Abstract

Objective

Short-term declines in postmenopausal hormone use were observed following the Women’s Health Initiative trial results in 2002. While concerns about the trial’s generalizability have been expressed, long-term trends in hormone use in a nationally representative sample have not been reported. We sought to evaluate national trends in the prevalence of hormone use, and assess variation by type of formulation and patient characteristics.

Methods

We examined postmenopausal hormone use during 1999–2010 using cross-sectional data on 10,107 women aged 40 years and older in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Results

In 1999–2000, the prevalence of oral postmenopausal hormone use was 22.4% (95% CI: 19.0, 25.8) overall, 16.8% (95% CI: 14.2, 19.3) for estrogen only, and 5.2% (95% CI: 3.6, 6.8) for estrogen plus progestin. A sharp decline in use of all formulations occurred in 2003–2004, when the overall prevalence dropped to 11.9% (95% CI: 9.6, 14.2). This decline was initially limited to non-Hispanic whites; use among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics did not decline substantially until 2005–2006. Hormone use continued to decline through 2009–2010 across all patient demographic groups, with the current prevalence now at 4.7% (95% CI: 3.3, 6.1) overall, 2.9% (95% CI: 2.1, 3.7) for estrogen only, and 1.5% (95% CI: 0.5, 2.5) for estrogen plus progestin. Patient characteristics currently associated with hormone use include history of hysterectomy, non-Hispanic white race or ethnicity, and income.

Conclusions

Postmenopausal hormone use in the United States has declined in a sustained fashion to very low levels across a wide variety of patient subgroups.

INTRODUCTION

Postmenopausal hormone use achieved widespread popularity in the late 20th century. The annual number of dispensed prescriptions for postmenopausal hormone therapy rose from 16 million in 1966 to 90 million in 1999 (1–4). In the late 1990s, the prevalence of current postmenopausal hormone use exceeded 40% among women aged 50–69 years in various health maintenance organizations (5–7). Nationally representative data from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicated that approximately one quarter of US women aged 45–74 were current users of postmenopausal hormones (8).

In 2002, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) published unfavorable results from a large randomized trial of combined estrogen plus progestin, demonstrating that on average the health risks of this type of postmenopausal hormone use exceeded the benefits (9). Analyses of NHANES data revealed that the prevalence of postmenopausal hormone use among women aged 45–74 subsequently declined by about 50% between 1999–2002 and 2003–2004 (8, 10).

The purpose of this study was to perform a closer examination of the changing patterns of postmenopausal use in the United States. In particular, we sought to determine whether the short term decline in postmenopausal hormone use following the publication of the WHI results has been sustained and whether the prevalence of estrogen only hormone use and estrogen plus progestin hormone use have changed in a similar fashion. To accomplish these objectives and to provide current estimates of hormone use in the United States, we used data from NHANES surveys conducted between 1999 and 2010.

METHODS

NHANES is a program of studies conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), designed to assess the health of adults and children in the United States (11). NHANES began in the early 1960s as a series of periodic surveys and examinations. In 1999, NHANES became a continuous survey which releases data in two year increments. Since its inception NHANES has used a complex cluster sampling method to create a sample population from which nationally representative estimates can be produced. The University of Vermont Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt from human subjects review.

The reproductive health module of the NHANES questionnaire began collecting data on postmenopausal hormone use according to preparation type (estrogen only, estrogen plus progestin, and progestin only) in 1999. In 1999, questions on postmenopausal hormone use were asked of women who had not had regular periods in the past 12 months. Between 2001 and 2010, these questions were asked of all women over the age of 20 years. Participants were first asked whether they had ever used female hormones such as estrogen and progestin, excluding birth control. They were then asked to provide details regarding the form of hormone delivery that they had used (pills, patches, creams, suppositories, or injections). For each form of hormone delivery used, women were asked to report if they had ever used that form containing estrogen only, estrogen plus progestin, or progestin only. For each type of preparation reported, the participant was asked to report the total duration of use and whether or not she was taking that preparation type now.

Data on covariates of interest were obtained from NHANES demographics files, which include self-reported information collected from participants during interviews. These included age, hysterectomy status, race/ethnicity, education, and income-to-poverty ratio. A positive history of hysterectomy included complete, total, and partial hysterectomies. The income-to-poverty ratio is calculated by NHANES as the ratio of family income to the poverty threshold, such that higher values indicate greater socioeconomic status.

