B) Radiograph from subject E1 age 3 months. Fractures were noted in utero and limb contractures were present at birth. At age 3 months he had a skull fracture and multiple rib and long bone fractures (arrows). (C) Development of severe acetabular protrusion during adolescence in A2. (D) The development of scoliosis in A2. Her first fracture occurred at the age of 16 years. (E) Subject C1 age 35. Note marked acetabular protrusion on the right. She sustained femoral fractures at age 11 and 13, but has had no fractures since. (F) Skull findings of playtbasia, relative macrocephaly and Wormian bones (arrow) in A1.

A smaller group of seven subjects presented later in childhood, typically with pain on walking or long bone fractures (most commonly the femur between the ages of 4 and 18 years). The difficulty with ambulation was the result of progressive acetabular protrusion (unilateral or bilateral), which led in some to severe impairment of mobility (Fig. 1C). For three individuals, the details of their original presentations were not available.

Phenotypic diversity was apparent within families. For example, in family B two siblings were severely affected with multiple neonatal fractures and never walked independently, whereas their younger sibling's diagnosis only came to light when he fractured his femur playing rugby at the age of 10. In family C the elder child presented at the age of 11 with a fractured hip, scoliosis and acetabular protrusion. In contrast, her younger brother had severe contractures at birth and never attained unaided mobility but had suffered no fractures by the time of his death from respiratory failure at the age of 26 years. Irrespective of the age at presentation, all subjects had white sclerae with normal hearing and teeth. Wormian bones were present on all skull radiographs available to us.

Clinical data after the age of 10 years were available in 19 subjects. All 19 had scoliosis that developed during adolescence and often progressed rapidly (Fig. 1D); six subjects underwent scoliosis surgery at a median age of 13 years. The development of scoliosis was strongly associated with restrictive lung disease on pulmonary function tests. Some subjects were reported to have vertebral fractures, but severe scoliosis often made assessment of this difficult. The median height was −5.3 SD (range −3.1 to −10.0); both scoliosis and contractures contributed to the short stature. Acetabular protrusion was present in all those with pelvic radiographs (n = 13) (Fig. 1C and E). There was relative macrocephaly; the median head circumference was +2.0 SD (range −2.9 to +4.0) and skull radiographs demonstrated platybasia (Fig. 1F). Only three subjects (all from the late-presenting group) remained ambulatory without any walking aids at the ages of 22, 34 and 35 years, respectively.

Laboratory findings

Plasma calcium and phosphate concentrations were normal, and the bone formation markers alkaline phosphatase and procollagen-1 N-propeptide were all within age-appropriate normal ranges in the individuals for whom they were measured.

Bone density DEXA scanning at the spine and femoral sites often produced artifacts from scoliosis, fractures and acetabular protrusion. In five subjects from the Samoan group, the mean age-related SD (Z-score) at the radial shaft site was normal at 0.0 (range −0.9 to +0.5). The mean Z-score for the cortical width at the mid-point of the second metacarpal measured from hand radiographs in six subjects was −0.1 (range: −1.0 to +1.3).

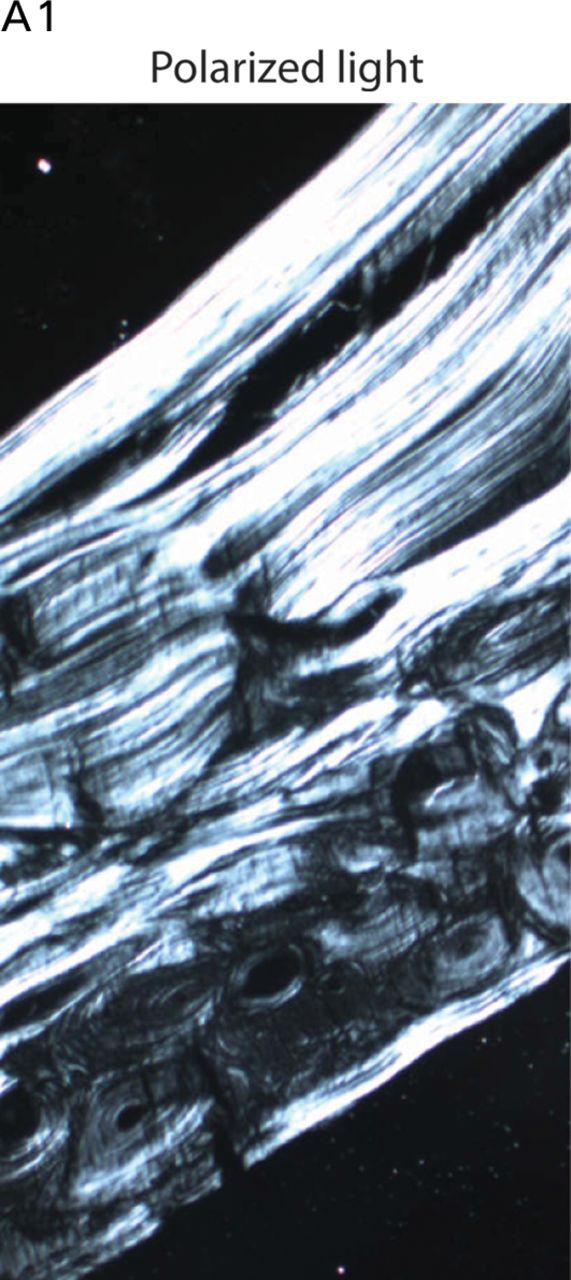

Undecalcified sections from a transiliac bone biopsy showed trabecular osteopenia, but the cortices were of above average width. There was no mineralization defect and under polarized light the bone had a normal lamellar structure (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Bone histology. Undecalcified transiliac bone biopsy from A1 at age 17. Under polarized light a normal lamellar pattern is evident, which distinguishes the pattern from that seen in bone from individuals with OI type VI that results from mutations in SERPINF1.

FKBP10 mutations identified

We identified 9 separate mutations in these 21 families (Fig. 3 and Table 2), five of which resulted in frameshifts and unstable mRNA, three were missense mutations and one was a nonsense mutation. All but two (C1, C2) of the 33 affected individuals tested were homozygous for a mutation seen in the family. In 9 of the 10 families that derived from the Samoan or nearby islands (families A, B and D–J), the affected individuals were homozygous for a single basepair duplication (c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56) that resulted in a translational frameshift and mRNA instability (data not shown) so that no protein was produced from the mutant allele (Fig. 4B). Individuals from family C were heterozygous for the c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 mutation (inherited from their Samoan mother) and for another frameshift mutation (c.831dupC, p.Gly278Argfs*95, inherited from the European father) that also resulted in mRNA instability. We identified the second mutation seen in family C in members of three other families (N, T and U), all of whom were homozygous for the alteration. Two additional frameshifts that resulted from duplication of single nucleotides were seen in a Family P from East Africa/Somalia (c.288dupG, p.Arg97Alafs*101) and Family M from the Middle East (c.743dupC, p.Gln249Thrfs*12). At the time of ascertainment, all these affected individuals were thought to have either an unusual form of OI or a variant form of OI type IV. Because of known familial consanguinity, recessive inheritance was assumed in the last two families. The affected families from the Samoan islands were not known to each other and consanguinity was not recognized in those families.

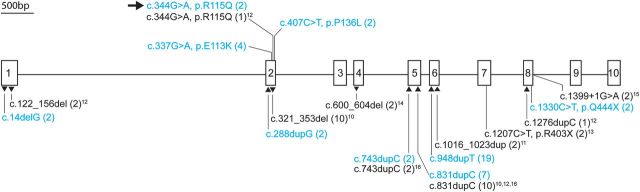

Figure 3.

Location of mutations in FKBP10. The gene diagram is drawn to scale. Mutations identified in this study are shown in cyan and those identified by others in black. Missense mutations are indicated above the diagram. Frame shift and nonsense mutations and a single splice site mutation are depicted below. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of alleles. The superscripts link the published mutations to the respective references. The arrow pointing at ‘c.344G > A, p. R115Q (2)’ indicates that the cross-linking data were published by Bank et al. (24).

