Abstract

MicroRNA cluster miR-17-92 has been implicated in cardiovascular development and function, yet its precise mechanisms of action in these contexts are uncertain. This study aimed to investigate the role of miR-17-92 in morphogenesis and function of cardiac and smooth muscle tissues. To do so, a mouse model of conditional overexpression of miR-17-92 in cardiac and smooth muscle tissues was generated. Extensive cardiac functional studies identified a dose-dependent induction of dilated, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmia inducibility in transgenic animals, which correlated with premature mortality (98.3±42.5 d, P<0.0001). Expression analyses revealed the abundance of Pten transcript, a known miR-17-92 target, to be inversely correlated with miR-17-92 expression levels and heart size. In addition, we demonstrated through 3′-UTR luciferase assays and expression analyses that Connexin43 (Cx43) is a novel direct target of miR-19a/b and its expression is suppressed in transgenic hearts. Taken together, these data demonstrate that dysregulated expression of miR-17-92 during cardiovascular morphogenesis results in a lethal cardiomyopathy, possibly in part through direct repression of Pten and Cx43. This study highlights the importance of miR-17-92 in both normal and pathological functions of the heart, and provides a model that may serve as a useful platform to test novel antiarrhythmic therapeutics.—Danielson, L. S., Park, D. S., Rotllan, N., Chamorro-Jorganes, A., Guijarro, M. V., Fernandez-Hernando, C., Fishman, G. I., Phoon, C. K. L., Hernando, E. Cardiovascular dysregulation of miR-17-92 causes a lethal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenesis.

Keywords: microRNA, mouse model, connexin43, Pten

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), small noncoding RNAs (1), have recently been shown to play essential roles in both cardiovascular development and function (2). Indeed, cardiac or smooth muscle-specific deletion of Dicer, an enzyme necessary for the production of almost all miRNAs, results in embryonic lethality (3, 4). Furthermore, individual miRNAs, such as miR-1 (3), miR-208 (5, 6), and miR-27b (7), play key roles in cardiac development and/or function, including morphogenesis, conduction, and cell proliferation within the heart. Studies have also implicated miR-126 (8, 9) and miR-143/145 (10–12) as active regulators of vascular development and differentiation. Moreover, miR-133a functions as a switch between cardiac and smooth muscle cell (SMC) types by affecting proliferation and differentiation markers (13). These studies begin to define the role of miRNAs in the development and maintenance of the cardiovascular system.

Several findings support a critical role for the miRNA cluster miR-17-92 in the development of cardiac and smooth muscle tissues. Expression studies have shown that members of this cluster are significantly down-regulated during differentiation of cardiomyocytes from human embryonic stem cells (14). In addition, data from our laboratory indicated decreased expression of cluster members during SMC differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (15). These data suggest that down-regulation of this cluster may be required for muscle cell differentiation. Furthermore, functional studies have found that germline deletion of this cluster in mice results in perinatal lethality from ventricular septal defects and underdeveloped lungs, indicating a critical function for miR-17-92 in cardiogenesis (16). More recent work has identified a role for miR-17-92 in bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling during early heart development (17), further highlighting the significance of this cluster in cardiogenesis. In regard to SMC development, miR-17-92 has been implicated in proliferation and differentiation of vascular SMCs in vivo (18). Together, these data suggest that strict regulation of miR-17-92 expression levels is required for normal cardiovascular development and function.

In this study we used a conditional knock-in strategy to constitutively overexpress miR-17-92 in developing and adult cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle tissues in mice. Mutant mice displayed a dose-dependent cardiomyopathy, which was associated with inducible arrhythmias and premature mortality. In addition, our data suggest that direct repression of the miR-17-92 targets Pten and connexin43 (Cx43) may contribute to the lethal phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal experimentation

Mice were bred and maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under protocol number 100108-02. Generation of mice overexpressing miR-17-92 in both cardiac and smooth muscle tissues was achieved by crossing miR-17-92TG/TG mice (ref. 19; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) with those expressing cre recombinase under the SM22α (transgelin, Tagln) promoter (ref. 20; Jackson Laboratory).

Tissue collection, gross examination, cell counts

Aged-matched littermates were sacrificed and examined for gross abnormalities, and tissues were collected for RNA, protein, and histological analyses. Hearts were perfused and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and frozen, or formalin fixed and paraffin embedded for immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry, respectively. Organs containing smooth muscle tissues were also collected and paraffin embedded for histology and immunohistochemistry. For analysis of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia, hearts were perfused with potassium chloride prior to formalin fixation and paraffin embedding. Individual cardiomyocyte cell numbers and surface area (N-cadherin and troponin staining used to guide surface area calculations) were measured and counted in a blinded fashion by two independent investigators using SlidePath Digital Image Hub software (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL,USA).