All analyses were restricted to women over the age of 40 years, leaving a total sample size of 10,107 women. The sample size available for analysis is shown in Table 1. All analyses were restricted to oral hormone use (i.e., pills), since detailed data (e.g., estrogen only vs. estrogen plus progestin) was not available throughout the study period on use of patches, creams, suppositories, and injections. Women who reported that they were now taking pills containing the specific hormone preparation (estrogen only, estrogen plus progestin, or progestin only) were considered current users.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Female Adults Aged 40 Years or Older Who Completed the Reproductive Health Module, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010

|

1999–2000 n = 1,471 n (%) |

2001–2002 n = 1,583 n (%) |

2003–2004 n = 1,579 n (%) |

2005–2006 n = 1,453 n (%) |

2007–2008 n = 1,971 n (%) |

2009–2010 n = 2,050 n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 40–49 | 378 (25.7) | 436 (27.5) | 383 (24.3) | 412 (28.4) | 490 (24.9) | 582 (28.4) |

| 50–59 | 288 (19.6) | 321 (20.3) | 296 (18.7) | 315 (21.7) | 438 (22.2) | 444 (21.7) |

| 60–69 | 378 (25.7) | 360 (22.7) | 377 (23.9) | 327 (22.5) | 486 (24.7) | 477 (23.3) |

| 70–79 | 257 (17.5) | 252 (15.9) | 269 (17.0) | 215 (14.8) | 351 (17.8) | 341 (16.6) |

| 80 or older | 170 (11.6) | 214 (13.5) | 254 (16.1) | 184 (12.7) | 206 (10.5) | 206 (10.0) |

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 647 (44.0) | 887 (56.0) | 868 (55.0) | 781 (53.8) | 958 (48.6) | 1012 (49.4) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 288 (19.6) | 301 (19.0) | 301 (19.1) | 345 (23.7) | 414 (21.0) | 361 (17.6) |

| Hispanic | 491 (33.4) | 344 (21.7) | 346 (21.9) | 269 (18.5) | 528 (26.8) | 572 (27.9) |

| Other or unknown | 45 (3.1) | 51 (3.2) | 64 (4.1) | 58 (4.0) | 71 (3.6) | 105 (5.1) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 647 (44.0) | 501 (31.6) | 519 (32.9) | 399 (27.5) | 655 (33.2) | 652 (31.8) |

| High school diploma | 335 (22.8) | 374 (23.6) | 428 (27.1) | 362 (24.9) | 489 (24.8) | 458 (22.3) |

| Some college | 304 (20.7) | 433 (27.4) | 406 (25.7) | 404 (27.8) | 478 (24.3) | 562 (27.4) |

| College degree | 180 (12.2) | 272 (17.2) | 222 (14.1) | 284 (19.5) | 345 (17.5) | 368 (18.0) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 10 (0.5) |

| Income-to-poverty ratio | ||||||

| Less than 1 | 260 (17.7) | 226 (14.3) | 255 (16.1) | 205 (14.1) | 343 (17.4) | 389 (19.0) |

| Between 1 and 2 | 354 (24.1) | 373 (23.6) | 437 (27.7) | 378 (26.0) | 518 (26.3) | 514 (25.1) |

| Between 2 and 5 | 412 (28.0) | 522 (33.0) | 558 (35.3) | 510 (35.1) | 614 (31.2) | 614 (30.0) |

| 5 or more | 211 (14.3) | 321 (20.3) | 225 (14.2) | 282 (19.4) | 298 (15.1) | 304 (14.8) |

| Unknown | 234 (15.9) | 141 (8.9) | 104 (6.6) | 78 (5.4) | 198 (10.0) | 229 (11.2) |

Statistical analyses to estimate the prevalence of postmenopausal hormone use were performed using SAS Statistical Software (Version 9; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). The SAS Survey procedures were used to generate prevalence estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) that accounted for the stratified cluster sample design, unequal probability of sampling, and nonresponse. With the exception of age-specific results, all prevalence values were age-adjusted to the year 2000 US Standard Population, ages 40 years and older. Statistical tests for trends in the age-adjusted prevalence of hormone use over time (Ptrend) were conducted using Joinpoint software with a log-linear model (12, 13).

RESULTS

In 1999–2000, current use of oral postmenopausal hormones was reported by 22.4% (95% CI: 19.0, 25.8) of women aged 40 years and older (Table 2). Current use of estrogen only was reported by 16.8% (95% CI: 14.2, 19.3), whereas 5.2% (95% CI: 3.6, 6.8) reported current use of estrogen plus progestin. The prevalence of hormone use remained similar in 2001–2002, but declined dramatically in 2003–2004, when only 11.9% (95% CI: 9.6, 14.2) of women aged 40 and older reported current use of oral postmenopausal hormones. Sharp declines in use of estrogen only and estrogen plus progestin preparations were both observed during 2003–2004. The prevalence of current use continued to decline in subsequent years for both types of preparations. Prevalence of current use in the most recent study period (2009–2010) was 4.7% (95% CI: 3.3, 6.1) for any type, 2.9% (95% CI: 2.1, 3.7) for estrogen only, and 1.5% (95% CI: 0.5, 2.5) for estrogen plus progestin.