Table 2.

Mutations in FKBP10

| Family | FKBP10 exon | Mutation description (A of the initiator methionine codon = 1) | Effect of mutation | Location of premature termination codon | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | 1 | [c.14delG] + [c.14delG] | p.Gly5Alafs*154 + p.Gly5Alafs*154 | Exon 3 | Homozygous |

| P | 2 | [c.288dupG] + [c.288dupG] | p.Arg97Alafs*101 + p.Arg97Alafs*101 | Exon 4 | Homozygous |

| Q | 2 | [c.337G > A] + [c.337G > A] | p.Glu113Lys + p.Glu113Lys | NA | Homozygous |

| R | 2 | [c.337G > A] + [c.337G > A] | p.Glu113Lys + p.Glu113Lys | NA | Homozygous |

| K | 2 | [c.344G > A] + [c.344G > A]) | p.Arg115Gln + p.Arg115Gln | NA | Homozygous |

| S | 3 | [c.407C > T] + [c.407C > T] | p.Pro136Leu + p.Pro136Leu | NA | Homozygous |

| M | 5 | [c.743dupC] + [c.743dupC] | p.Gln249Thrfs*12 + p.Gln249Thrfs*12 | Exon 5 In some transcripts exons 5 and 6 are skipped (336 nt) which is in-frame and stable |

Homozygous |

| N | 5 | [c.831dupC] + [c.831dupC] | p.Gly278Argfs*95 + p.Gly278Argfs*95 | Exon 7 | Homozygous. Parents studied and both shown to be heterozygous |

| U | 5 | [c.831dupC] + [c.831dupC] | p.Gly278Argfs*95 + p.Gly278Argfs*95 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| T | 5 | [c.831dupC] + [c.831dupC] | p.Gly278Argfs*95 + p.Gly278Argfs*95 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| C | 5 | [c.831dupC] + [c.948dupT] | p.Gly278Argfs*95 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 Exon 7 |

Compound heterozygous |

| A | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| B | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| D | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| E | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| F | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| G | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| H | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| I | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| J | 6 | [c.948dupT] + [c.948dupT] | p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 + p.Ile317Tyrfs*56 | Exon 7 | Homozygous |

| L | 8 | [c.1330C > T] + [c.1330C > T] | p.Gln444Ter + p.Gln444Ter | Exon 8 | Homozygous |

Figure 4.

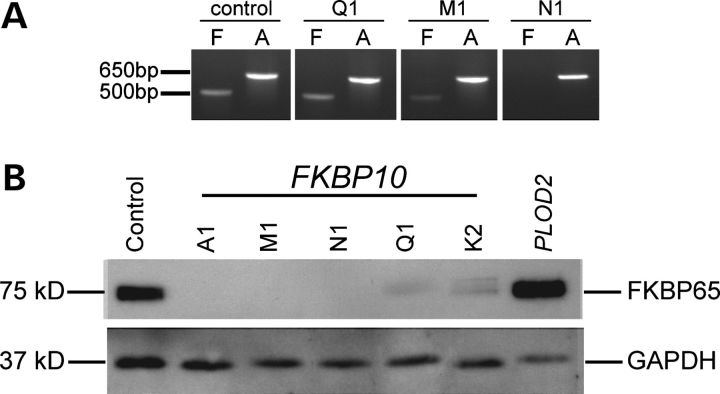

Analysis of the effect of mutations in FKBP10 and PLOD2 on the stability of mRNA and FKBP65, the protein product of FKBP10. (A) Mutations in FKBP10 have different effects on mRNA stability that depend on the nature of the mutation. RNA was isolated from the cells from Q1 (c.337G > A, p.Glu113Lys), M1 (c.743dupC, p.Gln249Thrfs*12), and N1 (c.831dupC, p.Gly278Argfs*95), cDNA was synthesized and then amplified for 30 cycles with primers in exons 3 and 6. The first lane, F, for each sample represents the FKBP10 amplification, and the second lane, A, represents actin. In the presence of the missense mutation (Q1), the mRNA is stable and similar in abundance to that in the control. In the M1 sample there is residual mRNA, and there is no measurable stable mRNA from the cells from N1. (B) Mutations in FKBP10 result in unstable or diminished FKBP65 protein. Western blot analysis showed loss of the FKBP65 protein in individuals with frameshifts due to single base duplications in FKBP10 (A1 [c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56], M1, and N1), and marked reduction of protein in individuals with missense mutations (Q1 and K2). Compound heterozygosity for a missense and nonsense mutation in PLOD2 has no effect on the amount of FKBP65 present.

The homozygous nonsense mutation (c.1330C > T, p.Gln444Ter) that we identified in Family L occurred in exon 8, which is the second to last exon, and is predicted to result in unstable FKBP10 mRNA. All known affected members of this family (L1–L5) had congenital contractures and were thought to have Bruck syndrome.

In the remaining four families, we identified missense mutations. In two of these families (R and K), the affected individuals were considered to have Bruck syndrome and described in publications used, in part, to define the characteristic biochemical features of that condition (24,27). In the third family (Q) with the same mutation seen in family R, the ethnic origin was different and the presentation was thought to best fit in the OI type III group but with contractures. The child in the fourth family (S) was thought to have Bruck syndrome because of joint contractures and fractures.