Molecular analyses

RNA analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tissues using miRNeasy RNA Isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as per manufacturer's protocol. RNA was reverse-transcribed (ABI TaqMan reverse transcription; Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then used for quantitative real-time PCR using FastStart SYBR Green MasterMix (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and Bio-Rad iCycler equipment (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). miRNA levels were detected using TaqMan miRNA Assay kit (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's protocol. The small RNA U6 was used for normalization. Primer sequences for quantitative real time PCR: PTEN forward 5′-TGTTCAGTGGCGGAACTTGC-3′, PTEN reverse 5′-TCCCGTCGTGTGGGTCCTGA-3′; mANF forward 5′-GCCGGTAGAAGATGAGGTCA-3′, mANF reverse 5′-GGGCTCCAATCCTGTCAATC-3′; mSKA forward 5′-GGCTCCCAGCACCATGAAGA-3′, mSKA reverse 5′-CAGCACGATTGTCGATTGTCG-3′; mbMHC forward 5′-GTGAAGGGCATGAGGAAGAGT-3′, mbMHC reverse 5′-AGGCCTTCACCTTCAGCTGC-3′; Cx43 forward 5′-GAGAGCCCGAACTCTCCTTT-3′, Cx43 reverse 5′-TGGAGTAGGCTTGGACCTTG-3′; GAPDH forward 5′-ACCGCCGTTATGAAATCTTG-3′, GAPDH reverse 5′-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3′.

Western blot analysis

Tissues were lysed in ice-cold 1% Nonidet P-40 buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and 0.25 mg/ml AEBSF (Roche). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phospho-(Ser473)-Akt 9271 (1:1000), Akt 4685 (1:1000), Cx43 3215 (1:1000), and PTEN 9552 (1:1000) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Mouse monoclonal Hsp-90 610419 (1:3000) antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Secondary antibodies were fluorophore-conjugated antibodies (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA). Bands were visualized by using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biotechnology).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Mouse tissues were formalin fixed and then paraffin embedded according to standard protocols. Immunohistochemistry was conducted following the standard avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase staining procedure. Diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen, and hematoxylin was used to counterstain the nuclei. Antibodies used were α-smooth muscle actin (NB600-531; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), PCNA (MS106; Neomarkers, Fremont, CA, USA), Cx43 (3215; Cell Signaling Technology), N-cadherin (3B9; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA), and troponin I (AB47003; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Analysis of heart function

Echocardiography

Mice were anesthetized with 1% isoflurane mixed with medical oxygen via nose cone, with strict thermoregulation (core temperature 37±1°C) to optimize physiological conditions and reduce hemodynamic variability (21, 22). Transthoracic echocardiography was performed in standard fashion as described previously (21), using a Vevo 2100 ultrasound system with a 40-MHz center frequency transducer (Visual Sonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). Analyses included left ventricular cavity and wall thickness measurements, aortic diameter (obtained at the largest diameter in the mid to distal ascending aorta). Basic cardiac rhythm could be determined by electrocardiographic limb leads on the warming pad on which the mouse lay, and was displayed with echocardiographic images simultaneously.

Electrocardiography and electrophysiology

Electrophysiological studies were performed as described previously with a 2F octapolar intracardiac catheter (23). Standard pacing protocols (single, double, and triple extrastimulation and burst pacing) were performed to test for ventricular tachycardia (VT) inducibility. Sustained VT was defined as ≥30 consecutive beats.

miRNA target validation

The Cx43 3′-UTR luciferase construct was purchased from Switchgear Genomics (Menlo Park, CA, USA), and luciferase assays were performed as per manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the luciferase empty vector or vector with Cx43 3′-UTR downstream of luciferase along with scrambled mimic control, miR19a/b, or nontargeting miRNA mimic (all mimics purchased from Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA, and used at 50 nM concentration) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 24 h post-transfection, luciferase activity was detected as per manufacture's protocol and read at a wavelength of 595 nm. Luciferase values were normalized to respective luciferase empty vector control. Experiments were performed a minimum of 3 times, with 4 technical replicates per experiment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier curves, and the log-rank test was used to determine differences in survival. Unpaired t tests were used to compare single data points. One-way ANOVA comparison was done for groups with an application of Newman-Kuels posttest to correct for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance in all analyses was defined as P < 0.05. Error bars correspond to sd among animals in all cases, except for 3′-UTR assays, where they represent experimental replicates.

RESULTS

Cardiovascular expression of miR-17-92 leads to increased heart size and premature death