Table 2.

Percent of Women Aged 40 and Older Reporting Current Use of Oral Postmenopausal Hormones, by Age and Study Period, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010

| 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | Ptrend | |

| Any formulation | |||||||||||||

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||||

| 40 or older* | 22.4 | 19.0, 25.8 | 22.4 | 19.6, 25.3 | 11.9 | 9.6, 14.2 | 6.2 | 4.8, 7.7 | 5.6 | 4.1, 7.1 | 4.7 | 3.3, 6.1 | 0.004 |

| 40–49 | 12.3 | 8.0, 16.6 | 12.1 | 7.6, 16.6 | 5.8 | 3.8, 7.8 | 5.3 | 1.0, 9.6 | 3.4 | 1.3, 5.5 | 2.5 | 0.6, 4.3 | |

| 50–59 | 38.3 | 30.1, 46.5 | 32.5 | 25.9, 39.1 | 18.6 | 11.5, 25.6 | 10.0 | 6.5, 13.5 | 4.9 | 1.1, 8.7 | 6.7 | 2.5, 10.9 | |

| 60–69 | 29.0 | 22.4, 35.5 | 37.2 | 31.9, 42.5 | 19.4 | 14.6, 24.3 | 6.8 | 2.3, 11.3 | 9.7 | 4.5, 14.9 | 7.1 | 2.3, 11.8 | |

| 70–79 | 20.9 | 11.7, 30.2 | 19.8 | 13.9, 25.7 | 9.0 | 5.3, 12.8 | 3.4 | 0.0, 6.9 | 7.8 | 3.8, 11.9 | 5.0 | 1.9, 8.1 | |

| 80 or older | 6.6 | 2.9, 10.4 | 11.8 | 6.0, 17.5 | 7.9 | 4.4, 11.4 | 1.7 | 1.1, 2.3 | 3.9 | 1.1, 6.8 | 2.1 | 0.0, 4.4 | |

| Estrogen only | |||||||||||||

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||||

| 40 or older* | 16.8 | 14.2, 19.3 | 16.3 | 13.8, 18.8 | 9.1 | 7.1, 11.0 | 4.8 | 0.8, 1.5 | 4.3 | 3.3, 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.1, 3.7 | 0.001 |

| 40–49 | 9.9 | 5.8, 13.9 | 8.2 | 4.5, 12.0 | 5.2 | 3.3, 7.1 | 4.3 | 0.2, 8.4 | 3.2 | 1.1, 5.2 | 1.5 | 0.1, 2.9 | |

| 50–59 | 25.5 | 19.4, 31.7 | 19.8 | 14.7, 24.9 | 12.1 | 7.8, 16.3 | 7.5 | 4.3, 10.6 | 3.1 | 0.4, 5.8 | 2.3 | 0.1, 4.6 | |

| 60–69 | 22.9 | 17.3, 28.4 | 32.0 | 26.6, 37.5 | 15.0 | 10.1, 20.0 | 4.5 | 1.2, 7.9 | 5.8 | 3.0, 8.5 | 5.6 | 2.1, 9.2 | |

| 70–79 | 17.9 | 9.2, 26.6 | 15.7 | 9.8, 21.6 | 7.5 | 4.1, 10.9 | 2.6 | 0.0, 5.3 | 7.8 | 3.8, 11.8 | 4.5 | 1.5, 7.5 | |

| 80 or older | 6.6 | 2.9, 10.4 | 10.5 | 5.2, 15.8 | 7.5 | 4.2, 10.8 | 1.7 | 1.1, 2.3 | 3.0 | 0.0, 6.5 | 2.1 | 0.0, 4.4 | |

| Estrogen plus progestin | |||||||||||||

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||||

| 40 or older* | 5.2 | 3.6, 6.8 | 5.5 | 3.5, 7.5 | 2.4 | 1.5, 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.3, 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.3, 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.5, 2.5 | 0.02 |

| 40–49 | 1.3 | 0.0, 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.2, 5.8 | 0.3 | 0.0, 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.0, 0.3 | 0.0 | NA | 0.9 | 0.0, 2.2 | |