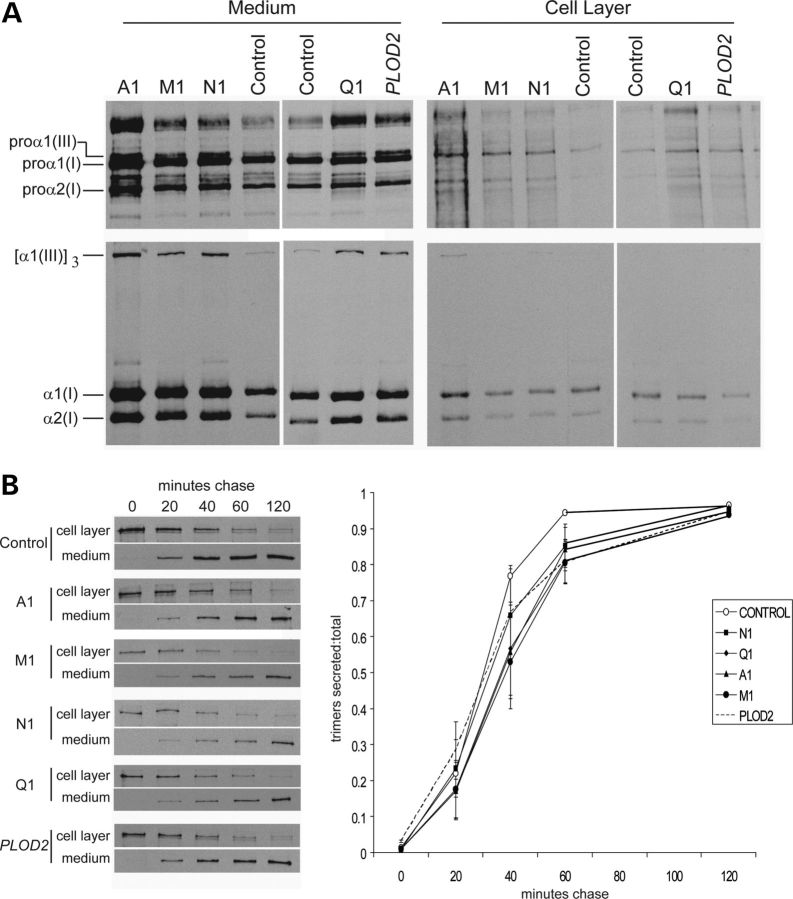

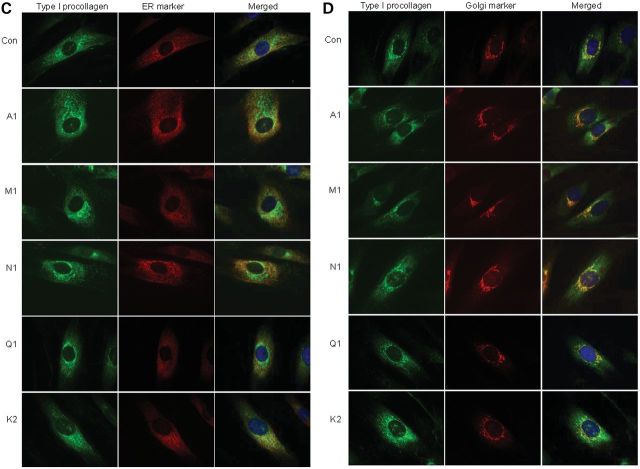

Effects of mutations in FKBP10 on FKBP65 protein and intracellular processing

Cells from individuals with FKBP10 frameshift mutations identified in families A, M and N had very unstable mRNA (data not shown; Fig. 4A) and produced no protein when assessed by western blot analysis (Fig. 4B). In those with missense mutations (families Q and K), the protein was unstable and very little was present in the cell (Fig. 4B). Alanay et al. (10) previously showed that the electrophoretic mobility of chains of type I procollagen and collagen were normal but type I procollagen secretion was slightly delayed. We could replicate those findings with cultured dermal fibroblasts (Fig. 5A and B) from individuals homozygous for other FKBP10 mutations. In contrast to the Alanay et al. (10) findings, we did not see type I procollagen aggregates in our patient fibroblasts, but there was slight RER retention when compared with control fibroblasts (Fig. 5C and D). Secreted type I procollagen molecules had subtle and localized regional instability (Fig. 6A and B) similar to but less marked than that seen with a mutation in the SERPINH1 gene (see Fig. 6A) (9).

Figure 5.

Effects of different mutations in FKBP10 on synthesis and intracellular transport of type I procollagen through the cell. (A) Type I procollagen is not overmodified in cells from individuals with frameshift (A1, M1, N1), missense (Q1) mutations in FKBP10 or biallelic mutations in PLOD2. Cells were labeled with [3H]-proline for 16 h and macromolecules in the culture medium and in the cell layer were harvested and separated after reduction of disulfide bonds (top panels) or treated with pepsin to remove the amino- and carboxyl-terminal propeptides and separated under non-reducing conditions. (B) There is a modest delay in secretion of type I procollagen from cells with mutations in FKBP10 and PLOD2. Cells were labeled for 1 h with [3H]-proline then chased for up to 2 h with unlabeled proline. At 60 min, the rate of secretion of the trimers of type I procollagen showed a delay in the patient cells compared with control (standard t-test, P-value of 0.046), quantitated in the graph to the right. (C and D) Distribution of type I procollagen between the RER (C) and the Golgi (D). Complete loss of FKBP65 as a result of frameshift mutations in FKBP10 (A1, M1, N1) and partial loss of protein that results from missense mutations (Q1, K2) all lead to slight retention of type I procollagen in the RER. Aggregates of type I procollagen reported by Alanay et al. (10) are not evident in these images.

Figure 6.

Mutations in FKBP10 affect protease sensitivity of the type I collagen triple helix. (A) Secreted type I procollagen molecules from cells with FKBP10 mutations are more sensitive to proteolytic digestion than those from control cells, with the apparent cleavage sites similar to those with mutations in SERPINH1. Proteins in medium from cultured dermal fibroblasts labeled overnight with [3H]-proline were digested for 1 or 5 min with a combination of trypsin and chymotrypsin at 37°C without prior cooling of the sample. Procollagens secreted into the culture medium by control cells and then pretreated at 50°C for 15 min were completely degraded following treatment with trypsin/chymotrypsin while procollagens from medium left at 37°C had protease-resistant triple-helical domains. A subset of type I procollagen molecules secreted from patient cells were cleaved asymmetrically at 37°C (the black arrows indicate fragments seen in affected cells and either not seen or in low abundance in the control cells). (B) Characterization by cyanogen bromide cleavage of products of type I procollagen following trypsin/chymotrypsin treatment. The gel lanes from runs equivalent to those in (A) were excised and the bands cleaved with cyanogen bromide. The larger of the new bands, which migrated just below α2(I) was derived from α1(I). The α1(I)CB7 fragment (residues 551–821 of the triple-helical domain) is missing and replaced by fragment A. The size of the fragment indicates that the parent peptide had been cleaved at or near the mammalian collagenase cleavage site (775–776 in the triple-helical domain). The smaller fragment in the parent gel was derived from α2(I). The α2(I)CB3-5 fragment (residues 357–1014 in the triple-helical domain) was shortened, fragment B and the estimated size indicated that it had been cleaved in the region of the collagenase cleavage site (residues 776–777 of the triple-helical domain).

Effects on hydroxylysyl pyridinoline (HP) and lysyl pyridinoline (LP) cross-linking

Fibrillar collagen molecules in tissues are connected through lysyl- and hydroxylysyl-derived cross-links. The mature trifunctional cross-links (pyridinolines) join three chains from three different collagen molecules and involve two telopeptide lysines and one from the triple-helical domain. The involved lysyl residues are located in the amino-terminal and carboxyl-terminal telopeptides and two sites in the triple-helical domain. LH2, encoded by PLOD2, is thought to be the major modifying enzyme for the telopeptide residues and LH1, encoded by PLOD1, is largely responsible for hydroxylation of the triple-helical cross-linking lysyl residues (24,29). Pyridinoline cross-links were decreased in bone collagen from two individuals in family K (K1 and K2) thought to have Bruck syndrome [described in (24)], in whom no PLOD2 mutation was identified (17) but who we found were homozygous for a missense mutation in FKBP10 (c. 344G > A, p.Arg115Gln; Table 2 and Fig. 3). Those cross-linking findings indicated that there was underhydroxylation of telopeptide lysines in bone type I collagen.