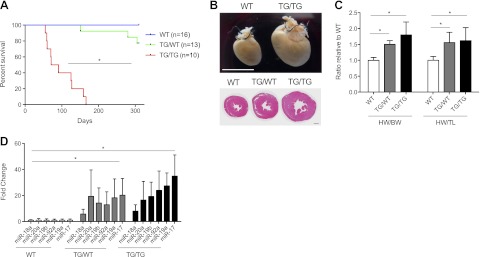

To study the effects of dysregulated miR-17-92 expression in developing cardiac and SMC lineages, we crossed ROSA26-lox-stop-lox-miR-17-92 (miR-17-92TG/TG; ref. 19) with Tagln (SM22a)-cre mice (20). Based on reporter analysis of Tagln promoter, these mice have constitutive overexpression of miR-17-92 starting in the myotomal component of the somites and in the bulbocordis region of the heart by embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5; ref. 20). After two generations, mice of all possible genotypes were born with the expected mendelian ratio. Homozygous, Tagln-cre+/miR-17-92TG/TG animals (hereafter, homozygous or TG/TG) appeared to develop normally until approximately 2 mo of age, at which time they began to die suddenly (mean survival 98.3±42.5 d, P<0.0001; Fig. 1A). Gross pathological examination demonstrated markedly enlarged hearts in homozygous animals, with the heterozygous transgenic/wild type (TG/WT) animals showing an intermediate phenotype (Fig. 1B). Heart weight (HW)/body weight (BW) and HW/tibia length (TL) ratios were significantly higher in both heterozygous and homozygous mutant mice compared to age-matched littermate controls (Fig. 1C). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of RNA from cardiac tissue demonstrated a statistically significant, albeit variable, increase in expression of all members of the miR-17-92 cluster in both heterozygous and homozygous mice (Fig. 1D). Neither heterozygous nor homozygous animals displayed overt signs of heart failure prior to death. Heterozygous animals, which had intermediate miR-17-92 expression, exhibited a less-severe phenotype with longer survival rates and a more modest increase in heart size compared to homozygous littermates. These data indicate a dose-dependent phenotypic effect of miR-17-92 overexpression on heart size and function. Notably, enlarged hearts with increased miR-17-92 expression levels were detected as early as 12 h after birth, suggesting a developmental cardiomyopathy (Supplemental Fig. S1A, B).

Figure 1.

MiR-17-92 overexpression leads to decreased survival and cardiac hypertrophy. A) Kaplan-Meier curve (days; median survival of TG/TG=82 d, mean=98.3±42.5 d, P<0.0001). B) Gross images of WT and TG/TG hearts at ∼2 mo of age (top panel, scale bar=1 cm). Histology images of cross sections of WT, TG/WT, and TG/TG hearts at ∼2 mo of age (bottom panel, scale bar=1 mm). C) HW/BW and HW/TL ratios (n=6/genotype). D) Quantitative PCR expression analysis of miR-17-92 for each member of the cluster in WT (n=7), TG/WT (n=6), and TG/TG (n=7) mice. Fold change is relative to the average of the respective WT sample. BW, body weight; HW, heart weight; TG/TG, transgenic/transgenic; TG/WT, transgenic/wild type; TL, tibia length. *P < 0.05.

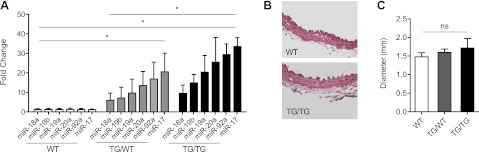

Ectopic expression of miR-17-92 does not cause major defects in smooth muscle tissues

Analysis of smooth muscle tissues revealed that ectopic expression of miR-17-92 in this lineage did not have a major phenotypic impact. While we detected a significant increase in miR-17-92 expression in aortic tissue in both heterozygous and homozygous animals (Fig. 2A), we did not observe any alterations in tissue architecture, or thickness of the smooth muscle layer (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, no significant increase in aortic diameter was observed (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. S1C).

Figure 2.

Ectopic expression of miR-17-92 does not cause major defects in aortic smooth muscle. A) Quantitative PCR expression analysis of miR-17-92 for each member of the cluster in WT (n=5), TG/WT (n=3), TG/TG (n=4) aorta samples. B) Hemtoxylin and eosin staining of aortic smooth muscle layer (×40). C) Echocardiographic measurements of aortic diameter in WT (n=5), TG/WT (n=5), TG/TG (n=5) animals. Fold change is relative to the average of the respective WT samples. *P < 0.05.

In addition, histological analysis of other smooth muscle containing organs such as the bladder, intestine, and myometrium did not reveal alterations in smooth muscle marker gene expression or thickness of the smooth muscle layer (data not shown, Supplemental Fig. S2).

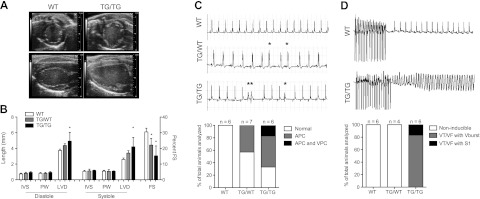

Constitutive miR-17-92 expression in the heart causes left ventricular dilation and decreased cardiac function

Echocardiography was performed on 1- to 3-mo-old animals to assess contractile performance and chamber dimensions (Supplemental Table S1). Homozygous animals (n=4) presented with increased left ventricular diameter (LVD) and decreased fractional shortening (FS) compared to WT mice (n=5), indicative of a dilated cardiomyopathy (Fig. 3A, B). Heterozygous animals (n=4) displayed a milder phenotype, with only the decrease in FS reaching statistical significance (Fig. 3B). This analysis was additionally performed in an aged cohort of animals, and a similar phenotype was found (Supplemental Fig. S3). Analysis of homozygous 12- to 24-h-old neonatal pups (n=4/group) demonstrated increased LVD at birth with normal systolic function (Supplemental Fig. S1C). These data demonstrate that overexpression of miR-17-92 in developing cardiomyocytes leads to left ventricular dilation seen as early as 12 h postnatally and impaired systolic function by 1 mo of age.

Figure 3.