| 50–59 | 13.1 | 7.3, 18.9 | 11.8 | 4.8, 18.8 | 6.0 | 2.2, 9.7 | 2.2 | 0.0, 4.5 | 1.9 | 0.0, 4.1 | 4.2 | 0.7, 7.7 | |

| 60–69 | 5.5 | 1.8, 9.2 | 5.2 | 3.1, 7.2 | 3.1 | 1.2, 4.9 | 1.6 | 0.0, 4.1 | 3.3 | 0.2, 6.4 | 0.2 | 0.0, 0.5 | |

| 70–79 | 3.0 | 0.3, 5.7 | 3.5 | 0.7, 6.3 | 1.5 | 0.0, 3.5 | 0.7 | 0.0, 2.1 | 0.0 | NA | 0.5 | 0.0, 1.5 | |

| 80 or older | 0.0 | NA | 1.3 | 0.0, 2.8 | 0.4 | 0.0, 1.3 | 0.0 | NA | 0.9 | 0.0, 2.8 | 0.0 | NA | |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not available.

Not-available data could not be estimated because zero patients in these categories reported current hormone use.

Age-adjusted to the year 2000 US Standard Population, ages 40 years and older.

Examination of the age-specific prevalence of hormone use revealed that women in their 50s and 60s were most likely to report current use of postmenopausal hormones during 1999–2000 compared to other age groups (Table 2). Declines in hormone use after 2002 were observed among all age groups, and the absolute differences in prevalence by age group became smaller.

Similar relative declines in postmenopausal hormone use were observed among women with and without a hysterectomy, though the absolute magnitude of the decline was greater among women with a hysterectomy (Table 3). Use among women without a hysterectomy declined from 14.3% (95% CI: 10.8, 17.9) in 1999–2000 to 3.4% (95% 1.8, 4.9) in 2009–2010. This trend was due to decreases in use of both estrogen only and estrogen plus progestin formulations. Since very few women with a hysterectomy used estrogen plus progestin during any study period, the decline in postmenopausal hormone use among these women (36.7% in 1999–2000 to 7.9% in 2009–2010) was almost exclusively due to a decline in use of estrogen only preparations. During all time periods examined, overall use of hormones was substantially higher among women who had a hysterectomy compared to women with no history of hysterectomy.

Table 3.

Percent of Women Aged 40 and Older Reporting Current Use of Oral Postmenopausal Hormones, by Hysterectomy Status and Study Period, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2008

|

No Hysterectomy* |

Hysterectomy† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %‡ | 95% CI | %‡ | 95% CI | |

| Any formulation | ||||

| 1999–2000 | 14.3 | 10.8, 17.9 | 36.7 | 31.9, 41.5 |

| 2001–2002 | 15.0 | 11.4, 18.7 | 36.7 | 30.5, 42.8 |

| 2003–2004 | 5.9 | 4.1, 7.7 | 24.6 | 18.0, 31.1 |

| 2005–2006 | 3.4 | 2.0, 4.8 | 16.1 | 9.7, 22.4 |

| 2007–2008 | 2.0 | 0.4, 3.7 | 17.3 | 13.1, 21.6 |

| 2009–2010 | 3.4 | 1.8, 4.9 | 7.9 | 4.4, 11.5 |

| Ptrend = 0.01 | Ptrend = 0.01 | |||

| Estrogen only | ||||

| 1999–2000 | 6.5 | 3.2, 9.8 | 35.3 | 30.2, 40.4 |

| 2001–2002 | 6.1 | 4.0, 8.1 | 35.6 | 29.6, 41.5 |

| 2003–2004 | 1.8 | 0.8, 2.8 | 23.3 | 17.0, 29.6 |

| 2005–2006 | 1.5 | 0.7, 2.2 | 15.3 | 8.6, 22.1 |

| 2007–2008 | 0.4 | 0.0, 0.8 | 16.4 | 2.2, 4.2 |

| 2009–2010 | 1.0 | 0.4, 1.5 | 7.6 | 4.1, 11.0 |

| Ptrend = 0.01 | Ptrend = 0.01 | |||

| Estrogen plus progestin | ||||

| 1999–2000 | 7.7 | 5.3, 10.1 | 0.8 | 0.0, 1.9 |

| 2001–2002 | 8.2 | 5.6, 10.8 | 0.9 | 0.0, 1.8 |

| 2003–2004 | 3.6 | 2.0, 5.2 | 0.7 | 0.0, 1.5 |

| 2005–2006 | 1.3 | 0.2, 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.0, 1.8 |

| 2007–2008 | 1.4 | 0.3, 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.0, 1.1 |

| 2009–2010 | 1.9 | 0.7, 3.1 | 0.3 | 0.0, 0.8 |

| Ptrend = 0.04 | Ptrend = 0.05 | |||

Column displays prevalence of hormone use among women with no history of a hysterectomy.