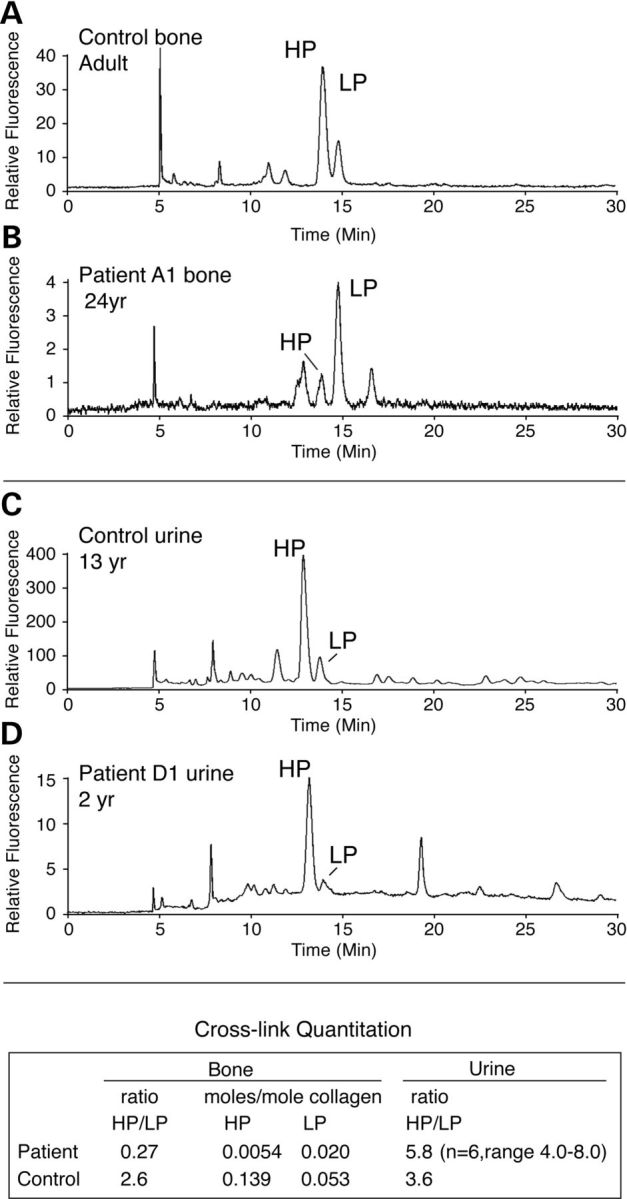

To extend those studies and compare the effect of null mutations in FKBP10, we measured hydroxylysyl pyridinoline (HP) and lysyl pyridinoline (LP) cross-links in bone from A1 and in urine from N1, N2, B1, B4, B5 and D1 (Fig. 7). The content of total pyridinolines in bone from A1, an adult with the Samoan FKBP10 mutation, was about one-tenth that of normal bone (moles/mole of collagen) (Fig. 7A and B). HP is formed by the condensation of three hydroxylated lysyl residues, from two telopeptides and one helical site. LP is formed by condensation of two hydroxylated telopeptide lysyl residues and a non-hydroxylated helical lysyl residue. The abnormally low ratio of HP/LP and very low total pyridinoline content of the bone suggest that there was underhydroxylation of helical domain cross-linking lysines as well as telopeptide lysines. The reversed HP/LP ratio in the FKBP10 bone collagen (Fig. 7B) required the molecular sieve clean-up step to observe on HPLC because pyridinoline levels were low. Without the first step, background fluorescence overshadowed the HP peak giving a falsely high HP/LP ratio. This may explain why such low ratios were not previously reported for bone from an FKBP10 case of Bruck syndrome (24). The HP/LP ratio in urine was higher than normal and did not match the inverse ratio found in the FKBP10 mutant bone collagen. Most of the HP found in FKBP10 mutant urine, however, appears to be derived from cartilage collagen, a conclusion supported by the structure of the cross-linked peptide from the C-telopeptide domain of type II collagen present in FKBP10 mutant and normal urines (see Fig. 9D).

Figure 7.

HP and LP pyridinoline cross-links in hydrolysates of bone from an individual with a frameshift mutation in FKBP10, control human bone and urine samples from affected and control individuals. In patient A1 bone (B and table) the ratio of HP/LP is reversed from normal (A) and the pyridinoline cross-link content (moles/mole collagen) is ∼10% of that in control adult bone. Compared with control (C) the HP/LP ratio is higher in urine from D1 (D). The table shows the mean and range for the HP/LP ratios in urine samples from N1, N2, B1, B4, B5 and D1. Note that the total amount of pyridinoline cross-links in urine from individuals with mutations in FKBP10 is markedly lower than that seen in control urine (see the fluorescence scale difference between C and D).

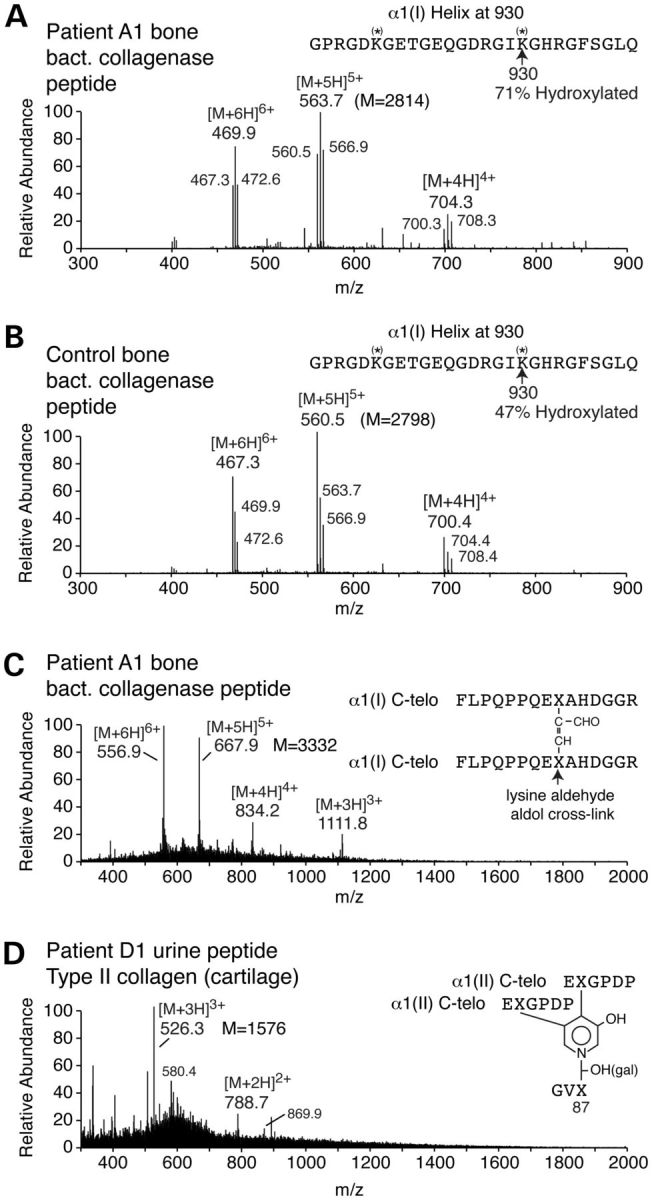

Figure 9.

Electrospray mass spectrometry of a bacterial collagenase-derived peptide from the α1(I) Lys-930 cross-linking site of bone type I collagen and a urinary peptide from individuals with a frameshift mutation in FKBP10. (A and B) Peptide pools containing the Lys-930 cross-linking lysine were isolated by C8 reverse-phase HPLC from bacterial collagenase digests of A1and control adult bone collagen and profiled for post-translational variants. In the A1 bone Lys-930 (A) was 71% hydroxylated versus 47% in control bone (B). The lysine at 918 was less hydroxylated than the one at position 930 in control and A1 bone. (C) The digest of A1 bone collagen contained a peptide (M = 3332 Da), not found in normal bone, that proved to be the lysine aldol dimer of two α1(I)-C-telopeptide fragments (C). The parent ion charge envelope of the latter is shown (556.96+, 667.95+, etc) from which the MS/MS fragmentation patterns (not shown) and molecular mass established the structure shown. (D) The structure of a cross-linked peptide pool from the urine of D1 is derived from the C-telopeptide cross-linking domain of type II collagen and contains exclusively an HP cross-link. This peptide was identified in control children's urine (29) and the 526.33+ and 788.72+ ions are of the unglycosylated HP peptide and 580.44+ and 869.92+ are the galactosyl (mono-glycosylated) HP version.

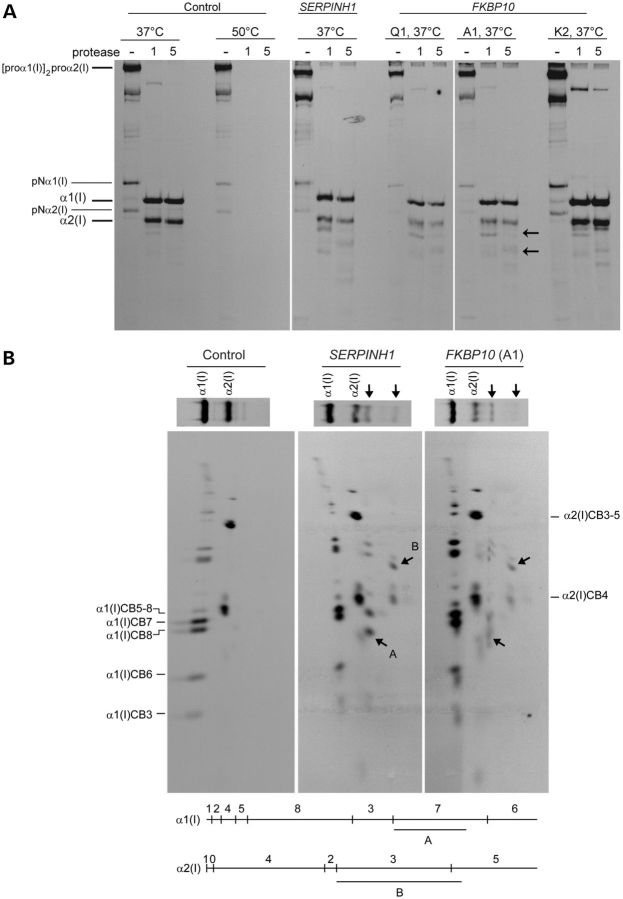

Mass spectral peptide analysis of the effects of FKBP10 mutations on bone and cartilage collagen cross-linking