Constitutive miR-17-92 expression in cardiomyocytes causes defective heart function and arrhythmogenic susceptibility. A) Representative parasternal short axis (top panel) and long axis (bottom panel) echocardiographic images of WT and TG/TG animals. B) Echocardiographic measurements of young WT (n=5), TG/WT (n=5), TG/TG (n=4) cohorts. C) Representative surface electrocardiograms (lead II) of normal (WT, top panel), atrial premature contractions (APCs; TG/WT, middle panel), and ventricular premature contractions (VPCs) with ventricular couplets (TG/TG, lower panel). Histogram represents percentage of arrhythmogenic phenotypes observed in each cohort. Asterisks indicate premature contractions. D) Representative surface electrocardiograms of WT animals (top panel) resuming normal rhythm after burst pacing, and TG/TG mouse (bottom panel) deteriorating into sustained VT or ventricular fibrillation (VF) after burst pacing or with a single extrastimuli. Histogram represents percentage of each genotype demonstrating noninducibility, VT/VF during burst pacing (Vburst) or VT/VF during a single extrastimuli (S1). FS, fractional shortening; IVS, interventricular septum; LVD, left ventricular diameter; PW, posterior wall. *P < 0.05.

miR-17-92 dysregulation leads to spontaneous cardiac arrhythmia

During echocardiography, we observed irregular cardiac rhythm in mutant animals. This finding, coupled with the sudden death of homozygous animals without overt signs of heart failure, suggested that cardiac arrhythmia might be the cause of death in these mice. To test this possibility, we obtained electrocardiograms (ECGs) on 1- to 3-mo-old mice. Such studies revealed that heterozygous and homozygous animals displayed a significant increase in atrial and ventricular ectopy. While no arrhythmias were seen in WT littermate controls (n=6), 3 of 7 heterozygous animals demonstrated isolated atrial premature contractions (APCs; Fig. 3C). Furthermore, a majority (4 out of 6) of homozygous animals displayed spontaneous APCs, ranging from rare to frequent (Fig. 3C). In addition, one animal exhibited frequent ventricular premature contractions (VPCs) as well as ventricular couplets (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these ECG data demonstrate that constitutive overexpression of miR-17-92 results in an increase in atrial and ventricular ectopy, in addition to dilated cardiomyopathy.

Constitutive expression of miR-17-92 increases arrhythmia susceptibility

Programmed electrophysiological study (EPS) was performed to evaluate the degree of arrhythmia susceptibility in miR-17-92 overexpressing mouse lines. Strikingly, all homozygous animals (n=6) developed sustained and lethal VT or ventricular fibrillation (VF) following programmed electrical stimulation with either a single extrastimulus (n=1) or ventricular burst protocol (n=5) (Fig. 3D). In contrast, none of the WT or heterozygous animals displayed sustained ventricular arrhythmias during EPS (n=6 and n=4, respectively; Fig. 3D). The observation of spontaneous atrial and ventricular arrhythmias and inducible sustained VT or VF during EPS in homozygous animals strongly supports the hypothesis that lethal arrhythmias are the cause of sudden death of homozygous mutant mice.

Hearts with constitutive miR-17-92 expression show increased cardiomyocyte number and size

Histological analyses of heart tissues from 1- to 3-mo-old homozygous animals with overexpression of miR-17-92 revealed minimal myocyte disarray, with no detectable proliferation, as assessed by staining for phosphorylated histone H3 (Fig. 4A). Histological analysis found no evidence of fibrosis, as assessed by Masson's trichrome staining (Supplemental Fig. S4A). In addition, expression of fetal cardiac genes displayed a variable upward trend in the homozygous and heterozygous animals (Supplemental Fig. S4B). These data indicate no significant evidence of chronic heart failure in these animals.