Column displays prevalence of hormone use among women who have had a hysterectomy.

Age-adjusted to the year 2000 US Standard Population, ages 40 years and older.

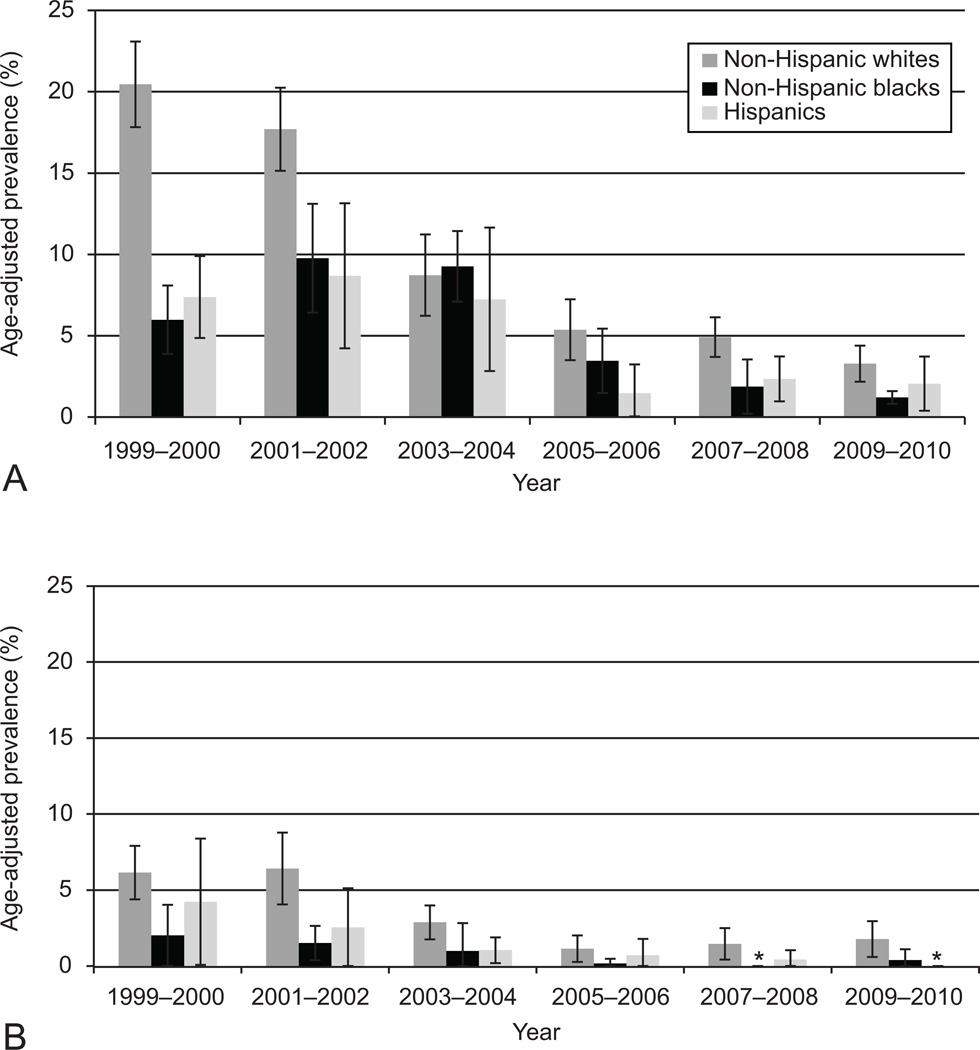

During the 1999–2000 period, current use of postmenopausal hormones (any preparation) was highest among non-Hispanic whites, women who attended college, and women with a higher income-to-poverty ratio (Figure 1). The prevalence of use decreased markedly between the 2001–2002 period and the 2003–2004 period for non-Hispanic whites, but the decline in use was delayed for non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanic women. As the overall prevalence of hormone use declined throughout the study period, the absolute differences in hormone use by race/ethnicity and poverty income ratio became much smaller, though the relative differences persisted. In 2009–2010, 5.4% (95% CI: 3.6, 7.1) of non-Hispanic whites reported current use of oral postmenopausal hormones, whereas the prevalence was 1.6% (95% CI: 0.7, 2.5) and 2.2% (95% CI: 0.5, 3.8) among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, respectively. The prevalence among women with an income-to-poverty ratio of at least five was 7.0% (95% CI: 3.9. 10.1) in 2009–2010, compared to 1.9% (95% CI: 0.4, 3.4) among women with an income-to-poverty ratio less than one. Little variation in hormone use by education was observed by 2009–2010, as the prevalence was 3–5% across all groups.