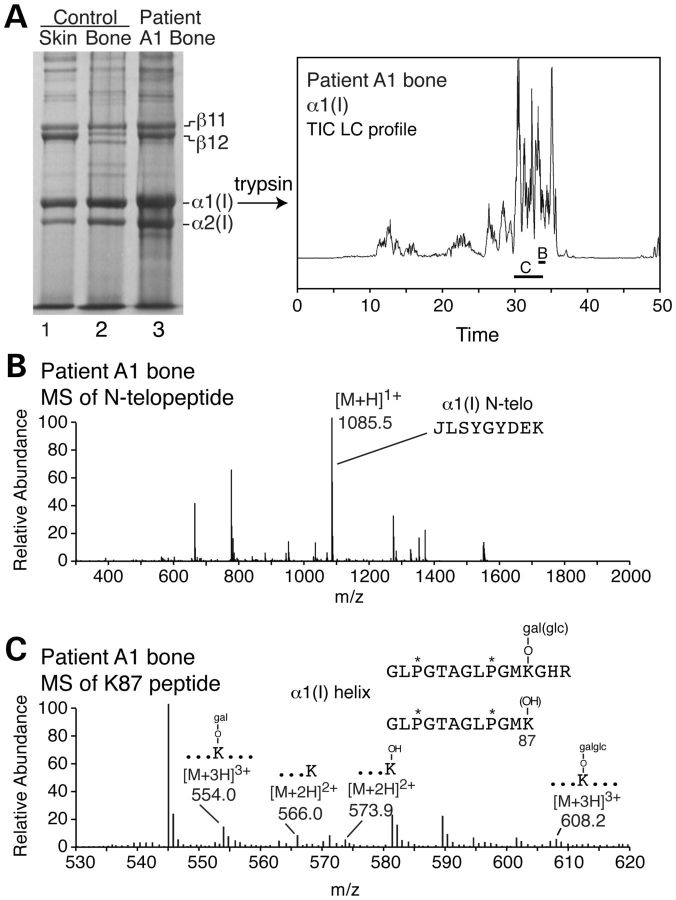

On electrophoresis type I collagen extracted from FKBP10 mutant bone had a cross-linked β-dimer pattern similar to that seen in normal skin rather than bone (Fig. 8A). There was an increase in the relative amount of the α1(I)–α2(I) dimer (β12) species. The β-dimers from skin are derived from intramolecular cross-links and the increased amount is consistent with failure to progress along the pathway to form the hydroxylysine-based cross-links seen in normal bone. To determine whether the effect on pyridinoline formation reflected changes in telopeptide hydroxylation, the α1(I) chains from bone were fragmented with trypsin and the peptides were identified by tandem mass spectrometry. A fragment found in the sample from the bone from A1 but not the control contained an N-telopeptide lysyl residue that was not hydroxylated (Fig. 8B). All four species of a peptide that contained the cross-linking lysyl residue at position 87 of the triple helix of α1(I) were identified: those with no hydroxylation, the hydroxylated residue, and the mono- and di-glycosylated species (Fig. 8C). Tandem mass spectrometric analysis of peptides prepared by bacterial collagenase digestion of bone collagen identified a prominent peptide in patient A1 and control (Fig. 9A and B). The peptide contained the triple helical domain cross-linking lysine at position 930 of the triple helical domain of the proα1(I) chains (Lys-930). From the mass spectral MS/MS data (not shown), this residue was significantly more hydroxylated in the A1 sample than the same lysine residue in the control. The same bacterial collagenase digest also contained a peptide in patient bone, absent in control bone, that consisted of two α1(I) C-telopeptides cross-linked by an allysine aldol formed between two (non-hydroxylated) lysyl residues (Fig. 9C). Together, these results (Figs 8 and 9) indicate that telopeptide lysine residues are underhydroxylated but the triple helical cross-linking lysyl residues (Lys-87 and Lys-930) are slightly overmodified in bone type I collagen in the absence of FKBP65.

Figure 8.

Electrospray mass spectrometry of tryptic peptides from cross-linking sites in bone type I collagen from an individual (A1) with a frameshift mutation in FKBP10. (A) SDS–PAGE analysis of collagen extracted from control skin, control bone and demineralized patient bone (A1). The pattern of the dimeric cross-linked forms (β11 and β12) in A1 bone is more like that in control skin than in control bone. Individual chains were digested with trypsin and the peptides separated by LCMS. Peptides in the regions marked B and C were further analyzed as shown in sections B and C. (B) The amino-terminal telopeptide from α1(I) contained a non-hydroxylated lysyl residue which was not seen in control bone (latter data not shown). (C) The hydroxylation and glycosylation status of Lys-87 cross-linking site in α1(I) reflected marked heterogeneity among molecules.

To identify the source of the HP in urine, we used mass spectrometry to seek cross-linked peptides (Fig. 9D). There was a prominent component in all urines from affected family members. This peptide had the mass and fragmentation pattern of an HP residue linking fragments of two C-telopeptides and the helical domain containing Lys-87 from type II collagen. In this peptide, all three lysines were hydroxylated and essentially no LP-containing variant of the peptide was evident in urine from the affected individuals or urine from unaffected individuals.

Mass spectral analysis of bone collagen from patient A1 showed that 3-hydroxylation of the prolines at triple-helical position 986 of the proα1(I) chains (Pro-986) and Pro-707 in α2(I) (data not shown) was normal. This is consistent with the effect in fibroblasts in culture (10). These findings suggest that FKBP65 likely has complex interactions with LH2 and/or its collagen substrate sites but does not play a role in the 3-hydroxylation pathway that is disturbed by mutations in CRTAP, LEPRE1 and PPIB.

DISCUSSION

FKBP10 encodes a member of the FK506-binding protein family known as FKBP65, a reflection of its molecular mass of 65 kDa. Originally identified as a tropoelastin-binding protein, it clearly has additional ligands (25). We identified biallelic mutations in FKBP10 in members of 21 families who were ascertained because they were thought to have a variety of OI even though most of the usual causes of OI had been excluded. Among these are 10 families in which the probands are residents of or have strong family links to the Samoan islands or the nearby northern Tongan islands; all have the same mutation (c.948dupT, p.Ile317Tyrfs*56). It is likely that this is a founder mutation brought in the initial migration of the early Polynesian settlers to these islands some 3 millennia ago. In four other families that are from different global regions, we identified a common mutation (c.831dupC, p.Gly278Argfs*95) that reflects slippage during replication in a sequence that harbors seven consecutive cytosines and highlights the hazard of extended runs of a single nucleotide to the coding elements in the genome. Sequence analysis of the region indicated that the mutation in each family had occurred on a different allelic background. The same mutation was identified in other studies in families of Mexican, Turkish, South African and Caucasian origin (10,12) which argues for independent origins of the mutation. This is compatible with findings in many other disorders in which this type of mutation is recurrent. The majority of families we identified have mutations that result in mRNA instability and loss of measurable FKBP65 protein in the cell.

Since the identification of mutations in FKBP10 by Alanay et al. in 2010 (10), mutations have been identified in individuals originally thought to have Bruck syndrome, characterized by congenital contractures and fractures with apparent recessive inheritance (11–14,16). In the families we studied, this includes families R and K (17,27,28). Families restudied by Kelley et al. (12) include those originally described by Viljoen et al. (30) and by Mokete et al. (31).