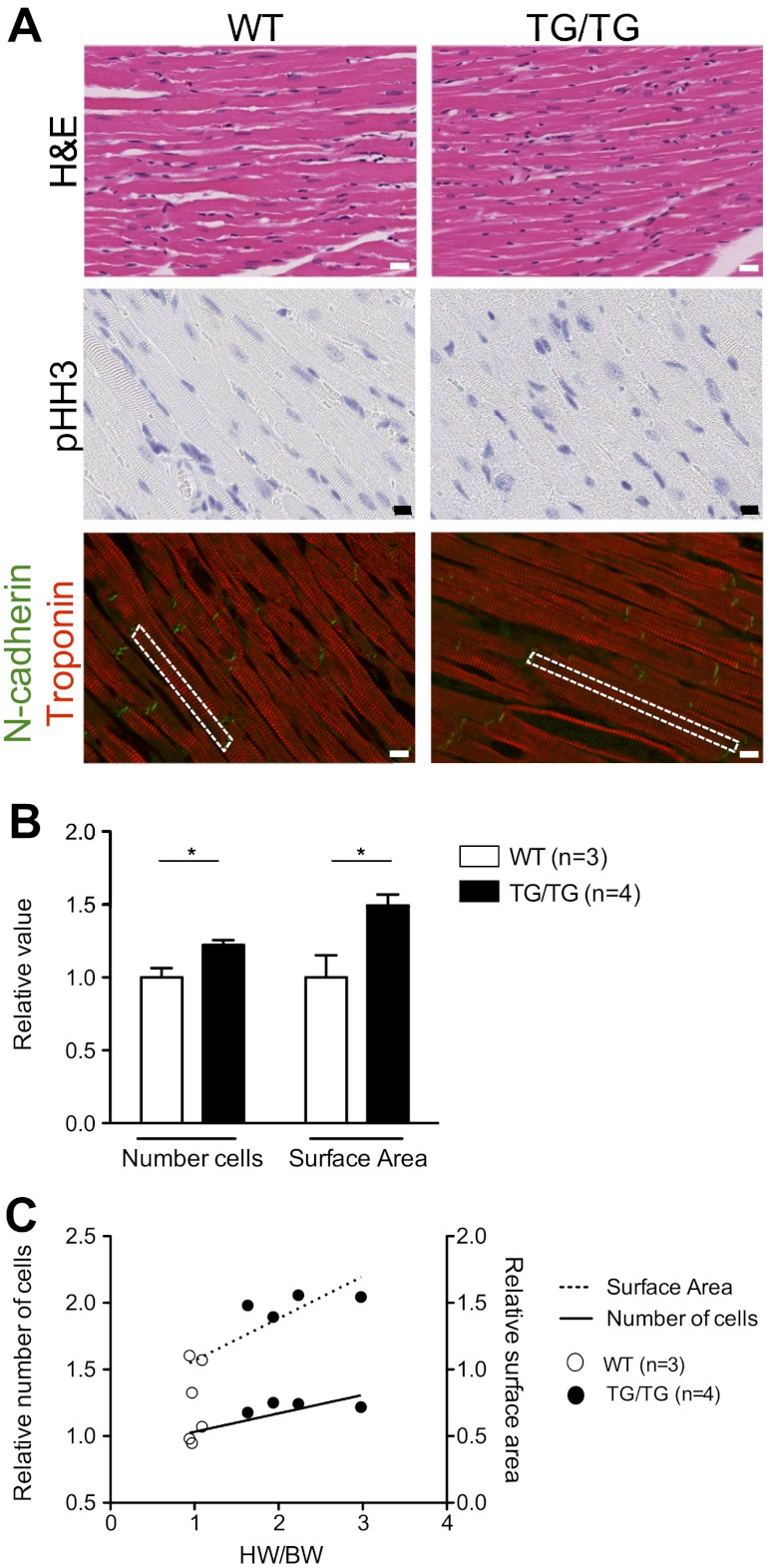

Figure 4.

Mir-17-92 overexpression in cardiomyocytes results in hyperplasia and hypertrophy. A) Representative images of 1- to 3-mo-old WT and TG/TG animals: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images depicting myocyte arrangement and density of cells in left ventricle free wall (top panel, scale bar=25 μm), phosphorylated histone H3 (pHH3; middle panel, scale bar=10 μm), and N-cadherin (green) and troponin (red) (bottom panel, scale bar=10 μm). Dashed outline indicates a representative single cardiomyocyte. B) Average number of cardiomyocytes counted across left ventricle free wall and surface area measured in TG/TG (n=4) vs. WT (n=3). Values are relative to average of WT counts. Error bars represent deviation among individual animals. C) Scatter plot of relative HW/BW ratios, cell number (solid line), and surface area (hashed line) of individual WT (n=3, open circles) and TG/TG (n=4, solid circles). Linear regression lines demonstrate significant correlation between HW/BW and cell number (P=0.020) and surface area (0.0162). *P < 0.05.

However, when we assessed cardiomyocyte cell size and number in 1- to 3-mo-old homozygotes, we observed a significant increase in both the number and size of individual cardiomyocytes in the left ventricle free wall (Fig. 4). Furthermore, cardiomyocyte number and surface area were found to correlate with heart size, suggesting both may contribute to the overall hypertrophic state of the hearts (Fig. 4C). The presence of increased myocyte number without evidence of active proliferation in the adult hearts, in addition to the cardiac hypertrophy apparent in neonatal animals, suggests that cardiac hyperplasia likely occurred during development.

Expression levels of Pten and Cx43, a novel target of miR-19a/b, are suppressed in cardiac tissues with miR-17-92 overexpression

The lipid phosphatase Pten, an inhibitor of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, is a prominent miR-17-92 target that plays a key role in regulation of cardiomyocyte size and contractility (24). Indeed, we found that expression of Pten was reduced with concomitant up-regulation of phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) in transgenic hearts (Fig. 5A, B). Notably, Pten mRNA expression inversely correlated with miR-17-92 levels (R2=0.73, P<0.0001), which directly correlated with heart size (R2=0.85, P=0.002) (Fig. 5C), suggesting a mechanistic role for Pten repression in the observed hypertrophic phenotype. Moreover, heterozygous animals demonstrated an intermediate phenotype, with less pronounced Pten suppression and more modest heart enlargement, consistent with a dose-dependent effect of miR-17-92.

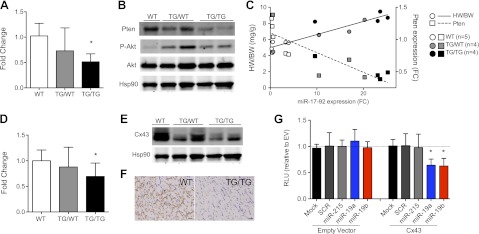

Figure 5.