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted trends in oral postmenopausal hormone use according to (A) race or ethnicity, (B) education, and (C) income-to-poverty ratio among women aged 40 and older, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2010.

Preparation-specific trends in postmenopausal hormone use were investigated by race/ethnicity (Figure 2). Similar patterns were observed for both estrogen only and estrogen plus progestin use. Non-Hispanic whites continue to have a higher prevalence of hormone use for both formulations, though the absolute magnitude of the difference in use has declined sharply.

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted trends in (A) estrogen only and (B) estrogen plus progestin oral hormone use according to race or ethnicity among women aged 40 and older, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2010. *None of the 373 non-Hispanic black women interviewed in 2007–2008 or the 487 Hispanic women interviewed in 2009–2010 reported current use of estrogen plus progestin.

DISCUSSION

The decline in postmenopausal hormone use in the United States since 2002 has been dramatic and sustained. In 1999–2002, one in five women over age 40 was a current user of oral postmenopausal hormones. By 2009–2010, the prevalence was fewer than one in twenty. Declines in hormone use were observed among all ages, race/ethnicities, education, and income groups investigated. Use of estrogen only and estrogen plus progestin have both decreased sharply, and the prevalence of use has declined among women with and without a hysterectomy.

The 2002 WHI publication that triggered the dramatic reduction in hormone use reported that the harms of estrogen plus progestin (including excess coronary heart disease, breast cancer, stroke, and pulmonary embolism) outweighed the benefits (reduced risk of colorectal cancer and hip fracture) among women with an intact uterus (9). In 2004, results were reported for the WHI trial of estrogen only among women with hysterectomy (14). The estrogen only intervention was associated with an elevated risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism, a reduced risk of breast cancer and hip fracture, and no effect on coronary heart disease or colorectal cancer. The authors of both the 2002 and 2004 trial reports concluded that each form of postmenopausal hormone use was unsuitable for chronic disease prevention in healthy women (9, 14). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration continues to support the use of postmenopausal hormones for the treatment of menopausal symptoms, but recommends use of the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible duration (15).

Substantial and immediate decreases in the prevalence of hormone use following the 2002 WHI trial results were reported in a variety of study populations, most of which focused on women in health maintenance organizations or those receiving health services such as mammography (5, 16–20). Previous reports using NHANES also demonstrated a short term decline in the general population (8, 10). While the results of the WHI trial had an immediate and dramatic influence on clinical practice, a number of criticisms and concerns about the trial were raised in the following years, particularly in regard to the generalizability of the results (21–23). Surveys of physicians revealed variable, but in some cases substantial, skepticism about the WHI results and their applicability to their patients (24, 25). Our findings suggest that these concerns about the WHI have not led to a rebound in the use of postmenopausal hormones. On the contrary, use continued to decline throughout the study period. Relative to 2001–2002 levels, the prevalence of hormone use among women aged 40 and older was down by 47% in 2003–2004, 72% in 2005–2006, 75% in 2007–2008, and 79% in 2009–2010.

Other factors may have contributed towards the sustained decline in hormone use. Since the publication of the WHI results, there has been a steady progression of new studies describing the potential harms associated with postmenopausal hormone use (26–28). In addition, the observed decline in breast cancer incidence following the WHI results has been attributed to a population-wide decrease in hormone use (29). The scientific and media attention garnered by these studies likely provide further pressure for women and physicians to refrain from utilization of postmenopausal hormones. Another factor potentially influencing hormone use is the declining rate of bilateral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy over the past 10 years (30). Preservation of ovarian function would reduce the need for postmenopausal hormones after hysterectomy.

In 2009–2010, the highest observed prevalence of hormone use among a single subgroup was 7.9% among women with a hysterectomy. This represents about one-fifth of the peak prevalence of 36.7% among women with a hysterectomy during 1999–2002. The decline in hormone use among women without a hysterectomy has been similarly severe, as the overall prevalence declined from 14.3% in 1999–2000 to only 3.4% in 2007–2008.