There is striking phenotypic diversity in individuals with mutations in FKBP10. About half of the affected individuals sustained fractures in the neonatal period or the first year of life. The remainder had a pattern of fractures that was unusual for a moderate OI phenotype in that the first fractures (typically of the femur) occurred between the age of 2 and 18 years. Bone that was not immobile had normal or increased cortical width (Fig. 2) and normal bone density indicating that low bone mass was not the only factor in the etiology of fractures. The consistent finding of platybasia and acetabular protrusion suggest that the bone was unusually soft and malleable. A little more than half of the individuals we identified, regardless of type of mutation, had a clinical picture with neonatal contractures that overlaps substantially with that seen in individuals with Bruck syndrome who have biallelic mutations in PLOD2. PLOD2 encodes a long-splice form of lysyl hydroxylase (LH2b) that includes an alternatively spliced exon, has a preference for the non-triple helical lysyl residues located in the telopeptides of the type I collagen chains and is highly expressed in bone.

The genetic heterogeneity in individuals with congenital contractures and fractures was recognized by van der Slot et al. (17) who identified PLOD2 mutations in two of three families they studied with similar phenotypes. In the third, they obtained bone and demonstrated that the content of mature pyridinoline cross-links was markedly reduced, but they were unable to identify a mutation in PLOD2. That family is included in this study as family K, the affected members of which are homozygous for a missense mutation in FKBP10 (c.344G > A, p. Arg115Gln) that results in the production of a protein that is only partially stable.

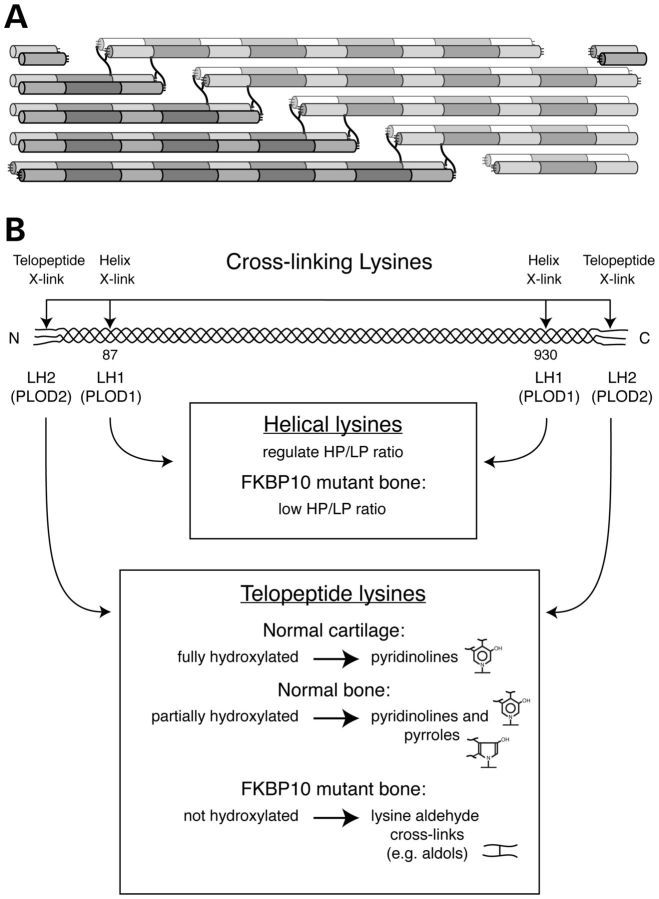

In bone from one of the Samoan individuals, there was a marked reduction in pyridinoline cross-links and inversion of the ratio (HP/LP) of the two isoforms in the pyridinoline cross-links that did form (Fig. 7). While this could be consistent with underhydroxylation of both telopeptide and helical site lysines, the peptide analyses (Figs 8C and 9A and B) showed that the level of hydroxylation at the helical sites was normal or higher. In bone the triple-helical lysyl residues at the Lys-87 and Lys-930 cross-linking sites in type I collagen chains are usually hydroxylated by LH1 (29) whereas the telopeptide lysines are hydroxylated by LH2. Our findings point to a selective effect in osteoblasts on the ability of LH2 to hydroxylate telopeptide lysines in the chains of type I collagen that alters cross-linking (Fig. 10). Some PLOD2 missense mutations cause enzyme inactivity through misfolding of LH2 (32). It is reasonable to suspect that the underhydroxylation of telopeptide lysyl residues caused by FKBP10 mutations could result from misfolding of LH2 because the enzyme is a substrate for the cis–trans isomerase. Alternatively, the telopeptide substrates may need to be folded into an accessible form. The reversed HP/LP ratio in the bone collagen (Fig. 7) might result if the few hydroxylysine aldehydes formed in telopeptides showed preferential bonding to lysines over hydroxylysines at the partially hydroxylated triple-helical sites.

Figure 10.

Pathway of cross-link formation in bone type I collagen and cartilage type II collagen. (A) The symmetrically placed four sites of lysine-based cross-linking in types I and II collagen molecules, two telopeptide and two triple-helical, interact to form cross-links in fibrils. (B) Two lysyl hydroxylases regulate collagen cross-linking in bone. LH1 is primarily responsible for hydroxylation of the K87 and K930 sites in the triple-helical domain, and LH2 hydroxylates the telopeptide lysines. With mutations in FKBP10 there is selective underhydroxylation of telopeptide lysines in bone type I collagen but not cartilage type II collagen, similar to the situation in Bruck syndrome caused by PLOD2 mutations (18,24).

The effect of loss of FKBP65 is probably more complex than just the marked diminution of lysyl hydroxylation. The secreted type I procollagen appears to have regions of instability, similar to those seen in the context of mutations in SERPINH1 (9,23), which encodes the molecular chaperone HSP47. Although we have not been able to demonstrate stable interactions between FKBP65 and LH2 or HSP47, the effect on the activities of these proteins suggests that either they are substrates for FKBP65 and that their activity depends on the isomerization of the peptide bonds involving at least one prolyl residue or that the region in the telopeptide of type I collagen chains is a substrate. Structural analysis of a unique mutation in equine PPIB (which encodes cyclophilin B) that results in fragile skin alters interaction with LH1 and leads to alterations in collagen cross-links in skin that reflect diminished hydroxylation of the triple-helical lysyl residues in type I collagen (33). Cyclophilin appears to act in the early phases of collagen formation by an effect on folding of the carboxyl-terminal propeptides into conformations that can form trimers (8), and a later phase of isomerization to the trans form of the peptidyl-prolyl bonds in the triple-helical domains to permit the formation of a stable triple helix (34). That function is not altered by the equine mutation. The absence of cyclophilin B results in slowing of chain association and of triple-helix formation with a consequent delay in exit from the RER. FKBP65 seems to act further downstream in the biogenesis of the collagen molecules and in tissue specific ways. It facilitates the hydroxylation of telopeptide lysyl residues involved in cross-link formation, and contributes to the final stages of triple-helix maturation. The clinical effects of mutations in these two isomerases are different.

The overlapping spectra of phenotypic consequences of FKBP10 and PLOD2 mutations appear to be causally linked though mechanisms that alter collagen cross-link formation by diminution of telopeptide lysyl hydroxylation. The variation seen in families with the same FKBP10 mutation no doubt reflects other genetic influences that, in large families or in limited populations like the Samoans, might be identified by current technologies. The overlap of the clinical effects of mutations in FKBP10 and PLOD2 may lead to diagnostic confusion and should lead to analysis of mutations in both genes until discrete elements of clinical presentation can be identified.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Identification of families for study

We identified mutations in FKBP10 with two strategies. First, because we participated with Alanay et al. (10) in the analysis of the effects of mutations in FKBP10, we screened for mutations in FKBP10 in 142 individuals selected because they had apparently recessively inherited forms of OI, or their cells, when available (84 of 142) made type I procollagen the chains of which had normal electrophoretic mobility, or they had no mutations in type I collagen genes. A number of these had mutations in another recessive OI gene [PLOD2 (1), SERPINF1 (2), SERPINH1 (1), CRTAP (1), LEPRE1 (2), PPIB (1), FBLN4 (1) (35)] or in type I collagen genes, COL1A1 (5), COL1A2 (1). Because one of the individuals in whom we identified an FKBP10 mutation had the clinical diagnosis of Bruck syndrome (27), we extended the search to include individuals thought to have Bruck syndrome. Second, homozygosity mapping (by M.R.H., A.A., K.C.) in families that originated from Samoa with a unique apparently recessively inherited form of OI identified a 4.8 Mb region of shared homozygosity on 17q in one family (A), in which, fortuitously, the gene had been sequenced as part of the first strategy. All samples screened were in the IRB approved Repository for Inherited Connective Tissue Disorders at the University of Washington. Once mutations were identified in individuals from Samoa, additional samples were obtained with appropriate consent from individuals with compatible phenotypes hospitalized for care in Honolulu (L.S.) or carried in practices in Auckland (T.C.), where the study was approved by the Auckland Regional Ethics Committee.