Pten and Cx43, a novel target, are possible mediators of hypertrophic and arrhythmogenic phenotype. A) Quantitative PCR expression analysis of Pten in WT (n=5), TG/WT (n=4), TG/TG (n=4) cardiac tissues. Fold change is relative to average of WT control. B) Western blot analysis of Pten, Akt, and phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) in heart tissues from 3-mo-old animals. Hsp90 was used as loading control. C) Scatter plot of average miR-17-92 fold change (FC) plotted vs. HW/BW ratios (circles) and Pten expression levels (squares). Linear regression lines demonstrate a significant correlation between miR-17-92 levels and HW/BW ratio (P<0.0001) and inverse correlation with Pten levels (P=0.0002). *P < 0.05. D) Quantitative PCR expression analysis of Cx43 in WT (n=7), TG/WT (n=6), TG/TG (n=7) cardiac tissues. Fold change is relative to average of WT control. E) Western blot analysis of Cx43 expression in cardiac tissues of 3-mo-old animals. F) Representative immunohistochemistry images of Cx43 in WT vs. TG/TG hearts (scale bar=25 μm). G) Reporter assays with cotransfection of empty vector (EV) or Cx43 3′-UTR and mock transfected, scrambled (SCR) sequence oligonucleotide, nontargeting miRNA (miR-215) mimic, miR-19a mimic, or miR-19b mimic. RLU, relative luciferase units. Error bars represent deviation among experimental replicates. *P < 0.05.

We next sought to identify a novel target of miR-17-92 that could account for the arrhythmogenic phenotype. Cx43, a gap junction protein known to play a key role in normal cardiac conduction (25), was a predicted target of miR-17-92 cluster members, miR-19a/b. Therefore, suppression of Cx43 by overexpression of miR-17-92 in our mouse model could account for, or contribute to, the observed cardiac arrhythmias. In support of this hypothesis, Cx43 mRNA and protein expression were significantly down-regulated in homozygous mutant animals compared to controls (Fig. 5D–F). Moreover, cotransfection of a 3′-UTR luciferase reporter with miR-19a or miR-19b oligonucleotides significantly reduced luciferase activity relative to controls, demonstrating that these miRNA directly target Cx43 (Fig. 5G).

Taken together, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that overexpression of miR-17-92 may lead simultaneously to cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenesis by directly repressing two distinct targets: Pten, a regulator of heart size, and Cx43, a key regulator of cardiac rhythmicity.

DISCUSSION

Precise temporal and spatial control of miRNA expression is essential for normal development and tissue homeostasis. Here, using a conditional transgenic system, we demonstrate that overexpression of miR-17-92 in cardiomyocytes starting at E9.5 results in a severe cardiomyopathy culminating in sudden cardiac death. Moreover, our data indicate that two direct targets of miR-17-92, Pten and the novel target Cx43, may confer, at least in part, this deleterious phenotype. Interestingly, and in stark contrast to the results in the cardiac lineage, persistent expression of miR-17-92 in vascular SMCs appears well tolerated, with no obvious phenotype.

The miR-17-92 cluster has important roles in a variety of normal biological processes, such as lung (26) and lymphocyte (19) development, and contributes to many aspects of tumor biology (reviewed in ref. 27). The importance of miR-17-92 in cardiac development was first suggested by a report showing that deletion of this cluster resulted in ventricular septal defects (16). More recent work has exhibited a role for miR-17-92 in BMP signaling during development of the cardiac outflow tract (17). In addition, individual members of this cluster were also found dysregulated in several mouse models of cardiomyopathy. Inhibition of miR-17 after hypoxia-induced hypertension rescued right ventricle hypertrophy (28). Moreover, miR-18 and miR-19 were down-regulated in models of age-related heart failure (29). These data support a requirement for strict regulation of miR-17-92 expression to maintain normal heart function.

Here we demonstrate that overexpression of miR-17-92 in the developing cardiovascular system results in a lethal hypertrophic and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. The hypertrophic phenotype appears to result, at least in part, from repression of Pten, a known target of miR-17-92, as we observed a significant inverse correlation between Pten levels and heart size. These data are partially in accordance with published work that found hypertrophy and decreased contractility on cardiac specific loss of Pten, via muscle creatine kinase driven cre recombinase (24). However, striking differences are apparent between these models. In addition to the cardiomyocyte hypertrophy observed in both cases, we have also observed cellular hyperplasia with miR-17-92 overexpression. Moreover, our model displayed spontaneous arrhythmias and a dramatically decreased rate of survival, two phenotypes not observed on Pten deletion alone. These disparities may be due to the following reasons: complete deletion of Pten vs. partial suppression; pleiotropic effects of miR-17-92 by direct targeting of other transcripts, including Cx43; and spatiotemporal variances in expression of cre recombinase between the two promoters used in these studies.

A recent report in which Tsc1 was conditionally deleted using the Tagln-cre animals used in our model supports our hypothesis that Tagln-cre-mediated miR-17-92 overexpression may be causing an mTOR-mediated hypertrophy (30). Tsc1 is a negative regulator of mTOR signaling downstream of Pten (31), and conditional loss of Tsc1 results in cardiac hypertrophy, similar to our model and that of cardiac deletion of Pten. In contrast to cardiac deletion of Pten, however, deletion of Tsc1 or overexpression of miR-17-92 results in reduced survival. Furthermore, Tsc1 loss and ectopic expression of miR-17-92 also results in enlarged hearts present at birth and cardiomyocyte hyperplasia in the adult heart without evidence of proliferation. These findings support the possibility that Tagln-cre-mediated Tsc1 deletion or miR-17-92 overexpression impacts cellular proliferation during development. Treatment of Tagln-cre+, Tsc1−/− mice with rapamycin results in partial regression of cardiac enlargement and increased survival, thus suggesting that mTOR-mediated cardiac hypertrophy contributes to the lethal phenotype. Our correlative data suggests that the hypertrophic phenotype may be mediated by mTOR activation via Pten repression, which may partially contribute to the reduced survival. It is likely, however, that the lethal phenotype is a combination of pathologies as our data also demonstrates that miR-17-92 targets Cx43 in cardiomyocytes, which may directly impact rhythmic activity.