Prior to 2003, a substantial proportion of women with no history of hysterectomy reported use of estrogen only formulations, which generally would be contraindicated due to risk of endometrial cancer. Similar results were reported in the 1999 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) using self-reported hormone use data (31), as well as in a study using medical charts and pharmacy claims data (32). It is possible that inaccurate self-reporting of the type of hormone preparation may have contributed to our finding and that of the 1999 NHIS study. However, there is evidence that women can report type of preparation with high accuracy. Among women reporting current use of postmenopausal hormones in the Million Women Study, excellent agreement (kappa = 0.95) was observed between questionnaire and prescription records regarding type of hormone preparation (estrogen only, estrogen plus progestin, or other) (33). Similarly, a report from the Malmo Diet and Cancer Study in Sweden found high agreement (kappa > 0.8) between questionnaire and personal diary reports of estrogen only and combined estrogen plus progestin formulations (34). Nonetheless, the formulation-specific estimates presented here should be considered with some caution. Additional research is needed to explore whether estrogen only preparations are being used inappropriately by women with an intact uterus.

Our results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating ethnic and socioeconomic variation in HRT use (35–37). We additionally observed differences in the pace of change in hormone use following the WHI results. Although the impact of the WHI was heralded as support for the ability of clinicians to rapidly adjust practice patterns in the presence of new evidence (4), our results suggest that use declined more slowly among minorities. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in the diffusion of new medical information and technology utilization (38–40). However, differences in indication for use among racial and ethnic groups could also contribute towards this trend. For example, the more rapid decline among non-Hispanic whites may reflect a higher initial percentage of use for chronic disease prevention rather than short term use for treatment of severe menopausal symptoms.

Strengths of this study include the use of nationally representative data from NHANES, which is weighted to account for non-response and non-coverage. Comparison of NHANES data from this work and previous studies (8, 10) indicates that hormone use in the general US population is substantially lower than that observed using self-reported or medical records data in health management organizations and other special populations (5, 16, 18–20). The primary limitation to consider in the interpretation of our results is the self-reported nature of the hormone use data. Notably, however, previous studies comparing self-reported hormone use with clinical or insurance records have indicated that women can recall hormone use with a high degree of accuracy (41, 42). Length of recall has been found to be associated with poorer accuracy (43). Since we were examining the prevalence of current use, we would expect high accuracy in our overall prevalence estimates for postmenopausal hormone use. Finally, we were unable to evaluate detailed trends in the use of patch, cream, suppository, or injection forms of postmenopausal hormone use. Of women reporting ever use of any form of postmenopausal hormones, the proportion reporting the use of pills was about 90% throughout the study period (range, 88% - 94%). This suggests that changes to other forms of hormone delivery during this period are unlikely to have contributed substantially to the steep decline in use of oral preparations.

The percent of American women reporting that they are currently using postmopausal hormones has now declined below 5%. The history of postmenopausal hormone use in the United States has been turbulent, and has previously endured sustained declines in popularity (44). Continued monitoring of conventional and new types of treatments for menopausal symptoms is warranted to evaluate the role of these therapies in women’s health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA152958).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kennedy DL, Baum C, Forbes MB. Noncontraceptive estrogens and progestins: use patterns over time. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65(3):441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemminki E, Kennedy DL, Baum C, McKinlay SM. Prescribing of noncontraceptive estrogens and progestins in the United States: 1974–86. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(11):1479–1481. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.11.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wysowski DK, Golden L, Burke L. Use of menopausal estrogens and medroxyprogesterone in the United States: 1982–1992. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(1):6–10. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00339-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291(1):47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buist DS, Newton KM, Miglioretti DL, Beverly K, Connelly MT, Andrade S, et al. Hormone therapy prescribing patterns in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 Pt 1):1042–1050. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143826.38439.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitlock EP, Johnson RE, Vogt TM. Recent patterns of hormone replacement therapy use in a large managed care organization. J Womens Health. 1998;7(8):1017–1026. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newton KM, LaCroix AZ, Leveille SG, Rutter C, Keenan NL, Anderson LA. Women's beliefs and decisions about hormone replacement therapy. J Womens Health. 1997;6(4):459–465. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu A, Card A, Lin SX, Mota S, Carrasquillo O, Moran A. Changes in postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy use among women with high cardiovascular risk. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2184–2187. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JK, Alley D, Hu P, Karlamangla A, Seeman T, Crimmins EM. Changes in postmenopausal hormone therapy use since 1988. Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(6):338–341. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 3.5 - April 2011. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch and Data Modeling Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Statistics in medicine. 2000;19(3):335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. News Release: FDA updates hormone therapy information for postmenopausal women. 2004 Feb 10; 2004.