Mutation identification in FKBP10

Genomic DNA was extracted either from cultured dermal fibroblasts using the QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), or from peripheral blood using the Puregene® DNA purification kit (Gentra). DNA was extracted from a Guthrie card for one individual (C2) who had died and was used only for specific mutation analysis. The 10 exons of FKBP10 and flanking intronic sequences were amplified in eight reactions (primer sequences and amplification and sequencing conditions are available on request). Sequencing reactions were done using Big Dye Terminators, version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems), and run on an AB 3130XL or AB 3730XL Genetic Analyzer. Sequences were analyzed using Mutation Surveyor® (Softgenetics).

Analysis of collagen produced by cultured fibroblasts

Cells were cultured and type I procollagen and collagen were analyzed as previously described (36).

Western blot analysis of proteins

Fibroblasts (250 000) from affected individuals and controls were plated at confluence in 35 mm tissue culture dishes, allowed to attach overnight, incubated for 18 h in the presence of 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid, and proteins were harvested from the cell layer by ethanol precipitation. Proteins were resolved by 10% SDS–PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and visualized using standard western blot techniques with a polyclonal antibody to FKBP65 (25); GAPDH (Santa Cruz, sc-25778) was used as an internal control.

Pulse-chase studies

Pulse-chase studies were performed as previously described (9).

Immunocytochemical analysis of proteins in cultured fibroblasts

Fibroblasts (75 000) from affected individuals and controls were plated onto sterile coverslips in 12-well tissue culture plates, allowed to attach overnight and then incubated in the presence of 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid for 18 h. Immunofluorescence was performed using a modified protocol from Abcam (http://www.abcam.com/index.html?pageconfig=resource&rid=11417). Briefly, cells were rinsed with cold 1× PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× Sorenson's for 15 min at room temperature and permeabilized with 1X PBS + 0.25% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 10 min. Following a 1-h treatment in block solution at room temperature, primary polyclonal antibodies to type I procollagen (LF9) (37) were added in sets of two with either an antibody to the KDEL ER-marker protein (Abcam ab12223), or the 58 K Golgi protein (Abcam ab6284) and allowed to hybridize at room temperature for 2 h. Secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores (Invitrogen A11032, A11034) were incubated with cells for 1h at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted in Prolong + DAPI and cells were examined using a Nikon microphot-SA microscope. Images were captured using a Photometrics sensys monochrome digital camera.

Protease digestion assay

Protease sensitivity studies were performed as previously described (9).

Cyanogen bromide mapping

Cleavage of collagens with cyanogen bromide and peptide mapping was performed as previously described (36).

Sample preparation and separation of collagens in bone

An iliac crest biopsy was obtained from A1 with appropriate consent. Control adult bone was obtained from Northwest Tissues Services, Renton, WA. Bone was defatted in chloroform/methanol (3:1 v/v) and demineralized in 0.5 m EDTA at 4°C by established methods (38). Collagen was then solubilized from an aliquot of each tissue preparation by heat denaturation in SDS–PAGE sample buffer and the chains were separated in 5% SDS–PAGE gels (39).

Cross-link analysis

Bone and urine samples were hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl, dried and the material redissolved in 10% acetic acid. The soluble material was loaded on a Bio-Gel P-2 (Bio-Rad) column (1.5 cm × 30 cm) and then eluted with 10% acetic acid. The fractions that contained pyridinolines were pooled for quantitative analysis by C18 reverse-phase HPLC (40).

Mass spectrometry of collagen peptides

In-gel trypsin digests of collagen chains cut from SDS–PAGE gels were carried out as described (3,5). Demineralized bone was digested with bacterial collagenase (38) and the resulting collagen-derived peptides were separated by reverse-phase HPLC (C8, Brownlee Aquapore RP-300, 4.6 mm × 25 cm) with a linear gradient of acetonitrile:n-propanol (3:1 v/v) in aqueous 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (4). The pyridinoline cross-linked type II collagen C-telopeptide previously identified in urine (41,42) was enriched by reverse-phase and ion-exchange cartridge extraction and resolved by C8 HPLC for mass spectrometric analysis.

Electrospray MS was performed on in-gel trypsin digests and individual HPLC column fractions using an LCQ Deca XP ion-trap mass spectrometer equipped with in-line liquid chromatography (LC) (ThermoFinnigan) using a C8 capillary column (300 µm × 150 mm; Grace Vydac 208MS5.315) eluted at 4.5 µl/min. The LC mobile phase consisted of buffer A (0.1% formic acid in MilliQ water) and buffer B (0.1% formic acid in 3:1 acetonitrile:n-propanol v/v). The LC sample stream was introduced into the mass spectrometer by electrospray ionization (ESI) with a spray voltage of 3 kV. The Sequest search software (ThermoFinnigan) was used for linear peptide identification using the NCBI protein database. Cross-linked peptides and glycosylated variants were identified manually by calculating theoretical parent ion masses and possible ms/ms ions and matching these to the actual parent ion mass and ms/ms spectrum.