Previously published work has demonstrated that cardiac specific deletion of Cx43 results in a structurally normal heart but sudden death between 3 and 4 wk of age (25). EPS demonstrated that these mutant mice died from spontaneous ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Although we did not carry out telemetric recordings, our data suggest that the premature lethality in miR-17-92 overexpressing mice may also result from arrhythmic events. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that homozygous animals have significant repression of Cx43, spontaneous atrial and ventricular ectopy, and easily inducible VT or VF during EPS. Although cardiac hypertrophy in the homozygous animals may be contributing to the arrhythmogenic phenotype, identification of Cx43 as a novel target of this cluster points to the possibility that direct suppression of this transcript by miR-17-92 in heart tissues may be a key contributing factor in the sudden death of these animals.

In contrast to the profound phenotype observed in the cardiac lineage, we did not detect a frank defect in smooth muscle tissues in our model. These findings suggest that, unlike cardiac development, tight regulation of miR-17-92 is not required for SMC maturation. It is possible, however, that a higher threshold of miR-17-92 expression is required to impact smooth muscle development and function.

In summary, cardiovascular overexpression of miR-17-92 leads to a severe hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death, with minimal effects on smooth muscle tissues. Our data suggest that miR-17-92 regulates heart size via its repression of Pten and cardiac impulse propagation by modulation of Cx43. This study supports the importance of tightly regulated expression of the miR-17-92 cluster during cardiac development and suggests that aberrant miR-17-92 expression may play a role in disorders of cardiac morphogenesis and rhythmicity. Moreover, this transgenic model may be a useful platform to test novel antiarrhythmic therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fang-Yu Liu for technical assistance, and the Experimental Pathology Core resource, partially supported by the New York University (NYU) Cancer Institute Cancer Center, support grant 5P30CA016087-32. This work was partially funded by the NYU–Health and Hospitals Corp. Clinical and Translational Science Institute [which is supported in part by grant UL1 TR000038 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH)], NIH/National Center for Research Resources 1ULIRR029893, the Liddy Shriver Sarcoma Initiative, the LMS Direct Research Foundation, Edna's Foundation of Hope to E.H., NIH grants R01HL82727 and S10RR026881 to G.I.F., and NIH grants R01HL106063 and R01HL107953 to C.F.-H.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- APC

- atrial premature contraction

- BW

- body weight

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- Cx43

- connexin43

- E

- embryonic day

- ECG

- electrogardiogram

- EPS

- electrophysiological study

- FS

- fractional shortening

- HW

- heart weight

- LVD

- left ventricular diameter

- miR

- microRNA

- miRNA

- microRNA

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- TG/TG

- transgenic/transgenic (homozygous)

- TG/WT

- transgenic/wild type (heterozygous)