- 16.Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gerstenberger EP, Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(3):184–188. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Rosenberg L, Kelley K, Cooper SG, Mitchell AA. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy since the Women's Health Initiative findings. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(12):837–842. doi: 10.1002/pds.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Uratsu CS, Selby JV, Kushi LH, Herrinton LJ. Recent declines in hormone therapy utilization and breast cancer incidence: clinical and population-based evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):e49–e50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerlikowske K, Miglioretti DL, Buist DS, Walker R, Carney PA. Declines in invasive breast cancer and use of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a screening mammography population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(17):1335–1339. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glass AG, Lacey JV, Jr, Carreon JD, Hoover RN. Breast cancer incidence: 1980–2006: combined roles of menopausal hormone therapy, screening mammography, and estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(15):1152–1161. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machens K, Schmidt-Gollwitzer K. Issues to debate on the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study. Hormone replacement therapy: an epidemiological dilemma? Hum Reprod. 2003;18(10):1992–1999. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer RD. On the need to clarify and disseminate contemporary knowledge of hormone therapy initiated near menopause. Climacteric. 2010;13(4):303–306. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.496316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manson JE, Bassuk SS. Invited commentary: hormone therapy and risk of coronary heart disease why renew the focus on the early years of menopause? Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(5):511–517. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Power ML, Schulkin J, Rossouw JE. Evolving practice patterns and attitudes toward hormone therapy of obstetrician-gynecologists. Menopause. 2007;14(1):20–28. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000229571.44505.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bush TM, Bonomi AE, Nekhlyudov L, Ludman EJ, Reed SD, Connelly MT, et al. How the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) influenced physicians' practice and attitudes. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1311–1316. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0296-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinton LA, Richesson D, Leitzmann MF, Gierach GL, Schatzkin A, Mouw T, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2008;17(11):3150–3160. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves GK, Beral V, Green J, Gathani T, Bull D. Hormonal therapy for menopause and breast-cancer risk by histological type: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(11):910–918. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70911-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morch LS, Lokkegaard E, Andreasen AH, Kruger-Kjaer S, Lidegaard O. Hormone therapy and ovarian cancer. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(3):298–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ, et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(16):1670–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novetsky AP, Boyd LR, Curtin JP. Trends in bilateral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;118(6):1280–1286. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318236fe61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brett KM, Reuben CA. Prevalence of estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy use. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(6):1240–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White VE, Bennett L, Raffin S, Emmett K, Coleman MJ. Use of unopposed estrogen in women with uteri: prevalence, clinical implications, and economic consequence. Menopause. 2000;7(2):123–128. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banks E, Beral V, Cameron R, Hogg A, Langley N, Barnes I, et al. Agreement between general practice prescription data and self-reported use of hormone replacement therapy and treatment for various illnesses. J Epidemiol Biostat. 2001;6(4):357–363. doi: 10.1080/13595220152601837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merlo J, Berglund G, Wirfalt E, Gullberg B, Hedblad B, Manjer J, et al. Self-administered questionnaire compared with a personal diary for assessment of current use of hormone therapy: an analysis of 16,060 women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(8):788–792. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.8.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brett KM, Madans JH. Use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: estimates from a nationally representative cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(6):536–545. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brennan RM, Crespo CJ, Wactawski-Wende J. Health behaviors and other characteristics of women on hormone therapy: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 1988–1994. Menopause. 2004;11(5):536–542. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000119982.77837.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman-Koss D, Crespo CJ, Bellantoni MF, Andersen RE. The relationship of race/ethnicity and social class to hormone replacement therapy: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988–1994. Menopause. 2002;9(4):264–272. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Upchurch GR, Dimick JB, Wainess RM, Eliason JL, Henke PK, Cowan JA, et al. Diffusion of new technology in health care: the case of aorto-iliac occlusive disease. Surgery. 2004;136(4):812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tunis SR, Bass EB, Klag MJ, Steinberg EP. Variation in utilization of procedures for treatment of peripheral arterial disease. A look at patient characteristics. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(8):991–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, Schrag D, Godfrey H, Hiotis K, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson D, Yu TW, Hincal F. Effect of some phthalate esters in human cells in the comet assay. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 1999;19(4):275–280. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6866(1999)19:4<275::aid-tcm4>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandini L, Pentti K, Tuppurainen M, Kroger H, Honkanen R. Agreement of self-reported estrogen use with prescription data: an analysis of women from the Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Prevention Study. Menopause. 2008;15(2):282–289. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181334b6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodman MT, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN. Agreement between interview information and physician records on history of menopausal estrogen use. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(5):815–825. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bush TL, Barrett-Connor E. Noncontraceptive estrogen use and cardiovascular disease. Epidemiol Rev. 1985;7:80–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]