FUNDING

The studies on collagen cross-linking and mass spectral analyses were supported by NIH grants AR37694, AR37318 and HD22657 (to D.R.E.) and the Ernest M Burgess endowment of the University of Washington.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all the families who took part and to the staff at the Molecular Genetics Laboratory and National Testing Centre at LabPlus, Auckland City Hospital, and to Dr Viali Lameko, the Tupua Tamasese Meaole National and Teaching Hospital, Samoa, and to Dr Rebecca Shine for their invaluable assistance. Partial support for the activities described here is derived from the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Osteogenesis Imperfecta Foundation and the Freudmann Fund at the University of Washington.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lapunzina P., Aglan M., Temtamy S., Caparrós-Martín J., Valencia M., Letón R., Martínez-Glez V., Elhossini R., Amr K., Vilaboa N., et al. Identification of a frameshift mutation in Osterix in a patient with recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldridge D., Schwarze U., Morello R., Lennington J., Bertin T., Pace J., Pepin M., Weis M., Eyre D., Walsh J., et al. CRTAP and LEPRE1 mutations in recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:1435–1442. doi: 10.1002/humu.20799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morello R., Bertin T., Chen Y., Hicks J., Tonachini L., Monticone M., Castagnola P., Rauch F., Glorieux F., Vranka J., et al. CRTAP is required for prolyl 3- hydroxylation and mutations cause recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Cell. 2006;127:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marini J., Cabral W., Barnes A. Null mutations in LEPRE1 and CRTAP cause severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:59–70. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0872-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabral W., Chang W., Barnes A., Weis M., Scott M., Leikin S., Makareeva E., Kuznetsova N., Rosenbaum K., Tifft C., et al. Prolyl 3-hydroxylase 1 deficiency causes a recessive metabolic bone disorder resembling lethal/severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:359–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Dijk F., Nesbitt I., Nikkels P., Dalton A., Bongers E., van de Kamp J., Hilhorst-Hofstee Y., Den Hollander N., Lachmeijer A., Marcelis C., et al. CRTAP mutations in lethal and severe osteogenesis imperfecta: the importance of combining biochemical and molecular genetic analysis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;12:1560–1569. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes A., Carter E., Cabral W., Weis M., Chang W., Makareeva E., Leikin S., Rotimi C., Eyre D., Raggio C., et al. Lack of cyclophilin B in osteogenesis Imperfecta with normal collagen folding. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:521–528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pyott S.M., Schwarze U., Christiansen H.E., Pepin M.G., Leistritz D.F., Dineen R., Harris C., Burton B.K., Angle B., Kim K., et al. Mutations in PPIB (cyclophilin B) delay type I procollagen chain association and result in perinatal lethal to moderate osteogenesis imperfecta phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:1595–1609. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christiansen H., Schwarze U., Pyott S., AlSwaid A., Al Balwi M., Alrasheed S., Pepin M., Weis M., Eyre D., Byers P. Homozygosity for a missense mutation in SERPINH1, which encodes the collagen chaperone protein HSP47, results in severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alanay Y., Avaygan H., Camacho N., Utine G., Boduroglu K., Aktas D., Alikasifoglu M., Tuncbilek E., Orhan D., Bakar F., et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the RER protein FKBP65 cause autosomal-recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaheen R., Al-Owain M., Sakati N., Alzayed Z., Alkuraya F. FKBP10 and Bruck syndrome: phenotypic heterogeneity or call for reclassification? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:306–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.020. author reply 308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley B.P., Malfait F., Bonafe L., Baldridge D., Homan E., Symoens S., Willaert A., Elcioglu N., Van Maldergem L., Verellen-Dumoulin C., et al. Mutations in FKBP10 cause recessive osteogenesis imperfecta and Bruck syndrome. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:666–672. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinlein O.K., Aichinger E., Trucks H., Sander T. Mutations in FKBP10 can cause a severe form of isolated Osteogenesis imperfecta. BMC Med. Genet. 2011;12:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Setijowati E.D., van Dijk F.S., Cobben J.M., van Rijn R.R., Sistermans E.A., Faradz S.M., Kawiyana S., Pals G. A novel homozygous 5bp deletion in FKBP10 causes clinically Bruck syndrome in an Indonesian patient. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2011;55:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venturi G., Monti E., Carbonare L.D., Corradi M., Gandini A., Valenti M.T., Boner A., Antoniazzi F. A novel splicing mutation in FKBP10 causing osteogenesis imperfecta with a possible mineralization defect. Bone. 2011;50:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaheen R., Al-Owain M., Faqeih E., Al-Hashmi N., Awaji A., Al-Zayed Z., Alkuraya F.S. Mutations in FKBP10 cause both Bruck syndrome and isolated osteogenesis imperfecta in humans. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155A:1448–1452. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Slot A.J., Zuurmond A.M., Bardoel A.F., Wijmenga C., Pruijs H.E., Sillence D.O., Brinckmann J., Abraham D.J., Black C.M., Verzijl N., et al. Identification of PLOD2 as telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase, an important enzyme in fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40967–40972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha-Vinh R., Alanay Y., Bank R.A., Campos-Xavier A.B., Zankl A., Superti-Furga A., Bonafé L. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of Bruck syndrome (osteogenesis imperfecta with contractures of the large joints) caused by a recessive mutation in PLOD2. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;131:115–120. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asharani P.V., Keupp K., Semler O., Wang W., Li Y., Thiele H., Yigit G., Pohl E., Becker J., Frommolt P., et al. Attenuated BMP1 function compromises osteogenesis, leading to bone fragility in humans and zebrafish. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:661–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Glez V., Valencia M., Caparrós-Martín J.A., Aglan M., Temtamy S., Tenorio J., Pulido V., Lindert U., Rohrbach M., Eyre D., et al. Identification of a mutation causing deficient BMP1/mTLD proteolytic activity in autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:343–350. doi: 10.1002/humu.21647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker J., Semler O., Gilissen C., Li Y., Bolz H.J., Giunta C., Bergmann C., Rohrbach M., Koerber F., Zimmermann K., et al. Exome sequencing identifies truncating mutations in human SERPINF1 in autosomal-recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Homan E.P., Rauch F., Grafe I., Lietman C., Doll J.A., Dawson B., Bertin T., Napierala D., Morello R., Gibbs R., et al. Mutations in SERPINF1 cause osteogenesis imperfecta type VI. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:2798–2803. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagai N., Hosokawa M., Itohara S., Adachi E., Matsushita T., Hosokawa N., Nagata K. Embryonic lethality of molecular chaperone hsp47 knockout mice is associated with defects in collagen biosynthesis. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1499–1506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bank R.A., Robins S.P., Wijmenga C., Breslau-Siderius L.J., Bardoel A.F., van der Sluijs H.A., Pruijs H.E., TeKoppele J.M. Defective collagen crosslinking in bone, but not in ligament or cartilage, in Bruck syndrome: indications for a bone-specific telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase on chromosome 17. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1054–1058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis E.C., Broekelmann T.J., Ozawa Y., Mecham R.P. Identification of tropoelastin as a ligand for the 65-kD FK506-binding protein, FKBP65, in the secretory pathway. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:295–303. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa Y., Vranka J., Wirz J., Nagata K., Bächinger H.P. The rough endoplasmic reticulum-resident FK506-binding protein FKBP65 is a molecular chaperone that interacts with collagens. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:31584–31590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McPherson E, Clemens M. Bruck syndrome (osteogenesis imperfecta with congenital joint contractures): review and report on the first North American case. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997;70:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslau-Siderius E.J., Engelbert R., Pals G., van der Sluijs J.A. Bruck syndrome: a rare combination of bone fragility and multiple congenital joint contractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 1998;7:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinmann B., Eyre D.R., Shao P. Urinary pyridinoline cross-links in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VI. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;57:1505–1508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viljoen D., Versfeld G., Beighton P. Osteogenesis imperfecta with congenital joint contractures (Bruck syndrome) Clin. Genet. 1989;36:122–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1989.tb03174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mokete L., Robertson A., Viljoen D., Beighton P. Bruck syndrome: congenital joint contractures with bone fragility. J. Orthop. Sci. 2005;10:641–646. doi: 10.1007/s00776-005-0958-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyry M., Lantto J., Myllyharju J. Missense mutations that cause Bruck syndrome affect enzymatic activity, folding, and oligomerization of lysyl hydroxylase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:30917–30924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa Y., Vranka J.A., Boudko S.P., Pokidysheva E., Mizuno K., Zientek K., Keene D.R., Rashmir-Raven A.M., Nagata K., Winand N.J., et al. The mutation in cyclophilin B that causes hyperelastosis cutis in the American Quarter Horse does not affect peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity, but shows altered cyclophilin B-protein interactions and affects collagen folding. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:22253–22265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.333336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishikawa Y., Wirz J., Vranka J., Nagata K., Bächinger H. Biochemical characterization of the prolyl 3-hydroxylase 1.cartilage-associated protein.cyclophilin B complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:17641–17647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erickson L.K., Opitz J., Zhou H.H. Lethal osteogenesis imperfecta-like condition with cutis laxa and arterial tortuosity in MZ twins due to a homozygous Fibulin-4 mutation. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2011;15:137–141. doi: 10.2350/11-03-1010-CR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonadio J., Holbrook K., Gelinas R., Jacob J., Byers P. Altered triple helical structure of type I procollagen in lethal perinatal osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:1734–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher L., Hawkins G., Tuross N., Termine J. Purification and partial characterization of small proteoglycans I and II, bone sialoproteins I and II, and osteonectin from the mineral compartment of developing human bone. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:9702–9708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanson D.A., Eyre D.R. Molecular site specificity of pyridinoline and pyrrole cross-links in type I collagen of human bone. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26508–26516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eyre D.R. Collagen cross-linking amino acids. Methods Enzymol. 1987;144:115–139. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)44176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eyre D., Shao P., Weis M.A., Steinmann B. The kyphoscoliotic type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (type VI): differential effects on the hydroxylation of lysine in collagens I and II revealed by analysis of cross-linked telopeptides from urine. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2002;76:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eyre D.R., Weis M.A., Wu J.J. Advances in collagen cross-link analysis. Methods. 2008;45:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]