- TL

- tibia length

- VF

- ventricular fibrillation

- VPC

- ventricular premature contraction

- VT

- ventricular tachycardia

- WT

- wild type

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartel D. (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen J., Wang D.-Z. (2012) microRNAs in cardiovascular development. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 52, 949–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao Y., Ransom J., Li A., Vedantham V., von Drehle M., Muth A., Tsuchihashi T., McManus M., Schwartz R., Srivastava D. (2007) Dysregulation of cardiogenesis, cardiac conduction, and cell cycle in mice lacking miRNA-1-2. Cell 129, 303–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Albinsson S., Suarez Y., Skoura A., Offermanns S., Miano J., Sessa W. (2010) MicroRNAs are necessary for vascular smooth muscle growth, differentiation, and function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vascul. Biol. 30, 1118–1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Rooij E., Sutherland L., Qi X., Richardson J., Hill J., Olson E. (2007) Control of stress-dependent cardiac growth and gene expression by a microRNA. Science 316, 575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callis T., Pandya K., Seok H., Tang R.-H., Tatsuguchi M., Huang Z.-P., Chen J.-F., Deng Z., Gunn B., Shumate J., Willis M., Selzman C., Wang D.-Z. (2009) MicroRNA-208a is a regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and conduction in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2772–2858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang J., Song Y., Zhang Y., Xiao H., Sun Q., Hou N., Guo S., Wang Y., Fan K., Zhan D., Zha L., Cao Y., Li Z., Cheng X., Zhang Y., Yang X. (2011) Cardiomyocyte overexpression of miR-27b induces cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in mice. Cell Res. 22, 516–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang S., Aurora A., Johnson B., Qi X., McAnally J., Hill J., Richardson J., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. (2008) The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev. Cell. 15, 261–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuhnert F., Mancuso M., Hampton J., Stankunas K., Asano T., Chen C.-Z., Kuo C. (2008) Attribution of vascular phenotypes of the murine Egfl7 locus to the microRNA miR-126. Development 135, 3989–4082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xin M., Small E., Sutherland L., Qi X., McAnally J., Plato C., Richardson J., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. (2009) MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes Dev. 23, 2166–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boettger T., Beetz N., Kostin S., Schneider J., Krüger M., Hein L., Braun T. (2009) Acquisition of the contractile phenotype by murine arterial smooth muscle cells depends on the Mir143/145 gene cluster. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2634–2681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elia L., Quintavalle M., Zhang J., Contu R., Cossu L., Latronico M., Peterson K., Indolfi C., Catalucci D., Chen J., Courtneidge S., Condorelli G. (2009) The knockout of miR-143 and -145 alters smooth muscle cell maintenance and vascular homeostasis in mice: correlates with human disease. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1590–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu N., Bezprozvannaya S., Williams A., Qi X., Richardson J., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. (2008) microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev. 22, 3242–3296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson K., Hu S., Venkatasubrahmanyam S., Fu J.-D., Sun N., Abilez O., Baugh J., Jia F., Ghosh Z., Li R., Butte A., Wu J. (2010) Dynamic microRNA expression programs during cardiac differentiation of human embryonic stem cells: role for miR-499. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 426–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Danielson L., Menendez S., Attolini C., Guijarro M., Bisogna M., Wei J., Socci N., Levine D., Michor F., Hernando E. (2010) A differentiation-based microRNA signature identifies leiomyosarcoma as a mesenchymal stem cell-related malignancy. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 908–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ventura A., Young A., Winslow M., Lintault L., Meissner A., Erkeland S., Newman J., Bronson R., Crowley D., Stone J., Jaenisch R., Sharp P., Jacks T. (2008) Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell 132, 875–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang J., Greene S., Bonilla-Claudio M., Tao Y., Zhang J., Bai Y., Huang Z., Black B., Wang F., Martin J. (2010) Bmp signaling regulates myocardial differentiation from cardiac progenitors through a MicroRNA-mediated mechanism. Dev. Cell 19, 903–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen Z., Wu J., Yang C., Fan P., Balazs L., Jiao Y., Lu M., Gu W., Li C., Pfeffer L., Tigyi G., Yue J. (2012) DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8(DGCR8)-mediated miRNA biogenesis is essential for vascular smooth muscle cell development in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 19018–19028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xiao C., Srinivasan L., Calado D., Patterson H., Zhang B., Wang J., Henderson J., Kutok J., Rajewsky K. (2008) Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat. Immunol. 9, 405–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lepore J., Cheng L., Min Lu M., Mericko P., Morrisey E., Parmacek M. (2005) High-efficiency somatic mutagenesis in smooth muscle cells and cardiac myocytes in SM22alpha-Cre transgenic mice. Genesis 41, 179–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collis L., Meyers M., Zhang J., Phoon C., Sobie E., Coetzee W., Fishman G. (2007) Expression of a sorcin missense mutation in the heart modulates excitation-contraction coupling. FASEB J. 21, 475–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nomura-Kitabayashi A., Phoon C., Kishigami S., Rosenthal J., Yamauchi Y., Abe K., Yamamura K.-i., Samtani R., Lo C., Mishina Y. (2009) Outflow tract cushions perform a critical valve-like function in the early embryonic heart requiring BMPRIA-mediated signaling in cardiac neural crest. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, 617–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maguire C., Wakimoto H., Patel V., Hammer P., Gauvreau K., Berul C. (2003) Implications of ventricular arrhythmia vulnerability during murine electrophysiology studies. Physiol. Genomics 15, 84–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crackower M., Oudit G., Kozieradzki I., Sarao R. (2002) Regulation of myocardial contractility and cell size by distinct PI3K-PTEN signaling pathways. Cell 110, 737–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gutstein D. E., Morley G. E., Tamaddon H., Vaidya D., Schneider M. D., Chen J., Chien K. R., Stuhlmann H., Fishman G. I. (2001) Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ. Res. 88, 333–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu Y., Thomson J., Wong H., Hammond S., Hogan B. (2007) Transgenic over-expression of the microRNA miR-17-92 cluster promotes proliferation and inhibits differentiation of lung epithelial progenitor cells. Dev. Biol. 310, 442–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Olive V., Jiang I., He L. (2010) mir-17-92, a cluster of miRNAs in the midst of the cancer network. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 1348–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pullamsetti S., Doebele C., Fischer A., Savai R., Kojonazarov B., Dahal B., Ghofrani H., Weissmann N., Grimminger F., Bonauer A., Seeger W., Zeiher A., Dimmeler S., Schermuly R. (2011) Inhibition of microRNA-17 improves lung and heart function in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185, 409–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van Almen G., Verhesen W., van Leeuwen R., van de Vrie M., Eurlings C., Schellings M., Swinnen M., Cleutjens J., van Zandvoort M., Heymans S., Schroen B. (2011) MicroRNA-18 and microRNA-19 regulate CTGF and TSP-1 expression in age-related heart failure. Aging Cell 10, 769–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malhowski A., Hira H., Bashiruddin S., Warburton R., Goto J., Robert B., Kwiatkowski D., Finlay G. (2011) Smooth muscle protein-22-mediated deletion of Tsc1 results in cardiac hypertrophy that is mTORC1-mediated and reversed by rapamycin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 1290–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tomasoni R., Mondino A. (2011) The tuberous sclerosis complex: balancing proliferation and survival. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 466–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]